Abstract

West Nile virus (WNV), belonging to the Flaviviridae family, causes a mosquito-borne disease and shows great genetic diversity, with at least eight different lineages. The Koutango lineage of WNV (WN-KOUTV), mostly associated with ticks and rodents in the wild, is exclusively present in Africa and shows evidence of infection in humans and high virulence in mice. In 2016, in a context of Rift Valley fever (RVF) outbreak in Niger, mosquitoes, biting midges and sandflies were collected for arbovirus isolation using cell culture, immunofluorescence and RT-PCR assays. Whole genome sequencing and in vivo replication studies using mice were later conducted on positive samples. The WN-KOUTV strain was detected in a sandfly pool. The sequence analyses and replication studies confirmed that this strain belonged to the WN-KOUTV lineage and caused 100% mortality of mice. Further studies should be done to assess what genetic traits of WN-KOUTV influence this very high virulence in mice. In addition, given the risk of WN-KOUTV to infect humans, the possibility of multiple vectors as well as birds as reservoirs of WNV, to spread the virus beyond Africa, and the increasing threats of flavivirus infections in the world, it is important to understand the potential of WN-KOUTV to emerge.

Keywords: West Nile virus, Koutango lineage, high virulence, sandflies, Niger

1. Introduction

West Nile virus (WNV) is flavivirus maintained in nature through an enzootic transmission cycle between Culex spp. mosquitoes including Cx. pipiens, Cx. quinquefasciatus, Cx. neavei and birds [1,2,3]. WN fever outbreaks occur essentially in humans and horses, considered as dead-end hosts [4]. Clinical symptoms range from asymptomatic or flu-like illness to severe neurological and meningoencephalitis syndromes [3]. WNV is one of the most widespread flaviviruses worldwide, has caused massive human and animal infections, and some fatal cases, particularly in America and Europe [5,6,7,8]. WNV has a great genetic diversity with at least eight different lineages, and of them four (lineages 1, 2, Koutango and putative new lineage 8) are present in Africa [9]. The WN lineage 1 is distributed worldwide and has been responsible for all major WN outbreaks [6,8,10,11]. The WN lineage 2 was exclusively present in Africa until 2004, when it emerged in Europe and replaced lineage 1 [12]. Migratory birds that overwintered in Africa were the most likely source of introduction of WN lineage 2 into Europe. The putative new lineage was isolated from Cx. perfuscus in the south-east of Senegal in 1992 and was never found associated with animals or humans [9]. The Koutango lineage of West Nile virus (WN-KOUTV) was first isolated in 1968 from the wild rodent Tatera kempi in Senegal [13] and in 1974 from gerbils in Somalia [14]. WN-KOUTV was initially classified as a distinct virus and later, based on phylogenetic studies, considered a WNV lineage [15,16]. WN-KOUTV is exclusively detected in Africa, and unlike other WNV lineages, it was once isolated from mosquitoes and mainly from ticks and rodents, particularly in Senegal [17]. In humans, serological evidence in Gabon [18] and a report of an accident where a Senegalese laboratory worker was symptomatically infected with WN-KOUTV [19] have been shown. Different symptoms such as two-day fever accompanied by achiness and retrobulbar headache, to erythematous eruption on the flanks, were detected [13,19]. Patients with acute febrile illness ruled out for malaria and Lassa fever in Sierra Leone were found to present neutralizing antibodies to WN-KOUTV [20]. This unpublished study shows that natural human infections with WN-KOUTV are occurring in Africa and suggests that this virus is likely the etiological agent of at least some of the fevers with unknown origin.

In animal models, intra-cerebral inoculation of the virus to new-borne mice causes death on days three to four post-infection [13], and in adult mice, WN-KOUTV showed higher virulence compared to all other WNV lineages [17,21,22]. Currently, the transmission cycle remains unclear, and the roles of ticks and mosquitoes are not yet known. Indeed, vector competence studies showed that Cx. quinquefasciatus and Cx. neavei, proven vectors for other WNV lineages, were not competent for WN-KOUTV lineage [9]. Another vector competence study showed that Aedes aegypti was found to carry the virus and disseminated the infection after a blood meal with high viral dose [23], suggesting that this mosquito species could probably transmit WN-KOUTV lineage to humans. It has also been shown that Ae. aegypti was able to vertically transmit the virus [24]. Vector competence of ticks, mostly associated with the virus in the wild, has never been tested.

In the context of Rift Valley fever (RVF) outbreak investigations in Niger, in 2016 [25], mosquitoes and sandflies were collected for arbovirus detection. The laboratory analyses revealed the presence of the WN-KOUTV lineage in a pool of sandflies. Here, we describe this first detection of WN-KOUTV in sandflies, the virus isolation, viral genome sequencing and analyses, and in vivo characterization in mice.

