Abstract

Recent ethnobotanical studies have raised the hypothesis that religious affiliation can, in certain circumstances, influence the evolution of the use of wild food plants, given that it shapes kinship relations and vertical transmission of traditional/local environmental knowledge. The local population living in Jhelum District, Punjab, Pakistan comprises very diverse religious and linguistic groups. A field study about the uses of wild food plants was conducted in the district. This field survey included 120 semi-structured interviews in 27 villages, focusing on six religious groups (Sunni and Shia Muslims, Christians, Hindus, Sikhs, and Ahmadis). We documented a total of 77 wild food plants and one mushroom species which were used by the local population mainly as cooked vegetables and raw snacks. The cross-religious comparison among six groups showed a high homogeneity of use among two Muslim groups (Shias and Sunnis), while the other four religious groups showed less extensive, yet diverse uses, staying within the variety of taxa used by Islamic groups. No specific plant cultural markers (i.e., plants gathered only by one community) could be identified, although there were a limited number of group-specific uses of the shared plants. Moreover, the field study showed erosion of the knowledge among the non-Muslim groups, which were more engaged in urban occupations and possibly underwent stronger cultural adaption to a modern lifestyle. The recorded traditional knowledge could be used to guide future development programs aimed at fostering food security and the valorization of the local bio-cultural heritage.

Keywords: ethnobotany, wild food plants, traditional food, religious diversity, bio-cultural heritage, local resources

1. Introduction

Wild food plants have remained an important ingredient of traditional food basket systems especially in remote communities around the globe [1]. However, due to dramatic socio-cultural shifts local communities are facing and global climate change, dependence on wild food plants has drastically decreased in many areas. Food industrialization and globalization have severely impacted traditional food systems, especially in rural communities [2]. Consequently, traditional/local environmental knowledge (TEK) linked to wild food plants is becoming more and more endangered, and in some places of the world, it has already disappeared [3]. In recent decades, scientists have recorded several complex TEK systems associated to wild food plants, especially in marginalized areas. However, very few ethnobotanical field studies have focused on the cross-cultural and cross-regional comparison of TEK associated to wild food plants, despite the fact that cultural diversity shapes TEK [4,5,6,7,8,9].

In many regions of the world, inhabitants of rural areas depend on wild plants as food [10] and a large number of wild plant species occurring in a great variety of habitats are consumed [11,12]. Recent works have addressed the role that religious affiliation may play in shaping folk wild food plant uses and cuisines, since this factor shapes in many areas of the world kinship relations and the vertical transmission of plant and gastronomic knowledge [13,14,15]. However, all over the world wild plants have been more frequently consumed in the past [10]. There are over 20,000 species of wild edible plants in the world, yet fewer than 20 cultivated species now provide 90% of our main staples [16].

The collection and culinary use of wild plants for food are part of the bio-cultural heritage of local communities and therefore can foster their future sustainability [17,18]. During the last decades, a large number of publications have documented the ethnobotany of wild food plants, but only sporadically scholars have tried to articulate the evaluation of socio-cultural and economic factors possibly influencing foraging [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]; simultaneously, research on specific domains of the plant foodscape, such as that of fermentation of local plants (sometimes wild) is exponentially growing [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45].

Pakistan comprises remarkable natural resources, and a large variety of religious faiths and linguistic communities using a wide range of wild food plants [46]. Many rural communities in Pakistan live closely attached to their natural resources [47] and wild food plants are often consumed for food [48]. A few comparative studies have very recently addressed the cross-cultural dimension of wild food plants gathering and use in Pakistan, and highlighted the role of diverse linguistic and religious groups [49,50,51].

In order to further evaluate this trajectory, the current study focused on six religious groups (Sunni and Shia Muslims, Christians, Hindus, Sikhs, and Ahmadis—also named Qadiani in official Pakistani documents, despite this term is considered sometime derogatory by the community), speaking eleven different languages (Urdu, Punjabi, Phtohari, Gojri, Pahari, Hindko, Saraiki, Sindhi, Pashto, Kashmiri, and Hindi) in Jhelum District, Punjab, NE Pakistan.

The main aim of our research was to record local knowledge related to wild food plants and also to provide baseline documentation to help local stakeholders revitalizing their food traditions. We particularly explored the impact of religious and linguistic affiliation on the gathering, utilization and consumption of wild food plants in 27 villages in Jhelum district, Punjab, Pakistan, hypothesizing that there could be some differences between different faiths.

The specific research objectives of this study were:

to explore and record the diversity of wild food plants gathered in Jhelum,

to evaluate the local food and possible traditional perceptions,

to compare the mentioned wild food plants among the six selected religious faith groups in order to possibly understand cross-cultural similarities and differences and to better understand the cultural context supporting the use of wild food plants found in Jhelum district.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

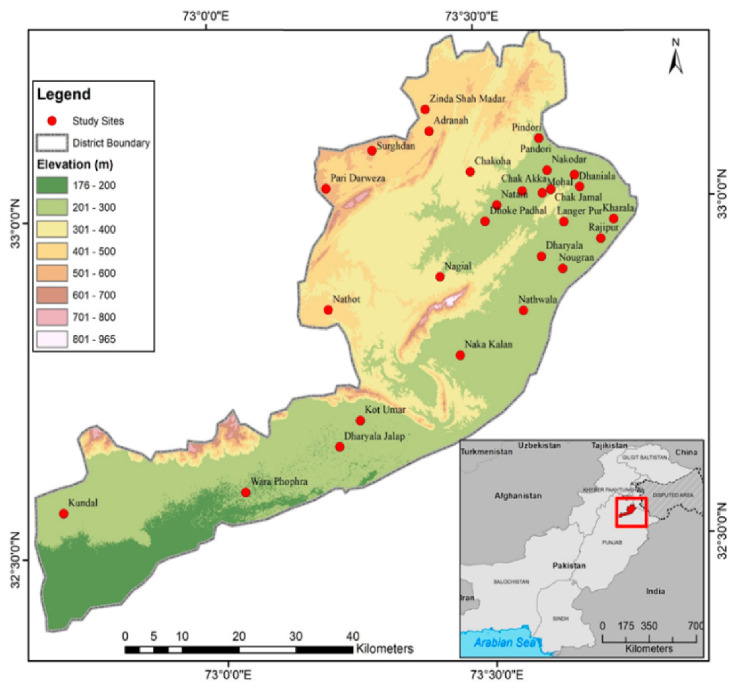

The study area of Jhelum district is located North of the river Jhelum and is bordered by Rawalpindi district in the North, Sargodha and Gujrat districts in the South, Azad Jammu and Kashmir in the East, and Chakwal district in the West [52,53]. The population of the district is 1.22 million, and 71% of the population lives in rural areas, while the remaining 29% are urban [54]. The climatic conditions are semi-arid, warm-subtropical, characterized by warm summers and severe winters. Jhelum is a semi-mountainous area (Figure 1), with a mean annual rainfall of 880 mm. The annual average temperature reaches 23.6 °C. Jhelum is home to the world’s second largest salt mine (Khewra) covering about 1000 ha [53,55]. The people of Jhelum have a diverse culture with distinct modes of life, traditions, and beliefs [56]. The ethnic groups of the area show a strong connection to wild plants which often have cultural and medicinal significance [57].

Figure 1.

Diverse landscapes of Jhelum study area, NE Pakistan; (a–d): landscape depicting leading plant species associations (indicator species: Acacia modesta, Acacia nilotica, Prosopis juliflora, Ziziphus numularia, Justicia adhatoda and Dodonea viscosa); (e–g): exposed sedimentary bedrock stratification (age: Pre-Cambrian to Pliocene; composition: limestone, sandstone, shale, and dolomite) and sandy loam textured soil; (h): rangeland for livestock grazing.

The study was conducted in 27 remote villages (Figure 2), all of which contained rivers, mountains, forests, salt mines, and valleys. Some typical and important attributes including landscapes, vegetation, geology and soil, and rangeland are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 2.

The map of the study area displaying the studied sites/village locations.

2.2. Field Study

The ethnobotanical field research was conducted from March to November 2020. Study participants were selected through snowball sampling focusing on middle-aged and elderly inhabitants (range: 40–90 years old), especially farmers, herders, and housewives. Selected interviewees belonged to different religious faiths and different language groups. Twenty participants (men and women) from each religious group were selected and participated in the survey. The characteristics of the study participants from the 27 visited villages and their different socio-cultural and economic attributes are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants.

| Religious Group | Sunnis | Shias | Hindus | Sikhs | Christians | Ahmadis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brief historical sketch | Islam arrived in the 8th century, the majority converted to Sunni Islam during in the 11th–16th centuries; minor fractions migrated from Middle Eastern and African countries | The majority converted to Shia Islam during the 16th–18th centuries; minor fractions migrated from the Middle East | Autochthonous | Converted around the 15th century | Emerged with British colonialism in the 18th and 19th centuries | Converted in the 19th century |

| Approx. number of inhabitants in Jhelum District, Pakistan (2020) | 1.01 million | 0.21 million | 2000 | 5000 | 7000 | 6000 |

| Study villages | Dhoke Padhal, Dharyala, Chakoha, Mohal, Natain, Zinda Shah Madar, Surghdan, |

Chak Jamal, Kundal, Pindori, Nathot |

Chak Akka, Nathwala, Nakodar, Pari Darweza |

Dhaniala, Nougran, Adranah |

Nagial, Kot Umar, Dharyala Jalap |

Naka Kalan, Rajipur, Kharala, Wara Phophra, Langer Pur |

| Spoken languages | Pothwari, Kashmiri, Pashto | Saraiki, Pahari, Pothwari | Hindku, Hindi, Sindhi | Punjabi, Gojri | English, Urdu | Urdu |

| Inter-marriages | Rarely exogamic with Shia | Rarely exogamic with Sunni | Endogamic | Strictly endogamic | Endogamic | Strictly endogamic |

| Main occupations | Forestry and farming | Forestry and farming | Farming and urban occupations | Pastoralism and urban occupations | Horticulturalism and urban occupations | Horticulturalism |

| Estimated average socio-economic status of the study participants | Middle | Middle | Low | Low | Low | Middle low |

| Number of study participants | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Percent of female participants | 30% | 25% | 25% | 45% | 45% | 30% |

| Overall mean age of the study participants | 47 | 53 | 64 | 66 | 59 | 69 |

Prior to starting an interview, oral informed consent was obtained, and the Code of Ethics of the International Society of Ethnobiology [58] was followed. Semi-structured interviews were conducted in the national language, Urdu, and some local languages (Punjabi, Saraiki, Pothohari, Gojri, Hinko, Pahari, Kashmiri, Sindhi, and Hindi) with the help of translators. The information collected focused on the gathering and consumption patterns of wild plants as cooked vegetables, raw snacks, salads, herbal drinks, recreational herbal teas, jams, and for fermentation following Kujawska and Łuczaj [59]. Particular questions were focused on the use of wild plants in daily food habits or in food fermentation, and the consumption of edible wild food plants [49]. Local names of collected taxa were recorded in eleven different local languages.

During the interviews qualitative ethnographic data was documented following Termote et al. [60]. The recorded wild food plants were collected from the study area and were identified using the Flora of Pakistan [61,62,63]. After correct identification, each taxon was given a voucher specimen number and deposited in the Herbarium of the Department of Botany, University of Gujrat, Punjab, Pakistan. For nomenclature, the Plant List database [64] was followed for plants, and the Index Fungorum [65] for the single recorded mushroom taxon. The plant family nomenclature follows the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group [66].

