Abstract

Background

Biologic disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) and Janus Kinase (JAK) inhibitors are prescribed in adult and paediatric rheumatology. Due to age-dependent changes, disease course, and pharmacokinetic processes paediatric patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases (PiRD) differ from adult rheumatology patients.

Methods

A systematic literature search for randomized clinical trials (RCTs) in PiRD treated with bDMARDs/JAK inhibitors was conducted on Medline, clinicaltrials.gov, clinicaltrialsregister.eu and conference abstracts as of July 2020. RCTs were included if (i) patients were aged ≤20 years, (ii) patients had a predefined rheumatic diagnosis and (iii) RCT reported predefined outcomes. Selected studies were excluded in case of (i) observational or single arm study or (ii) sample size ≤5 patients. Study characteristics were extracted.

Results

Out of 608 screened references, 65 references were selected, reporting 35 unique RCTs. All 35 RCTs reported efficacy while 34/35 provided safety outcomes and 16/35 provided pharmacokinetic data. The most common investigated treatments were TNF inhibitors (60%), IL-1 inhibitors (17%) and IL-6 inhibitors (9%). No RCTs with published results were identified for baricitinib, brodalumab, certolizumab pegol, guselkumab, risankizumab, rituximab, sarilumab, secukinumab, tildrakizumab, or upadacitinib. In patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) 25/35 RCTs were conducted. The remaining 10 RCTs were performed in non-JIA patients including plaque psoriasis, Kawasaki Disease, systemic lupus erythematosus and non-infectious uveitis. In JIA-RCTs, the control arm was mainly placebo and the concomitant treatments were either methotrexate, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) or corticosteroids. Non-JIA patients mostly received NSAID. There are ongoing trials investigating abatacept, adalimumab, baricitinib, brodalumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, guselkumab, infliximab, risankizumab, secukinumab, tofacitinib and tildrakizumab.

Conclusion

Despite the FDA Modernization Act and support of major paediatric rheumatology networks, such as the Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group (PRCSG) and the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization (PRINTO), which resulted in drug approval for PiRD indications, there are limited RCTs in PiRD patients. As therapy response is influenced by age-dependent changes, pharmacokinetic processes and disease course it is important to consider developmental changes in bDMARDs/JAK inhibitor use in PiRD patients. As such it is critical to collaborate and conduct international RCTs to appropriately investigate and characterize efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics of bDMARDs/JAK inhibitors in paediatric rheumatology.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12969-021-00514-4.

Keywords: Randomized controlled trials, Paediatric rheumatology, Monoclonal antibodies, Efficacy, Safety, Pharmacokinetics

Background

Paediatric inflammatory rheumatic diseases (PiRDs) are complex rare chronic inflammatory conditions with risk of chronic morbidity and mortality affecting infants, children and adolescents [1]. PiRDs include different heterogeneous disease groups, such as the juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), connective tissue diseases (CTD), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), vasculitis, uveitis and autoinflammatory diseases (AID). JIA is one of the most common PiRD groups and can be divided into different subgroups according to the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) [2, 3]. In paediatric rheumatology, (i) responsive and valid instruments to assess disease activity and (ii) standardized outcome measurements are important to achieve defined treatment aims, to avoid disease burden and to optimize patients care [4–7]. Treatment aims in PiRD patients include control of systemic inflammation, prevention of structural damage, avoidance of disease comorbidities and drug toxicities, improvement of physiological growth and development, increase of the quality of life and enabling participation in social life. To achieve these treatment goals, treat-to-target (T2T) strategies similar to those used in adult rheumatology have been implemented in PiRD management [8–10]. To reach the defined treatment targets, different levels of disease activity require different treatment selections and dose adjustments [11]. The cytokine modulating effects of biologic disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) or Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors have enabled T2T strategies, since they allow important inflammatory disease pathways to be targeted [12–15]. Over the past 15 years, bDMARDs use has become essential in paediatric rheumatology and has markedly improved clinical outcomes [13, 15–19]. However, off-label use in PiRD patients is still common [20–26].

Although some rheumatologic diseases occur in paediatric and adult patients, considerable differences in disease symptoms, disease course and disease activity might exist [27–32]. Moreover, some PiRDs are not common or well known in adulthood [33–36]. For example, the JIA associated uveitis is the most frequent and potentially the most devastating extra-articular manifestation of the JIA, commonly affecting children aged 3 to 7 years [37]. Additionally, Kawasaki Disease (KD) is an acute inflammatory febrile vasculitis of mainly medium-sized arteries that typically affects children younger than 5 years [38]. Furthermore, PiRD patients differ from adult rheumatology patients in several physiological aspects, due to age-dependent changes, maturation processes, differences in body composition and pharmacokinetic (PK) processes, such as drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion [39–45]. All these aspects are important factors to consider in diagnosis and treatment. This highlights that paediatric drug development cannot simply mimic development strategies for adults, but has to respect paediatric pathophysiology and specific paediatric disease characteristics [46]. Nevertheless, it is common to use the same bDMARDs and JAK inhibitors in paediatric and adult rheumatology, and most paediatric trials and dosing regimens are performed on the basis of existing adult data [47].

The goal of this review is to assess the current state of knowledge obtained from previously performed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in PiRD patients treated with bDMARDs and JAK inhibitors. In addition, an overview of approved bDMARDs and JAK inhibitors from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) in paediatric and adult rheumatology is provided.

Methods

Information sources and search

A systemic literature search was conducted on Medline via PubMed, the US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov), and the EU Clinical Trials Register (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu). The MeSH terms used for electronic search on PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov are detailed in the supplementary material (supplementary data S1). Similar search terms were used for the EU Clinical Trials Register. The statistical and clinical sections of the New Drug Approval (NDA) web pages of regulatory authorities in the US and Europe were reviewed for approved drugs (www.fda.gov, www.ema.europa.eu). Abstract searches were conducted after conferences, including the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), the International Society of Systemic Auto-Inflammatory Diseases (ISSAID), Société Francophone pour la Rhumatologie et les Maladies Inflammatoires en Pédiatrie (SOFREMIP) and the Pediatric Rheumatology European Society (PRES). Additionally, relevant studies were identified by manual search of the bibliographies of references retrieved from PubMed. For all literature sources, only English articles were screened.

Eligiblity and exclusion criteria

RCTs of patients aged 20 years and younger treated with predefined bDMARDs/JAK inhibitors were included if the sample size was at least five patients, and if PiRD diagnosis had been confirmed. The PiRDs included are listed in Table 1. The drugs and drug classes reviewed included the following: (i) Anti-CD20 agents: rituximab; (ii) CD80/86 inhibitors: abatacept; (iii) IL-1 inhibitors: anakinra, canakinumab, rilonacept; (iv) IL-6 inhibitors: tocilizumab, sarilumab; (v) IL-12/23 inhibitors: ustekinumab; (vi) IL-23 inhibitors: guselkumab, risankizumab, tildrakizumab; (vii) IL-17 inhibitors: secukinumab, ixekizumab, brodalumab; (viii) Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors: adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab, certolizumab pegol; (ix) BAFF inhibitors: belimumab; (x) JAK inhibitors: baricitinib, tofacitinib, upadacitinib. Studies must have at least included a relevant primary or secondary efficacy endpoint/outcome as detailed in the supplementary material (supplementary data S3). Consequently, studies were excluded if (i) the indication was not relevant, (ii) the population was not relevant, including studies which enrolled both adults and children with PiRD, (iii) the study design was not relevant including observational studies, single arm studies, reviews, meta-analyses and pooled analysis of multiple RCTs, (iv) treatment was not that as predefined, (v) the endpoint/outcome was not relevant, and/or (vi) the report was a duplicate of prior published results without any additional information.

Table 1.

