Abstract

The genus Trypanosoma includes flagellated protozoa belonging to the family Trypanosomatidae (Euglenozoa, Kinetoplastida) that can infect humans and several animal species. The most studied species are those causing severe human pathology, such as Chagas disease in South and Central America, and the human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), or infections highly affecting animal health, such as nagana in Africa and surra with a wider geographical distribution. The presence of these Trypanosoma species in Europe has been thus far linked only to travel/immigration history of the human patients or introduction of infected animals. On the contrary, little is known about the epidemiological status of trypanosomes endemically infecting mammals in Europe, such as Trypanosoma theileri in ruminants and Trypanosoma lewisi in rodents and other sporadically reported species. This brief review provides an updated collection of scientific data on the presence of autochthonous Trypanosoma spp. in mammals on the European territory, in order to support epidemiological and diagnostic studies on Trypanosomatid parasites.

Keywords: Trypanosoma spp., mammals, Europe, epidemiology, T. theileri, T. lewisi, T. grosi

1. Introduction

The genus Trypanosoma includes flagellated protozoans belonging to the Trypanosomatidae family (Euglenozoa, Kinetoplastea) that can infect humans and several animal species [1]. They are mostly dixenous parasites, meaning that the presence of two hosts (commonly one vertebrate and one invertebrate) is required in order to complete their life cycle. Such organisms are capable of parasitizing a wide range of vertebrate hosts, from mammals to birds, fish, amphibians, and reptiles [2].

The most studied species are those causing serious diseases in humans, and are not endemic in the European continent. This group includes species of the Trypanosoma brucei complex, mainly responsible for African trypanosomiasis [3], which are usually transmitted cyclically through a salivarian route by the tsetse fly (Glossina spp.), or rarely by congenital transmission [4]. In particular, the subspecies T. brucei gambiense and T. brucei rhodesiense are responsible for human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), also known as sleeping sickness, which can result in death of the patient if untreated [5,6]. A variety of wild and domestic animal species may act as reservoir in endemic countries, especially for T. brucei rhodesiense [7,8]. In Europe, the diagnosis of HAT is usually related to travel or migration [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18], with some differences concerning the species isolated; in general, rhodesiense HAT is more connected with tourism, particularly with travelers returning from short visits to endemic countries, and is the most frequently diagnosed, while gambiense HAT patients had been living in endemic countries for extended period, and therefore is more related to history of migration with economic connections to the endemic countries [18,19].

Moreover, T. cruzi is responsible for human American trypanosomiasis, the Chagas disease, typically acquired through stercorarian transmission by triatomine bugs (reduviid insects) vector species, although vertical and iatrogenic transmission are also described [20]. The Chagas disease is endemic in Central and South America, where it has also been described in more than 100 animal species, whose role as reservoir is well established [21,22,23]. A large number of cases have also been reported in Europe, both in travelers and, in particular, in migrants from endemic countries; this phenomenon has increased particularly since the 1990s due to massive migrations from Latin America to Italy, Portugal, and Spain [20,24,25,26,27], as well as to other European countries such as Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom [28].

In domestic animals, animal African trypanosomiasis (AAT, also named nagana) is described as an acute or chronic disease caused by several species of Trypanosoma including T. brucei subsp. brucei, T. vivax, T. congolense, T. simiae, and T. suis [7]. These trypanosomes are cyclically transmitted by tsetse fly, although T. congolense and T. vivax might be mechanically transmitted by Tabanids and Stomoxines [29]. Although evidence for the epidemiological relevance of theirmechanical transmission in Africa are scant, such route has allowed these species to expand their range beyond that of Glossina spp. In particular, T. vivax has expanded its distribution to South and parts of Central America during European colonization in the last centuries [30]. In Europe, autochthonous cases of nagana have not been described thus far [31,32]. Clinical manifestations may vary according to the species; in particular, T. congolense present in Sub-Saharan Africa causes large economical losses in endemic countries [3].

Concerning other animal trypanosomes, such as T. brucei evansi and T. brucei equiperdum, the possibility of spreading in Europe is different. Classification of these species (previously named as T. evansi and T. equiperdum [2]) is still subject of debate; since they share important morphological and genetic traits, both parasites should be considered subspecies of T. brucei [33,34,35]. T. brucei evansi is the causative agent of the animal disease surra, which can affect a wide range of mammals from different geographical areas—camels, horses, buffalos, and cattle are particularly affected, although other animals, including wildlife, are also susceptible. Being transmitted in a non-cyclic way by tabanids, other flies, vampire bats, or carnivores, surra’s spatial distribution is wide, including Africa, Asia, and Latin America [36]. T. brucei evansi has been known to be present since 1997 in the Canary Islands [37,38], where the most important population of dromedary camel (Camelus dromedarius) in Europe is present [39], and Stomoxys calcitrans is commonly involved in its transmission in the archipelago [40]. In 2010, following control programs, in the island of Gran Canaria, about 5% of the camelid population remained positive [40], and it was supposed that small ruminants, rodents, or rabbits could play a role as reservoirs of infection, although no evidence of the parasite in rodents was found [41]. Surra outbreaks have also been reported in dromedary camels and equids (horses and donkeys) from mainland Spain and France following importation of camelids from Canary Island [39,42]; nevertheless, in these cases, sanitary measures were successful in controlling the disease [40]. Furthermore, a single case of Surra was described in Germany in a Jack Russel dog imported from Thailand [43]. Further outbreaks in continental Europe have not been reported. Surveillance measures should be considered by European Countries for current risk of introduction; however, according to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), it is currently inconclusive whether T. brucei evansi infections (including surra) can be considered eligible to be listed for Union intervention in Animal Health Law [44].

T. brucei equiperdum, the causative agent of dourine in equids, represents an exception amongst trypanosomes, being the only species transmitted directly between hosts through coitus [45]. Dourine was anciently described in North Africa, but the etiological agent was first isolated only at the beginning of the last century by Buffard and Schneider [46]. In Europe, the disease has been described from the XVIII century in Russia, as well as in France, due to introduction of Persian, and Syrian and Spanish stallions, respectively [2]. After the Second World War, the disease spread in Europe, but thanks to several control efforts aimed at eradicating dourine, the disease disappeared from western and central European countries [47]. Although sporadic outbreaks were reported in the 1970s in Italy, dourine remained unreported until 2011, when five outbreaks were confirmed, once again in Italy [48,49]. Such disease is still considered a relevant health issue for equines and represents a trade barrier in the movement of horses [50]; since it needs no vector for its transmission and can spread with the host, it requires implementation of official control plans [51].

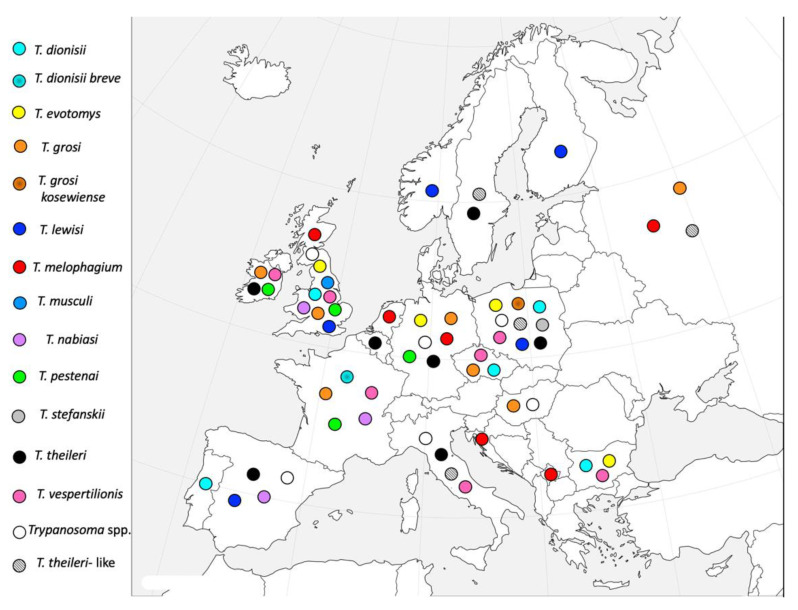

Along with these well-known and studied species, other Trypanosoma spp. can infect mammals, and some of them are also diffused in Europe. The aim of this brief review was to gather reports of findings of these neglected species in Europe in order to raise awareness on the presence if these flagellates during epidemiological and diagnostic studies on trypanosomatid parasites on the European territory (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the autochthonous Trypanosoma species in European mammals.

2. General Taxonomy of the Genus Trypanosoma

In order to properly define the distribution of Trypanosoma spp. in Europe, we deemed a brief section concerning the classification of this genus to be opportune.

As previously mentioned, trypanosomes are obligate parasites belonging to the Protozoa subkingdom, phylum Euglenozoa, class Kinetoplastea, order Trypanosomatida [1,52]. Kinetoplastea are characterized by the presence of a modified mitochondrion containing a body constituted of a disc-shaped, DNA-containing organelle, known as kinetoplast (from which the class name is derived), located beside the kinetosome at the base of the flagellum [53]. The classification of the Trypanosomatidae family is extremely complicated and still subject of debate amongst parasitologists for several reasons, among which the lack of morphological differences between phylogenetically distinct taxa and of an unequivocal classification approach [1,54].

