Summary

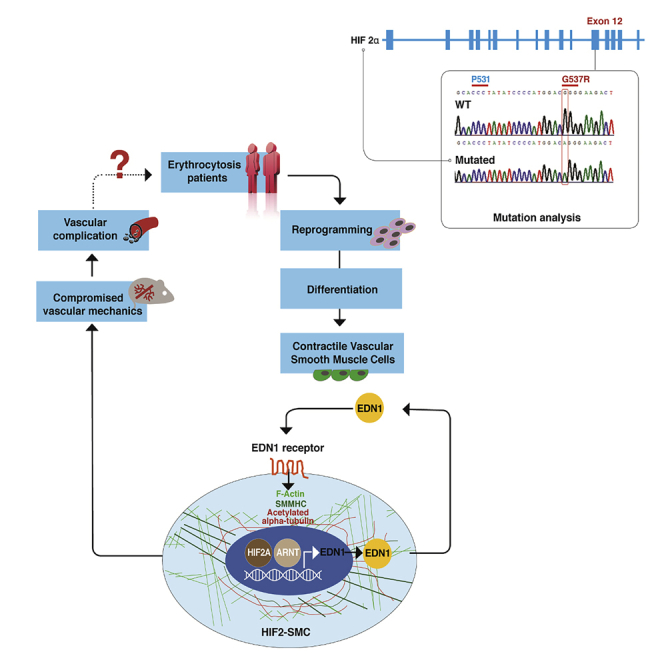

Heterozygous gain-of-function (GOF) mutations of hypoxia-inducible factor 2α (HIF2A), a key hypoxia-sensing regulator, are associated with erythrocytosis, thrombosis, and vascular complications that account for morbidity and mortality of patients. We demonstrated that the vascular pathology of HIF2A GOF mutations is independent of erythrocytosis. We generated HIF2A GOF-induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and differentiated them into endothelial cells (ECs) and smooth muscle cells (SMCs). Unexpectedly, HIF2A-SMCs, but not HIF2A-ECs, were phenotypically aberrant, more contractile, stiffer, and overexpressed endothelin 1 (EDN1), myosin heavy chain, elastin, and fibrillin. EDN1 inhibition and knockdown of EDN1-receptors both reduced HIF2-SMC stiffness. Hif2A GOF heterozygous mice displayed pulmonary hypertension, had SMCs with more disorganized stress fibers and higher stiffness in their pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells, and had more deformable pulmonary arteries compared with wild-type mice. Our findings suggest that targeting these vascular aberrations could benefit patients with HIF2A GOF and conditions of augmented hypoxia signaling.

Subject areas: Pathophysiology, Biophysics, Biomechanics

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

HIF2-SMCs are stiffer than WT-SMCs and differ in contractile SMC marker expression

-

•

HIF2-SMCs and WT-SMCs differ in EDN1 production and ECM composition

-

•

HIF- 2α induces EDN1; EDNI subsequently induces SMC stiffening

-

•

Hif2A GOF mouse arterial SMCs have more disorganized stress fibers and are stiffer

Pathophysiology; Biophysics; Biomechanics

Introduction

Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF-1 and HIF-2) maintain oxygen homeostasis and control many physiological processes, including angiogenesis and erythropoiesis (Semenza, 2001). HIFs activity is tightly regulated in an oxygen-dependent manner; in normoxia, HIFs-alpha subunits are degraded, whereas in hypoxia HIFs-alpha proteins stabilize, bind to the constitutively expressed beta subunits, and HIFs dimers translocate into the nucleus to activate a broad range of downstream targets (Kaelin and Ratcliffe, 2008; Majmundar et al., 2010). Mutations affecting multiple components in the HIF pathway have been identified as causes for the expansion of red blood cell mass termed “erythrocytosis” or “polycythemia.” These mutations include loss-of-function mutations of the two principal HIFs' negative regulators, i.e. prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 (PHD2 encoded by EGLN1) and von Hippel Lindau (VHL) as well as gain-of-function (GOF) mutations in HIF2A (encoded by EPAS1). When any one of these proteins are mutated, HIF2A, the principal regulator of erythropoietin (EPO), is stabilized and leads to erythrocytosis (Wenger and Hoogewijs, 2010). Management of erythrocytosis is limited to reducing red blood cells via venesection, which does not ameliorate vascular complications and may even have a detrimental effect on those complications (Sergueeva et al., 2015; Gordeuk et al., 2019). Here we propose that the morbidity and mortality of these rare congenital disorders of HIF-2 upregulation are defined not by their erythroid phenotype but by HIF-2 driven vascular and thrombosis complications.

Previous work has shown that a knock-in mouse model with a GOF missense mutation in EPAS1, corresponding to a human-associated erythrocytosis mutation (G537W), exhibits erythrocytosis and pulmonary hypertension (PH) (Tan et al., 2013). Studies in mice also show that accumulation of HIF2A via the deletion of EGLN1 in ECs is sufficient to cause vascular stiffening independent of erythrocytosis (Kapitsinou et al., 2016b; Dai et al., 2016). Endothelium signaling and interactions with the surrounding smooth muscle cells (SMCs) play a crucial role in regulating vascular function and in mediating vascular tone by generating and maintaining the balance between vasodilators and vasoconstrictors. When the endothelium is dysfunctional, the expression of endothelin 1 (EDN1) increases, causing a decrease in endothelial nitric oxide (NO) production (Iglarz and Clozel, 2007). This altered balance results in a shift toward increased vascular tone due to increased deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, as well as hyperplasia and hypertrophy of SMCs. In the pulmonary arteries (PAs), this leads to stiffening, as shown in patients suffering from PH (Furchgott and Vanhoutte, 1989; Cacoub et al., 1997; Ergul et al., 2006). Recently, other studies have suggested that this stiffening of arteries leads to systemic hypertension, which further leads to vessel stiffening everywhere in the body.

The availability of human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) provides a unique approach to interrogate the causes of morbidity and mortality of individuals inheriting HIF2A GOF mutations. These HIF2A GOF (HIF2) hiPSCs allowed us to determine the role of individual cellular vascular components on vascular irregularities in not only ECs but also in SMCs, which dictate the mechanical properties of blood vessels in healthy individuals and patients suffering from vascular and thrombotic complications. Herein, we generated two sets of HIF2 hiPSC lines from the peripheral blood of patients with erythrocytosis caused by HIF2A GOF, differentiated them into ECs and SMCs, and demonstrated that these heterozygous mutations (G537R and M535V) are sufficient to induce cellular alterations in SMCs. We also performed in vivo studies using heterozygous mice to further demonstrate early onset of pulmonary hypertension, alterations in SMCs, and compromised vascular mechanics.

Results

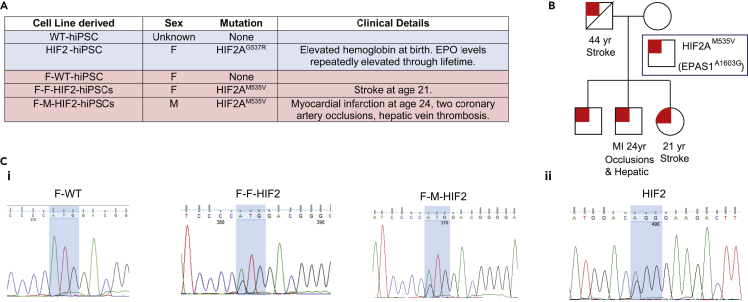

Patient-specific HIF2A missense mutation hiPSC

Five sets of hiPSCs were generated from peripheral blood CD34+ mononuclear cells (MNCs) with the indicated mutations (Figure 1A). Three of the hiPSC cell lines were from a five-generational pedigree with erythrocytosis inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. This pedigree displayed diverse vascular complications, such as myocardial infarction and stroke, in young individuals (Figure 1B). No other risk factors for cardiovascular morbidity were present. Furthermore, these complications were not prevented by the strict control of their erythrocytosis aimed to reduce hematocrit by regular phlebotomies. We generated the indicated lines from a healthy mother and two offspring.

