Abstract

Context:

Since its outbreak, the COVID-19 pneumonia pandemic is rapidly spreading across India; although computed tomography of chest (CT chest) is not recommended as a screening tool, there is a rapid surge in the CT chest performed in suspected cases. We should be aware of the imaging features among the Indian population.

Aim:

To analyze the CT chest features in Indian COVID-19 patients.

Settings and Design:

Retrospective study.

Subjects and Methods:

CT chest of 31 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) verified patients of COVID-19 was assessed for ground-glass opacities (GGO), consolidations, bronchiectasis, pleural effusions, vascular enlargement, crazy paving, and reverse halo sign.

Statistical Analysis Used:

The data was analyzed in Microsoft Excel 2019.

Results:

Only one patient showed a normal scan. Multilobar involvements with parenchymal abnormalities were seen in all the patients with bilateral involvement in 74.1%. 42.5% of the lung parenchymal abnormalities were pure GGOs, while 41.6% had GGOs mixed with consolidation. Peripheral and posterior lung field involvement was seen in 70.5% and 65.5%, respectively; 56.8% had well-defined margins. Pure GGOs were seen in all six patients, who underwent CT in the first 2 days of onset of symptoms. Seventeen patients scanned between 3 and 6 days of the illness showed GGOs mixed with consolidation and pure consolidations 76%. Vascular enlargement, crazy paving, and reverse halo sign were seen in 70%, 53%, and 35% of the patients, respectively. Patients scanned after 1 week of symptoms showed traction bronchiectasis along with GGOs and or consolidations.

Conclusions:

COVID-19 pneumonia showed multifocal predominantly subpleural basal posteriorly located GGOs and/or consolidations which were predominantly well defined. “Crazy paving” was prevailing in the intermediate stage while early traction bronchiectasis among the patients presented later in the course of illness.

Keywords: Coronavirus, COVID-19, CT chest, pneumonia

Introduction

The 2019 novel coronavirus or COVID-19 infection started as a cluster of pneumonia cases of unknown etiology in China in December 2019,[1] and was declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020.[2] The first case of COVID-19 in India was reported from the state of Kerala on January 30, 2020.[3] Since then, the number of cases has increased precipitously with a great burden on the Indian healthcare system. Although the COVID-19 infection has lesser mortality than severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) viruses, it has much stronger transmission rates.[4]

Till date, there has not been any targeted therapeutic drug and vaccine available for this infection. Early detection and quarantine of the patient are paramount, given the high transmission rate of this disease. The most common clinical features of COVID-19 pneumonia are fever, fatigue, dry cough, anorexia, dyspnea, and myalgia.[5] However, making a diagnosis of COVID-19 based on clinical features is difficult owing to overlapping symptoms with other viral types of pneumonia such as influenza A and B.[6] The definitive diagnosis is made by RNA detection by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).[7] But, a negative RT-PCR does not guarantee the absence of infection. In their retrospective analysis, Ai et al. reported 41% false-negative rates at initial presentation.[8] This creates a public health problem as such false-negative patients will continue spreading the infection. RT-PCR itself is a time-consuming test. With an increasing number of cases, a shortage of testing kits in resource-poor regions poses another challenge. In such a situation, the computed tomography of the chest (CT chest) can be used as an adjunct in making a diagnosis. Multiple studies have shown that peripherally distributed ground glass opacifications and patchy consolidations with posterior predominance in suspected individuals are diagnostic.[9,10,11,12]

Most of the publications on CT chest findings in COVID-19 infection are from China. As per the best of our knowledge, there has not been a study on how COVID-19 pneumonia appears on CT in Indian population. The radiologists and physicians should be abreast with the knowledge of the chest CT appearance of COVID-19 patients in the subcontinent. We present CT chest features of COVID-19 patients in India.

Subjects and Methods

It was a retrospective observational study done in a tertiary care hospital in Mumbai, India.

Patients

Thirty-one consecutive patients were evaluated. The inclusion criteria was a positive result or COVID-19 on RT-PCR (Rotorgene Q, Qiagen) while the exclusion criteria were the negative result on RT-PCR for COVID-19 regardless of chest CT findings and poor quality of scans. The chest CT chest scans were performed between March 20, 2020 and April 30, 2020. The clinical data, including exposure and travel history, was recorded along with the patient demographic details. All the HRCTs were evaluated for the characteristics of pulmonary observations, viz., morphology of the lesions, their locations and margins. Besides this, presence traction bronchiectasis, pleural effusion, vascular enlargement, lymphadenopathy, crazy paving, and reverse halo sign were also analyzed.