2.3. Data Analysis

The documented data was stored in two main binary data spreadsheets (1. Species gathered for any use; 2. Species gathered for specific use) across the six local religious communities and compared through Venn diagrams and pairwise Jaccard’s dissimilarity using the R Statistical Package [67,68,69].

The Jaccard Index (JI) was calculated as:

| J(X, Y) = |X∩Y|/|X∪Y| |

X = Individual set of plant usages documented by group X

Y = Individual set of plant usages documented by group Y

By using JI, Jaccard’s distance (JD) was calculated as:

| D(X,Y) = 1 − J(X,Y) |

Moreover, a qualitative comparison with other studies on wild food plants carried out in Pakistan [49,50,51,52,70,71,72] was conducted.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Reported Wild Food Plants and Their Uses

A total of seventy-eight taxa (77 vascular plants and one mushroom) were gathered and consumed in different ways in the study area (Table 2). The most commonly used wild food plant species were native, with the exception of Agave americana, Amaranthus spinosus, Sonchus oleraceus, Tephrosia purpurea, Trigonella corniculata, Salvia moorcroftiana, Salvia nubicola, Solanum incanum, Chenopodium album, and Portulaca quadrifida, which were grown as herbs or grew wild as weeds in anthropogenically disturbed locations. A total of nine different typologies of food preparations were identified: chutneys (a family of spicy condiments and sauces prototypical of South Asian cuisines); cooked vegetables; fermented preparations; herbal drinks (plant material infused in cold water); herbal teas (plant material infused in hot water); jams; raw snacks (consumed singly, mostly in the field at the collection site); salads (raw plants consumed at the dining table as a starter and/or in conjunction with other food items); and seasoning/spices.

Table 2.

Recorded wild food plants and their local uses.

| Plant Species, Family, and Voucher Specimen Number | Local Names | Parts Used | Gathering Area and Season | Local Culinary Uses and Quotation Frequency | Frequency of Consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Acacia modesta Wall.; Leguminosae; 827/MM//2020 |

PholaiUR, PN, PT, HN PaliPH, GJ Jangli KikerSR PalosaPS Angrezi BaburSN Kiker KulKM |

Gum, Leaves |

DL, FO, HS, RS, SP, WP; March–April | FermentationHN**, SI* JamSH*, SN |

Very commonSH CommonHN RareSN Very rareSI |

|

Acacia nilotica (L.) Delile; Leguminosae; 783/MM//2020 |

KikarUR, PN, PT, HN, HI KikrSR, PH, GJ, KM KikharPS Sindhi BaburSN |

Gum, Pods |

DL, FO, HS, RS, SP, WP; March–April | FermentationSH**, QA* JamSI**, SN |

Very commonSH CommonQA RareSN Very rareSI |

|

Aerva javanica (Burm. f.) Juss. ex Schult.; Amaranthaceae; 544/MM//2020 |

BoenUR ThooPN BoiPT, PH, GJ, KM Niki BoienSR ShorakaiPS SparokaiPS BoohSN Safed BuiHI |

Flowers, Leaves, Seeds |

DL, FO, GR, HS, SP, SL, WP; February–April | CookingCR**, QA*, SH, SN** | Very commonSH CommonSN RareCR Very rareQA |

|

Agave americana L.; Asparagaceae; 675/MM//2020 |

Jangli Kwar GandalUR LaphraPN, PH, GJ Kanwar PharaSR Desi Kwar GandalPT Kamal GandKM KeuroSN ZargiraPS Kamal CactusHN Bin KatoraHI |

Leaves | AL, DL, FO, GL, GR, RS, SP, WP; August–September | CookingSN, SH, HN*, QA ** | Very commonSH

CommonSN RareQA Very rareHN |

|

Allium carolinianum DC.; Amaryllidaceae; 409/MM//2020 |

Jangli PyazUR, KM, HN Jangli GandaPN, PT, GJ Jangli WasalSR KhokhaiPS |

Bulbs | DL, FO, GL, SP, SH; August–September | CookingCR*, SN* SaladQA*, SH* |

Very commonSN

CommonCR RareSH Very rareQA |

|

Amaranthus spinosus L.; Amaranthaceae; 787/MM//2020 |

CholaiUR KonjelPN Surkh GunahrPH, PT BattoSR GhinyarGJ, KM ChalveryHN SarmayPS KalgaSN GuleeKM GanharHN Kanta ChaulaiHI |

Leaves | AL, GL, HS, RS, SL, SH, WP; August–September | CookingCR*, SH***, SI**, SN | Very commonSN CommonSI RareCR Very rareSH |

|

Amaranthus viridis L.; Amaranthaceae; 878/MM//2020 |

Jangli ChoolaiUR TandlaPT, GJ, PH TandulaSR TanduliPN LuturSN SaagPS RanzakaPS GanyarHN GanarKM |

Leaves | AL, GL, HS, RS, SL, SH, WP; August–September |

CookingQA*, SH, SI**, SN | Very commonSN

CommonSI RareSH Very rareQA |

|

Boerhavia repens L.; Nyctaginaceae; 816/MM//2020 |

Looni BootiUR LornkiPN, PT LorankSR BakhroSN |

Leaves | AL, FO, GL, GR, HS, RS, SH, WP; August–September | CookingSN**, SH, SI**, CR** | Very commonSN

CommonSH RareCR Very rareSI |

|

Cannabis sativa L.; Cannabaceae; 669/MM//2020 |

BhangUR, SN, SR, GJ, PH, KM PangPN, PT, HN KammPS |

Leaves, Seeds |

AL, GL, GR, RS, SH, WP, WL; March–April |

Herbal drinkSN, SH*, SI**, QA | Very commonSN

CommonSH RareQA Very rareSI |

|

Capparis decidua (Forssk.) Edgew.; Capparaceae; 532/MM//2020 |

KarirUR PichuUR KarinhaPN, GJ KariSR KareenhPT, PH, KM KareerHN DelaGJ, KM KreetaPT KareenhSR KiraPS JabaPS KirarSN KairHI |

Fruits | DL, FO, GR, HS, SP; August-September |

FermentationSN** JamSH* Raw snacksSI**, CR* |

Very commonSH CommonSN RareCR Very rare SI |

|

Caragana ambigua Stocks.; Leguminosae; 409/MM//2020 |

Jangli PhaliUR, PN, PT, GJ BaiphliSR ZarayPS |

Flowers, Pods |

RS, SL, SH, WP; June–July | CookingCR* Raw snacksSN*, SI SaladHN** |

Very commonSN CommonSI RareCR Very rareHN |

|

Chenopodium album L.; Amaranthaceae; 748/MM//2020 |

Jangli BathooUR Desi BathooPN, PT, PH, GJ Desi BattoonSR SurmaPS SormiPS Spin SobaPS ButhiaPS UdharamHN ChilSN BathwaKM GoyaloHI |

Branches, Leaves | AL, FO, GL, GR, HS, RS, SL, SH, WP; March–April, August–September |

CookingSN**, SI***, CR*, SH** | Very commonSN CommonSI RareCR Very rareSH |

|

Chenopodium murale L.; Amaranthaceae; 805/MM//2020 |

KarndUR, PH, GJ, KM Karwa BathooPN BathooPT Kora BatoonSR Thor SurmaPS LulurSN KurundHN GoyaloHI |

Branches, Leaves | FO, GL, GR, HS, RS, SL; March–April | CookingSN, SH**, CR*, QA | Very commonSI CommonSN RareSH Very rareQA |

|

Chenopodium vulvaria L.; Amaranthaceae; 611/MM//2020 |

Sufaid BathooUR, KM Jangli BatoonPN, PT, PH Chitta BatoonSR LulurSN KurundHN GoyaloHI |

Branches, Leaves |

AL, DL, RS; March–April, August–September |

CookingSN*, SH, SI*, QA* | Very commonSI CommonSN RareSH Very rareQA |

|

Cirsium arvense (L.) Scop.; Asteracae; 761/MM//2020 |

LeehUR LehiPN, PT LehPH LiahGJ WanvahriSR Da Khwarak AzghaiPS KandiaraSN KundKM |

Stems | DL, FO, GL, GR, HS, SP, SH, WP; March–April | Raw snacksSN*, SH***, HN*, QA* | Very commonSH CommonQA RareHN Very rareSN |

|

Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad.; Cucurbitaceae; 638/MM//2020 |

TummaUR Kaud TumbhaPN, GJ, PH Kor TummaPT, SR, KM PirpandyanPS MarghonePS Tarha MarhaPS AndrainPS HanzalPS TroohSN IndrayanHI |

Fruits | AL, DL, FO, GL, GR, HS, RS, SP, SL, SH, WP; May–June | FermentationCR*** JamSI** SpiceSN*, SH*** |

Very commonSI CommonSN RareCR Very rareSH |

|

Commelina benghalensis L.; Commelinaceae; 795/MM//2020 |

KaniPN, SR JawarzaalPS ChuraKM |

Leaves | FO, GL, HS, RS, SL, SH, WP, WL; March–April | CookingSN, SH*, SI***, QA** | Very commonSH CommonSN RareSI Very rareQA |

|

Convolvulus arvensis L.; Convolvulaceae; 728/MM//2020 |

LehiUR LehliPN, GJ Hiran KahriPT, PH VanvaihreSR ParvatyPS NaaroSN Speaker BootiHN HirapadiKM |

Leaves | AL, FO, GL, GR, RS, SH, WL; March–April | CookingSH, SI**, CR**, QA | Very commonSH CommonQA RareCR Very rareSI |

|

Corchorus depressus (L.) Stocks; Malvaceae; 591/MM//2020 |

Bahu PhaliUR BaephliSR MunderiSN |

Whole plant | DL, GR, HS, MS, SP, SL; March–April | Herbal drinkSN, SI***, CR**, QA* | Very commonSI CommonQA RareSN Very rareCR |

|

Corchorus tridens L.; Malvaceae; 417/MM//2020 |

PhaliUR, PN, PT, GJ, KM DadiSR |

Pods | GL, GR, HS, MS; March–May | Herbal drinkSN, SH*, SI*, QA* | Very commonSH CommonQA RareSN Very rareSI |

|

Cucumis melo L.; Cucurbitaceae; 527/MM//2020 |

ChibarUR, PN ChibbarhSR ChibharPH, PT, GJ, KM MiteroSN |

Fruits | AL, GL; June–July |

ChutneySN*** FermentationQA** JamSI* Raw snacksHN*** SaladSN*** |

Very commonSI CommonHN RareQA Very rareSN |

|

Digera muricata (L.) Mart.; Amaranthaceae; 694/MM//2020 |

TandlaUR TandoliPT, GJ, PH LeswaKM TandalaPN Mareeri SaagSR AthiHN TartaraPS Nazam HooraPS LulurSN ChanchaliHI LahsuvaHI |

Branches, Leaves |

FO, GL, GR, HS, RS, SH, WP, WL; August–September |

CookingSI*, CR**, SN*, QA | Very commonSI CommonSN RareCR Very rareQA |

|

Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin & Clemants; Amaranthaceae; 856/MM//2020 |

Desi BathooUR BathooPN, PT Jangli BattoonSR Babre NagdiPS BathuGJ, PH BathwaHN, KM |

