Abstract

Vitamin A (VA) deficiency is a serious public health problem, especially in preschool children who are at risk of increased mortality. In order to address this problem, the World Health Organization recommends periodic high-dose supplementation to children 6–59 months of age in areas of highest risk. Originally, supplementation was meant as a short-term solution until more sustainable interventions could be adopted. Currently, many countries are fortifying commercialized common staple and snack foods with retinyl palmitate. However, in some countries, overlapping programs may lead to excessive intakes. Our review uses case studies in the United States, Guatemala, Zambia, and South Africa to illustrate the potential for excessive intakes in some groups. For example, direct liver analysis from 27 U.S. adult cadavers revealed 33% prevalence of hypervitaminosis A (defined as ≥1 μmol/g liver). In 133 Zambian children, 59% were diagnosed with hypervitaminosis A using a retinol isotope dilution, and 16% had ≥5% total serum VA as retinyl esters, a measure of intoxication. In 40 South African children who frequently consumed liver, 72.5% had ≥5% total serum VA as retinyl esters. All four countries have mandatory fortified foods and a high percentage of supplement users or targeted supplementation to preschool children.

Keywords: excessive vitamin A intake, fortification, Guatemala, hypervitaminosis A, South Africa, supplementation, United States, Zambia

Introduction

In many countries, especially in low- to middle-income countries where the under-five mortality rate is high, multiple vitamin A (VA) interventions are in place or are being proposed to reduce mortality risk due to VA deficiency. This usually includes high-dose VA supplementation (VAS) to preschool children below 5 years of age1 and fortification of staple or snack foods with preformed VA.2 Interventions using mandatory and/or voluntary fortification of staple foods and condiments reach most target groups in a population. Furthermore, daily and special-use supplements (e.g., prenatal, infant drops, and meal replacers) are common in high-income countries, causing concern for oversupplementation in some users.3 The long-term impact of simultaneous implementation of VAS and fortification on VA status in the same target groups is currently unknown. Minimal human data exist on actual liver VA concentrations compared with serum biomarkers that are accessible and could be used in population surveys to monitor the impact of multiple overlapping interventions.

VAS is important for population groups who are at risk of VA deficiency.1 Periodic high-dose supplements were first suggested in 1964 to treat xerophthalmia, the most severe ramification of VA deficiency that can lead to total blindness.4 Originally, high-dose supplements were meant as a short-term solution until long-term interventions could be implemented.5 However, in some countries that have successfully implemented fortification of staple foods, supplementation is still occurring in children under 5 years of age and in postpartum women. Examples of coexisting programs are detailed in the case studies below.

Fortification of commercialized common foods dates back almost a century. In 1925, VA was added to vegetable-derived margarine to make it more nutritionally equivalent to animal-derived butter.6 In the 1940s, this became mandatory by some governments. In order to be a good candidate for fortification, the food needs to be widely consumed among the target groups and manufactured in a manageable number of facilities for appropriate monitoring.7 Issues associated with VA fortification include fortificant stability and quality control.7,8 Although it is often thought that fortification reaches more people in urban settings, rural areas in some countries with good infrastructure are also recipients, thus reaching all sectors of the population.9

Among the many countries with multiple VA interventions in place, we will use case studies from the United States as a high-income country, Guatemala and Zambia as the lower-middle-income countries, and South Africa as an upper-middle-income country in this review.10 All of these countries have overlapping nutrition programs that may include mandatory and voluntary fortification programs and high use of either daily supplements by the population or periodic supplements to targeted vulnerable groups. In each of these countries, either biological or survey data indicate that some groups are receiving too much VA. The purpose of our review is to inform the readers, including nutritional scientists, dietitians, policy makers, and program support staff, of the risk of hypervitaminosis A due to overlapping programs and the importance of evaluating these programs to determine where changes may need to be made in the delivery systems or target areas.

United States of America

Intake data

Throughout our review, the Institute of Medicine definitions for retinol activity equivalents (RAEs) will be used, which estimate 1 μg preformed retinol, 12 μg all-trans-β-carotene, and 24 μg α-carotene or β-cryptoxanthin, as being equivalent to 1 μg RAE.11

In the United States, the 2013–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found that the mean daily intake for VA was about 600 μg RAE for children and 640 μg RAE for adults.12 These estimates do not include VA from supplements and prescribed medicines. Males tended to have higher intakes than females in all age groups. The child estimate is well above the Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for children below 9 years of age (300–400 μg RAE).11 The RDA is meant to ensure that 97–98% of the U.S. population requirements are met. The amount for adults in NHANES is above the estimated average requirement (EAR) of 500 and 625 μg RAE but under the RDAs of 700 and 900 μg RAE for females and males, respectively. Most of the estimated RAEs are from preformed retinyl esters (REs) (60–80%). In the U.S. NHANES 2009–2012, the usual intake of preformed VA exceeded the tolerable upper intake level (UL) for an estimated 21% of infants from 6 to 11 months and 16% of toddlers 12–23 months of age.13 The UL for this age group is 600 μg retinol equivalents. The UL for VA is always in preformed retinol equivalents because dietary intake from provitamin A carotenoids is presumed to be safe.11

A cross-sectional study in young U.S. women evaluated long-term VA intake and determined total body VA stores (141.5–3116 μmol) using retinol isotope dilution (RID) methods.14 RID estimates total body stores of VA by evaluating the dilution of a dose of VA labeled with either 13C or 2H by measuring the isotopic enrichment in the accessible serum retinol pool. In these young adult women, VA intake exceeded the RDA of 700 μg RAE, and intake was correlated with estimated total liver VA reserves.

Fortified foods: mandatory and voluntary

Fortification of foods in the United States is mostly voluntary except for some foods that have a standard of identity.15 For VA, only two foods are subject to mandatory VA fortification, that is, margarine and skimmed milks. VA has been added to milk since the 1940s. In 1978, this practice became mandatory because skim and lower fat milks were widely consumed.16 The process of skimming milk removes the naturally occurring REs in the lipid cream fraction. Even though the U.S. population continues to increase, fluid milk consumption has decrease substantially in the past decade (Fig. 1),17 which may affect VA intakes.

Figure 1.

Fluid milk sales in the United States have fallen in the past decade. Considering that low-fat and skim milks are fortified, we hypothesize that this may affect vitamin A intakes, particularly among low-income groups who do not receive free milk through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Low-income pregnant U.S. women qualifying for such a program had 9% prevalence of vitamin A deficiency.20

In addition, other foods are voluntarily fortified with VA. Breakfast cereals often contain 10–15% of the daily value (DV) and snack and meal replacement bars may contain upward of 100%. It must be noted that nutrition labeling in the United States is based on DVs and not RDAs. Up until 2016, a huge discrepancy existed between the DV and the RDA for VA. The DV, which is used on Supplement and Nutrition Facts’ panels, was based on the 1960s RDA value of 1500 μg retinol equivalents. However, on July 26, 2016, the final rule was changed, and by July 2018 and 2019 for larger and smaller food manufacturers, respectively, the labels must be updated to the current RDA for adult males as 100% of the DV, that is, 900 μg RAE.18

Supplement usage in the United States is very common, with an estimated 71% of adults consuming dietary supplements of all kinds and 75% of those individuals taking a mulitvitamin.19 Supplements are usually preformed retinyl acetate or palmitate, but some supplements are now formulated with β-carotene.

