Abstract

The connection between pharmacists’ knowledge and practice on the provided information to patients about dermatoses and their treatment is insufficiently characterized. Furthermore, pharmacists’ contributions in counselling and in promoting adherence to topical treatment is not fully understood. This study has three main objectives. It aims to identify the knowledge and practices of pharmacists about dermatoses and their treatment, and to compare the perspective of pharmacists with that of patients regarding treatment information, with the future goal of establishing guidelines on the communication of dosage regimen instructions to dermatological patients and promotion of adherence to treatment, filling a gap. A cross-sectional, exploratory, and descriptive study was carried out. Based on experts’ prior knowledge and extensive collected literature information, two questionnaire protocols, one for pharmacists and another one for patients, were designed. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were carried out in relation to the pharmacists’ questionnaire for instrument validation. The results indicate that knowledge of pharmacists regarding dermatoses and their treatment is considered acceptable. Most of the pharmacists were reported to provide information to patients. Oppositely, patients reported not to have receive it. This is an important issue because pharmacists play a primary role in the management of several diseases. As non-adherence can be triggered by poor understanding of the dosing instructions, pharmacists’ communication practices play an important role in improving this hinderance. Results from this study identified pharmacist–patient communication gaps, so the development of guidelines to improve the transmission of clear dosage regimen instructions and knowledge about patient’s disease are of paramount importance. Training programs for continuous education of pharmacist should be implemented to solve the identified communication problems found in this study.

Keywords: community pharmacist, treatment adherence, disease management, pharmacists’ knowledge

1. Introduction

Dermatoses are pathologies of high prevalence, with mental co-morbidity for which cutaneous medications are often a first-line therapeutic option [1]. The clinical effectiveness of these drugs is conditioned by treatment adherence [2]. In addition to the importance of adherence in the patient’s health, non-adherence has a high economic impact, due to the overuse of healthcare resources [3]. Adherence is an area of growing concern in the treatment of chronic diseases, particularly skin diseases [4] and the World Health Organization (WHO) has considered it a priority area of activity [5]. Some of the factors that affect treatment adherence are specific to topical medications, such as the mechanical properties of the formulations [6] and the difficulty in establishing clear dosage instructions [7]. The lack of knowledge about the dose to be applied was recognized as a factor that negatively influences treatment adherence [8,9].

Health professionals have an important role in promoting treatment adherence [10]. The pharmacist is the health professional who has the best skills to guide, educate and instruct the patient on the correct use of medicines, clarifying doubts and favouring adherence and the clinical success of the prescribed treatment [11,12]. Young et al. [13] found that pharmacists did not routinely direct patients to medicine information websites and thought leaflets might worry patients about possible side effects. Aimaurai et al. [14] proposed that community pharmacists could offer a Medicines Use Review service to ensure the quality use of medicines in the community after recognizing the unmet needs of patients for information on medicine.

The knowledge of community pharmacists about the characteristics of chronic dermatoses and their therapeutic regimens is unknown, which may hinder their role as players in plans to promote adherence to dermatological therapy. The transmission of health information is most effective when its contents are specifically targeted at a person or population group and when the message is well delimited, highlighting the benefits and costs associated with behaviours and decision making [15].

This study aims to identify the knowledge of pharmacists about dermatoses and their treatment, and to compare the perspectives of pharmacists with those of patients regarding treatment information, with the future goal of establishing clear guidelines on the communication of dosage regimen instructions by healthcare professionals to dermatological patients and promote treatment adherence.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Procedures

This is a cross-sectional, exploratory, and descriptive study. Two questionnaire protocols were designed by the authors: one for the pharmacists and another one for the patients. For the generation of items included in the questionnaires, an expertise panel, comprised by 6 pharmacists, 3 psychologists and 1 dermatologist, was set, and the most prevalent dermatoses in Portugal were considered. The pool of items to include was decided, based on the panel professional experience and theoretical knowledge, also relying on an extensive systematic review of the literature and qualitative patients focus interviews. The counselling background is considered, based on the extensive experience of the panel. After pre-testing and validation, final versions of the questionnaires were then obtained. The participants, pharmacists and patients, covering the entire geographical mainland Portugal area, from the north to the south.

The patients and pharmacists’ protocols were applied in self-administered form through online procedures, in compliance with ethical standards and disclosed through the Portuguese Psoriasis Patient Association (PSO-Portugal) [16] and the Portuguese Pharmaceutical Society (Ordem dos Farmacêuticos—OF) [17], respectively, between 2018 and 2019. The eligibility criteria for patients included to be 18 years of age or older; to have a clinical diagnosis of psoriasis; to belong to PSO-Portugal and/or to the OF. The eligibility criteria for pharmacists were to be a pharmacist, recognized by the OF [17], and work in community pharmacies. All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee of Instituto Universitário de Ciências da Saúde (IUCS/CESPU) [18], Portugal, no specific reference assigned, date acting as reference identification (17 March 2017), approved and made available online, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was also approved by the Portuguese Data Protection Authority (Comissão Nacional de Proteção de Dados—CNPD) [19], Portugal, date acting as reference identification (26 September 2017). Informed consent was made available and obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Pharmacists

The sample consists of 149 pharmacists working in community pharmacy, mostly female (83.2%), with a mean age of 37.99 years (SD = 9.90; Min 24–Max 72) and with a mean of education graduation of 12.89 years (SD = 9.45; Min 1–Max 28).

2.2.2. Patients

The sample of patients is composed of 44 participants, of which 67.4% are female. The mean age is 50.65 years old (SD = 16.075; Min 9–Max 76); 47.7% of the sample has an academic degree and 31.8% has only secondary education.

