Abstract

Background:

Previous studies reported the recurrence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) among discharge patients. This study aimed to examine the characteristic of COVID-19 recurrence cases by performing a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods:

A systematic search was performed in PubMed and Embase and gray literature up to September 19, 2020. A random-effects model was applied to obtain the pooled prevalence of disease recurrence among recovered patients and the prevalence of subjects underlying comorbidity among recurrence cases. The other characteristics were calculated based on the summary data of individual studies.

Results:

A total of 41 studies were included in the final analysis, we have described the epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 recurrence cases. Of 3,644 patients recovering from COVID-19 and being discharged, an estimate of 15% (95% CI, 12% to 19%) patients was re-positive with SARS-CoV-2 during the follow-up. This proportion was 14% (95% CI, 11% to 17%) for China and 31% (95% CI, 26% to 37%) for Korea. Among recurrence cases, it was estimated 39% (95% CI, 31% to 48%) subjects underlying at least one comorbidity. The estimates for times from disease onset to admission, from admission to discharge, and from discharge to RNA positive conversion were 4.8, 16.4, and 10.4 days, respectively.

Conclusion:

This study summarized up-to-date evidence from case reports, case series, and observational studies for the characteristic of COVID-19 recurrence cases after discharge. It is recommended to pay attention to follow-up patients after discharge, even if they have been in discharge quarantine.

Introduction

Since December 2019, the world has been experiencing a public health crisis due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). As of September 01, 2020, about 26 million confirmed cases and 0.8 million deaths were reported from 213 countries and territories [1]. Several nationwide studies retrospectively investigated clinical features and the epidemiological characteristics of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 [2,3,4]. Particularly, aging and underlying chronic diseases were reported to much contribute to the severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [5,6]. However, patients with COVID-19 were generally less severe than SARS and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), with the fatality rate of 9.6%, 34.3%, and 6.6% for SARS, MERS, and COVID-19, respectively [7]. Recently, it has been reported that SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding duration could prolong up to 83 days [8,9]. In addition, the recurrence of SARS-CoV-2 after two consecutive negative detection of SARS-CoV-2 (sample collection interval of at least 1 day) has been observed among patients who had been discharged from health care units and received regular follow-up [8]. In general, recurrent cases can be defined as the relapse disease from a similar or same strain causing the primary infection and/or the reinfection disease from the distinct strain from the one causing the original infection [10,11]. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to examine the prevalence of either underlying conditions or comorbidities among recurrent COVID-19 cases, in addition to times from disease onset to hospital admission, from admission to hospital discharge, and from discharge to positive RNA conversion.

Methods

An electronic search of PubMed and Embase was conducted for English language studies published from the inception until September 19, 2020. The keywords for searching were as follows: “(COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2) AND (recurrence OR recurrences OR reinfection OR re-infection OR re-positive)”. Additionally, hand searching for related reports of the Centers for Disease Controls and bibliography of relevant studies was performed to obtain relevant information. For each study, the following information was extracted: first author’s name, country, study type, number of recurrence cases and discharged patients, the sample used for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), mean or median age (years), number of males, females, and cases underlying any chronic diseases (including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, liver or kidney disease, and cancer), times from disease onset to admission, from admission to discharge, and from discharge to positive conversion (days).

In this study, heterogeneity was quantified by the I2 statistics, in which I2 > 50% was defined as potential heterogeneity [12]. Given data are from different populations of various characteristics, a random-effects model was used to calculate the pooled effect size and its 95% confidence interval (CI) when the evidence from at least two individual studies was available [13]. All the statistical analyses were performed using STATA 14.0 software.

