Abstract

Background

In 2010, the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) replaced 7-valent PCV (PCV7) for protection against invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD). This study used laboratory surveillance data to examine the effect of PCV13 on IPD before and after PCV13 introduction among children aged 6 weeks to <6 years and those aged ≥6 weeks.

Methods

Observational laboratory-based IPD surveillance data were compared for the periods May 2010–April 2018 and May 2008–April 2010 (the PCV7 period) using a database of Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) members with laboratory-confirmed IPD.

Results

Among children aged 6 weeks to 6 years, overall IPD incidence decreased from 11.57 per 100 000 during the PCV7 period to 4.09 per 100 000 after PCV13 introduction; PCV13-type IPD incidence decreased from 5.12 to 0.84 per 100 000. Non-PCV13−serotype IPD did not change significantly in this age group (PCV7 period, 1.71 per 100 000 and after PCV13, 2.52 per 100 000). Of cases occurring in this group, bacteremia was the most common clinical diagnosis. Across all ages, IPD decreased from 9.49 to 6.23 per 100 000 and PCV13-type IPD decreased from 4.67 to 1.89 per 100 000, changes being mostly due to decreases in serotypes 19A and 7F. IPD caused by non-PCV13 serotypes did not change (3.34 and 3.35 per 100 000). Overall, pneumococci isolated after PCV13 introduction had increased susceptibility to penicillin, cefotaxime, and ceftriaxone.

This prospective, laboratory-based surveillance study in Kaiser Permanente Northern California members examined annual IPD incidence before and after PCV13 introduction. In children aged 6 weeks to <6 years, IPD caused by PCV13 serotypes decreased significantly (84%) during the surveillance period.

Conclusions

IPD incidence decreased further in every age group after PCV13 introduction, suggesting both direct vaccination effects in the infant population and indirect effects in adults.

Clinical Trials Registration

Keywords: all ages, invasive pneumococcal disease, PCV13, Streptococcus pneumoniae

In this prospective, laboratory-based surveillance study of Kaiser Permanente Northern California members, we examined annual invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) incidence before and after 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) introduction. In children aged 6 weeks to <6 years, IPD caused by PCV13 serotypes decreased significantly (84%) during the surveillance period.

Invasive disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae results in substantial morbidity and mortality. In 2002, the World Health Organization estimated that 1.6 million deaths were attributable to pneumococcal disease [1]. Routine use of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) in the United States and elsewhere dramatically changed pediatric pneumococcal disease, with marked decreases in invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in the targeted population, resulting in a near-complete eradication of IPD caused by PCV7 serotypes [2]. PCV7 also decreased IPD in other age groups, including unvaccinated adults, suggesting an indirect effect of vaccinating children [2–4].

The emergence of additional pneumococcal serotypes as important causes of disease led to development of the 13-valent PCV (PCV13) to protect against these additional serotypes. PCV13 was licensed in the United States in 2010, with a recommendation to vaccinate all children aged 6 weeks to <6 years [5–7]. In 2013, PCV13 recommendations were expanded to include immunocompromised children aged 6 to <18 years [6, 8]. Licensed for adults aged ≥50 years in 2011 [9], the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended PCV13 for adults aged ≥19 years at higher risk for IPD in 2012 [10] and for all adults aged ≥65 years in 2014 [11].

Randomized, controlled efficacy trials of PCV13 were not feasible in children; thus, the presumed effectiveness of PCV13 in preventing IPD was based on immunologic noninferiority to PCV7 [12]. Similar to observations after PCV7 introduction, trends in IPD reduction have been observed since PCV13 implementation. Ongoing surveillance is needed to determine PCV13 effectiveness in preventing IPD caused by serotypes in PCV13 as well as to monitor pneumococcal disease and emerging serotype trends in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals.

Our aim in this study was to estimate IPD incidence in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) healthcare system during an 8-year surveillance period after PCV13 introduction, primarily among children aged 6 weeks to <6 years (direct effect) but also among all ages (indirect effect) compared with incidence during the baseline period when PCV7 was routinely used.

METHODS

Setting

This observational study was conducted within KPNC’s integrated healthcare delivery system. KPNC essentially provides all healthcare for approximately 4 million members at its 22 hospitals and 54 medical centers. KPNC maintains databases of all outpatient, emergency, and inpatient visits, as well as all radiology, pharmacy, laboratory, immunization, and demographic data for all members. All bacterial culture testing was performed in KPNC’s centralized regional laboratory.

Study Population and Period

We conducted active laboratory-based surveillance for IPD among the study population of all KPNC members aged ≥6 weeks (earliest age recommended for a first dose of PCV) with culture-confirmed IPD. There were no exclusion criteria. Throughout the study, KPNC followed ACIP recommendations regarding PCV13 use in children and adults. The study period for IPD surveillance was May 2010 to April 2018; the 2-year baseline period before PCV13 introduction was May 2008 to April 2010.

IPD Definition and Specimen Processing

We defined IPD as recovery of S. pneumoniae from the following normally sterile sites: blood; cerebrospinal, pleural, peritoneal, pericardial, or joint fluid; surgical aspirate; or bone. Specimens were obtained per standard clinical care at the discretion of treating KPNC physicians. The KPNC laboratory performed specimen culture, identification, and S. pneumoniae isolation according to standard microbiology techniques. All S. pneumoniae isolates were sent to Boston Medical Center for serotyping using the Quellung reaction.