Defined diagnoses of paediatric inflammatory rheumatic diseases (PiRD) for literature search

| Indication | Population |

|---|---|

| JIA | Polyarticular rheumatoid factor positive/negative JIA (PJIA) |

| Persistent or extended oligoarticular JIA (OJIA) | |

| Enthesitis-related juvenile idiopathic arthritis and juvenile ankylosing spondylitis, including sacroiliitis (ERA) | |

| Psoriatic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (PsA) | |

| Systemic JIA (SJIA) | |

| Uveitis | JIA-associated uveitis |

| Non-infectious uveitis | |

| Autoinflammatory Diseases | Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF) |

| TNF receptor-1 associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS) | |

| Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) | |

| Mevalonate Kinase Deficiency (MKD)/Hyperimmunoglobulin D syndrome (HIDS) | |

| Unclassified periodic fever syndromes | |

| Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) and Majeed syndrome | |

| Deficiency of the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (DIRA) | |

| A20 haploinsufficiency (HA20) | |

| Sideroblastic anemia with B cell immunodeficiency, periodic fevers and developmental delay syndrome (SIFD) | |

| Pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangraenosum and acne (PAPA) | |

| Deficiency of the interleukin-36 receptor antagonist (DITRA) | |

| Palmar plantar pustulosis (PPP) | |

| Pyoderma gangraenosum | |

| Interferonopathy |

Chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatitis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature (CANDLE) Stimulator of interferon genes-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy (SAVI) |

| Vasculitis | Takayasu arteritis |

| Leucocytoclastic vasculitis | |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), Wegener’s Granulomatosis | |

| Polyarteritis nodosa | |

| Microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) | |

| Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis | |

| Kawasaki Disease (KD) | |

| Behcet disease | |

| Connective Tissue Diseases | Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) |

| Juvenile Dermatomyositis (JDM) | |

| Paediatric sarcoidosis | |

| Systemic and Localized Scleroderma | |

| Sjögren Syndrome | |

| Mixed connective tissue diseases (MCTD) | |

| Macrophage activation syndrome | |

| Psoriasis |

Study selection and data collection process

Initial screening, based on retrieved abstracts, as well as the eligibility assessment based on full-text publications were performed by two independent review authors according to a review protocol (supplementary data S2). One scientist was responsible for the execution and documentation, and the other provided support as therapeutic area expert. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third independent reviewer. The primary reason for exclusion was documented for each excluded reference. Aggregate (summary) level data were extracted from each included trial by two independent review authors. The defined extracted variables for each RCTs included baseline demographic and clinical characteristics such as study design, location, patient population, sample size, age criteria, treatment and primary outcome/endpoint.

Results

Study selection

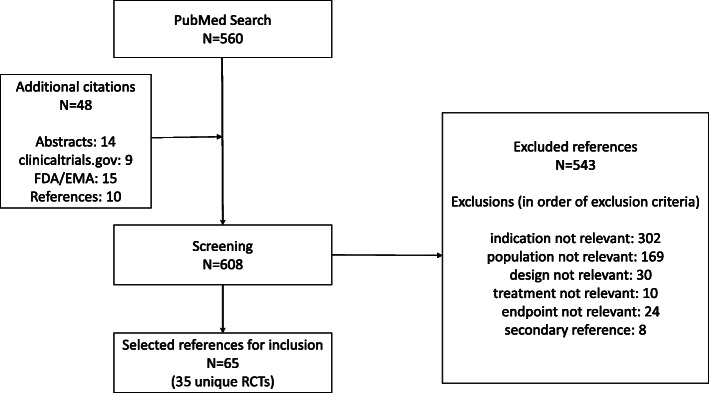

A systematic literature search was performed on July 26, 2020 using the predefined search criteria. A total of 608 references were screened, and 65 references for 35 uniquely identified RCTs performed in PiRD patients were selected for inclusion (Fig. 1). Of the references excluded, the large majority were due to irrelevant indication (56%, 302/543) or population (31%, 169/543). In total, the majority of RCTs were performed for TNF inhibitors (60%), IL-1 inhibitors (17%) and IL-6 inhibitors (9%). Only one RCT was available for the BAFF inhibitor belimumab, the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib, the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab, the IL-17 inhibitor ixekizumab, the TNF inhibitor golimumab and the CD 80/86 inhibitor abatacept. No RCTs with published results were identified for the anti-CD20 agent rituximab, the TNF inhibitor certolizumab pegol, the IL-6 inhibitor sarilumab, the IL-17 inhibitors brodalumab and secukinumab, the IL-23 inhibitors guselkumab, risankizumab and tildrakizumab and the JAK inhibitors baricitinib and upadacitinib (Table 2). Currently, there are no recruiting RCTs for sarilumab but there are two ongoing single-arm PK studies in sarilumab, NCT02776735 and NCT02991469 (data not shown). For the JAK inhibitors three Phase III RCTs are investigating baricitinib, and one Phase III global RCT is investigating tofacitinib in JIA patients (Table 3). Furthermore, there are ongoing studies for guselkumab, risankizumab, tildrakizumab, brodalumab, secukinumab and certolizumab pegol mainly in PiRD patients with psoriasis (Table 3). Additionally, some studies are recruiting to investigate adalimumab in JIA-associated uveitis, abatacept in OJIA, infliximab in KD and etanercept in OJIA and PJIA.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study selection and reasons for study exclusion after literature search

Table 2.

Overview of completed randomized controlled trials performed in paediatric rheumatology patients treated with bDMARDs/JAK inhibitors (July 2020)

| Drug Class | Drug | Studies | Arms | Patients | Indications | Populations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-CD 20 agent | rituximab | 0 | ||||

| CD80/86 inhibitor | abatacept | 1 | 2 | 190 | JIA | PJIA, SJIA (without systemic features), extended OJIA |

| IL-1 inhibitor | anakinra | 2 | 4 | 110 | JIA | PJIA, SJIA |

| canakinumab | 2 | 4 | 261 | JIA | SJIA | |

| rilonacept | 2 | 5 | 95 | JIA | SJIA | |

| IL-6 inhibitor | sarilumab | 0 | ||||

| tocilizumab | 3 | 6 | 356 | JIA | PJIA, extended OJIA, SJIA | |

| IL-12/23 inhibitor | ustekinumab | 1 | 3 | 110 | Psoriasis | Plaque psoriasis |

| IL-23 inhibitor | guselkumab | 0 | ||||

| risankizumab | 0 | |||||

| tildrakizumab | 0 | |||||

| IL-17 inhibitor | brodalumab | 0 | ||||

| ixekizumab | 1 | 3 | 201 | Psoriasis | Plaque psoriasis | |

| secukinumab | 0 | |||||

| TNF inhibitor | adalimumab | 6 | 13 | 485 | JIA, psoriasis, uveitis | ERA, JIA-associated uveitis, PJIA, plaque psoriasis |

| etanercept | 8 | 17 | 746 | JIA, psoriasis, vasculitis | PJIA, OJIA, PsA, ERA, SJIA, plaque psoriasis, KD | |

| golimumab | 1 | 2 | 154 | JIA | PJIA, SJIA (without systemic features), PsA | |

| infliximab | 6 | 13 | 576 | JIA, uveitis, vasculitis | PJIA, non-infectious uveitis, KD | |

| certolizumab pegol | 0 | |||||

| BAFF inhibitor | belimumab | 1 | 2 | 93 | CTD | SLE |

| JAK inhibitor | tofacitinib | 1 | 2 | 225 | JIA | ERA, PJIA, PsA |

| baricitinib | 0 | |||||

| upadacitinib | 0 |

Abbreviations: IL interleukin, TNF tumour necrosis factor, JAK Janus Kinase, JIA juvenile idiopathic arthritis, CTD connective tissue disease, PJIA polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, KD Kawasaki disease, SJIA systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, OJIA oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ERA enthesitis-related juvenile idiopathic arthritis, PsA psoriatic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus

Table 3.

Ongoing or recruiting studies in paediatric patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases (July 2020)

| Drug class | Drug | Study | Sponsor | Population | Region | Study duration | Primary outcome/endpoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD 80/86 inhibitor | abatacept | Limit-JIA, NCT03841357 | Duke University | OJIA | United States | 10/2019–12/2022 | Joint count, active anterior uveitis |

| IL-23 inhibitor | guselkumab | aPROTOSTAR, NCT03451851 | Janssen | Paediatric psoriasis | global | 7/2018–6/2025 | PASI75, PGA ≤1 |

| risankizumab | bM19–977, NCT04435600 | Abbvie | Paediatric psoriasis | United States | 7/2020–06/2025 | PASI75; PGA ≤ 1 | |

| tildrakizumab | TILD-19-12, NCT03997786 | Sun Pharma Global FZE | Paediatric psoriasis | United States | 1/2020–11/2023 | PASI75, PGA ≤1 | |

| IL-17 inhibitor | brodalumab | cEMBRACE 1, NCT04305327 | LEO Pharma | Paediatric psoriasis | global | 9/2020–11/2023 | PASI75 |

| secukinumab | dCAIN457F2304, NCT03031782 | Novartis | PsA, ERA | global | 5/2017–12/2020 | Disease flare | |

| eCAIN457A2311, NCT03668613 | Novartis | Paediatric psoriasis | global | 8/2018–9/2023 | PASI75, PGA ≤1 | ||

| fCAIN457A2310, NCT02471144 | Novartis | Paediatric psoriasis | global | 9/2015–7/2023 | PASI75, PGA ≤1 | ||

| TNF inhibitor | adalimumab | gADJUST, NCT03816397 | UCSF | JIA-associated uveitis | United States | 12/2019–12/2022 | Treatment failure |

| etanercept | STARS, EudraCT 2018–001931-27 | IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini | OJIA, PJIA | Italy | NA | Clinical inactive disease | |

| infliximab | KIDCARE, NCT03065244 | UCSD | Kawasaki disease | United States | 2/2017–9/2020 | Fever | |

| certolizumab pegol | CIMcare, NCT04123795 | UCB Biopharma | Paediatric psoriasis | North America | 1/2020–4/2023 | PASI75, PGA ≤1 | |

| JAK inhibitor | baricitinib | hJUVE-BRIGHT, NCT04088409 | Eli Lilly | JIA-associated uveitis | Europe | 10/2019–7/2022 | Uveitis disease response |

| iJUVE-BALM, NCT04088396 | Eli Lilly | SJIA | global | 2/2020–4/2023 | Disease flare | ||

| jJUVE-BASIS, NCT03773978 | Eli Lilly | PJIA, extended OJIA, ERA, PsA | global | 12/2018–8/2021 | Disease flare | ||

| tofacitinib | A3921165, NCT03000439 | Pfizer | SJIA | global | 5/2018–8/2023 | Disease flare |

