Abstract

Objective:

To compare long-term clinical and economic outcomes associated with 3 management strategies for reducible ventral hernia: repair at diagnosis (open or laparoscopic) and watchful waiting.

Background:

There is variability in ventral hernia management. Recent data suggest watchful waiting is safe; however, long-term clinical and economic outcomes for different management strategies remain unknown.

Methods:

We built a state-transition microsimulation model to forecast outcomes for individuals with reducible ventral hernia, simulating a cohort of 1 million individuals for each strategy. We derived cohort characteristics (mean age 58y, 63% female), hospital costs, and perioperative mortality from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (2003–2011) and additional probabilities, costs, and utilities from the literature. Outcomes included prevalence of any repair, emergent repair, and recurrence; lifetime costs; quality-adjusted life years (QALYs); and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs). We performed stochastic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses to identify parameter thresholds that affect optimal management, using a willingness-to-pay threshold of $50,000/QALY.

Results:

With watchful waiting, 39% ultimately required repair (14% emergent) and 24% recurred. Seventy percent recurred with repair at diagnosis. Laparoscopic repair at diagnosis was cost-effective compared to open repair at diagnosis (ICER=$27,700/QALY). The choice of operative strategy (open versus laparoscopic) was sensitive to cost and post-operative quality of life. When perioperative mortality exceeded 5.2% or yearly recurrence exceeded 19.2%, watchful waiting became preferred.

Conclusions:

Ventral hernia repair at diagnosis is very cost-effective. The choice between open and laparoscopic repair depends on surgical costs and post-operative quality of life. In patients with high risk of perioperative mortality or recurrence, watchful waiting is preferred.

Keywords: cost-effectiveness, ventral hernia repair, watchful waiting, timing of repair

MINI-ABSTRACT

We used a decision analytic approach to assess long-term clinical and economic outcomes associated with 3 different management strategies for reducible ventral hernia: open repair at diagnosis, laparoscopic repair at diagnosis, and watchful waiting.

INTRODUCTION

Ventral hernias remain a common problem addressed by general surgeons and subspecialists, with incidence of repairs increasing over time (1). Despite extensive research, there remains mixed expert opinion and variability in practice regarding the indication for and timing of ventral hernia repair (VHR) (2). One key decision is whether to operate at the time of diagnosis or pursue “watchful waiting,” an initial course of non-operative management. Long-term follow-up from a randomized controlled trial of watchful waiting for inguinal hernias revealed that while it is safe to observe patients with inguinal hernia, most will ultimately require surgical repair (3,4). Recently published observational data suggest that watchful waiting may also be safe in patients with ventral hernia (5–7). Multiple randomized controlled trials are underway to provide more definitive guidance (clinicaltrials.gov identifiers NCT02457364, NCT02263599, NCT01349400) (8,9).

While randomized controlled trials and observational studies provide important information on the short-term impact of clinical decisions, they are rarely able to assess the long-term impact of a given clinical decision. As an adjunct, decision analysis with a model-based approach allows researchers to compile the best available data from multiple sources to estimate long-term clinical and economic consequences of specific treatment strategies. One previous decision analysis on the timing of VHR found prompt elective VHR to be cost-effective (10); however, this study was limited by its design as a decision tree model. We sought to expand on the current literature by building a detailed simulation model representing ventral hernia disease, including risks of incarceration and recurrence, to model the lifetime cost and quality-adjusted life expectancy associated with different management strategies for reducible ventral hernia.

METHODS

Analytic overview

We built a state transition microsimulation model of the natural history and treatment of ventral hernias to simulate clinical and economic outcomes for patients with a diagnosed, reducible ventral hernia under three different management strategies: 1) open repair at diagnosis, 2) laparoscopic repair at diagnosis, and 3) watchful waiting, or deferring operative management until the development of symptoms or acute incarceration. Our primary outcomes included quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and lifetime medical costs for each strategy, as well as incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) to compare the strategies. QALYs are a measure of disease burden representing both quantity and quality of life lived; they are calculated by multiplying utilities, or quality-rating factors on a 0–1 scale, by survival (11). All costs are presented in 2015 U.S. dollars (12).

We also projected several clinical endpoints, including prevalence of any VHR, emergent repair, and recurrence after initial repair. We adopted the societal perspective for our main analysis and also performed the analysis from the healthcare payer perspective, as recommended (11,13). We discounted future costs and benefits at 3% yearly. To compare the strategies to other healthcare interventions, we used a willingness-to-pay threshold of $50,000/QALY, which is considered a conservative estimate for cost-effectiveness in the U.S. (14).

