Abstract

Current classifications of sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (sCJD) identify five subtypes associated with different disease phenotypes. Most of these histopathological phenotypes (histotypes) co-distribute with distinct pairings of methionine (M)/valine (V) genotypes at codon 129 of the prion protein (PrP) gene and the type (1 or 2) of the disease-associated PrP (PrPD). Types 1 and 2 are defined by the molecular mass (~ 21 kDa and ~ 19 kDa, respectively) of the unglycosylated isoform of the proteinase K-resistant PrPD (resPrPD). We recently reported that the sCJDVV1 subtype (129VV homozygosity paired with PrPD type 1, T1) shows an electrophoretic profile where the resPrPD unglycosylated isoform is characterized by either one of two single bands of ~ 20 kDa (T120) and ~ 21 kDa (T121), or a doublet of ~ 21–20 kDa (T121−20). We also showed that T120 and T121 in sCJDVV have different conformational features but are associated with indistinguishable histotypes. The presence of three distinct molecular profiles of T1 is unique and raises the issue as to whether T120 and T121 represent distinct prion strains. To answer this question, brain homogenates from sCJDVV cases harboring each of the three resPrPD profiles, were inoculated to transgenic (Tg) mice expressing the human PrP-129M or PrP-129V genotypes. We found that T120 and T121 were faithfully replicated in Tg129V mice. Electrophoretic profile and incubation period of mice challenged with T121−20 resembled those of mice inoculated with T121 and T120, respectively. As in sCJDVV1, Tg129V mice challenged with T121 and T120 generated virtually undistinguishable histotypes. In Tg129M mice, T121 was not replicated while T120 and T121−20 generated a ~ 21–20 kDa doublet after lengthier incubation periods. On second passage, Tg129M mice incubation periods and regional PrP accumulation significantly differed in T120 and T121−20 challenged mice. Combined, these data indicate that T121 and T120 resPrPD represent distinct human prion strains associated with partially overlapping histotypes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40478-021-01132-7.

Keywords: Prion protein, sCJDVV1, Prion strain, Histotype, Transmission properties, Lesion profile, Plaques

Introduction

For several years sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (sCJD) has been grouped into five distinct subtypes, denoted as sCJDMM(MV)1, -MM2, -MV2, -VV1 and -VV2 [18, 38]. This grouping is based on the combination of two major molecular determinants of the disease phenotype: the methionine (M)/valine (V) polymorphic genotype at codon 129 of the prion protein (PrP), which dictates the MM, MV and VV 129 genotypes, and the type 1 or 2 of the disease-associated PrP (PrPD) [7, 8, 31, 38]. PrPD types 1 (T1) and 2 (T2) are distinguished by their respective ~ 21 kDa and ~ 19 kDa electrophoretic mobilities following treatment with proteinase K (PK), which are commonly monitored (for practical reasons) with the unglycosylated isoform (lower band) of the PK-resistant PrPD (resPrPD) [17]. The distinct mobility reflects the different sizes of the PK-resistant region and, therefore, the distinct conformations of the T1 and T2 PrPD isoforms [31, 36, 40].

In this study, which is part of a body of research on sCJD subtypes, we focus on sCJDVV1, the least investigated subtype, especially with regard to the characteristics of its PrPD [11, 37].

Sporadic CJDVV1 is also the rarest of the five subtypes, accounting for 2–3% of sCJD [11, 39, 46]; it presents at a younger age on average, with clinical onset often in the 3th or 4th decade of life, and has a relatively long course that often exceeds one year [11, 18, 41]. Phenotypically, sCJDVV1 is easily distinguishable from the other sCJD subtypes by the type and distribution of the histological lesions (histotype), which include severe spongiform degeneration (SD) with medium size vacuoles throughout the cerebral cortex, presence of ballooned neurons and widespread but light PrP deposition [11]. The electrophoretic profile of sCJDVV1 resPrPD T1 is complex, as shown by the heterogeneity of the unglycosylated isoform. We recently identified three alternative electrophoretic profiles or variants of T1: the T120 and T121 variants, where the two resPrPD fragments of ~ 21 and ~ 20 kDa occur separately, and the T121−20 variant where the two resPrPD fragments coexist in different ratios [11]. We also observed that T121 and T120 have distinct conformational characteristics suggesting that they represent distinct strains. Nonetheless, the histotypes associated with the T120, T121 and T121−20 variants are similar violating the tenet that distinct prion strains are associated with distinct phenotypes [6, 17, 42].

To further investigate this issue, transgenic (Tg) mice expressing normal or cellular human PrP (PrPC) with the codon 129 residue V (Tg129V) or M (Tg129M), were inoculated with sCJDVV1 brain isolates containing T120, T121 or T121−20* (the last isolate was obtained from a sCJDVV1-2 case harboring tiny amounts of T2, denoted by asterisk). Brain extracts from sCJDVV2, a different sCJD subtype that harbors resPrPD T2 (with a ~ 19 kDa unglycosylated fragment), were inoculated as controls. Both T120 and T121 were faithfully replicated in Tg129V mice with T121 showing a longer incubation period, whereas T121−20* was reproduced as T121. Replication was longer and less faithful in the Tg129M mice: the ~ 21–20 kDa resPrPD doublet was generated following inoculations with T120, and T121 was not transmitted. The histotype in T120 and T121−20*-inoculated Tg129M mice was characterized by the overlapping lesion profiles and the lack, in T121−20*-inoculated mice only, of PrP deposits in cerebral cortex and cerebellum. Second passage in Tg129M mice recapitulated the results of the first passage except for the significantly shorter and different incubation periods of T120 and T121−20*-infected mice.

The transmission in Tg129V mice of both T121 and T120 with the accurate replication of their electrophoretic profiles, along with the lack of replication of T121 only following serial transmissions in Tg129M mice suggest that T121 and T120 are distinct prion strains even though they are associated with similar histotypes in sCJDVV1.

Materials and methods

sCJDVV case-patients

Four cases of sCJDVV1, one case of sCJDVV1-2 and one case of sCJDVV2 (cases 2–5, 16 and 6, respectively, of Table S2 of Cali et al. [11]; Additional file 5: Table S1 of the present study) were used as inocula for the transmission study. Inocula were generated from the frontal cortex (sCJDVV1, N = 3; sCJDVV2, N = 1), parietal cortex (sCJDVV1, N = 1), occipital cortex (sCJDVV1-2, N = 1) and putamen (sCJDVV2, N = 1) (Additional file 5: Table S1). All samples were obtained from the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center (NPDPSC) in Cleveland, USA.

Features of resPrPD of the inocula

The inocula containing resPrPD T120 were obtained from three cases of sCJDVV1 while inocula harboring T121 and T2 were each isolated from one case of sCJDVV1 and sCJDVV2, respectively; T2 was used as control. T121−20* corresponds to T1 variant with a ~ 21–20 kDa doublet co-existing with T2 (the latter accounting for ~ 5% of the total resPrPD) harvested from a case of sCJDVV1-2 that had histotype mostly consistent with sCJDVV1 (Additional file 5: Table S1). Immunoblotting characterization of the inocula confirmed the previously established electrophoretic profiles of T120 and T121 resPrPD variants and excluded the presence of T2 (Additional file 1: Figure S1). The consistent predominance of the ~ 21 kDa component in the T121−20* variant was also confirmed. Of note, the small T2 component of T121−20* was detected with the T2-specific Ab Tohoku-2 (data not shown), but not with the type generic 3F4 (Additional file 1: Figure S1). T2 in sCJDVV2 was harvested from the frontal cortex and putamen, which were used as separate inocula.