Branches, Leaves |

AL, DL, FO, GL, GR, HS, RS, SL, SH, WP; August–September | CookingSH**, CR**, SN*, QA** | Very commonSH CommonSN RareCR Very rareQA |

|

Fagonia indica Burm. f.; Zygophyllaceae; 842/MM//2020 |

JamahonUR, PN, PT DamanhPN, KM, GJ Jawanh BootiSR DramahoSN |

Whole plant | DL, FO, GR, HS, RS, SP, SL; July–August | Herbal drinkSN*, SH, SI**, QA | Very commonSH CommonSI RareQA Very rareSN |

|

Galium aparine L.; Rubiaceae; 589/MM//2020 |

WanwairPN, PT, GJ Wanwair BootiSR, PH CochnaPS LahndraKM |

Leaves | AL, FO, GL, GR, HS, RS, SL, SH, WP; June–July | Herbal DrinkSN**, SI, CR, QA | Very commonSI CommonQA RareSN Very rareCR |

|

Gisekia pharnaceoides L.; Gisekiaceae; 644/MM//2020 |

Balu Ka SagUR Jangli SagPN, PT, SR |

Leaves | AL, FO, GL, GR, RS, SP, SH, WP; July–August |

CookingSN*, SH**, SI**, CR** | Very commonCR CommonSH RareSN Very rareSI |

|

Indigofera hochstetteri Baker.; Leguminosae; 499/MM//2020 |

KanoUR RaariPN, PT, GJ, PH MareeriSR ZindKM JhillSN |

Flowers, Seeds |

GL, GR, HS, MS; August–October | JamSH, SI*, CR*, QA | Very commonSI CommonQA RareSH Very rareCR |

|

Lathyrus aphaca L.; Leguminosae; 844/MM//2020 |

Jangli MatterUR, PN, PT Jangli MattriSR Marghayo HpayPS KukarmanyPS Jangli PhaliKM |

Pods | AL, FO, GL, RS, SH, WP, WL; September–October | FermentationHN**, SI*** Raw snacksQA**, SH*** |

Very commonSH CommonQA RareHN Very rareSI |

|

Lathyrus sativus L.; Leguminosae; 572/MM//2020 |

Jangli MatterUR, PN, PT Jangli MattriSR Marghayo HpayPS KukarmanyPS Jangli MatarSN |

Pods | AL, FO, GL, HS, RS, WP, WL; March–April | CookingCR**, SN** Raw snacksSH*, SI** |

Very commonSN CommonSH RareCR Very rareSI |

|

Launaea procumbens (Roxb.) Ramayya & Rajagopal; Asteracae; 821/MM//2020 |

DodakUR, PN

BhathalaPT HundPH, GJ, KM DodhkSR SondrashiPS AlakooPS BhattarSN |

Leaves | AL, FO, GL, GR, RS, SH, WP, WL; March–April | Raw snacksSN***, SI*, CR**, QA | Very commonSI CommonSN RareQA Very rareCR |

|

Lepidium apetalum Willd.; Brassicaceae; 505/MM//2020 |

Jangli Khoob KalanUR BashkyPS, PH, PT Desi HalyunSR BurchanHN HanonPS HarfPS HaleemPS |

Leaves | FO, GL, HS, MS, SH, WP, WL; July–August | CookingSN, CR**, HN*, QA** | Very commonSN CommonCR RareQA Very rareHN |

|

Lepidium draba L.; Brassicaceae; 459/MM//2020 |

SennaUR Suchi SennaPN, PH, GJ, PT Koori SanaSR Ghora WalSN DadhwalSN |

Leaves, Seeds |

DL, FO, GR; April–July | Raw snacksQA*, SI* SaladHN*, SN* |

Very commonSN CommonQA RareHN Very rareSI |

|

Malva neglecta Wallr.; Malvaceae; 665/MM//2020 |

Sitara SunchalPN, SR TikalayPS Jungali SoxalKM SonchalUR, HN, PT, PH KhubasiHI |

Leaves | AL, DL, FO, GL, GR, RS, SH, WP, WL; March–April | CookingSN**, SH***, SI*, QA* | Very commonSI CommonQA RareSN Very rareSH |

|

Malva parviflora L.; Malvaceae; 510/MM//2020 |

Jangli SonchalUR, PN, PT, HN Jungali SoxalKM Jangli KhubasiHI |

Fruits | AL, DL, FO, GL, GR, RS, SH, WP, WL; March–April | CookingSH, QA* Herbal teaCR*, SN** |

Very commonSH

CommonQA RareCR Very rareSN |

|

Malva sylvestris L.; Malvaceae; 564/MM//2020 |

Jamni PhoolUR MethraiPN, PS, SR KhawazamaryPS SamchalPT, PH, KM KhabaziHN |

Leaves | RS, SH; April–May | CookingSH**, SI***, QA, SN** | Very commonSN CommonSI RareSH Very rareQA |

|

Mentha arvensis L.; Lamiaceae; 693/MM//2020 |

PodinaUR, PN, PT, PH PodnaSR ShinshobaiPS PodinaGJ, HN |

Leaves | AL, GL; March–April, August–September |

ChutneySH***, SN***, SI** CookingSH*, SN**, SI**, CR* Herbal teaHN**, SI** SpiceCR**, SH*, SN* |

Very commonHN CommonCR, SI RareSI Very rareSH |

|

Mentha longifolia (L.) L.; Lamiaceae; 698/MM//2020 |

Jangli PodinaUR, PN, KM Chita PodnaSR, HN, PT, PH VaylanaiPS ShinshobaiPS BareenaSN |

Leaves | FO, GL, HS, SL, SH, WL; May–June, August–September |

ChutneySN**, SH** CookingSN*, SH* Herbal teaSI***, CR** SpiceCR*, SI**, QA** |

Very commonSI CommonCR RareQA Very rareSN |

|

Mentha pulegium L.; Lamiaceae; 659/MM//2020 |

Jamni PodinaUR, PN, PT, PH Desi PodnaSR PudinaKM |

Leaves | AL, FO, GL, HS, RS, SL, SH, WL; March–April, August–September |

ChutneyHN*, SI** Herbal teaQA**, SN** |

Very commonHN CommonSN RareSI Very rareQA |

|

Mentha royleana Wall. ex Benth.; Lamiaceae; 631/MM//2020 |

Sofaid PodinaUR, PN, PT, PH Chitta PodnaSR, HN Jangli PodinaKM |

Leaves | AL, FO, GL, HS, RS, SL, SH, WL; March–April |

ChutneySH**, SN* CookingSH*, SN* Herbal teaCR***, HN* |

Very commonSN CommonSH RareHN Very rareCR |

|

Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata (Wall. & G. Don) Cif.; Oleaceae; 746/MM//2020 |

KahouUR, PN, PT KaoGJ, KM, PH, SR ShwawanPS KhunaPS KaowHN KahoHN |

Fruits | AL; August–September | Raw snacksQA**, SH**, SI*, HN* | Very commonSH CommonSI RareQA Very rareHN |

|

Opuntia dillenii (Ker Gawl.) Haw.; Cactaceae; 699/MM//2020 |

KhashiUR ThorPH, GJ, KM Peeli SaroonPN Peela SaroonPT Peela RayeaSR WorakiPS ShershamPS Hoob SublanPS HakseerPS |

Leaves | AL, GL, HS, RS, SH, WP; March–April | CookingSN**, SH*, HN*, QA | Very commonHN CommonSH RareQA Very rare SN |

|

Oxalis corniculata L.; Oxalidaceae; 732/MM//2020 |

Peeli BootiUR

Choti lonakPN LonakSR TherwashkaPS Bibi ShaftalaPS TarookayPS Khati ButiHN KhatiKM |

Leaves | AL, FO, GL, GR, HS, RS, SH, WP, WL; February–March | ChutneyCR**, QA* CookingSI**, SN** |

Very commonCR CommonSI RareQA Very rareSN |

|

Phoenix sylvestris (L.) Roxb.; Arecaceae; 501/MM//2020 |

Jangli KhajoorUR, PN, PT, HN Desi KhajoorGJ, PH, KM PindSR Chotti KhagoorPS KhajiSN KhajurHI |

Fruits | AL, DL, GL, RS; June–July | JamQA* Raw snacksSN*, HN, SH |

Very commonSH CommonSN RareHN Very rareQA |

|

Physalis divaricata D. Don; Solanaceae; 569/MM//2020 |

Jungli BerryUR Jangli TamatorPN, SR HundusiGJ, PT, PH, KM Band MalkhovjPS DelhuuSN |

Fruits | FO, GL, HS, SL, SH, WP; August–September | Raw SnacksSN*, SI*, HN**, QA** | Very commonSI CommonQA RareHN Very rareSN |

|

Pistia stratiotes L.; Araceae; 515/MM//2020 |

Jall KhumbiUR, HI, KM

Jall ShamkalaGJ, PT, PH NargisPN, PT JaruSN |

Leaves | WP; March–April | CookingSN*, SH, SI*** SaladQA* |

Very commonSN CommonSI RareSH Very rareQA |

|

Polygonum plebeium R.Br.; Polygonaceae; 531/MM//2020 |

Gorakh PanUR DroonkPN BandokiPS Gull SrahPS KhowarSN Chimati SaagHI |

Stems | AL, FO, GL, GR, HS, MS, RS, SL, SH, WP, WL; March–April | CookingSN**, SI**, CR*, HN | Very commonSI CommonCR RareHN Very rareSN |

|

Portulaca oleracea L.; Portulacaceae; 865/MM//2020 |

Kulfa LonakUR, PN Lorniki BootiPT, GJ, KM Lorni BootiSR VarhoriPS LoonkSN KhurfaHN |

Leaves, Stems |

FO, GL, HS, RS, SH, WP, WL; August–September | CookingSN**, SH*, HN*, QA** | Very commonSH

CommonHN RareSN Very rareQA |

|

Portulaca quadrifida L.; Portulacaceae; 753/MM//2020 |

Lornak BootiUR, PN LorankiPT, GJ, PH LonakSR WakhoraiPS PakharaiPS LoonkSN LunakKM KolfaHN |

Leaves, Stems |

FO, GL, GR, HS, MS, RS, SL, SH, WP; August–September | CookingSH**, SN*, CR*, QA | Very commonCR CommonSN RareSH Very rareQA |

|

Prosopis cineraria (L.) Druce; Leguminosae; 745/MM//2020 |

JandUR, PN, PT, PH, KM JandiSR KandiSN Jangli MatarKM JhandHI KhejriHI |

Gum, Pods |

DL, FO, GR, HS, RS, SP, SL, WP; August–September | FermentationSN*, CR** JamQA**, SH* |

Very commonQA CommonSH RareCR Very rareSN |

|

Prosopis juliflora (Sw.) DC.; Leguminosae; 547/MM//2020 |

KikarUR Phari KikarPN, PT, GJ, KM, SR Sindhi KikarPH KikarPS Angrezi BaburSN Velayti KikarHN Jungli KikarHI |

Gum, Pods |

AL, FO, GR, HS, RS, WP; August–September |

FermentationSI, HN*, CR JamSH**, SN* |

Very commonSH CommonSN RareHN Very rareSI, CR |

|

Rhynchosia minima (L.) DC.; Leguminosae; 855/MM//2020 |

Jangli LobiaUR, PN, PH, KM Jangli ArwanPT HerdalSR |

Pods | AL, FO, HS, RS, WP, WL; March–April | CookingSN, SH*, SI**, CR | Very commonCR CommonSI RareSN Very rareSH |

|

Rumex dentatus L.; Polygonaceae; 812/MM//2020 |

KhatkalPN, PT, PH, KM Jangli PalakUR, GJ, SR Sarkari PalakPS ZamdaPS Jangli PalakSN HullahHN OlaHN |

