Abstract

Although recognised as effective measures to curb the spread of the COVID-19 outbreak, social distancing and self-isolation have been suggested to generate a burden throughout the population. To provide scientific data to help identify risk factors for the psychosocial strain during the COVID-19 outbreak, an international cross-disciplinary online survey was circulated in April 2020. This report outlines the mental, emotional and behavioural consequences of COVID-19 home confinement. The ECLB-COVID19 electronic survey was designed by a steering group of multidisciplinary scientists, following a structured review of the literature. The survey was uploaded and shared on the Google online survey platform and was promoted by thirty-five research organizations from Europe, North Africa, Western Asia and the Americas. Questions were presented in a differential format with questions related to responses “before” and “during” the confinement period. 1047 replies (54% women) from Western Asia (36%), North Africa (40%), Europe (21%) and other continents (3%) were analysed. The COVID-19 home confinement evoked a negative effect on mental wellbeing and emotional status (P < 0.001; 0.43 ≤ d ≤ 0.65) with a greater proportion of individuals experiencing psychosocial and emotional disorders (+10% to +16.5%). These psychosocial tolls were associated with unhealthy lifestyle behaviours with a greater proportion of individuals experiencing (i) physical (+15.2%) and social (+71.2%) inactivity, (ii) poor sleep quality (+12.8%), (iii) unhealthy diet behaviours (+10%), and (iv) unemployment (6%). Conversely, participants demonstrated a greater use (+15%) of technology during the confinement period. These findings elucidate the risk of psychosocial strain during the COVID-19 home confinement period and provide a clear remit for the urgent implementation of technology-based intervention to foster an Active and Healthy Confinement Lifestyle AHCL).

Keywords: Public health, Pandemic, Mental wellbeing, Depression, Satisfaction, Behaviours

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by the discovered severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. The disease was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, the capital of China’s Hubei province, and has since spread globally to affect around 6 million people (as of the 4th week of May 2020), including nearly 350 000 deaths in more than 220 countries [2]. Due to the consistently growing number of confirmed cases and to avoid overwhelming health systems, WHO and public health authorities around the world have been acting to contain the rapid spread of the COVID-19 outbreak, with primary measures focusing on social distancing, self-isolation, and nationwide lockdowns.

Although recognized with hygiene care as one of the most effective measures to curb the spread of disease, the weakening of social contacts can potentially result in a devastating loss of leisure and working hours, disruption of normal lifestyle, and generation of stress throughout the population [3, 4]. As a result, anxiety, frustration, panic attacks, loss or sudden increase of appetite, insomnia, depression, mood swings, delusions, fear, sleep disorders, and suicidal/domestic violence cases have become quite common during lockdowns with helpline numbers being overloaded during the early months of the COVID-19 spread [5–8]. Similarly, Brooks et al. [9] reported several psychological issues during quarantine periods (SARS, H1N1 influenza, equine influenza and Ebola) in patients including emotional and mood disturbance, numbness, depression, irritability, stress, anger, nervousness, guilt, sadness, fear, vigilant handwashing and avoidance of crowds. During these periods of precautionary isolation, Purssell et al. [10] and Sharma et al. [11] reported negative psychological effects (i.e., increased levels of anxiety and depression). Social impacts have also been reported, including limited visiting, less interaction with providers, and social exclusion. [12]

Therefore, in such times of crisis, there is an urgent need to support mental and psychosocial well-being in target groups during outbreaks to minimize the psychosocial toll. [13] In this context, mental health initiatives focused on (i) educating public and health care workers on how to properly deal with the immense pressure and anxiety, (ii) providing targeted mental health surveillance followed by effective interventions for at-risk populations (e.g., patients with prior mental health diagnosis, the elderly, people in total home confinement), and (iii) proactively establishing mental health programmes specifically designed to manage the pandemic’s aftermath. These have been recently suggested as urgent measures of prevention and early intervention [3, 14, 15]. The psychosocial needs of at-risk individuals, including those in quarantine and/or home confinement, are suggested to be unique [15]. Preventive, early and rehabilitation-focused interventions to promote mental wellbeing should be designed to be “crisis-oriented” and should be informed by outcomes from scientific research, as opposed to hypothetical and speculative suggestions. Consistent with this standpoint, a recent “paper advises” article highlighted the urgent need of research to help improve understanding of the mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for the public [16]. Therefore, to provide scientific data to help characterise the psychosocial effects of the COVID-19 crisis, our ECLB-COVID19 research group recently launched a multiple-language and multi-country anonymous survey to assess the “Effects of home Confinement on psychosocial health status and multiple Lifestyle Behaviours” during the COVID-19 outbreak (ECLB-COVID19).

Based on data extracted from the first thousand multi-country responses (1047 participants), the present manuscript aims to provide insight into the effect of home confinement on mental wellbeing, depression, life satisfaction and multidimension lifestyle behaviours (i.e., social participation, physical activity, dietary behaviours, sleep quality and technology use). Additionally, we aimed at identifying possible relationships between psychosocial and behavioural changes during the confinement period.

