Abstract

Methionine sulfoxide reductase (Msr) is a family of enzymes that reduces oxidized methionine and plays an important role in the survival of bacteria under oxidative stress conditions. MsrA and MsrB exist in a fusion protein form (MsrAB) in some pathogenic bacteria, such as Helicobacter pylori (Hp), Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Treponema denticola. To understand the fused form instead of the separated enzyme at the molecular level, we determined the crystal structure of HpMsrABC44S/C318S at 2.2 Å, which showed that a linker region (Hpiloop, 193–205) between two domains interacted with each HpMsrA or HpMsrB domain via three salt bridges (E193-K107, D197-R103, and K200-D339). Two acetate molecules in the active site pocket showed an sp2 planar electron density map in the crystal structure, which interacted with the conserved residues in fusion MsrABs from the pathogen. Biochemical and kinetic analyses revealed that Hpiloop is required to increase the catalytic efficiency of HpMsrAB. Two salt bridge mutants (D193A and E199A) were located at the entrance or tailgate of Hpiloop. Therefore, the linker region of the MsrAB fusion enzyme plays a key role in the structural stability and catalytic efficiency and provides a better understanding of why MsrAB exists in a fused form.

Keywords: MsrAB, fusion protein, linker region, catalytic efficiency

1. Introduction

The sensitivity of amino acid residues to oxidation is diverse [1]. Among all amino acids, methionine has a very high tendency to oxidize, and when it is present in high concentrations on the surface of a specific protein it can be oxidized without affecting the function of the protein [1]. For certain proteins, methionine oxidation results in their inactivation or activation [2,3,4]. Methionine sulfoxide reductase (Msr) is an antioxidant enzyme that reduces oxidized methionine. Msr plays an essential role in the survival of bacteria under oxidative stress conditions, as shown in deletion mutants [5,6,7]. Methionine oxidation produces diastereomeric compounds, L-methionine S-sulfoxide and L-methionine R-sulfoxide. Two different classes of Msr, named MsrA and MsrB, show distinct preferences for each diastereomer. MsrA is stereospecific for reducing L-methionine S-sulfoxide, whereas MsrB is stereospecific for the reduction of the R diastereomer [1,5,6,8,9]. The absence of MsrA or MsrB causes increased sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide, implying the importance of reducing Met-(R, S)-O [1,5,6,10,11]. MsrA and MsrB exist as separate enzymes in most organisms; however, more than 46 bacterial species contain the fused form of MsrA and MsrB [12,13,14]. The fused form has two domain sequences, MsrAB (MsrA–MsrB) and MsrBA (MsrB–MsrA) [12]. Currently, it is unclear why some bacteria, especially pathogenic bacteria, such as Helicobacter pylori (Hp), Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Treponema denticola, possess MsrAB as a fusion protein instead of individual enzymes [15,16]. The catalytic activities of the MsrAB fusion protein are higher than those of the individual enzymes, MsrA and MsrB [15,16,17,18]. Many structures from each domain have been reported [18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Two crystal structures of the MsrAB fusion protein have been determined to date [15,16]. In both crystal structures, MsrA and MsrB are connected by a linker region (named the iloop) composed of a short peptide that plays a role in the catalytic efficiency or structural stability of the fusion protein; however, the exact function or reason behind the formation of the fusion protein has not been determined to date [15,16]. Various proteins from the human gastric pathogen H. pylori are linked to Msr enzymes. Many of these proteins, such as GroEL and recombinase, are more methionine-rich than other bacterial proteins, and are oxidized under oxidative stress and rescued by the activity of Msr enzymes [25]. Thus, Msr proteins repair oxidative damage to methionine residues via the oxidation/reduction cycle, serve as scavengers of reactive oxygen species, and protect cells from more widespread oxidative damage [26,27]. Here, we determined the crystal structure of the fusion MsrA–MsrB protein from H. pylori (HpMsrAB) at a resolution of 2.2 Å. In addition, biochemical and kinetic analyses of HpMsrAB, its single domain forms (HpMsrA and HpMsrB), various catalytic mutants, and iloop mutants were undertaken. We compared the structure of HpMsrAB with other fused proteins and examined its specific role based on kinetic analyses. These results support the idea that the iloop of the MsrAB fusion enzyme plays a key role in the structural stability and catalytic efficiency and provides a better understanding of why MsrAB exists in a fused form and the specific role of the iloop in fused proteins from pathogens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cloning, Expression, and Purification

The MsrAB gene was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using H. pylori strain 26,695 genomic DNA as a template. The forward and reverse oligonucleotide primers of HpMsrAB (amino acid residues 24–359) were 5′-GGAATTC CATATG gaaaacatgggatctcaacaccaaa-3′ and 5′-CCG CTCGAG tta atgcgactttttatcattgatgtatttt-3′. The underlined bases represent the NdeI and XhoI sites, respectively. The PCR products were digested with NdeI and XhoI and ligated into the pET-28a vector (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the recombinant plasmid as a template (E193A, D197A, E193AD197A, E339A, and Y343F). Sequences were confirmed using commercial DNA sequencing (Bionics Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea). The confirmed recombinant plasmid DNA and mutants were introduced into the Escherichia coli BL-21 Star (DE3) strain (Invitrogen) to measure the expression. Cells were cultured in LB medium, and protein expression was induced with 1.0 mM IPTG at 18 °C at an optical density of 0.6 at 600 nm. After induction, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 2700× g for 30 min at 4 °C and disrupted by sonication in buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 3 mM MgCl2) with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The crude cell extract was centrifuged at 17,400× g for 60 min at 4 °C and applied to a HisTrap HP 5 mL column (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). The column was washed with buffer A containing 40 mM imidazole, and the protein was eluted by a linear gradient with buffer A and 40–500 mM imidazole. The eluted protein was concentrated using an Amicon Ultra-15 (molecular weight cutoff 10,000; Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), and loaded onto a Superdex 75 HiLoad 16/60 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer B (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 0.1 M NaCl, and 3 mM MgCl2). The protein bands were detected by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R. The purified protein was concentrated to a final concentration of approximately 50 mg/mL, determined using Bradford’s method with bovine serum albumin as a standard [28].