2. Results

2.1. Arthropod Species

A total of 10,977 hematophagous arthropods (158 mosquitoes, 10,816 sandflies and 3 biting midges) were collected and grouped into 181 pools (Table 1). Of these, sandflies were the only arthropod group collected in Intoussane, and the most abundant in Tchintabaraden (n = 359; 83.3%) and Tasnala (n = 10,428; 99.2%). Anopheles gambiae (58.2%) and Cx perexiguus (24.7%) were the most abundant among six mosquito species collected during our collection period. Sandflies were collected only by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) light traps near herds at Intoussane, and ground pools at Tasnala, while they were found in all biotopes investigated at Tchintabaraden.

Table 1.

List of arthropods collected in the field from three districts of Niger, 20–24 October 2016.

| Species | Tchintabaraden | Intoussane | Tasnala | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anopheles gambiae | 40 | 52 | 92 | |

| Anopheles rufipes | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| Cx. antennatus | 1 | 1 | ||

| Cx. ethiopicus | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| Cx. quinquefasciatus | 14 | 4 | 18 | |

| Cx. perexiguus | 14 | 25 | 39 | |

| Total mosquitoes | 71 | 87 | 158 | |

| Biting midges | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Sandflies | 359 | 29 | 10,428 | 10,816 |

| Total arthropods | 431 | 29 | 10,517 | 10,977 |

2.2. Virus Detection

One pool of 100 sandflies collected by CDC light trap near a ground pool at Tasnala was positive for flavivirus by immunofluorescence assay IFA and West Nile virus by real time RT-PCR. The genotyping using WNV primers and probes specific to the different lineages, as well as the genome sequencing, showed the presence of WN-KOUTV in the sample.

The minimum infection rate (MIR) was 0.01 per 1000 in the ground pool where the positive pool was collected.

2.3. Sequencing and Evolutionary Analyses

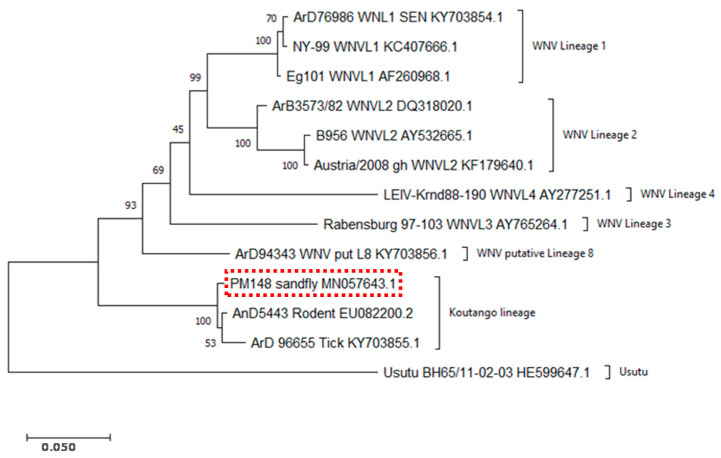

A genome sequence of 10,948 bp was obtained. The BLAST search showed that the sequence corresponds to WN-KOUTV and the Genbank accession number is MN057643. Phylogenetic analyses showed that the sequence of the strain isolated from sandflies belongs to the same cluster as other WN-KOUTV strains, ArD96655 (accession number KY703855.1) and Dak Ar D 5443 (accession number EU082200.2). This analysis confirmed, therefore, that the virus strain from sandflies in Niger belongs to the WN-KOUTV lineage (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analyses using MEGA software and the maximum likelihood method. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted with sequences of the sandfly strain, other Koutango strains isolated in Senegal from ticks and rodents, and other WNV lineage strains. The accession numbers and names of the strains are mentioned. The accession number of the sandfly strain genomic sequence, PM148 from Niger, is MN057643. WNVL1: lineage 1, WNVL2: lineage 2, WNVL3: lineage 3, WNVL4: lineage 4 and WNV Put L8: putative lineage 8.

Amino acid sequence analyses of the sandfly strain and other WNV strains showed a mean genetic distance around 0.01 within the Koutango lineage (Table 2). The sandfly strain was more closed to the rodent WN-KOUTV strain, with a genetic distance of 0.005. As with other WN-KOUTV strains, the sandfly strain also showed high genetic distances with other WNV lineages, ranging from 11 to 18% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genetic distance analysis conducted using MEGA software with the Poisson correction model.