Model

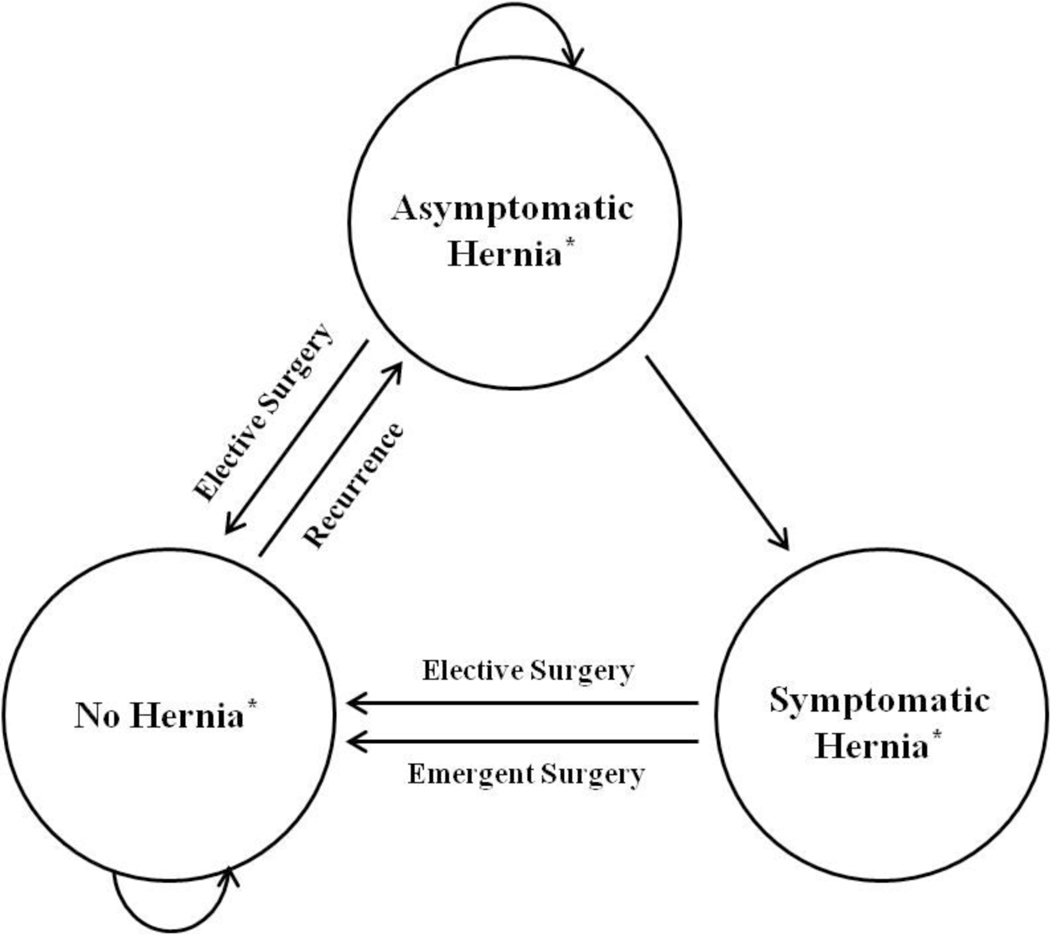

The model consisted of mutually exclusive health states, including: asymptomatic reducible ventral hernia, symptomatic reducible ventral hernia, no ventral hernia (status post repair), and death (Figure 1). We performed first-order Monte Carlo simulation, in which individual patients were simulated via a series of transitions between the different health states using a yearly cycle. We simulated cohorts with age and sex distributions (mean age 58y, 63% female) similar to patients undergoing VHR in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), a U.S.-based, nationally-representative sample, using International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes to define VHR, as previously described (Supplemental Appendix) (15). We performed internal validation of the model by comparing model-generated life expectancy with U.S. life tables (16) and model-generated proportion of crossovers from watchful waiting to surgery with the Denmark-based data used to model this event (5).

Figure 1.

Model diagram illustrating possible transitions between health states. All patients enter the model in the asymptomatic hernia state. Those in the repair at diagnosis strategies transition to the no hernia state in the first cycle after undergoing elective surgery. Those in the watchful waiting strategy remain in the asymptomatic hernia state and are at risk of developing symptoms, either with or without incarceration; those with incarceration undergo emergency surgery, while those who are symptomatic without incarceration undergo elective repair within the same year that symptoms develop. After surgery, all patients are at risk of ventral hernia recurrence. *There is the possibility to transition to death from all health states.

Clinical strategies

In the repair-at-diagnosis strategies, all patients underwent repair, either open or laparoscopic, upon entry into the model and transitioned to the no ventral hernia state. They were followed post-operatively with 2 outpatient visits for uncomplicated repairs and 4 for complicated repairs. These patients were then at yearly risk of recurrence. In the watchful waiting strategy, we assumed all patients had minimal to no symptoms due to the ventral hernia; they entered the model in the asymptomatic reducible ventral hernia state and were at yearly risk of becoming symptomatic over the course of their lifetimes. These patients were followed clinically with a yearly outpatient visit. Additional outpatient visits were assigned if a patient became symptomatic, with 4 visits assumed in the year of developing symptoms. Of those becoming symptomatic, a small proportion presented with incarceration and underwent emergent repair; the remainder of symptomatic patients underwent elective repair within the year. After repair, patients were at yearly risk of developing a recurrent ventral hernia. In all strategies, recurrence prompted an additional outpatient visit. We assumed that all recurrent hernias initially presented as asymptomatic, that recurrent hernias were only repaired if symptomatic, and that all recurrent repairs were performed as open procedures, regardless of initial repair technique. Patients with recurrent asymptomatic hernias were assumed to have similar costs and utilities as patients in the initial watchful waiting strategy.

Input parameters

We derived base case model input parameters after extensive review of the literature (Table 1). In order to reduce heterogeneity, we restricted our inputs to published estimates applying to the population of patients with incisional ventral hernias whenever possible. For patients undergoing watchful waiting, we obtained the yearly probability of developing symptoms and the probability of acute incarceration from a retrospective cohort study in Denmark, which reported 19% crossover from watchful waiting to surgery at 5y (5). Based upon a greater early risk of developing symptoms, we derived early (≤2y after diagnosis; 7.8% per year) and late (>2y after diagnosis; 1.6% per year) risks of developing symptoms. We derived the risk of operative mortality due to VHR from the NIS, stratified by urgency of the case (elective: 0.3%, emergent: 0.7%) (15). We captured serious post-operative complications with 30-day readmission rates specific to VHR, stratified by urgency from the Danish Hernia Database, a nationwide cohort study (elective: 13%, emergent: 22%) (17). Recurrence risk was 6.6% per year, from a retrospective cohort study in New York (10). Multiple meta-analyses comparing laparoscopic and open approaches to VHR have not demonstrated a difference in recurrence rates by approach (18–22). We applied background, age-stratified, all-cause mortality rates for the overall U.S. population (16).

Table 1.

Base case model inputs

| Parameter | Estimate | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort characteristics | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 58 (15) | Wolf, et al (15) |

| Sex, % female | 63 | Wolf, et al (15) |

| Clinical data | ||

| Developing symptoms during watchful waiting, yearly probability, <2y from diagnosis | 0.078 | Kokotovic, et al (5) |

| Developing symptoms during watchful waiting, yearly probability, ≥2y from diagnosis | 0.016 | Kokotovic, et al (5) |

| Acute incarceration in those developing symptoms, one-time probability | 0.13 | Kokotovic, et al (5) |

| In-hospital operative mortality, one-time probability | Wolf, et al (15) | |

| Elective ventral hernia repair* | 0.0025 | |

| Emergent ventral hernia repair | 0.0072 | |

| 30-day post-operative readmission, one-time probability | Helgstrand, et al (17) | |

| Elective ventral hernia repair* | 0.13 | |

| Emergent ventral hernia repair | 0.22 | |

| Ventral hernia recurrence, yearly probability† | 0.066 | Stey, et al (10) |

| Cost data (2015 U.S. dollars) | ||

| Hospital admission for emergency ventral hernia repair, mean (SD) | Wolf, et al (15)‡ | |

| <45y | 12,176 (320) | |

| 45–54y | 14,272 (402) | |

| 55–64y | 15,509 (511) | |

| 65–74y | 16,730 (560) | |

| 75–84y | 18,183 (744) | |

| ≥85y | 19,574 (1,010) | |

| Hospital admission for elective ventral hernia repair, laparoscopic, mean (SD) | Wolf, et al (15)‡ | |

| <45y | 13,199 (695) | |

| 45–54y | 13,809 (694) | |

| 55–64y | 14,154 (889) | |

| 65–74y | 14,734 (835) | |

| 75–84y | 13,367 (416) | |

| ≥85y | 16,221 (2,259) | |

| Hospital admission for elective ventral hernia repair, open, mean (SD) | Wolf, et al (15)‡ | |

| <45y | 12,179 (379) | |

| 45–54y | 13,284 (411) | |

| 55–64y | 13,624 (476) | |

| 65–74y | 13,389 (414) | |

| 75–84y | 13,367 (416) | |

| ≥85y | 12,845 (883) | |

| Hospital 30-day readmission after surgery, mean (SD) | 19,604 (2,580) | Lawson, et al (23) |

| Outpatient surgical visit, mean (SD) | 262 (120) | Davis and Carper (24) |

| Annual healthcare-related consumption costs per person, mean§ | Neumann, et al (11) | |

| 0–24y | 491 | |

| 25–34y | 814 | |

| 35–44y | 976 | |

| 45–54y | 1,465 | |

| 55–64y | 2,170 | |

| 65–74y | 2,842 | |

| ≥75y | 3,193 | |

| Informal healthcare sector costs for outpatient visit (time, transportation), mean (SD) | 28 (31) | Scott, et al (26) |