The genus Trypanosoma is usually classified in the Blechomonadinae subfamily, which predominantly hosts dixenous parasites [55] and is conventionally divided in two groups on the basis of the replication site inside the invertebrate host “Salivaria”, which develops in the foregut and is transmitted by inoculation, and “Stercoraria”, which develops in the hindgut and therefore is transmitted by fecal contamination of skin injuries or mucosae [56]. Although this classification is not strictly taxonomic, it is still widely used because easily recalls life cycle and infection route of trypanosomes and will be also utilized in this review. In mammalian host, the salivarian trypanosomes reproduce in the trypomastigote stage that has the kinetoplast in terminal or subterminal position and blunt posterior end. The Salivaria group includes four subgenera: Duttonella, Nannomonas, Pycnomonas, and Trypanozoon, mainly transmitted by tsetse flies [3,57]. Slight morphological differences between the subgenera have been described: Duttonella has rounded posterior end with large and terminal kinetoplast, Nannomonas has the kinetoplast in marginal position, while Pycnomonas has small and subterminal kinetoplast [58]. Assuming the progressive adaptation of trypanosomes to the tsetse fly as indicative of evolution, researchers have considered the subgenus Duttonella (non-cyclic) as the most ancient, and Trypanozoon the most recent [56,59,60]. The Duttonella subgenus includes T. vivax, responsible for nagana diseases in various animal species in Africa, or asymptomatic infections in Central and South America [61]. Concerning the subgenus Nannomonas, it includes species of interest in animal health such as Trypanosoma simiae, Trypanosoma godfreyi, and Trypanosoma congolense, also causing nagana in animals [62]. Pycnomonas subgenus includes T. suis, causing nagana in Suidae in Africa [63]. The Trypanozoon subgenus comprises cyclically transmitted trypanosomes extremely relevant for human and animal health, such as T. brucei complex, including T. brucei brucei, also an agent of nagana disease in animals in Africa, and the HAT causal agents T. brucei rhodesiense and T. brucei gambiense [64]. Moreover, this subgenus includes T. brucei evansi, which causes Surra in a wide range of hosts, and the monoxenous sexually transmitted T. brucei equiperdum [36,65].

The Stercoraria group comprises protozoans that, in the mammalian host, reproduce as epimastigote/amastigote forms, and present not reproducing trypomastigote forms in blood. The latter ones have a large kinetoplast, usually not terminal, and pointed end of the body. Stercoraria are mostly considered as non-pathogenic (except for T. cruzi) and comprise different subgenera [66]: (i) Schizotrypanum, with trypomastigotes typically curved with kinetoplast close to the posterior end of the body, includes T. cruzi responsible for Chagas disease or human American trypanosomiasis [67,68]; (ii) Megatrypanum are large trypanosomes that in trypomastigote forms have kinetoplast near the nucleolus, far from the posterior end [58] and include, amongst others, the worldwide distributed cyclic species Trypanosoma melophagium in sheep and Trypanosoma theileri in cattle [2]; (iii) Herpetomonas, defined as subgenus by Molyneux [69], includes Trypanosoma lewisi as the most studied species, long isolated in rodents worldwide and lately occasionally reported also in humans in Asia and Africa [70,71]. The trypomatigote forms are medium-sized with slender curved body and pronounced free flagellum [2].

According to data based on molecular sequences retrieved from GenBank (non-taxonomic), we found that not all trypanosomes can be classified according to these subgenera; therefore, in this classification, two clades have been introduced: firstly, the clade of “Trypanosoma with unspecified subgenus”, in which some parasites of wild fauna, such as Trypanosoma evotomys, Trypanosoma grosi, Trypanosoma nabiasi, and Trypanosoma pestanai, are included. Such parasites are commonly defined as non-pathogenic, as they have rarely been isolated in course of clinical disease. Unexpectedly, according to phylogenetic analysis, T. theileri belongs to this clade, although it is taxonomically included in the Megatrypanum subgenus. The second clade with no specific subgenus is referred to as “unclassified trypanosomes”, further subdivided into “fish trypanosomes” and “other trypanosomes”; the latter includes recently discovered trypanosomes waiting for proper classification. Table 1 reports a schematic classification of Trypanosoma spp. on the basis of data retrieved from GenBank taxonomy [72].

Table 1.

Classification scheme of the Trypanosoma species as retrieved from GenBank taxonomy (25 January 2021), modified by referring them also to Salivaria and Stercoraria groups.

| Group | Subgenus/Clade | Species | Subspecies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salivaria | Duttonella | T. vivax | |

| Nannomonas | T. congolese | ||

| T. godfreyi | |||

| T. simiae | |||

| Pycnomonas | T. suis | ||

| Trypanozoon | T. brucei | T. brucei brucei | |

| T. brucei gambiense | |||

| T. brucei rhodensiense | |||

| T. brucei equiperdum | |||

| T. brucei evansi | |||

| Stercoraria | Herpetosoma | T. lewisi | |

| T. rangeli | |||

| Megatrypanum | T. melophagium | ||

| Schizotrypanum | T. cruzi | ||

| T. dionisii | T. dionisii breve | ||

| T. vespertilionis | |||

| Trypanosomes with unspecified subgenus | T. evotomys | ||

| T. grayi | |||

| T. grosi | T. grosi kosewiense | ||

| T. pestenai | |||

| T. theileri | |||

| T. nabiasi | |||

| Unclassified trypanosomes | Fish trypanosomes | ||

| Other unclassified trypanosomes |

3. Trypanosoma Species Naturally Occurring in Domestic and Wild Mammals in Europe

As seen in the literature, a wide variety of Trypanosoma species have been reported to infect mammals from all European Countries (Table 2). Such species are commonly reported as non-pathogenic trypanosomes. In general, certain characteristics usually distinguish non-pathogenic trypanosome species from the pathogenic ones: (i) the host–parasite relationships are well adapted evolutionarily to both vertebrate and invertebrate host; (ii) infection rates in vectors are high; (iii) infected mammals are usually healthy carriers with inapparent, nonchronic infections; (iv) the host range is extremely restricted; (v) in an invertebrate host, the development of metacyclic trypomastigote occurs in the hindgut and the parasites are shed with the feces; (vi) in the mammalian host, trypanosomes shortly reproduce as epimastigote and/or amastigote forms, after which non-reproductive trypomastigote forms circulate in blood [66]. The only exception to this classification scheme is T. cruzi, which is not naturally present in Europe and, although included in the Stercoraria group, is highly pathogenic.

Table 2.

Trypanosoma spp. naturally occurring in domestic and wild mammals and in vectors in Europe.

| Trypanosoma sp. | Country | Host | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| T. dionisii | Bulgaria | Bat and bat flies (Nycteribia shmidlii) | [73] |

| Czech Republic | Bat and bat flies | [73] | |

| Poland | Bat and bat flies | [73] | |

| Portugal | Bat | [74] | |

| United Kingdom | Bat and bat flies | [75] | |

| T. dionisii breve | France | Bat | [76] |

| T. evotomys | Bulgaria | Mus macedonicus | [77] |

| Germany | Voles | [78,79] | |

| United Kingdom | Voles | [69,80,81,82,83] | |

| Poland | Voles | [84,85] | |

| T. grosi | Czech Republic | Apodemus agrarius | [86] |

| France | Apodemus sylvaticus | [87] | |

| Germany | Voles | [88] | |

| Hungary | Voles | [89] | |

| Ireland | Small rodents | [90] | |

| United Kingdom | Small rodents | [80,82,90] | |

| Russia | Apodemus sylvaticus | [91,92] | |

| T. grosi kosewiense | Poland | Voles | [93] |

| T. lewisi | Finland | Rattus norvegicus, R. rattus | [94] |

| Norway | Clethrionomys glareolus, Microtus agrestis; Apodemus sylvaticus | [95] | |

| Poland | Rattus norvegicus | [96] | |

| United Kingdom | Rattus norvegicus | [82] | |

| Spain | Rattus norvegicus, R. rattus | [41] | |

| T. melophagium | Croatia | Sheep ked (Mallophagus melophagium) | [97] |

| Germany | Sheep ked | [98] | |

| Sheep | [99,100] | ||

| Holland | Sheep | [101] | |

| Russia | Sheep | [102] | |

| United Kingdom | Sheep | [103,104,105,106] | |

| Sheep ked | [107] | ||

| Former Yugoslavia (Croatia and Kosovo) | Sheep | [108] | |

| T. musculi | United Kingdom | Mouse (Mus musculus) | [82] |

| T. nabiasi | France | Wild and domestic rabbits | [109] |

| Spain | Rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) | [110,111] | |

