Abstract

The outbreak of COVID-19 constitutes an unprecedented disruption globally, in which risk management framework is on top priority in many countries. Travel restriction and home/office quarantine are some frequently utilized non-pharmaceutical interventions, which bring the worst crisis of airline industry compared with other transport modes. Therefore, the post-recovery of global air transport is extremely important, which is full of uncertainty but rare to be studied. The explicit/implicit interacted factors generate difficulties in drawing insights into the complicated relationship and policy intervention assessment. In this paper, a Causal Bayesian Network (CBN) is utilized for the modelling of the post-recovery behaviour, in which parameters are synthesized from expert knowledge, open-source information and interviews from travellers. The tendency of public policy in reaction to COVID-19 is analyzed, whilst sensitivity analysis and forward/backward belief propagation analysis are conducted. Results show the feasibility and scalability of this model. On condition that no effective health intervention method (vaccine, medicine) will be available soon, it is predicted that nearly 120 days from May 22, 2020, would be spent for the number of commercial flights to recover back to 58.52%–60.39% on different interventions. This intervention analysis framework is of high potential in the decision making of recovery preparedness and risk management for building the new normal of global air transport.

Keywords: Air transport, Post-recovery, Policy intervention, COVID-19, Causal Bayesian network (CBN)

1. Introduction

As a particular case of risks, the pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is not only a public health emergency but also provides an inestimable threat to our globalization and economy. Mobility restriction (Kraemer et al., 2020) for the virus containment in many countries emerged immediately observable effects on the global aviation industry. In this paper, the research objective is commercial flight in relation to the ongoing pandemic, while air travel is critical to the function of nations' and world's economy as a whole (Dunn and Wilkinson, 2016). Countries fighting with epidemic are in different stages, meanwhile the tendency of one country's public policy (either inaction, mild or over-zealous) induces more uncertainties on the modelling of the post-recovery process. Other factors, such as the ability of medical treatment, as well as some delay responses, will further intensify the complexity of this problem.

Since the first reported case, a large number of studies are undertaken on innovations of pathogenesis, transmission and therapeutics of COVID-19 (Rothan and Byrareddy, 2020). Nevertheless, it is hard to foreknow when health interventions (vaccine and effective medicine) could becomes a reality. Besides the unpredictability on health interventions, non-health interventions are other critical issues that we can consider but attract less notice from the system-of-system perspective. In the past, the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS, 2003), novel influenza A (H1N1, 2009), and middle-east respiratory syndrome (MERS, 2012), have to some extent impacted a few geographical areas (endemics) compared with COVID-19, which further implies the extraordinary circumstances we are currently facing. Hence, the struggling dilemma for the authorities is not only the never before experienced situation, that no direct historical data can be drawn upon to deal with this worldwide pandemic, but also the tight interaction of policy interventions between outbreak control and macroeconomics. Without well-prepared and collaborative authorities, the post-recovery process of global air network would be immensely slow and costly, as well as speed up the economic recession and enlarge contemporary poverty.

In this paper, Causal Bayesian Network (CBN) is utilized to model the causal relationship and uncertainties in the post-recovery of air transport as well as evaluate the possible consequences under some policy interventions. To the authors' best knowledge, this is the first work that concentrates on the risk preparedness of global air transport's rapid post-recovery from the disruption of COVID-19 pandemic.

The outline of this paper is organized as follows: section 2 demonstrated the related literature review; preliminaries on CBN modelling and the developed model are described in section 3; calibration and sensitivity analysis of the described CBN model are discussed in section 4; policy interventions assessment and some suggestions are discussed in section 5; conclusions are drawn in section 6.

2. Literature review

From the first report of COVID-19, many works concerning the modelling of virus transmission and health control have been published (Kucharski et al., 2020). Those models can simulate the influence of isolating cases and contacts (Hellewell et al., 2020), as well as travel restrictions (Chinazzi et al., 2020), on the virus spread. Since lockdown and international travel restriction have been announced by some main epidemic countries, the sky is more and more clear, far beyond our expectations. The past outbreaks (e.g. SARS, H1N1) generally needed 6–8 months for the total recovery (Iacus et al., 2020). Nevertheless, since COVID-19 already exists for a relatively long time, the necessary requirements for reopening and economic growth cannot be underestimated. A system may have different recovery paths (Barabadi and Ayele, 2018), in which well-examined policy interventions such as infrastructure capacity building (Deshmukh and Hastak, 2014) and inter-organizational resource coordination (Opdyke et al., 2017) could have positive effects. Until now, few studies can be seen on the post-recovery of urban system's components with COVID-19.

Policy interventions have been extensively utilized for obtaining the desired management goals in multi-disciplinary domains, for instance, debt renegotiation (Agarwal et al., 2017), human trafficking and health (Zimmerman et al., 2011), and offshore wind energy innovation (Jacobsson and Karltorp, 2013). In the meantime, the assessment of policy interventions is important and necessary. Empirical-based (Wesseling et al., 2016) and scenario-based (Al-Lamee et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2017) are two main assessment approaches. Essentially, they involve the reasoning of causal relationships between multiple influential factors (Pawson et al., 2005). In air transport domain, the most frequently investigated causal relationship is its relation to economic development (Hakim and Merkert, 2016) and urbanization (Maparu and Mazumder, 2017). For the establishment of the causal relationship between global aviation and COVID-19 pandemic, it is a challenging work that explicit/implicit interactions from authorities, travellers, and the virus should be considered.