Results

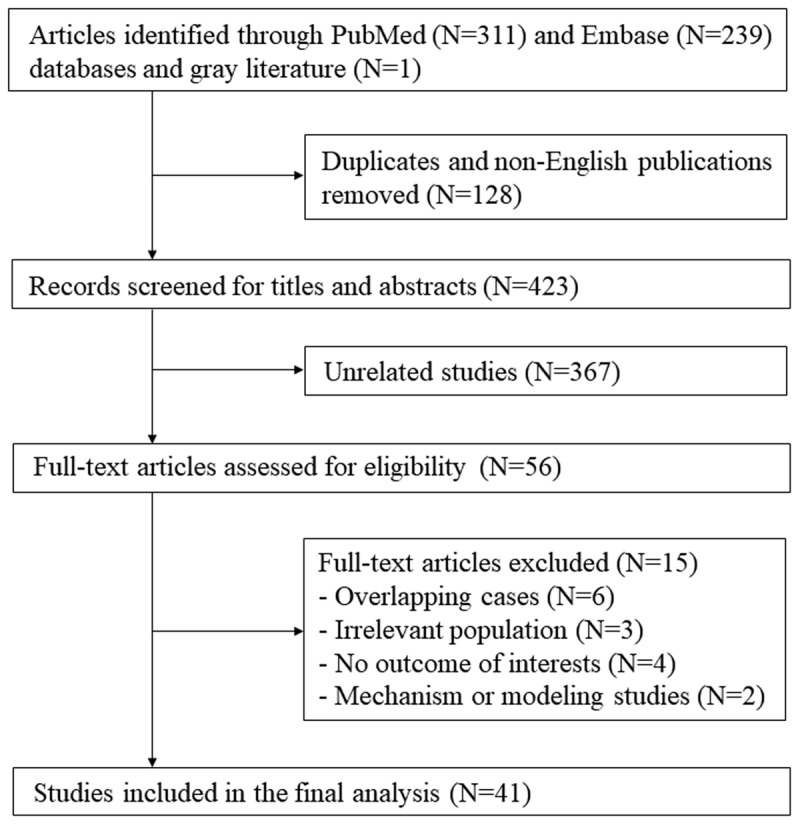

The study selection process is presented in Figure 1. Initial 550 records were retrieved through PubMed (N = 239) and Embase (N = 311) and additional one gray literature through hand searching was identified. Among records after removing duplicates and non-English publications (N = 128), 423 studies were potentially relevant through reviewing titles and abstracts. After reviewing full-text articles, 15 studies were excluded because they reported overlapping cases (N = 6) or irrelevant population (N = 3), there was no information for outcomes of interest (N = 4), and they were studies of mechanisms or modeling (N = 2). The remaining 41 studies were therefore eligible for the final analysis [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54].

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection.

A detailed description of extracted data of included studies is shown in Table 1. Thirty-eight studies reported 466 recurrence cases from China (N = 33, 435 cases), Korea (N = 1, 83 cases), Iran (N = 1, 1 case), Brunei (N = 1, 21 cases), Italy (N = 2, 3 cases), France (N = 1, 11 cases), Brazil (N = 1, 1 case), and US (N = 1, 1 case). The study design included case reports (N = 14), case series (N = 6), and observational studies (N = 21).

Table 1.

Summary of studies reporting recurrence of COVID-19 cases after discharge.

| STUDY | COUNTRY | STUDY TYPE | NO. OF RECURRENCE CASES | NO. OF DISCHARGED PATIENTS | SAMPLE FOR TESTING | AGE (YEARS) | MALE/FEMALE | NO. OF CASES UNDERLYING COMORBIDITY | TIMES FROM ONSET TO ADMISSION (DAYS) | TIMES FROM ADMISSION TO DISCHARGE (DAYS) | TIMES FROM DISCHARGE TO POSITIVE CONVERSION (DAYS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alonso FOM | Brazil | Case report | 1 | Respiratory swab | 26 | 1/0 | 34 | ||||

| An J | China | Observational | 38 | 242 | Nasal and anal swab | 32.8 | 16/22 | ||||

| Batisse D | France | Case series | 11 | Naso-pharyngeal swabs | 55 | 6/5 | 7 | ||||

| Bongiovanni M | Italy | Case series | 2 | Nasopharyngeal swab | 0/2 | 2 | |||||

| Cao H | China | Observational | 8 | 108 | Deep nasal cavity or throat swab | 54.4 | 3/5 | 0 | 16.3 | ||

| Chen D | China | Case report | 1 | Oropharyngeal swab | 46 | 1/0 | 8 | ||||

| Chen J | China | Observational | 81 | 1087 | Throat swab | 62 | 30/51 | 29 | 12 | 9 | |

| Chen Y | China | Observational | 4 | 17 | Oropharyngeal, nasopharyngeal, and anal swab | 32 | 2/2 | 18.25 | 11.25 | ||

| Duggan NM | US | Case report | 1 | 82 | 1/0 | 1 | 7 | 39 | 10 | ||

| Fu W | China | Case series | 3 | Nasopharyngeal swab | 48 | 1/2 | 12 | 9.3 | |||

| Gao G | China | Case report | 1 | 70 | 1/0 | 1 | 5 | 15 | 12 | ||

| Geling T | China | Case report | 1 | Pharyngeal swab | 24 | 1/0 | 0 | 10 | 8 | ||

| He F | China | Case report | 1 | Throat swab | 39 | 0/1 | 10 | 13 | 8 | ||

| Hu R | China | Observational | 11 | 69 | Nasopharyngeal swab | 27 | 7/4 | 3 | 10 | 14 | |

| Huang J | China | Observational | 69 | 414 | Nasopharyngeal and anal swab | 28/41 | 22 | 3 | 20 | 11 | |

| KCDC | Korea | Observational | 83 | 269 | 28/41 | 14.3 | |||||

| Li J | China | Case report | 1 | Nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal samples | 71 | 0/1 | 14 | ||||