Figure 1.

Generation of hiPSC lines with HIF2A GOF mutation

(A) Five hiPSC lines were isolated from peripheral blood CD34+ MNCs. Red-filled cells indicate familial lines; blue-filled cells indicate non-familial lines.

(B) The HIF2AM535V (EPAS1A1603G) mutation family participated in donating peripheral blood CD34+ cells for generating hiPSCs.

(C) Sanger sequencing results show that (1) F-HIF2-hiPSC lines each has a single heterozygous mutation of M535V (EPAS1A1603G) and (2) the HIF2-hiPSC line has a heterozygous missense mutation of HIF2AG537R (G→ A on exon 12 of EPAS1 gene).

See also Figures S1 and S2.

All these hiPSC lines were found to maintain normal karyotype, expressed pluripotent markers, and underwent differentiation to all three germ layers (Figures S1 and S2). Their genotyping confirmed the mutations found in the native cells of these individuals (Figure 1B). Similar to other cases of erythrocytosis-associated EPAS1 mutations, these mutations (G537R and M535V) affect a residue C-terminal to the LXXLAP motif (where underlining indicates the site of hydroxylation). Mutations in residue C-terminal to the LXXLAP motif have been shown to result in impaired degradation and abnormal stabilization of HIF2A (Furlow et al., 2009).

Endothelial cell differentiation and maturation from HIF2-hiPSCs

We first examined whether HIF2-hiPSCs have a similar vascular differentiation potential as the WT-hiPSC. We used a feeder-free protocol adapted from Lian et al. (Lian et al., 2014; Chan et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2017) (Figure S3A) to derive early vascular cells (EVCs), a bicellular population that includes both vascular endothelial cadherin (VEcad)+ early ECs and platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFR)+ support cells (Chan et al., 2015; Kusuma et al., 2013). On day 6 of EC differentiation, HIF2-hiPSCs and F-F-HIF2-hiPSCS generated a higher percentage of kinase insert domain receptor (KDR)+ cells, and HIF2-hiPSCs also generated a higher percentage of CD31+ cells. F-F-HIF2-hiPSCs also exhibited a trend toward a higher percentage of CD31+ cells; however, this was not statistically significant (Figures 2A and 2B). Day 8 EVCs contained cobblestone-like clusters, suggestive of an endothelial-like morphology (Figure S3B). HIF2-hiPSC-derived EVCs contain both early ECs positive for VEcad at intercellular junctions and early pericytes positive for PDGFRβ (Figure S3C). Overall, we found that HIF2- and F-HIF2-hiPSCs have a similar efficiency in EC derivation when compared with the WT- and F-WT-hiPSC lines (Figures S3D–S3F). When embedded in 3D Collagen I gel, the EVCs self-assembled and formed networks (Figure S3G).

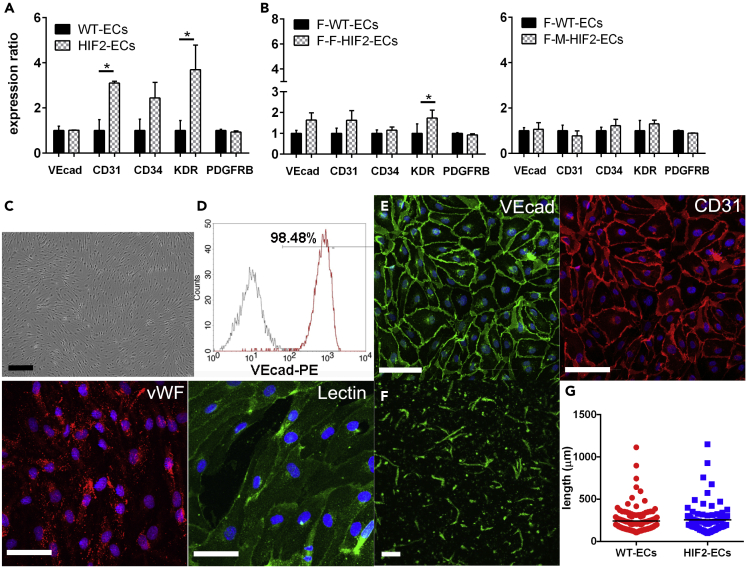

Figure 2.

Maturation of functional HIF2-ECs

(A and B) Flow cytometry of vascular marker expression on day 6 differentiation of (A) WT-hiPSC versus HIF2-hiPSC and (B) F-WT-hiPSC versus F-HIF2-hiPSC (N = 3).

(C and D) (C) Light microscopy image of sorted VEcad+ cells. Scale bar is 200 μm. (D) Representative flow cytometry histogram for VEcad expression of magnetically sorted VEcad+ cells (N = 4).

(E) Representative immunofluorescence (IF) images of VEcad, CD31, vWF, and binding of Ulex europaeus lectin. Images are shown for ECs derived from HIF2-hiPSCs. Nuclei in blue. Scale bars are 100 um.

(F) 3-dimensional vascular networks of HIF2-ECs in collagen I gels. Scale bar is 200 μm.

(G) Length of 3D networks in WT-ECs and HIF2-ECs (N = 3). Data are represented as individual EC networks (points) and mean (black line). Significance level is set at ∗p < 0.05 for a two-tailed t test.

Following successful EVC differentiation from HIF2-hiPSC, we examined endothelial maturation and functionality of the HIF2-hiPSC- and F-HIF2-hiPSC-derived ECs (hereafter, abbreviated to HIF2-ECs and F-HIF2-ECs). VEcad+ early ECs were sorted and expanded for four additional passages (Kusuma et al., 2013, 2015), in which they maintained their cobblestone morphology as typical ECs (Figure 2C). These sorted and cultured ECs were verified to have at least 98% VEcad+ cells (Figure 2D). HIF2-ECs had membrane expression of VEcad and CD31, as well as cytoplasmic punctate expression of von Willebrand factor (vWF). These HIF2-ECs also demonstrated the ability to bind to lectin Ulex europaeus (Figure 2E). Altogether, HIF2- and F-HIF2-ECs exhibited mature endothelial characteristics comparable to ECs derived from WT- and F-WT-hiPSCs (Kusuma et al., 2013; Chan et al., 2015) (hereafter, abbreviated to WT-ECs and F-WT-ECs). When embedded in collagen I gels, HIF2-ECs self-assembled to form luminal vascular networks at a similar capacity as WT-ECs (Figures 2F and 2G).

The HIF2A heterozygous mutation affects the expression of vasodilators and vasoconstrictors in HIF2-ECs

A single missense mutation located near the hydroxylation site, Pro-531, can interfere with the hydroxylation of HIF2A and lead to its accumulation under atmospheric conditions in vitro (Furlow et al., 2009; Lee and Percy, 2011). We began by examining whether HIF2A accumulation could be observed in HIF2-ECs generated from a patient with a heterozygous mutation near the HIF2A proline hydroxylation. Comparing the expression level of HIF2A in HIF2-ECs and WT-ECs cultured in atmospheric (21% oxygen) and hypoxic (1.0% oxygen) conditions, we observed higher levels of HIF2A expression in HIF2-ECs in comparison to WT-ECs under atmospheric conditions (Figure 3A). Under hypoxic conditions, both HIF2-ECs and WT-ECs expressed higher level of HIF2A.