| United Kingdom | Rabbits | [112] | |

| T. pestenai | France | European badger (Meles meles) | [113,114] |

| Germany | Dog | [115] | |

| Ireland | Badger | [116] | |

| United Kingdom | Badger | [117,118,119,120,121] | |

| T. stefanskii | Poland | Roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) | [122] |

| T. theileri | Belgium | Cattle | [123] |

| Germany | Cattle | [124,125] | |

| Fallow deer (Dama dama), red deer (Cervus elaphus), roe deer | [126,127] | ||

| Italy | Cattle | [128] | |

| River buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) | [129] | ||

| Ireland | Calf | [130] | |

| Poland | Cattle | [131] | |

| European bison (Bison bonasus) | [132,133,134,135] | ||

| Sweden | Cattle | [122] | |

| Spain | Cattle | [136,137] | |

| T. vespertilionis | Bulgaria | Bat and bat flies | [73] |

| Czech Republic | Bat and bat flies | [73] | |

| France | Bat | [138] | |

| Italy | Bat | [139,140,141] | |

| Ireland | Bat | [142] | |

| Poland | Bat and bat flies | [73] | |

| United Kingdom | Bat | [143,144,145] | |

| Bat and bat flies | [75] | ||

| T. theileri-like | Italy | Sandflies (Phlebotomus perfiliewi) | [146] |

| Poland | Deer ked (Lipoptena fortisetosa and L. cervi) | [147] | |

| Sweden | Roe deer, fallow deer, European elk, red deer, wild boar (Sus scrofa) | [148] | |

| Russia | Horseflies (Hybomitra tarandina, H. muehlfeldi, H. bimaculate, Chrysops divaricatus) | [149] | |

| Trypanosoma sp. | Germany | Fallow deer, red deer, roe deer | [150,151] |

| Italy | Bat and Cimex spp. | [152] | |

| Hungary | Bat and Cimex spp. | [152] | |

| Poland | Roe deer, red deer, European elk (Alces alces) | [153] | |

| Roe deer | [154] | ||

| Spain | Bat and Cimex spp. | [152] | |

| Red deer | [155] | ||

| Wild rabbits | [156] | ||

| United Kingdom | Common shrews (Sorex araneus) | [157] | |

| Cattle | [114,158,159] |

3.1. Trypanosoma theileri

While drafting this review, the presence of T. theileri Laveran, 1902 has shown great relevance in Europe. As previously mentioned, this species is usually classified in the Megatrypanum subgenus, however, in terms of phylogenetic analysis, it is grouped within the “Trypanosoma with unspecified subgenus”. T. theileri is considered a mildly pathogenic species that typically infects wild and domestic ruminants [131]. Different tabanid species are common vectors of T. theileri, transmitting the pathogen by laying infected feces on the skin of the mammalian host or by ingestion of infected insects [127]; however, during a study concerning Leishmania infantum in the Emilia-Romagna region (Italy), the presence of T. theileri-like trypanosomes has been recently reported in sandflies (Phlebotomus spp.) [149], although their role as vectors has not been established. Exploiting abraded skin or mucosae, T. theileri invades the bloodstream of the mammalian host; prepatent period ranges from 4 to 20 days and parasitemia decreases after 2–4 weeks [66]. First isolation was performed in Africa by the veterinary bacteriologist Arnold Theiler, who observed animals with clinical manifestations similar to the “Gall-sickness” (currently Anaplasmosis) during immunization of cattle against rinderpest. He observed Trypanosoma-like forms in blood smears and sent them to French and British researchers (Laveran and Bruce, respectively), who both named the parasite as T. theileri; however, since Laveran published the description earlier, the species was credited to him [2,160,161]. After the first isolation, reports have been numerous but often incorrect due to the great morphological variability of strains isolated from different animal hosts and geographical areas. In fact, several authors named different new species (e.g., Trypanosoma frank from cattle in Germany, Trypanosoma wrublewskii from the European bison Bison bonasu in Poland, Trypanosoma americanum and Trypanosoma rutherfordi from cattle in North America [2]), which were lately recognized as T. theileri by Herbert [162], making it clear that its distribution was wider than the African continent. Until 1970, reports of T. theileri in cattle ranged from Australia [163], to the United Kingdom [158,159], to the USA and Canada [164,165]. Concerning Europe, this species has more recently been reported from cattle also in Belgium, Germany, Italy, Ireland, Poland, and Spain [123,124,128,130,131,137]. Although these infections are generally reported as asymptomatic, clinical manifestations have sometimes been described, as primarily referred by Theiler [161]. Cases of illness were reported mostly in immunocompromised animals consisting of mild leukocytosis, enlargement of the spleen, anemia, weight loss, and considerable drop in milk production, especially if the infection concurs with bovine leukemia virus [128,129,130,131]. Water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) is also susceptible to infection, and recent casual findings have been described in Italy in both cattle and water buffalo [128,129], whereas, in Poland, reports in European bison are numerous [132,133,134,135].

In Europe, Megatrypanum species, often morphologically described as T. theileri-like, were also reported in wild ruminants such as roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), fallow deer (Dama dama), and red deer (Cervus elaphus) [114,148,150,151,152,153,154,166]. T. theileri-like strains were also detected by molecular biology in vectors (i.e., tabanid flies) in Russia [149] and Poland [147]. Studies concerning the characterization of Megatrypanum trypanosomes from European Cervidae using isoenzyme analysis and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis suggested that there should be at least two Megatrypanum species infecting European deer, one in roe deer, and one in fallow and red deer, and differing from T. theileri affecting cattle [127]. More recent studies on phylogenetic analysis of Megatrypanum trypanosome from cattle, water buffalo, deer, and antelopes revealed the presence of several host-specific genotypes [167]. Unfortunately, the assessment of pathogenic effects and clinical course of Trypanosoma spp. infections in the wild fauna is generally challenging and the diagnosis rely mostly on post-mortem examination, which only in few cases has allowed to detect poor general conditions and small size in infected animals [148,168].

The presence of trypanosomes in roe deer was also reported in Poland by Kingston et al. [122] during one of the few epidemiological studies focused on such parasites in wild fauna in Europe. Blood from hunted roe deer killed between August 1984 and July 1988 revealed a prevalence of 66.6%. The Trypanosoma found differed from any others isolated from wild ruminants in central Europe and North America, and a consistent percentage of protozoa lacked a free flagellum, assumed by the authors to be the vector-infective form. Therefore, a new species in the subgenus Megatrypanum was described on the basis of morphological traits, namely, Trypanosoma stefanskii. No sequence was deposited in GenBank and, to our knowledge, no other reports of this species occur.

On a diagnostic perspective, T. theileri and other Megatrypanum trypanosomes of ruminants often represent an occasional finding occurring in other investigations [128,149]. For example, Galuppi et al., during cattle blood culture trials for the cultivation of piroplasms [169], observed the presence of Trypanosoma sp. (R.G., personal communication). As it emerges, reports of these trypanosomes are often occasional and the actual prevalence in domestic and wild fauna is not known.

3.2. Trypanosoma melophagium

Amongst Megatrypanum trypanosomes, T. melophagium is species-specific for domestic sheep and is transmitted by the sheep ked Melophagus ovinus. Ked become infected through the blood of parasitized animals and, after multiplication in the digestive system of the fly, the metacyclic form develops in the hindgut. Sheep acquire the infection by eating infected ked [2,163]. The first report of T. melophagium was from Germany, where in 1905 Pfeiffer observed the presence of “trypanosome-like flagellates” in sheep ked [98]. At first, studies failed in proving the presence of the protozoan in sheep blood and T. melophagium was classified as a parasite of the ked gut and named Crithidia melophagia [170,171]. Few years later Woodcock succeeded in observing trypanosomes in fresh sheep’s blood and identified them as developmental stages of the flagellates described in sheep ked [103]. Interestingly, his work was hardly criticized, and only after almost 10 years of controversy, Nöller [172] and Kleine [173], in separate studies proved not only that T. melophagium and C. melophagia were actually the same species but also that ked became infected only after feeding on infected sheep. This was finally confirmed by Hoare [104] who, in the same years, found T. melophagium in the 80% of the sheep examined in England. Gibson and colleagues observed close genetic similarity between T. melophagium and T. theileri, suggesting that T. melophagium represents a lineage of T. theileri that adapted to be transmitted by sheep ked [107]. In more recent years, this protozoan has been eradicated in the United Kingdom as a consequence of the widespread use of pesticides effective against ked [105], with persistency in the Outer Hebrides off the northwest coast of Scotland [106]. Infection with T. melophagium is not associated with clinical manifestations, the parasitemia is transitory (3 months), and there is no lasting immunity, and thus sheep can be readily re-infected after several months [104]. Due to the lack of clinical manifestation associated with the infection in sheep, scattered and sporadic reports occurred in Europe, particularly from Germany [100], southeastern Russia [102], former Yugoslavia (currently Croatia and Kosovo) [108], and Turkey [174]. Such sporadic reports could be related to difficulties in the detection of T. melophagium in sheep blood samples, possibly due to the low and transitory parasitemia. In fact, a more recent study conducted in Croatia observed a re-emergence of sheep ked in organic farms—the ked were heavily infected by T. melophagium (86% of samples), however, none of the 134 sheep from which they had been collected resulted positive at blood smear examination [97].

