Abstract

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic transmural inflammation of intestinal segments caused by dysregulated interaction between microbiome and gut immune system. Here, we profile, via multiple single-cell technologies, T cells purified from the intestinal epithelium and lamina propria (LP) from terminal ileum resections of adult severe CD cases. We find that intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) contain several unique T cell subsets, including NKp30+γδT cells expressing RORγt and producing IL-26 upon NKp30 engagement. Further analyses comparing tissues from non-inflamed and inflamed regions of patients with CD versus healthy controls show increased activated TH17 but decreased CD8+T, γδT, TFH and Treg cells in inflamed tissues. Similar analyses of LP find increased CD8+, as well as reduced CD4+T cells with an elevated TH17 over Treg/TFH ratio. Our analyses of CD tissues thus suggest a potential link, pending additional validations, between transmural inflammation, reduced IEL γδT cells and altered spatial distribution of IEL and LP T cell subsets.

Subject terms: T cells, Mucosal immunology, Systems analysis, Inflammatory bowel disease

Crohn’s disease results from transmural inflammation in the gut, but analyses of local immune populations are still lacking. Here, the authors show, by combining multiple single-cell approaches, that intraepithelial and lamina propria T cells are heterogenous, show unique phenotypes, and exhibit altered subsets upon inflammation.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) encompasses intermittent chronic inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal tract that significantly impair the quality of life in affected individuals and can result in comorbidities and complications requiring repeated surgery1,2. IBD includes two major subtypes, Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). CD inflammation spans across all layers of the gut, while tissue damage in UC is confined to the mucosa. Both genetic and environmental factors contribute to IBD by generating abnormal interactions between the commensal microbiome and the mucosal immune system that result in uncontrolled intestinal inflammation. The conventional therapy with anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory drugs has been recently integrated with biologicals that can effectively target cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-12 and IL-23, or inflammatory cell recruitment with α4β7 blockers3. However, IBD still poses significant therapeutic challenges.

High-dimensional single-cell profiling approaches, such as single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and mass cytometry, have been recently performed on intestinal specimens from patients with CD or UC and controls. These studies provided unbiased analyses of cell lineages and their functional states in IBD, deconvoluted pathways underlying IBD pathogenesis and supplied biomarkers predicting the course of disease and the response to therapy4–10. While these studies have analyzed whole mucosal biopsies or the lamina propria (LP) selectively, few studies have analyzed intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) purified from CD specimens. IEL comprise a quite diverse and complex repertoire of TCRαβ+ and TCRγδ+ T cells11,12, which are strategically located at the interphase between the luminal environment and the intestinal barrier, contributing to intestinal homeostasis and mucosal protection13,14.

Here, we examine T cells from 90 intestinal specimens of CD and controls by either scRNA-seq, multi-parameter flow cytometry or CyTOF, with CD specimens derived from surgical resections of the terminal ileum of adult patients with severe CD. Comparing IEL T cell profiles with those of T cells purified from the LP, our data not only provide an unbiased view of T cell lineages diversity and functional states in the intestinal mucosa under both healthy and CD conditions, but also identify an altered spatial distribution of T cell subsets between the IEL and the LP compartments that potentially correlates with transmural inflammation, although this remains to be validated with larger patient cohorts.

Results

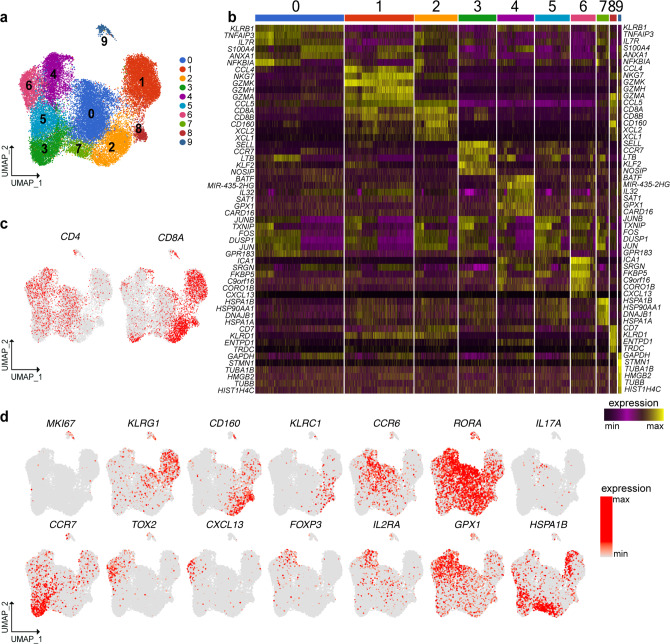

scRNA-seq analysis identifies multiple IEL T cell subsets

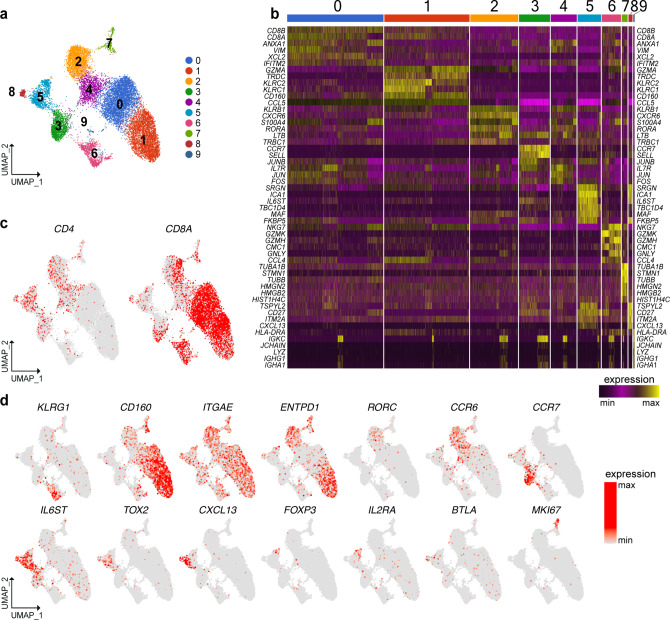

IEL were prepared from surgical resections of the terminal ileum of CD patients, which included both macroscopically inflamed tissue (II) and adjacent non-inflamed tissue (NI) (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c). Most CD cases required surgical treatment because of severity and resistance to medical therapy (patient information: Supplementary Data 1–3). Ileal resections from patients undergoing surgery for colonic polyposis or cancer were used as controls. In an initial survey, we defined the baseline heterogeneity of IEL T cells by scRNA-seq of about 15,000 cells sorted from two CD patients and two controls (sorting strategy Supplementary Fig. 1d). Unsupervised clustering by UMAP of gene expression data from both CD and control samples identified ten cell clusters (Fig. 1a, b). Differential expression of marker genes was used to annotate the different cell types and states. Three T cell clusters expressed CD8A (0, 1, and 6) and five expressed CD4 (2, 3, 4, 5, and 8) (Fig. 1c). Among the CD8+ clusters, cluster 6 expressed genes indicating a canonical effector phenotype, including KLRG1 (Fig. 1d), GZMB, GZMK, PRF1, IFNG, and FCRL6 (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). Cluster 6 also expressed high level of KLF2 (Supplementary Fig. 2c), a transcription factor that promotes lymphocytes circulation15. In contrast, cluster 1 and cluster 0 shared expression of ITGAE, the receptor for E-cadherin, which is indicative of tissue residency16, and CD160, a receptor for HVEM expressed on epithelial cells17 (Fig. 1d). Expression of ENTPD1, which encodes the activation marker CD39, distinguished cluster 1 from cluster 0 (Fig. 1d). The expression of γδTCR, NK cell receptors, cytotoxic mediators, and chemokines (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b) in a subset of cells within these two clusters suggested that additional subpopulations may be present (see below).

Fig. 1. scRNA-seq of IEL T cells identifies discrete subsets of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

a Unsupervised UMAP analysis of IEL T cell clusters. T cells were pooled from two controls and two CD patients (8822 cells control, 6909 cells CD). b Heat map displaying the top ten differentially expressed genes in each cell cluster. c Identification of CD4 and CD8A expressing cells. d UMAP of representative selected genes associated with the identified clusters.