We hypothesize that social distancing would negatively affect mental and emotional wellbeing via increases in sedentary activity, social exclusion, decreasing sleep quality and lower propension of healthy diet.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We report findings on the first 1047 replies to an international online survey on mental health and multi-dimension lifestyle behaviours during home confinement (ECLB-COVID19). ECLB-COVID19 was opened on April 1, 2020, tested by the project’s steering group for a period of 1 week, before starting to spread it worldwide on April 6, 2020. Thirty-five research organizations from Europe, North Africa, Western Asia and the Americas promoted dissemination and administration of the survey. ECLB-COVID19 was administered in English, German, French, Arabic, Spanish, Portuguese, and Slovenian languages (other languages including Dutch, Persian, Italian, Greek, Russian, Indian and Malayalam have since been added). The survey included sixty-four questions on health, mental wellbeing, mood, life satisfaction and multidimension lifestyle behaviours (physical activity, diet, social participation, sleep, technology use, need of psychosocial support). All questions were presented in a differential format, to be answered directly in sequence regarding “before” and “during” confinement conditions. [17–20]

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol and the consent form were fully approved (identification code: 62/20) by the Otto von Guericke University Ethics Committee.

Survey development and promotion

The ECLB-COVID19 electronic survey was designed by a steering group of multidisciplinary scientists and academics (i.e., human science, sport science, neuropsychology and computer science) at the University of Magdeburg, Germany (principal investigator), the University of Sfax, Tunisia, the University of Münster, Germany and the University of Paris-Nanterre, France following a structured review of the literature. The survey was then reviewed and edited by over 50 colleagues and experts worldwide. The survey was uploaded and shared on the Google online survey platform. A link to the electronic survey was distributed worldwide by consortium colleagues via a range of methods: invitation via e-mails, shared in consortium faculties’ official pages, ResearchGate, LinkedIn and other social media platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp and Twitter. Members of the public were also involved in the dissemination plans of our research through the promotion of the ECLB-COVID19 survey in their networks. The survey included an introductory page describing the background and the aims of the survey, the consortium, ethics information for participants and the option to choose one of seven available languages (English, German, French, Arabic, Spanish, Portuguese, Slovenian, Dutch, Persian, Italian, Greek, Russian, Indian and Malayalam). The present study focuses on the first thousand responses (i.e., 1047 participants), which were reached on April 11, 2020, approximately one week after the survey began. This survey was open for all people worldwide aged 18 years or older. People declaring to have been diagnosed with cognitive impairment were excluded. [17–20]

Data privacy and consent to participation

During the informed consent process, survey participants were assured all data would be used only for research purposes. Participants’ answers were anonymous and confidential according to Google’s privacy policy (https://policies.google.com/privacy?hl=en). Participants were not permitted to provide their names or contact information. Additionally, participants were able to stop study participation and leave the questionnaire at any stage before the submission process; if doing so, their responses would not be saved. Responses were saved only by clicking on the provided “submit” button. By completing the survey, participants acknowledged their voluntary consent to participate in this anonymous study. Participants were requested to be honest and as accurate as possible in their responses. [17–20]

Survey questionnaires

As ECLB-COVID19 is a multi-country electronic survey designed to assess changes in multiple lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak, a collection of validated and/or crisis-oriented brief questionnaires were included. These questionnaires assess mental well-being (Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS)) [17, 21], mood and feeling (Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ)) [17, 21], life satisfaction (Short Life Satisfaction Questionnaire for Lockdowns (SLSQL)) [18], social participation (Short Social Participation Questionnaire for Lockdowns (SSPQL)) [18], physical activity (International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF)) [19, 20, 23, 24], diet behaviours (Short Diet Behaviours Questionnaire for Lockdowns (SDBQL)) [19, 20], sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)) [25] and some key questions assessing technology-use behaviours (Short Technology-use Behaviours Questionnaire for Lockdowns (STBQL)), demographic information and the need of psychosocial support. Reliability of the shortened and/or newly adopted questionnaires was tested by the project steering group through piloting, prior to survey administration. These brief crisis-oriented questionnaires showed good to excellent test-retest reliability coefficients (r = 0.84–0.96). A multi-language validated version already existed for the majority of these questionnaires and/or questions. However, for questionnaires that did not already exist in multi-language versions, we followed the procedure of translation and backtranslation, with an additional review for all language versions from the international scientists of our consortium. Detailed descriptions of the aforementioned tools including total score calculation and interpretation of each questionnaires are available as supplementary file 1. As a result, a total of 64 items were included in the ECLB-COVID19 online survey in a differential format. Each item or question requested two answers, one regarding the period before and the other regarding the period during confinement. Thus, participants were guided to compare the situations.

Given the large number of included questions and in order to give a multidimensional overview of the recorded change “during” compared to “before” the confinement period, the present paper focuses only on the total scores of the included questionnaires, without detailed analysis regarding specific changes in each questionnaire.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to define the proportion of responses for each question and the total distribution of the total score of each questionnaire. All statistical analyses were performed using the commercial statistical software STATISTICA (StatSoft, Paris, France, version 10.0). Normality of the data distribution was confirmed using the Shapiro-Wilk W-test. Values were computed and reported as mean ± SD (standard deviation). To assess significant difference in total scored responses between “before” and “during” the confinement period, paired samples t-tests were used for normally distributed data and the Wilcoxon test was used when normality was not observed. The effect size (Cohen’s d) was calculated to determine the magnitude of the change in score and interpreted using the following criteria: 0.2 ≤ d < 0.5: small, 0.5 ≤ d < 0.8: moderate, and d ≥ 0.8: large [26]. Pearson product-moment correlation tests were used to assess possible relationships between the “before-after” Δ of the assessed multidimension total scores. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Sample description

1047 participants were included in the survey preliminary sample used for the present manuscript. Overall, 54% of the sample were women and 46% were men. Geographical breakdowns were from Asian (36%, mostly from Western Asia), African (40%, mostly from North Africa), and European (21%) continents and 3% were from other continents. Age, health status, employment status, level of education, and marital status are presented in Table 1.