2.3. Instruments

The pharmacists’ protocol included a sociodemographic questionnaire, assessing age, gender and years from graduation and another questionnaire, the Dermatologic Topical Treatment Knowledge (DTTK) to assess the pharmacists’ knowledge regarding dermatoses and their treatment and treatment adherence (Table 1). The first ten questions in this questionnaire aimed to assess the knowledge of pharmacists in relation to dermatoses and their treatment (subscale 1) and the remaining questions assessed pharmacists’ knowledge in relation to dosage regimen instructions and treatment adherence (subscale 2). It was also possible to obtain a total score value. All questions were designed in such a way that each question corresponded to several answering options, which were assigned a value as it approached more or distanced itself from the right answer that was indicative of knowledge. The higher the score, the greater the knowledge of each pharmacist in relation to the topic under consideration.

Table 1.

Pharmacists’ answers, total and subscales description (N = 230).

| Questions | Theoretical Min–Max | Min | Max | M | SD | Skw | Krt | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 Prevalent chronic dermatoses | 0–13 | 4 | 10 | 8.50 | 1.81 | −1.15 | −0.25 | |

| Q2 Factors of chronic dermatoses | 0–14 | 2 | 14 | 10.30 | 2.63 | −0.24 | −0.04 | |

| Q3 Typical psoriasis lesions | 0–13 | 8 | 12 | 11.07 | 1.53 | −1.37 | 0.14 | |

| Q4 Typical atopic dermatitis lesions | 0–13 | 7 | 12 | 9.77 | 1.89 | 0.15 | −1.88 | |

| Q5 Typical seborrheic dermatitis lesions | 0–14 | 6 | 14 | 11.97 | 2.45 | −0.79 | −0.38 | |

| Q6 Typical acne lesions | 0–12 | 2 | 11 | 9.22 | 1.57 | −1.84 | 2.28 | |

| Q7 Prescribed medicines for psoriasis | 0–14 | 7 | 12 | 10.96 | 1.24 | −1.72 | 2.16 | |

| Q8 Prescribed medicines for atopic dermatitis | 0–14 | 2 | 10 | 8.37 | 1.54 | −1.04 | 0.14 | |

| Q9 Prescribed medicines for seborrheic dermatitis | 0–15 | 4 | 12 | 10.36 | 1.83 | −1.25 | 0.92 | |

| Q10 Prescribed medicines for acne | 0–16 | 4 | 12 | 11.34 | 1.50 | −2.12 | 3.41 | |

| Q11 Factors adherence chronic dermatoses | 0–12 | 1 | 10 | 7.42 | 1.63 | −1.77 | 2.54 | |

| Q12 Appropriate instructions of medicines | 0–9 | 0 | 8 | 5.37 | 1.84 | −0.35 | −0.50 | |

| Q13 Instruction duration corticosteroids | 0–2 | 0 | 2 | 1.81 | 0.50 | −2.63 | 5.99 | |

| Q14 Instruction duration immunomodulators | 0–2 | 0 | 2 | 1.19 | 0.91 | −0.39 | −1.67 | |

| Q15 Instruction duration anti-infectious | 0–2 | 0 | 2 | 1.59 | 0.72 | −1.43 | 0.43 | |

| Q16 How to apply the medicine | 0–2 | 0 | 2 | 1.63 | 0.72 | −1.60 | 0.84 | |

| Q17 How often apply cutaneous medicines | 0–2 | 0 | 2 | 1.58 | 0.76 | −1.43 | 0.26 | |

| Q18 Indications of clear and precise dosing | 0–10 | 4 | 10 | 8.97 | 2.22 | −1.75 | 1.14 | |

| Q19 Dosing instructions depend on... | 0–10 | 3 | 9 | 5.98 | 1.97 | −0.23 | −1.68 | |

| Q20 Dimension of adherence to topical treatment | 0–10 | 4 | 8 | 6.79 | 1.67 | −0.85 | −1.02 | |

| Q21 Increasing adherence to topical treatment | 0–2 | 0 | 2 | 1.41 | 0.75 | −0.85 | −0.74 | |

| Total | 0–201 | 96 | 168 | 145.59 | 12.05 | −1.31 | 2.85 | 0.65 |

| Dermatoses & treatment | 0–138 | 74 | 115 | 101.85 | 7.36 | −0.96 | 1.50 | 0.41 |

| Dosage instructions & adherence | 0–63 | 21 | 55 | 43.74 | 7.77 | −1.24 | 1.06 | 0.72 |

Min = Minimum; Max = Maximum; M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation; Skw = Skewness; Krt = Kurtosis; α = Cronbach Alfa.

The questionnaire started asking about the most prevalent chronic dermatoses in Portugal. The second question addresses the factors related to prevalence of chronic dermatoses. A group of 4 questions assesses the most characteristic lesions of psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis and acne. Another group of 4 questions measures the knowledge about the most prescribed pharmacotherapeutic groups for the treatment of psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis and acne. A question measures the information about the factors that influence adherence to skin treatment of chronic dermatoses. Another question assesses the most appropriate instructions to explain the dose of topical medicine. A group of 3 questions included the assessment of the behaviour to instruct the patient about the duration of corticosteroid, immunomodulators and anti-infectious topical treatment. The next 2 questions rely on asking the pharmacist if they instruct the patient on the mode and the frequency of application of topical medicines. The two followed questions address the indication of clear and precise dosage regimen instructions for topical treatment and the factors that influence it. The last 2 questions are related to the prevalence of adherence to topical treatment of chronic dermatoses and the perception of the importance of pharmaceutical intervention in the improvement of the disease. The patients’ protocol also included a sociodemographic questionnaire, assessing gender, age and education and a questionnaire regarding the interaction with pharmacists.

2.4. Data Analyses

The data were analysed using the Statistical Program for Social Sciences SPSS IBM, version 25 [20]. Descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation, was used to characterize the sample and the pharmacists’ and patients’ responses. Kurtosis and skewness values were calculated to assess the normality distribution of the sample. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to assess the instrument’s reliability. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were carried out in relation to the pharmacists’ questionnaire for instrument validation.

