Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor T (CART) cells are a promising immunotherapy that has induced dramatic anti-tumor responses in certain B cell malignancies. However, CART cell expansion and trafficking are often insufficient to yield long-term remissions, and serious toxicities can arise after CART cell administration. Visualizing CART cell expansion and trafficking in patients can detect an inadequate CART cell response or serve as an early warning for toxicity development, allowing CART cell treatment to be tailored accordingly to maximize therapeutic benefits. To this end, various imaging platforms are being developed to track CART cells in vivo, including nonspecific strategies to image activated T cells and reporter systems to specifically detect engineered T cells. Many of these platforms are clinically applicable and hold promise to provide valuable information and guide improved CART cell treatment.

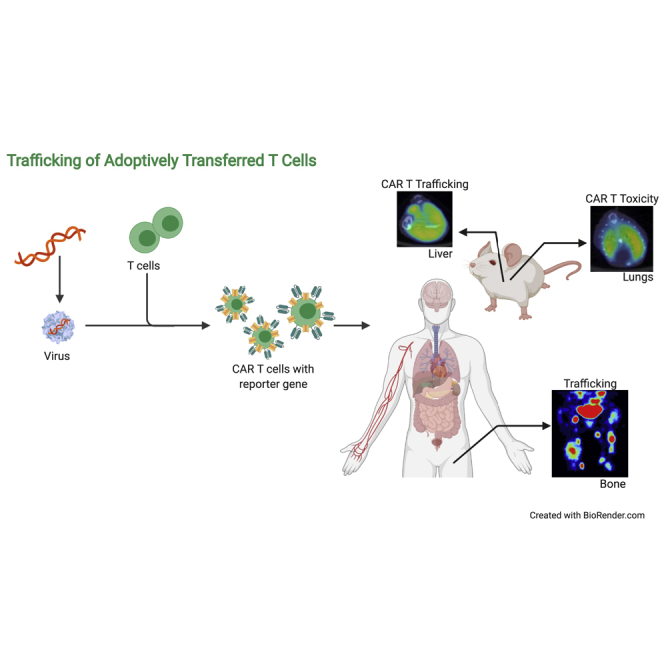

Graphical abstract

Imaging and tracking adoptively transferred T cells would allow the in vivo characterization of T cell expansion and trafficking to tumor sites. Sakemura and colleagues review the current state-of-the-art modalities for in vivo T cell imaging and their role in the early prediction of outcomes or detection of toxicities.

Introduction

Adoptive transfer of autologous chimeric antigen receptor T (CART) cell therapy has recently emerged as a potent and potentially curative therapy in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL),1, 2, 3, 4 acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL),5, 6, 7, 8 chronic lymphocytic leukemia,9, 10, 11, 12 and multiple myeloma (MM).13, 14, 15 Thus far, two CD19-redirected CART (CART19) cell products (tisagenlecleucel in ALL and axicabtagene ciloleucel in DLBCL) were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017, and one CART19 cell product was approved for the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma in 2020 (brexucabtagene autoleucel).16 Several other CART cell products are expected to receive FDA approval in the next 3–5 years.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15

Despite the success of CART cell therapy, limitations include (1) lower rates of durable response related to inadequate CART cell expansion and trafficking to tumor sites, (2) lack of objective responses in solid tumors, and (3) the development of life-threatening complications such as cytokine release syndrome (CRS),17, 18, 19 which is associated with massive T cell proliferation after CART cell infusion.20, 21, 22 The ability to efficiently and robustly image and track CART cells in patients would allow the in vivo characterization of T cell expansion and trafficking to tumor sites as well as the development and rapid incorporation of strategies to potentially overcome these limitations. Effective imaging and the subsequent adjustment of treatment strategies would help to expand the application of CART cell therapy in solid tumors,23, 24, 25, 26, 27 as it has become increasingly apparent that CART cell trafficking and infiltration into tumor sites are largely inhibited by the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment.28 Thus, the development of a dynamic imaging platform is crucial to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of novel CART cell therapies.

In this report, we review current and emerging strategies in the field of CART cell imaging. We categorize imaging platforms into nonspecific imaging platforms for activated T cells and specific platforms for engineered CART cells. Non-specific platforms represent an indirect measurement of adoptive T cell or CART cell expansion and trafficking, while the incorporation of reporter genes is a direct measurement of the functions of engineered T cell. We then examine the pros and cons of these imaging technologies (summarized in Table 1) and discuss strategies to incorporate CART cell imaging in the clinic. Table 2 lists ongoing clinical trials utilizing T cells in vivo.

Table 1.

Pros and cons of imaging technologies

| Target | Tracer | Application | Pros | Cons | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T cell-specific marker | murine TCR |

89Zr-DFO-aTCRmu-F(ab′)2, 64Cu-cOVA-TCR |

TILs | • fast and robust accumulation of the probe in the cells due to high rate of internalization of the TCR • reliable correlation between cell number and the signal |

• tracer may induce T cell stimulation • less signal may be seen after cell division |

| murine CD8 | 89Zr-malDFO-169 cDb | TILs | • decreased aggregation, more stability in blood, and more successful lymph node and spleen targeting | • antibody clearance is faster than full antibodies | |

| human CD8 | 89Zr-DFO-IAB22M2C | ||||

| murine CD3 | 89Zr-DFO-CD3 | TILs | • provides visualization of all T cell populations • eliminates need for specific pathway, as CD3 is a pan-T cell marker • correlated with immune response |

• requires extensive testing and optimization before being translated into the clinic | |

| T cell activation marker | CD25 | 99mTc-HYNIC-IL-2 | TILs | • CD25 is highly expressed in activated T cells | • patients may experience adverse events because radiolabeled IL-2 is biologically active |

| OX40 | 64Cu-DOTA-AbOX40 | TILs | • not only monitors T cells but also shows responder T cells • OX40 represents an early activation marker and therefore provides quick assessment |

• OX40 expression on T cells is diverse, and thus deviation between tracer uptake and cell number may be seen | |

| Metabolic pathway | deoxycytidine kinase (dCK) |

18F-F-AraC, 18F-CFA |

TILs | • activated T cells increase the entry of the substrate | • tumors also uptake the tracer |

| deoxyguanosine kinase (dGK) | 18F-F-AraG | TILs | • activated T cells increase the entry of the substrate | • high tracer uptake in the background | |

| T cell effector molecules | human PD-1 |

64Cu-DOTA-anti-PD-1, 89Zr-nivolumab, 89Zr-penbrolizumab |

TILs | • correlation between biodistribution of tracer and IHC | • requires several days for the tracer to accumulate to the target |

| human CTLA-4 |

64Cu-DOTA-anti-CTLA-4, 89Zr-ipilimumab |

TILs | • correlation between biodistribution of tracer and IHC | • clinical trial is ongoing | |

| murine granzyme B | 68Ga-NOTA-GZP | TILs | • correlation between biodistribution of tracer and treatment response | • low dependence on tissue migration • no clinical trials to date |

|

| murine IFN-γ | 89Zr-anti-IFN-γ | TILs | • correlation between biodistribution of tracer and treatment response | • low dependence on tissue migration • no clinical trials to date |

|

| Reporter gene | HSV-tk | 18F-FHBG | oncolytic virus, CART cells | • early clinical trial showed safety and feasibility of imaging CART cells with HSV-tk | • tracers do not penetrate BBB • immunogenicity |

| NIS |

124I, 18F-TFB, 18F-SO3F |

oncolytic virus, CART cells, regulatory T cells, dendritic cells | • no immune response • high sensitivity • no toxicity to transduced cells |