CT acquisition

All the patients were subjected to thin-section CT. The median time of image acquisition from the time of the start of symptoms was 6 days (minimum of 2 days to a maximum of 10 days). All the CT scans were done in 128 slices, multidetector CT scanner (Somatom Definition, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) without the use of intravenous contrast. The scan parameters were as follows: tube voltage, 120 kV; automatic tube current (180 mA–400 mA); iterative reconstruction technique; detector, 64 mm; rotation time, 0.33 s; section thickness, 5 mm; collimation, 0.625 mm; pitch, 1.5; matrix, 512 × 512; and breath-hold at full inspiration. Reconstruction kernel used was sharp with a thickness of 1 mm and an interval of 0.8 mm.

Image analysis

Two radiologists (with experience of 20 years and 5 years) reviewed the CT images of the patients with verified RT-PCR positivity on the department's PACS system on the lung window (W: 1500 HU, L: -600 HU) and mediastinal window (W: 350 HU, L: 40 HU). In the first step, the radiologists identified each parenchymal observation on the CT images. Each observation occupying one lung segment was counted as one. Large observations spreading across multiple lung segments were counted as the number of segments involved, which means if a large observation occupied “n” number of segments, the number of observations were counted “n.” Each of these was analyzed for specific parameters which were: density [pure ground-glass opacification or ground-glass opacities (GGO), pure consolidation, mixed GGO, and consolidation], axial location (peripheral which was defined as the outer one-third of the lung or central which was defined as the inner two-third of the lung), anteroposterior location (based on a horizontal line drawn across the axillary midline), lobar location, and margin of the lesion. The CT images were further evaluated for the lobes involved, bilateral involvement, and the presence of traction bronchiectasis, pleural effusion, vascular enlargement, lymphadenopathy, crazy paving, the reverse halo.

Statistics

All the data which was acquired was recorded and tabulated in Microsoft Excel 2019, and the same was used to do statistical analysis.

Results

Demography

The median age of patients in our study was 64.5 years, with the interquartile range of 53.7 years–70 years. Twenty-seven out of our thirty-one patients were males while rest were females.

Clinical characteristics

Clinical characteristics are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients

| Characteristics | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 27 |

| Female | 4 |

| Age (years) | |

| Median | 64.5 |

| Interquartile range | 53.7-70 |

| Exposure History | |

| Recent history of foreign travel | 6 |

| Exposure to a known infected person | 18 |

| Unknown | 7 |

| Comorbidities | |

| TB | 0 |

| Any malignancy | 1 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 4 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 6 |

| Cardiac disease | 2 |

| Signs and symptoms | |

| Fever | 31 |

| Cough | 22 |

| Sputum production | 7 |

| Myalgia | 25 |

| Sore throat | 17 |

| Runny nose | 5 |

| Disorientation with fever | 1 |

Out of 31 patients, 18 had contact with a patient with known COVID-19 infection, six had a history of travel to foreign countries, while in seven patients, we failed to identify the source. Fever was the predominant symptom in all of the 31 patients with 22 of them having cough. Myalgia was present in 25 patients, while 17 patients had a sore throat. Sputum production was present in seven patients. Runny nose was an infrequent symptom present only in five patients. We assessed our patients for existing comorbidities and found that six of them had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, four had interstitial lung disease, two of them had cardiac failure, and one had bronchogenic carcinoma with history of chemotherapy.

Two patients had extrapulmonary manifestations; one presented with deranged hepatic enzymes, another presented with clinical suspicion of encephalitis.