Abbreviations: IL interleukin, TNF tumour necrosis factor, JAK Janus Kinase, ERA enthesitis-related juvenile idiopathic arthritis, JIA juvenile idiopathic arthritis, PsA, psoriatic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, OJIA oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, PASI psoriasis area and severity index, PGA Physician global assessment, PJIA polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, SJIA systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, NA not applicable

aAlso registered under EudraCT 2017–003053-42; bAlso registered under EudraCT 2019–004141-32, cAlso registered under EudraCT 2019–001868-30; dAlso registered under EudraCT 2016–003761-26; eAlso registered under EudraCT 2017–004515-39; fAlso registered under EudraCT 2014–005663-32; gAlso registered under EudraCT 2019–000412-29; hAlso registered under EudraCT 2019–00119-10; iAlso registered under EudraCT 2017–004495-60; jAlso registered under EudraCT 2017–004518-24

Study characteristics

Approximately two-thirds (25 out of 35) of the identified RCTs were conducted in JIA patients and the remaining ten RCTs were performed in non-JIA patients, including KD, plaque psoriasis, SLE, and non-infectious uveitis (Tables 4 and 5). The mean/median age of children enrolled in the JIA RCTs ranged from 8 years to 15.3 years. In contrast, the non-JIA patients included in RCTs had a mean/median age range varying between 2.2 and 15.2 years, with KD patients being younger (range 2.2 to 3.7 years). In JIA RCTs, the control was mainly placebo, and the concomitant background treatments were usually either methotrexate, NSAID or corticosteroids, whereas in non-JIA trials the control arm was a mixture of placebo or standard of care treatments and patients received mostly NSAID as background treatments (data not shown for the control arm). The primary efficacy outcome/endpoint in the JIA RCTs was mainly ACR Pedi 30/modified ACR Pedi 30 or disease flare (Table 4). Other instruments to assess the primary outcome were count of joints with active arthritis, the assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society 40% score (ASAS 40), inactive disease, treatment failure and improvement of laser flare photometry (Table 4). In non-JIA patients, efficacy outcomes/endpoints varied due to heterogeneous subgroups. The primary efficacy outcome/endpoint of RCTs in KD was mainly related to fever, whereas for plaque psoriasis the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75), or the Physician Global Assessment (PGA) was used (Table 5). The RCT addressing SLE used the SLR response index (SRI 4), whereas the primary outcome/endpoint in non-infectious uveitis was assessed with uveitis disease activity using the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) criteria, AC cells and vitreous haze. The majority of the JIA RCTs were global studies or otherwise conducted in either Europe or the United States, with one study (NCT00144599) located in Japan (data not shown). The non-JIA RCTs took place either in North America, Europe or globally (data not shown). In particular, KD RCTs took place mainly in Asia or the United States. Details for JIA and non-JIA RCTs are shown in Tables 4 and 5. All non-JIA studies were of a parallel study design, while in JIA studies there was a mixture of parallel and withdrawal study designs (Tables 4 and 5). The main conclusion of the majority of the studies (in terms of meeting the primary endpoint/outcome) was that the bDMARDs evaluated were more effective in comparison to placebo or standard of care (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4.

Overview and general characteristics of identified reviewed randomized controlled trials performed in JIA patients (July 2020)

| Drug class | Drug | Dose | Study (phase) | Study timec | Population | N | Age criteria | Agea | Background | Primary outcome/endpoint | Main conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD80/86 inhibitor | abatacept | 10 mg/kg q4w |

dIM101–033, NCT00095173 |

26 | PJIA, SJIA (without systemic features), extended OJIA | 190 | 6 to 17 | 12.4 | MTX, corticosteroids | Disease flare | Effective |

| IL-1 inhibitor | anakinra | 1 mg/kg/d | e,b990758–990779, NCT00037648 (II) [52, 53] | 16 | PJIA | 86 | 2 to 17 | 12 | MTX | Safety | Efficacy is inconclusive |

| 2 mg/kg/d |

ANAJIS, NCT00339157 |

4.33 | SJIA | 24 | 2 to 20 | 8.5 | NSAID, corticosteroids | Modified ACR Pedi 30 | Effective | ||

| canakinumab | 4 mg/kg single dose | fβ-SPECIFIC 1, NCT00886769 (III) [55–57] | 4.33 | SJIA | 84 | 2 to 19 | 8a | MTX, NSAID, corticosteroids | ACR Pedi 30 | Effective | |

| 4 mg/kg q4w | gβ-SPECIFIC 2, NCT00889863 (III) [55–57]b | 120 | SJIA | 177 | 2 to 19 | 8a | MTX, NSAID, corticosteroids | Disease flare | Effective | ||

| rilonacept | 2.2 mg/kg qw |

RAPPORT, NCT00534495 |

24 | SJIA | 71 | 1 to 19 | 10 | NA | Modified ACR Pedi 30 | Effective | |

| 2.2 mg/kg qw, 4.4 mg/kg qw |

IL1T-AI-0504, NCT01803321 (II) [60] |

104 | SJIA | 24 | 4 to 20 | 12.6 | MTX, NSAID, corticosteroids | ACR Pedi 30 | Not effective | ||

| IL-6 inhibitor | tocilizumab | 8 mg/kg q4w, 10 mg/kg q4w |

hCHERISH, NCT00988221 |

104 | PJIA, extended OJIA | 188 | 2 to 17 | 11 | MTX, corticosteroids | Disease flare | Effective |

| 8 mg/kg q2w, 12 mg/kg q2w |

iTENDER, NCT00642460 |

260 | SJIA | 112 | 2 to 17 | 9.7 | MTX, corticosteroids | Modified ACR Pedi 30 | Effective | ||

| 8 mg/kg q2w |

MRA316JP, NCT00144599 (III) [68]b |

18 | SJIA | 56 | 2 to 19 | 8.3 | corticosteroids | ACR Pedi 30 | Effective | ||

| TNF inhibitor | adalimumab | 24 mg/m2 q2w |

jM11–328, NCT01166282 |

12 | ERA | 46 | 6 to 17 | 12.9 | MTX or SSZ, NSAID | Joints with active arthritis | Effective |

| 40 mg q2w | Horneff 2012, EudraCT 2007–003358-27(III) [72] | 12 | ERA | 32 | 12 to 17 | 15.3 | NSAID, corticosteroids | ASAS40 | Effective | ||

| 24 mg/m2 q2w |

k,bDE038, NCT00048542 |

48 | PJIA | 171 | 4 to 17 | 11.2 | MTX, NSAID, corticosteroids | Disease flare | Effective | ||

| 20 mg q2w, 40 mg q2w | SYCAMORE, EudraCT 2010–021141-41 (NA) [75, 76] | 78 | JIA-associated uveitis | 90 | 2 to 18 | 8.9 | MTX | Treatment failure | Effective | ||

| 24 mg/m2 q2w, 40 mg q2w | lADJUVITE, NCT01385826 (II/III) [77] | 52 | JIA-associated uveitis | 32 | > = 4 | 9.5a | MTX, corticosteroids (oral and topical) | LFP improvement > = 30% and no worsening on slit lamp | Effective | ||

| etanercept | 0.8 mg/kg/qw | Horneff 2015, EudraCT 2010–020423-51 (III) [78] b | 48 | ERA | 38 | 6 to 17 | 13.3 | SSZ, NSAID, corticosteroids | Disease flare | Effective | |

| 0.8 mg/kg/qw | o16.0016 (NA) [79, 80] | 30.33 | PJIA | 69 | 4 to 17 | NA | NSAID, corticosteroids | Disease flare | Effective | ||

| 0.8 mg/kg/qw | o20021616, NCT03780959 (II/III) [81]b | 30.33 | PJIA | 69 | 4 to 18 | 10.5 | NSAID | Disease flare | Effective | ||

