Abstract

The employment and utilization of advanced practice providers (APPs) in the emergency department has been steadily increasing. Physicians, physician assistants (PAs), and nurse practitioners (NPs) have vastly different requirements for admission to graduate programs, clinical exposure, and postgraduate training. It is important that as supervisory physicians, patients, hospital administrators, and lawmakers, we understand the differences to best create a collaborative, supportive, and educational framework within which PAs/NPs can work effectively as part of a care team. This paper reviews the trends, considerations, and challenges of an evolving clinician workforce in the specialty of emergency medicine (EM). Subsequently, the following parameters of APP training are examined and discussed: the divergence in physician, PA, and NP education and training; requirements of PA and NP degree programs; variation in clinical contact hours; degree‐specific licensing and postgraduate EM certification; opportunities for specialty training; and the evolution and availability of residency programs for APPs. The descriptive review is followed by a discussion of contemporary and timely issues that impact EM and considerations brought forth by the expansion of APPs in EM such as the current drive to independent practice and the push for reimbursement parity. We review current position statements from pertinent professional organizations regarding PA and NP capabilities, responsibilities, and physician oversight as well as billing implications, care outcomes and medicolegal implications.

The number of emergency departments (EDs) employing advanced practice providers (APPs), including physician assistants and nurse practitioners (PAs/NPs), has increased from 28% in 1997 to 77% in 2006. 1 In a survey of academic EDs in 2015, 74% employed APPs. 2 PAs/NPs staffed 15% of ED visits in 2009 and 40% of these visits were not seen by an attending physician, meaning that 6% of ED visits in 2009 were seen exclusively by PAs/NPs. 3 Furthermore, rural EDs are much more likely to employ APPs without on‐site physicians. 4 These trends will likely continue due to pressure to meet the shortage of physicians around the country, restrictions of resident work hours in academic institutions, pressures to reduce costs, and lobbying efforts by APP professional organizations to become fully independent clinicians.

Physicians, PAs, and NPs have vastly different requirements for admission to graduate programs, clinical exposure, and postgraduate training. It is important that as supervisory physicians, patients, hospital administrators, and lawmakers, we understand the differences in order to best create a collaborative, supportive, and educational framework within which PAs/NPs can work effectively as part of a care team.

In this paper we discuss the divergence in physician, PA, and NP education and training; requirements of PA and NP degree programs; variation in clinical contact hours; degree‐specific licensing and postgraduate emergency medicine (EM) certification; opportunities for specialty training; and the evolution and availability of residency programs for APPs. The descriptive review is followed by a discussion of contemporary and timely issues that impact EM and considerations brought forth by the expansion of APPs in EM such as the current drive to independent practice and the push for reimbursement parity. We review current position statements from pertinent professional organizations regarding PA and NP capabilities, responsibilities, and physician oversight as well as billing implications and care outcomes and medicolegal implications.

METHODS

This paper is a thematically organized review of training and issues related to the expansion of APP staff in EM based on the didactic panel presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) in Las Vegas, Nevada, in 2019 and sponsored by the SAEM APP Medical Director Interest Group. The following institutions participated in this didactic: Massachusetts General Hospital, Yale School of Medicine, and University of Massachusetts Medical School‐Baystate: The didactic was interactive and provided an opportunity to both share data and gather information on thematic areas of concern for consideration and clarification. The didactic discussion was the basis for selection of the concepts in this paper. Once the themes were identified, peer‐reviewed papers, organizational statements, and documents were reviewed to inform the discussion in this article. The writers of the article are the interest group past chair, current chair, and vice chair as well as PA and NP representation from their academic departments.

Prevalence and Growth of the APP Workforce in the ED

Physician assistants and NPs are rapidly growing professions and currently make up a significant portion of ED clinicians. The current U.S. ED workforce consists of approximately 60,000 clinicians, including board‐certified EM physicians, non‐EM physicians, and APPs. Of that workforce, 61% are board‐certified EM physicians while 24% are APPs. Currently 80% of EDs in the United States employ APPs. 5

The American Association of Medical Colleges predicts that there will be a shortage of 22,200 to 32,600 EM physicians by 2030. 6 They also predict that the overall PA and NP workforce will increase annually by 4.3 and 6.8%, respectively, until 2030 6 although other research shows that PA growth has plateaued since 2005. 7 Physician growth, on the other hand, is only expected to grow at a rate of 1.1% over the same time period. 6 Considering these growth trends it is likely that the presence and percentage of APPs in EM will continue to increase.