Leaves | AL, FO, GL, HS, RS, SL, SH, WP, WL; March–April | CookingSN**, SH**, SI**, HN | Very commonSI CommonHN RareSH Very rareSN |

|

Salvadora oleoides Decne.; Salvadoraceae; 690/MM//2020 |

JallUR

VanGJ, KM JhalPT, PH PiluPN,SR KhabbarPS KhabarSN KallijariHN |

Fruits | DL, FO, GR, HS, SP, WP; August–September |

ChutneyHN*, CR* FermentationSH*, SN** JamSH*, HN*, CR* |

Very commonSH CommonSN RareCR Very rareHN |

|

Salvadora persica L.; Salvadoraceae; 747/MM//2020 |

PeloUR, SR, GJ KhabarSN PiluPN, PT, PH, KM DiyarSN KallijariHN JaalHI |

Fruits | DL, GR, RS, SP, SL, WP; August–September | FermentationSH*, SN* JamSI*, HN** |

Very commonSH CommonSN RareSI Very rareHN |

| Salvia moorcroftiana Wall. ex Benth.; Lamiaceae; 530/MM//2020 |

Tokham BelagaUR LapraPN BelangooSR DersaiPS SidraiPS Jungle TamookhKM ShwankoSN KallijariHN Khesari DaalHI |

Stems | FO, HS, SL, SH, WP; May–June | Raw snacksSN***, SH, QA **, CR* | Very commonSH CommonQA RareCR Very rareSN |

|

Salvia nubicola Wall. ex Sweet; Lamiaceae; 841/MM//2020 |

HernarPN DarshoolPS KallijariHN Khesari DaalHI |

Leaves | FO, HS, RS, SH, WP, WL; August–September | CookingSH**, SI*, HN***, QA | Very commonSI CommonSH RareHN Very rareQA |

|

Senna italica Mill.; Leguminosae; 479/MM//2020 |

Ghora WalSN | Seeds | GL, GR, HS, MS, RS; April–June | Raw snacksSN*, SH*, SI, QA** | Very commonSN CommonQA RareSH Very rareSI |

|

Senna occidentalis (L.) Link; Leguminosae; 576/MM//2020 |

LobiaUR, PN, GJ, KM Desi ArwanSR, PT, PH Ghora WalSN |

Pods | AL, FO, HS, RS, WP, WL; March–April | CookingSN**, SH, CR*, QA | Very commonCR CommonSN RareQA Very rareSH |

|

Sisymbrium irio L.; Brassicaceae; 750/MM//2020 |

Khud-e-KalanKM KhashiUR, PN, PT, PH Peeli BootiSR WorakiPS ShershamPS Hoob SublanPS HakseerPS KhubkalanHN KhakasiHN |

Leaves | AL, GL, HS, RS, SH, WP; March–April | CookingSN, SH**, SI***, HN** | Very commonSI CommonSN RareHN Very rareSH |

|

Solanum americanum Mill.; Solanaceae; 636/MM//2020 |

MakaoUR Kainch MainchPN Katch MatchPT MohkriPH, GJ, KM KarveloonSR Kach machaoPS MalkhovjPS MalgabaiPS |

Fruits | AL, FO, GL, GR, HS, RS, SH, WP; June–July | ChutneySI*, SH Herbal drinkSN**, SI Raw snacksHN*, SH, SI*, SN** |

Very commonSH CommonSI RareHN Very rareSN |

|

Solanum incanum L.; Solanaceae; 727/MM//2020 |

Jangli KhashiUR Jangli BainganPN, PT MahokariPS Kori WalSR MahoraSN |

Fruits | FO, GL, HS, SH, WP; June–July | ChutneySH, SN* Raw snacksQA**, HN** |

Very commonSH CommonQA RareHN Very rareSN |

|

Solanum surattense Burm. f.; Solanaceae; 758/MM//2020 |

Neeli Khurd KataiUR Choti KandiariPN MahoriPT, GJ, PH, KM Kandiari WalhSR MarkondayePS SpeenazghaiPS KanderiSN MohkreeHN |

Fruits | DL, FO, GR, HS, MS, RS, SP, SL; October–November | Raw SnacksSN, CR*, HN*, QA* | Very commonHN CommonQA RareCR Very rareSN |

|

Solanum villosum Mill.; Solanaceae; 415/MM//2020 |

MakoUR, SN Kaach MachPN, PT, GJ, KM KarveloonSR |

Fruits | GL, GR, HS, MS; March–May | ChutneySI*, HN* Raw snacksSH**, SN** |

Very commonSI CommonSH RareSN Very rareHN |

|

Sonchus asper (L.) Hill; Asteracae; 666/MM//2020 |

BhattalUR Malai BootiPN DodhiPT, PH, GJ DodhakSR Soon LattiPS KasniSN DodalKM |

Leaves | DL, FO, GL, HS, RS, SL, SH; March–April | CookingSH**, HN***, SN | Very commonSH

CommonSN Very rareHN |

|

Sonchus oleraceus (L.) L.; Asteracae; 713/MM//2020 |

BhattalUR Malai BootiPN DodhakPT Peeli DodhakSR TarizhaPS Soon DodakPS KasniSN |

Leaves | AL, FO, GR, RS, SH; March–April | CookingSN*, SI**, HN***, QA** | Very commonSI CommonQA RareHN Very rareSN |

|

Stellaria media (L.) Vill.; Caryophyllaceae; 796/MM//2020 |

Kangni BootiUR Phoolan CheeriPN Cheeri PtaPT StalliPH, GJ, KM Chitti BootiSR VilaghoriPS Badsha SabaPS Bin BatorhiPS Buch-BuchaHI |

Leaves | AL, FO, GL, HS, MS, RS, SL, SH, WP; March–April | CookingSN***, SH** Herbal teaCR**, SI |

Very commonSH CommonSN RareCR Very rareSI |

|

Tephrosia purpurea (L.) Pers.; Leguminosae; 429/MM//2020 |

Bansa-BansuPN, PT, PH, GJ, KM SarphookaPS HaldriSR MaheeroSN Ban NilHI |

Pods | GL, GR, HS; March–May | CookingSN**, SH*, SI, QA* | Very commonSI CommonSH RareQA Very rareSN |

|

Tribulus terrestris L.; Zygophyllaceae; 539/MM//2020 |

PakhraPS, PT, KM BhakhraUR, SR BakhroSN MelaiPS GhokruHN |

Fruits | DL, FO, GL, GR, HS, MS, RS, SP, SL, SH, WP; August–September | Herbal teaSN*, SH, SI**, HN* | Very commonSH CommonSI RareHN Very rareSN |

|

Trigonella anguina Delile; Leguminosae; 568/MM//2020 |

Jangli MeethreUR, PN, PT,GJ, SR Jungle MathKM |

Leaves, Seeds |

AL, DL, FO, GL, GR, HS, RS, SH, WP, WL; March–April | FermentationSH**, HN*, SI* Raw snacksSN |

Very commonSH CommonHN RareSN Very rareSI |

|

Trigonella corniculata Sibth. & Sm.; Leguminosae; 615/MM//2020 |

MeethreUR, PN, PT,GJ, SR Jungle MathKM |

Leaves, Seeds |

AL; March–April | FermentationQA*, CR, SN*, SH* | Very commonCR CommonQA RareSN Very rareSH |

|

Veronica anagallis-aquatica L.; Plantaginaceae; 834/MM//2020 |

Hazar DaniUR Obo SabaPS |

Leaves | AL, FO, GL, HS, RS, SH, WP; March–April | CookingSN***, SH, SI*, QA* | Very commonQA CommonSI RareSH Very rareSN |

|

Vicia sativa L.; Leguminosae; 767/MM//2020 |

Jangli LobiaUR Jangli RewariPN, GJ Jangli RawanSR MutriKM, PT, PH PervathaPS ChilowPS |

Pods | AL, FO, GL, HS, SL, SH, WP, WL; March–April | CookingSN**, SH*, SI**, CR** | Very commonSN CommonSH RareCR Very rareSI |

|

Withania coagulans (Stocks) Dunal; Solanaceae; 741/MM//2020 |

PaneerUR Jangly ChanaPT AkriPN, PH, SR KhamzoraPS AshwgandhasSN Asgandh NagoriSN |

Leaves, Fruits |

DL, FO, GL, SP, SH; March–April | Herbal drinkSN, SH, SI*, CR | Very commonSH CommonSI RareCR Very rareSN |

|

Ziziphus jujuba Mill.; Rhamnaceae; 726/MM//2020 |

BairiUR, PN Seo BairPT, SR Jand BeriPH, GJ BeraPS Moti BerPS KarkanraPS BerSN BerKM |

Fruits | DL, FO, GL, GR, HS, RS, SP; August–September | Raw snacksSN**, HN***, SI**, SH** | Very commonSI CommonHN RareSN Very rareSH |

|

Ziziphus nummularia (Burm. f.) Wight & Arn.; Rhamnaceae; 612/MM//2020 |

Jangli BairiUR, PN, GJ Kathy BeerPT, SR KarkanrPS Chotti BerPS AnanePS Bada BeraPS Jhangugli BerSN Jahri BerHN |

Fruits | FO, GL, HS, RS, SP; April–May | Raw snacksSN**, HN***, CR**, SH** | Very commonSH CommonHN RareSN Very rareCR |

|

Ziziphus oxyphylla Edgew.; Rhamnaceae; 409/MM//2020 |

Surkh BairUR, PN Saib BairSR, PH, PT, GJ HeilaneiyPS PhitniHN |

Fruits | FO, GL, HS, RS, SP; April–May | Raw snacksSN*, SH*, SI***, CR* | Very commonSI

CommonCR RareSN Very rareSH |

|

Ziziphus spina-christi (L.) Desf.; Rhamnaceae; 413/MM//2020 |

Jangli BairUR Jhar BeriPN, PT, GJ, KM Jangali BairSR BerSN |

Fruits | GL, GR, HS, MS, RS; March–June | Raw snacksSN*, SI*, SH*, CR* | Very commonCR CommonSH RareSN Very rareSI |

|

Coprinus comatus (O.F. Müll.) Pers.; Agaricaceae; 400/MM//2020 |

KhumbhiUR, PN, PT, GJ, SR GuchiPS KlikichokPS |

Arial parts | GL, GR, HS; August–September | CookingSN*, SH, SI*, HN** | Very commonSI

CommonSH RareSN Very rareHN |

Gathering areas: AL: arable land, DL: dry land, FO: forest, GL: grassland, GR: graveyard, HS: hilly slopes, MS: mountain summits, RS: roadside, SP: sandy places, SL: scrubland, SH: shady places, WP: paste places, WL: wet land; Local Languages: UR: Urdu, PN: Punjabi, PT: Pothwari, PH, Pahari, GJ, Gojri, HN: Hindko, SR: Saraiki, SN: Sindhi, PS: Pashto, KS: Kashmiri, HI: Hindi; Religious faith: SN: Sunnis, SH: Shias, SI: Sikhs, HN: Hindus, CR: Christians, QA: Ahmadis (Qadiani); Quotation frequency in percent: 1–25% = without asterisk, 26–50% = *, 51–75% = **, 76–100% = ***.