| Li XJ | China | Case report | 1 | 41 | 1/0 | 19 | 9 | 19 | |||

| Li Y | China | Observational | 6 | 13 | Oral swabs, nasal swabs, sputum, blood, faeces, urine, vaginal secretions, and milk | 51.3 | 3/3 | 3 | 10.2 | ||

| Liang C | China | Observational | 11 | 22 | Throat swab | ||||||

| Liu T | China | Observational | 11 | 150 | Throat swab | 49 | 6/5 | ||||

| Loconsole D | Italy | Case report | 1 | Nasopharyngeal swab | 48 | 1/0 | 0 | 15 | 30 | ||

| Luo A | China | Case report | 1 | Throat swab | 58 | 0/1 | 7 | 15 | 22 | ||

| Mardani M | Iran | Case report | 1 | Nasopharyngeal swab | 64 | 0/1 | |||||

| Peng J | China | Case series | 7 | Throat swab | 4/3 | 16.7 | 10.1 | ||||

| Qiao XM | China | Observational | 1 | 15 | Nasopharyngeal and throat swab | 30 | 0/1 | 14 | 15 | ||

| Qu YM | China | Case report | 1 | Throat swab and sputum | 49 | 1/0 | 4 | ||||

| Tian M | China | Observational | 20 | 147 | Pharyngeal swabs | 37.15 | 11/9 | 7 | 2.5 | 18.65 | 17.25 |

| Wang P | China | Case report | 1 | Throat swab | 33 | 1/0 | 8 | 21 | 15 | ||

| Wang X | China | Observational | 8 | 131 | 48.75 | 4/4 | 0 | 11.375 | |||

| Wong J | Brunei | Observational | 21 | 106 | Nasopharyngeal swab | 43.1 | 12/9 | 17 | 13 | ||

| Xiao AT | China | Observational | 15 | 70 | Throat swab, deep nasal cavity swab | 64 | 9/6 | ||||

| Xing Y | China | Case series | 2 | Throat swab and stool tests | 1/1 | 6 | 15.5 | 6.5 | |||

| Ye G | China | Observational | 5 | 55 | Throat swab | 32.4 | 2/3 | 0 | 10.6 | ||

| Yuan B | China | Observational | 20 | 182 | Nasopharyngeal swab or anal swab | 39.9 | 7/13 | 6 | 5.1 | 20.8 | 9.45 |

| Yuan J | China | Observational | 25 | 172 | Cloacal swab and nasopharyngeal swab | 28 | 8/17 | 15.36 | 5.23 | ||

| Zhang B | China | Case series | 7 | Throat and rectal swab | 22.4 | 6/1 | 15.4 | 9.7 | |||

| Zheng KI | China | Observational | 3 | 20 | Salivary and fecal | 7 | |||||

| Zhou X | China | Case report | 1 | Oropharyngeal swab | 40 | 1/0 | 6 | 16 | 7 | ||

| Zhu H | China | Observational | 17 | 98 | Sputum and pharyngeal swab | 54 | 5/12 | 4 | |||

| Zou Y | China | Observational | 53 | 257 | Throat swabs | 62.19 | 23/30 | 29 | 4.6 | ||

The calculation of the epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 recurrence cases is presented in Table 2. Data for age were provided from 34 studies for 379 recurrence cases, with a mean age of 41.7 years. Among 542 recurrence cases from 39 studies, 233 cases were males, which accounted for 43%. Times from disease onset to admission, from admission to discharge, and from discharge to RNA positive conversion were available for 52, 276, 464 cases from 13, 22, and 31 studies, respectively. The estimates for times from disease onset to admission, from admission to discharge, and from discharge to RNA positive conversion were 4.8, 16.4, and 10.4 days, respectively.

Table 2.

Epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 recurrence cases.

| CHARACTERISTIC | NO. STUDIES | NO. OF RECURRENCE CASES | RESULT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 34 | 379 | 41.7 |