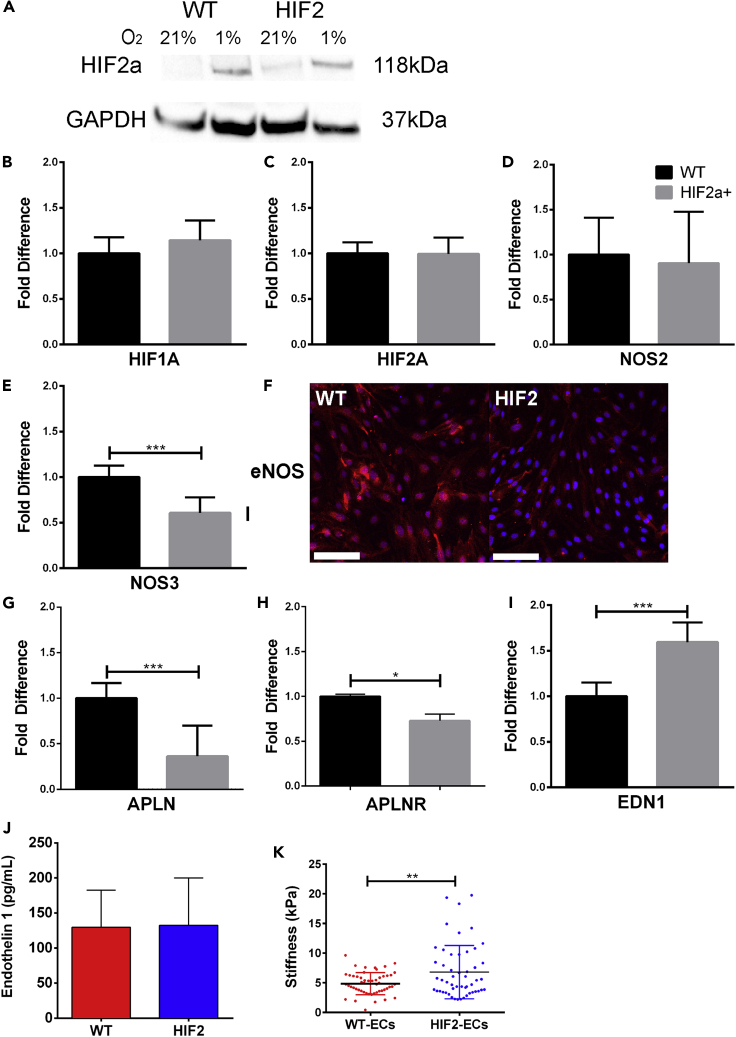

Figure 3.

HIF2A-mutation-induced differences in vasoconstrictor and vasodilators in HIF2-ECs

(A) Representative western blot of HIF2A for HIF2-ECs and WT-ECs.

(B–E; G–I) qRT-PCR of HIF2-ECs. Data are presented as the fold-change difference in reference to WT-ECs. Expression levels were normalized to endogenous control GAPDH expression level (N = 4).

(F) Representative IF images of eNOS stains of WT-ECs and HIF2-ECs (N = 4). Scale bars are 100 μm.

(J) Quantification of EDN1 level in WT-ECs and HIF2-ECs using ELISA (N = 3).

(K) Atomic force microscopy (AFM) analysis of WT-ECs (n = 52) and HIF2-ECs (n = 52) (N = 3). All data are represented as mean ± standard deviation. AFM data is also represented as individual cell measurements. Significance level is set at ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗p < 0.05 for a two-tailed t test.

See also Figures S3, S4, and S6.

We then found that HIF1A and HIF2A were transcribed at similar levels throughout all cell lines (Figures 3B, 3C, and S4). Next, we examined if mRNA expression levels of vasodilators and vasoconstrictors were affected by this HIF2A missense mutation. We found that relative expression levels of nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2), which encodes for a cytokine-inducible NOS, is comparable in both control and HIF2-ECs (Figure 3D). Expression of nitric oxide synthase 3 (NOS3), which encodes endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), was similar or lower in HIF2-mutated ECs when compared with WT-ECs (Figures 3E and S4). Downregulation of NOS3 was further verified in immunostaining of eNOS in which the intensity of labeling was lower in HIF2-ECs when compared with WT-ECs (Figure 3F). In hypoxia, HIF2A is reported to regulate apelin (APLN), a vasodilatory peptide acting by binding to the apelin G-protein-coupled receptor (APLNR) (Kapitsinou et al., 2016b). Here, we found lower APLN and APLNR expression in HIF2-ECs when compared with WT-ECs (Figure 3G), and similar or lower expression levels in F-WT-ECs and F-M-HIF2-ECs (Figure S4). We then examined the expression level of Arginase 1, an NO inhibitor downstream of HIF-2α but could detect its transcript in neither HIF2 nor WT-ECs (Berkowitz et al., 2003; Dai et al., 2016). Next, we examined the EDN1 transcript, a potent vasoconstrictor implicated in the pathogenesis of PH. We found higher expression of EDN1 in both HIF2-ECs and F-HIF2-ECs compared with their WT-EC controls (Figures 3I and S4A) but with similar levels of EDN1 secretion between WT-ECs and HIF2-ECs (Figure 3I). Finally, atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurements revealed that HIF2-ECs were stiffer than WT-ECs (Figure 3K).

Smooth muscle cell differentiation and maturation from HIF2-hiPSCs

Previous studies show that ECs are the primary source for EDN1 generation, but a recent study has demonstrated that EDN1 generated by SMCs may independently modulate vascular tone (Kim et al., 2015). We investigated whether the HIF2A mutation had a detrimental effect on hiPSC-derived SMCs alone (Vo et al., 2010; Wanjare et al., 2013). We followed an established differentiation protocol to generate mature smooth muscle-like cells (mSMLC) and then further matured them into contractile SMCs (Wanjare et al., 2013, 2014). Features of the mSMLCs derived from HIF2-hiPSCs included irregular morphologies, hypertrophy, increased stress fibers, and upregulation of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SMMHC and MYHCII) and EDN1 when compared with mSMLCs derived from WT-hiPSCs (Figures S5A–S5E). When comparing contractile SMCs derived from WT-hiPSCs (hereafter, WT-SMCs) and HIF2-SMCs, as well as, F-WT- and F-HIF2-SMCs, we noticed that HIF2-SMCs (derived from UT2HIF2A-hiPSC line) lacked the typical elongated, spindle-shaped phenotype of contractile SMCs. Instead, HIF2-mutated SMCs exhibited hypertrophy, jagged borders, and excessive amounts of actin stress fibers and acetylated alpha-tubulin (Figures 4A and S6A). The arrangements of F-actin filaments were randomly aligned in HIF2-SMCs but appeared to be more organized and aligned in WT-SMCs. When compared with WT-SMCs, HIF2-SMCs not only express SMMHC at a higher level (Figures 4A and 4B) but also have an increased prevalence of F-actin stress fibers, smooth muscle actin (SMA), and acetylated alpha-tubulin (Figures 4A–4D). Furthermore, EDN1 secretion levels were higher in HIF2-SMCs when compared with WT-SMCs and in F-HIF2-SMCs in comparison to F-WT-SMCs (Figures 4E, 4F, and S6B). Of note, baseline EDN1 concentration was higher in SMCs generated from the family member cell lines when compared with the non-familial cell lines (Figures S4A, S5E, and S6B). Overall, we found qualitative and quantitative phenotypic differences of HIF2-SMCs in both early and mature contractile forms. This suggests that the mutation may have a direct effect in both the early stage and terminally differentiated SMCs.