3. Results

3.1. Pharmacists

Table 1 presents the descriptive values of the pharmacists’ responses, as well as the Cronbach’s alpha value for all items and for the two subscales of the questionnaire. The skewness and kurtosis values are below the limits established by Kline [21], respectively 3 and 10, suggesting the normal distribution of responses to the items. The value of Cronbach’s alpha for the total of the questionnaire is at the limit of the acceptable (0.70) [22] as well as the alpha of the dosage regimen instructions and adherence subscale. According to Hair et al. [22], the dermatoses and treatments subscale has an unacceptable Cronbach’s alpha value (Table 1).

Regarding the pharmacists’ answers, the three most prevalent chronic dermatoses in Portugal were atopic dermatitis, psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis, and the prevalence of chronic dermatoses varies mainly with genetic factors, environmental factors, age and lifestyle. The most characteristic lesions of psoriasis were desquamative papules/plaques followed by erythema. Of atopic dermatitis are the erythema and desquamative papules/plaques, of seborrheic dermatitis are the desquamative papules/plaques and erythema, and of acne are the comedones and pustules. Participants revealed that corticosteroids are the most prescribed pharmacotherapeutic group for the treatment of psoriasis, atopic dermatitis and seborrheic dermatitis. Antibacterials are the most prescribed pharmacotherapeutic group for the treatment of acne. Participants recognized that the severity of the disease and the patient’s socioeconomic conditions are the factors that most influence the treatment adherence, an important outcome. They referred that apply in thin layer was the most appropriate instruction. Most pharmacists always instruct the patient about the duration of corticosteroid skin treatment and its associations, of skin treatment with immunomodulators and of anti-infectious skin treatment. Half of the sample report to always instruct the patient on how to apply the medicine and on how often to apply topical medicines. Almost all participants considered that the indication of clear and precise dosing instructions for dermatological skin treatments increases the effectiveness of skin drug treatment, increasing the treatment adherence with topical medicines and allowing to minimize the adverse effects of skin medications. Most of the participants considered that the indication of dosing instructions depends on the type of treatment. Participants thought adherence to topical treatment of chronic dermatoses is mostly between 50 and 69%. One third of the sample stated that adherence to topical treatment of chronic dermatoses can be increased with pharmaceutical intervention (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of pharmacists’ answers.

| Questions | Pharmacists’ Answers | % |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 In your opinion, which are the three most prevalent chronic dermatoses in Portugal? | Dermatitis | 84.3 |

| Psoriasis | 67.0 | |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | 58.7 | |

| Acne | 56.5 | |

| Androgenic Alopecia | 8.7 | |

| Scabies | 2.6 | |

| Q2 In your opinion, the prevalence of chronic dermatoses varies mainly with (tick the three answers you consider most relevant): | Genetic factors | 87.4 |

| Environmental factors | 65.2 | |

| Age | 59.1 | |

| Lifestyle | 53.9 | |

| Gender | 17.4 | |

| Socioeconomic factors | 13.9 | |

| Educational level | 1.3 | |

| Q3 In your opinion, the most characteristic lesions of psoriasis are (tick the two answers you consider most relevant): | Desquamative papules/plaques | 97.4 |

| Erythema | 67.4 | |

| Pustules | 15.2 | |

| Hyperpigmentation | 11.3 | |

| Ulcers | 6.1 | |

| Blisters | 1.3 | |

| Comedones | 0.4 | |

| Q4 In your opinion, the most characteristic lesions of atopic dermatitis are (tick the two answers you consider most relevant): | Erythema | 94.8 |

| Desquamative papules/plaques | 77.0 | |

| Pustules | 20.0 | |

| Ulcers | 15.2 | |

| Comedones | 12.6 | |

| Hyperpigmentation | 6.1 | |

| Blisters | 6.1 | |

| Q5 In your opinion, the most characteristic lesions of seborrheic dermatitis are (tick the two answers you consider most relevant): | Desquamative papules/plaques | 77.0 |

| Erythema | 70.4 | |

| Pustules | 20.0 | |

| Comedones | 12.6 | |

| Hyperpigmentation | 6.1 | |

| Blisters | 6.1 | |

| Ulcers | 3.9 | |

| Q6 In your opinion, the most characteristic lesions of acne are (tick the two answers you consider most relevant): | Comedones | 95.2 |

| Pustules | 77.4 | |

| Blisters | 8.3 | |

| Erythema | 5.7 | |

| Ulcers | 4.8 | |

| Hyperpigmentation | 3.0 | |

| Desquamative papules/plaques | 3.0 | |

| Q7 In your opinion, what are the most prescribed pharmacotherapeutic groups for the treatment of psoriasis (mark two answers you consider most relevant): | Corticosteroids | 86.5 |

| Keratolytics | 43.5 | |

| Vitamin D analogues | 32.6 | |

| Immunomodulators | 23.5 | |

| Retinoids | 7.8 | |

| Antibacterials | 1.7 | |

| Antifungals | 0.4 | |

| Q8 In your opinion, what are the most prescribed pharmacotherapeutic groups for the treatment of atopic dermatitis (marked two answers you consider most relevant): | Corticosteroids | 95.2 |

| Immunomodulators | 35.2 | |

| Antibacterials | 20.0 | |

| Keratolytics | 13.9 | |

| Retinoids | 10.9 | |

| Antifungals | 9,6 | |

| Vitamin D analogues | 8.3 | |

| Antivirals | 0.4 | |

| Q9 In your opinion, what are the most prescribed pharmacotherapeutic groups for the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis (marked two answers you consider most relevant): | Corticosteroids | 63.9 |

| Antifungals | 53.5 | |

| Keratolytics | 47.8 | |

| Antibacterials | 13.5 | |

| Retinoids | 7.0 | |

| Immunomodulators | 4.3 | |

| Vitamin D analogues | 2.6 | |

| Q10 In your opinion, what are the most prescribed pharmacotherapeutic groups for the treatment of acne (marked two answers you consider most relevant): | Antibacterials | 86.1 |

| Retinoids | 72.2 | |

| Keratolytics | 19.6 | |

| Corticosteroids | 7.4 | |

| Antifungals | 3.0 | |

| Vitamin d analogues | 3.0 | |

| Immunomodulators | 1.7 | |

| Q11 In your opinion, the factors that influence adherence to skin treatment of chronic dermatoses are (tick the three answers you consider most relevant)” | Severity of the disease | 84.8 |

