Significance

Dietary lipids are packaged into triglyceride-rich lipoprotein particles and delivered to many tissues via the bloodstream. A complex of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and its endothelial cell receptor, GPIHBP1, hydrolyzes lipoprotein triglycerides, releasing fatty acids for uptake by surrounding cells. The efficiency of triglyceride hydrolysis is regulated by physiologic LPL inhibitors: ANGPTL-3, -4, and -8. We defined the binding site for ANGPTL4 on LPL and showed that ANGPTL4 induces allosteric changes in LPL that progress to irreversible unfolding and collapse of LPL’s catalytic site. The binding of GPIHBP1 to LPL augments LPL stability and renders LPL less susceptible to inactivation by ANGPTL4. Our studies provide crucial insights into molecular mechanisms that regulate intravascular triglyceride metabolism.

Keywords: intrinsic disorder, HDX-MS, intravascular lipolysis, GPIHBP1, hypertriglyceridemia

Abstract

The complex between lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and its endothelial receptor (GPIHBP1) is responsible for the lipolytic processing of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRLs) along the capillary lumen, a physiologic process that releases lipid nutrients for vital organs such as heart and skeletal muscle. LPL activity is regulated in a tissue-specific manner by endogenous inhibitors (angiopoietin-like [ANGPTL] proteins 3, 4, and 8), but the molecular mechanisms are incompletely understood. ANGPTL4 catalyzes the inactivation of LPL monomers by triggering the irreversible unfolding of LPL’s α/β-hydrolase domain. Here, we show that this unfolding is initiated by the binding of ANGPTL4 to sequences near LPL’s catalytic site, including β2, β3–α3, and the lid. Using pulse-labeling hydrogen‒deuterium exchange mass spectrometry, we found that ANGPTL4 binding initiates conformational changes that are nucleated on β3–α3 and progress to β5 and β4–α4, ultimately leading to the irreversible unfolding of regions that form LPL’s catalytic pocket. LPL unfolding is context dependent and varies with the thermal stability of LPL’s α/β-hydrolase domain (Tm of 34.8 °C). GPIHBP1 binding dramatically increases LPL stability (Tm of 57.6 °C), while ANGPTL4 lowers the onset of LPL unfolding by ∼20 °C, both for LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes. These observations explain why the binding of GPIHBP1 to LPL retards the kinetics of ANGPTL4-mediated LPL inactivation at 37 °C but does not fully suppress inactivation. The allosteric mechanism by which ANGPTL4 catalyzes the irreversible unfolding and inactivation of LPL is an unprecedented pathway for regulating intravascular lipid metabolism.

The lipolytic processing of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRLs) along the luminal surface of capillaries plays an important role in the delivery of lipid nutrients to vital tissues (e.g., heart, skeletal muscle, adipose tissue). A complex of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and its endothelial cell transporter, glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored high-density lipoprotein-binding protein 1 (GPIHBP1), is responsible for the margination of TRLs and their lipolytic processing (1–3). The importance of the LPL•GPIHBP1 complex for TRL processing is underscored by the development of severe hypertriglyceridemia (chylomicronemia) with loss-of-function mutations in LPL or GPIHBP1 or with GPIHBP1 autoantibodies that disrupt GPIHBP1•LPL interactions (4–7). Chylomicronemia is associated with a high risk for acute pancreatitis, which is debilitating and often life threatening (8, 9). Interestingly, increased efficiency of plasma triglyceride processing appears to be beneficial, reducing both plasma triglyceride levels and the risk for coronary heart disease (CHD). For example, genome-wide population studies have revealed that single-nucleotide polymorphisms that limit the ability of angiopoietin-like proteins 3 or 4 (ANGPTLs) to inhibit LPL are associated with lower plasma triglyceride levels and a reduced risk of CHD (10–14).

GPIHBP1 is an atypical member of the LU domain superfamily because it contains a long intrinsically disordered and highly acidic N-terminal extension in addition to a canonical disulfide-rich three-fingered LU domain (15). At the abluminal surface of capillaries, GPIHBP1 is responsible for capturing LPL from heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) in the subendothelial spaces and shuttling it to its site of action in the capillary lumen (3, 16). The capture of LPL from subendothelial HSPGs depends on electrostatic interactions with GPIHBP1’s intrinsically disordered acidic domain and stable hydrophobic interactions with GPIHBP1’s LU domain (15, 17, 18). In the setting of GPIHBP1 deficiency, LPL never reaches the capillary lumen and remains mislocalized, bound to HSPGs, in the subendothelial spaces. Aside from promoting the formation of GPIHBP1•LPL complexes, the acidic domain plays an important role in preserving LPL activity. The acidic domain is positioned to form a fuzzy complex with a large basic patch on the surface of LPL, which is formed by the confluence of several heparin-binding motifs. This electrostatic interaction stabilizes LPL structure and activity, even in the face of physiologic inhibitors of LPL (e.g., ANGPTL4) (19–22).

Distinct expression profiles for ANGPTL-3, -4, and -8 underlie the tissue-specific regulation of LPL and serve to match the supply of lipoprotein-derived lipid nutrients to the metabolic demands of nearby tissues (21, 23–29). In the fasted state, ANGPTL4 inhibits LPL activity in adipose tissue, resulting in increased delivery of lipid nutrients to oxidative tissues. In the fed state, ANGPTL3•ANGPTL8 complexes inhibit LPL activity in oxidative tissues and thereby channel lipid delivery to adipocytes. While the physiologic relevance of tissue-specific LPL regulation is clear, the mechanisms by which ANGPTL proteins inhibit LPL activity remain both incompletely understood and controversial. One view holds that ANGPTL4 inhibits LPL activity by a reversible mechanism (30, 31). An opposing view, formulated early on by the laboratory of Gunilla Olivecrona, is that ANGPTL4 irreversibly inhibits LPL by a “molecular unfolding chaperone-like mechanism” (32). Hydrogen–deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) studies have supported the latter view. Recent studies by our group revealed that ANGPTL4 catalyzes the irreversible unfolding (and inactivation) of LPL’s α/β-hydrolase domain and that the unfolding is substantially mitigated by the binding of GPIHBP1 to LPL (17, 19, 22). We further showed that ANGPTL4 functions by unfolding catalytically active LPL monomers rather than by promoting the dissociation of catalytically active LPL homodimers (33, 34). Despite these newer findings, a host of issues remains unresolved. For example, the binding site for ANGPTL4 on LPL has been controversial (31, 35); the initial conformational changes induced by ANGPTL4 binding have not been delineated, and how the early conformational changes in LPL progress to irreversible inactivation is unknown. In the current studies, we show, using time-resolved HDX-MS, that ANGPTL4 binds to LPL sequences proximal to the entrance of LPL’s catalytic pocket. That binding event triggers alterations in the dynamics of LPL secondary structure elements that are central to the architecture of the catalytic triad. Progression of those conformational changes leads to irreversible unfolding and collapse of LPL’s catalytic pocket. The binding of GPIHBP1 to LPL limits the progression of these allosteric changes, explaining why GPIHBP1 protects LPL from ANGPTL4-induced inhibition.

Results

Examining ANGPTL4 Binding to LPL•GPIHBP1 Complexes by HDX-MS.

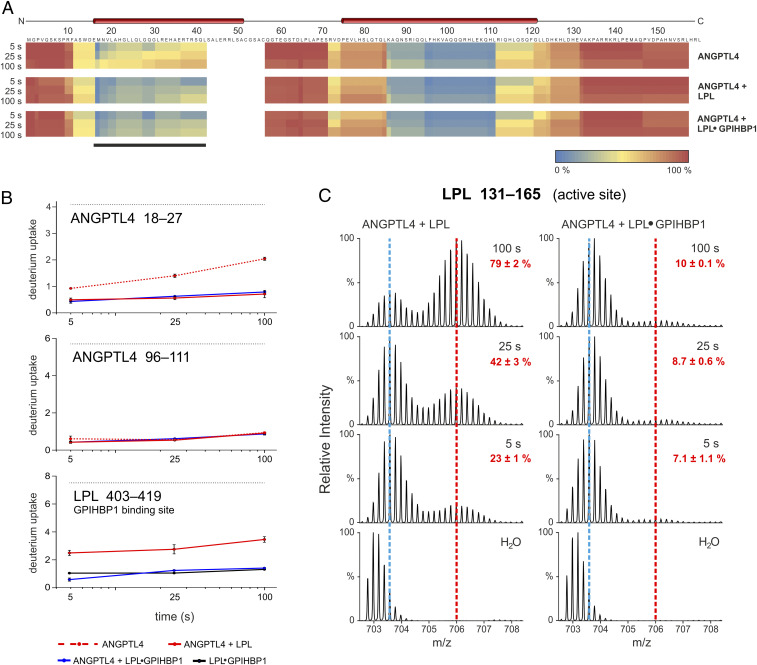

Assessing ANGPTL4 binding to LPL by HDX-MS requires defining experimental conditions in which ANGPTL4 binds to LPL without triggering progressive and irreversible LPL unfolding. Without establishing those conditions, it is difficult to discriminate changes in deuterium uptake caused by the formation of ANGPTL4•LPL complexes from deuterium uptake resulting from progressive ANGPTL4-mediated allosteric unfolding of LPL. After only 5 s at 25 °C, ANGPTL4 unfolds 23% of LPL molecules, evident from the emergence of a bimodal isotope envelope in an LPL peptic peptide spanning the catalytic triad (residue 131–165; see Fig. 1C). Of note, the gradual appearance of bimodal isotope envelopes in that peptide in pulse-labeled HDX-MS studies correlates with the irreversible loss of lipase activity (17–19, 22, 33). In the current studies, we used the emergence of a bimodal isotope envelope in peptide 131–165 as a proxy for LPL unfolding.