In recent years, ‘resilience’ (Mattsson and Jenelius, 2015) is a hot paradigm to describe urban system's ability to maintain its functionality, i.e., rapidly absorb/adapt/recovery from external disruptive events, such as extreme weather (Zhu et al., 2020). The complex network theory has been adopted for modelling (Zanin and Lillo, 2013) and enhancement (Dunn and Wilkinson, 2016) of air traffic network's resilience. Traditional analysis has been generally carried out from either the supply or demand side. However, it is worth mentioning that air aviation at current circumstances is more impacted by public policies, which can cause large-scale link failures (connection breaks), in few weeks. Hence, the inherent redundancy feature of the airline domain cannot exhibit its ability to resist the crisis. That is the reason why the total impact of global aviation from COVID-19 belongs to the issue of resilience; but here we focus on the post-recovery process only. Moreover, compared to random failures (Cardillo et al., 2013), or failures in the physical/service/cognitive layer (Janić, 2015) of air transport networks, both demand and supply of air transport is unclear and hard to estimate simultaneously. Moreover, the post-recovery process would be a long-lasting stage within the ‘resilience triangle’ (Holling, 1996) of the air transport system. Meanwhile, in disaster management, post-recovery is the most challenging task due to the uncertainties generated by the interactions among influential multivariate factors (Rathfon et al., 2013). From above, the aspirations on the rapid recovery of global aviation should start planning immediately (Becker et al., 2020).

Causality appears everywhere in life when studying data, and related studies can be categorized as event causality (Zhao et al., 2016) and process causality (Anderson and Scott, 2012). In general, counterfactual theory (Reutlinger, 2016), non parametric structural equations (Li et al., 2017), and directed acyclic graphs (Ji et al., 2018) are methods in the scope of event causality; on the other hand, causal loop diagram (Kiani et al., 2009) is a methodological type of process causality. Furthermore, difference-in-difference (DID) (Li et al., 2012) is a quantitative measurement method for analyzing policy effects, which is more suitable for panel data rather than cross-sectional data sets; propensity score matching (PSM) (Dehejia and Wahba, 2002) is a class of statistical methods for the analysis of intervention effects using non-experimental or observational data. DID and PSM have been frequently utilized in the economic domain, and have applications that extend to other disciplines, such as traffic (Li et al., 2012) and psychological studies (Harder et al., 2010).

In the assessment of global air transport's post-recovery, it is obvious that interactions between components with unknown variables and distinct pieces of evidence need to be considered (Hosseini and Barker, 2016b). CBN, which is widely used in risk assessment and decision analysis (Fenton and Neil, 2018), has the capabilities in dealing with those difficulties. It is a type of Bayesian Network (BN) that is defined as a causality network, in which the strength of the causal links are represented as conditional probabilities (Jensen, 2001). This causality inference method can combine different data sources, such as expert knowledge, questionnaires, and interviews. That characteristic makes it extremely suitable for our problem. Application of CBN can be found in various fields dealing with uncertainties, such as disease progression mechanisms (Koch et al., 2017), adverse drug reaction reports (Rodrigues et al., 2018), supplier selection (Hosseini and Barker, 2016a), and deep water ports (Hossain et al., 2019). Note that, more recently, CBN has been applied for avoiding the bias in testing COVID-19 infection and death rates (Fenton et al., 2020).

This section has outlined existing works in the literature that deal with the concepts of COVID-19 and other past epidemic outbreaks, systems' resilience, policy interventions, and systems' recovery rapidity. Also, we explore causality of stochastic variables that refer to physical entities and CBN methodology that can deal with complex problems with conditional probabilities. The contribution of the current work is that it combines all the aforementioned concepts and develops a novel methodology for assessing the effects of policy interventions to the post-COVID-19 recovery of global aviation industry. For this purpose we utilize publicly available datasets as well as questionnaires and experts’ interviews.

3. Method and model

3.1. CBN

CBN is the causal interpretation of BN, which belongs to the probabilistic graphical model. The intuitive structure consists of a direct acyclic graph (DAG), in which is the set of variables, and the set of directed edges, which represent the causal relations from variable to its parent node Par, i.e. the dependency between variables. is the parameter set, in which denotes the conditional probability distribution (cpd) of a node given its parent nodes Par.

Essentially, it is assumed that CBN satisfies the causal Markov condition, which means a node is conditionally independent of its non-descendent nodes. CBN models can build and test causal hypotheses (Pearl, 2009) as well as predict the effects of possible interventions with uncertainties, even if only non-experimental data is available (Koch et al., 2017).

The joint probability distribution of a CBN can be expressed as,

| (1) |

The inference of CBN is to compute the posterior marginals on a observations . However, the complexity of inference via the full joint distribution has exponential growth with the number of variables, namely, the complexity of an N-node network, if nodes have up to k parents, is . Therefore, ways that can reduce modelling complexity should be considered. In this work, dynamic discretization and Leaky noisy-OR gate are adopted.

Dynamic discretization is a good way to deal with hybrid BNs, in which relative entropy error is employed to iteratively adjust the discretization in response to new evidence. Let X be a continuous node in CBNs, which state-space is denoted by , and probability density function (pdf) of X is denoted as . By discretization, would translate a continuous variables X into discrete variables (mappings), with labels that partition X's domain into hypercubes, such as the mapping of into states , and . Thus, is replaced by a probability distribution on the set of . The purpose of dynamic discretization is finding an optimal set and optimal values for locally constant functions on the partitioning intervals. When iteration to convergence, is approximate with .

Relative entropy or Kullback-Leibler (KL) distance between two different probability density functions and is used as a metric for error introduced by the discretization as follows,

| (2) |

With , a discretization of f with hypercubes , note that,

| (3) |

Then, each term can be bounded by,

| (4) |

where denotes the length of a discretization subregion ; parameters , , and are function's mean, maximum, and minimum, respectively, given discretization interval.

In this paper, the post-recovery of global air transport is conditioned on public policy and flight willingness, which is solving by a Leaky Noisy-OR gate and will be described in detail later, in section 4. Note that, Leaky Noisy-OR gate is an efficient way to solve the compact elicitation of the conditional probabilities in a CBN.