| Socioeconomic conditions | 84.3 | |

| Vehicle/base of the medicine | 45.2 | |

| The season | 30.4 | |

| The knowledge of dosage | 25.7 | |

| The skin type | 9.1 | |

| The medicine strength | 5.7 | |

| Q12 In accordance with your professional practice, refer to the most appropriate instructions to explain to the patient the dose of topical medicine to be applied (tick the two answers you consider most relevant)” | Apply in thin layer | 85.2 |

| Apply an amount equivalent to the “fingertip unit” to an area approximately one palm | 46.1 | |

| Apply a pea-sized amount to each lesion | 40 | |

| Apply generously to the area to be treated | 8.7 | |

| Apply an amount equivalent to the “fingertip unit” to an approximate area of two palms | 8.7 | |

| Q13 According to your professional practice, do you usually instruct the patient about the duration of corticosteroid skin treatment and its associations? | Always | 63.9 |

| Almost always | 16.5 | |

| Several times | 6.1 | |

| Sometimes | 3.5 | |

| Rarely | 0.4 | |

| Never | 0.4 | |

| Q14 According to your professional practice, do you usually instruct the patient about the duration of skin treatment with immunomodulators? | Always | 35.7 |

| Almost always | 21.7 | |

| Several times | 8.7 | |

| Sometimes | 6.5 | |

| Rarely | 15.7 | |

| Never | 8.3 | |

| Q15 According to your professional practice, do you usually instruct the patient about the duration of anti-infectious skin treatment? | Always | 53.4 |

| Almost always | 18.3 | |

| Several times | 9.1 | |

| Sometimes | 4.3 | |

| Rarely | 2.2 | |

| Never | 1.7 | |

| Q16 According to your professional practice, do you usually instruct the patient on how to apply the medicine? | Always | 50.0 |

| Almost always | 27.0 | |

| Several times | 6.1 | |

| Sometimes | 2.6 | |

| Rarely | 0.9 | |

| Never | 2.2 | |

| Q17 According to your professional practice, do you usually instruct the patient about how often to apply cutaneous medicines? | Always | 53.5 |

| Almost always | 21.7 | |

| Several times | 5.2 | |

| Sometimes | 2.6 | |

| Rarely | 0.9 | |

| Never | 1.7 | |

| Q18 In your opinion, the indication of clear and precise dosing instructions for dermatological skin treatments (please tick the three answers you consider most relevant) is: | Increases the effectiveness of skin drug treatment | 84.3 |

| Contributes to increased treatment adherence with topical medicines | 83.5 | |

| Allows to minimize the adverse effects of skin medications | 82.6 | |

| Systemic treatments as these (skin application) are very safe | 0.9 | |

| Systemic treatments as these (skin application) are ineffective | 0.9 | |

| Q19 In your opinion, the indication of dosing instructions (frequency, duration and dose of the medicinal product to be administered) depends on (tick the two answers you consider most relevant): | The participants choose of the type of treatment | 62.6 |

| The type of dermatosis | 44.8 | |

| The treatment complexity | 21.3 | |

| When the medicine is first used | 17.0 | |

| The existence of several affected anatomical zones | 14.8 | |

| The type of base/vehicle | 9.6 | |

| Q20 In your opinion, adherence to topical treatment of chronic dermatoses is: | Greater than 90% | 1.7 |

| Between 70–90% | 17.4 | |

| Between 50–69% | 43.5 | |

| Between 30–49% | 18.7 | |

| Less than 30% | 3.5 | |

| Q21 According to your professional practice, can adherence to topical treatment of chronic dermatoses be increased with pharmaceutical intervention? | Always | 31.3 |

| Almost always | 26.1 | |

| Several times | 20.4 | |

| Sometimes | 6.1 | |

| Rarely | 0.9 |

The answers considered correct were scored with 2 points and the incorrect answers with zero. The acceptable responses were scored with 1 point, thus allowing to establish a score that assesses the knowledge of pharmacists. Acceptable knowledge has been found, i.e., the total score was higher than 50% of maximum value (e.g., total results vary from 0 to 201 and thus 100.5 score was considered as acceptable). The obtained results show that pharmacists have more than acceptable knowledge regarding dermatoses and their treatment and dosage regimen instructions and treatment adherence (145.59 corresponding to 72.4%).

The factorability of the 21 pharmacists’ questionnaire items was examined. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin [23] measure of sampling adequacy was 0.80 (above the recommended value of 0.6), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity [24] was significant (χ2 (210) = 1217.92, p < 0.000). Finally, the communalities were all above 0.40, confirming that each item shared some common variance with other items. Thus, EFA was considered to be suitable with all 21 items (Table 3).

Table 3.

Exploratory factorial analysis (EFA).

| Questions | Communalities | Component Matrix | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 Prevalent chronic dermatoses | 0.640 | 0.182 | 0.113 |

