Abstract

Mass mortality events are unusual in the Crato Formation. Although mayflies’ accumulations have been previously reported from that unit, they lacked crucial stratigraphic data. Here we provide the first taphonomic analysis of a mayfly mass mortality event, from a layer 285 cm from the top of the Formation, with 40 larvae, and an overview of the general biological community structure of a three meters deep excavated profile. The only other autochthonous taxon observed in the mayfly mortality layer was the gonorynchiform fish Dastilbe. The larvae and fishes were smaller than usual in the layer 285 cm, suggesting that they lived in a shallow water column. Their excellent preservation and a lack of preferential orientation in the samples suggest an absence of significant transport. All mayflies belong to the Hexagenitidae, whose larvae lived in quiet waters. We also recovered allochthonous taxa in that layer indicative of drier weather conditions. Adjacent layers presented crystals and pseudomorphs of halite, suggesting drought and high salinity. In other layers, Dastilbe juveniles were often found in mass mortality events, associated with a richer biota. Our findings support the hypothesis that the Crato Formation’s palaeolake probably experienced seasonal high evaporation, caused by the hot climate tending to aridity, affecting the few autochthonous fauna that managed to live in this setting.

Subject terms: Entomology, Palaeoclimate, Palaeoecology

Introduction

The Crato Formation (northeastern Brazil) is a lithostratigraphic unit well-known by its fossiliferous laminated limestones. It represents a paleoenvironment composed of a lacustrine complex approximately 100 km × 50 km in total area 1,2, with freshwater constituting the superficial and marginal portions of the lakes1–3. The unit was deposited during the Upper Aptian, Lower Cretaceous4, under a stratified water column, with relatively well oxygenated upper layers, and reportedly anoxic lower layers2,5,6.

Insects preserved in carbonates often belong to groups that rely on water for habitat, hunting, or laying eggs7. Possibly, the aquatic insect fossils (e.g. Ephemeroptera) of this deposit represent both autochthonous and allochthonous taxa, as some may have been transported from the lotic to the lentic regions8. Taxa that not necessarily depended on lotic environments, such as the autochthonous Hexagenitidae larvae (Ephemeroptera) and Dastilbe fish9–11, stands out as dominant groups in the Crato Formation8,10,12.

Mass mortality events are unusual in the Crato Formation, but assemblages of mayflies’ larvae found in its yellowish limestones have been previously reported as representing such episodes9,13. Small accumulations of more than three insects nearby on the same bedding plane are known for this unit, but such aggregations are rare14. Although Menon and Martill8 alleged there was no clear evidence for mass mortality events in the Crato Formation, Martins-Neto and Gallego15 stated that many of the taxa that depended on freshwater to live and/or reproduce probably suffered mass mortality events, that could have been caused by a periodic increase of H2S16. According to Martins-Neto13, mayflies’ mortality horizons during the Cretaceous are observed in a geographic range covering Mongolia, north of China, Transbaikalia (Russia), northwest Africa, and the northeast of Brazil, having as a possible cause the tropical climate tending to aridity. However, previous observations on mayfly mass mortality events within the Crato Formation lacked crucial stratigraphic control. Here we provide the first taphonomic analysis of specimens collected from controlled excavations, the first of their kind for that unit.

Material and methods

Geological setting

The Araripe Basin is located in Brazil’s northeastern region and presents outcrops in three different states: southwestern Ceará, northwestern Pernambuco, and eastern Piauí17. Among the Cretaceous deposits, the Santana Group is a depositional sequence associated with the South Atlantic opening. It comprises, from bottom to top, the Barbalha, Crato, Ipubi, and Romualdo Formations18. From these, the Crato Formation represents a stratigraphic sequence of lacustrine deposits with a predominance of carbonates. It is constituted by six units named, from bottom to top, C1–C6, interleaved by sandstones, siltstones, and shales19. These six carbonate packages can be found from the municipality of Santana do Cariri until near Porteiras, both in Ceará, in a series of laminated limestone outcrops on the Araripe Plateau, where they are commonly located in commercial quarries or river margins20. More detailed geological and sedimentological information about the Crato Formation can be found in Assine18, and Viana and Neumann20.

Excavation and collection

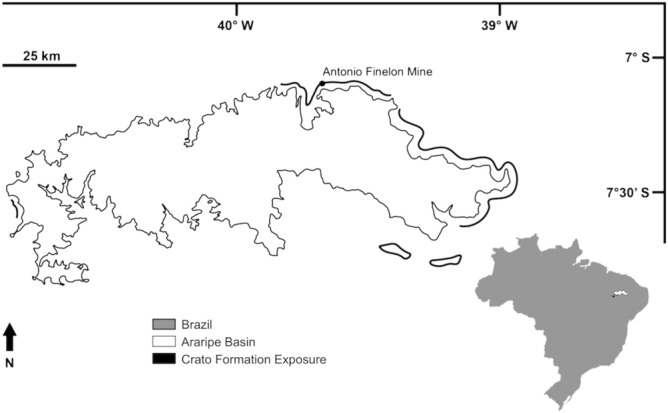

Controlled excavations were conducted by the group of palaeontologists of the Universidade Regional do Cariri (URCA) in an outcrop of the Crato Formation at the Antônio Finelon Mine (S 07° 07′ 22.5″ and W 39° 42′ 01″) in Nova Olinda municipality, Ceará State, Brazil (Fig. 1). The quarry’s surface was divided into 5.0 m2 × 2.0 m2 quadrants and was excavated until the base of the Formation, in total, three meters in depth (Figs. 2 and 3). A sequence number was attributed on a field form for all collected fossils, and the following information was assessed: the place of the collection (distance from the top of the excavation); type of fossil (to the least inclusive taxonomic group possible); integrity (complete, incomplete or fragment); preservation type (compressed, impression, or 3D); fossil length (cm); fossil width (cm); fossil orientation (azimuth) and other observations of interest (such as sedimentological). The collected fossils were deposited in the Paleontological Collection of URCA (LPU) in Crato municipality, and the Museu de Paleontologia Plácido Cidade Nuvens (MPPCN) in Santana do Cariri municipality, both in Ceará State, Brazil.

