Abstract

Older adults often lose their ability to independently ambulate during a hospital stay. Few studies have investigated older adults’ experiences with ambulation during hospitalization.

The purpose of this study was to understand older adults’ perceptions of and experiences with ambulation during a hospital admission.

A qualitative study using Inductive Content Analysis was conducted. Community-dwelling older adults (N = 11) were recruited to participant in five focus group meetings each lasting 90 min. All individuals participated in each focus group.

Participants described high complexity in deciding whether or not they could ambulate. Six categories were identified: Uncertainty, Restriction Messaging, Non-Welcoming Space, Caring for Nurse and Self, Feeling Isolated, and Presenting Self.

This study provides a detailed understanding of older adults’ experiences and perceptions of a hospital stay. Findings from this study can serve as a foundation for future interventions to improve older adult patient ambulation during hospitalization.

Background

For many older adults a hospital stay can result in catastrophic events, such as, loss of functional independence, delirium, malnutrition and the need for new nursing home placement.1–3 Of these negative consequences, loss of functional ability, including ambulation and performing activities of daily living (ADLs), place the greatest threat to independent living post discharge, as well as impacting quality of life for older adults.4,5 Loss of functional ability during a hospital stay has been identified as a hospital associated disability6 and occurs globally.1,7 Multiple causes for loss of functional ability during hospitalization have been identified, including: the health issue requiring admission, medical procedures, polypharmacy, insufficient sleep, and imposed bed rest or limited mobility.8,9 In particular, lack of walking during a hospital stay has been identified as the most predictable and preventable cause of loss of independent ambulation in older adults.10 Limited patient ambulation is common in hospital settings. Hospitalized older adults spend up to 88% of their time in bed1,11 and engage in less than 4 h of ambulation during their hospital stay.12,13 Deconditioning effects of limited ambulation often produces a decrease in lower extremity muscle strength, contributing to functional decline after discharge.1,14

Further, older adult patients state that the hospital environment is not conducive for promoting ambulation. Being tethered to medical equipment such as intravenous lines, wearing embarrassing gowns,15,16 and receiving messages from nursing staff that independent ambulation is not permitted in order to prevent falls,17 all serve as barriers to patient-initiated ambulation. Additionally older adults often interpret staff rushing in and out of rooms or lack of interest in getting them up to walk as indicators that walking during a hospital stay is not important.15 Older adult patients also identified that their autonomy is restricted for decisions about getting out of bed, walking outside of their room, choosing clothes, and setting times for meals or bathing.18 Older adults identified that ambulation was critical for their sense of well-being and pivotal for overall quality of life post discharge.23,24 Thus, there is increased concern that hospital environments may be toxic and hostile to older adults producing heightened stress and impacting their recovery post discharge.18

Studies have identified that how older adults experience hospitalization impacts post-hospital outcomes.19,20 Two recently described phenomena, Post Hospital Syndrome21 and Trauma of Hospitalization,22 link lack of ambulation during the hospital stay with a transient period of vulnerability or risk for new or recurrent illness post discharge and 30-day readmission rates for older persons. For many older adults, the harmful effects of hospitalization come as a surprise. Boltz, Capezuti, Shabbat, and Hall (2010) found that older adults expect to be “discharged better not worse” after a hospital stay.23 Being worse off was attributed to deconditioning and loss of physical function. Other studies found that older adults’ experience both physical and psychological consequences following discharge.25–27 The loss of functional independence forces older adults to rely on family and friends to accomplish daily tasks such as bathing, dressing, transportation and meal preparation.26 Needing support results in older persons feeling burdensome to loved ones and a sense of apathy that impacts their motivation for recovery post discharge.27

In order to combat loss of functional ability during a hospital stay, it is imperative that older adults get up to walk. One study focused on how to modify the healthcare system to improve older adult patient ambulation but only addressed barriers that nursing staff experience.28 Few studies have investigated how older adults perceive the hospital environment related to ambulation. The purpose of this qualitative study was to understand older adults’ perceptions of and experiences with ambulation during a hospital admission

Methods

Before initiating this study, Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Wisconsin- Madison was obtained. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to beginning data collection. The study was conducted between August 2017 and November 2018. Inductive content analysis using Preparation, Organizing and Abstraction phases, as outlined by Elo and Kyngas (2008), was used to guide data collection and analysis.29 Table 1.0 outlines key features of each phase of the inductive content analysis29 along with examples of how each feature was used in conducting this study.