Objectives

The primary objective was to estimate the annual incidence of IPD in children aged 6 weeks to <6 years during each year after PCV13 introduction. Secondary objectives, which applied to all ages, included estimating overall and vaccine-type annual IPD incidence after PCV13 introduction, comparing IPD incidence before and after PCV13, identifying pneumococcal isolate antibiotic susceptibility patterns, and describing clinical diagnoses, underlying medical condition(s), and clinical outcomes in IPD cases.

Clinical Information

The following demographic and baseline characteristics for all IPD cases were obtained: age at IPD diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, underlying conditions, pneumococcal and influenza vaccination history, clinical IPD diagnosis (eg, bacteremia, pneumonia, meningitis), and clinical outcomes (eg, discharge to home). Preselected underlying conditions were collected from KPNC disease registries (eg, asthma registry, cancer registry).

Clinical IPD diagnosis was based on the diagnosis chosen by the provider at the time of care. We did not confirm clinical diagnoses. Primary diagnoses from the inpatient setting were prioritized, followed by emergency and then outpatient. Diagnoses were categorized into prespecified categories, with a diagnosis of “Other” chart-reviewed for reclassification.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility

KPNC’s central laboratory conducted antimicrobial susceptibility testing of S. pneumoniae isolates according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines [13]. Each IPD isolate was classified as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant for each panel of antibiotics evaluated. Susceptibility was expressed as a minimum inhibitory concentration determined by Etest (BioMérieux, Durham, NC).

Statistical Analyses

The primary endpoint was the annual incidence rate (IR) of IPD in children aged 6 weeks to <6 years, which was calculated as the number of cases reported in a given year divided by the number of persons at risk (estimated as the number of KPNC members aged 6 weeks to 6 years at the midpoint of the year), multiplied by 105. We assessed the annual IR for each of the 8 years of surveillance, for the average across the 8 years, and for the baseline period before PCV13 introduction. We calculated annual IRs for the secondary objective (which included all ages) identically, using age-appropriate KPNC members to estimate the number at risk.

To compare IPD incidence following exclusive use of PCV13 (May 2011 to April 2018) to the pre-introduction baseline period when only PCV7 was used (May 2008 to April 2010), incidence rate ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated overall and by vaccine-type and individual serotypes. We considered the estimated RR as statistically significant if the 95% CI excluded 1.0. The first year after PCV13 licensure (May 2010 to April 2011) was not included in the comparison to allow clinics to switch from using PCV7 to PCV13.

We used Statistical Analysis Systems (SAS Institute, Inc.) version 9.1 or higher for data analyses.

RESULTS

From 2008 through 2018, among the entire study population aged ≥6 weeks, there were 2721 IPD cases, with most (72%) occurring in those aged ≥50 years (Table 1). Of those, there were 159 IPD cases in children aged 6 weeks to 6 years, most (59%) of whom were aged between 2 and 6 years. The fraction of IPD cases in individuals aged ≥6 weeks was disproportionately lower in Asian and Hispanic individuals and disproportionately higher in black and white individuals relative to the racial distribution within KPNC. Since the 6 weeks to 6 years group targeted for vaccination was the primary analysis population, we report those analyses first, followed by the total population aged ≥6 weeks.

Table 1.

Demography of Individuals With Invasive Pneumococcal Disease Aged 6 Weeks to <6 Years and All Ages (≥6 Weeks) at Kaiser Permanente Northern California

| Characteristic | IPD Cases 6 wk to <6 y, na (%) (Nb = 159) | IPD Cases All Ages (≥6 wk), na (%) (Nb = 2721) | Kaiser Permanente Northern California Population All ages (≥6 wk), %c (Nd = 3 828 462) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 102 (64.2) | 1386 (50.9) | 48.5 |

| Female | 57 (35.8) | 1335 (49.1) | 51.5 |

| Agee | |||

| 6 wk to <6 y | … | 159 (5.8) | 7.0 |

| 6 wk to <2 y | 66 (41.5) | … | … |

| 6 wk to <1 y | 24 (15.1) | … | … |

| 1 y to <2 y | 42 (26.4) | … | … |

| 2 y to <6 y | 93 (58.5) | … | … |

| 6 y to <18 y | … | 90 (3.3) | 15.2 |

| 18 y to <50 y | … | 521 (19.1) | 44.3 |

| 50 y to <65 y | … | 776 (28.5) | 20.0 |

| 65 y to <80 y | … | 690 (25.4) | 10.2 |

| ≥80 y | … | 485 (17.8) | 3.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 36 (22.6) | 277 (10.2) | 18.2 |

| Black | 24 (15.1) | 352 (12.9) | 7.1 |

| Hispanic | 27 (17.0) | 353 (13.0) | 18.6 |

| Multiracial | 5 (3.1) | 145 (5.3) | 4.8 |

| Native American | 1 (0.6) | 14 (0.5) | 0.5 |

| Pacific Islander | 5 (3.1) | 46 (1.7) | 0.6 |

| Unknown/other | 9 (5.7) | 38 (1.4) | 2.7 |

| White | 52 (32.7) | 1496 (55.0) | 47.5 |

All IPD cases, regardless of membership and whether serotyped, were included. Membership refers to patients who were members of Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) for at least 2 months in each year. An IPD case was a unique case separated by a period of 14 days. For individuals ≥6 weeks of age, average age across the study period was used.

Abbreviation: IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease.

aNumber of IPD cases in specified category.

bNumber of IPD cases in specified group.

cPercent of KPNC population.

dAverage number of KPNC population across the study period.

eBased on age at time of specimen collection.