2.2. Crystallization and Data Collection

The sitting drop vapor diffusion method using various screening kits from Hampton Research (Aliso Viejo, CA, USA) (Crystal Screen, Index, SaltRx, PEG/Ion, PEGRx, Crystal Screen Cryo, and Crystal Screen Lite) and Qiagen (Venlo, The Netherlands) (Classic suites I and II) was used for the initial crystallization screening. Optimization of crystallization was performed using the conventional vapor diffusion method with a 24-well VDX plate (Hampton Research) at 293 K. Hanging drops were established by mixing 1 µL of each protein solution concentrated at approximately 50 mg/mL equilibrated with 500 µL of the reservoir solution. HpMsrABC44S/C318S (24–359) (100 µM) was incubated with 200 µM of dabsyl-Met-O for 60 min at 4 °C, and the protein was concentrated to approximately 50 mg/mL. Finally, the appropriate crystals of HpMsrABC44S/C318S (24–359) with Met-(R,S)-O for X-ray diffraction data were obtained in 0.1 M sodium acetate (pH 4.6) and 2.0 M sodium formate. X-ray diffraction data were collected on beamline 11C (Micro-MX) at the Pohang Accelerator Light Source (Pohang, Korea). The wavelength of the synchrotron X-ray was 1000 Å, and the maximum resolution was 2.2 Å. The collected images were indexed, integrated, and scaled using the HKL-2000 program [29].

2.3. Kinetic Analysis of MsrAB with an Enzymatic Assay

The dithiothreitol (DTT)-dependent assay using dabsyl-Met-O as a substrate [30] was performed using purified proteins dialyzed into an appropriate buffer containing 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5) and 50 mM NaCl. The reaction mixture contained 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 200 µM dabsyl-Met-S-O (for MsrA activity) or dabsyl-Met-R-O (for MsrB activity), 0.26–16 µM Msr proteins, and 20 mM DTT [31,32]. The reaction was performed at 37 °C for 0.5 h, and then the product, dabsyl-Met, was evaluated using high-performance liquid chromatography as described previously [10,31]. The kinetic parameters (Km and kcat) were determined by non-linear regression using GraphPad Prism 5 software (San Diego, CA, USA).

2.4. Structure Determination and Refinement

The initial model of HpMsrABC44S/C318S was solved by molecular replacement with MOLREP [33] using a search model (PDB entry: 5FA9 [15]) in the CCP4 suite [34]. Model building was performed iteratively using the COOT [35] and AutoBuild module [36] in PHENIX [37]. Final refinement was accomplished using the PHENIX program. The final model was validated using MOLPROBITY [38] and had R values of HpMsrABC44S/C318S with an Rfree of 21.4% and an Rwork of 18.8% at 2.2 Å. The data collection and structure refinement statistics of HpMsrABC44S/C318S are shown in Table 1. All structural figures were produced using PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (Version 2.0 SchrÖdinger, LLC, NY, USA).

Table 1.

Crystallographic statistics of HpMsrABC44SC318S.

| HpMsrABC44SC318S | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.00000 |

| Resolution (Å) | 30–2.2 (2.24–2.20) a |

| Space group | P1 |

| Unit cell parameter | a = 52.125, b = 72.505, c = 82.230 α = 93.16°, β = 93.80°, γ = 111.08° |

| Observed/unique reflections | 158,134/53,424 |

| Redundancy | 3.1 (2.3) |

| Completeness (%) | 94.1 (86.6) |

| I/σ | 29.7 (5.32) |

| Rmerge (%) b | 6.3 (17.9) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 30.00–2.2 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) c | 18.8/21.4 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | 39.42 |

| Root-mean-square-deviations | |

| Bond length (Å) | 0.006 |

| Bond angle (°) | 0.759 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 97.7 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0.0 |

| PDB entry | 5FA9 |

a Values in parentheses represent the highest resolution shell. b Rmerge = ∑hkl∑i|Ihkli − ‹Ihkli›|/∑hkl∑i‹Ihkli›. c Rcryst = ∑hkl||Fo| − |Fc||/∑|Fo|.

2.5. Inflection Temperature (Ti) Measurement

Prior to Ti measurement, wild-type (WT) and various HpMsrAB mutants were diluted to a concentration of 1 mg/mL for Tycho NT.6 experiments. The samples were then loaded as duplicates into Tycho NT.6 capillaries (Cat# TY-C001; NanoTemper Technologies; Munich, Germany). Ti measurements were taken using a Tycho NT.6 (NanoTemper Technologies) and calculated by plotting the first derivative of the 350/330 nm ratio against temperature.

2.6. Size-Exclusion Chromatography with Multiangle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS)

SEC-MALS experiments were performed using a fast protein liquid chromatography system (GE Healthcare) connected to a Wyatt MiniDAWN TREOS MALS instrument (Santa Barbara, CA, USA) and a Wyatt Optilab rEX differential refractometer. A Superdex 200 10/300 GL (17-5175-01; GE Healthcare) gel filtration column preequilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DTT was normalized using bovine serum albumin. Individual proteins (HpMsrAB WT, HpMsrA domain, HpMsrB domain, and various mutants, including HpMsrABC44S/C318S, HpMsrABD197A, HpMsrABE193A, HpMsrABE339A, and HpMsrABY343F) were prepared separately by the methods described earlier and were injected (1–2 mg/mL, 0.25 mL) at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. The final purity of the proteins was checked by SDS-gel electrophoresis (Figure S5). Data were analyzed using the Zimm model for static light scattering data fitting and represented using an EASI graph with a UV peak in the ASTRA V software (Wyatt).