Table 1.0.

| Phase | Key Feature | Example |

|---|---|---|

| preparation (pre-data collection) | • select the unit of analysis • decide on sampling plan • decide on type of data to include • decide on format for collecting data |

• the research team decided the unit of analysis would be a theme • purposive sampling plan selected • included manifest and latent data • selected focus group format to collect interview and observation data • selected number of focus group meetings • decided on number of participants/focus group meeting |

| organizing (data collection and analysis) | • gather data (conduct interviews, review literature, collect observations) • engage in open coding • develop preliminary subcategories |

• conducted focus group interviews with 11 participant members who attended each focus group • observations of non-verbal behavior were made during each focus group • debriefed after each focus group to discuss observations and decide on action plan if needed to improve data collection • textual data transcribed verbatim • memos related to observations completed • data analysis occurred immediately after each focus group meeting • conducted line-by-line analysis assigning labels to data • labels conceptually similar were grouped into subcategories • started developing preliminary categories and linked subcategories to categories |

| Abstraction (Analysis) | Finalize identification of categories Identify main category | • Continued data reduction to identify categories and fill in subcategories • Used constant comparative analysis to determine accuracy of data classification in each category • Formulated a description of the phenomena linking categories to the main category |

Sample and setting

The study was conducted in a community setting in an urban city in Wisconsin, United States. Purposive sampling was used to select participants who would have knowledge and experiences relevant to the research subject.29 Inclusion criteria consisted of: community-dwelling older adult aged 65 years or older, with a hospital admission in the past year, and able to understand and speak English. Recruitment flyers to participate in focus groups were posted over a four-week period in two outpatient geriatric clinics and in two community centers that serve a diverse population. Contact information for the principle investigator (PI) (BK) was included on the flyer. Those interested in hearing more about the study were instructed to either email or call the PI. Twelve individuals contacted the PI via phone. During the conversation the PI screened for eligibility, discussed the study in greater detail, and answered all questions. At the end of the conversation the PI asked individuals if they were interested in participating. All 12 indicated they were. An information handout that contained all content discussed over the phone was then mailed to each person. Another member of the research team (JB) followed up with a phone call to all 12 individuals one week after mailing the information handout. During this call any additional questions were answered and verbal consent to participate in the study was obtained.

In order to promote rich discussions, a sample of 12 older adults (maximum recommendation) was selected for focus group meetings.30–32 We successfully recruited 12 individuals; however, one dropped out due to limited availability to attend meetings, leaving a final sample of 11. One participant was recruited from an outpatient geriatric clinic and 10 from two community centers. The sample consisted of six males and five females, one African American and 10 white or Caucasian, with ages ranging from 68 to 85 years. The research team had no prior relationship with the community settings where participants were recruited.

Procedure for focus group meetings

Two team members (BK, JB) conducted all focus groups. One researcher (BK) conducted all interviews, while the other researcher (JB) recorded observations and managed meeting logistics, such as setting up the room, audio recording the session, and providing incentives after data collection. Focus group meetings occurred in a private room at a local community center. Five separate focus group meetings, each lasting 90 min were held. All 11 participants attended each focus group meeting.

Procedure for data collection and analysis

Preparation phase.

Prior to conducting data collection the research team selected the unit of analysis, which can be a word, sentence, or a theme that represents the phenomena of interest.29 For this study, the unit of analysis was: older adult patient experiences with walking during a hospital stay. Choosing a theme as the unit of analysis allowed the research team to think more comprehensively about how, when, and where patients engage in walking, and the impact of the hospital context on patient-initiated ambulation. The research team also selected the type of data, manifest (transcribed text from interviews) or latent (observations noted during focus groups), to include in the analysis and the format for collecting data.29 For this study, the use of both manifest and latent data, and focus groups were selected.

Organizing and Abstraction phase.

The Organizing and Abstraction Phase, primarily consists of data collection and analysis. Interview questions about participants’ experiences with ambulating during a hospital stay were asked during focus group meetings. Questions were initially open-ended to allow each participant an opportunity to describe their varied experiences with walking. An example of an open question used was: “Describe for us what it was like for you to get up to walk during your hospital stay”. Later interview questions were more focused to densify the initial findings and fill in gaps in the analysis.34 An example of a focused question was: “The last time we met, members talked about not wanting to go out in the hallway because of how they looked. Can you describe more about how appearance impacted your decision about walking outside of your patient room?”. Consistent with an inductive content analysis approach, data analysis immediately followed data collection. Based on findings that emerged from the data, new questions that would help identify and fill in categories and subcategories were developed and posed to participants at the next focus group meeting. Building off of findings from prior focus groups assisted the researchers in identifying when saturation, the point when no new findings or information emerges, of a category or subcategory occurred.56

All participants were engaged and contributed during meeting sessions. Focus group meetings were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Observations of group interactions, pauses in the conversation, and non-verbal communications were recorded during each meeting to help the research team understand if words were confusing or if questions needed clarification. For example, during the first focus group session, the team noted that one participant was quieter than others and leaned in during the conversation. The team discussed during the post-interview debriefing that the member might have trouble hearing. A team member (JB) contacted the participant later to verify if hearing was challenging during the group discussion and offered the use of one of our portable hearing aid devices. The participant stated he was struggling with hearing and would welcome using the aid. With use of the portable hearing aid, the participant became more engaged in the remaining focus group meetings.

Data analysis consisted of inductively coding the data using open coding, creating subcategories and categories, and abstraction to identify the main category.29 Open coding was done by deconstructing the text using a line-by-line method and assigning labels. Subcategories were created by grouping labels that were conceptually similar.29 Finally subcategories were grouped into categories, which were linked to the main category. Two research team members (BK, JB) with expertise in qualitative methodology independently coded transcripts. During weekly analysis meetings codes identified by each member were compared and discussed for consistency. If disagreement in codes occurred, team members reanalyzed the text together to come to consensus on what the code should be. Creating categories and subcategories from the open codes also occurred in the weekly analysis sessions.