The leaky factor λ represents that Y will be True when all of its causal factors are False, as described by,

| (5) |

Then, the formal definition of the Leaky noisy-OR function can be written as,

| (6) |

It should be noted, that in Leaky Noisy-OR gate, only parameters are required for the full conditional probability table (CPT) specification, i.e., n weighted parameters and one leaky factor λ, which would improve the simulation speed significantly.

3.2. Model description

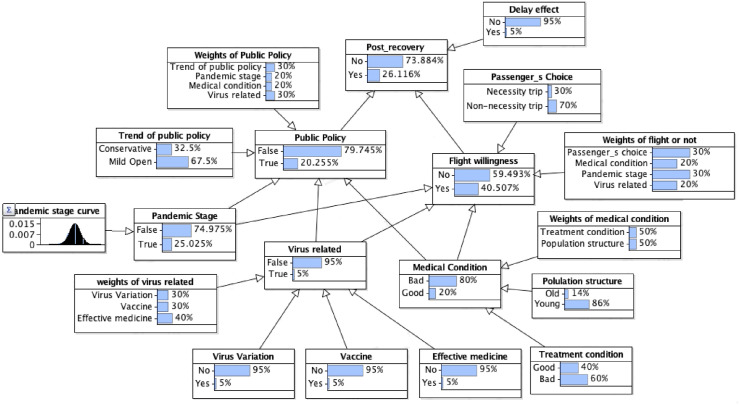

In this model, the public policy, formulated by the government and travellers' flight willingness are chosen as the two main influential factors in the post-recovery of global aviation. The causal relationship between main factors and subfactors, namely the trend of public policy, pandemic stage, virus related, medical condition and passenger's choice, is illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Multi-factors of global air transport's post-recovery process influenced by COVID-19 pandemic.

The five subfactors are discussed in details as follows.

-

1.

Tendency of public policy: We evaluate the tendency of public policy of countries with total cases ranked in top 40 (more than 20,000 cases as of May 22, 2020). Note that the study on the tendency of one country's policy, either conservative, mild or open, is not meant to judge whether its policy is correct or not, due to the different social-economic backgrounds and considerations, but rather to get the distribution of the modelling parameters. Tendency index , is simulated with 1) response days for the announcement of state of emergency since first reported case; 2) response days for the lockdown (national/regional) since first reported case; 3) recommendation of social distance; and 4) recommendation of wearing a mask (optional/mandatory). A score would be given to each index of according to the open-source data. The details of each country's index and related weights can be referred to the Appendix. The score of from a lower to higher value represents the slow response/no recommendation to quick response/strong recommendation, respectively. With this evaluation framework, tendency of public with conservative, mild and open are counted for 32.5% (>2.7), 55% () and 12.5% (<0.9), respectively. Moreover, visualization of the 40 investigated countries can be seen in Fig. 2 , in which the circle size represents the relative ratio as of May 22, 2022. This ratio is simulated with each country's total reported cases compared with the country that has the maximum number. From Fig. 2, it can be observed that generally the countries with later first reported case, the rapid response can be found, for which the previous experience from other countries can be used as reference.

-

2.

Pandemic stage: In fact, it is hard to recognize which stage of the pandemic are we in from the global view, especially with the uncertainties of health innovations. Estimated from the real-world data, a representation form of Gaussian cumulative distribution function (cdf) is being used for the approximation of pandemic stage (see Fig. 3 ). is the probability that X will take a value less than or equal to x, as shown below,

| (7) |

Fig. 2.

Evaluation on the tendency of public policy (as of May 22, 2020).

Fig. 3.

Prediction of pandemic stage.

Three scenarios are being designed, as shown in Table 1 , with upper value assumptions of total cases , , and , respectively. The predicted time horizon is set until the end of year 2020. We use the real-world data before May 22 (marked with the gray vertical line) for estimation, whilst the rest days for the prediction. Scenario s2 is the one that matches well with the total reported cases globally, which reveals that if current situation (either non-effective treatment or difficulties in nation-wide isolation for a relatively long period) continues, the pandemic could not end within this year.

-

3.

Virus related: In this subfactor, virus variation, vaccine and effective medicine are considered. Here, ‘virus variation’ refers to the probability of virus that mutating to a new type that is unknown to doctors, which requires a new round of fundamental investigations, such as genome sequencing, determination of the treatment plan, and the requirement of new vaccine. However, there is another possibility that COVID-19 would mutate to a state that cannot threaten people's lives, or exhibit low death rates, which is an optimistic scenario but unpredictable. Here, we mainly focus on modelling the current situation of the pandemic and assume low probability for variation; note that a variation of COVID-19 might happen and lead to a global extremely serious situation or even a quick recovery; both these scenarios are beyond the scope of this investigation framework. Nevertheless, even under the current pandemic state, we might still need a long period to recover or not be able to achieve the large-scale application of vaccine and other effective medicine, according to experts' knowledge.

-

4.

Medical condition: Treatment condition and population structure are chosen for the evaluation of the factor medical condition, which reflects the inherent feature of our society's reaction to COVID-19 pandemic. It is generally accepted that older population is at higher risk with this virus. The ageing population accounts between 3% (Saudi Arabia) and 27% (Japan) for all countries globally in year 2019; consequently, an ageing population of 14% is chosen as a systemic viewpoint. As to the treatment condition, it can be said that there is no country around the world fully prepared for the current crisis, but this is something that will change gradually as the pandemic goes on. In the current study, Delphi protocol (Grisham, 2009) is followed, where several rounds of questionnaires are acquired by ten experts and this process is repeated and does not stop until all experts reach a consistent decision that treatment condition is good with a probability of 40% to treat the pandemic globally. Different people with varying backgrounds and living environments will have different preception on this index, so the data acquisition with Delphi protocol tries to have an equilibrium result of this index.

-

5.

Passenger's choice: For simplicity, and without loss of generality, we have divided the travelling purpose as necessity trips (e.g. business trips, study) and non-necessity trips (e.g. pleasure, holiday). Among this two types, the travel demand for necessity trips is modelled as less influenced by the policy and pandemic situation, i.e., once flight lines reopen, they would rather prefer to travel by flight as compared to the travellers on the non-necessity trips that would be probably cancelled.