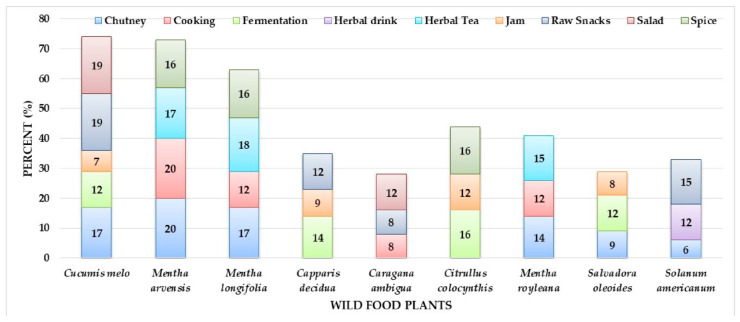

The most commonly quoted wild food plants and the typologies of their food preparations are reported in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Most commonly used wild food plants and their uses.

The most important site for the gathering of wild food plants were grasslands, found sometimes at high elevations, where people normally bring animals for grazing. Summer herders were the most knowledgeable ethnobotanical informants and this show the importance of the link between resilience of wild food plant knowledge and the survival of pastoralist activities. However, the transmission of ethnobotanical practices from elders to the younger generation is continuously decreasing due to the generation gap and fast changing lifestyle. With the modernization of life, the younger generation is moving towards cities for education and business opportunities, which is one of the major reasons for the decline of TEK described in many ethnobotanical studies.

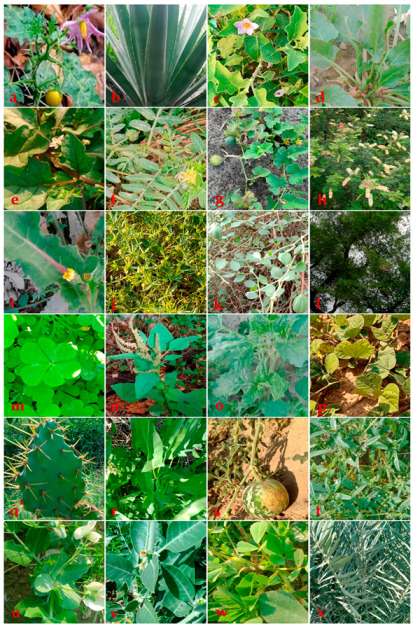

Some important wild food plants (Figure 4) and dishes prepared by the visited communities were available for photographing (Figure 5). Traditional culinary processing included cooking the plants as vegetables (43 mentions), followed by raw snacks (33), confirming what documented in other ethnobotanical studies too [73,74,75]. Raw snacks were eaten especially by transhumant herders, and it has been shown that herding develops specific linkages between humans and their surrounding ecosystem [76,77,78,79]. Herding is also linked to the use of particular types of wild food plants: for example, in Iraq and Kurdistan shepherds consumed more raw snacks than nearby horticulturists [9,76]. Moreover, pastures have been documented as very important gathering habitats of wild food plants [80,81].

Figure 4.

Some examples of wild food plants of Jhelum district: (a) Solanum surattense; (b) Agave americana; (c) Solanum incanum; (d) Rumex dentatus; (e) Solanum americanum; (f) Tribulus terrestris; (g) Cucumis melo; (h) Acacia modesta; (i) Sonchus asper; (j) Fagonia indica; (k) Capparis decidua; (l) Ziziphus jujuba; (m) Oxalis corniculata; (n) Amaranthus spinosus; (o) Chenopodium murale; (p) Rhynchosia minima; (q) Opuntia dillenii; (r) Convolvulus arvensis; (s) Citrullus colocynthis; (t) Gisekia pharnaceoides; (u) Lathyrus sativus; (v) Withania coagulans; (w) Trigonella corniculata; (x) Phoenix sylvestris.

Figure 5.

Traditional culinary uses of wild food plants by different linguistic and religious communities reported from the study area: (a) mixture of black pepper and Mentha royleana; (b) mixture of chilies and Mentha pulegium; (c) powdered Citrullus colocynthis; (d) powedered Mentha arvensis in yogurt; (e) bread made with rice flour with Opuntia dillenii pulp; (f) rice cooked with Amaranthus viridis seeds and Cucumis melo as salad; (g) herbal drink made with Cannabis sativa; (h) jam made by Prosopis cineraria fruits.

Leaves were the most used plant part (38 times used), especially in salads, herbal teas, herbal drinks, as raw snacks, in chutneys, and as cooked vegetables. One third of the reported plants (27 taxa) were only gathered during the spring season.

It was noted that sweet fruits in particular were consumed as raw snacks especially by local communities with a herding lifestyle. Thirty wild food plants were consumed as raw snacks by all religious faith groups, especially Capparis decidua, Caragana ambigua, Cucumis melo, Lathyrus aphaca, Lathyrus sativus, Phoenix sylvestris, Salvadora persica, Solanum americanum, Solanum incanum, Solanum villosum, Ziziphus jujube, Ziziphus nummularia, Ziziphus oxyphylla, and Ziziphus spina-christi, many also earlier reported by Sõukand and Kalle [82]. Although Solanum americanum was recognized as containing toxic alkaloids [83], especially in its fruit [84], informants used fruits as raw snacks without reporting any toxic effects. Similarly, some other important food preparations in the study area were herbal drinks, salads and chutney (Figure 5).

On a global scale, it has been found that folk knowledge has been decreasing, mostly due to modern lifestyle changes and urbanization [50,71,85,86,87,88,89,90]. Gathering wild food plants is linked to local biodiversity and especially local cultural practices [91] and in our field study wild plant knowledge among younger informants was limited, similar to what was found in many other studies, for example, Kalle and Sõukand [92].

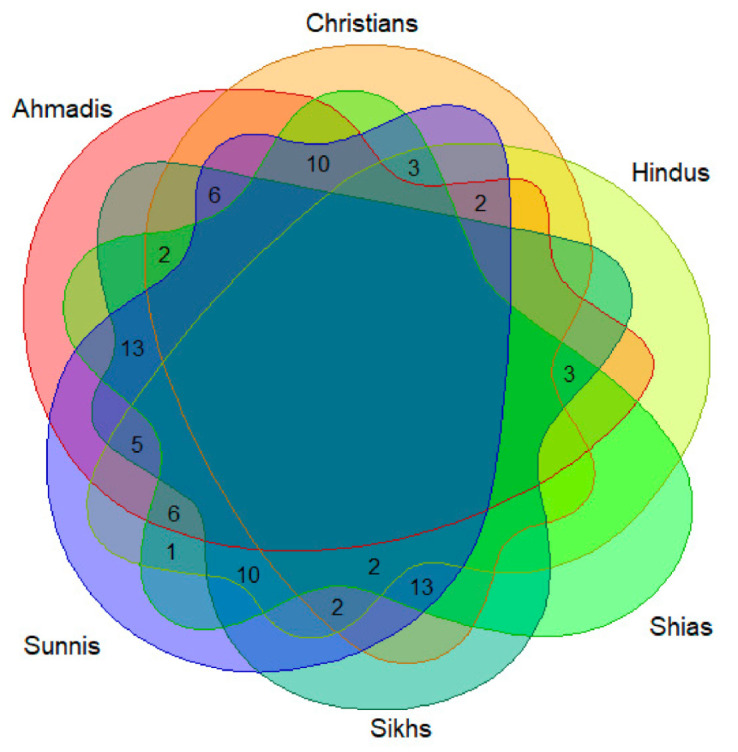

3.2. Cross-Religious Comparison

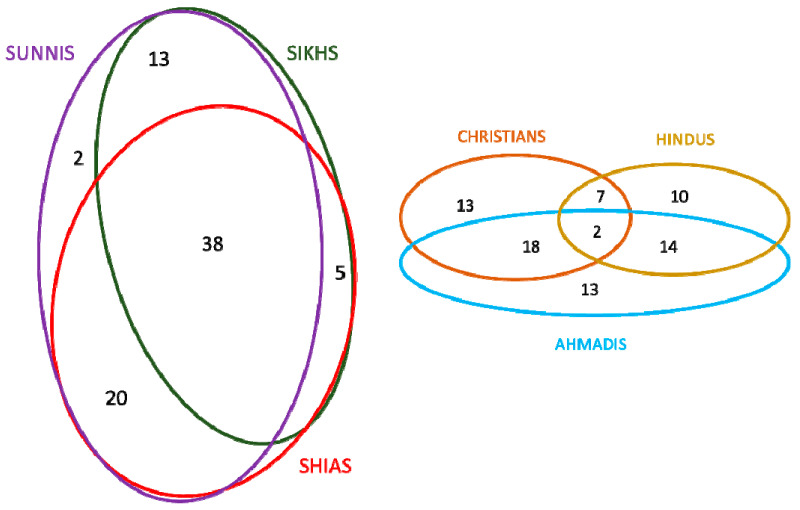

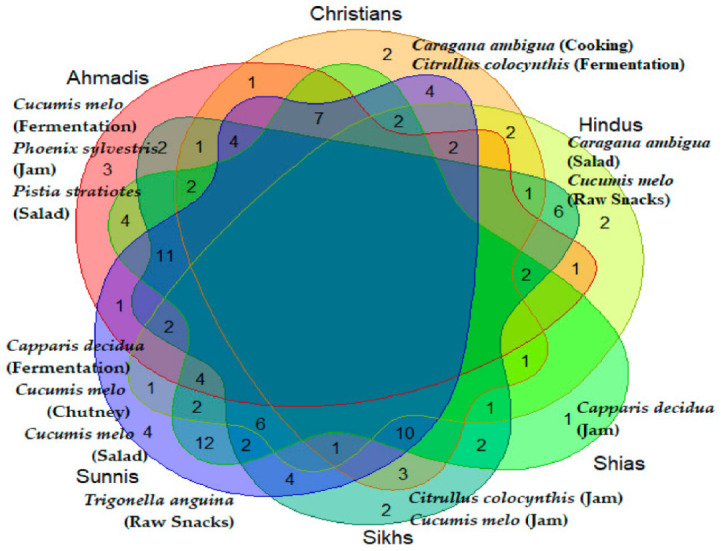

Cross-religious comparison of the used wild food plants (Figure 6) shows a remarkable homogeneity and the absence of any plant cultural markers (i.e., plants used by one group only); at the same time, however, not a single taxa is used by all the six considered groups and the majority of recorded wild food plants are used by three to four groups.

Figure 6.

Venn diagram showing the overlaps of the recorded wild food plants among the six considered groups.