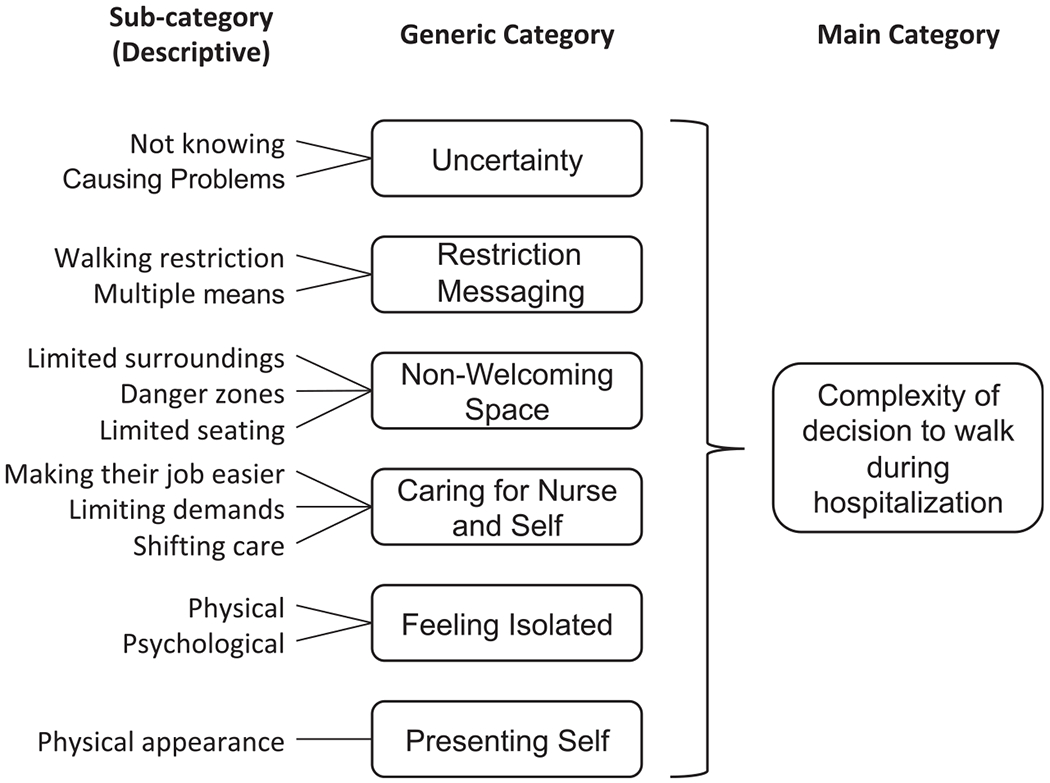

During Abstraction the researchers identified the main category, which is the reoccurring thread of underlying meaning that runs through all categories.38 The researchers also engaged in constant comparative analysis, by comparing data obtained from different participants. This is done to determine if data was correctly classified as belonging in the categories that emerged from the analysis.29,35 Abstraction allowed the researchers to create a vivid understanding and description of the participants’ experiences with walking during hospitalization.29 Fig. 1.0 provides an illustration of the abstraction that resulted from analysis of the data.

Fig. 1.0.

Abstraction from analysis.

Trustworthiness

Multiple strategies to ensure rigor and validity of the findings were used. A qualitative research team was used to analyze the data to decrease the risk of individual researcher bias and improve credibility of the findings.33,36,37 To increase validity of the results, purposive sampling was used to reach individuals who represented the population (older adults) and had knowledge and experience with the phenomena (admitted to a hospital).29 The unit of analysis was selected to be sufficiently broad to be considered as a whole, but small enough to provide relevant meaning to older adults’ experiences.37 Member checking was used to verify accuracy of the data analysis.37 At the end of each focus group, the researchers provided participants with a preliminary analysis of the prior meeting’s data. This was done to determine if subcategories and categories being developed adequately reflected their experiences and perceptions, and to protect against over-interpretation of the data.37 To further support credibility and dependability of the analysis, theoretical and methodological memos that captured the research teams ideas, insights and observations of the data were chronicled after each analysis session.57 Theoretical memos detailed how the research team derived meaning from the data while methodological memos identified steps the team would take, such as new questions to pose to the focus group members at upcoming meetings, to gather additional data.57 Finally, conformability, ensuring the data exemplifies the information that participants provided, was accomplished by using quotes from multiple individuals to support that interpretation of the data was representative of participants’ experiences.36,38,57

Results

Participants described their decisions about ambulating during a hospital stay as complex in terms of how, when, and where they would engage in walking, and the impact of the hospital environment on their decision to get up to walk. Complexity with deciding to walk was identified as the main category. Six generic categories related to the main category emerged: Uncertainty, Restriction Messaging, Non-Welcoming Space, Caring for Nurse and Self, Feeling Isolated, and Presenting Self.

Uncertainty

Uncertainty was described as not knowing if, when, and where they could go for a walk, and if walking would cause problems such as dislodging stiches, increasing pain, or depleting strength. Uncertainty seemed to act as a barrier to participants’ engaging in ambulation during hospitalization.

