Abstract

COVID-19, as the cause of a global pandemic, has resulted in lockdowns all over the world since early 2020. Both theoretical and experimental efforts are being made to find an effective treatment to suppress the virus, constituting the forefront of current global safety concerns and a significant burden on global economies. The development of innovative materials able to prevent the transmission, spread, and entry of COVID-19 pathogens into the human body is currently in the spotlight. The synthesis of these materials is, therefore, gaining momentum, as methods providing nontoxic and environmentally friendly procedures are in high demand. Here, a highly virucidal material constructed from SiO2-Ag composite immobilized in a polymeric matrix (ethyl vinyl acetate) is presented. The experimental results indicated that the as-fabricated samples exhibited high antibacterial activity towards Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) as well as towards SARS-CoV-2. Based on the present results and radical scavenger experiments, we propose a possible mechanism to explain the enhancement of the biocidal activity. In the presence of O2 and H2O, the plasmon-assisted surface mechanism is the major reaction channel generating reactive oxygen species (ROS). We believe that the present strategy based on the plasmonic effect would be a significant contribution to the design and preparation of efficient biocidal materials. This fundamental research is a precedent for the design and application of adequate technology to the next-generation of antiviral surfaces to combat SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords: COVID-19, virus elimination, antiviral surfaces, SiO2-Ag composite, ethyl vinyl acetate, surface plasmon resonance effect

1. Introduction

The current worldwide public health and economic crisis resulting from COVID-19 has become a critical problem [1]. At present, there are no vaccines or antiviral drugs available for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19 infections. Currently, many different antiviral agents, including repurposed drugs, are under testing in clinical trials to assess their efficacy, but the quest for an effective treatment against COVID-19 is still ongoing [2,3,4,5]; therefore, it is essential to explore any other effective intervention strategies that may reduce the mortality and morbidity rates of the disease. Some excellent reviews of therapeutics and tools that inactivate SARS-CoV-2 have been published [6,7,8].

SARS-CoV-2 spreads mainly via human fluids, and individuals may acquire the virus after touching different contaminated surfaces [9]. It is known that SARS-CoV-2 remains viable on solids for extended periods (for up to 1 week on hard surfaces such as glass and stainless steel) [10,11]. Consequently, not only is the identification of materials capable of killing viruses by contact and having low cytotoxicity clearly a high priority for all scientists around the world, but the detection of new and effective materials to decontaminate surfaces is also of great concern [12,13,14]. Given the significance of surface and air contamination in the spread of the virus, attention should also be paid to the development of biocidal (virus, bacteria, fungus) materials against the spread of contamination facilitated by frequently touched surfaces, such as protecting hospital environments and the surfaces of biomedical devices, along with decontamination equipment and technologies [6,15,16,17,18].

In this scenario, metals, semiconductors, and inorganic materials are gaining increased attention as broad-spectrum antiviral agents to protect surfaces and packaging, thus preventing new infections in humans [19]. Very recently, Ghaffari et al. [20] discussed efforts to deploy nanotechnology, biomaterials, and stem cells in each step of the fight against SARS-CoV-2, while Basak and Packirisamy [21] have discussed several nanotechnological strategies that can be used as antiviral coatings to inhibit viral transmission by preventing viral entry into host cells. In this context, metal oxide nanoparticles and their composites were established as potent antibacterial agents due to the induced generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the subsequent oxidative stress [22,23]. They can still enter the microorganism’s membranes, reacting with the existing phosphate and sulfate groups, impairing their functioning, and consequently leading to the microorganism’s death [24,25]. ROS can still inhibit the replication activities of DNA/plasmid and some protein enzymes, due to their interaction with phosphate/sulfate groups or even due to genetic changes [25,26]. All of these results, in combination with the permeability of ROS under the cell membrane, can affect the expression of proteins essential for the correct functioning of microorganisms, as well as their replication [24,27,28,29,30,31].

In particular, silver (Ag) is a widely known element for its antimicrobial properties and has been used in colloidal silver compounds or as adsorbed particles in a colloidal carrier [32]. In addition, Ag nanoparticles (Ag NPs) display the antimicrobial properties of bulk Ag, with a significant reduction in the toxic effects observed with Ag cations [33,34,35]. The antimicrobial effects of Ag NPs are accomplished by a unique physiochemical property to generate more efficient contact with microorganisms and enhance interactions with microbial proteins [36]. Ag NPs present excellent activity against many kinds of bacteria [37,38,39,40,41,42] and are capable of disrupting the mitochondrial respiratory chain, leading to the production of ROS [43], and have also demonstrated promising antifungal [44,45] and antiviral capabilities against viruses such as HIV, Tacaribe virus, and several respiratory pathogens, including adenovirus, parainfluenza, and influenza (H3N2) [31,46,47,48,49]. Specifically with regard to antiviral activities, AgNPs are thought to inhibit the entry of the virus into cells due to the binding of envelope proteins, such as glycoprotein gp120, which prevents CD4-dependent virion binding, fusion, and infectivity [31]. In most cases, Ag NPs present the disadvantage of their tendency to agglomerate, leading to a loss of effectiveness. In recent years, the construction of Ag metal/semiconductor composite materials has been identified as a promising strategy for responding to the above problems. Therefore, the strong surface plasmon resonance (SPR) adsorption and high electron trapping ability of Ag NPs are beneficial for promoting the charge transmission bridge [29,50,51,52,53,54,55]. This modification of Ag NPs by light establishes a coulombic restoring force and prompts a charge density, and they are frequently used in plasmonic composites.

Among the large number of metal/semiconductor composites, SiO2-Ag has attracted considerable attention due to its excellent properties, because SiO2 is thermally stable and highly bioactive, and could not only prevent the agglomeration of particles and enhance the surface hydrophilicity but also further improve their stability [56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that mesoporous silica nanoparticle/Ag composite presents great potential as a candidate for the development of products aiming to prevent the spread of drug-resistant pathogens [66,67].

An important feature of such materials is the combination of positive properties of the polymer matrix, such as lightness, flexibility, and ease of production, as well as the ability to modify the properties of the material. However, the Ag NPs hosted in SiO2 have certain drawbacks in relation to their stability. This situation has spurred the study of alternatives allowing viability for technological applications such as their immobilization in a physical support such as a polymer matrix [68,69] and additional reducing agents or capping agents [70]. Polymers displaying antimicrobial properties are the subject of significant attention for their potential technical and medical applications [71,72,73,74]. One of the most promising types of such materials is based on a SiO2-Ag composite immobilized in a polymeric matrix, which has properties that are individually not achievable for each of the components.

Very recently, our research group presented the development and manufacture of materials with anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity, generating potentially safe alternatives for their application, preventing viral proliferation and transmission [27]. Herein, we report the results of our studies on the structure and properties of SiO2-Ag composite immobilized in a polymeric matrix (ethyl vinyl acetate, EVA). Their antibacterial activity towards Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) as well as towards SARS-CoV-2 have been investigated. The synthesized materials were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM), and micro-Raman spectroscopy. Moreover, their optical properties were investigated by using ultraviolet−visible (UV−vis) spectroscopy. In addition, first-principles calculations within the framework of Density functional theory (DFT) were employed to obtain atomic-level information on the geometry and electronic structure, local bonding of the SiO2 model, and their interaction with and . Furthermore, we explored the application of the samples for the photocatalytic activity in the degradation of Rhodamine B (RhB) and trapping experiments were carried out to understand the radical scavenging behavior. The broad spectrum of interesting properties displayed by such materials present opportunities for a multitude of biomedical applications.

2. Materials and Methods

Synthesis Ag NPs: Briefly, silver nitrate (850 mg, AgNO3, Cennabras (Guarulhos, Brazil), 99.8%) was dissolved in 100 mL of deionized water at 90 °C and stirred until complete dissolution. Subsequently, 1.0 mL of sodium citrate (C6H5Na3O7, Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), 98%) diluted in water (1% (wt/wt)) was added and the transparent solution converted to a yellowish-green colloid, which indicated the formation of Ag NPs. After 1 h, the colloidal dispersion was mixed with 11g of amorphous SiO2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and dried at 125 °C in a conventional oven.

Preparation of EVA-SiO2-Ag Composite: EVA 3019, melt index 2.5 g/10 min, was purchased from Braskem (Guarulhos, Brazil). EVA-SiO2-Ag masterbatch was prepared by incorporation in the molten state processing of the SiO2-Ag into the EVA using a co-rotational twin-screw extruder Plastic AX, Brazil. Mineral oil was used as a compatibilizer agent to prevent agglomeration and to provide uniform distribution of the SiO2-Ag into the EVA matrix. Then, 1% in weight of mineral oil (USP Grade, Anastacio Chemistry, São Paulo, Brazil) was firstly dispersed in the polymer by drumming for 20 min at 15 Hz. Subsequently, 10% in weight of SiO2-Ag was added to the mixing drum and the process was maintained for an additional time of 20 min. The processing extrusion temperature was 140 °C. To examine the antimicrobial properties of a typical application product, EVA-SiO2-Ag composite samples were produced using a thermoplastic injection-molding process. Test samples were produced by dry-blending the EVA polymer with the required amount of masterbatch containing the SiO2-Ag additive, which was followed by injection-molding. The samples were 50 by 50 by 1.5 mm and contained the melt-blended EVA composite masterbatch (10% (wt/wt), corresponding to approximately 50 ppm Ag).