Within CD4+ cells, clusters 2 and 4 showed a TH17 transcriptional profile, featuring RORC, CCR6 (Fig. 1d), RORA, LTB, CCL20, and KLRB1 (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). Both subsets expressed CD40LG (Supplementary Fig. 2b), which sustains TH17 differentiation in vitro and in vivo18. Moreover, cluster 2 expressed genes indicative of immediate effector function, including (a) cytokine genes IL17A and IL26 (Supplementary Fig. 2a); (b) IL23R, which endows responsiveness to IL-23 (Supplementary Fig. 2b); (c) ENTPD1 (Fig. 1d); (d) CXCR6 (Supplementary Fig. 2b), which promotes retention in the intestinal epithelium19; (e) CCL4 and GZMB (Supplementary Fig. 2a), known mediators of TH17 pathogenicity20. Cells in cluster 3 corresponded to naïve CD4+ T cells expressing CCR7 (Fig. 1d), SELL, TCF7, LEF1, as well as KLF2 (Supplementary Fig. 2b, c). This cluster also contained a few naïve CD8+ T cells. Clusters 5 and 8 were enriched for genes related to TFH and Treg lineages. These genes encoded cell surface receptors, such as IL6ST (for GP130) (Fig. 1d), PDCD1 (for PD-1), TIGIT, ICOS, TNFRSF4 (for OX40), and IL6R (Supplementary Fig. 2b), as well as transcription factors, such as TOX2 (Fig. 1d), MAF and BATF (Supplementary Fig. 2c). The left portion of cluster 5 expressed CXCL13 (Fig. 1d), BCL6 and CXCR5 (Supplementary Fig. 2b, c), pointing to a TFH phenotype. The right portion of cluster 5 expressed the Treg markers FOXP3, IL2RA, ENTPD1 (Fig. 1d), CTLA4, and IL10 (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). In addition, the Treg side of cluster 5 expressed PRDM1 (Supplementary Fig. 2b), which facilitates Treg over TFH differentiation21. Cluster 8 uniquely expressed BTLA (Fig. 1d) and CD200 (Supplementary Fig. 2b), which are markers of terminal TFH differentiation22. Cluster 7 included CD4 and CD8 MKI67+ proliferating cells (Fig. 1c, d), while cluster 9 (Fig. 1b) represented a small B cell contamination. Altogether, our survey of human IEL compartment shows the presence of circulating and resident CD8+ T cell subsets, as well as CD4+ T cell subsets belonging to the TH17, TFH, and Treg lineages.

Flow cytometry of IEL corroborates T cell diversity

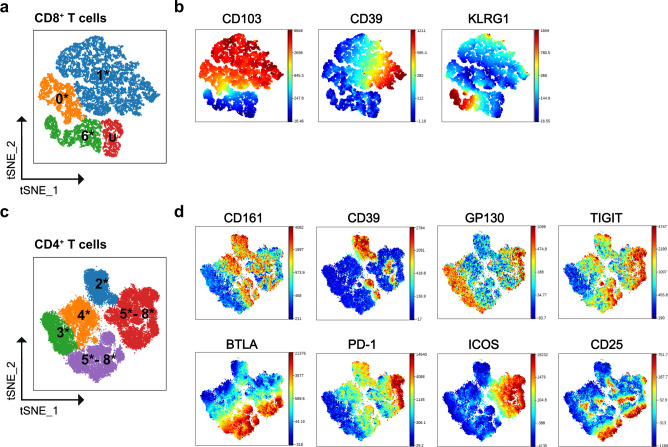

To validate scRNA-seq data we analyzed IEL of CD and control patients by flow cytometry (gating strategy: Supplementary Fig. 3a, b; patient information Supplementary Data 4). Cells were clustered using viSNE analysis in Cytobank. To facilitate comparison of flow cytometry with scRNA-seq data, t-SNE clusters were labeled with the same numbers of the corresponding scRNA-seq cluster followed by an asterisk. We adopted CD103 as a marker of tissue-resident CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2a, b). Most CD103– non-resident cells expressed KLRG1+ (cluster 6*) (Fig. 2b), consistent with the KLRG1+ T effector cells identified by scRNA-seq (cluster 6) (see Fig. 1d). CD103+ cells were split into CD39+ and CD39– clusters (1* and 0*), which corresponded to scRNA-seq clusters 1 and 0. Flow cytometry also identified a unique cluster of CD103–KLRG1– cells (U) that lacked all tested markers and thus could not match any subset identified by scRNA-seq (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2. Identification of IEL CD8+ T cell and CD4+ T cell subsets by flow cytometry.

a Schematic t-SNE clustering of IEL CD8+ T cells. Number illustrates the relationship with clusters observed by scRNA-seq. Asterisk illustrates the different experimental approach. U; undefined. b t-SNE clustering of IEL CD8+ T cells from a representative donor showing expression of CD103, CD39, and KLRG1. c Schematic t-SNE clustering of IEL CD4+ T cells. Number illustrates the relationship with clusters observed by scRNA-seq. Asterisk illustrates the different experimental approach. d t-SNE clustering of IEL CD4+ T cells from three representative donors showing expression of CD161, CD39, GP130, TIGIT, BTLA, PD-1, ICOS, and CD25.

Among CD4+ T cells, TH17 were marked by CD161 (Fig. 2c, d) and spanned clusters 2* and 4*, which were distinguished by expression of CD39 (Fig. 2d). Naïve CD4+ T cells (3*) encompassed GP130+TIGIT–BTLA–CD161–CCR6–CCR7+/low cells (Fig. 2d). TFH and Treg formed two large clusters (5–8*) which shared GP130, TIGIT, BTLA, and PD-1 as in scRNA-seq, but differed for ICOS expression (Fig. 2d). The external edges of clusters 5–8* expressed high level of CD25 (Fig. 2d) suggestive of fully differentiated Treg. Overall, flow cytometric data confirmed the presence of three distinct clusters of CD8+ T cells, as well as TH17, TFH, and Treg in the human IEL compartment.