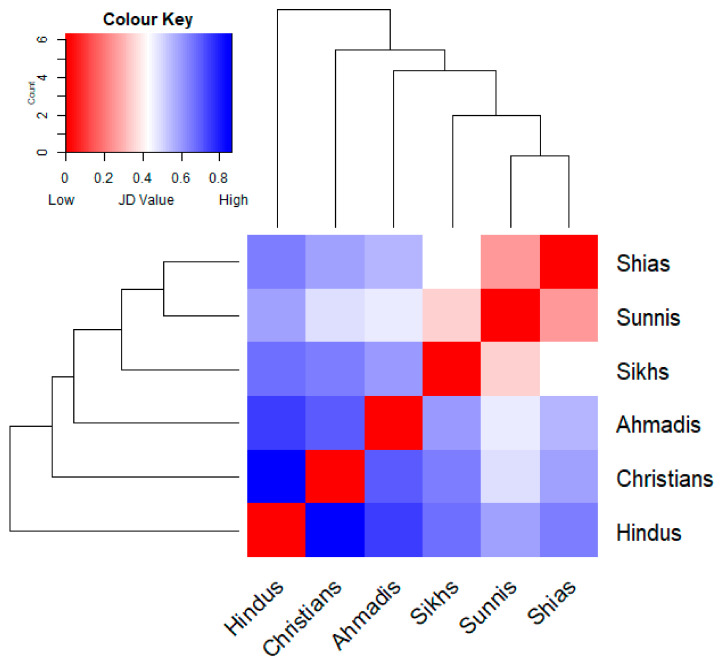

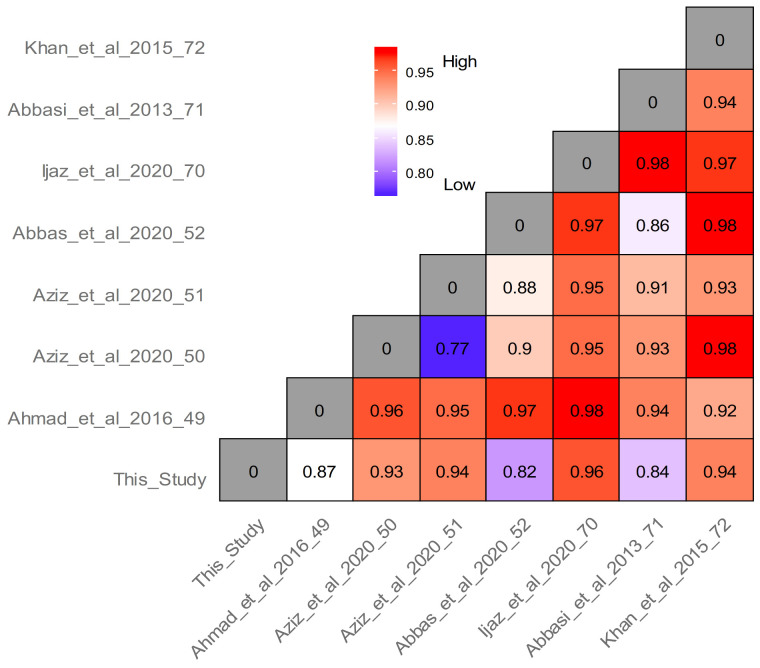

However, the Jaccard’s distance heat map (Figure 7) shows high dissimilarity between some groups. While both Muslim groups, Shias and Sunnis, appeared to be closest in their selection of the wild food plants, Hindus and Christians are the most distant.

Figure 7.

Hierarchical clustering tree coupled with heat map depicting Jaccard Dissimilarity Indices calculated by comparing the wild food plants quoted by the six considered groups.

The heat map (Figure 7) allows us to distinguish two easily comparable clusters within the six religious groups: a subgroup of Shias, Sunnis, and Sikhs, which used the highest number of plants (from 56 to 73) and a subgroup using far fewer taxa (Christians, Hindus, and Ahmadis (from 34 to 47). Bearing in mind that Shias and Sunnis together used all 78 listed taxa, there is a clear pattern of dissimilarity among the second subgroup (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Intuitive best fit Venn diagrams comparing the recorded wild food plants among the six religious groups divided into two clusters.

Sunnis, using a slightly higher number of taxa than Shias, had more similarities with all the other groups. This could be due to the fact that the Sunni faith is the dominant one in the study area.

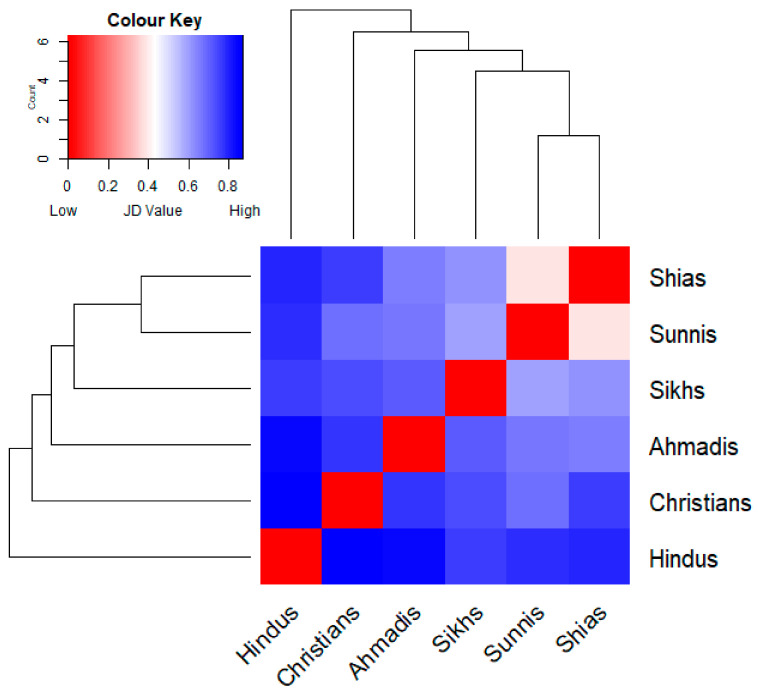

Figure 9 shows the comparison among the six groups in terms of specific food uses of the recorded wild food plants; the diagram shows a high diversity as well as a few specific cultural markers.

Figure 9.

Venn diagram showing the number of overlaps of the recorded wild food plant uses among the studied religious groups; the diagram shows also the food uses uniquely recorded within each group.

The similarity heat maps on the typology of wild plants food uses (Figure 10) demonstrates similar tendencies, outlining even greater differences between Christians and Ahmadis compared to Hindus, and also showing more divergences even among Sunnis and Shias. This suggests that there is a higher similarity in the used wild food plants than the way taxa are actually consumed in the study area; moreover, each considered group retains unique wild food plant utilizations.

Figure 10.

Hierarchical clustering tree coupled with heat map depicting Jaccard Dissimilarity Indices calculated by comparing the actual food utilizations of the recorded wild food plants among the six considered groups.

While our results show remarkable social and cultural exchanges between the different religious groups (sharing the same repertoire of plants), we can also see clear differences among the ways local food plants are actually used. This may to be linked to the different exposure the diverse religious groups have to traditional rural lifestyles and to nature. Nowadays, only Shias, Sunnis and Ahmadis have for example retained traditional livelihood practices (farming), while the local community members belonging to the three other faiths (Christians, Hindus, and Sikhs) are partially employed in city jobs, and some of them even practice as professional herbalists. The different relationships to farming that shape the differences in wild food plants-centered TEK among the groups may also be due to diverse levels of land access and land ownership.

While members of the different religions in the study area generally do not intermarry, they very regularly interact in urban settings and this, over centuries, may have contributed to a homogenization of TEK and cultural adaptation to the dominant groups.

The study participants confirmed that the use of wild plant species as daily food has significantly decreased, as well as the use of wild food plants on special occasions and religious festivities. This may be due to the fact that study participants perceive nowadays foraging (collecting wild food plants) as very time consuming, while cultivated plants are relatively easy to purchase in the immediate vicinity, and especially in bulk if and when required on special occasions. These trends may further lead to rapid TEK erosion in the near future, and further ethnobotanical works documenting local uses of wild food plants could be crucial for the food security and the preservation of the bio-cultural heritage of rural communities [93,94].

Food taboos restricting the consumption of some plants and fruits under certain conditions have been described from many regions of the world, involving followers of various religions including Hindus [95]. Similarly, in this study, some Hindus participants reported that the fruits of Ziziphus oxyphylla and Ziziphus jujuba were gathered only in mountain areas, hilly slopes and scrubland in time of need as famine foods only. Hence, the Hindus, but others possibly as well, follow the specific rules in what they consume, especially like when pregnant or menstruating. Food taboos might influence the uses of certain wild plants with regard to seasons or a consumer’s health condition, gender or age [95]. The participants pointed out a few other idiosyncratic food uses of wild plants within specific groups as well; these uses mostly included medicinal foods, i.e., food preparations considered consumed for counteracting specific diseases or health conditions, or ritual uses linked to specific cultural beliefs. For example, the gum of Acacia modesta and Acacia nilotica is added in “halwa” (a local sweet prepared by using clarified butter and wheat bran), and recommended to women after childbirth to avoid general weakness and back pains among the Muslim participants. Similarly, Sikhs conveyed that a limited dosage (about 250–300 mL) of a herbal drink made with Cannabis sativa can induce activeness; the informants claimed that their ancestors use the same preparation during battles in the 19th and 20th century. The herbal tea prepared by using fruits of Tribulus terrestris is drunk by Hindu women in order to improve lactation. Finally, Muslims add leaves of Ziziphus jujuba and Ziziphus numularia in boiling water, and use them for bathing dead persons, as they perceive that would delay their decomposition until burial. The rest of documented wild edible plant species as food in this study may applicable to all gender, religion and age groups equally, and no associated food taboo is mentioned by any participant.

3.3. Comparison with the Pakistani Food Ethnobotanical Literature

The comprehensive comparison with the Pakistani wild food ethnobotanical literature [49,50,51,52,70,71,72] of Pakistan showed that a remarkable number of species were documented as wild food plants, for the first time, in the study regions: Acacia modesta, Acacia nilotica, Agave americana, Boerhavia repens, Capparis decidua, Chenopodium murale, Chenopodium vulvaria, Coprinus comatus, Corchorus depressus, Corchorus tridens, Cucumis melo, Dysphania ambrosioides, Fagonia indica, Gisekia pharnaceoides, Indigofera hochstetteri, Lathyrus sativus, Lepidium apetalum, Mentha arvensis, Mentha pulegium, Olea europaea, Phoenix sylvestris, Pistia stratiotes, Prosopis cineraria, Prosopis juliflora, Rhynchosia minima, Salvadora oleoides, Salvadora persica, Senna italica, Senna occidentalis, Solanum incanum, Tephrosia purpurea, Tribulus terrestris, Trigonella anguina, Trigonella corniculata, and Withania coagulans.

Despite the fact that in our study three quarters of the wild food plants were reported also in other areas of northern Pakistan [50,52], pairwise Jaccard’s distance between our findings and those arising from field studies recently conducted in various regions of Pakistan shows little similarity and a very large diversification of wild food plant uses within the country (Figure 11). This may be explained by the very diverse geography and natural environments, as well as a remarkable cultural diversity, which ultimately and most importantly affect the diversity of food customs of the country.

Figure 11.

Pairwise Jaccard Dissimilarity Indices calculated by comparing the current study with other wild food ethnobotanical field works previously conducted in Pakistan.

Based on a comprehensive literature review, we found that some wild food plant species recorded in the current study have rarely been documented as food ingredients elsewhere in Pakistan and its neighboring countries. These include Aerva javanica, Agave americana, Amaranthus spinosus, Boerhavia repens, Caragana ambigua, Commelina benghalensis, Convolvulus arvensis, Corchorus depressus, Corchorus tridens, Gisekia pharnaceoides, Indigofera hochstetteri, Lathyrus aphaca, Lepidium apetalum, Mentha royleana, Opuntia dillenii, Oxalis corniculata, Physalis divaricata, Pistia stratiotes, Polygonum plebeium, Rhynchosia minima, Trigonella anguina, Trigonella corniculata, and Veronica anagallis-aquatica.