3. Results and Discussion

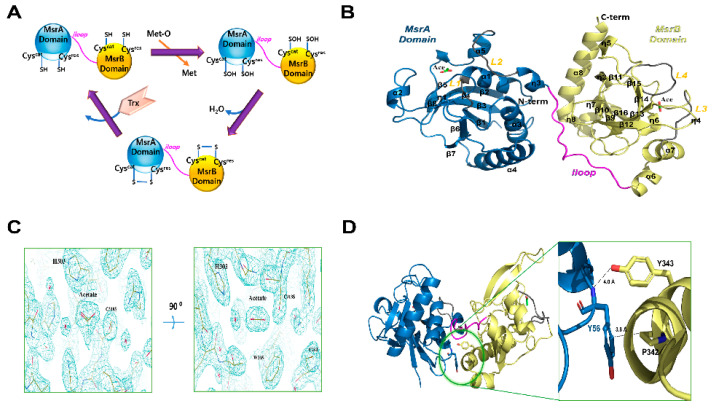

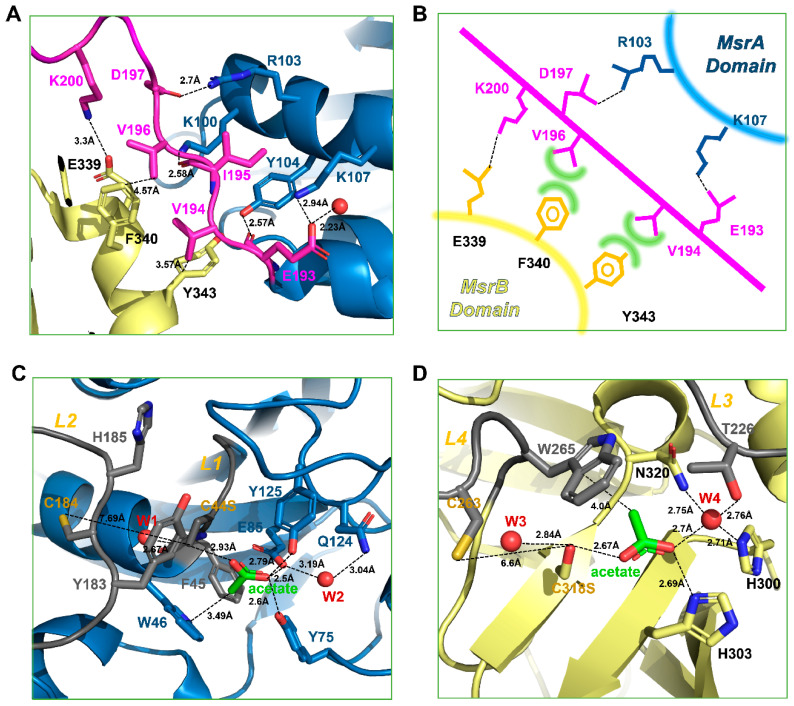

3.1. Overall Structures of HpMsrABC44S/C318S

Initially, we crystallized the catalytic site-specific HpMsrABC44S, HpMsrABC318S, and HpMsrABC44S/C318S mutants with dabsyl-Met-(R,S)-O, which is a substrate analog compound (Figure 1A). However, a crystal grew in the HpMsrABC44S/C318S mutant without the substrate. The crystal structure of HpMsrABC44S/C318S was solved at 2.2 Å and belonged to the P1 space group (Table 1). There were two protomers (MolA and MolB) in the asymmetric unit (Figure S1). We could not identify the electron density map of any substrate in the crystal structure, despite using co-crystallization with dabsyl-Met-(R,S)-O. The purified HpMsrABC44S/C318S was monomeric in the solution based on SEC and SEC-MALS (Figure S2). Each monomer of HpMsrABC44S/C318S had two catalytic domains, HpMsrA (34–192, residue number) and HpMsrB (206–357), which were linked by the linker region, iloop (193–205) (Figure 1B). The overall fold was similar to the two fusion MsrAB structures (PDB entry: 3e0m and 5fa9) [15,16] (Figure 2A). Each domain, HpMsrA and HpMsrB, was similar to the formerly reported MsrAs and MsrBs, respectively, except for the C-terminal long α-helix (α8) of HpMsrB (Figure 1A and Figure S3). The HpMsrA domain consisted of a central antiparallel β-sheet containing strands β1–β8 surrounded by four α-helices (α1–α4) on the side, one small α-helix (α5), and two 310-helices (η1, η2) (Figure 1B). The HpMsrB domain consisted of two parallel β-sheets that contained three β-strands (β13, β9, and β15), three other strands (β10, β14, and β16), two α-helix bundles (α7 with α6 and long C-terminal α-helix α8) lining both sides of the β-sheets, and three small α-helices (α9–α11) (Figure 1B). The root-mean-square deviations (rmsd) of HpMsrA for SpMsrA (sequence identity 56.6%) and TdMsrA (sequence identity 58.2%) were 0.734 Å over 145 Cα atoms and 0.697 Å over 158 Cα atoms, respectively. HpMsrB generated rmsd values of 0.822 Å (141 Cα) and 0.419 Å (141 Cα) for SpMsrB (sequence identity 62.4%) and TdMsrB (sequence identity 61.7%), respectively (Figure S3). The iloop of HpMsrAB consisted of 13 residues (193–205) and was incorporated into the flank of HpMsrB (Figure 1B). The two domains of HpMsrAB, HpMsrA and HpMsrB interacted with each other via hydrophobic interactions (Figure 1D). There were three salt bridges and several hydrogen bonding interactions in the iloop (Figure 3A,B). The first salt bridge was formed between Oδ1 of D197 in the iloop and NH1 of R103 in helix α3 of HpMsrA (~2.7 Å). The second salt bridge was formed between Oε1 of E193 in the iloop and Nζ of K107 of HpMsrA (~2.94Å). The third salt bridge was formed between Nζ of K200 of the iloop and Oδ1 of E339 of HpMsrB (~3.30Å). In addition, two hydrogen bonds were formed between the iloop and HpMsrA: one between the carbonyl oxygen atom of I195 in the iloop and the Nζ of K100 in HpMsrA (~2.58 Å), and the other between the carbonyl oxygen atom of E193 in the iloop and the OH of Y104 in HpMsrA (~2.57 Å) (Figure 3A). Among the three salt bridges, D197 was completely conserved in the fusion of MsrABs from the pathogen (Figure 2A,B). Therefore, these salt bridges played a role in the structural stability and functional catalytic efficiency of the fusion protein MsrAB from the pathogen.