TablE 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants (N = 1047)

| Variables | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 484 | (46.2%) |

| Female | 563 | (53.8%) |

| Continent | ||

| North Africa | 419 | (40%) |

| Western Asia | 377 | (36%) |

| Europe | 220 | (21%) |

| Other | 31 | (3%) |

| Age | ||

| 18–35 | 577 | (55.1%) |

| 36–55 | 367 | (35.1%) |

| > 55 | 103 | (9.8%) |

| Level of Education | ||

| Master/doctorate degree | 527 | (50.3%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 397 | (37.9%) |

| Professional degree | 28 | (2.7%) |

| High school graduate, diploma or the equivalent | 69 | (6.6%) |

| No schooling completed | 26 | (2.5%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 455 | (43.5%) |

| Married/Living as couple | 562 | (53.7%) |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 30 | (2.9%) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed for wages | 538 | (51.4%) |

| Self-employed | 74 | (7.1%) |

| Out of work/Unemployed | 75 | (7.2%) |

| A student | 259 | (24.7%) |

| Retired | 23 | (2.2%) |

| Unable to work | 9 | (0.9%) |

| Problem caused by COVID-19 | 59 | (5.6%) |

| Other | 10 | (1%) |

| Health state | ||

| Healthy | 956 | (91.3%) |

| With risk factors for cardiovascular disease | 81 | (7.7%) |

| With cardiovascular disease | 10 | (1%) |

Mental wellbeing, depression, life satisfaction and need of psychosocial support

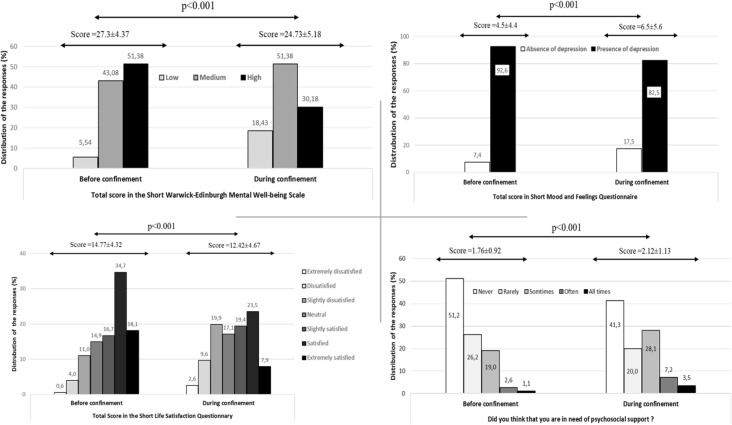

Change in the total score of the of the SWEMWBS, SMFQ, and SLSQL questionnaire and the psychological support key question from “before” to “during” the home confinement period are presented in Figure 1. Statistical analysis showed a significant difference in all tested parameters (14.12≤ t ≤ 21.05; P < 0.001, 0.43 ≤ d ≤ 0.65). Particularly, total score in mental wellbeing and life satisfaction questionnaires decreased by 9.4% (t = 18.82, p < 0.001, d = 0.58) and 16% (t = 21.05, p < 0.001, d = 0.65), respectively from “before” to “during” with more individuals reporting low mental wellbeing (+12.89%) and more people feeling dissatisfied (extremely to slightly) (+16.5%) “during” compared to “before” the confinement period. In contrast, total score in the depression monitoring questionnaire, as well as in the need of psychosocial support question, increased by 44.9% (t = 14.12, p < 0.001, d = 0.43) and 20.2% (t = 14.83, p < 0.001, d = 0.56) from “before” to “during”, respectively, with more people developing depressive symptoms/states (10%) and more people declaring a need (sometimes for all times) of psychosocial support (16.1%) “during” compared to “before” the confinement period.

FIG 1.

Response to the psychological support key question and total score of the mental wellbeing, mood and feelings, and short life satisfaction questionnaires before and during home confinement.