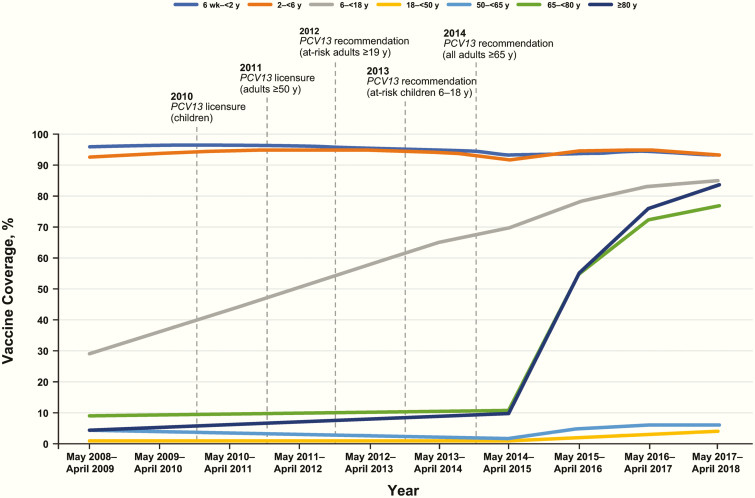

During the study period, the percentage of children aged 6 weeks to 6 years who received ≥1 dose of PCV was high (94.3%), while PCV13 coverage among adults aged ≥18 years was low (2.3%–25.5%). Coverage for adults aged ≥65 years increased substantially after the 2014 ACIP recommendation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PCV coverage by age and year at Kaiser Permanente Northern California (includes 1 or more doses of either PCV7 or PCV13 during the study period). PCV use included only PCV7 from May 2008 through April 2010, either PCV7 or PCV13 during the introductory period (May 2010–April 2011), and only PCV13 thereafter (May 2011–April 2018). Vertical dashed lines indicate dates for PCV13 licensure and recommendations. Note that the increase in coverage among individuals aged 6 to <18 years reflects the increase in the population of that age, most of whom received PCV7 in the past as part of routine care, and may not reflect higher PCV13 coverage with time among this age group. Abbreviation: PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

IPD Incidence

Children Aged 6 Weeks to 6 Years

Overall IPD incidence among children aged 6 weeks to 6 years decreased by 65% from 11.57 cases per 100 000 over the PCV7 period (May 2008–April 2010) to 4.09 cases per 100 000 over the PCV13 period (May 2011–April 2018; Table 2). IPD caused by PCV13 serotypes decreased significantly by 84% between the PCV7 and PCV13 periods, from 5.12 to 0.84 cases per 100 000 (RR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.09–0.30). Non-PCV13 serotypes increased from 1.71 to 2.52 cases per 100 000; this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Incidence Rates of Invasive Pneumococcal Disease by Serotype Category—Before and After Introduction of 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine at Kaiser Permanente Northern California

| Incidencea (per 100 000) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCV7 Period | PCV13 Period | Rate Ratio (PCV13 Period/PCV7 Period) | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Serotype Category | May 2008–April 2010 | May 2011–April 2018 | ||

| ≥6 wk to <6 y | ||||

| All IPD | 11.57 | 4.09 | 0.35 | 0.25–0.50 |

| PCV13b | 5.12 | 0.84 | 0.16 | 0.09–0.30 |

| PCV7c | N/A | 0.10 | N/A | 0.08–N/A |

| Cross-reactived | 0.19 | 0.79 | 4.15 | 0.74–88.17 |

| PPSV23e | 5.50 | 1.89 | 0.34 | 0.21–0.56 |

| Non-PCV13f | 1.71 | 2.52 | 1.47 | 0.75–3.19 |

| NAS | 4.74 | 0.73 | 0.15 | 0.08–0.30 |

| ≥6 wk | ||||

| All IPD | 9.49 | 6.23 | 0.66 | 0.60–0.72 |

| PCV13b | 4.67 | 1.89 | 0.40 | 0.35–0.46 |

| PCV7c | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.94 | 0.56–1.66 |

| Cross-reactived | 0.96 | 1.01 | 1.06 | 0.81–1.39 |

| PPSV23e | 5.99 | 3.16 | 0.53 | 0.47–0.59 |

| Non-PCV13f | 3.34 | 3.35 | 1.00 | 0.87–1.16 |

| NAS | 1.48 | 0.99 | 0.67 | 0.54–0.85 |

All IPD cases, regardless of membership and whether serotyped, were included. Membership refers to patients who were members of Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) for at least 2 months in each year. An IPD case was a unique case separated by a period of 14 days. Year of PCV13 introduction at KPNC (May 2010–April 2011) not shown.

Abbreviations: IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; N/A, not applicable; NAS, not available for serotyping or untypeable; PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (7 or 13 valent); PPSV23, pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (23 valent).

aAnnual incidence of IPD = (IPD cases)/(membership/100 000).

bPCV13 serotypes include 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F, 23F.

cPCV7 serotypes include 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, 23F.

dCross-reactive serotypes include 6C, 7A, 7C, 9L, 9N, 19C, 23A, 23B.

ePPSV23 serotypes include 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 8, 9N, 9V, 10A, 11A, 12F, 14, 15B, 17F, 18C, 19A, 19F, 20, 22F, 23F, 33F.

fAll serotypes not included in PCV13.