Characterizations: The samples were structurally characterized by XRD using a D/Max-2500PC diffractometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) in the 2θ range of 10–50° and a scanning speed of 1° min-1. Furthermore, micro-Raman spectra were recorded using the iHR550 spectrometer (Horiba Jobin-Yvon, Kyoto, Japan) coupled with a Silicon CCD detector and an argon-ion laser (Melles Griot, Rochester, NY USA), which operated at 514.5 nm with a maximum power of 200 mW; moreover, a fiber optic microscope was also employed. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR, Bruker Vector 22 FTIR, Billerica, MA, USA) of the samples was recorded at 400–4000 cm−1. UV–vis diffuse reflectance measurements were obtained using a Varian Cary spectrometer model 5G in diffuse reflectance mode, with a wavelength range of 2000 to 250 nm and a scan speed of 300 nm min−1. An analysis of the thermal stability of samples was conducted on a thermogravimetric (TG/DTA) analyzer (NETZSCH—409 Cell) from 30 to 700 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 and in an oxidizing atmosphere (O2) with 50 mL min−1 flux. The morphologies, textures, and sizes of the samples were observed with a FE-SEM, which operated at 2 kV (Supra 35-VP, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). A Jem-2100 LaB6 (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan) high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HR-TEM) with an accelerating voltage of 200 kV coupled with an INCA Energy TEM 200 (Oxford, Abingdon, UK) was used to obtain larger magnifications and to clearly verify the samples. AFM images were obtained using a Flex-AFM controlled by Easyscan 2 software (Nanosurf, Liestal, Switzerland) in contrast phase mode on an active vibration isolation table (model TS-150, Table Stable LTD®). The cantilever used for image acquisition was the silicon Tap190G (resonant frequency 190 kHz, force constant 48 N/m, Budget Sensors) in setpoint of 50%.

Bactericidal Tests: The bactericidal activity towards E. coli and S. aureus of the pure polymer and the composite with SiO2-Ag was evaluated according to the standard test methodology described in ISO 22196—Measurement of antibacterial activity on plastics and other non-porous surfaces [75], carried out in Nanox’s microbiology laboratory. A 100-μL volume of the bacterial solution (in a concentration of 105 CFU/mL) was inoculated in triplicate over the surface of the samples. The inoculum was then covered with a sterile plastic film which was gently pressed to be distributed throughout the sample area. Samples were incubated in a bacteriological oven at 36 °C for 24 h at 90% humidity. After incubation, the inoculum was recovered with 10 mL of SCDLP broth followed by serial dilution to 10−4 in PBS buffer. One mL of each dilution was plated with Standard Count Agar by Pour Plate. After solidification of the culture medium, the Petri dishes were incubated in the inverted position in a bacteriological oven at 36 °C for 24 h. The logarithmic reduction and percentage reduction by the CFU/mL count were then determined by the following equation:

| (1) |

where R is the antibacterial activity; U0 is the average of the common logarithm of the number of viable bacteria, in cells/cm2, recovered from the untreated test specimens immediately after inoculation; Ut is the average of the common logarithm of the number of viable bacteria, in cells/cm2, recovered from the untreated test specimens after 24 h, and At is the average of the common logarithm of the number of viable bacteria, in cells/cm2, recovered from the treated test specimens after 24 h.

Antiviral Tests: The antiviral activity of the pure polymer and the composite with SiO2-Ag was evaluated by adapting the standard model ISO 21702—Measures of antiviral activity on plastics and other non-porous surfaces [76] and the method used by Tremiliosi et al. [27]. The tests were carried out in a NB3 (biosafety level 3) laboratory at the University of São Paulo, following the recommendations of ANVISA. SARS-CoV-2 was inoculated into liquid media; EVA polymer and the EVA-SiO2-Ag composite samples were incubated for 2 different time intervals (2 and 10 min). Then, they were seeded in Vero CCL-81 cell cultures. After incubation, the viral genetic material was quantified by quantitative PCR in real time and, based on the control, the ability of each sample to inactivate SARS-CoV-2 was determined.

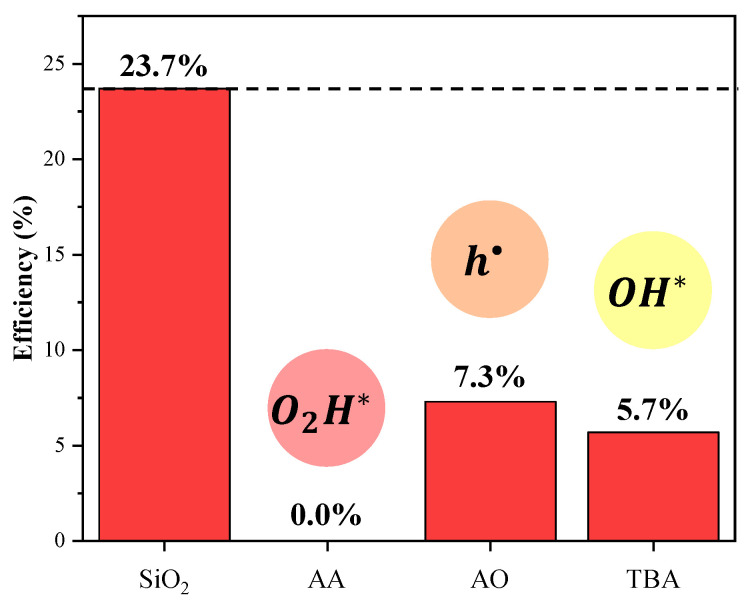

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Identification: To investigate the active species generated in the photocatalytic RhB (Aldrich, 95%) degradation process over SiO2-Ag composite, a trapping experiment was conducted with ascorbic acid (AA), ammonium oxalate (AO), and tert-butyl alcohol (TBA) as the capture agent of hydroxyl radical (), hole , and hydroperoxyl radical (), respectively. The trapping experimental procedure was identical to photocatalytic degradation except that an additional capture agent was added each time. In this way, 50 mg of the sample was dispersed in 50 mL of RhB solution (1 × 10−5 M), and it was kept in the dark for 30 min at 20 °C, and then 6 visible lamps (Philips TL-D, 15W) were switched on. After 60 min, an aliquot was removed and centrifuged to obtain only the liquid phase. The variations in the standard absorption of RhB (554 nm) were discerned through analysis of absorption spectroscopy in the UV–vis region on a V-660 spectrophotometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan).

Computational Method: The calculations were performed with the Gaussian 09 package [77] by using density functional theory (DFT), with the hybrid functional B3LYP and 6-31 ++ G ** basis set. In the Supplementary Materials, the model systems employed in this study are presented. An analysis based on the results of the natural bond orbital (NBO) method (Reed et al.) and the map electrostatic potential (MEP) is employed to investigate the charge transfer process between the SiO2 model and O2 and H2O.

3. Results and Discussion

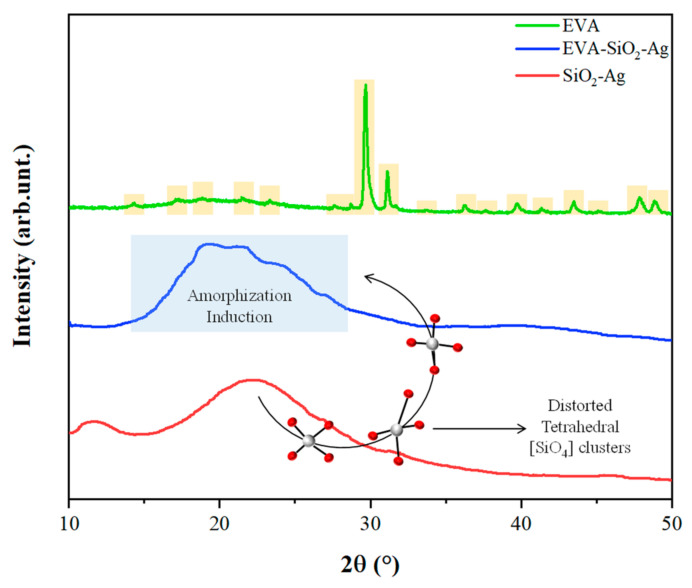

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements are presented in Figure 1. An analysis of the results shows that the sample SiO2-Ag has a characteristic peak of amorphous SiO2 at around 2θ = 22.2° [78,79,80,81]. No additional peak is observed regarding possible Ag phases. For pure EVA, a high crystallinity of the polymer is observed, which is in line with what has been observed in other studies in the literature [82,83]. The SiO2-Ag particles were added in a polymeric matrix, EVA, which has the role of carrier. For the EVA-SiO2-Ag composite, there is an amorphization of the polymeric structure; that is, the symmetry and periodicity break at long-range. This is due to the high degree of disorder of the distorted tetrahedral clusters of [SiO4] present in amorphous SiO2 [84], which cause an induction to amorphization of the polymeric EVA chains. As a result of this union, a broad band located at 2θ = 19.9° is observed.

Figure 1.

X-ray diffractograms of SiO2-Ag, EVA-SiO2-Ag, and EVA samples.

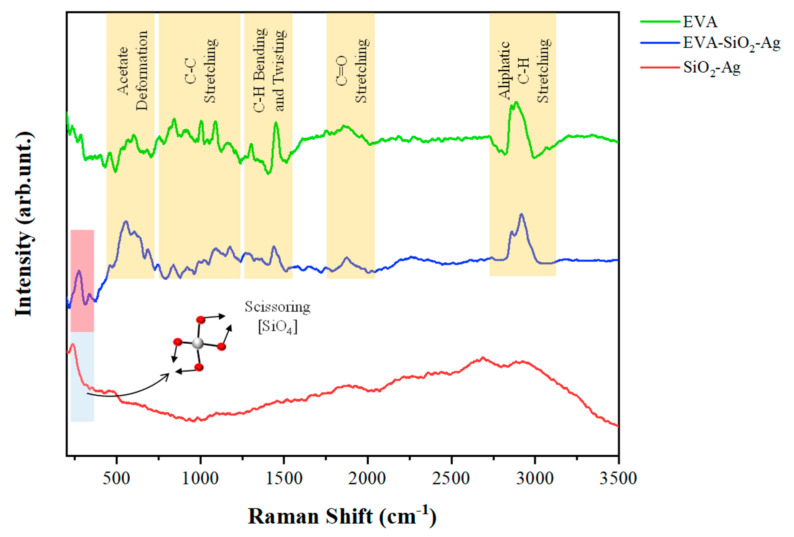

In order to complement the results obtained by XRD, micro-Raman measurements were performed, seeking to analyze the degree of order of the samples at short range (Figure 2). For the SiO2-Ag sample, a peak of approximately ~240 cm−1 is observed, referring to the scissoring of the distorted tetrahedral of the [SiO4] clusters [85]. For pure EVA, there are five distinct groups of vibrations in the micro-Raman spectrum [86]. The vibrations in the range 500–700 cm−1 correspond to the deformation movements of the acetate groups of the EVA monomers [86,87,88]. A set of peaks related to the C-C stretches of the constituent monomers is observed in the range of 750 to 1250 cm−1 [86,89]. The peaks between 1300 and 1500 cm−1 were ascribed to the bending and twisting vibrations of the ethylene groups in the monomers of EVA [86,87]. Between 1700 and 1900 cm−1, stretches related to C=O bonds are observed [86,90]. At the highest wavelengths, located between 2800 and 3050 cm−1, C–H aliphatic stretches of the EVA are observed [87,91]. In contrast to the XRD observations, the composite does not lose its organization at short range; that is, its constituent monomers maintain their degree of structural order. The SiO2-Ag mode in the composite can also be observed, indicating good incorporation in the EVA polymer. According to Shen et al., this mode at ~240 cm−1 may also refer to vibrations of the Ag-O bonds, which can be formed from the interaction of the O atoms of the carbonyl groups of the EVA with the Ag contained in SiO2-Ag [87].

