Abstract

Background

The antibiotic use rate (AUR) has emerged as a potential metric for neonatal antibiotic use, but reported center-level AURs are limited by differences in case mix. The objective of this study was to identify patient characteristics associated with AUR among a large cohort of preterm infants.

Methods

Retrospective observational study using the Optum Neonatal Database, including infants born from January 1, 2010 through November 30, 2016 with gestational age 23–34 weeks admitted to neonatal units across the United States. Exposures were patient-level characteristics including length of stay, gestational age, sex, race/ethnicity, bacterial sepsis, necrotizing enterocolitis, and survival status. The primary outcome was AUR, defined as days with ≥ 1 systemic antibiotic administered divided by length of stay. Descriptive statistics, univariable comparative analyses, and generalized linear models were utilized.

Results

Of 17 910 eligible infants, 17 836 infants (99.6%) from 1090 centers were included. Median gestation was 32.9 (interquartile range [IQR], 30.3–34) weeks. Median length of stay was 25 (IQR, 15–46) days and varied by gestation. Overall median AUR was 0.13 (IQR, 0–0.26) and decreased over time. Gestational age, sex, and race/ethnicity were independently associated with AUR (P < .01). AUR and gestational age had an unexpected inverse parabolic relationship, which persisted when only surviving infants without bacterial sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis were analyzed.

Conclusions

Neonatal AURs are influenced by patient-level characteristics besides infection and survival status, including gestational age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Neonatal antibiotic use metrics that account for patient-level characteristics as well as morbidity case mix may allow for more accurate comparisons and better inform neonatal antibiotic stewardship efforts.

Keywords: antibiotic stewardship, antibiotic use rate, benchmarking, neonatal, prematurity

Overuse of antibiotics accelerates the development of antibiotic resistance, which is one of the world’s most urgent public health problems [1]. Antibiotics are the most commonly used medications in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) [2–4]. The majority of infants admitted to NICUs are exposed to antibiotics and wide variation in antibiotic use exists across centers [5, 6]. Antibiotic expsoure is associated with selection for antibiotic-resistant organisms and among preterm infants is associated with subsequent development of necrotizing entercolitis (NEC), invasive fungal infection, late-onset sepsis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, retinopathy, and death [7–13].

Neonatal antibiotic stewardship involves a multidisciplinary comprehensive approach to optimize neonatal antibiotic use [14–17]. To date, interventions have concentrated on quality improvement and increasing accountability across centers. This has prompted consideration of how to best measure NICU antibiotic use, given that accurate measurement is key to benchmarking and improvement efforts. Antibiotic use rate (AUR) has emerged as a potentially useful metric [6, 18, 19]. AUR is technically a proportion, and has been defined as number of days with ≥ 1 antibiotic administered divided by either 100 patient-days (center-level) or length of stay (patient-level).

While comparison of AUR across centers can clearly identify variation and potential targets for stewardship efforts, understanding patient-level determinants of neonatal AURs is required for valid benchmarking. Thus far, reported center-level neonatal AURs have been stratified by center-level characteristics, but not by differences in patient case mix [18]. The majority of antibiotic use in NICUs is empiric treatment guided by risk of infection and patient presentation and is not necessarily inapproriate use [20]. Sicker infants are more likely to receive empiric therapy and, therefore, patient case mix must be taken into consideration for center-level comparisons of AUR. The lack of adjustment for patient characteristics, such as gestational age (GA), sex, and race/ethnicity, limits the application of AUR as a metric of neonatal antibiotic use [21]. The objective of this study was to identify patient characteristics associated with AUR among a large cohort of preterm infants across the United States.

METHODS

Data Source and Study Population

This retrospective observational study used data from the Optum Neonatal Database (Eden Prairie, Minnesota). Optum (formerly Alere) provides neonatal care management services for multiple private, government, and self-insured employer health plans throughout the United States. Such services include neonatal nurses and case managers that work with NICU teams to reduce length of stay, lower costs, and aid in the care of high-risk individuals [22]. The database includes predefined daily clinical, sociodemographic, and cost-related data abstracted multiple times per week by trained neonatal nurses. All data are collected prospectively using written protocols and are subject to routine validation and quality audits. Infants are included in the database if their health plan contracts with Optum to provide care management services and they are hospitalized in a level 2 or higher academic or community hospital-based NICU.

