Abstract

Organizational health literacy involves the health care organizations’ ability to establish an empowering and co-creating relationship with patients, engaging them in the design and delivery of health services in collaboration with health professionals. Although scholars agree that organizational health literacy contributes to health promotion and risk prevention via patient empowerment, literature is not consistent in depicting the interplay between organizational health literacy and preventive medicine. The article intends to shed light into this issue, summarizing current knowledge about this topic and advancing avenues for further development. A narrative literature review was performed through a systematic search on PubMed®, Scopus®, and Web of Science™. The review focused on 50 relevant contributions. Organizational health literacy triggers the transition towards a patient-centered approach to care. It complements individual health literacy, enabling patients to actively participate in health promotion and risk prevention as co-producers of health services and co-creators of value. However, many obstacles – including lack of time and limited resources available – prevent the transition towards health literate health care organizations. Two initiatives are required to overcome extant barriers. On the one hand, a health literate workforce should be prepared to increase the institutional ability of health care organizations to empower and engage patients in health co-creation. On the other hand, increased efforts should be made to assess organizational health literacy and to make its contribution to preventive medicine explicit.

Keywords: Health literacy, Organizational health literacy, Patient empowerment, Patient engagement, Preventive medicine

Introduction

Background

Literature has proposed manifold interpretations of preventive medicine [1,2]. Divergences across propositions of what should be ultimately meant for preventive medicine led to a sort of identity crisis in this discipline [3]. Such a weak identification clashes with the arguments of those who maintain that a larger role should be acknowledged to preventive medicine in order to address the novel challenges faced by healthcare systems in developed and developing countries [4], including: population aging, epidemiological transition, and unequal access to health promotion and risk prevention services [5]. In an attempt to reconcile the diverging conceptualizations that can be retrieved in scientific literature, it can be argued that preventive medicine primarily aims at achieving the absence of communicable and non-communicable diseases, involving medical practices and interventions intended to hamper the spread of illnesses and to promote individual and collective health. This is possible either by anticipating – and, therefore, preventing – the emergence of a disease or by timely addressing it and curbing complications for individuals and communities [6]. From this point of view, preventive medicine should be understood as a twofold concept. On the one hand, it consists of primary prevention initiatives, that serve the purposes of promoting health and avoiding the decline of individual and collective wellbeing due to the spread of diseases. On the other hand, it involves secondary and tertiary prevention interventions, which are intended to preserve good health conditions by detecting the triggers of sickness and by effectively treating them to minimize risks for individual and collective health [7]. In sum, preventive medicine sticks to a salutogenesis approach, which focuses on health and salutary factors and privileges the achievement of psycho-physical wellbeing in the health-disease continuum. Therefore, it aims at empowering and engaging people to deal with the multiple risk factors that may undermine their health status [8]. In line with these considerations, preventive medicine cannot be conceived as the province of health professionals who devote their activity to health promotion and to disease prevention. It necessarily involves the population as a whole, engaging people in a comprehensive strategy for improving individual and collective health [9]. The transition to a digital society further emphasizes the need for involving people in the co-creation of health promotion and risk prevention initiatives, redefining the conventional boundaries of preventive medicine [10].

Over the past few years, an increasing attention has been paid to health literacy as a way to empower people and to make them aware of their contribution to risk prevention and health promotion [11]. In general terms, health literacy concerns the ability of people to obtain, collect, evaluate, process, understand, and use available health information and health-related services to make appropriate decisions about their psycho-physical wellbeing. It also encompasses the skills and competencies that are required to deal with the evolving health systems’ demands and to establish a bridge between informed decisions and consistent actions intended to health promotion and risk prevention [12-14]. While the conventional health literacy concept recognizes that people have an important stake in pursuing the aims that are attached to preventive medicine [15], it overlooks that they need to establish a co-creating partnership with health professionals in order to effectively participate in the co-production of health [16]. However, health literacy is necessary, but it is not sufficient to make people able to have an active role in preventive medicine [17]. The process of empowerment enacted by individual health literacy should be accompanied by an increased ability and a greater willingness of health professionals and organizations to engage people in a fully-fledged co-creating strategy for achieving health promotion and risk prevention [16]. This gives birth to organizational health literacy as an emerging concept aimed at filling in the gap between health literate healthcare organizations and people in a perspective of health services’ co-production and value co-creation [18].

Study Purpose and Rationale

Organizational health literacy contextualizes the health literacy concept to healthcare organizations and, more generally, to healthcare systems. Organizational health literacy broadly refers to the capability and willingness of healthcare organizations to make it easy for people to access the information they need to effectively navigate the healthcare system and to make appropriate and timely health-related decisions which are consistent with their particular health needs. Besides, organizational health literacy encompasses the design of easy accessible health promotion and risk prevention services, which sustain the individual ability to participate in the co-creation of value and ensure the engagement in health services’ co-production of people, according to their specific health literacy skills [19]. Literature has identified ten attributes that characterize a health literate healthcare organization [20], including: 1) a committed leadership recognizing the centrality of health literacy for the mission of healthcare organizations; 2) a special focus on health literacy in planning and designing health promotion and risk prevention initiatives; 3) the arrangement of special training activities on health literacy for the health care workforce; 4) the engagement of people in the co-design and co-delivery of health services; 5) the development of multiple tailored communication strategies and approaches that fit with the skills and competencies of people; 6) the assessment of people understanding at any point of contact with the providers of care; 7) the delivery of easy-to-access and easy-to-understand health-related information; 8) the design of heterogeneous communication tools, ensuring the ability of people to absorb as much information as possible and to interact with them; 9) a particular concern for health literacy to manage high-risk situations for health; and 10) clear communication on the potential charges billed by healthcare organizations for the delivery of health promotion and risk prevention services [21].

Scholars agree that the combination of individual health literacy and organizational health literacy is required to establish a fair, responsive, and well-functioning healthcare system, which relies on the conjoint contribution of healthcare organizations and people to promote the individual and collective psycho-physical wellbeing [22,23]. However, to the best of the author’s knowledge, still little is known about the potential contribution of organizational health literacy to the achievement of the key aims of preventive medicine. This is surprising, since literature has recognized that individual health literacy may significantly contribute to the enhancement of health outcomes by fostering patient empowerment and stimulating active involvement in the co-production of care [24-26]. This article intends to fill in this gap, providing a critical overview of the extant scientific research in the field of organizational health literacy and envisioning its connection with preventive medicine. For this purpose, a narrative and interpretive literature review was accomplished. It attempted to answer the following research questions:

R.Q. 1: How does organizational health literacy contribute to the achievement of health promotion and risk prevention?

R.Q. 2: What are the facilitators and the barriers that affect the transition towards an organizational health literate approach to health promotion and risk prevention?

The article is organized as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the study methods, describing the process of items’ collection and the screening procedure that was implemented to select relevant scientific contributions to be included in this literature review. Section 3 reports the research findings. The study results are articulated in five sub-sections, which advance a tentative answer to the research questions that inspired this article. Section 4 critically discusses the research findings, outlining several avenues for further development. Section 5 ends the paper, summarizing its main conceptual and practical implications.

