Summary

Gpr52 is an orphan G-protein-coupled receptor of unknown physiological function. We found that Gpr52-deficient (Gpr52−/−) mice exhibit leanness associated with reduced liver weight, decreased hepatic de novo lipogenesis, and enhanced insulin sensitivity. Treatment of the hepatoma cell line HepG2 cells with c11, the synthetic GPR52 agonist, increased fatty acid biosynthesis, and GPR52 knockdown (KD) abolished the lipogenic action of c11. In addition, c11 induced the expressions of lipogenic enzymes (SCD1 and ELOVL6), whereas these inductions were attenuated by GPR52-KD. In contrast, cholesterol biosynthesis was not increased by c11, but its basal level was significantly suppressed by GPR52-KD. High-fat diet (HFD)-induced increase in hepatic expression of Pparg2 and its targets (Scd1 and Elovl6) was absent in Gpr52−/− mice with alleviated hepatosteatosis. Our present study showed that hepatic GPR52 promotes the biosynthesis of fatty acid and cholesterol in a ligand-dependent and a constitutive manner, respectively, and Gpr52 participates in HFD-induced fatty acid synthesis in liver.

Subject areas: Human Metabolism, Molecular Biology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Hepatosteatosis is inherently an adaptive response to overnutrition to store energy

-

•

On the other hand, it can be a pathological condition causing insulin resistance

-

•

High-fat diet increases PPARγ2 expression and lipogenesis in liver via GPR52

-

•

Gpr52 ablation protects mice from developing hepatosteatosis and insulin resistance

Human Metabolism; Molecular Biology

Introduction

G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) comprise numerous receptor proteins on the plasma membrane that share the common structural feature of having seven transmembrane domains (Gusach et al., 2020; Hilger et al., 2018; Ritter and Hall, 2009; Wootten et al., 2018). GPCRs are known to regulate various cellular functions by coupling with intracellular partners including canonical transducer proteins (i.e., heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins) and scaffolding proteins (e.g., arrestins, PDZ scaffolds, and non-PDZ scaffolds) (Wootten et al., 2018). Structurally and evolutionarily, GPCRs are classified into several subfamilies including class A (rhodopsin-like), class B1 (secretin receptor-like), class B2 (adhesion receptors), class C (metabotropic glutamate receptor-like), and class F (frizzled-like) subfamilies.

In humans, more than 800 GPCR genes have been identified, and a variety of molecules have been found to act as their ligands. These include hormones, neurotransmitters, ions, photons, odorants, and fatty acids; binding of each ligand to its corresponding GPCR evokes unique GPCR signaling. However, specific ligands have not been identified for many GPCRs; such GPCRs are known as orphan GPCRs (Wootten et al., 2018). GPR52 is one such class A orphan GPCR, which constitutively activates adenylyl cyclase without inhibiting forskolin-stimulated cAMP elevation, as is the case with GPR3, GPR21, and GPR65 (Martin et al., 2015). Precise analysis of its expression pattern in the brain revealed that GPR52 is abundantly expressed in the striatum, where it is co-localized with dopamine D1 (DRD1) and/or D2 (DRD2) receptors (Komatsu et al., 2014). hGPR52-expressing transgenic mice exhibit decreased methamphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion, whereas Gpr52 knockout mice (Gpr52−/− mice) exhibit psychosis-related behaviors, suggesting that GPR52 is involved in modulating cognitive function and emotion through dopamine signaling (Komatsu et al., 2014).

To clarify the physiological role of Gpr52, we generated Gpr52−/− mice and found that Gpr52−/− mice weighed less and showed reduced fat and liver weight, suggesting that Gpr52 is involved in the regulation of energy metabolism. Gpr52−/− mice also showed increased insulin sensitivity as assessed by insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation. As these knockout mice exhibited neither hyperlocomotion nor hypophagia, involvement of Gpr52 expressed in tissues other than the brain was implicated. To ascertain its relevance, we examined the tissue expression pattern of GPR52 in human cDNAs; unexpectedly, considerable GPR52 expression was noted in the liver. Functional analyses of GPR52 using Gpr52−/− liver and GPR52-knocked down HepG2 cells revealed that hepatocyte GPR52 regulates the biosynthesis of fatty acid in the liver and contributes to the acceleration of hepatosteatosis in response to excessive fat intake in mice.