For the present study, we included infants born from November 1, 2010 to November 30, 2016 with GA between 23 0/7 and 34 6/7 weeks. Infants with missing antibiotic or length of stay data were excluded. Data collection took place in September 2018 and analysis took place from October 2018 to February 2019. The Institutional Review Board at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital certified the use of this de-identified dataset as non–human subjects research.

Study Definitions

Length of stay was defined as total days of initial NICU hospitalization. AUR was defined as days with ≥ 1 systemic antibiotic administered divided by length of stay and was individualized for each included infant. Bacterial sepsis was defined as a culture-confirmed bacterial bloodstream infection treated with antibiotic therapy. NEC was defined as Bell stage 2 or higher and was based on clinician diagnosis, ultimately entered into the database by the chart abstractor [23].

Statistical Analysis

AUR was reported for the overall cohort and by GA category, sex, race/ethnicity, bacterial sepsis/NEC, and survival status. The patient-level characteristics chosen for analysis were selected because they are present at birth, consist of objective and nonmodifiable data, and should be consistently retrievable across institutions. We chose the additional characteristics of bacterial sepsis or NEC (analyzed as a combined variable) and survival status because these are known drivers of antibiotic use. The number of antibiotic courses per infant, defined as at least 2 consecutive days of treatment > 1 day apart, and total duration (days) of antibiotic therapy were calculated. We then assessed for differences in AUR by GA among infants who survived without bacterial sepsis or NEC; in prior studies, infants who died, had sepsis, or had NEC were excluded when assessing differences in AUR by GA as these comorbidities are associated with distinct patterns of antibiotic use [6, 11, 18]. Rates of bacterial sepsis or NEC and mortality rates were also reported by GA category.

Descriptive statistics and univariable comparative analyses using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests or Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed as appropriate. The independent associations between AUR and the patient-level characteristics of interest were evaluated using multivariable generalized linear models that also included year and incorporated GA as a categorical variable. Given the large number of centers, each contributing few infants, a robust sandwich variance estimator for cluster-correlated data was used in the models to relax the assumption of independence among infants cared for in the same center. Variance inflation factors were analyzed to assess for multicollinearity between variables. P < .05 was considered statistically significant, and all reported P values are 2-sided. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata statistical software version 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline was used in the reporting of this study [24].