3.3. Trypanosoma lewisi

T. lewisi is a cosmopolitan Herpetosoma species, also widely distributed in Europe, responsible for infections in rodents, more specifically in rats. T. lewisi is perhaps the best studied non-pathogenic trypanosome amongst the ones here presented, probably for its presence in rats used as laboratory animals [2]. Its first observation dates back to 1850 in France, by Chaussat, who referred its finding as nematode larvae in blood [175]; only almost 30 years later was the parasite recognized as a trypanosome species [176]. Dynamics of infection have been largely studied by Minchin and Thompson, who in 1915 published an extremely detailed work on the development of T. lewisi in its vector, the rat flea Ceratophyllus fasciatus [177].

In rats, the infection occurs without clinical manifestations, and is primarily characterized by the presence of epimastigote forms in peripheral blood. Rat fleas, while feeding upon the rodent’s blood, eliminate feces containing final metacyclic stages, the metatrypanosomes. Through injured skin or mucosae, parasites gain entrance to the host blood stream and multiply as epimastigotes. Several days are needed to detect the parasites in blood and the prepatent period varies according to the parasite load [66]. Recent in vitro studies have also demonstrated the presence of further stages of development and multiplication, such as the “rosette” stage (multiple divisions forms) and the trypomastigote [178].

Although T. lewisi is considered cosmopolitan, only few findings have been reported in European wild/synantropic murine population. For instance, it was described in 1970 in Southern Finland, mostly in Helsinki, wherein 36.2% of rats tested positive [94]. Moreover, it was reported in Norway in voles (Clethrionomys glareolus, Microtus agrestis, and Apodemus sylvaticus) [95] and again more recently in voles in Poland [96], but with no prevalence data due to the different aim of the studies (morphological characterization). Rodríguez et al. [41] reported T. lewisi in 13% of the rat population examined in the Canary Islands (Spain).

T. lewisi can be transmitted to humans, but only few cases have been described, mostly in children from in Asia and Africa, showing a fatal course if untreated [70,71,179]. Recent studies have demonstrated that T. lewisi is resistant to trypanolysis operated by human serum, exhibiting characteristics similar to human pathogenic trypanosomes; therefore, its role as human pathogen might be underestimated [180]. In Europe, no human cases due of T. lewisi infection have been described thus far.

3.4. Trypanosoma nabiasi

T. nabiasi was firstly observed in France, where it was reported as an unidentified trypanosome in the blood of wild and domestic rabbits by Jolyet and Nabias [109]. It was lately named as T. nabiasi by Raillet in 1895 and considered as a T. lewisi-like form in the subgenus Herpetosoma [2]. It is now phylogenetically included in the “trypanosomes with unspecified subgenus” clade [72]. The life cycle of T. nabiasi comprises the flea Spilopsyllus cuniculi as a vector [181]. Rabbits become infected after ingestion of the flea or by contamination of injured skin or mucosae with flea feces. Prepatence may vary from 5 to 12 days, while infection lasts from 4 up to 8 months, during which the parasite can be found in the rabbit blood and is infective for fleas; immunity prevents from reinfection [112,182]. T. nabiasi was described in wild rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in Great Britain [112] and in Cottontail rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.) in North America [183]. More recently, T. nabiasi has been reported from rabbits in Spain in coinfection with Leishmania infantum, highlighting possible problems occurring in the diagnosis of leishmaniasis in case of co-presence of these flagellates [110,111].

3.5. Trypanosomes of Small Rodents

Another T. lewisi-like protozoan is T. evotomys, a parasite of Arvicolinae rodents, referred to the subgenus Herpetosoma [2] and now phylogenetically included in the “trypanosomes with unspecified subgenus” clade [72]. Described for the first time by Watson and Hadwen in 1912 in the Canadian vole (Evotomys saturates, now Clethrionomys glareolus) [183], it was subsequently found in the United Kingdom [69,80,81,82,83], Germany [78,79], Poland [84,85], and Bulgaria [77]. The vector is yet to be identified, although fleas are possibly involved. In experimental infection via inoculation, prepatence lasts from 5 to 6 days, during which parasites invade and multiply in lymph nodes and spleen. Patent infection typically lasts 1 month or more in splenectomized hosts [77].

Trypanosoma. grosi is included within the T. lewisi-like group. It was firstly described as “very motile vermicules” by Gros [91] in Russian wood mouse (A. sylvaticus) and its recognition as Trypanosoma sp. occurred several years later in France by Laveran and Pettit [87]. In Russia, it was at first misidentified (Trypanosoma apodemi and Trypanosoma korssaki) when found in different vole species [84], and then more recently recognized as synonyms of T grosi [2]. Since then, this species has been reported in the United Kingdom [80,82,90], Ireland [90], Germany [88], Hungary [89], and the Czech Republic [86]. Moreover, T. grosi kosewiense has been described as a new subspecies of T. grosi in Poland from voles (Microtus spp. and Apodemus spp.) and from the yellow-necked mouse (Apodemus flavicollis) [93].

T. musculi is a trypanosome of the house mouse (Mus musculus), which was first observed in mouse blood in Gambia by Dutton and Todd in 1903 and was defined as a new species of the subgenus Herpetosoma by Thiroux in 1905 [184]. It has not been included in any phylogenetic clade yet. Mice acquire the infection from fleas of the genera Ctenophthalmus, Leptopsylla, and Nosopsylla [185]. As happened with T. lewisi, the role of T. musculi as a potential human pathogen has been questioned, mainly due to the biological and morphological characteristics shared between them. T. musculi revealed in vivo and in vitro lower sensitivity to human sera than T. brucei brucei but higher when compared to T. lewisi. Although no case of trypanosomiasis attributed to T. musculi has been reported yet, and infection in healthy humans is considered unlikely, some authors suggest caution, especially in immunocompromised patients [186]. In Europe, the only report available in the literature is from a review on protozoans of British small rodents where T. musculi is cited as a parasite of Mus musculus; no further data are available [82].

Moreover, during a parasitological study conducted on common shrew (Sorex araneus) in Northwest England, 9 out of 76 specimens tested positive for Trypanosoma spp. It is not possible to identify parasites at the species level on the basis of molecular data available in GenBank. The strain shared great similarity with T. lewisi, but formed an outgroup when clustered with Trypanosoma microti, T. evotomys, T. musculi, T. lewisi, and T. grosi [157].

3.6. Trypanosomes of Bats

Over 30 species of trypanosomes of the Schizotrypanum subgenus have been reported in more than 100 Chiroptera species all over the world, including the well-defined Trypanosoma cruzi, T. vespertilionis, T. rangeli, and the globally distributed T. dionisii [187]. Trypanosomes in bats were first described in Miniopterus schreibersii from Italy in 1899 by Dionisi, who identified it as T. vespertilionis; this species was further reported in Italy [140,141], Ireland [142], France [138], and the United Kingdom [143]. In Portugal, Bettencourt and Franca [74] described the species T. dionisii, which was later considered as a synonym of T. vespertilionis, later reported during specific surveys on trypanosomes in bats in the United Kingdom [144,145]. Only in 1975 did a comparative study based on laboratory culture prove that although these parasites were closely related, they actually differed from a morphological, physiological, and antigenical standpoint [188]. Such species are considered T. cruzi-like due to morphological similarities with T. cruzi [2]. In the United Kingdom, a later survey conducted on British bats reported the presence of both T. dionisii and T. vespertilionis [146]. A subspecies of T. dionisii, T. dionisii breve, was described in France in 1979, and was differentiated on the basis of morphological differences and enzyme electrophoresis [76]; however, to our knowledge, no further reports succeeded.

In bats, trypanosome development follows the T. cruzi pattern—infection of the host occurs through injured skin with epimastigote forms invading bloodstream to reach the target organs, namely, striated muscle, cardiac muscle, and stomach muscle (depending on strains/species involved), where parasites multiply as amastigote forms and may form pseudocysts in which trypanosomes multiply by binary fission as epimastigote; rupture of this pseudocysts allows the trypanosome to invade the bloodstream as trypomastigote forms [2]. Vectors of bat trypanosomes are Cimex spp. and bat flies (Nycterida schmidlii) [75,152]. No report of clinical manifestation has thus far been notified. In a recent study, 381 bat specimens collected in eastern and central Europe between 2015 and 2019 were screened with nested PCR for trypanosomes presence—a part of these tested positive for T. dionisii (32.3% in the Czech Republic, 8.3% in Bulgaria, and 16.2% in Poland), while a smaller fraction tested positive for T. vespertilionis (3.8% in the Czech Republic). Hematological parameters showed no significant differences between infected and non-infected specimens [73]. In the same year, a survey about the presence of Trypanosoma spp. in bats (9 subjects from Hungary, 16 from Italy, and 10 from Spain) and the flies Nycteribia schmidlii scotti (71 subjects) parasitizing them, found that in Hungary the prevalence of infection was 33.3% in bats and 35.3% in bat flies, while in Italy it was 43.8% and 11.6%, and in Spain it was 30% and 81.8%, respectively; no species identification was performed [152].

