Abstract

Background

Pancreatitis in cats, although commonly diagnosed, still presents many diagnostic and management challenges.

Objective

To summarize the current literature as it relates to etiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of pancreatitis in cats and to arrive at clinically relevant suggestions for veterinary clinicians that are based on evidence, and where such evidence is lacking, based on consensus of experts in the field.

Animals

None.

Methods

A panel of 8 experts in the field (5 internists, 1 radiologist, 1 clinical pathologist, and 1 anatomic pathologist), with support from a librarian, was formed to assess and summarize evidence in the peer reviewed literature and complement it with consensus clinical recommendations.

Results

There was little literature on the etiology and pathogenesis of spontaneous pancreatitis in cats, but there was much in the literature about the disease in humans, along with some experimental evidence in cats and nonfeline species. Most evidence was in the area of diagnosis of pancreatitis in cats, which was summarized carefully. In contrast, there was little evidence on the management of pancreatitis in cats.

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

Pancreatitis is amenable to antemortem diagnosis by integrating all clinical and diagnostic information available, and recognizing that acute pancreatitis is far easier to diagnose than chronic pancreatitis. Although both forms of pancreatitis can be managed successfully in many cats, management measures are far less clearly defined for chronic pancreatitis.

Keywords: cat, diagnosis, etiology, gastroenterology, management, pancreas, pancreatitis, pathophysiology

1. INTRODUCTION

Pancreatitis historically has been considered rare in cats, but current evidence suggests that this disease is quite common, similar to the situation in both humans and dogs. 1 In a study of 115 cats undergoing necropsy at the University of California Davis, the overall histopathologic prevalence of pancreatitis was 66.1%, with 50.4% of cats having evidence of chronic pancreatitis alone, 6.1% having evidence of acute pancreatitis alone, and 9.6% having evidence of both acute and chronic pancreatitis. Also, 45% of the apparently healthy cats had evidence of pancreatitis. 1 This finding raises the question as to whether there is a population of cats with subclinical pancreatitis or whether the current histopathologic definition of pancreatitis leads to overdiagnosis and needs clarification. In contrast to these histopathological data, clinical pancreatitis is diagnosed much less frequently in cats, but the consensus panel agrees that the frequency of a diagnosis of pancreatitis has increased steadily over the last 2 decades, mainly because of an increased level of awareness and availability of noninvasive and minimally invasive diagnostic tests. Management of pancreatitis in cats remains challenging and definitive treatments are currently unavailable.

2. DEFINITION

Although in humans the definition and classification of pancreatitis have been standardized by integrating different medical disciplines, the classification of pancreatitis in cats lacks standardization. 2 , 3 In general, acute pancreatitis is characterized by inflammation that is completely reversible after removal of the inciting cause, whereas chronic pancreatitis results in irreversible histopathologic changes. 1 , 4 The differences between acute and chronic pancreatitis are mainly histopathologic, and not necessarily clinical. 5 Thus, it may be impossible clinically to distinguish an exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis from an episode of acute pancreatitis. 4 , 6

Both acute and chronic pancreatitis can be mild or severe, but chronic cases are more commonly mild and acute cases more commonly severe. Clinically, mild pancreatitis is associated with few systemic complications, minimal pancreatic necrosis, and generally a low mortality, although morbidity may be impacted by concurrent diseases. In contrast, clinically severe pancreatitis is characterized by extensive pancreatic necrosis, multiple organ involvement or even failure, and in some cases a poor prognosis. 7

Pancreatitis can be accompanied by uncommon pancreatic complications, the terminology of which historically has been confusing in cats. In humans, the current consensus statement defines acute peripancreatic fluid accumulations, acute necrotic collections or, late after the onset of acute pancreatitis, pseudocysts or walled‐off necrosis; each may be sterile or infected with bacteria. 2 These fluid accumulations have been described previously as phlegmons or abscesses in cats. 2 , 7

3. ETIOLOGY

Pancreatitis has no age, sex, or breed predisposition. 1 Additionally, associations with body condition score, dietary indiscretion, or drug history have not yet been established in cats.

Although pancreatitis has been observed in cats with various infections, including certain parasites (eg, Toxoplasma gondii, Eurytrema procyonis, Amphimerus pseudofelineus) and viruses (eg, coronavirus, parvovirus, herpesvirus, calicivirus), these infections represent rare causes of pancreatitis in cats. 6 , 8 , 9 , 10 Intraoperative manipulation of the pancreas and pancreatic biopsy have been suggested as risk factors for the development of pancreatitis, but hypotension associated with anesthesia may be more important than pancreatic manipulation. 1 Although pancreatic injury is possible with manipulation, an increased risk for the development of pancreatitis has not been noted in studies involving pancreatic sampling. 11 , 12 Neoplasia involving the pancreas has been associated with pancreatitis, but is not diagnosed commonly in cats. 13 Pancreatic trauma after road accidents or falling from high buildings, potentially resulting in pancreatic ischemia, has been established as a cause. 14 Two cases of pancreatitis in cats after topical use of fenthion, an organophosphate cholinesterase inhibitor, have been reported. 15 Many other pharmaceutical compounds, such as potassium bromide or phenobarbital, have been implicated in causing pancreatitis in humans and dogs, but have not been reported to cause pancreatitis in cats. 16 , 17 Hypercalcemia and snake bites have been reported to rarely cause acute pancreatitis in other species and in experimental models in cats. 18 , 19 , 20

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) occurs uncommonly in people. It can be categorized as type 1 when the pancreas is involved in a multisystemic fibro‐inflammatory disease (also known as immunoglobulin 4 [IgG‐4]‐associated systemic disease) and as type 2, which has been associated with chronic enteropathy. 21 The presence of IgG4‐staining cells in the pancreas and incidence of circulating antibodies against the pancreas have not been established in cats, but response to immunosuppressive therapy with chronic pancreatitis may suggest an immune‐mediated etiology in some cats.

Pancreatitis in cats has been associated with several concurrent diseases, including diabetes mellitus, chronic enteropathies, hepatic lipidosis, cholangitis, nephritis, and immune‐mediated hemolytic anemia. 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 Whether these conditions cause, or are risk factors for, pancreatitis has not been determined. 23 , 24 , 27 In summary, > 95% of cases of pancreatitis in cats are considered to be idiopathic, and a specific cause cannot be identified.

4. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Premature activation of pancreatic digestive enzymes within acinar cells, leading to activation of other zymogens and resulting in pancreatic autodigestion, is assumed to play an important role in the pathogenesis of pancreatitis in both humans and cats (Figures 1, 2, 3). The pancreas has several safeguards in place to protect against activation of zymogens of digestive enzymes (ie, inactive preforms of digestive enzymes) within acinar cells (Figure 1A). 28 , 29 , 30 , 31

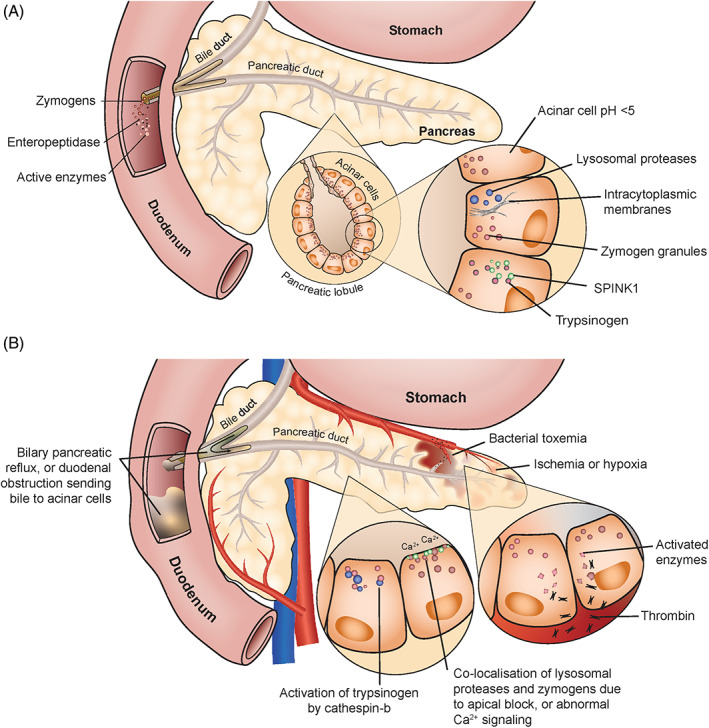

FIGURE 1.

Mechanisms that protect the pancreas from premature activation of zymogens (panel A). Events that can lead to acute pancreatitis due to premature activation of trypsinogen (panel B)

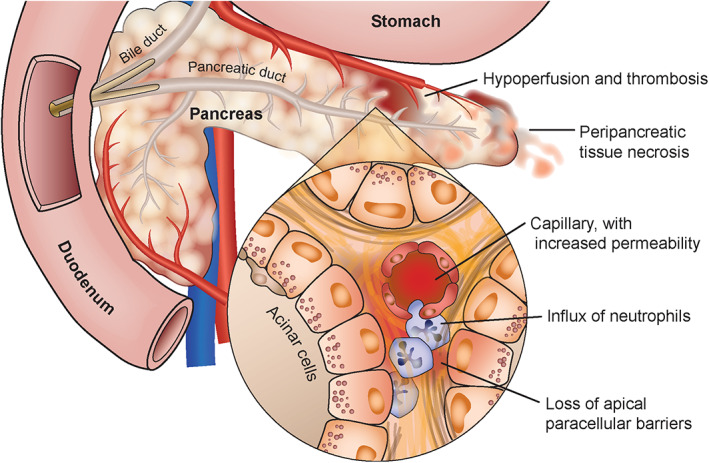

FIGURE 2.