Results

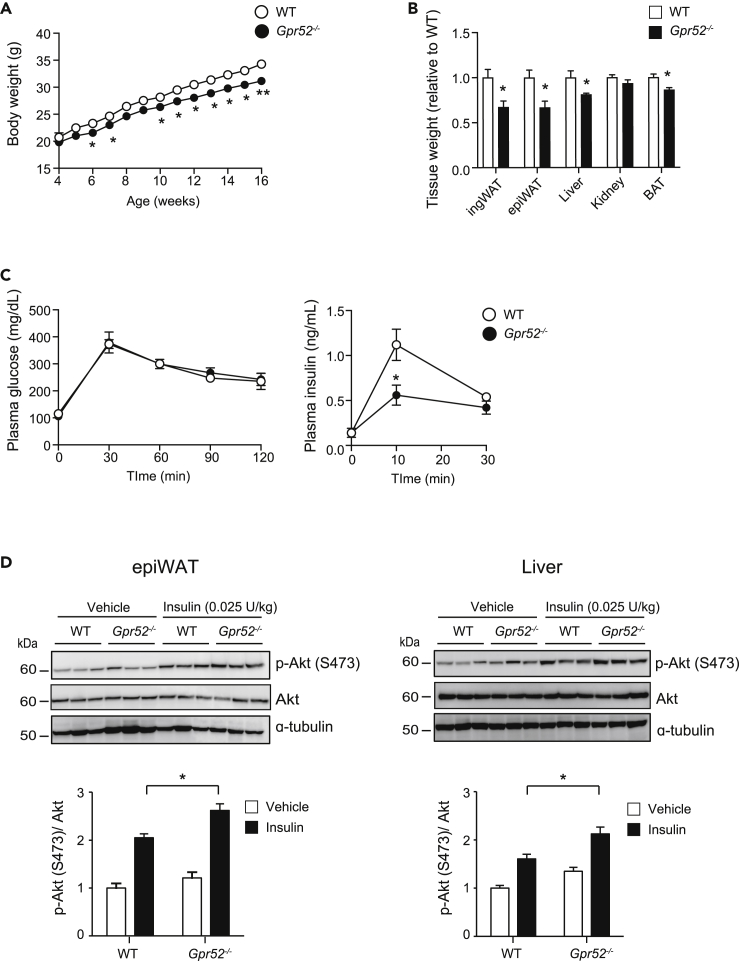

Gpr52−/− mice exhibit reduced adiposity

To clarify the physiological role of GPR52, we generated Gpr52−/− mice (Figure S1A). Although these mice display no gross physical abnormalities and are fertile, their body weight was significantly less than that of wild-type (WT) mice. Gpr52−/− mice showed reduced adiposity manifested in reduced body weight and the reduced tissue weight of inguinal white adipose tissue (ingWAT), epididymal WAT (epiWAT), and brown adipose tissue (BAT) together with unchanged body length (Figures 1A, 1B, and S1B). In addition, liver weight was significantly reduced in Gpr52−/− mice. As food intake and locomotor activity (Figures S1C and S1D) did not differ between Gpr52−/− and WT mice, the leanness of Gpr52−/− mice is unlikely to be due to the decreased energy intake and/or the increased energy consumption associated with hyper-locomotive activity.

Figure 1.

Gpr52-/- mice exhibit leanness associated with increased insulin sensitivity

(A) Changes in body weight of Gpr52-/- and WT mice (n = 5).

(B) Tissue weight of Gpr52-/- and WT mice (n = 7, 19 weeks old).

(C) OGTT (2 g/kg) in Gpr52-/- and WT mice. Plasma glucose (left) and insulin (right) concentrations are plotted at the indicated time points (n = 5, 17 weeks old).

(D) Representative western blot analysis of p-Akt (S473) level (upper), Akt (middle), and α-tubulin (lower) of epiWAT (left) and liver (right). The ratio of p-Akt (S473) level to Akt was quantified in the graphs.

Data are means ± SEM. ∗p <0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, between the animal groups by unpaired Student’s t test. See also Figure S1.

Gpr52−/− mice exhibit enhanced insulin sensitivity

As Gpr52−/− mice show significantly decreased tissue weight of adipose tissues and liver, the two principal insulin target tissues, we evaluated their insulin sensitivity. Although there was no significant difference in blood glucose levels under ad lib fed conditions, plasma insulin levels tended to be lower (p = 0.052) in Gpr52−/− mice (Figure S1E). Insulin sensitivity assessed by insulin tolerance test showed that the glucose lowering effect of exogenous insulin tended to be greater in Gpr52−/− mice (Figure S1F). Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) revealed that Gpr52−/− mice have normal glucose tolerance with significantly reduced insulin secretory response to glucose (Figure 1C), suggesting that Gpr52−/− mice have enhanced insulin sensitivity.

We then evaluated the insulin sensitivity of adipose tissue and liver of Gpr52−/− mice in vivo by quantifying Akt phosphorylation in response to exogenous insulin administration. Intravenous administration of insulin induced a significant increase in phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt) levels in epiWAT and liver of both Gpr52−/− and WT mice. However, the p-Akt/Akt ratio in these tissues after insulin treatment was significantly higher in Gpr52−/− mice than that in WT mice (Figure 1D), indicating that insulin sensitivity is enhanced in Gpr52−/− mice.

GPR52 is expressed in adipose tissue and liver in humans and mice

The lack of hypophagia or hyperlocomotion in Gpr52−/− mice suggested that their leanness may be attributable to dysfunction of Gpr52 expressed in tissues other than the brain. We therefore examined the tissue expression profile of GPR52 in humans (Figure 2A). As previously reported, GPR52 was found to be highly expressed in the human brain, but was also expressed in the liver (Figure 2A). In addition, GPR52 mRNA was expressed in the human hepatoma cell line HepG2 cells at a level similar to that in human liver, demonstrating that GPR52 is expressed in hepatocytes. In mouse tissues, Gpr52 was substantially expressed in the adipose tissues and liver (Figure 2B). qPCR experiment using mature adipocytes and stromal vascular fraction (SVF) isolated from epiWAT revealed that Gpr52 was expressed in mature adipocytes (Figure 2C). Based on these results, we hypothesized that Gpr52 expressed in adipocytes and/or hepatocytes plays a role in lipid metabolism.

Figure 2.

Gene expressions of the enzymes involved in biosynthesis of fatty acid and cholesterol were altered in metabolic tissues of Gpr52-/- mice

(A) GPR52 mRNA expression in various human tissues and HepG2 cells.

(B) Gpr52 mRNA expression in the brain, epiWAT, liver, skeletal muscle, and pancreatic islets of mice. (A and B) Expression levels are shown as relative values normalized to GAPDH (A) or Gapdh (B) (n = 3–4). The expressions in the brain are represented as 1.