Table 1.

Parameters in pandemic stage prediction.

| Scenario | Upper Value Assumption (a) | B | μ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| s1 | 55,000,000 | 260 | 0 | 90 |

| s2 | 60,000,000 | 260 | 0 | 80 |

| s3 | 70,000,000 | 260 | 0 | 70 |

4. Model calibration and sensitivity analysis

The described causal relationship is modelled via the Bayesian modelling tool AgenaRisk® (Fenton et al., 2019; Pérez-Miñana, 2016), as shown in Fig. 4 . We firstly perform the model calibration with current status (May 22, 2020), which is almost the worst case (25%–26% commerical flight compared with normal amounts before), as depicted in Fig. 5 . The announcement of lockdown strategy in European and North America countries generally between March 10, 2020 and March 20, 2020 (see Table 8). In the next 20 days, the system performance has experienced a sharply decrease, as shown in Fig. 5. Here system performance index is defined as . N is the 7-day moving average of the total number of commercial flights, which is the most directly perceived indicator and the data is easier to be obtained.

Fig. 4.

CBN model (scenario: s2).

Fig. 5.

Observed total reported cases and system performance (as of May 22, 2022)

(Data source https://www.flightradar24.com/data/statistics and https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/).

The techniques for reducing modelling complexity are explained below.

-

1.

Dynamic discretization: it is used for the judgement from Predicted Pandemic Stage (PPS) to “on/fail” binary possibility. A PPS is defined as a Truncated Normal Distribution (TNORM), i.e. TNORM(μ,,LB,UB), in which four parameters in parentheses represents the predicted mean value, variance, lower bound and upper bound, respectively. Then, the on/fail possibility could be expressed as if(PPS day, On, Fail). This PPS is what we have estimated in section 3.2.

-

2.

Leaky noisy-OR gate: The simulation of “post recovery” is defined as,

| (8) |

This definition means that “post recovery’’ is True with a probability of if and only if “public policy’’ is True. Meanwhile, it is the same with node “post recovery’’ and “delay factor’’. Here, λ is the leaky probability, which reflects how other influential factors, besides public policy and flight willingness, impact on the recovery (whether significant or not).

-

3.

Multi-factors: Effects caused by multi-factors are simulated with influential variables and weights . Weights-of-evidence in this model is acquired by interviews from decision-makers, travellers and epidemiologists. The effect of multi-factors can be calculated by function as follows,

| (9) |

Then, three scenarios with the different estimated pandemic stages are calibrated with different delay factors (see Table 2 ). Other parameters are set the same in all three scenarios. “Delay factor’’ mentioned here implies that the earlier the stage we are in, the time spent for responses from both governments, airline companies as well as travellers would be longer. Parameters in Eq. (8), , , and λ are set to 0.2, 0.2, 0.3 and 0.15, respectively. The value of λ reflects whether other unconsidered factors are significant to the results or not. This uncertainty of λ is discussed in section 5.

Table 2.

Calibration of the delay factor with three scenarios (worst case 26%).

| Scenarios | Estimated stage | Delay factor | I |

|---|---|---|---|

| s1 | 37.32% | 1.00% | 26.19% |

| s2 | 25.03% | 5.00% | 26.12% |

| s3 | 16.33% | 10.00% | 26.57% |

Besides, sensitivity analysis is performed via the Tornado graphs, which illustrate how input variables can affect the output variables in a deterministic way, as shown in Fig. 6 . Short abbreviations are labelled below the figure for a clearer visualization. The length of a bar in Tornado graph represents its influence on the probability of the “post recovery” node. No matter in the case that “post-recovery = Yes” or “post-recovery = No”, “flight willingness” and “public policy” are the two most sensitive nodes, while “virus variation” is the least sensitive node. That result follows the actual situation, that is, the non-significant feature of “effective medicine”, “vaccine”, and “virus variation” implies the expert knowledge on the innovation difficulties and virus itself.

Fig. 6.

Sensitivity analysis

(*abbreviations: Public Policy (PP), Flight Willingness (FW), Pandemic stage (PS), Medical Condition

(MC), Virus Related

(VR), Trend of Public Policy

(TPP), Passenger's Choice(PC), Treatment Condition(TC), Effective Medicine(EM), Vaccine(V), Virus Variation(VV)).

5. Interventions analysis

With the calibrated and validated CBN model, the forward belief propagation analysis is utilized to answer the “if-then” question. In Table 3 , forward belief propagation analysis is presented. When the pandemic stage would be approximately finished, in the case that we would gradually move towards a good medical condition, the system performance index I would recover back to approximately 31%–33% according to this CBN model. Moreover, in the fortunate case that we could get the vaccine and effective medicine soon (assume e.g. 200 days since the start of outbreak), the post-recovery of global aviation would increase to approximately 35%–37%. Further on, if we could achieve the nodes “VR = True” & “MC = True” at the same time, then the system would probably recover back to 40%–41%. Note that these are the cases without public policy interventions, and compared to the pre-pandemic nominal situation.

Table 3.

Forward belief propagation when pandemic stage approximately finished.

| Scenarios | PS = ‘True’ | PS = ‘True’,MC = ‘True’ | PS = ‘True’,VR = ‘True’ | PS = ‘True’,VR = ‘True’,MC = ‘True’ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s1 | 26.19% | 31.13% | 35.96% | 35.36% | 40.03% |

| s2 | 26.12% | 31.92% | 36.73% | 36.13% | 40.75% |

| s3 | 26.57% | 33.00% | 37.69% | 37.11% | 41.65% |

(*abbreviations: Pandemic Stage (PS), Medical Condition (MC), Virus Related (VR)).