The Divergence of Physician, PA, and NP Education

Although physicians, PAs, and NPs all provide care to patients in emergency settings, there are significant differences in their predegree and degree preparations as well as postgraduate specialty training. An important difference is that emergency physicians provide specialty care after completing a medical degree as well as 3 to 4 years of specialty training dedicated to EM. This contrasts with PAs and NPs who can be hired postdegree without specialty training (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparative Training Characteristics of NP, PA, and Physician Degrees

| NP | PA | Physician | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prematriculation degree | Bachelor of Nursing (some programs allow concurrent or sequential bachelors) | Bachelors (some programs allow concurrent or sequential bachelors) | Bachelors (some programs allow sequential bachelors) |

| Prematriculation health care hours required | Range from zero (direct entry) to 1–2 years | Range from none (direct entry) to 2,000 | Variable by medical school |

| Average program clinical contact hours | 500 | 2,000 | 5,000* |

| Entry‐level degree granted | Masters | Masters | Doctorate |

| Residency required for specialty practice | Not required | Not required | Required 3‐ and 4‐year program 13,500–18,000* clinical hours |

| Emergency certification |

Not required ENP‐C |

Not required Emergency CAQ |

N/A |

ENP‐C = Emergency Nurse Practitioner Certification; CAQ = Certification of Added Qualifications; NP = nurse practitioner; PA = physician assistant.

Assumes 60‐hour work week.

NP Degrees

Advanced practice nurses are first subdivided into one of four roles, nurse anesthetist, nurse‐midwife, clinical nurse specialist, and NPs. NP candidates must choose a population focus, including family/individuals across lifespan, adult/gerontology, pediatrics, psychiatry, or women’s health. The vast majority of NPs in the ED choose a focus in family/individual across lifespan and become certified as family NPs (FNP). Although the FNP path provides exposure to a wide range of age groups, the clinical training is almost exclusively in the outpatient setting without a dedicated EM rotation. The adult/gerontology population focus allows for an acute care nursing specialization with more exposure to inpatient and critical care medicine; however, that pathway is limited to treatment of patients > 12 years of age and therefore is considered a less viable pathway into EM. In recent years, some programs are offering an EM pathway either concurrent with or in addition to an FNP certification. These EM‐specific pathways provide additional clinical time, varying from 168 to 500 hours, 8 in either EM or urgent care.

Degree options for NPs include a Master’s of Science in nursing, which generally calls for 500 to 600 hours of postbachelor’s health care experience and a Doctorate of Nursing Practice, which calls for 1,000 hours of postbachelor’s health care experience. 9 Many NP programs require a minimum of 1 to 2 years of clinical experience prior to entry. For a full‐time nurse this translates into 2,000 to 4,000 hours of nursing experience. NP programs intend to use this clinical experience as well as the education from a Bachelor of Nursing Degree, as a base on which to build. There are certainly NP students who bring with them many more years of bedside nursing experience than the minimum required. However, direct‐entry NP programs, which allow for entry without bedside nursing experience, do exist and lead to a wide variation in clinical experience of NP graduates overall.

PA Degrees

Physician assistant degree programs are generally master’s programs averaging 27 months in length. Some combined bachelor/masters programs do exist. The amount of clinical experience required for PA applicants varies from 2,000 hours to experience “recommended/preferred.” Admitted applicants, however, have an average of 3,500 hours of health care experience prior to admission. 10 Unlike NP applicants, however, where the preprogram clinical experience typically consists primarily of bedside nursing, the type of health care experience prior to entry can be variable and each individual program dictates what qualifies as acceptable experience in their admissions process. The PA education is general with didactics and clinical rotations in medical and behavioral sciences, internal medicine, family medicine, surgery, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, EM, and geriatric medicine.

Variation in Clinical Contact Hours by Degree

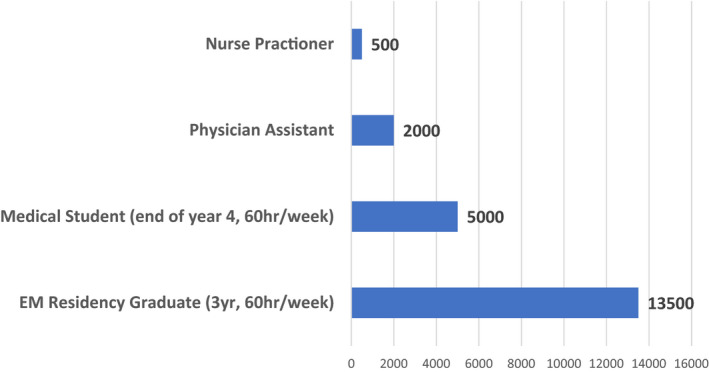

The number of clinical contact hours required during graduate school varies significantly between degree types. NP masters programs require 500 clinical hours, 9 whereas PA programs average 2,000 hours. 11 For medical school graduates, if assuming a 60‐hour work week, an average of 5,000 clinical hours is acquired by the time of graduation as a conservative estimate. When accounting for required postgraduate residency, physician graduates of a 3‐year EM residency typically have 13,500 clinical contact before practicing independently (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Variation in clinical contact hours by degree.