Transgenic mice

Two Tg mouse lines, the Tg362 and Tg340, were used [34, 35]. They express the human PrPC-129V (Tg362) and PrPC-129M (Tg340) at ~ eightfold and ~ fourfold normal human brain levels, respectively, and are hereafter identified as Tg129V and Tg129M.

Intracerebral inoculations

Twenty microliters of ten percent (wt/vol) brain homogenates (BH) in 5% glucose generated from the sCJDVV cases were inoculated intracerebrally according to previously described procedures [35]. A total of 99 Tg mice were inoculated in this study. Brain homogenates from Tg129M mice challenged with each of the three T1 variants were used for a second passage in the same mouse line.

Histology, immunohistochemistry, lesion profiles, and morphometric analysis

Histological and immunohistochemical examinations were carried out on four brain levels at approximately bregma 0.5 mm, − 1.7 mm, − 3.8 mm and − 6.0 mm, as previously described [10]. Paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H.E.) or probed with the Ab 3F4 [22, 47] to human PrP (residues 106–110) at 1:1,000 and 1:400 dilutions as previously described [10]. Lesion profiles were performed using semi-quantitative evaluation for severity of SD, which was rated on a 0–3 scale on H.E.-stained sections (0 = not detectable; 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe) [14]. Each point of the lesion profiles and bar graphs in Figs. 2 and Additional file 3: S3 were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The eight brain regions examined included the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, basal ganglia, thalamus, hypothalamus, superior and inferior brainstem, and cerebellum. The semi-quantitative assessment of gliosis severity and neuronal loss in the cerebellum was rated on a 0–3 scale as noted above. Morphometric analysis to assess vacuole-size was carried out on the cerebral cortex at the level of bregma − 1.7 mm, and measured by the software Image-Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics, Inc.) [23].

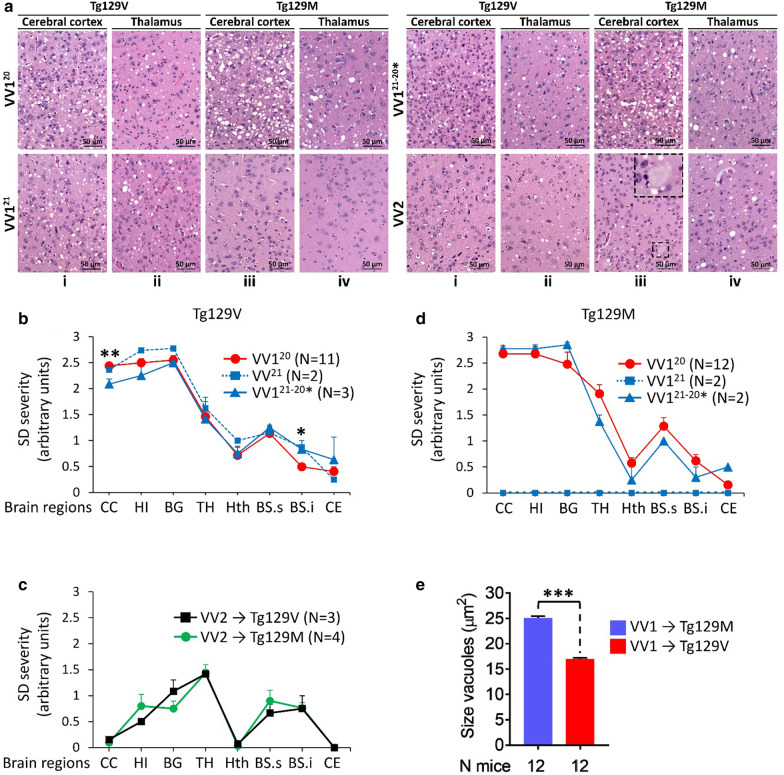

Fig. 2.

Histopathology, lesions profiles and vacuole size determinations. a: Hematoxylin and Eosin (H.E.) staining. VV120, VV121, VV121−20* and VV2 refer to the inocula. Tg129V, i-ii, VV120, VV121 and VV121−20*: Spongiform degeneration (SD) affecting more severely the cerebral cortex than thalamus. i-ii, VV2: Scant SD in the cerebral cortex and prominent in the thalamus. Tg129M, iii-vi, VV120 and VV121−20*: SD with large vacuoles. iii-iv, VV121: Mouse brain free of lesions. iii-iv, VV2: Cortical plaques; inset, iii: high magnification of a plaque. b and c: Profiles of brain distribution and severity of SD were similar in Tg129V mice challenged with VV120, VV121, and VV121−20* (b), and in Tg mice challenged with VV2 (c). d: Profiles in Tg129M mice inoculated with VV120 and VV121−20* were similar; VV121-inoculated mice were free of lesions. e: Vacuole size averaged from nine VV120 and three VV121−20* challenged mice was ~ 8 µm2 greater in Tg129M than Tg129V. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.003, ***P < 0.0001. CC: Cerebral cortex, HI: hippocampus, BG: basal ganglia, TH: thalamus, Hth: hypothalamus, BS.s: brainstem, superior, BS.i: brainstem, inferior, CE: cerebellum

Preparation of brain homogenates, PK digestion and Western blot analysis

Ten percent (wt/vol) BH of human cases were prepared using 1X LB100 (100 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 10 mM EDTA, 100 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0), and supernatants (S1) were collected following centrifugation at 1000 × g for 5 min (min) at 4 °C. For the mouse brains, 10% BH prepared in 5% glucose was mixed with an equal volume of 2X LB100 (pH 8.0) and centrifuged at 1000 x g for 5 min. Human and mouse S1 were subjected to enzymatic digestion with 10 Units/ml (U/ml) PK (Sigma Aldrich), which was used at 48 U/mg PK specific activity (1 U/ml is equal to 20.8 μg/ml PK) at 37 °C for 1 h (h). Enzymatic reaction was stopped by the addition of 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) prior to the dilution of each sample with an equal volume of 2 × Laemmli buffer (6% SDS, 20% glycerol, 4 mM EDTA, 5% β –mercaptoethanol, 125 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.8) and then denaturation at 100 °C for 10 min.

Proteins from human S1 were separated on 15% Tris–HCl SDS–polyacrylamide long gels (W x L: 20 cm × 20 cm) (Bio-Rad PROTEAN® II xi cell system) as originally described [9]. Proteins from the mouse S1 were separated on 15% Criterion™ Tris–HCl Precast Gels (W × L: 13.3 cm × 8.7 cm)[9] (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Proteins were blotted onto the Immobilon-FL PVDF membrane (8.7 cm-long gels) or Immobilon-P PVDF membrane (20 cm-long gels) (EMD-Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), blocked with a blocking buffer and probed with Ab 3F4 (1:10,000), 1E4 (1:500) and Tohoku-2 (1:10,000). The Ab Tohoku-2 was kindly provided by Dr. Tetsuyuki Kitamoto [28]. Membranes were developed by (1) the enhanced chemiluminesce reaction using ECL and ECL plus reagents, and signal was captured on MR and XAR films (20 cm-long gels), or (2) by the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LICOR Biosciences) (8.7 cm-long gels) as described by the manufacturer.