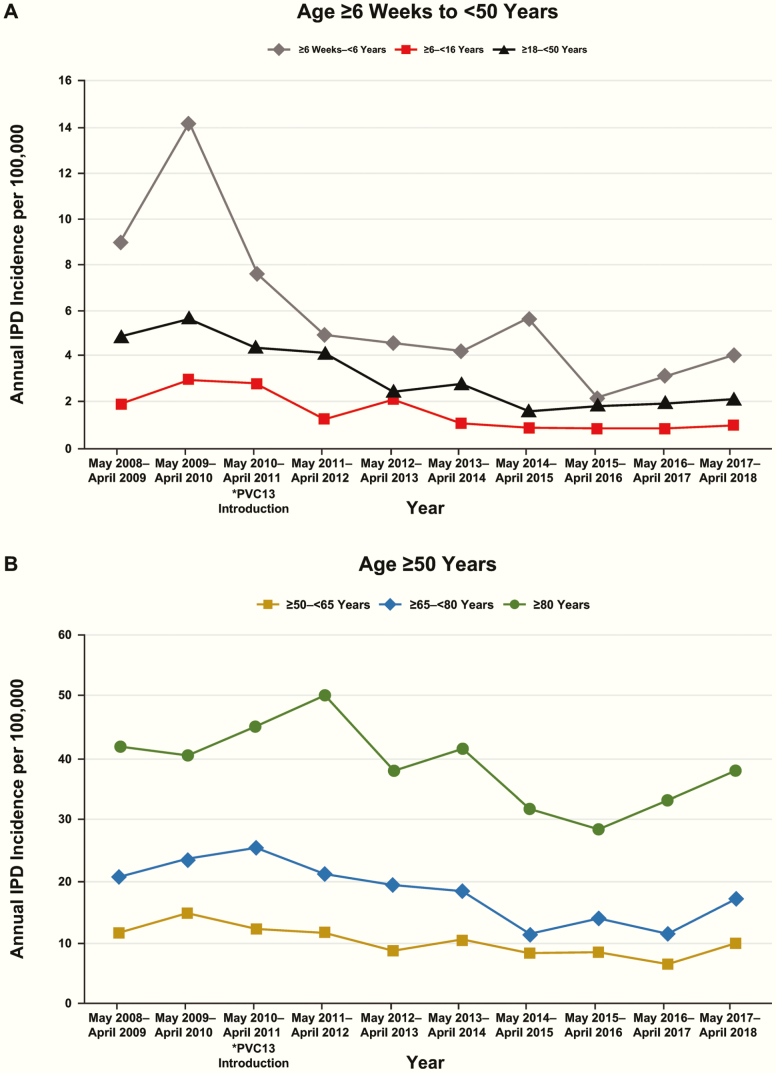

IPD annual incidence among children aged 6 weeks to 6 years decreased from 9.01 cases per 100 000 in 2008–2009 to 4.07 per 100 000 in 2017–2018 (Figure 2A). IPD caused by PCV13 serotypes decreased from 4.51 cases per 100 000 to 1.02 in the same period (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Annual IPD incidence per 100 000 by year and age group at Kaiser Permanente Northern California. (A) Age 6 weeks to <50 years and (B) age ≥50 years. *Significant difference in IPD incidence begins with PCV13 introduction in May 2010 for children aged ≥6 weeks to <6 years. Abbreviations: IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

Table 3.

Incidence Rates of Invasive Pneumococcal Disease Cases Caused by 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV13) Serotypes by Age - by Year and Before and After Introduction of PCV13 at Kaiser Permanente Northern California

| Age Group | Annual Incidencea (per 100 000) | Incidencea (per 100 000) Before and After Introduction of PCV13 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 2008 to April 2009 | May 2009 to April 2010 | May 2010b to April 2011 | May 2011 to April 2012 | May 2012 to April 2013 | May 2013 to April 2014 | May 2014 to April 2015 | May 2015 to April 2016 | May 2016 to April 2017 | May 2017 to April 2018 | PCV7 Period | PCV13 Period | Rate Ratio (PCV13 Period/ PCV7 Period) | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| May 2008 to April 2010 | May 2011 to April 2018 | |||||||||||||

| 6 wk to <6 y | 4.51 | 5.75 | 4.19 | 2.28 | 0.77 | 0.38 | 1.13 | – | 0.35 | 1.02 | 5.12 | 0.84 | 0.16 | 0.09–0.30 |

| 6 to <18 y | 0.86 | 1.94 | 1.75 | 0.35 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.35 | – | 0.17 | 0.49 | 1.4 | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.16–0.63 |

| 18 to <50 y | 3.13 | 3.73 | 2.7 | 2.27 | 1.42 | 1.11 | 0.63 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 0.68 | 3.43 | 0.94 | 0.27 | 0.21–0.36 |

| 50 to <65 y | 5.63 | 6.88 | 5.89 | 6.23 | 4.28 | 3.33 | 2.27 | 1.70 | 1.87 | 2.69 | 6.26 | 3.09 | 0.49 | 0.38–0.64 |

| 65 to <80 y | 9.36 | 8.77 | 11.82 | 8.63 | 4.03 | 5.82 | 2.14 | 3.82 | 3.41 | 3.46 | 9.06 | 4.32 | 0.48 | 0.35–0.66 |

| ≥80 y | 13.0 | 17.98 | 19.99 | 10.9 | 11.32 | 10.18 | 7.55 | 4.37 | 7.07 | 6.90 | 15.53 | 8.20 | 0.53 | 0.35–0.80 |

All invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) cases, regardless of membership and whether serotyped, were included. Membership refers to patients who were members of Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) for at least 2 months in each year. An IPD case was a unique case separated by a period of 14 days.