• tracers do not penetrate BBB • endogenous expression is seen in thyroid, stomach, and salivary gland |

|

| SSTr2 |

68Ga-DOTANOC, 68Ga-DOTATOC, 68Ga-DOTATATE |

CART cells, TILs | • no immune response • high sensitivity • no toxicity to transduced cells |

• endogenous expression in several organs and cancer types • tracers may activate T cells |

|

| D2R |

11C-raclopride, 18F-FESP |

– | • tracer penetrates BBB | • has not been reported for tracking T cells in vivo | |

| hdCK |

124I-FIAU, 18F-FEAU |

CART cells, TILs | • non-immunogenic | • endogenous expression in several organs and cancer types • tracers do not penetrate BBB • accumulates less pyrimidine-based radiotracer compared to HSV-tk |

|

| eDHFR | 18F-TMP | CART cells | • high sensitivity • tracer penetrates BBB |

• immunogenicity | |

| PSMA |

18F-DCFPyL, 18F-DCFBC, 68Ga-PSMA-11 |

CART cells | • new tracers that are cleared rapidly from kidney are under development • signal amplification due to receptor-tracer complex internalization |

• kidney and patients with prostate cancer have background issue • possible issues with overexpression of PSMA |

TCR, T cell receptor; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4; IFN, interferon; HSV-tk, herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase; NIS, sodium/iodide symporter; SSTr2, somatostatin receptor 2; D2R, dopamine 2 receptor; hdCK, human deoxycytidine kinase; eDHFR, Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase; PSMA, prostate-specific membrane antigen; DFO, desferrioxamine; muTCR, murine T cell receptor; F(Ab), antigen-binding fragment; cOVA, chicken ovalbumin; mal, malemide; cDb, cys-diabody; HYNIC, 6,-hydrazinonicotinamide; AraC, arabinofuranosyl cytidine; CFA, clofarabine; AraG, arabinofuranosyl guanine; GZP, granzyme B specific PET imaging agent; FHBG, fluoro-3-hydroxymethyl-butyl guanine; TFB, tetrafluoroborate; FESP, fluoroethyl spiperone; FIAU, 2′-fluoro-2′-deoxy-1β-d-arabinofuranosyl-5-iodouracil; FEAU, fluoro-5-ethyl-1-β-D-arabinofuranosyluracil; TMP, trimethoprim; 18F-DCFPyL, 2-(3-{1-carboxy-5-[(6-18F-fluoro-pyridine-3-carbonyl)-amino]-pentyl}-ureido)-pentanedioic acid; 18F-DCFBC, N-[N-[(S)-1,3-dicarboxypropyl]carbamoyl]-4-18F-fluorobenzyl-L-cysteine; TILs, tumor infiltrating lymphocytes; CART, chimeric antigen receptor T cell; IHC, immunohistochemistry; BBB, blood–brain barrier

Table 2.

Ongoing clinical trials for imaging T cells

| Name/target | Clinical trial identifier (ClinicalTrials.gov) | Tracer | Reference (PMID) | Images seen in clinical trials (PMID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-2 | NCT02922283 | 18F-FB-IL-2 | 28197364 | – |

| CD8 | NCT03802123 | 89Zr-DFO-IAB22M2C | 31586002 | 31586002 |

| CTLA-4 | NCT03313323 | 89Zr-ipilimumab, [64Cu]-DOTA | 30755811, 25365349 | – |

| Activated T cell DNA synthesis | NCT03409419 | 18F-CFA | 27035974, 27811125 | 27811125 |

| Activated T cell DNA synthesis | NCT03129061, NCT03142204, NCT03311672, NCT03142204 | 18F-F-AraG | 28572504, 29596062, 18542051 | 28572504, |

| T cell membrane | NCT03853187 | 111In-oxine | 17640914 | – |

| HSV-tk | NCT00730613, NCT01082926 | 18F-FHBG | 28100832 | 28100832 |

Strategies for nonspecific imaging of activated T cells

Several cellular imaging platforms have been developed using antibodies or molecules that recognize activated T cell proteins or pathways. These include platforms that target T cell activation markers, metabolomic pathways, nonspecific T cell antigens, or T cell immune checkpoints.

In vivo T cell imaging using surface activation markers

Activated T cells upregulate unique molecules that have been utilized for in vivo imaging and tracing, such as interleukin (IL)-2 receptor alpha chain (CD25), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily member 4 (TNFRSF4/OX40/CD134),29 immune checkpoints [programmed cell death protein (PD)-1 or cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen (CTLA)-4],30 or effector cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-γ, granzyme B, or TNF-α. Quantitative imaging of in vivo T cell biodistribution by tracking activation may have a direct impact on predicting the outcomes of the therapy or selection of patients. Herein, we describe T cell imaging targets related to T cell effector function.

CD25

Markovic et al.31 reported in vivo T cell imaging with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) using 99mTc-hydrazinonicotinamide (HYNIC)-IL-2 in patients with metastatic melanoma who received either ipilimumab or pembrolizumab. Although tracer uptake was successfully demonstrated in activated T cells after adoptive T cell immunotherapy, SPECT imaging and histological analysis did not show correlation between the uptake level of 99mTc-HYNIC-IL-2 and the numbers of infiltrating T cell lymphocytes.

OX40

OX40 is also an attractive T cell activation marker that can be targeted for T cell imaging. 64Cu-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA)-AbOX40 has been utilized as a positron emission tomography (PET) tracer and was able to recognize OX40 on activated T cells after in situ vaccination with CpG oligodeoxynucleotide in an A20 lymphoma mouse model. More importantly, 64Cu-DOTA-AbOX40 PET imaging correlated with the tumor response to the immunotherapy.32

PD-1

64Cu-labeled anti-mouse PD-1 antibody was developed to detect PD-1+ murine tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs).33 In this preclinical work, researchers showed that mice receiving anti-PD-1 tracer revealed a significant uptake in lymphoid organs and tumors. Niemeijer et al.34 conducted a clinical trial of whole-body PET imaging with 89Zr-nivolumab in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. 89Zr-nivolumab uptake correlated with PD-1+ TILs. Moreover, there was a correlation between tumor tracer uptake and response to nivolumab treatment.