Results

Transmission features and characterization of resPrPD variants in Tg mice

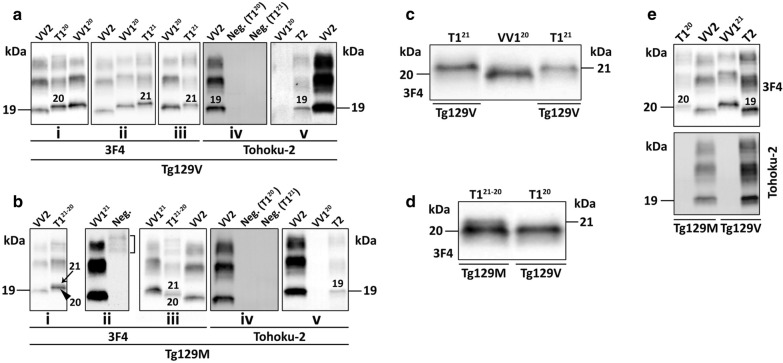

In Tg129V mice, all three T1 variants and T2 transmitted with 100% attack rate. Incubation periods or days post inoculation (dpi) varied; it was the longest for T121 (425 ± 66 dpi) and the shortest for T121−20* (315 ± 66 dpi) even though the difference did not rich statistical significance (Tables 1 and Additional file 5: S2). T2 transmitted in 215 ± 18 dpi, which was significantly different (P < 0.0001) from the incubations of all T1 variants combined. T120 and T121 electrophoretic mobility and Ab immunoreactivity were indistinguishable from those of the respective inocula (Fig. 1a, c, d). By contrast, the T121−20* inoculum (with predominance of the T121 component and presence of ~ 5% T2) was reproduced only as T121, with the addition of a weak band of ~ 19 kDa that was detectable with the T2-specific Ab Tohoku-2 but not with the type generic 3F4, mirroring the T2 of the inoculum (Table 1 and Fig. 1a). T2 was faithfully replicated as the typical ~ 19 kDa resPrPD T2 (Fig. 1e). Ancillary transmission studies with hemizygous Tg129V mice challenged with T120 and T2 isolates led to results similar to those obtained with homozygous mice with the exception of longer incubation periods (data not shown).

Table 1.

Transmission features of sCJDVV resPrPD to Tg129V and Tg129M mice

| Tg129V (1st pass.) | ||||

| Inoculum | VV120 | VV121 | VV121−20* | VV2 |

| Attack rate (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Incubation (dpi) | 351 ± 16 | 425 ± 66 | 315 ± 66 | 215 ± 18 |

| resPrPD replicated | T120 (To-2 -) | T121 (To-2 -) | T121 (To-2 +) | T2 (To-2 +) |

| Tg129M (1st pass.) | ||||

| Inoculum | VV120 | VV121 | VV121−20* | VV2 |

| Attack rate (%) | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| Incubation (dpi) | 554 ± 53 | 0 | 570 ± 60 | 626 ± 56 |

| resPrPD replicated | T121−20 (To-2 -) | No transmis | T121−20 (To-2 +) | T120 (To-2 -) |

| Tg129M (2nd pass.) | ||||

| Inoculum | VV120 | VV121 | VV121−20* | ND |

| Attack rate (%) | 100 | 0 | 100 | ND |

| Incubation (dpi) | 338 ± 30 | 0 | 292 ± 16 | ND |

| resPrPD replicated | T121−20 (To-2: ND) | No transmis | T121−20 (To-2: ND) | ND |

resPrPD: proteinase K (PK)-resistant PrPD; dpi: days post-inoculation (mean value ± standard deviation). Tohoku-2 positive (To-2 +) or negative (To-2 −) immunoreactivity. VV121−20*: sCJDVV1-2 with T2 accounting for ~ 5% of total resPrPD. Dpi (1st pass.), Tg129V: VV2 vs. VV120, P < 0.0008; VV2 vs. VV121, P < 0.04; VV120 vs. VV121 or VV121−20*, P > 0.05. Dpi (1st pass.), Tg129M: VV2 vs. VV120, P < 0.03; VV2 vs. VV121–20* and VV120 vs. VV121−20*, P > 0.05; Dpi (2nd pass.), Tg129M: VV120 vs. VV121−20*, P < 0.009. Dpi, Tg129M: 1st vs. 2nd passage of VV120 or VV121−20*, P < 0.0001. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA and Student’s t-test. No transmis.: no transmission; pass.: passage; ND: not done

Fig. 1.

Characterization of mouse brain resPrPD. T1 and T2 and their superscripts atop of each blot refer to the mouse resPrPD type and variant; VV120, VV121 and VV2 refer to resPrPD obtained from sCJDVV cases. a, i-ii: The unglycosylated isoform of the mouse resPrPD migrated to either ~ 20 kDa (i, “20”) or ~ 21 kDa (ii, “21”) accurately replicating the resPrPD of VV120 and VV121, respectively; iii and v: VV121−20* inoculum was reproduced as T121 (iii, “21”) with the additional presence of a Tohoku-2-immunoreactive ~ 19 kDa band (v, “19”); iv: Tohoku-2 showing a negative (Neg.) immunoreactivity for T120 and T121 that were detected by 3F4 in i and ii, respectively. b, i and iii: Mice challenged with VV120 (i) and VV121−20* (iii) generated resPrPD T121−20 with a predominant ~ 20 kDa fragment (arrowhead, i) over a ~ 21 kDa band (arrow, i). ii: Mice challenged with VV121 were all negative; bracket: mouse immunoglobulins. iv and v: Tohoku-2 immunoreacted with T2 in mice challenged with VV121−20* (v) but not in those inoculated with VV120 or VV121 (iv). c-d: Magnification of unglycosylated resPrPD fragments. C: Mouse resPrPD migrated to ~ 21 kDa in Tg129V inoculated with VV121 (lane 1) or VV121−20* (lane 3). d: A small fragment of ~ 21 kDa migrating above a prominent one of ~ 20 kDa (lane 1), or a single band of ~ 20 kDa (lane 2), was detected in Tg129M or Tg129V inoculated with VV120. e: Mice challenged with VV2. Top panel, Ab 3F4: Mouse resPrPD migrated to either ~ 19 kDa (“19”) in Tg129V or ~ 20 kDa (“20”) in Tg129M. Bottom panel, Ab Tohoku-2: The mouse resPrPD of ~ 19 kDa, but not the ~ 20 kDa band, was detected by Tohoku-2

Tg129M mice showed a 100% attack rate following challenge with T120, T121−20* and T2, whereas T121 failed to replicate. T120 and T121−20* essentially shared the incubation periods (554 ± 53 dpi and 570 ± 60 dpi, respectively), which, on average, were 1.7 times longer than those of Tg129V (Tables 1 and Additional file 5: S2). The incubation period following inoculation with T2 was nearly three times longer than Tg129V (Tables 1 and Additional file 5: S2). Overall, resPrPD replication was much less accurate: T120 replicated as T121−20* with ~ 20 kDa preponderance and no detectable T2, whereas T121−20* inoculation engendered both ~ 21 and ~ 20 kDa fragments but with an inverted ratio as compared to that of the inoculum, and with traces of T2 (Fig. 1b, d). Furthermore, T2 was replicated as T120, which immunoreacted with the resPrPD type non-specific 3F4 Ab but not with the resPrPD T2-specific Tohoku-2 Ab, clearly indicating that the resPrPD T2 of the inoculum was not replicated (Tables 1 and Additional file 5: S2, Fig. 1e). This finding contrasts with the apparently faithful replication of the ~ 19 kDa T2 by the Tg129V mice inoculated with sCJDVV2, and it is puzzling considering that bona fide T2 ~ 19 kDa fragment is reproduced by Tg129M mice after inoculation with T121−20* (Tables 1 and Additional file 5: S2, Fig. 1e). The second passage in Tg129M mice as the first, resulted in the replication of T120 and T121−20* only with indistinguishable electrophoretic profiles (Table 1 and Additional file 2: Figure S2). However, the incubation periods were respectively reduced ~ 1.6- and ~ 1.9-fold due to the strain adaptation (P < 0.0001). Furthermore, the ~ 50 days longer incubation period of mice inoculated with T120 also was statistical significant (T120: 338 ± 30 dpi; T121−20*: 292 ± 16 dpi; P < 0.009) (Tables 1 and Additional file 5: S2).