Methods

An ad-hoc research protocol was designed to conduct this narrative and interpretive literature review. Since this study fell at the intersection of medicine and management, the methodological approach proposed by Tranfield et al. [27] was adopted. More specifically, the study design was threefold and consisted of a planning stage, an implementation stage, and a reporting stage. In the first stage, the need for a literature review was assessed and a tailored research design was arranged. In the second step, literature was screened and relevant contributions collected and analyzed. In the third step, relevant items were systematized according to a critical interpretive approach. A limited level of formality and standardization was used. In fact, an excess of formalization constrains the researcher’s ability to draw new ideas and interpretive perspectives from the literature review. A narrative technique was undertaken to report collected evidence, shedding light into current streams of research and envisioning perspectives for further development [28].

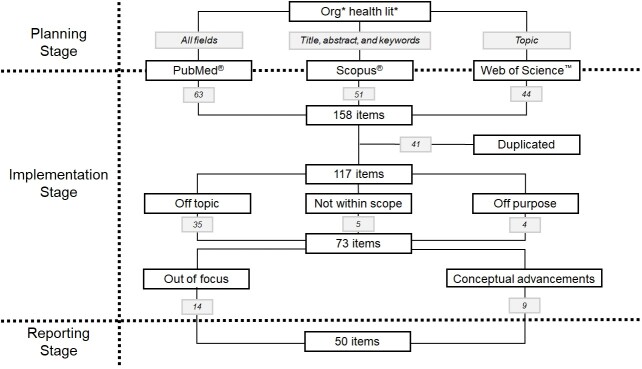

Figure 1 shows a flowchart which graphically depicts the three steps of this literature review. In the planning stage the need for a review about the role of organizational health literacy in preventive medicine was assessed. Since 2016, four literature reviews in the field of health literacy have been published. However, none of them overlapped with the purposes of this study. More specifically, these reviews focused on: the structural design of health literate healthcare organizations [29]; the theories and the frameworks that try to conceptualize organizational health literacy [30]; the strategies for developing an organizational health literacy approach [31]; and the implementation of organizational health literacy strategies [32]. While [29] and [30] adopted a metanarrative design which primarily focused on the conceptualization of organizational health literacy, [31] and [32] disclosed a different approach: the former reviewed seven empirical papers to collect evidence for effective interventions to establish health literate healthcare organizations; the latter proposed a realist review of 17 papers to shed light into factors affecting the successful implementation of organizational health literacy interventions. This supported the originality and the timeliness of the literature review here proposed. After eliciting the novelty of this literature review, the search strategy for collecting the highest number of potentially relevant contributions was defined. The keyword “org* health lit*” was identified as a comprehensive research string to delve into relevant contributions published in both the scientific and the professional literatures. The use of the asterisk allowed to search for the variations of organizational/organisational-related topics and for both health literacy and health literate-related items.

Figure 1.

The flow chart depicting the study protocol.

In the implementation stage, the sources for items’ collection and the screening criteria were set. Three academic sources were concomitantly queried. PubMed® currently represents the largest citation database for biomedical literature. It indexes more than 30 million items published in major life science journals across the world. Scopus® is one of the largest generic citation databases: it lists more than 75 million items in the field of social sciences, physical sciences, life sciences, and health sciences coming from more than 5,000 publishers. Lastly, Web of Science™ is considered to be one of the richest and most trusted citation databases for conducting literature reviews, recording more than 170 million items. The search strategy was tailored to the search engines embedded in these three citation sources. The last query was performed on July 20th, 2020. The search string was run for “all fields” in PubMed®: it returned 63 items. It was performed for “Title, abstract, and keywords” in Scopus®, providing 51 hits. Lastly, in Web of Science™ the research string was typed in the field “Topic,” leading to the collection of 44 records. Therefore, 158 items were initially obtained. A preliminary screening on titles and authors’ names was accomplished to identify duplicates and redundancies. This check led to the withdrawal of 41 duplicated records. In sum, the analysis focused on 117 potentially relevant items.

Next, drawing on the specific purposes that inspired this article, the criteria for items’ screening were developed. In particular, two stages of screening were envisioned. Firstly, the titles, keywords, and abstracts of collected records were carefully analyzed to determine their consistency with the study aims. Three exclusion criteria were followed: 1) the items which included only indirect and sporadic references to organizational health literacy were discarded as “off topic;” 2) the items primarily focusing on health literacy and incidentally referring to organizational health literacy as an avenue for further research were removed as “not within scope;” and 3) the items which discussed issues related to organizational health literacy but did not provide any insightful remark on its role to achieve health promotion and/or risk prevention were rejected as “off purpose.” As a result of this first screening, 44 items were dropped. Going more into details, 35 were removed because of criterion 1), five were removed because of criterion 2), and four were removed because of criterion 3). As a result, 73 records were admitted in the second stage of screening.

The second screening concerned the full text of available records. Two inclusion criteria were adopted. On the one hand, only papers which provided compelling and practical arguments on the contribution of organizational health literacy to health promotion and risk prevention were included in the study. Conceptual papers which did not include insightful evidence into the contribution of organizational health literacy to the enhancement of individual and collective wellbeing were removed from the analysis. On the other hand, only records which developed intriguing points to answer the research questions against which this literature review was conceived were considered to be relevant. That is to say, items which did not show either a direct or an indirect connection with the three research questions of this article were rejected. After this in-depth analysis, 23 items were excluded. In particular, 14 items were not significantly related with the main focus of this article; six were conceptual papers proposing theoretical advancements on the conceptualization and the understanding of organizational health literacy; three were reports which did not contribute to feeding the debate about the role of organizational health literacy in health promotion and risk prevention.

In sum, this literature review contemplated 50 papers, which were critically analyzed in the reporting stage. The majority of them (86%) were articles published in peer reviewed journals: six were review papers which investigated the attributes and the implications of organizational health literacy and 36 were articles providing conceptual and empirical evidence about organizational health literacy. Also, seven conference proceedings were taken into consideration. A thorough analysis of conference proceedings was conducted to assess their reliability and consistency. Where necessary, corresponding authors were contacted to obtain additional information on study attributes and additional developments. Lastly, two book chapters were part of this literature review. As previously anticipated, an interpretive approach was used for reporting the study findings. A manual coding technique was used to sort the records in five clusters, which advanced an answer to the research questions that inspired this study. A narration of the five clusters follows: it allows us to summarize the state of the art in the field of organizational health literacy and to illuminate some promising avenues for further research.

Findings

Overview of the Literature

Table 1 provides an overview of the literature which was evaluated in this study. It briefly summarizes the contents of the five main themes that were retrieved from this literature review. The first cluster establishes a link between organizational health literacy and the key aims of preventive medicine. Alongside stressing the connections that can be found between organizational health literacy and preventive medicine, it underlines the gaps that divide them. The second cluster goes further in emphasizing the patient-centeredness perspective which is triggered by organizational health literacy. From this point of view, organizational health literacy exhorts the shift from a conceptualization of people as the objects of preventive medicine to their understating as subjects of initiatives aimed at health promotion and risk prevention. The third cluster elicits the institutional and organizational factors that foster the establishment of health literate healthcare organizations, stimulating health professionals to engage people in a co-creating relationship. In this vein, the fourth cluster focuses on the need to prepare the health care workforce for accomplishing the transition toward health literate healthcare organizations. Lastly, yet importantly, cluster five highlights that additional efforts are needed to measure the contribution of organizational health literacy to health promotion and risk prevention, in an attempt to boost the institutional and organizational desirability of organizational health literacy promotion initiatives.