3.7. Trypanosoma pestenai

Amongst the trypanosomes naturally infecting wild carnivores, T. pestanai is the only one described in the European territory. T. pestanai recognizes the badger (Meles meles) as preferential host and was first reported in Portugal in 1905 [189]. It was then described in France [113], the United Kingdom [117,118,120,121], and Ireland [116]. In particular, in the United Kingdom, the role of the badger flea (Paraceras melis) in the transmission of T. pestanai has been recognized [119]. As observed for most of non-pathogenic trypanosomes, the infection in badgers seems to be silent, and not associated with alterations of complete blood count [116]. This parasite has been recently reported in Germany in a 12-year-old beagle with a history of occasional travels to Switzerland, and parasitological investigations based on PCR and blood cell cultivation revealed the concurrent presence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum [115].

3.8. Trypanosoma spp.

Besides reports concerning the aforementioned Trypanosoma species, in some cases identification has been carried out only at the genus level [151,155,156]. For example, Olmeda et al. [155] described the presence of protozoans morphologically referable to the Megatrypanum subgenus in blood smear from 17 deer shot in Spain; however, no further data are available. Moreover, in Spain, during a study focused on non-lethal parasites of wild rabbit in a re-stocking program, 125 rabbits of different age classes were examined to test the presence of Trypanosoma spp. in blood smear, finding a prevalence of 9.5% in young, 4.4% in juveniles, and 8.2% in adults; no morphological or molecular identification was performed [156]. Such findings suggest that further studies are necessary to increase the knowledge on the Trypanosoma species circulating in European mammals.

4. Closing Remarks

The genus Trypanosoma includes a wide number of worldwide distributed species that can affect human and animal health. The most important and studied pathogenic species are responsible for African and South American trypanosomiases. As described in this review, the presence of such species in Europe is typically linked to human or animal immigration/travel/introduction from endemic countries. Such reports do not seem to constitute a threat for the European population due to the life cycle and transmission route strictly depending on vectors that are not present in Europe. On the contrary, occasional findings of T. evansi might represent a concern, due to the possible spillover to native hosts, favored by the wide range of vectors involved also in a non-cyclic transmission route.

The presence of autochthonous Trypanosoma species described in this review, all referable to non-pathogenic stercorarian trypanosomes, has been documented in Europe since the XIX century in both domestic and wild animals. Due to their scant pathogenic effects on the host, these species are more frequently reported as occasional findings during parasitological surveys not specifically focused on trypanosomes and/or during the molecular diagnosis of other strictly related pathogens, such as Leishmania spp. [110,111,146].