Often participants described simply not knowing if they could go for walks, when they could walk, and who they could ask for help if needed. All participants indicated healthcare providers (nursing staff and physicians) rarely talked about the importance of walking during their hospital stay or encouraged them to get out of bed. On the contrary, what they were told by nursing staff (registered nurses or certified nursing assistants) is that they needed permission to go for a walk or were cautioned about walking without a staff member accompanying them. Participants spontaneously stated that nursing staff caution was related to falls.

Interviewer: “Can you say more about why patients have to ask the nurse if they can go for a walk?”

Participant: “Its because of falls, they don’t want a fall” (focus group 2 participant 8)

However, no participant felt they were at risk for falls or that walking would precipitate a fall. In contrast, participants readily recognized if they did not get up to walk they would be at risk for a fall due to loss of muscle strength or would not be ready to go home. Limited communication or direction about whether or not they could get up to walk often resulted in participants either staying in their hospital room or not leaving their bed or chair.

“A lot of people sit there in the hospital or lay there in the hospital. And they’re waiting to be told what to do.” (focus group 2 participant 2)

Further, because walking was not discussed as a component of their medical care, participants assumed walking was not important or a priority, even when they personally felt walking was necessary for their recovery. Participants proposed several strategies that healthcare providers could use to provide information to patients about walking. These strategies included providing patients with daily information on their activity orders; how much and what type of activity (e.g., getting up to a chair, walking) they should or could engage in; or using visual reminders (e.g., writing on the white board in patient rooms) about how often and when they should be walk. Not knowing forced participants into a passive role as a patient. Some stated they felt completely dependent on the staff for any movement in and out of bed or a chair, within their hospital room, or to go out in the hallway.

Additionally, participants described not being told how to handle machines or tubes if they wanted to get up. Many felt confident that they could manage the equipment if instructed. Intravenous (IV) lines attached to pumps and urinary catheters were described as tethers that kept them in bed or in their hospital room. Because they did not know how to handle equipment, they became concerned about dislodging lines or tubes, or knocking over the IV pump. Not knowing how to handle tethers resulted in participants staying in their bed or room, instead of engaging in independent walking inside or outside of their room.

“I want to get up and walk, but what do I do with this thing? … You haven’t been catheterized before. Can I get up and walk with this tube [not] coming out? (focus group 2, participant 3)

All participants described wanting to leave the hospital as soon as possible. Being discharged home was their top priority. Therefore, not knowing when, where, and how they could engage in walking increased their concerns about causing problems that might delay their discharge.

For many participants causing problems was described as a threat that they would have to stay longer or go to a nursing home to recover. Others described concerns about feeling physically drained, experiencing increased pain, or becoming too weak if they walked during their hospital stay. Causing problems was also related to concerns about dislodging stiches, or undoing what was fixed (surgery).

“Some people are afraid, you know. Their fear that they’re going to damage themselves even more (focus group 3, participant 4)

“Concerned that you’re going to tear your stitches out or whatever they’ve fixed on you” (focus group 3 participant 5)

Restriction messaging

Many participants stated when there was discussion about getting up to walk, it centered on the nursing staff’s concern for falls. Therefore, the message participants received was about walking restriction. Participants readily recognized the nursing staff’s heightened concern about falls as they were repeatedly reminded to call for help with any physical movement, such as transferring in and out of bed or chair, or walking. One participant rejected the restriction and initiated her own walking program to prevent complications due to the hospital stay.

“I knew the dangers of not getting up to walk during my hospital stay. I just got up and started to move and did not wait for the staff to tell me to walk” (focus group 4, participant 6)

Messaging about restricted movement was delivered through multiple means: orally (by nursing staff), visually (signs posted in room), or auditory (motion sensor alarms put in bed and chair). Most annoying to participants were the auditory messages from setting off a motion sensor alarm. Participants described any movement activated the alarm, resulting in a voice coming over the room intercom system telling them to stay put, or having staff rush into their room to tell them to not move. Participants who had alarms activated on their bed or chair indicated they were very effective in restricting their movement. Many found the alarms offensive and unnecessary.

“ I found it was really intolerable. You know, I had an alarm on my bed. I couldn’t even get out of bed. I mean, really, I had an actual alarm.” (focus group 3, participant 8)

“If you have an alarm set on your bed, then you are …not supposed to get up and walk” (focus group 3, participant 7)

Non-Welcoming space

All participants described hospitals as non-welcoming environments for walking, due to physical layout and limited seating. Non-welcoming space was described as limited surroundings, danger zones, and limited seating. Participants readily discussed being limited in their surroundings due to unfamiliarity with the environment. Many were concerned about getting lost if they ventured beyond the hallway where their room was located. Often, there were no wayfinding maps in the unit or building to orient and direct participants. Some participants stated color-coding used to identify different locations in hospitals was confusing. This was especially true when colors changed, when 2 or 3 colors were present in one area, or when colors were in similar hues. Several indicated that if they knew where they were going on the inpatient unit, they would have been more comfortable walking beyond their room. Others described being limited in their surroundings, due to clutter in their room or hallways. Navigating their way around a bedside table, cords or hospital supplies was daunting. For many, the patient rooms were small and cramped, resulting in participants staying in bed or at best sitting up in a chair.