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of HpMsrAB. (A) Cartoon model of the general catalyzed chemical reactions of MsrAB (B) Ribbon diagram of the overall structure of HpMsrABC44S/C318S. The N-terminal domain, MsrA domain (HpMsrA, 34−192) and the C-terminal domain, MsrB domain (HpMsrB, 206−357) are colored sky blue and pale yellow, respectively. The linker region connecting HpMsrA and HpMsrB (residues 193−205), the iloop, is colored magenta. Loops (L1, 42−45 and L2, 181−187) of the HpMsrA domain and loops (L3, 224−229 and L4, 259−266) of the HpMsrB domain are colored gray. Helices (α1–α8), β-strands (β1–β16), and 310-helices (η1–η8) are labeled. Two acetate molecules are represented as stick models colored green. (C) 2Fo-Fc electron density map (1.2 sigma cutoff) around the acetate molecule in the crystal structure. (D) Close-up view of a possible hydrophobic interaction (<4 Å) between Y56 of the HpMsrA domain and P342 of the HpMsrB domain in the crystal structure. The dotted line indicates the distance between the OH of Y343 and the amide N atom of Y56 (~4.0 A), which could not form hydrogen bonds.

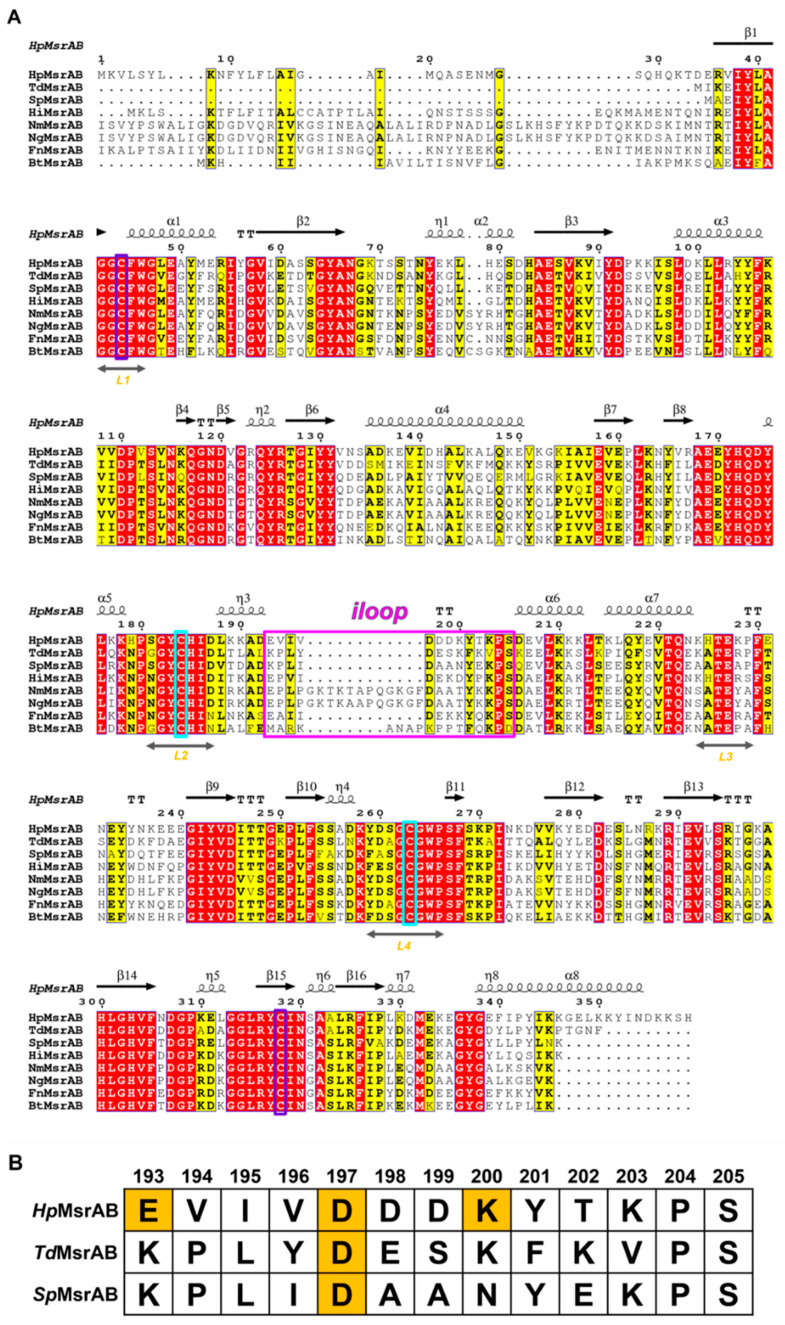

Figure 2.

Multiple sequence alignment of Helicobacter pylori methionine sulfoxide reductase AB (HpMsrAB). (A) Multiple sequence alignment of MsrAB homologs in Helicobacter pylori (Hp, Swiss-Prot entry O25011), Treponema denticola (Td, Swiss-Prot entry Q73PT7), Streptococcus pneumoniae (Sp, Swiss-Prot entry P0A3Q9), Haemophilus influenzae (Hi, Swiss-Prot entry P45213), Neisseria meningitidis (Nm, Swiss-Prot entry Q9JWM8), Neisseria gonorrheae (Ng, Swiss-Prot entry P14930), Fusobacterium nucleatum (Fn, Swiss-Prot entry Q8R5 × 2), and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (Bt, Swiss-Prot entry Q8A4U8). Catalytic and resolving Cys residues are shown in purple and cyan, respectively. The completely conserved and similar group amino acids are represented by red and yellow letters, respectively. Hpiloop, the linker region, is displayed in a magenta box. (B) Comparison of iloops between HpMsrAB, TdMsrAB, and SpMsrAB. Partial sequence alignment of the iloops in HpMsrAB, TdMsrAB, and SpMsrAB. The residues associated with the salt bridge interactions in Hpiloops between MsrA and MsrB domains are shown in orange boxes.

Figure 3.

Binding interface and active sites of HpMsrA and HpMsrB. (A) Zoomed view of the binding interface between HpMsrA and HpMsrB. The amino acids involved in the interaction are displayed as stick models. The residues (E193, D197, and K200) in the iloops are associated with the salt bridge interactions and the residues (E193, V194, and I195) in the iloops are associated with the hydrogen bonds or hydrophobic interactions. (B) Illustration of salt bridges and hydrophobic interactions. Dashed black lines represent salt bridges, and green curves represent hydrophobic interactions. (C) Zoomed view of the active site of the HpMsrA domain. Residues that constitute the active site are displayed as stick models. Two loops involved in forming the active site, L1 (residues 42–45) and L2 (residues 181–187), are colored gray. The acetate molecule is displayed as a stick model colored green. The water molecules are displayed as spherical models colored red. (D) Zoomed view of the active site of the HpMsrB domain. Residues that constitute the active site are displayed as stick models. Two loops associated in forming the active site, L3 (residues 224–229) and L4 (residues 259–266), are colored gray.