| Q2 Factors of chronic dermatoses | 0.481 | 0.225 | 0.150 |

| Q3 Typical psoriasis lesions | 0.479 | 0.080 | 0.412 |

| Q4 Typical atopic dermatitis lesions | 0.594 | −0.063 | 0.394 |

| Q5 Typical seborrheic dermatitis lesions | 0.635 | −0.039 | 0.442 |

| Q6 Typical acne lesions | 0.412 | −0.044 | 0.558 |

| Q7 Prescribed medicines for psoriasis | 0.653 | 0.169 | 0.342 |

| Q8 Prescribed medicines for atopic dermatitis | 0.625 | −0.041 | 0.411 |

| Q9 Prescribed medicines for seborrheic dermatitis | 0.654 | 0.093 | 0.306 |

| Q10 Prescribed medicines for acne | 0.506 | 0.168 | 0.576 |

| Q11 Factors adherence chronic dermatoses | 0.407 | 0.341 | 0.375 |

| Q12 Appropriate instructions of medicines | 0.494 | 0.089 | 0.218 |

| Q13 Instruction duration corticosteroids | 0.652 | 0.610 | 0.313 |

| Q14 Instruction duration immunomodulators | 0.553 | 0.517 | 0.056 |

| Q15 Instruction duration anti-infectious | 0.732 | 0.758 | 0.169 |

| Q16 How to apply the medicine | 0.723 | 0.831 | 0.058 |

| Q17 How often apply cutaneous medicines | 0.810 | 0.869 | −0.021 |

| Q18 Indications of clear and precise dosing | 0.790 | 0.833 | −0.015 |

| Q19 Dosing instructions depend on… | 0.452 | 0.438 | −0.065 |

| Q20 Dimension of adherence to topical treatment | 0.545 | 0.230 | 0.083 |

| Q21 Increasing adherence to topical treatment | 0.697 | 0.767 | −0.091 |

Principal components analysis, with varimax rotation, was used with prior determination of two factors. Eigenvalues indicated that the first two factors explained 22 and 8% of the variance, respectively. A total of four items were removed because they did not contribute to a simple factor structure and failed to meet a minimum criterion of having a primary factor loading of 0.4 or above, and no cross-loading of 0.3 or above (items 1, 2, 11 and 12). A new analysis of principal components was carried out, now with 17 items and prior determination of two factors. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.82 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2 (120) = 1089.80, p < 0.000). Eigenvalues indicated that the first two factors explained 26 and 10% of the variance, respectively. However, items 9 and 20 were removed because they did not contribute to a simple factor structure and failed to meet a minimum criterion of having a primary factor loading of 0.4 or above. The last analysis of principal components was carried out, now with 15 items and prior determination of two factors. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.83 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2 (105) = 1051.26, p < 0.000). Eigenvalues indicated that the first two factors explained 29 and 11% of the variance, respectively, with a total of 40% (Table 4). Cronbach’s alpha values rose slightly with pharmacist’s knowledge and adherence subscale, obtaining 0.77, and dermatoses and treatment subscale, obtaining 0.44 and total 0.65.

Table 4.

Final exploratory factorial analysis (EFA).

| Questions | Component Matrix | |

|---|---|---|

| Q3 Typical psoriasis lesions | 0.081 | 0.447 |

| Q4 Typical atopic dermatitis lesions | −0.05 | 0.398 |

| Q5 Typical seborrheic dermatitis lesions | −0.03 | 0.369 |

| Q6 Typical acne lesions | −0.032 | 0.611 |

| Q7 Prescribed medicines for psoriasis | 0.174 | 0.355 |

| Q8 Prescribed medicines for atopic dermatitis | −0.047 | 0.471 |

| Q10 Prescribed medicines for acne | 0.179 | 0.635 |

| Q13 Instruction duration corticosteroids | 0.612 | 0.274 |

| Q14 Instruction duration immunomodulators | 0.529 | 0.053 |

| Q15 Instruction duration anti-infectious | 0.775 | 0.210 |

| Q16 How to apply the medicine | 0.834 | 0.084 |

| Q17 How often apply cutaneous medicines | 0.872 | 0.015 |

| Q18 Indications of clear and precise dosing | 0.829 | −0.035 |

| Q19 Dosing instructions depend on… | 0.437 | −0.086 |

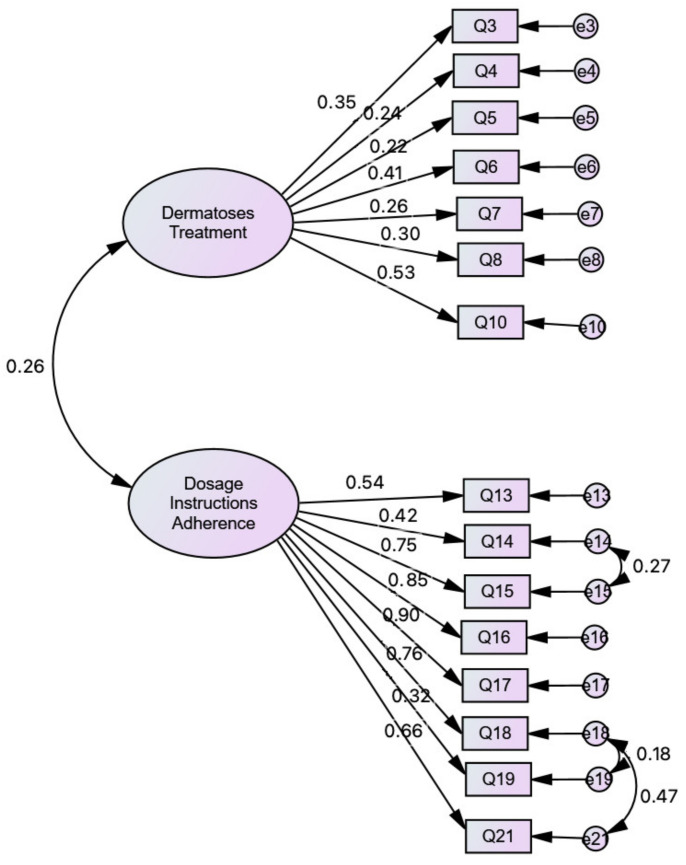

CFA was used to test whether the pharmacists’ questionnaire measures are consistent with the researchers’ understanding of the nature of that construct. As presented in Figure 1, the model shows a good fit. According to Marôco [25], the sample size is within the required parameters (n = 200–400) regarding the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method in Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). There is no missing data. To verify the existence of outliers, the Mahalanobis squared distance [26] (p1 and p2 < 0.001) was used [21]. To test the items’ multicollinearity, Spearman coefficients were calculated, according to a reference value of 0.80 [27]. To assess the goodness-of-fit of the model to the global correlation frame, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), Parsimonious Fit Indices representing adjustments, values greater than 0.9 are indicative of a good fit. Values of χ2/df = ~2 and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) [28] < 0.08 were considered, indicating a good model fit. The refinement of the questionnaire original model was performed from the values of the Modification Indices (MI), for the Lagrange multipliers (LM) [29], considering that trajectories and/or correlations with LM > 11 (p < 0.001) indicate significant variation in the quality of the model [25].