CTLA-4

Another desirable effector molecule target for T cell imaging is CTLA-4. 64Cu-conjugated anti-CTLA-4 antibody was established to image CTLA-4 in a CT26 mouse tumor model35 and successfully visualized CTLA-4+ TILs. A phase II clinical study with 89Zr-labeled ipilimumab is currently running in patients with metastatic melanoma (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03313323) to investigate the correlation between tracer uptake in tumor sites and response to therapy.

IFN-γ

89Zr-conjugated anti-IFN-γ tracer was tested in a mouse breast cancer model. In this study, mice were treated with a HER2 cancer vaccine. 89Zr-PET revealed that vaccinated mice exhibited significant uptake in the tumor site, which indicated a response to the therapy. Researchers concluded that in situ immune evaluation with PET may demonstrate an enhanced predictor of response.36

Granzyme B

Granzyme B is a serine protease secreted by natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic T cells and indicates an anti-tumor T cell response. Therefore, similar to IFN-γ, granzyme B can also be an attractive target for T cell imaging during immunotherapy. Using a CT26 murine colon cancer model, researchers were able to show the correlation between 68Ga-labeled granzyme B uptake and tumoral granzyme B expression. Moreover, 68Ga-PET could predict the outcome after treatment with checkpoint inhibitors.37

There are a few advantages to targeting early T cell activation markers such as CD25 and OX40 in cellular imaging: these platforms can be indicators of successful immune cell priming, and therefore these imaging strategies have the potential to predict response to immunotherapy. However, the major disadvantage includes lack of specificity to engineered T cells. Additionally, the degrees of expression of T cell activation markers vary, making it difficult to correlate T cell quantification using PET imaging with the actual number of T cells in the tumor sites. Furthermore, T cell activation markers do not correlate with T cell cytotoxicity.

In vivo T cell imaging using metabolic pathways

Imaging of activated cells based on metabolic activity with the radioactive 18F-labeled glucose analog 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) has been used for staging malignancies in the field of oncology in the last few decades.38, 39, 40 Targeting metabolic pathways for imaging T cells in vivo has the potential benefit that only activated cells readily uptake the substrate. Herein, we review attractive metabolic pathways that have been used as targets for T cell imaging in vivo.

Deoxycytidine kinase (dCK)

dCK is an essential enzyme for the activation of nucleoside-based agents, including cytarabine gemcitabine, or 9-β-D-arabinofuranosylguanine (Ara-G). While most tissues rely on de novo DNA synthesis pathways, lymphoid immune cells or cancer cells depend on the salvage pathways. Thus, lymphocytes express high levels of dCK, and deoxyribonucleoside substrate cycles increase during rapid clonal expansion.41 In preclinical studies, targeting dCK with 1-2′-deoxy-2′-18F-fluoroarabinofuranosyl cytosine (18F-F-AraC) enabled tracking of activated T cells in a murine sarcoma model.42 18F-labeled clofarabine (18F-CFA) is another nucleotide probe metabolized through dCK and allowed visualization of leukemic cells with PET in a preclinical study.43 This probe is being assessed in a clinical trial to image immune activation during checkpoint blockade in patients with advanced melanoma (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03409419).

Deoxyguanosine kinase (dGK)

dGK is another enzyme responsible for phosphorylation of purine deoxynucleotides. In preclinical studies, dGK was targeted to visualize donor-derived T cells in an acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) mouse model. 2′-Deoxy-2′-18F-fluoro-9-β-D-arabinofuranosylguanine (18F-F-AraG) was used as a tracer in this preclinical study and successfully detected massive T cell activation in lymph nodes, prior to the development of GVHD.44 18F-F-AraG is currently being investigated in clinical trials of cancer immunotherapies (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03142204 and NCT03007719).

Metabolic pathways are attractive targets for T cell imaging in vivo. However, most tumor cells are metabolically plastic and use a variety of metabolic pathways due to increased energy demands; therefore, signals at the tumor sites can be difficult to differentiate between tumor cells and T cells.

In vivo T cell imaging using T cell-specific surface markers

Antibody tracers to T cell receptors (TCRs), CD3, CD4, and CD8 have been tested in preclinical studies to monitor the localization or density of T cells.

TCR

Several efforts have been developed to target TCRs for T cell imaging. Griessinger et al.45 demonstrated that the direct intracellular labeling of T cells with 64Cu monoclonal antibody directed against the TCR enabled T cell imaging in vivo. This approach did not impair T cell viability or antigen recognition through the TCR. Another group used 89Zr-labeled anti-mouse TCR F(ab′)2 fragment to track T cells in vivo and showed that 89Zr uptake in PET correlated with ex vivo T cell quantification with flow cytometry.46

CD3

Targeting the T cell surface glycoprotein CD3 is also an alternative to image T cells in vivo. In a study by Larimer et al.,47 colon cancer xenograft mice treated with anti-CTLA-4 were subsequently injected with 89Zr-labeled anti-CD3 antibody and imaged with PET. Researchers were able to quantify TILs, and the level of 89Zr uptake correlated with the tumor regression.

CD4 or CD8

Imaging the total T cell population via TCR or CD3 targeting is a broad and nonspecific strategy for T cell detection. Therefore, targeting major subsets of T cells, such as CD8 or CD4, represents the next logical strategy.

111In-labeled anti-CD4 antibody was used to image CD4 T cells in a murine model of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis with SPECT. This study showed clear correlation between bowel uptake of the tracer and the pathology findings.48

Seo et al.49 used 64Cu-anti-CD8 antibody to assess T cell tracking in mice and were able to visualize and quantify TILs after anti-PD-1 therapy using PET. Another group also successfully developed 89Zr-desferrioxamine-labeled anti-CD8 cys-diabody (89Zr-malDFO-169 cDb) for noninvasive PET tracking of endogenous CD8 T cells.50 In this work, researchers visualized CD8 T cells after adoptive transfer of antigen-specific T cells, antagonist antibody, and checkpoint blockade. A phase II clinical study is currently ongoing in patients with advanced solid tumors treated with immunotherapy (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03802123).

The main challenge for quantification of T cell subpopulations through cell surface markers is that the expression can vary during the course of treatment. Additionally, the degree of surface marker expression does not reflect T cell functionality, including cytotoxicity and cytokine production.

Specific platforms for CART cell imaging using reporter genes

Reporter genes are broadly applied in the field of adoptive immunotherapy owing to their high sensitivity and lack of toxicity. In recent years, several groups have developed and investigated strategies to monitor in vivo CART cell trafficking using radionuclide-based imaging. Although in vivo imaging technologies including fluorescence and bioluminescence provide inexpensive and convenient strategies to track cells in the preclinical field, clinical application has not been successful due to poor resolution and immunogenicity.51 Alternatively, radionuclide imaging using PET or SPECT provides high resolution and high sensitivity.52, 53, 54, 55 In this section, we describe the most prominent reporter genes that can be translated into the clinic for the purpose of imaging CART cells after infusion.