Figure 2.

Micro-Raman spectra of SiO2-Ag, EVA-SiO2-Ag, and EVA samples.

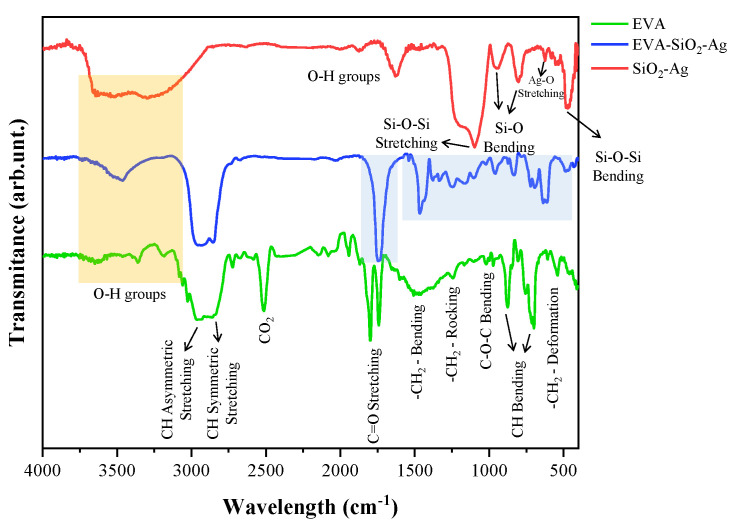

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was performed to analyze changes in the functional groups of the samples and to verify the formation of the composite EVA-SiO2-Ag (Figure 3). For SiO2-Ag, there is a broad band located near 3400 cm−1 and another located at 1627 cm−1, both corresponding to the O–H stretching of water and the formed silanol groups (Si–OH), respectively [92,93]. The bands observed at 1100 and 475 cm−1, on the other hand, are attributed to symmetrical stretching and bending of Si–O–Si bonds, respectively [92,94,95]. The peaks located at 950 and 845 cm−1 indicate the bending of the O–Si–O moiety [80,95]. The low-intensity mode located at 552 cm−1 can be attributed to Ag-O stretching, showing the presence of Ag in SiO2-Ag [96,97]. For EVA, bands referring to the fingerprint of the polymer are observed at 2954, 2850, 1467, 1243, 874, 707, and 546 cm−1, related to the EVA aliphatic groups [98,99,100,101,102]. At 1020 cm−1, the bending of the C–O–C bonds is observed [102], and at 1801 and 1739 cm−1, the C=O bond stretching refers to two different types of carbonyl groups [101,102], as noted by Poljansek et al. [103]. For the EVA-SiO2-Ag composite, changes are observed especially for the stretching of the C=O bonds and throughout the low-wavelength region, where the SiO2 vibrational modes appear. This is because EVA monomers interact through ionic and van der Waals forces with SiO2 and Ag, shown by the overlap of some vibrational modes of the samples and the appearance of new ones. These findings indicate the interactions between the polymer, at short and long range, with the particles of SiO2 and Ag.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of SiO2-Ag, EVA-SiO2-Ag, and EVA samples.

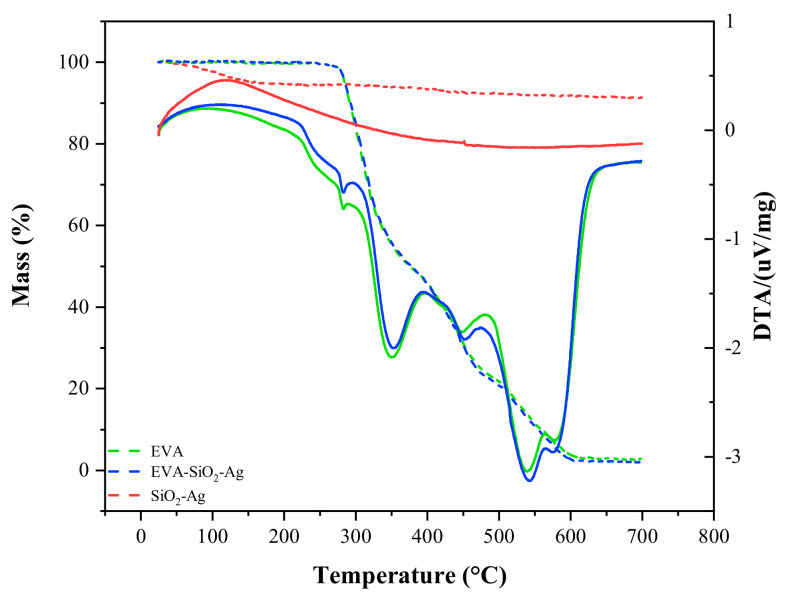

The thermogravimetric (TG) and differential thermal analysis (DTA) curves are shown in Figure 4. In the SiO2-Ag sample, a small loss of mass (9.3%) is observed at 50 °C, due to the loss of water molecules adsorbed onto the material surface, demonstrating its high thermal stability [104,105]. The degradation of the EVA polymer occurs in two main stages: the first is due to the loss of acetate groups (between 300 and 400 °C) and the second is due to the decomposition of the remaining ethylene groups (between 400 and 650 °C) [106,107]. For the composite, there are no significant differences in the TG/DTA profiles compared to the pure polymer, but a slightly smaller loss of mass occurs for this compound (96.8%) than for the EVA (98.2%). This difference is due to the addition of SiO2-Ag in the polymeric structure, which, due to its high thermal stability, does not decompose at higher temperatures.

Figure 4.

TG/DTA curves of SiO2-Ag, EVA-SiO2-Ag, and EVA samples.

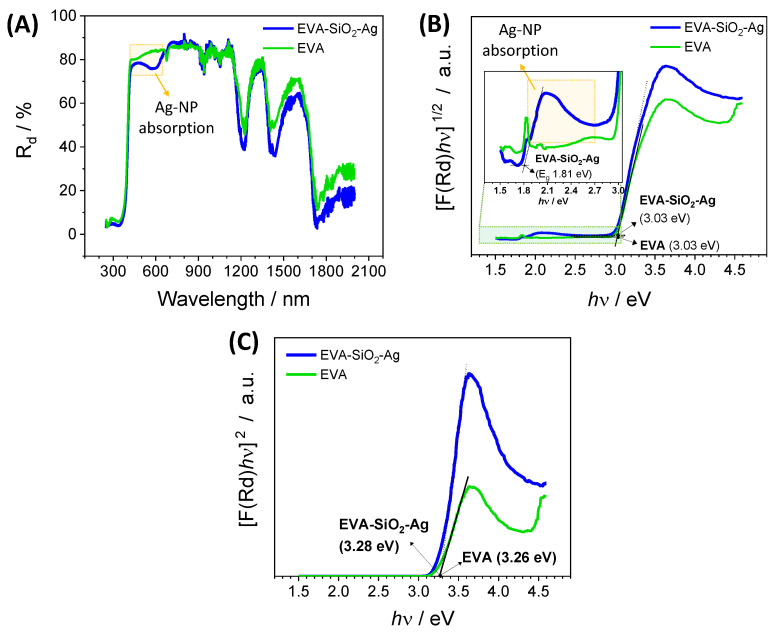

Figure 5A shows the diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) of pure EVA and EVA-SiO2-Ag, in which light absorption is observed in the range of 685 to 480 nm, attributed to the presence of composite SiO2-Ag in the polymer blend. The absorptions on near-infrared wavelengths are ascribed to EVA, where the peaks at 1218, 1440, and 1750 nm are the vibrational modes of the C−H groups in the polymer chain, while the absorption from 1780 to 2000 nm is due to the vinyl acetate group [108,109,110]. The high absorption from 425 nm to ultraviolet wavelengths is attributed to the UV absorber added to the EVA production. The peak at 680 nm is observed for both samples, EVA and EVA-SiO2-Ag. The broad absorption due to the presence of SiO2-Ag is ascribed to the Ag2O nanoparticles in the SiO2, as shown in Figure 5B. The same effect was observed by Paul et al. [111] for Ag2O nanoparticles growth on TiO2 nanorods, in which the composite reduces the bandgap from 2.80 eV (pure TiO2) to 1.68 eV. In another report, Deng and Zhu [112] produced nanocomposite spheres of TiO2/SiO2/Ag/Ag2O with a bandgap in the range of 2.19–3.01 eV. Although the Ag2O bulk material showed a bandgap from 1.2 to 1.43 eV [113], these values depended on the size of the particle, where the smaller the particle, the higher its bandgap. Here, the bandgap of the SiO2-Ag is shown in the inset of Figure 5B, calculated from an indirect interband transition with a value of 1.81 eV. The bandgaps at around 3.03 eV are attributed to the absorption of the UV, which added to EVA production. If a direct electronic transition were considered, only the absorption of the UV absorber would be detected due to the drastic decrease in the diffuse reflectance below 425 nm. The direct transition presents an average energy of approximately 3.26 eV (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

(A) Diffuse reflectance spectra, (B) indirect interband transition and (C) direct interband transition of pure EVA and EVA-SiO2-Ag.