Local and systemic inflammation ensues in acute pancreatitis, which is independent of trypsin activation, but dependent on ongoing stimulation of the NFκB pathway

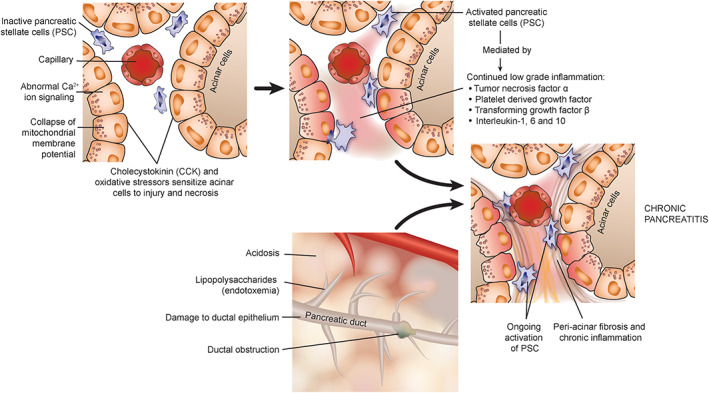

FIGURE 3.

The pathophysiological mechanisms relevant for chronic pancreatitis that occur independently of trypsin activation and acute pancreatitis

Hypotheses for the spontaneous development of pancreatitis (Figure 1B) include autoactivation of cationic trypsinogen (more likely when pH ≥5.0) 29 , 30 ; activation of zymogens by thrombin during bacterial toxemia, ischemia, or hypoxia 29 ; colocalization of lysosomal proteases and zymogen granules (because of an apical block of zymogen granule secretion) 29 ; activation of trypsinogen by cathepsin B 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ; and, enterokinase entering the portal circulation after a meal in conjunction with biliary‐pancreatic reflux, which may cause zymogen activation. 29

Over the past 3 decades, studies have concluded that trypsinogen activation within the pancreas is the initiating event for acute pancreatitis. 33 , 34 However, there is no consensus on how this inciting event unfolds. Recent hypotheses postulate that abnormalities in calcium signaling lead to the colocalization of lysosomes and zymogen granules and trypsinogen activation, causing acinar cell death and early activation of the nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) pathway. 35 , 36 , 37 However, the local and systemic inflammation that ensues in acute pancreatitis is independent of trypsin activation, but dependent on ongoing stimulation of the NFκB pathway. 38 , 39 The events that follow include an influx of neutrophils, increased vascular permeability, and loss of apical paracellular barriers. All of these events worsen acinar cell, organ, vascular, and systemic injury. 40 The extent of systemic inflammation in an individual cat depends on the degree of compensatory anti‐inflammatory responses that are present. 41 This proposed cascade of systemic inflammatory and compensatory anti‐inflammatory pathways during acute pancreatitis has been described extensively in experimental rodent models and people, but it is unknown whether this cascade also occurs in cats. 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48

Hypoperfusion and thrombosis also may serve as triggers for the development of peripancreatic necrosis. 40 Additionally, high concentrations of bile acids or trypsin within the pancreatic circulation may contribute to the development of necrosis, although this has been identified only in a feline pancreatitis model. 49 Overall, most experimental models of pancreatitis fail to replicate the events that occur in vivo in cats. However, it has been shown that cats do have increased pancreatic permeability in response to infusion of some substances, such as ethanol, but not sterile bile. 50 , 51 Experimentally, infusion of infected bile into the pancreatic duct induced severe pancreatitis, but when bacteria suspended in saline were infused, only mild pancreatitis developed. 50 , 51 The unique anatomy of the cat, with shared entry of the common bile duct and the pancreatic duct into the duodenum, may explain the association between acute cholangitis or bacterial cholecystitis and pancreatitis.

When chronic pancreatitis occurs independently of acute pancreatitis, trypsin activation is not considered the inciting event. 52 Studies suggest that cholecystokinin and oxidative stress synergistically sensitize pancreatic acinar cells to injury and necrosis, independent of trypsin activation. 53 This occurs via calcium ion signaling and collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential.

In people, an acute initial insult, which may lead to subclinical disease, exposes the pancreas to oxidative stress that causes activation of pancreatic stellate cells (PSC). 54 These PSCs are the source of fibrosis and, if exposed to continued stimulation by low‐grade inflammation (ie, platelet‐derived growth factor, transforming growth factor β, tumor necrosis factor α, and interleukins [IL]‐1, IL‐6, and IL‐10), or recurrent oxidative stress, periacinar fibrosis develops. 55 Also, lipopolysaccharides can activate PSCs by activation of toll‐like receptor‐4, suggesting a potential role of endotoxemia in the pathogenesis of pancreatic fibrosis. 56 Additionally, metabolites accumulate within the pancreas because of decreased blood flow and potentially acidosis and low‐grade ongoing activation of trypsinogen to trypsin. 57 Ductal obstruction may develop as part of this process, further exacerbating the low‐grade inflammation and fibrosis. This may occur because of precipitation of protein and calcium in the duct after a decrease in bicarbonate secretion, as well as decreased fluid volume of pancreatic secretions. 56 In feline experimental models, chronic pancreatitis may result from simple obstruction of the pancreatic duct, but this is unlikely to be the primary pathogenesis in naturally occurring disease. 50 , 51 Damage to the ductal epithelium independent of ductal obstruction has been shown experimentally to be essential for development of chronic pancreatic inflammation in cats. 58

Primary inflammation in neighboring abdominal organs, such as the biliary system or the intestines, also may cause inflammatory changes within the pancreas by upregulation of inflammatory mediators, their receptors, or both. 56

5. CLINICAL SIGNS

Clinical signs and physical examination findings associated with both acute and chronic pancreatitis in cats are nonspecific (see Table 1). The presenting signs in each case help to categorize the severity of the disease. Interestingly, in contrast to people, where abdominal pain is considered a hallmark finding of the disease, cats with pancreatitis infrequently are reported to have abdominal discomfort. However, the panel feels that this discrepancy is most likely because of under‐recognition of abdominal pain in cats. Additional clinical signs may be caused by concurrent diseases. 59

TABLE 1.

Incidence of clinical signs and physical examination findings reported in cats with pancreatitis 11 , 15 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63

| Clinical sign | Incidence % |

|---|---|

| Lethargy | 51‐100 |

| Partial/complete anorexia | 62‐97 |

| Vomiting | 35‐52 |

| Weight loss | 30‐47 |

| Diarrhea | 11‐38 |

| Dyspnea | 6‐20 |

| Physical examination finding | Incidence % |

|---|---|

| Dehydration | 37‐92 |

| Hypothermia | 39‐68 |

| Icterus | 6‐37 |

| Apparent abdominal pain | 10‐30 |

| Hyperthermia/fever | 7‐26 |

| Abdominal mass/cranial abdominal organomegaly | 4‐23 |

6. DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

6.1. Radiography

Abdominal radiography is neither sensitive nor specific for the diagnosis of pancreatitis in cats. 64 The left lobe of the pancreas occasionally can be identified on ventrodorsal radiographs in cats with pancreatitis. Radiographic signs of severe pancreatitis in cats can include loss of peritoneal detail in the cranial abdomen or a mass effect. Although both can be assessed by radiography, neither finding is specific for pancreatitis. 65

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography has been reported in healthy cats as a contrast fluoroscopic technique to assess the biliary tract and the exocrine pancreas, but is technically challenging, requiring special equipment and expertise, and is not yet established as a diagnostic test in cats. 66

6.2. Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography remains the most routine diagnostic imaging modality for cats suspected of having pancreatitis and should be considered part of the minimum database in these cats. Furthermore, cats with gastrointestinal signs may have comorbidities of the intestines, liver, and gallbladder, which also can be assessed using this modality. 67

Although high frequency transducers (>7.5 MHz), either curved or linear array, allow good visualization of the feline pancreas, pancreatic duct, surrounding mesentery, and vasculature, some limitations remain. These include ultrasonographer experience and lack of specificity to differentiate normal pancreas from acute or chronic pancreatitis and to differentiate hyperplasia from neoplasia when nodules or masses are detected. 68

After clipping the ventral abdomen, swabbing with alcohol, and applying ultrasound gel, the examination begins by identifying the portal vein at the porta hepatis, where the blood vessels and the common bile duct exit the liver. The portal vein then is traced caudally to the caudal border of the stomach where the pancreatic body can be seen ventral to the portal vein. 69 The normal pancreas is isoechoic or hypoechoic compared to the surrounding mesentery and is similar in echogenicity to the liver. The left lobe of the pancreas is located between the caudal curvature of the stomach and the cranial border of the transverse colon and is more readily visible than the right lobe. 70 The pancreatic duct usually is identified as a small hypoechoic tubular structure centrally located within the left lobe of the pancreas. The right pancreatic lobe is small and can be difficult to identify. It is best located by tracing the pancreatic body to the right of the portal vein and searching medial to the duodenum.

The thickness of the left lobe ranges from 5‐9 mm, whereas the right lobe is 3‐6 mm. 70 In cats <10 years of age, the mean duct diameter has been reported as 0.8 ± 0.25 mm and in cats >10 years of age as 1.2 ± 0.4 mm (ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 mm) in diameter. 70 , 71

Sonographic findings in acute pancreatitis in cats (Figure 4) may be equivocal or may include pancreatic enlargement, a hyperechoic surrounding mesentery, and focal abdominal effusion. 65 The duodenum can be distended or corrugated. The sensitivity of these findings for diagnosing acute pancreatitis in cats has been reported to range between 11% and 67%, and sensitivity is considered to be severity‐dependent and operator‐dependent. 65 Pancreatic ultrasonography has developed over the last 3 decades and thus results of the various papers reporting on sensitivity may not be directly comparable.