Abbreviation: PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (7 or 13 valent).

aIncidence of IPD = (IPD cases)/(membership/100 000).

bPCV13 was introduced for KPNC use in May 2010. Year of introduction (2010–2011) is not shown in before-and-after view.

All Cases, ≥6 Weeks of Age

Among all ages, IPD caused by PCV13 serotypes decreased after PCV13 introduction from 4.67 cases per 100 000 during 2008−2010 to 1.89 per 100 000 during 2011–2018 (Table 2). Non-PCV13−serotype IPD was unchanged during the same periods (3.34−3.35 cases per 100 000), and overall IPD incidence decreased 34%, from 9.49 to 6.23 cases per 100 000. The most substantial decrease in PCV13-serotype IPD, when comparing 2011–2018 with the 2008–2010 period, occurred among children aged 6 weeks to 6 years (84%), followed by adults aged 18 to <50 years (73%), then older children aged 6 to <18 years (69%). The IPD rate in each of the older age groups ≥50 years declined as well, but to a lesser extent, approximately 50% each (Table 3). Although overall IPD decreased significantly in all age groups, an increase in IPD was seen in most age groups in the last year of the study (Figure 2A, B).

IPD Serotypes

The overall reduction in annual IPD incidence after PCV13 introduction was largely due to decreases in disease caused by serotypes 19A and 7F. Comparing the PCV13 with PCV7 periods among children aged 6 weeks to 6 years, the RR for IPD caused by 19A was 0.11 (95% CI, 0.03–0.29) and by 7F was 0.03 (95% CI, 0.001–0.16; Table 4). Disease caused by serotype 3 in this age group was relatively uncommon and appeared unchanged (0 to 3 cases each year; Supplementary Table 1). Since IPD caused by other PCV13 serotypes decreased substantially, the change from 0 to 1 case in the last 2 years of the study appears as a 3-fold increase in incidence (0.35 to 1.02 in Table 3); however, this finding is due to the small and annually stable number of serotype 3 cases over the study.

Table 4.

Annual Incidence Rates of Invasive Pneumococcal Disease by Serotype and Age Group for Statistically Significant Serotypes—Before and After Introduction of 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine at Kaiser Permanente Northern California

| Serotype | Serotype Category | PCV7 Period May 2008–April 2010 | PCV13 Period May 2011–April 2018 | Rate Ratio (PCV13 Period/ PCV7 Period) | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of IPD Cases | IPD Incidence Rate | Number of IPD Cases | IPD Incidence Rate | ||||

| Aged ≥6 wk to <6 y | |||||||

| 7F | PCV13 | 10 | 1.9 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.001–0.16 |

| 19A | PCV13 | 13 | 2.47 | 5 | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.03–0.29 |

| Aged ≥6 wk to <18 y | |||||||

| 7F | PCV13 | 23 | 1.38 | 10 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.06–0.25 |

| 19A | PCV13 | 14 | 0.84 | 7 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.05–0.34 |

| 33F | Non-PCV13 | 3 | 0.18 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.004–0.87 |

| Aged ≥18 y to <50 y | |||||||

| 7F | PCV13 | 58 | 1.89 | 38 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.11–0.24 |

| 19A | PCV13 | 21 | 0.69 | 21 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.13–0.46 |

| 3 | PCV13 | 19 | 0.62 | 35 | 0.28 | 0.46 | 0.26–0.81 |

| 9V | PCV13 | 2 | 0.07 | 0 | – | – | N/A–0.86 |

| 12B | Non-PCV13 | 3 | 0.10 | 0 | – | – | N/A–0.42 |

| 13 | Non-PCV13 | 2 | 0.07 | 0 | – | – | N/A–0.86 |

| 23B | Non-PCV13 | 0 | – | 15 | 0.12 | – | 1.12–N/A |

| Aged ≥50 y | |||||||

| 6A | PCV13 | 6 | 0.27 | 7 | 0.07 | 0.28 | 0.09–0.88 |

| 6C | Cross-reactive | 32 | 1.43 | 65 | 0.69 | 0.48 | 0.32–0.74 |

| 7F | PCV13 | 67 | 2.99 | 78 | 0.83 | 0.28 | 0.20–0.38 |

| 9V | PCV13 | 2 | 0.09 | 0 | – | – | N/A–0.82 |

| 19A | PCV13 | 55 | 2.46 | 71 | 0.75 | 0.31 | 0.22–0.44 |

Year of PCV13 introduction at Kaiser Permanente Northern California (May 2010–April 2011) not shown.

Abbreviations: IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (7 or 13 valent); non-PCV13, serotypes not included in PCV13.

Among all ages, there was no consistent pattern of serotype replacement and no predominant serotype emerged during the study. The increase in IPD noted in the last year was caused by various vaccine-type and nonvaccine serotypes (Supplementary Table 2). IPD caused by any of the serotypes contained within the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) decreased significantly from 5.99 cases per 100 000 in 2008–2010 to 3.16 per 100 000 in 2011–2018 (Table 2). Adults aged 18 to <50 years had a significant decrease of 54% in PCV13 serotype 3 disease. Among adults aged ≥50 years, IPD caused by PCV13 and cross-reactive serotypes 6A and 6C decreased significantly by 72% and 52%, respectively (Table 4).