| Male (no., %) | 39 | 233 | 542 (43%) |

| Times from onset to admission (days) | 13 | 52 | 4.8 |

| Times from admission to discharge (days) | 22 | 276 | 16.4 |

| Times from discharge to positive conversion (days) | 31 | 464 | 10.4 |

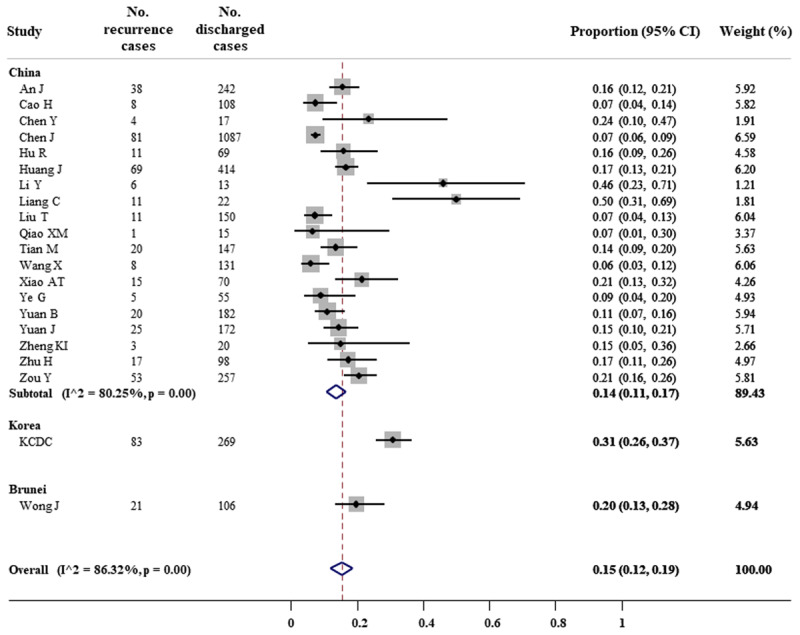

The prevalence of COVID-19 recurrence cases after discharge was calculated from data of 21 observational studies (Figure 2). Among 3,644 discharged patients, the RT-PCR test turned to be positive in 406 Chinese, 83 Korean, and 21 Bruneian subjects. Overall, the prevalence of recurrence cases was 15% (95% CI, 12% to 19%). Substantial heterogeneity among studies was observed, with I2 of 86.32%. In the subgroup analysis by population, the prevalence was reported to be 14% (95% CI, 11% to 17%) for China, 31% (95% CI, 26% to 37%) for Korea, and 20% (95% CI, 13% to 28%) for Brunei.

Figure 2.

Forest plot for meta-analysis of COVID-19 recurrence prevalence.

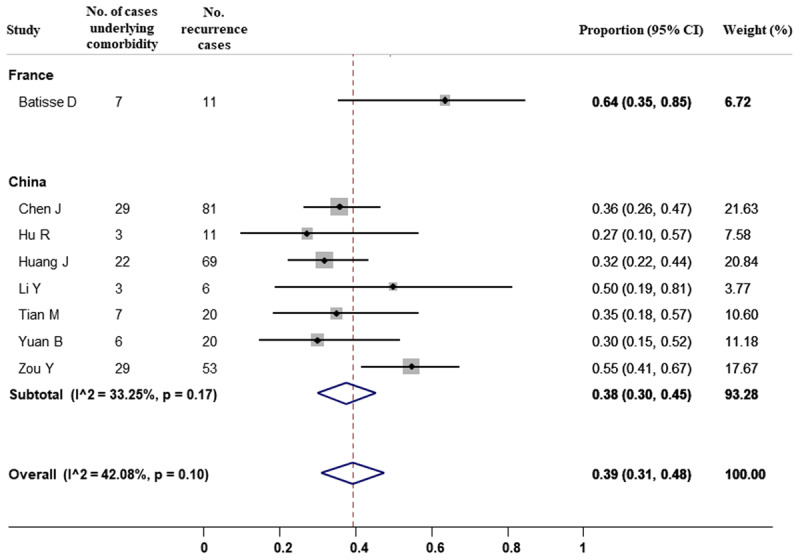

Furthermore, it was reported 106 subjects underlying comorbidity among a total of 271 recurrence cases, which accounted for 39% (95% CI, 31% to 48%) (Figure 3). There was no evidence of heterogeneity (I2 = 42.08%). Subgroup analysis showed the proportion of 64% (95% CI, 35% to 85%) for France cases and 38% (30% to 45%) for Chinese cases.

Figure 3.

Forest plot for meta-analysis of comorbidity among COVID-19 recurrence cases.

Discussion

Previous studies have reported the persistent detection of viral RNA by in a nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab, however, most of the cases were asymptomatic, the possibility of viral reinfection has been therefore proposed and investigated by many researchers [55]. In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 41 studies, we have described the epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 recurrence cases. Of 3,644 patients recovering from COVID-19 and being discharged, an estimate of 15% (95% CI, 12% to 19%) of patients re-infected with SARS-CoV-2 during the follow-up. This proportion was 14% (95% CI, 11% to 17%) for China, 31% (95% CI, 26% to 37%) for Korea, and 20% (95% CI, 13% to 28%) for Brunei. Among recurrence cases, it was estimated 39% (95% CI, 31% to 48%) subjects underlying at least one comorbidity.