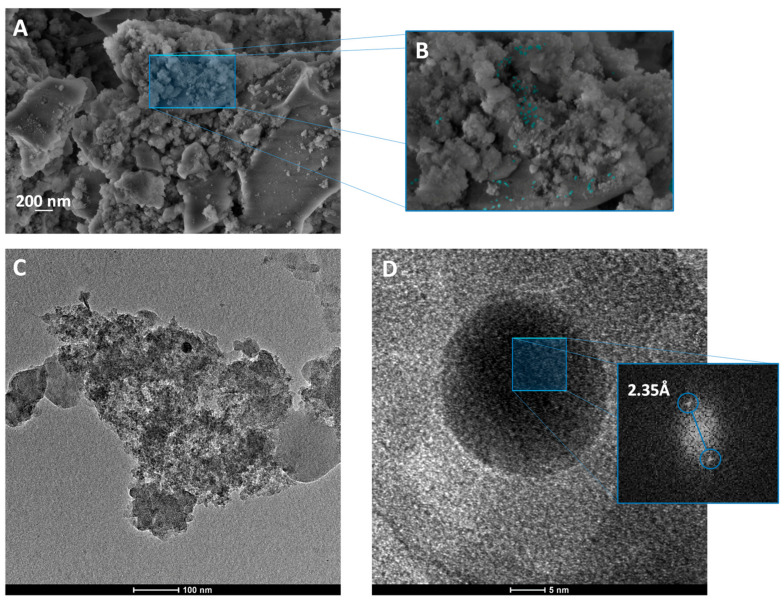

Figure 6 shows the FE-SEM and HR-TEM images for the SiO2-Ag sample. It is observed that SiO2 microparticles have no defined morphology, due to their degree of amorphization. In addition, on the surface of the larger particles, the deposition of some NPs with greater contrast is observed, indicating the deposition of Ag NPs on the surface of SiO2 (Figure 6A,B). To confirm the nature of these deposited NPs, HR-TEM measurements of this sample were performed (Figure 6C,D). As observed in XRD, in the SiO2 microparticles, crystalline planes are not observed, confirming that they are amorphous. In addition, smaller crystalline particles associated with a high-contrast surface are observed, as shown in Figure 6D. Fourier-transform (FT) analysis of the crystalline planes of these particles shows that an interplanar distance of 2.35Å was obtained, which is associated with the metallic Ag plane (111) with a cubic structure, according to the card n°44387 [114] in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), confirming the formation of the SiO2-Ag interface. From the EDX analysis of the sample, a Si/Ag ratio (wt/wt) of 25.84 was obtained ( Figure S1).

Figure 6.

(A,B) FE-SEM images of SiO2-Ag and (C,D) TEM and HR-TEM of SiO2-Ag sample.

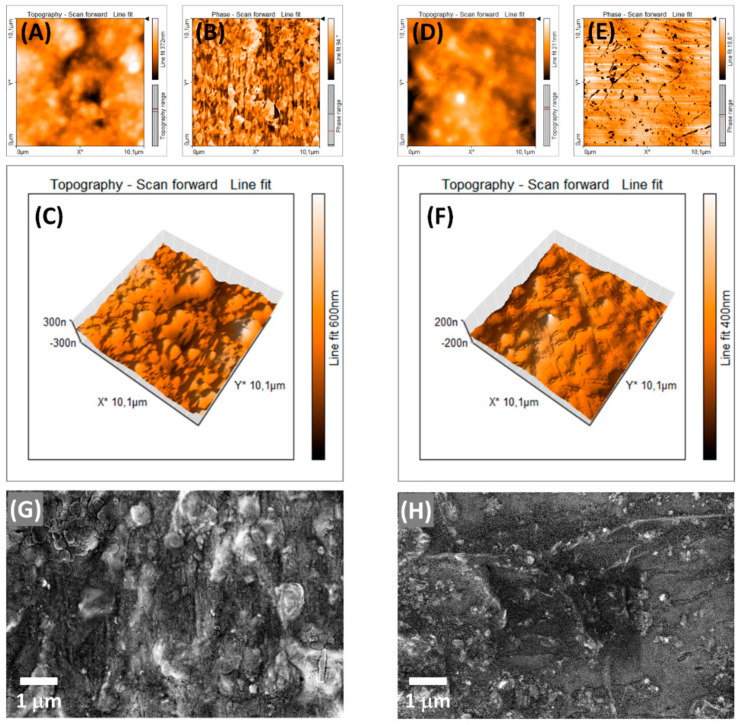

The 2D AFM images shown in Figure 7 present different characteristics after modification of the EVA with the formation of the SiO2-Ag composite. In Figure 7A,B, the height and phase contrast profile for the sample of EVA without the silica-based composite is presented, which provides a surface roughness of 65 nm (root mean square deviation) and a uniform phase contrast with few regions of well-defined contrast. However, the sample EVA-SiO2-Ag shows a small surface roughness, 32 nm, and well-defined regions of contrast phase (Figure 7D,E). The 3D AFM images clearly display the roughness differences between the EVA and EVA-SiO2-Ag samples, as shown in Figure 7C,F, respectively. Moreover, the dark domains in the contrast phase correspond to the SiO2-Ag composite for Figure 7E and present particles of several size scales distributed in the polymeric matrix. Using the image of EVA-SiO2-Ag in contrast phase and assuming that all dark domains are SiO2-Ag composite, it is possible to verify the presence of 599 particles on the surface in a size scale span from 30 to 385,000 nm2. The AFM results are in agreement with the FE-SEM images of the polymer samples. The EVA presents a granular morphology, which is caused by the cure of the polymer blend in its extrusion. After the addition of SiO2-Ag, a distribution of particles is observed on the surface of the polymer composite in a broad size scale span, which is in accordance with the AFM images. The broad size distribution of the particles was observed by Hui et al. [115] in the investigation of the low-density polyethylene/ethylene vinyl acetate modification with SiO2. Furthermore, the decrease in the surface roughness with the addition of Ag in the polymer matrix was noticed by Filip et al. [116] in their study of polyurethane modified with Ag to produce bionanocomposites.

Figure 7.

AFM images of (A–C) EVA and (D–F) EVA-SiO2-Ag samples. SEM images of the (G) EVA and (H) EVA-SiO2-Ag samples.

Once the SiO2-Ag particles were successfully incorporated into the EVA, microbiological tests were carried out against E. coli, S. aureus, and the SARS-CoV-2 virus, due to the high oxidizing power of the Ag NPs combined with the SiO2 capacity to produce ROS, which can cause irreversible damage to these microorganisms. The elimination values against E. coli and S. aureus are shown in Table 1 and the inhibition values against SARS-CoV-2 in Table 2.

Table 1.

Results of the efficacy evaluation of biocides incorporated into specimens against S. aureus (ATCC 6538) and E. coli (ATCC 8739).

| EVA | Eva-SiO2-Ag | Reduction in Relation to Control | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFU*/test piece (recovery) | Log10 of CFU*/test piece (recovery) |

CFU*/test piece (recovery) |

Log10 of CFU*/test piece (recovery) |

Reduction in Log10 | Percentage reduction |

|

| S. aureus | 5.53 × 105 | 5.74 | <1.0 × 10−1 | <1.0 | >4.74 | >99.99% |

| E. coli | 6.40 × 105 | 5.80 | <1.0 × 10−1 | <1.0 | >4.80 | >99.99% |

* CFU–colony forming units.

Table 2.

Copies per mL of SARS-CoV-2 at different times of incubation.

| Sample | Incubation Time | Day 1 | Day 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copies/mL (SARS-CoV-2) |

Viral Inactivation (%) |

Copies/mL (SARS-CoV-2) |

Viral Inactivation (%) |

||

| EVA | 2 min | 7.68 × 109 | − | 3.85 × 108 | − |

| EVA-SiO2-Ag | 2 min | 7.27 × 107 | 99.05 | 2.87 × 106 | 99.26 |

| EVA | 10 min | 2.21 × 109 | − | 5.21 × 108 | − |

| EVA-SiO2-Ag | 10 min | 3.28 × 106 | 99.85 | 1.98 × 106 | 99.62 |

For both bacteria, E. coli and S. aureus, a 99.99% reduction is observed when in contact with the composite after 24 h of incubation. In contrast to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, 99.05% inactivation is observed in 2 min and 99.85% in 10 min for day 1, and 99.26% in 2 min and 99.62% in 10 min for day 2. In both cases, there was no elimination of microorganisms for pure EVA—that is, without the addition of the SiO2-Ag composite. This behavior proves the synergistic effect of SiO2 microparticles and Ag NPs with EVA.

The microbicidal tests were performed for the EVA-SiO2-Ag sample after forced aging by ultraviolet irradiation, following ISO 4892-2: 2013 [117], which aims to reproduce the effects of weathering (temperature, humidity, and/or wetting) that occur when materials are exposed in real-life environments to daylight or daylight filtered through window glass. It was observed that after simulating two years of aging (1200 h of exposure), there is still a 99.950% reduction in the elimination of S. aureus and E. coli. Thus, the durability defined for the EVA-SiO2-Ag was a minimum of two years.

Figure 8 shows the degradation behaviors of the SiO2-Ag composite. An analysis of the results shows that the SiO2-Ag sample has a photocatalytic efficiency of 23.7% in 60 min (see the degradation kinetics in Figure S2), with a reduction of 0.0, 7.3, and 5.7% in the presence of AA, AO, and TBA, respectively. These findings demonstrate that , , and are involved in the photodegradation mechanism. These reactive species appear through the formation of pairs generated in the valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB) [118,119] of the SiO2-Ag composite, with subsequent reaction with and .