| Annual earnings per person, mean§ | Neumann, et al (11) | |

| 0–24y | 21,225 | |

| 25–34y | 41,524 | |

| 35–44y | 53,448 | |

| 45–54y | 54,887 | |

| 55–64y | 55,490 | |

| 65–74y | 42,992 | |

| ≥75y | 38,812 | |

| Quality of life data | ||

| Utilities, well population, mean (SD) | Hanmer, et al (27) | |

| Female | ||

| 20–29y | 0.827 (0.006) | |

| 30–39y | 0.818 (0.006) | |

| 40–49y | 0.804 (0.006) | |

| 50–59y | 0.788 (0.007) | |

| 60–69y | 0.784 (0.010) | |

| 70–79y | 0.748 (0.012) | |

| 80–89y | 0.700 (0.016) | |

| Male | ||

| 20–29y | 0.857 (0.006) | |

| 30–39y | 0.849 (0.006) | |

| 40–49y | 0.831 (0.006) | |

| 50–59y | 0.819 (0.008) | |

| 60–69y | 0.803 (0.010) | |

| 70–79y | 0.770 (0.013) | |

| 80–89y | 0.742 (0.019) | |

| Utility, watchful waiting, mean (SD) | Stey, et al (10)‖ | |

| Female | ||

| 20–29y | 0.714 (0.006) | |

| 30–39y | 0.706 (0.006) | |

| 40–49y | 0.694 (0.006) | |

| 50–59y | 0.680 (0.007) | |

| 60–69y | 0.677 (0.010) | |

| 70–79y | 0.645 (0.012) | |

| 80–89y | 0.604 (0.016) | |

| Male | ||

| 20–29y | 0.712 (0.006) | |

| 30–39y | 0.705 (0.006) | |

| 40–49y | 0.690 (0.006) | |

| 50–59y | 0.680 (0.008) | |

| 60–69y | 0.667 (0.010) | |

| 70–79y | 0.639 (0.013) | |

| 80–89y | 0.616 (0.019) | |

| Utility, status post emergency ventral hernia repair, uncomplicated, mean (SD) | 0.717 (0.04) | Stey, et al (10)¶ |

| Utility, status post emergency ventral hernia repair, complicated, mean (SD) | 0.713 (0.04) | Stey, et al (10)¶ |

| Utility, status post elective ventral hernia repair, uncomplicated, mean (SD) | 0.753 (0.03) | Stey, et al (10)¶ |

| Utility, status post elective ventral hernia repair, complicated, mean (SD) | 0.747 (0.03) | Stey, et al (10)¶ |

| Utility, status post laparoscopic ventral hernia repair, uncomplicated mean (SD) | 0.799 (0.06) | Hope, et al (28)¶ |

| Utility, status post laparoscopic ventral hernia repair, complicated, mean (SD) | 0.788 (0.06) | Hope, et al (28)¶ |

No significant difference between laparoscopic and open repairs

No significant difference between elective and emergent repairs

Additional primary data analysis to stratify costs by urgency of case and repair technique

Gamma distributions created with standard deviation assumed to be equal to the mean

Percent reduction by sex applied based on decrease in utility observed in Stey, et al. study, 13.7% reduction for females and 17.0% reduction for males

Post-operative utilities were represented by a weighted average of the utility of watchful waiting for 1 month and post-operative utility at 1 year for 11 months for uncomplicated cases and a weighted average of the utility of watchful waiting for 2 months and post-operative utility at 1 year for 10 months for complicated cases. If the post-operative utility was greater than the age-dependent well utility, the well utility was applied in the weighted average calculation instead of the post-operative utility.

Direct, ventral hernia-related medical costs for primary hospitalizations ranged from $12,176 to $19,574. We calculated direct, ventral hernia-related medical costs for primary hospitalizations from the NIS by multiplying hospital charges for each admission by cost-to-charge ratios, as published elsewhere (15). These were stratified by patient age, urgency of the case, and, for elective cases, the repair technique (open versus laparoscopic). Emergent cases were not stratified by repair technique as the vast majority were performed open. Costs for VHR-related readmissions were based on a report linking National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) readmissions to Medicare inpatient claims, with mean costs reported as $19,604 (SD 2,580) (23). Costs for outpatient surgical visits were defined as average expense for an office-based visit from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (24). Direct medical costs for non-ventral hernia-related care, or healthcare-related consumption costs, were applied from published data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics; these increased with age, ranging from $491 to $3,193 per year (11,25).

In the base case societal perspective, informal healthcare sector costs representing post-operative disability were included as unpaid caregiver time costs, patient time costs, and transportation costs. We assumed there were no extended caregiver costs, as patients are typically independent at the time of hospital discharge after VHR. For all admissions, we included 2 days of age-based earnings to represent caregiver time costs for the day of admission and the day of discharge, as well as a half day of earnings to represent additional transportation costs, assuming a caregiver of similar age as the patient. For each admission, we included 2 weeks of age-based earnings to represent productivity costs of 2 weeks of sick leave. We included informal health care sector costs for outpatient surgical visits from a single center survey (26). A comparison of costs included for the societal and health care payer perspectives is shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Utilities applied in the model were either reported as Short Form-6D scores (10,27) or converted from Short Form-36 subcomponent scores to a health utility index using previously reported methods (28,29). We applied age- and sex-based “well” utilities, which ranged from 0.70 to 0.86, for patients in the no ventral hernia state (27). Utilities for the watchful waiting state were calculated as a percent reduction from the “well” utilities, based upon the percent reduction reported from a prospective cohort study (10), with decrements of 13.7% for females and 17.0% for males. Post-operative utility estimates were calculated from quality of life data collected at a minimum of 1 year post-operatively, due to evidence that post-operative quality of life plateaus at 1 year (10,30). We applied utilities 1 year following open and laparoscopic repair that incorporated a decreased quality of life in the first post-operative month for uncomplicated cases and the first 2 post-operative months for complicated cases. After 1 year post-operatively, we assumed that utilities returned to the age- and sex-based “well” utilities.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed one-way sensitivity analysis across plausible ranges for all model inputs and identified thresholds at which the preferred management strategy would change. In particular, we examined several variables that represent the risks associated with watchful waiting, including yearly risk of becoming symptomatic, risk of incarceration, risk of perioperative mortality due to emergency surgery, risk of complications associated with emergency surgery, cost of emergency surgery, post-operative utility following emergency surgery, and decrement in utility during watchful waiting. In addition, we examined several variables that represent the trade-offs between open and laparoscopic repair at diagnosis, including cost, post-operative quality of life, and different rates of return to work after each type of repair. We varied productivity costs associated with laparoscopic repair to represent earlier or later return to work after surgery. We performed a sensitivity analysis to represent a more homogenous group of patients, those undergoing incisional hernia repairs only. We performed two sensitivity analyses on post-operative complications: one adding risk of minor post-operative complications (31), and the other adding the risk of long-term mesh complications (32). Finally, we tested the impact of varying the discount rate. Sensitivity analysis results are displayed in terms of net monetary benefit, a measure that represents costs and benefits for each strategy in a single term at a specified willingness-to-pay (1).

| (1) |

All instances of net monetary benefit are calculated at a willingness-to-pay of $50,000/QALY.