Table 1. An overview of the research items’ clusterization.

| Cluster no. | Main theme | Key contents | Key references |

| Cluster no. 1 | Understanding organizational health literacy as a preventive health policy issue | Organizational health literacy involves the ability of health care organizations to: 1) integrate health literacy into their policies and daily activities; 2) acknowledge the multifaceted needs of people served, 3) design and implement tailored strategies aimed at enhancing the patient-provider relationship; and 4) to engage people in the delivery of health prevention and promotion services. It derives from a mix of proactive behaviors by health care professionals, health literate organizational policies and procedures by health care institutions, and collective mindsets targeted towards value co-creation by patients and caregivers. Two gaps prevent from recognizing and emphasizing the contribution of organizational health literacy to health promotion and risk prevention: lack of unanimous understanding about what should be meant by organizational health literacy and limited efforts addressed to the assessment of organizational health literacy. | [35,36,37,38,39] |

| Cluster no. 2 | Contextualizing organizational health literacy in a patient-centered care perspective | Organizational health literacy has been usually handled as a managerial artefact, which has been disconnected from the willingness of health professionals to engage patients as active partners in the efforts towards health promotion and risk prevention. Nevertheless, organizational health literacy is strictly related to the enhancement of health care organizations’ meaningfulness. It involves a redesign of structures and procedures implemented by health care organizations in order to support the ability of patients to navigate the health service system and to effectively function within it for the purposes of health promotion and risk prevention. From this standpoint, organizational health literacy acts as a trigger of patient empowerment: it enacts the cycle of patients’ enablement, activation, engagement, and involvement, which leads to patient-centeredness and to the establishment of a co-creating relationship between patients and health professionals. | [40,41,43,46,49] |

| Cluster no. 3 | Building the desirability for achieving organizational health literacy | Lack of desirability for achieving organizational health literacy derives from two main sources: 1) health professionals have been found to be unaware of the importance of organizational health literacy for the purposes of health promotion and risk prevention; and 2) a pronounced variation characterizes the communication strategies, protocols, and tools used by health professionals during the patient-provider encounter, making it difficult to define homogeneous approaches to support organizational health literacy. To overcome these obstacles and to build a greater desirability for organizational health literacy, health care organizations have to design a co-creational strategy, which relies on the involvement of the whole workforce in the reconfiguration of the modes of interaction between patients and health professionals. The co-creational strategy to awaken the desirability for organizational health literacy requires a wrap-around approach, which conceives patient empowerment and patient participation as the main aims of health care organizations. | [50,51,52,55,57] |

| Cluster no. 4 | Preparing a health literate workforce | A proactive approach is needed to tackle potential flaws in the health professionals’ willingness to establish a co-creating relationship with patients. The proactive approach is based on tailored training activities, which are intended to prepare the workforce to deal with issues related to organizational health literacy. Strategies to prepare a health literate workforce are pooled by their composite nature, consisting of both formal and informal initiatives. While formal initiatives are aimed at fostering the institutional acceptability of organizational health literacy, informal initiatives are intended to propel commitment and enthusiasm for organizational health literacy amongst health professionals. | [29,63,64,65,67] |

| Cluster no. 5 | Measuring efforts and outcomes related to organizational health literacy | A systematic approach should be embraced to measure organizational health literacy. It should focus on the factors that contribute to the enhancement of the ability of health care organizations to engage the patients in the co-production of health services, including: the quality of verbal and written information, the friendliness of supportive services provided to patients, the availability of patient-centered technologies to enhance the patient-provider relationship, and the effectiveness of policies and procedures to boost patient empowerment and involvement in health promotion and prevention. | [69,72,73,74,78] |

Understanding Organizational Health Literacy as a Preventive Health Policy Issue

Patient empowerment and their active involvement in health services’ co-production and value co-creation are two requisites for achieving the two overarching aims of preventive medicine, that is to say the promotion of psycho-physical wellbeing and the prevention of diseases. While individual health literacy, health education, and healthy lifestyle should be understood as necessary ingredients of the recipe for empowering people and engage them in the design and delivery of health promotion services, they do not suffice. Organizational health literacy, that involves the ability of healthcare organizations to integrate health literacy into their policies and daily activities, to acknowledge the multifaceted needs of people served, and to design and implement tailored strategies aimed at enhancing the patient-provider relationship, is also required for this purpose [33]. Organizational health literacy is the result of a mix of health literate organizational policies, management practices intended to boost patient-centeredness, and health care professionals’ collective mindsets and proactive behaviors targeted towards health services’ co-production and value co-creation [16]. Such a mix enables the active participation of people in the design and delivery of care and acknowledges their crucial role in health promotion and risk prevention [34].

Even though literature is consistent in maintaining the importance of organizational health literacy to achieve health promotion and risk prevention [11], it has been argued that two gaps prevent us from fully recognizing and emphasizing its factual contribution to the accomplishment of the purposes that characterize preventive medicine. On the one hand, lack of unanimous understanding of what should be meant by organizational health literacy does not allow us to definitively unravel the initiatives realized by healthcare organizations to empower people and to engage them in health services’ co-production and value co-creation [35]. On the other hand, limited efforts addressed to the assessment of organizational health literacy prevent us from gauging the ability of health professionals to involve people in strategies and purposive actions targeted to health promotion and risk prevention [36]. This is surprising, since literature has stressed that both people and health professionals may lack the skills and the competencies to establish sound and co-creating partnerships intended to the co-production of health services. In this circumstance, the implementation of patient engagement interventions may have side effects on health outcomes, paving the way for co-destruction – rather than co-creation – of value [37].

Previous studies have identified several barriers which undermine the capability of healthcare organizations to raise their organizational health literacy. Inter alia, such barriers include limited cross-sectoral collaborations among different health specializations and limited perceived importance attached to health-literacy-related issues [38]. Parker and Hernandez [39] recommended several interventions that are crucial to overcome these barriers, paving the way for the enhancement of organizational health literacy. Such interventions include: 1) the contextualization of organizational health literacy in a patient-centered care perspective; 2) the creation of a desirability for becoming a health literate healthcare organization; 3) the preparation of a health literate workforce; and 4) the assessment of organizational health literacy efforts and outcomes. As depicted below, these four themes matched the contents of the remaining four clusters which were retrieved in this literature review.

Contextualizing Organizational Health Literacy in a Patient-centered Care Perspective

Even though healthcare organizations have been generally found to self-rate their organizational health literacy capabilities as adequate, health professionals have claimed to meet some relevant difficulties in developing effective communication tools to establish sound and meaningful relationships with people. Besides, health professionals may suffer from lack of time and limited expertise, that prevent them from providing people with tailored supportive services to enhance their self-management skills and to empower them as health services’ co-producers and value co-creators [40]. This supports the arguments of those who maintain that organizational health literacy has been generally handled as a management artifact, which has been disconnected from the willingness of health professionals to engage patients as partners in the efforts towards health promotion and risk prevention [41].