Figure 8.

Comparison of photocatalytic degradation of RhB in the presence of different scavengers under visible light irradiation.

SiO2 is an n-type semiconductor with a defined electronic structure, bandgap, and position of both CB and VB. Considering the close relation between the photocatalytic and biocidal properties of semiconductors, their activity can be exerted though similar mechanisms. Activation of water () and molecular oxygen () are the most important chemical processes involved in both photocatalytic and biocide activities, and the ROS are the key signaling molecules in both processes. As demonstrated by the results of the radical scavenger experiments, SiO2 interacts with and to provoke the formation of ROS ( and ) [120,121,122,123] and is effective in inhibiting protein adhesion [124,125].

First-principles calculations were performed to analyze the interaction of and molecules with the SiO2 model. We optimize the SiO2 model and then the map of the molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) is calculated to investigate the charge transfer process between SiO2 and and and these results are presented in the Supplementary Materials (Figures S3–S5 and Table S1). The MEP displays the nucleophilic and electrophilic regions where energetically favorable interactions with and take place, respectively. At the minima of both interactions, there is an electronic charge of 0.04 e− from H2O to SiO2 and 0.10 e− from SiO2 to O2. These events can be considered the early stages of the formation of and .

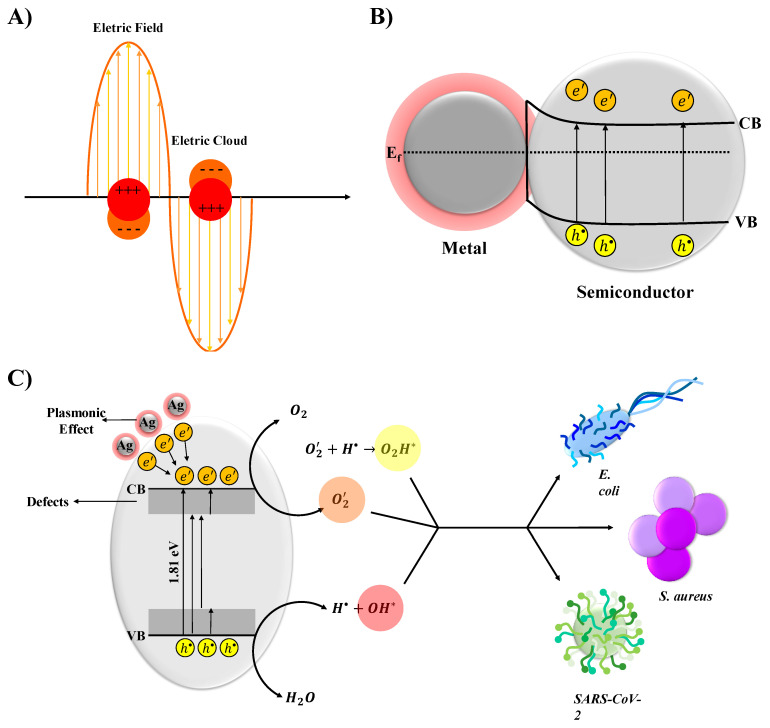

The recognized mechanism corresponding to SPR and associated with photoreactivity has not yet been strictly established. In the present study, the proposed photocatalysis and biocidal mechanism of SiO2-Ag composites is summarized in Figure 9. The Ag NPs and SiO2 particles absorb the incident photons, and the in the VB in SiO2 are excited afterwards. The excited move to the CB; at the same time, the same amount of is generated in the VB. Because of the higher work function of Ag compared with that of SiO2, partially excited would transfer from SiO2 CB to the surface-loaded Ag NPs, since the Fermi energy level of Ag metal is lower than that of SiO2. When the Ag NPs and the SiO2 semiconductor come into contact, free electrons migrate from the Fermi level of metallic Ag to the CB of SiO2 to reach an equilibrium Fermi state. As a consequence, the whole energy band of the SiO2 semiconductor is increased, while that of metallic Ag decreases; this leads to the formation of a depletion layer and an internal electrical field at the interface. The migration of away from the depleted region causes the creation of excess positive and negative charges on the Ag NPs’ surface and in the SiO2 semiconductor, respectively. Thus, the internal electrical field is directed from Ag NP toward the SiO2 semiconductor. Since the SiO2-Ag composite is able to absorb the near-ultraviolet to visible light, this helps to absorb more photons and further excite more within SiO2, resulting in the accumulation of more. The come up against the molecule; meanwhile, is quenched by to complete the cycle. Therefore, the biocidal activity of SiO2 would be greatly improved if the Ag NPs were anchored onto SiO2. To the best of our knowledge, there are still no reports on the utilization of SiO2-Ag composite to target SARS-CoV-2. The SiO2-Ag composite encapsulated EVA with a narrow bandgap not only efficiently increases the flow of the SiO2 but also largely facilitates the charge separation. The subsequent deposition of Ag NPs promotes electron transfer ability, which leads to higher biocidal activity. Moreover, the contact of Ag NPs with the surface of the semiconductor SiO2 can result in an electron-enhanced area in their interface that could effectively facilitate the uptake of electrons and then improve the reduction activity. These reactions can be increased due to the formation of an intense local electric field close to the surface of the Ag NPs (SPR effect) (Figure 9A). At the Ag–semiconductor interface, the number of charge carriers is greater due to the generated electric field, increasing the corresponding separation process (Figure 9B). On the other hand, the interaction with the in a cluster is represented by the transition of from occupied to unoccupied states in the band structure. The occupied states are below the Fermi level, and the unoccupied states are mostly above the Fermi level. In the specific case of bacteria, fungi, and viruses, there is an interaction of the region of lower electronic density of the crystal surface with . In this interaction, loses an , forming a hydroxyl radical () and a proton (). Simultaneously, an is transferred to the molecule, forming the superoxide anion (). This ion, in turn, to maintain the balance of charge and mass, interacts with the forming the hydrogen peroxide radical (). The results summarized above are exemplified in Figure 9C.

Figure 9.

A schematic representation of plasmon-induced hot electrons over SiO2-Ag composite: (A) in Ag NP particles; (B) in metal semiconductor; and (C) proposed mechanism for biocidal activity. (CB and VB represent the conduction band and valence band, respectively.).

4. Conclusions

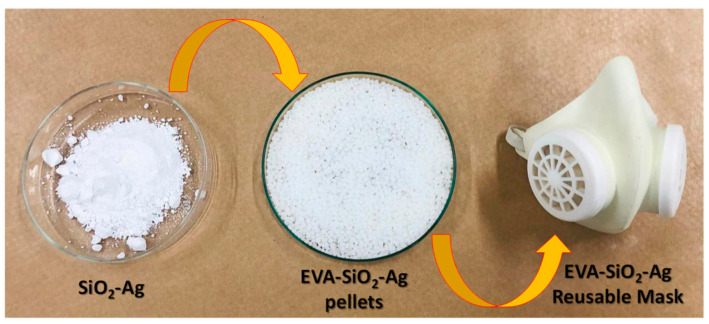

The development of new technologies for constructing highly efficient biocidal materials, particularly coating strategies to prevent SARS-CoV-2, is of great significance. Here, a plasmonic SiO2-Ag composite immobilized in a polymeric matrix (ethyl vinyl acetate) was successfully prepared and the as-fabricated samples exhibited high antibacterial activity towards Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) as well as towards SARS-CoV-2. The enhancement is mainly due to the SPR effect of the Ag NPs anchored onto the SiO2. Considering the close relation between the photocatalytic and biocidal properties of semiconductors, their activity can be exerted though similar mechanisms. The active species trapping experiments suggested that , , and were the main active species for the photocatalytic degradation of RhB and biocidal activity. Given that EVA has high mechanical resistance and stability to water and heat and that the procedure for obtaining the composites is simple and uses low-cost reagents, the SiO2-Ag composite has potential advantages for application as a material biocide, and the elimination of SARS-CoV-2. Finally, we propose emerging technologies that have not yet been used for bactericide/virucide purposes but hold great promise and potential for the future engineering of biocidal surfaces. This is the case for the reusable mask manufactured using the EVA-SiO2-Ag composite presented here, which has high durability, requiring only the replacement of its filters to have a technology applicable to current demands (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Reusable mask manufactured using the EVA-SiO2-Ag composite.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2079-4991/11/3/638/s1, Figure S1 Chemical composition from EDX analysis of the SiO2-Ag; Figure S2 (A) Relative concentration of RhB dye (Cn/C0). (B) Reaction kinetics of the RhB degradation −ln(Cn/C0) versus time (min) for SiO2-Ag composite; Figure S3. Schematic representation of the different rings used for modeling SiO2. Silicon (yellow) and Oxygen (red); Figure S4. The optimized SiO2 model used in the calculations; Table S1 Bond angles and lengths of the structure used; Figure S5. MEP (in eV) of SiO2 model.