FIGURE 4.

Sagittal plane abdominal ultrasound image of the left pancreatic limb in a cat with acute pancreatitis performed with an 8.5 MHz curved array transducer. The left limb of the pancreas is enlarged (1.65 cm), diffusely hypoechoic, and surrounded by a halo of hyperechoic mesentery

Ultrasonographic features of chronic pancreatitis (Figure 5) are not well established in cats. 59 , 72 Findings may include a hyperechoic or mixed echoic pancreas, a dilated common bile duct, enlarged pancreas, and irregular pancreatic margins. 72 Because of overlap between these features and those of acute pancreatitis, ultrasonography is a poor diagnostic tool for assessing chronicity. 59

FIGURE 5.

Sagittal plane abdominal ultrasound image using an 8.5 MHz curved array transducer of the left pancreatic limb of a cat with chronic pancreatitis. The pancreas is mildly enlarged at 1.5 cm (X‐X). The pancreatic parenchyma is diffusely heterogenous and has a mottled echotexture. The surrounding mesentery is unremarkable

Pancreatic nodular hyperplasia can be an incidental finding in older cats. 68 Compatible findings include parenchymal nodules up to 1 cm in diameter, in addition to pancreatic enlargement. Overlap exists among ultrasonographic findings in cats with pancreatitis, benign nodules, and malignant ones. Morphologic tissue evaluation is necessary to differentiate among them. 70

Abdominal ultrasound examination also can be used to collect cytological samples. Ultrasound‐guided fine‐needle aspiration of the feline pancreas frequently is performed using a 20G or 22G hypodermic or spinal needle and is safe in cats, including those with pancreatitis. 73 An optimal technique has not been determined. One study found a 67% cell recovery rate of diagnostic samples (24/73 samples were nondiagnostic). 73 To optimize sample distribution for microscopic evaluation, samples obtained by fine‐needle aspiration should be smeared gently and quickly, as would be done with peripheral blood. 74 Pancreatic acinar cells deteriorate quickly, because of release of digestive enzymes, making rapid cell preservation imperative. 75

6.3. Advanced imaging modalities

Contrast‐enhanced Doppler ultrasonography of the pancreas has not gained wide use in cats for the diagnosis of pancreatitis. 76 , 77

Recent studies have established the multiphase contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) features of the normal and abnormal feline pancreas. 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 The pancreas in healthy cats enhances homogenously on arterial, portal, and delayed phase scans. The pancreas is hypoattenuating or isoattenuating to the liver and spleen on precontrast scans. 82 Mean widths of the left limb, body, and right limb determined by CT are similar to those of the same regions obtained by ultrasonography. 71 , 80 , 83

On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the normal pancreas in cats is T1 hyperintense and T2 isointense to hypointense. 84 , 85 Magnetic resonance imaging features of suspected pancreatitis in 10 cats included T1 hypointensity and T2 hyperintensity of the parenchyma, enlargement of the pancreas, pancreatic duct dilatation, and contrast enhancement. 85 Nine cats had enlargement of the pancreas >10 mm in thickness, 5 cats had pancreatic duct diameters >2.5 mm, whereas 2 had peripancreatic hyperintensity.

None of these advanced imaging modalities have yet been established as a routine diagnostic tool for pancreatitis in cats.

7. CLINICAL PATHOLOGY

7.1. General clinical pathology

A complete blood count (CBC), routine serum or plasma biochemistry profile, and urinalysis are part of the minimum database obtained for evaluation of any sick patient. Although these tests are not specific for the diagnosis of either acute or chronic pancreatitis in cats, they are helpful in eliminating other differential diagnoses and assessing the patient for comorbidities or complications. 86

Hematologic findings in cats with pancreatitis vary. In cats with acute pancreatitis, indicators of erythrocyte mass (eg, red blood cell number, hematocrit or packed cell volume) may be increased secondary to dehydration from fluid loss as a result of decreased intake, vomiting, diarrhea, or some combination of these. An inflammatory leukogram, characterized by neutrophilia with a left shift or neutropenia may be present, particularly with acute pancreatitis. In severe cases, evidence for hypocoagulability with disseminated intravascular coagulation may be present, as evidenced by prolonged clotting times, often occurring concurrently with thrombocytopenia and increased fibrin degradation products (FDPs), D‐Dimers, or both. 86

Changes on the routine serum or plasma biochemical profile also are variable and unpredictable. Hepatic enzyme activities (eg, alanine amino transferase [ALT], aspartate transaminase [AST]) and total bilirubin concentrations may be increased because of concurrent inflammation of the biliary tree, extrahepatic biliary obstruction, hepatic lipidosis, or some combination of these. 86

Serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) concentrations may be increased as a result of dehydration. In cats with severe acute pancreatitis, azotemia and low urine specific gravity may result from acute kidney injury, secondary to hypoxemia, impaired renal microcirculation, or hypovolemia. 87 Azotemia has been linked to progression of the disease. 63 Hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia can be seen with acute necrotizing and suppurative pancreatitis, and hypoglycemia has been associated with poor outcome. 15 , 63

In other species, pancreatitis is associated with hyperlipidemia, consisting of increased serum triglyceride or cholesterol concentrations, or both. 88 , 89 , 90 In cats however, hypertriglyceridemia is rare and no association of hypertriglyceridemia with pancreatitis has been reported. 86 , 88 , 91 Changes in serum electrolyte concentrations are variable, particularly depending on the hydration status of the patient, but hypokalemia, hypochloremia, hyponatremia, and hypocalcemia are the most common electrolyte abnormalities in cats with severe acute pancreatitis. 86

7.2. Lipase

Pancreatic acinar cells synthesize and secrete a wide variety of digestive enzymes (eg, amylase, lipase, DNAse, and RNAse) and inactive preforms of digestive enzymes (zymogens; eg, trypsinogen, chymotrypsinogen, proelastase, prophospholipase), which are all released into the small intestine via the pancreatic duct. 92 However, small amounts of these enzymes and zymogens reach the vascular space. In principle, when the pancreas undergoes inflammation or damage, zymogen granules leak from the acinar cells into the interstitial space, ultimately reaching the vascular space.

Measurement of any pancreatic enzyme or zymogen theoretically could be used as a diagnostic marker for acinar cell damage and pancreatitis. However, some enzymes are very small or are scavenged by inhibitors or both, and are rapidly cleared from the bloodstream. The source of other enzymes is not limited to pancreatic acinar cells. Thus, an ideal marker for pancreatitis would be one that is synthesized only by acinar cells and not cleared immediately from the vascular space. Pancreatic lipase fulfills these criteria, but to be useful as a biomarker, the molecule must be measured using an assay specific for pancreatic lipase, which can be problematic.

Many lipases exist in the body, some of which occur in large quantities, such as pancreatic lipase or gastric lipase. Various substrates are utilized for lipase activity assays, including 1,2‐diglycerides, triolein, and 1,2‐o‐dilauryl‐rac‐glycero glutaric acid‐(6′‐methylresorufin) ester (DGGR; eg, PSL by Antech Laboratories, Fountain Valley, CA), but, despite choosing favorable conditions for measurement of pancreatic lipase, none have shown to be specific for the measurement of pancreatic lipase to date. 93 Shortly after DGGR was introduced for the measurement of serum lipase activity in humans, studies showed that DGGR‐based assays not only measure pancreatic lipase, but also hepatic and lipoprotein lipase, pancreatic lipase‐related protein 2 (PLRP2), various esterases, and even hemoglobin. 93 Although not demonstrated in cats per se, it has been shown that PLRP2 is synthesized in many extrapancreatic tissues in dogs, such as gastric mucosa and renal parenchyma (ahead of print, S. Lim, Texas A&M University). 94 Also, stimulation of hepatic and lipoprotein lipase release by heparin administration in cats leads to an increase in serum lipase activity as measured by DGGR. 94 Theoretically, the lack of specificity of DGGR‐based lipase assays can be overcome by changing cutoff values for the diagnosis of pancreatitis, but doing so causes a decrease in sensitivity.