Histopathological and immunohistochemical features of inoculated Tg mice

Inoculations of resPrPD T120, T121 and T121−20* variants to Tg129V mice generated similar histopathological features (Table 2, Figs. 2, 3) consisting of prominent spongiform degeneration (SD) and astrogliosis of neocortex, hippocampus and basal ganglia, which progressively subsided caudally (except for a small peak in the brain stem) reaching the lowest level in the cerebellum. Vacuoles commonly were of medium or intermediate size, and plaques were not detected (Fig. 2a, b).

Table 2.

Histopathological and PrP immunohistochemical (IHC) features of inoculated Tg mice (1st passage)

| Mouse line | Inoculum | H.E | PrP IHC pattern | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD topography | Vacuole size | Plaques | Cerebral Cortex (CC) | Cerebellum | ||

| Tg129V | VV120 | ↑CC- ↓Tha | Medium | No | Granul. Aggreg | Focal, Grl. L |

| VV121−20* | ↑CC- ↓Th | Medium | No | Granul. Aggreg | Focal, Grl. L | |

| VV121 | ↑CC- ↓Th | Medium | No | Granul. Aggreg | Negative | |

| Tg129M | VV120 | ↑CC- ↓Th | Large | No | Granul. Aggreg | Focal, Grl. L |

| VV121−20* | ↑CC- ↓Th | Large | No | Negative | Negative | |

| VV121 | Negative | |||||

| Tg129V | VV2 | ↓CC- ↑Th | Small | Yes, BS | Plaque-like | Negative |

| Tg129M | VV2 | ↓CC- ↑Th | Small | Yes, widespread | Plaques | Plaques & plaque-like |

aArrows depict gradients of lesion severity: upward arrow = maximum; downward arrow = minimum; H.E.: Hematoxylin–eosin; SD: spongiform degeneration; CC: cerebral cortex; Th: thalamus; Granul. Aggreg.: granule aggregate; Grl. L.: granule cell layer; BS: brainstem

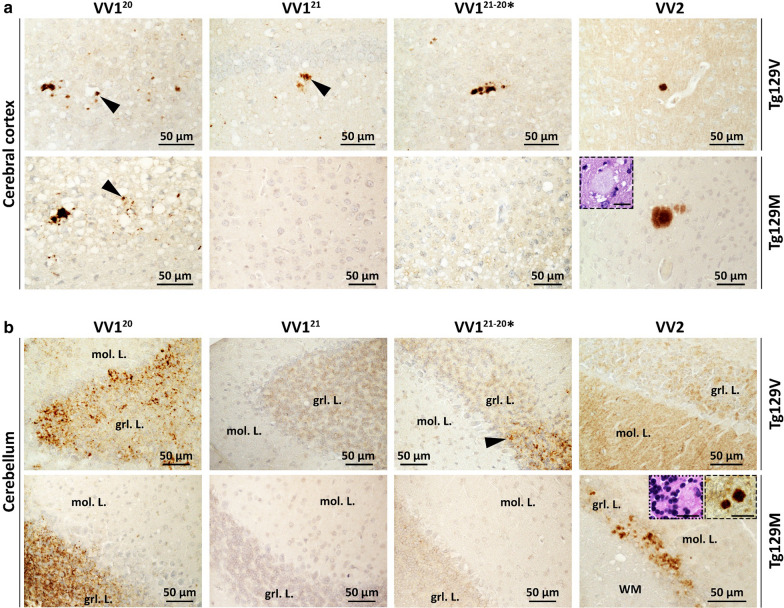

Fig. 3.

PrP immunohistochemistry (IHC). a: Cerebral cortex. 1st row, VV1: PrP granular deposits (arrowheads) often distributed around the rim of vacuoles. VV2: A plaque-like PrP. 2nd row, VV120: PrP deposits co-distributing with SD; arrowhead: granular PrP. VV121 and VV121−20*: negative PrP IHC. VV2: A PrP plaque; inset: H.E. staining of the plaque. b: Cerebellum. 1st row, VV120 and VV121−20*: PrP deposition affecting the granule cell layer (grl. L.); arrowhead, VV121−20*: granular PrP. VV121 and VV2: Negative PrP IHC; mol. L.: molecular layer. 2nd row, VV120: PrP deposition in grl. L. VV121 and VV121−20*: Negative PrP IHC. VV2: Plaque and plaque-like PrP ; dotted and dashed insets: two PrP plaques depicted on H.E. and IHC preparations, respectively. Scale bar insets: 20 µm; Ab: 3F4

Matching PrP immunostaining (IHC) showed some topographic variation. In the cerebral cortex the pattern was similar in the three T1 variants and consisted of individual granules or clusters of variable sizes that co-distributed with SD (Table 2 and Fig. 3a). However, while in T121 and T121−20*, the granular deposits were limited to the cerebral neocortex and hippocampus, T120 inoculated Tg mice displayed PrP granules also in subcortical regions. Furthermore, the cerebellum showed PrP deposition in the granule cell layer in T120 and T121−20* but it was entirely negative in T121 Tg mice (Table 2, Fig. 3b).

In Tg129M mice inoculated with the T120 or T121−20* variants, SD severity and brain regional distribution or lesion profile, did not significantly differ from those of Tg129V mice (Fig. 2a, d, and Additional file 3: Figure S3 A and B) although vacuoles were significantly larger (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2a, e). Mice challenged with T121 were free of lesions up to ~ 700 dpi (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Lesion profiles and vacuole size in second passage Tg129M mice challenged with T120 and T121−20* overlapped with those of the first passage (data not shown).

In T120 Tg129M, PrP IHC pattern with granular aggregates in the cerebral and cerebellar cortices mirrored that of matching Tg129V, while T121−20* Tg mice showed rare granular aggregates in subcortical regions but not in the cerebral cortex and cerebellum (Fig. 3a, b). No plaques were detected (Table 2 and Fig. 3b).

Following T2 inoculation, both Tg129V and Tg129M mice showed scant SD that, contrary to T1 variants, displayed an inversed severity gradient that increased progressively from the cerebral cortex, where it was virtually absent, to the thalamus (Table 2, Fig. 2a, c). Furthermore, SD was made of small vacuoles. In the cerebellum, astrogliosis also was significantly more severe than that observed in mice inoculated with T1 variants (Additional file 3: Figure S3 C and E) although granule cell depopulation did not reach statistical significance (Additional file 3: Figure S3D and E). PrP IHC showed plaques-like aggregates in the cerebral cortex of the Tg129V mice while real plaques were seen only in the brain stem and septal nuclei in one mouse (Figs. 3 and Additional file 4: S4). By contrast, plaques were widespread in Tg129M mice and populated the cerebral cortex, thalamus, the border between the hippocampal alveus and the corpus callosum, the brain stem and cerebellum in the majority (70%) of the inoculated mice (Figs. 3 and Additional file 4: S4).