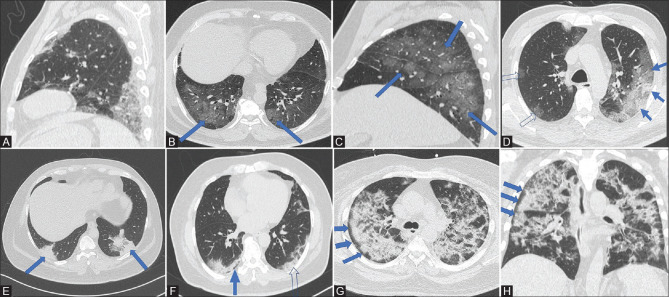

Chest CT findings

A total number of 190 parenchymal observations were detected and analyzed [Table 2]. One of our patients aged 33 years had no parenchymal abnormalities on CT chest. Bilateral involvement was seen in 23 patients (74.1%), while in the rest, seven of them had unilateral disease. All 30 patients had multilobar involvement. The right lower lobe was most frequently involved lobe in 20 of the 31 patients, while right middle lobe was least frequently involved in eight patients. Right upper lobe was affected in 13 patients, left lower lobe in 14, and left upper lobe in 10 of 31 patients. Most of the parenchymal observations were concentrated in the lower lobe with 94 out a total of 190 (49.4%) [Figure 1A]. When they were individually analyzed, we found that 81 of them (42.6%) were purely GGO [Figure 1B and C] and 79 (41.4%) had an admixture of GGO and consolidation [Figure 1D]. Thirty of 190 (15.7%) were purely consolidations [Figure 1E]. One hundred eight (56.8%) had well-defined margins [Figure 1F], while the rest of them were ill-marginated (43.2%). A total of 134 observations (70.5%) were located at the periphery with 98 of those in contact with the pleura. Thirty-six of them are showing subpleural sparing [Figure 1G and H]. Thirty-four (17.8%) were involved central zone while 22 (11.5%) of them were encompassed both center and periphery. 65.5% (124 of 190) were seen in the posterior half of the lung parenchyma, while 32.1% (61 out of 190) were seen anteriorly. Five observations were large enough to involve both anterior and posterior halves.

Table 2.

Analysis of individual lung parenchymal observations in 30 patients affected with COVID-19

| Lesions (n=190) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Morphology of lesion based on density | |

| Consolidation | 30 (15.7) |

| GGO | 81 (41.6) |

| Mixed GGO and consolidation | 79 (42.5) |

| Anteroposterior location | |

| Anterior | 61 (32.1) |

| Posterior | 124 (65.2) |

| Anterior and posterior | 5 (2.6) |

| Axial location | |

| Central | 34 (17.8) |

| Peripheral | |

| with pleural contact | 98 (51.5) |

| with subpleural sparing | 36 (18.9) |

| Central and peripheral | 22 (11.5) |

| Lobar location | |

| Upper lobe | 72 (37.8) |

| Lower lobe | 94 (49.4) |

| Middle lobe | 24 (12.6) |

| Margin | |

| Well defined | 108 (56.8) |

| III-defined | 82 (43.2) |

Figure 1 (A-H).

(A) CT chest (sagittal) shows mixed GGO and consolidation in the lower lobe in the posterior aspect with pleural contact. (B and C) axial and sagittal images of the same patient showing pure GGOs (solid blue arrows) in a posterior and peripheral distribution. (D) CT chest (axial) shows mixed consolidation and GGO (solid blue arrows) on the left side located peripherally while foci of pure GGOs are seen on the right side (open arrows). (E) CT chest (axial) shows pure consolidations (solid blue arrows) in both the lungs seen posteriorly, peripherally with pleural contact. (F) CT chest (axial) shows well-defined margins of subpleural consolidations on the left side with pleural contact (open arrow). On the right, the consolidations show subpleural sparing (solid blue arrow). (G and H): Axial and coronal images show bilateral patchy consolidations in a patient with subpleural sparing more pronounced on the right side (solid blue arrows)

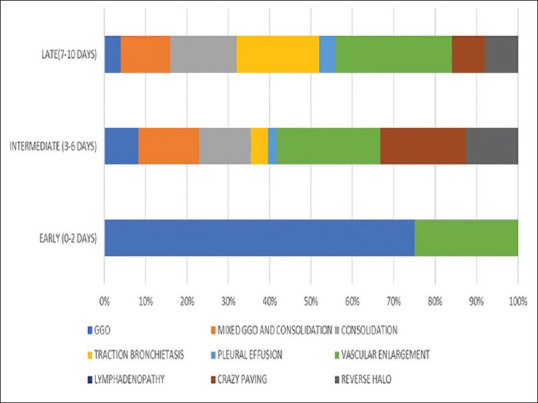

We also stratified the CT features based on time elapsed between the start of symptoms and date of acquisition [Table 3 and Figure 2]. The time period was divided into early (0–2 days), intermediate (2–6 days), and late (6–10 days).

Table 3.