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Participants and Centers

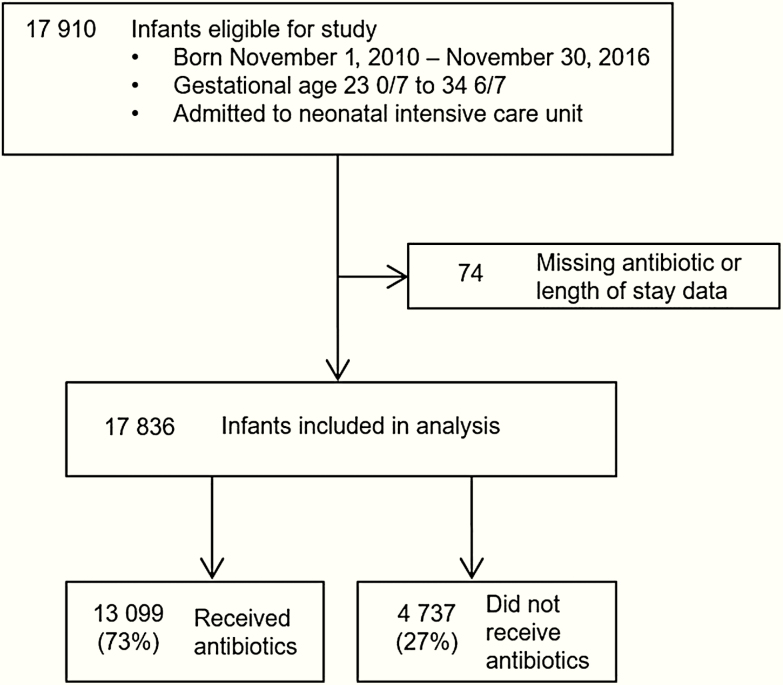

We identified 17 910 eligible infants, of which 17 836 (99.6%) from 1090 centers were included in the analysis (Figure 1). Characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. Female infants accounted for 47% (8361/17 836) of study participants. Median GA was 32.9 (interquartile range [IQR], 30.3–34) weeks and median birth weight was 1781 (IQR, 1320–2140) g. The majority (63%) of infants were delivered by cesarean section. Geographically, 4983 infants (27.9%) were from the Southern United States; 1365 (7.7%) were from the Midwest; 6522 (36.6%) were from the West; 4952 (27.8%) were from the East; and 14 (0.08%) were unknown. The range of infants contributed per center during the study period was 1–563, with a median of 63 (IQR, 21–155) infants.

Figure 1.

Study patient flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants (N = 17 836)

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Birthweight, g, median (IQR) | 1781 (1320–2140) |

| Gestational age, wk, median (IQR) | 32.9 (30.3–34) |

| Gestational age category, wk | |

| 23 | 200 (1.1) |

| 24 | 427 (2.4) |

| 25 | 494 (2.8) |

| 26 | 562 (3.2) |

| 27 | 643 (3.6) |

| 28 | 778 (4.4) |

| 29 | 885 (5.0) |

| 30 | 1186 (6.7) |

| 31 | 1575 (8.8) |

| 32 | 2363 (13.3) |

| 33 | 3444 (19.3) |

| 34 | 5279 (29.6) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 8361 (46.9) |

| Male | 9475 (53.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 6570 (36.8) |

| African American | 2517 (14.1) |

| Hispanic | 2834 (15.9) |

| Unknown/othera | 5915 (33.2) |

| Insurance type | |

| Commercial | 8329 (46.7) |

| Health maintenance organization | 3242 (18.2) |

| Medicaid | 6265 (35.1) |

| Cesarean delivery | 11 211 (62.9) |

| Multiple gestation | 5576 (31.3) |

| Intrauterine growth restriction | 833 (4.7) |

| Length of stay, d, median (IQR) | 25 (15–46) |

| Bacterial sepsis | 1355 (7.6) |

| Early-onset (≤ 3 d after birth)b | 174 (12.8) |

| Late-onset (> 3 d after birth)b | 1181 (87.2) |

| NEC | 367 (2.1) |

| Bacterial sepsis and/or NEC | 1552 (8.7) |

| Died | 528 (3.0) |

| Bacterial sepsis and/or NEC and/or died | 1912 (10.7) |

| Any antibiotics during admission | 13 099 (73.4) |

| Antibiotic use rate, median (IQR) | 0.13 (0–0.26) |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis.

aOf these, 4547 were “unknown” and 1368 were “other” (which includes Asian, biracial, East Indian, Native American).

bDenominator = 1355 infants (total infants with bacterial sepsis), based on age of first episode.