Postgraduate Training

The opportunities for APP postgraduate education in EM have increased over the past several years. These programs, referred to as residencies or fellowships, provide structured learning to PAs and NPs new to EM. Most programs are between 12 and 18 months with rotations in EM, emergency ultrasound, trauma, critical care, and other related specialties. At present the programs do not have mandated accreditation. They previously had voluntary accreditation by ARC‐PA, an independent accrediting body for PA educational programs that has been in abeyance since 2014. In the absence of mandatory accreditation, the Society of Emergency Medicine Physician Assistants (SEMPA) developed and published EM‐PA postgraduate training program standards in 2015. 12 As of 2017, only 11% of PAs working in the ED have had residency training in EM. 13 The number is unknown for NPs but likely much lower as these residency programs are typically focused on PAs. Requiring specialty certification to practice is a current controversy for APPs because it is thought to limit the horizontal mobility of clinical practice that is intrinsic to the degrees.

For both PAs and NPs, most postgraduate training occurs as nonstandardized site‐specific on‐the‐job training. At present, there is no standardization for onboarding in EM, which has led health care organizations to create their own standards and on‐boarding processes. 14

Licensing/Certifications

Currently APPs undergo training in general medicine prior to entering practice. To obtain a license, initial general certification for NPs is required in most, but not all, states. There are five certifying bodies for NP certification depending on the population that the NP is trained to see. These are the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), the Pediatric Nursing Certification Board (PNCB), the National Certification Corporation (NCC), the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP), and the American Association of Critical‐Care Nurses (AACN). Most organizations require that a NP practicing in the ED be a FNP to have exposure to both children and adults. The two certifying authorities for FNPs are the ANCC and the AANP. Both administer a general examination without dedicated emergency content. The pass rates are 75 and 81%, respectively. 15

Emergency‐specific certification for NPs, the Emergency Nurse Practitioner Certification (ENP‐C) process, was instituted in 2017. 16 The certification has three distinct pathways:

A minimum of 2,000 direct, emergency care practice hours in the past 5 years as a NP, evidence of 100 hours of continuing emergency care education with a minimum of 30 of those hours in emergency care procedural skills, or

Completion of an academic emergency care graduate or postgraduate NP program, or

Completion of an approved emergency fellowship program. 16

ENPs currently have two options for recertification:

Meeting the minimum of 1,000 emergency care clinical practice hours and 100 emergency‐related continuing education requirements within the current 5‐year period of certification, or

Recertify by taking and passing the appropriate certification examination before expiration of the current certification.

Responsibility for supervision and credentialing postgraduate NP programs is not clearly delineated. In the first 2 years after implementation of the ENP process, 546 examinations have been administered with an overall pass rate of 87%. Of those becoming certified, 236 did so through the continuing education pathway, 86 through academic programs, and five through fellowship programs. 15

Physician assistant wanting to practice clinically after graduation must take the Physician Assistant National Certification Examination (PANCE) to receive a state license. It is administered by a single certifying body, the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants (NCCPA). According to the NCCPA the pass rate was 97% in 2018. Recertification occurs on a 10‐year cycle. Postgraduate specialty certification by the NCCPA consist of a Certification of Added Qualifications (CAQ) in a subset of specialties including EM. A residency is not required to take the CAQ examination. In EM, the CAQ requires all four of the following:

3,000 hours of EM experience or approximately 18 months of full‐time practice;

150 hours of EM‐specific CME over 6 years;

A procedure/case requirement; and

An EM specialty examination. 17

Maintenance of CAQ certification requires PAs to earn at least 125 hours of EM CME and pass the certification examination every 10 years; in addition to maintaining general PA certification. Between 2011 and 2014 only 533 PAs were recipients of CAQs across all specialties. 18

Competency

Variation in educational models makes it difficult to assess competency. As medicine moves toward competency‐based education we can no longer rely solely on hours served. We must ensure that those hours are leading to mastery of clearly delineated competencies. Any profession seeking autonomous practice must demonstrate an adoption of educational methods in alignment with mastery and educational approaches that use criterion‐based assessments focused on workplace‐observed behaviors. Competency must come before autonomy. Knowledge‐based examinations and time served in practice is no longer sufficient. Competency‐based, time‐variable education programs that are in practice in Canada for physicians may be an effective way to ensure safe and competent practice for all stakeholders involved regardless of professional degree. 19 Although physician education is currently taken as the criterion standard, it is also evolving and moving toward more competency‐based assessment. Other professions should consider similar processes of assessment.