4. Conclusions

Our study reported seventy-seven plant taxa and one mushroom used as cultural foods among six different religions. The cross-religious comparison showed high overlap in the used taxa between Shias and Sunnis, who together used all listed taxa in the study region and contributed the most detailed information about specific, commonly used wild food plants. Comparison of the other four religious groups showed much less overlap between the groups and greater variation in the numbers of used plants. Urban Hindus and Christians used the least number of plants, followed by rural Sikhs and urban Ahmadis. A comparative analysis with the wild food plant literature of Pakistan showed a high diversification of wild plant uses in the study region, due to both environmental and cultural factors. This study also concluded that there is relatively higher homogeneity in use of plant species as food compared to method (preparations) of use of the same among the religious groups. Therefore, if one religious group prepares herbal drink of a plant species, the other might prefer to prepare jam of the same, depicting possession of unique recipes.

The inherited cultural knowledge of wild food plants of Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, and Ahmadis, in particular, faces the greatest challenges, as these groups have apparently undergone cultural adaptation to an urban, “modern” lifestyle. The present study may provide a foundation for the promotion of eco-tourism and for supporting sustainable development programs. Several of the recorded wild food plants are still sold in local markets (e.g., Capparis, Mentha, Olea, Phoenix, Rhynchosia, Salvadora, Salvia, Senna, Solanum, Trigonella, Vicia, and Ziziphus spp.) and this could represent the basis of wild food plant-centered local projects, aiming to revitalize TEK and generate small-scale economies providing some cash-income for rural communities.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to all the study participants who generously shared their traditional knowledge on wild food plant uses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.A., A.P., and M.M.; methodology, A.P. and M.S.A.; validation, K.H.B. and S.K.C.; formal analysis, A.M.K. and R.S.; investigation, M.M.; resources, M.M., R.S., M.A.A., and A.P.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M. and M.S.A.; writing—review and editing, A.M.K., R.W.B., A.P., and R.S.; supervision, M.S.A. and K.H.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has not been financially supported by any funding agency/organization.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Department of Botany, University of Gujrat, Pakistan (protocol code 2019-12A; date of approval Wednesday, 16 January 2019)

Informed Consent Statement

Prior informed consent was verbally obtained from all the study participants and Code of Ethics of the International Society of Ethnobiology (http://www.ethnobiology.net/what-we-do/core-programs/ise-ethics-program/code-of-ethics/, accessed on 6 March 2020) was strictly followed.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to avoid any inter-controversies among the studied religious groups.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Scherrer A.M., Motti R., Weckerle C.S. Traditional plant use in the areas of Monte Vesole and Ascea, Cilento national park (Campania, Southern Italy) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97:129–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pawera L., Khomsan A., Zuhud E.A., Hunter D., Ickowitz A., Polesny Z. Wild food plants and trends in their use: From knowledge and perceptions to drivers of change in West Sumatra, Indonesia. Food. 2020;9:1240. doi: 10.3390/foods9091240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newcity M. Protecting the traditional knowledge and cultural expressions of Russia’s numerically-small indigenous peoples: What has been done, What remains to be done. Tex. Wesleyan L. Rev. 2008;15:357. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1508497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zidny R., Sjöström J., Eilks I.A. Multi-perspective reflection on how indigenous knowledge and related ideas can improve science education for sustainability. Sci. Edu. 2020;29:145–185. doi: 10.1007/s11191-019-00100-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garibaldi A., Turner N. Cultural keystone species: Implications for ecological conservation and restoration. Eco. Soc. 2004;9:9. doi: 10.5751/ES-00669-090301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amjad M.S., Qaeem M.F., Ahmad I., Khan S.U., Chaudhari S.K., Malik N.Z., Shaheen H., Khan A.M. Descriptive study of plant resources in the context of the ethnomedicinal relevance of indigenous flora: A case study from Toli Peer National Park, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sõukand R., Pieroni A. Resilience in the mountains: Biocultural refugia of wild food in the Greater Caucasus range, Azerbaijan. Biodiv. Conser. 2019;28:3529–3545. doi: 10.1007/s10531-019-01835-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pieroni A., Sõukand R. Ethnic and religious affiliations affect traditional wild plant foraging in Central Azerbaijan. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2019;66:1495–1513. doi: 10.1007/s10722-019-00802-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pieroni A., Sõukand R., Amin H.I., Zahir H., Kukk T. Celebrating multi-religious co-existence in Central Kurdistan: The bio-culturally diverse traditional gathering of wild vegetables among Yazidis, Assyrians, and Muslim Kurds. Hum. Eco. 2018;46:217–227. doi: 10.1007/s10745-018-9978-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner N.J., Łuczaj Ł.J., Migliorini P., Pieroni A., Dreon A.L., Sacchetti L.E., Paoletti M.G. Edible and tended wild plants, traditional ecological knowledge and agroecology. Crit. Rev. Plant. Sci. 2011;30:198–225. doi: 10.1080/07352689.2011.554492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Łuczaj Ł., Szymański W.M. Wild vascular plants gathered for consumption in the Polish countryside: A review. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stryamets N., Elbakidze M., Ceuterick M., Angelstam P., Axelsson R. From economic survival to recreation: Contemporary uses of wild food and medicine in rural Sweden, Ukraine and NW Russia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015;11:53. doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0036-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cleveland M., Laroche M., Hallab R. Globalization, culture, religion, and values: Comparing consumption patterns of Lebanese, Muslims and Christians. J. Bus. Res. 2013;66:958–967. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.12.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mustafa B., Hajdari A., Pieroni A., Pulaj B., Koro X., Quave C.L. A cross-cultural comparison of folk plant uses among Albanians, Bosniaks, Gorani and Turks living in south Kosovo. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015;11:39. doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0023-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santoro F.R., Nascimento A.L., Soldati G.T., Júnior W.S., Albuquerque U.P. Evolutionary ethnobiology and cultural evolution: Opportunities for research and dialog. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018;14:1. doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0199-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbasi A.M., Khan M.A., Shah M.H., Shah M.M., Pervez A., Ahmad M. Ethnobotanical appraisal and cultural values of medicinally important wild edible vegetables of Lesser Himalayas-Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013;9:66. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pieroni A., Hovsepyan R., Manduzai A.K., Sõukand R. Wild food plants traditionally gathered in central Armenia: Archaic ingredients or future sustainable foods? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020;13:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00678-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalle R., Sõukand R., Pieroni A. Devil is in the details: Use of wild food plants in historical Võromaa and Setomaa, Present-day Estonia. Food. 2020;9:570. doi: 10.3390/foods9050570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellia G., Pieroni A. Isolated, but transnational: The glocal nature of Waldensian ethnobotany, Western Alps, NW Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015;11:37. doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0027-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dogan Y., Nedelcheva A. Wild plants from open markets on both sides of the Bulgarian-Turkish border. Ind. J. Trad. Know. 2015;14:351–358. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eyssartier C., Ladio A.H., Lozada M. Cultural transmission of traditional knowledge in two populations of north-western Patagonia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008;4:25. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghorbani A., Langenberger G., Sauerborn J. A comparison of the wild food plant use knowledge of ethnic minorities in Naban river watershed national nature reserve, Yunnan, SW China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang S., Quave C.L. A comparison of traditional food and health strategies among Taiwanese and Chinese immigrants in Atlanta, Georgia, USA. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013;9:61. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menendez-Baceta G., Aceituno-Mata L., Reyes-García V., Tardío J., Salpeteur M., Pardo-de-Santayana M. The importance of cultural factors in the distribution of medicinal plant knowledge: A case study in four Basque regions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015;161:116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pieroni A., Rexhepi B., Nedelcheva A., Hajdari A., Mustafa B., Kolosova V., Cianfaglione K., Quave C.L. One century later: The folk botanical knowledge of the last remaining Albanians of the upper Reka Valley, Mount Korab, Western Macedonia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013;9:1–19. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pardo-de-Santayana M., Tardío J., Blanco E., Carvalho A.M., Lastra J.J., San Miguel E., Morales R. Traditional knowledge of wild edible plants used in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal): A comparative study. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007;3:27. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pieroni A., Quave C.L. Traditional pharmacopoeias and medicines among Albanians and Italians in southern Italy: A comparison. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;101:258–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pieroni A., Giusti M.E., Quave C.L. Cross-cultural ethnobiology in the western Balkans: Medical ethnobotany and ethnozoology among Albanians and Serbs in the Pešter Plateau, Sandžak, South-Western Serbia. Hum. Eco. 2011;39:333. doi: 10.1007/s10745-011-9401-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pieroni A., Quave C.L. Perspectives on Sustainable Rural Development and Reconciliation. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2014. Ethnobotany and biocultural diversities in the Balkans. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bracher A., Sharma A., Starling-Windhof A., Hartl F.U., Hayer-Hartl M. Degradation of potent Rubisco inhibitor by selective sugar phosphatase. Nat. Plant. 2015;1:1–7. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2014.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rexhepi B., Mustafa B., Hajdari A., Rushidi-Rexhepi J., Quave C.L., Pieroni A. Traditional medicinal plant knowledge among Albanians, Macedonians and Gorani in the Sharr mountains (Republic of Macedonia) Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2013;60:2055–2080. doi: 10.1007/s10722-013-9974-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zamudio F., Kujawska M., I Hilgert N. Honey as medicinal and food resource. Comparison between Polish and multiethnic settlements of the Atlantic forest, Misiones, Argentina. Open Complement. Med. J. 2010;2:58–73. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agbobatinkpo P.B., Azokpota P., Akissoe N., Kayode P., Da Gbadji R., Hounhouigan D.J. Indigenous perception and characterization of Yanyanku and Ikpiru: Two functional additives for the fermentation of African locust bean. Ecol. Food. Nutr. 2011;50:101–114. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2011.552369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinkraus K.H. Classification of fermented foods: Worldwide review of household fermentation techniques. Food. Cont. 1997;8:311–317. doi: 10.1016/S0956-7135(97)00050-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gadaga T.H., Mutukumira A.N., Narvhus J.A., Feresu S.B. A review of traditional fermented foods and beverages of Zimbabwe. Int. J. Food. Microbio. 1999;53:1–11. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(99)00154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garabal J.I. Biodiversity and the survival of autochthonous fermented products. Int. Microbio. 2007;10:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Law S.V., Abu Bakar F., Mat Hashim D., Abdul Hamid A. Popular fermented foods and beverages in Southeast Asia. Int. Food. Res. J. 2011;18:475–484. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maroyi A. Diversity of use and local knowledge of wild and cultivated plants in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017;13:43. doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0173-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masarirambi M.T., Mhazo N., Dlamini A.M., Mutukumira A.N. Common indigenous fermented foods and beverages produced in Swaziland: A review. J. Food. Sci. Technol. 2009;46:505–508. [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGovern P.E., Zhang J., Tang J., Zhang Z., Hall G.R., Moreau R.A., Nuñez A., Butrym E.D., Richards M.P., Wang C.S., et al. Fermented beverages of pre-and proto-historic China. Proceed. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:17593–17598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407921102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henrich J., Henrich N. The evolution of cultural adaptations: Fijian food taboos protect against dangerous marine toxins. Proceed. Royal. Soc. B Biolog. Sci. 2010;277:3715–3724. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steinkraus K.H. Handbook of Indigenous Fermented Foods. 2nd ed. Marcel Dekker; New York, NY, USA: 1996. Introduction to indigenous fermented foods; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tamang J.P., Sarkar P.K., Hesseltine C.W. Traditional fermented foods and beverages of Darjeeling and Sikkim–A review. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 1988;44:375–385. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740440410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valadez-Blanco R., Bravo-Villa G., Santos-Sánchez N.F., Velasco-Almendarez S.I., Montville T.J. The artisanal production of pulque, a traditional beverage of the Mexican highlands. Probio. Antimicrobi. Prot. 2012;4:140–144. doi: 10.1007/s12602-012-9096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valdez L.M. Molle beer production in a Peruvian central highland valley. J. Anthropolog. Res. 2012;68:71–93. doi: 10.3998/jar.0521004.0068.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yaseen G., Ahmad M., Zafar M., Sultana S., Kayani S., Cetto A.A., Shaheen S. Traditional management of diabetes in Pakistan: Ethnobotanical investigation from traditional health practitioners. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015;174:91–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agnihotri R.K. Handbook of Education Systems in South Asia. Springer; Singapore: 2020. Linguistic Diversity and Marginality in South Asia; pp. 1–37. Global Education Systems. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mushtaq M.U., Gull S., Shad M.A., Akram J. Socio-demographic correlates of the health-seeking behaviors in two districts of Pakistan’s Punjab province. J. Pak. Med. Asso. 2011;61:1205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahmad K., Pieroni A. Folk knowledge of wild food plants among the tribal communities of Thakht-e-Sulaiman hills, north-west Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016;12:17. doi: 10.1186/s13002-016-0090-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aziz M.A., Abbasi A.M., Ullah Z., Pieroni A. Shared but threatened: The heritage of wild food plant gathering among different linguistic and religious groups in the Ishkoman and Yasin valleys, north Pakistan. Food. 2020;9:601. doi: 10.3390/foods9050601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aziz M.A., Ullah Z., Pieroni A. Wild food plant gathering among Kalasha, Yidgha, Nuristani and Khowar speakers in Chitral, NW Pakistan. Sustainability. 2020;12:9176. doi: 10.3390/su12219176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abbas W., Hussain W., Hussain W., Badshah L., Hussain K., Pieroni A. Traditional wild vegetables gathered by four religious groups in Kurram district, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, north-west Pakistan. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2020;67:1521–1536. doi: 10.1007/s10722-020-00926-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shah G.U., Bhatti M.N., Iftikhar M., Qureshi M.I., Zaman K. Implementation of technology acceptance model in e-learning environment in rural and urban areas of Pakistan. World. Appl. Sci. J. 2013;27:1495–1507. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Altaf M., Umair M., Abbasi A.R., Muhammad N., Abbasi A.M. Ethnomedicinal applications of animal species by the local communities of Punjab, Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018;14:55. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hamidov A., Helming K., Balla D. Impact of agricultural land use in central Asia: A review. Agron. Sust. Develop. 2016;36:6. doi: 10.1007/s13593-015-0337-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iqbal H., Sher Z., Khan Z.U. Medicinal plants from salt range Pind Dadan Khan, district Jhelum, Punjab, Pakistan. J. Med. Plant. Res. 2011;5:2157–2168. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Majeed M., Bhatti K.H., Amjad M.S., Abbasi A.M., Bussmann R.W., Nawaz F., Rashid A., Mehmood A., Mahmood M., Khan W.M., et al. Ethno-veterinary uses of Poaceae in Punjab, Pakistan. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0241705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mattalia G., Sõukand R., Corvo P., Pieroni A. Dissymmetry at the border: Wild food and medicinal ethnobotany of Slovenes and Friulians in NE Italy. Econ. Bot. 2020;10:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s12231-020-09488-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kujawska M., Łuczaj Ł. Wild edible plants used by the Polish community in Misiones, Argentina. Hum. Eco. 2015;43:855–869. doi: 10.1007/s10745-015-9790-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Termote C., Van Damme P., Djailo B.D.A. Eating from the wild: Turumbu, Mbole and Bali traditional knowledge on non-cultivated edible plants, District Tshopo, DRCongo. 2011;58:585–618. doi: 10.1007/s10722-010-9602-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ali S.I., Qaiser M., editors. Flora of Pakistan. University of Karachi; Karachi, Pakistan: 1993. No. 205–215. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nasir E., Ali S.I., editors. Flora of Pakistan. University of Karachi; Karachi, Pakistan: 1970. No. 1–190. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ali S.I., Nasir Y.J., editors. Flora of Pakistan. University of Karachi; Karachi, Pakistan: 1989. No. 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- 64.The Plant List (Ver. 1.1) [(accessed on 30 November 2019)]; Available online: http://www.theplantlist.org/