Figure 1.

Model Fit of the Pharmacists’ Knowledge Questionnaire in a sample of pharmacists whose workplace is the community pharmacy: χ2 = 154.008; df = 86; χ2/df = 1.791; CFI = 0.930; TLI = 0.915; RMSEA = 0.059; PCLOSE = 0.163.

3.2. Patients

Most of the sample of patients (77.8%) is undergoing treatment for psoriasis and the remaining participants are being treated for acne, rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis. Most (79.5%) are undergoing treatment directed by a dermatologist. The others do so, advised by their General Physician and/or pharmacist. A significant part of the sample (36.4%) was consulted and medicated in a private physician’s office, and another part (34.1%) in a public hospital, while the rest were consulted in private hospitals and health centres. Only 25.6% of the sample is undergoing the dermatological treatment for the first time, and 74.4% of the sample is undergoing continued treatment.

Only 11.4% of the sample reported receiving oral information at the pharmacy about the dose of the medication to use. In total, 18.2% reported to have received information at the pharmacy about the duration of treatment and the number of times needed to apply the medicine; 15.9% reported having had information at the pharmacy about the mode of application of the medicine.

4. Discussion

According to the results obtained, regarding pharmacists, atopic dermatitis has been identified as the most prevalent chronic dermatosis in Portugal, in line with the Oliveira and Torres [30] study, erythema being its most frequent clinical manifestation, as stated by Siegfried and Hebert [31]. Corticosteroids are reported as the most prescribed drugs for this disease, corroborating the Pona et al. [32] study. Psoriasis is the second most dermatosis prevalent, the most frequent lesions being desquamative papules/plaques; Corticosteroids are also the most prescribed drugs for psoriasis treatment, which is in accordance with Dolz-Pérez and colleagues [33] study. In this study, seborrheic dermatitis and acne were identified, respectively, as the third and fourth most common dermatoses in Portugal.

Desquamative papules/plaques and erythema have been pointed out as the most frequent characteristics of seborrheic dermatitis, and comedones considered to be the most frequent characteristic of acne, in line with Borda, Perper and Keri [34] study. Again, corticosteroids are the most prescribed drugs for seborrheic dermatitis, and antibacterials the most prescribed drugs for acne, corroborating Borda and colleagues [34] and Brown [35] studies, respectively.

Genetic factors are primarily responsible for the prevalence of chronic dermatoses [36]. The participants in this study recognized that the severity of the disease and the patient’s socioeconomic conditions are the factors that most influence the treatment adherence in accordance with reported by Eicher et al. [37]. Pharmaceutics believe that the most appropriate instructions to explain to the patient the dose of topical medicine to be applied is apply in thin layer, corroborating Goman findings [38]. Most of the participants (>67.4%) stated that they always/almost always instruct the patient about (a) the duration of corticosteroid skin treatment and its associations; (b) the duration of anti-infectious skin treatment; (c) how to apply the medicine; (d) how often to apply cutaneous medicines, in accordance with Tucker and Stewart [39] results. The participants considered that the indication of clear and precise dosage regimen instructions for dermatological skin treatments are important because contributes to increase adherence and effectiveness of topical treatment and to minimize the adverse effects of topical medicines, in line with Yamaura [40] observations. According to pharmacists, the indication of dosage regimen instructions, i.e., frequency, duration and dose of the medicinal product to be administered, mainly depends on the type of treatment, e.g., corticotherapy, antibiotic therapy, as Teixeira and colleagues [41] also stated. Although pharmacist knowledge is acceptable, the results obtained highlight the need to promote the communication of this information to the patients, aiming to improve adherence and clinical outcome of treatment. For this purpose, training programs and guidelines adapted to pharmacists’ needs should be developed and implemented as part of continuous education of these health professionals.

The knowledge of pharmacists regarding dermatoses and their treatment is considered acceptable. This is an important subject because community pharmacists play a primary role in the management of several diseases [42,43] since, these health professionals, are easily accessible and have knowledge to clarify dosing instructions and the opportunity to emphasize the importance of treatment adherence in compliance with the therapeutic regime for the effectiveness of treatment. Different studies demonstrate the relevance of pharmacist interventions in the management of different dermatoses. Aishwarya et al. [44] reported that medication adherence among psoriasis patients was improved after pharmacist education and counselling intervention. Tucker and Stewart et al. [39] stated the enhancement of patients’ psoriasis knowledge, minimizing the severity of the disease and bettering quality of life, following education intervention delivered by community pharmacist.

Regarding patients, only a quarter of the sample reported receiving oral information at the pharmacy about the dose of medication to use. Almost a third of the sample have received information at the pharmacy about the duration of treatment and the number of times to apply the medicine and less than a third reported having had information at the pharmacy about the mode of its application.

Discrepancies were found between what pharmacists claim to report to patients and what patients claim to have been reported by pharmacists, which is in accordance with our previous study, since most patients announced that they did not receive the reinforcement of the dosing instructions when they fill the prescriptions at the pharmacy [45].

As Tulsky and colleagues [46] stated, poor communication by healthcare professionals contributes to physical and psychological suffering in patients. Despite this, pharmacists reported instructing patients regarding topical dosage regimens and hold acceptable knowledge of this issue, which is in line with, Johnson, Moser, and Garwood [47], who stated that the majority of patients reported that they did not receive that instructions, suggesting the need to outline strategies to improve communication between pharmacist and patients, in order to promote adherence and clinical outcome of the treatment.

5. Conclusions

It is recognized that the link between the knowledge and practice of pharmacists in what concerns the information given to patients about dermatoses and corresponding treatment is not fully characterized. It is also recognized that the pharmacists’ contribution in counselling and in adherence promotion to topical treatment is not fully understood. Three main objectives were then considered: identification of the knowledge of pharmacists about dermatoses and their treatment; comparison of the perspective of pharmacists with that of patients regarding treatment information; future goal of establishing clear guidelines on the communication of dosage regimen instructions by healthcare professionals to dermatological patients and promote treatment adherence.