Social participation, physical activity, diet and sleep behaviours

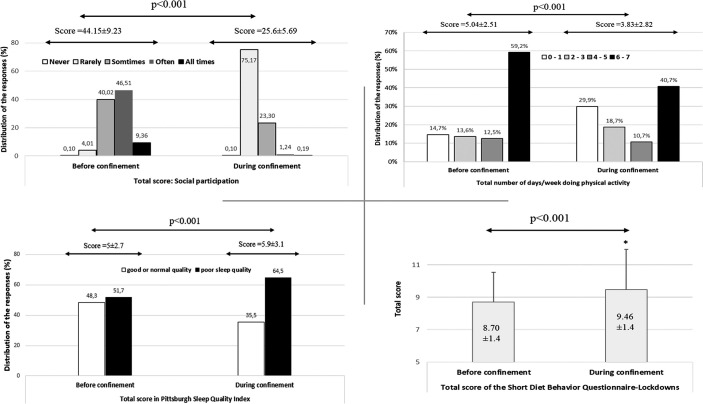

Change in the total score of the SSPQL, IPAQ-SF, SDBQL, and PSQI questionnaires from “before” to “during” the home confinement period are presented in Figure 2. Statistical analysis showed a significant difference between both periods in all tested parameters (10.66 ≤ t ≤ 69.16; P < 0.001, 0.3 ≤ d ≤ 2.14). Total score in social participation and physical activity (i.e., days/week of all physical activity) questionnaires decreased by 42% (t = 69.19 p < 0.001, d = 2.14) and 24% (t = 15.61, p < 0.001, d = 0.482), respectively, from “before” to “during,” There were more socially (+71.15%, never-rarely socially active) and physically (+15.2, 0–1 days/week of all physical activity) inactive individuals “during” compared to “before” the confinement period. In contrast, total score in the diet and sleep monitoring questionnaires increased significantly by 4.4% (t = -10.66, p < 0.001, d = 0.50) and 12% (z = 10.58, p < 0.001, d = 0.3) from “before” to “during” with more people experiencing poor sleep quality (+12.8%) and more people classifying (most of the time-always) their diet behaviours as unhealthy (10%) “during” compared to “before” the confinement period.

FIG 2.

Total score of the social participation, physical activity, diet and sleep behaviours questionnaires before and during home confinement.

Short Technology-use Lockdowns Questionnaire

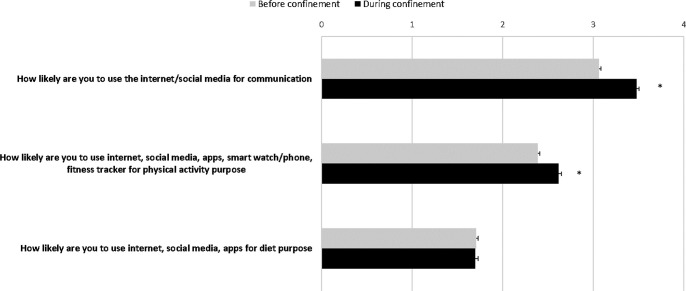

Change in technology-use score from “before” to “during” the confinement period in response to SLSQL is presented in Figure 3. Statistical analysis showed the total score of the technology-use behaviour increased significantly (8.8%) “during” compared to “before” home confinement (t = 14.01, P < 0.001, d = 0.43). Particularly, scores related to the use of internet/social media for communication significantly increased “during” compared to “before” the confinement period (t = 17.03, P < 0.001 and d = 0.54). Similarly, higher scores related to the use of technology-based tools for physical activity was registered during the confinement period (t = 9.03, p < 0.001, d = 0.28). However, no significant change was recorded for scores related to the use of technology-based tools for dietary purposes (t = 0.61, p = 0.53, d = 0.01).

FIG 3.

Responses to the Short Technology-use Lockdowns Questionnaire before and during home confinement. Values were computed and reported as mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean). *Significantly different from before confinement at p < 0.05.

Relationship between change in mental and emotional wellbeing and behavioural factors

Table 2 shows the relationship between the change “before-after” of the assessed variables. The mental and emotional related variables were significantly correlated to the majority of lifestyle behaviours (0.01 ≤ P ≤ 0.001 and 0.1 ≤ r ≤ 0.41). Particularly, Δ in total score of mood and feeling questionnaires showed significant correlations with all behavioural changes with a positive correlation with the diet and sleep behaviours (p < 0.001, 0.3 ≤ r ≤ 0.41) and negative correlation with social participation and physical activity (p < 0.001, -0.25 ≤ r ≤ -0.14). Inversely, Δ in total score of mental wellbeing and life satisfaction was positively correlated with social participation (p < 0.001, 0.23 ≤ r≤ 0.28) and physical activity (p < 0.01, 0.10 ≤ r ≤ 0.15) and negatively correlated with the diet (p < 0.001, -0.21 ≤ r ≤ -0.14) and sleep behaviours (p < 0.001, -0.32 ≤ r ≤ -0.23).

TablE 2.

Relationship between delta total score in mental wellbeing, mood and feeling, life satisfaction and the multidimension lifestyle behaviours (social participation, physical activity, diet and sleep)

| well being and feeling | Mental Mood | Life satisfaction | Need of psychosocial support | Social participation | Physical activity | Diet behaviour | Sleep behaviour | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental well being | 1 | |||||||

| Mood and feeling | -0.64*** | 1 | ||||||

| Life satisfaction | 0.51*** | -0.42*** | 1 | |||||

| Need of psychosocial | ||||||||

| support | -0.38*** | 0.45*** | -0.28*** | 1 | ||||

| Social participation | 0.28*** | -0.25*** | 0.23*** | -0.13*** | 1 | |||

| Physical activity | 0.15*** | -0.14*** | 0.10** | -0.15*** | 0.15*** | 1 | ||

| Diet behaviour | -0.21*** | 0.30*** | -0.14*** | 0.17*** | -0.06 | -0.18*** | 1 | |

| Sleep behaviour | -0.32*** | 0.41*** | -0.23*** | 0.26*** | -0.12*** | -0.17*** | 0.28*** | 1 |