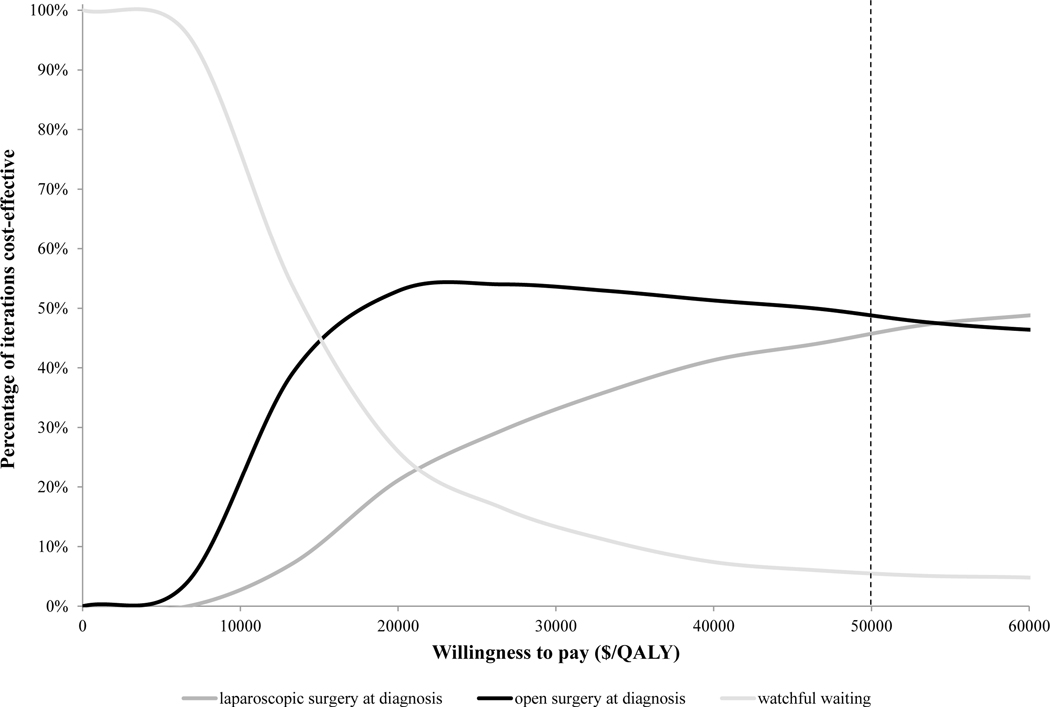

In order to assess the impact of uncertainty in the model inputs, we additionally performed probabilistic sensitivity analysis, including all uncertain variables. Using available point estimates from the literature, we derived distributions for risk of inpatient mortality after elective and emergent VHR (15,17,33), ventral hernia recurrence (10,34–36), readmission after elective and emergent repair (17,37,38), crossover from watchful waiting to surgery (5,6), acute incarceration (5,6), post-operative utility after elective laparoscopic and elective open repairs (10,28,39), and decrement in utility during watchful waiting (10,28,40). Due to limited data on post-operative utility after elective laparoscopic repair (41), we included a pooled estimate of utility after laparoscopic or open repair, to represent the scenario that there is no difference in post-operative utility based upon repair type (10,31,40,42). We then performed probabilistic sensitivity analysis (second-order Monte Carlo simulation) to assess the impact of variability in these model inputs, repeating the analysis 1000 times. The results are presented as a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve, a graph illustrating the percentage of times each strategy was optimal of the 1000 simulations. We performed all sensitivity analyses from the societal perspective.

We built the model and ran all simulations using the decision analytic software TreeAge Pro 2016 (Williamstown, MA).

RESULTS

Model validation

Graphical representations of the internal validation of the model are shown for background mortality (Supplemental Figure 1A) and crossover to surgery from watchful waiting (Supplemental Figure 1B). We demonstrated good approximation of model input and output.

Base case results

Table 2 shows clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness results for the included strategies from the societal and health care payer perspectives. In the watchful waiting strategy, 39% of patients ultimately required VHR; of these, 14% required emergent repair. Prevalence of recurrence was higher with repair at diagnosis, compared to watchful waiting (Table 2A). Quality-adjusted life expectancy ranged from 10.83 QALYs for watchful waiting to 11.54 QALYs for laparoscopic repair at diagnosis. From the societal perspective, lifetime costs varied from $49,590 for the watchful waiting strategy to $63,275 for laparoscopic repair at diagnosis. Laparoscopic repair at diagnosis provided the most benefit under the willingness-to-pay threshold of $50,000, with an ICER of $27,700/QALY compared to open repair at diagnosis. Open repair at diagnosis was also cost-effective, but provided less benefit, with an ICER of $18,903/QALY compared to watchful waiting. Results were similar for the base case analyzed under the healthcare payer perspective, with laparoscopic repair at diagnosis still the optimal strategy. Lifetime costs varied from $48,384 for the watchful waiting strategy to $60,218 for laparoscopic repair at diagnosis, with an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of $27,667/QALY (Table 2B).

Table 2A.

Clinical outcomes for the base case

| Strategy | Any Ventral Hernia Repair (%) | Emergency Ventral Hernia Repair (%) | Recurrence of Ventral Hernia (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Watchful waiting | 39 | 5.5 | 24 |

| Open repair at diagnosis | 100 | 2.5 | 70 |

| Laparoscopic repair at diagnosis | 100 | 2.5 | 70 |

Table 2B.

Cost-effectiveness results for the base case from the societal and healthcare payer perspectives

| Strategy | Societal Perspective | Healthcare Payer Perspective | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime Cost ($)* | Effectiveness (QALY) | Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio ($/QALY) | Lifetime Cost ($)* | Effectiveness (QALY) | Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio ($/QALY) | |

| Watchful waiting | 49,590 | 10.83 | -- | 48,384 | 10.83 | -- |

| Open repair at diagnosis | 62,444 | 11.51 | 18,903 | 59,388 | 11.51 | 16,182 |

| Laparoscopic repair at diagnosis | 63,275 | 11.54 | 27,700 | 60,218 | 11.54 | 27,667 |