Furthermore, backward belief propagation analysis is performed to explain the needed efforts in the case that we would like to return back to the ‘normal state’, i.e. the status before COVID-19 pandemic. Before discussing this, let us note that as it is widely accepted, cross-disciplinary and cross-countries collaboration is essential for a rapid post-recovery. From the result in Table 4 , besides passenger's choice, all other factors need to be increased. Consider for instance “public policy”: when the reopening and release of restrictions on international travel could increase from 20.26% to 30.74%, cooperatively, this would be quite beneficial for the quick recovery. For “passenger's choice” and “flight willingness”, the increases are expected from 30.00% to 33.88% and 40.51%–56.35%, respectively. From the result above, it suggests interventions in the post-recovery on: (1) improving the market share of non-necessity flights, such as expediting the restart of the tourist industry; (2) reducing the difficulties of international trips, such as providing rapid testing capability, therefore decreasing the waiting time. However, restart without adequate control of the pandemic within one country would be of high risks, thus this intervention should be made cautiously.

Table 4.

Backward belief propagation when pandemic stage approximately finished.

| Scenarios | Public policy | Flight willingness | Trend of public policy | Virus related | Medical condition | Passenger's choice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s2 | 20.26% | 40.51% | 32.50% | 5.00% | 20.00% | 30.00% |

| Recovery sate | 30.74% | 56.35% | 36.38% | 5.84% | 23.80% | 33.88% |

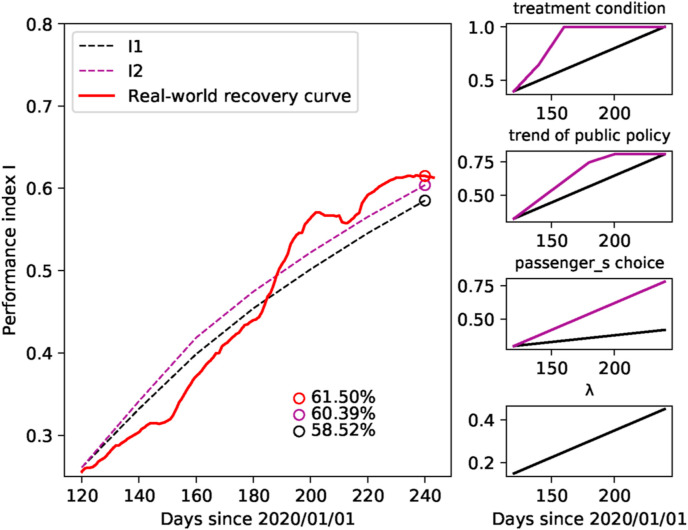

Besides the evaluation with forward/backward analysis, what the system recovery curve would evolve is another critical issue that requires attention is the evolution of system's recovery curve. Let us assume now that we are in scenario s2, as previously described (this is something not currently known), let us consider how combined leaf factors variants (namely no child nodes) could potentially help the total recovery. Here, population structure and virus-related leaf factors are assumed constant, for the reason that they cannot be influenced by public policy in a short-time horizon.

Policy intervention strategies are combined with the developed pandemic stage as presented in Table 5 . According to the previously presented analysis, we have chosen “treatment condition”, “trend of public policy”, and “non-necessity trips” as the intervention terms. The intervention scenarios I1 and I2 are refer to “general response” and “relatively active response”, respectively. Time interval T is chosen as 20 days, and simulation is updated every time interval. We set λ to be increasing with the development of pandemic, which is due to unexpected factors that we cannot currently predict: i.e. either a negative impact of large unorganized gatherings, or a positive impact of win-win cooperation achievements between countries.

Table 5.

Policy intervention scenarios: increasing rate (r) per T.

| Intervention scenarios | r(treatment condition) | r(trend of public policy) | r(non-necessity trip) | λ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | 10% | 8% | 2% | 5% |

| I2 | 25% | 14% | 8% | 5% |

Variation of the predicted system performance index I with different intervention strategies as presented in Fig. 7 . As we have considered a linear increasing rate, simulated recovery curve is smoothing than the real-world recovery curve. Within this framework, it is predicted that after 120 days since May 22, the performance index would have recovered back to 58.52%–60.39%, which is very close to the real-world 61.50%. However, the time horizon of prediction should be set cautiously. If the pandemic stage develops worse or start a new wave, then this prediction should be stopped and a new round analysis should be validated and calibrated.

Fig. 7.

Predicted recovery with different positively increasing policy interventions.

This CBN analysis model is suitable for the estimation and prediction of future trends from a macroscopic perspective. When the external factors vary heavily, the model structure and parameters should be considered again. This is an inherent shortcoming of event-based case study presented in this paper; however, at the same time, this method would be easier to be applied to an entirely new experimental setup.

Regarding interventions, they should be made on the prerequisite that the pandemic is controllable; for instance, new cases can be traced and correlated, well-prepared medical resources are available, as well as reports show lower values of daily new cases/deaths. The control strategies should not be released too early, as this could generate a more serious second-wave pandemic. The most important thing is to control the pandemic; however, that is opposed to the stimulate plan, such as restart and reopen, as well as release entry restrictions and/or quarantine measures. Nevertheless, they could help to the smooth and orderly recovery.

Although many countries have already start on the assistance programs of airline companies, the recovery process is inseparable from the pandemic. It is a pity that there are no indications of pandemic's abrupt end for now. So the depressed situation of global air transport would last for a relatively long time. Besides, it should be noted that more and more business meeting are currently held online, and employees are getting used to home office, which means that the demand of global travelling would be reduced to some degree even after the pandemic end. Therefore, the post recovery of global air transport would be a long-term horizon process.