**: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001

DISCUSSION

The present study reports preliminary results from our first 1047 participants (54% female) who responded to our ECLB-COVID19 multiple languages online survey over the first week. The findings showed that COVID-19 home confinement had a negative effect on mental wellbeing and emotional status with more individuals (i) perceiving low mental wellbeing (+12.89%), (ii) feeling dissatisfied (+16.5%), (iii) developing depression (+10%), and (iv) declaring a need of psychosocial support (+16.1%) compared to “before” the confinement period. During similar pandemic crises (2002–2004 SARS outbreak), previous research revealed several negative effects of quarantine measures on mental health and were associated with psychological and emotional strains such as depression and anxiety [27, 28]. These negative effects (i.e., increased levels of anxiety and depression) have also been reported in two recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses conducted by Purssell et al. [10] and Sharma et al. [11] assessing the impact of isolation precaution on quality of life. Similarly, in their recent review of the evidence, Brooks et al. [9] reported several psychological perturbations and emotional/ mood disturbances such as numbness, depression, irritability, stress, anger, nervousness, guilt, sadness, fear, vigilant handwashing, and avoidance of crowds in infected patients (SARS, MERS, H1N1 influenza, Ebola, and equine influenza) during quarantine periods. Similarly, results from Chinese studies indicate that the COVID-19 outbreak engendered anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances, and other psychological issues [7, 8]. This is related to the coupling of psychomental well-being to regular physical activity and to the related effects on immune function. [13, 29], With significant negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental wellbeing, life satisfaction, and depression scores of 1047 participants from different continents, the present findings support these suggestions from the literature and highlight the risk of mental disorders (e.g. low wellbeing, dissatisfaction and depression) during the home confinement period of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The resultant weakening of social contact with the disruption of normal lifestyles during the COVID-19 outbreaks have been suggested to generate stress throughout the population and thereby to engender lower mental and emotional wellbeing [3, 12]. To provide scientific evidence and deepen the understanding for these suggestions, the present multi-dimension survey also focused on the lifestyle behavioural changes during the COVID-19 outbreak. The negative psycho-emotional effect of COVID-19 home confinement was shown to be accompanied by a negative effect on the majority of assessed lifestyle behaviours with more (i) physical inactivity (+15.2), (ii) social isolation (+71.15%), (iii) unemployment (+6%), (iv) poorer sleep quality (+12.8%), and (v) unhealthy diet behaviours (+10%) compared to “before” the confinement period. Likewise, there was an increased number of people (+15%) who were using technology “all the time”.

These preliminary findings confirm our hypotheses related to the lifestyle behaviours. To better understand the behavioural changes recognized as risk factors of declined psychosocial wellbeing during the confinement period, a correlation analysis between the Δ change in total scores of all assessed variables from “before” to “during” confinement was performed. Changes in mental wellbeing, mood and feeling and life satisfaction were significantly correlated with changes in lifestyle behaviours, including social participation, physical activity, diet, and sleep. This suggests that low mental wellbeing, life dissatisfaction and high levels of depressive symptoms are related to social isolation, sedentary lifestyle, unhealthy diet behaviour and poor sleep quality. Therefore, in order to mitigate the negative physical and psychosocial effects of home confinement, implementation of a multi-dimension “need-oriented” intervention is warranted [13, 17–20]. This intervention should focus on enhancing social participation [18], healthy food [19, 20], sleep quality and promoting physical activity [19, 20]. In that regard, for instance the example from Germany could be mentioned: allowing people to do outdoor physical activity in large public gardens while respecting distancing and hygiene precautions. However, in more restrictive conditions where individuals were not allowed to leave their homes, people could perform physical activity in isolation, following certified health centre guidance [30]. Since participants demonstrated a higher acceptance rate (21.8% vs. 36.8%) toward the use of technological solutions, it seems interesting to foster social communication, and physical and mental wellbeing through Information and Communications Technology “ICT facilities” (e.g., social platform, gamification, mHealth, interactive coach, etc.). Indeed, such ICT-based solutions would facilitate the delivery of COVID19-related health services, as well as preventive and rehabilitation crisis-oriented intervention in the communities with a specific challenge to reach risk populations. In that regard, WHO and the national authorities have been encouraging the implementation, during the lockdown crisis, of a “technology-use” support system including factors such as reducing internet fees, increase internet access/speed, providing free ICT-based social inclusion platforms, promoting Gamification, Communication and interactive coaching technologies, tracking contacts and symptoms, to name a few.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first interdisciplinary international research project evaluating the psychosocial and behavioural changes “during” compared to “before” the COVID-19 home confinement period using a multiple-language online survey. Preliminary findings from this study offer some important insights into the effect of home confinement on mental wellbeing, emotional health status and the associated multidimension behavioural changes in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. However, given that data of the present study have been collected from a heterogeneous population with no criteria-based subsample analysis and the majority of respondents are ‘highly educated’, the present findings need to be interpreted with caution. Additionally, since the ECLB-COVID19 survey is still open and meanwhile also available in Dutch, Persian, Italian, Greek, Russian, Indian and Malayalam, future post-hoc studies in a large sample will be conducted to assess the interaction between the psychosocial strain evoked by COVID-19 and the geographical, demographic, cultural and health characteristics of the participants.