- 65.Index Fungorum. [(accessed on 19 April 2020)]; Available online: http://www.indexfungorum.org/Names/Names.asp.

- 66.Patzelt A., Al Hatmi S., Al Hinai A., Al Qassabi Z., Knees S.G. Studies in the flora of Arabia: Xxxiv. Sixty new records from the Sultanate of Oman. Edinburgh. J. Bot. 2020;77:413–437. doi: 10.1017/S0960428620000086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khan A.M., Qureshi R., Saqib Z. Multivariate analyses of the vegetation of the western Himalayan forests of Muzaffarabad district, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. Ecol. Indic. 2019;104:723–736. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.05.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Khan A.M., Qureshi R., Saqib Z., Munir M., Shaheen H., Habib T., Dar M.E.U.I., Fatimah H., Afza R., Hussain M.A. A first ever detailed ecological exploration of the western Himalayan forests of Sudhan Gali and Ganga summit, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019;17:15477–15505. doi: 10.15666/aeer/1706_1547715505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.González-Tejero M.R., Casares-Porcel M., Sánchez-Rojas C.P., Ramiro-Gutiérrez J.M., Molero-Mesa J., Pieroni A., Giusti M.E., Censorii E., De Pasquale C., Della A. Paraskeva-Hadijchambi, D. Medicinal plants in the Mediterranean area: Synthesis of the results of the project Rubia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008;116:341–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ijaz S., Perveen A., Ashraf S., Bibi A., Dogan Y. Indigenous wild plants and fungi traditionally used in folk medicine and functional food in district Neelum Azad Kashmir. Env. Devel. Sust. 2020;1:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00966-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abbasi A.M., Khan M.A., Khan N., Shah M.H. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinally important wild edible fruits species used by tribal communities of lesser Himalayas-Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013;148:528–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Khan M.P., Ahmad M., Zafar M., Sultana S., Ali M.I., Sun H. Ethnomedicinal uses of edible wild fruits (EWFs) in Swat valley, northern Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015;173:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Łuczaj Ł.J., Kujawska M. Botanists and their childhood memories: An underutilized expert source in ethnobotanical research. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2012;168:334–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2011.01205.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pieroni A., Zahir H., Amin H.I., Sõukand R. Where tulips and crocuses are popular food snacks: Kurdish traditional foraging reveals traces of mobile pastoralism in Southern Iraqi Kurdistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019;15:59. doi: 10.1186/s13002-019-0341-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mattalia G., Sõukand R., Corvo P., Pieroni A. Wild food thistle gathering and pastoralism: An inextricable link in the biocultural landscape of Barbagia, central Sardinia (Italy) Sustaintability. 2020;12:5105. doi: 10.3390/su12125105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fernández-Giménez M.E., Estaque F.F. Pyrenean pastoralists’ ecological knowledge: Documentation and application to natural resource management and adaptation. Hum. Eco. 2012;40:287–300. doi: 10.1007/s10745-012-9463-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ghimire S.K., Aumeeruddy-Thomas Y. Ethnobotanical classification and plant nomenclature system of high altitude agro-pastoralists in Dolpo, Nepal. Botanica Orientalis. J. Plant. Sci. 2009;6:56–68. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oteros-Rozas E., Ontillera-Sánchez R., Sanosa P., Gómez-Baggethun E., Reyes-García V., González J.A. Traditional ecological knowledge among transhumant pastoralists in Mediterranean Spain. Eco. Soc. 2013;18:1–19. doi: 10.5751/ES-05597-180333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dong S., Wen L., Liu S., Zhang X., Lassoie J.P., Yi S., Li X., Li J., Li Y. Vulnerability of worldwide pastoralism to global changes and interdisciplinary strategies for sustainable pastoralism. Eco. Soc. 2011;1:16. doi: 10.5751/ES-04093-160210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Menendez-Baceta G., Aceituno-Mata L., Tardío J., Reyes-García V., Pardo-de-Santayana M. Wild edible plants traditionally gathered in Gorbeialdea (Biscay, Basque Country) Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2012;59:1329–1347. doi: 10.1007/s10722-011-9760-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pawera L., Verner V., Termote C., Sodombekov I., Kandakov A., Karabaev N., Skalicky M., Polesny Z. Medical ethnobotany of herbal practitioners in the Turkestan range, southwestern Kyrgyzstan. Acta Soci. Botanico. Polon. 2016;85:1. doi: 10.5586/asbp.3483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sõukand R., Kalle R. Perceiving the biodiversity of food at chest-height: Use of the fleshy fruits of wild trees and shrubs in Saaremaa, Estonia. Hum. Eco. 2016;44:265–272. doi: 10.1007/s10745-016-9818-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Milner S.E., Brunton N.P., Jones P.W., O’Brien N.M., Collins S.G., Maguire A.R. Bioactivities of glycoalkaloids and their aglycones from Solanum species. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2011;59:3454–3484. doi: 10.1021/jf200439q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Carle R. Investigations on the content of steroidal alkaloids and sapogenins within Solanum sect Solanum (=sect. Morella) (Solanaceae) Plant. Syst. Evol. 1981;138:61–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00984609. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nordeide M.B., Hatløy A., Følling M., Lied E., Oshaug A. Nutrient composition and nutritional importance of green leaves and wild food resources in an agricultural district, Koutiala, in southern Mali. Int. J. Food. Sci. Nut. 1996;47:455–468. doi: 10.3109/09637489609031874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pimentel D., McNair M., Buck L., Pimentel M., Kamil J. The value of forests to world food security. Hum. Eco. 1997;25:91–120. doi: 10.1023/A:1021987920278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sundriyal M., Sundriyal D.C. Wild edible plants of the Sikkim Himalaya: Nutritive values of selected species. Eco. Bot. 2001;55:377. doi: 10.1007/BF02866561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Abbasi A.M., Khan M.A., Zafar M. Ethno-medicinal assessment of some selected wild edible fruits and vegetables of Lesser-Himalayas, Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2013;45:215–222. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Łuczaj Ł., Končić M.Z., Miličević T., Dolina K., Pandža M. Wild vegetable mixes sold in the markets of Dalmatia (southern Croatia) J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013;9:2. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Konsam S., Thongam B., Handique A.K. Assessment of wild leafy vegetables traditionally consumed by the ethnic communities of Manipur, northeast India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016;12:9. doi: 10.1186/s13002-016-0080-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ali-Shtayeh M.S., Jamous R.M., Al-Shafie J.H., Wafa’A. E., Kherfan F.A., Qarariah K.H., Isra’S K., Soos I.M., Musleh A.A., Isa B.A., et al. Traditional knowledge of wild edible plants used in Palestine (Northern West Bank): A comparative study. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008;4:13. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kalle R., Sõukand R. Current and remembered past uses of wild food plants in Saaremaa, Estonia: Changes in the context of unlearning debt. Eco. Bot. 2016;70:235–253. doi: 10.1007/s12231-016-9355-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Somnasang P., Moreno-Black G. Knowing, gathering and eating: Knowledge and attitudes about wild food in an Isan village in northeastern Thailand. J. Ethnobiol. 2000;20:197–216. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sansanelli S., Ferri M., Salinitro M., Tassoni A. Ethnobotanical survey of wild food plants traditionally collected and consumed in the middle Agri valley (Basilicata region, southern Italy) J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017;13:50. doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0177-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Meyer-Rochow V.B. Food taboos: Their origins and purposes. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009;5:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement