Abstract

Migratory wild birds acquire antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) bacteria from contaminated habitats and then act as reservoirs and potential spreaders of resistant elements through migration. However, the role of migratory wild birds as antimicrobial disseminators in the Arabian Peninsula desert, which represents a transit point for birds migrating all over Asia, Africa, and Europe not yet clear. Therefore, the present study objective was to determine antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in samples collected from migratory wild birds around Al-Asfar Lake, located in Al-Ahsa Oasis, Eastern Saudi Arabia, with a particular focus on Escherichia coli virulence and resistance genes. Cloacal swabs were collected from 210 migratory wild birds represent four species around Al-Asfar. E. coli, Staphylococcus, and Salmonella spp. have been recovered from 90 (42.9%), 37 (17.6%), and 5 (2.4%) birds, respectively. Out of them, 19 (14.4%) were a mixed infection. All samples were subjected to AMR phenotypic characterization, and results revealed (14–41%) and (16–54%) of E. coli and Staphylococcus spp. isolates were resistant to penicillins, sulfonamides, aminoglycoside, and tetracycline antibiotics. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) E. coli and Staphylococcus spp. were identified in 13 (14.4%) and 7 (18.9%) isolates, respectively. However, none of the Salmonella isolates were MDR. Of the 90 E. coli isolates, only 9 (10%) and 5 (5.6%) isolates showed the presence of eaeA and stx2 virulence-associated genes, respectively. However, both eaeA and stx2 genes were identified in four (4.4%) isolates. None of the E. coli isolates carried the hlyA and stx1 virulence-associated genes. The E. coli AMR associated genes blaCTX-M, blaTEM, blaSHV, aac(3)-IV, qnrA, and tet(A) were identified in 7 (7.8%), 5 (5.6%), 1 (1.1%), 8 (8.9%), 4 (4.4%), and 6 (6.7%) isolates, respectively. While the mecA gene was not detected in any of the Staphylococcus spp. isolates. Regarding migratory wild bird species, bacterial recovery, mixed infection, MDR, and AMR index were relatively higher in aquatic-associated species. Overall, the results showed that migratory wild birds around Al-Asfar Lake could act as a reservoir for AMR bacteria enabling them to have a potential role in maintaining, developing, and disseminating AMR bacteria. Furthermore, results highlight the importance of considering migratory wild birds when studying the ecology of AMR.

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance, E. coli, Salmonella, Staphylococcus, migratory wild birds, multidrug

1. Introduction

Migratory and resident wild birds are important reservoirs and spreaders of zoonotic and antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) bacteria [1]. About 5 billion migratory wild birds fly across continents twice a year [2], facilitating the global transfer of several pathogens [3]. Different pathogenic bacterial species were isolated from wild birds, including Escherichia coli (E. coli) [4], Salmonella [5], Staphylococcus spp. [6], Campylobacter [7], and Listeria monocytogenes [8]. Indirect transmission of these pathogens to humans has also been reported [9].

AMR is a dynamic and multifaceted One Health problem involving humans, animals, and the environment [10]. Even though the exact mechanism of environmental dissemination of AMR is not fully understood, existing research revealed the central role of human factors [11]. Furthermore, several growing pieces of evidence indicate the ability of migratory wild birds to transport resistant elements to regions away from their anthropogenic origin [12].

The uncontrolled use of antimicrobial therapy in veterinary medicine and humans [13] leads to the discharge of AMR bacteria to untreated sewage, livestock farms, wastewater treatment facilities, aquaculture ponds, and landfills [14,15,16]. The discharged AMR bacteria find their way to the migratory wild bird habitats representing extra selective pressure for resistant bacteria in addition to the risk for long-distance dispersal to unexposed wildlife and free-range animal [12]. The resulting proliferation and dissemination of AMR bacteria to the environment highlight the importance of integrating resident and migratory wild birds in AMR epidemiology to better understand and manage this global public health concern.

Al-Asfar Lake (Yellow Lake) is one of the important shallow wetland lakes in a desert environment in Saudi Arabia that attracted the first inhabitants of this region to settle around the lake waters. The lake is located close to Al-Ahsa Oasis, which is considered the largest and oldest agricultural center in the eastern region of Saudi Arabia. Al-Asfar Lake is a large artificial water body formed from the agriculture and livestock drainage water of the earthen drainage network [17]. The nature of the lake formation is a rear landing area in the huge Arabian Peninsula desert for migratory wild birds [18,19], necessitated the importance of studying the prevalence of AMR in migratory wild birds around the lake to broaden our understanding of antimicrobials dissemination under such an environmental condition.

Although the role of migratory wild birds in the emergence of resistant bacteria is widely recognized in different localities worldwide [3,20,21,22,23], few studies have investigated the role of migratory wild birds in facilitating the transfer of resistant bacteria in Saudi Arabia [24,25,26]. Thus, the present study’s main objective was to determine the presence of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in samples collected from migratory wild birds around Al-Asfar Lake, with a particular focus on E. coli virulence and resistance genes.

2. Results

2.1. Bacterial Isolates

A total of 132 bacterial isolates were recovered from 113 out of 210 captured migratory wild birds, including 90 (68.2%) E. coli, 5 (3.8%) Salmonella typhimurium (S. typhimurium), and 37 (28%) Staphylococcus spp. isolates. E. coli and S. typhimurium were detected in 90 (42.9%) and 5 (2.4%) birds, respectively, whereas, Staphylococcus spp. were detected in 37 (17.6%) birds (Table 1). Mixed infection of E. coli and S. typhimurium was detected in one (0.5%) bird, while E. coli and Staphylococcus spp. were detected in 18 (8.6%) birds. The frequency of E. coli, S. typhimurium, and Staphylococcus spp. isolation from each species of the captured wild birds was presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number and percentage of Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, and Staphylococcus spp. isolates recovered from different species of migratory wild birds around Al-Asfar Lake.

| Bacteria Species | No. (%) of Bacterial Isolated | Total (n = 210) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common Pochard (n = 50) |

Pied Avocet (n = 30) |

Little Grebe (n = 60) |

Ruddy Shelduck (n = 70) |

||

| E. coli | 20 (40.0) | 8 (30.0) | 27 (45.0) | 35 (50.0) | 90 (42.9) |

| Salmonella | |||||

| S. typhimurium | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.3) | 2 (2.9) | 5 (2.4) |

| Staphylococcus | 37 (17.6) | ||||

| St. aureus | 6 (12.0) | 3 (10.0) | 6 (10.0) | 5 (7.1) | 20 (9.5) |

| St. intermedius | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (1.7) | 3 (4.3) | 5 (2.4) |

| St. xylosus | 4 (8.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.9) |

| St. capitis | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.4) | 3 (1.4) |

| St. saccharolyticus | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.4) | 3 (1.4) |

| St. saprophyticus | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (1.0) |