| 0.8 mg/kg/qw |

20021628, NCT03781375 (III) [82] |

52 | PJIA | 25 | NA | 10.1 | MTX | ACR Pedi 30 | NA | ||

| 0.8 mg/kg/qw |

TREAT, NCT00443430 |

52 | PJIA | 85 | 2 to 17 | 10.5 | MTX | Clinical inactive disease | Not effective | ||

| 0.8 mg/kg/qw, 1.6 mg/kg/qw |

b20021631, NCT00078806 (III) [85] |

39 | SJIA | 19 | 2 to 18 | 9.1 | MTX, NSAID, corticosteroids | Disease flare | NA | ||

| 0.8 mg/kg/qw | BeSt for Kids, NTR1574 (NA) [86, 87] | 12 | PJIA,RF−; OJIA, JPsA | 94 | 2 to 16 | 8.8a | MTX | Unclear | Effective | ||

| golimumab | 30 mg/m2 q4w | mGO KIDS, NCT01230827 (III) [88, 89]b | 48 | PJIA, SJIA (without systemic features), PsA | 154 | 2 to 17 | 11.1 | MTX, corticosteroids | Disease flare | Not effective | |

| infliximab |

3 mg/kg, 6 mg/kg |

CR004774, NCT00036374 (III) [90] | 58 | PJIA | 122 | 4 to 17 | 11.2 | MTX, NSAID, corticosteroids | ACR Pedi 30 | Not effective | |

| 3–5 mg/kg | ACUTE-JIA, NCT01015547 (III) [91] | 54 | PJIA | 60 | 4 to 15 | 9.6 |

MTX, other DMARDs |

ACR Pedi 75 | Effective | ||

| JAK inhibitor | tofacitinib | 2–5 mg BID | nA3921104, NCT02592434 (III) [92]b | 44 | ERA, PJIA, PsA | 225 | 2 to 17 | 13a | NA | Disease flare | Effective |

Abbreviations: Drug class: IL interleukin, TNF tumour necrosis factor, JAK Janus Kinase; Dose: mg milligram, kg kilogram, d per day, qw once per week, q2w once per every 2 weeks, q4w once per every 4 weeks, BID twice a day; Population: ERA enthesitis-related juvenile idiopathic arthritis, PsA psoriatic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, OJIA oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, PJIA juvenile Polyarticular idiopathic arthritis, RF− rheumatoid factor negative, SJIA systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis; Background: MTX methotrexate, HCQ hydroxycloroquine, NSAID non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, DMARDS disease modifying antirheumatic drugs, SSZ sulfasalazine; Outcome: ACR Pedi 30 ACR Pedi 30% response criteria, ACR Pedi 75 ACR Pedi 75% response criteria, LFP laser flare photometry, ASAS40 assessment in ankylosing spondylitis response criteria 40%; NA not available

amedian age, otherwise mean age across all arms of the study, bwithdrawal study design instead of parallel, cduration in weeks, dAlso registered under EudraCT 2005–000443-28; eAlso registered under EudraCT 2015–002466-22; fAlso registered under EudraCT 2008–005476-27; gAlso registered under EudraCT 2008–005479-82; hAlso registered under EudraCT 2009–011593-15; iAlso registered under EudraCT 2007–00872-18; jAlso registered under EudraCT 2009–017938-46; kAlso registered under EudraCT 2011–001661-40; lAlso registered under EudraCT 2010–019441-26; mAlso registered under EudraCT 2009–015019-42; nAlso registered under EudraCT 2015–001438-46; osame study

Table 5.

Overview and general characteristics of identified reviewed randomized controlled trials performed in non-JIA patients (July 2020)

| Drug class | Drug | Dose | Study (phase) | Studytimec | Population | N | Age criteria | Agea | Primary outcome/endpoint | Main conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-12/23 inhibitor | ustekinumab | 0.75 mg/kg, 22.5/45/ 90 mg |

dCADMUS, NCT01090427 (III) [93]b |

60 | Plaque psoriasis | 110 | 12 to 17 | 15.2 | PGA ≤1 | Effective |

| IL-17 inhibitor | ixekizumab |

20 mg BW < 25 kg q4w, 40 mg BW 25–50 kg q4w, 80 mg BW > 50 kg q4w |

eIXORA-PEDS, NCT03073200 (III) [94] b | 12 | Plaque psoriasis | 201 | 6 to 17 | 13.5 | PASI75, PGA ≤1 | Effective |

| TNF inhibitor | adalimumab |

0.4 mg/kg q2w, 0.8 mg/kg q2w |

fM04–717, NCT01251614 |

52 | Plaque psoriasis | 114 | 4 to 17 | 13 | PASI75, PGA ≤1 | Effective |

| etanercept | 0.8 mg/kg/qw |

EATAK, NCT00841789 (II) [99] b |

6 | KD | 205 | 0 to 18 | 3.7 | Fever | Not effective | |

| 0.8 mg/kg/qw |

20030211, NCT00078819 |

48 | Plaque psoriasis | 211 | 4 to 17 | 13a | PASI75 | Effective | ||

| infliximab | 5 mg/kg single dose | Han 2018 (NA) [105] b | 0.571 | KD | 154 | 0 to 4 | 2.2a | Unclear | Effective | |

| 5 mg/kg single dose |

TA-650-22, NCT01596335 (III) [106] b |

8 | KD | 31 | 1 to 10 | 3a | Defervescence | Effective | ||

| 5 mg/kg single dose | Tremoulet 2014, NCT00760435 (III) [107, 108] b | 5 | KD | 196 | 0 to 17 | 3a | Fever | Effective | ||

| 5 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg q4w | Pro00000057, NCT00589628 (IV) [109] b | 39 | Non-infectious uveitis | 13 | 4 to 18 | NA | Uveitis disease activity | NA | ||

| BAFF inhibitor | belimumab | 10 mg/kg qm |

gPLUTO, NCT01649765 |

52 | SLE | 93 | 5 to 17 | 14 | SRI4 | Effective |

Abbreviations: Drug class: IL interleukin, TNF tumour necrosis factor; Dose: mg milligram, kg kilogram, qw once per week, q2w once per every 2 weeks, q4w once per every 4 weeks, qm once every month; Population: KD Kawasaki disease, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus; Outcome: PASI psoriasis area and severity index, PGA Physician global assessment, SRI4 systemic lupus erythematosus response index 4, NA not available

amedian age, otherwise mean age across all arms of the study, bparallel study design, cduration in weeks; dAlso registered under EudraCT 2009–014368-20, eAlso registered under EudraCT 2016–003331-38;fAlso registered under EudraCT 2009–013072-52; gAlso registered under EudraCT 2011–000368-88

Approved bDMARDs and JAK inhibitors in paediatric and adult rheumatology

In March 2020, the FDA has approved all 23 reviewed drugs, including bDMARDs and JAK inhibitors for adult rheumatology, whereas the EMA has approved 22 (Table 6). For PiRD patients, 10 bDMARDs (EMA) and 11 (FDA) have been approved (Table 6). Not surprisingly, the more recently approved bDMARDs in adult rheumatology and the JAK inhibitors have mostly not yet been approved for PiRD patients. Infliximab is approved for several rheumatologic indications in adulthood including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), PsA, ankylosing spondylitis, and plaque psoriasis, but is not approved for any PiRD indication so far. In paediatrics, infliximab is still restricted for in-label use in paediatric chronic inflammatory bowel diseases. Furthermore, there are some differences between the FDA and EMA in bDMARDs and JAK approvals. For example, the FDA has approved rilonacept for the treatment of the Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS) in adults and children aged 12 years and older, whereas EMA has not. Particularly relevant for the PiRD patients are the different age limitations for different bDMARDs, and varying age restriction for different PiRD diagnoses. No bDMARDs are approved in children younger than 2 years with the exception of anakinra, which is approved by the EMA for the age ≥ 8 months. The age limitations have changed over the last couple of years, and today the common age categories are ≥2, ≥4, ≥6, or ≥ 12 years. A detailed overview about paediatric bDMARDs approvals, indications and age limitations by the EMA and FDA in March 2020 compared with adult rheumatology is given in Table 6.

Table 6.