Fig. 1.

The GPIHBP1•LPL complex binds to ANGPTL4, but LPL unfolding is blunted. (A) Heat maps depicting deuterium content in 40 peptic peptides from ANGPTL4 (89% sequence coverage), revealing that both unbound LPL and GPIHBP1•LPL complexes bind to ANGPTL4. Deuterium content was measured in triplicate by MS (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) and is shown relative to a fully exchanged control. Regions in blue and red show low and high deuterium uptake, respectively. Data were obtained by incubating 7 µM ANGPTL4 alone (Top) or in the presence of either 10 µM LPL (Middle) or 10 µM LPL + 20 µM GPIHBP1 (Bottom) in deuterium oxide for 5, 25, or 100 s at 25 °C. Predicted α-helices are shown above the primary sequence. The LPL binding site on ANGPTL4 was evident from ANGPTL4 peptides with reduced deuterium uptake (black bar). (B) Time-dependent deuterium uptake in peptic peptides corresponding to the first and second α-helices of ANGPTL4 (residues 18–24 and 96–111, respectively) and in the GPIHBP1-binding region of LPL (residue 403–419). The dotted black lines show fully labeled controls (determined experimentally). The dotted red line is ANGPTL4 alone; the solid red line is ANGPTL4 + LPL. The blue line is ANGPTL4 + LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes; the solid black line is LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes (dataset is from Fig. 2). (C) The unfolding of LPL by ANGPTL4 was reduced when LPL was complexed to GPIHBP1. Shown are isotope envelopes for an LPL peptic peptide covering LPL’s catalytic triad (residue 131–165) when LPL or LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes were incubated with ANGPTL4. The vertical dashed blue line shows isotope envelopes for LPL peptide 131–165 after undergoing uncorrelated EX2 exchange (a measure of local dynamics), whereas the vertical dashed red line shows LPL molecules that had undergone correlated deuterium EX1 exchange (indicative of cooperative unfolding of the hydrolase domain). Red numbers show the fractional unfolding of LPL at different incubation times.

In earlier studies (17, 19, 20), we showed that LPL is much less susceptible to ANGPTL4-catalyzed inactivation and irreversible unfolding when it is bound to GPIHBP1 (a protein of capillary endothelial cells that moves LPL to its site of action in the capillary lumen). Given the lower susceptibility of GPIHBP1-bound LPL to ANGPTL4-catalyzed unfolding, we suspected that LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes would be useful for mapping the interaction between ANGPTL4 and LPL. Because an earlier study raised the possibility that the bindings of ANGPTL4 and GPIHBP1 to LPL are mutually exclusive events (35), we tested the impact of both unbound LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes (both at 10 µM) on ANGPTL4 (7 µM) by continuous deuterium labeling at 25 °C (Fig. 1). By focusing on relatively short sampling times (5, 25, and 100 s), we minimized confounding effects arising from deuterium uptake triggered by allosteric unfolding of LPL (Fig. 1C). Under these conditions, we found that free LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes equally protect ANGPTL4’s first α-helix (residue 18–27), but not its second α-helix (residue 96–111), from deuterium uptake (Fig. 1B), providing solid evidence that ANGPTL4 binds to free LPL and GPIHBP1-bound LPL (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1D). The first α-helix in ANGPTL4 is required for inactivating LPL (36), and a polymorphic variant in that helix destabilizes ANGPTL4 and reduces its ability to inactivate LPL (10, 11, 19). Of note, LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes were not disrupted by the presence of ANGPTL4 (Fig. 1B), evident from persistently low deuterium uptake in LPL residue 403–419 (located within the LPL•GPIHBP1 binding interface) (18, 37). While our observations are incompatible with mutual exclusivity of GPIHBP1 and ANGPTL4 binding to LPL (35), they are consistent with reports showing that ANGPTL4 can interact with GPIHBP1-bound LPL on the surface of endothelial cells (21, 38).

Bimodal isotope envelopes in LPL peptide 131–165 were negligible when LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes were incubated at 25 °C with ANGPTL4 for up to 100 s (Fig. 1C). The blunted ANGPTL4-mediated unfolding of LPL was dependent on GPIHBP1. Omitting GPIHBP1 led to a substantial unfolding of LPL: 23% at 5 s, 42% at 25 s, and 79% at 100 s. The fact that we were able to detect ANGPTL4 binding to LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes without triggering LPL unfolding (irreversible or reversible within a 100-s time window) set the stage for defining ANGPTL4’s binding site on LPL.

Defining the Binding Site for ANGPTL4 on LPL.

We incubated 10 µM LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes with or without a twofold molar excess of ANGPTL4 for 5, 25, 100, or 1,000 s in deuterated solvent at 25 °C. Following online pepsin digestion, deuterium uptake in 92 LPL peptides was assessed by mass spectrometry (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3). As expected, LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes remained stably folded throughout the experiment, evident from the absence of correlated deuterium exchange (producing bimodal isotope envelopes) in LPL peptide 131– 165 (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Importantly, a twofold molar excess of ANGPTL4 induced only negligible correlated exchange (bimodality) in the LPL of LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes at the early time points (5, 25, and 100 s). After a 1,000-s incubation, however, substantial bimodality was observed in LPL peptide 131–165 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Given that bimodal isotope envelopes were absent in peptide 131–165 in pulse-labeling experiments (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), the HDX-MS data from continuous labeling revealed that ∼50% of LPL molecules experienced an ANGPTL4-dependent cooperative opening/closing transition (with EX1 exchange kinetics) of that region after a 1,000-s incubation. It is thus evident that GPIHBP1 binding to LPL allows ANGPTL4 to induce slow reversible unfolding events in LPL even while protecting the LPL from irreversible inactivation (19, 33). This observation is discussed further in the next section, which addresses allostery in LPL resulting from ANGPTL4 binding.

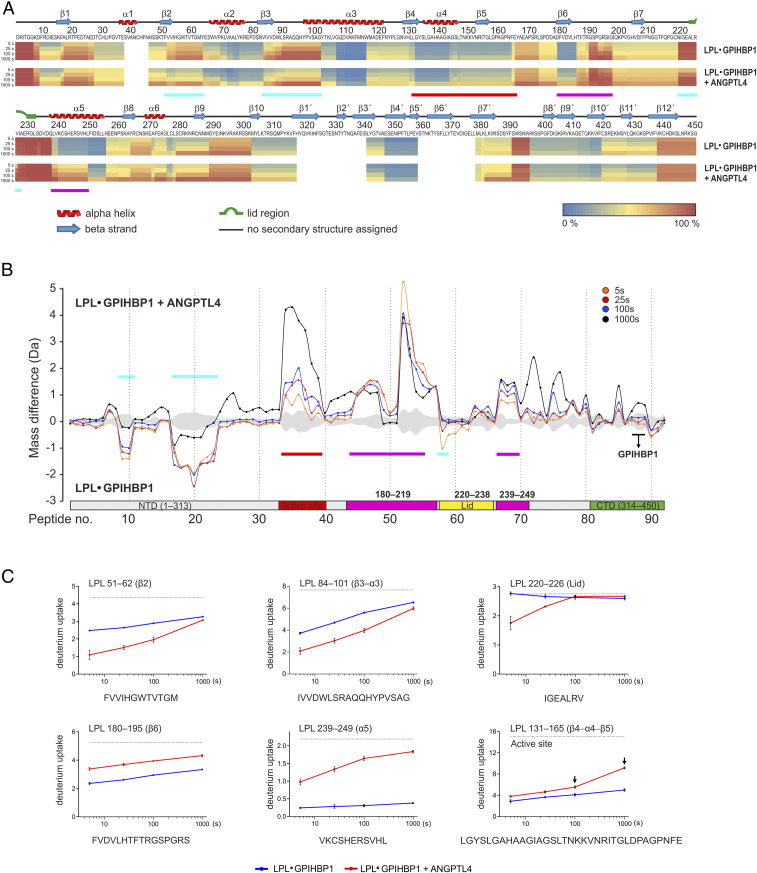

Fig. 2.