The Drive for Practice Autonomy

The drive for practice autonomy has largely been led by NP advocacy groups who have lobbied for legislation and gained full autonomy in 23 states and partial autonomy in another 16 states. Practice autonomy is defined as in Table 2. 20

Table 2.

Definitions of Autonomy According to AANP

| Full practice autonomy | State practice and licensure laws permit all NPs to evaluate patients; diagnose, order, and interpret diagnostic tests; and initiate and manage treatments, including prescribing medications and controlled substances, under the exclusive licensure authority of the state board of nursing. This is the model recommended by the National Academy of Medicine, formerly called the Institute of Medicine, and the National Council of State Boards of Nursing. |

| Reduced practice autonomy | State practice and licensure laws reduce the ability of NPs to engage in at least one element of NP practice. State law requires a career‐long regulated collaborative agreement with another health provider for the NP to provide patient care, or it limits the setting of one or more elements of NP practice. |

| Restricted practice autonomy | State practice and licensure laws restrict the ability of NPs to engage in at least one element of NP practice. State law requires career‐long supervision, delegation or team management by another health provider for the NP to provide patient care. 20 |

AANP = American Association of Nurse Practitioners; NP = nurse practitioner; PA = physician assistant.

There are legislative efforts for autonomy under way in 11 states that currently have restricted practice for NPs. 20 Of note, although there may be state autonomy, in many cases practice is still limited at the hospital/clinic level by the institution or group within which the NP practices.

Physician assistant groups have not made autonomy a cornerstone of their advocacy efforts but rather stress a team approach to patient care. This fundamental difference in outlook is largely thought to rest on the fact that PAs developed via a historical connection with medical doctors (MDs) on the battlefield. Even if there is not a concerted effort, a push toward “autonomy is inevitable” according to the American Academy of PAs (AAPA) mirroring the efforts of NP groups. 21 PAs have independent licensure only in the Netherlands. 22 They have also just been granted autonomy in the Indian Health Service. 23 For PAs, the debate for increased autonomy has largely centered around moving toward the AAPA‐endorsed model of a “collaborating physician” versus a “supervising physician.” According to a survey conducted by the AAPA, those PAs in practice longer spend less than 10% of time in consultation with physicians making this a “more accurate reflection of true practice trends.” 24

There is also a trend toward more autonomy in the area of governance for PAs. There is a move away from MD‐directed governance to self‐governance with a push toward autonomous PA state boards for licensure, regulation, and discipline, with some physician participation. According to a survey by the AAPA this effort is supported by 80% of respondents. 24 There is support by 63% of those surveyed for complete elimination of the need for specific collaboration or supervisory relationship. 24 This drive toward autonomous practice is framed in the context of maintaining employment competitiveness with NPs who have independent practice in 23 states. Other areas currently under reexamination are the possibility of independent licensure, and a shift towards independent prescriptive authority which has occurred in many states. The differences in autonomy have created friction between NPs and PAs who can find themselves with varying advantages depending on state legislation.

Position Statements

Autonomy has major implications and many professional and lobbying groups have put forth position statements on the issue in recent years (see Table 3). 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31

Table 3.

Position Statements From Major EM, PA, and NP Organizations

|

American Medical Association (AMA) Policy H‐35.989 2017 (25) |

With regard to physician assistants specifically, AMA policy states that physician assistants should be authorized to provide patient care services only so long as the physician assistant is functioning under the direction and supervision of a physician or group of physicians. Accordingly, the AMA opposes legislation or proposed regulations authorizing physician assistants to make independent medical judgment regarding such decisions as the drug of choice for an individual patient. |

| [In regards to physician assistants,] the AMA advocates in support of maintaining the authority of medical licensing and regulatory boards to regulate the practice of medicine through oversight of physicians, physician assistants and related medical personnel. | |