As to the long-term policy interventions, some efforts should be done from both the governments and airline companies. Firstly, from government side, (1) provide further assistance programs for long-term low-speed recovery, such as airline companies' equity repurchases and long-term low-interest loans; (2) adjust travel restriction countries dynamically according to the pandemic control situations. Secondly, from airline companies’ side, (1) reduce or increase the Available Seat Kilometers (ASK) on the basis of dynamic demand; (2) strengthen pilot training to avoid aviation accidents caused by operational errors due to the low-frequency flights; (3) increase the capabilities on the construction of global vaccine delivery supply chain; (4) offer diverse specialized and customized services, such as sale the tickets of fly anywhere in the specified time period and area, which could help travellers change their habit to some degree during the COVID-19 pandemic.

6. Conclusion and discussion

In this work, we have utilized a probabilistic model to assess post-COVID-19 recovery of aviation industry (mostly focusing on short-term policy implications). We have outlined specific policy interventions (both by governments and by airline companies) and discuss in details their implications to the speed and level of recovery (compared to pre-COVID-19 nominal conditions). The presented results are the outcome of simulations with CBN model, after calibrating and validating it with real data. The obtained predictions can be easily verified in the near future, when further data from the ongoing pandemic will be gathered, and ultimately, when COVID-19 epidemic will be finished and global aviation will move to a new equilibrium state. Note that all states of airlines industry until then will be transient, thus, no concrete assessment can be concluded.

With the undergone extraordinary disruptions of the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic, global air transport (we refer in particular to commercial flight in this paper) has suffered the most among all transport modes. In this paper, a CBN model is proposed for the potential non-pharmaceutical policy interventions assessment during the post-recovery process of global commercial aviation industry. Uncertainties induced from the interactions between authorities, travellers and epidemiological institutions are considered. The parameters of this model are synthesized from open-source data, as well as interviews with experts and travellers.

The described model was calibrated with the worst case, i.e. 25%–26% (7-day moving average number of total commercial flights compared with the normal state). Sensitivity analysis was performed for the model validation. Forward/backward belief propagation analyses have been tested for the potential effect of policy interventions. The primary results can be concluded as follows: without non-health policy interventions, the system could recover back to 40.03%–41.65% when pandemic stage approximately finished; in the combined policy intervention strategies analysis, it is predicted that nearly 120 days are needed to recover back to 58.52%–60.39% of its original functionality.

This work implements a framework for the policy interventions assessment on the COVID-19 pandemic, in which the evaluation structure and parameters can be re-structured and re-evaluated at any time for obtaining a new status awareness. However, this study has also some limitations, i.e., the described CBN model has considered limited influential factors. Nevertheless, there might be some factor that has not been considered and might play an important role at some future period. In this work, we have utilized the uncertainty factor λ to model this issue. Moreover, due to the scalability feature of the model, it is not difficult to realize a quick re-evaluation on the parameters and adding factors.

In the future, we will continue following on the issue of the post-recovery of global air transport, especially on the preference of travellers’ choices that impact the policy-making not only on the recovery of the correlated industry but also on the optimization of network reconfiguration.

Credit authorship contribution statement

Chunli Zhu: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Jianping Wu: Conceptualization, Writing - Review Editing. Mingyu Liu: Data collection. Linyang Wang: Data collection. Duowei Li: Software. Anastasios Kouvelas: Conceptualization, Writing - Review Editing.

Declarations of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number:U1709212,U1509205); and China Scholarship Council (grant number: 201906210384).

Appendix A. Evaluation on trend of public policy

As mentioned in section 3.2, the weights of factors and discount factor are demonstrated in Table 6. We have tested four weights combinations with the simulation of , as shown in Table 7. Each index in the proposed tendency evaluation framework is illustrated in Table 8, which could also be used by other researchers. There is a small gap among the weights combinations, due to the interviews that demonstrated that all four factors are significant to some extent. The assessment value with different combinations of weights implies the existence of similar trends among the countries rank in top 40 as of 22 May 2020, as demonstrated in Fig. 8.

Table 6.

Weights of factors in evaluation.

| Emergency state | Score | Weights: |

|---|---|---|

| &Lockdown | national/regional | |

| 0–10 | 6 | 1.0/0.6 |

| 10–20 | 5 | 0.9/0.5 |

| 20–30 | 4 | 0.8/0.4 |

| 30–40 | 3 | 0.7/0.3 |

| 40–50 | 2 | 0.6/0.2 |

| 50–60 | 1 | 0.5/0.1 |

| Wearing mask | Score | Weights: |

| recommend/mandatory | ||

| 0–20 | 6 | 0.7/1.0 |

| 20–40 | 5 | 0.6/0.9 |

| 40–60 | 4 | 0.5/0.8 |

| 60–80 | 3 | 0.4/0.7 |

| 80–100 | 2 | 0.3/0.6 |

| 100–120 | 1 | 0.2/0.5 |

Table 7.

Weights combinations of each factors considered in

| No | Emergency state | Lock down | Social distance | Wearing mask |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| 2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| 3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| 4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

Table 8.

Each index of proposed tendency evaluation framework (countries that rank top 40 as of May 22, 2020).

| No | Country | First reported casea | Emergency statea | lock downa | Social distance | Wearing mask |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | USA | 21/01 | 13/03 | 19/03 | ✓ | recommend(03/04) |

| 2 | Russia | 02/03 | 31/03 | 30/03-Moscow | ✓ | mandatory in Moscow(12/05) |

| 3 | Brazil | 25/02 | 20/03 | – | ✓ | mandatory in some states(17/04–30/04) |

| 4 | Spain | 24/02 | 13/03 | 14/03 | ✓ | mandatory for people order than 6 (20/05) |

| 5 | UK | 28/02 | – | 23/03 | ✓ | mandatory, public transport, England(15/06) |

| 6 | Italy | 30/01 | 31/01 | 10/03 | ✓ | mandatory, public tranport&stores(04/05) |

| 7 | France | 24/01 | 22/03 | 17/03 | ✓ | mandatory(10/05) |

| 8 | Germany | 27/01 | – | 16/03 | ✓ | mandatory, public transport&stores(22/04) |

| 9 | Turkey | 11/03 | 03/04 | 10/04) | ✓ | mandatory, shopping or public areas(07/04) |