Although accidental, such findings are far from being trivial, as they provide useful information on the current epidemiological distribution of trypanosomatids in different geographical areas and hosts [148], with relevant implications also for the improvement of diagnostics [110,111]. Studies aimed to improve our knowledge on their epidemiology in Europe should be encouraged, especially considering that environmental changes could increase their spatial distribution.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Perla Tedesco for the English revision.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F.; data curation A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, R.G., M.F.; visualization, R.G.; supervision, M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Votýpka J., d’Avila-Levy C.M., Grellier P., Maslov D., Lukeš J., Yurchenko V. New Approaches to Systematics of Trypanosomatidae: Criteria for Taxonomic (Re)description. Trends Parasitol. 2015;31:460–469. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoare C.A. The Trypanosomes of Mammals. 1st ed. Blackwell Scientific Publications; Oxford, UK: Edinburgh, UK: 1972. pp. 125–140, 214–219, 219–245, 277–282. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radwanska M., Vereecke N., Deleeuw V., Pinto J., Magez S. Salivarian trypanosomosis: A review of parasites involved, their global distribution and their interaction with the innate and adaptive mammalian host immune system. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2253. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linder A.K., Priotto G. The Unknown Risk of Vertical Transmission in Sleeping Sickness—A Literature Review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2010;4:e783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brun R., Blum J., Chappuis F., Burri C. Human African trypanosomiasis. Lancet. 2010;375:148–159. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60829-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blum J.A., Neumayr A.L., Hatz C.F. Human African trypanosomiasis in endemic populations and travelers. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012;31:905–913. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1403-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashcroft M.T. The importance of African wild animals as reservoirs of trypanosomiasis. East Afr. Med. J. 1959;36:289–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Auty H., Anderson N.E., Picozzi K., Lembo T., Mubanga J., Hoare R., Fyumagwa R.D., Mable B., Hamill L., Cleaveland S., et al. Trypanosome Diversity in Wildlife Species from the Serengeti and Luangwa Valley Ecosystems. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012;6:e1828. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Junyent J.M.G., Rozman M., Corachan M., Estruch R., Urbano-Marquez A. An unusual course of west African trypanosomiasis in a Caucasian man. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1987;81:931–932. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(87)90356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braendli B., Dankwa E., Junghanss T. East African sleeping sickness (Trypanosoma rhodesiense infection) in 2 Swiss travelers to the tropics. Swiss Med. Wkly. 1990;120:1348–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iborra C., Danis M., Bricaire F., Caumes E.A. Traveler Returning from Central Africa with Fever and a Skin Lesion. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1999;28:679–680. doi: 10.1086/517213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jamonneau V., Garcia A., Ravel S., Cuny G., Oury B., Solano P., N’Guessan P., N’Dri L., Sanon R., Frézil J.L., et al. Genetic characterization of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and clinical evolution of human African trypanosomiasis in Côte d’Ivoire. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2002;7:610–621. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ripamonti D., Massari M., Arici C., Gabbi E., Farina C., Brini M., Capatti C., Suter F. African sleeping sickness in tourists returning from Tanzania: The first 2 Italian cases from a small outbreak among European travelers. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002;34:18–22. doi: 10.1086/338157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bisoffi Z., Beltrame A., Monteiro G., Arzese A., Marocco S., Rorato G., Anselmi M., Viale P. African Trypanosomiasis Gambiense, Italy. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005;11:1745–1747. doi: 10.3201/eid1111.050649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gautret P., Clerinx J., Caumes E., Simon F., Jensenius M., Loutan L., Shlagenhauf P., Castelli F., Freedman D., Miller A., et al. Imported human African trypanosomiasis in Europe, 2005–2009. Eurosurveillance. 2010;14:19327. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.36.19327-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gómez-Junyent J., Pinazo M.J., Castro P., Fernández S., Mas J., Chaguaceda C., Pellicé M., Muñoz J. Human African Trypanosomiasis in a Spanish traveler returning from Tanzania. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017;11:e0005324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huits R., De Ganck G., Clerinx J., Büscher P., Bottieau E. A veterinarian with fever, rash and chancre after holidays in Uganda. J. Travel Med. 2018;25:1–2. doi: 10.1093/jtm/tay104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao J.-M., Qian Z.-Y., Hide G., Lai D.-H., Lun Z.-R., Wu Z.-D. Human African trypanosomiasis: The current situation in endemic regions and the risks for nonendemic regions from imported cases. Parasitology. 2020;147:922–931. doi: 10.1017/S0031182020000645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simarro P.P., Franco J.R., Cecchi G., Paone M., Diarra A., Postigo J.A.R., Jannin J.G. Human African Trypanosomiasis in Non-Endemic Countries. J. Travel Med. 2012;19:44–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angheben A. Chagas Disease in the Mediterranean Area. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2017;4:223–234. doi: 10.1007/s40475-017-0123-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coura J.R. The main sceneries of Chagas disease transmission. The vectors, blood and oral transmissions—A comprehensive review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2015;110:277–282. doi: 10.1590/0074-0276140362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jansen A.M., Xavier S.C.C., Roque A.L.R. Trypanosoma cruzi transmission in the wild and its most important reservoir hosts in Brazil. Parasites Vectors. 2018;11:502. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-3067-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jansen A.M., Xavier S.C.C., Roque A.L.R. Landmarks of the Knowledge and Trypanosoma cruzi Biology in the Wild Environment. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020;10:10. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angheben A., Anselmi M., Gobbi F., Marocco S., Monteiro G., Buonfrate D., Tais S., Talamo M., Zavarise G., Strohmeyer M., et al. Chagas disease in Italy: Breaking an epidemiological silence. Eurosurveillance. 2011;16:19969. doi: 10.2807/ese.16.37.19969-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gobbi F., Angheben A., Anselmi M., Postiglione C., Repetto E., Buonfrate D., Marocco S., Tais S., Chiampan A., Mainardi P., et al. Profile of Trypanosoma cruzi Infection in a Tropical Medicine Reference Center, Northern Italy. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014;8:e3361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Repetto E.C., Zachariah R., Kumar A., Angheben A., Gobbi F., Anselmi M., Al Rousan A., Toricco C., Ruiz R., Ledezma G., et al. Neglect of a Neglected Disease in Italy: The Challenge of Access-to-Care for Chagas Disease in Bergamo Area. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015;9:e0004103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antinori S., Galimberti L., Bianco R., Grande R., Galli M., Corbellino M. Chagas disease in Europe: A review for the internist globalized world. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2017;43:6–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basile L., Jansà J.M., Carlier Y., Salamanca D.D., Angheben A., Bartoloni A., Seixas J., Van Gool T., Cañavate C., Flores-Chávez M., et al. Chagas disease in European countries: The challenge of a surveillance system. Eurosurveillance. 2011;16:19968. doi: 10.2807/ese.16.37.19968-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor D.B. Reference Module in Biomedical Science. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2020. Stable Fly (Stomoxys calcitrans) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones T.W., Dávila A.M. Trypanosoma vivax—Out of Africa. Trends Parasitol. 2001;17:99–101. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4922(00)01777-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chamond N., Cosson A., Blom-Potar M.C., Jouvion G., D’Archivio S., Medina M., Droin-Bergère S., Huerre M., Minoprio P. Trypanosoma vivax Infections: Pushing Ahead with Mouse Models for the Study of Nagana. I. Parasitological, Hematological and Pathological Parameters. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2010;4:e792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szöör B., Silvester E., Matthews K.R. A Leap Into the Unknown—Early Events in African Trypanosome Transmission. Trends Parasitol. 2020;36:266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2019.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lun Z.R., Lai D.H., Li F.J., Lukes J., Ayala F.J. Trypanosoma brucei: Two steps to spread out from Africa. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:424–427. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carnes J., Anupama A., Balmer O., Jackson A., Lewis M., Brown R., Cestari I., Desquesnes M., Gendrin C., Hertz-Fowler C., et al. Genome and Phylogenetic Analyses of Trypanosoma evansi Reveal Extensive Similarity to T. brucei and Multiple Independent Origins for Dyskinetoplasty. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015;9:e3404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wen Y.Z., Lun Z.R., Zhu X.Q., Hide G., Lai D.H. Further evidence from SSCP and ITS DNA sequencing support Trypanosoma evansi and Trypanosoma equiperdum as subspecies or even strains of Trypanosoma brucei. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016;41:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Desquesnes M., Holzmuller P., Lai D.H., Dargantes A., Lun Z.R., Jittaplapong S. Trypanosoma evansi and surra: A review and perspectives on origin, history, distribution, taxonomy, morphology, hosts, and pathogenic effects. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013:194176. doi: 10.1155/2013/194176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molina J.M., Ruiz A., Juste M.C., Corbera J.A., Amador R., Gutiérrez C. Seroprevalence of Trypanosoma evansi in dromedaries (Camelus dromedarius) from the Canary Islands (Spain) using an antibody Ab-ELISA. Prev. Vet. Med. 1999;47:53–59. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(00)00157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gutiérrez C., Juste M.C., Corbera J.A., Magnus E., Verloo D., Montoya J.A. Camel trypanosomosis in the Canary Island: Assessment of seroprevalence and infection rates using the card agglutination test (CATT/T. evansi) and parasite detection tests. Vet. Parasitol. 2000;90:155–159. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(00)00225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamarit A., Gutiérrez C., Arroyo R., Jimenes V., Zagalá G., Bosch I., Sirvent J., Alberola J., Alonso I., Caballero C. Trypanosoma evansi infection in mainland Spain. Vet. Parasitol. 2010;167:74–76. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gutiérrez C., Desquesnes M., Touratier L., Büscher P. Trypanosoma evansi: Recent outbreaks in Europe. Vet. Parasitol. 2010;174:26–29. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodríguez N.F., Tejedor-Junco M.T., Hernández-Trujillo Y., González M., Gutiérrez C. The role of wild rodents in the transmission of Trypanosoma evansi infection in an endemic area of the Canary Islands (Spain) Vet. Parasitol. 2010;174:323–327. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Desquesnes M., Bossard G., Patrel D., Herder S., Patout O., Lepetitcolin E., Thevenon S., Berthier D., Pavlovic D., Brugidou R., et al. First outbreak of Trypanosoma evansi in camels in metropolitan France. Vet. Record. 2008;162:750–752. doi: 10.1136/vr.162.23.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Defontis M., Richartz J., Engelmann N., Bauer C., Schwierk V.M., Büscher P., Moritz A. Canine Trypanosoma evansi infection introduced into Germany. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2012;41:369–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-165X.2012.