| Strains | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.PM148_sandfly_MN057643.1_Koutango_lineage | ||||||||||||

| 2.AnD5443_Rodent_EU082200.2_Koutango_lineage | 0.00584 | |||||||||||

| 3.ArD_96655_Tick_KY703855.1_Koutango_lineage | 0.02121 | 0.00848 | ||||||||||

| 4.ArD76986_SEN_KY703854.1_WNV_Lineage_1 | 0.11371 | 0.11469 | 0.11764 | |||||||||

| 5.Eg101_AF260968.1_WNV_Lineage_1 | 0.13990 | 0.11208 | 0.14274 | 0.00584 | ||||||||

| 6.NY-99_KC407666.1_WNV_Lineage_1 | 0.14174 | 0.11404 | 0.14398 | 0.00467 | 0.00769 | |||||||

| 7.ArB3573/82_DQ318020.1_WNV_Lineage_2 | 0.13645 | 0.11371 | 0.14039 | 0.06095 | 0.07205 | 0.07557 | ||||||

| 8.Austria/2008_gh_KF179640.1_WNV_Lineage_2 | 0.13084 | 0.11310 | 0.12682 | 0.06004 | 0.08429 | 0.08696 | 0.03494 | |||||

| 9.B956_AY532665.1_WNV_Lineage_2 | 0.13294 | 0.11353 | 0.12892 | 0.06196 | 0.08603 | 0.08930 | 0.03663 | 0.00634 | ||||

| 10.ArD94343_KY703856.1_WNV_putative_Lineage_8 | 0.12553 | 0.12752 | 0.12917 | 0.09528 | 0.09432 | 0.09368 | 0.09176 | 0.09147 | 0.09156 | |||

| 11.LEIV-Krnd88-190_AY277251.1_WNV_Lineage_4 | 0.18058 | 0.15722 | 0.18384 | 0.12070 | 0.13969 | 0.14094 | 0.13333 | 0.13487 | 0.13640 | 0.14568 | ||

| 12.Rabensburg_97-103_AY765264.1_WNV_Lineage_3 | 0.16703 | 0.14386 | 0.17689 | 0.10107 | 0.12331 | 0.12359 | 0.11968 | 0.12823 | 0.13222 | 0.12224 | 0.16220 |

In grey, genetic distances within WN-KOUTV lineage. Red rectangle, genetic distances between sandfly strain and with other WNV lineages.

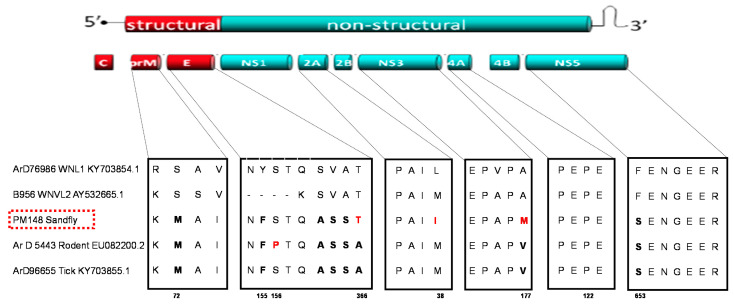

Amino acid sequence alignment of the new sandfly strain and other WNV strains was performed to check for mutations that have been shown to impact WNV virulence (Figure 2). Mutations already described for WN-KOUTV strains [26,27,28] have been detected in the pre-membrane (S to M at position 72), envelope (Y to F at position 155 of the glycosylation site), and NS5 (F to S at position 653) proteins of the new sandfly WN-KOUTV strain. In addition, the rodent WN-KOUTV strain showed a specific mutation (S to P) at position 156 of the envelope protein glycosylation site. Mutations with unknown consequence (SVA to ASS), specific to all WN-KOUTV strains analyzed here, were also detected at positions 363 to 365 of the envelope protein. The new sandfly WN-KOUTV strain shared a mutation (A to T) with WNVL1 and L2 at position 366 of the envelope protein and showed specific/unique mutations compared to other WN-KOUTV strains at position 38 (M to I) of the NS2A and 177 (V to M) of the NS3 proteins (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Genetic diversity of WNV lineages 1, 2 and Koutango. Alignment was conducted with sequences of the sandfly strain, other Koutango strains isolated in Senegal from ticks and rodents, and other WNV lineages 1 and 2 strains. The genomic structure of West Nile virus is shown, and the different genes are labeled. Alignments of motifs with unknown consequence and known virulence motifs are shown. Mutations specific to all Koutango strains are in bold and mutations specific to one Koutango strain are in red.

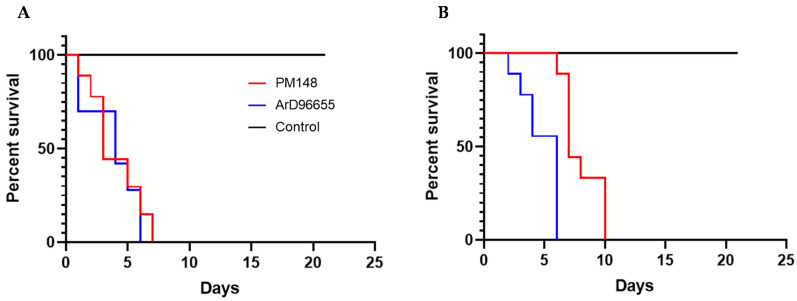

2.4. In Vivo Characterization

Intra-cerebral inoculation of the new KOUTV strain isolated from sandflies to new-borne mice showed 100% mortality at day two post-infection, while ArD96655 showed 100% mortality at day four post-infection. In adult mice, the Koutango sandfly strain showed 100% mortality of mice at days 7 and 10 post-infection with 100 and 1000 pfu, respectively, while ArD96655 showed 100% mortality at day six post-infection with both doses (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Survival curves of 5- to 6-week-old mice following intraperitoneal infection with (A) 100, and (B) 1000 pfu. Eight mice were tested for each dose. A group of mice with an injection of PBS was used as control. Mice were monitored daily for 21 days.