CT features based on time elapsed between the start of symptoms and date of acquisition

| Findings on HRCT | Early (0-2 days) n=6 | Intermediate (3-6 days) n=17 | Late (7-10 days) n=8 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ground glass opacification | 6 | 4 | 1 |

| Mixed GGO and consolidation | 0 | 7 | 3 |

| Consolidation | 0 | 6 | 4 |

| Traction Bronchiectasis | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Pleural effusion | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Vascular enlargement | 2 | 12 | 7 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Crazy paving | 0 | 10 | 2 |

| Reverse halo | 0 | 6 | 2 |

Figure 2.

CT findings in relation to the time of imaging after onset of symptoms

Early

Six patients were CT scanned in the initial 2 days of onset of presentation. From our observations, when scanned early, all of the six patients had pure GGOs. None of them had mixed GGO with consolidations and pure consolidations. Two of the patients had vascular enlargement. None of the patients had crazy paving, traction bronchiectasis, lymphadenopathy, or pleural effusion.

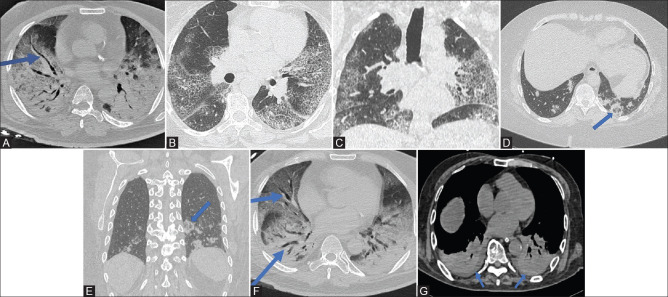

Intermediate

Seventeen patients were scanned between 3 and 6 days. Four of them had a presence of pure GGOs, while mixed GGO with consolidation and pure consolidations were present in seven and six patients, respectively. The vascular enlargement was seen in 12 patients [Figure 3A], crazy paving in nine patients [Figure 3B and C], and reverse halo sign in six patients [Figure 3D and E]. Bronchiectasis was seen in two patients. One patient had pleural effusion.

Figure 3 (A-G).

(A): CT chest (axial) shows markedly enlarged vessel (solid blue arrow) against a backdrop of consolidations and GGO in a COVID-19 patient. Acute respiratory distress syndrome with dense consolidations is seen on both sides. (B and C) Axial and coronal images show bilateral interstitial septal thickening with background ground glass giving the appearance of “crazy paving.” (D and E): axial and coronal images from CT chest of a patient showing circular consolidation with GGO within in the posterior, peripheral location, abutting the pleura in the left lower lobe (solid blue arrow). (F) In the same patient of image 3A, this CT chest (axial) shows bilateral bronchiectasis (solid blue arrows) against a backdrop of bilateral consolidations and ground glass. Acute respiratory distress syndrome with dense consolidations is seen on both sides. (G) CT chest (axial) shows bilateral pleural effusion at the lung bases (solid blue arrows). Acute respiratory distress syndrome with dense consolidations is seen on both sides

Late

Eight patients were scanned in the time interval of 7 to 10 days. Only one patient had pure GGO while pure consolidations and consolidations mixed with GGO were present in four and three patients, respectively. Bronchiectasis was seen in five patients [Figure 3F], vascular enlargement in seven patients, crazy paving in two patients, reverse halo sign in two patients, and pleural effusion was seen in one patient [Figure 3G].

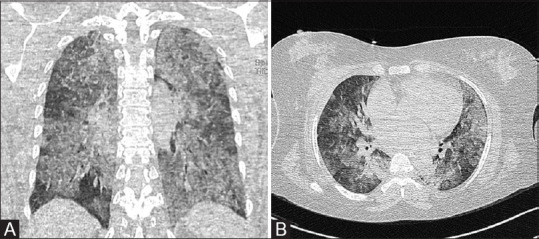

Two of the patients imaged in the late stage of the disease had features suggestive of acute respiratory distress syndrome [Figure 4A and B].

Figure 4 (A and B).

(A and B) Coronal and axial sections show acute respiratory disease syndrome type of lung involvement.

No lymphadenopathy was found in any group of patients.

Uncommon presentation

One patient had a single region of confluent tree in bud endobronchial nodules in the superior segment of her right lower lobe.