An expertise panel, including pharmacists, psychologists and dermatologists was set. Based on their expertise and extensive literature review, two questionnaire protocols, orientated to pharmacists and patients, were designed, after initial pre-testing and validation. EFA and CFA were applied to the results.

The knowledge of pharmacists regarding dermatoses and their treatment is considered acceptable, which is an important result as pharmaceuticals play a primary role in the management of several diseases. Discrepancies were found regarding the communication of instructions by pharmacists, since most pharmacists reported to provide information to patients but only a low percentage of patients reported to have received it. Concerning practical implications, most of the skin diseases can be effectively treated with topical medicines. However, non-adherence to topical treatment, caused by poor understanding of the dosing instructions, leads to clinical ineffectiveness.

This study thus assumes particular importance because it allows one to identify communication gaps between pharmacists and patients, with negative implications in the adherence and clinical outcome of topical treatments. Future studies focused on the establishment of guidelines to improve the communication of dosage regimen instructions by pharmacists to dermatological patients, could overcome the problems recognized in this study. Furthermore, training programs for the continuous education of the pharmacist should be implemented to solve the identified problems found in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank to Portuguese Psoriasis Patient Association (PSO-Portugal) for the contribution and Portuguese Pharmaceutical Society on data collection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T., M.T., I.F.A. and V.A.; Data curation, A.T., M.T., R.C., I.F.A. and V.A.; Formal analysis, A.T., M.T., R.C., I.F.A. and V.A.; Funding acquisition, A.T., M.T. and V.A.; Investigation, A.T., M.T., V.V., R.C., I.F.A. and V.A.; Methodology, A.T., M.T., M.T.H., M.F.B., I.F.A. and V.A.; Project administration, A.T., M.T. and V.A.; Resources, A.T., M.T., R.C., I.F.A. and V.A.; Software, A.T., M.T., I.F.A. and V.A.; Supervision, A.T., M.T., I.F.A. and V.A.; Validation, A.T., M.T., M.T.H., V.V., R.C., M.F.B., I.F.A., D.G.V. and V.A.; Visualization, A.T., M.T., I.F.A., D.G.V., M.A.P.D. and V.A.; Writing—original draft, A.T., M.T., M.T.H., V.V., R.C., M.F.B., I.F.A. and V.A.; Writing—review and editing, A.T., M.T., I.F.A., D.G.V., H.F.P.eS., M.A.P.D. and V.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by CESPU—Cooperativa de Ensino Superior Politécnico e Universitário—under the Grants “POSOL_DERM_CESPU-2016”, “PHARM4ADHER_CESPU_2017” and “INSIGHT4ADHERE-PFT-IINFACTS-2019”. This work was supported by the Applied Molecular Biosciences Unit—UCIBIO, which is financed by national funds from FCT (UIDP/04378/2020 and UIDB/04378/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Instituto Universitário de Ciências da Saúde (IUCS/CESPU), Portugal, no specific reference assigned, date acting as reference identification (17 March 2017). The study was also approved by the Portuguese Data Protection Authority (Comissão Nacional de Proteção de Dados—CNPD), Portugal, date acting as reference identification (26 September 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

As part of consenting to the study, survey respondents were assured that raw data would remain confidential and would not be shared. Descriptive data may be available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Menter A., Gottlieb A., Feldman S.R., Van Voorhees A.S., Leonardi C.L., Gordon K.B., Lebwohl M., Koo J.Y.M., Elmets C.A., Korman N.J., et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008;58:826–850. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devaux S., Castela A., Archier E., Gallini A., Joly P., Misery L., Aractingi S., Aubin F., Bachelez H., Cribier B., et al. Adherence to topical treatment in psoriasis: A systematic literature review. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2012;26(Suppl. S3):61–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleemput I., Kesteloot K., DeGeest S. A review of the literature on the economics of noncompliance. Room for methodological improvement. Health Policy. 2002;59:65–94. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(01)00178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahn C.S., Culp L., Huang W.W., Davis S.A., Feldman S.R. Adherence in dermatology. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2017;28:94–103. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2016.1181256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WC C. International Encyclopedia of Public Health. Academic Press; Cambridge, UK: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teixeira A., Vasconcelos V., Teixeira M., Almeida V., Azevedo R., Torres T., Lobo J.M.S., Costa P.C., Almeida I.F. Mechanical Properties of Topical Anti-Psoriatic Medicines: Implications for Patient Satisfaction with Treatment. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2019;20:36. doi: 10.1208/s12249-018-1246-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pouplard C., Gourraud P.-A., Meyer N., Livideanu C.B., Lahfa M., Mazereeuw-Hautier J., Le Jeunne P., Sabatini A.-L., Paul C. Are we giving patients enough information on how to use topical treatments? Analysis of 767 prescriptions in psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2011;165:1332–1336. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldman S., Cline A., Pona A., Kolli S. Treatment Adherence in Dermatology. Springer International Publishing; Cham, Switzerland: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savary J., Ortonne J.P., Aractingi S. The right dose in the right place: An overview of current prescription, instruction and application modalities for topical psoriasis treatments. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2005;19(Suppl. S3):14–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabbro S.K., Mostow E.N., Helms S.E., Kasmer R., Brodell R.T. The pharmacist role in dermatologic care. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2014;6:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2013.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan E.C.K., Stewart K., Elliott R.A., George J. Pharmacist consultations in general practice clinics: The Pharmacists in Practice Study (PIPS) Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2014;10:623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farrell B., Ward N., Dore N., Russell G., Geneau R., Evans S. Working in interprofessional primary health care teams: What do pharmacists do? Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2013;9:288–301. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young A., Tordoff J., Leitch S., Smith A. Patient-focused medicines information: General practitioners’ and pharmacists’ views on websites and leaflets. Health Educ. J. 2018;78:340–351. doi: 10.1177/0017896918811373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aimaurai S., Jumpated A., Krass I., Dhippayom T. Patient opinions on medicine-use review: Exploring an expanding role of community pharmacists. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:751–760. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S132054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kickbusch I., Pelikan M., Apfel F., Tsouros A. Health Literacy. WHO Regional Office for Europe; Copenhagen, Denmark: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Associação Portuguesa de Psoríase PSO Portugal. [(accessed on 1 February 2021)]; Available online: https://psoportugal.pt/