In both experiments, PBS-inoculated negative control groups showed no signs of disease and stayed alive throughout the experiments.

3. Discussion

Our study showed, for the first time to the best of our knowledge, the isolation of WN-KOUTV from sandflies but also the detection of this particular West Nile virus lineage in Niger. Indeed, phylogenetic analyses showed that the virus strain from sandflies exhibited similar genotypic patterns to other WN-KOUTV strains already described [9,17]. WN-KOUTV was previously isolated once from mosquitoes and several times from ticks in Senegal, then this isolation in sandflies extended the spectrum of the potential WN-KOUTV vectors and highlighted once again the particular feature of this WNV lineage. The vector competence of ticks and sandflies, naturally associated with the WN-KOUTV lineage, is not proven, but in laboratory conditions it has been shown that Ae. aegypti can transmit the WN-KOUTV lineage, but only with a high viral dose in an artificial blood meal. This suggests that only high viremia will naturally render a vertebrate host infectious for the Ae. aegypti mosquito [24]. However, little is known about WN-KOUTV infections and viremia titers in vertebrate hosts. In addition, apart from rodents, the existence of other vertebrate hosts in the wild is not known. Obviously, because WN-KOUTV is a WNV lineage, birds might also play important roles in its transmission as well as propagation beyond the African continent, as proposed for lineages 1 and 2 [2,6]. All these considerations emphasize the need to better characterize this particular WNV lineage in Africa and its epidemic potential. Therefore, more studies are needed to help understand the potential of the common mosquito species Ae. aegypti to transmit naturally WN-KOUTV between different vertebrate hosts, and the role of birds in the transmission cycle. Vector competence studies of ticks and sandflies species are also necessary to better understand the transmission dynamics of WN-KOUTV.

Sequence analyses conducted in this study showed high genetic distances between WN-KOUTV and other WNV lineages, which confirmed that Koutango is the most distant WNV lineage [17]. The sequence alignment showed variations specific to KOUTV lineage and also between KOUTV strains. The mutations found in the envelope, pre-membrane and NS5, in all WN-KOUTV strains, could therefore explain the higher virulence of this lineage compared to other WNV lineages. In addition, although high virulence was observed for both WN-KOUTV strains in mice, differences in the survival times of newborn and adult mice were noted. Further studies with more WN-KOUTV strains are therefore needed, to better characterize the genetic variations inside the WN-KOUTV lineage and their impact on the infection in vertebrate hosts. These studies will also help to understand if, like WNV lineages 1 and 2, strains with high and low virulence exist in the WN-KOUTV lineage.

No WN-KOUTV strain was detected in the different Culex spp. mosquitoes collected in this study. This could be partly explained by the low number of Culex spp. specimens collected. However, a previous vector competence study targeting two Culex species, considered as the most probable WNV vectors in domestic and enzootic contexts in Senegal, also showed that they were not competent for WN-KOUTV [9]. More vector competence studies targeting different vector species and WN-KOUTV strains are needed to better characterize the role of Culex mosquitoes in the transmission of WN-KOUTV.

In our study, the sandfly species positive for WN-KOUTV is not known because the sandflies collected during this investigation were not identified at species level. However, seven species including Phlebotomus roubaudi, Phlebotomus clydei and Phlebotomus orientalis were previously collected in Niger [29,30,31] and could be targeted for vector competence studies. The very high abundance of sandflies observed around dry pools in our study is concordant with previous investigations in the Sahelian area of Senegal [32] and Mauritania [33]. The peak abundance of these sandflies was shown to occur in the Sahelian area at the beginning of the dry season, around two months after the rain pools dry up [32]. Because they are only abundant during the dry season, sandflies would probably play a role in WN-KOUTV transmission in this period, while mosquitoes and/or ticks would be the main arthropods involved during the rainy season. Many other viruses were previously detected in phlebotomine sandflies in Africa, including Chandipura virus, Saboya virus, Tete virus, and two unknown viruses in Senegal [32,34], Yellow fever virus in Uganda [35], Perinet virus in Madagascar [36], sandfly fever Sicilian and sandfly fever Naples viruses in Egypt [37], and Punique virus in Tunisia [38]. Interestingly, like WN-KOUTV, Saboya virus, another flavivirus was also detected in both sandflies and rodents in Senegal [32,39]. This emphasizes the need to better characterize and evaluate the potential roles of sandflies in arbovirus transmission cycles, because many studies are only focused on mosquitoes and ticks.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Collection and Processing of Arthropods

Field investigations were conducted between 20–24 October 2016, in the villages of Tchintabaraden, Intoussane and Tasnala located in the district of Tchintabaraden (15°53′53″ N; 5°48′11″ E), Tahoua Region, Niger. These villages were selected based on the presence of confirmed human RVF cases and high abortion rates in ungulates. Hematophagous arthropods (mosquitoes, sandflies and biting midges) were collected in and around households of suspected and confirmed human RVF cases, herds, and the edges of ground pools using a backpack aspirator [40], CDC light traps [41], and indoor residual spaying [42].