Data on vitamin A status

Although it is generally thought that the VA status of the United States is adequate, pockets of subclinical deficiency have been reported. For example, a 9% prevalence of deficient liver VA stores was qualitatively determined by the modified relative dose response (MRDR) test in low-income pregnant women who were part of public health programs, such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.20 In comparison, 17% of Indonesian pregnant women had VA-deficient MRDR values reflecting low liver stores.21 The MRDR test relies on the accumulation of retinol-binding protein (RBP), the carrier protein of plasma retinol, when liver VA stores become deficient (i.e., <0.1 μmol/g liver) and the rapid release of an analog of VA (i.e., vitamin A2) after dosage.22 The prevalence of hypervitaminosis A is largely unknown in the United States. In part, this is due to lack of appropriate biomarkers to use at the population level. While serum retinol concentrations have utility in diagnosing frank VA deficiency,22 serum retinol concentrations are not useful for diagnosing hypervitaminosis A because of the homeostatic mechanisms that keep plasma retinol under control.

Previous research has supported using circulating serum REs as a percentage of total serum VA as a measure of VA intoxication. The first research that suggested this biomarker was in three subjects taking long-term daily high-dose VA supplements (25,000–400,000 IU/day)23 and thus they likely had toxic amounts of VA in the liver, although this was not measured. The values for circulating REs reported were 41–67% of total serum VA as REs.23 A cutoff of >10% of total serum VA as REs was proposed from a study based on the 95% percentile at 13% for elderly subjects and 11% for young adults, in which serum REs were elevated with supplement use.24 A cutoff of 5% of total serum VA as REs was suggested to diagnose hypervitaminosis A in Zambian children when compared with the RID test.25 Having elevated circulating serum REs beyond the postprandial period is not ideal and results in adverse effects in the body,23 including bone abnormalities.26 In the U.S. cadavers (n = 27; age 49–101 years), total liver VA reserves were compared with percent of total serum VA as REs to evaluate hypervitaminosis A using autopsy samples.27 Serum RE concentrations were directly correlated with total liver VA reserves (r = 0.497).27 Although nine subjects (33%) had hypervitaminosis A (≥1 μmol/g liver; Fig. 2), none of them had >10% of total serum VA as REs. Liver histology corroborated toxic VA status in three individuals, with total liver VA reserves ~3 μmol/g. It is interesting to note that the two individuals with liver retinol concentrations >3 μmol/g had >7.5% of total serum VA as REs.27 When serum retinol concentrations from subjects who had hypervitaminosis A (1.17 ± 0.21 μmol/L; n = 9) were compared with those subjects who did not (1.13 ± 0.21 μmol/L; n = 18), they did not differ. Furthermore, only 41% had optimal liver VA reserves between 0.1 and 0.7 μmol VA/g liver (Fig. 2). This study further evaluated circulating serum REs as a marker of toxic VA status against total liver VA reserves (“gold standard”), but 10% total serum VA as REs as a cutoff needs further validation. To date, among currently available VA biomarkers, only the RID test is able to diagnose hypervitaminosis A before toxicity occurs.22

Figure 2.

The prevalence of vitamin A deficiency (<0.1 μmol/g liver) and hypervitaminosis A (≥1.0 μmol/g liver) in U.S. adult cadavers (n = 27, aged 49–101 years) who were diagnosed using liver autopsy samples.27

Guatemala

Vitamin A intake

The apparent intake (or household availability) of RAE in the Latin American and Caribbean region increased from 550 μg RAE in 1960 to 700 μg RAE in 1990, with animal sources accounting for 40% in Central America.28 In addition to fortified sugar, the 2006 Living Standards Measurement Survey of Guatemala demonstrated that approximately 80% of dietary VA comes from plants, comprising mostly yellow maize and other cereals. When fortified sugar is added to the other dietary sources, the risk of insufficient VA intake among women in all socioeconomic strata is virtually eliminated.29 Moreover, assuming a 50% loss of the mandated VA level (15 μg/g), the additional VA from median consumption of sugar (112 g) per female adult consumption equivalent unit per day has been estimated to result in an additional daily intake of 839 μg VA, the equivalent of 235% of the EAR for a woman 15–50 years of age. On the other hand, approximately 15% of children 2–4 years of age living under extreme poverty conditions consume insufficient amounts of VA and are therefore at risk of VA deficiency.30

Vitamin A status surveys

Except for small subsamples, surveillance and impact assessment ofVA interventions in Guatemala have always used serum/plasma retinol concentrations as an indicator of VA status. In 1972, 22% of children 0–4 years of age had serum retinol concentrations >0.7 μmol/L.31 Two years after the national sugar fortification’s first phase (1975–1977), prevalence of serum retinol concentrations <0.7 μmol/L dropped to 9%, demonstrating the impact of sugar fortification (with 15 μg/g at the factory level). In 1987, just before the program’s reestablishment, 26% of children from a subnational sample of children had serum retinol <0.7 μmol/L, a higher prevalence than 12 years earlier. The first truly national micronutrient status survey carried out in 1995 confirmed the latter result: 16% of children in the country had low concentrations of serum retinol. In the same survey, it was found that 26% of children who did not consume fortified sugar still had undesirable low concentrations of serum retinol.32 Subsequently, concerned by the relatively low impact of the fortified sugar on serum retinol concentrations, the National Sugar Producers Association (www.asasgua.com) improved the fortification process in all of its mills to minimize losses of the retinyl palmitate during drying and storage, among other factors. The most recent national micronutrient status survey from 2009 to 2010 demonstrated a decline in the prevalence of serum retinol concentrations <0.7 μmol/L in children 6–59 months (0.3%) and infants 6–11 months (1%).

The dramatic decrease in VA deficiency between 1995 and 2010 in children aged 12–59 months clearly shows a trend toward elimination of the deficiency (Table 1).30 More recent smaller studies in the 166 districts considered as extremely poor have also documented this important achievement in the effective control of VA deficiency. Nonetheless, 5–11% of children younger than 24 months still had low concentrations of RBP (a surrogate of serum retinol), with higher prevalence in children aged 6–11 months.33,34 On the basis of the success of VA deficiency control, a revision has been proposed that would harmonize the nutrition interventions that contribute to VA intake, including lowering sugar fortification levels and the exclusion of children older than 2 years of age from high-dose VAS.35 Only the latter modification to the national supplementation program has been implemented by the Ministry of Health to date.