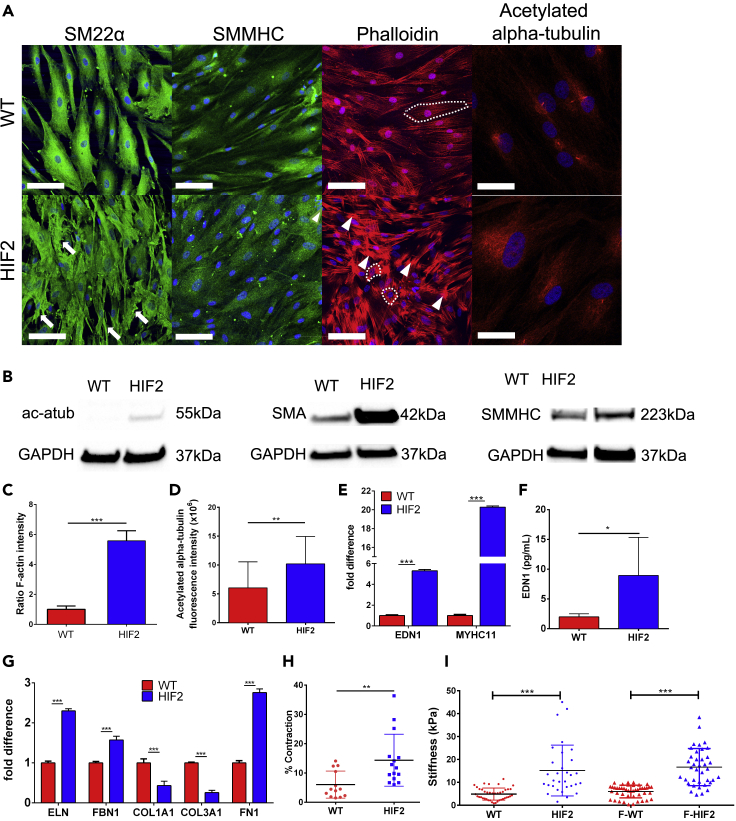

Figure 4.

HIF2-SMCs have abnormal phenotype and changes in ECM deposition compared with WT-SMCs

(A) Representative IF images of SM22a, SMMHC, phalloidin, and acetylated alpha-tubulin staining. White arrows: jagged border; white arrowheads: dense actin fibers; white dotted lines: examples of isotropic fiber arrangement in WT-SMCs and anisotropic fiber arrangement in HIF2-SMCs. Scale bars are 100 μm and 50 μm for acetylated alpha-tubulin.

(B) Representative western blots of acetylated alpha-tubulin, SMA, and SMMHC.

(C and D) Quantification of (C) F-Actin and (D) acetylated alpha-tubulin (N = 4).

(E) qRT-PCR of EDN1 and MYHCII.

(F) Quantification of EDN1 level in WT-SMCs and HIF2-SMCs using ELISA (N = 5).

(G) qRT-PCR of ECM genes. All qPCR data are presented as the fold-change difference in reference to WT-SMCs. Expression levels were normalized to endogenous control of GAPDH expression level (N = 4)

(H) Percent contraction upon carbachol treatment (N = 3).

(I) AFM analysis of WT-SMCs (n = 41) and HIF2-SMCs (n = 31); F-WT-SMCs (n = 45) and F-HIF2-SMCs (n = 38) (N = 3). Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation. Data in H and I are also represented as individual cell measurements. Significance level is set at ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗p < 0.05 for a two-tailed t test.

See also Figures S6–S8.

Increased stiffness in HIF2-SMCs

Increased expression and accumulation of ECM proteins represent one of the main pathobiological aspects of PH (Tuder et al., 2007). We observed significant changes in elastic ECM expression for HIF2-SMCs when compared with WT-SMCs. HIF2-SMCs consistently express higher transcript levels of the elastic fiber components elastin (ELN) and fibrillin-1 (FBN1), as well as fibronectin (FN1), and lower expression levels of collagen (COL1A1 and COL3A1) than WT-SMCs (Figure 4G). A similar observation was made in mSMLCs (Figure S5F). In correlation with the change in transcript level, ECM expression of elastin, fibrillin-1, and fibronectin are strongly increased in the SMLCs and SMCs derived from HIF2-hiPSCs when compared with their WT counterparts (Figure S7). Contractility, in response to carbachol treatment, individual cell stiffnesses measured via AFM were higher in HIF2-mutated SMCs when compared with SMCs derived from WT (Figures 4H, 4I, and S8). Altogether, these observations suggest that the HIF2A mutation in SMCs recapitulates the physiological and pathological observations made in vascular SMCs in PH-related vascular stiffening (Lee et al., 1998).

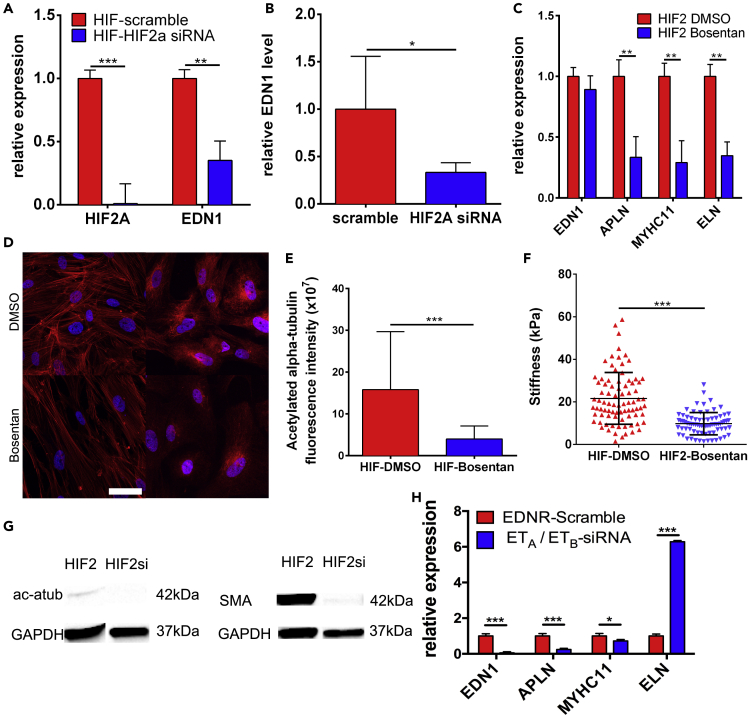

EDN1 modulates HIF2-SMC stiffness

To determine whether the SMC phenotype is regulated through HIF2A activation of EDN1, we first knocked down HIF2A using siRNA to examine if EDN1 levels would be reduced. Four days of post-siRNA treatment, HIF2A and EDN1 transcripts were significantly reduced. EDN1 secretion also decreased by more than 2-fold (Figures 5A, 5B, and S9A). We investigated whether these changes would affect cytoskeletal components in knockdown-HIF2-SMCs, but no significant changes were observed in phalloidin and SMMHC expression (Figure S9B). We specifically blocked EDN1 signaling through Bosentan, an antagonist of EDN1 receptors A and B (ETA and ETB) (Bohm and Pernow, 2007), to investigate whether or not the diseased phenotype of HIF2-SMCs could be diminished by reduction of EDN1 signaling and its downstream targets. Transcript levels of EDN1 were not affected, as Bosentan inhibits EDN1 binding rather than synthesis. We observed a decrease in the APLN transcript, which may have been due to reduced EDN1 signaling (Figure 5C). Both MYHCII and ELN transcripts were reduced post-Bosentan treatment (Figure 5C). EDN1 is known to regulate vascular tone via cytoskeleton components and secretion of ECMs. At the microtubule level, we noticed that Bosentan-treated HIF2-SMCs had less acetylated alpha-tubulin (stabilized microtubules) in the cytoplasm (Figures 5D and 5E). ECM expression of both the DMSO- and Bosentan-treated HIF2-SMCs was also studied and found to be reduced in treated HIF2-SMCs (Figure S10). After 6 days of 10 μM Bosentan treatment, the stiffness of HIF2-SMCs was significantly reduced in comparison to DMSO-treated controls, likely due to reduced expression of cytoskeletal components, as observed in Bosentan-treated HIF2-SMCs, and further confirmed in HIF2A siRNA knockdown HIF2-SMCs (Figures 5F, 5G and S11). In order to reduce the possibility of any non-specific effects of Bosentan, both HIF2- and WT-SMCs were also treated with siRNA to knockdown ETA and ETB. To better model the effects of the drug, a 2:1 ratio ETA to ETB siRNA was chosen. We found similar decreasing trends in transcript levels of EDN1, APLN, and MYHCII but an increase in ELN (Figure 5H). This increase could be due to the ratio of siRNA chosen. Altogether, our findings demonstrate that the HIF2A GOF mutation affects downstream EDN1 secretion and signaling, which in turn increases cell stiffness via recruitment and regulation of cytoskeletal proteins.