(C) Gpr52 mRNA expression in the adipocyte and SVF in mice. Adiponectin (Adipoq) and F4/80 (Adgre1) are indicated as markers of adipocyte and SVF, respectively (n = 4).

(D) Gene expressions of the enzymes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis (Scd1, Elovl6, Acc1, Acc2, Dgat2, and Acss2) and cholesterol biosynthesis (Hmgcr) in metabolic tissues (ingWAT, epiWAT, BAT, and liver) of Gpr52-/- and WT mice under fed condition (n = 5, 19 weeks old). Data are means ± SEM. ∗p <0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, between the animal groups by unpaired Student’s t test.

Gene expressions of the enzymes involved in biosynthesis of fatty acid and cholesterol were altered in epiWAT and liver of Gpr52−/− mice

As fat depots and liver of Gpr52−/− mice weighed significantly less than those of WT mice, we hypothesized that de novo fatty acid synthesis in adipose tissues and/or liver might be decreased. We therefore quantified the mRNA expressions of genes involved in de novo lipid synthesis in ingWAT, epiWAT, BAT, and liver (Figure 2D). Contrary to our expectation, mRNA expressions of Scd1, Elovl6, and Acc1 of Gpr52−/− mice were not decreased in ingWAT, BAT, or liver, despite the lesser weight of these tissues in Gpr52−/− mice. Nevertheless, mRNA expressions of Scd1, Elovl6, and Acc1 of Gpr52−/− mice were significantly reduced in epiWAT. Among many de novo lipogenic enzymes, Scd1 (Dobrzyn et al., 2010), Elovl6 (Shimano, 2012), and Acc1 (Kim et al., 2017) have been reported to play critical roles in the regulation of fatty acid metabolism, suggesting that Gpr52 may be involved in the regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis.

Unexpectedly, mRNA expression of Hmgcr, the rate-limiting enzyme of cholesterol biosynthesis, was significantly decreased in Gpr52−/− liver. In addition, similar to the changes of Scd1, Elovl6, and Acc1 expressions, Hmgcr expression was significantly reduced in epiWAT, but not in ingWAT or BAT. These results suggest that Gpr52 may also participate in the regulation of cholesterol biosynthesis as well as that of fatty acid.

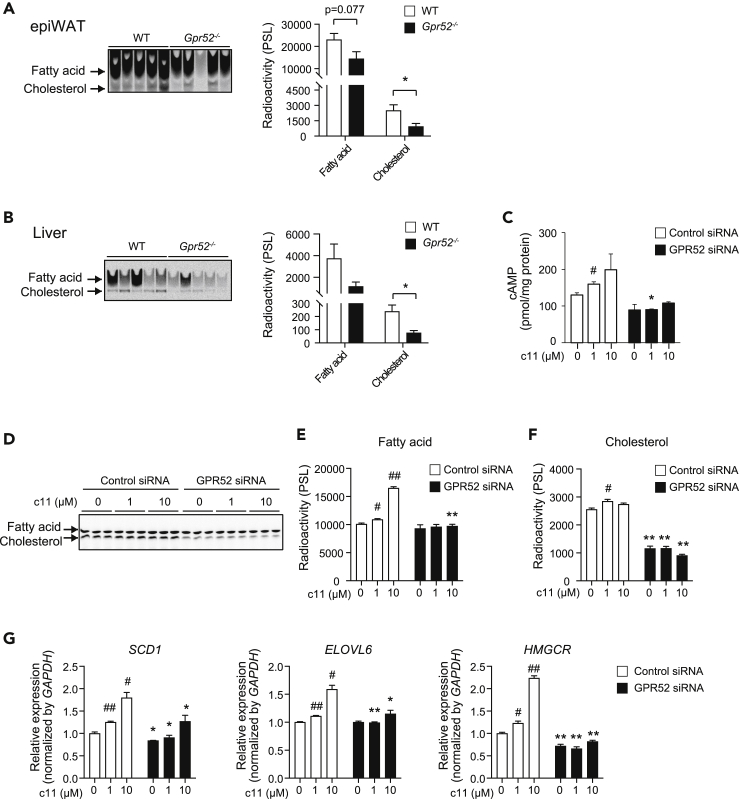

Gpr52 is involved in ex vivo synthesis of fatty acid and cholesterol in epiWAT and liver

Alteration of gene expressions of the enzymes of de novo synthesis of fatty acid and cholesterol in Gpr52−/− epiWAT and liver led us to examine their de novo synthesis ex vivo using 14C-acetate in organ culture (Figures 3A and 3B). In accord with the changes in mRNA expressions, de novo lipid synthesis of Gpr52−/− epiWAT tended to be low for fatty acid and was significantly reduced for cholesterol, when compared with those of WT epiWAT (p = 0.037). In addition, de novo lipid synthesis in liver of Gpr52−/− mice showed a similar tendency; de novo synthesis of both fatty acid (statistically insignificant) and cholesterol (p = 0.013) was decreased in Gpr52−/− mice. These results are compatible with our thesis that Gpr52 expressed in adipocytes and hepatocytes is involved in de novo synthesis of fatty acid and cholesterol.

Figure 3.

GPR52 is involved in de novo synthesis of fatty acid and cholesterol in mice tissues and a human hepatoma cell line

(A and B) Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) images of de novo synthesis of fatty acid and cholesterol labeled by 14C-acetate in epiWAT (A) and liver (B). The radioactivity (PSL: photostimulated luminescence) of fatty acid and cholesterol in Gpr52-/- and WT mice (n = 5) (right). Data are means ± SEM. ∗p <0.05, between the animal groups by unpaired Student's t test.