Table 1.

Historical summary of population vitamin A status in Guatemala

| Biomarker group | National Micronutrient Survey 1995 SR |

National Micronutrient Survey 2009–2010 SR |

Western Highland 2011 RBP |

Impoverished districts 2013 RBP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women 15–49 years | ||||

| Pregnant | 39.1 | — | — | 0 |

| Not pregnant | 34.9 | — | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Children 6–59 months | ||||

| Total | 15.8 | 0.3 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| Urban | 15.6 | 0.6 | — | 3.8 |

| Rural | 17.1 | 0.2 | — | 3.3 |

| Indigenous | — | — | — | 3.5 |

| Not indigenous | — | — | — | 3.3 |

| Age (months) | ||||

| 6–11 | — | 1.0 | 11.1 | 6.0 |

| 12–23 | 19.9 | 0.6 | 3.7 | 5.3 |

| 24–35 | 17.7 | 0.2 | 3.6 | 4.2 |

| 36–47 | 13.1 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 2.4 |

| 48–59 | 11.9 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.5 |

Note: Percent subjects with serum retinol (SR) or retinol-binding protein (RBP) as a surrogate <0.7 μmol/L.30

Fortified foods: mandatory and voluntary

Sugar fortification was initiated as a mandatory national program in 1975, but 2 years later it was halted.28 During its initial short phase, the program demonstrated that dietary and biochemical indicators of VA status (i.e., serum, milk, and liver concentrations) improved swiftly and dramatically.36 The program was relaunched in 1988 and current minimum requirements are 5 μg VA/g sugar with a target level of 15 μg/g. Most households (80–93%) had sugar VA concentrations above the mandated minimum level of fortification when tested.35 On the basis of mean sugar intakes, children would consume more than the EAR, but most children’s consumption would be safe, that is, under the UL. Nonetheless, because of safety concerns that some children may be consuming more than the UL, Guatemala may lower the target fortification level to 7 μg/g sugar.35 The government recommends that no other foods should be fortified except sugar.35 Recommendations for improving Guatemala’s food fortification program have been made based on economic considerations.29

Until 2010, serum retinol concentrations were used as the main indicator of the effectiveness of the program. As noted above, RBP has been adopted as a surrogate measure in the latest surveys focusing on populations living under extreme poverty. In addition to sugar, other popular food items are fortified with retinol voluntarily (e.g., margarine, processed milk, INCAPARINA™), and at least six composite flour, vegetable oil, and ready-to-eat products for infants and young children that are sold commercially or through specific social projects could provide 13–90% of the RDA per recommended daily ration.30 Multiple micronutrient powders containing retinyl palmitate are also provided to children 6–59 months of age. The impact on population VA status and the potential contribution to excessive intakes of VA attributable to these other sources of the nutrient have not been evaluated. In the 2011 survey conducted by the Ministry of Health, no child had a serum retinol concentration <0.7 μmol/L and only 5% of women had values <1.05 μmol/L.35

Other biological data

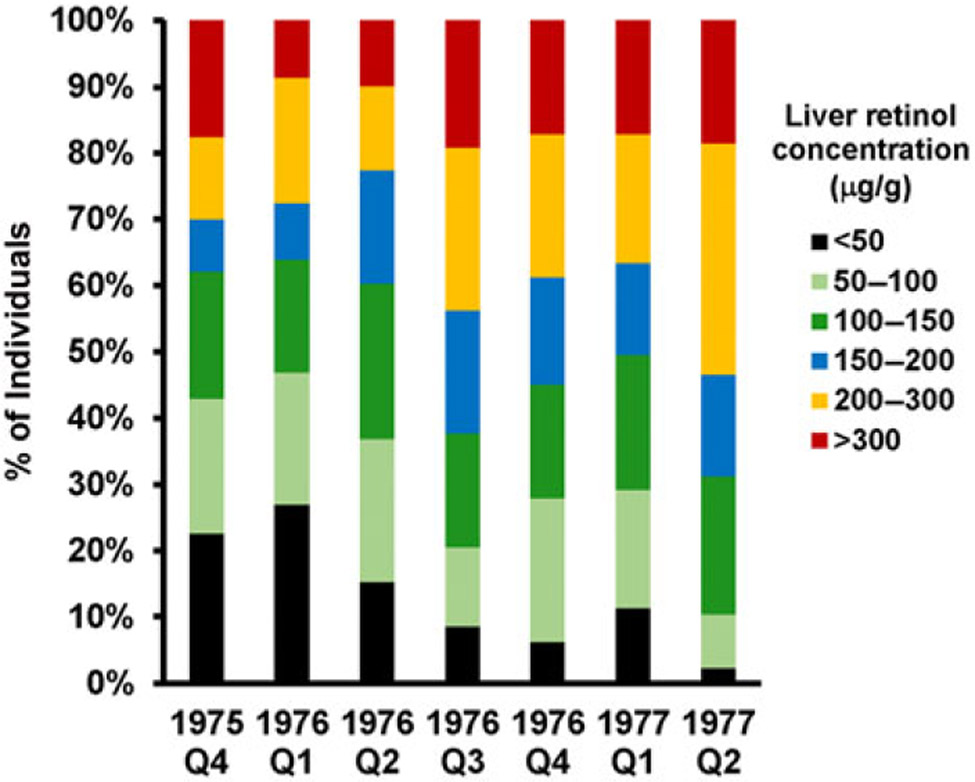

Between 1975 and 1977, the Instituto de Nutrición de Centro América y Panama carried out a national baseline survey followed by serial surveys during implementation of the sugar fortification program. Breast milk from women and blood from children aged 1–5 years were obtained for retinol analysis. The subjects were from 12 rural communities with populations between 1000 and 2000 inhabitants.36 Additionally, liver samples were taken from people (n = 770) who had died from traumatic (non-metabolic) causes during this period at autopsy by the General Hospital of Guatemala City (a third-level referral hospital), and analyzed for retinol concentrations. The data revealed that low liver retinol concentrations (defined as <0.175 μmol/g liver (50 μg/g)) declined rapidly and plateaued by the end of 1976 (Fig. 3). The percentage of liver samples with intermediate through high retinol concentrations (0.5–1 μmol/g) increased and plateaued at the same time. Hypervitaminotic concentrations (≥1 μmol/g) increased slowly to 5% during the same period. The percentage of breast milk samples < 1 μmol retinol/L from lactating women who were 0–2, 3–4, and 5–6 months postpartum declined significantly (P < 0.05) from 24% to 12%, from 41% to 18%, and from 63% to 23%, respectively.

Figure 3.