| The AMA also opposes legislative efforts to establish autonomous regulatory boards meant to license, regulate, and discipline physician assistants outside of the existing state medical licensing and regulatory bodies' authority and purview. | |

|

American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) 2013 (26) |

PAs and APRNs do not replace the medical expertise and patient care provided by emergency physicians |

| PAs and APRNs working in EDs should have or acquire specific experience or specialty training in emergency care, and should receive continuing education in providing emergency care. | |

|

American Academy of Emergency Medicine (AAEM) 2019 (27) |

The American Academy of Emergency Medicine AAEM believes that emergency department patients should have timely and unencumbered access to the most appropriate care led by a board‐certified emergency physician (ABEM, AOBEM). We do not support the independent practice of APPs and other non‐physician clinicians. |

| As a member of the emergency department team an APP should not replace an emergency physician, but rather should engage in patient care in a supervised role in order to improve patient care efficiency without compromising safety. | |

| The role of the APPs within the department must be defined by their clinical supervising physicians who must know the training of each APP and be involved in the hiring and continued employment evaluations of each APP as part of the emergency department team. | |

| Billing should reflect the involvement of the physician in the emergency visit. If the physician’s name is used for billing purposes, the physician must have added value to the patient visit. | |

| Every practitioner in an ED has a duty to clearly inform the patient of his/her training and qualifications to provide emergency care in the interest of transparency, APPs and other non‐physician clinicians should not be called doctor in the clinical setting. | |

|

American Academy of PAs (AAPA) 2019 (28) |

Contrary to the apparent belief of AAEM, PAs do not seek to practice independently. |

| PAs are seeking the removal of unnecessary administrative constraints, like the requirement for a PA to have an agreement with a supervising or collaborating physician. | |

|

Society of Emergency Medicine Physician Assistants (SEMPA) 2015 (29) |

As PAs, we wholeheartedly agree that physicians, by virtue of educational process, training, and specialty certification, are the most highly educated and trained clinicians in the health care system. We also absolutely agree with the Truth in Advertising campaign that the AMA has spearheaded. As clinicians, who also have the patient’s greatest interests at heart, PAs by law, statute, and professional ethics, attempt to avoid any confusion or misrepresentation of our role, our title, and the profession. We feel that despite any advanced degree at the doctorate level, it is imperative that only a MD or DO be referred to as doctor in the clinical setting. |

| SEMPA, as the organization that represents emergency medicine PAs, would like to clarify that while we support the term of APP when referring to PAs and NPs collectively, PAs and NPs are two professionally independent groups, each with their own individual unique philosophy, educational/training model, and goals. | |

| PAs value being members of a team that provides excellent care for patients, and believe that the team approach serves the patient more completely. For nearly 50 years, we, as physician assistants, have practiced medicine, with physician supervision, as members of a physician led health care team. PAs have never sought independent practice, nor do we foresee a change in the philosophy of our profession. | |

|

American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) 2006 (30) |

NPs are licensed, independent practitioners who provide primary and/or specialty nursing and medical care in ambulatory, acute and long‐term care settings. They are registered nurses with specialized, advanced education and clinical competency to provide health and medical care for diverse populations in a variety of primary care, acute and long‐term care settings. |

| As a licensed, independent practitioner, the NP participates as a team leader and member in the provision of health and medical care, interacting with professional colleagues to provide comprehensive care. | |

|

Emergency Nurse Practitioners (ENPs) AANP: American Academy of Nurse Practitioners AAENP: American Academy of Emergency Nurse Practitioners (1991 revised 2012) (31) |

Advanced practice registered nurses have a broad depth of knowledge and expertise in their specialty and can manage complex clinical and system issues. Nurses in advanced clinical practice provide comprehensive health assessments and demonstrate a high level of autonomy and expert skill in the diagnosis and treatment of many complex problems. |

| In the emergency setting APRNs are uniquely prepared to develop and apply theory, conduct research, educate health care providers and consumers, and develop standards of practice that contribute to optimum patient outcomes. |

APP = advanced practice provider; NP = nurse practitioner; PA = physician assistant.

Billing Differences, Cost Savings, and the Drive Toward Pay Parity

Medicare and large insurers are incentivized to push for autonomy, in part due to the current structure of billing. Hospitals may bill under the physician’s name, as a “shared” visit, when a PA/NP and a physician both provide face‐to‐face encounters with a patient on the same day. The physician must perform a substantive portion, defined as key components of the history, examination, or medical decision making, with documentation, for reimbursement of 100%. When the visit is not “shared” and billed under the APP, the visit is reimbursed at 85% of the physician charges for Medicare. Reimbursement is variable by private insurers.