Figure 5.

Upregulated EDN1 modulates HIF2-SMC stiffness

(A) Level of HIF2A and EDN1 transcripts after siRNA knockdown of HIF2A (N = 3).

(B) EDN1 secretion in control and HIF2A siRNA knockdown HIF2-SMCs (N = 5).

(C) qRT-PCR of EDN1, APLN, MYHCII, and ELN transcripts in DMSO control and Bosentan-treated HIF2-SMCs (N = 3).

(D) Representative IF images of cytoskeletal protein expression of DMSO control and Bosentan-treated HIF2-SMCs. Scale bar is 50 μm.

(E) Corrected fluorescence intensity of acetylated alpha-tubulin stain in DMSO-treated HIF2-SMC control and Bosentan-treated HIF2-SMC (N = 4).

(F) AFM analysis of DMSO and Bosentan-treated HIF2-SMCs (n = 83 and n = 76, respectively; N = 3).

(G) Representative western blot of acetylated alpha-tubulin and SMA post HIF2A siRNA treatment on HIF2-SMCs.

(H) qRT-PCR of EDN1, APLN, MYHCII, and ELN expression in HIF2-SMCs after siRNA knockdown of ETA and ETB (N = 3). All data are represented as mean ± standard deviation. Data in F are also represented as individual cell measurements. Significance level is set at ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗p < 0.05 for a two-tailed t test.

See also Figures S9 and S10.

Effects of HIF2A mutation on co-culture of hiPSC-ECs and SMCs

After characterizing the HIF2-ECs and HIF2-SMCs individually, we sought to investigate interactions between the mutated cell types through various co-culture model combinations. Because ECs and SMCs constantly interact and regulate vasodilation and vasoconstriction in maintaining vascular homeostasis (Mas, 2009; Sandoo et al., 2010), we wanted to examine whether an additive effect of the mutation was observed in HIF2-SMCs by the HIF2-EC-SMC co-cultures. For these experiments, the WT-SMC-only culture was designated as the experimental control (Figure S12A). When WT-SMCs were co-cultured with WT-ECs, there was a slight decrease in the level of EDN1 in WT-SMCs compared with WT-SMCs cultured alone, suggesting a regulatory effect for the ECs. This same regulatory effect was observed in HIF2-SMCs co-cultured with WT-ECs, in which the EDN1 expression was decreased by 25 percent when compared with HIF2-SMCs cultured alone. In co-cultures with HIF2-ECs, EDN1 in HIF2-SMCs increased by 25%, correlating to the imbalanced levels of vasodilators and vasoconstrictors characteristic of dysfunctional vessels (Figure S12B).

We then examined secreted EDN1 concentrations. We compared the secreted EDN1 concentration of co-culture combinations of WT-SMCs or HIF2-SMCs. We found that WT-SMCs cultured with either WT-ECs or HIF2-ECs secreted EDN1 at similar concentrations (Figure S12C). The same observations were made for HIF2-SMCs cultured with WT-ECs or HIF2-ECs. These results suggest that SMCs play a regulatory role in EDN1 availability in which the HIF2A mutation is responsible for increased EDN1 expression and secretion as shown with the higher secreted EDN-1 levels in both HIF2-SMCs + HIF2-ECs and HIF2-SMCs + WT-ECs co-culture combinations. Overall, the co-culture system conveys a unique perspective in that EDN1 secretion is regulated predominantly by the condition of the SMCs, and co-culturing with healthy ECs is not sufficient for mitigating the effects of the HIF2A mutation.

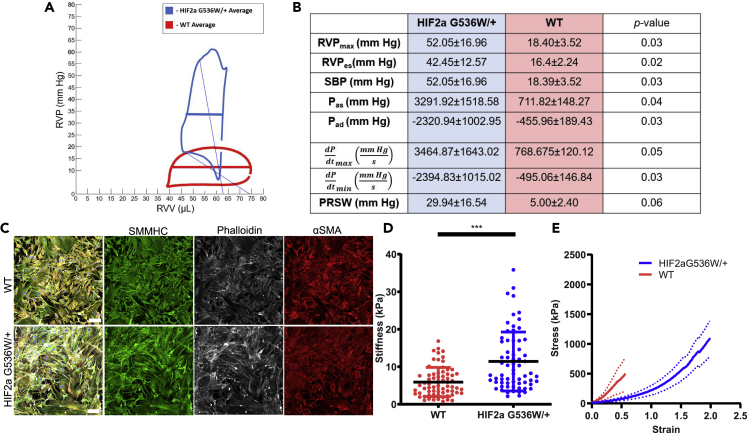

HIF2A GOF mutation causes pulmonary hypertension in mice

Because HIF2A mutation affects hiPSC-derived SMC properties, we furthered our investigation to heterozygous Hif2a G536W knock-in mice (Hif2a) and compared them with their WT counterparts (Tan et al., 2013). First, we determined whether HIF2A GOF mutation causes pulmonary hypertension in young mice (Figure 6A). We evaluated right heart function using cardiac catherization to obtain pressure-volume (PV) loops (Figures 6A and 6B). Heart rates were similar across both cohorts. Significant increases in right ventricular pressures (RVPmax, RVPes, SBP, Pas, Pad) were noted in the young HIF2A GOF mutant mice and confirmed pulmonary hypertension. An increase in contractility (dP/dtmax, PRSW) and relaxation (dP/dtmin) also demonstrated an apparent impairment in right heart function.

Figure 6.

Pulmonary arterial vessels and SMCs in HIF2aG536W/+ mice

(A and B) (A) Average PV loops for a representative HIF2aG536W/+ mouse compared with a C57/BL6 control. (B) A comparison of HIF2aG536W/+ mice (blue) and their WT counterparts (red), N = 3, confirms pulmonary hypertension. The right column shows the results of a student's t test.

(C) IF images of SMMHC, phalloidin, and αSMA staining. Scale bars are 100 μm.

(D) AFM analysis of SMCs isolated from pulmonary arteries of HIF2aG536W/+mice compared with C57/BL6 controls (n = 66; N = 3, and n = 68; N = 3, respectively—each N is a pool from 2 animals). Data is represented as mean ± standard deviation and as individual cell measurements.

(E) Circumferential tensile testing of the mPA from HIF2aG536W/+ (N = 6) and C57/BL6 age-matched control mice (N = 6). The solid line represents the mean, and the dotted line represents standard deviation. Significance level is set at ∗∗∗p < 0.001 for a two-tailed t test.

We next sought to examine whether these mice had any alteration in the function of the main pulmonary (mPA), SMCs, and vascular mechanics. Similarly to iPSC-derived HIF2-mutated SMCs, SMCs isolated from the pulmonary arteries of Hif2a mice exhibited jagged borders and excessive amounts of disordered actin stress fibers (Figure 6C). They were also significantly stiffer than their WT counterparts when measured via AFM (Figure 6D). As it was vital to obtain functional in vivo artery assessment, we next examined the response of the mPA under tensile stress. We focused on the mPA response to stress and found that the Hif2a mice have pulmonary arteries that are significantly more deformable when compared with WT mice, suggesting their compromised ability to adequately respond to repetitive physiological stress (Figure 6E).