All costs reported in 2015 U.S. dollars

Sensitivity analyses

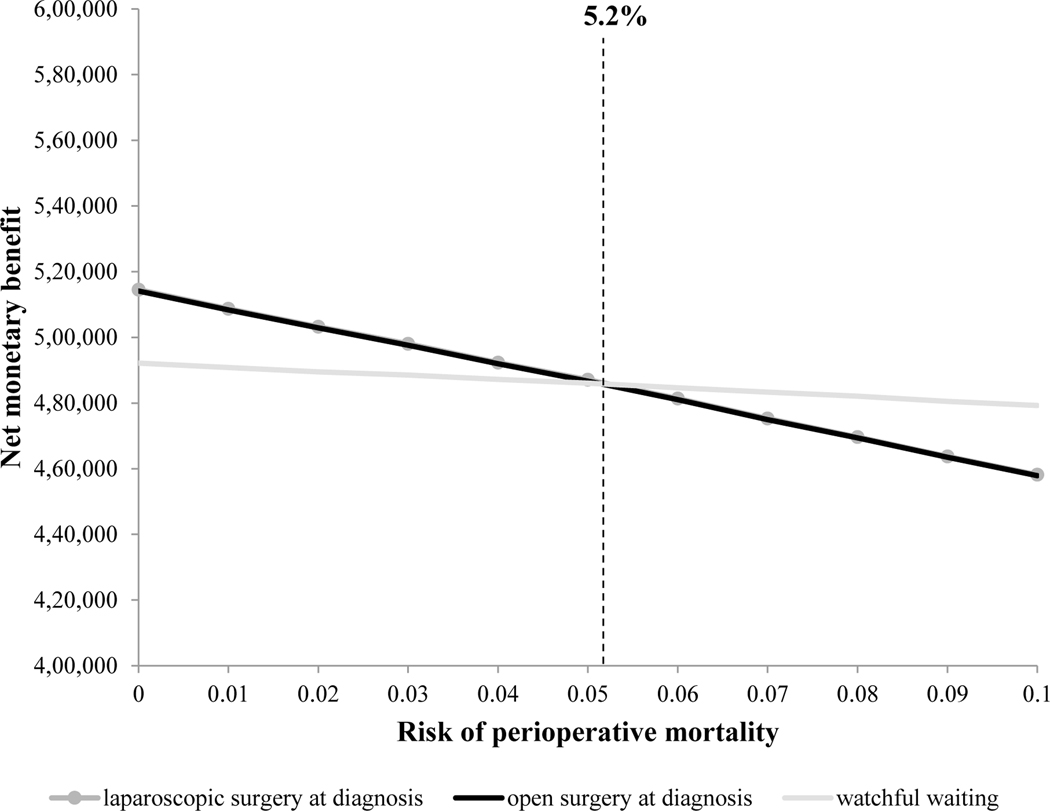

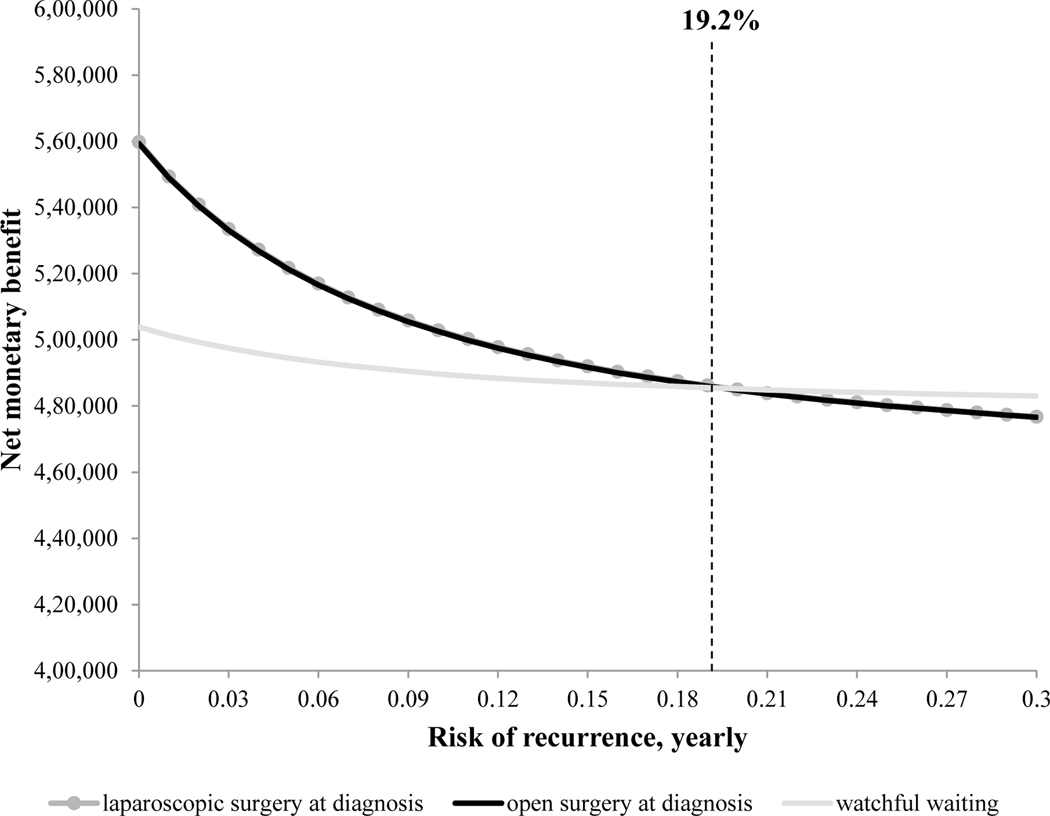

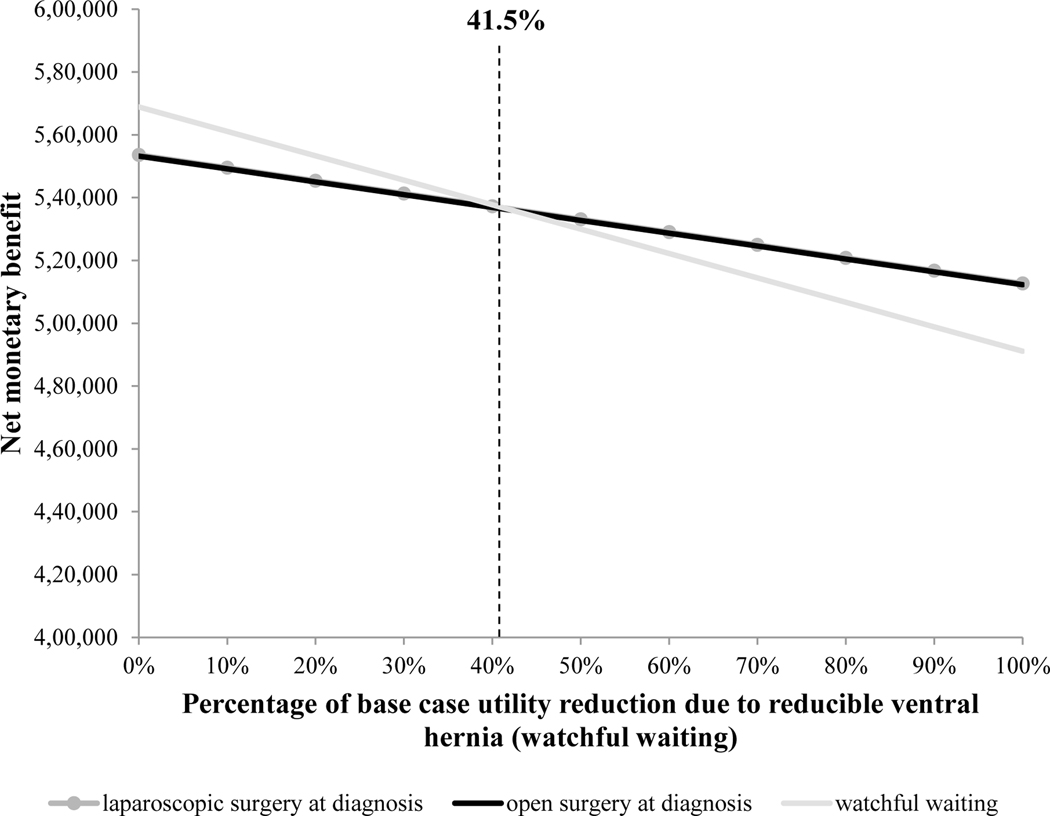

Thresholds for key parameters at which the optimal management strategy changes are shown graphically in Figure 3. For patients with risk of perioperative mortality greater than 5.2% (Figure 2A) or yearly risk of post-operative ventral hernia recurrence greater than 19.2% (Figure 2B), the optimal strategy changed from laparoscopic repair at diagnosis to watchful waiting. Figure 2C illustrates the decrement in utility that patients experience between “well,” age-specific utility, and the utility associated with reducible ventral hernia, varying the base case value from 0% to 100%. At 41.5% of the base case value, or an absolute utility decrement during watchful waiting of 5.7% for females and 7.1% for males, watchful waiting became the optimal strategy.