Antibiotic Use Rate Analyses

The majority (73% [13 099/17 836]) of infants received antibiotics during hospitalization. Infants who received antibiotics had lower median GA compared to those who did not (32.3 [IQR, 29.6–33.9] weeks vs 33.7 [IQR, 32.3–34.3] weeks; P < .001) and lower median birth weight (1720 [IQR, 1225–2110] g vs 1920 [IQR, 1550–2210] g; P < .001). Overall median AUR was 0.13 (IQR, 0–0.26) and decreased over time; AUR was highest in 2010 (0.15 [IQR, 0–0.27]) and lowest in 2016 (0.11 [IQR, 0–0.21]). Median number of antibiotic courses was 1 (range, 0–16), and median total duration of antibiotic days for infants who received any antibiotics was 4 (IQR, 3–8). Median length of stay was 25 (IQR, 15–46) days, and 1552 (8.7%) of infants had bacterial sepsis and/or NEC. Length of stay decreased with increasing GA (Figure 2A). In contrast, AUR differed significantly by GA with an inverse parabolic relationship (Figure 2B and Table 2). AUR also was significantly associated with infant sex and race/ethnicity (Table 2). AUR was significantly different between (i) infants with and without bacterial sepsis or NEC (P < .001), (ii) survivors and nonsurvivors (P < .001), and (iii) survivors without bacterial sepsis or NEC and nonsurvivors/infants with sepsis or NEC (P < .001) (Table 2). When we assessed for differences in AUR by GA among infants who survived without bacterial sepsis or NEC, the results were consistent: AUR differed significantly by GA category (P < .001), and the trend of AUR across the GA spectrum (Figure 2C) did not correlate with GA-specific infection or mortality rates. Bacterial sepsis/NEC rates (Supplementary Figure 1A) and mortality rates (Supplementary Figure 1B) correlated inversely with GA.

Figure 2.

Gestational age-specific length of stay (A), antibiotic use rate (B), and antibiotic use rate among surviving infants without sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis (C). The top and lower lines of the box plot represent the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively; the middle line represents the median; the upper whisker represents the upper adjacent value, and the lower whisker represents the lower adjacent value. Excludes outlier values.

Table 2.

Antibiotic Use Rate Univariable Analysis

| Variable | AUR, Median (IQR) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 0.13 (0–0.26) | |

| Gestational age category, wk | < .001 | |

| 23 | 0.21 (0.01–0.38) | |

| 24 | 0.19 (0.07–0.32) | |

| 25 | 0.15 (0.06–0.28) | |

| 26 | 0.14 (0.06–0.25) | |

| 27 | 0.11 (0.05–0.2) | |

| 28 | 0.10 (0.05–0.2) | |

| 29 | 0.10 (0.06–0.19) | |

| 30 | 0.10 (0.07–0.19) | |

| 31 | 0.11 (0.07–0.19) | |

| 32 | 0.14 (0–0.22) | |

| 33 | 0.16 (0–0.27) | |

| 34 | 0.17 (0–0.33) | |

| Sex | < .001 | |

| Female | 0.13 (0–0.25) | |

| Male | 0.14 (0–0.27) | |

| Race/ethnicity | < .001 | |

| White | 0.12 (0–0.24) | |

| African American | 0.15 (0.05–0.27) | |

| Hispanic | 0.15 (0.06–0.3) | |

| Asian/other/unknown | 0.13 (0–0.26) | |

| Bacterial sepsis and/or NEC | < .001 | |

| Yes | 0.29 (0.2–0.42) | |

| No | 0.12 (0–0.23) | |

| Died | < .001 | |

| Yes | 0.19 (0–0.46) | |

| No | 0.13 (0–0.25) | |

| Bacterial sepsis and/or NEC and/or died | < .001 | |

| Yes (at least 1) | 0.28 (0.17–0.42) | |

| No (none) | 0.12 (0–0.23) |

Abbreviations: AUR, antibiotic use rate; IQR, interquartile range; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis.

Multivariable Generalized Linear Models

The results of the multivariable generalized linear model analyses are shown in Table 3. In the overall cohort (model 1), compared to infants born at 23–27 weeks’ GA, infants born at 28–31 weeks’ GA had significantly lower AUR (adjusted coefficient, –0.31 [95% confidence interval {CI}, –.37 to –.26]; P < .001), whereas infants born at 32–34 weeks’ GA did not have statistically different AUR (adjusted coefficient, 0.05 [95% CI, –.01 to .10]; P = .08). Among survivors without sepsis or NEC (model 2), compared to infants born at 23–27 weeks’ GA, infants born at 28–31 weeks’ GA had significantly higher AUR (adjusted coefficient, 0.07 [95% CI, .002–.14]; P = .04), as did infants born at 32–34 weeks’ GA (adjusted coefficient, 0.59 [95% CI, .52–.65]; P < .001). Analysis of variance inflation factors confirmed there was no significant multicollinearity between variables for both models.

Table 3.