Localizing the ANGPTL4 binding site on LPL and defining the allosteric changes in LPL triggered by ANGPTL4 binding. (A) Heat maps depicting deuterium incorporation into LPL peptides relative to a fully labeled control. The data were obtained by incubating 10 µM LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes (formed by 10 µM LPL and 30 µM GPIHBP1) alone (Upper) or with 20 µM ANGPTL4 (Lower) for 5, 25, 100, or 1,000 s in the presence of deuterium oxide at 25 °C. Online pepsin digestion generated 92 LPL peptides corresponding to 88.9% sequence coverage; 79 peptides were used to generate the heat maps (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Secondary structures, shown above the primary sequence, are from the LPL crystal structure (37). Cyan bars indicate areas of protection (i.e., binding sites for ANGPTL4 on LPL); purple bars indicate areas of increased flexibility, and the red bar indicates global changes (bimodal isotope envelopes). (B) Butterfly plot depicting ANGPTL4-induced changes in deuterium uptake into the LPL in GPIHBP1•LPLcomplexes at four different incubation times: 5 s (orange), 25 s (red), 100 s (blue), and 1,000 s (black). Highlighted are regions with reduced deuterium uptake (residues 51–62, 84–101, and 220–226; cyan), increased deuterium uptake by uncorrelated exchange with unimodal isotope envelopes (i.e., increased flexibility; residues 180–219 and 239–249; purple), and increased deuterium uptake by correlated exchange with bimodal isotope envelopes (i.e., unfolding of residue 131–165; red). Peptic LPL peptides from GPIHBP1’s binding site are highlighted by the black bar. The shaded gray area corresponds to the largest SD in the dataset for each peptide (n = 3). (C) Deuterium uptake into selected peptic LPL peptides with reduced deuterium uptake (residues 51–62, 84–101, and 220–226), increased deuterium uptake without isotope bimodality (residues 180−195 and 239–249), and increased uptake with bimodal isotope envelopes (residue 131–165, which contains Ser134 and Asp158 of LPL’s catalytic triad). The arrows indicate correlated exchange as observed by the emergence of bimodal isotope envelopes.

Because of GPIHBP1’s ability to protect LPL from irreversible unfolding, we focused our efforts on 5-, 25-, and 100-s incubations of ANGPTL4 with LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes. We identified three regions, all within LPL’s α/β-hydrolase domain (residues 51–62 [β2], 84–102 [β3–α3], and 220–226 [lid]), with reduced deuterium uptake in the presence of ANGPTL4 (highlighted by the cyan bars in Fig. 2 A and B). This protection was not observed after the longest incubation (1,000 s) (Fig. 2 B and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Deuterium uptake in LPL sequences that interface with GPIHBP1 (e.g., residue 403–419) was low in the 5- to 100-s incubations, demonstrating that ANGPTL4 did not disrupt LPL binding to GPIHBP1 (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

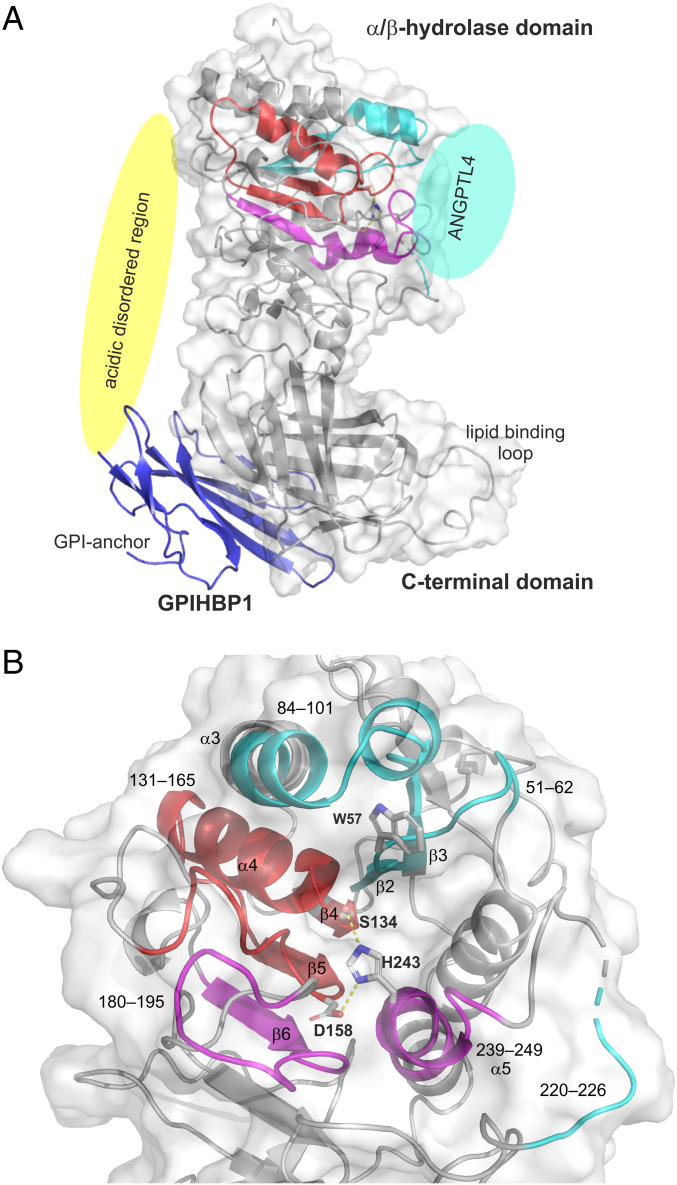

The three LPL segments protected from deuterium uptake by the binding of ANGPTL4 were located along the rim of LPL’s catalytic pocket (Fig. 3), and two of the segments (residues 51–62 [β2] and 84–102 [β3–α3]) represented adjacent regions in LPL’s α/β-hydrolase domain (Fig. 3B). Residue 51–62 forms part of LPL’s oxyanion hole (Trp57) in the active site pocket. The third LPL segment protected by ANGPTL4 binding included the proximal part of LPL’s lid region (residue 220–226). That segment was more distant from residues 51–62 and 84–102 in the LPL crystal structure, but it is important to point out that LPL was crystallized in an open-lid configuration (37). Presumably, the lid region adopts a different and more dynamic conformation in solution.

Fig. 3.

Structural elements in LPL that are affected by ANGPTL4 binding. (A) Cartoon representation of the human LPL•GPIHBP1 complex with the molecular surface of LPL shown as a transparent light gray envelope (generated with PyMol using coordinates from the LPL•GPIHBP1 crystal structure; Protein Data Bank ID code 6E7K). The Trp-rich lipid-binding loop is modeled because it was not visualized in the electron density map (37). LPL elements implicated in ANGPTL4 binding are highlighted in cyan, and those undergoing allosteric changes are highlighted in red (correlated exchange) and purple (noncorrelated exchange). The position of ANGPTL4 binding is indicated with a cyan oval. GPIHBP1 (blue) binds to the C-terminal domain of LPL, and the location of GPIHBP1’s membrane-tethering site (GPI anchor) is indicated. The location of GPIHBP1’s intrinsically disordered acidic domain is depicted with a yellow oval; the acidic domain was not visualized in the crystal structure but is assumed to project over and interact with a large basic patch on the surface of LPL (37). The acidic domain stabilizes LPL’s α/β-hydrolase domain (17, 18). (B) Cartoon representation of the structural elements in LPL surrounding the catalytic triad (Ser134, Asp158, and His243). LPL regions affected by ANGPTL4 binding are color-coded: Sequences bound by ANGPTL4 are cyan; sequences that respond in an allosteric fashion to ANGPTL4 binding are shown in purple and red. The peptide segments and relevant secondary elements are identified by numbers.

Allosteric Changes in the Conformation of LPL in Response to ANGPTL4 Binding.

Having identified the ANGPTL4 binding site on LPL, we turned our attention to defining the allosteric changes in LPL elicited by ANGPTL4 binding. We reasoned that defining the allosteric changes in LPL dynamics could provide insights into how ANGPTL4 unfolds and inactivates LPL’s α/β-hydrolase domain. Of note, we found that ANGPTL4 binding to the LPL in LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes led to increased deuterium uptake in two LPL segments (180–195 [β6] and 239–249 [α5]) without eliciting bimodal isotope envelopes (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Thus, we observed inverse effects of ANGPTL4 on deuterium uptake in different LPL segments: The binding of ANGPTL4 to LPL residues 51–62, 84–101, and 220–226 reduced deuterium uptake in those segments, whereas it increased deuterium uptake into residues 180–195 and 239–249 (by increasing the conformational dynamics of those regions with EX2 exchange kinetics). Both of the latter segments contribute to the architecture of the active site, and segment 239–249 contains one of the residues in LPL’s catalytic triad (His243) (Fig. 3B). The increased dynamics in regions surrounding the active site resulted in increased correlated deuterium uptake in the β4–α4–β5 segment of LPL, evident from the emergence of a bimodal isotope envelope in residue 131–165 (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

At first glance, the emergence of bimodal isotope envelopes in the LPL of LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes might appear to be counterintuitive because we previously reported, using pulse-labeling studies and enzymatic activity assays, that 1) bimodality in peptide 131–165 correlates with loss of LPL activity and 2) GPIHBP1 protects LPL from ANGPTL4-catalyzed inactivation at 25 °C (18, 19, 22, 33). To explore this issue, we used pulse-labeling studies in D2O to probe time-dependent changes in LPL during incubations in protiated solvent. In these studies, we incubated 10 µM LPL, 30 µM GPIHBP1, and 12 µM ANGPTL4 in protiated solvents at 25 °C for up to 5,000 s. Of note, we did not observe, in pulse-labeling studies, bimodal isotope envelopes in LPL peptide 131–165 despite finding increased deuterium uptake in α5 and β6 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). The pulse-labeling studies corroborated the observation that GPIHBP1-bound LPL, at 25 °C, is refractory to ANGPTL4-mediated irreversible unfolding (19, 33). In aggregate, these experiments show that bimodality in LPL residue 131–165 during continuous labeling of LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes in deuterated solvent (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4) reports on a slow and reversible ANGPTL4-catalyzed unfolding (opening/closing) of the β4–α4–β5 region in LPL following EX1 exchange kinetics. At 25 °C, however, these conformational fluctuations do not progress to a permanently unfolded state because of the stabilizing effects of GPIHBP1 binding.