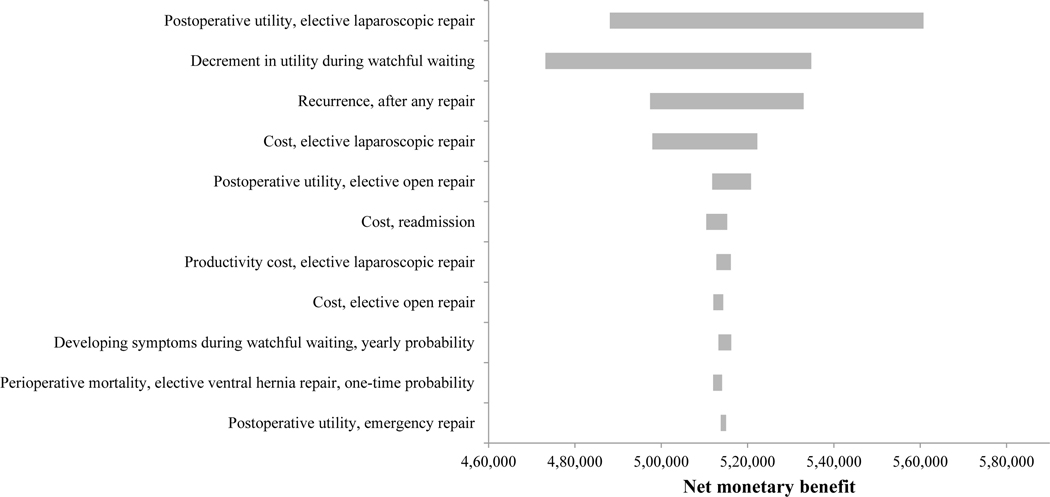

Figure 3.

Tornado diagram demonstrating variability in the net monetary benefit for laparoscopic repair at diagnosis associated with varying each selected input parameter from 50% to 200% of its base case value. Strategies are ordered from top to bottom based on magnitude of impact on the outcome.

Figure 2.

One-way sensitivity analyses on risk of perioperative mortality with elective repair (A), yearly risk of recurrence (B), and decrement in utility from “well” age-specific utility during watchful waiting (C). Outcomes for each strategy are expressed in terms of net monetary benefit, with the strategy with the highest net monetary benefit designated as the optimal strategy. Thresholds at which the optimal management strategy changes are marked with a vertical dashed line.

Of the variables that represent risks associated with watchful waiting, the results were most sensitive to ventral hernia recurrence and developing symptoms during watchful waiting. Varying the risk of recurrence from half to twice the base case value was associated with a decrease in net monetary benefit of $35,400 for laparoscopic repair at diagnosis and $8,700 for watchful waiting. Varying the risk of developing symptoms during watchful waiting from half to twice the base case value was associated with an increase in net monetary benefit of $9,500, driven by the decreased quality of life during watchful waiting. Of the variables that represent the trade-offs between open and laparoscopic repair at diagnosis, cost and post-operative utility were the most influential. If the cost of open repair decreased by 2.5% ($300-$340) or the post-operative utility after open repair increased by 0.8% (0.006), open repair at diagnosis became the preferred strategy.

Defining our population more strictly as only those undergoing incisional hernia repair had minimal impact on the ICERs. Sensitivity analysis including minor post-operative complications showed an increase in the ICER for open repair from $18,903/QALY to $19,371/QALY and a corresponding decrease in the ICER for laparoscopic repair from $27,700/QALY to $20,200/QALY. Adding the risk of long-term mesh complications, which occur more frequently after open repairs, resulted in the laparoscopic repair strategy absolutely dominating – or being less expensive and more effective than – open repair. Finally, varying the rate at which future costs and benefits were discounted from 0% to 5% corresponded to minimal change in the ICER for laparoscopic repair at diagnosis. Figure 3 shows the absolute impact of the most influential factors on the net monetary benefit associated with laparoscopic repair at diagnosis.

The results of the probabilistic sensitivity analysis are shown in Figure 4. When the willingness-to-pay threshold was low, watchful waiting was more likely to be the preferred strategy, while at higher willingness-to-pay thresholds, laparoscopic repair at diagnosis became increasingly likely to be the preferred strategy. At a willingness-to-pay of $50,000/QALY, the optimal strategy was laparoscopic repair at diagnosis 45.5% of the time, open repair at diagnosis 49.1% of the time, and watchful waiting 5.4% of the time (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve. The x-axis represents willingness-to-pay and the y-axis represents the percentage of times each strategy was optimal in probabilistic sensitivity analysis. At a willingness-to-pay of $50,000/QALY, the optimal strategy was laparoscopic repair at diagnosis 45.5% of the time, open repair at diagnosis 49.1% of the time, and watchful waiting 5.4% of the time.

DISCUSSION

We forecasted lifetime clinical and economic outcomes associated with different management strategies for reducible ventral hernias. In a typical cohort of patients with ventral hernia, laparoscopic repair at the time of diagnosis was very cost-effective compared to other interventions routinely used in U.S. healthcare. The ICER of $27,700/QALY was substantially less than a willingness-to-pay threshold of $50,000/QALY, an accepted conservative estimate of cost-effectiveness (14). In cohorts of patients with ventral hernia with high risk of perioperative mortality or hernia recurrence, watchful waiting became the optimal strategy. In patients that experience only a small decrement in quality of life due to living with a ventral hernia, watchful waiting was also the optimal strategy. When comparing open and laparoscopic VHRs, our results were sensitive to differences in cost and quality of life. The results support either repair technique – surgeon and patient preference, as well as local costs of care, may influence this decision.