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test

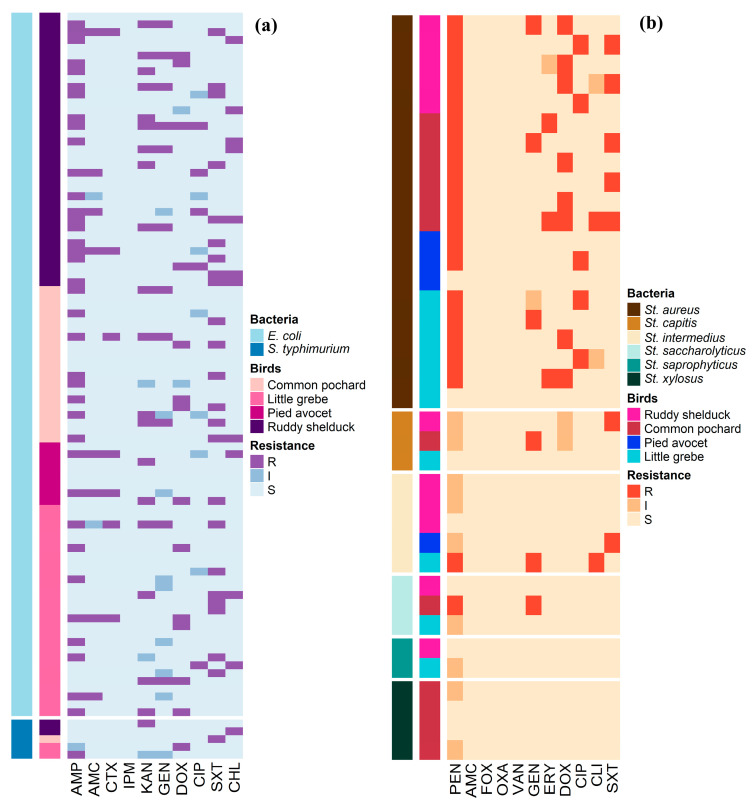

Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of the 90 E. coli and 5 S. typhimurium isolates are illustrated in Figure 1a. Whereas, Figure 1b shows the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Staphylococcus spp. The antimicrobial susceptibility test showed that 41.1% of E. coli isolates were resistant to AMP, and 24.4% were resistant to SXT. However, no isolate was resistant to IPM (Table 2). S. typhimurium isolates showed resistance to AMP, KAN, DOX, SXT, and CHL (20%, each), and none of the isolates showed resistance to AMC, CTX, IPM, GEN, and CIP (Table 2). Staphylococcus isolates showed high frequencies of resistance to PEN (54.1%) and DOX (21.6%), while the lowest number of Staphylococcus resistant isolates were observed for CLI (5.4%) and ERY (8.1%) (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Distribution and clustering of Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, and Staphylococcus isolates recovered from different species of migratory wild birds around the Al-Asfar Lake. (a) Heat map representation of antimicrobial-resistant profiles of the 90 Escherichia coli and 5 Salmonella typhimurium isolates. (b) Heat map representation of antimicrobial-resistant profiles of the 37 Staphylococcus isolates.

Table 2.

The antimicrobial-resistant profiles of Escherichia coli (n = 90) and Salmonella typhimurium (n = 5) isolates recovered from migratory wild birds around the Al-Asfar Lake.

| Antimicrobials | No. of Resistant E. coli Isolates (%) | No. of Resistant Salmonella Isolates (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank 1 | Class | Agents | n | Common Pochard | Pied Avocet | Little Grebe | Ruddy Shelduck | n | Common Pochard | Pied Avocet | Little Grebe | Ruddy Shelduck |

| II | Penicillins | PEN | 37 | 8 (21.6) | 2 (5.4) | 8 (21.6) | 19 (51.4) | 1 | − | − | 1 (100.0) | − |

| AMC | 8 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (25.0) | 2 (25.0) | 4 (50.0) | 0 | − | − | − | − | ||

| I | Cephalosporins | CTX | 7 | 1 (14.3) | 2 (28.6) | 2 (28.6) | 2 (28.6) | 0 | − | − | − | − |

| I | Carbapenem | IPM | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | − | − | − | − | |

| I | Aminoglycoside | KAN | 19 | 4 (21.1) | 2 (10.5) | 4 (21.1) | 9 (47.4) | 1 | − | − | − | 1 (100.0) |

| GEN | 11 | 3 (27.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (18.2) | 6 (54.5) | 0 | − | − | − | − | ||

| II | Tetracycline | DOX | 13 | 3 (23.1) | 1 (7.7) | 5 (38.5) | 4 (30.8) | 1 | − | − | 1 (100.0) | − |

| I | Quinolones | CIP | 5 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | 0 | − | − | − | − |

| II | Sulfonamide | SXT | 23 | 6 (26.1) | 1 (4.3) | 7 (30.4) | 9 (39.1) | 1 | − | − | − | − |

| II | Amphenicols | CHL | 11 | 1 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (18.2) | 7 (63.6) | 1 | − | − | − | 1 (100.0) |

1 Rank I, critically important; rank II, highly important (based on World Health Organization’s categorization).

Table 3.

The antimicrobial-resistant profile of Staphylococcus (n = 37) isolates recovered from migratory wild birds around the Al-Asfar Lake.

| Antimicrobials | No. of Resistant Staphylococcus Isolates (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank 1 | Class | Agents | n | Common Pochard | Pied Avocet | Little Grebe | Ruddy Shelduck |

| II | Penicillins | PEN | 20 | 7 (35.0) | 2 (10.0) | 6 (30.0) | 5 (25.0) |

| AMC | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| OXA | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| I | Cephalosporins | FOX | − | − | − | − | − |

| I | Glycopeptides | VAN | − | − | − | − | − |

| I | Aminoglycoside | GEN | 6 | 3 (50.0) | − | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) |