Impact of ANGPTL4 Binding on LPL Stability.

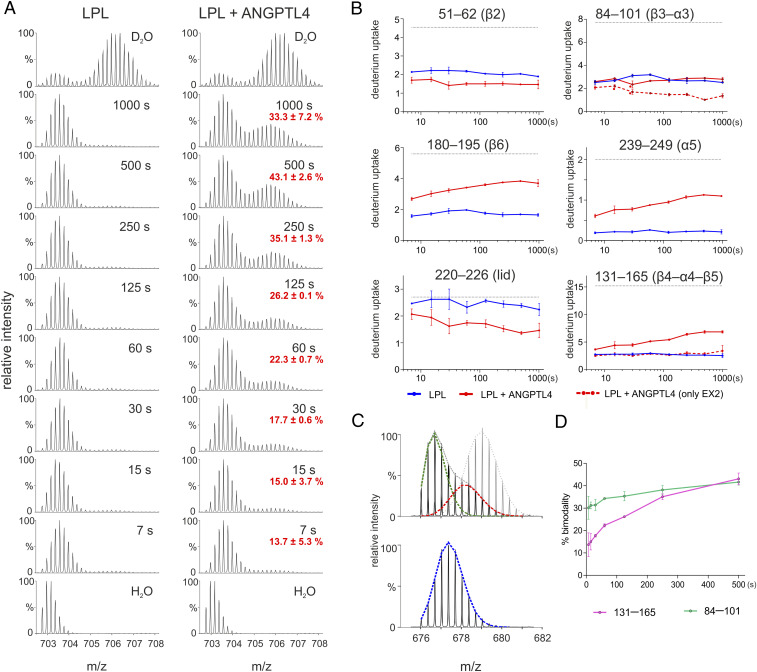

Given that ANGPTL4 binds to both unbound LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes at 25 °C but only unfolds and inactivates unbound LPL (19, 20), it was important to assess ANGPTL4-induced LPL conformational changes in both contexts. To explore ANGPTL4-dependent changes in LPL dynamics in the absence of GPIHBP1, we lowered the temperature to 15 °C. We incubated 10 µM LPL alone or with 12 µM ANGPTL4 in protiated solvent at 15 °C, collected aliquots from 7 to 1,000 s, and then probed LPL conformation by measuring deuterium uptake with 10-s pulse labeling in D2O at 15 °C (Fig. 4). With one key exception, the findings were similar to those for LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes incubated with ANGPTL4 at 25 °C. In the absence of GPIHBP1, ANGPTL4 protected 51–62 (β2), 84–101 (β3–α3), and 220–226 (lid) from deuterium uptake at 15 °C (Fig. 4). One notable difference was observed in β3–α3. Isotope envelopes for peptides covering this region (e.g., residue 84–101) displayed peak broadening with bimodality in the presence of ANGPTL4 (indicative of two coexisting conformations). Only unimodal isotope envelopes were present in this region when LPL was incubated alone (Fig. 4C and SI Appendix, Fig. S6) or when LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes were incubated with ANGPTL4 at 25 °C (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). A comparison of the centroid masses of fitted bimodal isotope envelopes for region 84–101 suggested that the deuterium uptake triggered by ANGPTL4 is best explained by coexistence of a protected population of LPL molecules (mass difference; Δm = −1.9 Da) and an irreversibly unfolded LPL population (Δm = 2.6 Da), calculated relative to the mass of LPL incubated alone (Fig. 4C and SI Appendix, Fig. S6). The distinct kinetics for the emergence of bimodality in 84–101 and 131–165 (Fig. 4D) raised the possibility that the unfolding is nucleated on β3–α3 and subsequently progresses to β4–α4–β5. A comparison of overlapping peptic peptides in this region suggests that the proximal part of α3 is protected by ANGPTL4 (residue 90–102), whereas the unfolding involves both α3 and β3 (residue 84–102) (SI Appendix, Table S1). Finally, ANGPTL4 binding also triggers increased dynamics of LPL residues 180–195 (β6) and 239–249 (α5) at 15 °C, evident from the increase in deuterium uptake detected by pulse labeling after a 5-s incubation in protiated solvent (Fig. 4B). The additional slow increase in deuterium uptake over time indicates that some irreversible unfolding occurs in those segments although it was difficult to assign any bimodality or peak broadening of isotope envelopes (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Analyzing ANGPTL4 binding to LPL at 15 °C by pulse-labeled HDX-MS. (A) Impact of ANGPTL4 on the irreversible unfolding of LPL’s hydrolase domain, as judged by the emergence of a bimodal isotope envelope in the LPL peptic peptide 131–165. LPL alone (and LPL + ANGPTL4) was incubated in a protiated solvent for multiple time points (ranging from 7 to 1,000 s) and then pulse labeled for 10 s in a deuterated solvent. Incubations were performed at 15 °C to retard ANGPTL4-mediated unfolding of LPL’s α/β-hydrolase domain. A fully labeled control is shown as the first spectrum in each column. (B) Deuterium uptake in peptides representing 1) the ANGPTL4 binding site (51–62, 84–101, and 220–226), 2) regions where ANGPTL4 induces increased allosteric fluctuation (180–195 and 239–249), and 3) peptide 131–165 where bimodal isotope envelopes in pulse-labeling HDX-MS serve as a proxy for irreversible inactivation of LPL. In this experiment, two regions exhibited time-dependent ANGPTL4-induced bimodality (84–101 and 131–165). In those regions, the reduced deuterium uptake calculated for the low-mass population representing noncorrelated EX2 exchange (shown as dashed red lines) shows that region 84–101 forms part of the ANGPTL4-binding site and region 131–165 does not. (C) Isotope envelopes for LPL 84–101 after a 250-s incubation in protiated solvent at 15 °C with and without ANGPTL4 followed by a 10-s incubation at 15 °C in deuterated solvent. The fitted dashed lines represent an ANGPTL4-bound LPL peptide (green; centroid mass = 2,193.14 Da), an unfolded peptide (red; centroid mass = 2,198.67 Da), and an unoccupied, folded peptide (blue; centroid mass = 2,195.46 Da). A fully labeled control is shown by the light gray isotope envelope in the upper spectrum. (D) Time-dependent appearance of bimodal isotope envelopes in peptides 84–101 and 131–165 induced by ANGPTL4 at 15 °C.

In conclusion, we find that ANGPTL4 binding unleashes similar conformational changes in LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes, but only in the absence of GPIHBP1 was the LPL channeled into an unfolding trajectory involving destabilization of β3–α3 and β4–α4–β5. The latter changes lead to collapse of structural elements that define the architecture of LPL’s catalytic pocket.

Thermal Stability of LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 Complexes.