According to the guidelines of the World Health Organization, a patient can be discharged from the hospital after two consecutive negative results in a clinically recovered patient at least 24 hours apart [56]. However, the discharge criteria for confirmed COVID-19 cases are additionally required according to different countries [57]. The determination of recurrence cases can be caused by false negatives, which ranged from 2% to 29% according to a meta-analysis of 957 hospitalized patients [58]. The reason for false negatives can be due to the source of specimens, sampling procedure, and the sensitivity and specificity of the test kit [8]. In a preprint study of 213 Chinese patients, a total of 205 throat swabs, 490 nasal swabs, and 142 sputum samples were collected, and the false-negative rates were reported of 40%, 27%, and 11% for the throat, nasal, and sputum samples, respectively [59]. Due to the lack of individual data, we were not able to examine the prevalence of recurrence cases in the subgroup analysis by types of specimens.

Furthermore, it may require considering prolonged SARS-CoV-2 shedding in asymptomatic or mild cases and recurrence of viral shedding [60], which related to the intensity of inflammation and immune response [61]. Data from 68 patients revealed a significantly longer duration of viral shedding from sputum specimens (34 days) than nasopharyngeal swabs (19 days) [62]. Consistent findings were reported in an asymptomatic case with viral detection positive in stool but negative in nasopharyngeal swab lasts for 42 days [63]. Similarly, the positive rate of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA test was shown to be highest for the sputum sample (100%), followed by nasal swab (75%), oral swab (40%), and stool specimen (38%) [64]. Nevertheless, although the RT-PCT results of discharge patients were possible to turn positive, it is necessary to distinguish between reactivation and reinfection cases [8].

Regarding the protective immunity, Alonso, et al. hypothesized the first mild viral infection might not strong enough to establish a detectable humoral response [65]. It was also possible for the absence of IgM and IgG antibodies, which were capable of connecting to the virus and preventing it from entering the host cell [66], in the acute and convalescent serum of the reinfected patients [67]. Although neutralizing antibodies and memory B and T cells again some common human coronaviruses (HCoV) such as HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43 were also suggested to confer cross-immunity against SARS-CoV-2 [68], a report based on data on 150 patients showed that the presence of serum IgM and IgG was not significantly associated with a lower rate of disease recurrence (OR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.27–3.16) [69].

Factors related to the recurrence of COVID-19 remain unclear because of inconsistent findings. Although disease severity may be associated with the worse immune response, An J, et al. reported the lower recurrence rate among subjects with severe or moderate disease at baseline than those with mild disease (odds ratio [OR] = 0.23, 95% CI = 0.10–0.53) [15]. However, the proportion in subjects with severe disease did not differ in those with moderate or mild disease (OR = 1.06, 95% CI = 0.57–1.96) [20]. Also, while subjects underlying diseases such as hypertension and diabetes are more likely to be susceptible with disease infection and severity [70], the recurrence proportion was not significantly different between those with and without any chronic diseases, in Chen, et al.’s study (OR = 0.71, 95% = 0.42–1.20 for hypertension and OR = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.42–1.75 for diabetes)and Huang et al.’s study (OR = 0.98, 95% = 0.52–1.87 for hypertension and OR = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.14–1.55 for diabetes) [20,28].

This study summarized up-to-date evidence from case reports, case series, and observational studies for the characteristic of COVID-19 recurrence cases after discharge. However, several limitations need to be mentioned. First, 80% of the included studies (33/41) with 78% recurrence cases (435/556) come from the Chinese population, which may reduce the availability to generalize the pooled estimates into other populations. Second, heterogeneity for the prevalence of recurrence cases was substantially presented among studies. The different characteristics, discharge criteria, and the test samples used among study populations included in this meta-analysis may have contributed to the heterogeneity. Third, all the estimates in the current study are based on aggregate data from published articles. Failure to obtain individual patient data may lead to bias due to the lack of full exploration and adjustment for patient characteristics [71]. Last, due to the lack of data, we were unable to assess the characteristic of recurrence individuals due to false negative or prolonged shedding.

In summary, an estimate of 15% of COVID-19 patients tested SARS-CoV2 positive after discharge. Among them, 39% of subjects were underlying comorbidity. It is recommended to pay attention to follow-up patients after discharge by closely monitoring their clinical characteristics such as illness severity, confusion, urea, respiratory rate, and blood pressure after two negative RT-PCR results of the discharge [72], even if they have been in the discharge quarantine for 14 days [73,74]. Further studies are needed to determine factors associated with positive RT-PCR in COVID-19 patients after discharge.

Data accesibility statement

Data for all the analyses are available in Table 1.

Competing interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Publisher’s Note

This paper underwent peer review using the Cross-Publisher COVID-19 Rapid Review Initiative.

