ABSTRACT

Social determinants of health are responsible for a large proportion of disease which disproportionately affects deprived population groups, resulting in striking disparities in life expectancy and quality of life. Even systems with universal access to healthcare (such as the UK's NHS) can only mitigate some consequences of health inequalities. Instead substantial societal measures are required both to reduce harmful exposures and to improve standards of housing, education, work, nutrition and exercise. The case for such measures is widely accepted among healthcare professionals but, in wider discourse, scepticism has remained about the role of government and society in improving life chances along with the belief that responsibility for health and wellbeing should rest with individuals themselves. The stark inequalities exposed by the coronavirus pandemic could be an opportunity to challenge this thinking. This paper argues that doctors should do more to persuade others of the need to address health inequalities and that to achieve this, it is important to understand the ethical and philosophical perspectives that are sceptical of such measures. An approach to gaining greater support for interventions to address health inequalities is presented along with reflections on effective political advocacy which is consistent with physicians’ professional values.

KEYWORDS: health inequalities, ethics, politics, advocacy

Introduction

To many doctors, it is self-evident that inequalities in health are an outrageous injustice. Too often, tinkering with pills, procedures and advice feels wholly inadequate against the social determinates of health that incur avoidable disability, misery and loss of life. Outside the profession, the case for addressing taking action is less well understood. Persuading others of the case for change requires that we understand and engage with those who remain sceptical of interventions to address health inequalities. This paper briefly considers some ethical and philosophical perspectives on health inequalities before considering an approach to political advocacy which is consistent with the professional values of physicians.

What are the ethical arguments for and against addressing health inequalities?

Followers of the philosopher John Rawls have applied his theory of ‘justice as fairness’ to health policy, justifying universal access to healthcare as a necessary condition for equality of opportunity.1 Of course, healthcare usually can only hope to mitigate chronic disease rather than offer cure, and even in societies like the UK (with notionally universal access), profound inequalities in health persist. Therefore, a more recent Rawlsian approach has been to emphasise equality of opportunity for health itself, rather than for just healthcare.2

For doctors, the idea that health ought to be safeguarded to ensure equality of opportunity might seem peculiar. Promoting good health is an important end in its own right, not merely a means for other societal goals. Accordingly, the epidemiologist Michael Marmot has characterised avoidable inequality in health between social groups as necessarily unfair and requiring challenge.3 Tackling such inequality is, for Marmot, a moral imperative. While measures to improve societal health are largely uncontroversial among many working within healthcare, such views do not necessarily reflect broader opinion. It is a particular hazard of our time to allow the opinions that reverberate in professional and social media ‘echo chambers’ to be confused for a wider consensus.

Some academics insist that the responsibility for improving the health of those worst off must sit with healthcare systems rather than with a wider policy agenda. Such thinkers have tended to believe that technological innovations in healthcare are the best way to improve health. According to this analysis, technological breakthroughs in health are more likely to arise in a competitive free market economy, and that ambitious social policies or redistribution of resources to improve the wellbeing of disadvantaged citizens is misguided.4 Policies intended to protect health have also been perceived as a threat to freedom. Christopher Snowdon has persuasively invoked the philosopher John Stuart Mill to castigate what he sees as unjustified encroachments on individual or market liberty as illegitimate, no matter how well intentioned. For Snowdon, the business of public health should remain restricted to basic functions (such as ensuring water is safe to drink). In his account, the public health establishment have become meddling ‘killjoys’ absurdly preoccupied with issues that should remain the preserve of individual judgement, like obesity, alcohol and smoking.5

The prevention paradox

Snowden's perception that a political bias exists in the medical profession has some justification, but this may be partly because social solidarity has a sound basis in epidemiology. In The strategy of preventive medicine, Geoffrey Rose demonstrated that populations are discrete communities that manifest different distributions of behaviours and health outcomes.6 Disease prevalence forms a gradient within these populations. Therefore, although targeting interventions to those at the greatest risk feels intuitively rational, since those who are at greatest risk constitute a minority of the population, cases among those at low to moderate risk often outnumber those who are at high risk. Those who face the greatest hardship (such as people who are homeless and those who have had adverse childhood experiences) do require the most intensive support but it is also important to help level the entire gradient of health outcomes. A whole-population perspective involves considering disparities across the spectrum of income distribution, not just that which exists between richest and poorest.

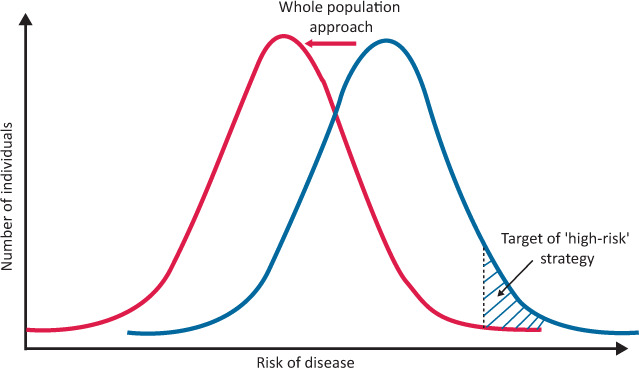

From this perspective, the most efficient and effective means of reducing disease within a population is not only to target individuals, but to effect a shift away from harmful exposures for the entire population (Fig 1). However, those who are not at high risk might legitimately question why they should be subject to restrictions or pay higher taxes to improve societal health. Rose hoped that in time, public opinion and political will would be guided by evidence for the necessity of measures that addressed the health of society as a whole. After 30 years this hasn't happened. Views that emphasise individual responsibility continue to predominate in our national media and discourse. We need to understand these views and to engage with them.7

Fig 1.