| I | Macrolide | ERY | 3 | 2 (66.7) | − | 1 (33.3) | − |

| II | Tetracycline | DOX | 8 | 3 (37.5) | − | 2 (25.0) | 3 (37.5) |

| I | Quinolones | CIP | 5 | − | 1 (20.0) | 2 (40.0) | 2 (40.0) |

| II | Lincosamides | CLI | 2 | 1 (50.0) | − | 1 (50.0) | − |

| II | Sulfonamide | SXT | 7 | 3 (42.9) | 1 (14.3) | − | 3 (42.9) |

1 Rank I, critically important; rank II, highly important (based on World Health Organization’s categorization).

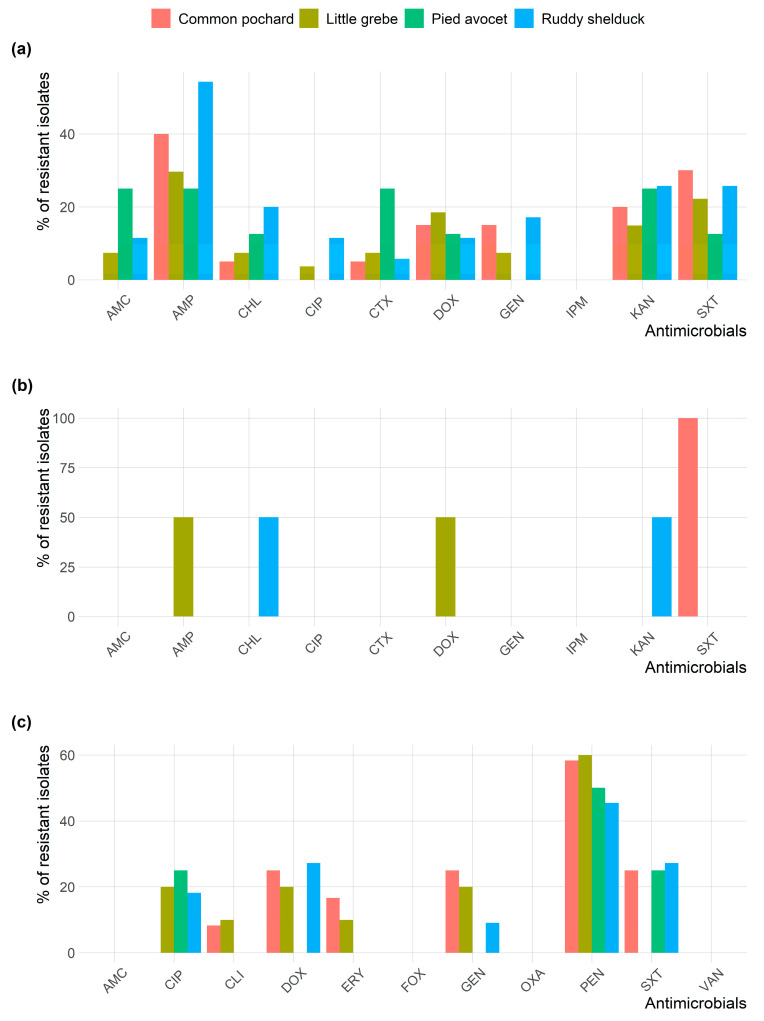

All Staphylococcus isolates were susceptible to AMC, OXA, FOX, and VAN. Figure 2 shows the frequency AMR of E. coli, S. typhimurium, and Staphylococcus spp. isolates in different species of migratory wild birds. E. coli and Staphylococcus isolates resistance to AMP and PEN, respectively, were the most prevalent type of resistance among the different species of migratory wild birds.

Figure 2.

Frequency of antimicrobial resistance of (a) Escherichia coli; (b) Salmonella typhimurium; and (c) Staphylococcus spp. recovered from different species of migratory wild birds around the Al-Asfar Lake.

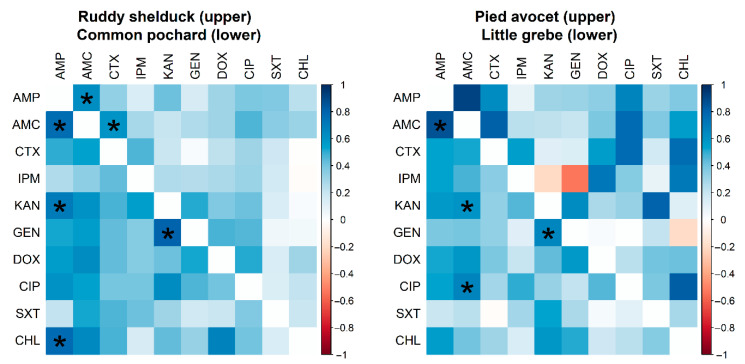

However, no significant difference (p > 0.05) was detected between resistance rates of E. coli isolated from different species of migratory wild birds. Many significant pairwise correlations were detected between minimum inhibitory concentration values for different antimicrobials against E. coli isolated from different migratory wild bird species (Figure 3). The strongest significant (p < 0.001) correlation coefficients were detected between AMP and AMC (r = 0.62; Ruddy shelduck), Amp and CHL (r = 0.77; Common pochard), and AMP and AMC (r = 0.86; Little grebe).

Figure 3.

Spearman rank correlation test results based on the minimum inhibitory concentrations of Escherichia coli (n = 90) isolates recovered from different species of migratory wild birds for ten antimicrobials. The blue color indicated a positive correlation, and the red shows a negative correlation. Strikes (*) indicate significance at p < 0.001.

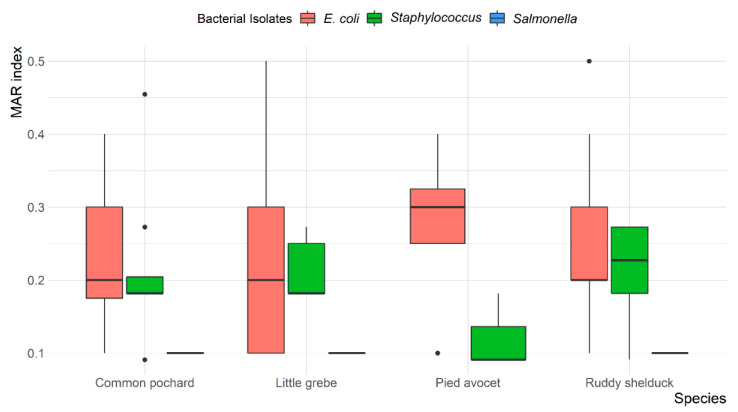

Overall, MDR was observed in 13 (14.4%) E. coli and 7 (18.9%) Staphylococcus spp. isolates, with resistance up to four different antibiotic classes. None of the S. typhimurium isolates were MDR. The mean multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) index was 0.24 (ranged from 0.1 to 0.5) for E. coli, 0.1 for S. typhimurium, and 0.20 (ranged from 0.09 to 0.45) for Staphylococcus spp. Most E. coli (78.6%) and Staphylococcus spp. (69.6%) isolates showed a MAR index of >0.2. However, all S. typhimurium (100%) showed a MAR index of <0.2. The variation between MAR index of E. coli, S. typhimurium, and Staphylococcus spp. recovered from different species of migratory wild birds is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Box and whisker plot of multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) index among Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, and Staphylococcus spp. recovered from different species of migratory wild birds around the Al-Asfar Lake.

2.3. Virulence and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes

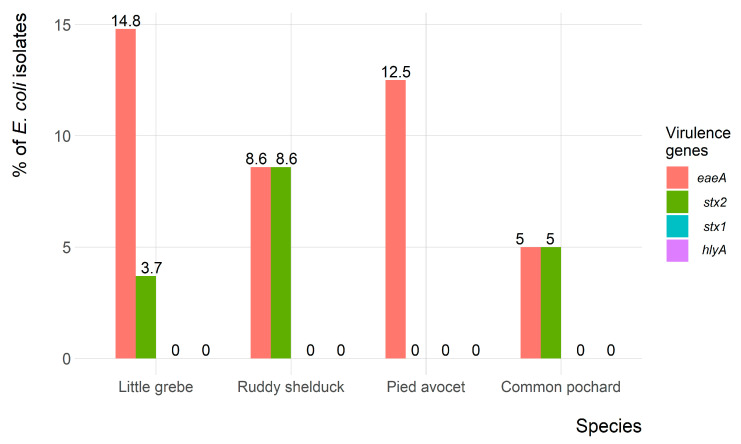

Of the 90 E. coli isolates, only 9 (10%) and 5 (5.6%) isolates showed the presence of eaeA and stx2 virulence-associated genes, respectively. However, both eaeA and stx2 genes were identified in four (4.4%) isolates. None of the E. coli isolates carried the hlyA and stx1 virulence-associated genes. The frequency of virulence genes in E. coli isolates recovered from each migratory wild bird species is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Frequency of virulence genes of Escherichia coli (n = 90) isolates recovered from migratory wild birds around the Al-Asfar Lake.