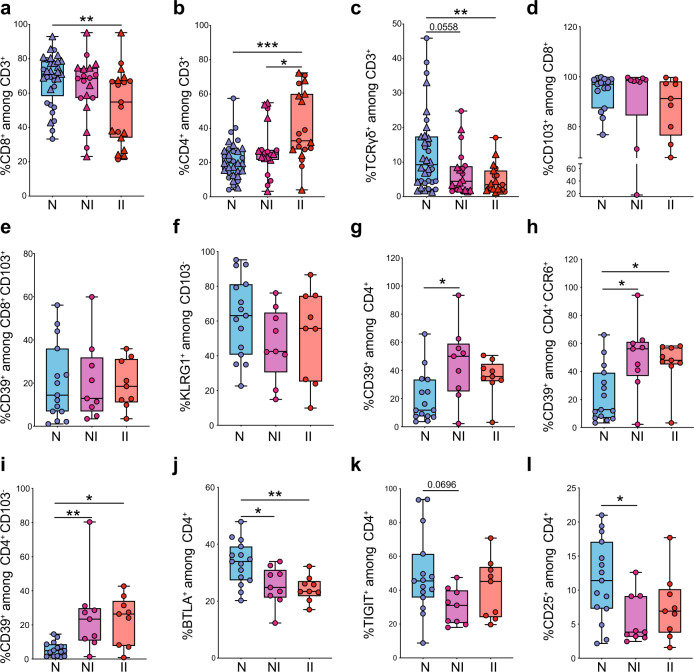

IEL show an aberrant representation of T cell subsets in CD

To examine the impact of CD on IEL T cells, we quantified percentages of CD8+, CD4+, and γδ T cells in a large cohort of patients (Controls: n = 33–34; CD NI: n = 19–20; CD II: n = 19) by flow cytometry (Fig. 3a–c, Supplementary Data 5 and Source Data 1). CD8+ T cells were significantly decreased in CD patients at the inflamed site (Fig. 3a), a finding that was further supported by immunohistochemistry data (Supplementary Fig. 3c–f). CD8+ T cell attrition was paralleled by a significant increase in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3b). In addition, γδ T cells were significantly reduced in the inflamed tissue of CD patients, as compared to controls (Fig. 3c). We further examined whether CD impacted specific T cell subsets in a fraction of the larger cohort of patients described above (Controls: n = 15; CD NI n = 9; CD II n = 9). Quantification of resident CD103+ CD8+ T cells and non-resident CD103–KLRG1+ CD8+ T cells did not reveal major differences between CD and controls (Fig. 3d–f), indicating global rather than subset-specific reduction of CD8+ T cells in CD. In contrast, quantification of different CD4+ T cell clusters showed a significant increase of CD39+CD4+ T cells, CD39+CCR6+ TH17 cells (Fig. 3g, h) and CD39+CD4+ TH17 within the non-resident CD103– population (Fig. 3i) in CD patients, suggesting that these cells may have recently settled into the tissue. In addition, BTLA+ and TIGIT+ CD4+ T cells were decreased in CD patients (Fig. 3j, k), indicating reduced representation of TFH. Finally, we observed a significant decrease in the relative proportion of CD25hi CD4+ T cells in CD, which may correspond to Tregs (Fig. 3l). Altogether, these results suggested that the IEL compartment of CD patients exhibits an aberrant T cell landscape. Notably, some CD-associated alterations were evident in the non-inflamed tissue. The non-inflamed tissue may exhibit early cellular changes reflecting ongoing disease without any macroscopic sign of inflammation and may predict risk of recurring inflammation.

Fig. 3. Quantification of IEL CD8+ T cell, CD4+ T cell subsets and γδ T cells by flow cytometry.

a Percentages of IEL CD8+ among CD3+ T cells in terminal ileum of controls and CD patients. b Percentages of IEL CD4+ among CD3+ T cells in terminal ileum of controls and CD patients. c Percentages of IEL TCRγδ+ among CD3+ T cells in terminal ileum of controls and CD patients. a, b Controls (N), n = 33 (15 frozen, 18 fresh); CD, non-inflamed site (NI), n = 19 (9 frozen, 10 fresh); CD, inflamed site (II), n = 19 (9 frozen, 10 fresh). c Controls (N), n = 34 (16 frozen, 18 fresh); CD, non-inflamed site (NI), n = 20 (10 frozen, 10 fresh); CD, inflamed site (II), n = 19 (9 frozen, 10 fresh). Circles and triangles on the boxplots show data collected for each individual donor. Circles = frozen samples. Triangles = fresh samples. Data were median and interquartile range. d–f Quantification of total CD8+ TRM (d), CD39+ TRM (e), and KLRG1+CD103– (f) T cells among IEL CD8+ from terminal ileum of controls and CD patients. g–l Percentages of CD39+ T cells (g), CD39+ CCR6+ (h), CD39+ CD103– (i), BTLA+ (j), TIGIT+ (k), and CD25hi (l) among IEL CD4+ from terminal ileum of controls and CD patients. d–l controls (N), n = 15; CD, non-inflamed site (NI), n = 9; CD, inflamed site (II), n = 9. Circles on the boxplots show data collected for each individual donor. Circles = frozen samples used in Fig. 3a–c. Data were median and interquartile range. Significance was calculated using an ordinary, one-way ANOVA, multiple comparisons test with Prism v8 software. a **P = 0.0094; b *P = 0.0178, ***P = 0.0001; c **P = 0.0081; g *P = 0.0148; h N vs. NI *P = 0.0134, N vs. II **P = 0.0310; i N vs. NI **P = 0.0079, N vs. II *P = 0.0214; j N vs. NI *P = 0.0204, N vs. II **P = 0.0087; l *P = 0.0315. Source data are provided as a Source Data file (Source Data 1).

Reclustering reveals T cell subsets with unique features

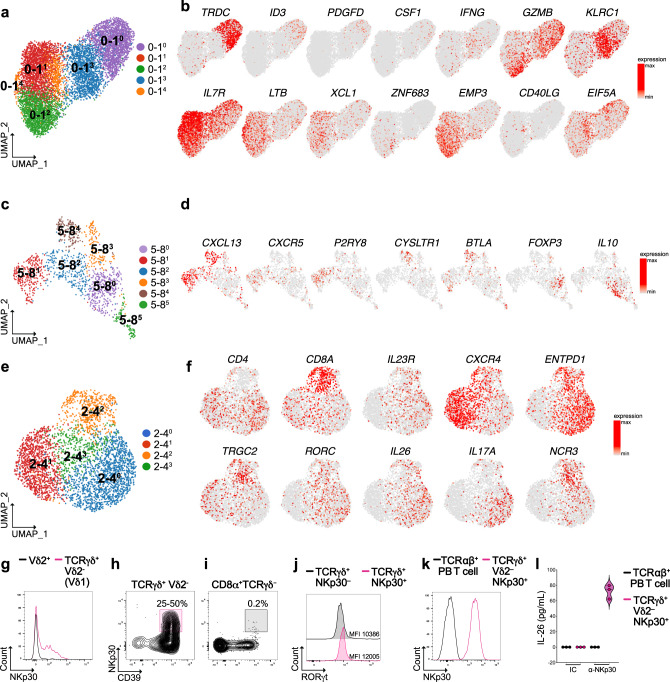

To further dissect T cell heterogeneity within the major IEL populations, we reclustered scRNA-seq data of three pairs of clusters (see Fig. 1a). These included tissue-resident CD8+ T cell clusters 0 and 1 (0–1), the TFH-Treg clusters 5 and 8 (5–8), and the TH17 clusters 2 and 4 (2–4). Subclusters were indicated with a superscript number next to the original cluster pair. The 0–1 cluster pair was resolved into five specialized subsets (Fig. 4a). Cluster 0–10 corresponded to γδ T cells, as indicated by the expression of transcripts for γδTCR (TRDC and TRGC1), as well as the transcription factors ID323 and HOPX (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 4a). These γδ T cells selectively expressed the signaling adapter SH2D1B as well as PDGFD and CSF1. Cluster 0–13 encompassed a CD8+ T cell subset that stood out for production of IFN-γ (IFNG), granzyme B (GZMB), and expression of the NK cell inhibitory receptor KLRC1 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 4a). Both clusters 0–10 and 0–13 shared expression of CD39 (ENTPD1) and several NK cell receptors, including KIR2DL4, KLRC2, KLRD1, and SLAMF7. Cluster 0–11 expressed IL7R, IL2, and TCF7 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 4a), which are indicative of long-lived and memory-like properties24,25, as well as lymphotoxin B (LTB), and the DC attracting chemokines XCL1 and XCL226. Cluster 0–12 expressed the master transcription factor for tissue residency ZNF68327, and markers of cytotoxicity, such as GZMB, PRF1, and TNFSF10 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 4a). As opposed to clusters 0–10 and 0–13, this cluster did not exhibit CD39 or NK cell receptors but expressed the epithelial membrane protein 3 (EMP3) (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 4a). The small cluster 0–14 contained CD8+ T cells marked by CD40LG and a network of p53 regulators, such as EIF5A, MDM4, and SET28 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 4a). CD8+ T cell clusters 0–11, 0–14, and 0–12 produced the S100A family members A4, A6, and A10, which have antimicrobial functions (Supplementary Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4. Reclustering of heterogenous IEL CD8+ and CD4+ T cells populations.

a Unsupervised UMAP reclustering of clusters 0 and 1 from Fig. 1a. b UMAP of representative selected genes associated with the identified clusters. c Unsupervised UMAP reclustering of clusters 5 and 8 from Fig. 1a. d UMAP of representative selected genes associated with the identified clusters. e Unsupervised UMAP reclustering of clusters 2 and 4 from Fig. 1a. f UMAP of representative selected genes associated with the identified clusters. g Overlay expression of NKp30 in Vδ2– (pink) vs. Vδ2+ (black) γδ T cells. h, i Representative flow plots showing the expression of NKp30 in TCRγδ+Vδ2– CD39+ (h) and CD8+TCRγδ–CD39+ (i). T cells in terminal ileum of control patients (one donor representative of nine is shown). j Overlay expression of RORγt in NKp30– (black) vs. NKp30+ γδ T cells (pink). k Overlay expression of NKp30 in peripheral blood TCR αβ+ T cells (black) vs. NKp30+ sorted γδ T cells (pink). l IL-26 production by NKp30+ γδ T cells upon antibody mediated crosslinking of NKp30. MFI mean fluorescence intensity, PB peripheral blood, IC isotype control.