Author contribution

TH designed the outline of the work, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Worldometer. COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

- 2.Sung HK, Kim JY, Heo J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of 3,060 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Korea, January–May 2020. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(30): e280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoneoka D, Kawashima T, Tanoue Y, et al. Early SNS-based monitoring system for the COVID-19 outbreak in Japan: A population-level observational study. J Epidemiol. 2020; 30(8): 362–70. DOI: 10.2188/jea.JE20200150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(18): 1708–20. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nandy K, Salunke A, Pathak SK, et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the impact of various comorbidities on serious events. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020; 14(5): 1017–25. DOI: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang SJ, Jung SI. Age-related morbidity and mortality among patients with COVID-19. Infect Chemother. 2020; 52(2): 154–64. DOI: 10.3947/ic.2020.52.2.154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toyoshima Y, Nemoto K, Matsumoto S, Nakamura Y, Kiyotani K. SARS-CoV-2 genomic variations associated with mortality rate of COVID-19. J Hum Genet. 2020. DOI: 10.1038/s10038-020-0808-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoang VT, Dao TL, Gautret P. Recurrence of positive SARS-CoV-2 in patients recovered from COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2020; 92(11): 2366–7. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.26056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li N, Wang X, Lv T. Prolonged SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding: Not a rare phenomenon. J Med Virol. 2020; 92(11): 2286–7. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.25952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambert ML, Hasker E, Van Deun A, Roberfroid D, Boelaert M, Van der Stuyft P. Recurrence in tuberculosis: Relapse or reinfection? Lancet Infect Dis. 2003; 3(5): 282–7. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00607-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McIvor A, Koornhof H, Kana BD. Relapse, re-infection and mixed infections in tuberculosis disease. Pathog Dis. 2017; 75(3). DOI: 10.1093/femspd/ftx020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003; 327(7414): 557–60. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: An update. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007; 28(2): 105–14. DOI: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alonso FOM, Sabino BD, Guimarães M, Varella RB. Recurrence of SARS-CoV-2 infection with a more severe case after mild COVID-19, reversion of RT-qPCR for positive and late antibody response: Case report. J Med Virol. 2021; 93(2): 655–6. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.26432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.An J, Liao X, Xiao T, et al. Clinical characteristics of the recovered COVID-19 patients with re-detectable positive RNA test. medRxiv. 2020. DOI: 10.1101/2020.03.26.20044222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Batisse D, Benech N, Botelho-Nevers E, et al. Clinical recurrences of COVID-19 symptoms after recovery: Viral relapse, reinfection or inflammatory rebound? J Infect. 2020; 81(5): 816–46. DOI: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bongiovanni M, Basile F. Re-infection by COVID-19: A real threat for the future management of pandemia? Infect Dis. 2020; 52(8): 581–2. DOI: 10.1080/23744235.2020.1769177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao H, Ruan L, Liu J, Liao W. The clinical characteristic of eight patients of COVID-19 with positive RT-PCR test after discharge. J Med Virol. 2020. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.26017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen D, Xu W, Lei Z, et al. Recurrence of positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA in COVID-19: A case report. Int J Infect Dis. 2020; 93: 297–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen J, Xu X, Hu J, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for recurrence of positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA: A retrospective cohort study from Wuhan, China. Aging. 2020; 12(17): 16675–89. DOI: 10.18632/aging.103795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y, Bai W, Liu B, et al. Re-evaluation of retested nucleic acid-positive cases in recovered COVID-19 patients: Report from a designated transfer hospital in Chongqing, China. J Infect Public Heal. 2020; 13(7): 932–4. DOI: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duggan NM, Ludy SM, Shannon BC, Reisner AT, Wilcox SR. A case report of possible novel coronavirus 2019 reinfection. Am J Emerg Med. 2021; 39: 256.e1–3. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.06.079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu W, Chen Q, Wang T. Letter to the Editor: Three cases of redetectable positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA in recovered COVID-19 patients with antibodies. J Med Virol. 2020. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.25968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao G, Zhu Z, Fan L, et al. Absent immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in a 3-month recurrence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) case. Infection. 2020; 1–5. DOI: 10.1007/s15010-020-01485-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geling T, Huaizheng G, Ying C, Hua H. Recurrent positive nucleic acid detection in a recovered COVID-19 patient: A case report and literature review. Respir Med Case Rep. 2020; 31: 101152. DOI: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2020.101152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He F, Luo Q, Lei M, et al. Successful recovery of recurrence of positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA in COVID-19 patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: A case report and review. Clin Rheumatol. 2020; 39(9): 2803–10. DOI: 10.1007/s10067-020-05230-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu R, Jiang Z, Gao H, et al. Recurrent positive reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction results for coronavirus disease 2019 in patients discharged from a hospital in China. JAMA Network Open. 2020; 3(5): e2010475. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang J, Zheng L, Li Z, et al. Recurrence of SARS-CoV-2 PCR positivity in COVID-19 patients: A single center experience and potential implications. medRxiv. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korea Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Findings from investigation and analysis of re-positive cases (19 May 2020). 2020. https://www.cdc.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=&bid=0030&act=view&list_no=367267&nPage=1.