3.2. Active Sites of HpMsrABC44S/C318S

The known active sites include highly conserved catalytic cysteine (C44S for HpMsrA and C318S for HpMsrB) and resolving cysteine (C184 for HpMsrA and C263 for HpMsrB) in HpMsrAB (Figure 2A and Figure 3C,D). Many conserved residues were found near the cysteine active site, including -42GGCFWG47- for MsrA and -313GGLRYCIN320- for MsrB, which face each other, and histidine residues (H185 for MsrA and H303 for MsrB) that coordinate the oxygen atom of L-methionine sulfoxide [15,34]. These residues within the active site region of HpMsrAB were well conserved across species (Figure 2A). Even though we co-crystallized an HpMsrAB mutant (C44S/C318S) protein with the substrate analog compound, dabsyl-Met-(R,S)-O, no analog compounds were found in the active sites of HpMsrA or HpMsrB. Based on several crystallographic analyses of Msrs in different states (substrate-bound, oxidized, or reduced), our structure showed a reduced-state structure in the catalytic steps [21]. C44S of the HpMsrA domain was positioned in the loop (L1) between strands β1 and α1, and the active site region was formed with two loops (L1, residues 42–45 and L2, residues 181–187) and strand β3 around the C44S residue (Figure 3C). The resolving C184S position was located at L2 and positioned ~7.7 Å from the catalytic C44S. This structure showed that the reduced form of HpMsrA and the oxygen atom of C44S were formed with well-ordered water molecules (~2.67 Å). Y183 and H185, which are well-conserved residues in this region, were expected to participate in the configuration of the active site (Figure 3C). F45 and W46 formed a hydrophobic pocket, and E85 and Y125 contributed to the formation of the active site (Figure 3C). The active site of HpMsrB was positioned in antiparallel β-strands β14 and β15, and two loops (L3, residues 224–229 and L4, residues 259–266) (Figure 3D). The distance between C318S situated on strands β15 and C263 (resolving cysteine) on L4 was ~6.6 Å (Figure 3D). We found two acetate molecules in the active site pocket, which was used as the crystallization buffer (0.1 M sodium acetate) (Figure 1B,C and Figure 3C,D). The two acetate molecules showed an sp2 planar electron density map in the crystal structure (Figure 1C). In the active site of the HpMsrA domain, the carboxyl group of the acetate ion interacted with Oδ1 of E85 (2.50 Å), OH of Y75 (2.60 Å), OH of Y125 (2.79 Å), and Oδ of S44 (2.93 Å). The methyl group of the acetate ion interacted with W46 (3.49 Å). Two well-ordered water molecules in the active pocket were found near the active residues. The hydrogen bonding of water (W1) formed with the Oδ1 of C44S (2.67 Å), which is an active cysteine residue. Another water molecule (W2) interacted with Oδ1 of E85 (3.19Å) and Nδ2 of Q124 (3.04Å) (Figure 3C). The binding interaction of the acetate ion of the HpMsrB domain was similar to that of the HpMsrA domain. The interaction residues were as follows: the carboxyl group of the acetate ion interacted with Nε of H303 (2.69 Å), one water molecule (W4, 2.70 Å), and Oδ of C318S (2.67 Å). The methyl group of the acetate ion interacted with W265 (4.0 Å). Two well-ordered water molecules in the active pocket were found near the active residues. The hydrogen bonding of water (W3) formed with Oδ of C318S (2.84 Å), which is an active cysteine residue. The other water molecule (W4) interacted with Oγ of T226 (2.76 Å), Nδ of N320 (2.75 Å), and Nδ of H300 (2.71 Å) (Figure 3D). Overall, the interaction residues of acetate ions were well conserved in the pathogens (Figure 2A). A comparison of the structural locations of the active site residues of HpMsrAB showed that its active site structure was comparable to that of other reduced structures of MsrABs (Figure S3). Therefore, both the active sites of HpMsrAB were reduced.