We also re-analyzed the cluster pair 5 and 8 including TFH and Treg. This analysis identified six clusters (Fig. 4c). Clusters 5–81 and 5–84 represented two distinct clusters of TFH, both of which expressed the chemokine CXCL13 and the TFH master transcription factor BCL6 (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 4b). However, 5–81 uniquely expressed CXCR5, TNFSF8, and the G-protein-coupled receptor P2RY829. Conversely, cluster 5–84 expressed CYSLTR130 (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 4b). Cluster 5–84 also expressed BTLA29, as well as unique genes, such as amyloid precursor protein (APP), MS4A6A, and SERPINE2 (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Cluster 5–80 encompassed Treg and contained both FOXP3+ Treg (right side), as well as LAG3+ Tr1 producing IL-10 (left side)30. Cluster 5–82 was located between Treg and TFH, shared expression of PRDM1 with Treg, but showed residual expression of CXCR5 and CXCL13; this subset may reflect a TFH-Treg plasticity reported both in human and mouse31. Cluster 5–83 encompassed cells expressing the γδTCR transcripts TRCG1 and TRCG2, as well as CD8A, CCL5, and the cytotoxic mediators GZMA and GZMB (Supplementary Fig. 4b). These cells may be γδ T cells or CD8+ αβ T cells expressing TRCG1 and TRCG2 transcripts32. Noteworthy, a few cells in this cluster expressed FOXP3. Because of a lack of specific markers, cluster 5–85 could not be explicitly identified.

We finally re-analyzed the CD4+ T cell cluster pair 2–4, because it contained a small group of CD8A+ cells among a large population of TH17 cells (see Fig. 1c). Reclustering of the 2–4 cluster pair generated four distinct subsets (Fig. 4e). Cluster 2–40 corresponded to activated cytokine-secreting IL23R+ TH17, whereas cluster 2–41 expressed CXCR4, GPR183, and CXCR3, which indicate quiescent TH1733 (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 4c). Cluster 2–42 belonged to the γδ T cell lineage, as indicated by TRCG2 and CD8A expression. These cells expressed RORC, IL17A, and IL26, explaining the initial co-clustering with TH17 cells and suggesting that they may represent a discrete subpopulation of γδ T cells with a type 17 polarization (Fig. 4f). This γδ T cell subset was also marked by NCR3 (Fig. 4f). To validate this γδ T cell subset, we stained IEL with a mAb for TCRVδ2, followed by an antibody that recognizes all γδ TCRs, and a mAb for NKp30 (patient information in Supplementary Data 6). Among Vδ2– γδ+ T cells, about 25–50% of the cells expressed NKp30 in different individuals (n = 9), suggesting that NKp30+ γδ T cells represent approximately half of the TCRVδ2–Vδ1+ γδ T cells (Fig. 4g, h and Supplementary Fig. 4d). All of these cells expressed CD39 (Fig. 4h). In contrast, NKp30 was not expressed by terminal ileum CD8+TCRγδ– T cells (Fig. 4i and Supplementary Fig. 4d), contrary to what shown for colonic CD8+ T cells of UC patients10.

To validate the functional relevance of NKp30 on this unique γδ T cell subset, we sorted all γδ T cells from control patients and tested the expression of RORγt on NKp30+ vs. NKp30– cells. As shown in Fig. 4j, NKp30+ γδ T cells expressed higher level of RORγt than NKp30–. We further expanded NKp30+ γδ T cells in vitro to perform functional assays. Expanded γδ T cells maintained high levels of NKp30 expression (Fig. 4k) and produced IL-26 upon engagement of NKp30 with a cognate antibody (Fig. 4l). Because of the reported antibacterial properties of IL-2634, our results suggest that this discrete γδ T cell subset may have a protective role in intestinal homeostasis.

T cell clusters in LP are differentially activated and represented compared to IEL

We next surveyed the baseline heterogeneity of CD3+ cells in the LP by scRNA-seq of 29,247 cells sorted from the same CD and control samples analyzed for IEL (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c, e; patient information in Supplementary Data 1). Unsupervised clustering of scRNA-seq data from LP T cells by UMAP identified nine clusters (Fig. 5a, b). Three T cell clusters expressed CD8A (1, 2, and 8), six expressed CD4 (0, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7) (Fig. 5c), while one (9) expressed both and was enriched in cell cycle genes, such as MKI67, STMN1, TUBB, and TUBA1B (Fig. 5b, d). Within CD8A+ clusters, cluster 1 showed the hallmarks of effector CD8+ T cells: KLRG1 (Fig. 5d), EOMES, TBX21, CCL4, CCL3, CCL5, IFNG, PRF1, GZMB, GZMA, GZMH, and GZMK (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). This cluster was reminiscent of IEL cluster 6. Cluster 2 and 8 expressed the HVEM receptor CD160 and ITGA1 (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 5c), and the chemokines XCL1 and XCL2 (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Cluster 8 expressed the NK cell receptors KLRC1, KIR2DL4, KLRC2, KLRD1, TRDC, and ENTPD1 (Fig. 5b, d and Supplementary Fig. 5b). Overall, LP clusters 2 and 8 paralleled IEL clusters 0 and 1, respectively.

Fig. 5. scRNA-seq of LP T cells identifies discrete subsets of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

a Unsupervised UMAP analysis of LP T cell clusters. T cells were pooled from two controls and two CD patients (9107 cells control, 20,140 cells CD). b Heat map displaying the top ten differentially expressed genes in each cell cluster. c Identification of CD4 and CD8A expressing cells. d UMAP of representative selected genes associated with the identified clusters.

Among CD4 T cells, cluster 0 corresponded to TH17 based on expression of CCR6, RORA (Fig. 5d), KLRB1, LTB, and CCL20 (Supplementary Fig. 5b, c). Only few cells on the top of the cluster were enriched in genes indicative of effector function, such as IL17A, IL23R, IL26, RORC, CXCR6, GZMB, ENTPD1, and CCL4 (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 5a–c), indicating that LP contains more quiescent than activated TH17 compared to IEL (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Notably, cluster 0 was also enriched in LGALS3 and GPR65 (Supplementary Fig. 5c). LGALS3 encodes galectin 3 that has antibacterial and antifungal immunity35, corroborating antimicrobial properties of TH1736. GPR65 is a proton sensing G-protein-coupled receptor that has been found to be a risk factor for IBD37. Cluster 3 corresponded to naïve T cells expressing CCR7 (Fig. 5d), LEF1, TCF7, SELL, and KLF2 (Supplementary Fig. 5a, c). Cluster 5 and 6 were both TFH based on TOX2 and CXCR5 expression (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 5c); cluster 6 was further distinguishable from cluster 5 based on the selective expression of CXCL13 (Fig. 5d), PDCD1, BTLA, and CD200 (Supplementary Fig. 5c). As opposed to IEL TFH, LP TFH were not readily distinguishable into P2RY8+ and CYSLTR1+ subsets. Cluster 4 corresponded to Treg expressing FOXP3, IL2RA (Fig. 5d), ENTPD1, BATF, IL10, LAIR2, TNFRSF4 (for OX40), and TNFRSF9 (for CD137) (Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). The Treg subset was enriched in GPX1 (Fig. 5d) and GLRX (Supplementary Fig. 5b), which are induced by FOXP3 and encode molecules protecting from oxidative stress38,39. Cluster 5, 6, and 4 shared expression of CTLA4, TIGIT, ICOS (Supplementary Fig. 5c) and the transcription factors TOX, TOX2, and MAF (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 5a), corroborating that TFH and Treg lineages are closely related31. Finally, cluster 7 identified a unique cluster of CD4+ T cells exhibiting a heat-shock stress-activated pathway, as indicated by expression of HSP family members (HSPA1A, HSPA1B, and DNAJB1), JUN, TNF, and IL2 (Fig. 5b, d and Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). The activation of this pathway was also evident at the bottom of the CD8A+ cluster 2 (Fig. 5c, d). Altogether, our data indicated that IEL and LP harbor overlapping T cell subsets, although TH17 in LP are more quiescent than those in the IEL compartment (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Furthermore, LP contained a unique subset of T cells that express heat-shock stress-pathway genes and secreted cytokines such as TNF and IL2.