Few reports are available concerning the use of serum lipase activity for the diagnosis of pancreatitis in cats. In an older study that employed 1,2‐diglyceride as a substrate, none of 12 cats with severe acute pancreatitis had serum lipase activity outside the reference interval and serum lipase activities did not differ significantly among healthy cats, cats with severe acute pancreatitis, and cats with extrapancreatic diseases. 95 In another study, the correlation of a DGGR‐based lipase assay with Spec fPL (Idexx Laboratories, Westbrook, ME; see below) concentration was evaluated in 161 cats and Cohen's kappa coefficient was reported to be 0.7, indicating discordance. 72

Another means of measuring lipase is to measure serum pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (fPLI). A commercial ELISA for the measurement of fPLI, Spec fPL, is available. Fewer articles have been published concerning measurement of PLI as a diagnostic test for pancreatitis in cats than for dogs. However, most of the data suggest that the measurement of fPLI is highly specific for the measurement of pancreatic lipase and also is sensitive for the diagnosis of pancreatitis. 72 , 96 , 97 , 98 However, it should be noted that sensitivity is higher for severe cases than for mild cases. 99 One retrospective study reported a positive predictive value of 90% and a negative predictive value of 76% for Spec fPL in 275 sick cats. 100 The authors suggested that a positive Spec fPL result indicated pancreatitis as a probable diagnosis, but that the test cannot be used to rule out pancreatitis. 100 However, cases in this study were not further categorized based on severity or acute vs. chronic disease. 100 One study reported lower diagnostic accuracy in cats with pancreatitis than did other studies, the reason for this discrepancy is unclear. 72 It remains to be further studied whether, as in dogs, inflammatory diseases of other organs (eg, chronic enteropathy, peritonitis) may be associated with pancreatic inflammation and an increase in serum PLI concentration in cats. 101

Several commercial assays are available for the measurement of fPLI concentration. Although none have been analytically validated in the primary literature, the Spec fPL has been analytically validated in a panel member's laboratory and has been used for several clinical studies published in the primary literature. 96 , 98 , 102 Another commercial fPLI assay by Laboklin (Bad Kissingen, Germany) failed analytical validation. 100 , 103

At least 2 patient‐side assays are available for the immunologic measurement of pancreatic lipase. The SNAP fPL (Idexx Laboratories, Westbrook, ME) is a semiquantitative test that has been shown to correlate well with the Spec fPL and reports results as either “normal” or “abnormal.” 96 Cats with a “normal” result are unlikely to have pancreatitis, whereas those with an “abnormal” result might have pancreatitis or a Spec fPL in the equivocal range. Another patient‐side assay, the VCheck fPL (Bionote, Hwaseong, Korea), is available in parts of Asia. Although this species‐specific assay has not yet been assessed in the primary literature, the VCheck cPL for use in dogs failed analytical validation. 104

Agreement between DGGR‐lipase (cutoff, 26 U/L) and Spec fPL (cutoff, >5.3 μg/L) has been reported to have a κ of 0.68 1 and 0.70, 2 which is considered good when comparing results of subjective diagnostic modalities, but less so for objective ones. There also is poor agreement between the ultrasonographic diagnosis of pancreatitis and DGGR‐lipase (cutoff, 26 U/L) or Spec fPL (cutoff, >5.4 μg/L), with κ = 0.22 and κ = 0.26, respectively. 2 The highest agreement of both types of increased serum lipase results was with hypoechoic or mixed echogenic pancreatomegaly. 2 Another study reported poor agreement between pancreatic histology and DGGR assay results (cutoff, >26 U/L) or Spec fPL assay (cutoff, >3.5 μg/L), with κ = 0.06 and κ = 0.10, respectively. 3 However, this study postulated that mild infiltration of the pancreas with inflammatory cells should be considered normal. 3 , 72

7.3. Additional laboratory tests

Historically, increases in serum amylase activity have been associated with acute pancreatitis in some cats. However, because of both, poor diagnostic sensitivity and lack of tissue specificity, enzymatic activity of amylase has minimal utility as a biomarker for pancreatitis in cats. 86 , 94 , 105

Trypsin‐like immunoreactivity (TLI) measures trypsinogen, trypsin, and likely some trypsin that has been bound by protease inhibitors and is measured using a species‐specific immunoassay. Studies indicate variable results in cats with pancreatitis, with sensitivity ranging from 30‐86%. 105 , 106 Because trypsinogen is produced by pancreatic acinar cells, some cats with chronic pancreatitis and subsequent pancreatic atrophy ultimately have a decreased serum fTLI, indicating exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Also, increased serum fTLI concentrations previously have been associated with acute pancreatitis in cats. 106 However, this test is nonspecific and increased serum fTLI concentrations also have been associated with chronic enteropathy and gastrointestinal lymphoma, and may occur in cats with a decreased glomerular filtration rate 86 , 105 Thus, the utility of fTLI for the diagnosis of pancreatitis in cats is limited.

Trypsinogen activation peptide (TAP) is a byproduct of trypsinogen activation that normally is excreted in the urine. In health, this N‐terminal peptide is present in very low concentrations in both urine and serum. 105 In cats with acute pancreatitis, TAP is formed at a higher rate because of rapid cleavage of trypsinogen by cathepsin B or through autoactivation. 107 Although initially considered to be a promising biomarker for the detection of pancreatitis, inconsistent performance characteristics and lack of commercial availability limit the utility of this analyte. 107

7.4. Cytology

Cytology allows for close examination of a focal area of aspiration, but individual aspirates may not be representative of the tissue as a whole. With acute pancreatitis, pancreatic aspirates often are highly cellular. They are characterized by inflammatory cells, predominantly neutrophils, that show variable degrees of degeneration with fewer foamy macrophages on a background of amorphous, necrotic debris, which occasionally contains refractile crystalline material (Figure 6). 74 , 108 The inflammatory cells often are closely associated with pancreatic acinar cells, with fewer ductal epithelial cells. 74 In the presence of inflammation, acinar cells may appear dysplastic, with evidence for cytomegaly, karyomegaly, prominent nucleoli, and increased cytoplasmic basophilia. 74 It is extremely difficult to distinguish cytologically between primary pancreatitis with dysplastic epithelial cells and an inflamed pancreatic carcinoma. 74 , 108 , 109 , 110 However, pancreatic neoplasia is rare in cats and is considered much less likely. 13

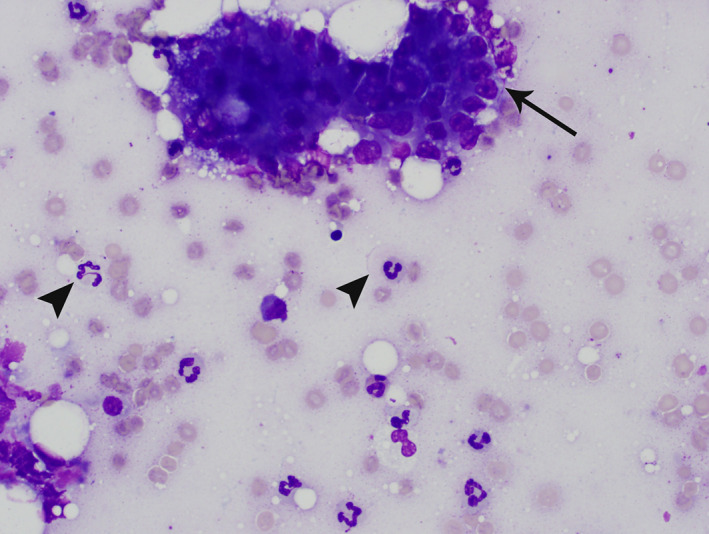

FIGURE 6.

Pancreatic aspirate from a cat. Modified Wright's stain. 50× magnification. There is a cluster of acinar cells (arrow) surrounded by erythrocytes and many nondegenerate neutrophils (arrowheads), consistent with suppurative pancreatic inflammation

With chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic aspirates often are poorly cellular, because of the presence of fibrosis, which occasionally forms 1 or more mass‐like lesions. 110 Mesenchymal cells, including reactive fibroblasts, typically exfoliate poorly. Variable numbers of mixed inflammatory cells often are present, including lymphocytes and plasma cells with occasional neutrophils.

However, in both acute and chronic pancreatitis, the absence of inflammatory cells should not preclude a clinical diagnosis of pancreatitis, because inflammatory infiltration can be highly localized, especially with chronic disease. 74 , 108 , 109 , 110

Particularly with acute pancreatitis, a focal fluid accumulation may occur adjacent to the pancreas. Microscopic evaluation of this fluid after aspiration can be done by cytology or by histology after preparation of a cell block. 111 Laboratory analysis of the fluid typically discloses a high protein concentration with variable cellularity, resulting in a classification of high‐protein transudate (modified transudate) or exudate. The background of the fluid often contains blood, mineral, and free lipid. Nucleated cells primarily are variably degenerate neutrophils and activated macrophages, which often contain crisp, distinct lipid vacuoles, hemosiderin, or both, indicative of fat saponification and prior hemorrhage, respectively. 108

8. PATHOLOGY

For collection of pancreatic biopsy specimens in cats, surgical or laparoscopic biopsy procedures have been shown to have a low risk for complications. 112 Detailed descriptions of these procedure have been published. 113

Histologic analysis of pancreatic biopsy specimens has been widely considered the gold standard for antemortem diagnosis of pancreatitis in cats, 1 , 59 although limitations exist because of variable localization, considerable differences in description of the lesions, and definition of severity. 1 When evaluating tissue biopsy specimens from cats with suspected pancreatitis, the accuracy of histologic diagnosis can be limited by the multifocal distribution of lesions in cats with both acute and chronic pancreatitis. 1 , 15 , 65 In 1 study, only half of the cats diagnosed with pancreatitis had lesions identified in all 3 regions of the pancreas. 1 Thus, multiple biopsies are recommended, and pancreatitis should not be excluded based on negative biopsy results alone. 8 If only 1 biopsy can be performed, biopsy of the left lobe is preferred. 1 No available study correlates microscopic findings with clinical disease classification or severity. Mild histologic changes must be interpreted with caution because it is not possible to determine which lesions are relevant clinically. 114 Pancreatic biopsy specimens, not to exceed 1 cm3 to ensure proper fixation, should be placed immediately into 10% neutral buffered formalin at a ratio of 10:1 (fixative to tissue) and stored at room temperature until submission. 115

Pancreatic histomorphology can be affected by the sensitivity of the pancreas to hypoxemia, whether induced by hypotension during anesthesia or impairment of pancreatic blood flow after manipulation of other organs during surgery. 116

8.1. Gross lesions of the pancreas

When performing a laparotomy, gross lesions may not always be apparent in cats with pancreatitis, but findings suggestive of pancreatic inflammation should be noted and communicated to the pathologist. 15 , 65 These are, in cases of acute pancreatitis, peripancreatic fat necrosis, focal peritonitis, or pancreatic hemorrhage, edema, and congestion or, in cases with severe pancreatic necrosis, fibrin strands that pass from the pancreatic surface to the omentum, mesentery, or visceral surfaces of the liver. 117 Gross lesions of chronic pancreatitis often are more subtle, but in severe cases, the pancreas may be small with a firm, gray, multinodular appearance, 117 or with a dull granular capsular surface. 118 Adhesions to the small intestine also may be present. 116

8.2. Histologic classification and interpretation

Although the relevance of histologic classification of pancreatitis in cats, especially with respect to clinical findings and prognosis, remains unclear, 5 some histologic standards for the classification of pancreatic inflammatory disease in cats are provided.