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.EFSA AHAW Panel (EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare) More S., Bøtner A., Butterworth A., Calistri P., Depner K., Edwards S., Garin-Bastuji B., Good M., Gortazar Schmidt C., et al. Scientific Opinion on the assessment of listing and categorization of animal diseases within the framework of the Animal Health Law (Regulation (EU) No 2016/429): Trypanosoma evansi infections (including Surra) EFSA J. 2017;15:4892. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2017.4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scott D.W., Miller W.H. Equine Dermatology. 2nd ed. Saunders, Elsevier Science; St. Louis, MO, USA: 2003. Viral and Protozoal Skin Disease; pp. 376–394. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buffard M., Schneider G. Le trypanosome de la dourine. Arc Parasitol. 1900;3:124–133. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Claes F., Büscher P., Touratier L., Goddeeris B.M. Trypanosoma equiperdum: Master of disguise or historical mistake? Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:316–321. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pascucci I., Di Provvido A., Cammà C., di Francesco G., Calistri P., Tittarelli M., Ferri N., Scacchia M., Caporale V. Diagnosis of dourine in outbreaks in Italy. Vet. Parasitol. 2012;193:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calistri P., Narcisi V., Atzeni M., de Massis F., Tittarelli M., Mercante M.T., Ruggieri E., Scacchia M. Dourine Reemergence in Italy. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2012;33:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2012.05.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahmed Y., Hagos A., Merga B., Van Soom A., Duchateau L., Goddeeris B.M., Govaere J. Trypanosoma equiperdum in the horse—A neglected threat? Vlaams Diergeneeskundig Tijdschrift. 2018;87:66–87. doi: 10.21825/vdt.v87i2.16083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gizaw Y., Megersa M., Fayera T. Dourine: A neglected disease of equids. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2017;49:887–897. doi: 10.1007/s11250-017-1280-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borges A.R., Engstler M., Wolf M. 18S rDNA Sequence-Structure Phylogeny of the Trypanosomatida (Kinetoplastea, Euglenozoa) with Special Reference on Trypanosoma. Res. Sq. 2020;15 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-53561/v1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roberts L., Janovy J., Jr. Foundations of Parasitology. 6th ed. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY, USA: 2000. pp. 55–83. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaufer A., Ellis J., Stark D., Barratt J. The evolution of trypanosomatid taxonomy. Parasites Vectors. 2017;10:287. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2204-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Votýpka J., Suková E., Kraeva N., Ishemgulova A., Duží I., Lukeš J., Yurchenko V. Diversity of Trypanosomatids (Kinetoplastea: Trypanosomatidae) Parasitizing Fleas (Insecta: Siphonaptera) and Description of a New Genus Blechomonas gen.n. Protist. 2013;164:763–781. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deplazes P., Eckert J., Mathis A., von Samson-Himmelstierna G., Zahner H. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine. 1st ed. Wageningen Academic Publishers; Wageningen, The Netherlands: 2016. Phylum Euglenozoa; pp. 59–79. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gibson W. Liaisons dangereuses: Sexual recombination among pathogenic trypanosomes. Res. Microbiol. 2015;166:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marquardt W.C., Demaree R.S., Grieve R.B. Parasitology & Vector Biology. 2nd ed. Harcourt/Academic Press; San Diego, CA, USA: 2000. Trypanosomes and Trypanosomiasis; pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stevens J.R., Noyes H.A., Schofield C.J., Gibson W. The molecular evolution of Trypanosomatidae. Adv. Parasitol. 2001;48:1–56. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(01)48003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gibson W. Species concepts for trypanosomes: From morphological to molecular definitions? Kinetoplast. Biol. Dis. 2003;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-9292-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Osório A.L.A.R., Madruga C.R., Desquesnes M., Soares C.O., Ribeiro L.R.R., Costa S.C.G.D. Trypanosoma (Duttonella) vivax: Its biology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and introduction in the New World—A review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2008;103:1–13. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762008000100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garcia H.A., Rodrigues C.M., Rodrigues A.C., Pereira D.L., Pereira C.L., Camargo E.P., Hamilton P.B., Teixeira M.M. Remarkable richness of trypanosomes in tsetse flies (Glossina morsitans morsitans and Glossina pallidipes) from the Gorongosa National Park and Niassa National Reserve of Mozambique revealed by fluorescent fragment length barcoding (FFLB) Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018;63:370–379. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hutchinson R., Gibson W. Rediscovery of Trypanosoma (Pycnomonas) suis, a tsetse-transmitted trypanosome closely related to T. brucei. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015;36:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Auty H., Torr S.J., Michoel T., Jayaraman S., Morrison L.J. Cattle trypanosomosis: The diversity of trypanosomes and implications for disease epidemiology and control. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2015;34:587–598. doi: 10.20506/rst.34.2.2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Echeverria J.T., Soares R.L., Crepaldi B.A., de Oliveira G.G., da Silva P.M.P., Pupin R.C., Martins T.B., Kellermann Cleveland H.P., Ramos C.A.N., Borges F.A. Clinical and therapeutic aspects of an outbreak of canine trypanosomiasis. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2019;8 doi: 10.1590/s1984-29612019018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mansfield J.M. Nonpathogenic Trypanosomes of mammals. In: Kreier J.P., editor. Parasitic Protozoa, Taxonomy, Kinetoplastids and Flagellates of Fish. Volume 1. Academic Press, Inc.; New York, NY, USA: 1977. pp. 297–327. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sutherland C.S., Yukich J., Goeree R., Tediosi F.A. Literature Review of Economic Evaluations for a Neglected Tropical Disease: Human African Trypanosomiasis (“Sleeping Sickness”) PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015;9:e0003397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Fuentes-Vincente J.A., Gutiérrez-Cabrera A.E., Flores-Villegas A.L., Lowenberger C., Benelli G., Salazar-Schettino P.M., Córdoba-Aguilar A. What makes an effective Chagas disease vector? Factors underlying Trypanosoma cruzi-triatomine interactions. Acta Trop. 2018;183:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Molyneux D.H. The morphology and biology of Trypanosoma (Herpetosoma) evotomys of the bank-vole, Clethrionomys glareolus. Parasitology. 1969;59:843. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000070360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lun Z.R., Reid S.A., Lai D.H., Li F.J. Atypical human trypanosomiasis: A neglected disease or just an unlucky accident? Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:107–108. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Desquesnes M., Yangtara S., Kunphukhieo P., Chalermwong P., Jittapalapong S., Herder S. Zoonotic trypanosomes in South East Asia: Attempts to control Trypanosoma lewisi using veterinary drugs. Exp. Parasitol. 2016;165:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schoch C.L., Ciufo S., Domrachev M., Hotton C.L., Kannan S., Khovanskaya R., Leipe D., Mcveigh R., O’Neill K., Robbertse B., et al. NCBI Taxonomy: A comprehensive update on curation, resources and tools. Database. 2020:baaa062. doi: 10.1093/database/baaa062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Linhart P., Banďouchová H., Zukal J., Votypka J., Kokurewicz T., Dundarova H., Apoznanski G., Heger T., Kubickova A., Nemcova M., et al. Trypanosomes in eastern and central European bats. Acta Vet. Brno. 2020;89:69–78. doi: 10.2754/avb202089010069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bettencourt A., França C. Sur un trypanosome de la chauve-souris. CR Soc. Biol. 1905;57:306. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gardner R.A., Molyneux D.H. Schizotrypanum in British bats. Parasitology. 1988;97:43–50. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000066725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baker J.R., Miles M.A. Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) dionisii breve n. subsp. from Chiroptera. Syst. Parasitol. 1979;1:61–65. doi: 10.1007/BF00009774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mitkovska V., Chassovnikarova T., Dimitrov H. First record of Trypanosoma infection in Mediterranean mouse (Mus macedonicus, Petrov & Ružić, 1983) in Bulgaria. ZooNotes. 2014;64:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Krampitz H.E. Kritisches zur Taxonomie und Systematik parasitischer Säugetier-Trypanosomen mit besonderer Beachtung einiger der in Wülmäusen verbreiteten spezifischen Formen. Zschr. Tropenmed. 1961;12:117. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Walter G., Liebisch A. Studies of the ecology of some blood protozoa of wild small mammals in North Germany. Acta Trop. 1980;37:31–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Elton C. The health and parasites of a wild mouse population. Proc. Zool. Lond. 1931;101:657–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1931.tb01037.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Turner C.M.R., Cox F.E.G. Interspecific interactions between blood parasites in a wild rodent community. Ann. Trop. Med. PH. 1985;79:463–465. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1985.11811946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cox F.E.G. Protozoan parasites of British small rodents. Mammal. Rev. 1987;17:59–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2907.1987.tb00048.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Noyes H.A., Ambrose P., Barker F., Begon M., Bennet M., Bown K.J., Kemp S.J. Host specificity of Trypanosoma (Herpetosoma) species: Evidence that bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus) carry only one T.(H.) evotomys 18S rRNA genotype but wood mice (Apodemus sylvaticus) carry at least two polyphyletic parasites. Parasitology. 2002;124:185–190. doi: 10.1017/S0031182001001019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Karbowiak G., Sinski E. The occurrence and morphological characteristics of a Trypanosma evotomys strain from North Poland. Acta Parasitol. 1996;41:105–107. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bajer A., Welc-Falęciakc R., Bednarska M., Alsarraf M., Behnke-Borowczyk J., Siński E., Behnke J.M. Long-Term Spatiotemporal Stability and Dynamic Changes in the Haemoparasite Community of Bank Voles (Myodes glareolus) in NE Poland. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;68:196–211. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0390-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Karbowiak G., Stanko M., Fričová J., Wita I., Hapunik J., Peťko B. Blood parasites of the striped field mouse Apodemus agrarius and their morphological characteristics. Biologia. 2009;64:1219. doi: 10.2478/s11756-009-0195-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Laveran A., Pettit A. Sur le trypanosome du mulot, Mus sylvaticus. CR Soc. Biol. 1909;67:564. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Krampitz H.E. Ueber das Europäische Waldmaustrypanosom, Trypanosoma grosi Laveran et Pettit 1909 (Promonadina, Trypanosomidae) Zschr. Parasitenk. 1959;19:232. doi: 10.1007/BF00260161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Šebek Z. Blood Parasites of Small Mammals in Western Hungary. Parasitol. Hung. 1978;11:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Alharbi B. Ph.D. Thesis. University of Salford; Salford, UK: 2018. Arthropod-Borne Infections in the United Kingdom and Saudi Arabia. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gros G. Observations et inductions microscopiques sur quelques parasites. Bull. Soc. Imp. Nat. Mosc. 1845;18:380. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yakimoff W.L., Korssak D.W. Hämatoparasitologische Notizen. II. Ein Trypanosoma der Feldmaus im ostasiatischen Ufergebiete. Cbl. Bakt. 1910;55:370. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Karbowiak G., Wita I. Trypanosoma (Herpetosoma) grosi kosewiense subsp.n., the Parasite of the Yellow-Necked Mouse Apodemus flavicollis (Melchior, 1834) Acta Protozool. 2004;43:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2010.