The employment of PAs and NPs is often viewed as a cost savings measure. Those savings come from lower salaries compared to physicians as well as the differential in reimbursement outlined above. According to the New England Journal of Medicine a “recent national study of Medicare beneficiaries found that the cost of primary care provided by NPs was significantly lower than physician provided care.” 32 However, literature in specialty care is lacking. A recent study suggests that EDs with APPs have a higher resource utilization, admission, and imaging rates than those without. 33 However, as the authors have noted, it is unknown who ordered the imaging studies or hospitalization and if there was physician involvement. PA/NP productivity is difficult to measure when billing is a shared visit. In the future, cost savings may be a moot point because NPs are currently lobbying for equity of Medicare reimbursement. There is also an accompanying race to salary equity with physicians. If these lobbying efforts are successful, salary and reimbursement parity may erase any savings to patients or insurers.

Outcomes and Medicolegal Implications

To date, the legal risks of working with APPs for physicians are mostly unknown. As stated we know that the training for PAs and NPs differs and is abbreviated when compared to that of physicians. Supervision is variable by state and institution. This variability in training and supervision can lead to medicolegal risk for the APP and the physician supervisor. What exactly are these risks and how can they be mitigated? How do the different training of PAs and NPs, as well as variable postscholastic training, affect risk? How does the variation in direct supervision affect risk? What would be the impact on risk if APPs became independent clinicians? The answers to these questions are largely unknown.

Advanced practice providers work most commonly with low‐acuity patients. In a 2018 Journal of the American Academy of PAs (JAAPA) study of the ACEP council 91% of institutions named indicated that APPs were seeing patients triaged to ESI level 5 while 36% of institutions indicated APPs were working with patients triaged to ESI level 1. 2 The rate of oversite in these cases was significant: The percentages of cases that were always presented to an physicians in real time were 24.6% for patients ESI 5 and only 51.2% for patients ESI 1, while the percentages of cases where the physicians either reviewed the chart after the patient left the ED or had no knowledge at all of the patient were 14 and 15.8%, respectively, for ESI level 5 patients and 16.3 and 9.3% for ESI level 1 patients. 2

There are sparse outcome data regarding patient satisfaction 34 and RVUs related to APPs in EM; 35 , 36 however, even less exist regarding quality of care imparted by APPs in the ED. Two studies in EM have opposing conclusions. One study from 2017 showed that pediatric patients seen in a community ED by APPs had no difference in 72‐hour recidivism than attending emergency physicians, 37 although this may be a questionable clinical metric. 38 On the other hand, Tsai et al. 39 found that while supervised APPs had similar quality of care to emergency physicians for asthma patients, unsupervised APPs did not. Further data are needed before conclusions can be made.

What are the legal risks for APPs? One study shows that for all specialties over the time span 2005 to 2014 there were 11.2 to 19.0 malpractice payment reports per 1,000 physicians, 1.4 to 2.4 per 1,000 PAs, and 1.1 to 1.4 per 1,000 NPs, 40 suggesting that APPs may be at less risk than physicians of litigation. However, because most cases will involve a supervising physician as well, these data are difficult to fully tease out and should be watched closely going forward. In 2011 Gifford et al. 41 reported that 70% of the emergency physicians did not believe that PAs, when properly supervised, were more likely to commit malpractice than any other clinician. There are no data examining the risk to the supervising physician when working with an APP and no indication that any attestation by the physician as to whether a patient was seen or not is protective.

LIMITATIONS

This review is not an exhaustive exploration of the topic at hand. There may be concepts that were omitted, such as those more applicable to community EDs or critical access hospitals. Every effort was made in drafting this paper to consider the most pressing issues and concepts facing EM with the expansion of APP staffing. The discussion centers on national trends and training requirements. State‐by‐state and institutional variations in practice autonomy exist and were noted where possible in the discussion.

This paper is primarily written for academic physicians and thus represents a physician‐centric discussion of the issues outlined and a focus on academic institutions. We included PA and NP representation both in authorship and in the review process from our institutions as well as national APP leadership to mitigate bias. Although the concepts under discussion are politically charged, a concerted effort was made to examine the issues objectively.