Many participants described danger zones in the hospital. Danger zones were areas where participants were unable to get help if needed, or were unable to get back to their room, due to fatigue. Danger zones could occur both inside and outside the patient room. Inside the patient room, the space between the bed and the bathroom was often described as a danger zone because participants did not have access to their call light to alert the staff if they needed help. Avoiding limited access to alert staff for help often restricted participants from independently using the bathroom.

“There’s no way to call for help in between the bed and the bathroom” (focus group 4, participant 10)

Danger zones were also present in hallways outside of the patient room. Because they were not walking much, participants worried that they would not be able to make it back to their rooms if they felt tired. They also did not have a means to alert the staff if they needed help. Additionally, hallways did not have resting spots. This limited their ability to pace activity or to “catch your breath,” making hallway walking more intimidating.

“You’re afraid, you can’t get too far, and you don’t know what’s going to happen”. (focus group 3, participant 1)

Participants also identified that seating was not optimal for their physical size or comfort. Many stated that their room either did not have a chair, or the chair was either too big or small to get in and out of easily, or lacked arm rests to help with transferring. For those who did walk in hallways, seating in common spaces was also not optimal for transferring or comfort. Because of limited seating, participants stated they restricted how far they would walk or simply stayed in bed.

“The one thing that I see poorly about them is the furniture is too low… It doesn’t have arms on it… I think that’s a deterrent” (focus group 4, participant 4)

Caring for nurse and self

Participants described a process of caring for self and caring for nurses as it related to ambulation. Participants cared for nurses by not asking to go for a walk. All participants described nurses as rushing in and out and only spending a few minutes with them at a time. The appearance of being busy signaled to participants that nurses had too much work. Because of this, participants described not wanting to “bother” the nurses about walking. Rather, they would wait until nurses initiated the conversation about getting out of bed or going for a walk. By not asking, participants were attempting to make the nurses’ job easier. Caring for nurses therefore acted as a barrier to participants initiating walking or keeping nurses accountable to ensure that walking occurred.

“I can’t bother them right now. They’re busy. I don’t want to interrupt.” (focus group 2, participant 6)

Participants also described nurses as “angels” and persons they could trust. They saw physicians as important in making decisions about their treatment plan. Nurses were the ones making sure everything got done and who they could turn to if they were concerned about the care they were receiving. Participants seemed to be concerned that placing high demands on nurses (asking to go for a walk) would irritate them and thus affect the type of care they received. Not asking the nurse to do more was a way they could ensure they had good quality care while in the hospital.

“When I’ve been in the hospital, the last thing I want to do is mess with the nurses, you know I don’t want to add to what they already have on their plate” (focus group 4, participant 11)

Some participants described needing to care for self to ensure that they were progressing and not getting weaker. Getting up to walk and attending to their own activities of daily living (e.g., bathing, dressing, and toileting) were strategies participants used to make sure they were maintaining or building strength. All participants expressed not wanting to stay in the hospital, as this was a disruption in their lives and a place where they were forced to be dependent on others. When participants cared for self, they shifted care as a means to assure that they would be ready to go home. Caring for self required participants to ignore requests by nursing staff to call for assistance with getting out of bed or going to the bathroom. Many reasoned that they would perform these tasks without help at home.

“I don’t see the need to call the nurse, I am able to go to the bathroom by myself… I do this at home.” (focus group 1, participant 5)

Feeling isolated

Participants often described an overwhelming sense of isolation during their hospital stay. Isolation was both physical, restricted to their room, and psychological, not feeling engaged or part of the healthcare team. Many stated the sense of isolation was a carryover from their experiences at home and was amplified by being confined to their room. All discussed being admitted to the hospital, assigned a room and a bed, and told to stay there. Not having the freedom to walk and connect with the environment and others increased their sense of isolation.

“A lot of people are isolated. They’re isolated when they go into the hospital, they’re isolated again in this room” (focus group 4, participant 2)

During the focus group there was robust discussion about social stimulation as a valuable component of recovery. Getting out of their room or having a common space to go to or have meals in was seen as a way to interact with other patients, and an opportunity to provide and receive support and encouragement from patients and staff.

“The common room or the common meal area so that we … can interact and therefore help each other to get further.” (focus group 4, participant 8)

“It’s nice when you are walking in the hallway and nurses say, ‘look at you, you are doing great’” (focus group 5 participant 10).

Participants also felt isolated from decisions regarding their care. They valued and wanted to be considered part of the team with their healthcare providers. Often participants were told what was going to happen to them and had little say in decisions regarding treatment options or care after discharge. Being part of the team was important for their hospital experience and seen as critical to their recovery and progression after discharge.

“Laying there like a slab of meat,… waiting to be told what to do. They (patient) [should be] part of the team that is making them better. And I don’t know anyone who sees a hospital in that way.” (focus group 4, participant 6)

Presenting self

Physical appearance impacted whether or not participants felt comfortable walking outside of their room. Looking disheveled, weak, or struggling made participants feel vulnerable and exposed to others (visitors and hospital staff). Having enough time to groom and dress was important for participants to prepare for walking outside of their hospital room.