- 30.Li J, Huang DQ, Zou B, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes. J Med Virol. 2021; 93(3): 1449–58. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.26424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li XJ, Zhang ZW, Zong ZY. A case of a readmitted patient who recovered from COVID-19 in Chengdu, China. Crit Care. 2020; 24(1). DOI: 10.1186/s13054-020-02877-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y, Hu Y, Yu Y, et al. Positive result of Sars-Cov-2 in faeces and sputum from discharged patients with COVID-19 in Yiwu, China. J Med Virol. 2020; 92(10): 1938–47. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.25905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang C, Cao J, Liu Z, et al. Positive RT-PCR test results after consecutively negative results in patients with COVID-19. Infect Dis. 2020; 52(7): 517–9. DOI: 10.1080/23744235.2020.1755447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu T, Wu S, Zeng G, et al. Recurrent positive SARS-CoV-2: Immune certificate may not be valid. J Med Virol. 2020; 92(11): 2384–6. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.26074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loconsole D, Passerini F, Palmieri VO, et al. Recurrence of COVID-19 after recovery: A case report from Italy. Infection. 2020; 48(6): 965–7. DOI: 10.1007/s15010-020-01444-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luo A. Positive SARS-Cov-2 test in a woman with COVID-19 at 22 days after hospital discharge: A case report. JTCMS. 2020; 7(4): 413–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtcms.2020.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mardani M, Nadji SA, Sarhangipor KA, Sharifi-Razavi A, Baziboroun M. COVID-19 infection recurrence presenting with meningoencephalitis. New Microbes New Infect. 2020; 37. DOI: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng J, Wang M, Zhang G, Lu E. Seven discharged patients turning positive again for SARS-CoV-2 on quantitative RT-PCR. Am J Infect Control. 2020; 48(6): 725–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qiao XM, Xu XF, Zi H, et al. Re-positive cases of nucleic acid tests in discharged patients with COVID-19: A follow-up study. Front Med. 2020; 7: 349. DOI: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qu YM, Kang EM, Cong HY. Positive result of Sars-Cov-2 in sputum from a cured patient with COVID-19. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020; 34: 101619. DOI: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tian M, Long Y, Hong Y, Zhang X, Zha Y. The treatment and follow-up of “recurrence” with discharged COVID-19 patients: Data from Guizhou, China. Environ Microbiol. 2020; 22(8): 3588–92. DOI: 10.1111/1462-2920.15156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang P. Recurrent presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in a 33-year-old man. J Med Virol. 2021; 93(2): 592–4. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.26334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X, Xu H, Jiang H, et al. The clinical features and outcomes of discharged coronavirus disease 2019 patients: A prospective cohort study. QJM. 2020; 113(9): 657–65. DOI: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong J, Koh WC, Momin RN, Alikhan MF, Fadillah N, Naing L. Probable causes and risk factors for positive SARS-CoV-2 test in recovered patients: Evidence from Brunei Darussalam. J Med Virol. 2020; 92(11): 2847–51. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.26199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiao AT, Tong YX, Zhang S. False negative of RT-PCR and prolonged nucleic acid conversion in COVID-19: Rather than recurrence. J Med Virol. 2020; 92(10): 1755–6. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.25855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xing Y, Mo P, Xiao Y, Zhao O, Zhang Y, Wang F. Post-discharge surveillance and positive virus detection in two medical staff recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), China, January to February 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020; 25(10): 2000191. DOI: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.10.2000191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ye G, Pan Z, Pan Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 reactivation. J Infect. 2020; 80(5): e14–e7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuan B, Liu HQ, Yang ZR, et al. Recurrence of positive SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in recovered COVID-19 patients during medical isolation observation. Sci Rep. 2020; 10(1): 11887. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-68782-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan J, Kou S, Liang Y, Zeng J, Pan Y, Liu L. PCR assays turned positive in 25 discharged COVID-19 patients. Clinical Infectious Diseases. An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang B, Liu S, Dong Y, et al. Positive rectal swabs in young patients recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Infect. 2020; 81(2): e49–e52. DOI: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng KI, Wang XB, Jin XH, et al. A case series of recurrent viral RNA positivity in recovered COVID-19 Chinese patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2020; 35(7): 2205–6. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-020-05822-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou X, Zhou J, Zhao J. Recurrent pneumonia in a patient with new coronavirus infection after discharge from hospital for insufficient antibody production: A case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2020; 20(1): 500. DOI: 10.1186/s12879-020-05231-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu H, Fu L, Jin Y, et al. Clinical features of COVID-19 convalescent patients with re-positive nucleic acid detection. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020; 34(7): e23392. DOI: 10.1002/jcla.23392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zou Y, Wang BR, Sun L, et al. The issue of recurrently positive patients who recovered from COVID-19 according to the current discharge criteria: Investigation of patients from multiple medical institutions in Wuhan, China. J Infect Dis. 2020. DOI: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bonifacio LP, Pereira APS, Araujo D, et al. Are SARS-CoV-2 reinfection and Covid-19 recurrence possible? A case report from Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020; 53: e20200619. DOI: 10.1590/0037-8682-0619-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nebehay S. WHO is investigating reports of recovered COVID patients testing positive again 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-who/who-is-investigating-reports-of-recovered-covid-patients-testing-positive-again-idUSKCN21T0F1#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20WHO’s%20guidelines,24%20hours%20apart%2C%20it%20added.