Stratification of liver vitamin A concentrations (in μg retinol/g liver in the original paper) in a survey of Guatemalan liver samples collected during autopsy of children and adults from 1975 to 1977.36 During this timeframe, the prevalence of low values (<50 μg retinol/g liver) decreased (black), while hypervitaminotic values (≥ 300 μg retinol/g (red)) increased slowly. The areas in light and dark green represent optimal vitamin A status (50–150 μg retinol/g). The current values recommended to be used are <0.1 μmol/g liver for vitamin A deficiency, which is equivalent to 29 μg retinol/g and ≥1.0 μmol/g liver for hypervitaminosis A, which is equivalent to 290 μg retinol/g.22

High-dose vitamin A supplementation

Since its inception in the early 2000s, high-dose VAS has been implemented consistently with varying and typically low coverage rates for children 6–59 months of age. The highest coverage rate over the past 11 years was 49% in 2006, and the lowest was 13% in 2013.37 Higher coverage has always been achieved among children under 2 years of age during their basic immunization schedule. On the basis of VA status survey results and successful sugar fortification, rather than the dismal VAS coverage figures, the Ministry of Health changed the inclusion criteria in 2016 and now supplements only children 6–24 months of age.

Zambia

Background

Zambia has multiple interventions in place to address VA deficiency. High-dose VAS is administered to children <5 years every 6 months with high coverage rates38 (Table 2) and to postpartum women within 8 weeks of delivery. The country has mandated sugar fortification with retinyl palmitate for all human consumption at the household level39,40 and has scaled-up the release of biofortified orange maize and orange-fleshed sweet potato.41 Furthermore, the consumption of varied foods rich in VA, such as red palm oil, is being promoted through the Ministry of Agriculture. This is in addition to having diets high in vegetable-sourced provitamin A carotenoids in some cohorts, which have been quantified with dietary recalls in children.42 In one area, children who were 5–7 years old had an alarming prevalence of 59% hypervitaminosis A (defined as ≥1 μmol/g liver) measured by the RID test,43 universally had high serum carotenoid concentrations,25 and many of them experienced hypercarotenodermia (orange pigmentation of the skin particularly noticeable in the palms and face) during mango season.44 Hypercarotenodermia likely occurred because of downregulation of the bioconversion of provitamin A carotenoids to retinol due to the high liver reserves of VA determined the year before.43,44 These children had 2% prevalence of >10% total serum VA as REs and 16% prevalence with ≥5% total serum VA as REs.25 Disrupted bone balance was associated with preformed VA exposure (unpublished observations).

Table 2.

An example of the high coverage of high-dose vitamin A supplementation in Zambian children 6–59 months old in 2016 during one of the Child Health Weeks

| Target group | Coverage percenta | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in months |

Age in months |

Age in months |

||||

| 6–11 | 12–59 | 6–11 | 12–59 | 6–11 | 12–59 | |

| Region | ||||||

| Central | 30,581 | 244,645 | 37,759 | 258,631 | 123 | 106 |

| Copperbelt | 47,244 | 377,953 | 48,178 | 341,200 | 102 | 90 |

| Eastern | 37,317 | 298,536 | 43,534 | 320,691 | 117 | 107 |

| Luapula | 22,482 | 179,859 | 26,897 | 186,934 | 120 | 104 |

| Lusaka | 55,461 | 443,688 | 73,186 | 402,511 | 132 | 91 |

| Muchinga | 17,654 | 141,229 | 22,129 | 154,381 | 125 | 109 |

| North Western | 16,676 | 133,411 | 20,761 | 113,263 | 124 | 85 |

| Northern | 26,089 | 208,710 | 30,969 | 205,232 | 119 | 98 |

| Southern | 33,856 | 270,844 | 49,073 | 312,590 | 145 | 115 |

| Western | 20,222 | 161,778 | 22,580 | 158,942 | 112 | 98 |

| National | 307,582 | 2,460,653 | 375,066 | 2,454,375 | 122 | 100 |

High coverage rates are common in Zambia, where children have opportunities to receive supplements during the Child Health Weeks and at the local clinics.

Intake data

Recently, sugar had a median VA concentration of 8.8 μg/g (range: 0.5–55) in Zambia,42 and daily sugar intake by children was 9–15 g/day,42,45 resulting in intakes of 77–132 μg preformed retinol/day.43 This would mean that intake from sugar alone is about 50% of the EAR for children (i.e., 210–275 μg RAE dependent on age).11 Furthermore, dietary intakes were predominantly adequate in VA among preschool children in rural Zambia due in part to high intakes of leafy green vegetables.42

Fortified foods: mandatory and voluntary

The most commonly consumed fortified food in Zambia is sugar. The government mandates that sugar be fortified with retinyl palmitate at 10 μg/g. Other foods that are fortified with VA and some B vitamins and minerals include maize meal and wheat flour with a recommendation of 1.7 μg RE/g (Statutory Instrument No. 90 2001). The fortification strategy in Zambia is led by the Ministry of Health with assistance from the National Food and Nutrition Commission, the National Institute for Scientific and Industrial Research, the University of Zambia, and Lusaka City Council. Several nonprofit organizations also provide input, including the World Food Program, CARE International, and the United Nations International Children’s Fund.

High-dose vitamin A supplementation

The policy on VAS in Zambia is to provide VA supplements to all children age 6–59 months delivered through Child Health Weeks, which is in keeping with current World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations.1 It is also Zambian policy to provide VA supplements to women of reproductive age within 8 weeks of delivery. This is despite guidance by WHO that there is no benefit in relationship to prevention of childhood morbidity and mortality by administering VA to mothers.46 The coverage of VAS among infants and children is high in Zambia. For example, the available findings from the Child Health Week in December 2016 showed that 122% and 100% coverages were achieved in the 6–11 months and 12–59 months age groups, respectively (Table 2). High coverage is also likely in women of reproductive age who receive their supplement within 8 weeks postpartum because they usually take their children to these public health programs and receive their supplement at the same time. Iron supplements are also common in pregnant women and usage is associated with increasing education and wealth.47

Vitamin A status surveys

A number of VA status surveys have been undertaken in Zambia. In addition to measuring status of children, the 1997 countrywide survey was the first to determine the VA status among women of reproductive age, in which the prevalence of low serum retinol concentrations (i.e., <0.7 μmol/L) was 21.5%. Furthermore, night blindness rates were 11.6% for women and 6.2% for children. This was followed by the 2003 VA impact survey. Both surveys determined serum retinol concentrations <0.7 μmol/L among children, which decreased from 66% in 1997 to 54% in 2003.48 Other studies have measured VA biomarkers in localized project sites. The 2009 survey used serum retinol concentrations and the MRDR test in two locations.42 The 2010 randomized controlled trial with biofortified maize also used serum retinol and the MRDR test;49 the 2012 randomized controlled trial with biofortified orange maize used serum retinol and the RID test.43 These data collectively show an increasing serum retinol concentration with time, an improvement in MRDR values in preschool children (3–5 years old), and high liver stores in older preschool children (5–7 years old). Another randomized controlled trial among preschool children used serum retinol and β-carotene concentrations, and only showed an improvement in β-carotene concentrations in children being fed biofortified maize, which likely represents adequate liver VA reserves.50

Biological data: direct or indirect liver reserves

The recent findings showing hypervitaminotic liver stores of VA among older preschool children are cause for concern. These results were based on highly sensitive methods that detect VA status over a wide range of liver stores. The combined evidence of hypervitaminosis A determined by RID, hypercarotenemia, elevated REs, saturated RBP, and hypercarotenodermia corroborates excessive stores in this rural area in Zambia.25,43,44

The use of multiple VA interventions calls for coordinated efforts in the implementation and monitoring for appropriate adjustment of the nutrition policy and programming to ensure prevention of excessive intakes of VA among subgroups of the population.