Arthropods collected were frozen, morphologically identified to the species level for mosquitoes using morphological keys [43,44], and family level for other arthropods, pooled by family, species, sex, and date. All arthropod pools were conserved at the laboratory in Niamey, and later aliquots were transported to Institut Pasteur de Dakar for virus testing and isolation. The minimum infection rate (MIR) was calculated to estimate the viral infection rate in arthropod populations by assuming that at least one individual of the pooled sample could be infected. The formula of MIR is as follows; MIR = number of positive pools/numbers of tested arthropods × 1000.

4.2. Virus Isolation

The arthropod pools were homogenized in 3 mL of L-15 medium (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 20% of fetal bovine serum and clarified by centrifugation at 1500× g, at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatants were then filtered using a 1 mL syringe (Artsana, Como, Italy) and sterilized with 0.20 μm filters (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany).

Viral isolation was conducted from the supernatants using C6-36 (Ae. albopictus) cells, and the presence of virus was detected by immunofluorescence assay (IFA) using in-house immune ascite pools specific to different flaviviruses, bunyaviruses, orbiviruses, and alphaviruses, as previously described [45].

4.3. RT-PCR and Titration

RNA extraction was conducted from the supernatant of the IFA-positive sample using the QiaAmp Viral RNA Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Heiden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA samples were then screened by RT-PCR (reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction) for flaviviruses (dengue, yellow fever, Zika and West Nile virus). The primers and probes already described elsewhere were used [46,47,48,49].

The supernatant of the IFA-positive sample (confirmed by RT-PCR) was titrated as previously described, using PS cells (Porcine Stable kidney cells, ATCC number, Manassas, VA, USA) [50].

4.4. Viral Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analyses

Host ribosomal RNAs were depleted prior to sequencing from extracted RNA, using specific probes from partners at the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID). The sequence-independent, single-primer amplification (SISPA) method was used for cDNA synthesis from depleted RNAs, and libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT library prep kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with dual index strategy, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were normalized and pooled with PhiX DNA as loading control, and the sequencing was performed using Miseq, Illumina, for 2 × 151 cycles. Sequencing runs were monitored in real time using the Illumina Sequencing Viewer Analyzer for cluster density, percentage of clusters passing filter, phasing/pre-phasing ratios, % base, error rates, % reads with quality score ≥30, and other parameters. The bioinformatics analyses were performed via an in-house script that implements a pipeline for pathogen discovery. De novo assembly was performed using Geneious prime v. 2019.1.3 to obtain the complete sequence. A BLAST search was then conducted to identify the assembled sequence.

Alignment and evolutionary analyses (genetic distance and phylogenetic analyses) were conducted with amino acid sequences using MEGA-X 10.2.2 software (MEGA, University of Pennsylvania, USA). Genetic distance analysis was conducted using the Poisson correction model and the phylogenetic analysis was inferred by using the maximum likelihood method and JTT (Jones, Taylor, and Thornton) matrix-based model with a bootstrap test of 1000 replicates [51,52]. The tree with the highest log likelihood is shown in Figure 1.

4.5. In Vivo Characterization in Mice

The IFA-positive sample was tested in newborn and adult mice in comparison with the KOUTV strain ArD96655 (accession number KY703855.1) isolated from ticks.

Ten new-borne Swiss mice (1–2 days old) were inoculated with 1000 pfu of IFA positive sample, ArD96655 and PBS alone, by an intra-cerebral route and were monitored daily for 21 days.

Five- to six-week-old Swiss mice were also challenged by intraperitoneal route with 100 pfu and 1000 pfu, to analyze the virulence of the IFA-positive sample. The WN-KOUTV strain ArD96655 and PBS were also tested as positive and negative controls, respectively. Eight mice were tested for each dose. Survival curves were generated using GraphPad Prism 9.0.0 (121) software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