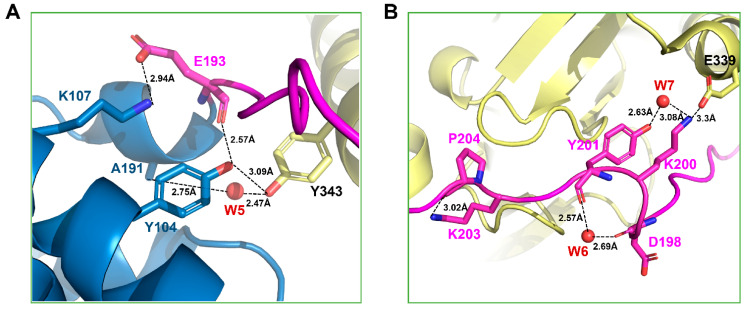

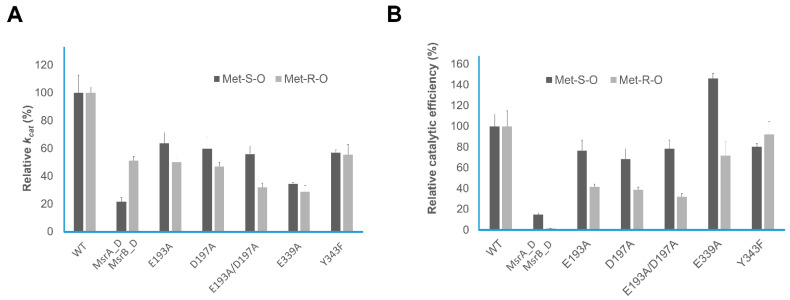

3.3. Biochemical and Kinetic Analysis of HpMsrAB

The linker region (iloop) linking the two domains (HpMsrA and HpMsrB domain) might play a role in controlling the catalytic efficiency of HpMsrAB, similar to the other fusion MsrAB proteins (SpMsrAB [15] and TdMsrAB [16]). The iloop might stabilize the spots of each domain by networking with domains via hydrophobic interactions or several hydrogen bonds, as demonstrated in the SpMsrAB and TdMsrAB structures [15,16]. The iloop of HpMsrAB (Hpiloop) was composed of 13 residues (193–205), some of which participated in interactions (salt bridges, hydrogen bonds, or hydrophobic interactions) with HpMsrA and HpMsrB (Figure 3A). Hpiloop did not contain any helix structures such as the iloop of TdMsrAB (Tdiloop), whereas the iloop of SpMsrAB (Spiloop) included helix structures. There was one salt bridge interaction between K200 of Hpiloop and D339 of HpMsrB (3.30 Å); however, there were two salt bridges between Hpiloop and HpMsrA, namely D197-R103 (2.70 Å) and E193-K107 (2.94 Å). Moreover, there were hydrophobic interactions, such as V196-F340 (~4.6 Å) and V194-Y343 (~3.6 Å), between Hpiloop and HpMsrA (Figure 3A,B). These interactions between Hpiloop and each HpMsrA or HpMsrB might help the two domains maintain their secondary structures. Therefore, the iloop may contribute to the structural stability of each domain in HpMsrAB, similar to other fusion MsrABs. To examine whether the HpMsrAB fusion protein can alter catalytic activity, we performed biochemical assays of several iloop mutants of HpMsrAB (Table 2). We prepared several mutants, and blocking the salt bridges between Hpiloop and HpMsrB had a significant effect on the enzyme activity of HpMsrAB. We also mutated the other interaction residues, E339A and Y343F, which are located on the C-terminal helix. E339 interacted with K200-E339 via a salt bridge, and Y343 interacted with the carbonyl groups of A191, E193, and water molecules (W5) via a hydrogen bond (Figure 4A,B). We measured the thermal stability of all the proteins to check for stable protein folding (Figure S4). The kcat values of HpMsrABE193A and HpMsrABD197A for Met-R-O were 2.0- and 2.13-fold lower than that of WT HpMsrAB, respectively. Moreover, the kcat value for Met-S-O was 1.57- and 1.65-fold lower than that of the WT, respectively. In the double mutant form of HpMsrABE193A/D197A, the kcat values for Met-R-O and Met-S-O decreased by 3.13- and 1.79-fold, respectively, compared to that of the WT (Figure 5A). The kcat values of HpMsrABE339A and HpMsrABY343F for Met-R-O were 3.50- and 1.81-fold lower than that of WT HpMsrAB, respectively (Figure 5A). Additionally, the kcat values of HpMsrABE339A and HpMsrABY343F for Met-S-O were 2.91- and 1.62-fold lower than thay of the WT, respectively. Small differences in Km values were observed for Met-S-O and Met-R-O in the mutants HpMsrABE193A, HpMsrABD197A, and HpMsrABE193A/D197A (Table 2). However, in HpMsrABE339A and HpMsrABY343F, the Km value for Met-S-O was 4.25-fold higher than that of the WT HpMsrAB, whereas it was not considerably altered in Met-R-O. Overall, compared with the WT, the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of HpMsrABE193A/D197A was 3.13-fold lower for Met-R-O and 1.28-fold lower for Met-S-O (Figure 5B, Table 2). Compared to the WT, the catalytic efficiency of each domain, HpMsrA or HpMsrB, was 6.82-fold lower for Met-S-O and 67.1-fold lower for Met-R-O (Figure 5B). Overall, substrate binding of the HpMsrB domain could be influenced by the disturbance of the interface between Hpiloop and HpMsrA. These biochemical analyses imply that the interaction between Hpiloop and HpMsrA plays a role in HpMsrB catalytic activity and that this interaction also influences the catalytic activity of MsrA. In summary, the overall fold or active site configurations of the HpMsrA and HpMsrB domains might be considerably disturbed as they are divided from the fusion HpMsrAB form, suggesting that structural factors influence the catalytic efficiency of HpMsrAB. For HpMsrAB, the catalytic efficiency of the HpMsrB domain was more affected than that of HpMsrA, resulting in an interaction between the iloop and HpMsrA. By abolishing these interactions, such as with E193A and D197A, the fusion protein HpMsrAB might not fold stably.

Table 2.

Kinetic analyses of H. pyroli MsrAB, HpMsrA, HpMsrB domain, and its mutants.

| Form | Substrate |

Km (mM) |

kcat (min−1) |

kcat/Km (mM−1 min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Met-S-O | 0.17 ± 0.06 | 10.2 ± 1.3 | 60 ± 7 |

| Met-R-O | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 9.4 ± 0.4 | 188 ± 8 | |

| MsrA_D | Met-S-O | 0.25 ± 0.09 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 8.8 ± 1.2 |

| MsrB_D | Met-R-O | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.2 |

| E193A | Met-S-O | 0.14 ± 0.06 | 6.5 ± 0.8 | 46 ± 6 |

| Met-R-O | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 78 ± 5 | |

| D197A | Met-S-O | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 6.1 ± 0.9 | 41 ± 6 |

| Met-R-O | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 73 ± 5 | |

| E193A/D197A | Met-S-O | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 5.7 ± 0.6 | 47 ± 5 |

| Met-R-O | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 60 ± 6 | |

| E339A | Met-S-O | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 88 ± 3 |

| Met-R-O | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 135 ± 25 | |

| Y343F | Met-S-O | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 48 ± 2 |

| Met-R-O | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 5.2 ± 0.7 | 173 ± 23 |

WT, wild-type MsrAB form; MsrA_D, MsrA domain form; MsrB_D, MsrB domain form.

Figure 4.

Interactions around the Y343 and E339 residues. (A) Magnified view of the interaction residue around Y343. The residues involved in the interaction are represented as stick models. The water molecule is represented as a spherical model colored red and (B) Close-up view of the interaction residue around E339.

Figure 5.

Relative kinetic values. (A) Relative kcat values of HpMsrAB, HpMsrA, HpMsrB, and HpMsrAB mutants and (B) Relative catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of HpMsrAB, HpMsrA, HpMsrB, and HpMsrAB mutants.