In general, interpretation of pancreatic biopsy specimens should include evaluation of inflammatory cell infiltrates as well as their spatial distribution (ie, intralobular vs. interlobular) and the presence of edema, necrosis, fibrosis, amyloid, cystic acinar degeneration, or acinar atrophy. 1 The consensus panel agreed that these histologic findings should be reported following a previously published scoring system, which has been slightly modified by the consensus panel (Table 2). 1 This system can be used for routine diagnostic pathology and may advance the understanding of pancreatitis in cats. 1 The extent of concurrent acute and chronic inflammatory changes of the pancreas is debated. The histopathology report should specify whether pancreatitis is acute, acute on chronic (chronic active), or solely chronic. This distinction likely is clinically relevant because of the potential long‐term sequelae of chronic disease, such as exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and diabetes mellitus. 5

TABLE 2.

Semiquantitative histopathology scoring system for pancreatitis in cats

| Acute pancreatitis | Chronic pancreatitis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute suppurative pancreatitis | Acute necrotizing pancreatitis | ||||

| Lesion | Inflammation, neutrophilic | Edema and fat necrosis | Inflammation, lymphocytic/mononuclear | Fibrosis | Cystic degeneration |

| Score 0 | None | None | No or only isolated lymphocytes or erratic small nests of lymphocytes | None | None |

| Score 1 |

Mild infiltration (<25% of the parenchyma affected) |

Mild (<25% of the parenchyma affected) |

Mild mononuclear infiltrate (<25% of the parenchyma affected) |

Mild thickening of septa or multifocal areas of mild interstitial fibrosis (<15% of the parenchyma affected) | ≤3 cysts |

| Score 2 |

Moderate infiltration (25%‐50% of the parenchyma affected) |

Moderate (25%‐50% of the parenchyma affected) |

Moderate mononuclear infiltrate (25%‐50% of the parenchyma affected) |

Moderate thickening of most septa (15%‐30% of the parenchyma affected) |

4‐5 cysts |

| Score 3 |

Severe infiltration (>50% of the parenchyma affected) |

Severe (>50% of the parenchyma affected |

Severe mononuclear infiltration (>50% of the parenchyma affected) |

Severe thickening of all septa, dissecting the lobules (>30% of the parenchyma affected) |

≥6 cysts |

| Disease index | Total score: 1‐2 mild AP, 3‐4 moderate AP, 5‐6 severe AP | Total score: 1‐3 mild CP, 4‐6 moderate CP, 7‐9 severe CP | |||

Source: Modified from DeCock et al 1

Abbreviations: AP, acute pancreatitis; CP, chronic pancreatitis.

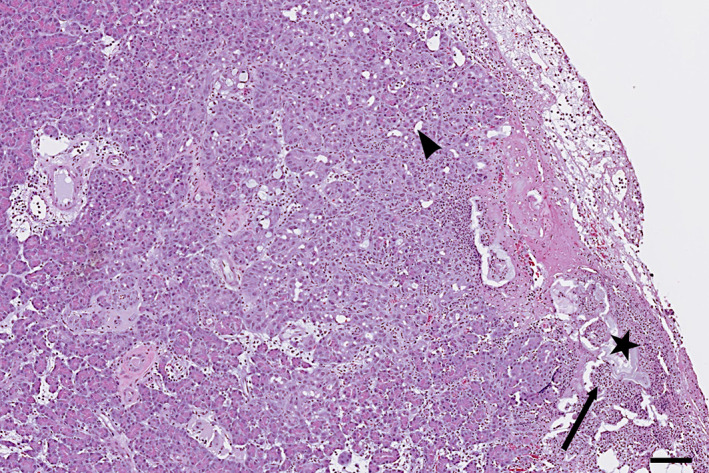

8.2.1. Acute pancreatitis

In general, pancreatic biopsy in cats with suspected moderate or severe acute pancreatitis is infrequently performed (Figure 7). Thus, the majority of knowledge of histologic changes in cats with acute pancreatitis is from necropsy material. 1 , 15 , 49 , 119

FIGURE 7.

Histopathologic image of acute pancreatitis in a cat showing fat necrosis (star) and focal suppurative infiltration (arrow) with early focal acinar‐to‐ductal metaplasia (arrowhead). Scale bar = 100 μm

One study divided acute pancreatitis in cats into 2 forms: acute necrotizing pancreatitis with substantial necrosis and acute suppurative pancreatitis where necrosis is not a feature. 15 This approach corresponds to the classification of acute pancreatitis in humans with a mild interstitial form with little or no necrosis and a severe necrotizing form. 120 Additional studies are needed to determine if these 2 morphologies are truly distinct in cats.

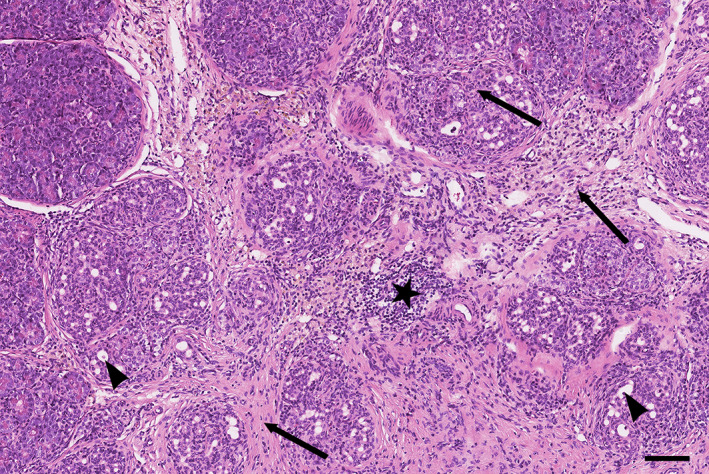

8.2.2. Chronic pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis in cats is characterized histologically by lymphocytic or lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, fibrosis, and acinar atrophy (Figure 8). 1 , 117 Retention cysts (ie, microscopic intraparenchymal cysts) may be visible and, although the most frequent type of pancreatitis in cats is mild, 1 , 116 fibrosis can be extensive throughout the interlobular septa and extend into the lobules in severe cases. 117 Extensive periductal fibrosis also may be present, leading to localized stenosis and cyst formation, with squamous metaplasia of the ductal epithelium. 117 Acinar‐to‐ductal metaplasia also can be present. Pancreatic neoplasia also can be associated with chronic pancreatitis. 13 Morphologically, chronic pancreatitis in cats resembles the most frequent type of chronic pancreatitis in humans, which is alcohol‐induced chronic pancreatitis. 121

FIGURE 8.

Histopathologic image of chronic pancreatitis in a cat, showing moderate lymphocytic infiltration (star), interlobular and intralobular fibrosis (arrows), and acinar‐to‐ductal metaplasia (arrowheads). Scale bar = 100 μm

9. MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE PANCREATITIS

Whenever possible, the inciting cause of acute pancreatitis should be removed or treated. However, doing so may be difficult, because most cases of pancreatitis are idiopathic in cats. Management is predominantly supportive and symptomatic (see Supplementary Tables 1, 2, and 3 for a formulary). 11 , 62 , 116 , 122 Most management recommendations are extrapolated from management recommendations for humans and dogs, expert opinion, or experimentally induced models of pancreatitis in cats. 8 , 19 , 41 , 49 , 116 , 123 , 124 , 125 , 126 , 127 , 128 , 129

Management of complications (eg, hepatic lipidosis, cholestasis, acute kidney injury, pneumonia, shock, myocarditis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, multiorgan failure) and diagnosis and treatment of comorbidities (eg, diabetes mellitus, diabetic ketoacidosis, cholangitis, chronic enteropathy) play an important part in successful management. In humans, no proven disease‐specific pharmacologic treatment changes the natural progression of acute pancreatitis, although new therapeutic targets and pharmacologic agents are on the horizon. 123 For example, recently, a leukocyte function‐associated antigen 1 (LFA‐1) antagonist was approved for the treatment of acute pancreatitis in dogs in Japan (personal communication, Joerg Steiner 2020). Management goals for acute pancreatitis are focused on fluid therapy, pain management, control of vomiting and apparent nausea, and nutritional support.

9.1. Treatment of inciting cause

Several diseases and risk factors have been associated with pancreatitis, some of which allow specific treatment. Some infectious agents that cause systemic disease, which may include pancreatitis, such as Toxoplasma gondii or others that rarely may cause pancreatitis, such as Amphimerus pseudofelineus or Erytrema procyonis infestation, are amendable to treatment. 9 , 10 , 130 However, because such cases are rare, generally there is no need to test for these organisms.