Next, we attempted to determine the mechanism responsible for the differences in tissue-level and cellular-level mechanical properties (Figure S13). We assessed whether the mRNA expression levels of major ECM components—ELN, collagen 1 (Col1a1), collagen 3 (Col3a1), Fbn1, fibulin4 (Fbln4), and fibulin5 (Fbln5)—and cytoskeletal motor protein MYHCII differed between the lungs of Hif2a mice and their wild-type counterparts (Figure S13A). We found no statistically significant differences. Then we examined mRNA expression levels of major remodeling enzymes—metalloproteases-2, -9, and -14 (MMP2, -9, -14)—and found no difference between the two groups (Figure S13B). However, we discovered significant differences in the endogenous ratio of ELN with respect to Col3a1 (ELN/Col3a1) and in the endogenous ratio of Col1a1 with respect to Col3a1 (Col1a1/Col3a1), with the Hif2a lungs having higher ratios in both cases (Figure S13C). To assess whether these differences in endogenous ratios—ELN/Col3a1 and Col1a1/Col3a1—translated to the tissue-level scale, we performed histological staining and quantification on mPAs and lung sections. We completed hematoxylin & eosin (H&E), Masson's trichrome stain (MAS), and Verhoeff–Van Giesson (VVG) staining and quantified the medial layer of the vessels for % collagen, % elastin, % total ECM, collagen/elastin ratio, and total area for both mPA and lungs, all of which showed no statistically significant differences (Figures S13D and S13E). However, higher magnification examination of the VVG staining indicated that elastin banding in the Hif2a exhibited a much more heterogeneous morphology (Figures S13Fi–S13Fiii). Although the visual heterogeneity of the elastin bands for Hif2a mice was apparent (Figures S13Fii and S13Fiii), further quantification of the number of elastin breaks, elastin branch points, total lamellae, lamellar thickness, and interlamellar distance did not identify a singular tissue-level elastin parameter that clearly differed between the Hif2a mice and their wild-type counterparts (Figures S13Fiv–S13Fviii).

Discussion

Studies using mice and in vitro EC cultures have demonstrated that HIF-2α, not HIF-1α, is the key transcription factor responsible for the pathogenesis of PH (Kapitsinou et al., 2016b; Dai et al., 2016). Upon successful differentiation of HIF2-ECs, we examined these cells for mature marker expression, performed functional analyses, and investigated levels of vasoactive components. Although morphologically and functionally HIF2-ECs were not as significantly different when compared with WT-ECs, HIF2-ECs were found to be stiffer when measured via AFM. We observed a slight increase at the EDN1 transcript level, which did not result in significant differences in the EDN1 secretion levels. A plausible explanation is that the accumulation of HIF-2α under normoxic conditions is not significant enough to exert an effect on the ECs. We observed variability in the expression of KDR, CD31, NOS3, APLN, and APLNR across our HIF2-EC lines. One potential cause for the EC-heterogeneity is the difference between macrovascular and microvascular ECs. Perhaps ECs of the larger arterial and venous origins are more sensitive to slight changes in HIF-2α levels due to the direct effect of vascular stiffening on these structures, unlike microvascular ECs that are affected at later stages of the disease and are more similar to HIF2-ECs. Another cause may be the differing environmental factors in the lives of the donors.

We then analyzed another critical component of the macrovasculature, the SMCs. We successfully differentiated patient-specific HIF2-iPSCs into mSMLCs and contractile SMCs. In the early stages of SMC differentiation, we were able to detect a noticeable difference between WT and HIF2-mSMLCs in terms of cell size and morphology. This was demonstrated by the presence of dense actin fibers and an irregular rhomboid shape, rather than the typical spindle-like appearance (Rensen et al., 2007). In addition, we observed a significant increase in EDN1 transcript and EDN1 secretion, as well as MYHCII expression. Differences in cell morphology during differentiation and further analysis suggests that the HIF2A mutation results in different phenotypes in HIF2-SMCs both early on in development and at the end of differentiation. This may be due to HIF2A accumulation causing a more stressful environment for SMCs during differentiation, leading to changes in phenotype. These findings further highlight the use of iPSCs as a powerful tool in disease modeling and translational medical research (Soldner and Jaenisch, 2012) and as a platform to monitor the impact of the EPAS1 GOF mutations during SMC development (Dash et al., 2015; Soldner and Jaenisch, 2012).

On the molecular level, it is evident that the HIF2A GOF mutations lead to higher expression of the potent vasoconstrictor, EDN1, as well as the cytoskeletal motor protein, MYHCII, which could further contribute to the intrinsic stiffness via interactions with F-actin. Another notable finding in our study is that HIF2 SMCs secreted higher levels of EDN1 when compared with WT SMCs. However, SMCs (and ECs) generated from two independent sets of hiPSC lines demonstrated different baseline secretions of EDN1 (an average of 2 pg/mL for WT-SMCs in comparison to 15 pg/mL for F-WT-SMCs). This could be due to either patient-to-patient variability or a discrepancy caused by different hiPSC reprogramming methods. Despite the differences in baseline levels, significantly higher amounts of secreted EDN1 were found across the board in HIF2-SMCs when compared with WT-SMCs. Altogether, these results demonstrated that the diseased SMC phenotype potentially contributes to vascular stiffening, independent of endothelial dysfunction.

However, on the extracellular level, we found increased expression of ECM proteins including elastin, fibrillin-1, and fibronectin in these diseased SMCs, while observing lower transcript levels of COLI and COLIII (Rensen et al., 2007). HIF2-SMCs were found to be much stiffer when measured by AFM. In HIF2-SMCs cultured in vitro, stiffness is most likely an effect of the cytoskeletal changes. Individually assessing the SMCs in vitro allowed us to demonstrate that the HIF2A GOF mutation can induce changes in SMC to the stiffness independent of endothelial dysfunction (Sehgel et al., 2013). We propose that the increase in stiffness could be due to an increase of F-actin polymerization and increased actin-myosin interaction induced by high levels of EDN1 (Xiang et al., 2010). A plausible mechanism may be that high levels of EDN1 binding to the ETA receptor leads to increased actin and myosin formation and interactions, thus generating increased cytoskeletal tension.

Although we have investigated the effects of the HIF2A mutation in ECs and SMCs respectively, the interaction between ECs and SMCs, as in blood vessels, is critical for maintaining proper function via paracrine signaling between the endothelium and the mural cells. By co-culturing these two cell types, a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of HIF2A mutation in vascular stiffening can be elucidated. We created four different co-culture combinations to examine if there was any compensation on the vasodilator-vasoconstrictor levels in the SMCs in the presence of WT-ECs or an even greater imbalance when cultured with HIF2-ECs. Our findings show that when HIF2-SMCs were co-cultured with WT-ECs, a reduction of EDN1 transcript level occurred. This could be a compensative effect exerted from the WT-ECs that increases vasodilator expression in the co-culture environment. On the other hand, when HIF2-ECs were co-cultured with HIF2-SMCs, we noticed an increase in EDN1 expression, mimicking the effect of vascular stiffening. When WT-SMCs were cultured with HIF2-ECs, no significant difference was found in the expression level of EDN1. When WT-ECs or HIF2-ECs were cultured alone, their respective EDN1 secretion level is comparable to each other and in general is 100-fold higher than the EDN1 secretion level of their SMC-counterpart that are cultured alone. Upon co-culturing with SMCs, the level of EDN1 secretion is significantly lowered in all co-culture combinations. An interesting perspective is that SMCs play a crucial role in determining the EDN1 secretion, as our observations indicate that the SMC source (either WT or HIF2), but not the EC source, dictates secreted EDN1 levels, in that co-culture combinations including HIF2-SMCs always secrete higher concentration of EDN1 when compared with co-culture combinations with WT-SMCs. Altogether, our findings suggest that HIF2A mutation affects SMC functionality and interactions. Although considerations must be made in the co-culture model for factors such as absence of growth factors and low serum content in the co-culture medium, we have successfully detected changes in the vasoconstrictor and vasodilator transcript levels, suggesting a new role for SMCs in blood vessels. Thus, our results establish and validate the use of this co-culture model from future studies analyzing interaction between ECs and SMCs in different disease backgrounds.