These findings are consistent with and extend the results of previous studies. Stey et al. published a cost-effectiveness analysis that applied data from a single-center observational study and found that prompt elective VHR was cost-effective, with an estimated ICER of $9,450 compared to watchful waiting. This study did not include direct non-ventral hernia related costs or future recurrences, which may explain the higher ICER in the present study (10). In addition, a recent prospective, propensity-matched cohort study including patients with ventral hernias and comorbidities found that elective repair improved quality of life at 6 month follow-up, while watchful waiting was associated with lower function scores at 6 months (43). The present study supports these previously published results. We additionally modeled different repair techniques (laparoscopic versus open) and incorporated a more sophisticated model that allowed us to closely represent ventral hernia disease, including the transition from watchful waiting to elective surgery due to worsening symptoms, multiple recurrences and repairs, and age-dependent risk of mortality from competing causes. Since the study by Stey et al. was published, new data are available on the probability of developing symptoms during watchful waiting, with crossover from watchful waiting to surgery reported from 19% at 5y (5) to 33% at 4y (6), with the majority of crossovers occurring within 2y after diagnosis. When this risk was simulated over each patient’s lifetime, we found that the cumulative risk of undergoing surgery during watchful waiting was substantial, which is consistent with reported long-term outcomes of watchful waiting from the inguinal hernia literature (4).

There are several implications of this work. First, we found that operative repair at the time of diagnosis is a cost-effective strategy for the management of ventral hernia. However, the decision about when and if to operate depends on patient-level characteristics (2). Therefore, we identified thresholds for certain high risk cohorts, which may serve as tools for clinical decision-making. As surgeons often pursue watchful waiting in the setting of patient comorbidities (5,43,44), we focused on operative risk and risk of post-operative hernia recurrence to assess outcomes in these patient populations. Risk of perioperative mortality can be predicted based on individual patient characteristics using the American College of Surgeons NSQIP Surgical Risk Calculator (45) and risk of ventral hernia recurrence has been modeled based on body mass index and smoking status (46), making these thresholds practical for use in clinical practice. Our results inform clinical decision-making regarding complex abdominal wall reconstruction, where prevalence of recurrence as high as 50% has been reported (47,48), suggesting these patients are better served with watchful waiting.

When comparing open and laparoscopic repairs, our results were extremely similar and were sensitive to differences in costs and post-operative quality of life. In the base case, laparoscopic repair at diagnosis was the optimal strategy; however, in probabilistic sensitivity analysis open repair at diagnosis was the optimal strategy 49% of the time at a willingness-to-pay of $50,000/QALY. These results suggest that the best repair technique may depend on local costs and factors that affect patient post-operative quality of life. Efforts for future data collection may target quality of life after VHR. Not only are these data key to the outcomes predicted in the current study, but these measurements will also be important as we seek to understand the impact of new technologies, such as robotic repair, on patient outcomes and satisfaction after surgery.

Our results must be interpreted in the context of the study design. In order to incorporate the best available published estimates, we derived input parameters from multiple sources. We included data from both European and U.S.-based sources, as well as some data that represented a mix of ventral hernia types and some that represented incisional hernias only. Due to the nature of the data we applied, we did not have sufficient information to stratify patients by a clinical classification system. We acknowledge that hernia size and severity are among the factors that surgeons consider when selecting a management strategy for an individual patient. While our simulated patient population was heterogeneous, our model treated each management strategy equally, by applying each of the modeled management strategies to the same hypothetical patient population. Moreover, while we could not explicitly account for the impact of hernia size and severity, we did so implicitly by using probabilistic sensitivity analysis, which took into consideration data points for subpopulations of different hernia types (umbilical, epigastric, incisional), where available. Nonetheless, we realize that these methods may not completely control for the impact of hernia complexity on selection of a management strategy. The best available data on outcomes from watchful waiting were from retrospective cohort studies, which may introduce bias due to the non-random assignment of each patient’s treatment plan. We modeled recurrence as a binary outcome, as commonly reported in the literature (10,32,34,35); this aspect of the analysis may limit generalizability to populations of patients with complex, partially, and multiply recurrent hernias in whom a small recurrence should not be considered an operative failure.

We were unable to find isolated post-operative utility estimates for elective open VHRs that were consistent with our other utility estimates – the estimate for post-operative utility status post elective VHR from Stey et al. represents a cohort with a majority of open repairs, but includes some laparoscopic repairs. Any bias from use of this estimate would be in a conservative direction – inclusion of laparoscopic repairs, which have higher post-operative utility, would make open repairs seem more advantageous. Yet laparoscopic repairs still appeared superior in this analysis. Though estimates for long-term quality of life outcomes are not well-reported, we applied the best available estimates from a robust, prospective study, which included an average of 4 years post-operative follow-up (range:1–6 years) (10). Non-healthcare-related consumption costs were excluded; however given the similar predicted survival among the different strategies, this may be considered reasonable (11). Finally, while there is clinical interest in modeling subgroups of patients by patient-level factors such as body mass index, smoking status, or functional status, or hernia features such as size, location, or specific repair type, robust data are lacking on outcomes for subgroups of patients with ventral hernias. We tested all assumptions with sensitivity analysis, which demonstrated our results to be robust.

In conclusion, we used a decision analytic approach to examine the ideal management for reducible ventral hernias. We found that prompt repair at the time of diagnosis is very cost-effective for the general population of patients with ventral hernia. In subgroups of patients that are at high risk of perioperative mortality or post-operative ventral hernia recurrence, watchful waiting may instead be preferred. As current perioperative risk calculators may be of value in identifying such patients, this simulation model provides insight for surgeons making clinical decisions about timing of VHR and which patients may benefit from surgery. The findings are also informative for policy-makers responsible for allocating healthcare resources. The technique of decision analysis and the simulation model presented in this paper may be applied to answer additional questions surrounding the management of ventral hernia. As new data become available, the model may be applied to further investigate specific subpopulations of patients, such as diabetics, active smokers, or other patients that may warrant different management than the general population of patients with ventral hernia.

Supplementary Material

Internal validation of the model using mortality data from the U.S. life tables (A) and data on crossover from watchful waiting to surgical repair (B).

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the American College of Surgeons Resident Research Scholarship to LLW and the U.S. National Institute of Health/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (K24AR057827-02) to EL.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: This work was supported by the American College of Surgeons Resident Research Scholarship to LLW and the U.S. National Institute of Health/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (K24AR057827-02) to EL. Not related to this work, AHH is the PI of a contract (AD-1306-03980) with the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute entitled “Patient-Centered Approaches to Collect Sexual Orientation/Gender Identity in the ED” and a Harvard Surgery Affinity Research Collaborative (ARC) Program Grant entitled “Mitigating Disparities Through Enhancing Surgeons’ Ability To Provide Culturally Relevant Care.” For the remaining authors none were declared.