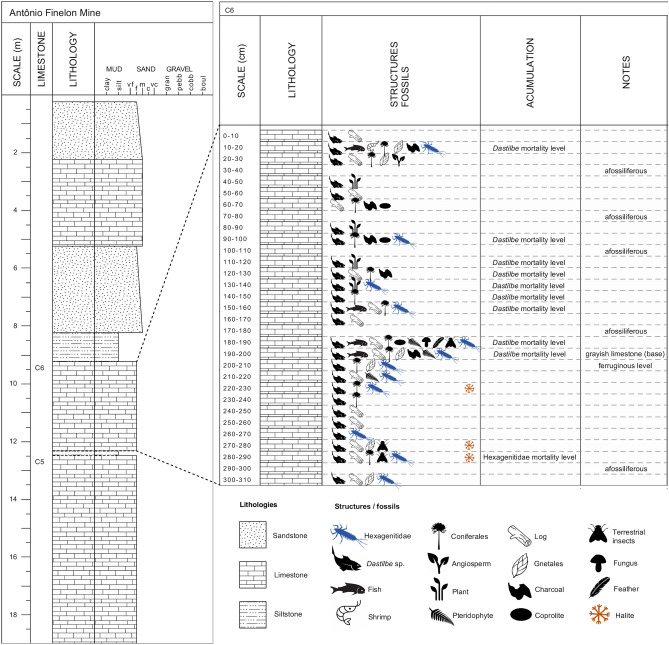

Figure 1.

Locality map. Antônio Finelon Mine, Nova Olinda municipality, Ceará State, Brazil. Outcrops of the Crato Formation and of the Araripe Basin are also indicated.

Figure 2.

Excavation profile of an outcrop of the Crato Formation. Antônio Finelon Mine, Nova Olinda municipality, Ceará State, Brazil. On the right, the section excavated of 3.10 m in depth, at level C6, evidencing the lithostratigraphic position of the fossil assemblage and levels with fossil accumulation.

Figure 3.

Photograph of the controlled excavations at Antônio Finelon Mine. Nova Olinda municipality, Ceará State, Brazil.

Results

Mayflies' mass mortality layer

A layer collected at 285 cm from the top of the Formation, belonging to top-level carbonate C6 sensu Neumann and Cabrera19 and composed of yellowish limestone, presented evidence of at least one mass mortality event, with 40 mayflies’ larvae recovered over 5.0 × 2.0 m2. Its over and underlying layers, at 274.5 and 288 cm, respectively, presented halite crystals and pseudomorphs (Fig. 4). The only other autochthonous taxon observed at the 285 cm level was 18 specimens of the gonorynchiform fish Dastilbe.

Figure 4.

Halite crystals. Halite crystals recovered from layer 288 cm. White arrows point to crystals. Scale bar 20 mm.

All mayflies’ larvae from that level belong to the extinct family Hexagenitidae and could be identified as a monospecific assemblage of Protoligoneuria limai Demoulin, 1955 due to the diagnostic enlarged seventh gill21. Martins-Neto9 classified Protoligoneuria larvae into ontogenetic categories: specimens with a body length between 0.1 and 1 cm as young and larvae up to 1.2–1.6 cm as mature. The body length of the specimens recovered from this level is consistent with the former (Supplementary Table S1). At the 285 cm layer, the larvae are mostly young, evidenced by the wing pad’s absence; therefore, this accumulation represents a selective death22. When the adults emerge en-masse, a mass mortality event can occur23, but it was probably not this case, since most larvae were not mature enough to moult into adulthood.

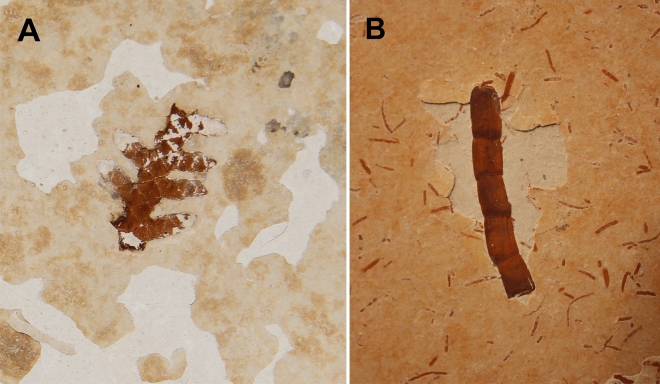

These larvae have excellent preservation with all specimens complete (head, thorax, abdomen, gills, and cerci preserved—Fig. 5). Also, there is no preferential orientation in the samples suggesting a lack of, or little, transport. The Dastilbe individuals from the same level are also smaller than those found in other levels: while they can reach up to 21 cm in length10, at the layer 285 cm, the largest one measures 5 cm (Fig. 6), with most of them measuring only 1.5 cm. They are also complete and without preferential orientation.

Figure 5.

Preservation of larvae from layer 285 cm. Larvae of Protoligoneuria limai recovered from layer 285 cm, evidencing the excellent preservation of specimens. Scale bar 5 mm.

Figure 6.

Gonorynchiform fish Dastilbe. (A) Dastilbe specimen recovered at level 205 cm. Scale bar: 25 mm; (B) One of the smallest Dastilbe specimens recovered at level 285 cm. Scale bar: 5 mm; (C) A layer with several Dastilbe specimens (inside the blue circles) with preferential orientation. The values written next to the fossils refer to the azimuth.

Individuals belonging to allochthonous taxa that were recovered at the 285 cm layer include plants (complete Brachyphyllum obesum Heer, 1881 leaves, one Araucaria sp. seed, an incomplete gymnosperm leaf, one Duartenia araripensis Mohr et al., 2012 trunk, and one incomplete Pseudofrenelopsis sp. branch) and terrestrial insects (an incomplete Orthoptera individual, a complete Hemiptera individual, and a complete Blattaria wing) (Fig. 2), all of them also without preferential orientation.