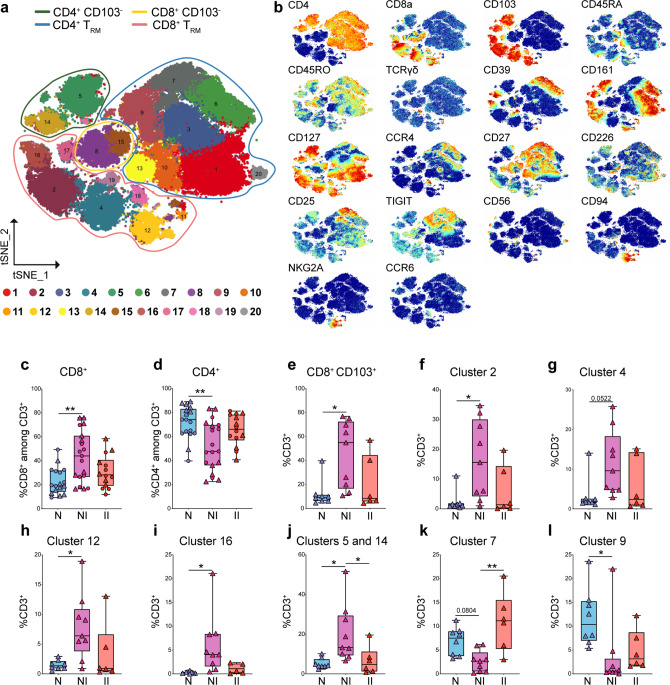

Severe CD modifies the T cell landscape in the LP

To validate scRNA-seq analysis of LP and quantify differences related to disease status, we performed mass cytometry on fresh LP T cells of CD (NI: n = 9; II n = 6) and control patients (n = 8) (patient information: Supplementary Data 7). Dimensionality reduction by viSNE analysis enabled to solve T cell heterogeneity in 20 different clusters. Notably, mass cytometry identified more clusters than scRNA-seq analysis, suggesting that this technique may better distinguish cell subsets that express shared markers at different levels. Eight clusters expressed CD8 (15, 8, 17, 16, 2, 4, 18, and 12), ten clusters expressed CD4 (14, 5, 13, 10, 9, 7, 6, 3, 1, and 20), a small cluster of γδ T cells (19) expressed neither CD4 or CD8, and a tiny cluster (11) remained undefined (Fig. 6a, b). CD103 distinguished tissue-resident CD8+ and CD4+ T cells from circulating cells. CD103– non-resident CD8+ T cells included clusters 15 and 8, which corresponded to naïve CD45RAhi and memory CD45RO+ CD8+ T cells, respectively. CD103+ resident CD8+ T cell clusters 18, 2, 4, and 12 were separated based on expression of CD161 (16 and 2), CD39 (16), CD94 and NKG2A (12), and CCR4 (18) (Fig. 6a, b). Cluster 17, which mapped close to clusters 15 and 8 between circulating and tissue-resident cells, exhibited low/intermediate levels of CD103 (Fig. 6b), suggesting that it may represent recently immigrated CD8+ T cells settling into the tissue.

Fig. 6. Quantification of CD8 and CD4 T cell clusters by CyTOF analysis in LP of control and CD patients.

a Schematic t-SNE of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from LP of all donors concatenated together (n = 18) controls (N), n = 8; CD, non-inflamed site (NI), n = 9; CD, inflamed site (II), n = 6. Total of 23 samples. b t-SNE of the indicated markers in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. c, d Quantification of total CD8+ (c), total CD4+ (d) in LP of controls and CD patients by CyTOF (triangles = fresh samples) and FACS (circles = frozen samples). c, d Control (N), n = 17 (8 fresh, 9 frozen); CD, non-inflamed site (NI) n = 19 (9 fresh, 10 frozen); CD, inflamed site (II), n = 14 (6 fresh, 8 frozen). e–i Quantification of total CD8+ TRM (e) and CD8+ clusters 2 (f), 4 (g), 12 (h), and 16 (i) in LP of controls and CD patients by CyTOF. j–l Quantification of the CD4+ clusters 5 and 14 (j), 7 (k), and 9 (l) in LP of controls and CD patients by CyTOF. e–l Controls (N), n = 8; CD, non-inflamed site (NI), n = 9; CD, inflamed site (II), n = 6. Circles and triangles on the boxplots show data collected for each individual donor. Data were median and interquartile range. Significance was calculated using an ordinary, one-way ANOVA, multiple comparisons test with Prism v8 software. c **P = 0.0014; d **P = 0.028; e *P = 0.0139; f *P = 0.0178; h *P = 0.0178; i *P = 0.0219; j N vs. NI *P = 0.0156, NI vs. II *P = 0.0465; k **P = 0.0014; l **P = 0.0283. TRM tissue-resident memory T cell. Source data are provided as a Source Data file (Source Data 2).

Within CD4+ T cells, CD103– clusters 1, 3, 6, and 20, corresponded to circulating memory TH17 cells expressing CD161, CD45RO, and CD127 (Fig. 6a, b). The four clusters were distinguished based on the expression of CD39, CCR4 (6), CD27 (6 and 3), and CD226 (1 and 20) (Fig. 6a, b). The expression of CD226 may be suggestive of pathogenicity, as CD226 has been implicated in autoimmunity40. Clusters 5 and 14 represented tissue-resident memory TH17 because of the expression of CD103, CD45RO, and CD161. As in IEL, these cells were split in CD39+ and CD39– subsets. Cluster 7 consisted of Treg as indicated by high CD25 and CD39 expression (Fig. 6b), while cluster 9 included TFH cells based on high TIGIT expression41 (Fig. 6b). Clusters 13 represented naïve CD45RAhi CD45RO– CD4+ T cells, while cluster 10 was marked by expression of CD45RO and loss of CD45RA, indicative of a memory phenotype (Fig. 6a, b). Finally, cluster 20 was distinguished based on CD56 expression (Fig. 6b), which is typical of cytokine-induced killer cells.

Quantification of different LP clusters in CD and control patients revealed an opposite trend than what observed in IEL, with a significant increase in CD8+ T cells paralleled by a decrease in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 6c, d; fresh samples triangles). These data were confirmed by flow cytometry in a different cohort of frozen samples from control (n = 9) and CD (n = 11) patients and combined to the CyTOF data (Fig. 6c, d; frozen samples circles; patient information: Supplementary Data 7 and Source Data 2). Among CD8+ T cells, CD103+ resident cells were increased in CD compared to controls (Fig. 6e), as evidenced by expansion of clusters 2, 4, 12, and 16 (Fig. 6f–i). Although total CD4+ T cells were reduced in CD, TH17 of clusters 5 and 14 were significantly increased at the non-inflamed site of CD lesions (Fig. 6j). On the contrary, Treg (7) and TFH (9) were decreased (Fig. 6k, l). The increase in TH17 cells (CD4+CCR6+CD161+) and decrease of TFH (TIGIT+) was further confirmed by running CITRUS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 7a–c). Taken together, our data suggested that inflammatory TH17 and CD8+ T cells are increased in the LP of CD, paralleled by an attrition of CD4+ T cells with regulatory properties, consistent with deepened gut wall inflammation.

Discussion

Through a high-resolution analysis of human intestinal IEL T cells in controls and severe adult CD, our study defined a vast heterogeneity of T cell lineages in the IEL compartment, including various subsets of CD8+, γδ+, and CD4+ T cells. Compared to controls, CD was associated with major abnormalities in the composition of IEL T cells, which included: (a) an increase in inflammatory CD39+ TH17; (b) a decrease in Treg, which might exacerbate inflammation; (c) a decrease in TFH, which may explain the impaired mucosal IgA production previously reported in CD42; and (d) a global reduction of CD8+ T cells and γδ T cells. These changes in the IEL compartment were coupled with increased CD8+ T cells and TH17, as well as reduced TFH and Treg in the LP, likely reflecting the deepening of inflammation and overt transmural damage1,2. Overall, despite some limitations of our study due to cohort heterogeneity of CD patients, our results offer insight into T cell correlates of transmural inflammation and relapsing/recurrent disease.