Antibiotic Use Rate Multivariable Generalized Linear Model Analysis

| Characteristic | Model 1a | Model 2a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | (95% CI) | P Value | Coefficient | (95% CI) | P Value | |

| GA categoryb, wk | ||||||

| 28–31 | –0.31 | (–.37 to –.26) | < .001 | 0.07 | (.002–.14) | .04 |

| 32–34 | 0.05 | (–.01 to .10) | .08 | 0.59 | (.52–.65) | < .001 |

| Male sexc | 0.10 | (.06–.14) | < .001 | 0.09 | (.05–.13) | < .001 |

| Race/ethnicityd | ||||||

| African American | 0.23 | (.17–.29) | < .001 | 0.22 | (.16–.29) | < .001 |

| Hispanic | 0.30 | (.24–.35) | < .001 | 0.26 | (.20–.32) | < .001 |

| Asian/other/unknown | 0.14 | (.09–.18) | < .001 | 0.15 | (.10–.20) | < .001 |

| Birth yeare | ||||||

| 2011 | –0.04 | (–.10 to .02) | .15 | –0.05 | (–.11 to .02) | .16 |

| 2012 | –0.10 | (–.16 to –.04) | .001 | –0.11 | (–.18 to –.05) | .001 |

| 2013 | –0.05 | (–.11 to .02) | .15 | –0.07 | (–.14 to –.002) | .06 |

| 2014 | –0.15 | (–.22 to –.07) | < .001 | –0.13 | (–2.0 to –.05) | .001 |

| 2015 | –0.15 | (–.23 to –.06) | .001 | –0.18 | (–.27 to –.09) | < .001 |

| 2016 | –0.27 | (–.37 to –.17) | < .001 | –0.30 | (–.40 to –.19) | < .001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GA, completed gestational age.

aModel 1 includes all infants (N = 17 836). Model 2 includes only surviving infants without bacterial sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis (n = 15 924).

bReference = GA 23–27 weeks.

cReference = Female sex.

dReference = White race/ethnicity.

eReference = 2010.

DISCUSSION

Quality improvement initiatives in neonatal intensive care have benefited from the formation of local, regional, and national networks that utilize variations in care and outcomes to provide benchmarking [25]. A key component of such benchmarking is risk adjustment, an approach that requires a nuanced understanding of the factors that impact specific outcomes. In this study, we sought to identify patient characteristics independently associated with AUR among preterm infants, and found that neonatal AURs differ significantly not only by infection/survival status, but also by GA, sex, and race/ethnicity. Given these findings, current center-level applications of AUR for interhospital comparison of neonatal antibiotic use are limited. Providers administer antibiotics to NICU infants for many reasons—empirically when they suspect infection, therapeutically when infection is confirmed, prophylactically for invasive procedures, and lastly, when they suspect infection without confirmation. There are 3 large areas where variation comes into play. Center-level variation represents variation in policies for choice of antibiotic, duration of empiric therapy, and prophylaxis, and provider-level variation reflects variation in how providers diagnose culture-negative infection (some more readily than others). These 2 reasons for variation must be addressed in the face of increasing antibiotic resistance and information about harm from antibiotic exposure. However, there is a third reason for variation, which is not just the difference in incidence of patients who have confirmed infection, but the risk probability for a patient for infection. It is the latter that drives repeated evaluations and empiric antibiotic courses. To not account for this risk profile is to ignore one of the primary drivers of antibiotic use variation that may in fact represent acceptable use. Neonatal antibiotic use metrics should account for patient characteristics as well as morbidity case mix to allow for more accurate interhospital comparisons and to better inform antibiotic stewardship efforts.