South Africa

Background

Over the past 25 years, three national surveys were conducted in South Africa, which provided information on the VA status of South African preschool children. The first survey in 1994 showed the prevalence of serum retinol concentrations <0.7 μmol/L in 6- to 71-month-old children to be 33.3% (n = 4283).51 The second survey conducted in 2005 showed 64.6% prevalence of low serum retinol,52 while the most recent survey in 2012 showed a prevalence of 43.6%.53 In the latter survey, serum retinol concentration was obtained as a secondary objective of the larger South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, and the sample size was rather small (n = 436) and could not be disaggregated at the provincial level.

Fortification and high-dose vitamin A supplementation

South Africa has two national programs that supply additional VA to the child’s diet. The National Food Fortification program, introduced in 2003, requires that wheat flour and maize meal be fortified with various micronutrients, including preformed VA.54 Maize meal and bread have been monitored for micronutrient content finding either inadequate or variable amounts of VA.55,56 The National Vitamin A Supplementation Program was introduced in 2002 and targets 6- to 59-month-old children at public health facilities to receive a high-dose VA supplement (200,000 IU) every 6 months as recommended by WHO.1,57 The latter policy is implemented at the provincial level, and uses routine health service delivery opportunities to achieve coverage. The national coverage in 2012–2013 was shown to be 43%.58

South Africa is a diverse country, not only geographically, but also culturally and socioeconomically. This is reflected in the eating habits of its population, and VA status thus also varies from province to province. For the purposes of our review, we will focus on a particular district within the Northern Cape province of South Africa (Hantam district) where sheep farming is a main agricultural activity and sheep liver is an available and affordable source of meat, and commonly consumed by the poor.59 Liver is an exceptionally rich source of preformed VA; thus, in addition to exposure to the two national programs, children in this area might be at risk of excessive VA intake.

Recently analyzed VA content of 14 sheep livers randomly purchased in this area ranged from 63 through 152 μg retinol equivalents (μg RE)/g (mean = 110 μg RE/g), and tended to be higher in the older animals (manuscript submitted). On the basis of these values, only 2–3 g of liver per day (or approximately one 70-g portion per month) would be enough VA to meet the daily EAR of the preschool child.11

Vitamin A status studies in the Hantam district of the Northern Cape province

A study in preschool children from the Hantam district showed that only 5.8% of the children (4.9% when children with elevated CRP are excluded) had serum retinol concentrations <0.7 μmol/L.59 This is in sharp contrast to the two most recent national surveys in 2005 and 2012, showing low serum retinol prevalence rates of 64.6% and 43.6%, respectively.52,53 A dietary assessment quantifying liver intake in the same area showed that liver alone supplied enough VA to meet the EAR, and that the UL was exceeded in 15% of these children.60

A follow-up cross-sectional study assessed serum retinol concentrations in 145 preschool children from the same community 3–4 weeks after a national VAS campaign (Fig. 4). From these children, serum REs were determined in a purposefully selected subgroup of 40 children (Liver-VAS subgroup) who received a high-dose VA supplement during this campaign and ate liver more than twice a month (Fig. 4). The main characteristics and VA status of the children taking part in this study are shown in Table 3. Mean serum retinol concentrations in the cross-sectional and Liver-VAS groups were similar; that is, less than 5% of the children in both groups had serum retinol <0.7 μmol/L, and none had a value >1.9 μmol/L. The mean frequency of liver intake in the Liver-VAS subgroup was five times per month, ranging from 3 to 8 occurrences. Assuming an average portion size of 65 g,60 this would translate to a mean VA intake of 1280 μg RE per day, which is 4.6 times the EAR for children 4–8 years, and exceeds the UL for this age group by 40%. The mean percent of total serum VA as REs in this group was 7.84 ± 4.20, while 35% and 20% of the children had elevated REs, that is, >7.5% and >10% total serum VA as RE, respectively.

Figure 4.

A cross-sectional study was performed in South African preschool children to evaluate serum retinol concentrations 3–4 weeks after a vitamin A supplementation campaign. Circulating serum retinyl esters as a percent of total serum vitamin A were determined in a subset of the children who met inclusion criteria of combined high liver consumption and having received a high-dose vitamin A supplement during the campaign.

Table 3.

Characteristics and vitamin A biomarkers in South African children who were part of a cross-sectional community study that assessed liver intake and serum retinol concentrations

| Cross-sectional community study (n = 145) |

Liver-VA supplement subgroupa (n = 40) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of childrenb | ||

| Age (years) | 3.74 ± 1.22 | 3.40 ± 1.01 |

| Gender (% boys/% girls) | 44.1/55.9 | 45.0/55.0 |

| Height-for-age Z-score | −1.73 ± 1.15 | −1.23 ± 1.17 |

| Weight-for-age Z-score | −1.18 ± 1.20 | −0.82 ± 1.24 |

| BMI-for-age Z-score | −0.09 ± 1.10 | −0.04 ± 1.13 |

| Liver intake and VA supplement | ||

| Children who received VA supplement during recent campaign (%) | 72.4 | 100 |

| Frequency of liver intake (times per month) | 2.8 ± 2.5 (range: 0–8) | 5.1 ± 2.2 (range: 3–8) |

| Vitamin A status | ||

| Serum retinol (μmol/L) | 1.07 ± 0.25 (range: 0.32–1.77) | 1.12 ± 0.27 (range: 0.62–1.77) |

| Serum retinol < 0.7 μmol/L (%) | 4.8 | 2.5 |

| Percent total serum VA as retinyl esters (mean) | — | 7.84 ± 4.20 |

| Children with >10% total serum VA as retinyl esters (%) | — | 20% |

| Children with >7.5% total serum VA as retinyl esters (%) | — | 35% |

| Children with ≥5% total serum VA as retinyl esters (%) | — | 72.5% |

Serum retinyl esters were measured in a subgroup of children with high monthly intakes of liver (>2 times/month) and who received a VA supplement during the national campaign 3–4 weeks before.

Values are mean ± SD or % where indicated.