The remarkable heterogeneity of human T cells identified in the IEL compartment reflected the presence of different T cell lineages, as well as various stages of differentiation, activation, and tissue residency within each lineage. TH17 cells included quiescent cells and cells capable of immediate effector functions, which were readily distinguished based on the mutually exclusive expression of CXCR4 and CD39, among other distinctive markers. IEL CD39+ TH17 may be a two-edged sword. On one hand, they exhibit pathogenic features, such as expression of GZMB and CCL4, suggesting that they may be cytotoxic against epithelial cells and recruit inflammatory cell types that promote tissue destruction. On the other hand, production of IL-17 and IL-26 may enhance barrier function, providing protection. Given that CD39 has been shown to sustain TFH survival by degrading proapoptotic ATP released in the intestinal environment43, CD39 may sustain survival of the TH17 cells. Further increasing diversity, TH17 expressed different levels of CD103, indicating the presence of TH17 at different stages of migration ranging from circulating to tissue-resident.

TFH also included two major subsets: one subset expressed P2RY8, a G-protein-coupled receptor that inhibits cell migration upon binding S-geranylgeranyl-l-glutathione, which is present in bile salts29; another subset expressed CYSLTR1, which binds to another glutathione-conjugated lipid mediator, LTC429. TFH expressing high levels of CYSLTR1 were not previously identified in lymph nodes and may be specific to IEL30. These TFH subsets showed other distinctive markers: P2RY8+ TFH expressed CXCR5 and TNFSF8 (for CD30L); CysLTR1+ TFH expressed BTLA and CD200. P2RY8 mediates the retention of TFH and B cells in the germinal center, while BTLA restrain TFH germinal center responses29. TNFSF8 gene polymorphisms have been associated with risk of CD44. Although IEL TFH did not show mRNA for the B cell stimulatory cytokine IL-21, P2RY8+, and CysLTR1+ TFH subsets may control mucosal B cell responses through other mechanisms, such as BTLA–HVEM and TNFSF8–TNFRSF8 interactions.

IEL CD8+ T cells were also quite heterogeneous, including canonical CD103–KLRG1+ cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and multiple subsets of tissue-resident CD8+ T cells, which shared the expression of CD103 and CD160 that may secure retention of T cells through binding to E-cadherin and HVEM on epithelial cells, respectively. Moreover, CD160 may shape the function of CD8+ T cells by inducing IFN-γ45. Tissue-resident CD8+ T cells included a subset of IL-7R+TCF7+ cells producing the DC chemoattractants XCL1 and XCL226, which may recruit DCs from the LP. Other resident CD8+ T cells subsets were prone to effector functions: one subset expressed IFN-γ and the NK receptor KLRC1 specific for HLA-E; another expressed cytotoxicity mediators, lacked NK receptors but expressed the membrane protein EMP3, which has yet unknown function in immune responses. Finally, a group of resident CD8+ T cells expressed EIF5A, MDM4, and SET, which control p53 activity28, suggesting evasion from apoptosis and senescence. Many tissue-resident CD8+ T cells expressed S100A family members, which may contribute to antimicrobial functions.

One remarkable result of this study is the identification of at least two subsets of γδ T cells within the IEL. One subset expressed TH17 markers, such as RORC, IL-23R, IL-22, and IL-26. RORγt+ γδ T cells have been extensively described in mouse47,48 but not in human. Distinctive features of these γδ T cells included the expression of TCRVδ1, CD39, and NKp30, an activating cell surface receptor specific for B7H649. Importantly, NKp30+ γδ T cells expressed higher levels of RORγt ex vivo as compared to NKp30– γδ T cells and engagement of NKp30 resulted in IL-26 production, suggesting that these cells may have a protective function during homeostasis. Some traits of these γδ T cells, such as NKp30 expression and IL-26 production, were recently reported in a subset of CD8 T cells expanded in colon of UC patients10. Whether these colonic cells are bona fide CD8 T cells or γδ T cells expressing CD8, as we find in the small intestine, remains to be established. Another γδ T cell subset expressed the canonical γδ T cell transcription factor ID332; this subset expressed NK cell receptors and produced CSF1 and PDGFD, pointing to a potential crosstalk with macrophages and epithelial cells. While subsets of human γδ secreting CSF1 have been reported46, PDGFD secretion by γδ T cells has not been described before. In addition, a rare cell subset expressing γ-constant region of γδTCR and CD8A expressed FOXP3. Future studies will be required to precisely identify these cells and to test their regulatory function.

Notably, our cohort of severe adult CD showed a reduction of IEL CD8+ T cells and γδ T cells. Consistently, a population of CD39+ CD8+ T cells and γδ T cells has been recently reported to decrease in colonic mucosa biopsies of pediatric CD patients9. This population overlaps with the γδ and CD8+ T cell subsets expressing NK cell receptors and CD39 reported here. While we observed a global reduction rather than a selective loss of specific subsets of CD8 and γδ T cells, this discrepancy may depend on differences in patient ages (children vs. adults), sampling location (colon vs. ileum), type of specimen (biopsies vs. surgical resections) or degree of disease.

Finally, analysis of LP T cell transcriptomes identified unique functional features not immediately related to the classical T cell functional modules. A subset of LP CD4+ T cells expressed heat-shock induced stress-pathway genes and cytokines, such as TNF and IL-2. A T cell subset expressing heat-shock proteins was also among five IEL populations recently reported in CD50. Intriguingly, a recent study showed that febrile temperature in mice induces TH17 differentiation and augments pathogenicity through heat-shock response genes51. Together, these observations highlight the involvement of heat-shock response in the differentiation of T cells in the intestine. Expression of GPX1 in Tregs of the LP revealed the activation of anti-oxidative pathways in intestinal T cells, which may be particularly relevant to CD, as GPX1 gene polymorphisms have been associated with risk of CD52,53. These results will prompt future studies to determine the impact of these unique functions in CD pathogenesis.

Methods

Preparation of single-cell suspension from intestinal samples

Single-cell suspension was prepared as previously described54. Briefly, mucosal tissue from terminal ileum was separated from the muscular layer and serosa and cut into small pieces. Intraepithelial lymphocyte cells were extracted by rotating the tissue at room temperature for 40 min in Hank’s balanced salt solution, 10% FCS, and 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Cells were filtered through 100-μm cell strainers and dithiothreitol (DTT) was added at a final concentration of 5 mM. After intraepithelial lymphocyte removal, LP cells were extracted by digesting tissue in complete RPMI medium containing 1 mg ml–1 Collagenase IV (Sigma, C-5138) at 37 °C for 1 h under agitation. Cells were filtered and subjected to density gradient centrifugation using 40 and 70% Percoll solutions. Cells were collected, sorted, and processed for scRNA-seq or collected and stained for CyTOF. From a set of patients cells were processed and frozen for later CyTOF or flow cytometry analysis. Control patients for the present study were patients undergoing abdominal surgery for colon cancer or polyposis, which had non-involved terminal ileum removed, as part of the surgical procedure.

All human studies were conducted under the approval of the Institutional Review Boards of Washington University. All ileum samples were provided as surgical waste with no identifiers attached on written informed consent to the Digestive Disease Research Cores Center at Washington University. The demographic data provided in this study will not allow patient identification.

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks used for this study were retrieved from the tissue bank of the Department of Pathology (ASST, Spedali Civili di Brescia, Brescia, Italy). Four-micron thick tissue sections were used for immunohistochemical staining. Sections were incubated with anti-human CD4 (clone 4B12 1:50 Thermo Scientific) and antihuman CD8 antibody (clone C8-144B Agilent 1:50) and the reaction was revealed using Novolink Polymer (Leica Microsistem). For double staining, after completing the first immune reaction, the second was visualized using Mach 4 MR-AP (Biocare Medical), followed by Ferangi Blue. Finally, the slides were counterstained with Meyer’s Haematoxylin.

Antibodies

Information on the antibodies used for flow cytometry and sorting is available in Supplementary Data 8.