Of the 2721 total IPD cases, 412 (15%) isolates were not serotyped (either not sent or untypeable). Of the 159 IPD cases in those aged ≥6 weeks to <6 years, 44 (28%) isolates were not serotyped, of which 14 (9%) occurred in the PCV13 period (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Antimicrobial Susceptibility

Among all ages, the proportion of S. pneumoniae isolates that were susceptible to penicillin, cefotaxime, and ceftriaxone generally increased during the PCV13 period. There were no reports of isolates resistant to these antimicrobials by 2018 among children aged 6 weeks to 6 years (Supplementary Table 3).

Clinical Diagnosis of IPD

After PCV13 introduction, the most common primary diagnoses associated with IPD were bacteremia/septicemia, pneumonia, and meningitis (Table 5), with bacteremia/septicemia the most common among children aged 6 weeks to 6 years. Meningitis was rare, with only 6 cases occurring during the 8-year PCV13 period in children aged 6 months (2), 1 year (1), and 4 years (3). One 6-month-old received 1 dose of PCV13 before meningitis; this specimen was not available for serotyping. The other 6-month-old received 3 PCV13 doses prior to meningitis caused by serotype 7C. The other children received 4 doses of PCV13; the 1-year-old had meningitis caused by PCV13 serotype 3, while the three 4-year-olds had meningitis associated with non-PCV13 serotypes 11A, 15B/C, and 22F. The cases occurred in 4 Hispanic males, 1 multiracial female, and 1 white male. One 4-year-old had a history of cerebrospinal fluid leak; the other children had no known underlying illnesses.

Table 5.

Distribution of Primary Diagnosis of Invasive Pneumococcal Disease Cases by Age and Year at Kaiser Permanente Northern California

| Clinical Invasive Pneumococcal Disease Diagnosis by Age Groupa,b | May 2008–April 2009 | May 2009–April 2010 | May 2010–April 2011d | May 2011–April 2012 | May 2012–April 2013 | May 2013–April 2014 | May 2014–April 2015 | May 2015–April 2016 | May 2016–April 2017 | May 2017–April 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nc (%) | nc (%) | nc (%) | nc (%) | nc (%) | nc (%) | nc (%) | nc (%) | nc (%) | nc (%) | |

| ≥6 wk to <6 y | 24 (100) | 37 (100) | 20 (100) | 13 (100) | 12 (100) | 11 (100) | 15 (100) | 6 (100) | 9 (100) | 12 (100) |

| Bacteremia/septicemia | 7 (29.2) | 11 (29.7) | 5 (25.0) | 4 (30.8) | 5 (41.7) | 5 (45.5) | 8 (53.3) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (33.3) | 5 (41.7) |

| Pneumonia | 8 (33.3) | 7 (18.9) | 3 (15.0) | 4 (30.8) | 3 (25.0) | 2 (18.2) | 4 (26.7) | – | – | 3 (25.0) |

| Meningitis | 1 (4.2) | 1 (2.7) | – | – | 1 (8.3) | – | 2 (13.3) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (11.1) | – |

| GI | – | 2 (5.4) | – | 1 (7.7) | – | – | – | – | 1 (11.1) | – |

| Febrile illness | 1 (4.2) | 6 (16.2) | 4 (20.0) | – | 2 (16.7) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (33.3) | 2 (16.7) |

| Respiratory | – | 2 (5.4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ENT | – | 1 (2.7) | 2 (10.0) | – | 1 (8.3) | – | – | – | 1 (11.1) | – |

| Joint or bone infection | 1(4.2) | – | – | – | – | 1 (9.1) | – | – | – | – |

| HIV | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Blood cancer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 (16.7) | – | 1 (8.3) |

| Cancer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Othere | 6 (25.0) | 7 (18.9) | 6 (30.0) | 4 (30.8) | – | 1 (9.1) | – | – | – | 1 (8.3) |

| >6 y | 300 (100) | 362 (100) | 326 (100) | 301 (100) | 245 (100) | 268 (100.0) | 205 (100) | 217 (100) | 208 (100) | 289 (100) |

| Bacteremia/septicemia | 112 (37.3) | 204 (56.4) | 208 (63.8) | 223 (74.1) | 187 (76.3) | 214 (79.9) | 164 (80.0) | 164 (75.6) | 158 (76.0) | 221 (76.5) |

| Pneumonia | 113 (37.7) | 90 (24.9) | 64 (19.6) | 36 (12.0) | 30 (12.2) | 35 (13.1) | 22 (10.7) | 26 (12.0) | 32 (15.4) | 29 (10.0) |

| Meningitis | 14 (4.7) | 11 (3.0) | 7 (2.1) | 4 (1.3) | 4 (1.6) | 1 (0.4) | 7 (3.4) | 6 (2.8) | 4 (1.9) | 6 (2.1) |

| GI | 11 (3.7) | 11 (3.0) | 7 (2.1) | 5 (1.7) | 4 (1.6) | 4 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) | 5 (2.3) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (1.4) |

| Febrile illness | 2 (0.7) | 7 (1.9) | 5 (1.5) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (1.2) | 4 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.4) | 5 (2.4) | 5 (1.7) |

| Respiratory | 4 (1.3) | 5 (1.4) | 5 (1.5) | 2 (0.7) | 4 (1.6) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.4) | 3 (1.4) | 7 (2.4) |

| ENT | 8 (2.7) | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.9) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.7) | – | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 5 (1.7) |

| Joint or bone infection | 6 (2.0) | 2 (0.6) | 4 (1.2) | 3 (1.0) | – | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.5) | 2 (0.9) | – | 2 (0.7) |

| HIV | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | – | – | 3 (1.1) | 2 (1.0) | – | – | 2 (0.7) |

| Blood cancer | – | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | – | – | – | 1 (0.5) | – | 2 (0.7) |

| Cancer | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | – | – | – | 1 (0.4) | – | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | – |

| Othere | 26 (8.7) | 24 (6.6) | 20 (6.1) | 24 (8.0) | 11 (4.5) | 2 (0.7) | 3 (1.5) | 5 (2.3) | 3 (1.4) | 6 (2.1) |

All invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) cases, regardless of membership and whether serotyped, were included. Membership refers to patients who were members of Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) for at least 2 months in each year. An IPD case was a unique case separated by a period of 14 days.