CONCLUSIONS

The preliminary results of the survey reveal a considerable burden for mental wellbeing combined with a tendency towards an unhealthy lifestyle during, compared to before, the confinement enforced by the COVID-19 pandemic. Particularly, social and physical inactivity, an unhealthy diet and poor sleep quality, triggered by the enforced home confinement, were associated with lower mental and emotional well-being (i.e., depressive and dissatisfied feelings). These multidimensional negative effects highlight the importance for stakeholders and policy makers to consider developing, implementing and publicising interdisciplinary interventions to mitigate the physical and psychosocial strain evoked in case of such pandemics. Promoting wellbeing by encouraging individuals to engage in indoor and/or outdoor physical activity, whilst conforming with distancing and hygiene recommendations, can be suggested as a preliminary measure with potential for physical and mental benefits [19, 20]. Moreover, since participants have demonstrated a higher acceptance of the use of technological solutions during the confinement period, fostering an Active and Healthy Confinement Lifestyle (AHCL) via an ICT-based approach can be considered.

A proposed psychosocial strain mitigation strategy from the ECLB-COVID19 consortium can be found in supplementary file 2.

Acknowledgements

We thank our consortium’s colleagues who provided insight and expertise that greatly assisted the research. We thank all colleagues and people who believed in this initiative and helped to distribute the anonymous survey worldwide. We are also immensely grateful to all participants who #StayHome and #BoostResearch by voluntarily taking the #ECLB-COVID19 survey.

This manuscript has been released as a pre-print at https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.05.04.20091017v1

Footnotes

CITATION: Ammar A, Trabelsi K, Brach M et al. Effects of home confinement on mental health and lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak: insights from the ECLB-COVID19 multicentre study. Biol Sport. 2021;38(1):9–21.

Competing interest statement

All authors declare no competing interest.

Details of funding

The author received no specific funding for this work.

SUPPLEMENTARY FILE 1: DESCRIPTIONS OF THE USED QUESTIONNAIRES

The Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale0 (SWEMWBS) [17]

The SWEMWBS is a short version of the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS). The WEMWBS was developed to enable the monitoring of mental wellbeing in the general population and in response to projects, programmes and policies focusing on mental wellbeing. The SWEMWBS uses seven of the WEMWBS’s 14 statements about thoughts and feelings, which relate more to functioning than feelings, suggesting an ability to detect clinically meaningful change [31, 32]. The seven statements are positively worded with five response categories from ‘none of the time (score 1)’ to ‘all of the time (score 5)’. The SWEMWBS has been recently validated for the general population and is scored by first summing the scores for each of the seven items, which are scored from 1 to 5 [21]. The total raw scores are then transformed into metric scores using the SWEMWBS conversion table. Total scores range from 7 to 35 with higher scores indicating higher positive mental wellbeing. Based on scores that were at least one standard deviation below and above the mean, respectively, categories for SWEMWBS were considered ‘low’ (7–19.3), ‘medium’ (20.0–27.0) and ‘high’ (28.1–35) mental wellbeing [21].

Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) [17]

The SMFQ is a short version of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ) developed in 1987 [33]. The SMFQ was developed in response to the need for a brief depression measure to reduce participant burden [34].

The SMFQ is suggested as a brief screening tool for depression based on thirteen of the MFQ’s 33 statements about how the subject has been feeling or acting recently [22]. The MFQ is scored by summing together the point values of responses for each item (“not true” = 0 points; “sometimes true” = 1 point; “true” = 2 points), with higher scores on the SMFQ suggesting more severe depressive symptoms. Scores on the SMFQ range from 0 to 26; a total score of 12 or higher may indicate the presence of depression [22].

Short Social Participation Questionnaire-Lockdowns (SSPQL) [18,22]

The present Short Social Participation Questionnaire-Lockdowns (SSPQ-L) is a crisis-oriented short modified questionnaire to assess social participation before and during a lockdown period. The SSPQL is based on the eighteen items of the Social Participation Questionnaire (SPQ). The original SPQ items aim to ask respondents to indicate how regularly they had undertaken each activity in the last 12 months. From questions 1 to 12, participant could choose one of the six response categories: “Never”, “Rarely”, “A few times a year”, “Monthly”, “A few times a month”, and “Once a week or more”. The remaining four items requested a binary “Yes” or “No” response regarding participation in community groups in the last 12 months [35]. Given that we are assessing social participation before and during the home confinement, which is a short period (days to months), we adapted the response categories and shortened the number of questionnaires by combining similar questions (e.g., Q1 and 2; Q2 and Q3; Q12 and Q14), while adding one more question about the use of phone calls for communication. Accordingly, the final SSPQ-L includes 14 items with five response categories (i.e., “Never” = 1 point; “Rarely” = 2 points; “Sometimes” = 3 points; “Often” = 4 points and “All times” = 5 points) for the 10 first items and “Yes” = 5 points / “No” = 1 point response categories for the four remaining items. Total scores of this questionnaire correspond to the sum of the scored points in the 14 questions. The total score for the SSPQ-L is from “14” to “70”, where “14” indicates that the participant has “never” being socially active; a score between “15” and “28” indicates that the participant has “rarely” been socially active, a score between “29” and “42” indicates that the participant is “sometimes” socially active, a score between “43” and “56” indicates that the participant is “often” socially active, and a score between “57” and “70” indicates that the participant is at “all times” socially active.