A careful drug history should be taken, and those drugs implicated in causing pancreatitis in cats or other species should be avoided if possible.

9.2. Fluid therapy

Intravenous crystalloid fluid is administered to correct dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. In addition to the adverse effects of hypovolemia, the pancreas also is susceptible to altered blood flow as a result of increased vascular permeability (because of inflammation and acinar cell injury) and microthrombi formation (because of hypercoagulability). 131 Establishing normovolemia using early IV fluid therapy may limit tissue damage by improving pancreatic perfusion and oxygen delivery. In humans, early aggressive hydration with lactated Ringer's solution hastens clinical improvement in patients with acute pancreatitis. 124 , 125 The duration of clinical signs before presentation to the hospital is directly proportional to the odds of death, which is attributed, at least in part, to hypovolemia. 63 Dehydration, inappetence, vomiting, and diarrhea can lead to hypoperfusion, resulting in metabolic acidosis and prerenal azotemia, which can be corrected by fluid therapy. Concurrent hypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis, and kidney disease may further contribute to metabolic acidosis. Further study is needed to determine the ideal fluid choice for the treatment of acute pancreatitis in cats, but lactated Ringer's or a similar solution (eg, acetated Ringer's) often is the first choice. Fluid therapy must be monitored closely to avoid overhydration.

9.3. Antiemetics and gastrointestinal prokinetics

Vomiting and apparent nausea often are noted in cats with pancreatitis, but less frequently than in dogs. Antiemetics are important to minimize fluid and electrolyte losses and to decrease the potential for regurgitation and secondary esophagitis. Adequately managing nausea and vomiting likely allows for earlier tolerance of either voluntary per os (PO) intake or tube feeding.

The most commonly used antiemetic in cats is maropitant citrate, a neurokinin1 receptor (NK1R) antagonist, which acts both centrally and peripherally by inhibiting the binding of substance P to the NK1R located in the vomiting center, chemoreceptor trigger zone, and the gastrointestinal tract. 132 , 133 , 134 Both injectable and orally‐administered maropitant is used commonly to treat vomiting in cats. 133 Maropitant may have additional benefits, such as visceral analgesia and anti‐inflammatory activity. 134 , 135 Ondansetron is a 5‐hydroxytryptamine3 (5HT3) receptor antagonist that inhibits serotonin‐induced stimulation of vagal afferent activity and also can be used as primary or additive antiemetic. Because maropitant and 5HT3 antagonists work by different mechanisms, these drugs can be used in combination if needed.

In cats with functional gastroparesis or ileus, prokinetic treatment can be effective at improving motility. Metoclopramide has questionable central antiemetic effects in cats, but when administered as a constant rate infusion (CRI), metoclopramide increases gastric emptying and decreases gastric atony. 136 , 137 , 138 , 139 One study suggested a contraindication to the use of metoclopramide because of dopamine antagonism in cats with pancreatitis, but no clinical studies have confirmed such a contraindication. 127 Compounded cisapride is an effective PO prokinetic in cats and is the treatment of choice for delayed gastric emptying. 140 , 141 Erythromycin also has been shown to have a gastric prokinetic effect in cats. 136

9.4. Pain management

Pain is difficult to evaluate in cats. 142 The Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP)‐Botucatu multidimensional composite pain scale (MCPS) has been validated to assess postoperative pain in cats, 143 , 144 but validated pain scoring systems specifically for use in cats with pancreatitis are needed.

Although abdominal pain is less frequently reported in cats with acute pancreatitis as compared to humans or dogs, it probably is underestimated. 11 Opioids should be used as the primary analgesics for cats with acute pancreatitis. Buprenorphine is adequate for most cats, whereas methadone or fentanyl are good analgesic choices for cats with more severe pain. Experimental evidence suggests that maropitant citrate also may provide visceral analgesia. 134 Orally administered buprenorphine or maropitant can be used for analgesia in outpatients. Additionally, tramadol, gabapentin, or a combination of these 2 drugs can be considered as PO analgesic options. 145 , 146 , 147 , 148 , 149 , 150

9.5. Appetite stimulants

Most cats with acute pancreatitis are inappetent, which can contribute to malnutrition and impaired gastrointestinal barrier and immune function. Therefore, restoring food intake is an important factor in recovery. With mild to moderate pancreatitis, appetite stimulants often are an effective way to restore voluntary food intake. The most commonly prescribed appetite stimulants in cats are mirtazapine and capromorelin. Mirtazapine has been evaluated in inappetent cats, but can have adverse effects (eg, vocalization, agitation, vomiting, abnormal gait or ataxia, tremors, hypersalivation, tachypnea, tachycardia, lethargy) with more adverse effects noted at higher dosages. 151 An additional benefit of mirtazapine may be its antiemetic activity. 152 Mirtazapine transdermal ointment can be used in cats and generally is well‐tolerated and efficacious. 153 The safety and efficacy of capromorelin PO solution as an appetite stimulant have been reported in healthy cats. 154 Also, capromorelin recently has been approved for use in cats with chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the United States and can be considered as an appetite stimulant for cats with pancreatitis.

9.6. Nutrition

Nutritional support plays a central role in the management of acute pancreatitis in humans. Lack of enteral nutrition may lead to impaired gastrointestinal motility, intestinal villous atrophy, compromised intestinal blood flow, altered barrier function, and disruption of the normal intestinal microbiota. 155 , 156 Thus, in patients with severe acute pancreatitis, early enteral nutrition is viewed as an active therapeutic intervention that minimizes infected pancreatic necrosis and decreases the incidence of multiple organ failure, thus improving outcome. 157 , 158 In contrast, prolonged fasting or parenteral nutrition is no longer recommended unless enteral nutrition cannot be achieved. Early enteral nutrition was evaluated in a prospective randomized trial of humans with severe acute pancreatitis, and compared nasojejunal and nasogastric routes of feeding. It was determined that enteral nutrition was tolerated by both routes with no difference in outcome measures. 159 The International Consensus Guidelines Committee supports the use of nasogastric tube feeding in humans with acute pancreatitis within 24 hours after hospital admission. 160 In patients with severe acute pancreatitis, enteral nutrition may be provided by the gastric or jejunal route if PO feeding is not tolerated. 157 , 161

Limited information about the optimal nutritional management of acute pancreatitis is available for cats. 162 Evidence in studies of humans with pancreatitis and the results of experimental and clinical studies in animals support the use of enteral nutrition. 155 , 157 , 158 , 160 , 161 , 162 , 163 , 164 , 165 , 166 , 167 , 168 , 169 , 170 Because most cats with pancreatitis have been inappetent for a variable period of time, any withholding of food may be detrimental and is not recommended. Additionally, some cats, when inappetent or prevented from eating, will develop hepatic lipidosis, which will substantially increase mortality. 22 In cats with acute pancreatitis, PO feeding or enteral nutrition via tube feeding should be initiated early. Cats with mild to moderate acute pancreatitis often begin to eat with appropriate supportive and symptomatic care, whereas severe cases with complications often will require a feeding tube for appropriate alimentation. Additionally, a feeding tube can be used for hydration, administration of PO medications, and for gastric decompression, when indicated. The dietary needs for cats with acute pancreatitis have not been determined. Cats have high dietary protein requirements, making them susceptible to protein‐energy malnutrition and lean muscle mass loss during starvation. 171 , 172 Also, cats have a higher tolerance for dietary fat than do dogs. Additionally, decreased dietary arginine and methionine may limit the synthesis of hepatic lipoproteins and phospholipids, which may contribute to the development of hepatic lipidosis. 173 Highly digestible diets, often labeled as “gastrointestinal diets,” are recommended. Severely ill cats are prone to food aversion and it may be prudent to delay the use of the long‐term diet of choice until the cat has improved and is being fed at home.

Placement of an enteral feeding tube is indicated for cats that fail to respond to appetite stimulants within 48 hours or those that have a history of more prolonged anorexia before presentation. Nasoesophageal tubes (Figure 9A) or esophagostomy tubes (Figure 9B) are the most commonly placed tubes in cats with acute pancreatitis. Nasogastric tubes also are appropriate for short‐term use in hospitalized cats and allow for gastric suctioning when indicated. 162 However, nasogastric suctioning in humans with pancreatitis has been reported to lead to worsening gastric distension, gastro‐esophageal reflux, pain, and nausea and the efficacy of gastric suctioning has not yet been evaluated in cats with pancreatitis. 173 , 174 Gastrostomy tubes or jejunostomy tubes placed endoscopically or surgically are less commonly utilized. Nasoesophageal tubes are cost‐effective and easily placed under local anesthesia, avoiding the need for general anesthesia, and are a good choice for short‐term nutritional support of hospitalized or severely debilitated cats. With nasoesophageal tubes, feeding is limited to a liquid diet. Placement of esophagostomy tubes requires general anesthesia and more technical expertise, but is an excellent option when long‐term feeding is anticipated. Esophagostomy tubes allow for feeding of canned diets as a gruel.

FIGURE 9.