Embracing a patient-centered perspective, organizational health literacy should be taken into consideration at any point of contact between health professionals and people. Health literate healthcare organizations should arrange a set of interventions aimed at improving the exchange of information between health professionals and people, enabling the latter to actively participate in the design and in the delivery of health promotion and risk prevention initiatives [42]. From this standpoint, organizational health literacy is strictly related to the enhancement of healthcare organizations’ meaningfulness [43]. It involves a redesign of structures and procedures implemented by healthcare organizations in order to support the ability of patients to navigate the healthcare system and to effectively function within it for the purposes of health promotion and risk prevention [11].

Echoing these considerations, literature has acknowledged the contribution of organizational health literacy to patient-centeredness. Firstly, organizational health literacy acts as a trigger of individual empowerment. More specifically, it enacts the cycle of patients’ enablement, activation, engagement, and involvement, which leads to the establishment of a co-creating relationship between health professionals and people [44]. For this to happen, health professionals have to adopt an enabling – rather than a caring – approach, which is intended to provide the patients with the information, skills, and capabilities they need to actively participate in the design and delivery of health promotion and risk prevention services [45]. Secondly, since organizational health literacy allows people to better understand their health-related needs and to timely identify the providers of health services who are able to meet their demand of care, it is a determinant of satisfaction with health services, which further encourages the active involvement of people in the functioning of the healthcare system, boosting the transition towards patient-centeredness [46]. Thirdly, stimulating self-care and self-management of individual health conditions, organizational health literacy paves the way for a personalized approach to care, sustaining a systemic action of healthcare organizations which is framed around the distinguishing health-related needs of people [47]. Fourthly, organizational health literacy has been claimed to increase the equitability of the healthcare system, implying a special focus for those who possess inadequate skills and capability to access health services and to participate in health protection and risk prevention initiatives. In turn, equitability acts as a catalyst of patient-centeredness, motivating people to establish a co-creating relationship with health professionals [48]. Fifthly, and lastly, organizational health literacy engenders the development of a participatory health setting for fragile people, supporting them to make sense of their health needs and to play an active role in the initiatives targeted to the promotion of their wellbeing and to the prevention of risks for health [49].

Sustaining the Achievement of Organizational Health Literacy

Two main factors have been argued to prevent a nimble transition towards health literate healthcare organizations. On the one hand, a pronounced variation characterizes the communication strategies, protocols, and tools used by health professionals in their interaction with people, making it difficult to define homogeneous approaches to support organizational health literacy; on the other hand, health professionals have been found to be not fully aware of the importance of organizational health literacy for the purposes of health promotion and risk prevention [50]. The conjoint action of these two factors discourages systemic interventions intended to establish a health literate healthcare organization: in particular, it nurtures the attachment of low priority to issues related to organizational health literacy, lessens the commitment of health professionals to the enhancement of organizational health literacy, and legitimizes the allocation of inadequate resources to actions targeted to patient empowerment [51].

To overcome these obstacles and to build a greater desirability for organizational health literacy, healthcare organizations have to design a co-creational strategy, which relies on the involvement of the whole workforce in the reconfiguration of the modes of interaction between health professionals and people [52]. Such a co-creational strategy has a twofold advantage for healthcare organizations. Firstly, it permits us to implement a whole organization approach to the promotion of organizational health literacy, which acknowledges local needs and peculiarities and makes an effort to address them to enhance the provision of care. Secondly, it fosters the responsiveness of healthcare organizations to the evolving expectations of people, paving the way for their active involvement in the design and delivery of care [53].

The co-creational strategy to awaken the desirability for organizational health literacy requires a wrap-around approach, which conceives empowerment and involvement of people as the main aims of healthcare organizations [54]. The wrap-around approach should address the key triggers that foster the responsiveness of healthcare organizations towards organizational health literacy, including: 1) external support to empowerment initiatives addressed to individuals and groups; 2) internal support deriving from a committed leadership and an organizational culture focused on people engagement; 3) the redesign of policies, processes, and procedures in a perspective of patient-centeredness; 4) the enhancement of equity and fairness in the access to health promotion and risk prevention services; 5) the personalization of communication strategies and approaches; 6) the ad-hoc preparation of the workforce to address health literacy-related issues; and 7) the establishment of a co-creating relationship between healthcare organizations and the community [55].

In line with these arguments, previous research has identified several interventions which uphold the desirability for organizational health literacy and pave the way for increased people participation in health services’ co-production and value co-creation. Among others, such interventions include: a stepwise implementation of initiatives intended to build internal support for people involvement in health promotion and risk prevention initiatives [56]; the development and the diffusion of best practices, protocols, and recommendations to encourage the establishment of a sound relationship between health professionals and people [57]; and the provision of tailored supportive services to health professionals, in order to sustain them in dealing with the challenges related to organizational health literacy [58].

Preparing a Health Literate Workforce

The workforce of healthcare organizations is at the forefront of interventions directed to empower patients and to boost organizational health literacy. However, due to the institutional obstacles and organizational barriers which hamper the transition towards health literate healthcare organizations, literature has claimed that health professionals may suffer from falls in morale and job satisfaction which are detrimental to the achievement of organizational health literacy [59]. This is especially true when health professionals face unprecedented health challenges, such as the COVID-19 epidemic. In these cases, worry of losing control and concerns for self-health may undermine their responsiveness and, consequently, their ability to factually contribute to patient empowerment [60]. A proactive approach is needed to tackle potential flaws in the health professionals’ willingness to establish a co-creating relationship with patients. Such a proactive approach is based on tailored training activities [43], which are intended to prepare the workforce to deal with issues related to organizational health literacy [61].

Lloyd et al. [31] argued that a paucity of strategies has been proposed in literature to prepare the workforce to participate in the establishment of health literate healthcare organizations. These strategies are pooled by their composite nature, consisting of both formal and informal initiatives [29]. The former are aimed at fostering the institutional acceptability of organizational health literacy, while the latter are intended to propel commitment and enthusiasm for organizational health literacy amongst health professionals [62]. Formal interventions are primarily targeted to the structural factors that are required to increase the workforce capability to empower people and to engage them in initiatives intended for health promotion and risk prevention. Organizational change in a perspective of patient-centeredness and a leadership committed to organizational health literacy represent the major structural factors that are conducive to health literate healthcare organizations [63]. Organizational change is aimed at increasing the meaningfulness of healthcare organizations, setting the conditions for the active involvement of people in a co-creating relationship with health professionals [29]. A committed leadership serves the purposes of overcoming resistances to change and emboldening a bottom-up approach to care which aims at patient-centeredness [64]. Informal interventions look at the dominant, but underground mechanisms which are quintessential for the success of organizational health literacy. More specifically, they focus on the health literacy expertise of the workforce, the tacit knowledge of issues related to organizational health literacy, and the shared responsibility for the implementation of patient empowerment interventions [32].