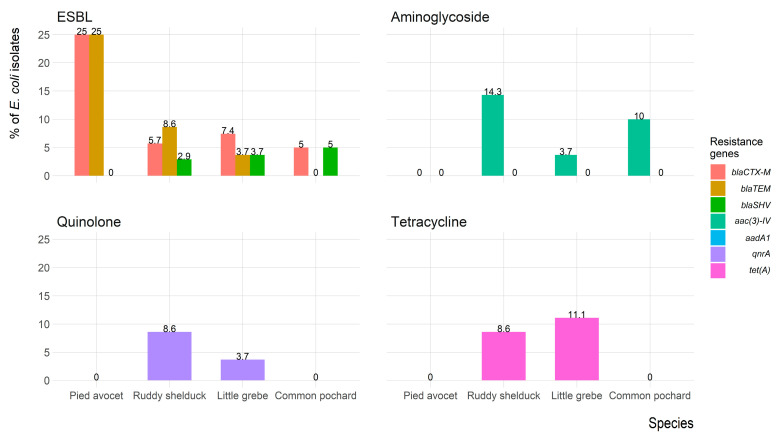

Figure 6 shows the frequency of antimicrobial resistance genes of E. coli isolates recovered from each migratory wild bird species. The antimicrobial-resistance gene blaCTX-M was identified in seven (7.8%) isolates (three isolates were blaCTX-M1 positive, and four isolates were blaCTX-M-15 positive); five (5.6%) isolates expressed blaTEM, and one (1.1%) isolate expressed blaSHV. However, both blaCTX-M and blaTEM were identified in five (5.6%) isolates, and one (1.1%) isolate carried blaCTX-M and blaSHV. Aminoglycosides resistance gene aac(3)-IV was detected in eight (8.9%) isolates, whereas the aadA1 gene was not detected in any isolates. The quinolones (qnrA) and tetracycline (tet(A)) resistance genes were detected in four (4.4%) and six (6.7%) isolates, respectively. The mecA gene was not detected in any of the Staphylococcus spp. isolates.

Figure 6.

Frequency of antimicrobial resistance genes of Escherichia coli (n = 90) isolates recovered from migratory wild birds around the Al-Asfar Lake.

3. Discussion

Although migratory wild birds are not implicated directly in the development of antimicrobial resistance since it is not treated with antimicrobial agents, migratory wild birds may act as a reservoir, mixing pot and spreaders of AMR and important indicator for mirroring the impact of human activities (i.e., improper use of antimicrobials) on the environment [11,27,28]. The Arabian Peninsula Desert represents a transit point, especially from August to October and March to May, for birds that migrate all over the distance between Asia, Africa, and Europe, in addition to native wild birds. In deserts, the wetland around oases represents the main landing area for migratory birds where it becomes in close contact with human activities.

In the present study, E. coli and S. typhimurium were recovered from 42.9% and 2.4% of the collected samples, respectively. The reported E. coli positive birds were relatively lower than previously reported in Switzerland (53.7%) [28] and Saudi Arabia (93.0%) [29] and higher than that reported in Singapore (27.1%) [30]. Whereas the prevalence of Salmonella positive birds in this study was higher than the 0.99% reported in Singapore [31] and lower than the 12.3% reported in Spain [32]. Only S. typhimurium serovar was isolated in the present study that has also been described in wild birds related to animal husbandry as a primary source of infection [32]. The low prevalence of Salmonella spp. reported in the current study might be attributed to the collection of samples from apparently healthy migratory wild birds compared to other studies performed on specimens from dead or dying birds [33,34].

E. coli frequently used as an indicator for the microbiological quality of water [11,35]. Data in the present study showed a higher incidence of E. coli recovery from waterfowl (Common pochard, Little grebe and Ruddy shelduck) comparing to Pied avocet that is relatively less dependent on water. The same finding extends to S. typhimurium and Staphylococcus recovery. In the same context, 21%, 42%, and 37% of mixed infection cases were recovered from Ruddy shelduck, Common pochard, and little grebe, respectively, whereas no mixed infections were detected in Pied avocet. Previous studies in Saudi Arabia mainly addressed E. coli AMR in resident wild birds [29,36].

To better understand AMR prevalence in wildlife, it is important to include multiple bacteria, pathogenic and commensal, with different resistance patterns [30]. In the present study, the phenotypic AMR has been addressed in three major bacterial species; the results revealed 14.4 and 18.9% of the E. coli and Staphylococcus spp. strains presented MDR. Whereas none of the Salmonella strains presented MDR. Salmonella is known to be of lower ability to acquire resistance, making it less susceptible to antimicrobial selection pressure than other tested bacteria [30,31]. According to the WHO classification, tetracyclines, penicillins, and sulfonamides were classified as highly important, aminoglycoside was critically important, and cephalosporins (3rd, 4th, and 5th generations) was the highest priority critically important antimicrobials for human medicine [37]. Phenotypically, about (41 and 54%), (26% and 19%), (21%, and 16%), and (14%, and 22%) of E. coli and Staphylococcus spp. isolates were resistant to penicillins, sulfonamides, aminoglycoside, and tetracycline antibiotics, respectively. In addition, seven E. coli isolates (7.8%) were the ESBL-producer based on the phenotypic profile and detection of the blaCTX-M gene. These results were similar to previous studies where ESBL-producing E. coli was first detected in wild birds in Portugal [38], and extended-spectrum cephalosporin-producing Enterobacteriaceae have been isolated from a wide range of bird species across the world [3,27]. None of the isolates recovered in the present study were resistant to carbapenem. While carbapenem resistance is still uncommon in wild animals, there are serious concerns about the emergence of NDM-1 and IMP carbapenemases in wild birds [21,39]. This goes in context with the antibiotic resistance pattern of bacteria isolated from water spring, which is the origin of the Al-Asfar Lake where 76.9%, 65.4%, and 50% of bacterial isolates are resistant to penicillins, aminoglycoside, and tetracycline, respectively [40]. This may explain why birds (i.e., Pied Avocet) with relatively lower water dependence showed significantly lower resistance to all antibiotics.

It is worth noting that the highest prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria has been recorded in aquatic-associated birds, which agrees with previous findings [3,27]. Thus, the significantly higher antibiotic resistance in E. coli isolates recovered from Ruddy shelduck in the present study may be related to their feeding and living habits. However, fecal samples collected from Ruddy shelduck around Qinghai Lake, China, showed weak antibiotic resistance to E. coli [16]. There are many reasons for differences in antimicrobial resistance in the normal microbiota of migratory wild birds. First, resistance can evolve de novo through spontaneous mutation (s) [41]. Second, horizontal gene transfer from other microbes can develop resistance; certain bacteria and fungi represent natural sources of genes for drug resistance and can function as reservoirs in the environment [42]. Third, bacteria with antimicrobial drug resistance could be introduced into the area either by migratory birds or by human waste (food and excretion) from local fishermen, settlers, and prospectors.