Herpes simplex virus 1 thymidine kinase (HSV-tk)

The HSV-tk-based reporter system, first described by Yaghoubi et al.56 in 2009, has been widely used in the field of cell imaging.57, 58, 59 Recently, a phase I clinical trial utilized HSV-tk for the successful imaging of IL-13Rα2-targeting CART cells in seven patients with glioma.56,60 The main limitations of HSV-tk as an imaging reporter system are immunogenicity and background signals in brain cells or naive T cells, which make the platform less specific for CART cell imaging.

Sodium iodide symporter (NIS)

The NIS is an intrinsic membrane protein associated with iodide uptake into thyroid follicular cells and has an essential role in the biosynthesis of thyroid hormones.61 We and others have reported NIS-based in vivo imaging of CART cells.62,63 The NIS reporter has long been investigated in clinical trials of viral and cell therapy as a sensitive reporter system.64, 65, 66, 67, 68 Incorporation of NIS into CART cells did not impair CART cell functions and was able to image as few as 40,000 injected CART cells in vivo with low background signal.62,63 NIS imaging with PET not only detected trafficking of CART cells but also identified massive CART cell expansion, correlating with the development of CRS in preclinical models62 (Figure 1). Measles virus engineered to express NIS was tested in early phase I and II clinical trials. A preliminary report presented encouraging data on two heavily pre-treated patients with refractory MM (Figure 2).69 The main disadvantages of the NIS reporter include baseline background in the thyroid and stomach and the inability of the tracer to penetrate the blood-brain barrier (BBB).

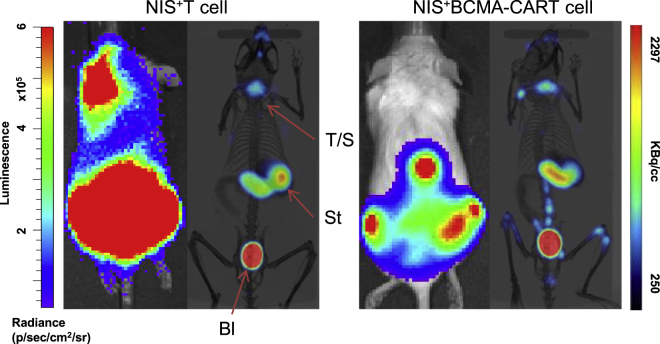

Figure 1.

18F-TFB-PET imaging of NIS+ CART cells is an efficient platform to detect CART cell trafficking

The OPM-2 xenograft model was created through intravenous injection of 1 × 106 B cell maturation antigen (BCMA)+ luciferase+ OPM-2 cells into immunocompromised nonobese diabetic (NOD)/severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)/IL-2rγnull (NSG) mice. Three weeks later, bioluminescence imaging (BLI) was performed, and mice were randomized to receive 5 × 106 NIS+ T cells or NIS+ BCMA-CART cells. BLI and 18F-TFB-PET were performed 7 days after T cell infusion. 18F-TFB-PET imaging of NIS+ BCMA-CART cells confirms their trafficking to tumor sites in a systemic multiple myeloma (MM) xenograft model. BLI of MM xenografts, 7 days after treatment with BCMA-CART cells, demonstrates engraftment of disease in the bones, as predicted. Concurrent 18F-TFB-PET imaging of the mice shows trafficking of NIS+ BCMA-CART cells to the corresponding tumor sites. Physiological uptake of TFB by endogenous NIS was seen in the thyroid/salivary glands (T/S), stomach (St), and bladder (Bl).

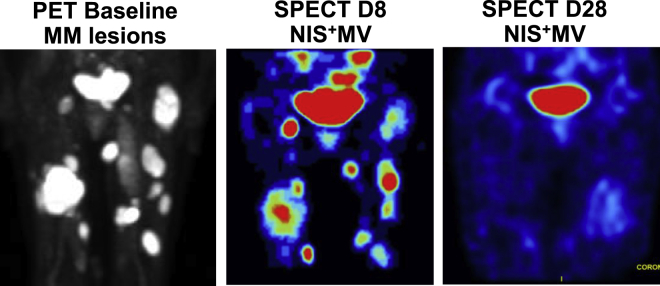

Figure 2.

Representative images from a patient with MM treated with NIS+ measles virus (MV)

Left panel: PET scan image at baseline, showing MM lesions involving the lower extremities. Middle panel: SPECT image on day 8 after NIS+ MV treatment, showing activity corresponding to the MM bone lesions. Right panel: SPECT image on day 28 after NIS+ MV treatment, showing resolution of MV activity and residual physiological uptake in the bladder.

Somatostatin receptor type 2 (SSTr2)

Somatostatin receptors are widely expressed on tumor cells and have limited expression on normal tissue, such as the pancreas, cerebrum, and kidneys, and low expression in the jejunum, colon, and liver.70,71 Thus, SSTr2 represents an attractive platform to incorporate as a reporter for CART cell imaging. Vedvyas et al.72 recently reported in vivo CART cell imaging using SSTr2. They were able to demonstrate anti–intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) CART cell expansion using 18F-NOTA-octreotide PET in tumor-bearing mice with 68Ga-DOTATOC. The limitations of SSTr2 include the inability of tracers to penetrate the BBB,73 and potential negative impacts on T cell proliferation or signaling after SSTr2 transduction.74

Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)

PSMA PET using 68Ga-PSMA-11 or 2-(3-{1-carboxy-5-[(6-18F-fluoro-pyridine-3-carbonyl)-amino]-pentyl}-ureido)-pentanedioic acid (18F-DCFPyL) has been utilized to detect prostate cancer in the clinic.75, 76, 77 68Ga-PSMA-11 has been approved by the FDA as a diagnostic tool in prostate cancer,78 making it an accessible platform for imaging adoptively transferred T cells in the clinic. Using a B cell ALL (B-ALL) xenograft model, Minn et al.79 successfully imaged CD19-directed CART cells with 18F-DCFPyL-PET in vivo and could detect as low as 2,000 CART cells. Similar to NIS- or SSTr2-based imaging platforms, 18F-DCFPyL-PET revealed trafficking of infused PSMA+ CART cells and infiltration into tumors sites. In addition, PSMA-targeted radiotherapeutics including 177Lu-PSMA-61780 can be used as a safety switch to kill CART cells. The limitations of PSMA as a reporter gene are that the tracer does not cross the BBB, and high background can be seen in the excretion site.81

Human deoxycytidine kinase (hdCK)

An hdCK mutant reporter was engineered to express on Pz1-directed CART cells with an 18F-2′-fluoro-2′-deoxyarabinofuranosyl-5-ethyluracil (18F-FEAU) tracer. 18F-FEAU-PET was able to track tumor-infiltrating CART cells in a prostate cancer xenograft model.82 Another group also used hdCK as a platform to image T cells in vivo. In this study, an engineered TCR was transduced to express hdCK, and 2′-deoxy-2′-18F-fluoro-5-methyl-1-β-L-arabinofuranosyluracil (18F-L-FMAU)-PET was used to successfully monitor tumor infiltration of TCR-T cells in a melanoma xenograft mouse model.83

Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase (eDHFR) enzyme

An alternative approach for an in vivo CART cell imaging platform is the eDHFR enzyme. Sellmyer et al.84 co-transduced T cells with eDHFR and anti-GD2 CAR and imaged the GD2+ mice with PET using the small-molecule antibiotic 18F-trimethoprim (TMP) as a radiotracer. This platform was noted to be highly sensitive, and imaging was able to detect as low as 11,000 cells/mm3. However, one significant disadvantage is that high immunogenicity could result in rejection of eDHFR+ T cells, making such an approach in human studies non-feasible.