Even though formal and informal initiatives are conjointly needed to prepare the workforce and to boost organizational health literacy, it can be argued that the latter have an enabling role towards the former [65]. Going more into details, informal interventions are instrumental to the creation and the development of an open organizational culture, which recognizes the importance of people empowerment and involvement for the purposes of health promotion and risk prevention and acts as an enabler of change within healthcare organizations [66]. Besides, they enact a whole organization approach to patient empowerment, sustaining the principles of collaboration and coordination among the providers of care who participate in the design and delivery of health promotion and risk prevention services [67]. Last, but not least, informal interventions are key to arouse the executives’ support and the motivation of health professionals to the enhancement of organizational health literacy [68].

Measuring Efforts and Outcomes Related to Organizational Health Literacy

The assessment of organizational health literacy is crucial to check if healthcare organizations are effective in empowering patients and establishing a co-creating partnership with them for the purposes of health promotion and risk prevention. Most of available measures to gauge organizational health literacy are based on self-assessment tools, which are at risk of being biased by subjective ratings and unobjective evaluations of respondents [69]. Moreover, only in few circumstances the assessment of organizational health literacy has been related to the enhancement of health services’ quality or to the achievement of increased outcomes in terms of health promotion and risk prevention [70]. Literature consistently claims that a systematic approach should be embraced to measure organizational health literacy and to stress its contribution to the achievement of the distinguishing aims of preventive medicine [11]. Such a systematic approach should focus on the different factors that contribute to the enhancement of the healthcare organizations’ capability to engage people in the co-production of health promotion and risk prevention services, including: the quality of verbal and written information, the timeliness of supportive services provided to people in order to enhance their ability to navigate the healthcare system, the availability of patient-centered technologies to enhance the relationship between health professionals and people, and the effectiveness of organizational policies and procedures to boost people empowerment and involvement in health promotion and risk prevention initiatives [71].

Scholars have argued that there is a divide between the health professionals’ self-assessment of organizational health literacy levels and the patients’ perceived ability to navigate the healthcare system [72]. In an attempt to fill in this gap, the patients’ perspective should be embedded in the measurement of organizational health literacy: this permits us to obtain reliable assessment of the health professionals’ ability to empower and engage patients [73]. Echoing these considerations, Trezona et al. [74] recently argued that the assessment of organizational health literacy should be twofold. On the one hand, it should measure the quality of systems, tools, and roles that foster the transition towards patient-centeredness. On the other hand, it should focus on the organizational capability to set the conditions for friendly and effective interactions between health professionals and people, paving the way for an increased engagement of the community served in the provision of health promotion and risk prevention services. From this standpoint, the measurement of organizational health literacy should be conducted in a broader view [75], looking at the interaction between healthcare organizations and the whole community in light of a population health literacy perspective [76]. Alongside gauging the healthcare organizations’ readiness to implement tailored communication strategies and organizational mechanisms intended to enhance their interaction with patients and to involve them in the co-creation of health [77], assessment tools should provide with reliable and consistent information about the contribution of organizational health literacy in improving the quality of care, in curtailing inequities in the access to health services, and enhancing the patient experience with health promotion and risk prevention services [78,79].

Discussion

The study findings should be read in light of the main limitations which affected this literature review. The focus on organizational health literacy prevented from including in the analysis similar concepts proposed in the health communication and the health care improvement literature which are intended to advance patient-centeredness, including humane healthcare organizations [80] and human-centered healthcare systems [81]. Even though this focus constrained the breadth of this literature review, it was consistent with the study purpose to shed light into the distinguishing role of organizational health literacy in preventive medicine. Moreover, only three sources were queried to collect relevant contributions to be included in this literature review, namely PubMed®, Scopus®, and Web of Science™. While this decision may have reduced the coverage of this study, the search on the currently major academic sources for peer-reviewed literature supports the consistency and the reliability of the research findings [82,83]. Thirdly, the narrative and interpretive approach which was used to report the study results prevented the replicability of this research. Nevertheless, it allowed an original and insightful interpretation of the items included in this literature review.

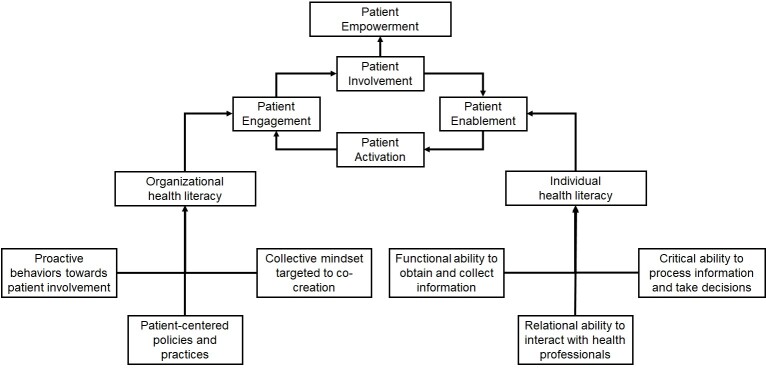

Organizational health literacy should be understood as a complement to individual health literacy in order to set the conditions for patient empowerment and to actively engage people in purposive actions intended to health promotion and risk prevention [64]. While individual health literacy enables people to be involved in the design and delivery of health services [11], organizational health literacy is key to enhance the health professionals’ willingness and responsiveness to establish a co-creating partnership with people, conceiving the latter as service co-producers and value co-creators [23]. More specifically, organizational health literacy contributes to the achievement of health promotion and risk prevention in two ways: firstly, it increases the meaningfulness of healthcare organizations, facilitating people to collect and process the information they need to actively participate in the provision of health services [43]; secondly, it is a fundamental step in the transition towards a patient-centered approach to care, which acknowledges that people are key actors in interventions intended to health promotion and protection [84]. Health literate healthcare organizations result from a collective mindset of health professionals, patients, and caregivers, who accept to collaborate in order to improve the functioning of the healthcare system [19].

Two types of interventions are needed to promote organizational health literacy and to sustain the readiness of health professionals to empower patients and involve them to value co-creation, especially when preventive medicine initiatives are concerned [38]. On the one hand, the desirability for becoming a health literate healthcare organization should be solicited at both the individual and the collective levels [37]. This is possible by envisioning and making explicit the advantages that are brought by people engaged in health promotion and risk prevention. A co-creational strategy is needed for this purpose. In particular, co-creation implies that organizational health literacy should not be handled as a sheer management tool. Rather, it should be understood as a new model of patient-provider relationship, which derives from the readiness of both health professionals and patients to establish a co-creating partnership, as depicted in Figure 2 [53]. Such a partnership allows to account for the local needs that arise during the patient-provider encounter and, at the same time, it is consistent with a whole organization approach, involving the adoption of a patient-centered perspective in reframing the policies, structures, and procedures of health services’ provision [85]. On the other hand, the preparation of a health literate workforce is quintessential to foster the transition towards health literate healthcare organizations. In most of the cases, health professionals face time pressures and lack appropriate tools to assess the special information needs of people who live with limited health literacy. This situation is exacerbated by an institutional environment which focuses on productivity and discourages health professionals from paying attention to the process of patient empowerment [16], as well as by the lack of integration of organizational health literacy into strategies and plans devised by healthcare organizations [86]. Preparing a health literate workforce involve creating awareness among health professionals of the importance of organizational health literacy for the purposes of health protection and risk prevention and delivering to health professionals tailored communication strategies and approaches which are aimed at enhancing people engagement, regardless of the individual health literacy skills of the latter [87].

Figure 2.

The connection between organizational health literacy and individual health literacy.

Lack of evidence about the role of organizational health literacy in achieving the purposes of health promotion and risk prevention represents the main barrier to the transition towards health literate healthcare organizations [88]. Extant measurement approaches are based on subjective assessments and self-rating of organizational health literacy [79,89]. Absence of reliable and consistent measures discourages both policy makers and health managers from acknowledging organizational health literacy as a priority to improve health outcomes and to involve people in interventions addressed to health promotion and risk prevention. Moreover, it does not permit to assess the forecasted positive implications of organizational health literacy on the improvement of equity and fairness in the access to care [56].

Further research is needed to push forward our understanding of organizational health literacy and to illuminate its contribution to the field of preventive medicine. Firstly, additional conceptual advancements are required to develop a homogeneous and consistent definition of organizational health literacy. Moreover, the factors that characterize health literate healthcare organizations should be fully identified, in order to steer the transition of healthcare organizations towards patient-centeredness. From this point of view, future theoretical development should be aimed at pinpointing the building blocks of a health literate healthcare organization and at clarifying the connection between organizational health literacy and health promotion and risk prevention. Secondly, empirical studies are necessary to quantify the contribution of organizational health literacy to preventive medicine. On the one hand, qualitative research is needed to diagnose which kind of organizational health literacy initiatives are more effective in engaging people and in involving them in health promotion and risk prevention initiatives. On the other hand, quantitative research is required to develop consistent and reliable measures of organizational health literacy and to gauge the ability of health literate healthcare organizations to achieve an enhancement of individual and collective wellbeing. Thirdly, and lastly, comparative international studies are needed to investigate how cultural specificities and institutional attributes of different national health systems may affect the design and the implementation of health literate healthcare organizations. Besides, such international research should shed light into how national variations influence the process of patient empowerment and the involvement of people in health promotion initiatives.

Conclusions

The implications of this study are threefold. From a policy perspective, it suggests that individual health literacy and organizational health literacy should be handled as two complementary tools to empower people and to engage them in health promotion and risk prevention. Without organizational health literacy, individual health literacy involves limited responsiveness of health professionals toward the evolving expectations of patients. Conversely, if individual health literacy is missing, organizational health literacy implies the empowerment of people who are unable to actively participate in health services’ provision, engendering value co-destruction rather than co-creation. Therefore, individual health literacy and organizational health literacy should be conjointly embedded in health policy making, emphasizing their crucial role in the field of preventive medicine.

From a managerial perspective, healthcare organizations should reframe their strategies, procedures, and approaches, embracing a patient-centered perspective to become health literate. Organizational health literacy involves a deep reconfiguration of the relationship between health professionals and people, acknowledging that health promotion and risk prevention relies on the engagement of the latter in service co-production and value co-creation. Limited patient involvement and poor collaboration between health professionals and people undermine the effectiveness of organizational health literacy and hampers its contribution to preventive medicine.

Finally, yet importantly, from a professional perspective this literature review stresses the need for developing targeted educational and training activities addressed to health professionals. Such educational activities should focus on the specific challenges raised by organizational health literacy and should increase the awareness of health professionals about the ingredients that are required in the recipe for health literate healthcare organizations. The transition towards organizational health literacy implies a revised patient-provider relationship, which require the introduction of innovative communication strategies and approaches facilitating the empowerment of people and encouraging their engagement in value co-creation.

References

- Winslow CE. Preventive Medicine and Health Promotion: ideals or Realities? Yale J Biol Med. 1942. May;14(5):443–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viseltear AJ. John R. Paul and the definition of preventive medicine. Yale J Biol Med. 1982. May-Aug;55(3-4):167–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung P, Lushniak BD. Preventive Medicine’s Identity Crisis. Am J Prev Med. 2017. March;52(3):e85–9. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull SK. A larger role for preventive medicine. Virtual Mentor. 2008. November;10(11):724–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paccaud F. Rejuvenating health systems for aging communities. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2002. August;14(4):314–8. 10.1007/BF03324456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke EA. What is Preventive Medicine? Can Fam Physician. 1974. November;20(11):65–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neferu R, Yi A. Shifting from picking up the pieces to preventive health. OWOMJ. 2016;85(2):72–3. 10.5206/uwomj.v85i2.4152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jadotte YT, Leisy HB, Noel K, Lane DS. The Emerging Identity of the Preventive Medicine Specialty: A Model for the Population Health Transition. Am J Prev Med. 2019. April;56(4):614–21. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose G. The Strategy of Preventive Medicine Oxford. Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick K. Information technology and the future of preventive medicine: potential, pitfalls, and policy. Am J Prev Med. 2000. August;19(2):132–5. 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00189-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo R. The Bright Side and the Dark Side of Patient Empowerment. Co-creation and Co-destruction of Value in the Healthcare Environment Cham. Springer; 2017. 10.1007/978-3-319-58344-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc Sci Med. 2008. December;67(12):2072–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleasant A, Rudd RE, O’Leary C, Paasche-Orlow MK, Allen MP, Alvarado-Little W, et al. Considerations for a new definition of health literacy. Washington (DC): National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Medicine; 2016. 10.31478/201604a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parnell TA, Stichler JF, Barton AJ, Loan LA, Boyle DK, Allen PE. A concept analysis of health literacy. Nurs Forum. 2019. July;54(3):315–27. 10.1111/nuf.12331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harzheim L, Lorke M, Woopen C, Jünger S. Health literacy as communicative action—a qualitative study among persons at risk in the context of predictive and preventive medicine. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. March;17(5):1718. 10.3390/ijerph17051718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo R. Contextualizing co-production of health care: a systematic literature review. Int J Public Sector Management. 2016;29(1):72–90. 10.1108/IJPSM-07-2015-0125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santos P, Sá L, Couto L, Hespanhol A, Hale R. Health literacy as a key for effective preventive medicine. Cogent Soc Sci. 2017;3(1):1407522. 10.1080/23311886.2017.1407522 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo R, Annarumma C, Adinolfi P, Musella M. The missing link to patient engagement in Italy. J Health Organ Manag. 2016. November;30(8):1183–203. 10.1108/JHOM-01-2016-0011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brach C. The Journey to Become a Health Literate Organization: A Snapshot of Health System Improvement. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2017;240(1):203–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brach C, Keller D, Hernandez LM, Baur C, Parker R, Dreyer B, et al. Ten Attributes of Health Literate Health Care Organizations. Washington (DC): National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Medicine; 2012. 10.31478/201206a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski C, Lee SY, Schmidt A, Wesselmann S, Wirtz MA, Pfaff H, et al. The health literate health care organization 10 item questionnaire (HLHO-10): development and validation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015. February;15(1):47. 10.1186/s12913-015-0707-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan D, Turner B, Trujillo A. Motivation for a health-literate health care system—does socioeconomic status play a substantial role? Implications for an Irish health policymaker. J Health Commun. 2013;18(1 Suppl 1):158–71. 10.1080/10810730.2013.825674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh HK, Brach C, Harris LM, Parchman ML. A proposed ‘health literate care model’ would constitute a systems approach to improving patients’ engagement in care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013. February;32(2):357–67. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK. Health literacy, health inequality and a just healthcare system. Am J Bioeth. 2007. November;7(11):5–10. 10.1080/15265160701638520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011. July;155(2):97–107. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo R, Annarumma C, Adinolfi P, Musella M, Piscopo G. The Italian Health Literacy Project: insights from the assessment of health literacy skills in Italy. Health Policy. 2016. September;120(9):1087–94. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranfield D, Denyer D, Smart P. SmartTowards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br J Manage. 2013;14(3):207–22. 10.1111/1467-8551.00375 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jahan N, Naveed S, Zeshan M, Tahir MA. How to Conduct a Systematic Review: A Narrative Literature Review. Cureus. 2016. November;8(11):e864. 10.7759/cureus.864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo R. Designing health-literate health care organization: A literature review. Health Serv Manage Res. 2016;29(3):79–87. 10.1177/0951484816639741 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farmanova E, Bonneville L, Bouchard L. Organizational Health Literacy: Review of Theories, Frameworks, Guides, and Implementation Issues. Inquiry. 2018. Jan-Dec;55(1):46958018757848. 10.1177/0046958018757848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd JE, Song HJ, Dennis SM, Dunbar N, Harris E, Harris MF. A paucity of strategies for developing health literate organisations: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2018. April;13(4):e0195018. 10.1371/journal.pone.0195018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meggetto E, Kent F, Ward B, Keleher H. Factors influencing implementation of organizational health literacy: a realist review. J Health Organ Manag. 2020. March;ahead-of-print(4 ahead-of-print):385–407. 10.1108/JHOM-06-2019-0167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dageforde LA, Cavanaugh KL. Health literacy: emerging evidence and applications in kidney disease care. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013. July;20(4):311–9. 10.1053/j.ackd.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orebaugh M. Instigating and Influencing Patient Engagement: A Hospital Library’s Contributions to Patient Health and Organizational Success. J Hosp Librariansh. 2014;14(2):109–19. 10.1080/15323269.2014.888511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meggetto E, Ward B, Isaccs A. What’s in a name? An overview of organisational health literacy terminology. Aust Health Rev. 2018. February;42(1):21–30. 10.1071/AH17077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelikan JM. Health literate health care organizations. Pub Health Forum. 2017; 25(1):66-70. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo R, Manna R. What if things go wrong in coproducing health services? Exploring the implementation problems of health care co-production. Policy Soc. 2018;37(3):368–85. 10.1080/14494035.2018.1411872 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlis A, Hornberg C. Identifying barriers to organizational health literacyin public health departments in Germany. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29(4):471–2. [Google Scholar]