5. Conclusions

In this study, we have shown the circulation of WN-KOUTV in Niger and its detection in sandflies for the first time. These results extended the number of countries in Africa where this virus is reported, but also the spectrum of potential vectors. The very high virulence in mice [17,21,22], the possibility of multiple vectors, the risk of KOUTV to infect humans, and the increasing threats of flavivirus infections in the world, should contribute to better consideration of WNV-KOUTV as an important emerging pathogen. In this regard, vector competence studies, vertebrate hosts including birds, and viral genetic diversity characterizations are ongoing and will provide new insights on WN-KOUTV transmission, virulence and possibility to diffuse beyond Africa. Seroprevalence studies would also be important in Niger, particularly in Tahoua Region where the virus was isolated, and in Senegal where WN-KOUTV was isolated several times, to assess the potential circulation of KOUTV in humans.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the authorities of the Ministry of Health of Niger and WHO Country office of Niger and Afro region for facilitating the Rift Valley fever outbreak investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.F., D.D., M.D. (Mawlouth Diallo), O.F. (Ousmane Faye), and A.A.S.; methodology, E.H.N., D.D., H.S., G.F, B.D.S., and M.W.; formal analysis, M.W., M.D. (Mamadou Diop), M.H.D.N., and G.F.; validation, D.D., G.F., A.L., M.D. (Moussa Dia), M.H.D.N., C.L., and M.W.; investigation, E.H.N., D.D., H.S., A.L., G.F., M.H.D.N., M.D. (Moussa Dia), A.B., and B.D.S.; resources, A.L., F.S., J.T., B.B.N.; M.W., O.F. (Ousmane Faye), M.D. (Mawlouth Diallo), and A.A.S., writing—original draft preparation, G.F., writing—review and editing, H.S., A.L., D.D., G.F., M.D. (Mawlouth Diallo), O.F. (Ousmane Faye), O.F. (Oumar Faye), M.W., B.B.N., J.T., C.L., and F.S; supervision, F.S., G.F., D.D., B.D.S., and A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The field investigations in Niger were funded by WHO AFRO and the laboratory work was funded by Institut Pasteur de Dakar. This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