Overview of bDMARDs and JAK inhibitors approved in adult and paediatric rheumatology (March 2020)

| Drug class | Drug (brand name) |

Adults | Children | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approved by FDA (date) | Approved by EMA (date) | Approved by FDA (date) | Current FDA age criteria | Approved by EMA (date) | Current EMA age criteria | ||

| Anti-CD20 agent | rituximaba (MabThera, Rituxan) | RA (2006), WG/MPA (2011) | RA(2006), GPA/MPA (2013) | GPA/MPA (2019) | ≥2 years | GPA/MPA (2020) | ≥2 years |

| CD80/86 inhibitor | abatacept (Orencia) | RA (2005), PsA (2017) | RA (2007), PsA (2017) | PJIA (2008) |

≥2 years (sc); ≥6 years (iv) |

PJIA (2009) | ≥2 years |

| IL-1 inhibitor | anakinra (Kineret) |

RA (2001) CINCA/NOMID (2012) |

RA (2002), CAPS (2013), AOSD (2018) | NOMID/CINCA (2012) | NA | CAPS (2013), SJIA (2018) | ≥8 months |

| canakinumab (Ilaris) | CAPS (2009), TRAPS/MKD/FMF (2016) | CAPS (2009), AOSD (2016), TRAPS/FMF/MKD (2016) |

CAPS (2009), SJIA (2013), TRAPS/ FMF/MKD (2016) |

≥4 years CAPS/TRAPS/MKD/ FMF; ≥2 years SJIA |

CAPS (2009), SJIA (2013), TRAPS/FMF/ MKD (2016) | ≥2 years | |

| rilonacept (Arcalyst) | CAPS (2008) | not approved | CAPS (2008) | ≥12 years | not approved | ||

| IL-6 inhibitor |

tocilizumabb (RoAcetemra/Actemra) |

RA (2010) | RA (2008) | SJIA (2011), PJIA (2013) | ≥2 years | SJIA (2011), PJIA (2013) |

≥1 years SJIA; ≥2 years PJIA |

| sarilumab (Kevzara) | RA (2017) | RA (2017) | not approved | not approved | |||

| IL-12/23 inhibitor | ustekinumabc (Stelara) | Plaque psoriasis (2009), PsA (2013) |

Plaque psoriasis (2008), PsA (2014) |

Plaque psoriasis (2017) | ≥12 years | Plaque psoriasis (2015) | ≥6 years |

| IL-23 inhibitor | guselkumab (Tremfya) | Plaque psoriasis (2017) | Plaque psoriasis (2017) | not approved | not approved | ||

| risankizumab (Skyrizi) | Plaque psoriasis (2019) | Plaque psoriasis (2019) | not approved | not approved | |||

| tildrakizumab (Ilumya/Ilumetri) | Plaque psoriasis (2018) | Plaque psoriasis (2018) | not approved | not approved | |||

| IL-17 inhibitor | brodalumab (Siliq, Kyntheum) | Plaque psoriasis (2017) | Plaque psoriasis (2017) | not approved | not approved | ||

| ixekizumab (Taltz) | Plaque psoriasis (2016), PsA (2017), AS (2019) | Plaque psoriasis (2016), PsA (2017) | Plaque psoriasis (2020) | ≥6 years | not approved | ||

| secukinumab (Cosentyx) |

Plaque psoriasis (2015), AS (2016), PsA (2016) |

Plaque psoriasis (2014), PsA (2015), AS (2015) |

not approved | not approved | |||

| TNF inhibitor | adalimumabd (Humira) | RA (2002), PsA (2005), AS (2006), plaque psoriasis (2008), non-infectious intermediate, posterior and panuveitis (2016) | RA (2003), PsA (2005), AS (2006), plaque psoriasis (2007), non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (2012), non-infectious intermediate, posterior and panuveitis (2016) | PJIA (2008) | ≥2 years | PJIA (2008), ERA (2014), plaque psoriasis (2015), non-infectious anterior uveitis (2017) |

≥2 years PJIA; ≥2 years uveitis; ≥4 years plaque psoriasis; ≥6 years ERA |

| certolizumab pegole (Cimzia) | RA (2009), PsA (2013), AS (2013), plaque psoriasis (2018), non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (2019) | RA (2009), PsA (2013), AS/non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (2013), plaque psoriasis (2018) | not approved | not approved | |||

| etanercept (Enbrel) | RA (1998), PsA (2002), AS (2003), plaque psoriasis (2004) | RA (2000), PsA (2002), AS (2004), plaque psoriasis (2004), non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (2014) | PJIA (1999), plaque psoriasis (2016) | ≥2 years PJIA; ≥4 years plaque psoriasis | PJIA (2001), plaque psoriasis (2008), ERA/PsA (2012) |

≥2 years PJIA; ≥6 years plaque psoriasis; ≥12 years ERA/PsA |

|

| golimumabf (Simponi) | RA/PsA/AS (2009) | RA/PsA/AS (2009), non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (2015) | not approved | PJIA (2016) | ≥2 years | ||

| infliximabg (Remicade) | RA (1999), AS (2004), PsA (2005), plaque psoriasis (2006) | RA (2000), AS (2003), PsA (2004), plaque psoriasis (2005) | not approved | not approved | |||

| BAFF inhibitor | belimumab (Benlysta) | SLE (2011) | SLE (2011) | SLE (2019) | ≥5 years | SLE (2019) | ≥5 years |

| JAK inhibitor | tofacitinib8 (Xeljanz) | RA (2012), PsA (2017) | RA (2017), PsA (2018) | not approved | not approved | ||

| baricitinib (Olumiant) | RA (2018) | RA (2016) | not approved | not approved | |||

| upadacitinib (Rinvoq) | RA (2019) | RA (2019) | not approved | not approved | |||

aAlso approved to treat Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, chronic lymphatic leukemia and pemphigus vulgaris; bAlso approved to treat giant cell arteritis, cytokine release syndrome (≥2 years); cAlso approved to treat ulcerative colitis (FDA only), Crohn’s disease; dAlso approved to treat ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease (≥6 years), hidradenitis suppurativa (age ≥ 12 years); eAlso approved to treat Crohn’s disease (FDA only); fAlso approved to treat ulcerative colitis; gAlso approved to treat Crohn’s disease (≥6 years), ulcerative colitis (≥6 years); hAlso approved to treat ulcerative colitis (FDA only)

Abbreviations: AOSD adult-onset still’s disease, AS ankylosing spondyloarthritis/spondylitis, CAPS cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome, CINCA chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, and arthritis, EMA European Medicines Agency, ERA enthesitis-related juvenile idiopathic arthritis, FDA Food and Drug Administration, FMF familial mediterranean fever, GPA granulomatosis with polyangiitis, IL interleukin, MKD mevalonate kinase deficiency, MPA microscopic polyangiitis, NA. not applicable, NOMID neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease, PJIA polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, PsA psoriatic arthritis/ psoriatic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, RA rheumatoid arthritis, SJIA systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus, TNF tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome, TRAPS tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome, WG Wegner’s Granulomatosis

Discussion

This review indicates that reported data from RCTs characterizing efficacy, safety and/or PK, remains limited for several prescribed bDMARDs and JAK inhibitors in PiRD patients. As RCTs are robust research methods to determine cause-effect relationships between intervention and outcome, they are important to generate evidence in basic, translational and clinical research and can improve management of patients [112]. In the past, several clinical trials were conducted in PiRD with support of research networks in paediatric rheumatology, such as the Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group (PRCSG) and the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO) resulting in bDMARDs approval for some PiRD indications [19, 113]. This review indicates that TNF inhibitors are the most studied bDMARDs in PiRD patients, particularly in the JIA group. JIA is one of the most commonly diagnosed PiRDs with a prevalence of 16/100,000 to 150/100,000 [3]. In several JIA sub-groups, treatment with TNF inhibition is recommended, particularly when conventional disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (cDMARDs) cannot achieve the defined target [114, 115]. One of the first FDA-approved TNF inhibitors for polyarticular JIA treatment was etanercept in 1999, followed by adalimumab in 2008. This might explain why a majority of RCTs were performed for etanercept. Up to now, no JAK inhibitor is approved for PiRD patients. JAK inhibitors can be administered orally and therefore this treatment approach might be of particular interest in paediatric rheumatology, explaining why several RCTs are currently performed for JAK inhibitors. For several bDMARDs, a latency in drug approval for PiRD patients can be observed with a delay ranging between 1 year to 9 years. However, around 50% of reviewed therapeutic drugs are currently not approved for PiRD patients. Off-label and unlicensed drug use is frequent in paediatric patient populations [116, 117] and a considerable number of PiRD patients has to be treated with off-label bDMARDs or JAK inhibitors as no approved drugs are available for their age group, the PiRD indication or in general [20–23, 25]. Off-label use is often of great concern to the families of the affected children [17]. In addition, it seems that off-label and unlicensed drug use in children is associated with increased risk of medication errors and adverse events [118–120]. As infants and children with PiRD differ greatly from adult rheumatology patients the lack of paediatric PK data for bDMARDs and JAK inhibitors, can result in over- and under-dosing [42, 47, 121]. While under-dosing/low drug concentrations can result in drug-antibodies and drug insufficiency with uncontrolled chronic inflammation and disease burden, over-dosing can be associated with serious short- and long-term safety events [122–124]. There are data suggesting that based on the body weight, the clearance of several drugs is higher in paediatrics than in adults [39]. In PiRD patients, particularly in infants and younger children, there are data for bDMARDs and JAKs indicating a need for more frequent drug administration due to shorter half-life or the need for higher weight based drug dosages to achieve the defined therapy target [121, 125–127]. Moreover, it seems that subcutaneously administered bDMARDs are absorbed faster in young children [44]. As the therapy outcomes in PiRD patients is influenced by these age-dependent PK processes and the disease course, it is crucial to understand the developmental changes to optimize bDMARDs and JAK inhibitor dosing in paediatric rheumatology [39–42, 44, 46, 47]. As a consequence, the FDA Modernization Act stimulates the conduct of dedicated clinical studies to enhance understanding of PK, efficacy-safety balance, and optimal dosing of drugs in paediatric patients [128]. Nevertheless, concern has been raised that trial discontinuation, and nonpublication with associated risk of publication bias, seems to be common in paediatric patients [129, 130]. Slow recruitment rates in rare paediatric diseases can be challenging for paediatric trials, and poor recruitment seems to be one of the major risks for early termination or discontinuation of such studies [130]. These observations highlight the value of established research networks in paediatric rheumatology, such as PRCSG and PRINTO, in conducting clinical studies in PiRD patients as efficacy, safety and PK data obtained from PiRD patients to optimize treatment are warranted.