This mean percent of total serum VA as REs found in this study is at the level of the U.S. adult cadavers shown to have abnormal liver histology (>7.5%).27 It is also much higher than the mean in the Zambian children’s cohort (2.9% ± 2.4%) where 59% were diagnosed with hypervitaminosis A, according to the RID test.25,43 Only 27.5% had values <5%, a value currently proposed as being normal in children who are fasting.25 The fact that there was no difference in serum retinol between the two groups, and none had values >1.9 μmol/L confirms that hypervitaminosis A cannot be detected by using serum retinol concentrations.61

Biological data: direct or indirect liver reserves

As part of a multicountry study in Africa funded in part by the International Atomic Energy Agency, total liver VA reserves in preschool children from this particular South African community have been evaluated with the RID test. Results revealed a high prevalence of hypervitaminosis A and a positive relationship between total liver VA reserves and liver intake, as well as the number of high-dose VA supplements received during their lifetime (manuscript submitted).

Discussion and conclusions

Fortified products, both mandatory and voluntary, are widely available in low-income through high-income countries.2 Furthermore, the use of high-dose supplements in children and daily supplements among individuals is common. Although excessive VA intakes were originally thought to be a problem in high-income countries and linked to adverse bone health,26,62 overlapping successful VA programs in low- and middle-income countries now require evaluation and monitoring to mitigate the risk of hypervitaminosis A.

While the purpose of our review is not to dispute the need for supplemental VA in some circumstances, countries need to evaluate and perhaps better target areas of greatest need. VA supplements have been one of the most successful interventions in the prevention of childhood mortality, ranking among common immunizations, oral rehydration therapy, and malaria prevention through the use of bed nets.63 For example, with the widespread use of fortified sugar in Zambia and maize and wheat flours in South Africa, it may be time to scale back high-dose VAS from under 5 years to include only children <3 years of age. As mentioned above, Guatemala has scaled back VAS to children <2 years of age since 2016. The delivery of each capsule represents a cost;64 therefore, targeting the children most vulnerable to VA deficiency is a cost saving that can be used for other public health initiatives. Fortified foods that are centrally processed reach all sectors of the population, albeit at different levels depending upon infrastructure and intake. Models can be used to evaluate where VAS maybe more effective. In Cameroon, industrially fortified oil and bouillon cubes reach both the North and the South.65 In evaluating the coverage of overlapping VA programs, the economic model predicted that VAS would be more cost-effective in the North than the South.65

Population-based surveys in children are needed with appropriate biomarkers on randomly selected subgroups9,22,66 to support the recommendation on when to scale back VAS in any country. It is premature to recommend disbanding VAS entirely in the same areas because humans are born with low liver reserves of VA and in many countries infection rates are high, expanding the need for therapeutic VA. In addition to further surveys in young children, more data are needed on lactation patterns, breast milk retinol concentrations, and VA status of women to predict status in infants and toddlers before VAS should be discontinued in these age groups.

Further research on minimally invasive biomarkers that can be used at the population level is urgent. Considering the addition of a VA fortificant to multiple products in some countries, we propose that VA status needs to be evaluated with the most sensitive methods available. While serum retinol concentration can be diagnostic in cases of severe VA deficiency, it has no utility in diagnosing hypervitaminosis A. Furthermore, the study in U.S. cadavers found abnormal liver histology at 3 μmol retinol/g,27 potentially defining this level as toxic. Hypervitaminosis is defined as ≥1 μmol/g and 33% of the U.S. adult and 59% of the Zambian child cohorts were above this cutoff. We do not know the disease ramifications of this level; therefore, further informed research and evaluations in at-risk groups are urgently needed. Serum REs were used in three of the above countries to evaluate potential intoxication. In the U.S. adults, 7.5% of total serum VA as REs was diagnostic when compared directly with liver VA concentrations at autopsy. In the Zambian children, 5% was diagnostic when liver concentrations estimated with the RID test were compared. The South African cohort even had a higher prevalence of elevated REs than the Zambian children and U.S. adults. Fasting REs are not trivial to measure but they can be measured with HPLC, a technique widely available in the world. The cutoffs need to be further investigated using either the RID test or direct measurement of liver VA reserves during surgery or at autopsy.

In areas that have implemented more than one intervention or when shifts in consumption patterns have occurred perhaps due to the introduction of fortified and biofortified foods, VA status should be assessed in children at least every 10 years as recommended by experts.66 Particular attention should be paid to areas that have an active, far-reaching VAS program in preschool children. For population surveillance, representative groups of children and adults need to be carefully selected for the best data using sensitive biomarkers in randomly selected subgroups.22,66 While originally meant to combat VA deficiency, more affluent groups are also recipients of fortified foods and these groups should be included in survey work to assess the presence of excessive intakes and the risk of hypervitaminosis A.

In addition to Zambia, other African members of the Flour Fortification Initiative network include Botswana, Namibia, Nigeria, Lesotho, Swaziland, Malawi, and Zimbabwe. Malawi began fortifying sugar in 2012 and wheat flour, maize flour, and cooking oil followed with a mandate in 2015.67 Each country will need to evaluate the coverage of each intervention and assess where there are overlapping programs in place that could lead to excessive VA intake, and determine when VAS and/or fortification can be scaled back, modified, or eliminated.

Provitamin A carotenoids are considered a safer source of VA because of the regulatory enzymatic mechanisms in place to control the bioconversion to preformed VA leading to slower accumulation of liver reserves over time.68 While ideally individuals should increase provitamin A carotenoid intakes through the dietary inclusion of more fruit and vegetables, the feasibility of using β-carotene as a fortificant instead of retinyl palmitate should be further investigated. Currently, industrial fortification with β-carotene is technically and biologically feasible, but the cost of β-carotene is greater than an equivalent amount of retinyl palmitate.35 β-Carotene would likely need to be encapsulated to avoid discoloration or the introduction of undesirable organoleptic properties.35 However, the addition of β-carotene to ready-to-use, peanut-based therapeutic foods69 is likely feasible because of fat-soluble and color compatibilities.

The prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies, especially VA, has decreased globally due to a variety of factors.70 However, in some areas, there is still a need for vigilance. The case studies described in our review relied on biological indicators to determine the risk of hypervitaminosis A in areas with overlapping programs. Other methods to evaluate overlapping coverage of programs include economic models that use cost-effectiveness and household consumption data.65,70 Policy makers and ministries at the country level should weigh both the biological and economic data available when monitoring public health intervention programs.

Statement.