Our results show an expected inverse correlation between GA and length of stay, infection risk, and mortality. The relationship between GA and AUR, however, does not follow this trend. Extremely preterm infants (23–27 weeks) have high AUR, which may be expected given that these infants have a relatively high risk of infection and mortality, leading to a range of AUR where the maximum value approaches 100%. In contrast, infants born at 28–31 weeks have a lower median AUR, possibly related to lower infection risk, low mortality rates, and prolonged length of stay driven by care required to reach physiologic maturity. While this trend may be expected to continue with increasing gestation and falling risk for infection, AUR rises again for late and moderately preterm infants (32–34 weeks). We speculate that this observation may be attributed to empiric antibiotic use in these infants and shorter length of stay to achieve physiologic maturity, meaning that a greater proportion of hospital days may be spent in acute management of infection risk. An inconsistent relationship between AUR and GA persists even after adjusting for sex, race/ethnicity, and year. Among surviving infants without infection, more mature infants again have higher AUR compared to infants at the lowest GA, highlighting the potential impact of length of stay on this metric. The sensitivity of AUR to variations in outcomes of extreme prematurity may be especially important to account for in single centers where annual fluctuations in admission and survival rates may contribute disproportionately to center AUR. Institutional-level factors impacting discharge practices may impact length of stay, as well as AUR. Furthermore, the relationship between GA at birth and phase of care may be especially important in areas where neonatal care is highly regulated and regionalized.

We also found small but statistically significant differences in AUR by sex and race/ethnicity. The extent to which these differences are due to unmodifiable factors requires further investigation. Male sex is associated with less physiologic maturity per GA week and higher rates of morbidity and mortality among premature infants and thus conceivably may contribute to AUR [26, 27]. Race/ethnicity differences in outcomes among premature infants are observed in multiple studies [28, 29]. The observed differences may also reflect regional differences in racial mix in the United States, and therefore could reflect regional variation in care practice.

A strength of this analysis lies in the large sample and wide GA range of infants cared for in both academic and community hospitals from all regions of the country. Other reports have a narrower focus. A study from the Canadian Neonatal Network included only very low birth weight infants (birth weight < 1500 g) born during 2010–2014, and found that the AUR ranged from 0.25 to 0.29 with a decrease over time [11]. Moderately preterm infants, who make up a substantial portion of NICU admissions, were not included. Prior single-center studies from the United States addressed the relationship between AUR and neonatal outcomes or reductions in AUR after quality improvement initiatives [30–32]. Schulman et al took a statewide approach to compare AUR across Californian NICUs stratified by state-designated level of care [6]. They found that overall AUR varied 40-fold across 127 NICUs, ranging from 0.02 to 0.97, and was independent of proven infection, NEC, surgical volume, or mortality [6]. This study was eye-opening for neonatal care providers and led to energized interest in neonatal antibiotic stewardship efforts [33]. Investigators followed up with a 2018 report, demonstrating that overall AUR declined from 2013 to 2016 (21.9% decrease by 2016) and variation narrowed somewhat (by 5-fold to 10-fold), but still persisted without clear explanation [18]. While their prior report clearly demonstrated how AUR could be used to identify variation, the authors subsequently suggested that their updated findings could inform a framework for estimating AUR ranges that are consistent with infection burdens, proposing that for center-level AURs above the lowest quartile cut point of 0.14, no clear explanation for such use currently exists. NICUs with similar or the same acuity level designations may have varying degrees of patient acuity and distinct demographic populations [34]. For instance, 2 neonatal centers with the same statewide or national organization designation (ie, “level 3”) may care for very different patient populations with different baseline risks for empiric antibiotic prescription. Our results show that patient-level characteristics, including simple objective variables such as GA, sex, and race/ethnicity, are independently associated with neonatal AUR. GA and AUR do not have a linear relationship. AUR analyses stratified by center level and accounting for infection/mortality rates alone may lead to biased results. AUR is a powerful tool to assess for variation and to identify targets for antibiotic stewardship efforts. Based on our findings that AUR is influenced not just by infection and mortality rates, but also patient-level characteristics, the metric should not be used to set benchmarks across centers and/or inform health policy until the optimal approach to AUR risk adjustment can be determined. This is in line with recent evidence from the adult stewardship literature suggesting that that easily captured patient-level factors predictive of antibiotic use can be leveraged for improved comparisons across hospitals [35].