Both HIF2A GOF-mutated patients and Hif2a knock-in mice develop vascular complications later in life. As an attempt to isolate the effect of HIF2A mutation in regulating SMC stiffness, we assessed HIF2A siRNA knockdown, Bosentan treatment, and ETA/ETB siRNA knockdown. Although various studies have shown a relationship between HIF1A and EDN1 (Chester and Yacoub, 2014; Pisarcik et al., 2013), determining the functional interactions between HIF2A and EDN1 is crucial for the pathogenesis of vascular stiffening in PH, which was induced by the accumulation of HIF2A (Kapitsinou et al., 2016a). Through HIF2A siRNA knockdown studies we found an unequivocal reduction in the gene expression of EDN1, demonstrating that EDN1 activation is dependent upon HIF2A. HIF2A siRNA knockdown also reduced the expression of cytoskeletal proteins including acetylated alpha-tubulin and SMA, shown via immunoblots. Although it is known that the HIFs regulate vascular remodeling, through our work, it is evident that HIF2A stabilization is also responsible for the activation of vasoactive substances that contribute to the onset of vascular stiffening. Cell treatment with the EDN1 receptor antagonist Bosentan was performed to test the immediate downstream effects of EDN1. It was apparent that Bosentan treatment significantly reduced the stiffness of HIF2-SMCs, as shown by the reduced overall expression of cytoskeletal proteins associated with stiffness and AFM measurements. The results demonstrated by siRNA and drug treatment clearly show that activation of EDN1 is dependent upon HIF2A induction, which then leads to the most notable characteristics of vascular stiffening in PH such as increased cellular stiffness through increased cytoskeletal tension. Our data pertaining to the stiffening of SMCs in the diseased state is further validated by the increased expression of cytoskeleton proteins and ECM deposition (Thomas et al., 2013; Lee et al., 1998). As many drugs may have non-specific effects, ETA/ETB siRNA knockdown experiments were performed to mimic the desired effects of Bosentan. As Bosentan is primarily a receptor antagonist of ETA, a 2:1 ratio of ETA:ETB was chosen. ETB siRNA was still used, as it has been shown that Bosentan binds to the receptor but with decreased efficiency. Despite following similar trends for EDN1, APLN, and MYHCII, the significant increase in ELN expression could be a result of increased ETB binding in comparison to that found in Bosentan, leading to vasodilation and anti-proliferation (Schneider et al., 2007). ELN is known to be involved in these processes (Faury et al., 1997; Wagenseil and Mecham, 2012). Overall, similar trends were observed with the siRNA treatments, reducing the possibility of our results being caused by non-specific effects of Bosentan and supporting HIF2A GOF mutations increasing SMC stiffness via the EDN1 pathway.

To further assess the impact of the HIF2A GOF mutations at the cellular level, we used HIF2A GOF mice, which have been shown to develop erythrocytosis, pulmonary hypertension, and increased right ventricular heart thickness. In our studies, we focused on young Hif2a mice to examine whether we could detect early onset of vascular complications. Indeed, 8- to 16-week-old mice had early signs of pulmonary hypertension. Isolated SMCs from the mPA of Hif2a mice were stiffer than SMCs isolated from mPA of their WT counterparts. Hif2a heterozygous mouse SMCs also exhibited more disorganized stress fibers than their WT counterparts. To determine if the effects wrought by HIF2A GOF mutations at the cellular level translate to in vivo vascular mechanical deficits, we examined vascular segments from Hif2A heterozygous mice. Our studies showed more mPA deformation in the Hif2a heterozygous mice when compared with WT mice. Closer examination of the Hif2a heterozygous mPA's indicated that there were no tissue-level differences evident from histology but Hif2a heterozygous vasculature did contain higher ELN/Col3a1 and Col1a1/Col3a1 ratios overall, suggesting cellular-level differences in ECM product ratios. Together, these findings suggest that SMC stiffening and dysfunction precede any changes to the overall mPA tissue structure in the HIF2a GOF mice.

In future studies, we will evaluate how aging further exacerbates pulmonary hypertension and drives aberrant mechanics of the PA via ECM deposition and remodeling, which can contribute to right heart failure. Although our study shows an overall increase in SMCs stiffness, future studies should look into investigating the upstream regulators of SMC stiffness on the intracellular and extracellular levels.

In summary, our study demonstrates a unique perspective that a HIF2A GOF mutation alone is sufficient to induce diseased phenotypes of SMCs. An overall increase in SMC stiffness is mainly contributed by increased F-actin stress fibers, SMMHC, and increased acetylated alpha-tubulin in HIF2-SMCs when compared with WT-SMCs. Evidence from our study indicates that increased stiffness is strongly correlated to the increase in EDN1 concentration, which is upregulated when HIF2A is stabilized in SMCs. In in vivo studies, Hif2A GOF heterozygous mice show onset of pulmonary hypertension, aberrant SMCs, and vascular mechanics compared with wild-type mice, pointing to the role that SMCs play in vascular homeostasis.

Limitations of the study

These studies clearly show that HIF2A GOF mutations lead to increased EDN1 secretion and signaling, and that increased EDN1 secretion leads to increased F-actin stress fibers and increased stiffness in SMCs. However, additional studies are needed to determine a singular molecular mechanism for how HIF2A GOF mutations lead to increased EDN1 levels. Our in vivo studies indicate Hif2a heterozygous mice have differences in mRNA levels for common ECM components and exhibit pulmonary hypertension. Nonetheless, additional studies must be performed to determine how Hif2a heterozygous mice have higher endogenous ratios of ELN/COL3a1 and Col1a1/Col3a1 but no similar measurable differences on the histological scale. Furthermore, additional studies are needed to stablish causality between different levels of ELN, Col1a1, and Col3a1 and pulmonary hypertension.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information, requests, and inquiries should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Dr. Sharon Gerecht (gerecht@jhu.edu).

Materials availability

All tables and figures are included in the text and supplemental information.

Data and code availability

The published article contains all data generated or analyzed.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying transparent methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bin Sheng Wong, Quinton Smith, and Julia Ju for helpful discussions throughout this work; Colin Maguire for helpful discussions about the new hiPSC lines; Koreana Pak for western blot analysis; Anna Coughlan, Quinton Smith, and Dong Ho Shin for help with image analyses; Chris Yankaskas and Michele Vitolo for help with the AFM measurements; Bin-Kuan Chou for assisting with iPSC generation; J.S. for genotyping familial hiPSCs; and Linda Procell for assisting with mouse surgeries, histological imaging, and quantification. This work is supported by a Fellowship from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (to E.V.), American Heart Association 20POST35180102 and National Institutes of Health (NIH) training grant 5T32HL007227 (to B.L. Lin), NRSA F32 postdoctoral fellowship F32HL128038 (to X. Y. Chan) from the NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, R01-DK104796 (to F.S. Lee), MSCRFI-2784 from Maryland Stem Cells Research Fund, and 15EIA22530000 from American Heart Association (to S.G.).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, X.Y.C., E.V., J.E., S.G.; Methodology, X.Y.C., J.E., E.V., L.S., S.G.; Investigation, X.Y.C., J.E., E.V., L.F., R.B., R.G., S.F.B.O., J.C., M.E., Formal Analysis, X.Y.C., J.E., E.V., L.F., R.B., R.G.,B.L.L., S.F.B.O., J.C., M.E., J.S.; Resources, L.C., F.S.L., J.T.P., S.G.; Writing—Original Draft, X.Y.C., J.E., E.V., S.G.; Writing—Review & Editing, X.Y.C., J.E., E.V., M.E., S.G.; L.S., J.T.P., F.S.L., and S.G.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: April 23, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102246.