References

- 1.Poulose BK, Shelton J, Phillips S, et al. Epidemiology and cost of ventral hernia repair: making the case for hernia research. Hernia. 2012;16:179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang MK, Holihan JL, Itani K, et al. Ventral Hernia Management. Ann Surg. 2017; 265:80–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzgibbons RJ, Giobbie-Hurder A, Gibbs JO, et al. Watchful waiting vs repair of inguinal hernia in minimally symptomatic men: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2006;295:285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzgibbons RJ, Ramanan B, Arya S, et al. Long-term results of a randomized controlled trial of a nonoperative strategy (watchful waiting) for men with minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias. Ann Surg. 2013;258:508–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kokotovic D, Sjølander H, Gögenur I, et al. Watchful waiting as a treatment strategy for patients with a ventral hernia appears to be safe. Hernia. 2016; 20:281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verhelst J, Timmermans L, van de Velde M, et al. Watchful waiting in incisional hernia: Is it safe? Surgery. 2015;157:297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellows CF, Robinson C, Fitzgibbons RJ, et al. Watchful waiting for ventral hernias: a longitudinal study. Am Surg. 2014;80:245–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lauscher JC, Martus P, Stroux A, et al. Development of a clinical trial to determine whether watchful waiting is an acceptable alternative to surgical repair for patients with oligosymptomatic incisional hernia: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lauscher JC, Leonhardt M, Martus P, et al. [Watchful waiting vs surgical repair of oligosymptomatic incisional hernias : Current status of the AWARE study]. Der Chir Zeitschrift für alle Gebiete der Oper Medizen. 2016;87:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stey AM, Danzig M, Qiu S, et al. Cost-utility analysis of repair of reducible ventral hernia. Surgery. 2014;155:1081–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neumann PJ, Sanders GD, Russell LB, Siegel JE, Ganiats TG. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Department of Labor. Consumer Price Index. 1998–2015 [Internet]. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/cpi/. Accessed December 9, 2016.

- 13.Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, et al. Recommendations for Conduct, Methodological Practices, and Reporting of Cost-effectiveness Analyses. JAMA. 2016;316:1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ubel PA, Hirth RA, Chernew ME, et al. What is the price of life and why doesn’t it increase at the rate of inflation? Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1637–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf LL, Scott JW, Zogg CK, et al. Predictors of emergency ventral hernia repair: Targets to improve patient access and guide patient selection for elective repair. Surgery. 2016;160:1379–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell FC, Miller ML. Life Tables for the United States Social Security Area 1900–2100. Table 6 -- Period Life Tables for the Social Security Area by Calendar Year and Sex [Internet]. 2010. Available from: http://www.ssa.gov/oact/NOTES/as120/LifeTables_Tbl_6_2010.html. Accessed September 16, 2016.

- 17.Helgstrand F, Rosenberg J, Kehlet H, et al. Outcomes after emergency versus elective ventral hernia repair: A prospective nationwide study. World J Surg. 2013;37:2273–2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Awaiz A, Rahman F, Hossain MB, et al. Meta-analysis and systematic review of laparoscopic versus open mesh repair for elective incisional hernia. Hernia. 2015;19:449–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al Chalabi H, Larkin J, Mehigan B, et al. A systematic review of laparoscopic versus open abdominal incisional hernia repair, with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg. 2015;20:65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Zhou H, Chai Y, et al. Laparoscopic versus open incisional and ventral hernia repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2014;38:2233–2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sauerland S, Walgenbach M, Habermalz B, et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgical techniques for ventral or incisional hernia repair. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2011:CD007781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forbes SS, Eskicioglu C, McLeod RS, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing open and laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair with mesh. Br J Surg. 2009;96:851–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawson EH, Hall BL, Louie R, et al. Association between occurrence of a postoperative complication and readmission: implications for quality improvement and cost savings. Ann Surg. 2013;258:10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis KE, Carper K. Use and Expenses for Office-Based Physician Visits by Specialty, 2009: Estimates for the U.S. Civilian Noninstitutionalized Population. Statistical Brief #381. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD: [Internet]. Available from: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st381/stat381.pdf. Accessed September 16, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Expenditure Survery. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor Statistics; [Internet]. 2014. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/cex/2013/combined/age.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott AR, Rush AJ, Naik AD, et al. Surgical follow-up costs disproportionately impact low-income patients. J Surg Res. 2015;199:32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanmer J, Lawrence WF, Anderson JP, et al. Report of nationally representative values for the noninstitutionalized US adult population for 7 health-related quality-of-life scores. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hope WW, Lincourt AE, Newcomb WL, et al. Comparing quality oflife outcomes in symptomatic patients undergoing laparoscopic or open ventral hernia repair. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008;18:567–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nichol MB, Sengupta N, Globe DR. Evaluating quality-adjusted life years: estimation of the health utility index (HUI2) from the SF-36. Med Decis Making. 2011;21:105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Litwin MS, McGuigan KA, Shpall AI, et al. Recovery of health related quality of life in the year after radical prostatectomy: early experience. J Urol. 1999;161:515–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itani KMF, Hur K, Kim LT, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic and open repair with mesh for the treatment of ventral incisional hernia: a randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2010;145:322–328; discussion 328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kokotovic D, Bisgaard T, Helgstrand F. Long-term recurrence and complications associated with elective incisional hernia repair. JAMA. 2016;316:1575–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altom LK, Snyder CW, Gray SH, et al. Outcomes of emergent incisional hernia repair. Am Surg. 2011;77:971–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hawn MT, Snyder CW, Graham LA, et al. Long-term follow-up of technical outcomes for incisional hernia repair. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:648–655, 655–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Helgstrand F, Rosenberg J, Kehlet H, et al. Nationwide prospective study of outcomes after elective incisional hernia repair. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Helgstrand F, Rosenberg J, Kehlet H, et al. Reoperation versus clinical recurrence rate after ventral hernia repair. Ann Surg. 2012;256:955–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merkow RP, Ju MH, Chung JW, et al. Underlying reasons associated with hospital readmission following surgery in the United States. JAMA. 2015;313:483–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bisgaard T, Kehlet H, Bay-Nielsen M, et al. A nationwide study on readmission, morbidity, and mortality after umbilical and epigastric hernia repair. Hernia. 2011;15:541–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wassenaar E, Schoenmaeckers E, Raymakers J, et al. Mesh-fixation method and pain and quality of life after laparoscopic ventral or incisional hernia repair: a randomized trial of three fixation techniques. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1296–1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mussack T, Ladurner R, Vogel T, et al. Health-related quality-of-life changes after laparoscopic and open incisional hernia repair: a matched pair analysis. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:410–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jensen KK, Henriksen NA, Harling H. Standardized measurement of quality of life after incisional hernia repair: a systematic review. Am J Surg. 2014;208:485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asencio F, Aguiló J, Peiró S, et al. Open randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open incisional hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1441–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holihan JL, Henchcliffe BE, Mo J, et al. Is nonoperative management warranted in ventral hernia patients with comorbidities?: a case-matched, prospective, patient-centered study. Ann Surg. 2016;264:585–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Evans KK, Chim H, Patel KM, et al. Survey on ventral hernias: surgeon indications, contraindications, and management of large ventral hernias. Am Surg. 2012;78:388–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y, Cohen ME, Hall BL, et al. Evaluation and enhancement of calibration in the American College of Surgeons NSQIP Surgical Risk Calculator. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223:231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stey AM, Russell MM, Sugar CA, et al. Extending the value of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program claims dataset to study long-term outcomes: Rate of repeat ventral hernia repair. Surgery. 2015;157:1157–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hodgkinson JD, Maeda Y, Leo CA, et al. Complex abdominal wall reconstruction in the setting of active infection and contamination: a systematic review of hernia and fistula recurrence rates. Color Dis. 2017;19:319–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diaz JJ, Cullinane DC, Khwaja KA, et al. Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma: management of the open abdomen, part III--review of abdominal wall reconstruction. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:376–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Internal validation of the model using mortality data from the U.S. life tables (A) and data on crossover from watchful waiting to surgical repair (B).