Discussion

Previous transmission studies to Tg mice expressing human wild-type or mutated PrP did not examine the mouse replications of the sCJDVV1 T1 variants that we have recently described [4, 12, 13, 16, 21, 24, 26, 34, 45]. We now show that T120 and T121 are faithfully reproduced in Tg129V mice with no significantly different incubation periods and slightly different histotypes reminiscent of that associated with the -VV1 subtype (Tables 1, 2). Transmissibility characteristics clearly distinguished T120 from T121 following inoculation to the Tg129M mice where T120 accumulated as T121−20* whereas T121 was not detected.

T120 and T121−20* transmission to Tg129M required an incubation period nearly 60% longer than that of the Tg129V mice consistent with the effect of the 129 genotype barrier. This assumption is further supported by the significant reduction in the incubation period following second passage in Tg129M with T120 and T121−20* (Tables 1 and Additional file 5: S2). A similar phenomenon has been observed following second passage of sCJDVV1 prions to Tg129M mice [12].

In contrast to the accurate reproduction of the T120 and T121 variants, T121−20* inoculated to Tg129V mice accumulated as T121. Conversely, Tg129M mice faithfully accumulated T121−20*; both mouse lines accumulated T121−20* with the additional presence of T2 traces (also present in the inoculum) which may have impacted the replication. The two T121−20* variants generated in Tg129M following inoculation of T120 and T121−20*, respectively, had significantly different incubation period on second passage and differed in the histotype based on the lack of cerebral cortical and cerebellar pathology in the latter. Furthermore, second passage in Tg129M mice confirmed the lack of transmission of T121. An unexpected phenotypical distinction between T1 inoculated Tg129V and− 129M mice was the size of the vacuoles, which was significantly larger in the Tg129M mice consistent with an effect of the PrP 129MV polymorphism on this distinctive histopathological feature. Vacuole size and lesion profiles were virtually identically in Tg129M mice of the 1st and 2nd passage.

Transmission of sCJDVV2 T2 used as control revealed expected results. In contrast to the faithful replication of -VV2 T2 by the Tg129V mice, a T120 variant was reproduced in the Tg129M after an incubation period that was three times longer than that in Tg129V. Our data resemble those recently described in a transmission study employing the same Tg129M mouse line as in our study [12]. These findings confirm the incompetence of human PrPC-129M to reproduce -VV2 T2 [12, 24] as opposed to the faithful transmission of -MM2 to Tg129M mice [30, 34].

The original classification of major sCJD subtypes based on histotype and PrPD characteristics has undergone recent revisions [2, 11, 12, 27, 32, 43]. Sporadic CJDMM(MV)1 (a combination of -MM1 and -MV1, which share histotype and PrPD characteristics) as well as -MM2 (also referred to as MM2C) and -VV2, are seen as definitely distinct subtypes [5, 18, 19, 32]. They are associated with PrPD variants that show distinct conformational and transmissible characteristics but have straightforward electrophoretic profiles of either PrPD type 1 or 2. By contrast, the -MV2 and -VV1 subtypes have shown considerable electrophoretic heterogeneity [11, 32, 33]. The subtype -MV2 is now subdivided into two variants; the first, -MV2C, is currently viewed as a phenocopy of -MM2 in terms of histotype and PrPD characteristics; the second, -MV2K, is characterized by the presence of kuru (K) plaques and heterogeneous PrPD inclusive of at least two components: (i) a ~ 19 kDa PrPD variant with gel mobility and conformational features similar to the -VV2 ~ 19 kDa, and (ii) a ~ 20 kDa PrPD (also termed “intermediate” type or “type i”) of uncertain origin. Recently, however, the convergence of transmission and mass spectrometry data basically indicates that (i) the -MV2C and -MV2K phenotypes and respective PrPD characteristics are directly related to the representation of the resPrPD-129M and -129V components, respectively [32], (ii) the -MV2K ~ 20 kDa variant is made exclusively of the minority resPrPD-129 M component, and (iii) the -MV2K ~ 20 kDa appears to be an adaptation of the VV2 PrPD type 2 to the 129MM or 129MV background ([24, 25, 32] and this study).

Our previous study showed that in sCJDVV1 resPrPD presents an even higher level of complexity given that it features three combinations of resPrPD kDa: T120, T121 and T121−20 [11]. The T120 and T121 difference of ~ 1 kDa in electrophoretic mobility of the two resPrPD variants, although minor, is not negligible since it implies that the span of the PK-resistant region (i.e., the abnormal secondary structure generated during the PrPC to PrPD conversion) is different in the T120 and T121 variants. Indeed, T120 and T121 isolated from sCJDVV1 brains show features (e.g., resistance to enzymatic degradation by PK and propensity to unfold following exposure to the denaturing agent guanidine hydrochloride) that differ significantly, which further supports the conclusion that these two T1 variants have distinct conformational characteristics even though they are associated with similar histotypes [11]. It is noteworthy that the association of conformationally distinct prions strains with similar phenotypes has been previously reported [1, 44]. Our present findings are consistent with this conclusion given that both T120 and T121 can be faithfully replicated in Tg129V mice but display opposite transmission characteristic in Tg129M mice; furthermore, mimicking sCJDVV1, T120 and T121 are associated with essentially similar histotypes in the Tg mice.

Our study also offers the opportunity to directly compare the histotype of the T120 variant associated with -VV1 with that of the T120 variant generated after inoculation of -MV2K and -VV2 PrPD to Tg129M mice [24, 25]. Tg129M mice inoculated with T120 from -VV1 subjects are characterized by medium size vacuole SD, predominantly impacting the cerebral cortex, and lack of PrP plaques. By contrast, Tg129M inoculated with -MV2K and -VV2 isolates (also reported to harbor a T120 variant) [24] displayed ubiquitous plaques along with small vacuole SD occupying mostly subcortical regions. These two distinct histotypes are thus reminiscent of the -VV1 and -MV2K/-VV2 subtypes, respectively. The nature of the molecular features—besides the M and V incongruity at PrP residue 129—underpinning the complex and major impact on the histotype associated with the two T120 variants, remains to be resolved.

Conclusions

The present study further contributes to understand the molecular features of T1 variants in sCJDVV1 [11]. Our present data along with the previous conformational studies are consistent with the conclusion that T121 and T120 resPrPD are two distinct human prion strains that generate similar clinico-histopathological phenotypes. The lack of transmissibility of T121 VV1 to Tg129M mice suggests that subjects with the PrP-129MM genotype may not be at risk of acquiring prion disease from sCJDVV1 donor harboring the T121 variant. Understanding the molecular properties of PrPD T1 associated with sCJDVV1 may shed light into the common early presentation of this subtype and be essential for strain-sensitive therapeutic approaches [3, 15, 20, 29].

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Fig. S1: Western blot profile of resPrPD from sCJDVV cases used as inocula. A: Immunoblot with 3F4 antibody. Lane 1–3: One of the three sCJDVV1 inocula with T1 unglycosylated (unglyc.) isoform migrating to ~ 20 kDa (VV120, lane 1), and sCJDVV2 with T2 unglyc. resPrPD of ~ 19 kDa (VV2, lanes 2, 3). Lane 4: sCJDVV1 with T1 resPrPD migrating to ~21 kDa (VV121). Lane 5: sCJDVV1-2 control with co-existing T121 and T2 resPrPD fragments. Lane 6: sCJDVV1-2 inoculum (VV121–20*) harboring a ~ 21–20 kDa doublet with prominent ~21 kDa band; T2 is not detected by 3F4. Lane 7: sCJDVV2 control. B: Immunoblot with 1E4 antibody. Lanes 1-4: 1E4 immunoreacted with T1 populating VV120 (lane 1) and VV121 (lane 3) inocula, and T2 harvested from VV2 (lanes 2 & 4). Lane 5: 1E4 detected a faint band of ~19 kDa in addition to the ~21-20 kDa doublet in VV121–20*. Put.: putamen; CC: cerebral cortex.