Author Contributions

M.A., L.G.P.S., G.C.T., D.C., D.T.M., R.I.S., D.C.B.V., J.R.d.S., L.K.R. and J.A., conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; I.L.V.R., L.H.M., J.A. and E.L., conceptualization, writing—review and editing, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo—FAPESP (FAPESP CEPID—finance code 2013/07296-2, FAPESP/SHELL—finance code 2017/11986-5 and PIPE—finance codes 15/50113-3 and 11/51084-4), FINEP (finance code 03/2013 Ref. 0555/13), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnológico—CNPq (finance code 166281/2017-4), CAPES (finance code 001), Universitat Jaume I (project UJI-B2019-30), and the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (Spain) (project PGC2018094417-B-I00).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author: J.A., upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Infection Prevention and Control during Health Care when Novel Coronavirus (nCoV) Infection is Suspected—Interim Guidance. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li G., De Clercq E. Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020;19:149–150. doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., Yang X., Liu J., Xu M., Shi Z., Hu Z., Zhong W., Xiao G. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colson P., Rolain J.-M., Lagier J.-C., Brouqui P., Raoult D. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as available weapons to fight COVID-19. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;55:105932. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao J., Tian Z., Yang X. Breakthrough: Chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci. Trends. 2020;14:72–73. doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.01047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss C., Carriere M., Fusco L., Capua I., Regla-Nava J.A., Pasquali M., Scott J.A., Vitale F., Unal M.A., Mattevi C., et al. Toward Nanotechnology-Enabled Approaches against the COVID-19 Pandemic. ACS Nano. 2020;14:6383–6406. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c03697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sportelli M.C., Izzi M., Kukushkina E.A., Hossain S.I., Picca R.A., DiTaranto N., Cioffi N. Can Nanotechnology and Materials Science Help the Fight against SARS-CoV-2? Nanomaterials. 2020;10:802. doi: 10.3390/nano10040802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tharayil A., Rajakumari R., Chirayil C.J., Thomas S., Kalarikkal N. A short review on nanotechnology interventions against COVID-19. Emergent Mater. 2021;1:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s42247-021-00163-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo W., Majumder M.S., Liu D., Poirier C., Mandl K.D., Lipsitch M., Santillana M. The role of absolute humidity on transmission rates of the COVID-19 outbreak. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.12.20022467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chin A., Chu J., Perera M., Hui K., Yen H.-L., Chan M., Peiris M., Poon L. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.15.20036673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Lloyd-Smith J.O., De Wit E., Munster V.J., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N., Tamin A., et al. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fathizadeh H., Maroufi P., Momen-Heravi M., Dao S., Köse Ş., Ganbarov K., Pagliano P., Esposito S., Kafil H.S. Protection and disinfection policies against SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Infez. Med. 2020;28:185–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derraik J.G.B., Anderson W.A., Connelly E.A., Anderson Y.C. Rapid Review of SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 Viability, Susceptibility to Treatment, and the Disinfection and Reuse of PPE, Particularly Filtering Facepiece Respirators. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:6117. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Behzadinasab S., Chin A., Hosseini M., Poon L.L.M., Ducker W.A. A Surface Coating that Rapidly Inactivates SARS-CoV-2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12:34723–34727. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c11425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kampf G. Potential role of inanimate surfaces for the spread of coronaviruses and their inactivation with disinfectant agents. Infect. Prev. Pract. 2020;2:100044. doi: 10.1016/j.infpip.2020.100044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kampf G., Todt D., Pfaender S., Steinmann E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020;104:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otter J.A., Donskey C., Yezli S., Douthwaite S., Goldenberg S., Weber D.J. Transmission of SARS and MERS coronaviruses and influenza virus in healthcare settings: The possible role of dry surface contamination. J. Hosp. Infect. 2016;92:235–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Lancet CCOVID-19: Protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;395:922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30644-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imani S.M., Ladouceur L., Marshall T., MacLachlan R., Soleymani L., Didar T.F. Antimicrobial Nanomaterials and Coatings: Current Mechanisms and Future Perspectives to Control the Spread of Viruses Including SARS-CoV-2. ACS Nano. 2020;14:12341–12369. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c05937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghaffari M., Mollazadeh-Bajestani M., Moztarzadeh F., Uludağ H., Hardy J.G., Mozafari M. An overview of the use of biomaterials, nanotechnology, and stem cells for detection and treatment of COVID-19: Towards a framework to address future global pandemics. Emergent Mater. 2021:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s42247-020-00143-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basak S., Packirisamy G. Nano-based antiviral coatings to combat viral infections. Nano-Struct. Nano-Obj. 2020;24:100620. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoso.2020.100620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Podder S., Halder S., Roychowdhury A., Das D., Ghosh C.K. Superb hydroxyl radical-mediated biocidal effect induced antibacterial activity of tuned ZnO/chitosan type II heterostructure under dark. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2016;18:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11051-016-3605-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prasanna V.L., Vijayaraghavan R. Insight into the Mechanism of Antibacterial Activity of ZnO: Surface Defects Mediated Reactive Oxygen Species Even in the Dark. Langmuir. 2015;31:9155–9162. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b02266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alkhouri N., Zein N.N. Protease inhibitors: Silver bullets for chronic hepatitis C infection? Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2012;79:213–222. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.79a.11082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kehrer J.P. The Haber–Weiss reaction and mechanisms of toxicity. Toxicology. 2000;149:43–50. doi: 10.1016/S0300-483X(00)00231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durán N., Marcato P.D., De Conti R., Alves O.L., Costa F.T.M., Brocchi M. Potential use of silver nanoparticles on pathogenic bacteria, their toxicity and possible mechanisms of action. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2010;21:949–959. doi: 10.1590/S0103-50532010000600002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tremiliosi G.C., Simoes L.G.P., Minozzi D.T., Santos R.I., Vilela D.C.B., Durigon E.L., Machado R.R.G., Medina D.S., Ribeiro L.K., Rosa I.L.V., et al. Engineering polycotton fiber surfaces, with antimicrobial activity against S. aureus, E. Coli, C. albicans and SARS-CoV-2. Jpn. J. Med. Sci. 2020;1:47–58. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Assis M., Cordoncillo E., Torres-Mendieta R., Beltrán-Mir H., Minguez-Vega G., Oliveira R., Leite E.R., Foggi C.C., Vergani C.E., Longo E., et al. Towards the scale-up of the formation of nanoparticles on α-Ag2WO4 with bactericidal properties by femtosecond laser irradiation. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19270-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Assis M., Filho F.C.G., Pimentel D.S., Robeldo T., Gouveia A.F., Castro T.F.D., Fukushima H.C.S., De Foggi C.C., Da Costa J.P.C., Borra R.C., et al. Ag Nanoparticles/AgX (X=Cl, Br and I) Composites with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity and Low Toxicological Effects. ChemistrySelect. 2020;5:4655–4673. doi: 10.1002/slct.202000502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akbarzadeh A., Kafshdooz L., Razban Z., Tbrizi A.D., Rasoulpour S., Khalilov R., Kavetskyy T., Saghfi S., Nasibova A.N., Kaamyabi S., et al. An overview application of silver nanoparticles in inhibition of herpes simplex virus. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018;46:263–267. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2017.1307208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lara H.H., Ayala-Nuñez N.V., Ixtepan-Turrent L., Rodriguez-Padilla C. Mode of antiviral action of silver nanoparticles against HIV-1. J. Nanobiotechnology. 2010;8:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silvestry-Rodriguez N., Sicairos-Ruelas E.E., Gerba C.P., Bright K.R. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. Springer New York; New York, NY, USA: 2007. Silver as a Disinfectant; pp. 23–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kędziora A., Speruda M., Krzyżewska E., Rybka J., Łukowiak A., Bugla-Płoskońska G. Similarities and Differences between Silver Ions and Silver in Nanoforms as Antibacterial Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:444. doi: 10.3390/ijms19020444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beer C., Foldbjerg R., Hayashi Y., Sutherland D.S., Autrup H. Toxicity of silver nanoparticles—Nanoparticle or silver ion? Toxicol. Lett. 2012;208:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pauksch L., Hartmann S., Rohnke M., Szalay G., Alt V., Schnettler R., Lips K.S. Biocompatibility of silver nanoparticles and silver ions in primary human mesenchymal stem cells and osteoblasts. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:439–449. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei L., Lu J., Xu H., Patel A., Chen Z.-S., Chen G. Silver nanoparticles: Synthesis, properties, and therapeutic applications. Drug Discov. Today. 2015;20:595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Z., Fang Y., Zhou X., Li Z., Zhu H., Du F., Yuan X., Yao Q., Xie J. Embedding ultrasmall Ag nanoclusters in Luria-Bertani extract via light irradiation for enhanced antibacterial activity. Nano Res. 2020;13:203–208. doi: 10.1007/s12274-019-2598-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monerris M., Broglia M.F., Yslas E.I., Barbero C.A., Rivarola C.R. Highly effective antimicrobial nanocomposites based on hydrogel matrix and silver nanoparticles: Long-lasting bactericidal and bacteriostatic effects. Soft Matter. 2019;15:8059–8066. doi: 10.1039/C9SM01118H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo S., Fan L., Yang K., Zhong Z., Wu X., Ren T. In situ and controllable synthesis of Ag NPs in tannic acid-based hyperbranched waterborne polyurethanes to prepare antibacterial polyurethanes/Ag NPs composites. RSC Adv. 2018;8:36571–36578. doi: 10.1039/C8RA07575A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeremiah S.S., Miyakawa K., Morita T., Yamaoka Y., Ryo A. Potent antiviral effect of silver nanoparticles on SARS-CoV-2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020;533:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burdușel A.-C., Gherasim O., Grumezescu A.M., Mogoantă L., Ficai A., Andronescu E. Biomedical Applications of Silver Nanoparticles: An Up-to-Date Overview. Nanomaterials. 2018;8:681. doi: 10.3390/nano8090681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhakya S., Muthukrishnan S., Sukumaran M., Muthukumar M. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their antioxidant and antibacterial activity. Appl. Nanosci. 2016;6:755–766. doi: 10.1007/s13204-015-0473-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asharani P.V., Mun G.L.K., Hande M.P., Valiyaveettil S. Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity of Silver Nanoparticles in Human Cells. ACS Nano. 2009;3:279–290. doi: 10.1021/nn800596w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lara H.H., Romero-Urbina D.G., Pierce C.G., Lopez-Ribot J.L., Arellano-Jiménez M.J., Jose-Yacaman M. Effect of silver nanoparticles on Candida albicans biofilms: An ultrastructural study. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2015;13:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12951-015-0147-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim K.-J., Sung W.S., Suh B.K., Moon S.-K., Choi J.-S., Kim J.G., Lee D.G. Antifungal activity and mode of action of silver nano-particles on Candida albicans. BioMetals. 2008;22:235–242. doi: 10.1007/s10534-008-9159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen N., Zheng Y., Yin J., Li X., Zheng C. Inhibitory effects of silver nanoparticles against adenovirus type 3 in vitro. J. Virol. Methods. 2013;193:470–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galdiero S., Rai M., Gade A., Falanga A., Incoronato N., Russo L., Galdiero M., Gaikwad S., Ingle A. Antiviral activity of mycosynthesized silver nanoparticles against herpes simplex virus and human parainfluenza virus type 3. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013;8:4303–4314. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S50070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Speshock J.L., Murdock R.C., Braydich-Stolle L.K., Schrand A.M., Hussain S.M. Interaction of silver nanoparticles with Tacaribe virus. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2010;8:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiang D., Zheng Y., Duan W., Li X., Yin J., Shigdar S., O’Connor M.L., Marappan M., Zhao X., Miao Y., et al. Inhibition of A/Human/Hubei/3/2005 (H3N2) influenza virus infection by silver nanoparticles in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013;8:4103–4114. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S53622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huo Y., Wang Z., Zhang J., Liang C., Dai K. Ag SPR-promoted 2D porous g-C3N4/Ag2MoO4 composites for enhanced photocatalytic performance towards methylene blue degradation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018;459:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Z., Wang W., Gao E., Sun S., Zhang L. Photocatalysis Coupled with Thermal Effect Induced by SPR on Ag-Loaded Bi2WO6 with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2012;116:25898–25903. doi: 10.1021/jp309719q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mitsushio M., Miyashita K., Higo M. Sensor properties and surface characterization of the metal-deposited SPR optical fiber sensors with Au, Ag, Cu, and Al. Sensors Actuators A Phys. 2006;125:296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.sna.2005.08.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vasa P., Lienau C. Strong Light–Matter Interaction in Quantum Emitter/Metal Hybrid Nanostructures. ACS Photon. 2018;5:2–23. doi: 10.1021/acsphotonics.7b00650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim S.M., Lee S.W., Moon S.Y., Park J.Y. The effect of hot electrons and surface plasmons on heterogeneous catalysis. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2016;28:254002. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/28/25/254002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Z., Cao D., Wen L., Xu R., Obergfell M., Mi Y., Zhan Z., Nasori N., Demsar J., Lei Y. Manipulation of charge transfer and transport in plasmonic-ferroelectric hybrids for photoelectrochemical applications. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:1–8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jeon H.-J., Yi S.-C., Oh S.-G. Preparation and antibacterial effects of Ag–SiO2 thin films by sol–gel method. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4921–4928. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(03)00415-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Y., Chen J., Tang H., Xiao Y., Qiu S., Li S., Cao S. Hierarchically-structured SiO2-Ag@TiO2 hollow spheres with excellent photocatalytic activity and recyclability. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018;354:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chi Y., Yuan Q., Li Y., Tu J., Zhao L., Li N., Li X. Synthesis of Fe3O4@SiO2–Ag magnetic nanocomposite based on small-sized and highly dispersed silver nanoparticles for catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;383:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.He Y., Zhang L., Teng B., Fan M. New Application of Z-Scheme Ag3PO4/g-C3N4 Composite in Converting CO2 to Fuel. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49:649–656. doi: 10.1021/es5046309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zeng J., Xuan Y. Enhanced solar thermal conversion and thermal conduction of MWCNT-SiO2/Ag binary nanofluids. Appl. Energy. 2018;212:809–819. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.12.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gu G., Xu J., Wu Y., Chen M., Wu L. Synthesis and antibacterial property of hollow SiO2/Ag nanocomposite spheres. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;359:327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flores J., Torres V., Popa M., Crespo D., Calderon-Moreno J. Preparation of core–shell nanospheres of silica–silver: SiO2@Ag. J. Non-Crystalline Solids. 2008;354:5435–5439. doi: 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2008.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lambert S., Cellier C., Grange P., Pirard J.-P., Heinrichs B. Synthesis of Pd/SiO2, Ag/SiO2, and Cu/SiO2 cogelled xerogel catalysts: Study of metal dispersion and catalytic activity. J. Catal. 2004;221:335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2003.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu C., Yang D., Jiao Y., Tian Y., Wang Y., Jiang Z. Biomimetic Synthesis of TiO2–SiO2–Ag Nanocomposites with Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2013;5:3824–3832. doi: 10.1021/am4004733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Deng Z., Chen M., Wu L. Novel Method to Fabricate SiO2/Ag Composite Spheres and Their Catalytic, Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Properties. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2007;111:11692–11698. doi: 10.1021/jp073632h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abduraimova A., Molkenova A., Duisembekova A., Mulikova T., Kanayeva D., Atabaev T. Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB)-Loaded SiO2–Ag Mesoporous Nanocomposite as an Efficient Antibacterial Agent. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:477. doi: 10.3390/nano11020477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu J., Li S., Fang Y., Zhu Z. Boosting antibacterial activity with mesoporous silica nanoparticles supported silver nanoclusters. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;555:470–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2019.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fullenkamp D.E., Rivera J.G., Gong Y.-K., Lau K.A., He L., Varshney R., Messersmith P.B. Mussel-inspired silver-releasing antibacterial hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3783–3791. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Otari S.V., Patil R.M., Waghmare S.R., Ghosh S.J., Pawar S.H. A novel microbial synthesis of catalytically active Ag–alginate biohydrogel and its antimicrobial activity. Dalton Trans. 2013;42:9966–9975. doi: 10.1039/c3dt51093j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rawat K.A., Majithiya R.P., Rohit J.V., Basu H., Singhal R.K., Kailasa S.K. Mg2+ ion as a tuner for colorimetric sensing of glyphosate with improved sensitivity via the aggregation of 2-mercapto-5-nitrobenzimidazole capped silver nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2016;6:47741–47752. doi: 10.1039/C6RA06450G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hassanien R., Al-Hinai M., Al-Said S.A.F., Little R., Šiller L., Wright N.G., Houlton A., Horrocks B.R. Preparation and Characterization of Conductive and Photoluminescent DNA-Templated Polyindole Nanowires. ACS Nano. 2010;4:2149–2159. doi: 10.1021/nn9014533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shoeb M., Mobin M., Rauf M.A., Owais M., Naqvi A.H. In Vitro and in Vivo Antimicrobial Evaluation of Graphene–Polyindole (Gr@PIn) Nanocomposite against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Pathogen. ACS Omega. 2018;3:9431–9440. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b00326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xiao W., Xu J., Liu X., Hu Q., Huang J. Antibacterial hybrid materials fabricated by nanocoating of microfibril bundles of cellulose substance with titania/chitosan/silver-nanoparticle composite films. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2013;1:3477–3485. doi: 10.1039/c3tb20303d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liang X., Sun M., Li L., Qiao R., Chen K., Xiao Q., Xu F. Preparation and antibacterial activities of polyaniline/Cu0.05Zn0.95O nanocomposites. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:2804–2811. doi: 10.1039/c2dt11823h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.ISO . ISO 22196—Measurement of Antibacterial Activity on Plastics and Other Non-Porous Surfaces. ISO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 76.ISO . ISO 21702—Measurement of Antiviral Activity on Plastics and Other Non-Porous Surfaces. ISO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Frisch M.J., Trucks G.W., Schlegel H.B., Scuseria G.E., Robb M.A., Cheeseman J.R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Pe-tersson G.A., Nakatsuji H., et al. Gaussian 09 2016. Gaussian; Wallingford, CT, USA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tinio J.V.G., Simfroso K.T., Peguit A.D.M.V., Candidato R.T. Influence of OH−Ion Concentration on the Surface Morphology of ZnO-SiO2Nanostructure. J. Nanotechnol. 2015;2015:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2015/686021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ferreira C.S., Santos P.L., Bonacin J.A., Passos R.R., Pocrifka L.A. Rice Husk Reuse in the Preparation of SnO2/SiO2Nanocomposite. Mater. Res. 2015;18:639–643. doi: 10.1590/1516-1439.009015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tran T.N., Pham T.V.A., Le M.L.P., Nguyen T.P.T., Tran V.M. Synthesis of amorphous silica and sulfonic acid functionalized silica used as reinforced phase for polymer electrolyte membrane. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2013;4:045007. doi: 10.1088/2043-6262/4/4/045007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Musić S., Filipović-Vinceković N., Sekovanić L. Precipitation of amorphous SiO2 particles and their properties. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2011;28:89–94. doi: 10.1590/S0104-66322011000100011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.He X., Zhang R., Yang C., Rong Y., Huang G. Study on orientation in EVA/Fe3O4 composite hot-melt adhesives. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2013;44:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2013.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bidsorkhi H.C., Soheilmoghaddam M., Pour R.H., Adelnia H., Mohamad Z. Mechanical, thermal and flammability properties of ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA)/sepiolite nanocomposites. Polym. Test. 2014;37:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.polymertesting.2014.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Van Hoang V. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Amorphous SiO2Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:12649–12656. doi: 10.1021/jp074237u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Borowicz P., Taube A., Rzodkiewicz W., Latek M., Gierałtowska S. Raman Spectra of High-κDielectric Layers Investigated with Micro-Raman Spectroscopy Comparison with Silicon Dioxide. Sci. World J. 2013;2013:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2013/208081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chernev B.S., Hirschl C., Eder G.C. Non-Destructive Determination of Ethylene Vinyl Acetate Cross-Linking in Photovoltaic (PV) Modules by Raman Spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 2013;67:1296–1301. doi: 10.1366/13-07085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shen Y., Chen Z., Zhou Y., Lei Z., Liu Y., Feng W., Zhang Z., Chen H. Solvent-free electrically conductive Ag/ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) composites for paper-based printable electronics. RSC Adv. 2019;9:19501–19507. doi: 10.1039/C9RA02593F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Peike C., Kaltenbach T., Weiß K.