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rislakki V. Studies on the Prevalence and Effect of Trypasnosoma lewisi Infection in Finnish Rats. Acta Vet. Scand. 1971;12:448–450. doi: 10.1186/BF03547744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wiger R. Seasonal and annual variations in the prevalence of blood parasites in cyclic species of small rodents in Norway with special reference to Clethrionomys glareolus. Ecography. 1979;2 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0587.1979.tb00697.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Karbowiak G., Wita I., Czaplińska U. The occurrence and ultrastructure of Trypanosoma (Herpetosoma) lewisi (Kent, 1880) Laveran and Mesnil, 1901, the parasite of rats (Rattus norvegicus) in Poland. Wiad. Parazytol. 2009;55:249–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Martincović F., Matanović K., Rodrigues A.C., Garcia H.A., Teixeira M.M.G. Trypanosoma (Megatrypanum) melophagium in the sheep ked Melophagus ovinus from organic farms in Croatia: Phylogenetic interferences support restriction to sheep and sheep keds and close relationship with trypanosomes from other ruminant species. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2012;59:134–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2011.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pfeiffer E. Ueber trypanosomenahnliche Plagellaten im Darm von Melophagus ovinus. Zschr. Hyg. Infektkr. 1905;30:324–330. doi: 10.1007/BF02199380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Behn P. Weitere Trypasomenbefunde beim Schafe. Berl. Tierärztl. Wschr. 1912;50:934. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Büscher G., Friedhoff K.T. The Morphology of Ovine Trypanosoma melophagium (Zoomastigophorea: Kinetoplastida) 1. J. Protozool. 1984;31:98–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1984.tb04297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Douwes J.A. Trypanosomen bij het Schaap (Trypanosoma Melophagium, Flu) Tijdschr. Diegeneesk. 1920;47:408. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bozhenko V.P., Zeiss A.L. Trypanosomiasis of sheep. Rev. Microbiol. 1928;7:417–420. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Woodcock H.M. A reply to Miss Porter’s note entitled “Some remarks on the genera Crithidia, Herpetomonas and Trypanosoma”. Parasitology. 1911;4:150. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000002596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hoare C.A. An experimental study of the sheep-trypanosome (T. melophagium Flu, 1908) and its transmission by the sheep-ked (Melophagus ovinus L.) Parasitology. 1923;15:365. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000014888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Small R.W. A review of Melophagus ovinus (L.), the sheep ked. Vet. Parasitol. 2005;130:141–155. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Craig B.H., Tempest L.J., Pilkington J.G., Pemberton J.M. Metazoan-protozoan parasite co-infections and host body weight in St Kilda Soay sheep. Parasitology. 2008;135:433–441. doi: 10.1017/S0031182008004137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gibson W., Pilkington J.G., Pemberton J.M. Trypanosoma melophagium from the sheep ked Melophagus ovinus on the island of St. Kilda. Parasitology. 2010;137:1799–1804. doi: 10.1017/S0031182010000752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Katic R.V. Researches on Trypanosoma melophagium and its Incidence in Yugoslavia. Jug. Vet. Glasnik. 1940;20:373–384. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jolyet F., Nabias B. Sur un hématozoarie du lapin domestique. J. Méd. Bordx. 1891;20:325. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Díaz-Sáez V., Merino-Espinosa G., Morales-Yuste M., Corpas-López V., Pratlong F., Morillas-Márquez F., Martín-Sánchez J. High rates of Leishmania infantum and Trypanosoma nabiasi infection in wild rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in sympatric and syntrophic conditions in an endemic canine leishmaniasis area: Epidemiological consequences. Vet. Parasitol. 2014;202:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Merino-Espinosa G., Corpas-López V., Morillas-Márquez F., Díaz-Sáez V., Martín-Sánchez J. Genetic variability and infective ability of the rabbit trypanosome, Trypanosoma nabiasi Railliet 1895, in southern Spain. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016;45:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Grewal M.S. The life-cycle of the British rabbit trypanosome, Trypanosoma nabiasi Railliet, 1985. Parasitology. 1957;47:100. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000021806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rioux J.-A., Albaret J.-L., Bres A., Dumas A. Présence de Trypanosoma pestanai Bettencourt et França, 1905, chez les Blaireaux du sud de la France. Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comp. 1966;41:281–288. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1966414281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dirie M.F., Bornstein S., Wallbanks K.R., Stiles J.K., Molyneux D.H. Zymogram and life-history studies on trypanosomes of the subgenus Megatrypanum. Parasitol. Res. 1990;76:669–674. doi: 10.1007/BF00931085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dyachenko V., Steinmann M., Bangoura B., Selzer M., Munderloh U., Daugschies A. Co-infection of Trypanosoma pestanai and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in a dog from Germany. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. 2017;9:110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.McCarthy G., Shiel R., O’Rourke L., Murphy D., Corner L., Costello E., Gormley E. Bronchoalveolar lavage cytology from captive badgers. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2009;38:381–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-165X.2009.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Peirce M.A., Neal C. Trypanosoma (Megatrypanum) pestanai in British badgers (Meles meles) Int. J. Parasitol. 1974;4:439–440. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(74)90055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Macdonald D.W., Anwar M., Newman C., Woodroffe R., Johnson P.J. Inter-annual differences in the age-related prevalences of Babesia and Trypanosoma parasites of European badgers (Meles meles) J. Zool. 1999;247:65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1999.tb00193.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lizundia R., Newman C., Buesching C.D., Ngugi D., Blake D., Wa Sin Y., Macdonald D.W., Wilson A., McKeever D. Evidence for a role of the Host-Specific Flea (Paraceras melis) in the Transmission of Trypanosoma (Megatrypanum) pestanai to the European Badger. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sin Y.W., Annavi G., Dugdale H.L., Newman C., Burke T., Macdonald D.W. Pathogen burden, co-infection and major histocompatibility complex variability in the European badger (Meles meles) Mol. Ecol. 2014;23:5072–5088. doi: 10.1111/mec.12917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ideozu E.J., Whiteoak A.M., Tomlinson A.J., Robertson A., Delahay R.J., Hide G. High prevalence of trypanosomes in European badgers detected using ITS-PCR. Parasites Vectors. 2015;8:480. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1088-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kingston N., Bobek B., Perzanowski K., Wita I., Maki L. Description of Trypanosoma (Megatrypanum) stefanskii sp. n. from Roe Deer (Capreolus capreolus) in Poland. Proc. Helminthol. Soc. Wash. 1992;59:89–95. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Verloo D., Brandt J., Van Meirvenne N., Büscher P. Comparative in vitro isolation of Trypanosoma theileri from cattle in Belgium. Vet. Parasitol. 2000;89:129–132. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(00)00191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Bittner L., Wöckell A., Snedec T., Delling C., Böttcher D., Klose K., Köller G., Starke A. Case report: Trace Mineral Deficiency with concurrent Detection of Trypanosoma theileri in a Suckler Cow Herd in Germany. Anim Biol. 2019;21:84. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Frank G. Ueber den Befund von Trypanosomen bei einem in Stein-Wingert (Westerwald, Regierungsbezirk Wiesbaden) verendeten Rinde. Zschr. Infektionskrankh Haustiere. 1909;5:313. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Böse R., Friedhoff K.T., Olbrich S., Büscher G., Domeyer I. Transmission of Trypanosoma theileri to cattle by Tabanidae. Parasitol. Res. 1987;73:421–424. doi: 10.1007/BF00538199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Böse R., Petersen K., Pospichal H., Buchanan N., Tait A. Characterization of Megatrypanum trypanosomes from European Cervidae. Parasitology. 1993;107:55–61. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000079403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Amato B., Mira F., Lo Presti V.D.M., Guercio A., Russotto L., Gucciardi F., Vitale M., Lena A., Loria G.R., Puleio R., et al. A case of bovine trypanosomiasis caused by Trypanosoma theileri in Sicily, Italy. Parasitol. Res. 2019;118:2723–2727. doi: 10.1007/s00436-019-06390-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Greco A., Loria G.R., Dara S., Luckins T., Sparagano O. First Isolation of Trypanosoma theileri in Sicilian cattle. Vet. Res. Commun. 2000;24:471–475. doi: 10.1023/A:1006403706224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Doherty M.L., Windle H., Vooheis H.P., Larkin H., Casey M., Clery D., Murray M. Clinical disease associated with Trypanosoma theileri infection in a calf in Ireland. Vet. Record. 1993;132:653–656. doi: 10.1136/vr.132.26.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Werszko J., Szewczyk T., Steiner-Bogdaszewska Ż., Wróblewski P., Karbowiak G., Laskowski Z. Molecular detection of Megatrypanum trypanosomes in tabanid flies. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2019:5p. doi: 10.1111/mve.12409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Karbowiak G., Wita I., Czaplińska U. Trypanosoma (Megatrypanum) Wrublewskii, Wladimiroff et Yakimoff 1909, the parasite of European bison (Bison bonasus L); Proceedings of the Trudy 5 Respublikanskoj Nauchno-Prakticheskoj Konferentsii; Vitebsk, Belarus. 21–22 September 2006; pp. 268–270. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- 133.Karbowiak G., Wita I., Czaplińska U. Pleomorfizm of trypanosomes occurring in Bison bonasus L. Wiad Parazytol. 2007;53:54. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Karbowiak G., Demiaszkiewicz A.W., Pyziel A.M., Wita I., Moskowa B., Werszko J., Bień J., Goździk K., Lachowicz J., Cabaj W. The parasitic fauna of the European bison (Bison bonasus) (Linnaeus, 1758) and their impact on the conservation. Part 1: The summarising list of parasites noted. Acta Parasitol. 2014;53:363–371. doi: 10.2478/s11686-014-0252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wladimiroff A., Yakimoff W. Bemerkung zur vorstehenden Mitteilung Wrublewskis. Zentralbl Bakteriol. Orig A. 1909;48:164. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Espinosa A.V., Gutiérrez C., Gracia E., Moreno B., Chacón G., Sanz P.V., Büscher P., Touratier L. Presencia de Trypanosoma theileri en bovinos en España. Albéitar Publ. Vet. Indep. 2006;93:36–37. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Villa A., Gutierrez C., Garcia E., Moreno B., Chaćon G., Sanz P.V., Büscher P., Touratier L. Presence of Trypanosoma theileri in Spanish Cattle. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1149:352–354. doi: 10.1196/annals.1428.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Chatton E., Courrier R. Un Schizotrypanum chez les chauve-souris (Vesperugo pipistrellus) en Basse-Alsace. Schizotrypanose et goître endémique. CR Soc. Biol. 1921;84:943. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Dionisi A. La malaria in alcune specie di pipistrelli. Atti Soc. Studi Malaria. 1899;1:133. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Battaglia M. Alcune ricerche su due tripanosomi (Trypanosoma vespertilionis-Trypanosoma lewisi) Ann. Med. Navale. 1904;10:517. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Gonder R. Trypanosoma vespertilionis (Battaglia) Centralbl. f Bakteriol. 1910;53:293–302. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Mettam A.E. On the presence of a trypanosome in an Irish bat. Dublin J. Med. Sci. 1907;124:417–419. doi: 10.1007/BF02974334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Petrie G.F. Observations relating to the structure and geographical distribution of certain trypanosomes. J. Hyg. 1905;5:191–200. doi: 10.1017/S002217240000245X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Coles A.C. Blood parasites found in mammals, birds and fishes in England. Parasitology. 1914;7:17–61. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000006284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]