Flow cytometry and sorting

Cells were sorted on BD FACS Aria II and flow cytometry analyses were performed on BD Symphony A3 instrument. Data were analyzed by FlowJo software v10.7.1 (TreeStar).

scRNA-seq and data analysis

T cells were sorted from processed IEL and LP as CD45+, lymphocyte gate, singlets, and alive CD3+ CD19– expression. Sorted cells were sequenced using 10X Genomics platform with chemistry version 2. Cell Ranger pipeline (https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-gene-expression/software/over-view/welcome) was used to process Chromium single-cell RNA-seq output to align reads and generate gene-cell expression matrices. Briefly, short sequencing reads were aligned to the GRCh38 reference genome and Ensembl55 transcriptome by STAR56. The uniquely aligned reads were used to quantify gene expression levels for all Ensembl genes. We filtered out low-quality cells from the dataset if the number of genes detected was <500 or >3000, or the percentage of mitochondrion reads was >15%. Mitochondrion and ribosomal genes usually consumed a large fraction of reads in our dataset, and their relative abundance varied significantly from sample to sample. Such genes were not interesting in our research, and thus were excluded for downstream data analysis. Additionally, all genes that were not detected in at least 1% of all our single cells were discarded. Average UMI were 2960 and 3020 for IEL and LP T cells, respectively.

scRNA-seq downstream analysis

Downstream analyses were performed using Seurat R software package version 3.0 (http://satijalab.org/seurat/). After removing unwanted cells and genes from the dataset, raw UMIs in each cell were first scaled by library size and then log-transformed. To improve downstream dimensionality reduction and clustering, we first regressed out unwanted source of variation arising from the number of detected molecules. Then highly variable genes were identified and selected for PCA reduction of high-dimensional data. Cells in this reduced spaced were harmonized to adjust for batch effects coming from multiple donors including both normal and CD using the Harmony tool implemented in Seurat v357. These low dimensional corrected Harmony embeddings were used for downstream analyses. Graph-based clustering was performed on the reduced data for clustering analysis with Seurat v3. The resolution in the FindClusters function in Seurat was set to 0.6 and the clustering results were shown in a UMAP plot. For different cell types, cells were grouped based on top markers. MAST in Seurat v3 was used to perform differential analysis58. For each cluster, DEGs were generated relative to all of the other cells.

CyTOF acquisition and analysis

All antibodies information is available in Supplementary Data 9. Cells were washed with Cy-FACS buffer (CyPBS, Rockland, MB-008; 0.1% BSA, Sigma, A3059; 0.02% Sodium Azide, Sigma, 71289, 2 mM EDTA, Hoefer, GR123-100) stained on ice for an hour. After two washes cells were stained with cisplatin (Enzo Life Sciences, NC0503617) for 1 min, washed again twice, fixed in 4% PFA (Electron Microscopy Sciences, 15710) for 15 min, spun down and re-suspended in Intercalator-Ir125 (Fluidigm, 201192 A) overnight. Cells were washed and counted and analyzed on a CyTOF 2 mass cytometer (Fluidigm). Samples were manually gated using Cytobank. Background, dead cells (Cisplatin+), doublets (DNA1/2 stain), and normalization beads were excluded. Dimensionality reduction analysis was performed by equally sampling CD45+ CD3+ CD19− cells per donor based on 20 different markers (CD4, CD8a, NKp44, CD127, CD45RA, CD103, TIGIT, CCR4, CD39, CD45RO, CCR6, CD25, TCRγδ, CD161, NKG2A, CD226, CD94, CD56, CD27, and CD294) using the viSNE tool59 in Cytobank to apply the Barnes–Hut implementation of the t-SNE algorithm. viSNE data were exported from Cytobank and uploaded into MATLAB implementation of Phenograph60 and transformed using a cofactor of five for subsequent clustering analysis. Visualization of clusters identified by Phenograph was done using the R package ggplot2. CITRUS analysis was performed by equally sampling CD45+ CD3+ CD19− CD4+ (1807) cells per sample based on the expression of 14 markers (CD45RO, CD45RA, CCR6, CCR4, CD161, CD127, CD25, CD39, TIGIT, CD117, CD103, CD27, NKp44, and CD226) using the CITRUS tool in Cytobank. Significant changes in cell frequency were inferred with SAM (a nonparametric correlative method) for an FDR <1%. Every cluster displayed contains at least 3% of all clustered cells and are scaled on the basis of frequency of cells in each cluster.

Ex vivo intracellular staining of γδ T cells for RORγt

Total γδ T cells were sorted from IEL of control patients and cell surface stained for NKp30, CD39, fixed and permeabilized and stained intracellularly for RORγt with eBioscience FoxP3 staining kit.

In vitro T cell culture and NKp30 crosslinking

NKp30+ γδ T cells were sorted from IEL of control patients and expanded in vitro with PHA (HA16, Remel), irradiated feeder and IL-2. Expanded cells were stimulated with plate bound anti-NKp30 (clone 30.95.1) or isotype control (CRL-1729, ATCC). IL-26 was measured in supernatants 72 h later by ELISA (CUSABIO).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism 8.4.3 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) or R version 3.6.2 (2019), as indicated in the figure legends. Data were presented as median and interquartile range. Unless otherwise noted, statistically significant differences between groups were determined by ordinary one-way ANOVA. In all figures, the following symbols were used to designate significance: *P ≦ 0.05, **P ≦ 0.01, ***P ≦ 0.001.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank the Genome Technology Access Center at the McDonnel Genome Institute at Washington University for scRNA-seq on the 10X platform. The center is supported by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR002345 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). We thank E. Lantelme and D. Brinja and the Pathology and Immunology Flow Cytometry Core for cell sorting. We thank D. Bender, R. Lin, and S. Oh and the Center for Human Immunology at Washington University for help in processing the samples for mass cytometry and for advice on analysis. We thank the Washington University Digestive Disease Research Core (NIDDK P30 DK052574) for support. Author R.G. thanks Eric Fauman for supporting the completion of this work. N.J. was partly supported by the Lucille P. Markey Special Emphasis Pathway in Human Pathobiology. This work was in part supported by grants UO1 AI095542, RO1 DE025884, RO1 AI134035, RO1 DK124699, and U19 AI142733 (to MCo).

Source data

Author contributions

N.J., R.G., and M.Ce. designed, performed, analyzed, and interpreted experiments. J.L.S. helped with CyTOF and Citrus analysis. S.Z. designed the pipeline for scRNA-seq data analysis. BK collected patients’ data. B.D.L. helped in processing tissue. E.E. and M.N.A. helped with scRNA-seq analysis. W.V. and M.B. performed immunohistochemistry. C.V.R., T.A.W., and R.J.X. provided critical insights to the study. S.A.J. and M.Co. supervised the study. N.J., M.Ce., S.A.J., and M.Co. wrote the manuscript and all the authors contributed editing and suggestions.

Data availability

The scRNA-seq have been deposited in GEO under the GSE157477. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

R.G., S.Z., J.S., C.V.R., T.A.W., and S.A.J. are Pfizer employees. M.Co. received funding from Pfizer to study ILC biology in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Natalia Jaeger, Ramya Gamini, Marina Cella.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-22164-6.