“My mother was worried about her appearance and that other people would be watching her struggling, … that made her less likely to get up” (focus group 1, participant 7)

Participants spontaneously discussed how hospital gowns and restrictions to their undergarments made them uncomfortable with venturing out in public spaces. Not being able to wear undergarments was described as fear that they would expose their bodies to others. Many stated they wished they could wear their own clothing. Having to wear a hospital gown acted as a barrier to engaging in ambulation.

“What’s that old phrase? If you’re going to the hospital, park your humility at the front door because you’re going to be exposed all over the place” (focus group 4, participant 10)

Discussion

This study provides an understanding of older adults’ perceptions of hospitals and how this impacts their decisions of whether or not to engage in ambulation during an admission. Numerous barriers that impacted participants’ decisions were identified that spanned from the physical environment (e.g., signage, lack of adequate seating, equipment) to threats to their personal dignity (e.g., appearance, autonomy with decision making). Surprising findings included the sense of isolation older adults felt during their hospital stay, as well as the importance they placed on caring for the nursing staff by not burdening them with requests to ambulate.

The impact of the hospital environment on functional decline in older adults has been described in the literature for over three decades. Studies have found that environmental hazards such as raised beds, cluttered hallways, and limited orientation clues keep older adults in their rooms, discourage movement, and threaten functional independence after discharge.39–41 Identifying hospitals as “hostile environments”42 was based on clinician experience and not on older adult patient experiences. Our findings provide empirical evidence that older adults do indeed perceive hospitals as an unwelcoming space for physical movement. In addition to lack of wayfinding cues, we found that older adults easily identify specific danger zones that exist within hospitals that preclude them from walking. The concept of patient-perceived danger zones that restrict mobility in hospitals has not been previously described.

Participant discussion of the lack of any chairs, or chairs that could accommodate a safe transfer and promote mobility in their hospital room, was concerning. This finding is consistent with others who described that older adults identified a lack of chairs or chairs disappearing from their rooms as a barrier to mobility.39 A substantial amount of literature has been published on falls in hospitals related to causes, risk factors and interventions. Suboptimal chair height and seating has been identified as a physical environmental risk factor for falls in hospitals.43 Others have found that older adults view inadequate seating as an indication that it is not safe to move while in the hospital, often resulting in older adults either staying in bed or limiting their mobility to their hospital room.39 Lack of ambulation and movement during a hospital stay have been correlated with increase in falls, loss of functional status, and an increase in fear of falls post discharge for older adult patients.4,39,44 Therefore, access to functional seating is necessary for promoting mobility during a hospital stay, and critical for improving an older adult’s confidence to self-manage after discharge, decreasing fall risk, and decreasing risk for functional decline.39,45 To our knowledge, current intervention studies to promote older adult patient ambulation during a hospital stay have not integrated environmental adaptations such as adequate seating, interesting walking pathways, or wayfinding signage. Additional research on the impact of physical design of hospitals on mobility restriction versus mobility promotion should be conducted.

Recent studies found that older adults often have negative experiences during a hospital stay. A meta-synthesis conducted by Bridges, Collins, Flatley, Hope and Young (2020) highlighted that older adults often feel powerless during hospitalization and are hesitant to ask for information or help from hospital staff.46 Older adults also perceive that they are low priority and do not wish to be seen as demanding. We had similar findings in our study. All participants spontaneously described that they did not want to be a burden on the nursing staff or bother them by asking to go for a walk. It seemed that not asking for help was a strategy to ensure that nurses viewed them positively. This finding is consistent with others who identified that older adult patients want to be liked by the staff because it improves their chances of getting good care.47–49 Studies have also found that older adults experience overwhelming feelings of vulnerability and worthlessness during a hospital admission.50,55 Our participants described that their physical appearance impacted their sense of vulnerability. Not being able to properly groom and lacking access to clothing that did not risk exposure of their body acted as barriers to older persons willingness to move outside of their hospital room. Additional research is needed to understand the older adult patient experience with hospitals and ambulation during an admission.

Studies conducted on the impact of hospital ambulation on older adults have largely focused on physical function (ADLs) and healthcare utilization outcomes, such as length of stay and readmission rates. Only a few studies have measured impact of mobility on psychological outcomes, but these have not been conducted primarily in older adult (>65 years) populations. Of the results available, mobility during a hospital stay has been shown to decrease depression and anxiety among adult cancer51 and stroke patients.52 Our study found participants had an overwhelming sense of isolation during their hospital stay, often being restricted to their rooms and only having contact with busy staff. Participants identified that social stimulation, where they received and provided encouragement, was necessary for their recovery. Only one study identified that nurses use social stimulation, pointing out to older adults their progress with ambulation, as a means to provide patients with hope that they are improving.53 Adding measures for depression, anxiety, quality of life, and satisfaction with care will provide a more comprehensive and holistic understanding of the impact of ambulation for older adults during a hospital stay. Without such additional research, it will be difficult to build patient-centered interventions that engage older adults as partners to improve ambulation during hospitalization.