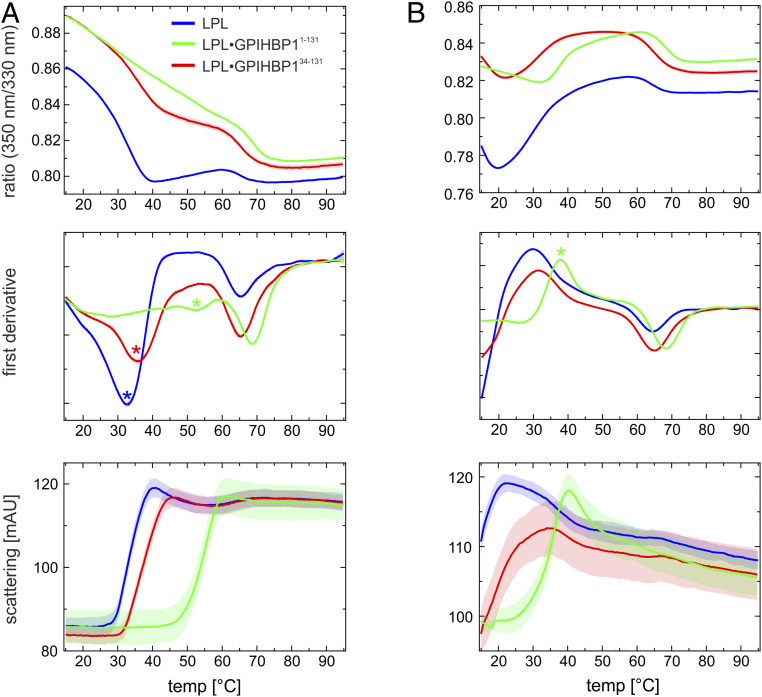

Given that ANGPTL4 binds to the same interface on free LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes, why does ANGPTL4 binding at 25 °C trigger irreversible unfolding only in unbound LPL (and not in GPIHBP1-bound LPL)? A possible explanation rests in the observation that local fluctuations in protein conformations dominate at temperatures well below the melting temperature (Tm), whereas global fluctuations (unfolding/refolding) are predominant at temperatures closer to Tm (39). We speculated that differences in Tm of LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes could explain different susceptibilities to ANGPTL4-catalyzed LPL unfolding. To explore this possibility, we used differential scanning fluorimetry (nano-DSF) to measure thermal unfolding of 10 µM LPL and 10 µM LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes in the presence or absence of 10 µM ANGPTL4. As shown in Fig. 5A and Table 1, the α/β-hydrolase domain of LPL exhibits borderline stability at body temperature (37 °C), with an apparent Tm of 34.8 °C, but the thermal stability is increased dramatically by GPIHBP1 binding (Tm of 57.6 °C) and to a lesser extent by HSPG binding (Tm of 42.2 °C). Deletion of GPIHBP1’s disordered acidic domain markedly reduces GPIHBP1’s capacity to stabilize LPL (Tm of 37.7 °C). As shown in Fig. 5B, ANGPTL4 lowers the apparent melting temperature of the α/β-hydrolase domain of both LPL (Tm < 15 °C vs. Tm = 34.8 °C in the absence of ANGPTL4) and GPIHBP1-bound LPL (Tm = 37.8 °C vs. Tm > 50 °C in the absence of ANGPTL4). In contrast to LPL’s α/β-hydrolase domain, LPL’s C-terminal lipid-binding domain was remarkably stable (Tm of 64.7 °C); neither GPIHBP1 nor ANGPTL4 significantly altered the thermal stability of the C-terminal domain (Table 1).

Fig. 5.

Temperature-induced unfolding of unbound LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes in the presence and absence of ANGPTL4. (A) Thermal unfolding profiles of 10 µM LPL (blue line) in the presence of 10 µM GPIHBP11−131 (green line) or 10 µM GPIHBP134−131 (red line). Shown is the ratio of emissions at a 330 and 350 nm as a function of temperature (Upper), the first derivative of these profiles (Middle), and the change in back scattering (i.e., aggregation) (Lower). The apparent Tm for the α/β-hydrolase is highlighted by a colored asterisk. (B) Corresponding unfolding profiles recorded in the presence of 10 µM ANGPTL4. Note that the unfolding of LPL alone and in the presence of GPIHBP134−131 has already occurred (to a large extent) before the first measurement at 15 °C.

Table 1.

Context-dependent stability of LPL

| Tm for NTD (°C) | Tm for NTD + ANGPTL4 (°C) | Tm for CTD (°C) | Tm for CTD + ANGPTL4 (°C) | |

| LPL | 34.8 ± 0.1 | <15 | 64.7 ± 0.3 | 63.9 ± 0.1 |

| LPL•GPIHBP11−131 | 57.6 ± 0.1* | 36.6 ± 0.1 | 70.1 ± 0.4 | 67.8 ± 0.2 |

| LPL•GPIHBP134−131 | 37.7 ± 0.1 | <15 | 66.7 ± 0.3 | 65.3 ± 0.1 |

| LPL•HSPG (dp8) | 42.2 ± 0.7 | 39.0 ± 0.1 | 68.6 ± 0.4 | 67.6 ± 0.3 |

The apparent melting temperatures (Tm) for 10 µM LPL incubated alone or incubated in the presence of 10 µM GPIHBP1 or 10 µM ANGPTL4 were measured in a temperature gradient from 15 to 95 °C by changes in endogenous tryptophan fluorescence (measured as the 350 nm/330 nm ratio by nanodifferential scanning fluorimetry). Measurements with the heparin derivative dp8 (from Iduron) were performed with 50 µM dp8. The C-terminal domain of human LPL (CTD313−448) has a Tm of 58.7 ± 0.3 °C. This Tm increases to 63.9 ± 1.3 and 66.2 ± 0.2 °C in the presence of GPIHBP134−131 and GPIHBP11−131, respectively. NTD is the N-terminal α/β-hydrolase domain of LPL; CTD is the C-terminal lipid-binding domain of LPL. All profiles were measured in triplicate.

The apparent Tm for LPL complexed to GPIHBP11−131 was calculated from the tryptophan fluorescence at 330 nm (SI Appendix, Fig. S7) due to the shallow dip in the 350 nm/330 nm ratio.

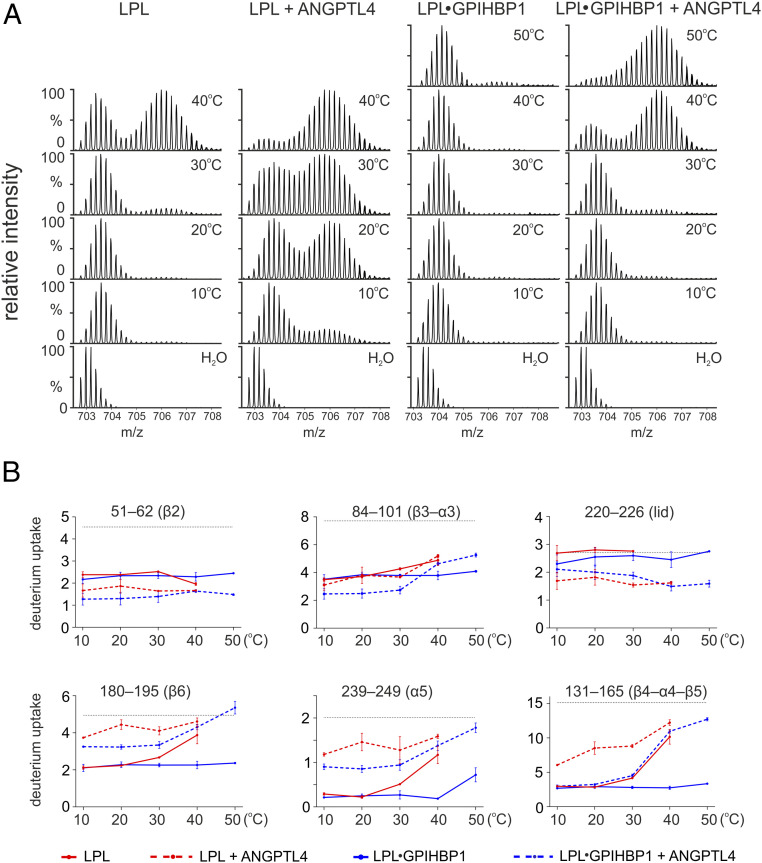

Our data support a model in which ANGPTL4 catalyzes the irreversible inactivation of LPL by lowering the energy barrier for global unfolding of the α/β-hydrolase domain. A corollary to this model is that ANGPTL4-induced unfolding should be far more robust at temperatures closer to LPL’s Tm. Thus, we would predict that pulse labeling of LPL•GPIHBP1 would reveal bimodal isotope envelopes in LPL peptide 131–165 only at very high temperatures but that bimodality in that peptide would emerge at substantially lower temperatures in the presence of ANGPTL4. To test this prediction, we incubated unbound LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes with or without ANGPTL4 in protiated solvents for 180 s at temperatures ranging from 10 to 50 °C and then probed LPL conformation by pulse labeling in deuterated solvents for 10 s at 25 °C. In the absence of ANGPTL4, irreversible unfolding of free LPL occurred between 30 and 40 °C, whereas LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes were stable in temperatures up to 50 °C (Fig. 6). The presence of ANGPTL4 lowered the onset of unfolding for both unbound LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes by ∼20 °C.

Fig. 6.

Temperature-dependent deuterium exchange in unbound LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes in both the presence and absence of ANGPTL4. (A) ANGPTL4-induced unfolding of LPL, assessed by the emergence of bimodality in the LPL peptide 131–165. The 10 µM LPL or 10 µM LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes were incubated alone or in the presence of 12 µM ANGPTL4 in protiated solvent for 180 s at the indicated temperatures, followed by 10-s pulse labeling at 25 °C in deuterated solvent. When LPL was incubated in the presence of ANGPTL4, the bimodal isotope envelope in peptide 131–165 appeared at much lower temperatures (10–20 °C) than LPL incubated without ANGPTL4 (40 °C). Similarly, when LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes were incubated in the presence of ANGPTL4, the bimodal isotope envelope in peptide 131–165 emerged at 40 °C, whereas it was absent at 50 °C when LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes were incubated without ANGPTL4. (B) Deuterium uptake in LPL peptides corresponding to the ANGPTL4 binding site (Upper) and in LPL peptides from LPL segments where ANGPTL4 binding had triggered allosteric conformational changes (Lower). Due to low peak intensity, the uptake in the lid peptide 220–226 is not shown for LPL at 40 °C.