(C) The effect of GPR52 agonist c11 on cAMP production in HepG2 cells treated with GPR52 siRNA or control siRNA (n = 3). The cAMP levels were normalized by protein concentration.

(D) The effect of GPR52 agonist c11 on de novo synthesis of fatty acid and cholesterol in HepG2 cells treated with GPR52 siRNA or control siRNA indicated as TLC image (n = 3).

(E and F) The radioactivity (PSL) of fatty acid (E) and cholesterol (F) of TLC image.

(G) The effect of GPR52 agonist c11 on gene expressions of fatty acid and cholesterol biosynthesis in HepG2 cells treated with GPR52 siRNA or control siRNA (n = 3).

Data are means ± SEM. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, versus c11-untreated, control siRNA-treated cells by unpaired Student's t test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, versus control siRNA-treated, c11 treatment counterparts by unpaired Student's t test. See also Figure S2.

GPR52 expressed in HepG2 cells promotes fatty acid and cholesterol biosynthesis in a ligand-dependent- and constitutive manner, respectively

As GPR52 was expressed in HepG2 cells (Figure 2A), we elucidated the regulatory mechanism of de novo lipid synthesis by GPR52 using this cell line. In addition, we utilized the GPR52 agonist c11, which was established by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited as a specific agonist of GPR52 (Nakahata et al., 2018).

We first evaluated the pharmacological characteristics of c11. We transfected HEK293 cells with vehicle, GPR52, or GPR21. GPR21 is another orphan GPCR, which has the highest structural similarity to GPR52, and may have functional similarity to GPR52, because Gpr21 is expressed abundantly in the brain and its genetic disruption evokes leanness and enhanced insulin sensitivity in mice (Osborn et al., 2012). In accord with a previous report indicating that both GPR52 and GPR21 are constitutively active GPCRs (Martin et al., 2015), overexpression of either GPR52 or GPR21 was found to significantly upregulate the intracellular cAMP concentrations ([cAMP]i) (Figure S2B). Treatment of the cells with a higher concentration of c11 further increased the [cAMP]i levels in a dose-dependent manner in GPR52-expressing cells, but not in vehicle-transfected cells or in GPR21-expressing cells, supporting the previous report that c11 is a specific agonist of GPR52 (Figures S2A and S2B).

We then examined the effect of c11 on [cAMP]i in HepG2 cells treated with GPR52 siRNA (GPR52-KD HepG2) or control siRNA (Cont-HepG2) (Figures 3C and S2C). We found that c11 treatment increased [cAMP]i in Cont-HepG2, but that the response was attenuated in GPR52-KD HepG2, suggesting that the endogenous GPR52 is functional in the HepG2 cells.

In addition, GPR52-KD HepG2 and Cont-HepG2 were subjected to measurement of de novo lipogenesis using 14C-acetate (Figures 3D–3F). As with de novo fatty acid synthesis, c11 dose dependently increased such synthesis in Cont-HepG2 cells (Figure 3E). Although GPR52 knockdown did not affect its basal rate, c11-dependent increase in fatty acid synthesis was abolished in GPR52-KD HepG2 cells. In contrast, de novo cholesterol synthesis in Cont-HepG2 cells was not increased by c11; however, the basal rate was significantly suppressed by GPR52 knockdown (Figure 3F). These results suggest that hepatic GPR52 ligand dependently promotes fatty acid biosynthesis and constitutively upregulates cholesterol biosynthesis.

To clarify the mechanism of GPR52 action on lipid biosynthesis, we examined gene expression changes due to GPR52 knockdown in HepG2 cells (Figure 3G). We first quantified the expressions of SCD1 and ELOVL6, the genes for the two critical enzymes involved in the regulation of fatty acid metabolism. Interestingly, their expressions were increased by c11 in a dose-dependent manner in Cont-HepG2 cells, whereas the effect of c11 was significantly attenuated in GPR52-KD HepG2 cells. The trend of the changes of SCD1 and ELOVL6 expressions was compatible with that of de novo fatty acid synthesis in HepG2 cells. Taken together, these results indicate that ligand-dependent activation of GPR52 promotes de novo fatty acid synthesis at least in part by transactivating SCD1 and ELOVL6.

We also examined the expression of HMGCR, the gene for the rate-limiting enzyme of cholesterol biosynthesis (Figure 3G). In contrast to the lack of effect of c11 on de novo cholesterol synthesis in Cont-HepG2 cells, c11 dose dependently increased HMGCR expression, which was diminished in GPR52-KD HepG2 cells. Nevertheless, knockdown of GPR52 significantly decreased HMGCR expression. These results suggest that HMGCR expression is regulated by ligand stimulation of GPR52 as well as by the basal expression level of GPR52; the total rate of cholesterol biosynthesis may therefore be determined by enzymes other than HMGCR.