Additional file 2. Fig. S2: Characterization of mouse brain resPrPD following 2nd passage in Tg129M mice. T1 and its superscript atop the blot refer to the mouse resPrPD T1 variant; VV120 and VV121 refer to resPrPD harvested from sCJDVV1 controls. Mouse resPrPD showing a ~21–20 kDa doublet following 2nd passage with VV120 (lanes 2 & 3) and VV121–20* (lanes 5 & 6); lane 6: longer exposure time of resPrPD visualized in lane 5. No resPrPD was detected after serial passage with VV121 (lane 7); Neg.: negative. Licor near-infrared (lanes 1-6); chemiluminescence (lanes 7 & 8).

Additional file 3 Fig. S3: Lesions profiles and assessment of cerebellar pathological changes. A and B: Tg129V and Tg129M mice challenged with sCJD VV120 (A) or VV121–20* (B) generated similar lesion profiles. C and D: Severity scores of gliosis (C) and neuronal loss (D) in the granule cell layer of the cerebellum in mice challenged with sCJD VV120, VV121, VV121–20* (averaged values) and VV2. E: Representative microphotographs showing gliosis and loss of granule cells in the cerebellum of Tg129V mice challenged with VV120 and VV2, respectively; arrows: astrocytes; *P<0.05. **P<0.02. Each point of the profile in A and B, and bar graphs in C and D are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Additional file 4 Fig. S4: Histopathology and PrP immunohistochemistry (IHC) in mice inoculated with sCJDVV2. i and iii: H.E. staining; ii and iv: PrP IHC. 1st row, i and ii: The cerebral cortex (CC), alveus (alv) and hippocampal CA1 regions were free of plaques and generated a negative PrP immunostaining. iii and iv: An aggregate (arrow) visible at H.E. (iii) was positively stained by an antibody (Ab) to PrP (iv). 2nd row, i and ii: Aggregates of plaques (i) affecting the lower brainstem immunoreacted with an Ab to PrP (ii); inset, i: higher magnification of congregate plaques. iii and iv: Plaques (arrowheads) distributed in a diagonal row in the upper brainstem; inset, iii and iv: a rounded plaque. Scale bar insets: 100 µm (1st row, iv) and 20 µm (2nd row, i); Ab: 3F4.

Acknowledgements

We thank the NPDPSC, in particular Diane Kofskey for her invaluable technical assistance. We gratefully acknowledge Rabeah Bayazid for her skillful assistance.

Abbreviations

- CJD

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

- sCJD

Sporadic CJD

- T1

Type 1

- T2

Type 2

- PrP

Prion protein

- PrPD

Disease-associated PrP

- PK

Proteinase K

- resPrPD

PK-resistant PrPD

- T121 and T120

T1 variants with unglycosylated resPrPD isoform of ~ 21 and ~ 20 kDa, respectively

- T121−20

T1 variant with unglycosylated resPrPD doublet of~ 21–20 kDa

- VV121, VV120 and VV121−20*

Shown in all figures and Tables 1 and 2 refer to the human sCJDVV cases

- M

Methionine

- V

Valine

- Tg129V and Tg129M

Transgenic mice expressing PrP-129V and PrP-129M, respectively

- Ab

Antibody

- BH

Brain homogenate

- H.E.

Hematoxylin–eosin staining

- PrP IHC

PrP immunostaining or immunohistochemistry

- SD

Spongiform degeneration

- WB

Western blot

- dpi

Days post-inoculation

Authors' contributions

IC and PG conceived and designed the experiments. IC, JCE and RA performed western blot analyses. IC characterized the histotype. JCE and AMM performed inoculations, monitored and culled the mice. IC, JCE, AMM, RA, SKN, MVC, BSA, and JMT were responsible for data analysis and acquisition. TK contributed materials. IC and PG wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded in part by the Alliance BioSecure Research Foundation [FABS FRM-2014 to J.M.T], Spanish Ministerio de Economía Industria y Competitividad [AGL2016-78054-R (AEI/FEDER, UE) to J.M.T. and J.C.E], Fundació La Marató de TV3 [201821-30-31-32 to J.C.E] and AMM was supported by Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Tecnología Agraria y Agroalimentaria [fellowship INIA-FPI-SGIT-2015–02]. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 NS083687 and the Charles S. Britton Fund. to P. Gambetti, by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases P01 AI077774 grant to C. Soto, and by the K99/R00 AG068359 to I. Cali. As a trainee of the research education component (REC) of the Cleveland Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (CADRC), the work of I. Cali was also supported by the NIA P30 AG062428 01. The National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center is funded by CDC (NU38CK00048).

Availability of data and materials

Data used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Compliance with ethical standards

Competing of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Consent for publication

All authors agree for submitting this manuscript to Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Animal experiments were conducted in strict accordance with the recommendations in the guidelines of the Code for Methods and Welfare Considerations in Behavioral Research with Animals and European directive 2010/63/EU. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering. Experiments were evaluated by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Spanish National Institute for the Agricultural and Food Research and Technology and approved by the General Directorate of the Madrid Community Government (permit nos. PROEX 181/16, PROEX 263/15 and PROEX 094/18).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ignazio Cali and Juan Carlos Espinosa contributed equally to this work