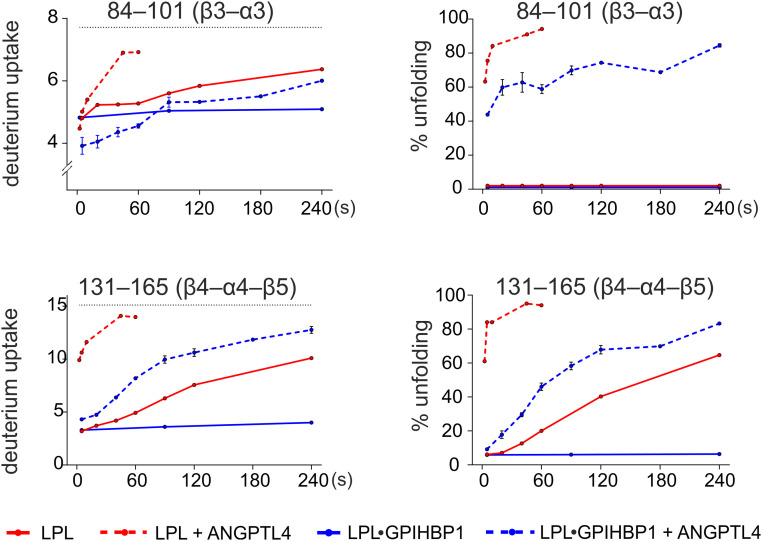

These observations prompted us to use pulse-labeled HDX-MS to explore the kinetics of LPL unfolding at 37 °C. We observed irreversible unfolding of GPIHBP1-bound LPL by ANGPTL4 at 37 °C (the half-life t1/2 ∼ 70 s) but minimal unfolding of GPIHBP1-bound LPL in the absence of ANGPTL4 (Fig. 7). The ANGPTL4-induced irreversible unfolding of unbound LPL was far more rapid (t1/2 < 5 s) than the spontaneous unfolding of LPL in the absence of ANGPTL4 (t1/2 ∼ 180 s) and of LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes in the presence of ANGPTL4 (t1/2 ∼ 70 s). Furthermore, unfolding trajectories at 37 °C included destabilization of similar key structural elements in LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes by ANGPTL4 binding (i.e., 84–102 [β3–α3], 131–165 [β4–α4–β5], 180–195 [β6], and 239–249 [α5]). Examining the kinetics of ANGPTL4-dependent deuterium uptake in overlapping peptides of LPL 131–165 (β4–α4–β5) reveals that residue 147–165 (β5) unfolds before residue 133–145 (β4–α4), indicating that unfolding of β4–α4 is the “point of no return” that leads inexorably to irreversible unfolding of LPL’s hydrolase domain (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Of note, the ANGPTL4-mediated protection from deuterium uptake in LPL 51–62 (β2) and 84–102 (β3–α3) gradually decreases as LPL unfolds, indicating that ANGPTL4 dissociates from the unfolded and inactivated LPL (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). As ANGPTL4 dissociates from LPL, its binding interface on LPL becomes accessible to solvent and susceptible to deuterium exchange, which results in a gradual mass increase in LPL peptides from this region. The transient binding of ANGPTL4 is perfectly consistent with its ability to catalyze LPL unfolding and inactivation.

Fig. 7.

Deuterium incorporation into LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes by pulse labeling in the presence or absence of ANGPTL4 at 37 °C. Left shows deuterium uptake in LPL peptides 84–101 and 131–165 by pulse labeling for 10 s as a function of incubation time in protiated solvent at 37 °C. Right shows the time-dependent progression in LPL unfolding as defined by the relative fractions of peptides 131–165 and 84–101 that had undergone correlated exchange (i.e., irreversibly unfolded).

Discussion

In earlier studies, we proposed a model in which ANGPTL4 permanently inhibits LPL activity by catalyzing the irreversible unfolding of its α/β-hydrolase domain, and we showed that the binding of GPIHBP1 to LPL limits ANGPTL4-mediated unfolding (17, 19, 33). In the current studies, we have gone on to demonstrate that 1) ANGPTL4 binds to regions proximal to LPL’s catalytic pocket (i.e., 51–62 [β2], 84–101 [β3−α3], and 220–226 [lid]), 2) binding of ANGPTL4 to LPL triggers an allosteric increase in the dynamics of LPL structural elements that are crucial for the architecture of LPL’s active site (i.e., 180–195 [β6] and 239–249 [α5]), 3) instability resulting from that allostery ultimately progresses to irreversible unfolding and inactivation of LPL (i.e., bimodality in peptide 131–165 [β4–α4–β5]), 4) LPL’s α/β-hydrolase domain is borderline stable at body temperature, 5) ANGPTL4 binding lowers LPL’s thermal stability by ∼20 °C, and 6) GPIHBP1 binding increases LPL’s thermal stability by ∼23 °C, explaining why LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes are less susceptible to ANGPTL4-catalyzed unfolding.

Despite the key roles of ANGPTL proteins in the tissue-specific regulation of LPL activity, the mechanisms by which they inhibit LPL have been incompletely understood as well as controversial (3, 19, 22, 30, 32, 33). Our current findings, along with our earlier studies (19, 22), conflict with studies holding that ANGPTL4 inhibits LPL via reversible and noncompetitive binding to LPL with an inhibition constant (Ki) of 0.9 to 1.7 µM (30, 31). In reviewing those studies, we found it difficult to reconcile the low inhibitory efficacy of ANGPTL4 and the “reversible/noncompetitive inhibition” model with several earlier observations: 1) that low nanomolar concentrations of ANGPTL4 inhibit the activity of low nanomolar levels of LPL (19, 20, 27, 32), 2) that substoichiometric amounts of ANGPTL4 fully inhibit LPL (19, 32), 3) that LPL inhibition is time dependent (19, 21), and 4) that GPIHBP1 does not restore LPL catalytic activity following ANGPTL4-mediated inhibition (19). Moreover, our current observation that ANGPTL4 binds to the same site on LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes, together with the observation that only unbound LPL is susceptible to ANGPTL4-mediated inhibition at 25 °C (19, 20), seems inconsistent with the reversible/noncompetitive inhibition model. On the other hand, those observations fit well with the model that we have proposed in the current study—that ANGPTL4 catalyzes allosteric conformational changes in LPL that progress to irreversible unfolding and that unbound LPL is particularly susceptible to this unfolding pathway. We propose that the binding of GPIHBP1 stabilizes LPL via its fuzzy interaction with LPL’s basic patch and this interaction counteracts the entry of LPL into the ANGPTL4-mediated unfolding trajectory.

The binding site for ANGPTL4 on LPL (residues 51–62, 84–102, and 220–226), which we mapped by continuous and pulse-labeling HDX-MS, partially overlaps with ANGPTL binding sites proposed in an earlier HDX-MS study (31). In that study, the authors concluded that ANGPTL4 binds to LPL residues 17–26, 89–102, 224–238, and 290–311. A second group concluded, again from HDX-MS studies, that ANGPTL4 binds to LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes by interacting with LPL residue 133–164 (35). We suspect that the different conclusions result from differences in experimental protocols. Both of the earlier studies relied exclusively on continuous labeling strategies, used relatively long incubation times, did not report replicate measurements, and did not consider crucial features of HDX-MS analyses, most importantly the distinction between EX1 and EX2 exchange kinetics (40). Neither study addressed the emergence of bimodal isotope envelopes. We find the latter omission to be a substantial concern because bimodal isotope envelopes are a hallmark of global unfolding in continuous labeling studies and of coexisting protein conformations in the setting of pulse-labeling studies (41, 42). Time-dependent progression in bimodal isotope envelopes needs to be defined, particularly when working with marginally stable proteins such as LPL (43).

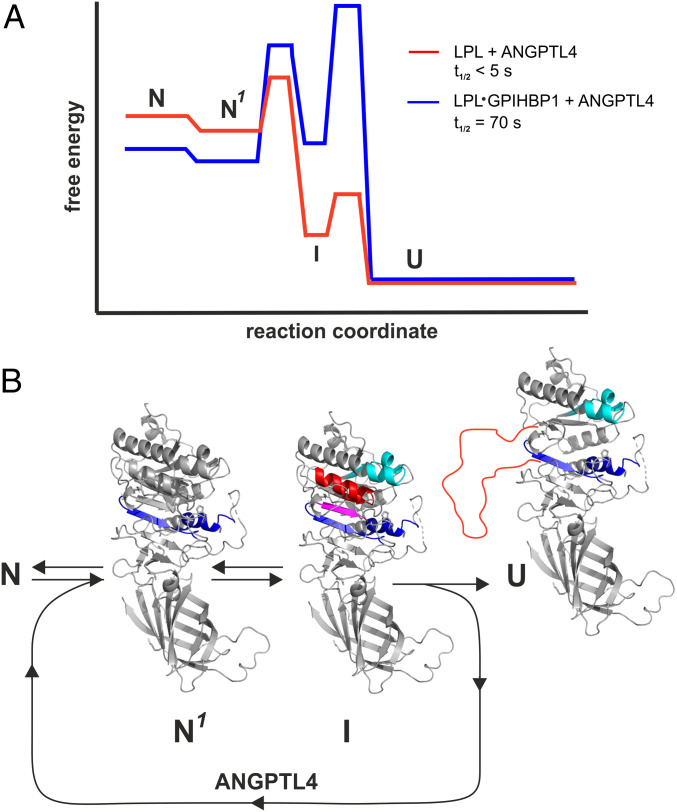

We found that binding of ANGPTL4 triggers similar allosteric changes in unbound LPL and the LPL in LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes: increased conformational dynamics in α5 and β6 (EX2) followed by unfolding of β4–α4–β5. In the case of LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes at 25 °C, these changes are reversible (EX1) and do not lead to irreversible unfolding. In the absence of GPIHBP1, LPL unfolding is nucleated on β3–α3 (part of the ANGPTL4 binding site on LPL) and progresses to involve β5, likely promoted by increased conformational dynamics in β6. Collectively, these changes lead to irreversible unfolding of β4–α4, collapse of the catalytic site, and loss of LPL activity.