Strategy of preventative medicine. The relatively small hatched area under the blue population curve represents the limits that an exclusive focus on the ‘high-risk’ strategy of disease prevention. Shifting the risk for the entire community (red arrow and red population curve) can yield much greater overall decreases in disease. However, the strategies are not mutually exclusive and it is justifiable to focus efforts on deprived populations at greatest risk as well as reducing risk for the entire community.

Engaging policy makers is necessary, but not sufficient

As a profession, we are adept at making the case for measures to benefit population health by presenting evidence directly to policy makers. Such high-level interventions are vital but do little to persuade the public at large. Even those who live at ‘the deep end’ of the social gradient are often loath to regard themselves to be victims of societal injustice and may instead blame bad luck or ‘bad choices’.

Presenting evidence to policy makers is crucial but, without influencing wider opinion, such efforts are often not enough to achieve change because:

those who we seek to persuade face additional pressures and motivations other than ‘doing good’ (such as winning elections or competing ideological beliefs)

those who we seek to benefit from policy interventions are likely to resent, or feel condescended to, when measures are implemented ‘for their own good’

efficacious measures (such as minimum alcohol unit pricing) are vulnerable to criticism as ‘nanny state’ impositions on individual autonomy.

Engaging the public with a narrative of ‘fairness’

We need to engage directly with widespread scepticism of interventions to improve population health. Despite a difference in life expectancy of almost 10 years between our least deprived and most deprived communities, before the pandemic, health inequalities received little attention in the national discourse.8 Since then socioeconomic and racial disparities have been exposed by SARS-CoV-2 as never before.9 This provides an unprecedented opportunity to make a case for measures to address these inequalities.

To rectify health inequalities, we have to persuade the public and politicians that the status quo is grossly unfair and must not be tolerated. Health inequalities should be framed as an issue of justice and we should learn to partner with those who face the greatest adversity to demand a fairer and healthier society. A message that focuses only on measures which restrict access to harmful behaviours can be easily dismissed as nanny state paternalism. The role of such ‘negative’ measures should be promoted alongside ‘positive’ initiatives that allow individuals to increase control over their own lives through adequate housing, nutrition, and access to exercise, education and employment.

Doctors as advocates

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) has recently established a policy group on health inequalities and has brought almost 80 organisations together to form the Inequalities in Health Alliance. The alliance has already called on the government to undertake three specific actions.10 Hopefully this work will be supported by many members and fellows. Doctors are uniquely qualified to make the case for addressing health inequalities. Our expertise in communicating evidence and the power of professional testimony that we can offer about the effects of deprivation are desperately needed to overcome the assumptions and ideologies that impede change.

Reticence about promoting ‘political’ views is entirely understandable. It is appropriate that, as doctors, we should hold ourselves to different standards than politicians and pundits. Expressing views that are political does not require that we become ‘party political’.11 Indeed doctors who eschew partisanship may well be the most persuasive.

Airing views in public can be hazardous. Contested interpretations of evidence are often the result of differences in values and beliefs that should be understood and respected. Lapses in courtesy are not only at odds with our values as a profession, they are also likely to be counterproductive.12 But doctors who have the confidence and skills to speak up against health inequalities are fulfilling an important professional responsibility.13 However unseemly entering the political fray may appear, health is already resolutely political and remaining silent is also a decision with consequences. The concluding sentences of Rose's The strategy of preventive medicine remain apt:

The primary determinants of disease are mainly economic and social, and therefore its remedies must also be economic and social. Medicine and politics cannot and should not be kept apart.6

Conflicts of interest

Stephen H Bradley is a member of the executive committee of the Fabian Society which is a think tank affiliated to the Labour Party and is a member of the reference group for the RCP's health inequalities policy group. Stephen H Bradley receives PhD funding from Cancer Research UK as part of the CanTest Collaborative [C8640/A23385].

References

- 1.Daniels N. Just health care. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Segall S. Equality and opportunity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marmot M. Fair society health lives. In: Eyal NM, Hurst SA, Norheim OF, et al. (eds). Inequalities in health: concepts, measures, and ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canning D, Bowser D. Investing in health to improve the wellbeing of the disadvantaged: Reversing the argument of Fair Society, Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review). Social Science & Medicine 2010;71:1223–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snowdon C. Killjoys: a critique of paternalism. London: Institute of Economic Affairs, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose G. The strategy of preventive medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley SH. Sticking up for nanny. Br J Gen Pract 2019;69:449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iacobucci G. Life expectancy gap between rich and poor in England widens. BMJ 2019;364:l1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020;584:430–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Royal College of Physicians . Inequalities in Health Alliance. RCP. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/inequalities-health-alliance [Accessed 03 November 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawson E. Debrief: The political doctor. Br J Gen Pract 2020;70:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkins N. A Twitter put-down might win ‘likes’, but it won't change minds. Guardian 2018. www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/jul/04/university-of-reading-twitter-putdown-refugee-plan [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliver D. David Oliver: Being labelled an ‘activist’ is a badge of honour. BMJ 2020;371:m4186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]