This review has several limitations. Despite a comprehensive search strategy and independent reviewer processes, there might be a risk of a reporting bias as unpublished RCTs were not included. Furthermore, this review does not include observational studies, single arm studies or RCTs including both children and adults. We cannot rule out that not all conducted RCTs in PiRDs were identified, despite a rigorous screening and review process. We have included RCTs with patients aged 20 years and younger, although this upper age limit of 20 years constituted the risk of having studies performed mainly in adolescents and young adults. To address this bias we have reported for each analysed RCT the age criteria and the median/mean age. As several included RCTs had an upper age criteria between 17 to 20 years, we would have missed otherwise these studies if we have limited the search to the age criteria 16 or 18 years.

Conclusion

In summary, paediatric rheumatology patients differ from adult rheumatology patients in many aspects. As therapeutic drug response is influenced by age-dependent PK processes and disease course, it is important to consider developmental changes when prescribing bDMARDs or JAK inhibitors in PiRD patients. As such, it is critical to conduct international multicentre studies in PiRD patients to enroll a sufficiently high patient number in a reasonable period of time with the goal to appropriately investigate and characterize PK, efficacy and safety for bDMARDs and JAK inhibitors. More efficacy and safety data, ideally combined with PK data from PiRD patients will optimize bDMARDs and JAK inhibitor use in paediatric rheumatology.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary data S1. Search terms. Supplementary data S2. Review protocol. Supplemetary data S3. Outcome/Endpoint inclusion criteria for literature search.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Andrew Atkinson for his valuable inputs.

Abbreviations

- AID

Autoinflammatory diseases

- cDMARDS

conventional disease modifying antirheumatic drugs

- bDMARDS

Biologic disease modifying antirheumatic drugs

- CTD

Connective tissue diseases

- EMA

European Medicines Agency

- ERA

Enthesitis-related juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- ILAR

International League of Associations for Rheumatology

- IL

Interleukin

- JAK

Janus kinase

- JIA

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- KD

Kawasaki disease

- NSAID

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- OJIA

Oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- PiRD

Pediatric inflammatory rheumatic diseases

- PJIA

Polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- PK

Pharmacokinetics

- PsA

Psoriatic juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

- RF

Rheumatoid factor

- RCT

Randomized controlled trials

- SJIA

Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- SLE

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- TNF

Tumour necrosis factor

- T2T

Treat to target

Authors’ contributions

TW, CW, NZ, AW and MP have contributed to the design, data gathering and analysis. TW and CW performed the initial data screening and eligibility assessment. CW was responsible for the execution and documentation and TW provided support as therapeutic area expert. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third independent reviewer (MP). All authors (TW, CW, NZ, AW, MP) have contributed in preparation of the submitted manuscript. They were involved in drafting the work and critically revising. All authors have approved this version to be published and they agreed to be accountable for all aspects in the work in ensuring questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors have agreed to the submission of this manuscript to Rheumatology.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

not applicable.

Consent for publication

not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors have nothing to declare.

Footnotes

This article has been updated to rectify several values and in-text errors, full details are available in the correction article.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

8/16/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1186/s12969-021-00593-3