References

- 1.Blumberg R, Powrie F. Microbiota, disease, and back to health: a metastable journey. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4:137rv137. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown EM, Kenny DJ, Xavier RJ. Gut microbiota regulation of T cells during inflammation and autoimmunity. Annu Rev. Immunol. 2019;37:599–624. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042718-041841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirten RP, Iacucci M, Shah S, Ghosh S, Colombel JF. Combining biologics in inflammatory bowel disease and other immune mediated inflammatory disorders. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;16:1374–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smillie CS, et al. Intra- and inter-cellular rewiring of the human colon during ulcerative colitis. Cell. 2019;178:714–730 e722. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parikh K, et al. Colonic epithelial cell diversity in health and inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2019;567:49–55. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0992-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinchen J, et al. Structural remodeling of the human colonic mesenchyme in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2018;175:372–386 e317. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin JC, et al. Single-cell analysis of Crohn’s disease lesions identifies a pathogenic cellular module associated with resistance to anti-TNF tTherapy. Cell. 2019;178:1493–1508 e1420. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.West NR, et al. Oncostatin M drives intestinal inflammation and predicts response to tumor necrosis factor-neutralizing therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Med. 2017;23:579–589. doi: 10.1038/nm.4307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang B, et al. Mucosal profiling of pediatric-onset colitis and IBD reveals common pathogenics and therapeutic pathways. Cell. 2019;179:1160–1176 e1124. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corridoni, D. et al. Single-cell atlas of colonic CD8(+) T cells in ulcerative colitis. Nat. Med.26, 1480–1490 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Cheroutre H, Lambolez F, Mucida D. The light and dark sides of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:445–456. doi: 10.1038/nri3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jandke A, et al. Butyrophilin-like proteins display combinatorial diversity in selecting and maintaining signature intraepithelial gammadelta T cell compartments. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3769. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17557-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olivares-Villagomez D, Van Kaer L. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes: sentinels of the mucosal barrier. Trends Immunol. 2018;39:264–275. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayassi T, Jabri B. Human intraepithelial lymphocytes. Mucosal Immunol. 2018;11:1281–1289. doi: 10.1038/s41385-018-0016-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skon CN, et al. Transcriptional downregulation of S1pr1 is required for the establishment of resident memory CD8+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:1285–1293. doi: 10.1038/ni.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Asady R, et al. TGF-{beta}-dependent CD103 expression by CD8(+) T cells promotes selective destruction of the host intestinal epithelium during graft-versus-host disease. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:1647–1657. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shui JW, Kronenberg M. HVEM is a TNF receptor with multiple regulatory roles in the mucosal immune system. Immune Netw. 2014;14:67–72. doi: 10.4110/in.2014.14.2.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iezzi G, et al. CD40-CD40L cross-talk integrates strong antigenic signals and microbial stimuli to induce development of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:876–881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810769106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hase K, et al. The membrane-bound chemokine CXCL16 expressed on follicle-associated epithelium and M cells mediates lympho-epithelial interaction in GALT. J. Immunol. 2006;176:43–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee Y, et al. Induction and molecular signature of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:991–999. doi: 10.1038/ni.2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garg G, et al. Blimp1 prevents methylation of Foxp3 and loss of regulatory T cell identity at sites of inflammation. Cell Rep. 2019;26:1854–1868 e1855. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crotty S. T follicular helper cell differentiation, function, and roles in disease. Immunity. 2014;41:529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lauritsen JP, et al. Marked induction of the helix-loop-helix protein Id3 promotes the gammadelta T cell fate and renders their functional maturation Notch independent. Immunity. 2009;31:565–575. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jadhav RR, et al. Epigenetic signature of PD-1+ TCF1+ CD8 T cells that act as resource cells during chronic viral infection and respond to PD-1 blockade. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:14113–14118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1903520116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siddiqui I, et al. Intratumoral Tcf1(+)PD-1(+)CD8(+) T cells with stem-like properties promote tumor control in response to vaccination and checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Immunity. 2019;50:195–211 e110. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bottcher JP, et al. NK cells stimulate recruitment of cDC1 into the tumor microenvironment promoting cancer immune control. Cell. 2018;172:1022–1037 e1014. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackay LK, et al. Hobit and Blimp1 instruct a universal transcriptional program of tissue residency in lymphocytes. Science. 2016;352:459–463. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toledo F, Wahl GM. Regulating the p53 pathway: in vitro hypotheses, in vivo veritas. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:909–923. doi: 10.1038/nrc2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mintz MA, Cyster JG. T follicular helper cells in germinal center B cell selection and lymphomagenesis. Immunol. Rev. 2020;296:48–61. doi: 10.1111/imr.12860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gagliani N, et al. Coexpression of CD49b and LAG-3 identifies human and mouse T regulatory type 1 cells. Nat. Med. 2013;19:739–746. doi: 10.1038/nm.3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cannons JL, Lu KT, Schwartzberg PL. T follicular helper cell diversity and plasticity. Trends Immunol. 2013;34:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pizzolato G, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing unveils the shared and the distinct cytotoxic hallmarks of human TCRVdelta1 and TCRVdelta2 gammadelta T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:11906–11915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1818488116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tischner, D. et al. Single-cell profiling reveals GPCR heterogeneity and functional patterning during neuroinflammation. JCI Insight2, e95063 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Weiss DI, et al. IL-1beta induces the rapid secretion of the antimicrobial protein IL-26 from Th17 cells. J. Immunol. 2019;203:911–921. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1900318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henderson NC, Sethi T. The regulation of inflammation by galectin-3. Immunol. Rev. 2009;230:160–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaffen SL, Jain R, Garg AV, Cua DJ. The IL-23-IL-17 immune axis: from mechanisms to therapeutic testing. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:585–600. doi: 10.1038/nri3707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lassen KG, et al. Genetic coding variant in GPR65 alters lysosomal pH and links lysosomal dysfunction with colitis risk. Immunity. 2016;44:1392–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugimoto N, et al. Foxp3-dependent and -independent molecules specific for CD25+CD4+ natural regulatory T cells revealed by DNA microarray analysis. Int. Immunol. 2006;18:1197–1209. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kryukov GV, et al. Characterization of mammalian selenoproteomes. Science. 2003;300:1439–1443. doi: 10.1126/science.1083516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hafler JP, et al. CD226 Gly307Ser association with multiple autoimmune diseases. Genes Immun. 2009;10:5–10. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boles KS, et al. A novel molecular interaction for the adhesion of follicular CD4 T cells to follicular DC. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009;39:695–703. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MacDermott RP, et al. Altered patterns of secretion of monomeric IgA and IgA subclass 1 by intestinal mononuclear cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:379–385. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90572-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Proietti M, et al. ATP-gated ionotropic P2X7 receptor controls follicular T helper cell numbers in Peyer’s patches to promote host-microbiota mutualism. Immunity. 2014;41:789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hong SN, et al. Deep resequencing of 131 Crohn’s disease associated genes in pooled DNA confirmed three reported variants and identified eight novel variants. Gut. 2016;65:788–796. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tu TC, et al. CD160 is essential for NK-mediated IFN-gamma production. J. Exp. Med. 2015;212:415–429. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mamedov MR, et al. A macrophage colony-stimulating-factor-producing gammadelta T cell subset prevents malarial parasitemic recurrence. Immunity. 2018;48:350–363 e357. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barros-Martins J, et al. Effector gammadelta T cell differentiation relies on master but not auxiliary Th cell transcription factors. J. Immunol. 2016;196:3642–3652. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khairallah C, Chu TH, Sheridan BS. Tissue adaptations of memory and tissue-resident gamma delta T cells. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2636. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brandt CS, et al. The B7 family member B7-H6 is a tumor cell ligand for the activating natural killer cell receptor NKp30 in humans. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:1495–1503. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uniken Venema WT, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing of blood and ileal T cells from patients with Crohn’s disease reveals tissue-specific characteristics and drug targets. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:812–815 e822. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang X, et al. Febrile temperature critically controls the differentiation and pathogenicity of T helper 17 cells. Immunity. 2020;52:328–341 e325. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Costa Pereira C, et al. Association between polymorphisms in antioxidant genes and inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0169102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Esworthy RS, et al. Colitis locus on chromosome 2 impacting the severity of early-onset disease in mice deficient in GPX1 and GPX2. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1373–1386. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cella M, et al. Subsets of ILC3-ILC1-like cells generate a diversity spectrum of innate lymphoid cells in human mucosal tissues. Nat. Immunol. 2019;20:980–991. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0425-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zerbino, D. R. et al. Ensembl 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D754–D761 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Stuart, T. et al. Comprehensive Integration of Single-Cell Data. Cell177, 1888–1902.e21 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Finak, G. et al. MAST: a flexible statistical framework for assessing transcriptional changes and characterizing heterogeneity in single-cell RNA sequencing data. Genome Biol. 16, 278 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Amir el, A. D. et al. viSNE enables visualization of high dimensional single-cell data and reveals phenotypic heterogeneity of leukemia. Nat. Biotechnol.31, 545–552 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Levine, J. H. et al. Data-Driven Phenotypic Dissection of AML Reveals Progenitor-like Cells that Correlate with Prognosis. Cell162, 184–197 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The scRNA-seq have been deposited in GEO under the GSE157477. Source data are provided with this paper.