- 17.Ordem dos Farmacêuticos Ordem dos Farmacêuticos Portugueses [Portuguese Order of Pharmacists] [(accessed on 19 November 2020)]; Available online: https://www.ordemfarmaceuticos.pt/pt/

- 18.CESPU Instituto Universitário de Ciências da Saúde [Universitary Institute of Health Sciences] [(accessed on 19 November 2020)]; Available online: https://www.cespu.pt/en/

- 19.Comissão Nacional de Protecção de Dados Comissão Nacional de Protecção de Dados [Data Protection National Commission] [(accessed on 19 November 2020)]; Available online: https://www.cnpd.pt/english/index_en.htm.

- 20.IBM Corporation . IBM Corporation Released IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. IBM Corporation; Armonk, NY, USA: 2018. Version 25. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kline R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Guilford Publications; New York, NY, USA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hair J.F., Black W.C., Babin B.J., Anderson R.E., Tatham R. Multivariate Data Analysis. 17th ed. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaiser H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika. 1974;39:31–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02291575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartlett M.S. Tests of Significance in Factor Analysis. Br. J. Stat. Psychol. 1950;3:77–85. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1950.tb00285.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marôco J. Análise de Equações Estruturais: Fundamentos Teóricos, Software & Aplicações [Structural Equation Analysis: Theoretical Foundations, Software & Applications] Lda; Sintra, Portugal: 2010. ReportNumber. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahalanobis P.C. On the generalised distância in statistics. Proc. Natl. Inst. Sci. India. 1936;2:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Field A. Descobrindo a Estatística Usando O SPSS. Penso Editora; Porto Alegre, Brazil: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hyndman R.J., Koehler A.B. Another look at measures of forecast accuracy. Int. J. Forecast. 2006;22:679–688. doi: 10.1016/j.ijforecast.2006.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bentler P.M. Proceedings of the International Statistical Conference in Memory of Professor Sik-Yum Lee. The Chinese University of Hong Kong; Hong Kong, China: Dec 17–19, 2019. S.-Y. Lee’s Lagrange Multiplier Test in Structural Modeling: Still Useful? p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oliveira C., Torres T. More than skin deep: The systemic nature of atopic dermatitis. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2019;29:250–258. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2019.3557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siegfried E.C., Hebert A.A. Diagnosis of Atopic Dermatitis: Mimics, Overlaps, and Complications. J. Clin. Med. 2015;4:884–917. doi: 10.3390/jcm4050884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pona A., Cline A., Kolli S., Feldman S.F., Fleischer A.F.J., Jr. Prescribing Patterns for Atopic Dermatitis in the United States. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:987–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dolz-Pérez I., Sallam M.A., Masiá E., Morelló-Bolumar D., del Caz M.D.P., Graff P., Abdelmonsif D., Hedtrich S., Nebot V.J., Vicent M.J. Polypeptide-corticosteroid conjugates as a topical treatment approach to psoriasis. J. Control. Release. 2020;318:210–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borda L.J., Perper M., Keri J.E. Treatment of seborrheic dermatitis: A comprehensive review. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2019;30:158–169. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2018.1473554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown L. Pharmacy Magazine. Communications International Group Ltd.; London, UK: 2019. pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bin L., Leung D.Y.M. Genetic and epigenetic studies of atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2016;12:52. doi: 10.1186/s13223-016-0158-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eicher L., Knop M., Aszodi N., Senner S., French L.E., Wollenberg A. A systematic review of factors influencing treatment adherence in chronic inflammatory skin disease—Strategies for optimizing treatment outcome. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019;33:2253–2263. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goman T. Use of topical treatments in psoriasis management. J. Community Nurs. 2017;31:58–67. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tucker R., Stewart D. The role of community pharmacists in supporting self-management in patients with psoriasis. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2017;25:140–146. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamaura K. Topical Treatment of Pruritic Skin Disease and the Role of Community Pharmacists. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2019;139:1563–1567. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.19-00181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teixeira A., Teixeira M., Almeida V., Torres T., Sousa Lobo J.M., Almeida I.F. Methodologies for medication adherence evaluation: Focus on psoriasis topical treatment. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2016;82:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pouliot A., Vaillancourt R. Medication Literacy: Why Pharmacists Should Pay Attention. Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2016;69:335–336. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v69i4.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thoopputra T., Newby D., Schneider J., Li S.C. Interventions in chronic disease management: A review of the literature on the role of community pharmacists. Am. J. Pharm. Heal. Res. 2015;3:82–117. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hiremath A.C., Bhandari R., Wali S., Ganachari M.S., Doshi B. Impact of clinical pharmacist on medication adherence among psoriasis patients: A randomized controlled study. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health. 2021;10:100687. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2020.100687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teixeira A., Oliveira C., Teixeira M., Rita Gaio A., Lobo J.M.S., de Almeida I.F.M., Almeida V. Development and Validation of a Novel Questionnaire for Adherence with Topical Treatments in Psoriasis (QATOP) Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2017;18:571–581. doi: 10.1007/s40257-017-0272-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tulsky J.A., Beach M.C., Butow P.N., Hickman S.E., Mack J.W., Morrison R.S., Street R.L.J., Sudore R.L., White D.B., Pollak K.I. A Research Agenda for Communication between Health Care Professionals and Patients Living with Serious Illness. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017;177:1361–1366. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson J.L., Moser L., Garwood C.L. Health literacy: A primer for pharmacists. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2013;70:949–955. doi: 10.2146/ajhp120306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

As part of consenting to the study, survey respondents were assured that raw data would remain confidential and would not be shared. Descriptive data may be available upon request from the corresponding authors.