References

- 1.Teague M. Pediatric rheumatologic diseases: a review for primary care NPs. Nurse Pract. 2017;42(9):43–47. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000520831.76287.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, Baum J, Glass DN, Goldenberg J, et al. International league of associations for rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):390–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007;369(9563):767–778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruperto N, Martini A. International research networks in pediatric rheumatology: the PRINTO perspective. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(5):566–570. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000130286.54383.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruperto N, Ravelli A, Falcini F, Lepore L, Buoncompagni A, Gerloni V, et al. Responsiveness of outcome measures in juvenile chronic arthritis. Italian Pediatric Rheumatology Study Group. Rheumatology. 1999;38(2):176–180. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Consolaro A, Giancane G, Schiappapietra B, Davi S, Calandra S, Lanni S, et al. Clinical outcome measures in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2016;14(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s12969-016-0085-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Consolaro A, Ruperto N, Bazso A, Pistorio A, Magni-Manzoni S, Filocamo G, et al. Development and validation of a composite disease activity score for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(5):658–666. doi: 10.1002/art.24516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravelli A, Consolaro A, Horneff G, Laxer RM, Lovell DJ, Wulffraat NM, et al. Treating juvenile idiopathic arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(6):819–828. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinze CH, Oommen PT, Dressler F, Urban A, Weller-Heinemann F, Speth F, et al. Development of practice and consensus-based strategies including a treat-to-target approach for the management of moderate and severe juvenile dermatomyositis in Germany and Austria. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2018;16(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s12969-018-0257-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansmann S, Lainka E, Horneff G, Holzinger D, Rieber N, Jansson AF, et al. Consensus protocols for the diagnosis and management of the hereditary autoinflammatory syndromes CAPS, TRAPS and MKD/HIDS: a German PRO-KIND initiative. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2020;18(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s12969-020-0409-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smolen JS. Treat-to-target: rationale and strategies. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30(4 Suppl 73):S2–S6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCoy SS, Stannard J, Kahlenberg JM. Targeting the inflammasome in rheumatic diseases. Transl Res. 2016;167(1):125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruperto N, Martini A. Current and future perspectives in the management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(5):360–370. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maggi L, Mazzoni A, Cimaz R, Liotta F, Annunziato F, Cosmi L. Th17 and Th1 lymphocytes in Oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:450. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jesus AA, Goldbach-Mansky R. IL-1 blockade in autoinflammatory syndromes. Annu Rev Med. 2014;65:223–244. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-061512-150641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanoni F, Minoia F, Malattia C. Biologics in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a narrative review. Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176(9):1147–1153. doi: 10.1007/s00431-017-2960-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sterba Y, Ilowite N. Biologics in pediatric rheumatology: quo Vadis? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2016;18(7):45. doi: 10.1007/s11926-016-0593-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garg S, Wynne K, Omoyinmi E, Eleftheriou D, Brogan P. Efficacy and safety of anakinra for undifferentiated autoinflammatory diseases in children: a retrospective case review. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2019;3(1):rkz004. doi: 10.1093/rap/rkz004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brunner HI, Rider LG, Kingsbury DJ, Co D, Schneider R, Goldmuntz E, et al. Pediatric rheumatology collaborative study group - over four decades of pivotal clinical drug research in pediatric rheumatology. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2018;16(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s12969-018-0261-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jung JY, Kim MY, Suh CH, Kim HA. Off-label use of tocilizumab to treat non-juvenile idiopathic arthritis in pediatric rheumatic patients: a literature review. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2018;16(1):79. doi: 10.1186/s12969-018-0296-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vitale A, Insalaco A, Sfriso P, Lopalco G, Emmi G, Cattalini M, et al. A snapshot on the on-label and off-label use of the Interleukin-1 inhibitors in Italy among rheumatologists and pediatric rheumatologists: a Nationwide multi-center retrospective observational study. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:380. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez GAM, Reinhardt A, Ramsey S, Wittkowski H, Hashkes PJ, Berkun Y, et al. JAK1/2 inhibition with baricitinib in the treatment of autoinflammatory interferonopathies. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(7):3041–3052. doi: 10.1172/JCI98814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomez-Garcia F, Sanz-Cabanillas JL, Viguera-Guerra I, Isla-Tejera B, Nieto AV, Ruano J. Scoping review on use of drugs targeting interleukin 1 pathway in DIRA and DITRA. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2018;8(4):539–556. doi: 10.1007/s13555-018-0269-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woerner A, Belot A, Merlin E, Wouters C, Berthet G, Kondi A, et al. Prescribed but not approved: biologic agents used without approval in juvenile idiopathic arthritis in Switzerland, France and Belgium. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2014;12(1):P338. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-12-S1-P338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyadzhiev M, Marinov L, Boyadzhiev V, Iotova V, Aksentijevich I, Hambleton S. Disease course and treatment effects of a JAK inhibitor in a patient with CANDLE syndrome. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2019;17(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s12969-019-0322-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Picco P, Brisca G, Traverso F, Loy A, Gattorno M, Martini A. Successful treatment of idiopathic recurrent pericarditis in children with interleukin-1beta receptor antagonist (anakinra): an unrecognized autoinflammatory disease? Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(1):264–268. doi: 10.1002/art.24174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ozen S, Sonmez HE, Demir S. Pediatric forms of vasculitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2018;32(1):137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lei C, Huang Y, Yuan S, Chen W, Liu H, Yang M, et al. Takayasu Arteritis With Coronary Artery Involvement: Differences Between Pediatric and Adult Patients. Can J Cardiol. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Condie D, Grabell D, Jacobe H. Comparison of outcomes in adults with pediatric-onset morphea and those with adult-onset morphea: a cross-sectional study from the morphea in adults and children cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(12):3496–3504. doi: 10.1002/art.38853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tarr T, Derfalvi B, Gyori N, Szanto A, Siminszky Z, Malik A, et al. Similarities and differences between pediatric and adult patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2015;24(8):796–803. doi: 10.1177/0961203314563817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fonseca R, Aguiar F, Rodrigues M, Brito I. Clinical phenotype and outcome in lupus according to age: a comparison between juvenile and adult onset. Reumatol Clin. 2018;14(3):160–163. doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Panupattanapong S, Stwalley DL, White AJ, Olsen MA, French AR, Hartman ME. Epidemiology and outcomes of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis in pediatric and working-age adult populations in the United States: analysis of a large National Claims Database. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(12):2067–2076. doi: 10.1002/art.40577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denby KJ, Clark DE, Markham LW. Management of Kawasaki disease in adults. Heart. 2017;103(22):1760–1769. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piram M, Mahr A. Epidemiology of immunoglobulin a vasculitis (Henoch-Schonlein): current state of knowledge. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25(2):171–178. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32835d8e2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Girschick H, Finetti M, Orlando F, Schalm S, Insalaco A, Ganser G, et al. The multifaceted presentation of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: a series of 486 cases from the Eurofever international registry. Rheumatology. 2018;57(7):1203–1211. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rigante D, Vitale A, Natale MF, Lopalco G, Andreozzi L, Frediani B, et al. A comprehensive comparison between pediatric and adult patients with periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenopathy (PFAPA) syndrome. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36(2):463–468. doi: 10.1007/s10067-016-3317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Constantin T, Foeldvari I, Anton J, de Boer J, Czitrom-Guillaume S, Edelsten C, et al. Consensus-based recommendations for the management of uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: the SHARE initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(8):1107–1117. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, Burns JC, Bolger AF, Gewitz M, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term Management of Kawasaki Disease: a scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(17):e927–ee99. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahmood I. Pharmacokinetic considerations in designing pediatric studies of proteins, antibodies, and plasma-derived products. Am J Ther. 2016;23(4):e1043–e1056. doi: 10.1097/01.mjt.0000489921.28180.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van den Anker J, Reed MD, Allegaert K, Kearns GL. Developmental changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;58(Suppl 10):S10–S25. doi: 10.1002/jcph.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kearns GL, Abdel-Rahman SM, Alander SW, Blowey DL, Leeder JS, Kauffman RE. Developmental pharmacology--drug disposition, action, and therapy in infants and children. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(12):1157–1167. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Samardzic J, Allegaert K, Bajcetic M. Developmental pharmacology: a moving target. Int J Pharm. 2015;492(1–2):335–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nigrovic PA, Raychaudhuri S, Thompson SD. Review: genetics and the classification of arthritis in adults and children. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(1):7–17. doi: 10.1002/art.40350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malik P, Edginton A. Pediatric physiology in relation to the pharmacokinetics of monoclonal antibodies. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2018;14(6):585–599. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2018.1482278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore P. Children are not small adults. Lancet. 1998;352(9128):630. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79591-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Allegaert K. Developmental Pharmacology - Special Issues During Childhood and Adolescence. Drug Res (Stuttg) 2018;68(S 01):S10–SS1. doi: 10.1055/a-0731-6913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Renton WD, Ramanan AV. Better pharmacologic data the key to optimizing biological therapies in children. Rheumatology. 2020;59(2):271–272. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Quartier P, Paz E, Rubio-Perez N, Silva CA, et al. Abatacept in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9636):383–391. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60998-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Li T, Sztajnbok F, Goldenstein-Schainberg C, Scheinberg M, et al. Abatacept improves health-related quality of life, pain, sleep quality, and daily participation in subjects with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(11):1542–1551. doi: 10.1002/acr.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Quartier P, Paz E, Rubio-Perez N, Silva CA, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of abatacept in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(6):1792–1802. doi: 10.1002/art.27431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruperto N, Lovell D, Bohnsack J, Breedt J, Fischbach M, Lutz T, et al. Subcutaneous or IntravenousAbatacept Monotherapy in Pediatric Patients with Polyarticular-Course JIA: Results from Two Phase III Trials [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019; 71 (suppl 10). https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/subcutaneous-or-intravenous-abatacept-monotherapy-in-pediatric-patients-with-polyarticular-course-jia-results-from-two-phase-iii-trials/. Accessed 23 Mar 2020.

- 52.Ilowite N, Porras O, Reiff A, Rudge S, Punaro M, Martin A, et al. Anakinra in the treatment of polyarticular-course juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: safety and preliminary efficacy results of a randomized multicenter study. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28(2):129–137. doi: 10.1007/s10067-008-0995-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.European Medicines Agency . CHMP extension of indication variation assessment report (anakinra) 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Quartier P, Allantaz F, Cimaz R, Pillet P, Messiaen C, Bardin C, et al. A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist anakinra in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (ANAJIS trial) Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(5):747–754. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.134254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ruperto N, Brunner HI, Quartier P, Constantin T, Wulffraat N, Horneff G, et al. Two randomized trials of canakinumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(25):2396–2406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Food US, Administration D. Medical review and evaluation (canakinumab) 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 57.European Medicines Agency . Summary of product characteristics (canakinumab) 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 58.ClinicalTrials.gov. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2000 Feb 29 - . Identifier NCT00534495, Safety and Effectiveness of Rilonacept for Treating Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis in Children and Young Adults; 2007 Sept 26 [cited 2020 July 15]; [about 14 screens]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00534495

- 59.Ilowite NT, Prather K, Lokhnygina Y, Schanberg LE, Elder M, Milojevic D, et al. Randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of rilonacept in the treatment of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(9):2570–2579. doi: 10.1002/art.38699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lovell DJ, Giannini EH, Reiff AO, Kimura Y, Li S, Hashkes PJ, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of rilonacept in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(9):2486–2496. doi: 10.1002/art.38042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brunner HI, Ruperto N, Zuber Z, Keane C, Harari O, Kenwright A, et al. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in patients with polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from a phase 3, randomised, double-blind withdrawal trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):1110–1117. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.ClinicalTrials.gov. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2000 Feb 29 - . Identifier NCT00988221, A Study of Tocilizumab in Patients With Active Polyarticular Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis; 2009 Oct 2 [cited 2020 July 15]; [about 50 screens]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00988221

- 63.Brunner H, Chen C, Martini A, Espada G, Joos R, Akikusa J, et al. Disability and Health-Related Quality of Life Outcomes in Patients with Systemic or Polyarticular Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Treated with Tocilizumab in Randomized Controlled Phase 3 Trials [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019; 71 (suppl 10). https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/disability-and-health-related-quality-of-life-outcomes-in-patients-with-systemic-or-polyarticular-juvenile-idiopathic-arthritis-treated-with-tocilizumab-in-randomized-controlled-phase-3-trials/. Accessed 23 Mar 2020.

- 64.US Food and Drug Administration. Medical review and evaluation (tocilizumab), 2013. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2013/125276Orig1s064.pdf. (23 March 2020, date last accessed)

- 65.European Medicines Agency. Assessment report (tocilizumab), 2013. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/variation-report/roactemra-h-c-955-ii-0026-epar-assessment-report-variation_en.pdf (23 March 2020, date last accessed).