Conclusions and future perspectives

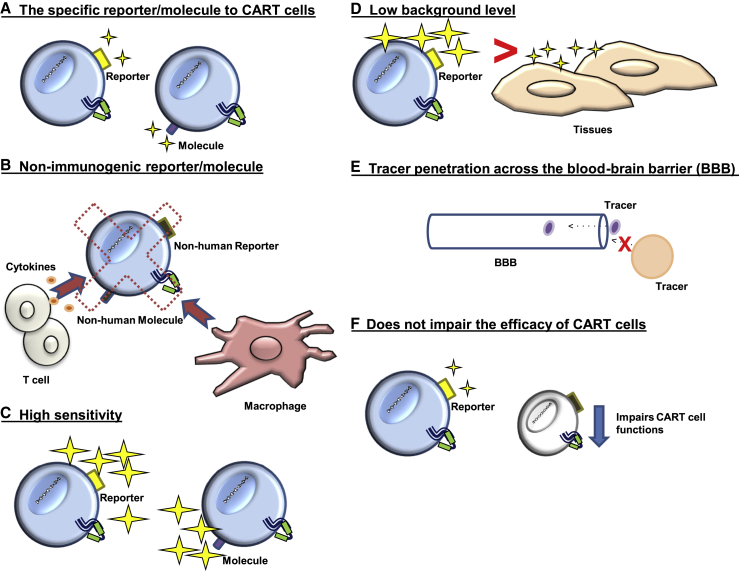

As CART cell therapy continues to become a mainstay pillar in the treatment of cancer, there will be a greater need for a platform to allow noninvasive imaging and monitoring of CART cell trafficking and in vivo expansion. Imaging the dynamics and function of adoptive T cells is valuable to demonstrate the interaction between T cells and tumor cells, as well as normal tissues. Such a platform would enable (1) the assessment of CART cell trafficking, (2) real-time monitoring of expansion and potential prediction of CART cell toxicity, and (3) the rapid incorporation of strategies to enhance CART cell trafficking or minimize toxicity in phase I clinical trials. An ideal imaging platform for CART cells should meet the following criteria (Figure 3): (A) the reporter/molecule should be specific to CART cells; (B) the reporter/molecule should be non-immunogenic; (C) the imaging platform should have high sensitivity to detect low numbers of CART cells; (D) the reporter/molecule should have low background expression on normal tissue; (E) the tracer should ideally penetrate the BBB (however, it is unclear how essential this criterion is, since the BBB is usually disrupted when cancer is metastasized to the brain; this will be answered as more clinical trials utilize reporter genes); and (F) incorporation of the reporter molecule in CART cells and subsequent imaging should not impair CART cell functions.

Figure 3.

An ideal imaging platform for CART cells

(A) The reporter/molecule should be specific to CART cells. (B) The reporter/molecule is non-immunogenic to avoid rejection. (C) The imaging platform should have high sensitivity to detect low numbers of CART cells. (D) The reporter/molecule should have low background expression on normal tissue. (E) The tracer should ideally penetrate the blood-brain barrier. (F) Incorporation of the reporter molecule in CART cells and subsequent imaging should not impair CART cell functions.

As we have discussed in this review, numerous cell imaging platforms are at various stages of development. Nonspecific strategies targeting T cells can be used for imaging of non-engineered cell therapy, such as TIL or γδT cell therapy or to monitor the T cell response to immune checkpoint blockade. Alternatively, imaging platforms for tracking engineered T cells such as CART cells or TCR-T cells should rely on genetically transduced reporters. A key challenge will be how to select the suitable reporter gene for the appropriate CART cell or type of the cancer to further evaluate the clinical outcomes.

During the last decade, strategies have been applied to enhance the efficacy and safety of immunotherapies. Noninvasively imaging T cells can be applied to improve not only relapse/refractory hematological malignancies but also solid tumors.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported through the Mayo Clinic K2R Pipeline (to S.S.K.), the Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine (to S.S.K.), and the Henry J. Predolin Foundation (to R.S.). We thank Dr. Kah-Whye Peng for providing the images used in Figure 2.

Author contributions

R.S., I.C., and S.S.K. wrote the manuscript. E.L.S. edited the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

S.S.K. is an inventor on patents in the field of CAR immunotherapy that are licensed to Novartis (through an agreement between the Mayo Clinic, University of Pennsylvania, and Novartis) and to Mettaforge (through the Mayo Clinic). R.S. and S.S.K. are inventors on patents in the field of CAR immunotherapy that are licensed to Humanigen. S.S.K. receives research funding from Kite, Gilead, Juno, Celgene, Novartis, Humanigen, MorphoSys, Tolero, Sunesis, Leahlabs, and Lentigen.