- Parker RM, Hernandez LM. What makes an organization health literate? J Health Commun. 2012;17(5):624–7. 10.1080/10810730.2012.685806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruzliakova N, Porter KJ, O’Dell M, Cantrell ES, Counts M, Zoellner J. Understanding and promoting organizational health literacy in a public health setting. In 38th Annual Meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine; 2017; San Diego, CA, p. 2522-2523. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo R. Contextualizing Patient Empowerment. In: Palumbo R. The Bright Side and the Dark Side of Patient Empowerment: Co-creation and Co-destruction of Value in the Healthcare Environment. Cham: Springer; 2017. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hadden K, Prince LY, Barnes CL. Health Literacy Demands of Patient-Reported Evaluation Tools in Orthopedics: A Mixed-Methods Case Study. Qual Manag Health Care. 2018. Apr-Jun;27(2):98–103. 10.1097/QMH.0000000000000165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo R, Annarumma C, Musella M. Exploring the meaningfulness of healthcare organizations: a multiple case study. Int J Public Sector Management. 2017;30(5):503–18. 10.1108/IJPSM-10-2016-0174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo R. The role of health literacy in empowering patients. In: Palumbo R. The Bright Side and the Dark Side of Patient Empowerment: Co-creation and Co-destruction of Value in the Healthcare Environment. Cham: Springer; 2017. pp. 63–78. 10.1007/978-3-319-58344-0_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KM, Leister S, De Rego R. The 5Ts for Teach Back: An Operational Definition for Teach-Back Training. Health Lit Res Pract. 2020. April;4(2):e94–103. 10.3928/24748307-20200318-01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayran O, Özer O. Organizational health literacy as a determinant of patient satisfaction. Public Health. 2018. October;163(1):20–6. 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet JJ, Schünemann HJ, Togias A, Erhola M, Hellings PW, Zuberbier T, et al. ARIA Study Group. MASK Study Group. Next-generation ARIA care pathways for rhinitis and asthma: a model for multimorbid chronic diseases. Clin Transl Allergy. 2019. September;9(44):44. 10.1186/s13601-019-0279-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrard G, Ketterer F, Giet D, Vanmeerbeek M, Belche JL, Buret L. [Health literacy, a lever to make health care systems more equitable? Tools to support professionals and involve institutions]. Sante Publique. 2018. May-Jun;30(1 Suppl):139–43. 10.3917/spub.184.0139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathmann K, Vockert T, Wetzel LD, Lutz J, Dadaczynski K. Organizational Health Literacy in Facilities for People with Disabilities: First Results of an Explorative Qualitative and Quantitative Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. April;17(8):2886. 10.3390/ijerph17082886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver NL, Wray RJ, Zellin S, Gautam K, Jupka K. Advancing organizational health literacy in health care organizations serving high-needs populations: a case study. J Health Commun. 2012;17(3 Suppl 3):55–66. 10.1080/10810730.2012.714442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmanova E, Bonneville L, Bouchard L. Organizational Health Literacy: Review of Theories, Frameworks, Guides, and Implementation Issues. Inquiry. 2018. Jan-Dec;55(1):46958018757848. 10.1177/0046958018757848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaby A, Palner S, Maindal HT. Fit for Diversity: A Staff-Driven Organizational Development Process Based on the Organizational Health Literacy Responsiveness Framework. Health Lit Res Pract. 2020. March;4(1):e79–83. 10.3928/24748307-20200129-01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaby A, Simonsen CB, Ryom K, Maindal HT. Improving Organizational Health Literacy Responsiveness in Cardiac Rehabilitation Using a Co-Design Methodology: Results from The Heart Skills Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. February;17(3):1015. 10.3390/ijerph17031015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmanova E, Bouchard L, Bonneville L. Success Strategies for Linguistically Competent Healthcare: The Magic Bullets and Cautionary Tales of the Active Offer of French-Language Health Services in Ontario. Healthc Q. 2018. January;20(4):24–30. 10.12927/hcq.2018.25427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezona A, Dodson S, Osborne RH. Development of the Organisational Health Literacy Responsiveness (Org-HLR) self-assessment tool and process. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018. September;18(1):694. 10.1186/s12913-018-3499-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaper M, Sixsmith J, Meijering L, Vervoordeldonk J, Doyle P, Barry MM, et al. Implementation and Long-Term Outcomes of Organisational Health Literacy Interventions in Ireland and The Netherlands: A Longitudinal Mixed-Methods Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019. November;16(23):4812. 10.3390/ijerph16234812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vamos CA, Thompson EL, Griner SB, Liggett LG, Daley EM. Applying Organizational Health Literacy to Maternal and Child Health. Matern Child Health J. 2019. May;23(5):597–602. 10.1007/s10995-018-2687-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen AK, Thygesen LC, Mortensen OS, Punnett L, Jørgensen MB. The effect of strengthening health literacy in nursing homes on employee pain and consequences of pain ‒ a stepped-wedge intervention trial. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2019. July;45(4):386–95. 10.5271/sjweh.3801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe K, Kennedy M, Bensberg M. How healthy are our emergency departments? Emerg Med (Fremantle). 2002. June;14(2):153–9. 10.1046/j.1442-2026.2002.00310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong TW, Yau JK, Chan CL, Kwong RS, Ho SM, Lau CC, et al. The psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on healthcare workers in emergency departments and how they cope. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005. February;12(1):13–8. 10.1097/00063110-200502000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzano L, Adler JR. Supporting staff working with prisoners who self-harm: A survey of support services for staff dealing with self-harm in prisons in England and Wales. Int J Prison Health. 2007;3(4):268–82. 10.1080/17449200701682501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Annarumma C, Palumbo R. Contextualizing Health Literacy to Health Care Organizations: exploratory Insights. J Health Manag. 2016;18(4):611–24. 10.1177/0972063416666348 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wray R, Weaver N, Adsul P, Gautam K, Jupka K, Zellin S, et al. Enhancing organizational health literacy in a rural Missouri clinic: a qualitative case study. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2019. June;32(5):788–804. 