- 57.European Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. Discharge criteria for confirmed COVID-19 cases - When is it safe to discharge COVID-19 cases from the hospital or end home isolation? 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/COVID-19-Discharge-criteria.pdf.

- 58.Arevalo-Rodriguez I, Buitrago-Garcia D, Simancas-Racines D, et al. False-negative results of initial RT-PCR assays for COVID-19: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2020; 15(12): e0242958. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pome.0242958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woloshin S, Patel N, Kesselheim AS. False negative tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection - Challenges and implications. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383(6): e38. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp2015897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miyamae Y, Hayashi T, Yonezawa H, et al. Duration of viral shedding in asymptomatic or mild cases of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from a cruise ship: A single-hospital experience in Tokyo, Japan. Inter J Infect Dis. 2020; 97: 293–5. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou M, Yu FF, Tan L, et al. Clinical characteristics associated with long-term viral shedding in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Am J Transl Res. 2020; 12(10): 6954–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang K, Zhang X, Sun J, et al. Differences of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 shedding duration in sputum and nasopharyngeal swab specimens among adult inpatients with coronavirus disease 2019. Chest. 2020. DOI: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jiang X, Luo M, Zou Z, Wang X, Chen C, Qiu J. Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infected case with viral detection positive in stool but negative in nasopharyngeal samples lasts for 42 days. J Med Virol. 2020; 92(10): 1807–9. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.25941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yan-Xin C, Ming-Lin X, Xiao-Hui F, et al. Analysis of false negative results in throat swab nucleic acid test of severe acute resporatory syndrome coronavirus 2. Acad J Second Mil Med Univ. 2020; 41(6): 592–5. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alonso FOM, Sabino BD, Guimaraes M, Varella RB. Recurrence of SARS-CoV-2 infection with a more severe case after mild COVID-19, reversion of RT-qPCR for positive and late antibody response: Case report. J Med Virol. 2021; 93(2): 655–6. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.26432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oliveira DS, Medeiros NI, Gomes JAS. Immune response in COVID-19: What do we currently know? Microb Pathog. 2020; 148. DOI: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lin YC, Cheng CY, Chen CP, Cheng SH, Chang SY, Hsueh PR. A case of transient existence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the respiratory tract with the absence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody response. Int J Infect Dis. 2020; 96: 464–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chakrabarti SS, Kaur U, Singh A, et al. Of cross-immunity, herd immunity and country-specific plans: Experiences from COVID-19 in India. Aging Dis. 2020; 11(6): 1339–44. DOI: 10.14336/AD.2020.1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu T, Wu S, Zeng G, et al. Recurrent positive SARS-CoV-2: Immune certificate may not be valid. J Med Virol. 2020; 92(11): 2384–6. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.26074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ji W, Huh K, Kang M, et al. Effect of underlying comorbidities on the infection and severity of COVID-19 in Korea: A nationwide case-control study. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(25): e237. DOI: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lyman GH, Kuderer NM. The strengths and limitations of meta-analyses based on aggregate data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005; 5: 14. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.He S, Zhou K, Hu M, et al. Clinical characteristics of “re-positive” discharged COVID-19 pneumonia patients in Wuhan, China. Sci Rep. 2020; 10(1): 17365. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-74284-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hoang VM, Hoang HH, Khuong QL, La NQ, Tran TTH. Describing the pattern of the COVID-19 epidemic in Vietnam. Glob Health Action. 2020; 13(1). DOI: 10.1080/16549716.2020.1776526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang JF, Yan K, Ye HH, Lin J, Zheng JJ, Cai T. SARS-CoV-2 turned positive in a discharged patient with COVID-19 arouses concern regarding the present standards for discharge. Int J Infect Dis. 2020; 97: 212–4. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]