3.4. Structural Comparison with Other Fusion MsrAB Proteins

To understand the structural differences between the fusion MsrAB proteins from pathogenic bacteria, HpMsrAB structures were compared with those of TdMsrAB and SpMsrAB. The HpMsrAB shared ~51.4% and ~52.9% sequence identity with TdMsrAB and SpMsrAB (Figure 2A) and rmsds were ~2.81 and ~1.66 Å for 324 Cα (Figure S3), respectively. When the structures of the MsrA domains of the fusion MsrAB from the three species were superimposed, the MsrB domain orientation was relatively different (Figure S3), which resulted in the flexibility or different hydrogen bonding positions of the Hpiloop. For Neisseria gonorrheae (Ng) PilB, there were reported not full fusion NgMsrAB structure but the domain structures of NgMsrA or NgMsrB [19,39]. Thus, we also superimposed the MsrA or MsrB domain structures of PilB (NgMsrA:PDB1H30 or NgMsrB:PDB1L1D) [19,39] (Figure S3). The rmsds of NgMsrA for HpMsrA and NgMsrB for HpMsrB were 3.88 Å (151 Cα) and 0.779 Å (144 Cα) atoms, respectively. The overall fold of NgMsrB was more similar to that of NgMsrA. The overall structures of the MsrA and MsrB domains from the three species (H. pylori, S. pneumoniae, and T. denticola) were highly similar (Figure S3), and the active site residues were completely conserved (Figure 2A). E193, D197, and K200, which are involved in salt bridge interactions on the iloop of HpMsrAB, were affected by the catalytic efficiencies of HpMsrAB; however, these residues were not strictly conserved in fusion MsrABs from the pathogen without the D197 position (Figure 2B). In contrast, no significant interaction sites between HpMsrA or HpMsrB domains were found in HpMsrAB, similar to the SpMsrAB structure. Only one hydrophobic interaction site (Y58-P342) was found in HpMsrAB (~3.8 Å) (Figure 1D). For TdMsrAB, they were found in three interacting sites between TdMsrA and TdMsrB [15,16]. No remarkable structural changes in the active residues, such as C44S, C184, C318S, and C263, were observed between the fusion MsrABs from the three pathogens. Therefore, the interaction of the iloop of fusion MsrAB played a key role in the catalytic efficiency or structural stability, and the flexibility of the iloop was an important factor depending on the catalytic efficiency of each domain. For HpMsrAB, the flexibility of the iloop was controlled via three salt bridges.

4. Conclusions

We determined the crystal structure of HpMsrABC44S/C318S at a resolution of 2.2 Å. The results showed that the iloop interacted with HpMsrB via three salt bridges, namely E193-K107, D197-R103, and K200-D339. When the structures of the MsrA domains of the three species (H. pylori, S. pneumoniae, and T. denticola) were superimposed, the orientation of the MsrB domain was relatively different (Figure S3), resulting in the flexibility or different hydrogen bonding positions in the Hpiloop. In addition, we found that the linker region (Hpiloop) connecting HpMsrA and HpMsrB was mandatory for the higher catalytic efficiency of HpMsrAB based on biochemical and kinetic analyses. We mutated salt bridge mutants (E193A and D197A) located at the entrance or tailgate of the Hpiloop. These salt bridges or hydrogen bonding in the iloop region play a role in the structural stability and higher functional catalytic efficiency of the fusion protein MsrAB from the pathogen.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff at the PLS 11C (Micro-MX) beamline in South Korea, Photon Factory 1A, Spring-8 44XU beamline in Japan for allowing us to use their excellent facilities and for their assistance with X-ray data collection. We also thank Kim, M. J. for preparing the SDS-gel photo.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3921/10/3/389/s1, Figure S1. Overall structure of HpMsrAB in an asymmetric unit, Figure S2. Measurement of molecular masses by SEC-MALS, Figure S3. Comparison of iloops between HpMsrAB and SpMsrAB and superimposition of HpMsrAB and SpMsrAB by aligning the MsrA domains, Figure S4. Inflection temperature (Ti) measurement. Ti of HpMsrAB WT and mutants, Figure S5. Image of SDS-gel electrophoresis of WT and mutant HpMsrAB.