Discussion

In this study, we have retrospectively analyzed the HRCT features of RT-PCR positive, COVID-19 pneumonia in a cohort of the Indian population. Although CT chest is not used commonly in India right now to screen patients, its use in suspected patients has rapidly increased. It has the potential to become an indispensable tool in the management of COVID-19 patients.[6] In view of the limited resources for RT-PCR, CT chest can be used as an adjunct, if every case needs to be detected.[13] Also, CT chest gives fast results as compared to RT PCR. Studies by Fang et al.,[14] Long et al.,[15] and Ai et al.[8] have reported the sensitivity of chest CT as 98%, 97.2%, and 97%, respectively, which were higher than the sensitivity of first RT-PCR on the patients. These studies have also reported substantial false-negative rates of RT-PCR. In such a scenario, chest CT emerges as an important tool in patient triage. With a higher sensitivity, CT can be used to rule out patients for infection and isolate the suspected patient from the community, thus helping in disease containment. Considering the dearth of publications from Indian subcontinent on chest CT findings of COVID-19 and most of the literature based on Chinese patients, we investigate how similar or different the imaging findings are in contrast to rest of the world.

Most of the patients in the study gave a history of contact with a known COVID-19 pneumonia patient with fever, myalgia, and sore throat as the three most common symptoms.

When compared SARS and MERS, multiple overlapping CT chest features such as peripheral GGO and consolidation are present; however, bilateral involvement of lungs is seen in COVID-19 while MERS and SARS had unilateral preponderance.[16,17]

In our study, we see that bilateral, multilobar, peripheral, and predominant posterior involvement of pulmonary parenchyma and these features are in agreement with chest CT findings reported elsewhere in the world.[9,10,12,18] Lower lobe involvement was a predominant feature. GGO and mixed GGO-consolidation patterns dominated the chest CT picture with a smaller number of purely consolidations. A systematic review of imaging findings in 919 patients done by Salehi et al. reports that isolated GGO and combination of GGO with consolidation are most common CT manifestation.[12] Our findings are coherent with the data mentioned above. It has also been reported that the presence of consolidations is primarily associated with the elderly age group.[10] In our study, the near equivalence of consolidations mixed with GGO and purely GGO lesions can also be explained by the fact that our patient group was mostly elderly. GGO along with intervening septal thickening giving rise to crazy paving was observed in 40% of our patients.

Interestingly, the majority of the GGO and consolidations had characteristically well-defined margins (56.8%). In another similar study, the reported incidence of well-defined margins was 30%.[11] Another recurring observation was vascular enlargement within the region of the pulmonary lesions in more than half of our patients which might have been caused due to acute inflammatory response. Zhao et al. have also reported such finding in their study on 101 patients.[6]

We also assessed the frequency of CT findings according to the time elapsed between the start of symptoms and CT acquisition. While GGOs are the most common of when individually analyzed, their predominance is mainly in the patients who are scanned early (0 to 2 days). These patients in the early subset also a showed complete absence of consolidations. Vascular enlargement in the GGO region was found in a few patients when compared to the other subset. Pure GGO lesions were less common in the patients who were scanned in the intermediate period (3 to 7 days). In them, GGOs with consolidations and pure consolidations were seen much more common than seen in the one who was scanned early. The presence of vascular enlargement in the region of ground glass opacification, crazy paving, and reverse halo sign was most common in these patients. The presence of traction bronchiectasis in two of the patients (scanned on day 6) does point toward the onset of fibrosis. The patients who were scanned late (7 to 10 days) were found to have more pure consolidations and mixed GGO and consolidation with a maximum incidence of traction bronchiectasis signaling the presence of fibrotic changes in the lung parenchyma. Crazy paving, vascular enlargement, and reverse halo sign present in this subset; their incidence was less as compared to that of the intermediate period. Such a pattern of disease progression resembles that of acute lung injury whereby an initial acute insult leads to GGOs which later coalesce to form dense consolidation and then evolve and organize more linearly and somewhat with a crazy-paving pattern and emergence of the reverse halo sign.

The reverse halo sign seen in few of our patients may point toward a pattern of organizing pneumonia which has been observed in other studies as well.[10,11,19] Crazy paving was seen in 40% of our patients of which substantial number were scanned in the intermediate period. The reported incidence of crazy paving elsewhere has been 4% to 40%.[9,20] Interestingly pleural effusion was seen in two of our patients. In one of the two patients, this might be explained by the fact that he had imaging features of cardiac failure and associated volume overload.