Supplemental information

References

- Berkowitz D.E., White R., Li D., Minhas K.M., Cernetich A., Kim S., Burke S., Shoukas A.A., Nyhan D., Champion H.C., Hare J.M. Arginase reciprocally regulates nitric oxide synthase activity and contributes to endothelial dysfunction in aging blood vessels. Circulation. 2003;108:2000–2006. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000092948.04444.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohm F., Pernow J. The importance of endothelin-1 for vascular dysfunction in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2007;76:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacoub P., Dorent R., Nataf P., Carayon A., Riquet M., Noe E., Piette J.C., Godeau P., Gandjbakhch I. Endothelin-1 in the lungs of patients with pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res. 1997;33:196–200. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan X.Y., Black R., Dickerman K., Federico J., Levesque M., Mumm J., Gerecht S. Three-dimensional vascular network assembly from diabetic patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015;35:2677–2685. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester A.H., Yacoub M.H. The role of endothelin-1 in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Glob. Cardiol. Sci. Pract. 2014;2014:62–78. doi: 10.5339/gcsp.2014.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Z.Y., Li M., Wharton J., Zhu M.M., Zhao Y.Y. Prolyl-4 hydroxylase 2 (PHD2) deficiency in endothelial cells and hematopoietic cells induces obliterative vascular remodeling and severe pulmonary arterial hypertension in mice and humans through hypoxia-inducible factor-2 alpha. Circulation. 2016;133:2447. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash B.C., Jiang Z.X., Suh C., Qyang Y.B. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived vascular smooth muscle cells: methods and application. Biochem. J. 2015;465:185–194. doi: 10.1042/BJ20141078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergul A., Jupin D., Johnson M.H., Prisant L.M. Elevated endothelin-1 levels are associated with decreased arterial elasticity in hypertensive patients. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich) 2006;8:549–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2006.05514.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faury G., Chabaud A., Ristori M.T., Robert L., Verdetti J. Effect of age on the vasodilatory action of elastin peptides. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1997;95:31–42. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(96)01842-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furchgott R.F., Vanhoutte P.M. Endothelium-derived relaxing and contracting factors. FASEB J. 1989;3:2007–2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlow P.W., Percy M.J., Sutherland S., Bierl C., Mcmullin M.F., Master S.R., Lappin T.R., Lee F.S. Erythrocytosis-associated HIF-2alpha mutations demonstrate a critical role for residues C-terminal to the hydroxylacceptor proline. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:9050–9058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808737200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordeuk V.R., Key N.S., Prchal J.T. Re-evaluation of hematocrit as a determinant of thrombotic risk in erythrocytosis. Haematologica. 2019;104:653–658. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.210732. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglarz M., Clozel M. Mechanisms of ET-1-induced endothelial dysfunction. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2007;50:621–628. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31813c6cc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin W.G., Jr., Ratcliffe P.J. Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitsinou P.P., Rajendran G., Astleford L., Michael M., Schonfeld M.P., Fields T., Shay S., French J.L., West J., Haase V.H. The endothelial prolyl-4-hydroxylase domain 2/hypoxia-inducible factor 2 axis regulates pulmonary artery pressure in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2016;36:1584–1594. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01055-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitsinou P.P., Rajendran G., Astleford L., Schonfeld M.P., Michael M., Shay S., French J.L., West J., Haase V.H., Fields T. The endothelial Phd2/hif-2 Axis regulates pulmonary artery pressure in mice. J. Invest. Med. 2016;64:961–962. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01055-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim F.Y., Barnes E.A., Ying L., Chen C., Lee L., Alvira C.M., Cornfield D.N. Pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell endothelin-1 expression modulates the pulmonary vascular response to chronic hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2015;308:L368–L377. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00253.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuma S., Facklam A., Gerecht S. Characterizing human pluripotent-stem-cell-derived vascular cells for tissue engineering applications. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24:451–458. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuma S., Shen Y.I., Hanjaya-Putra D., Mali P., Cheng L., Gerecht S. Self-organized vascular networks from human pluripotent stem cells in a synthetic matrix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110:12601–12606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306562110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee F.S., Percy M.J. The HIF pathway and erythrocytosis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2011;6:165–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.M., Tsai K.Y., Wang N., Ingber D.E. Extracellular matrix and pulmonary hypertension: control of vascular smooth muscle cell contractility. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:H76–H82. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.1.H76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian X.J., Bao X.P., Al-Ahmad A., Liu J.L., Wu Y., Dong W.T., Dunn K.K., Shusta E.V., Palecek S.P. Efficient differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells to endothelial progenitors via small-molecule activation of WNT signaling. Stem Cell Rep. 2014;3:804–816. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majmundar A.J., Wong W.J., Simon M.C. Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:294–309. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas M. A close look at the endothelium: its role in the regulation of vasomotor tone. Eur. Urol. Supplements. 2009;8:48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pisarcik S., Maylor J., Lu W., Yun X., Undem C., Sylvester J.T., Semenza G.L., Shimoda L.A. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells by endothelin-1. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2013;304:L549. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00081.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rensen S.S., Doevendans P.A., Van Eys G.J. Regulation and characteristics of vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic diversity. Neth. Heart J. 2007;15:100–108. doi: 10.1007/BF03085963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoo A., Van Zanten J.J., Metsios G.S., Carroll D., Kitas G.D. The endothelium and its role in regulating vascular tone. Open Cardiovasc. Med. J. 2010;4:302–312. doi: 10.2174/1874192401004010302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M.P., Boesen E.I., Pollock D.M. Contrasting actions of endothelin ET(A) and ET(B) receptors in cardiovascular disease. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007;47:731–759. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehgel N.L., Zhu Y., Sun Z., Trzeciakowski J.P., Hong Z., Hunter W.C., Vatner D.E., Meininger G.A., Vatner S.F. Increased vascular smooth muscle cell stiffness: a novel mechanism for aortic stiffness in hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2013;305:H1281–H1287. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00232.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1: oxygen homeostasis and disease pathophysiology. Trends Mol. Med. 2001;7:345–350. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergueeva A.I., Miasnikova G.Y., Polyakova L.A., Nouraie M., Prchal J.T., Gordeuk V.R. Complications in children and adolescents with Chuvash polycythemia. Blood. 2015;125:414–415. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-604660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Q., Chan X.Y., Carmo A.M., Trempel M., Saunders M., Gerecht S. Compliant substratum guides endothelial commitment from human pluripotent stem cells. Sci. Adv. 2017;3:e1602883. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldner F., Jaenisch R. Medicine. iPSC disease modeling. Science. 2012;338:1155–1156. doi: 10.1126/science.1227682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Q., Kerestes H., Percy M.J., Pietrofesa R., Chen L., Khurana T.S., Christofidou-Solomidou M., Lappin T.R., Lee F.S. Erythrocytosis and pulmonary hypertension in a mouse model of human HIF2A gain of function mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:17134–17144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.444059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G., Burnham N.A., Camesano T.A., Wen Q. Measuring the mechanical properties of living cells using atomic force microscopy. J. Vis. Exp. 2013;27:50497. doi: 10.3791/50497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuder R.M., Marecki J.C., Richter A., Fijalkowska I., Flores S. Pathology of pulmonary hypertension. Clin. Chest Med. 2007;28:23–42, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo E., Hanjaya-Putra D., Zha Y., Kusuma S., Gerecht S. Smooth-muscle-like cells derived from human embryonic stem cells support and augment cord-like structures in vitro. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2010;6:237–247. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenseil J.E., Mecham R.P. Elastin in large artery stiffness and hypertension. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2012;5:264–273. doi: 10.1007/s12265-012-9349-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanjare M., Kuo F., Gerecht S. Derivation and maturation of synthetic and contractile vascular smooth muscle cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013;97:321–330. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanjare M., Kusuma S., Gerecht S. Defining differences among perivascular cells derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2014;2:561–575. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger R.H., Hoogewijs D. Regulated oxygen sensing by protein hydroxylation in renal erythropoietin-producing cells. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2010;298:F1287–F1296. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00736.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y., Li B., Li G.G., Wang R.L., Chen Z.Q., Xu L.J., Chen L., Shi H., Zhang H. Effects of endothelin-1 on the cytoskeleton protein F-actin of human trabecular meshwork cells in vitro. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2010;3:61–63. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2010.01.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The published article contains all data generated or analyzed.