Author Contributions

Designed all experiments; cloning, purification, and crystallization: K.L.; collecting and processing the diffraction data: K.L. and S.K.; biochemical analysis: S.K., G.-H.K., S.-H.P., M.S.K. and H.-Y.K.; determined the crystal structure of HpMsrAB: S.K., K.L. and K.Y.H. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript: S.K., K.L., H.-Y.K. and K.Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by 2020R1A2C2005670, 2018M3A9F3055925, and 2019R1I1A1A01056 from the National Research Foundation of Korea and by the 2018 Yeungnam University research grant (to H.K.). K.Y.H. was supported by grants from Korea University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The structure factor and coordinate file have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org, accessed on 11 March 2021) under accession code 7E43.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dhandayuthapani S., Jagannath C., Nino C., Saikolappan S., Sasindran S.J. Methionine sulfoxide reductase B (MsrB) of Mycobacterium smegmatis plays a limited role in resisting oxidative stress. Tuberculosis. 2009;89:S26–S32. doi: 10.1016/S1472-9792(09)70008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Achilli C., Ciana A., Minetti G. The discovery of methionine sulfoxide reductase enzymes: An historical account and future perspectives. Biofactors. 2015;41:135–152. doi: 10.1002/biof.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang B., Moskovitz J. The functions of the mammalian methionine sulfoxide reductase system and related diseases. Antioxidants. 2018;7:122. doi: 10.3390/antiox7090122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim H.-Y. The methionine sulfoxide reduction system: Selenium utilization and methionine sulfoxide reductase enzymes and their functions. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013;19:958–969. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao C., Hartke A., La Sorda M., Posteraro B., Laplace J.-M., Auffray Y., Sanguinetti M. Role of methionine sulfoxide reductases A and B of Enterococcus faecalis in oxidative stress and virulence. Infect. Immun. 2010;78:3889–3897. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00165-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saha S.S., Hashino M., Suzuki J., Uda A., Watanabe K., Shimizu T., Watarai M. Contribution of methionine sulfoxide reductase B (MsrB) to Francisella tularensis infection in mice. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2017;364:2. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnw260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moskovitz J., Rahman M.A., Strassman J., Yancey S.O., Kushner S.R., Brot N., Weissbach H. Escherichia coli peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase gene: Regulation of expression and role in protecting against oxidative damage. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:502–507. doi: 10.1128/JB.177.3.502-507.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moskovitz J., Poston J.M., Berlett B.S., Nosworthy N.J., Szczepanowski R., Stadtman E.R. Identification and characterization of a putative active site for peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase (MsrA) and its substrate stereospecificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:14167–14172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moskovitz J., Singh V.K., Requena J., Wilkinson B.J., Jayaswal R.K., Stadtman E.R. Purification and characterization of methionine sulfoxide reductases from mouse and Staphylococcus aureus and their substrate stereospecificity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;290:62–65. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moskovitz J., Berlett B.S., Poston J.M., Stadtman E.R. The yeast peptide-methionine sulfoxide reductase functions as an antioxidant in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:9585–9589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodrigo M.-J., Moskovitz J., Salamini F., Bartels D. Reverse genetic approaches in plants and yeast suggest a role for novel, evolutionarily conserved, selenoprotein-related genes in oxidative stress defense. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2002;267:613–621. doi: 10.1007/s00438-002-0692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delaye L., Becerra A., Orgel L., Lazcano A. Molecular evolution of peptide methionine sulfoxide reductases (MsrA and MsrB): On the early development of a mechanism that protects against oxidative damage. J. Mol. Evol. 2007;64:15–32. doi: 10.1007/s00239-005-0281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kryukov G.V., Kumar R.A., Koc A., Sun Z., Gladyshev V.N. Selenoprotein R is a zinc-containing stereo-specific methionine sulfoxide reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:4245–4250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072603099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geer L.Y., Domrachev M., Lipman D.J., Bryant S.H. CDART: Protein homology by domain architecture. Genome Res. 2002;12:1619–1623. doi: 10.1101/gr.278202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim Y.K., Shin Y.J., Lee W.H., Kim H.Y., Hwang K.Y. Structural and kinetic analysis of an MsrA–MsrB fusion protein from Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;72:699–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06680.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han A.-r., Kim M.-J., Kwak G.-H., Son J., Hwang K.Y., Kim H.-Y. Essential role of the linker region in the higher catalytic efficiency of a bifunctional MsrA–MsrB fusion protein. Biochemistry. 2016;55:5117–5127. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen B., Markillie L.M., Xiong Y., Mayer M.U., Squier T.C. Increased catalytic efficiency following gene fusion of bifunctional methionine sulfoxide reductase enzymes from Shewanella oneidensis. Biochemistry. 2007;46:14153–14161. doi: 10.1021/bi701151t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wizemann T.M., Moskovitz J., Pearce B.J., Cundell D., Arvidson C.G., So M., Weissbach H., Brot N., Masure H.R. Peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase contributes to the maintenance of adhesins in three major pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:7985–7990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowther W.T., Brot N., Weissbach H., Matthews B.W. Structure and mechanism of peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase, an “anti-oxidation” enzyme. Biochemistry. 2000;39:13307–13312. doi: 10.1021/bi0020269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowther W.T., Weissbach H., Etienne F., Brot N., Matthews B.W. The mirrored methionine sulfoxide reductases of Neisseria gonorrhoeae pilB. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:348–352. doi: 10.1038/nsb783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee E.H., Kwak G.-H., Kim M.-J., Kim H.-Y., Hwang K.Y. Structural analysis of 1-Cys type selenoprotein methionine sulfoxide reductase A. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014;545:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rouhier N., Kauffmann B., Tete-Favier F., Palladino P., Gans P., Branlant G., Jacquot J.-P., Boschi-Muller S. Functional and structural aspects of poplar cytosolic and plastidial type a methionine sulfoxide reductases. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:3367–3378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor A.B., Benglis Jr D.M., Dhandayuthapani S., Hart P.J. Structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis methionine sulfoxide reductase A in complex with protein-bound methionine. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:4119–4126. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.14.4119-4126.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranaivoson F.M., Neiers F., Kauffmann B., Boschi-Muller S., Branlant G., Favier F. Methionine sulfoxide reductase B displays a high level of flexibility. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;394:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alamuri P., Maier R.J. Methionine sulfoxide reductase in Helicobacter pylori: Interaction with methionine-rich proteins and stress-induced expression. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:5839–5850. doi: 10.1128/JB.00430-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levine R.L., Berlett B.S., Moskovitz J., Mosoni L., Stadtman E.R. Methionine residues may protect proteins from critical oxidative damage. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1999;107:323–332. doi: 10.1016/S0047-6374(98)00152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stadtman E.R., Moskovitz J., Berlett B.S., Levine R.L. Cyclic oxidation and reduction of protein methionine residues is an important antioxidant mechanism. Oxyg. Nitrogen Radic. Cell Inj. Dis. 2002;37:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradford M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276 doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minetti G., Balduini C., Brovelli A. Reduction of DABS-L-methionine-dl-sulfoxide by protein methionine sulfoxide reductase from polymorphonuclear leukocytes: Stereospecificity towards the l-sulfoxide. Ital. J. Biochem. 1994;43:273–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim H.-Y. Glutaredoxin serves as a reductant for methionine sulfoxide reductases with or without resolving cysteine. Acta Biochim. Biophys Sin. 2012;44:623–627. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gms038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim H.-Y., Kim J.-R. Thioredoxin as a reducing agent for mammalian methionine sulfoxide reductases B lacking resolving cysteine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;371:490–494. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vagin A., Teplyakov A. MOLREP: An automated program for molecular replacement. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1997;30:1022–1025. doi: 10.1107/S0021889897006766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Project C.C. The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liebschner D., Afonine P.V., Baker M.L., Bunkóczi G., Chen V.B., Croll T.I., Hintze B., Hung L.-W., Jain S., McCoy A.J., et al. Iterative model building, structure refinement and density modification with the PHENIX AutoBuild wizard. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2019;75:861–877. doi: 10.1107/S2059798319011471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams P.D., Afonine P.V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V.B., Davis I.W., Echols N., Headd J.J., Hung L.-W., Kapral G.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen V.B., Arendall W.B., Headd J.J., Keedy D.A., Immormino R.M., Kapral G.J., Murray L.W., Richardson J.S., Richardson D.C. MolProbity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brot N., Collet J.-F., Johnson L.C., Jönsson T.J., Weissbach H., Lowther W.T. The thioredoxin domain of Neisseria gonorrhoeae PilB can use electrons from DsbD to reduce downstream methionine sulfoxide reductases. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:32668–32675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604971200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The structure factor and coordinate file have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org, accessed on 11 March 2021) under accession code 7E43.