In the present study, the eaeA and stx2 virulence-associated genes were identified in 10%, and 5.6% of the E. coli isolates, respectively. This result was consistent with Kobayashi et al. [43], who identified eaeA and stx2 in Japan. However, the incidence of the eaeA and stx2 reported in the present study was higher than the 2.3% reported in wild brides in Iran [44]. Several studies have reported the association of eaeA and stx2 genes, which indicated the importance of testing eaeA positive isolates for the presence of the stx2 gene [44,45]. The hlyA and stx1 genes were not identified in any E. coli recovered in the present study. This result contrasts with a recent study carried out in wild birds in Central Italy, which detected 3.3% and 8.3% of birds were positive for hlyA and stx1, respectively [46].

In the present study, 7.8%, 5.6%, and 1.1% of E. coli isolates carried blaCTX-M, blaTEM, and blaSHV genes, respectively. These results agree with several reports indicated the presence of ESBL-producing bacteria among migratory wild birds [47,48,49]. The alarming levels of ESBL-producing E. coli recovered from the present study were lower than that reported in wild birds in countries as Spain (74.8%), Netherlands (37.8%), England (27.1%), Sweden (20.7%), Latvia (17.4%) and Portugal (12.7%), and higher than that reported in Portugal (12.7%), Ireland (4.5%), Poland (0.7%), and Denmark (0.0%) [50]. Furthermore, about 8.9%, 4.4%, and 6.7% of the recovered E. coli isolates possess plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (qnrA), aminoglycosides resistance genes aac(3)-IV that encode acetyltransferases enzyme, and tetracycline resistance gene (tet(A)) that is often associated with mobile elements, respectively. Although our study design cannot confirm the source of ESBL-producing isolates that recovered in migratory wild birds, our results represent further evidence for the potential role of migratory wild birds in the global dissemination of ESBL that poses a serious challenge to the globe.

It should be noted that our study has two limitations. First, unequally collected samples from different wild bird species; second, there are no environmental samples collected. However, in a previous study, 86.7% of water samples collected from different Al-Ahsa water springs were positive for E. coli [40], indicating the central role of anthropogenic impact in the area where wild birds live, feed, and drink [39,51].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Area

The study was carried out in Al-Asfar Lake, located 13 km east of Al-Ahsa Oasis (N25 33 54, E49 50 15) Saudi Arabia. The lake extends over 2170 ha close to the Arabian Gulf. Al-Asfar Lake is an important bird area that provides shelter for a wide diversity of migratory wild birds, especially during the winter season. Al-Asfar Lake includes an alpine vegetation area with winding boundaries of watered areas followed by sandy surroundings. Varied bird species have been observed in the wetland, including large birds like ducks and geese to sparrows and small birds.

4.2. Birds and Sampling

Birds were captured within a 500 m radius vegetated area. The captured birds were described and named, according to Porter and Aspinall [52]. A pair of cloacal swabs were collected from each bird (a sterile swab was inserted into the captured bird’s cloaca and then rotated to take the fluid sample). The first swab was used for screening the avian influenza virus by a rapid test (FluDETECT™ Avian, Zoetis, Kalamazoo, MI, USA), and the second swab was stored in a sterile tube containing 5 mL of buffered peptone water (BPW; Oxoid, UK) for later bacteriological examination.

A total of 210 birds of different species, including Ruddy shelduck (Tadorna ferruginea; n = 70), Common pochard (Aythya ferina; n = 50), Pied avocet (Recurvirostra avosetta; n = 30), and Little grebe (Tachybaptus ruficollis; n = 60) were captured and sampled between January and December 2016. After sampling, all birds were allowed to fly to their natural habitat freely. All collected swabs were tested negative for avian influenza antigen by the rapid test and then transported in an icebox at 4 °C to the laboratory for bacteriological examination.

4.3. Bacterial Isolation and Identification

Tubes containing swabs and BPW were gently mixed. For isolation of E. coli and Staphylococcus spp., 100 μL from each tube was streaked onto each of MacConkey, Sorbitol MacConkey, and Baird-Parker (Oxoid, UK), then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Lactose fermenting colonies on MacConkey agar, white colonies on Sorbitol MacConkey agar, and black colonies on Baird–Parker agar were identified biochemically to species level by VITEK® 2 COMPACT (BioMérieux, France). For isolation of Salmonella, tubes containing BPW were enriched overnight aerobically at 37 °C, then incubated on Rappaport-Vassiliadis broth (Oxoid, UK) at 42 °C in aerobic conditions for 24 h, before inoculation on to xylose lysine deoxycholate agar (Oxoid, UK) and incubated under aerobic conditions at 37 °C for 24 h. Suspected colonies were identified biochemically by VITEK® 2 COMPACT (BioMérieux, France). Biochemically identified Salmonella isolates have been serologically confirmed on the basis of somatic (O) and flagellar (H) antigens by slide agglutination using commercial antisera (SISIN, Germany) following the Kauffman–White scheme [53].

For molecular conformation, bacterial DNA was extracted from biochemically identified E. coli, Salmonella, and Staphylococcus isolates for amplification and sequencing of 16S rRNA gene according to Lane [54] and Weisberg et al. [55].

4.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test

The standard disk diffusion test on Mueller Hinton agar (MHA) using cefotaxime (30 µg) and cefoxitin (30 µg) disk was performed according to the guidelines of the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [56] to identify extended-spectrum β-lactamase and methicillin-resistance bacteria, respectively. Two different sets of antimicrobials were selected for E. coli/Salmonella and Staphylococcus antimicrobials susceptibility testing. Antimicrobials include ampicillin (AMP), penicillin (PEN), amoxicillin-clavulanate (AMC), cefotaxime (CTX), oxacillin (OXA), imipenem (IPM), cefoxitin (FOX), kanamycin (KAN), gentamicin (GEN), doxycycline (DOX), ciprofloxacin (CIP), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT), chloramphenicol (CHL), erythromycin (ERY), clindamycin (CLI), and vancomycin (VAN). The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined by double fold dilution of antimicrobials (0.125–256 μg/mL) as recommended by the CLSI [56].

The dilutions and breakpoints were defined according to the CLSI [56]. Isolates were classified as resistant (R) or intermediate (I), or susceptible (S) based on the MIC breakpoint values. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) was considered when isolates were resistant to three or more different antimicrobial classes [57]. Furthermore, the MAR index was determined for all isolates according to the protocol described by Krumperma, [58] using the formula a/b (where “a” refers to the number of antimicrobials to which the isolate was resistant, and “b” represents the total number of antimicrobials to which the isolate was exposed).