References

- 1.Kochenderfer J.N., Dudley M.E., Kassim S.H., Somerville R.P., Carpenter R.O., Stetler-Stevenson M., Yang J.C., Phan G.Q., Hughes M.S., Sherry R.M. Chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and indolent B-cell malignancies can be effectively treated with autologous T cells expressing an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;33:540–549. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turtle C.J., Hanafi L.A., Berger C., Hudecek M., Pender B., Robinson E., Hawkins R., Chaney C., Cherian S., Chen X. Immunotherapy of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with a defined ratio of CD8+ and CD4+ CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016;8:355ra116. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf8621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kochenderfer J.N., Somerville R.P.T., Lu T., Shi V., Bot A., Rossi J., Xue A., Goff S.L., Yang J.C., Sherry R.M. Lymphoma remissions caused by anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cells are associated with high serum interleukin-15 levels. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:1803–1813. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kochenderfer J.N., Somerville R.P.T., Lu T., Yang J.C., Sherry R.M., Feldman S.A., McIntyre L., Bot A., Rossi J., Lam N., Rosenberg S.A. Long-duration complete remissions of diffuse large B cell lymphoma after anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:2245–2253. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maude S.L., Frey N., Shaw P.A., Aplenc R., Barrett D.M., Bunin N.J., Chew A., Gonzalez V.E., Zheng Z., Lacey S.F. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1507–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee D.W., Kochenderfer J.N., Stetler-Stevenson M., Cui Y.K., Delbrook C., Feldman S.A., Fry T.J., Orentas R., Sabatino M., Shah N.N. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: A phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2015;385:517–528. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61403-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turtle C.J., Hanafi L.A., Berger C., Gooley T.A., Cherian S., Hudecek M., Sommermeyer D., Melville K., Pender B., Budiarto T.M. CD19 CAR-T cells of defined CD4+:CD8+ composition in adult B cell ALL patients. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;126:2123–2138. doi: 10.1172/JCI85309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brentjens R.J., Davila M.L., Riviere I., Park J., Wang X., Cowell L.G., Bartido S., Stefanski J., Taylor C., Olszewska M. CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5:177ra38. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter D.L., Hwang W.T., Frey N.V., Lacey S.F., Shaw P.A., Loren A.W., Bagg A., Marcucci K.T., Shen A., Gonzalez V. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells persist and induce sustained remissions in relapsed refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7:303ra139. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac5415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turtle C.J., Hay K.A., Hanafi L.-A., Li D., Cherian S., Chen X., Wood B., Lozanski A., Byrd J.C., Heimfeld S. Durable molecular remissions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells after failure of ibrutinib. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:3010–3020. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.8519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porter D.L., Levine B.L., Kalos M., Bagg A., June C.H. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraietta J.A., Lacey S.F., Orlando E.J., Pruteanu-Malinici I., Gohil M., Lundh S., Boesteanu A.C., Wang Y., O’Connor R.S., Hwang W.T. Determinants of response and resistance to CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat. Med. 2018;24:563–571. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raje N., Berdeja J., Lin Y., Siegel D., Jagannath S., Madduri D., Liedtke M., Rosenblatt J., Maus M.V., Turka A. Anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy bb2121 in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;380:1726–1737. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brudno J.N., Maric I., Hartman S.D., Rose J.J., Wang M., Lam N., Stetler-Stevenson M., Salem D., Yuan C., Pavletic S. T cells genetically modified to express an anti-B-cell maturation antigen chimeric antigen receptor cause remissions of poor-prognosis relapsed multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36:2267–2280. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.77.8084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen A.D., Garfall A.L., Stadtmauer E.A., Melenhorst J.J., Lacey S.F., Lancaster E., Vogl D.T., Weiss B.M., Dengel K., Nelson A. B cell maturation antigen-specific CAR T cells are clinically active in multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Invest. 2019;129:2210–2221. doi: 10.1172/JCI126397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang M., Munoz J., Goy A., Locke F.L., Jacobson C.A., Hill B.T., Timmerman J.M., Holmes H., Jaglowski S., Flinn I.W. KTE-X19 CAR T-cell therapy in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1331–1342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1914347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sterner R.M., Sakemura R., Cox M.J., Yang N., Khadka R.H., Forsman C.L., Hansen M.J., Jin F., Ayasoufi K., Hefazi M. GM-CSF inhibition reduces cytokine release syndrome and neuroinflammation but enhances CAR-T cell function in xenografts. Blood. 2019;133:697–709. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-10-881722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schuster S.J., Svoboda J., Chong E.A., Nasta S.D., Mato A.R., Anak Ö., Brogdon J.L., Pruteanu-Malinici I., Bhoj V., Landsburg D. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells in refractory B-cell lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:2545–2554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grupp S.A., Kalos M., Barrett D., Aplenc R., Porter D.L., Rheingold S.R., Teachey D.T., Chew A., Hauck B., Wright J.F. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1509–1518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neelapu S.S., Locke F.L., Bartlett N.L., Lekakis L.J., Miklos D.B., Jacobson C.A., Braunschweig I., Oluwole O.O., Siddiqi T., Lin Y. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:2531–2544. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maude S.L., Laetsch T.W., Buechner J., Rives S., Boyer M., Bittencourt H., Bader P., Verneris M.R., Stefanski H.E., Myers G.D. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378:439–448. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teachey D.T., Lacey S.F., Shaw P.A., Melenhorst J.J., Maude S.L., Frey N., Pequignot E., Gonzalez V.E., Chen F., Finklestein J. Identification of predictive biomarkers for cytokine release syndrome after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:664–679. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goff S.L., Morgan R.A., Yang J.C., Sherry R.M., Robbins P.F., Restifo N.P., Feldman S.A., Lu Y.C., Lu L., Zheng Z. Pilot trial of adoptive transfer of chimeric antigen receptor-transduced T cells targeting EGFRvIII in patients with glioblastoma. J. Immunother. 2019;42:126–135. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Rourke D.M., Nasrallah M.P., Desai A., Melenhorst J.J., Mansfield K., Morrissette J.J.D., Martinez-Lage M., Brem S., Maloney E., Shen A. A single dose of peripherally infused EGFRvIII-directed CAR T cells mediates antigen loss and induces adaptive resistance in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9:eaaa0984. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa0984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan R.A., Yang J.C., Kitano M., Dudley M.E., Laurencot C.M., Rosenberg S.A. Case report of a serious adverse event following the administration of T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor recognizing ERBB2. Mol. Ther. 2010;18:843–851. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamers C.H., Sleijfer S., van Steenbergen S., van Elzakker P., van Krimpen B., Groot C., Vulto A., den Bakker M., Oosterwijk E., Debets R., Gratama J.W. Treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma with CAIX CAR-engineered T cells: clinical evaluation and management of on-target toxicity. Mol. Ther. 2013;21:904–912. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed N., Brawley V., Hegde M., Bielamowicz K., Kalra M., Landi D., Robertson C., Gray T.L., Diouf O., Wakefield A. HER2-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified virus-specific T cells for progressive glioblastoma: A phase 1 dose-escalation trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1094–1101. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson K.G., Stromnes I.M., Greenberg P.D. Obstacles posed by the tumor microenvironment to T cell activity: A case for synergistic therapies. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:311–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharpe A.H., Pauken K.E. The diverse functions of the PD1 inhibitory pathway. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018;18:153–167. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J.Y., Yan Y.Y., Li J.J., Adhikari R., Fu L.W. PD-1/PD-L1 based combinational cancer therapy: Icing on the cake. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;11:722. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markovic S.N., Galli F., Suman V.J., Nevala W.K., Paulsen A.M., Hung J.C., Gansen D.N., Erickson L.A., Marchetti P., Wiseman G.A., Signore A. Non-invasive visualization of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with metastatic melanoma undergoing immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: A pilot study. Oncotarget. 2018;9:30268–30278. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alam I.S., Mayer A.T., Sagiv-Barfi I., Wang K., Vermesh O., Czerwinski D.K., Johnson E.M., James M.L., Levy R., Gambhir S.S. Imaging activated T cells predicts response to cancer vaccines. J. Clin. Invest. 2018;128:2569–2580. doi: 10.1172/JCI98509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Natarajan A., Mayer A.T., Xu L., Reeves R.E., Gano J., Gambhir S.S. Novel radiotracer for immunoPET imaging of PD-1 checkpoint expression on tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. Bioconjug. Chem. 2015;26:2062–2069. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niemeijer A.N., Leung D., Huisman M.C., Bahce I., Hoekstra O.S., van Dongen G.A.M.S., Boellaard R., Du S., Hayes W., Smith R. Whole body PD-1 and PD-L1 positron emission tomography in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4664. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07131-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higashikawa K., Yagi K., Watanabe K., Kamino S., Ueda M., Hiromura M., Enomoto S. 64Cu-DOTA-anti-CTLA-4 mAb enabled PET visualization of CTLA-4 on the T-cell infiltrating tumor tissues. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e109866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gibson H.M., McKnight B.N., Malysa A., Dyson G., Wiesend W.N., McCarthy C.E., Reyes J., Wei W.Z., Viola-Villegas N.T. IFNγ PET imaging as a predictive tool for monitoring response to tumor immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2018;78:5706–5717. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larimer B.M., Wehrenberg-Klee E., Dubois F., Mehta A., Kalomeris T., Flaherty K., Boland G., Mahmood U. Granzyme B PET imaging as a predictive biomarker of immunotherapy response. Cancer Res. 2017;77:2318–2327. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allen-Auerbach M., Quon A., Weber W.A., Obrzut S., Crawford T., Silverman D.H., Ratib O., Phelps M.E., Czernin J. Comparison between 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-d-glucose positron emission tomography and positron emission tomography/computed tomography hardware fusion for staging of patients with lymphoma. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2004;6:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.mibio.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernandez-Maraver D., Hernandez-Navarro F., Gomez-Leon N., Coya J., Rodriguez-Vigil B., Madero R., Pinilla I., Martin-Curto L.M. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography: Diagnostic accuracy in lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 2006;135:293–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwee T.C., Kwee R.M., Nievelstein R.A. Imaging in staging of malignant lymphoma: A systematic review. Blood. 2008;111:504–516. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-101899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carson D.A., Kaye J., Wasson D.B. The potential importance of soluble deoxynucleotidase activity in mediating deoxyadenosine toxicity in human lymphoblasts. J. Immunol. 1981;126:348–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radu C.G., Shu C.J., Nair-Gill E., Shelly S.M., Barrio J.R., Satyamurthy N., Phelps M.E., Witte O.N. Molecular imaging of lymphoid organs and immune activation by positron emission tomography with a new [18F]-labeled 2′-deoxycytidine analog. Nat. Med. 2008;14:783–788. doi: 10.1038/nm1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim W., Le T.M., Wei L., Poddar S., Bazzy J., Wang X., Uong N.T., Abt E.R., Capri J.R., Austin W.R. [18F]CFA as a clinically translatable probe for PET imaging of deoxycytidine kinase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:4027–4032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1524212113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ronald J.A., Kim B.S., Gowrishankar G., Namavari M., Alam I.S., D’Souza A., Nishikii H., Chuang H.Y., Ilovich O., Lin C.F. A PET imaging strategy to visualize activated T cells in acute graft-versus-host disease elicited by allogenic hematopoietic cell transplant. Cancer Res. 2017;77:2893–2902. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Griessinger C.M., Maurer A., Kesenheimer C., Kehlbach R., Reischl G., Ehrlichmann W., Bukala D., Harant M., Cay F., Brück J. 64Cu antibody-targeting of the T-cell receptor and subsequent internalization enables in vivo tracking of lymphocytes by PET. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:1161–1166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418391112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yusufi N., Mall S., Bianchi H.O., Steiger K., Reder S., Klar R., Audehm S., Mustafa M., Nekolla S., Peschel C. In-depth characterization of a TCR-specific tracer for sensitive detection of tumor-directed transgenic t cells by immuno-PET. Theranostics. 2017;7:2402–2416. doi: 10.7150/thno.17994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Larimer B.M., Wehrenberg-Klee E., Caraballo A., Mahmood U. Quantitative CD3 PET imaging predicts tumor growth response to anti-CTLA-4 therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2016;57:1607–1611. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.173930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kanwar B., Gao D.W., Hwang A.B., Grenert J.P., Williams S.P., Franc B., McCune J.M. In vivo imaging of mucosal CD4+ T cells using single photon emission computed tomography in a murine model of colitis. J. Immunol. Methods. 2008;329:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seo J.W., Tavaré R., Mahakian L.M., Silvestrini M.T., Tam S., Ingham E.S., Salazar F.B., Borowsky A.D., Wu A.M., Ferrara K.W. CD8+ T-cell density imaging with 64Cu-labeled cys-diabody informs immunotherapy protocols. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;24:4976–4987. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tavaré R., Escuin-Ordinas H., Mok S., McCracken M.N., Zettlitz K.A., Salazar F.B., Witte O.N., Ribas A., Wu A.M. An effective immuno-PET imaging method to monitor CD8-dependent responses to immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2016;76:73–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Volpe A., Kurtys E., Fruhwirth G.O. Cousins at work: How combining medical with optical imaging enhances in vivo cell tracking. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2018;102:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nagy K., Tóth M., Major P., Patay G., Egri G., Häggkvist J., Varrone A., Farde L., Halldin C., Gulyás B. Performance evaluation of the small-animal nanoScan PET/MRI system. J. Nucl. Med. 2013;54:1825–1832. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.119065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deleye S., Van Holen R., Verhaeghe J., Vandenberghe S., Stroobants S., Staelens S. Performance evaluation of small-animal multipinhole μSPECT scanners for mouse imaging. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2013;40:744–758. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koya R.C., Mok S., Comin-Anduix B., Chodon T., Radu C.G., Nishimura M.I., Witte O.N., Ribas A. Kinetic phases of distribution and tumor targeting by T cell receptor engineered lymphocytes inducing robust antitumor responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:14286–14291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008300107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moroz M.A., Zhang H., Lee J., Moroz E., Zurita J., Shenker L., Serganova I., Blasberg R., Ponomarev V. Comparative analysis of T cell imaging with human nuclear reporter genes. J. Nucl. Med. 2015;56:1055–1060. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.159855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yaghoubi S.S., Jensen M.C., Satyamurthy N., Budhiraja S., Paik D., Czernin J., Gambhir S.S. Noninvasive detection of therapeutic cytolytic T cells with [18F]-FHBG PET in a patient with glioma. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2009;6:53–58. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jeong J.S., Lee S.W., Hong S.H., Lee Y.J., Jung H.I., Cho K.S., Seo H.H., Lee S.J., Park S., Song M.S. Antitumor effects of systemically delivered adenovirus harboring trans-splicing ribozyme in intrahepatic colon cancer mouse model. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:281–290. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tjuvajev J.G., Stockhammer G., Desai R., Uehara H., Watanabe K., Gansbacher B., Blasberg R.G. Imaging the expression of transfected genes in vivo. Cancer Res. 1995;55:6126–6132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jang S.J., Kang J.H., Kim K.I., Lee T.S., Lee Y.J., Lee K.C., Woo K.S., Chung W.S., Kwon H.C., Ryu C.J. Application of bioluminescence imaging to therapeutic intervention of herpes simplex virus type I—Thymidine kinase/ganciclovir in glioma. Cancer Lett. 2010;297:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keu K.V., Witney T.H., Yaghoubi S., Rosenberg J., Kurien A., Magnusson R., Williams J., Habte F., Wagner J.R., Forman S. Reporter gene imaging of targeted T cell immunotherapy in recurrent glioma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9:eaag2196. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carrasco N. Iodide transport in the thyroid gland. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1993;1154:65–82. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(93)90017-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sakemura R., Suksanpaisan L., Khadka R.H., Newsom A.N., Hansen M.J., Cox M.J., Hefazi M., Roman C.M., Schick K.J., Tapper E.E. Development of a sensitive and efficient reporter platform for the detection of chimeric antigen receptor T cell expansion, trafficking, and toxicity. Blood. 2019;134(Suppl 1):53. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Emami-Shahri N., Foster J., Kashani R., Gazinska P., Cook C., Sosabowski J., Maher J., Papa S. Clinically compliant spatial and temporal imaging of chimeric antigen receptor T-cells. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1081. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03524-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Penheiter A.R., Russell S.J., Carlson S.K. The sodium iodide symporter (NIS) as an imaging reporter for gene, viral, and cell-based therapies. Curr. Gene Ther. 2012;12:33–47. doi: 10.2174/156652312799789235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Portulano C., Paroder-Belenitsky M., Carrasco N. The Na+/I− symporter (NIS): Mechanism and medical impact. Endocr. Rev. 2014;35:106–149. doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dadachova E., Carrasco N. The Na/I symporter (NIS): Imaging and therapeutic applications. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2004;34:23–31. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dispenzieri A., Tong C., LaPlant B., Lacy M.Q., Laumann K., Dingli D., Zhou Y., Federspiel M.J., Gertz M.A., Hayman S. Phase I trial of systemic administration of Edmonston strain of measles virus genetically engineered to express the sodium iodide symporter in patients with recurrent or refractory multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2017;31:2791–2798. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Msaouel P., Opyrchal M., Dispenzieri A., Peng K.W., Federspiel M.J., Russell S.J., Galanis E. Clinical trials with oncolytic measles virus: Current status and future prospects. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2018;18:177–187. doi: 10.2174/1568009617666170222125035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Russell S.J., Federspiel M.J., Peng K.W., Tong C., Dingli D., Morice W.G., Lowe V., O’Connor M.K., Kyle R.A., Leung N. Remission of disseminated cancer after systemic oncolytic virotherapy. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014;89:926–933. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reubi J.C., Waser B., Schaer J.C., Laissue J.A. Somatostatin receptor sst1–sst5 expression in normal and neoplastic human tissues using receptor autoradiography with subtype-selective ligands. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2001;28:836–846. doi: 10.1007/s002590100541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamada Y., Post S.R., Wang K., Tager H.S., Bell G.I., Seino S. Cloning and functional characterization of a family of human and mouse somatostatin receptors expressed in brain, gastrointestinal tract, and kidney. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:251–255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vedvyas Y., Shevlin E., Zaman M., Min I.M., Amor-Coarasa A., Park S., Park S., Kwon K.-W., Smith T., Luo Y. Longitudinal PET imaging demonstrates biphasic CAR T cell responses in survivors. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e90064. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.90064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cavalla P., Schiffer D. Neuroendocrine tumors in the brain. Ann. Oncol. 2001;12(Suppl 2):S131–S134. doi: 10.1093/annonc/12.suppl_2.s131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang H., Moroz M.A., Serganova I., Ku T., Huang R., Vider J., Maecke H.R., Larson S.M., Blasberg R., Smith-Jones P.M. Imaging expression of the human somatostatin receptor subtype-2 reporter gene with 68Ga-DOTATOC. J. Nucl. Med. 2011;52:123–131. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.079004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heidenreich A., Bastian P.J., Bellmunt J., Bolla M., Joniau S., van der Kwast T., Mason M., Matveev V., Wiegel T., Zattoni F., Mottet N., European Association of Urology EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: Treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 2014;65:467–479. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rowe S.P., Gage K.L., Faraj S.F., Macura K.J., Cornish T.C., Gonzalez-Roibon N., Guner G., Munari E., Partin A.W., Pavlovich C.P. 18F-DCFBC PET/CT for PSMA-based detection and characterization of primary prostate cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2015;56:1003–1010. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.154336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Calais J., Fendler W.P., Eiber M., Gartmann J., Chu F.I., Nickols N.G., Reiter R.E., Rettig M.B., Marks L.S., Ahlering T.E. Impact of 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT on the management of prostate cancer patients with biochemical recurrence. J. Nucl. Med. 2018;59:434–441. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.202945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.US Food and Drug Administration . 2020. FDA approves first PSMA-targeted PET imaging drug for men with prostate cancer.https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-psma-targeted-pet-imaging-drug-men-prostate-cancer [Google Scholar]