GPR52 accelerates fat accumulation in liver and induces insulin resistance in response to excessive fat intake

Gpr52−/− mice exhibited enhancement of insulin sensitivity and reduction of tissue weight and de novo lipogenic gene (Scd1, Elovl6, and Acc1) expressions in epiWAT. As Scd1 and Elovl6 are key regulators of lipid metabolism, we hypothesized that Gpr52−/− mice may have defective triglyceride accumulation in liver when exposed to excessive fat intake. We therefore treated Gpr52−/− mice with high-fat diet (HFD) and examined the levels of lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Although Gpr52−/− mice weighed less under normal chow diet, their HFD-induced body weight gain (18.3% after 10-week HFD feeding) was similar to that of WT mice (23.7%) as estimated by the relative increase by HFD feeding, suggesting that Gpr52−/− mice retain the capacity for developing diet-induced obesity (Figure 4A). However, the HFD-induced increase in fasting plasma insulin levels was significantly (p = 0.00012) less in Gpr52−/− mice than that in WT mice (Figure 4B), suggesting that Gpr52−/− mice are partially protected from diet-induced insulin resistance. Although plasma glucose levels during OGTT were only modestly lower in Gpr52−/− mice, their plasma insulin levels were significantly lower (Figure 4C), suggesting that insulin sensitivity was enhanced in Gpr52−/− mice under HFD. In addition, considering that Gpr52 is shown to be expressed also in pancreatic islets (Figure 2B), decreased insulin secretion in Gpr52−/− mice during OGTT might well reflect altered insulin secretion from pancreatic β cells. HFD feeding induced a significant increase in liver weight in both Gpr52−/− and WT mice; however, the liver weight was significantly (p = 0.0009) lower in Gpr52−/− mice than that in WT mice (Figure 4D). Under normal diet conditions, triglyceride content in liver was not statistically different between Gpr52−/− and WT mice (Figure 4D). However, under HFD feeding, the triglyceride content in Gpr52−/− liver was moderately, but significantly (p = 0.0001), lower than that in WT, suggesting that Gpr52 is involved in the development of diet-induced hepatosteatosis.

Figure 4.

Gpr52 accelerates fat accumulation in liver and induces insulin resistance in response to excessive fat intake

(A) Changes in body weight of Gpr52−/− and WT mice in HFD (n = 6–12).

(B) Plasma glucose (left) and insulin (right) concentrations of Gpr52−/− and WT mice in fed (n = 8–9) and fasted (n = 26–39) conditions at age 17–18 weeks.

(C) OGTT (2 g/kg) on 17- to 18-week-old Gpr52−/− and WT mice. Plasma glucose and insulin concentrations are plotted at the indicated time points (n = 26–39).

(D) Liver weight (left) and hepatic triglyceride content (right) of Gpr52−/− and WT mice aged 16–23 weeks under normal diet (ND) (n = 4–6) or 17-week HFD (n = 15–21).

(E) Hepatic gene expressions involved in fatty acid biosynthesis in Gpr52−/− and WT mice fed ND (n = 5) and HFD (n = 9) at age 21–23 weeks under fed condition. The average Ct value of WT mice fed ND was 22.5, 26.7, 29.0, 27.7, 32.1, and 31.5 for Scd1, Elovl6, Acc1, Acc2, Srebp1c, and Pparg2, respectively, when cDNAs synthesized from 20 ng total RNA were used for each qPCR.

Data are means ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, between the animal groups by one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test.

We then examined the gene expressions of Scd1, Elovl6, Acc1, and Acc2 in Gpr52−/− liver. Interestingly, mRNA expressions of Scd1 and Elovl6 were significantly increased by HFD feeding in WT liver (Figure 4E), in accord with the previous reports (Chan et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2004; Oosterveer et al., 2009); however, the increase by HFD feeding was completely abolished in Gpr52−/− liver. Furthermore, HFD feeding did not increase Acc1 expression in WT liver, but rather suppressed it in Gpr52−/− liver. Acc2 expression tended to be increased by HFD in WT mice, but not in Gpr52−/− mice.

We then investigated the molecular mechanisms involved in the changes of Scd1 and Elovl6 expressions by HFD feeding by comparing mRNA expressions of Srebp1c and Pparg2 in Gpr52−/− and WT liver (Figure 4E). Hepatic Srebp1c expression of Gpr52−/− mice was not different from that of WT mice. Interestingly, mRNA expression of Pparg2 was significantly increased by HFD feeding in WT liver, but not in Gpr52−/− liver, suggesting that Gpr52 is critical in HFD-induced Pparg2 upregulation in the liver.

Discussion

GPR52 is an orphan GPCR that couples with the stimulatory G protein Gs (Allen et al., 2017; Komatsu et al., 2014). When expressed in cells, GPR52 activates Gs signaling and increases [cAMP]i in the absence of its ligand (Martin et al., 2015). Recently, Lin et al. clarified the molecular structure and the mode of constitutive activity of GPR52 using crystal structure analysis (Lin et al., 2020). They found that extracellular loop 2 of GPR52 occupies the orthosteric ligand-binding pocket, which contributes to its self-activation. In addition, they identified the surrogate agonist c17 and showed that GPR52 has a very high level of basal activation that reaches as high as 90% of the maximal activation induced by c17.

In contrast, Setoh et al. identified another GPR52 agonist, compound 7m, and found that it dose dependently increased [cAMP]i concentrations in CHO cells expressing GPR52 (Setoh et al., 2014). The cAMP-increasing effect of c11 in HEK293 cells expressing GPR52 in our present study was consistent with the result by Setoh et al. In addition, recent studies found that 3-BTBZ, another agonist of GPR52, potently increased [cAMP]i in a β-arrestin 2 independent manner in frontal cortical neurons (Hatzipantelis et al., 2020).