CONCLUSIONS/IMPLICATIONS

It is clear that advanced practice providers have a place in the current and future state of medicine, integrated within a care team, and that physician assistants and nurse practitioners are valued clinicians in emergency medicine. Although the expansion of advanced practice providers was originally intended to address the needs of primary care, the growth of advanced practice providers has now expanded into other specialties. In its current state, the difference in physician assistant and nurse practitioner graduate educational hours and the variability in on‐boarding training and specialized postgraduate training education makes it difficult to support autonomy of nonphysician providers in emergency medicine. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners wishing to practice in specialty‐based care, such as emergency medicine, need further specialty training. We call on physician assistant and nurse practitioner leadership, along with physician leadership, to ensure that both emergency medicine Certification of Added Qualifications and Emergency Nurse Practitioner Certification and postscholastic educational programs adhere to rigorous standards and assessments. Likewise, we call on medical and administrative leadership to incorporate and support these specialty certifications and educational programs into hiring and promotion considerations.

We encourage academic emergency physicians to work with national nurse practitioner and physician assistant leadership to create systems and processes that take into account the varied backgrounds that each group brings to the table and to make sure that this changing ED workforce is well supported with educational frameworks, physician supervision, and ongoing research in the areas of quality of care and financial implications. Emergency physicians have been strong proponents in advancing the cause of specialty training. The inclusions of physician assistants and nurse practitioners in the ED must also be met with a commitment to specialty training and demonstrated competencies in the care of emergency patients.

AEM Education and Training 2021;5:1–10

The authors have no relevant financial information or potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supervising Editor: Stephen J. Cico, MD, MEd.

References

- 1. Menchine MD, Wiechmann W, Rudkin S. Trends in midlevel provider utilization in emergency departments from 1997 to 2006. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:963–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Phillips AW, Klauer KM, Kessler CS. Emergency physician evaluation of PA and NP practice patterns. JAAPA 2018;31:38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown DF, Sullivan AF, Espinola JA, Camargo CA Jr. Continued rise in the use of mid‐level providers in US emergency departments, 1993‐2009. Int J Emerg Med 2012;5:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nelson SC, Hooker RS. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners in rural Washington emergency departments. J Physician Assist Educ 2016;27:56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hall MK, Burns K, Carius M, Erickson M, Hall J, Venkatesh A. State of the National Emergency Department Workforce: who provides care where? Ann Emerg Med 2018;72:302–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2017 to 2032. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wiler JL, Rooks SP, Ginde AA. Update on midlevel provider utilization in U.S. emergency departments, 2006 to 2009. Acad Emerg Med 2012;19:986–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Education . 2019. Available at: https://www.aaenp‐natl.org/education. Accessed on April 8, 2019.

- 9. 5th Edition Revision of Criteria for Evaluation of Nurse Practitioner Programs: A Report of the National Task Force on Quality Nurse Practioner Education. National Task Force on Quality Nurse Practioner Education. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. By the Numbers: Program Report 33: Data from the 2017 Program Survey. 2018. Available at: https://paeaonline.org/wp‐content/uploads/2018/10/program‐report‐33‐20181012.pdf.

- 11. Accrediation Standards for Physcian Assistant Education. 2010. Available at: http://www.arc‐pa.org/wp‐content/uploads/2016/10/Standards‐4th‐Ed‐March‐2016.pdf.

- 12. Emergency Medicine Physician Assistant Postgraduate Training Program Standards. 2015. Available at: https://www.sempa.org/. Accessed Xxxx XX, XXXX.

- 13. EMPA Education Data. Available at: https://www.sempa.org/practice‐management/empa‐education‐data. Accessed Sep 28, 2018.

- 14. Chekijian SA, Elia TR, Monti JE, Temin ES. Integration of advanced practice providers in academic emergency departments: best practices and considerations. AEM Educ Train 2018;2:S48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. American Academy of Nurse Practitioners Certification Board, 2018. Annual Report. Available at: https://www.aanpcert.org/certs/pass. Accessed Jul 21, 2019.

- 16. FAQs – Emergency NP Certification. Available at: https://www.aanpcert.org/faq‐enp. Accessed Oct 20, 2017.

- 17. EMERGENCY MEDICINE CAQ . 2019. Available at: https://www.nccpa.net/emergencymedicine. Accessed Jul 23, 2019.

- 18. Specialty Certificates of Added Qualifications (CAQ) Exams. 2014. Available at: https://doseofpa.blogspot.com/2014/12/certificates‐of‐added‐qualification‐caq.html?m=1. Accessed Oct 16, 2019.

- 19. CanMEDS: Better Standards, Better Physicians, Better Care. 2019. Available at: http://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/canmeds‐framework‐e. Accessed Sep 14, 2019.