- 79.Minn I., Huss D.J., Ahn H.H., Chinn T.M., Park A., Jones J., Brummet M., Rowe S.P., Sysa-Shah P., Du Y. Imaging CAR T cell therapy with PSMA-targeted positron emission tomography. Sci. Adv. 2019;5:eaaw5096. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw5096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Emmett L., Crumbaker M., Ho B., Willowson K., Eu P., Ratnayake L., Epstein R., Blanksby A., Horvath L., Guminski A. Results of a prospective phase 2 pilot trial of 177Lu-PSMA-617 therapy for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer including imaging predictors of treatment response and patterns of progression. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer. 2019;17:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Castanares M.A., Mukherjee A., Chowdhury W.H., Liu M., Chen Y., Mease R.C., Wang Y., Rodriguez R., Lupold S.E., Pomper M.G. Evaluation of prostate-specific membrane antigen as an imaging reporter. J. Nucl. Med. 2014;55:805–811. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.134031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Likar Y., Zurita J., Dobrenkov K., Shenker L., Cai S., Neschadim A., Medin J.A., Sadelain M., Hricak H., Ponomarev V. A new pyrimidine-specific reporter gene: a mutated human deoxycytidine kinase suitable for PET during treatment with acycloguanosine-based cytotoxic drugs. J. Nucl. Med. 2010;51:1395–1403. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.074344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McCracken M.N., Vatakis D.N., Dixit D., McLaughlin J., Zack J.A., Witte O.N. Noninvasive detection of tumor-infiltrating T cells by PET reporter imaging. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:1815–1826. doi: 10.1172/JCI77326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sellmyer M.A., Richman S.A., Lohith K., Hou C., Weng C.C., Mach R.H., O’Connor R.S., Milone M.C., Farwell M.D. Imaging CAR T cell trafficking with eDHFR as a PET reporter gene. Mol. Ther. 2020;28:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]