One of the patients in the study had CT chest on day 4 after the onset of symptoms and had no imaging findings.

There were a few limitations to our study. The limited number of patients in our study was the main restrain. The inclusion of more patients would have made this study more comprehensive. Second, this study includes only one CT scan done per patient at the time of admission to hospital, and no follow-up CT scans were available for review as we followed up our patients for response and progression in X-ray. Analysis of follow-up CT scans would have helped establish the temporal progression of the disease.

In conclusion, this analysis informs us that COVID-19 pneumonia in Indian patients manifests majorly as pure GGO to a mixture of GGO and consolidation in bilateral lungs. The involvement is peripheral with pleural contact predominantly in the posterior aspect of the lung. Multilobar involvement is regular with predilection toward lower lobes. The opacities are well marginated, which is peculiar to Indian patients. Vascular enlargement, crazy paving, and “reverse halo” sign are ancillary findings which should steer the radiologist toward the diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia. Pleural effusion is uncommon, though it can be seen in a few patients. COVID-19 pneumonia follows a pattern where peripherally placed GGOs dominated the early phases while consolidations emerged later.

With disease progression, there is an increasing amount of traction bronchiectasis and crazy paving. The proportion of crazy paving is seen on the higher side in Indian patients. Although the above-mentioned features are classically present in most of the patients, their absence does not mean the absence of COVID-19 as we see in one of our younger patient who had a single region of endobronchial nodules in the right lung.

Thus, the CT chest findings in Indian patients are in agreement with other studies; however, the incidence of crazy paving is more in our patients, and most of the lesions have well-defined margins.

More such studies are needed in Indian population with larger sample size and they will further expand our knowledge regarding the radiology of this pandemic.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91:157–60. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [Last cited on 2020 Apr 04]. Update on Novel Coronavirus: One positive case reported in Kerala [Internet] Available from: pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1601095 .

- 4.Dai W, Zhang H, Yu J, Xu H, Chen H, Luo S, et al. CT imaging and differential diagnosis of COVID-19. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2020;71:195–200. doi: 10.1177/0846537120913033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao W, Zhong Z, Xie X, Yu Q, Liu J. Relation between chest CT findings and clinical conditions of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia: A multicenter study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;214:1072–77. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel A, Jernigan DB. 2019-nCoV CDC Response Team. Initial Public Health Response and Interim Clinical Guidance for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak - United States, December 31, 2019-February 4, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:140–46. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6905e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, Zhan C, Chen C, Lv W, et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: A report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020:200642. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernheim A, Mei X, Huang M, Yang Y, Fayad ZA, Zhang N, et al. Chest CT findings in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19): Relationship to duration of infection. Radiology. 2020;295:200463. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200463. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song F, Shi N, Shan F, Zhang Z, Shen J, Lu H, et al. Emerging 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020;295:210–7. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoon SH, Lee KH, Kim JY, Lee YK, Ko H, Kim KH, et al. Chest radiographic and CT findings of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Analysis of nine patients treated in Korea. Korean J Radiol. 2020;21:494–500. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2020.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salehi S, Abedi A, Balakrishnan S, Gholamrezanezhad A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A systematic review of imaging findings in 919 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;215:87–93. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.23034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohli A. Can imaging impact the coronavirus pandemic? Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2020;30:1–3. doi: 10.4103/ijri.IJRI_180_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang Y, Zhang H, Xie J, Lin M, Ying L, Pang P, et al. Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: Comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology. 2020:200432. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long C, Xu H, Shen Q, Zhang X, Fan B, Wang C, et al. Diagnosis of the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): rRT-PCR or CT? Eur J Radiol. 2020;126:108961. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.108961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paul NS, Roberts H, Butany J, Chung T, Gold W, Mehta S, et al. Radiologic pattern of disease in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: The Toronto experience. Radiographics. 2004;24:553–63. doi: 10.1148/rg.242035193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Das KM, Lee EY, Langer RD, Larsson SG. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: What does a radiologist need to know? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;206:1193–201. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.15363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung M, Bernheim A, Mei X, Zhang N, Huang M, Zeng X, et al. CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Radiology. 2020;295:202–7. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kong W, Agarwal PP. Chest imaging appearance of COVID-19 infection. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2020;2:e200028. doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han R, Huang L, Jiang H, Dong J, Peng H, Zhang D. Early clinical and CT manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22961. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]