International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF) [19, 20, 24]

According to the official IPAQ-SF guidelines, data from the IPAQ-SF are summed within each item (i.e., vigorous intensity, moderate intensity, and walking) to estimate the total amount of time spent engaged in physical activity per week [23, 24]. In the present study, we report the total score reflecting the number of days per week of total physical activity (sum of performed vigorous, moderate and walking activity).

Short Diet Behaviour Questionnaire-Lockdowns [19]

The present Short Diet Behaviour Questionnaire-Lockdowns (SDBQ-L) is a crisis-oriented short questionnaire newly developed to assess diet behaviour before and during the lockdown period [19]. The SDBQ-L has 5 questions related to “unhealthy food”, “eating out of control”, “snacks between meals”, “binge alcohol”, and “number of meals/day” in parts referring to the Nutricalc questionnaire, Swiss Society of Nutrition (doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0143293.s003). Regarding the first question related to unhealthy food, an explanation was provided with the question as follows: “1. How likely are you to have an unhealthy diet/food? (high in calories from sugar or fat, colorants, salt and tropical oils; and low in fibre and vitamins (e.g., fried potato crisps/ chips, cakes, white sauces)”. The response choices and their designated scores were as follows: “Never” = 0; “Sometimes” = 1; “Most of the time” = 2; “Always” = 3. These choices and points were applied for the first four questions. The choices and the designated scores for the fifth question were as follows: “1–2” = 1; “3” = 0; “4” = 1; “5” = 2; “ > 5” = 3. Lower scores (0 to 1) in these five SDBQ-L questions indicate that participants are less likely to (i) have unhealthy food, (ii) eat out of control, (iii) have a high number of snacks between meals, (iv) drink alcohol out of control and (v) have a high number of meals. However, higher scores (2 to 3) on these questions indicate that participants are more likely to engage in these aforementioned unhealthy dietary habits [19].

The total score of this questionnaire corresponded to the sum of the scores in the five questions. The total score for the SDBQ-L is from “0” to “15”, where “0” designates no unhealthy dietary behaviours and “15” designates highly unhealthy dietary behaviours [19].

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [25]

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to assess subjective sleep quality over the previous month [25]. The PSQI has 19 questions collected into seven components: sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, the use of sleeping medications, and daytime dysfunction. Each component is weighted equally on a 0–3 scale. The total score for the PSQI ranges from “0” to “21”, where “0” designates no trouble and “21” designates severe problems in all areas. A PSQI total score > 5 is indicative of poor sleep [25].

The Short Technology-use Questionnaire-Lockdowns

The present Short Technology-use Questionnaire-Lockdowns (STuQL) is a crisis-oriented short questionnaire newly developed to assess technology-use behaviour before and during the lockdown period. The SDBQ-L has 3 questions related to technology-use behaviour for “social participation”, “diet” and “physical activity” purpose. The response choices and their designated point values are as follows: “Never” = 0 points; “Rarely” = 1 point; “Sometimes” = 2 points; “Often” = 3 points; “All times” = 4 points. The total score of this questionnaire corresponds to the sum of the scored points in the 3 questions. The total score for the SDBQ-L ranges from “0” to “12”, where “0” designates the absence of digital-use behaviour and 12 designates that the subject extensively uses digital solutions (i.e., a score of 1–3 indicates that the participant “rarely” uses technology, 4–6 indicates that the participant “sometimes” uses technology, 7–9 indicates that the participant “often” uses technology, and 10–12 indicates that the participant uses technology at “all times”).

Key question about the need of psychosocial support.

This is a new crisis-oriented question that has been added to the ECLB-COVID19 survey to directly monitor the psychosocial need of people during the home confinement period compared to before the crisis. Five response categories are available for this question: “Never”; “Rarely”; “Sometimes”; “Often” and “All times”.

SUPPLEMENTARY FILE 2: PSYCHOSOCIAL STRAIN MITIGATION STRATEGY

The present results suggest that the global health approach to mitigate the psychosocial strain during the COVID-19 outbreak would benefit from the following crisis-oriented interdisciplinary strategy: – 1st step: Implementing a national survey based on an expert-knowledge domain (e.g., ECLB-COVID19) to provide rigorous scientific identification of risk factors for psychosocial strain during the COVID-19 crisis and to understand the specific needs of the population.

– 2nd step: Developing a “Needs-oriented” intervention targeting the identified psychosocial and behavioural risk factors.

– 3rd step: Promoting physical activity and encouraging “technology-use behaviour” to facilitate the remote delivery of the developed crisis-oriented interventions.

– 4th step: Providing an affordable user-friendly ICT-based COMPANION for the COVID-19 lockdown which can (i) deliver the multi-dimension survey, (ii) identify the psychosocial and behavioural disorders and risk factors and (iii) deliver the “needs-oriented” recommendations.

This innovative solution would aim to foster an Active and Healthy Confinement Lifestyle (AHCL) during any pandemic period by mitigating the unwanted psychosocial strain triggered by the lockdown. Additionally, this smart recommendation/assistant system would help to minimize the unprecedented pressure on the helpline centre during the crisis period and via contact tracing and symptom identification technology would also help to foster the distancing strategy.