- 20. AANP State Practice Environment. Available at: https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/state/state‐practice‐environment. Accessed Aug 27, 2019.

- 21. Hooker RS, Everett CM. Physician Assistants: Policy and Practice. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis Company, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hooker RS. Is physician assistant autonomy inevitable? JAAPA 2015;28:20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Indian Health Service Updates PA Practice, Giving PAs “Autonomy in Medical Decision‐Making”. 2019. Available at: https://www.aapa.org/news‐central/2019/08/indian‐health‐service‐updates‐pa‐practice‐giving‐pas‐autonomy‐in‐medical‐decision‐making/. Accessed Aug 28, 2010.

- 24. Full Practice Authority and Responsibility Survey Report: Report to the Joint Task Force on the Future of PA Practice Authority AAPA, 2017. Available at: https://www.aapa.org/wp‐content/uploads/2018/07/fpar‐report‐state‐final.pdf. Accessed Xxxx XX, XXXX.

- 25. Physician Assistants H‐35.989. Available at: https://policysearch.ama‐assn.org/policyfinder/detail/H‐35.989?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml‐0‐2996.xml. Accessed Oct 16, 2019.

- 26. Guidelines Regarding the Role of Physician Assistants and Advanced Practice Registered Nurses in the Emergency Department. 2013. Available at: https://www.acep.org/patient‐care/policy‐statements/guidelines‐regarding‐the‐role‐of‐physician‐assistants‐and‐advanced‐practice‐registered‐nurses‐in‐the‐emergency‐department/. Accessed Aug 28, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27. AAEM Takes a Stand on the Role of APPs in ED. 2019. Available at: https://www.aaem.org/current‐news/aaem‐takes‐a‐stand‐on‐the‐use‐of‐apps‐in‐ed. Accessed Aug 28, 2019.

- 28. AAPA Responds to AAEM Position Statement on Advanced Practice Providers. Available at: https://www.aapa.org/news‐central/2019/02/aapa‐responds‐aaem‐position‐statement‐advanced‐practice‐providers/. Accessed Aug 28, 2019.

- 29. SEMPA Offers Support, Clarification for AMA President Dr. Steven Stack’s Comments on Advanced Practice Providers. 2015. Available at: https://www.acepnow.com/article/sempa‐offers‐support‐clarification‐for‐ama‐president‐dr‐steven‐stacks‐comments‐on‐app/. Accessed Aug 28, 2019.

- 30. Standards of Practice for Nurse Practitioners. 2013. Available at: https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/advocacy‐resource/position‐statements/standards‐of‐practice‐for‐nurse‐practitioners. Accessed Aug 28, 2019.

- 31. Emergency Nurse Practitioners. 2018. Available at: https://www.ena.org. Accessed Aug 28, 2019.

- 32. Auerbach DI, Staiger DO, Buerhaus PI. Growing ranks of advanced practice clinicians – implications for the physician workforce. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2358–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Aledhaim A, Walker A, Vesselinov R, Hirshon JM, Pimentel L. Resource utilization in non‐academic emergency departments with advanced practice providers. West J Emerg Med 2019;20:541–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Counselman FL, Graffeo CA, Hill JT. Patient satisfaction with physician assistants (PAs) in an ED fast track. Am J Emerg Med 2000;18:661–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jeanmonod R, Delcollo J, Jeanmonod D, Dombchewsky O, Reiter M. Comparison of resident and mid‐level provider productivity and patient satisfaction in an emergency department fast track. Emerg Med J 2013;30:e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hamden K, Jeanmonod D, Gualtieri D, Jeanmonod R. Comparison of resident and mid‐level provider productivity in a high‐acuity emergency department setting. Emerg Med J 2014;31:216–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pavlik D, Sacchetti A, Seymour A, Blass B. Physician assistant management of pediatric patients in a general community emergency department: a real‐world analysis. Pediatr Emerg Care 2017;33:26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aaronson E, Borczuk P, Benzer T, Mort E, Temin E. 72h returns: a trigger tool for diagnostic error. Am J Emerg Med 2018;36:359–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tsai CL, Sullivan AF, Ginde AA, Camargo CA Jr. Quality of emergency care provided by physician assistants and nurse practitioners in acute asthma. Am J Emerg Med 2010;28:485–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brock DM, Nicholson JG, Hooker RS. Physician assistant and nurse practitioner malpractice trends. Med Care Res Rev 2017;74:613–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gifford A, Hyde M, Stoehr JD. PAs in the ED: do physicians think they increase the malpractice risk? JAAPA 2011;24:6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]