Nasoesophageal (A) and esophagostomy (B) tubes are the most practical tubes for alimentary support of cats with acute pancreatitis

For cats in which enteral feeding is not an option because of unmanageable vomiting, short‐term alimentation can be provided by partial or total parenteral nutrition. However, survival rates for cats receiving partial parenteral nutrition exclusively are lower than in cats receiving supplemental enteral nutrition. 175

9.7. Other treatments for cats with acute pancreatitis

In addition to supportive and symptomatic care, cats with severe necrotizing pancreatitis and complications or concurrent disorders require intensive care. Indicators of severe pancreatitis include marked dehydration (ie, 8%‐10%), persistent clinical signs despite medical management, hypotension, hypoglycemia, ionized hypocalcemia, or some combination of these. Severe complications may include systemic inflammatory response syndrome, cardiovascular shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, pulmonary thromboembolism, or multiorgan failure. 8 , 176

9.7.1. Advanced fluid therapy

Fluid, electrolyte, and acid‐base imbalances must be assessed and corrected as early as possible. In addition to correction of dehydration and maintenance fluid support with crystalloids, colloid therapy is beneficial when indicated to maintain and support colloid osmotic pressure and to prevent fluid imbalance and edema formation. Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) provides colloid support by supplementing albumin and is therapeutic for correction of coagulopathies secondary to disseminated intravascular coagulation. Studies in dogs suggest that when α2‐macroglobulin, a scavenger protein for activated proteases in serum, is depleted, death ensues rapidly. 126 Fresh whole blood and FFP contain α2‐macroglobulin. However, in clinical trials in humans 177 , 178 and in a retrospective study in dogs 179 with acute pancreatitis, a survival benefit of plasma administration was not demonstrated. Also, FFP is not recommended in current consensus statements on the treatment of acute pancreatitis in humans. 180 Although some questions remain about the potential beneficial effects of plasma, it is an expensive treatment that probably should be reserved for cats with coagulopathy.

Synthetic colloids (eg, hydroxyethyl starch, dextran) and hypertonic saline are cost‐effective alternatives to FFP. However, they provide only colloidal support, rather than supplementation of coagulation factors. None of these products have been evaluated in cats with pancreatitis, and they generally are reserved for animals with severe disease and hypotension, refractory to the administration of crystalloids. In cats receiving aggressive fluid support, it is important to avoid volume overload by monitoring respiratory rate and effort, performing pulmonary auscultation, and measuring central venous pressure.

Cats that are hypotensive despite crystalloid and colloid fluid therapy may require vasopressor support. Dopamine is a vasopressor that also may increase pancreatic blood flow and decrease microvascular permeability. However, its effect on pancreatic perfusion is transient, and dopamine may induce vomiting. In 1 study, progression of experimental pancreatitis in cats could be prevented by use of low‐dose dopamine therapy, but only when given within 12 hours of induction of pancreatitis. 127 Although this time limit hampers the clinical utility of dopamine in cats with spontaneous pancreatitis, dopamine may be beneficial in cats with pancreatitis that must undergo anesthesia. In persistently hypotensive cats, additional vasopressors to consider include norepinephrine, vasopressin, and epinephrine.

9.7.2. Antibiotics

In humans, antibiotics are not recommended in management of acute pancreatitis unless an infection is strongly suspected or has been confirmed. 180 In veterinary medicine, acute pancreatitis is considered to be a sterile process, based, in most instances, on inability to detect microbial growth using routine bacterial culture media. Antibiotics are not recommended for noncomplicated cases of pancreatitis. Reports of bacterial complications, such as pancreatic abscessation, are rare. 11 Broad‐spectrum antibiotics should be reserved for cats with acute pancreatitis in which pancreatic infection is suspected or confirmed (eg, pancreatic abscess, infected necrotic tissue), infection has ascended the common pancreatic or bile duct, or CBC findings are suggestive of sepsis. 11 , 122 , 181 Bacterial infections can occur with concurrent disorders, including cholangitis and aspiration pneumonia. Fluorescence in situ hybridization has identified bacteria in the pancreas of 35% of cats with moderate to severe pancreatitis. 182 The localization and type of intrapancreatic bacteria suggest translocation of enteric bacteria as a likely source. 182 However, to date no evidence supports the presence of bacterial DNA in pancreatic tissue as having clinical relevance, and thus the consensus panel does not suggest use of antibiotics in cats with pancreatitis unless strong clinical indications are present. Additionally, antibiotic usage may be associated with adverse effects and development of multidrug resistance.

9.7.3. Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are not used routinely for the treatment of acute pancreatitis in humans, dogs, or cats. Historically, there has been a reluctance to use corticosteroids for the treatment of pancreatitis, because of concerns that glucocorticoids may be a risk factor for the development of pancreatitis. However, a definitive relationship between glucocorticoids and acute pancreatitis has not been established in humans, and several studies indicate that they do not cause pancreatitis in dogs. 183 , 184 , 185 Corticosteroids have broad anti‐inflammatory effects, and research suggests they play a key role in enhancing apoptosis and increasing production of pancreatitis‐associated protein, which exerts a protective effect against pancreatic inflammation. 186 Glucocorticoids also may treat critical illness‐related corticosteroid insufficiency, which is reported in humans with acute pancreatitis. 187 Recent studies evaluating glucocorticoids for the treatment of acute pancreatitis in humans and dogs have shown improved outcomes. 188 , 189 However, no studies have evaluated the use of glucocorticoids in cats with acute pancreatitis, and thus there is insufficient evidence to recommend their routine use.

Similar to antibiotics, corticosteroids are beneficial in the treatment of certain concurrent disorders, including chronic inflammatory enteropathy and sterile cholangitis, and should be considered if these comorbidities are present. However, corticosteroids also are associated with important adverse effects for which cats with pancreatitis are already at risk (eg, diabetes mellitus).

9.7.4. Management of respiratory complications

Tachypnea and labored breathing are common complications of severe pancreatitis in cats, and may be caused by pleural effusion or pulmonary edema secondary to acute lung injury or both, acute respiratory distress syndrome, volume overload, congestive heart failure, aspiration pneumonia, pulmonary thromboembolism, pain, or some combination of these. Thoracic radiographs and Doppler echocardiography often permit rapid diagnosis to guide treatment. Thoracocentesis with pleural fluid analysis is indicated in cats with pleural effusion. Although the finding of simultaneous pleural and peritoneal effusions has been reported to indicate a poor to grave prognosis, such is not the consensus panel's experience in cats with pancreatitis. 190 Differentiation of pleural effusion secondary to congestive heart failure from that caused by pancreatitis is critically important for accurate modification of fluid therapy and initiation of diuretic treatment. In cats with aspiration pneumonia, antibiotics and oxygen treatment (if hypoxemia is present) are indicated.

9.7.5. Pancreatic surgery

In humans with acute pancreatitis, the most common indication for invasive procedures, infected necrosis, now usually is treated using minimally invasive approaches (eg, percutaneous, endoscopic, laparoscopic, or retroperitoneal), and traditional open resection of necrotic tissue usually is avoided because of risk of major complications or death. 161 Surgical management rarely is indicated in cats with acute pancreatitis, and clear indications to perform surgery have not been determined. In cats with severe acute pancreatitis and concomitant extrahepatic biliary obstruction or pancreatic abscess, surgical intervention may be beneficial. 191 However, most clinicians are conservative when considering pancreatic surgery, because most cats with severe pancreatitis are poor surgical candidates, and a benefit of surgery, including in cats with extrahepatic bile duct obstruction, has not been proven. 191

9.7.6. Other therapeutic strategies

Many other therapeutic strategies, including trypsin inhibitors (eg, aprotinin), platelet‐activating factor inhibitors, antacids (eg, proton pump inhibitors), antisecretory agents (eg, anticholinergics, calcitonin, glucagon, somatostatin), selenium and other antioxidants, and peritoneal lavage have been evaluated in experimental studies or in human patients with pancreatitis, but are not efficacious. None of these therapeutic strategies have been evaluated in cats with pancreatitis, and their routine use is not recommended. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) is recommended by some veterinary specialists for the management of pancreatitis, but no studies are available in veterinary patients and only a few experimental studies in rodents and a case report in a human patient are available. 192 , 193 , 194 , 195 Also, HBOT has not been included in current treatment guidelines for humans with pancreatitis. 196 Until clinical studies are performed in cats, routine use of this modality in cats cannot be recommended.

10. PROGNOSIS OF ACUTE PANCREATITIS

The mortality rate in cats with acute pancreatitis ranges from 9% to 41%, based on 4 studies. 60 , 63 , 102 , 162 Cats with mild to moderate acute pancreatitis generally have a good prognosis with appropriate management, whereas cats with severe acute pancreatitis, especially when complications or comorbidities are present, have a guarded to grave prognosis. Low plasma ionized calcium concentrations in cats with acute pancreatitis have been associated with poor outcome. 60 , 197 Hypoglycemia and azotemia also are poor prognostic indicators. 63 Mortality in humans with acute pancreatitis is reported to be 5%‐15%, but it has decreased over time and overall mortality of people with acute pancreatitis is approximately 2% with state‐of‐the‐art standard of care. 161 , 198

11. MANAGEMENT OF CHRONIC PANCREATITIS

Little research is available on the treatment of chronic pancreatitis in cats, and most recommendations are based on case reports or personal opinion rather than peer‐reviewed literature. Chronic pancreatitis in cats often occurs concurrently with other diseases, 23 and diagnosis and treatment of these conditions usually takes clinical priority. Targeted management of chronic pancreatitis often is not required. However, if chronic pancreatitis occurs as an isolated condition or appears to be a complicating factor that worsens the prognosis of comorbidities, particularly diabetes mellitus, then targeted management is indicated (see Supplementary Tables 1, 2, and 3 for a formulary).