Abbreviations: ENT, diagnosis related to ears, nose, or throat; GI, diagnosis related to gastrointestinal tract; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

aAge intervals based on age at time of specimen collection.

bHospital/emergency department discharge primary diagnosis or clinic discharge diagnosis if outpatient.

cNumber of IPD cases in specified category.

dThe 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) was introduced for KPNC use in 2010.

e“Other”category includes infection at other sterile sites not already captured in the categories above (eg, tubo-ovarian abscess, lymph node cyst).

Of children aged 6 weeks to 6 years with IPD caused by a PCV13 serotype in the PCV13 period (n = 16), 6 had received 4 doses of PCV13 prior to the IPD episode; 4 episodes were caused by serotype 3 (including the meningitis case described above), 1 by 19A and 1 by 19F. Of children who received 3 doses of PCV7 followed by a booster dose of PCV13, 3 had IPD caused by serotype 3 and 1 by 19A. One child had 2 doses of PCV13 prior to IPD caused by serotype 19A. The remaining children with IPD caused by PCV13 serotypes after vaccine introduction (n = 5) had not received any doses of PCV13. Among all individuals aged ≥6 years, bacteremia/septicemia was generally the most frequent diagnosis, followed by pneumonia or meningitis (Table 5).

Underlying Comorbidities

Among adults age ≥50 years with IPD, the presence of underlying conditions increased with age, generally peaking between age 65 and 79 years (Supplementary Table 4). Among the 159 children aged 6 weeks to <6 years with IPD, comorbidities reported included asthma (n = 15), cancer (n = 8), diabetes (n = 2), hypertension (n = 2), and stroke (n = 2).

Clinical Outcomes

Most patients with IPD were discharged to home (60%), although this decreased from 72% to 49% over the 10-year study. Correspondingly, the proportion of patients who required home health support or skilled nursing increased from 14% to 32%. The proportion of patients who died ranged from 8% to 13% per year throughout the study. Of the 2 children aged 6 weeks to 6 years who died from IPD, 1 had a history of severe congenital anomalies, including holoprosencephaly, and the other had small intestine malabsorption diagnosed 6 months prior to death.

DISCUSSION

In this observational surveillance study in a large US healthcare system during the 2 years before and 8 years after PCV13 introduction, annual IPD rates decreased for every age group. Compared with the PCV7 baseline period, overall IPD incidence declined 65% and PCV13-serotype IPD declined 84% in children aged 6 weeks to 6 years during the PCV13 period. These decreases were mostly due to large declines in disease caused by serotypes 19A and 7F (89% and 97%). Although we did observe a trend toward increased non-PCV13 serotypes, the change was not statistically significant. Despite these reassuring observations, ongoing surveillance for non-PCV13 serotypes is important for this age group. Current study findings demonstrate that when compared with the PCV7 period, PCV13 vaccination of infants and children further decreased IPD incidence in young children.

In this study, we identified statistically significant decreases in IPD among all ages after PCV13 introduction that were particularly pronounced among those aged <50 years. Among older adults, we observed significant changes in some vaccine-type and cross-reactive serotypes. During most of the study, PCV13 use among adults was limited, and only minor changes in PPSV23 recommendations for adults occurred [11, 14–17]. These findings, taken together with the findings in young children, suggest that at least some of the observed reduction in disease among adults occurred via indirect effects. Overall, this study suggests that routine PCV13 use in children had both direct effects in vaccinated children and indirect herd effects before the 2014 ACIP recommendation for PCV13 use in adults aged ≥65 years.

Significant decreases were seen in IPD caused by serotype 3 in adults aged 18 to <50 years and by serotypes 6A and 6C in adults aged ≥50 years. The decrease caused by serotype 6C is consistent with earlier reports of cross-functional antibody responses of PCV13 to serotype 6C (PCV13 includes serotypes 6A and 6B) but not PCV7 (which includes only serotype 6B) [18, 19]. This cross-reactivity likely stems from capsular similarity of serotypes 6A and 6C; early experiments using the Quellung reaction classified serotype 6C isolates as belonging to serotype 6A, but use of specific antibodies for serotyping distinguished between these serotypes [20, 21]. During the study, adults were largely unvaccinated against serotype 6A, which is not included in PPSV23. Additionally, PCV13 uptake in the adult population was low for all (18 to <64 years) or most (≥65 years) of the study. Given these factors, the observed decrease in serotype 6C disease in the older population likely stems from a herd effect from cross-reactive antibodies generated in children vaccinated with PCV13.

Study strengths include KPNC’s large, ethnically and racially diverse population. As no single racial or ethnic group comprised more than 33% of the youngest age group, our findings may be more generalizable. In addition, we were able to access the complete medical record for all IPD cases. Further, KPNC’s use of a central laboratory ensured standardized processing of isolates. Finally, the 10-year study allowed evaluation of IPD incidence before and after PCV13 introduction, allowing observation of directly vaccinated populations and inference of indirect effects among unvaccinated populations.