Antibiotic use is driven by both empiric and therapeutic use. Neonatal antibiotic stewardship efforts have focused on stopping antibiotics when cultures remain negative, as opposed to limiting empiric use [14, 36, 37]. For the foreseeable future, empiric antibiotic use will continue to make up the majority of neonatal AUR, and therefore accounting only for center-level characteristics and/or objective measures of infection is not sufficient to set benchmarks of antibiotic use as indicators of quality of care. Future research should focus on how to best measure antibiotic use among NICUs, accounting for patient case mix differences, to allow for fair comparisons across centers and to establish accurate trends over time. While other patient-level characteristics may drive empiric antibiotic use, namely indicators of severity of illness, in this study we chose to focus on objective variables that should be easily extracted from various data sources.

Our study does have limitations. The Optum database does not contain data regarding other types of infections and diagnoses that can attribute to AUR, including meningitis, urinary tract infections, skin and soft tissue infections, lower respiratory tract infections, renal malformations, spontaneous intestinal perforation, other surgical conditions, or perioperative prophylaxis. Detailed pharmacy and microbiological information were also not available, and the definition of bacterial sepsis relied on clinician distinction between a true sepsis episode and contamination or rule-out sepsis. We studied a small number of infants sampled from a large number of hospitals; as such, these data may not represent a true population-based dataset. Finally, our sampling method also meant a center-level analysis could not be performed and variation of AUR across centers, accounting for patient- and center-level characteristics, could not be determined.

CONCLUSIONS

Neonatal AURs differ significantly by GA, sex, race/ethnicity, and infection/survival status. There is an inconsistent relationship between AUR and GA, which does not correlate with the expected decrease in infection risk with higher GA. Neonatal antibiotic use metrics that account for patient-level characteristics as well as morbidity case mix may allow for more accurate comparisons and can better inform neonatal antibiotic stewardship efforts.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at the Journal of The Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society online (http://jpids.oxfordjournals.org). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Author contributions. D. D. F. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. This study was presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting (April 2019 in Baltimore, Maryland) and the Evidence Based Neonatology meeting (September 2019 in Newcastle, United Kingdom).

Disclaimer. The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscripts; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Financial support. D. D. F. was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant number T32HD060550) and by a Pilot Grant from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Office of Faculty Development. E. A. J. was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the NIH (grant number K23HL136843). S. M. was supported by the NICHD/NIH (grant number K23HD088753).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic/antimicrobial resistance. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/index.html. Accessed January 7, 2020.