11.1. Analgesia

Visceral pain is mediated by cytokines, substance P, neurokinin A, and calcitonin gene peptide, and thus traditional analgesics may not be effective in cats with chronic pancreatitis. 199 During overt bouts of disease, transmucosal buprenorphine can be administered. For long‐term treatment, gabapentin or tramadol may be better choices. 200 Maropitant, often selected for control of vomiting, also may provide visceral analgesia in cats. 201 Supplementation of pancreatic enzymes has been suggested in humans with pancreatitis to potentially decrease pain associated with feeding, but doing so is no longer recommended unless subclinical exocrine pancreatic insufficiency is present. 202 Development of feline‐specific monoclonal antibodies targeting pain mediators is a promising area of research that may transform pain management in cats with pancreatitis. 203

11.2. Nutritional support

Enteral nutritional support or dietary modification may be required for treatment of underlying or concurrent diseases, but rarely is required to manage chronic pancreatitis as a primary condition. Although scientific evidence that dietary fat is deleterious in cats with pancreatitis is not available and the majority of the consensus panel did not have any concerns about dietary fat content in cats with chronic pancreatitis, some panel members felt that avoiding high fat diets (eg, renal diets, low‐carbohydrate diets) is helpful in managing cats with this condition. In contrast, high fat diets may be helpful in providing adequate caloric intake with a small food volume. Overall, it is recommended that each cat's diet be assessed and altered if the diet is thought to have contributed to pancreatitis or a comorbidity.

11.3. Antiemetics and appetite stimulants

During bouts of vomiting or when inappetence is attributable to nausea, antiemetic treatment using maropitant or a 5HT3 antagonist should be considered. Appetite stimulants, such as mirtazapine, may be useful to help maintain voluntary food intake.

11.4. Antimicrobial treatment

Bacterial infection is not implicated in chronic pancreatitis and antimicrobials are not indicated unless required to treat concurrent conditions or infectious complications.

11.5. Other supportive treatment

Cobalamin supplementation is indicated when hypocobalaminemia is documented. It may be considered when anorexia or concurrent gastrointestinal disease is present.

11.6. Anti‐inflammatory and immunosuppressive therapy

Inflammation and subsequent fibrosis are important pathologic aspects of chronic pancreatitis in cats and may lead to subsequent deficiencies of the exocrine or endocrine functions of the pancreas. Prednisolone is a commonly used anti‐inflammatory and immunosuppressive drug that is potentially antifibrotic and has minimal adverse effects in cats when used at low doses. The adverse effect of most concern is enhanced peripheral insulin resistance, and the risk of diabetes mellitus.

Although some panel members felt that prednisolone should only be used in cats that are not hyperglycemic and only at anti‐inflammatory dosages (ie, 0.5‐1.0 mg/kg PO q24h on a tapering schedule), other panel members felt that immunosuppressive dosages of prednisolone (eg, 2.0 mg/kg q12h for 5 days and then 1.0 mg/kg q12h for 6 weeks with a decreasing dosing schedule after that time) with close monitoring (ie, clinical re‐evaluation and measurement of fPLI after 2‐3 weeks) could have a beneficial effect. If hyperglycemia develops, or is pre‐existing, some panel members recommend the use of cyclosporine (5 mg/kg q24h for 6 weeks) with close monitoring (ie, clinical re‐evaluation and measurement fPLI after 2‐3 weeks). 204 , 205 In cats treated with either prednisolone or cyclosporine in which clinical signs have not improved and pancreatic lipase has not decreased, discontinuation of treatment should be considered. In cats that show a clinical response, continuation of treatment is indicated. Unmasking latent toxoplasmosis may be a concern with long‐term use of high‐dose cyclosporine. 206 Toxoplasmosis may be of a greater concern in geographic locations where cats frequently hunt in the wild or consume raw meat and has been reported in renal transplant cats and a cat treated for atopy. 207 , 208 , 209

Other immunosuppressive medications, such as chlorambucil, also may be beneficial, but have not been studied in cats with chronic pancreatitis.

11.7. Monitoring

If serum fPLI is increased at the time of diagnosis, it can be used to monitor response, along with clinical variables. However, the sensitivity of serum fPLI is lower in cats with mild disease than in those with severe disease and, like any other diagnostic test, this laboratory test should not be used in isolation to assess clinical remission.

12. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, although both acute and, especially, chronic pancreatitis are considered to occur commonly in cats, diagnosis remains challenging. Most of what is known regarding the etiology and pathogenesis of pancreatitis in cats is extrapolated from spontaneous disease in other species or from experimental animal models, including cats. Accurate diagnosis of pancreatitis in cats requires the integration of history and clinical findings, diagnostic imaging, laboratory data, and potentially cytology or histopathology. Depending on the clinical findings in an individual cat, additional diagnostic tests to rule out other differential diagnoses may be needed.

Management of acute pancreatitis involves treatment of potential causes, fluid therapy, analgesics, antiemetics, nutritional support, and other symptomatic and supportive care as needed. Management of chronic pancreatitis involves the treatment of potential causes, diagnosis and management of concurrent conditions, analgesics, antiemetics, and potentially anti‐inflammatory and immunosuppressive treatment.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DECLARATION

Dr. J. Steiner serves as the director of the Gastrointestinal Laboratory at Texas A&M University, which offers measurement of fPLI concentration on a fee‐for‐service basis. Dr. Steiner also serves as a paid consultant and speaker for Idexx Laboratories, Westbrook, ME, the manufacturer of the Spec fPL and SNAP fPL assays and for ISK, Osaka, Japan, the manufacturer of fuzapladib. None of these organizations influenced the outcome of this consensus statement. None of the other authors declare any conflict of interest.

OFF‐LABEL ANTIMICROBIAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no‐off label use of antimicrobials.

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC) OR OTHER APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no IACUC or other approval was needed.

HUMAN ETHICS APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare human ethics approval was not needed for this study.

Supporting information

Data S1 Supporting information tables.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

No funding was received for this study. We acknowledge the help of Mr. Brian Collins, Outreach Librarian at the School of Veterinary Medicine, Louisiana State University for his help with literature research and building the reference database for the consensus statement using ACVIM guidelines. We also thank Kate Patterson at MediPics and Prose in Fairlight, New South Wales, Australia for creating Figures 1, 2, 3.

Forman MA, Steiner JM, Armstrong PJ, et al. ACVIM consensus statement on pancreatitis in cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2021;35:703–723. 10.1111/jvim.16053

Consensus Statements of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) provide the veterinary community with up‐to‐date information on the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of clinically important animal diseases. The ACVIM Board of Regents oversees selection of relevant topics, identification of panel members with the expertise to draft the statements, and other aspects of assuring the integrity of the process. The statements are derived from evidence‐based medicine whenever possible and the panel offers interpretive comments when such evidence is inadequate or contradictory. A draft is prepared by the panel, followed by solicitation of input by the ACVIM membership which may be incorporated into the statement. It is then submitted to the Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, where it is edited prior to publication. The authors are solely responsible for the content of the statements.

Marnin A. Forman and Joerg M. Steiner are co‐chairs, listed in alphabetical order.

P. Jane Armstrong, Melinda S. Camus, Lorrie Gaschen, Steve L. Hill, Caroline S. Mansfield, and Katja Steiger are panel members, listed in alphabetical order.

REFERENCES

- 1. De Cock HEV, Forman MA, Farver TB, et al. Prevalence and histopathologic characteristics of pancreatitis in cats. Vet Pathol. 2007;44:39‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2012;62:102‐111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Whitcomb DC, Frulloni L, Garg P, et al. Chronic pancreatitis: an international draft consensus proposal for a new mechanistic definition. Pancreatology. 2016;16:218‐224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Steer ML, Waxman I, Freedman S. Chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1482‐1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Watson P. Pancreatitis in dogs and cats: definitions and pathophysiology. J Small Anim Pract. 2015;56:3‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xenoulis PG, Steiner JM. Current concepts in feline pancreatitis. Top Companion Anim Med. 2008;23:185‐192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Steiner JM. Exocrine pancreas. In: Steiner JM, ed. Small Animal Gastroenterology. 1st ed. Hannover: Schlütersche‐Verlagsgesellschaft mbH; 2008:283‐306. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Armstrong PJ, Williams DA. Pancreatitis in cats. Top Companion Anim Med. 2012;27:140‐147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bayliss DB, Steiner JM, Sucholdolski JS, et al. Serum feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity concentration and seroprevalences of antibodies against toxoplasma gondii and Bartonella species in client‐owned cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2009;11:663‐667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vyhnal K, Barr S, Hornbuckle W, et al. Eurytrema procyonis and pancreatitis in a cat. J Feline Med Surg. 2008;10:384‐387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Armstrong PJ, Crain S. Feline acute pancreatitis: current concepts in diagnosis & therapy. Todays Vet Pract. 2015;5:22‐28. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pratschke KM, Ryan J, McAlinden A, et al. Pancreatic surgical biopsy in 24 dogs and 19 cats: postoperative complications and clinical relevance of histological findings. J Small Anim Pract. 2015;56:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Torner K, Aupperle‐Lellbach H, Staudacher A, et al. Primary solid and cystic tumours of the exocrine pancreas in cats. J Comp Pathol. 2019;169:5‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zimmermann E, Hittmair KM, Suchodolski JS, Steiner JM, Tichy A, Dupré G. Serum feline‐specific pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity concentrations and abdominal ultrasonographic findings in cats with trauma resulting from high‐rise syndrome. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013;242:1238‐1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hill RC, Winkle TJ. Acute necrotizing pancreatitis and acute suppurative pancreatitis in the cat. J Vet Intern Med. 1993;7:25‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Badalov N, Baradarian R, Iswara K, Li J, Steinberg W, Tenner S. Drug‐induced acute pancreatitis: an evidence‐based review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:648‐661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]