Because the delivery of lipid nutrients to tissues needs to be tightly regulated, we speculate that LPL evolved to contain a “weak spot” in a region that is required for protein stability and catalytic activity. We further speculate that ANGPTL4 coevolved to “prey on” LPL’s weak spot, inactivating LPL when it is no longer required to meet metabolic demands of surrounding tissues.

The cooperative unfolding of structures required for the architecture of LPL’s catalytic pocket is reminiscent of the foldon model proposed by Englander and coworkers (41). According to that model, proteins are composed of a variety of foldons that continually unfold and refold, even as the protein remains in the native state. Thus, foldons sample a continuum of partially unfolded native states before entering a globally unfolded state. We propose that ANGPTL4 catalyzes LPL unfolding by destabilizing LPL foldons, thus lowering the kinetic barrier to unfolding and fueling their progression to an irreversible unfolded state (Fig. 8). We further propose that GPIHBP1 binding to LPL—and in particular the interactions between GPIHBP1’s acidic domain and LPL’s basic patch—serves to stabilize foldons in the native state by increasing the kinetic barrier to unfolding (Fig. 8). This stabilization reduces the efficiency of ANGPTL4 in inhibiting GPIHBP1-bound LPL while still allowing ANGPTL4 to function at elevated temperatures. When ANGPTL4 is incubated with LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes at 37 °C, it induces the same unfolding trajectory observed for free LPL (involving α3 and β4–α4–β5), but the irreversible unfolding of LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes occurs with much slower kinetics than the unfolding of unbound LPL. Our observations provide a biophysical explanation for why GPIHBP1 binding prevents ANGPTL4-mediated inhibition of LPL in studies at 20 to 25 °C (19, 20). They also explain why ANGPTL4 inhibition of LPL is attenuated—but not eliminated—when LPL is bound to GPIHBP1 in cell culture experiments, which are typically performed at 37 °C (21, 38).

Fig. 8.

Energy landscape for ANGPTL4-catalyzed unfolding of LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes. (A) Proposed model for ANGPTL4-catalyzed LPL unfolding based on continuous and pulse-labeling HDX-MS studies performed at 15, 25, or 37 °C. Half-lives (t1/2) are calculated from pulse labeling of 10 µM LPL or 10 µM LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes incubated at 37 °C in 10 mM Hepes and 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.4) in the presence of 12 µM ANGPTL4. (B) Allostery in LPL induced by ANGPTL4 binding. N is the native structure of unbound LPL or LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes; N1 is the native structure of LPL or LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes in the setting of ANGPTL4 with increased dynamics of α5 and β6 (EX2 exchange kinetics) highlighted by blue. I is the intermediate conformation with increased dynamics in β3–α3 (cyan) and with reversible unfolding (EX1) of β5 (purple) and β4–α4 (red). U is inactivated LPL with irreversibly unfolded β4–α4–β5 (red line).

Differential sensitivity of unbound LPL and LPL•GPIHBP1 complexes to ANGPTL-mediated inhibition is probably physiologically important. Because ANGPTL4 is more effective in unfolding and inactivating free LPL, we suspect that ANGPTL4 largely functions to inhibit LPL before it reaches GPIHBP1 on capillary endothelial cells [i.e., LPL within the secretory pathway of parenchymal cells (44, 45); LPL that is bound to HSPGs in the subendothelial spaces].

In future studies, it will be important to investigate the mechanisms for LPL inhibition by ANGPTL3•ANGPTL8 complexes, which are crucial for regulating LPL activity in capillaries of oxidative tissues (23, 24, 26, 29). By itself, ANGPTL3 is a relatively weak inhibitor of LPL, but when complexed to ANGPTL8, it is as efficient as ANGPTL4 (24, 26, 27, 46). Our previous studies showed that ANGPTL3 induces LPL unfolding, albeit with low efficiency (19). It would be interesting to assess, in future studies, whether the ANGPTL3•ANGPTL8 complex induces the same unfolding trajectory as ANGPTL4 and to define precise roles for both ANGPTL3 and ANGPTL8 in the binding and inactivation of LPL.

Our identification of the binding site for ANGPTL4, along with the “unfolding pathway” for ANGPTL4-mediated LPL inactivation, could prove useful for developing therapeutic strategies to increase LPL activity. As noted earlier, we suspect that ANGPTL4 evolved to attack a weak spot in LPL’s structure (LPL’s Achilles’ heel), triggering unfolding and a collapse of its active site. We suggest that therapeutic agents (e.g., monoclonal antibodies, small molecules, genetic alterations) designed to buttress LPL’s weak spot could increase its stability and sustain its triglyceride hydrolase activity, rendering it more effective in lowering plasma triglyceride levels.

Materials and Methods

Purified Proteins and Chemicals.

The coiled-coil domain of human ANGPTL4 (residue 1–159) was produced in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) with a pet29a vector (47). A soluble truncated version of GPIHBP1 (residue 1–131) and a mutant GPIHBP1 lacking the acidic domain (“GPIHBP1-Δacidic,” residue 34–131) were produced in Drosophila S2 cells and purified as described (18). Bovine LPL was purified from fresh bovine milk (48). A defined heparin fragment, dp8 (with eight sulfated Ido2S-GlcNS6S units), was purchased from Iduron.

Hydrogen–Deuterium Exchange with Continuous Labeling.

Continuous hydrogen–deuterium labeling of proteins provides information on the exchange of amide hydrogens with deuterium in intact LPL (or LPL complexes) over time and reports on solvent exposure and flexibility of defined regions of a protein. The labeling conditions used for HDX included incubations at 25 °C in 10 mM Hepes and 150 mM NaCl in 70% D2O, adjusted to pD 7.4 (i.e., pHread of 7.0). Two different protein preparations were prepared in protiated Hepes buffer: 1) 7 µM ANGPTL4, 10 µM LPL, and 20 µM GPIHBP1 to investigate the LPL imprint on ANGPTL4 (Fig. 1) and 2) 10 µM LPL, 20 µM ANGPTL4, and 30 µM GPIHBP1 to investigate the ANGPTL4 imprint on LPL (Fig. 2). In both conditions, LPL and GPIHBP1 were preincubated on ice for 10 min to permit efficient complex formation, followed by the addition of ANGPTL4 (or buffer alone) on ice for 10 min. The protein samples were incubated for 2 min at 25 °C to ensure temperature equilibration. The labeling reaction was initiated by adding 2.3 volumes of deuterated Hepes buffer at 25 °C, resulting in a final D2O concentration of 70%. At 5, 25, 100, or 1,000 s, aliquots were withdrawn, and further deuterium exchange was abrogated by adding one volume of ice-cold quenching buffer [100 mM Na2HPO4, 0.8 M Tris-(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, 2 M urea in H2O, pH 2.5]. The quenched samples were immediately placed in an ice bath for 2 min to reduce disulfide bonds and subsequently snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. The samples were stored at –80 °C until analysis by mass spectrometry.

Nondeuterated controls were prepared in the same fashion, except that protiated solvents were used in all steps. Fully deuterated controls were prepared by diluting the samples with deuterated Hepes buffer containing 2 M deuterated urea (10 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl, 2 M urea-d4 in D2O, pHread 7.0); these samples were incubated at 37 °C and on a thermoshaker (300 rpm) for 48 h to achieve exchange equilibrium. The quenching procedure was performed as described earlier, except that no urea was added in order to achieve an identical solvent composition in all samples. All experiments were performed in three independent technical replicates.

Hydrogen–Deuterium Exchange with Pulse Labeling.

The pulse-labeling protocol provides information on temporal changes in LPL conformation in the presence of binding partners. Short labeling pulses in deuterated solvent (5 or 10 s) provide snapshots of progressive changes in protein conformation over time. Buffers and labeling conditions were identical to those described earlier for the continuous labeling protocol and are specified in SI Appendix, Materials & Methods.

Mass Spectrometry.

Deuterium uptake was analyzed by online pepsin digestion and subsequent UPLC-ESI-MS with a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Synapt G2, Waters) (49). Peptic peptides from ANGPTL4 and LPL were identified by collision-induced dissociation with a data-independent (MSe) acquisition mode. Peptic peptides were identified with Protein Lynx Global Server 3.0 (PLGS) software (Waters). The deuterium content of each peptide was determined by processing the data with DynamX 3.0 (Waters). We used HX-Express2 to analyze deuterium uptake in peptides with bimodal isotope envelopes by binomial distribution fitting (50). The relative unfolding of a segment exhibiting bimodal isotope envelopes was calculated as the ratio between the high-mass peptide population and the sum of uptake in the high- and low-mass populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gry E. Rasmussen and Eva C. Østerlund for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Lundbeck Foundation (Grant R230-2016-2930), the NOVO Nordisk Foundation (Grants NNF18OC0033864 and NNF20OC0063444), the John and Birthe Meyer Foundation, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Grants HL146358, HL087228, and HL139725), and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 801481.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2026650118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and SI Appendix.