This study provides detailed information about how older adults experience walking during a hospital stay and identifies barriers that prevent them from initiating ambulation. Our results provide critical findings that fill a gap in current knowledge and will inform future intervention studies to improve older adult patient ambulation.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. The participants represent older adults who live in the Midwest region of the United States (US) and may not represent experiences of older adults who live in other geographic regions of the US or in other countries. However, our participants were able to recall and describe their experiences when admitted to hospitals in different parts of the US. Further, our findings are consistent with other publications, which utilized samples of older adults from a variety of regions in the US.

Participants were also asked to recall past experiences with hospitalization. Although all participants were able to vividly describe events related to ambulation during a hospital stay, capturing the richness of older adult experiences closer to a hospital discharge may have enhanced details provided in the interviews.

We conducted five focus group sessions, each lasting 90 min with 11 participants as our method for data collection. Some may argue that 11 participants in a group limit individuals from sharing their personal experience, thus impacting data quality. However, common recommendations for focus group size vary from a minimum of four to a maximum of 12.54 Therefore, our sample size for focus groups meets standard recommendations. All participants actively engaged in each session and contributed to the richness of the data by building and expanding on information shared by group members.

Finally, this study was conducted pre-COVID. Older adult patients may experience additional challenges to ambulation due to the need for strict social isolation and distancing during the pandemic.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to acknowledge the members of our Stakeholder/Focus Group. Without them these findings would not be possible.

Funding

This work was supported by the NIH CTSA at UW-Madison grant UL1TR000427, as well as the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health’s Wisconsin Partnership Program, WPP-ICTR grant #3086.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have conflict of interest to disclose

Declaration of Interests

The Authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2020.08.005.