- 2. Hsieh E, Hornik C, Clark R, et al. Medication use in the neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Perinatol 2014; 31:811–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grohskopf LA, Huskins WC, Sinkowitz-Cochran RL, et al. Pediatric Prevention Network . Use of antimicrobial agents in United States neonatal and pediatric intensive care patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2005; 24:766–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gulati R, Elabiad MT, Talati AJ, Dhanireddy R. Trends in medication use in very low-birth-weight infants in a level 3 NICU over 2 decades. Am J Perinatol 2016; 33:370–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Flannery DD, Ross RK, Mukhopadhyay S, et al. Temporal trends and center variation in early antibiotic use among premature infants. JAMA Netw Open 2018; 1:e180164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schulman J, Dimand RJ, Lee HC, et al. Neonatal intensive care unit antibiotic use. Pediatrics 2015; 135:826–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cotten CM, McDonald S, Stoll B, et al. National Institute for Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . The association of third-generation cephalosporin use and invasive candidiasis in extremely low birth-weight infants. Pediatrics 2006; 118:717–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cotten CM, Taylor S, Stoll B, et al. NICHD Neonatal Research Network . Prolonged duration of initial empirical antibiotic treatment is associated with increased rates of necrotizing enterocolitis and death for extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 2009; 123:58–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kuppala VS, Meinzen-Derr J, Morrow AL, Schibler KR. Prolonged initial empirical antibiotic treatment is associated with adverse outcomes in premature infants. J Pediatr 2011; 159:720–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Esaiassen E, Fjalstad JW, Juvet LK, et al. Antibiotic exposure in neonates and early adverse outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017; 72:1858–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ting JY, Synnes A, Roberts A, et al. Canadian Neonatal Network Investigators . Association between antibiotic use and neonatal mortality and morbidities in very low-birth-weight infants without culture-proven sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis. JAMA Pediatr 2016; 170:1181–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Puopolo KM, Mukhopadhyay S, Hansen NI, et al. Identification of extremely premature infants at low risk for early-onset sepsis. Pediatrics 2017; 140:e20170925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ting JY, Roberts A, Sherlock R, et al. Duration of initial empirical antibiotic therapy and outcomes in very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 2019; 143:e20182286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tolia VN, Desai S, Qin H, et al. Implementation of an automatic stop order and initial antibiotic exposure in very low birth weight infants. Am J Perinatol 2017; 34:105–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cantey JB, Patel SJ. Antimicrobial stewardship in the NICU. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2014; 28:247–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Warren S, Garcia M, Hankins C. Impact of neonatal early-onset sepsis calculator on antibiotic use within two tertiary healthcare centers. J Perinatol 2017; 37:394–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ting JY, Paquette V, Ng K, et al. Reduction of inappropriate antimicrobial prescriptions in a tertiary neonatal intensive care unit after antimicrobial stewardship care bundle implementation. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2019; 38:54–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schulman J, Profit J, Lee HC, et al. Variations in neonatal antibiotic use. Pediatrics 2018; 142:e20180115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dukhovny D, Buus-Frank ME, Edwards EM, et al. A collaborative multicenter QI initiative to improve antibiotic stewardship in newborns. Pediatrics 2019; 144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cantey JB, Wozniak PS, Sánchez PJ. Prospective surveillance of antibiotic use in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015; 34:267–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Flannery DD, Puopolo KM. Neonatal antibiotic use : how much is too much ? Pediatrics 2018; 142:e20181942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Optum. Neonatal and NICU support programs for employers. Available at: https://www.optum.com/solutions/employer/population-health/maternity-management/neonatal.html. Accessed October 29, 2019.

- 23. Kliegman RM, Walsh MC. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: pathogenesis, classification, and spectrum of illness. Curr Probl Pediatr 1987; 17:213–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147:573–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shah V, Warre R, Lee SK. Quality improvement initiatives in neonatal intensive care unit networks: achievements and challenges. Acad Pediatr 2013; 13:S75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tyson JE, Parikh NA, Langer J, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Intensive care for extreme prematurity—moving beyond gestational age. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:1672–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vu HD, Dickinson C, Kandasamy Y. Sex difference in mortality for premature and low birth weight neonates: a systematic review. Am J Perinatol 2018; 35:707–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. DeFranco EA, Hall ES, Muglia LJ. Racial disparity in previable birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016; 214:394.e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wallace ME, Mendola P, Kim SS, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in preterm perinatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017; 216:306.e1–e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cantey JB, Pyle AK, Wozniak PS, et al. Early antibiotic exposure and adverse outcomes in preterm, very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr 2018; 203:62–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bhat R, Custodio H, McCurley C, et al. Reducing antibiotic utilization rate in preterm infants: a quality improvement initiative. J Perinatol 2018; 38:421–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Astorga MC, Piscitello KJ, Menda N, et al. Antibiotic stewardship in the neonatal intensive care unit: effects of an automatic 48-hour antibiotic stop order on antibiotic use. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2019; 8:310–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Soll RF, Edwards WH. Antibiotic use in neonatal intensive care. Pediatrics 2015; 135:928–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Edwards EM, Horbar JD. Variation in use by NICU types in the United States. Pediatrics 2018; 142:e20180457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yu KC, Moisan E, Tartof SY, et al. Benchmarking inpatient antimicrobial use: a comparison of risk-adjusted observed-to-expected ratios. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67:1677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cantey JB, Wozniak PS, Pruszynski JE, Sánchez PJ. Reducing unnecessary antibiotic use in the neonatal intensive care unit (SCOUT): a prospective interrupted time-series study. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:1178–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mukhopadhyay S, Sengupta S, Puopolo KM. Challenges and opportunities for antibiotic stewardship among preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2019; 104:F327–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.