There is no National Ethics Committee for animals in Senegal. These studies were performed in the context of surveillance at the WHO collaborating center for arboviruses and hemorrhagic fever viruses, and all experiments on animals were conducted by respecting the World Organization for Animal Health regulations (https://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/fr/Health_standards/tahc/current/chapitre_aw_research_education.pdf) (accessed on 10 January 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the manuscript. The virus sequence generated during the current study is available at Genbank (accession number: MN057643).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hubálek Z., Halouzka J. West Nile Fever—A Reemerging Mosquito-Borne Viral Disease in Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 1999;5:643–650. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rappole J.H., Hubálek Z. Migratory Birds and West Nile Virus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003;94:47S–58S. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.94.s1.6.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayes E.B., Komar N., Nasci R.S., Montgomery S.P., O’Leary D.R., Campbell G.L. Epidemiology and Transmission Dynamics of West Nile Virus Disease. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005;11:1167–1173. doi: 10.3201/eid1108.050289a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kulasekera V.L., Kramer L., Nasci R.S., Mostashari F., Cherry B., Trock S.C., Glaser C., Miller J.R. West Nile Virus Infection in Mosquitoes, Birds, Horses, and Humans, Staten Island, New York, 2000. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2001;7:722–725. doi: 10.3201/eid0704.017421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeGroote J.P., Sugumaran R., Ecker M. Landscape, Demographic and Climatic Associations with Human West Nile Virus Occurrence Regionally in 2012 in the United States of America. Geospat. Health. 2014;9:153–168. doi: 10.4081/gh.2014.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernández-Triana L.M., Jeffries C.L., Mansfield K.L., Carnell G., Fooks A.R., Johnson N. Emergence of West Nile Virus Lineage 2 in Europe: A Review on the Introduction and Spread of a Mosquito-Borne Disease. Front. Public Health. 2014;2:271. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vilibic-Cavlek T., Kaic B., Barbic L., Pem-Novosel I., Slavic-Vrzic V., Lesnikar V., Kurecic-Filipovic S., Babic-Erceg A., Listes E., Stevanovic V., et al. First Evidence of Simultaneous Occurrence of West Nile Virus and Usutu Virus Neuroinvasive Disease in Humans in Croatia during the 2013 Outbreak. Infection. 2014;42:689–695. doi: 10.1007/s15010-014-0625-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox S.L., Campbell G.D., Nemeth N.M. Outbreaks of West Nile Virus in Captive Waterfowl in Ontario, Canada. Avian Pathol. J. WVPA. 2015;44:135–141. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2015.1011604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fall G., Diallo M., Loucoubar C., Faye O., Sall A.A. Vector Competence of Culex Neavei and Culex Quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) from Senegal for Lineages 1, 2, Koutango and a Putative New Lineage of West Nile Virus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014;90:747–754. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray K.O., Mertens E., Despres P. West Nile Virus and Its Emergence in the United States of America. Vet. Res. 2010;41:67. doi: 10.1051/vetres/2010039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anukumar B., Sapkal G.N., Tandale B.V., Balasubramanian R., Gangale D. West Nile Encephalitis Outbreak in Kerala, India, 2011. J. Clin. Virol. 2014;61:152–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakonyi T., Ivanics E., Erdélyi K., Ursu K., Ferenczi E., Weissenböck H., Nowotny N. Lineage 1 and 2 Strains of Encephalitic West Nile Virus, Central Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006;12:618–623. doi: 10.3201/eid1204.051379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coz J., Le Gonidec G., Cornet M., Valade M., Lemoine M., Gueye A. Transmission Experimentale d’un Arbovirus Du Groupe B, Le Virus Koutango Par Aedes aegypti L. Cah. ORSTOM Ser. Ent. Med. Parasitol. 1975;13:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butenko A.M., Semashko I.V., Skvortsova T.M., Gromashevskiĭ V.L., Kondrashina N.G. Detection of the Koutango virus (Flavivirus, Togaviridae) in Somalia. [(accessed on 22 February 2021)];Med. Parazitol. (Mosk.) 1986 :65–68. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3018465/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charrel R.N., Brault A.C., Gallian P., Lemasson J.-J., Murgue B., Murri S., Pastorino B., Zeller H., de Chesse R., de Micco P., et al. Evolutionary Relationship between Old World West Nile Virus Strains. Evidence for Viral Gene Flow between Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. Virology. 2003;315:381–388. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6822(03)00536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall R.A., Scherret J.H., Mackenzie J.S. Kunjin Virus: An Australian Variant of West Nile? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001;951:153–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb02693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fall G., Di Paola N., Faye M., Dia M., de Melo Freire C.C., Loucoubar C., de Andrade Zanotto P.M., Faye O. Biological and Phylogenetic Characteristics of West African Lineages of West Nile Virus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017;11:e0006078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jan C., Languillat G., Renaudet J., Robin Y. A serological survey of arboviruses in Gabon. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. Fil. 1978;71:140–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shope R.E. Epidemiology of Other Arthropod-Borne Flaviviruses Infecting Humans. Adv. Virus Res. 2003;61:373–391. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(03)61009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Araujo Lobo J. Ph.D. Thesis. Louisiana State University; Baton Rouge, LA, USA: 2012. Koutango: Under Reported Arboviral Disease in West Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pérez-Ramírez E., Llorente F., Del Amo J., Fall G., Sall A.A., Lubisi A., Lecollinet S., Vázquez A., Jiménez-Clavero M.Á. Pathogenicity Evaluation of Twelve West Nile Virus Strains Belonging to Four Lineages from Five Continents in a Mouse Model: Discrimination between Three Pathogenicity Categories. J. Gen. Virol. 2017;98:662–670. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prow N.A., Setoh Y.X., Biron R.M., Sester D.P., Kim K.S., Hobson-Peters J., Hall R.A., Bielefeldt-Ohmann H. The West Nile Virus-like Flavivirus Koutango Is Highly Virulent in Mice Due to Delayed Viral Clearance and the Induction of a Poor Neutralizing Antibody Response. J. Virol. 2014;88:9947–9962. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01304-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Araújo Lobo J.M., Christofferson R.C., Mores C.N. Investigations of Koutango Virus Infectivity and Dissemination Dynamics in Aedes Aegypti Mosquitoes. Environ. Health Insights. 2014;8:9–13. doi: 10.4137/EHI.S16005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coz J., Valade M., Cornet M., Robin Y. Transovarian transmission of a Flavivirus, the Koutango virus, in Aedes aegypti L. C. R. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. Ser. Sci. Nat. 1976;283:109–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lagare A., Fall G., Ibrahim A., Ousmane S., Sadio B., Abdoulaye M., Alhassane A., Mahaman A.E., Issaka B., Sidikou F., et al. First Occurrence of Rift Valley Fever Outbreak in Niger, 2016. Vet. Med. Sci. 2019;5:70–78. doi: 10.1002/vms3.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beasley D.W.C., Whiteman M.C., Zhang S., Huang C.Y.-H., Schneider B.S., Smith D.R., Gromowski G.D., Higgs S., Kinney R.M., Barrett A.D.T. Envelope Protein Glycosylation Status Influences Mouse Neuroinvasion Phenotype of Genetic Lineage 1 West Nile Virus Strains. J. Virol. 2005;79:8339–8347. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8339-8347.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Setoh Y.X., Prow N.A., Hobson-Peters J., Lobigs M., Young P.R., Khromykh A.A., Hall R.A. Identification of Residues in West Nile Virus Pre-Membrane Protein That Influence Viral Particle Secretion and Virulence. J. Gen. Virol. 2012;93:1965–1975. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.044453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Slyke G.A., Ciota A.T., Willsey G.G., Jaeger J., Shi P.-Y., Kramer L.D. Point Mutations in the West Nile Virus (Flaviviridae; Flavivirus) RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Alter Viral Fitness in a Host-Dependent Manner in Vitro and in Vivo. Virology. 2012;427:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parrot L., Hornet J., Cadenat J. Note on the Phlebotomines. XLVIII. Phlebotomines of French West Africa. 1. Senegal, Soudan, Niger. Arch. Inst. Pasteur D’Algerie. 1945;23:232–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Pont F., Robert V., Vattier-Bernard G., Rispail P., Jarry D. Notes on the phlebotomus of Aïr (Niger) Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 1990. 1993;86:286–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abonnenc E., Dyemkouma A., Hamon J. On the presence of phlebotomus (phlebotomus) orientalis parrot, 1936, in the republic of niger. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. Fil. 1964;57:158–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fontenille D., Traore-Lamizana M., Trouillet J., Leclerc A., Mondo M., Ba Y., Digoutte J.P., Zeller H.G. First Isolations of Arboviruses from Phlebotomine Sand Flies in West Africa. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1994;50:570–574. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.50.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nabeth P., Kane Y., Abdalahi M.O., Diallo M., Ndiaye K., Ba K., Schneegans F., Sall A.A., Mathiot C. Rift Valley Fever Outbreak, Mauritania, 1998: Seroepidemiologic, Virologic, Entomologic, and Zoologic Investigations. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2001;7:1052–1054. doi: 10.3201/eid0706.010627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ba Y., Trouillet J., Thonnon J., Fontenille D. Phlebotomine Sandflies Fauna in the Kedougou Area of Senegal, Importance in Arbovirus Transmission. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 1999;92:131–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smithburn K.C., Haddow A.J., Lumsden W.H.R. An Outbreak of Sylvan Yellow Fever in Uganda with Aëdes (Stegomyia) Africanus Theobald as Principal Vector and Insect Host of the Virus. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1949;43:74–89. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1949.11685396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clerc Y., Rodhain F., Digoutte J.P., Tesh R., Heme G., Coulanges P. The Perinet virus, rhabdoviridae, of the vesiculovirus type isolated in Madagascar from Culicidae. Arch. Inst. Pasteur Madag. 1982;49:119–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmidt J.R., Schmidt M.L., Said M.I. Phlebotomus Fever in Egypt. Isolation of Phlebotomus Fever Viruses from Phlebotomus Papatasi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1971;20:483–490. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1971.20.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhioua E., Moureau G., Chelbi I., Ninove L., Bichaud L., Derbali M., Champs M., Cherni S., Salez N., Cook S., et al. Punique Virus, a Novel Phlebovirus, Related to Sandfly Fever Naples Virus, Isolated from Sandflies Collected in Tunisia. J. Gen. Virol. 2010;91:1275–1283. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.019240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saluzzo J.F., Adam F., Heme G., Digoutte J.P. Isolation of viruses from rodents in Senegal (1983–1985). Description of a new poxvirus. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. Fil. 1986;79:323–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clark G.G., Seda H., Gubler D.J. Use of the “CDC Backpack Aspirator” for Surveillance of Aedes Aegypti in San Juan, Puerto Rico. J. Am. Mosq. Control. Assoc. 1994;10:119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sudia W.D., Chamberlain R.W. Battery-Operated Light Trap, an Improved Model. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 1988;4:536–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Service M. Mosquito Ecology: Field Sampling Methods. Chapman Hall ed. Springer; London, UK: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edwards E. Mosquitoes of the Ethiopian Region: III Culicine Adults and Pupae. British Museum Natural History; London, UK: 1941. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diagne N., Fontenille D., Konate L., Faye O., Lamizana M.T., Legros F., Molez J.F., Trape J.F. Anopheles of Senegal. An annotated and illustrated list. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 1994;87:267–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Digoutte J.P., Calvo-Wilson M.A., Mondo M., Traore-Lamizana M., Adam F. Continuous Cell Lines and Immune Ascitic Fluid Pools in Arbovirus Detection. Res. Virol. 1992;143:417–422. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2516(06)80135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagner D., de With K., Huzly D., Hufert F., Weidmann M., Breisinger S., Eppinger S., Kern W.V., Bauer T.M. Nosocomial Acquisition of Dengue. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004;10:1872–1873. doi: 10.3201/eid1010.031037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weidmann M., Faye O., Faye O., Kranaster R., Marx A., Nunes M.R.T., Vasconcelos P.F.C., Hufert F.T., Sall A.A. Improved LNA Probe-Based Assay for the Detection of African and South American Yellow Fever Virus Strains. J. Clin. Virol. 2010;48:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Faye O., Faye O., Diallo D., Diallo M., Weidmann M., Sall A.A. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Detection of Zika Virus and Evaluation with Field-Caught Mosquitoes. Virol. J. 2013;10:311. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fall G., Faye M., Weidmann M., Kaiser M., Dupressoir A., Ndiaye E.H., Ba Y., Diallo M., Faye O., Sall A.A. Real-Time RT-PCR Assays for Detection and Genotyping of West Nile Virus Lineages Circulating in Africa. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2016;16:781–789. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2016.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Madrid A.T., Porterfield J.S. A Simple Micro-Culture Method for the Study of Group B Arboviruses. Bull. World Health Organ. 1969;40:113–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones D.T., Taylor W.R., Thornton J.M. The Rapid Generation of Mutation Data Matrices from Protein Sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci. CABIOS. 1992;8:275–282. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the manuscript. The virus sequence generated during the current study is available at Genbank (accession number: MN057643).