This manuscript was presented at the World Health Organization (WHO) technical consultation “Risk of Excessive Intake of Vitamins and Minerals through Public Health Interventions–Current Practices and Case Studies,” convened on October 4–6, 2017, in Panamá City, Panamá. This paper is published individually and with related manuscripts as a special issue of Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, the coordinators of which were Drs. Maria Nieves Garcia-Casal and Juan Pablo Peña-Rosas. The special issue is the responsibility of the editorial staff of Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, who delegated to the coordinators the preliminary supervision of both technical conformity to the publishing requirements of Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences and general oversight of the scientific merit of each article. The workshop was supported by WHO, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this paper; they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the WHO. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and are not attributable to the sponsors, publisher, or editorial staff of Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jesse Sheftel for his assistance in preparing the figures. This work was commissioned and financially supported by the Evidence and Programme Guidance Unit, Department of Nutrition for Health and Development of the WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. The case study in the United States was supported by NIH R01 DC004428 (PI N.V. Welham).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. 2011. Guideline: vitamin A supplementation in infants and children 6–59 months of age. Accessed June 6, 2018. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/micronutrients/guidelines/vas_6to59_months/en/. [PubMed]

- 2.Tanumihardjo SA 2018. Nutrient-wise review of evidence and safety of fortification: vitamin A. In Food Fortification in a Globalized World. Mannar MGV & Hurrell RF, Eds.: 247–253. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Penniston KL & Tanumihardjo SA. 2003. Vitamin A in dietary supplements and fortified foods: too much of a good thing? J. Am. Diet. Assoc 103:1185–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLaren DS 1964. Xerophthalmia: a neglected problem. Nutr. Rev 22:289–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West KP Jr. & Sommer A. 1984. Periodic, Large Oral Doses of Vitamin A for the Prevention of Vitamin A Deficiency and Xerophthalmia: A Summary of Experiences. Washington, D.C.: The Nutrition Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Margarine Association of the Countries of Europe. 2004. Code of Practice on vitamin A & D fortification of fats and spreads. IMACE Code of Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dary O & Mora JO. 2002. Food fortification to reduce vitamin A deficiency: International Vitamin A Consultative Group recommendations. J. Nutr 132(Suppl.): 2927S–2933S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peña-Rosas JP, Garcia-Casal MN, Pachón H, et al. 2014. Technical considerations for maize flour and corn meal fortification in public health: consultation rationale and summary. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci 1312: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanumihardjo SA 2015. Vitamin A fortification efforts require accurate monitoring of population vitamin A status to prevent excessive intakes. Procedia Chem. 14: 398–407. [Google Scholar]

- 10.ChartsBin Statistics Collector Team. 2016. Country income groups (World Bank Classification), ChartsBin.com. Accessed June 10, 2018. http://chartsbin.com/view/2438. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. 2001. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 65–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. 2016. Nutrient intakes from food and beverages: mean amounts consumed per individual, by gender and age, what we eat in America, NHANES 2013–2014. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahluwalia N, Herrick KA, Rossen LM, et al. 2016. Usual nutrient intakes of US infants and toddlers generally meet or exceed Dietary Reference Intakes: findings from NHANES 2009–2012. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 104: 1167–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valentine AR Davis CR & Tanumihardjo SA. 2013. Vitamin A isotope dilution predicts liver stores in line with long-term vitamin A intake above the current Recommended Dietary Allowance for young adult women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 98:1192–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2015. Questions and answers on FDA’s fortification policy: guidance for industry. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newcomer C & Murphy S. 2001. Guideline for vitamin A & D fortification of fluid milk. The Dairy Practices Council. Bulletin #53. [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Dairy data. Fluid milk sales. Accessed June 6, 2018. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/dairy-data/. [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2016. Food labeling: revision of the food and supplement facts labels. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration. 21 CFR Part 101. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Council for Responsible Nutrition. Supplement use among younger adult generations contributes to boost in overall usage in 2016—more than 170 million Americans take dietary supplements. Accessed June 10, 2018. http://www.crnusa.org/newsroom/supplement-use-among-younger-adult-generations-contributes-boost-overall-usage-2016-more.

- 20.Duitsman PK, Cook LR, Tanumihardjo SA& Olson JA. 1995. Vitamin A in adequacy in socioeconomically disadvantaged pregnant Iowan women as assessed by the modified relative dose response (MRDR) test. Nutr. Res 15: 1263–1276. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanumihardjo SA, Suharno D, Permaesih D, et al. 1995. Application of the modified relative dose response test to pregnant Indonesian women for assessing vitamin A status. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr 49: 897–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanumihardjo SA, Russell RM, Stephensen CB, et al. 2016. Biomarkers of nutrition for development (BOND)— vitamin A review. J. Nutr 146(Suppl.): 1816S–1848S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith FR & Goodman DS. 1976. Vitamin A transport in human vitamin A toxicity. N. Engl. J. Med 294: 805–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krasinski SD, Russell RM, Otradovec C, et al. 1989. Relationship of vitamin A and vitamin E intake to fasting plasma retinol, retinol-binding protein, retinyl esters, carotene, alpha-tocopherol, and cholesterol among elderly people and young adults: increased plasma retinyl esters among vitamin A-supplement users. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 49: 112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mondloch S, Gannon BM, Davis CR, et al. 2015. High provitamin A carotenoid serum concentrations, elevated retinyl esters, and saturated retinol-binding protein in Zambian preschool children are consistent with the presence of high liver vitamin A stores. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 102: 497–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanumihardjo SA 2013. Vitamin A and bone health: the balancing act. J. Clin. Densitom 16: 414–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsen K, Suri DJ, Davis CR, et al. Serum retinyl esters are positively correlated with analyzed total liver vitamin A reserves collected from US adults at time of death. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 10.1093/ajcn/nqy190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mora JO & Dary O. 1994. Deficiencia de vitamina A y acciones para su prevención y control en América Latina y el Caribe, 1994. Bol. Oficina Sanit. Panam 117: 519–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fiedler JL & Hellaranta M. 2010. Recommendations for improving Guatemala’s food fortification program based on Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) data. Food Nutr. Bull 31: 251–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazariegos M, Martínez C, Mazariegos DI, et al. 2016. Análisis de la situación y tendencias de los micronutrientes clave en Guatemala, con un llamado a la acción desde las políticas públicas. FHI 360/FANTA, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Instituto de Nutrición de Centro América y Panamá (INCAP) y Comité Interdepartamental de Nutrición para la Defensa Nacional. 1972. Nutritional evaluation of the population of Central America and Panama. Regional summary. DHEW Publication No. HSM 72–8120. US Health, Education and Wellbeing Department, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social de Guatemala (MSPAS). 1996. Informe de la Encuesta Nacional de Micronutrientes 1995. Guatemala. [Google Scholar]

- 33.INCAP. 2012. Sistema de Vigilancia de la Malnutrición en Guatemala (SIVIM) 2011, Informe Completo. Guatemala. [Google Scholar]

- 34.INCAP. 2015. Informe del Sistema de Vigilancia Epidemiológica de Salud y Nutrición-SIVESNU-2013, informe final. Guatemala. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanumihardjo SA, Mokhtar N, Haskell MJ & Brown KH. 2016. Assessing the safety of vitamin A delivered through large-scale intervention programs: workshop report on setting the research agenda. Food Nutr. Bull 37(Suppl.): S63–S74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arroyave G, Aguilar JR, Flores M & Guzman MA. 1979. Evaluation of sugar fortification with vitamin A at the national level. Pan American Health Organization, Pan American Sanitary Bureau, Regional Office of the World Health Organization, Washington, D.C. PAHO scientific Publication No. 384. [Google Scholar]

- 37.The World Bank. Vitamin A supplementation coverage rate (% of children ages 6–59 months). Accessed May 29, 2018. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SN.ITK.VITA.ZS?locations=GT.