Most of the layers in which Ephemeroptera larvae were found during the controlled excavations presented few individuals, such as one or two. Eighteen larvae were recovered from a layer 180.4 cm from the top of the Formation. However, most individuals had preferential orientation (Supplementary Fig. S1), so this aggregation was probably caused by transport. Also, the number of preserved specimens at this layer was much smaller than that of layer 285 cm.

Biological community at the controlled excavation

The fossil assemblage of the excavated profile exhibits several groups: plants such as angiosperms (Iara sp. and Choffatia sp.), gymnosperms (Araucaria sp.; Brachyphyllum sp.; Brachyphyllum obesum; Duartenia sp.; Duartenia araripensis; Frenelopsis sp.; Ginkgo sp.; Lindleycladus sp.; Podozamites sp.; Pseudofrenelopsis sp.; Welwitschia sp.), and pteridophytes (Ruffordia goeppertii Mohr et al., 2007), as well as indeterminate plant logs, charcoal and fungi. Among the fauna, the following groups were recovered: insects (Blattodea/Blattaria and Isoptera; Diptera; Ephemeroptera; Hemiptera; Hymenoptera; Orthoptera), fishes (Dastilbe sp., and Cladocyclus sp., as well as several unidentified specimens), unidentified shrimps, ichnofossils and feathers.

The most common taxon recovered was the fish Dastilbe, representing 79% of all specimens collected during the excavation. The Hexagenitidae larvae came second, with 5% (no adult hexagenitid was recovered). The remaining 16% were plants, coprolites, ichnofossils, and other arthropods and fishes. Mayflies' larvae constituted 85% of the total number of insect specimens excavated.

Almost all recovered Dastilbe specimens were juveniles. Fish from other taxa and Dastilbe in other ontogenetic stages are present, but are fewer, mainly disarticulated or represented by isolated parts (such as operculum and scales).

In this controlled excavation, there is low species richness in some layers, while in other layers, interchangeably, there is a higher species richness in the assemblage. The richness peaks mostly occur at the frequent Dastilbe mass mortality layers (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Although the local abundance of fossils of a single taxon on a single bedding plane is suggestive of mass mortality24, such a conclusion can be reached only when time-averaging processes are discarded as influencers12. If on the same bedding plane the taphonomical signatures differ among fossils, as reported to the Green River Formation25, then time-averaging is a possible factor for the accumulation. As the analysed taphonomic signatures of all autochthonous individuals of the layer 285 cm are similar and their remains are articulated, we suggest that the mayflies' individuals died simultaneously, representing a mass mortality event.

It is crucial to perform excavations with stratigraphic control to determine whether mass mortality events are extraordinary taphonomic modes within a unit or whether they are more common. Our controlled excavations (Fig. 2) show that, in the Crato Formation, mayfly mass mortality events were rare, though the abundant Dastilbe fishes are frequently found in accumulations suggestive of mass mortalities.

There is compelling morphological and taphonomic evidence that hexagenitid larvae were well adapted to standing waters. They have a minnow-like body with posterolateral abdominal processes, lamellar gills with a thickened outer margin and a thickened rib near the posterior margin, slender, weak legs, short claws, and strongly pubescent swimming caudal filaments26,27, besides heads that are spherical or oval in dorsal view, and hypognathous in lateral view28. Overall, they are very similar to the general appearance of the extant family Siphlonuridae26, which inhabits all kinds of aquatic habitats, like lakes, ponds, rivers, swamps, and streams' vegetations29. In siphlonurids, minnow-like swimming caudal filaments, as occur in hexagenitids, are associated with quiet-water habitats, and short claws are associated with either quiet waters or habitats with solid rather than fine substrates26. Meshkova27 concluded that the presence of leaf-shaped gills, weak legs (not adapted for burrowing), and strongly pubescent caudal filaments of the larvae of the hexagenitid Ephemeropsis indicated that they had inhabited standing waters. In fact, all hexagenitids from Laurasia have been considered lacustrine11. Martins-Neto9 described the habitat of several species of Hexagenitidae as consisting of silty and sandy bottoms with running and shallow water or stagnant shallow water within vegetated lakes. Tshernova30 and McCafferty26 hypothesized quiet waters as a habitat for Protoligoneuria limai because of its larval swimming adaptations. It is, therefore, likely that the Crato Formation hexagenitids occurred in quiet waters.

The Hexagenitidae and Dastilbe individuals found at layer 285 cm are characterized by excellent preservation with relatively intact specimens. Any transport would have consequences regarding the completeness of morphological elements8. Moreover, there is no preferential orientation in the samples; therefore, any transport involving currents or waves is discarded. Braz31, studying impressions of the Crato Formation angiosperms, observed that most of the fossils had little fragmentation and concluded that the deposition occurred in a shallow lake environment with little or no transport. Without the action of water transport, the large accumulation verified by us was probably not random but episodic, and such quality of preservation demands a minimal transport distance32, agreeing with the hypothesis of an autochthonous fauna.

Exceptional preservation often requires a fast burial caused by an abrupt catastrophic event, in addition to a reduction in oxygenation22. Carcasses must also stay far from predators and scavengers to avoid their removal from within the sediment33. Moreover, microbially induced sedimentary structures (MISS) could also be important for the preservation of soft tissues34. At layer 285 cm, it is possible that the burial of specimens was not due to high sedimentation rates35, considering the small size of the Dastilbe fishes and Hexagenitidae larvae, which would require a minor sediment cover. In this case, a rapid overgrowth of benthic microbial mats would be enough34. Structures similar to MISS were already reported for the Crato Formation; however, they were isolated and without stratigraphic data5. Iniesto et al.36 ran experiments with extant larvae of Coleoptera and microbial mats and, by comparison, showed that grylloids from the Crato Formation had a pattern of preservation consistent with the presence of microbial mats. The latter only occurs in specific situations, such as restricted hypersaline lacustrine settings, shallow water tanks, and in organisms that are rich in lipids, such as insect larvae9,36,37.

Based on the fossils found in layer 285 cm, the Hexagenitidae were the main taxon of autochthonous arthropods that managed to survive longer during times of environmental stresses. These larvae are smaller than those found in other levels, suggesting an episode when the water column was so low that they could not moult to reach larval maturity. Younger individuals could support lower water levels due to their small sizes, as in the early stages their body is only 0.1 cm21. Furthermore, Kluge38 points out that mayflies that develop in warmer waters are smaller than those that live in colder waters. Camp et al.39 suggested that the climate change and other stressors may make moulting more challenging, since respiratory harms will become more severe at higher temperatures. These authors demonstrated that in the 3–4 hours before moulting, larvae consume 41% more oxygen than normal, and oxygen consumption becomes more extreme at higher temperatures39. Thus, given that the larvae spend more oxygen during the moult, this task would be more challenging in a shallow water column, where the oxygen rates are already low13. Similarly, we can rule out a post-moult accumulation of mayflies’ exoskeletons, because in the 285 cm layer all larvae are young individuals. It is unlikely that they were mature enough to moult, considering their small sizes and a lack of wing pads38. The smaller sizes of the Dastilbe individuals found in layer 285 cm are consistent with a shallower water column episode.

Gymnosperms constitute the dominant and most diverse group of plants in the Crato palaeoflora, especially the Coniferales40. At layer 285 cm, the Coniferales possess xerophytic characters, such as reduced and compressed leaves in Brachyphyllum obesum and Pseudofrenelopsis41 (Fig. 7), as well as thick cuticles, papillae, stomata immersed in the epidermis, and the twisted cauline growth in Duartenia araripensis42. Their preferred habitat would be coastal, riparian, or marshy sandy regions of saline or brackish water bodies43. The presence of Araucaria is also related to drier weather conditions44. These adaptations to a semi-arid to arid climate support a scenario of significant evaporation at the Crato Formation45, a condition under which these plants and the dominant faunas of the palaeolake probably dwelled cyclically46.

Figure 7.

Brachyphyllum sp. and Pseudofrenelopsis sp. (A) Brachyphyllum sp. recovered from the controlled excavation; (B) Pseudofrenelopsis sp. recovered from the controlled excavation.

Over and underlying layers of the mortality level presented crystals and pseudomorphs of halite (NaCl) and lacked fossils of mayflies. Halite forms due to the dissolution of a primary salt precipitate47 and its presence could indicate that, with the decrease of the water volume, the salinity of the lake increased and salts precipitated48. Macro-invertebrates are considered sensitive indicators of water quality49, and their use for that end has long been recognized as effective50. Many studies have shown a wide variation in the salinity tolerances of different macro-invertebrate taxa51–54. Extant species of mayflies are generally halophobic, and only a few species are reported to tolerate elevated salt concentrations as present in brackish water55. Even small increases in salinity will result in the loss of sensitive species56 and can lead to salt-tolerant biota gain57. Although many taxa may survive at elevated salt concentrations, chronic exposure to increased salinity may significantly reduce juveniles’ recruitment and growth, and the taxa’s reproductive capability57,58. The increase of salinity could be a causative agent for the mass mortality of the larvae recovered at level 285 cm, though not necessarily for the Dastilbe individuals. Unlike the mayflies’ larvae, modern gonorynchiform fishes (e.g., the 'milkfish' Chanos chanos (Forsskål, 1775)) are anadromous and can tolerate varying salinities59,60.

Other hypotheses for the death of these mayflies’ larvae are anoxia, temperature and salinization shifts, desiccation, or a combination of factors. Natural modern-day mass mortalities are regular in restricted basins and occur seasonally during dry periods when the surface water temperatures rise, causing salinity oscillation48. Sudden turbidity caused by earthquakes or storms cannot be ruled out as causative of layer 285 cm’s mass mortality. However, although seismic events have been proposed for parts of the Araripe Basin due to the presence of wet sediment deformation structures5, we have not observed these in the analyzed horizon. Similarly, storm events were reportedly frequent in the Crato Formation due to the presence of storm-damaged plant fragments47. Nevertheless, no sedimentological structures compatible with storm events, such tempestites, were seen on the mass mortality layer.

There are a few Lagerstätten whose mayfly fauna can be compared with the Crato Formation, such as the Green River Formation from the Early to Middle Eocene of north-western Colorado and south-western Wyoming, USA25; the Koonwarra fossil beds of the Wonthaggi Formation from the Lower Cretaceous of Australia61; the Solnhofen beds from the Late Jurassic of Germany62; and the Yixian Formation of the lowermost Jehol Group from the Lower Cretaceous of China63. The Green River Formation was formed under a temperate to sub-tropical lacustrine setting64. The absence of benthic organisms is implied by the lack of bioturbation on the sediment25, but there is evidence of microbial mats and a limited nekton64. Unfortunately, only its fish have been analyzed taphonomically64. The exceptional preservation of the Green River fish fossils was associated in the past with rapid burial65, but recent studies state that the carcasses were progressively buried, due to the ‘half and half’ preservation of fishes (only half of the fish is exceptionally preserved)64, thus differing from the Crato Formation. Mass mortality events of fishes are also recorded in the Green River Formation, but are limited to few laminae25 suggesting that these events were fortuitous and not cyclical as in the Crato paleolake.

The Koonwarra fossil beds represent a freshwater lacustrine or fluvial environment61 that had an abundant and diverse insect fauna61,66. Although Hemiptera and Coleoptera are the most diverse orders at the unit, the fauna is dominated by aquatic larvae of Ephemeroptera and Diptera61 belonging to taxa typical of temperate environments, unlike the tropical Hexagenitidae of the Crato Formation. The preservation of the Koonwarra insects has been extensively discussed, and at first, it was believed that they were preserved in a shallow lake during cold periods, in which the shallower lake portions were isolated by ice and became anoxic61,67. Nowadays, it is accepted that, actually, there was a deep lake with a stratified water column66,67. Both deposits represent a deep stratified lake, however, there is no evidence of a marine influence or microbial mat in the Koonwarra fossil beds23,68. Mass mortality of fishes occurred periodically in the Koonwarra beds69, but the events that affected the fish community may not have disturbed the invertebrates61, given that no mass mortality has been reported yet for any invertebrate group. The bottom dwelling larvae of Australurus plexus Jell and Duncan, 1986 (Ephemeroptera: Siphlonuridae) were considered a common species part of the autochthonous fauna of the Koonwarra beds61, as Protoligoneuria limai in the Crato Formation. However, unlike the hexagenitids, Siphlonuridae is typical of cool mountain streams and lakes70, so the habitat of the Koonwarra depositional site might have been different of that of Crato.

The Solnhofen limestones represent a marine or semi-marine past environment71, unlike the Crato Formation that was formed under a lacustrine environment72. However, both units have similar modes of mineralization and preservation of fossils73. The insects of the Solnhofen beds have been extensively examined, but mainly restricted to taxonomic studies. The Solnhofen entomofauna presents adult Odonata as their most numerous insects, but their larvae have not been found, likely due to the hypersaline paleoenvironment62. Mayflies are numerous as well, but only as adults62. However, because these adults usually are not able to fly long distances74, they were probably buried close to the original freshwater habitat of their larvae.

One of the most species-rich Mesozoic Lagerstätte is the Yixian Formation75. Its deposits are known for the exceptional preservation of fossils, due to periodic anoxia, volcanic input, and rapid burial76. As seen in the Crato Formation, cyclical mass mortality events of fishes are present77. In the Yixian Formation, the main cause was periodic anoxia in the coldest seasons, with re-oxygenation in warmer seasons77. Pan et al.78, analyzing the Ephemeropsis trisetalis Eichwald, 1864 (Hexagenitidae) collected under stratigraphically controlled excavations, found that this group is one of the most abundant in the Jehol Biota (the vast majority as larvae). E. trisetalis occurs in various preservational states, but most specimens are fully articulated78. Biostratinomic and paleoecological studies of E. trisetalis larvae indicate that they were autochthonous and preserved under low energy conditions77,78, like P. limai in the Crato Formation.

In our controlled excavation, Dastilbe were often found in mass mortality events, agreeing with a scenario in which such mortality events were cyclical12. The Crato Formation probably acted as a nursery for this species, with the adults migrating to reproduce60, as virtually all specimens recovered were juvenile. It is possible that these juveniles were the only fish continually at the paleolake at the analysed area60, since fish from other taxa and Dastilbe in other ontogenetic stages are rarer, and mainly disarticulated or representing isolated parts, and could represent carcasses that were transported into the excavated locality.

Previously, mayflies were pointed out by Menon and Martill8 as constituting around 14%–24% (adults and larvae) of the total insect diversity of the Crato Formation, unlike Bechly72 that previously have reported only 7%. We found in this controlled excavation that mayflies' larvae constituted 85% of the total number of insect specimens excavated. These low percentages previously found are probably due to taxonomically biased collections and/or absence of excavations with stratigraphic control.

Conclusions

According to Martins-Neto9,13, at least one group of insects experienced mass mortality episodes in the Crato palaeolake: Hexagenitidae larvae. There is robust evidence to consider the assemblage at layer 285 cm as such. The palaeoenvironment of the Crato palaeolake was subject to constant shifts in salinity, water depth, and degree of oxygenation, and this likely seasonal phenomenon of high evaporation46, probably caused by the hot climate tending to aridity, could have caused stress on the aquatic animals, as already pointed out by several authors47,79–84. Such environmental scenario possibly resulted in this punctual mass mortality. Notwithstanding, a more detailed analysis of environmental proxies is urgent to interpret biological crises in the Araripe Basin better. Excavations with stratigraphic control at the Crato Formation provide essential data to understand major tendencies in its ancient biological community. The dominant taxon found in the controlled excavation was the gonorynchiform fish Dastilbe, followed by the Hexagenitidae larvae, representing the best candidates for quantitative studies in the Crato Formation. As mayfly fossils represent part of the lake’s autochthonous fauna, data collected from them, along with palaeoclimatic, sedimentological, and biological observations, can be used to understand the palaeoenvironmental context of this unit better.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Zhong-Qiang Chen for the helpful contributions. We are grateful to Lucio Silva for receiving us at the Museu de Paleontologia Plácido Cidade Nuvens, in Santana do Cariri. We also thank Dr. Hermínio Ismael de Araújo Júnior for valuable comments on an earlier version. This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001, by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq)—312360/2018-5 to TR and 305705/2019-9 to FJL, and by the Fundação Cearense de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico—FUNCAP under Grant BP3-013900202.01.00/18 to AAFS, BMD-0124-00302.01.01/19 to RAMB and SPU: 9871903/2018 to FJL.

Author contributions

R.A.M.B., F.J.L., and A.A.F.S. carried out the fieldwork; A.P.S., T.R., and A.A.F.S. conceived the study; R.A.M.B., F.J.L., and A.A.F.S. administrated the data collection; A.P.S. and T.R. administrated the project; A.P.S. conducted lab work and investigation; A.P.S. wrote the manuscript; A.P.S., T.R., R.A.M.B., F.J.L. and A.A.F.S. discussed the results and revised the manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its “Supplementary Information” files).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-85953-5.

References

- 1.Neumann VH, Borrego AG, Cabrera L, Dino R. Organic matter composition and distribution through the Aptian-Albian lacustrine sequences of the Araripe Basin, northeastern Brazil. Int. J. Coal. Geol. 2003;54:21–40. doi: 10.1016/S0166-5162(03)00018-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heimhofer U, Martill DM. Stratigraphy of the Crato Formation. In: Martill DM, Bechly G, Loveridge RF, editors. The Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumann VHML. Estratigrafía, sedimentología, geoquímica y diagénesis de los sistemas lacustres Aptienses-Albienses de la Cuenca de Araripe (Noreste de Brasil) Universidad de Barcelona; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martill DM. The geology of the Crato Formation. In: Martill DM, Bechly G, Loveridge RF, editors. The Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 8–24. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martill DM, Wilby PR. Stratigraphy. In: Martill DM, editor. Fossils of the Santana and Crato Formations, Brazil. The Palaeontological Association Field Guides to Fossils; 1993. pp. 20–50. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heimhofer U, et al. Deciphering the depositional environment of the laminated Crato fossil beds (Early Cretaceous, Araripe Basin, North-eastern Brazil) Sedimentology. 2010;57(2):677–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3091.2009.01114.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martínez-Delclòs X, Briggs DEG, Peñalver E. Taphonomy of insects in carbonates and amber. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2004;203:19–64. doi: 10.1016/S0031-0182(03)00643-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menon F, Martill DM. Taphonomy and preservation of Crato Formation arthropods. In: Martill DM, Bechly G, Loveridge RF, editors. The Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martins-Neto RG. New mayflies (Insecta, Ephemeroptera) from the Santana Formation (Lower Cretaceous), Araripe Basin, northeastern Brazil. Rev. Esp. Paleontol. 1996;11(2):177–192. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brito PM. The Crato Formation fish fauna. In: Martill DM, Bechly G, Loveridge RF, editors. The Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an ancient world. Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 429–443. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinitshenkova ND. The Mesozoic mayflies (Ephemeroptera) with special reference to their ecology. In: Landa V, Soldan T, Tonner M, editors. 4th International Conference of Ephemeroptera. Czechoslovak Academy of Science; 1984. pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martill DM, Brito PM, Washington-Evans J. Mass mortality of fishes in the Santana Formation (Lower Cretaceous, Albian) of northeast Brazil. Cretac. Res. 2008;29(4):649–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cretres.2008.01.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martins-Neto RG. Insetos fósseis como bioindicadores em depósitos sedimentares: um estudo de caso para o Cretáceo da Bacia do Araripe (Brasil) Rev. Bras. Zoociências. 2006;8(2):155–183. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bechly G, et al. A revision and phylogenetic study of Mesozoic Aeshnoptera, with description of several new families, genera and species (Insecta: Odonata: Anisoptera) Neue Paläontologische Abhandlungen. 2001;4:1–219. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martins-Neto RG, Gallego OF. Death behaviour”—Thanatoethology, new term and concept: A taphonomic analysis providing possible paleoethologic inferences. Special cases from arthropods of the santana formation (Lower Cretaceous, Northeast Brazil) Geociências. 2006;25(2):241–254. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osés GL, et al. Deciphering the preservation of fossil insects: A case study from the Crato Member, Early Cretaceous of Brazil. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2756. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saraiva AAF, Hessel MH, Guerra NC, Fara E. Concreções Calcárias da Formação Santana, Bacia do Araripe: uma proposta de classificação. Estud. Geol. 2007;17(1):40–58. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Assine ML. Bacia do Araripe. Boletim de Geociências da Petrobras. 2007;15(2):371–389. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuckartz U, Kuckartz U. Una nueva propuesta estratigráfica para la tectonosecuencia post-rifte de la cuenca de Araripe, nordeste de Brasil. Boletim do 5° Simpósio sobre o Cretáceo do Brasil; 1999. pp. 279–285. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viana MS, Neumann VHL. Membro Crato da Formação Santana, Chapada do Araripe, CE-Riquíssimo registro de fauna e flora do Cretáceo. In: Schobbenhaus C, Campos DA, Queiroz ET, Winge M, Berbert-Born MLC, editors. Sítios Geológicos e Paleontológicos do Brasil. Comissão Brasileira de Sítios Geológicos e Paleobiológicos; 2002. pp. 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staniczek AH. Ephemeroptera: Mayflies. In: Martill DM, Bechly G, Loveridge RF, editors. The Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Datta D, Mukherjee D, Ray S. Taphonomic signatures of a new Upper Triassic phytosaur (Diapsida, Archosauria) bonebed from India: Aggregation of a juvenile-dominated paleocommunity. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2020;39(6):e1726361. doi: 10.1080/02724634.2019.1726361. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barling N. The Fidelity of Preservation of Insects from the Crato Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of Brazil. University of Portsmouth; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boucot AJ. Evolutionary Paleobiology of Behavior and Coevolution. Elsevier; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grande L. Palaeontology of the Green River Formation, with a Review of the Fish Fauna. 2. Geological Survey of Wyoming Bulletin; 1984. pp. 1–333. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCafferty WP. Chapter 2. Ephemeroptera. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1990;195:20–50. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meshkova NP. On nymph Ephemeropsis trisetalis Eichwald (Insecta) Paleontol. Zh. 1961;4:164–168. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polegatto CM, Zamboni JC. Inferences regarding the feeding behavior and morphoecological patterns of fossil mayfly nymphs (Insecta Ephemeroptera) from the Lower Cretaceous Santana Formation of northeastern Brazil. Acta. Geol. Leopold. 2001;24:145–160. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouchard RW. Guide to Aquatic Macroinvertebrates of the Upper Midwest. University of Minnesota; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tshernova OA. On the classification of Fossil and Recent Ephemeroptera. Entomol. Rev. 1970;49:71–81. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braz FF. Registro angiospérmico Eocretáceo do Membro Crato, Formação Santana, Bacia do Araripe, NE do Brasil: Interpretações paleoambientais, paleoclimáticas e paleofitogeográficas. Universidade de São Paulo; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Archibald SB, Makarkin VN. Tertiary giant lacewings (Neuroptera: Polystoechotidae): Revision and description of new taxa from western North America and Denmark. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 2005;4:1–37. doi: 10.1017/S1477201906001817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyero L, Cardinale BJ, Bastian M, Pearson RG. Biotic vs abiotic control of decomposition: A comparison of the effects of simulated extinctions and changes in temperature. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e87426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gall JC. Les Voiles Microbiens. Leur Contribution à la Fossilisation des Organismes au Corps Mou. Lethaia. 1990;23:21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1502-3931.1990.tb01778.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martill DM. Fish oblique to bedding in early diagenetic concretions from the Cretaceous Santana Formation of Brazil e implications for substrate consistency. Palaeontology. 1997;41:1011–1026. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iniesto M, et al. Soft tissue histology of insect larvae decayed in laboratory experiments using microbial mats: Taphonomic comparison with Cretaceous fossil insects from the exceptionally preserved biota of Araripe, Brazil. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2021;564:110156. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.110156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kok MD, Schouten S, Damsté JSS. Formation of insoluble, nonhydrolyzable, sulfur-rich macromolecules via incorporation of inorganic sulfur species into algal carbohydrates. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2000;64:2689–2699. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(00)00382-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kluge NJ. The Phylogenetic System of Ephemeroptera. Kluwer Academic; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Camp AA, Funk DH, Buchwalter DB. A stressful shortness of breath: Molting disrupts breathing in the mayfly Cloeon dipterum. Freshw. Sci. 2014;33(3):695–699. doi: 10.1086/677899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohr BAR, Bernardes-De-Oliveira MEC, Loveridge RF. The macrophyte flora of the Crato Formation. In: Martill DM, Bechly G, Loveridge RF, editors. The Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 537–565. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kunzmann L, Mohr BAR, Bernardes-De-Oliveira MEC. Gymnosperms from the Early Cretaceous Crato Formation (Brazil). I. Araucariaceae and Lindleycladus (incertae sedis) Foss. Rec. 2004;7:155–174. doi: 10.1002/mmng.20040070109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mohr B, Schultka S, Süss H, Bernardes-De Oliveira MEC. A new drought resistant gymnosperm taxon Duartenia araripensis gen. nov. et sp. nov. (Cheirolepidiaceae?) from the Early Cretaceous of Northern Gondwana. Palaeontogr. Abt. B. 2012;289(1–3):1–25. doi: 10.1127/palb/289/2012/1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bernardes-De-Oliveira MEC, et al. Indicadores Paleoclimáticos na Paleoflora do Crato, final do Aptiano do Gondwana Norocidental. In: Carvalho IS, Garcia MJ, Lana CC, Strohschoen O, et al., editors. Paleontologia: Cenários de Vida-Paleoclimas. Editora Interciência; 2013. pp. 100–118. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kershaw P, Wagstaff B. The Southern Conifer Family Araucariaceae: History, status, and value for paleoenvironmental reconstruction. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2001;32:397–414. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lima FJ, et al. Fire in the paradise: Evidence of repeated palaeo-wildfires from the Araripe Fossil Lagerstätte (Araripe Basin, Aptian-Albian), Northeast Brazil. Palaeobio. Palaeoenv. 2019;99:367–378. doi: 10.1007/s12549-018-0359-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Makarkin VN, Menon F. New species of the Mesochrysopidae (Insecta, Neuroptera) from the Crato Formation of Brazil (Lower Cretaceous), with taxonomic treatment of the family. Cretac. Res. 2005;26:801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.cretres.2005.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martill DM, Loveridge R, Heimhofer U. Halite pseudomorphs in the Crato Formation (Early Cretaceous, Late Aptian-Early Albian), Araripe Basin, northeast Brazil: Further evidence for hypersalinity. Cretac. Res. 2007;28(4):613–620. doi: 10.1016/j.cretres.2006.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams WD. Salinisation: A major threat to water resources in the arid and semi-arid regions of the world. Lakes and Reservoirs. Res. Manag. 1999;4:85–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1770.1999.00089.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clarke RT, Hering D. Errors and uncertainty in bioassessment methods, major results and conclusions from the STAR project and their application using STARBUGS. Hydrobiologia. 2006;566:433–439. doi: 10.1007/s10750-006-0079-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams WD. Salinity tolerances of four species of fish from the Murray-Darling River system. Hydrobiologia. 1991;210:145–160. doi: 10.1007/BF00014328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lancaster J, Scudder GGE. Aquatic Coleoptera and Hemiptera in some Canadian saline lakes: Patterns in community structure. Can. J. Zool. 1987;65(6):1383–1390. doi: 10.1139/z87-218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Metzeling L. Benthic macroinvertebrate community structure in streams of different salinities. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1993;44:335–351. doi: 10.1071/MF9930335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berezina NA. Tolerance of freshwater invertebrates to changes in water salinity. Russ. J. Ecol. 2003;34(4):261–266. doi: 10.1023/A:1024597832095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kefford BJ, Dalton A, Palmer CG, Nugegoda D. The salinity tolerance of eggs and hatchlings of selected aquatic macroinvertebrates in south-east Australia and South Africa. Hydrobiologia. 2004;517(1–3):179–192. doi: 10.1023/B:HYDR.0000027346.06304.bc. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chadwick MA, Hunter H, Feminella JW, Henry RP. Salt and water balance in Hexagenia limbata (Ephemeroptera: Ephemeridae) when exposed to brackish water. Fla. Entomol. 2002;85:650–651. doi: 10.1653/0015-4040(2002)085[0650:SAWBIH]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.James KR, Cant B, Ryan T. Responses of freshwater biota to rising salinity levels and implications for saline water management: A review. Aust. J. Bot. 2003;51(6):703. doi: 10.1071/BT02110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nielsen DL, Brock MA, Rees GN, Baldwin DS. Effects of increasing salinity on freshwater ecosystems in Australia. Aust. J. Bot. 2003;51(6):655–665. doi: 10.1071/BT02115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hart BT, Lake PS, Webb JA, Grace MR. Ecological risk to aquatic systems from salinity increases. Aust. J. Bot. 2003;51(6):689. doi: 10.1071/BT02111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bagarinao T. Systematics, genetics and life history of milkfish, Chanos chanos. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 1994;39:23–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00004752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davis SP, Martill DM. The Gonorynchiform fish Dastilbe from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil. Palaeontology. 2003;42(4):715–740. doi: 10.1111/1475-4983.00094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jell PA, Duncan PM. Invertebrates, mainly insects, from the freshwater, Lower Cretaceous, Koonwarra fossil bed (Korumburra group), South Gippsland, Victoria. In: Jell PA, Roberts J, editors. Plants and invertebrates from the Lower Cretaceous Koonwarra fossil bed, South Gippsland, Victoria. Memoir of the Association of Australasian Palaeontologists; 1986. pp. 111–205. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ponomarenko AG. Fossil insects from the Tithonian ‘Solnhofener Plattenkalke’ in the Museum of Natural History, Vienna. Ann. Naturhist. Mus. Wien. 1985;87:135–144. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang J, Zhang H. Insects and spiders. In: Chang M, Chen P, Wang Y, editors. The Jehol Biota. Shanghai Scientific and Technical Publishers; 2003. pp. 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hellawell J, Orr PJ. Deciphering taphonomic processes in the Eocene Green River Formation of Wyoming. Palaeobiodivers. Palaeoenviron. 2012;93:353–365. doi: 10.1007/s12549-012-0092-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McGrew PO. Taphonomy of Eocene fish from Fossil Basin, Wyoming. Fieldiana Geology. 1975;33:257–270. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krzemiński W, Soszyńska-Maj A, Bashkuev AS, Kopeć K. Revision of the unique Early Cretaceous Mecoptera from Koonwarra (Australia) with description of a new genus and family. Cretac. Res. 2015;52:501–506. doi: 10.1016/j.cretres.2014.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Elder RL, Smith GR. Fish taphonomy and environmental inference in Paleolimnology. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 1988;62:577–592. doi: 10.1016/0031-0182(88)90072-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huang D. Tarwinia australis (Siponaptera: Tarwiniidae) from the Lower Cretaceous Koonwarra fossil bed: Morphological revision and analysis of its evolutionary relationship. Cretac. Res. 2015;52:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.cretres.2014.03.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Waldman M. Fish from the freshwater Lower Cretaceous of Victoria, Australia with comments of the palaeo-environment. Spec. Pap. Palaeontol. 1971;9:1–124. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brittain JE, Sartori M. Ephemeroptera. In: Resh VH, Cardé RT, editors. Encyclopedia of Insects. Academic Press; 2002. pp. 328–334. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bartell KW, Swinburne NHM, Conway-Morris S. Solnhofen: A Study in Mesozoic Palaeontology. Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bechly G. New fossil dragonflies from the Lower Cretaceous Crato Formation of north-east Brazil (Insecta: Odonata) Stuttgarter Beitrage zur Naturkunde. 1998;264:1–66. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fielding S, Martill DM, Naish D. Solnhofen-style soft-tissue preservation in a new species of turtle from the Crato Formation (Early Cretaceous, Aptian) of north-east Brazil. Palaeontology. 2005;48:1301–1310. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2005.00508.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sartori M, Brittain JE. Order Ephemeroptera. In: Thorp J, Rogers DC, editors. Ecology and General Biology: Thorp and Covich's Freshwater Invertebrates. Academic Press; 2015. pp. 873–891. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chang MM, Chen PJ, Wang YQ, Wang Y, Miao DS. The Jehol Fossils: TheEmergence of Feathered Dinosaurs, Beaked Birds and Flowering Plants. Academic Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang X, Sha J. Sedimentary laminations in the lacustrine Jianshangou Bed of the Yixian Formation at Sihetun, western Liaoning, China. Cretac. Res. 2012;36:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cretres.2012.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fürsich FT, Sha J, Jiang B, Pan Y. High resolution palaeoecological and taphonomic analysis of Early Cretaceous lake biota, western Liaoning (NE-China) Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2007;253:434–457. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pan Y, Sha J, Fürsich F. A model for organic fossilization of the Early Cretaceous Jehol Lagerstätte based on the taphonomy of "Ephemeropsis trisetalis". Palaios. 2014;29(7/8):363–377. doi: 10.2110/palo.2013.119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Upchurch GR, Doyle JA. Paleoecology of the conifers Frenelopsis and Pseudofrenelopsis (Cheirolepidiaceae) from the Cretaceous Potomac Group of Maryland and Virginia. In: Romans RC, editor. Geobotany II. Plenum; 1981. pp. 167–202. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maisey JG. A new Clupeomorph fish from the Santana Formation (Albian) of NE Brazil. Am. Mus. Novit. 1993;3076:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Valença MM, Neumann VH, Mabesoone JM. An overview on Callovian-Cenomanian intracratonic basins of northeast Brazil: Onshore stratigraphic record of the opening of the southern Atlantic. Geol. Acta. 2003;1:261–275. doi: 10.1344/105.000001614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barling N, Martill DM, Heads SW, Gallien F. High fidelity preservation of fossil insects from the Crato Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of Brazil. Cretac. Res. 2015;52(B):605–622. doi: 10.1016/j.cretres.2014.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Catto B, Jahnert RJ, Warren LV, Varejão FG, Assine ML. The microbial nature of laminated limestones: lessons from the Upper Aptian, Araripe Basin, Brazil. Sediment. Geol. 2016;341:304–315. doi: 10.1016/j.sedgeo.2016.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Warren LV, et al. Stromatolites from the Aptian Crato Formation, a hypersaline lake system in the Araripe Basin, northeastern Brazil. Facies. 2017;63(3):2016. doi: 10.1007/s10347-016-0484-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its “Supplementary Information” files).