| 10 | Iran | 19/02 | – | – | ✓ | accepted by public |

| 11 | India | 30/01 | – | 25/03 | ✓ | compulsory in the state of Odisha(09/04) |

| 12 | Peru | 08/03 | 15/03 | 16/03 | ✓ | mandatory in streets(07/04) |

| 13 | China | December 27, 2019 | 25/01 | 23/01-Wuhan | ✓ | widely accepted by public&recommended(07/02) |

| 14 | Canada | 25/01 | 16/03 | 16/03 | ✓ | recommended(06/04) |

| 15 | Saudi Arabia | 02/03 | – | 26/02 | ✓ | mandatory(29/05) |

| 16 | Chile | 03/03 | – | 13/05-Santiago | ✓ | mandatory in public transit(06/04) |

| 17 | Mexico | 28/02 | 04/04 | – | ✓ | mandatory in Mexico City Metro(17/04) |

| 18 | Belgium | 04/02 | 18/03 | 18/03 | ✓ | mandatory in public transport older than 12(04/05) |

| 19 | Pakistan | 26/02 | 16/03 | 21/03 | ✓ | mandatory(30/05) |

| 20 | Netherlands | 27/02 | – | 15/03 | ✓ | mandatory in public transport(11/05) |

| 21 | Qatar | 29/02 | – | 15/03 | ✓ | some employees,clients, workers&shoppers(26/04) |

| 22 | Ecuador | 14/02 | 16/03 | 16/03 | ✓ | mandatory in public places(06/04) |

| 23 | Belarus | 28/02 | – | – | ✓ | – |

| 24 | Sweden | 31/01 | – | – | ✓ | – |

| 25 | Switzerland | 25/02 | 16/03 | 13/03 | ✓ | optional(22/04) |

| 26 | Singapore | 04/01 | – | 23/03 | ✓ | widely accepted by public&recommend |

| 27 | Bangladesh | 07/03 | – | 26/03 | ✓ | mandatory when stepping out(30/05) |

| 28 | Portugal | 02/03 | 18/03 | 18/03-close borders | ✓ | mandatory(03/05) |

| 29 | UAE | 29/01 | – | 08/03 | ✓ | mandatory(27/03) |

| 30 | Ireland | 29/02 | – | 12/03 | ✓ | recommend(18/05) |

| 31 | Indonesia | 02/03 | 20/03-Jakarta | 24/04 | ✓ | mandatory(08/04) |

| 32 | Poland | 04/03 | 14/03 | 15/03 | ✓ | mandatory (16/04) |

| 33 | Ukraine | 03/03 | 25/03 | 17/03-close borders | ✓ | mandatory in public places(06/04) |

| 34 | South Africa | 05/03 | 15/03 | 26/03 | ✓ | mandatory in public(01/05) |

| 35 | Kuwait | 24/02 | – | 13/03 | ✓ | mandatory(18/05) |

| 36 | Colombia | 06/03 | 17/03 | 25/03 | ✓ | mandatory, public transport & areas(23/04) |

| 37 | Romania | 26/02 | 16/03 | 30/03-Suceava | ✓ | mandatory in closed space (30/05) |

| 38 | Israel | 21/02 | 19/03 | 15/03 | ✓ | mandatory (12/04) |

| 39 | Austria | 25/02 | 15/03 | 16/03 | ✓ | mandatory(14/04) |

| 40 | Japan | 16/01 | 07/04 | – | ✓ | widely accepted by public&recommend |

Date format (day/month). Without specifically denoted, all dates belong to 2020.

Fig. 8.

Evaluation of public policy's tendency with different weights combinations.

References

- Agarwal S., Amromin G., Ben-David I., Chomsisengphet S., Piskorski T., Seru A. Policy intervention in debt renegotiation: evidence from the home affordable modification program. J. Polit. Econ. 2017;125(3):654–712. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Lamee R., Thompson D., Dehbi H.M., Sen S., Tang K., Davies J., Keeble T., Mielewczik M., Kaprielian R., Malik I.S., et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in stable angina (ORBITA): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10115):31–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32714-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G.L., Scott J. Toward an intersectional understanding of process causality and social context. Qual. Inq. 2012;18(8):674–685. [Google Scholar]

- Barabadi A., Ayele Y.Z. Post-disaster infrastructure recovery: prediction of recovery rate using historical data. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018;169:209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Becker B., Hege U., Mella-Barral P. VoxEU. org; 2020. Corporate Debt Burdens Threaten Economic Recovery after COVID-19: Planning for Debt Restructuring Should Start Now. March 21. [Google Scholar]

- Cardillo A., Zanin M., Gómez-Gardenes J., Romance M., del Amo A.J.G., Boccaletti S. Modeling the multi-layer nature of the European air transport network: resilience and passengers re-scheduling under random failures. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2013;215(1):23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Yuan M., Lu J., Zhang Q., Sun M., Chang F. Assessment of universal newborn hearing screening and intervention in Shanghai, China. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care. 2017;33(2):206–214. doi: 10.1017/S0266462317000344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinazzi M., Davis J.T., Ajelli M., Gioannini C., Litvinova M., Merler S., y Piontti A.P., Mu K., Rossi L., Sun K., et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science. 2020;368(6489):395–400. doi: 10.1126/science.aba9757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehejia R.H., Wahba S. Propensity score-matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2002;84(1):151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Deshmukh A., Hastak M. Enhancing post disaster recovery by optimal infrastructure capacity building. Int. J. Renew. Energy Technol. 2014;3(28):5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn S., Wilkinson S.M. Increasing the resilience of air traffic networks using a network graph theory approach. Transport. Res. E Logist. Transport. Rev. 2016;90:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton N., Noguchi T., Neil M. An extension to the noisy-OR function to resolve the ‘explaining away’ deficiency for practical Bayesian network problems. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2019 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton N., Neil M. Crc Press; 2018. Risk Assessment and Decision Analysis with Bayesian Networks. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton N.E., Neil M., Osman M., McLachlan S. COVID-19 infection and death rates: the need to incorporate causal explanations for the data and avoid bias in testing. J. Risk Res. 2020;23(7–8):862–865. [Google Scholar]