4.5. Virulence and AMR Genes

The extracted DNA of E. coli isolates was amplified for identification of intimin (encoded by eaeA gene), enterohemolysin (encoded by hlyA gene), and Shiga toxins (encoded by stx1 and stx2 genes) [59,60]. AMR genes investigated were blaCTX-M, blaTEM, and blaSHV for extended-spectrum-β-lactamase (ESBL) [61,62]; aac(3)-IV and aadA1 for aminoglycosides resistance [63]; qnrA for quinolones resistance [64]; and tet(A) for tetracycline resistance [65].

For Staphylococcus isolates, the AMR gene investigated was the mecA gene for methicillin resistance [66]. In each PCR assay, positive and negative controls were used. The primers, the annealing temperature, and the expected size of the DNA product for each of the investigated genes are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Primers, product size, and annealing temperatures used for virulence and antimicrobial resistance genes identification in the present study.

| Gene | Primer Sequences | Product Size (bp) | Annealing (°C) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| stx1 | fw: 5′-AAATCGCCATTCGTTGACTACTTCT-3′ | 370 | 60 | [59] |

| rev: 5′-TGCCATTCTGGCAACTCGCGATGCA-3′ | ||||

| stx2 | fw: 5′-CAGTCGTCACTCACTGGTTTCATCA-3′ | 283 | 60 | [59] |

| rev: 5′-GGATATTCTCCCCACTCTGACACC-3′ | ||||

| hlyA | fw: 5′-GGTGCAGCAGAAAAAGTTGTAG-3′ | 1551 | 57 | [60] |

| rev: 5′-TCTCGCCTGATAGTGTTTGGTA-3′ | ||||

| eaeA | fw: 5′-CCCGAATTCGGCACAAGCATAAGC-3′ | 863 | 52 | [60] |

| rev: 5′-TCTCGCCTGATAGTGTTTGGTA-3′ | ||||

| blaCTX-M-I | fw: 5′-GACGATGTCACTGGCTGAGC-3′ | 499 | 55 | [62] |

| rev: 5′-AGCCGCCGACGCTAATACA- 3′ | ||||

| blaCTX-M-II | fw: 5′-GCGACCTGGTTAACTACAATCC-3′ | 351 | 55 | [62] |

| rev: 5′-CGGTAGTATTGCCCTTAAGCC -3′ | ||||

| blaCTX-M-III | fw: 5′-CGCTTTGCCATGTGCAGCACC -3′ | 307 | 55 | [62] |

| rev: 5′-GCTCAGTACGATCGAGCC -3′ | ||||

| blaCTX-M-IV | fw: 5′-GCTGGAGAAAAGCAGCGGAG-3′ | 474 | 62 | [62] |

| rev: 5′-GTAAGCTGACGCAACGTCTG -3′ | ||||

| blaTEM | fw: 5′-GAGTATTCAACATTTTCGT -3′ | 857 | 58 | [63] |

| rev: 5′-ACCAATGCTTAATCAGTGA -3′ | ||||

| blaSHV | fw: 5′-TCGCCTGTGTATTATCTCCC-3′ | 768 | 52 | [63] |

| rev: 5′-CGCAGATAAATCACCACAATG-3′ | ||||

| aac(3)-IV | fw: 5′-CTTCAGGATGGCAAGTTGGT-3′ | 286 | 55 | [63] |

| rev: 5′-TCATCTCGTTCTCCGCTCAT-3′ | ||||

| aadA1 | fw: 5′-TATCCAGCTAAGCGCGAACT-3′ | 447 | 58 | [63] |

| rev: 5′-ATTTGCCGACTACCTTGGTC-3′ | ||||

| qnrA | fw: 5′-GGGTATGGATATTATTGATAAAG-3′ | 670 | 50 | [64] |

| rev: 5′-CTAATCCGGCAGCACTATTTA-3′ | ||||

| tet(A) | fw: 5′-GGTTCACTCGAACGACGTCA-3′ | 577 | 57 | [65] |

| rev: 5′-CTGTCCGACAAGTTGCATGA-3′ | ||||

| mecA | fw: 5′-AAAATCGATGGTAAAGGTTGGC-3′ | 530 | 55 | [66] |

| rev: 5′-AG TTCTGCAGTACCGGATTTGC-3′ |

4.6. Data Analysis

Data were visualized with R software (R Core Team, 2019; version 3.5.3). A heatmap based on the isolate’s antimicrobial resistance profiles was built using the “Complex-Heatmap” R package [67]. Fisher’s exact test was used to identify the difference in E. coli resistance rate between migratory wild bird species. However, the correlation among antimicrobial MIC values for E. coli isolates recovered from each migratory wild bird species was assessed using the Spearman’s rank correlation test.