References

- 1.Aguilar-Calvo P, Xiao X, Bett C, Eraña H, Soldau K, Castilla J, Nilsson KPR, Surewicz WK, Sigurdson CJ. Post-translational modifications in PrP expand the conformational diversity of prions in vivo. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43295. doi: 10.1038/srep43295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baiardi S, Rossi M, Capellari S, Parchi P. Recent advances in the histo-molecular pathology of human prion disease. Brain Pathol. 2019;29:278–300. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry DB, Lu D, Geva M, Watts JC, Bhardwaj S, Oehler A, Renslo AR, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB, Giles K. Drug resistance confounding prion therapeutics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E4160–4169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317164110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bishop MT, Will RG, Manson JC. Defining sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease strains and their transmission properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:12005–12010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004688107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bizzi A, Pascuzzo R, Blevins J, Moscatelli MEM, Grisoli M, Lodi R, Doniselli FM, Castelli G, Cohen ML, Stamm A, Schonberger LB, Appleby BS, Gambetti P. Subtype diagnosis of sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease with diffusion MRI. Ann Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/ana.25983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonda DJ, Manjila S, Mehndiratta P, Khan F, Miller BR, Onwuzulike K, Puoti G, Cohen ML, Schonberger LB, Cali I. Human prion diseases: surgical lessons learned from iatrogenic prion transmission. Neurosurg Focus. 2016;41:E10. doi: 10.3171/2016.5.FOCUS15126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cali I, Castellani R, Alshekhlee A, Cohen Y, Blevins J, Yuan J, Langeveld JPM, Parchi P, Safar JG, Zou W-Q, Gambetti P. Co-existence of scrapie prion protein types 1 and 2 in sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: its effect on the phenotype and prion-type characteristics. Brain. 2009;132:2643–2658. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cali I, Castellani R, Yuan J, Al-Shekhlee A, Cohen ML, Xiao X, Moleres FJ, Parchi P, Zou W-Q, Gambetti P. Classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease revisited. Brain. 2006;129:2266–2277. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cali I, Cohen ML, Haїk S, Parchi P, Giaccone G, Collins SJ, Kofskey D, Wang H, McLean CA, Brandel J-P, Privat N, Sazdovitch V, Duyckaerts C, Kitamoto T, Belay ED, Maddox RA, Tagliavini F, Pocchiari M, Leschek E, Appleby BS, Safar JG, Schonberger LB, Gambetti P. Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease with Amyloid-β pathology: an international study. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2018;6:5. doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0503-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cali I, Lavrich J, Moda F, Kofskey D, Nemani SK, Appleby B, Tagliavini F, Soto C, Gambetti P, Notari S. PMCA-replicated PrPD in urine of vCJD patients maintains infectivity and strain characteristics of brain PrPD: Transmission study. Sci Rep. 2019;9:5191. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41694-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cali I, Puoti G, Smucny J, Curtiss PM, Cracco L, Kitamoto T, Occhipinti R, Cohen ML, Appleby BS, Gambetti P. Co-existence of PrPD types 1 and 2 in sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease of the VV subgroup: phenotypic and prion protein characteristics. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1503. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58446-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassard H, Huor A, Espinosa J-C, Douet J-Y, Lugan S, Aron N, Vilette D, Delisle M-B, Marín-Moreno A, Peran P, Beringue V, Torres JM, Ironside JW, Andreoletti O. Prions from sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease patients propagate as strain mixtures. mBio. 2020 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00393-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapuis J, Moudjou M, Reine F, Herzog L, Jaumain E, Chapuis C, Quadrio I, Boulliat J, Perret-Liaudet A, Dron M, Laude H, Rezaei H, Béringue V. Emergence of two prion subtypes in ovine PrP transgenic mice infected with human MM2-cortical Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease prions. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2016;4:10. doi: 10.1186/s40478-016-0284-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi J-K, Cali I, Surewicz K, Kong Q, Gambetti P, Surewicz WK. Amyloid fibrils from the N-terminal prion protein fragment are infectious. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:13851–13856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1610716113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cronier S, Beringue V, Bellon A, Peyrin J-M, Laude H. Prion strain- and species-dependent effects of antiprion molecules in primary neuronal cultures. J Virol. 2007;81:13794–13800. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01502-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernández-Borges N, Espinosa JC, Marín-Moreno A, Aguilar-Calvo P, Asante EA, Kitamoto T, Mohri S, Andréoletti O, Torres JM. Protective effect of Val129-PrP against bovine spongiform encephalopathy but not variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:1522–1530. doi: 10.3201/eid2309.161948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gambetti P, Cali I, Notari S, Kong Q, Zou W-Q, Surewicz WK. Molecular biology and pathology of prion strains in sporadic human prion diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:79–90. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0761-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gambetti P, Kong Q, Zou W, Parchi P, Chen SG. Sporadic and familial CJD: classification and characterisation. Br Med Bull. 2003;66:213–239. doi: 10.1093/bmb/66.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gambetti P, Notari S. Human sporadic prion diseases. In: Zou W-Q, Gambetti P, editors. Prions and Diseases. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giles K, Olson SH, Prusiner SB. Developing therapeutics for PrP prion diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a023747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaumain E, Quadrio I, Herzog L, Reine F, Rezaei H, Andréoletti O, Laude H, Perret-Liaudet A, Haïk S, Béringue V. Absence of evidence for a causal link between bovine spongiform encephalopathy strain variant L-BSE and known forms of sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in human PrP transgenic mice. J Virol. 2016;90:10867–10874. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01383-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kascsak RJ, Rubenstein R, Merz PA, Tonna-DeMasi M, Fersko R, Carp RI, Wisniewski HM, Diringer H. Mouse polyclonal and monoclonal antibody to scrapie-associated fibril proteins. J Virol. 1987;61:3688–3693. doi: 10.1128/JVI.61.12.3688-3693.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim M-O, Cali I, Oehler A, Fong JC, Wong K, See T, Katz JS, Gambetti P, Bettcher BM, Dearmond SJ, Geschwind MD. Genetic CJD with a novel E200G mutation in the prion protein gene and comparison with E200K mutation cases. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2013;1:80. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-1-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi A, Asano M, Mohri S, Kitamoto T. Cross-sequence transmission of sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease creates a new prion strain. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30022–30028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi A, Iwasaki Y, Otsuka H, Yamada M, Yoshida M, Matsuura Y, Mohri S, Kitamoto T. Deciphering the pathogenesis of sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease with codon 129 M/V and type 2 abnormal prion protein. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2013;1:74. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-1-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi A, Parchi P, Yamada M, Brown P, Saverioni D, Matsuura Y, Takeuchi A, Mohri S, Kitamoto T. Transmission properties of atypical Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: a clue to disease etiology? J Virol. 2015;89:3939–3946. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03183-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi A, Parchi P, Yamada M, Mohri S, Kitamoto T. Neuropathological and biochemical criteria to identify acquired Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease among presumed sporadic cases. Neuropathology. 2016;36:305–310. doi: 10.1111/neup.12270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobayashi A, Sakuma N, Matsuura Y, Mohri S, Aguzzi A, Kitamoto T. Experimental verification of a traceback phenomenon in prion infection. J Virol. 2010;84:3230–3238. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02387-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marín-Moreno A, Aguilar-Calvo P, Pitarch JL, Espinosa JC, Torres JM. Nonpathogenic heterologous prions can interfere with prion infection in a strain-dependent manner. J Virol. 2018 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01086-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moda F, Suardi S, Di Fede G, Indaco A, Limido L, Vimercati C, Ruggerone M, Campagnani I, Langeveld J, Terruzzi A, Brambilla A, Zerbi P, Fociani P, Bishop MT, Will RG, Manson JC, Giaccone G, Tagliavini F. MM2-thalamic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: neuropathological, biochemical and transmission studies identify a distinctive prion strain. Brain Pathol. 2012;22:662–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2012.00572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monari L, Chen SG, Brown P, Parchi P, Petersen RB, Mikol J, Gray F, Cortelli P, Montagna P, Ghetti B. Fatal familial insomnia and familial Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: different prion proteins determined by a DNA polymorphism. PNAS. 1994;91:2839–2842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nemani SK, Xiao X, Cali I, Cracco L, Puoti G, Nigro M, Lavrich J, Bharara Singh A, Appleby BS, Sim VL, Notari S, Surewicz WK, Gambetti P. A novel mechanism of phenotypic heterogeneity in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2020;8:85. doi: 10.1186/s40478-020-00966-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Notari S, Capellari S, Giese A, Westner I, Baruzzi A, Ghetti B, Gambetti P, Kretzschmar HA, Parchi P. Effects of different experimental conditions on the PrPSc core generated by protease digestion: implications for strain typing and molecular classification of CJD. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16797–16804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313220200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Notari S, Xiao X, Espinosa JC, Cohen Y, Qing L, Aguilar-Calvo P, Kofskey D, Cali I, Cracco L, Kong Q, Torres JM, Zou W, Gambetti P. Transmission characteristics of variably protease-sensitive prionopathy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:2006–2014. doi: 10.3201/eid2012.140548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Padilla D, Béringue V, Espinosa JC, Andreoletti O, Jaumain E, Reine F, Herzog L, Gutierrez-Adan A, Pintado B, Laude H, Torres JM. Sheep and goat BSE propagate more efficiently than cattle BSE in human PrP transgenic mice. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001319. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parchi P, Capellari S, Chen SG, Petersen RB, Gambetti P, Kopp N, Brown P, Kitamoto T, Tateishi J, Giese A, Kretzschmar H. Typing prion isoforms. Nature. 1997;386:232–233. doi: 10.1038/386232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parchi P, Capellari S, Chin S, Schwarz HB, Schecter NP, Butts JD, Hudkins P, Burns DK, Powers JM, Gambetti P. A subtype of sporadic prion disease mimicking fatal familial insomnia. Neurology. 1999;52:1757–1763. doi: 10.1212/WNL.52.9.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parchi P, Giese A, Capellari S, Brown P, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Windl O, Zerr I, Budka H, Kopp N, Piccardo P, Poser S, Rojiani A, Streichemberger N, Julien J, Vital C, Ghetti B, Gambetti P, Kretzschmar H. Classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease based on molecular and phenotypic analysis of 300 subjects. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:224–233. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199908)46:2<224::AID-ANA12>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parchi P, Strammiello R, Notari S, Giese A, Langeveld JPM, Ladogana A, Zerr I, Roncaroli F, Cras P, Ghetti B, Pocchiari M, Kretzschmar H, Capellari S. Incidence and spectrum of sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease variants with mixed phenotype and co-occurrence of PrPSc types: an updated classification. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:659–671. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0585-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parchi P, Zou W, Wang W, Brown P, Capellari S, Ghetti B, Kopp N, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ, Kretzschmar HA, Head MW, Ironside JW, Gambetti P, Chen SG. Genetic influence on the structural variations of the abnormal prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10168–10172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.18.10168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puoti G, Bizzi A, Forloni G, Safar JG, Tagliavini F, Gambetti P. Sporadic human prion diseases: molecular insights and diagnosis. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:618–628. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rossi M, Baiardi S, Parchi P. Understanding prion strains: evidence from studies of the disease forms affecting humans. Viruses. 2019 doi: 10.3390/v11040309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rossi M, Saverioni D, Di Bari M, Baiardi S, Lemstra AW, Pirisinu L, Capellari S, Rozemuller A, Nonno R, Parchi P. Atypical Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease with PrP-amyloid plaques in white matter: molecular characterization and transmission to bank voles show the M1 strain signature. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5:87. doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0496-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sigurdson CJ, Nilsson KPR, Hornemann S, Manco G, Polymenidou M, Schwarz P, Leclerc M, Hammarström P, Wüthrich K, Aguzzi A. Prion strain discrimination using luminescent conjugated polymers. Nat Methods. 2007;4:1023–1030. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watts JC, Giles K, Serban A, Patel S, Oehler A, Bhardwaj S, Guan S, Greicius MD, Miller BL, DeArmond SJ, Geschwind MD, Prusiner SB. Modulation of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease prion propagation by the A224V mutation. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:540–553. doi: 10.1002/ana.24463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zerr I, Kallenberg K, Summers DM, Romero C, Taratuto A, Heinemann U, Breithaupt M, Varges D, Meissner B, Ladogana A, Schuur M, Haik S, Collins SJ, Jansen GH, Stokin GB, Pimentel J, Hewer E, Collie D, Smith P, Roberts H, Brandel JP, van Duijn C, Pocchiari M, Begue C, Cras P, Will RG, Sanchez-Juan P. Updated clinical diagnostic criteria for sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Brain. 2009;132:2659–2668. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zou W-Q, Langeveld J, Xiao X, Chen S, McGeer PL, Yuan J, Payne MC, Kang H-E, McGeehan J, Sy M-S, Greenspan NS, Kaplan D, Wang G-X, Parchi P, Hoover E, Kneale G, Telling G, Surewicz WK, Kong Q, Guo J-P. PrP conformational transitions alter species preference of a PrP-specific antibody. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13874–13884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Fig. S1: Western blot profile of resPrPD from sCJDVV cases used as inocula. A: Immunoblot with 3F4 antibody. Lane 1–3: One of the three sCJDVV1 inocula with T1 unglycosylated (unglyc.) isoform migrating to ~ 20 kDa (VV120, lane 1), and sCJDVV2 with T2 unglyc. resPrPD of ~ 19 kDa (VV2, lanes 2, 3). Lane 4: sCJDVV1 with T1 resPrPD migrating to ~21 kDa (VV121). Lane 5: sCJDVV1-2 control with co-existing T121 and T2 resPrPD fragments. Lane 6: sCJDVV1-2 inoculum (VV121–20*) harboring a ~ 21–20 kDa doublet with prominent ~21 kDa band; T2 is not detected by 3F4. Lane 7: sCJDVV2 control. B: Immunoblot with 1E4 antibody. Lanes 1-4: 1E4 immunoreacted with T1 populating VV120 (lane 1) and VV121 (lane 3) inocula, and T2 harvested from VV2 (lanes 2 & 4). Lane 5: 1E4 detected a faint band of ~19 kDa in addition to the ~21-20 kDa doublet in VV121–20*. Put.: putamen; CC: cerebral cortex.