- 66.De Benedetti F, Brunner HI, Ruperto N, Kenwright A, Wright S, Calvo I, et al. Randomized trial of tocilizumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(25):2385–2395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.ClinicalTrials.gov. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2000 Feb 29 - . Identifier NCT00642460, A Study of RoActemra/Actemra (Tocilizumab) in Patients With Active Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA); 2008 Mar 25 [cited 2020 July 15]; [about 64 screens]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00642460

- 68.Yokota S, Imagawa T, Mori M, Miyamae T, Aihara Y, Takei S, et al. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, withdrawal phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9617):998–1006. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burgos-Vargas R, Tse SM, Horneff G, Pangan AL, Kalabic J, Goss S, et al. A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study of Adalimumab in pediatric patients with Enthesitis-related arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2015;67(11):1503–1512. doi: 10.1002/acr.22657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.European Medicines Agency . Assessment report for paediatric studies submitted according to Article 46 of the Regulation (EC) No 1901/2006 (adalimumab) 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 71.European Medicines Agency . CHMP extension of indication variation assessment report (adalimumab) 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Horneff G, Fitter S, Foeldvari I, Minden K, Kuemmerle-Deschner J, Tzaribacev N, et al. Double blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial with adalimumab for treatment of juvenile onset ankylosing spondylitis (JoAS): significant short term improvement. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(5):R230. doi: 10.1186/ar4072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lovell DJ, Ruperto N, Goodman S, Reiff A, Jung L, Jarosova K, et al. Adalimumab with or without methotrexate in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(8):810–820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.European Medicines Agency . Assessment report (adalimumab) 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ramanan AV, Dick AD, Jones AP, McKay A, Williamson PR, Compeyrot-Lacassagne S, et al. Adalimumab plus methotrexate for uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(17):1637–1646. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.European Medicines Agency . Assessment report (adalimumab) 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Quartier P, Baptiste A, Despert V, Allain-Launay E, Kone-Paut I, Belot A, et al. ADJUVITE: a double blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial of adalimumab in early onset, chronic, juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated anterior uveitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(7):1003–1011. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Horneff G, Foeldvari I, Minden K, Trauzeddel R, Kummerle-Deschner JB, Tenbrock K, et al. Efficacy and safety of etanercept in patients with the enthesitis-related arthritis category of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from a phase III randomized, double-blind study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(8):2240–2249. doi: 10.1002/art.39145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lovell DJ, Giannini EH, Reiff A, Cawkwell GD, Silverman ED, Nocton JJ, et al. Etanercept in children with polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatric rheumatology collaborative study group. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(11):763–769. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003163421103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.US Food and Drug Administration . Medical review and evaluation (etanercept) 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 81.ClinicalTrials.gov. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2000 Feb 29 - . Identifier NCT03780959, Safety and Efficacy of Etanercept (Recombinant Human Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Fusion Protein [TNFR:Fc]) in Children With Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis (JRA); 2018 Dec 19 [cited 2020 July 15]; [about 12 screens]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT03780959

- 82.ClinicalTrials.gov. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2000 Feb 29 - . Identifier NCT03781375, Etanercept Plus Methotrexate Versus Methotrexate Alone in Children With Polyarticular Course Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis; 2018 Dec 19 [cited 2020 July 15]; [about 13 screens]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT03781375

- 83.Wallace CA, Giannini EH, Spalding SJ, Hashkes PJ, O'Neil KM, Zeft AS, et al. Trial of early aggressive therapy in polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(6):2012–2021. doi: 10.1002/art.34343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wallace CA, Giannini EH, Spalding SJ, Hashkes PJ, O'Neil KM, Zeft AS, et al. Clinically inactive disease in a cohort of children with new-onset polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis treated with early aggressive therapy: time to achievement, total duration, and predictors. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(6):1163–1170. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.ClinicalTrials.gov. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2000 Feb 29 - . Identifier NCT00078806, Safety and Efficacy Study of Etanercept (Enbrel®) In Children With Systemic Onset Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis; 2004 Mar 9 [cited 2020 July 15]; [about 24 screens]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00078806

- 86.Hissink Muller PC, Brinkman DM, Schonenberg D, Koopman-Keemink Y, Brederije IC, Bekkering WP, et al. A comparison of three treatment strategies in recent onset non-systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: initial 3-months results of the BeSt for Kids-study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2017;15(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12969-017-0138-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hissink Muller P, Brinkman DMC, Schonenberg-Meinema D, van den Bosch WB, Koopman-Keemink Y, Brederije ICJ, et al. Treat to target (drug-free) inactive disease in DMARD-naive juvenile idiopathic arthritis: 24-month clinical outcomes of a three-armed randomised trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(1):51–59. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Brunner HI, Ruperto N, Tzaribachev N, Horneff G, Chasnyk VG, Panaviene V, et al. Subcutaneous golimumab for children with active polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results of a multicentre, double-blind, randomised-withdrawal trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(1):21–29. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.European Medicines Agency . Assessment report (golimumab) 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Cuttica R, Wilkinson N, Woo P, Espada G, et al. A randomized, placebo controlled trial of infliximab plus methotrexate for the treatment of polyarticular-course juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(9):3096–3106. doi: 10.1002/art.22838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tynjala P, Vahasalo P, Tarkiainen M, Kroger L, Aalto K, Malin M, et al. Aggressive combination drug therapy in very early polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (ACUTE-JIA): a multicentre randomised open-label clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(9):1605–1612. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.143347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brunner H, Synoverska O, Ting T, Abud Mendoza C, Spindler A, Vyzhga Y, et al. Tofacitinib for the Treatment of Polyarticular Course Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: Results of a Phase 3 Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Withdrawal Study [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10) https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/tofacitinib-for-the-treatment-of-polyarticular-course-juvenile-idiopathic-arthritis-results-of-a-phase-3-randomized-double-blind-placebo-controlled-withdrawal-study/. Accessed 23 Mar 2020.

- 93.Landells I, Marano C, Hsu MC, Li S, Zhu Y, Eichenfield LF, et al. Ustekinumab in adolescent patients age 12 to 17 years with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of the randomized phase 3 CADMUS study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(4):594–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.ClinicalTrials.gov. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2000 Feb 29 - . Identifier NCT03073200, Study of Ixekizumab (LY2439821) in Children 6 to Less Than 18 Years With Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis (Ixora-peds); 2017 Mar 08 [cited 2020 July 15]; [about 32 screens]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT03073200

- 95.Papp K, Thaci D, Marcoux D, Weibel L, Philipp S, Ghislain PD, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab every other week versus methotrexate once weekly in children and adolescents with severe chronic plaque psoriasis: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10089):40–49. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.European Medicines Agency . Assessment report for paediatric studies submitted according to Article 46 of the Regulation (EC) No 1901/2006 (adalimumab) 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 97.European Medicines Agency . Extension of indication variation assessment report (adalimumab) 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 98.ClinicalTrials.gov. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2000 Feb 29 - . Identifier NCT01251614, A Double Blind Study in Pediatric Subjects With Chronic Plaque Psoriasis, Studying Adalimumab vs. Methotrexate); 2010 Dec 2 [cited 2020 July 15]; [about 48 screens]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT01251614

- 99.Portman MA, Dahdah NS, Slee A, Olson AK, Choueiter NF, Soriano BD, et al. Etanercept With IVIg for Acute Kawasaki Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatrics. 2019;143(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 100.Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Langley RG, Gottlieb AB, Pariser D, Landells I, et al. Etanercept treatment for children and adolescents with plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(3):241–251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Langley RG, Paller AS, Hebert AA, Creamer K, Weng HH, Jahreis A, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in pediatric patients with psoriasis undergoing etanercept treatment: 12-week results from a phase III randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(1):64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Siegfried EC, Eichenfield LF, Paller AS, Pariser D, Creamer K, Kricorian G. Intermittent etanercept therapy in pediatric patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(5):769–774. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Landells I, Paller AS, Pariser D, Kricorian G, Foehl J, Molta C, et al. Efficacy and safety of etanercept in children and adolescents aged > or = 8 years with severe plaque psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20(3):323–328. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.0911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.European Medicines Agency . Assessment report (etanercept) 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Han CL, Zhao SL. Intravenous immunoglobulin gamma (IVIG) versus IVIG plus infliximab in young children with Kawasaki disease. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:7264–7270. doi: 10.12659/MSM.908678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mori M, Hara T, Kikuchi M, Shimizu H, Miyamoto T, Iwashima S, et al. Infliximab versus intravenous immunoglobulin for refractory Kawasaki disease: a phase 3, randomized, open-label, active-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter trial. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1994. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18387-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tremoulet AH, Jain S, Jaggi P, Jimenez-Fernandez S, Pancheri JM, Sun X, et al. Infliximab for intensification of primary therapy for Kawasaki disease: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1731–1738. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jaggi P, Wang W, Dvorchik I, Printz B, Berry E, Kovalchin JP, et al. Patterns of fever in children after primary treatment for Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34(12):1315–1318. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.ClinicalTrials.gov. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2000 Feb 29 - . Identifier NCT00589628, Multi Center Prospective Registry of Infliximab Use for Childhood Uveitis; 2008 Jan 10 [cited 2020 July 15]; [about 7 screens]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00589628