Change History

April 23, 2021: The Acknowledgments have been updated.

References

- 1.Meng X., Zeng W., Young S. G., Fong L. G., GPIHBP1, a partner protein for lipoprotein lipase, is expressed only in capillary endothelial cells. J. Lipid Res. 61, 591 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goulbourne C. N., et al., The GPIHBP1-LPL complex is responsible for the margination of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in capillaries. Cell Metab. 19, 849–860 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young S. G., et al., GPIHBP1 and lipoprotein lipase, partners in plasma triglyceride metabolism. Cell Metab. 30, 51–65 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beigneux A. P., et al., Autoantibodies against GPIHBP1 as a cause of hypertriglyceridemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 1647–1658 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beigneux A. P., et al., GPIHBP1 missense mutations often cause multimerization of GPIHBP1 and thereby prevent lipoprotein lipase binding. Circ. Res. 116, 624–632 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ariza M. J., et al., Novel mutations in the GPIHBP1 gene identified in 2 patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis. J. Clin. Lipidol. 10, 92–100.e1 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plengpanich W., et al., Multimerization of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored high density lipoprotein-binding protein 1 (GPIHBP1) and familial chylomicronemia from a serine-to-cysteine substitution in GPIHBP1 Ly6 domain. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 19491–19499 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brahm A. J., Hegele R. A., Chylomicronaemia–Current diagnosis and future therapies. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 11, 352–362 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen S. E. J., Madsen C. M., Varbo A., Tybjærg-Hansen A., Nordestgaard B. G., Genetic variants associated with increased plasma levels of triglycerides, via effects on the lipoprotein lipase pathway, increase risk of acute pancreatitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.08.016 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dewey F. E., et al., Inactivating variants in ANGPTL4 and risk of coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 374, 1123–1133 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helgadottir A., et al., Variants with large effects on blood lipids and the role of cholesterol and triglycerides in coronary disease. Nat. Genet. 48, 634–639 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stitziel N. O.et al.; PROMIS and Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium Investigators , ANGPTL3 deficiency and protection against coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 69, 2054–2063 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham M. J., et al., Cardiovascular and metabolic effects of ANGPTL3 antisense oligonucleotides. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 222–232 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dewey F. E., et al., Genetic and pharmacologic inactivation of ANGPTL3 and cardiovasculard disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 211–221 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leth J. M., et al., Evolution and medical significance of LU domain-containing proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 2760 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies B. S., et al., GPIHBP1 is responsible for the entry of lipoprotein lipase into capillaries. Cell Metab. 12, 42–52 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kristensen K. K., et al., A disordered acidic domain in GPIHBP1 harboring a sulfated tyrosine regulates lipoprotein lipase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E6020–E6029 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mysling S., et al., The acidic domain of the endothelial membrane protein GPIHBP1 stabilizes lipoprotein lipase activity by preventing unfolding of its catalytic domain. eLife 5, e12095 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mysling S., et al., The angiopoietin-like protein ANGPTL4 catalyzes unfolding of the hydrolase domain in lipoprotein lipase and the endothelial membrane protein GPIHBP1 counteracts this unfolding. eLife 5, e20958 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonnenburg W. K., et al., GPIHBP1 stabilizes lipoprotein lipase and prevents its inhibition by angiopoietin-like 3 and angiopoietin-like 4. J. Lipid Res. 50, 2421–2429 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chi X., et al., Angiopoietin-like 4 modifies the interactions between lipoprotein lipase and its endothelial cell transporter GPIHBP1. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 11865–11877 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kristensen K. K., Leth-Espensen K. Z., Young S. G., Ploug M., ANGPTL4 inactivates lipoprotein lipase by catalyzing the irreversible unfolding of LPL’s hydrolase domain. J. Lipid Res. 61, 1253 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang R., The ANGPTL3-4-8 model, a molecular mechanism for triglyceride trafficking. Open Biol. 6, 150272 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haller J. F., et al., ANGPTL8 requires ANGPTL3 to inhibit lipoprotein lipase and plasma triglyceride clearance. J. Lipid Res. 58, 1166–1173 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gusarova V., et al., ANGPTL8 Blockade with a monoclonal antibody promotes triglyceride clearance, energy expenditure, and weight loss in mice. Endocrinology 158, 1252–1259 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y. Q., et al., Angiopoietin-like protein 8 differentially regulates ANGPTL3 and ANGPTL4 during postprandial partitioning of fatty acids. J. Lipid Res. 61, 1203–1220 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovrov O., Kristensen K. K., Larsson E., Ploug M., Olivecrona G., On the mechanism of angiopoietin-like protein 8 for control of lipoprotein lipase activity. J. Lipid Res. 60, 783–793 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruppert P. M. M., et al., Fasting induces ANGPTL4 and reduces LPL activity in human adipose tissue. Mol. Metab. 40, 101033 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oldoni F., et al., ANGPTL8 has both endocrine and autocrine effects on substrate utilization. JCI Insight 5, e138777 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lafferty M. J., Bradford K. C., Erie D. A., Neher S. B., Angiopoietin-like protein 4 inhibition of lipoprotein lipase: Evidence for reversible complex formation. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 28524–28534 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gutgsell A. R., Ghodge S. V., Bowers A. A., Neher S. B., Mapping the sites of the lipoprotein lipase (LPL)-angiopoietin-like protein 4 (ANGPTL4) interaction provides mechanistic insight into LPL inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 2678–2689 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sukonina V., Lookene A., Olivecrona T., Olivecrona G., Angiopoietin-like protein 4 converts lipoprotein lipase to inactive monomers and modulates lipase activity in adipose tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 17450–17455 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kristensen K. K., et al., Unfolding of monomeric lipoprotein lipase by ANGPTL4: Insight into the regulation of plasma triglyceride metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 4337–4346 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beigneux A. P., et al., Lipoprotein lipase is active as a monomer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 6319–6328 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nimonkar A. V., et al., A lipoprotein lipase-GPI-anchored high-density lipoprotein-binding protein 1 fusion lowers triglycerides in mice: Implications for managing familial chylomicronemia syndrome. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 2900–2912 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee E. C., et al., Identification of a new functional domain in angiopoietin-like 3 (ANGPTL3) and angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4) involved in binding and inhibition of lipoprotein lipase (LPL). J. Biol. Chem. 284, 13735–13745 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birrane G., et al., Structure of the lipoprotein lipase-GPIHBP1 complex that mediates plasma triglyceride hydrolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 1723–1732 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shetty S. K., Walzem R. L., Davies B. S. J., A novel NanoBiT-based assay monitors the interaction between lipoprotein lipase and GPIHBP1 in real time. J. Lipid Res. 61, 546–559 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tajoddin N. N., Konermann L., Analysis of temperature-dependent H/D exchange mass spectrometry experiments. Anal. Chem. 92, 10058–10067 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Masson G. R., et al., Recommendations for performing, interpreting and reporting hydrogen deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) experiments. Nat. Methods 16, 595–602 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Englander S. W., Mayne L., Kan Z. Y., Hu W., Protein folding-how and why: By hydrogen exchange, fragment separation, and mass spectrometry. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 45, 135–152 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Konermann L., Pan J., Liu Y. H., Hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry for studying protein structure and dynamics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 1224–1234 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trelle M. B., Madsen J. B., Andreasen P. A., Jørgensen T. J., Local transient unfolding of native state PAI-1 associated with serpin metastability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 9751–9754 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dijk W., et al., Angiopoietin-like 4 promotes intracellular degradation of lipoprotein lipase in adipocytes. J. Lipid Res. 57, 1670–1683 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dijk W., Ruppert P. M. M., Oost L. J., Kersten S., Angiopoietin-like 4 promotes the intracellular cleavage of lipoprotein lipase by PCSK3/furin in adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 14134–14145 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chi X., et al., ANGPTL8 promotes the ability of ANGPTL3 to bind and inhibit lipoprotein lipase. Mol. Metab. 6, 1137–1149 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robal T., Larsson M., Martin M., Olivecrona G., Lookene A., Fatty acids bind tightly to the N-terminal domain of angiopoietin-like protein 4 and modulate its interaction with lipoprotein lipase. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 29739–29752 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bengtsson-Olivecrona G., Olivecrona T., Phospholipase activity of milk lipoprotein lipase. Methods Enzymol. 197, 345–356 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leth J. M., Mertens H. D. T., Leth-Espensen K. Z., Jørgensen T. J. D., Ploug M., Did evolution create a flexible ligand-binding cavity in the urokinase receptor through deletion of a plesiotypic disulfide bond? J. Biol. Chem. 294, 7403–7418 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guttman M., Weis D. D., Engen J. R., Lee K. K., Analysis of overlapped and noisy hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectra. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 24, 1906–1912 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and SI Appendix.