- 38.The World Bank. Vitamin A supplementation coverage rate (% of children ages 6–59 months). Accessed May 29, 2018. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SN.ITK.VITA.ZS.

- 39.Fiedler J, Lividini K, Kabaghe G, et al. 2013. Assessing Zambia’s industrial fortification options: getting beyond changes in prevalence and cost-effectiveness. Food Nutr. Bull 34: 501–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kafwembe E 2009. The vitamin A status of Zambian children in a community of vitamin A supplementation and sugar fortification strategies as measured by the modified relative dose response (MRDR) test. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res 79: 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanumihardjo SA, Ball A-M, Kaliwile C & Pixley KV. 2017. The research and implementation continuum of biofortified sweet potato and maize in Africa. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci 1390: 88–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hotz C, Chileshe J, Siamusantu W, et al. 2012. Vitamin A intake and infection are associated with plasma retinol among pre-school children in rural Zambia. Public Health Nutr. 15: 1688–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gannon B, Kaliwile C, Arscott SA, et al. 2014. Biofortified orange maize is as efficacious as a vitamin A supplement in Zambian children even in the presence of high liver reserves of vitamin A: a community-based, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 100: 1541–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanumihardjo SA, Gannon BM, Kaliwile C & Chileshe J. 2015. Hypercarotenodermia in Zambia: which children turned orange during mango season? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr 69: 1346–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Serlemitsos J & Fusco H. 2001. Vitamin A fortification of sugar in Zambia. Accessed June 10, 2018. http://www.a2zproject.org/~a2zorg/pdf/zambiasugar.PDF. [Google Scholar]

- 46.World Health Organization. 2011. Guideline: vitamin A supplementation in postpartum women. Geneva: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Central Statistical Office (CSO) [Zambia], Ministry of Health (MOH) [Zambia], and ICF International. 2014. Zambia demographic and health survey, 2013–14. Rockville, MD: Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Health, and ICF International. [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Food and Nutrition Commission, Zambia and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA. 2004. Report of the national survey to evaluate the impact of vitamin A interventions in Zambia in July and November 2003. Lusaka, Zambia, and Atlanta, GA: NFNC and CDC. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bresnahan KA, Chileshe J, Arscott S, et al. 2014. The acute phase response affected traditional measures of micronutrient status in rural Zambian children during a randomized, controlled feeding trial. J. Nutr 144: 972–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palmer AC, Siamusantu W, Chileshe J, et al. 2016. Provitamin A-biofortified maize increases serum β-carotene, but not retinol, in marginally nourished children: a cluster-randomized trial in rural Zambia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 104: 181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Labadarios D & van Middelkoop A, Eds. 1995. Children aged 6–71 months in South Africa, 1994: their anthropometric, vitamin A, iron and immunisation coverage status. The South African Vitamin A Consultative Group (SAVACG), Pretoria. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Labadarios D, Ed. 2007. National food consumption survey: fortification Baseline: South Africa, 2005. Department of Health, Pretoria. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shisana O, Labadarios D, Rehle T, et al. 2014. South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2012 (SANHANES-1). The Health and Nutritional Status of the Nation. Cape Town: HSRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Department of Health. 2003. Regulations relating to the fortification of certain foodstuffs. Accessed March 11, 2018. http://www.health.gov.za/index.php/2014-03-17-09-09-38/legislation/joomla-split-menu/category/123-reg2003?download=265:regulations-relating-to-the-fortification-of-foodstuffs.

- 55.Yusufali R, Sunley N, de Hoop M & Panagides D. 2012. Flour fortification in South Africa: post-implementation survey of micronutrient levels at point of retail. Food Nutr. Bull 33(Suppl.): S321–S329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Jaarsveld PJ, Faber M & van Stuijvenberg ME. 2015. Vitamin A, iron, and zinc content of fortified maize meal and bread at the household level in 4 areas of South Africa. Food Nutr. Bull. 36: 315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Department of Health. 2004. Guidelines for the implementation of vitamin A supplementation. Pretoria: Nutrition Directorate, National Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Massyn N, Day C, Dombo M, et al. , Eds. 2013. District health barometer 2012/13. Health Systems Trust, Durban. [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Stuijvenberg ME, Schoeman SE, Lombard CJ & Dhansay MA. 2012. Serum retinol in 1–6-year-old children from a low socio-economic South African community with a high intake of liver: implications for blanket vitamin A supplementation. Public Health Nutr. 15: 716–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nel J, van Stuijvenberg ME, Schoeman SE, et al. 2014. Liver intake in 24–59-month-old children from an impoverished South African community provides enough vitamin A to meet requirements. Public Health Nutr. 17: 2798–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tanumihardjo SA 2014. Usefulness of vitamin A isotope methods for status assessment: from deficiency to excess. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res 84(Suppl. 1): 16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Penniston KL & Tanumihardjo SA. 2006. The acute and chronic toxic effects of vitamin A. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 83: 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Semba RD 2012. The Vitamin A Story: Lifting the Shadow of Death. Basel: Karger. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Neidecker-Gonzales O, Nestel P & Bouis H. 2007. Estimating the global costs of vitamin A capsule supplementation: a review of the literature. Food Nutr. Bull 28: 307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vosti SA, Kagin J, Engle-Stone R & Brown KH. 2015. An economic optimization model for improving the efficiency of vitamin A intervention programs: an application to young children in Cameroon. Food Nutr. Bull 36: S193–S207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wirth JP, Petry N, Tanumihardjo SA, et al. 2017. Vitamin A supplementation programs and country-level evidence of vitamin A deficiency. Nutrients 9: 190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.FFI Newsletter June 2015. 2015. Accessed June 6, 2018. http://www.ffinetwork.org/about/stay_informed/newsletters/Q2_2015.html#entry1.

- 68.Tanumihardjo SA 2008. Food-based approaches for ensuring adequate vitamin A nutrition. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf 7: 373–381. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Klemm RDW, Palmer AC, Greig A, et al. 2016. A changing landscape for vitamin A programs: implications for optimal intervention packages, program monitoring, and safety. Food Nutr. Bull 37: S75–S86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fiedler JL & Lividini K. 2014. Managing the vitamin A program portfolio: a case study of Zambia, 2013–2042. Food Nutr. Bull 35: 105–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]