-A., Koehl M. Non-destructive degradation analysis of encapsulants in PV modules by Raman Spectroscopy. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 2011;95:1686–1693. doi: 10.1016/j.solmat.2011.01.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shimoyama M., Maeda H., Matsukawa K., Inoue H., Ninomiya T., Ozaki Y. Discrimination of ethylene/vinyl acetate copolymers with different composition and prediction of the vinyl acetate content in the copolymers using Fourier-transform Raman spectroscopy and multivariate data analysis. Vib. Spectrosc. 1997;14:253–259. doi: 10.1016/S0924-2031(97)00010-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kuna L., Eder G.C., Leiner C., Peharz G. Reducing shadowing losses with femtosecond-laser-written deflective optical elements in the bulk of EVA encapsulation. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 2014;23:1120–1130. doi: 10.1002/pip.2530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hirschl C., Biebl–Rydlo M., DeBiasio M., Mühleisen W., Neumaier L., Scherf W., Oreski G., Eder G., Chernev B., Schwab W., et al. Determining the degree of crosslinking of ethylene vinyl acetate photovoltaic module encapsulants—A comparative study. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 2013;116:203–218. doi: 10.1016/j.solmat.2013.04.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sakthisabarimoorthi A., Dhas S.M.B., Jose M. Nonlinear optical properties of Ag@SiO2 core-shell nanoparticles investigated by continuous wave He-Ne laser. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018;212:224–229. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2018.03.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sun D.-H., Lu P., Zhang J.-L., Liu Y.-L., Ni J.-Z. Synthesis of the Fe3O4@SiO2@SiO2-Tb(PABA)3 luminomagnetic microspheres. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2011;11:9774–9779. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2011.5265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ramalla I., Gupta R.K., Bansal K. Effect on superhydrophobic surfaces on electrical porcelain insulator, improved technique at polluted areas for longer life and reliability. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2015;4:509–519. doi: 10.14419/ijet.v4i4.5405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Liang Y., Ouyang J., Wang H., Wang W., Chui P., Sun K. Synthesis and characterization of core–shell structured SiO2@YVO4:Yb3+, Er3+ microspheres. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012;258:3689–3694. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2011.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Siddiqui M.R.H., Adil S., Assal M., Ali R., Al-Warthan A.A. Synthesis and Characterization of Silver Oxide and Silver Chloride Nanoparticles with High Thermal Stability. Asian J. Chem. 2013;25:3405–3409. doi: 10.14233/ajchem.2013.13874. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Oje A.I., Ogwu A., Mirzaeian M., Tsendzughul N. Electrochemical energy storage of silver and silver oxide thin films in an aqueous NaCl electrolyte. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2018;829:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2018.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Aguilar-Reynosa A., Romaní A., Rodríguez-Jasso R.M., Aguilar C.N., Garrote G., Ruiz H.A. Microwave heating processing as alternative of pretreatment in second-generation biorefinery: An overview. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017;136:50–65. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2017.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ramírez-Hernández A., Aguilar-Flores C., Aparicio-Saguilán A. Fingerprint analysis of FTIR spectra of polymers containing vinyl acetate. DYNA. 2019;86:198–205. doi: 10.15446/dyna.v86n209.77513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Marcilla A., Gómez A., Menargues S. TGA/FTIR study of the catalytic pyrolysis of ethylene–vinyl acetate copolymers in the presence of MCM-41. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2005;89:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2005.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Marcilla A., Gómez A., Menargues S. TGA/FTIR study of the evolution of the gases evolved in the catalytic pyrolysis of ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymers. Comparison among different catalysts. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2005;89:454–460. doi: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2005.01.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hoang T., Chinh N.T., Trang N.T.T., Hang T.T.X., Thanh D.T.M., Hung D.V., Ha C.-S., Aufray M. Effects of maleic anhydride grafted ethylene/vinyl acetate copolymer (EVA) on the properties of EVA/silica nanocomposites. Macromol. Res. 2013;21:1210–1217. doi: 10.1007/s13233-013-1157-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Poljanšek I., Fabjan E., Burja K., Kukanja D. Emulsion copolymerization of vinyl acetate-ethylene in high pressure reactor-characterization by inline FTIR spectroscopy. Prog. Org. Coat. 2013;76:1798–1804. doi: 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2013.05.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Iijima M., Omori S., Hirano K., Kamiya H. Free-standing, roll-able, and transparent silicone polymer film prepared by using nanoparticles as cross-linking agents. Adv. Powder Technol. 2013;24:625–631. doi: 10.1016/j.apt.2012.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jia Y., Wang H., Tian K., Li R., Xu Z., Jiao J., Cao L., Wu Y. A combined interfacial and in-situ polymerization strategy to construct well-defined core-shell epoxy-containing SiO2-based microcapsules with high encapsulation loading, super thermal stability and nonpolar solvent tolerance. Int. J. Smart Nano Mater. 2016;7:221–235. doi: 10.1080/19475411.2016.1261954. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Duquesne S., Jama C., Le Bras M., Delobel R., Recourt P., Gloaguen J. Elaboration of EVA–nanoclay systems—characterization, thermal behaviour and fire performance. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2003;63:1141–1148. doi: 10.1016/S0266-3538(03)00035-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zanetti M., Camino G., Thomann R., Mülhaupt R. Synthesis and thermal behaviour of layered silicate–EVA nanocomposites. Polymer. 2001;42:4501–4507. doi: 10.1016/S0032-3861(00)00775-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shimoyama M., Hayano S., Matsukawa K., Inoue H., Ninomiya T., Ozaki Y. Discrimination of ethylene/vinyl acetate copolymers with different composition and prediction of the content of vinyl acetate in the copolymers and their melting points by near-infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 1998;36:1529–1537. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0488(19980715)36:9<1529::AID-POLB10>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Watari M., Ozaki Y. Calibration Models for the Vinyl Acetate Concentration in Ethylene-Vinyl Acetate Copolymers and its On-Line Monitoring by Near-Infrared Spectroscopy and Chemometrics: Use of Band Shifts Associated with Variations in the Vinyl Acetate Concentration to Improve the Models. Appl. Spectrosc. 2005;59:912–919. doi: 10.1366/0003702054411571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li H.-Y., Perret-Aebi L.-E., Théron R., Ballif C., Luo Y., Lange R.F.M. Optical transmission as a fast and non-destructive tool for determination of ethylene-co-vinyl acetate curing state in photovoltaic modules. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 2011;21:187–194. doi: 10.1002/pip.1175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Paul K.K., Ghosh R., Giri P.K. Mechanism of strong visible light photocatalysis by Ag2O-nanoparticle-decorated monoclinic TiO2(B) porous nanorods. Nanotechnology. 2016;27:315703. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/27/31/315703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Deng A., Zhu Y. Synthesis of TiO2/SiO2/Ag/Ag2O and TiO2/Ag/Ag2O nanocomposite spheres with photocatalytic performance. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2018;44:4227–4243. doi: 10.1007/s11164-018-3365-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Shume W.M., Murthy H.C.A., Zereffa E.A. A Review on Synthesis and Characterization of Ag2O Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Applications. J. Chem. 2020;2020:1–15. doi: 10.1155/2020/5039479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Spreadborough J., Christian J.W. High-temperature X-ray diffractometer. J. Sci. Instrum. 1959;36:116–118. doi: 10.1088/0950-7671/36/3/302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hui S., Chaki T.K., Chattopadhyay S. Effect of silica-based nanofillers on the properties of a low-density polyethylene/ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer based thermoplastic elastomer. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008;110:825–836. doi: 10.1002/app.28537. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Filip D., Macocinschi D., Paslaru E., Munteanu B.S., Dumitriu R.P., Lungu M., Vasile C. Polyurethane biocompatible silver bionanocomposites for biomedical applications. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2014;16:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11051-014-2710-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.ISO . ISO 4892-2:2013 Plastics—Methods of Exposure to Laboratory Light Sources—Part 2: Xenon-arc Lamps. ISO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Da Silva J.S., Machado T.R., Martins T.A., Assis M., Foggi C.C., Macedo N.G., Beltrán-Mir H., Cordoncillo E., Andrés J., Longo E. α-AgVO3 Decorated by Hydroxyapatite (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2): Tuning Its Photoluminescence Emissions and Bactericidal Activity. Inorg. Chem. 2019;58:5900–5913. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b00249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Assis M., Robeldo T., Foggi C.C., Kubo A.M., Mínguez-Vega G., Condoncillo E., Beltran-Mir H., Torres-Mendieta R., Andrés J., Oliva M., et al. Ag Nanoparticles/α-Ag2WO4 Composite Formed by Electron Beam and Femtosecond Irradiation as Potent Antifungal and Antitumor Agents. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46159-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sun R., Chen Z., Yang Y., Peng J., Zheng T. Effects and mechanism of SiO2 on photocatalysis and super hydrophilicity of TiO2 films prepared by sol-gel method. Mater. Res. Express. 2018;6:046409. doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/aafa8c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yao C., Zhu J. Synthesis, Characterization and Photocatalytic Activity of Au/SiO2@TiO2 Core-Shell Microspheres. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2020;31:589–596. doi: 10.21577/0103-5053.20190222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Salgado B.C.B., Valentini A. Evaluation of the Photocatalytic Activity of SiO2@TiO2 Hybrid Spheres in the Degradation of Methylene Blue and Hydroxylation of Benzene: Kinetic and Mechanistic STUDY. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2019;36:1501–1518. doi: 10.1590/0104-6632.20190364s20190139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hou Y.-X., Abdullah H., Kuo D.-H., Leu S.-J., Gultom N.S., Su C.-H. A comparison study of SiO2 /nano metal oxide composite sphere for antibacterial application. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018;133:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2017.09.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Shen J.-N., Ruan H.-M., Wu L.-G., Gao C.-J. Preparation and characterization of PES–SiO2 organic–inorganic composite ultrafiltration membrane for raw water pretreatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2011;168:1272–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2011.02.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yu H., Zhang Y., Zhang J., Zhang H., Liu J. Preparation and antibacterial property of SiO2–Ag/PES hybrid ultrafiltration membranes. Desalin. Water Treat. 2013;51:3584–3590. doi: 10.1080/19443994.2012.752900. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author: J.A., upon reasonable request.