Interestingly, fatty acid biosynthesis was dose dependently increased by c11 in HepG2 cells, an effect that was absent in GPR52-KD HepG2 cells. These results indicate that fatty acid biosynthesis can be further upregulated by GPR52 activation. In contrast, cholesterol biosynthesis was not increased by c11 in HepG2 cells, whereas it was significantly reduced by GPR52 knockdown, suggesting that GPR52 is critical in the regulation of cholesterol biosynthesis in liver. In addition, mRNA expression of Hmgcr was significantly decreased in the epiWAT and liver of Gpr52−/− mice. The activity of Hmgcr is known to be regulated both transcriptionally (Luo et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2010) and post-transcriptionally (van den Boomen et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2020), implying that decreased Hmgcr expression in epiWAT and liver of Gpr52−/− mice might well contribute to the reduction of de novo cholesterol biosynthesis seen in these tissues. The lack of effect of c11 may suggest that self-activation of GPR52 is sufficient for full activation of cholesterol biosynthesis. Alternatively, cAMP has been shown to activate phosphoprotein phosphatase inhibitor-1 (PPI-1), resulting in the decrease of cholesterol biosynthesis through inactivation of HMGCR (Bathaie et al., 2017). In addition, Hu et al. reported that prenatal caffeine exposure increased the hepatic expression of Hmgcr by lowering hepatic cAMP concentrations (Hu et al., 2019). By contrast, cAMP/PKA/CREB signaling has been reported to upregulate hepatic HMGCR expression (Tian et al., 2010). Therefore, it is still unclear whether or not decreased cAMP contributes to the decrease in cholesterol biosynthesis noted in our GPR52 knockdown HepG2 cells.

We further elucidated the molecular mechanism of GPR52-dependent biosynthesis of fatty acid and found that the gene expressions of SCD1 and ELOVL6 were induced by GPR52 activation by c11. These genes have been shown to play a critical role in fatty acid metabolism in the liver. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD1) is the rate-limiting enzyme of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) formation (ALJohani et al., 2017; Dobrzyn et al., 2010). Elongation of very long chain fatty acids protein 6 (ELOVL6) is an enzyme that lengthens saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids with 12, 14, and 16 carbons (Guillou et al., 2010; Shimano, 2012). In addition, we found that hepatic expression Acc1 in Gpr52−/− mice tended to be lower (p = 0.053) than in WT mice only under HFD feeding. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (ACC1) is a rate-limiting enzyme of biosynthesis of fatty acids that catalyzes carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to produce malonyl-CoA (Kim et al., 2017; Wakil and Abu-Elheiga, 2009). When fed HFD, Elovl6-deficient mice develop obesity and hepatosteatosis, but remain insulin sensitive (Matsuzaka et al., 2007). By contrast, Scd1-deficient mice are resistant to obesity, hepatosteatosis, and insulin resistance in response to HFD feeding (Ntambi et al., 2002). Moreover, liver-specific Acc1-deficient mice are protected from HFD-induced hepatosteatosis (Mao et al., 2006). Considering these results together, the lack of increase in hepatic Scd1 expression by HFD may play a role in protecting Gpr52−/− mice from developing hepatosteatosis under HFD.

We also investigated the molecular mechanisms of the changes in Scd1 and Elovl6 expressions by HFD feeding. Transcriptional regulation of Scd1 and Elovl6 has been studied intensively, and they were reported to be transactivated by SREBP1c (Mauvoisin and Mounier, 2011) and PPARγ (Morán-Salvador et al., 2011). Interestingly, we found that hepatic expression of Pparg2 was significantly increased in WT mice, but not in Gpr52−/− mice (Figure 4E). HFD feeding of mice has been reported to upregulate Pparg2 but not Pparg1 in the liver (Vidal-Puig et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 2006). Moreover, PPARγ was reported to be essential for upregulation of Scd1 in the liver (Morán-Salvador et al., 2011). In addition, liver-specific PPARγ knockout has been reported to decrease Scd1 expression in AZIP mice, in which Pparg2 expression is markedly enhanced (Gavrilova et al., 2003). Furthermore, in null PPARγ knockout mice, the expressions of Scd1 and Elovl6 were found to be decreased in adipose tissues that abundantly express PPARγ2 (Virtue et al., 2012). Taken together, HFD-induced upregulation of Pparg2 via Gpr52 is suggested to be involved in the increase in expressions of Scd1 and Elovl6 in the liver of WT mice (Figure 5). Considering that gene ablation of Acc2 mice was reported to be resistant to HFD-induced hepatosteatosis (Abu-Elheiga et al., 2012), the lack of induction of Acc2 by HFD in Gpr52−/− mice may well contribute at least in part to their reduced triglyceride accumulation by HFD.

Figure 5.

A model for HFD-induced insulin resistance and hepatosteatosis via a GPR52/PPARγ2/lipogenesis pathway

See text in detail. FA, fatty acid; TG, triglyceride.

GPR52 was initially cloned from the genomic database (Sawzdargo et al., 1999) and was later found to be expressed abundantly in the brain (Komatsu et al., 2014; Yao et al., 2015). In addition, Nishiyama et al. reported that Gpr52−/− mice exhibit hyperlocomotion when exposed to a novel environment or when treated by an adenosine A2A receptor (ADORA2A) agonist (Nishiyama et al., 2017), suggesting that the reduced adiposity and enhanced insulin sensitivity of our Gpr52−/− mice may be attributable to Gpr52 dysfunction in the brain.

Our present study shows that GPR52 in hepatocytes promotes biosynthesis of fatty acid and cholesterol in a ligand-dependent and a constitutive manner, respectively. The endogenous ligand for GPR52 remains unknown so far, but some members of the fatty acid family might well act as cognate ligands for GPR52, according to sequence-structure based phylogeny (Kakarala and Jamil, 2014).

It is advantageous for all mammals to deposit triglyceride in their tissues in case of surplus energy intake. However, in modern human society, excessive fat intake that occurs on a regular basis results in the development of hepatosteatosis and its consequent insulin resistance. Accordingly, compounds that inhibit ligand-dependent GPR52 activation may represent novel therapeutic tools to prevent hepatosteatosis and insulin resistance induced by excessive fat intake in humans.