References

- 1.WHO. Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it”. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- 2.EDCD. Situation update worldwide, as of 19 April 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical-distribution-2019-ncov-cases. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- 3.WHO. Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- 4.Hossain MM, Sultana A, Purohit N. Mental health outcomes of quarantine and isolation for infection prevention: A systematic umbrella review of the global evidence. Available at SSRN 3561 265. 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Reuters investigates. COVID’s Other Causalities. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/health-coronavirus-usa-cost/Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- 6.The New York Times. A New Covid-19 Crisis: Domestic Abuse Rises Worldwide. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/world/coronavirus-domestic-violence.html. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- 7.Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatr 2020; 33, e100213. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, Ho RC. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020; 17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet 2020 ; 10227: 912–920. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Purssell E, Gould D, Chudleigh J. Impact of isolation on hospitalised patients who are infectious: systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ open 2020; 10(2). 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma A, Pillai DR, Lu M, Doolan C, Leal J, Kim J, Hollis A. Impact of isolation precautions on quality of life: a meta-analysis. J. Hosp. Infect. Available online 12 February 2020. 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gammon J, Hunt J. Source isolation and patient wellbeing in healthcare settings. Br J Nurs 2018; 27(2): 88–91. 10.12968/bjon.2018.27.2.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yousfi N, Bragazzi NL, Briki W, Zmijewski P, Chamari K. The COVID-19 pandemic: how to maintain a healthy immune system during the lockdown–a multidisciplinary approach with special focus on athletes. Biol Sport. 2020; 37(3):211–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The Mental Health Consequences of COVID-19 and Physical Distancing: The Need for Prevention and Early Intervention. JAMA Intern Med. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Usher K, Durkin J, Bhullar N. The COVID-19 pandemic and mental health impacts. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020. doi: 10.1111/inm.12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahase E. Covid-19: Mental health consequences of pandemic need urgent research, paper advises. BMJ 2020; Published 16 April 2020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ammar A, Mueller P, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, Bouaziz B, Brach M, et al. Emotional consequences of COVID-19 home confinement: The ECLB-COVID19 multicenter study. medRxiv 2020, doi: 10.1101/2020.05.05.20091058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, Bouaziz B, Bentlage Eet al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on social participation and life satisfaction: Preliminary results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online-survey. medRxiv 2020, doi: 10.1101/2020.05.05.20091066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, Bouaziz B, Bentlage, Eet al. on behalf of the ECLB-COVID19 Consortium. Effects of COVID-19 Home Confinement on Eating Behaviour and Physical Activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 International Online Survey. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, Bouaziz B, Bentlage, Eet al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on physical activity and eating behaviour Preliminary results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online-survey. medRxiv 2020, doi: 10.1101/2020.05.04.20072447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ng Fat L, Scholes S, Boniface S, Mindell J, Stewart-Brown S. Evaluating and establishing the national norms for mental well-being using the short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): findings from the Health Survey for England. Qual. Life Res. 2017; 26(5): 1129–1144. 10.1007/s11136-016-1454-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thabrew H, Stasiak K, Bavin LM, Frampton C, Merry S. Validation of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ) and Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) in New Zealand help-seeking adolescents. INT J METH PSYCH RES 2018; 27(3): 1–9. 10.1002/mpr.1610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Contry Reliability and Validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003; 35(8): 1381–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee PH, Macfarlane DJ, Lam TH, Stewart SM. Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short from (PAQ-SF): A systematic review. Int J Behov Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research. 1989; 28:193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen J. The effect size. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences 1988;77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra, R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2004; 10: 1206–1212. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.030703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reynolds DL, Garay JR, Deamond SL, Moran MK, Gold W, Styra R. Understanding, compliance and psychological impact of the SARS quarantine experience. Epidemiol. Infect. 2008; 136: 997–1007. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807009156 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alack K, Pilat C, Krüger K. Current knowledge and new challenges in exercise immunology. Dtsch Z Sportmed. 2019. 70: 250–260. Doi: 10.5960/dzsm.2019.391 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aspetar. Home Physical Activity Sessions. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.playlist?list=PLkeoBd4A272PoIszfLaejpaabR90_O31b.

- 31.Collins J, Gibson A, Parkin S, Parkinson R, Shave D, Dyer C. Counselling in the workplace: How time-limited counselling can effect change in well-being. Couns Psychother Res 2012; 12(2): 84–92. 10.1080/14733145.2011.638080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maheswaran H, Weich S, Powell J, Stewart-Brown S. Evaluating the responsiveness of the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS): Group and individual level analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2012; 10(1): 156. 10.1186/1477-7525-10-156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costello EJ, Angold A. Scales to assess child and adolescent depression: checklists, screens, and nets. J AM ACAD CHILD PSY 1988; 27(6): 726–737. 10.1097/00004583-198811000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, Pickles A, Winder F, Silver D. Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents 1995; 5: 237–249. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Densley K, Davidson S, Gunn J M. Evaluation of the Social Participation Questionnaire in adult patients with depressive symptoms using Rasch analysis. Qual. Life Res. 2013; 22(8): 1987–1997. 10.1007/s11136-013-0354-4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]