- Grisham T. The delphi technique: a method for testing complex and multifaceted topics. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2009;2(1):112–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim M.M., Merkert R. The causal relationship between air transport and economic growth: empirical evidence from South Asia. J. Transport Geogr. 2016;56:120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Harder V.S., Stuart E.A., Anthony J.C. Propensity score techniques and the assessment of measured covariate balance to test causal associations in psychological research. Psychol. Methods. 2010;15(3):234. doi: 10.1037/a0019623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellewell J., Abbott S., Gimma A., Bosse N.I., Jarvis C.I., Russell T.W., Munday J.D., Kucharski A.J., Edmunds W.J., Sun F., et al. Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. The Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(4):e488–e496. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30074-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holling C.S. Engineering resilience versus ecological resilience. Engineering within ecological constraints. 1996:32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain N.U.I., Nur F., Hosseini S., Jaradat R., Marufuzzaman M., Puryear S.M. A Bayesian network based approach for modeling and assessing resilience: a case study of a full service deep water port. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019;189:378–396. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini S., Barker K. A Bayesian network model for resilience-based supplier selection. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016;180:68–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini S., Barker K. Modeling infrastructure resilience using bayesian networks: a case study of inland waterway ports. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2016;93:252–266. [Google Scholar]

- Iacus S.M., Natale F., Santamaria C., Spyratos S., Vespe M. Estimating and projecting air passenger traffic during the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak and its socio-economic impact. Saf. Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsson S., Karltorp K. Mechanisms blocking the dynamics of the european offshore wind energy innovation system–challenges for policy intervention. Energy Pol. 2013;63:1182–1195. [Google Scholar]

- Janić M. Modelling the resilience, friability and costs of an air transport network affected by a large-scale disruptive event. Transport. Res. Pol. Pract. 2015;81:77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen F.V. Bayesian Networks and Decision Graphs. Springer; 2001. Causal and bayesian networks; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ji Q., Bouri E., Gupta R., Roubaud D. Network causality structures among bitcoin and other financial assets: a directed acyclic graph approach. Q. Rev. Econ. Finance. 2018;70:203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Kiani B., Gholamian M.R., Hamzehei A., Hosseini S.H. Using causal loop diagram to achieve a better understanding of e-business models. Int. J. Electron. Bus. Manag. 2009;7(3):159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Koch D., Eisinger R.S., Gebharter A. A causal Bayesian network model of disease progression mechanisms in chronic myeloid leukemia. J. Theor. Biol. 2017;433:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer M.U., Yang C.H., Gutierrez B., Wu C.H., Klein B., Pigott D.M., Du Plessis L., Faria N.R., Li R., Hanage W.P., et al. The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science. 2020;368(6490):493–497. doi: 10.1126/science.abb4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucharski A.J., Russell T.W., Diamond C., et al. Early dynamics of transmission and control of COVID-19: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):553–558. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30144-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Graham D.J., Majumdar A. The effects of congestion charging on road traffic casualties: a causal analysis using difference-in-difference estimation. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2012;49:366–377. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Ernest J., Bühlmann P. Nonparametric causal inference from observational time series through marginal integration. Econometrics and Statistics. 2017;2:81–105. [Google Scholar]

- Maparu T.S., Mazumder T.N. Transport infrastructure, economic development and urbanization in India (1990–2011): is there any causal relationship? Transport. Res. Pol. Pract. 2017;100:319–336. [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson L.G., Jenelius E. Vulnerability and resilience of transport systems–A discussion of recent research. Transport. Res. Pol. Pract. 2015;81:16–34. [Google Scholar]

- Opdyke A., Lepropre F., Javernick-Will A., Koschmann M. Inter-organizational resource coordination in post-disaster infrastructure recovery. Construct. Manag. Econ. 2017;35(8–9):514–530. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson R., Greenhalgh T., Harvey G., Walshe K. Realist review-a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J. Health Serv. Res. Pol. 2005;10(1_suppl):21–34. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl J. Cambridge university press; 2009. Causality. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Miñana E. Improving ecosystem services modelling: insights from a Bayesian network tools review. Environ. Model. Software. 2016;85:184–201. [Google Scholar]

- Rathfon D., Davidson R., Bevington J., Vicini A., Hill A. Quantitative assessment of post-disaster housing recovery: a case study of punta gorda, Florida, after hurricane charley. Disasters. 2013;37(2):333–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2012.01305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reutlinger A. Is there a monist theory of causal and noncausal explanations? The counterfactual theory of scientific explanation. Philos. Sci. 2016;83(5):733–745. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues P.P., Ferreira-Santos D., Silva A., Polónia J., Ribeiro-Vaz I. Causality assessment of adverse drug reaction reports using an expert-defined Bayesian network. Artif. Intell. Med. 2018;91:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothan H.A., Byrareddy S.N. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J. Autoimmun. 2020;109:102433. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesseling M., Wigersma L., van der Wal G. Assessment model for the justification of intrusive lifestyle interventions: literature study, reasoning and empirical testing. BMC Med. Ethics. 2016;17(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s12910-016-0097-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanin M., Lillo F. Modelling the air transport with complex networks: a short review. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2013;215(1):5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Liu T., Zhao S., Chen Y., Nie J.Y. Event causality extraction based on connectives analysis. Neurocomputing. 2016;173:1943–1950. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C., Wu J., Liu M., et al. Cyber-physical resilience modelling and assessment of urban roadway system interrupted by rainfall. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020;204:107095. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman C., Hossain M., Watts C. Human trafficking and health: a conceptual model to inform policy, intervention and research. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011;73(2):327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]