Limitations of the study

Although we identified that Gpr52 is essential for HFD-induced increase in hepatic expressions of Pparg2, Scd1, and Elovl6, it remains unknown whether HFD-induced increase of Scd1 and Elovl6 is mediated through increased PPARγ2 signaling. In addition, our present study suggests that HFD-derived dietary molecules may activate GPR52 signaling to increase fatty acid biosynthesis in liver. However, the endogenous ligand for GPR52 was not identified in the present study. Furthermore, we could not clarify the regulatory mechanism of cholesterol biosynthesis by GPR52 in liver. Analyses with biased pharmacological ligands and/or blockade of intervening signaling will be helpful to decipher these molecular mechanisms in the future.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further requests for resources should be directed to the lead contact, Mitsuo Wada (mitsuo.wada@jt.com).

Materials availability

This work did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

This article includes all analyzed data.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying transparent methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Saito, N. Otake, and Y. Shimamura for mice breeding and genotyping. The study was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (19K06757 and 17KK0188 to E.L. and 19K07281 to T.M.).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, M.W., K.Y., H.O., Y.Y., E.L., and T. Miki; methodology, M.W., K.Y., and H.O.; investigation, M.W., K.Y., H.O., K.S., T. Maekawa, and E.L.; writing – original draft, M.W.; Writing – review & editing, M.W., T.O., E.L., and T. Miki; supervision, E.L., and T. Miki.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: April 23, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102260.

Supplemental information

References

- Abu-Elheiga L., Wu H., Gu Z., Bressler R., Wakil S.J. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2−/− mutant mice are protected against fatty liver under high-fat, high-carbohydrate dietary and de Novo lipogenic conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:12578–12588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.309559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALJohani A.M., Syed D.N., Ntambi J.M. Insights into stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 regulation of systemic metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2017;28:831–842. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J.A., Raval S.R., Yang R., Xi S. Genome-wide tissue transcriptome profiling and ligand screening identify seven striatum-specific human orphan GPCRs. FASEB J. 2017;31:576. [Google Scholar]