Study limitations include the nonavailability of some isolates for serotyping and small numbers of IPD cases in some years and age groups, which limited the statistical inferences that could be made. However, low numbers of IPD cases are an important hallmark of the effectiveness of PCVs. Overlap in the serotypes included in PPSV23 and PCV13 may also confound determination of each vaccine’s contribution to reductions in serotype-specific incidence. However, recommendations for PPSV23 did not change significantly during the study, suggesting that decreased incidence was associated with PCV13.

CONCLUSIONS

Introduction of routine PCV13 use in infants and young children was associated with substantial declines in IPD in both children and adults, demonstrating that routine PCV13 use had both direct and indirect effects. PCV13 was associated with significant reductions in vaccine-serotype IPD and overall IPD rates among individuals aged ≥6 weeks, despite some increase in disease caused by serotypes not included in the conjugate vaccine. Disease reduction was predominantly due to decreases in disease caused by serotypes 19A and 7F, but other serotypes were important contributors to this trend. Since pneumococcal disease is a known complication of influenza [22–24], IPD increases observed during the last year of the study may be potentially related to the severe 2017–2018 influenza season. However, we will continue to monitor this in our ongoing large-scale surveillance. This continued evaluation of trends in IPD incidence and serotype distribution will be important in the setting of increased PCV13 use in adults and to inform future vaccine development.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Presented in part: Ninth Biennial International Symposium on Pneumococci and Pneumococcal Diseases, Hyderabad, India, 9–13 March 2014 (abstract ISPPD-0456), and the 2014 Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting, Vancouver, Canada, 3–6 May 2014 (abstract 754622).

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Charlie Chao of the Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center and Gwendolyn Guevara and all the staff at the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Regional Laboratory for their contributions to invasive pneumococcal disease specimen organization and shipment to the Boston Medical Center. Editorial/medical writing support was provided by Jill E. Kolesar, PhD, of Complete Healthcare Communications, LLC (North Wales, PA), a CHC Group Company, and was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Author contributions. L. A. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analyses. All authors contributed to study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript drafting, review, and approval for submission. L. A., A. Y., N. P. K., and S. I. P. acquired the data. A. Y. conducted the statistical analyses.

Financial support. This work was supported by Pfizer Inc. Pfizer employee–authors contributed to study conception and design; analysis and interpretation of data; and manuscript drafting, review, and approval for submission.

Potential conflicts of interest. N. P. K. has received research support from Pfizer Inc, Merck, Sanofi Pasteur, GSK, MedImmune, Protein Science, and Dynavax. S. I. P. has an investigator-initiated grant to Boston Medical Center from Merck Vaccines and Pfizer Inc, and has received honoraria for advisory board meetings and symposia from GSK Biologicals, Seqirus, and Pfizer Inc. W. C. G., D. A. S., and K. J. C. are employees of Pfizer Inc and may hold stock or stock options. All remaining authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2008; 83: 373–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Invasive pneumococcal disease in children 5 years after conjugate vaccine introduction— eight states, 1998–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008; 57:144–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Poehling KA, Talbot TR, Griffin MR, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease among infants before and after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. JAMA 2006; 295:1668–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Direct and indirect effects of routine vaccination of children with 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease— United States, 1998–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005; 54:893–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Licensure of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) and recommendations for use among children— Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010; 59:258–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prevnar 13® (pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate vaccine [diphtheria CRM197 protein]). Full Prescribing Information. Collegeville, PA: Pfizer Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Preventing pneumococcal disease among infants and young children. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2000; 49:1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among children aged 6–18 years with immunocompromising conditions: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62:521–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Licensure of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine for adults aged 50 years and older. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61:394–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for adults with immunocompromising conditions: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61:816–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tomczyk S, Bennett NM, Stoecker C, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among adults aged ≥65 years: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014; 63:822–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization. Pneumococcal vaccines WHO position paper— 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2012; 87:129–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; 19th Informational Supplement. CLSI document M100-19. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bennett NM, Whitney CG, Moore M, et al. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for adults with immunocompromising conditions: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61:816–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nuorti JP, Whitney CG; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Prevention of pneumococcal disease among infants and children— use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine— recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2010; 59:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of pneumococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 1997; 46:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kobayashi M, Bennett NM, Gierke R, et al. Intervals between PCV13 and PPSV23 vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64:944–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cooper D, Yu X, Sidhu M, et al. The 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) elicits cross-functional opsonophagocytic killing responses in humans to Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 6C and 7A. Vaccine 2011; 29:7207–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grant LR, O’Brien SE, Burbidge P, et al. Comparative immunogenicity of 7 and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines and the development of functional antibodies to cross-reactive serotypes. PLoS One 2013; 8:e74906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Park IH, Pritchard DG, Cartee R, et al. Discovery of a new capsular serotype (6C) within serogroup 6 of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45:1225–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin J, Kaltoft MS, Brandao AP, et al. Validation of a multiplex pneumococcal serotyping assay with clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44:383–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paul L. Influenza and pneumococcal disease can be serious, health officials urge vaccination. Available at: https://www.nfid.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/press-release-3.pdf Accessed January 13, 2020.

- 23. McCullers JA. Insights into the interaction between influenza virus and pneumococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006; 19:571–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Klugman KP, Chien YW, Madhi SA. Pneumococcal pneumonia and influenza: a deadly combination. Vaccine 2009; 27 Suppl 3:C9–C14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.