10.1108/IJHCQA-05-2018-0131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastroianni F, Chen YC, Vellar L, Cvejic E, Smith JK, McCaffery KJ, et al. Implementation of an organisation-wide health literacy approach to improve the understandability and actionability of patient information and education materials: A pre-post effectiveness study. Patient Educ Couns. 2019. September;102(9):1656–61. 10.1016/j.pec.2019.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo R, Annarumma C. Empowering organizations to empower patients: an organizational health literacy approach. Int J Healthc Manag. 2018;11(2):133–42. 10.1080/20479700.2016.1253254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laing R, Thompson SC, Elmer S, Rasiah RL. Fostering health literacy responsiveness in a remote primary health care setting: A pilot study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. April;17(8):2730. 10.3390/ijerph17082730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietscher C, Nowak P, Pelikan J. Health Literacy in Austria: interventions and Research. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2020. June;269:192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay S, Meggetto E, Robinson A, Davis C. Health literacy education for rural health professionals: shifting perspectives. Aust Health Rev. 2019. August;43(4):404–7. 10.1071/AH18019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelikan JM, Dietscher C. [Why should and how can hospitals improve their organizational health literacy?]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015. September;58(9):989–95. 10.1007/s00103-015-2206-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietscher C, Pelikan J. M. PJ. Health-literate healthcare organizations: feasibility study of organizational self-assessment with the Vienna tool in Austrian hospitals. Präv Gesundheitsf. 2016;11(1):53–61. 10.1007/s11553-015-0523-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oelschlegel S, Grabeel KL, Tester E, Heidel RE, Russomanno J. Librarians Promoting Changes in the Health Care Delivery System through Systematic Assessment. Med Ref Serv Q. 2018. Apr-Jun;37(2):142–52. 10.1080/02763869.2018.1439216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince LY, Schmidtke C, Beck JK, Hadden KB. An Assessment of Organizational Health Literacy Practices at an Academic Health Center. Qual Manag Health Care. 2018. Apr-Jun;27(2):93–7. 10.1097/QMH.0000000000000162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernstmann N, Halbach S, Kowalski C, Pfaff H, Ansmann L. Measuring attributes of health literate health care organizations from the patients’ perspective: Development and validation of a questionnaire to assess health literacy-sensitive communication (HL-COM). Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundh wesen. 2018;121:58-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezona A, Dodson S, Fitzsimon E, LaMontagne AD, Osborne RH. Field-Testing and Refinement of the Organisational Health Literacy Responsiveness Self-Assessment (Org-HLR) Tool and Process. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. February;17(3):1000. 10.3390/ijerph17031000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelikan JM. From the Health Literacy Survey Europe (HLS-EU) to Measuring Population and Organizational Health Literacy (M-POHL). Eur J Public Health. 2018;28(4 suppl_4):265. 10.1093/eurpub/cky212.776 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dietscher C, Pelikan J. The action network for measuring population and organizational health literacy (M-POHL) and its Health Literacy Survey 2019 (HLS19). Eur J Public Health. 2019;29(4 Supplement_4):203–4. 10.1093/eurpub/ckz185.556 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loos AT. Health Literacy Missouri: Evaluating a Social Media Program at a Health Literacy Organization. J Cons Health Int. 2013;17(4):389–96. 10.1080/15398285.2013.836940 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pelikan JM. NP. Validating a model & self-assessment tool to measure organizational health literacy in hospitals. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29(4):298–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaccorsi G, Romiti A, Ierardi F, Innocenti M, Del Riccio M, Frandi S, et al. Health-literate healthcare organizations and quality of care in hospitals: A cross-sectional study conducted in Tuscany. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. April;17(7):2508. 10.3390/ijerph17072508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell NA. Shaping humane healthcare systems. Nurs Adm Q. 2007. Jul-Sep;31(3):195–201. 10.1097/01.NAQ.0000278932.26621.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searl MM, Borgi L, Chemali Z. It is time to talk about people: a human-centered healthcare system. Health Res Policy Syst. 2010. November;8(35):35. 10.1186/1478-4505-8-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung AW. Comparison between Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed and publishers for mislabelled review papers. Curr Sci. 2019;116(11):1909–14. 10.18520/cs/v116/i11/1909-1914 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thune T, Mina A. Hospitals as innovators in the health-care system: A literature review and research agenda. Res Policy. 2016;45(8):1545–57. 10.1016/j.respol.2016.03.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greaney ML, Wallington SF, Rampa S, Vigliotti VS, Cummings CA. Assessing health professionals’ perception of health literacy in Rhode Island community health centers: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2020. August;20(1):1289. 10.1186/s12889-020-09382-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saboga-Nunes LA, Bittlingmayer WH, Okan O, Sahrai D. Assessing health professionals’ perception of health literacy in Rhode Island community health centers: a qualitative study. Cham: Springer; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charoghchian Khorasani E, Tavakoly Sany SB, Tehrani H, Doosti H, Peyman N. Review of Organizational Health Literacy Practice at Health Care Centers: Outcomes, Barriers and Facilitators. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. October;17(20):7544. 10.3390/ijerph17207544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynia MK, Osborn CY. Health literacy and communication quality in health care organizations. J Health Commun. 2010;15(2 Suppl 2):102–15. 10.1080/10810730.2010.499981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo R, Annarumma C, Manna R, Musella M, Adinolfi P. Improving quality by involving patient. The role of health literacy in influencing patients’ behaviors. Int J Healthc Manag. Published on-line ahead of print. Doi: 10.1080/20479700.2019.1620458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Gani SM, Nowak-Flück D, Nicca D, Vogt D. Self-Assessment Tool to Promote Organizational Health Literacy in Primary Care Settings in Switzerland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. December;17(24):9497. 10.3390/ijerph17249497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]