Additional file 2. Fig. S2: Characterization of mouse brain resPrPD following 2nd passage in Tg129M mice. T1 and its superscript atop the blot refer to the mouse resPrPD T1 variant; VV120 and VV121 refer to resPrPD harvested from sCJDVV1 controls. Mouse resPrPD showing a ~21–20 kDa doublet following 2nd passage with VV120 (lanes 2 & 3) and VV121–20* (lanes 5 & 6); lane 6: longer exposure time of resPrPD visualized in lane 5. No resPrPD was detected after serial passage with VV121 (lane 7); Neg.: negative. Licor near-infrared (lanes 1-6); chemiluminescence (lanes 7 & 8).

Additional file 3 Fig. S3: Lesions profiles and assessment of cerebellar pathological changes. A and B: Tg129V and Tg129M mice challenged with sCJD VV120 (A) or VV121–20* (B) generated similar lesion profiles. C and D: Severity scores of gliosis (C) and neuronal loss (D) in the granule cell layer of the cerebellum in mice challenged with sCJD VV120, VV121, VV121–20* (averaged values) and VV2. E: Representative microphotographs showing gliosis and loss of granule cells in the cerebellum of Tg129V mice challenged with VV120 and VV2, respectively; arrows: astrocytes; *P<0.05. **P<0.02. Each point of the profile in A and B, and bar graphs in C and D are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Additional file 4 Fig. S4: Histopathology and PrP immunohistochemistry (IHC) in mice inoculated with sCJDVV2. i and iii: H.E. staining; ii and iv: PrP IHC. 1st row, i and ii: The cerebral cortex (CC), alveus (alv) and hippocampal CA1 regions were free of plaques and generated a negative PrP immunostaining. iii and iv: An aggregate (arrow) visible at H.E. (iii) was positively stained by an antibody (Ab) to PrP (iv). 2nd row, i and ii: Aggregates of plaques (i) affecting the lower brainstem immunoreacted with an Ab to PrP (ii); inset, i: higher magnification of congregate plaques. iii and iv: Plaques (arrowheads) distributed in a diagonal row in the upper brainstem; inset, iii and iv: a rounded plaque. Scale bar insets: 100 µm (1st row, iv) and 20 µm (2nd row, i); Ab: 3F4.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.