- Bathaie S.Z., Ashrafi M., Azizian M., Tamanoi F. Mevalonate pathway and human cancers. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2017;10:77–85. doi: 10.2174/1874467209666160112123205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Boomen D.J.H., Volkmar N., Lehner P.J. Ubiquitin-mediated regulation of sterol homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2020;65:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan M.-Y., Zhao Y., Heng C.-K. Sequential responses to high-fat and high-calorie feeding in an obese mouse model. Obesity. 2008;16:972–978. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrzyn P., Jazurek M., Dobrzyn A. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase and insulin signaling - what is the molecular switch? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1797:1189–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilova O., Haluzik M., Matsusue K., Cutson J.J., Johnson L., Dietz K.R., Nicol C.J., Vinson C., Gonzalez F.J., Reitman M.L. Liver peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma contributes to hepatic steatosis, triglyceride clearance, and regulation of body fat mass. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:34268–34276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300043200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillou H., Zadravec D., Martin P.G.P., Jacobsson A. The key roles of elongases and desaturases in mammalian fatty acid metabolism: insights from transgenic mice. Prog. Lipid Res. 2010;49:186–199. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusach A., Maslov I., Luginina A., Borshchevskiy V., Mishin A., Cherezov V. Beyond structure: emerging approaches to study GPCR dynamics. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2020;63:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzipantelis C.J., Lu Y., Spark D.L., Langmead C.J., Stewart G.D. β-arrestin-2-dependent mechanism of GPR52 signalling in frontal cortical neurons. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020;11:2077–2084. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilger D., Masureel M., Kobilka B.K. Structure and dynamics of GPCR signaling complexes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2018;25:4–12. doi: 10.1038/s41594-017-0011-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C.C., Qing K., Chen Y. Diet-induced changes in stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 expression in obesity-prone and -resistant mice. Obes. Res. 2004;12:1264–1270. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S., Liu K., Luo H., Xu D., Chen L., Zhang L., Wang H. Caffeine programs hepatic SIRT1-related cholesterol synthesis and hypercholesterolemia via A2AR/cAMP/PKA pathway in adult male offspring rats. Toxicology. 2019;418:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakarala K.K., Jamil K. Sequence-structure based phylogeny of GPCR Class A Rhodopsin receptors. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2014;74:66–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A.A., Agarwal H., Reddy S.S., Arige V., Natarajan B., Gupta V., Kalyani A., Barthwal M.K., Mahapatra N.R. MicroRNA 27a is a key modulator of cholesterol biosynthesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2020;40 doi: 10.1128/MCB.00470-19. e00470–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C.W., Addy C., Kusunoki J., Anderson N.N., Deja S., Fu X., Burgess S.C., Li C., Chakravarthy M., Previs S. Acetyl CoA carboxylase inhibition reduces hepatic steatosis but elevates plasma triglycerides in mice and humans: a bedside to bench investigation. Cell Metab. 2017;26:394–406.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu H., Maruyama M., Yao S., Shinohara T., Sakuma K., Imaichi S., Chikatsu T., Kuniyeda K., Siu F.K., Peng L.S. Anatomical transcriptome of G protein-coupled receptors leads to the identification of a novel therapeutic candidate GPR52 for psychiatric disorders. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Li M., Wang N., Wu Y., Luo Z., Guo S., Han G.W., Li S., Yue Y., Wei X. Structural basis of ligand recognition and self-activation of orphan GPR52. Nature. 2020;579:152–157. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J., Yang H., Song B.L. Mechanisms and regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020;21:225–245. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J., DeMayo F.J., Li H., Abu-Elheiga L., Gu Z., Shaikenov T.E., Kordari P., Chirala S.S., Heird W.C., Wakil S.J. Liver-specific deletion of acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 reduces hepatic triglyceride accumulation without affecting glucose homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:8552–8557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603115103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A.L., Steurer M.A., Aronstam R.S. Constitutive activity among orphan class-A G protein coupled receptors. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaka T., Shimano H., Yahagi N., Kato T., Atsumi A., Yamamoto T., Inoue N., Ishikawa M., Okada S., Ishigaki N. Crucial role of a long-chain fatty acid elongase, Elovl6, in obesity-induced insulin resistance. Nat. Med. 2007;13:1193–1202. doi: 10.1038/nm1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauvoisin D., Mounier C. Hormonal and nutritional regulation of SCD1 gene expression. Biochimie. 2011;93:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morán-Salvador E., López-Parra M., García-Alonso V., Titos E., Martínez-Clemente M., González-Périz A., López-Vicario C., Barak Y., Arroyo V., Clària J. Role for PPARγ in obesity-induced hepatic steatosis as determined by hepatocyte- and macrophage-specific conditional knockouts. FASEB J. 2011;25:2538–2550. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-173716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahata T., Tokumaru K., Ito Y., Ishii N., Setoh M., Shimizu Y., Harasawa T., Aoyama K., Hamada T., Kori M. Design and synthesis of 1-(1-benzothiophen-7-yl)-1H-pyrazole, a novel series of G protein-coupled receptor 52 (GPR52) agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018;26:1598–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama K., Suzuki H., Maruyama M., Yoshihara T., Ohta H. Genetic deletion of GPR52 enhances the locomotor-stimulating effect of an adenosine A2A receptor antagonist in mice: a potential role of GPR52 in the function of striatopallidal neurons. Brain Res. 2017;1670:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntambi J.M., Miyazaki M., Stoehr J.P., Lan H., Kendziorski C.M., Yandell B.S., Song Y., Cohen P., Friedman J.M., Attie A.D. Loss of stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 function protects mice against adiposity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002;99:11482–11486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132384699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterveer M.H., van Dijk T.H., Tietge U.J.F., Boer T., Havinga R., Stellaard F., Groen A.K., Kuipers F., Reijngoud D.-J. High fat feeding induces hepatic fatty acid elongation in mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn O., Oh D.Y., McNelis J., Sanchez-Alavez M., Talukdar S., Lu M., Li P.P., Thiede L., Morinaga H., Kim J.J. G protein-coupled receptor 21 deletion improves insulin sensitivity in diet-induced obese mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:2444–2453. doi: 10.1172/JCI61953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter S.L., Hall R.A. Fine-tuning of GPCR activity by receptor-interacting proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:819–830. doi: 10.1038/nrm2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawzdargo M., Nguyen T., Lee D.K., Lynch K.R., Cheng R., Heng H.H.Q., George S.R., O’Dowd B.F. Identification and cloning of three novel human G protein-coupled receptor genes GPR52, ΨGPR53 and GPR55: GPR55 is extensively expressed in human brain. Mol. Brain Res. 1999;64:193–198. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setoh M., Ishii N., Kono M., Miyanohana Y., Shiraishi E., Harasawa T., Ota H., Odani T., Kanzaki N., Aoyama K. Discovery of the first potent and orally available agonist of the orphan G-protein-coupled receptor 52. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:5226–5237. doi: 10.1021/jm5002919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimano H. Novel qualitative aspects of tissue fatty acids related to metabolic regulation: lessons from Elovl6 knockout. Prog. Lipid Res. 2012;51:267–271. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L., Song Y., Xing M., Zhang W., Ning G., Li X., Yu C., Qin C., Liu J., Tian X. A novel role for thyroid-stimulating hormone: up-regulation of hepatic 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme a reductase expression through the cyclic adenosine monophosphate/protein kinase A/cyclic adenosine monophosphate-responsive element binding protein. Hepatology. 2010;52:1401–1409. doi: 10.1002/hep.23800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Puig A., Jimenez-Liñan M., Lowell B.B., Hamann A., Hu E., Spiegelman B., Flier J.S., Moller D.E. Regulation of PPAR gamma gene expression by nutrition and obesity in rodents. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:2553–2561. doi: 10.1172/JCI118703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtue S., Masoodi M., Velagapudi V., Tan C.Y., Dale M., Suorti T., Slawik M., Blount M., Burling K., Campbell M. Lipocalin prostaglandin D synthase and PPARγ2 coordinate to regulate carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in Vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7:1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakil S.J., Abu-Elheiga L.A. Fatty acid metabolism: target for metabolic syndrome. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50:S138–S143. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800079-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootten D., Christopoulos A., Marti-Solano M., Babu M.M., Sexton P.M. Mechanisms of signalling and biased agonism in G protein-coupled receptors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018;19:638–653. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y., Cui X., Al-Ramahi I., Sun X., Li B., Hou J., Difiglia M., Palacino J., Wu Z.Y., Ma L. A striatal-enriched intronic GPCR modulates huntingtin levels and toxicity. ELife. 2015;4:e05449. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.L., Hernandez-Ono A., Siri P., Weisberg S., Conlon D., Graham M.J., Crooke R.M., Huang L.S., Ginsberg H.N. Aberrant hepatic expression of PPARgamma2 stimulates hepatic lipogenesis in a mouse model of obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hepatic steatosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:37603–37615. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604709200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This article includes all analyzed data.