5. Conclusions

The higher bacterial recovery, antimicrobial resistance (phenotype, genotype, and MDR) from all samples collected from migratory wild birds around Al-Asfar Lake indicated environmental dissemination of antimicrobial resistance to wild birds that can maintain and spread the resistance bacteria along their migration route. That mirroring human activity and its impact on the environment. Migratory wild bird feeding and inhabitant habits are the main driving force of antimicrobial resistance in different wild bird species, explaining why certain migratory wild bird species can acquire, share in selection pressure, and disseminate the antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Although all available evidence in the present study ensures the implication of contaminated water in AMR incidence in migratory wild birds, it cannot rule out other sources including the abroad one. This highlights the importance of collecting samples from different environmental samples from and around the lake along with samples from water from irrigation canals and treated wastewater from nearby sewage stations to conduct a co-occurring network analysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Taif University Researchers Supporting Program (Project number: TURSP-2020/57), Taif University, Saudi Arabia for their support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.E., A.S., A.E. (Ahmed Elmoslemany) and M.F.; methodology, I.E., A.S., A.E. (Ahmed Elmoslemany), M.A. (Mohammed Alorabi) and M.F.; software, I.E.; validation, I.E., A.S., A.E. (Ahmed Elmoslemany) and M.F.; formal analysis, I.E., A.S., A.E. (Ahmed Elmoslemany) and M.F.; investigation, A.A., T.A.-M., M.A. (Mohammed Alorabi), A.E. (Ayman Elbehiry) and M.F.; resources A.A., T.A.-M., M.A. (Mohammed Alorabi), A.E. (Ayman Elbehiry) and M.F.; data curation, A.A., T.A.-M., M.A. (Mohammed Alorabi), A.E. (Ayman Elbehiry) and M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, I.E., A.S. and M.F.; writing—review and editing, I.E., A.S., A.E. (Ahmed Elmoslemany) and M.F.; visualization, I.E.; supervision, M.F.; project administration, M.A. (Mohamed Alkafafy); funding acquisition, M.A. (Mohamed Alkafafy). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Taif University Researchers Supporting Project number (TURSP-2020/57), Taif University, P.O. Box 11099, Taif 21944, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Taif University Ethics Committee has approved the study protocol (TURSP-2020-57).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wang J., Ma Z.-B., Zeng Z.-L., Yang X.-W., Huang Y., Liu J.-H. The role of wildlife (wild birds) in the global transmission of antimicrobial resistance genes. Zool. Res. 2017;38:55. doi: 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2017.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berthold P. Bird Migration: A General Survey. Oxford University Press on Demand; Oxford, UK: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guenther S., Aschenbrenner K., Stamm I., Bethe A., Semmler T., Stubbe A., Stubbe M., Batsajkhan N., Glupczynski Y., Wieler L.H. Comparable high rates of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in birds of prey from Germany and Mongolia. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e53039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nielsen E.M., Skov M.N., Madsen J.J., Lodal J., Jespersen J.B., Baggesen D.L. Verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli in wild birds and rodents in close proximity to farms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:6944–6947. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6944-6947.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reed K.D., Meece J.K., Henkel J.S., Shukla S.K. Birds, migration and emerging zoonoses: West Nile virus, Lyme disease, influenza A and enteropathogens. Clin. Med. Res. 2003;1:5–12. doi: 10.3121/cmr.1.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brittingham M.C., Temple S.A., Duncan R.M. A survey of the prevalence of selected bacteria in wild birds. J. Wildl. Dis. 1988;24:299–307. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-24.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waldenström J., Broman T., Carlsson I., Hasselquist D., Achterberg R.P., Wagenaar J.A., Olsen B. Prevalence of Campylobacter jejuni, Campylobacter lari, and Campylobacter coli in different ecological guilds and taxa of migrating birds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:5911–5917. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.12.5911-5917.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benskin C.M.H., Wilson K., Jones K., Hartley I.R. Bacterial pathogens in wild birds: A review of the frequency and effects of infection. Biol. Rev. 2009;84:349–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsiodras S., Kelesidis T., Kelesidis I., Bauchinger U., Falagas M.E. Human infections associated with wild birds. J. Infect. 2008;56:83–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prestinaci F., Pezzotti P., Pantosti A. Antimicrobial resistance: A global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog. Glob. Health. 2015;109:309–318. doi: 10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu J., Huang Y., Rao D., Zhang Y., Yang K. Evidence for environmental dissemination of antibiotic resistance mediated by wild birds. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:745. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanco G., López-Hernández I., Morinha F., López-Cerero L. Intensive farming as a source of bacterial resistance to antimicrobial agents in sedentary and migratory vultures: Implications for local and transboundary spread. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;739:140356. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Boeckel T.P., Brower C., Gilbert M., Grenfell B.T., Levin S.A., Robinson T.P., Teillant A., Laxminarayan R. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:5649–5654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503141112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skurnik D., Ruimy R., Andremont A., Amorin C., Rouquet P., Picard B., Denamur E. Effect of human vicinity on antimicrobial resistance and integrons in animal faecal Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006;57:1215–1219. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knapp C.W., Dolfing J., Ehlert P.A., Graham D.W. Evidence of increasing antibiotic resistance gene abundances in archived soils since 1940. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44:580–587. doi: 10.1021/es901221x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin Y., Dong X., Sun R., Wu J., Tian L., Rao D., Zhang L., Yang K. Migratory birds-one major source of environmental antibiotic resistance around Qinghai Lake, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;739:139758. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hussein A.H., El Mahmoudi A.S., Al Naeem A.A. Assessment of the Heavy Metals in Al Asfar Lake, Al-Hassa, Saudi Arabia. Water Environ. Res. 2016;88:142–151. doi: 10.2175/106143015X14362865227913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole D., Drum D., Stalknecht D.E., White D.G., Lee M.D., Ayers S., Sobsey M., Maurer J.J. Free-living Canada geese and antimicrobial resistance. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005;11:935–938. doi: 10.3201/eid1106.040717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozak G.K., Boerlin P., Janecko N., Reid-Smith R.J., Jardine C. Antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli isolates from swine and wild small mammals in the proximity of swine farms and in natural environments in Ontario, Canada. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:559–566. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01821-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atterby C., Ramey A.M., Hall G.G., Järhult J., Börjesson S., Bonnedahl J. Increased prevalence of antibiotic-resistant E. coli in gulls sampled in Southcentral Alaska is associated with urban environments. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2016;6:32334. doi: 10.3402/iee.v6.32334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang W., Zheng S., Sharshov K., Sun H., Yang F., Wang X., Li L., Xiao Z. Metagenomic profiling of gut microbial communities in both wild and artificially reared Bar-headed goose (Anser indicus) Microbiol. Open. 2017;6:e00429. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramey A.M., Hernandez J., Tyrlöv V., Uher-Koch B.D., Schmutz J.A., Atterby C., Järhult J.D., Bonnedahl J. Antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli in migratory birds inhabiting remote Alaska. EcoHealth. 2018;15:72–81. doi: 10.1007/s10393-017-1302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcelino V.R., Wille M., Hurt A.C., González-Acuña D., Klaassen M., Schlub T.E., Eden J.-S., Shi M., Iredell J.R., Sorrell T.C. Meta-transcriptomics reveals a diverse antibiotic resistance gene pool in avian microbiomes. BMC Biol. 2019;17:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12915-019-0649-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abo-Amer A.E., Shobrak M.Y. Antibiotic resistance and molecular characterization of Enterobacter cancerogenus isolated from wild birds in Taif province, Saudi Arabia. Thai J. Vet. Med. 2015;45:101. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albeshr M.F., Alrefaei A.F. Isolation and characterization of novel Trichomonas gallinae ribotypes infecting Domestic and Wild birds in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Avian Dis. 2020;64:130–134. doi: 10.1637/0005-2086-64.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alharbi N.S. Escherichia coli in Saudi Arabia: An Overview of Antibiotic-Resistant Strains. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Asia. 2020;17:443–457. doi: 10.13005/bbra/2848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonnedahl J., Järhult J.D. Antibiotic resistance in wild birds. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2014;119:113–116. doi: 10.3109/03009734.2014.905663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zurfluh K., Albini S., Mattmann P., Kindle P., Nüesch-Inderbinen M., Stephan R., Vogler B.R. Antimicrobial resistant and extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Escherichia coli in common wild bird species in Switzerland. Microbiol. Open. 2019;8:e845. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shobrak M.Y., Abo-Amer A.E. Role of wild birds as carriers of multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli and Escherichia vulneris. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2014;45:1199–1209. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822014000400010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ong K.H., Khor W.C., Quek J.Y., Low Z.X., Arivalan S., Humaidi M., Chua C., Seow K.L., Guo S., Tay M.Y. Occurrence and antimicrobial resistance traits of Escherichia coli from wild birds and rodents in Singapore. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:5606. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aung K.T., Chen H.J., Chau M.L., Yap G., Lim X.F., Humaidi M., Chua C., Yeo G., Yap H.M., Oh J.Q. Salmonella in retail food and wild birds in Singapore—Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, and sequence types. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:4235. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16214235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martín-Maldonado B., Vega S., Mencía-Gutiérrez A., Lorenzo-Rebenaque L., de Frutos C., González F., Revuelta L., Marin C. Urban birds: An important source of antimicrobial resistant Salmonella strains in Central Spain. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020;72:101519. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2020.101519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tizard I. Salmonellosis in wild birds. Semin. Avian Exot. Pet Med. 2004;13:50–66. doi: 10.1053/j.saep.2004.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abulreesh H.H., Goulder R., Scott G.W. Wild birds and human pathogens in the context of ringing and migration. Ringing Migr. 2007;23:193–200. doi: 10.1080/03078698.2007.9674363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berendonk T.U., Manaia C.M., Merlin C., Fatta-Kassinos D., Cytryn E., Walsh F., Bürgmann H., Sørum H., Norström M., Pons M.-N. Tackling antibiotic resistance: The environmental framework. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015;13:310–317. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hassan S.A., Shobrak M.Y. Detection of genes mediating beta-lactamase production in isolates of enterobacteria recovered from wild pets in Saudi Arabia. Vet. World. 2015;8:1400. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2015.1400-1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collignon P.C., Conly J.M., Andremont A., McEwen S.A., Aidara-Kane A., World Health Organization Advisory Group, Bogotá Meeting on Integrated Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance (WHO-AGISAR) Agerso Y., Andremont A., Collignon P., Conly J., et al. World Health Organization ranking of antimicrobials according to their importance in human medicine: A critical step for developing risk management strategies to control antimicrobial resistance from food animal production. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;63:1087–1093. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Costa D., Poeta P., Sáenz Y., Vinué L., Rojo-Bezares B., Jouini A., Zarazaga M., Rodrigues J., Torres C. Detection of Escherichia coli harbouring extended-spectrum β-lactamases of the CTX-M, TEM and SHV classes in faecal samples of wild animals in Portugal. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006;58:1311–1312. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dolejska M., Masarikova M., Dobiasova H., Jamborova I., Karpiskova R., Havlicek M., Carlile N., Priddel D., Cizek A., Literak I. High prevalence of Salmonella and IMP-4-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the silver gull on Five Islands, Australia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016;71:63–70. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alzahrani A.M., Gherbawy Y.A. Antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli strains isolated from water springs in Al-Ahsa Region. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2011;5:123–130. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martinez J., Baquero F. Mutation frequencies and antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1771–1777. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.7.1771-1777.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maiden M.C. Horizontal genetic exchange, evolution, and spread of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998;27:S12–S20. doi: 10.1086/514917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kobayashi H., Kanazaki M., Hata E., Kubo M. Prevalence and characteristics of eae-and stx-positive strains of Escherichia coli from wild birds in the immediate environment of Tokyo Bay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:292–295. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01534-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koochakzadeh A., Askari Badouei M., Zahraei Salehi T., Aghasharif S., Soltani M., Ehsan M. Prevalence of Shiga toxin-producing and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in wild and pet birds in Iran. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2015;17:445–450. doi: 10.1590/1516-635X1704445-450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prager R., Fruth A., Siewert U., Strutz U., Tschäpe H. Escherichia coli encoding Shiga toxin 2f as an emerging human pathogen. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2009;299:343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bertelloni F., Lunardo E., Rocchigiani G., Ceccherelli R., Ebani V.V. Occurrence of Escherichia coli virulence genes in feces of wild birds from Central Italy. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2019;12:142. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pinto L., Radhouani H., Coelho C., da Costa P.M., Simões R., Brandão R.M., Torres C., Igrejas G., Poeta P. Genetic detection of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-containing Escherichia coli isolates from birds of prey from Serra da Estrela natural reserve in Portugal. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:4118–4120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02761-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Veldman K., van Tulden P., Kant A., Testerink J., Mevius D. Characteristics of cefotaxime-resistant Escherichia coli from wild birds in the Netherlands. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79:7556–7561. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01880-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schaufler K., Semmler T., Wieler L.H., Wöhrmann M., Baddam R., Ahmed N., Müller K., Kola A., Fruth A., Ewers C. Clonal spread and interspecies transmission of clinically relevant ESBL-producing Escherichia coli of ST410—another successful pandemic clone? Fems Microbiol. Ecol. 2016;92:fiv155. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiv155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stedt J., Bonnedahl J., Hernandez J., Waldenström J., McMahon B.J., Tolf C., Olsen B., Drobni M. Carriage of CTX-M type extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) in gulls across Europe. Acta Vet. Scand. 2015;57:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13028-015-0166-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dolejska M., Literak I. Wildlife is overlooked in the epidemiology of medically important antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e01167-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01167-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Porter R., Aspinall S. Birds of the Middle East. Bloomsbury Publishing; London, UK: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Popoff M.Y., Bockemühl J., Gheesling L.L. Supplement 2002 (no. 46) to the Kauffmann–White scheme. Res. Microbiol. 2004;155:568–570. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lane D.J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E., Goodfellow M., editors. Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematic. John Wiley and Sons; New York, NY, USA: 1991. pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weisburg W.G., Barns S.M., Pelletier D.A., Lane D.J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/JB.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wayne P.A. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: Twenty-fourth informational supplement, M100-S24. Clin. Lab. Stand. Inst. (CLSI) 2014;34:100–121. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Magiorakos A.-P., Srinivasan A., Carey R.T., Carmeli Y., Falagas M.T., Giske C.T., Harbarth S., Hindler J.T., Kahlmeter G., Olsson-Liljequist B. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012;18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krumperman P.H. Multiple antibiotic resistance indexing of Escherichia coli to identify high-risk sources of fecal contamination of foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983;46:165–170. doi: 10.1128/AEM.46.1.165-170.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brian M., Frosolono M., Murray B., Miranda A., Lopez E., Gomez H., Cleary T. Polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli infection and hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992;30:1801–1806. doi: 10.1128/JCM.30.7.1801-1806.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gallien P. PCR Detection of Microbial Pathogens. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2003. Detection and Subtyping of ShigaToxin-Producing Escherichia coli (STEC) pp. 163–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pitout J., Thomson K., Hanson N.D., Ehrhardt A., Moland E., Sanders C. β-Lactamases responsible for resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins in Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Proteus mirabilis isolates recovered in South Africa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1350–1354. doi: 10.1128/AAC.42.6.1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pitout J.D., Hossain A., Hanson N.D. Phenotypic and molecular detection of CTX-M-β-lactamases produced by Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:5715–5721. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5715-5721.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van T.T.H., Chin J., Chapman T., Tran L.T., Coloe P.J. Safety of raw meat and shellfish in Vietnam: An analysis of Escherichia coli isolations for antibiotic resistance and virulence genes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008;124:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mammeri H., Van De Loo M., Poirel L., Martinez-Martinez L., Nordmann P. Emergence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in Escherichia coli in Europe. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:71–76. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.1.71-76.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Randall L., Cooles S., Osborn M., Piddock L., Woodward M.J. Antibiotic resistance genes, integrons and multiple antibiotic resistance in thirty-five serotypes of Salmonella enterica isolated from humans and animals in the UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004;53:208–216. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Murakami K., Minamide W., Wada K., Nakamura E., Teraoka H., Watanabe S. Identification of methicillin-resistant strains of staphylococci by polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1991;29:2240–2244. doi: 10.1128/JCM.29.10.2240-2244.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gu Z., Eils R., Schlesner M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:2847–2849. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.