References

- 1.Brown C, Redden D, Flood K, Allman R. The underrecognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1660–1665. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mudge A, McRae P, Hubbard R, et al. Hospital-associated complications of older people: a proposed multicomponent outcome for acute care. J. American Geriatric Society. 2019;67:352–356. 10.1111/jgs.15662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Sinoff G, Gur-Yaish N, Srulovici E, Admi H. Low mobility during hospitalization and functional decline in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:266–273. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown C, Friedkin R, Inouye S. Prevalence and outcomes of low mobility in hospitalized older patients. J. American Geriatric Society. 2004;52:1263–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aberg A, Sidenvall B, Hepworth M, O’Reilly K, Lithwell H. On loss of activity and independence, adaptation improves life satisfaction in old age: a qualitative study of patients’ perceptions. Quality Life Research. 2005;14:1111–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure. JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Gur-Yaish N, Tonkikh O, Sinoff G. Hospital associated functional decline: the role of hospitalization processes beyond individual risk factors. J. American Geriatric Society. 2015;63:55–62. 10.1111/jgs.13193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sourdet S, Lafont C, Rolland Y, Nourhashemi F, Andrieu S, Vellas B. Preventable iatrogenic disability in elderly patients during hospitalization. JAMDA. 2015;16:674–681. 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zisberg A, Syn-Hershko A. Factors related to the mobility of hospitalized older adults: a prospective cohort study. Geriatr Nurs (Minneap). 2016;37:96–100. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cortes OL, Delgado S, Esparza M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental studies: in-hospital mobilization for patients admitted for medical treatment. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75:1823–1837. 10.1111/jan.13958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuys S, Dolecka U, Guard A. Activity level of hospital medical inpatients: an observational study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55:417–421. 10.1016/j.archger.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher S, Kuo Y, Graham J, Ottenbacher K, Ostir G. Early ambulation and length of stay in older adults hospitalized for acute illness. Arch. Intern. Med 2010;170(21):1942–1943. 10.1001/archinternalmed.2010.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodilsen Pederson, Beyer Petersen, Lawson-Smith Andersen, Bandholm Kehlet. Twenty-four hour mobility during acute hospitalization in older medical patients. J. Gerontology MEDICAL SCIENCES. 2013;68(3):331–337. 10.1093/Gerona/gls165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kortebein P, Ferando A, Lombeida J, Wolfe R. Effect of 10 days of bed rest on skeletal muscle in healthy older adults. JAMA. 2007;297(16):1772–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown C, Williams Woodby L, Davis L, Allman R. Barriers to mobility during hospitalization from the perspectives of older patients and their nurses and physicians. Society Hospital Medicine. 2007;2:305–313. 10.1002/jhm.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hastings SN, Choate AL, Mahanna EP, et al. Early mobility in the hospital: lessons learned from the STRIDE program. Geriatrics. 2018;3:61. 10.3390/geriatrics3040061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King B, Pecanac K, Krupp A, Liebzeit D, Mahoney J. Impact of fall prevention on nurses and care of fall risk patients. Gerontologist. 2018;58(2):331–340. 10.1093/geront/gnw156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caraballo C, Dharmarajan K, Krumholz H. Post hospital syndrome: is stress of hospitalization causing harm. Rev Esp Cardio (Engl Ed). 2019;72(11):896–898. 10.1016/jj.rec.2019.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter J, Ward C, Wexler D, Donelan K. The association between patient experience factors and likelihood of 30-day readmission: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2018;27(9):683–690. 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manary MP, Bloulding W, Staelin R, Glickman SW. The patient experience and health outcomes. New England J. Medicine. 2013;368(2):201–203. 10.1056/NEJMp1211775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krumholz H Post-hospital syndrome: an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. New England J. Medicine. 2013;368:100–102. 10.1056/NEjMp1212324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rawl S, Kwan J, Razak F, et al. Association of trauma of hospitalization with 30-day readmission or emergency department visit. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(1):38–45. 10.1001/jamainternalmed.2018.5100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boltz M, Capezuti E, Shabbat N, Hall K. Going home better not worse: older adults’ views on physical function during hospitalization. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16:381–388. 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourret EM, Bernick LG, Cott CA, Kontos PC. The meaning of mobility for residents and staff in long-term care facilities. J Adv Nurs. 2001;37:338–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bridges J, Flatley M, Meyer J. Older people’s and relatives’ experiences in acute care settings: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:89–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liebzeit D, Bratzke L, Boltz M, Purvis S, King B. Getting back to normal: a grounded theory study of function in post-hospitalized older adults. Gerontologist. 2019. gnz057; 10.1093/geront/gnz057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Seben R, Reichardt L, Essink D, van Munster B, Bosch J, Buurman B. “I feel worn out, as if I neglected myself”: older patients’ perspectives on post-hospital symptoms after acute hospitalization. Gerontologist. 2019;59(2):315–326. 10.1093/geront/gnx192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King B, Steege L, Winsor K, VanDenbergh S, Brown C. Getting patients walking: a pilot study of mobilizing older adult patients via a nurse-driven intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(10):2088–2094. 10.1111/jgs.14364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krueger RA, Casey MA Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. 4. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitzinger J. Qualitative Research: introducing focus groups. BMJ. 1995;311:299–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stewart DW, Shamdasani PN, Rook DW. Focus Groups. Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morse JM, Field PA. Qualitative Research Methods For Health Professionals. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashemnezhad H. Qualitative content analysis research: a review article. J. ELT and Applied Linguistics. 2015;3(1):54–62. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boeije H. A purposeful approach to constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Qual Quant, 36, 391–409. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elo S, Kaariainen M, Kanste O, Polkki T, Utriainen K, Kyngas H. Qualitative content analysis: a focus on trustworthiness. Sage Open. 2014. 10.1177/2158244014522633. January-March: 1-10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nursing Education Today. 2004;24:105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boltz M, Resnick B, Capezuti E, Shuluk J. Activity restriction vs. self-direction: hospitalised older adults’ response to fear of falling. Int J Older People Nurs. 2014;9(1):44–53. 10.1111/opn.12015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiou S, Chen L. Towards age-friendly hospitals and health services. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49(Suppl 2):S3–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmer R, Counsell S, Landefeld S. Acute Care for Elders Units. Disease Management Health Outcomes. 2003;11:507–517. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer R. The acute care for elders unit model of care. Geriatrics. 2018;3:59. 10.3390/geriatrics3030059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miake-Lye I, Hempel S, Ganz D, Shekelle P. Inpatient fall prevention programs as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med 2013;158:390–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalisch B, Tschannen D, Hee Lee K. Missed nursing care, staffing and patient falls. J Nurs Care Qual. 2012;27(1):6–12. 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e318225aa23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loyd C, Beasley TM, Miltner R, Clark D, King B, Brown C. Trajectories of community mobility recovery after hospitalization in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:1399–1403. 10.1111/jgs.15397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bridges J, Collins P, Flately M, Hope J, Young A. Older people’s experiences in acute care settings: systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;102. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henderson S. Power imbalance between nurses and patients: a potential inhibitor of partnerships in care. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:501–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maben J, Adams M, Peccei R, Murrells T, Robert G. ‘Poppets and parcels’: the links between staff experiences of work and acutely ill older peoples’ experience of hospital care. Int J Older People Nurs. 2012;7(2):83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Penny W, Wellard S. Hearing what older consumers say about participation in their care. Int J Nurs Pract. 2007;13:61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bridges J, Nugus P. Dignity and significance in urgent care: older people’s experiences. J. Research in Nursing. 2010;15(1):43–53. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chang PH, Lai YH, Shun SC, et al. Effects of a walking intervention on fatigue-related experiences of hospitalized acute myelogenous leukemia patients undergoing chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:524–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cummings TB, Collier J, Thrift AG, Bernhardt J. The effect of very early mobilization after stroke on psychological well-being. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:609–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Doherty-King B, Bowers B. Attributing the responsibility for ambulating patients: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(9):1240–1246. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carlsen B, Gleton C. What about N? A methodological study of sample-size reporting in focus group studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koskenniemi J, Leino-Kilpi H, Suhonen R. Respect in the care of older patients in acute hospitals. Nurs Ethics. 2013;20(1):5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kyngas H, Mikkonen K, Kaariainen M. The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research. Switzerland: Springer; 2020. Doi: 10.1007978-3-030-30199-6. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Birks M, Chapman Y, Francis K. Memoing in qualitative research: probing data and processes. J. Research in Nursing. 2008;13:68–75. 10.1177/1744987107081254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]