Abstract

Seasonal flu vaccination is one of the most important strategies for preventing influenza. The attitude towards flu vaccination in light of the COVID-19 pandemic has so far been studied in the literature mostly with the help of surveys and questionnaires. Whether a person chooses to be vaccinated or not during the COVID-19 pandemic, however, speaks louder than any declaration of intention. In our teaching hospital, we registered a statistically significant increase in flu vaccination coverage across all professional categories between the 2019/2020 and the 2020/2021 campaign (24.19% vs. 54.56%, p < 0.0001). A linear regression model, based on data from four previous campaigns, predicted for the 2020/2021 campaign a total flu vaccination coverage of 30.35%. A coverage of 54.46% was, instead, observed, with a statistically significant difference from the predicted value (p < 0.0001). The COVID-19 pandemic can, therefore, be considered as an incentive that significantly and dramatically increased adherence to flu vaccination among our healthcare workers.

Keywords: flu vaccination, COVID-19, healthcare workers, adherence, vaccination coverage

Seasonal flu vaccination is one of the most important strategies for preventing influenza and reducing its healthcare, social, and economic impact [1,2,3,4,5]. Although influenza’s disease burden varies from year to year, evidence clearly shows that vaccination can reduce flu severity and prevent hospitalizations—critical considerations at a time when the health care system is burdened by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [6].

COVID-19, therefore, should act as a great incentive for flu vaccination.

But is it really so? The attitude towards flu vaccination in light of the COVID-19 pandemic has so far been studied in literature mostly with the help of surveys and questionnaires [7,8,9,10]. These are very useful in identifying possible causes of hesitancy and in helping to plan vaccination strategies. A study by Wang et al., for instance, analysed COVID-19 vaccination intention in relation to flu vaccine uptake and classified the reasons for refusal as “suspicion on efficacy”, “effectiveness and safety”, “believing it unnecessary”, and “no time to take it” [7].

Whether a person chooses to be vaccinated or not during the COVID-19 pandemic, however, speaks louder than any declaration regarding his/her possible attitude towards it. A recent study analysed flu vaccine uptake in relation to COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine hesitancy among nurses [11].

We therefore proposed studying in our teaching hospital, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario “A. Gemelli” IRCCS (FPG), whether any significant increase in flu vaccination coverage occurred between last year’s flu vaccination campaign and this year’s campaign, marked by the COVID-19 pandemic.

As we can see from Table 1, there has been a statistically significant increase (tested with Pearson’s chi-square) in flu vaccination coverage across all categories, among both healthcare and non-healthcare workers. This could mean that COVID-19 acted as an incentive to flu vaccination beyond specific health-related education.

Table 1.

Vaccinated subjects by professional category campaign years and p-value (absolute and relative frequencies).

| 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional Category | Vaccinated | Total | Vaccinated | Total | p-Value |

| Medical Doctors | 483 (36.60%) | 1320 | 819 (75.21%) | 1089 | <0.0001 |

| Nursing staff | 369 (17.35%) | 2127 | 970 (48.04%) | 2019 | <0.0001 |

| Other healthcare workers | 222 (17.01%) | 1305 | 881 (54.96%) | 1603 | <0.0001 |

| Medical Residents | 549 (45.22%) | 1214 | 687 (55.90%) | 1229 | 0.0025 |

| Total healthcare workers | 1026 (24.19%) | 4241 | 2556 (54.46%) | 4685 | <0.0001 |

| Administrative staff/non-healthcare workers | 106 (10.01%) | 1059 | 666 (54.06%) | 1232 | <0.0001 |

On a further note, younger generations tend to be more open to healthy lifestyles and good practices such as this [12].

Flu vaccination was offered to healthcare students across the two campaigns as well, with, respectively, 657 and 688 vaccinated students (+4.72%). The same vaccination time slots were offered across the two campaigns, and therefore a significant increase could not be observed, however much higher the demand was.

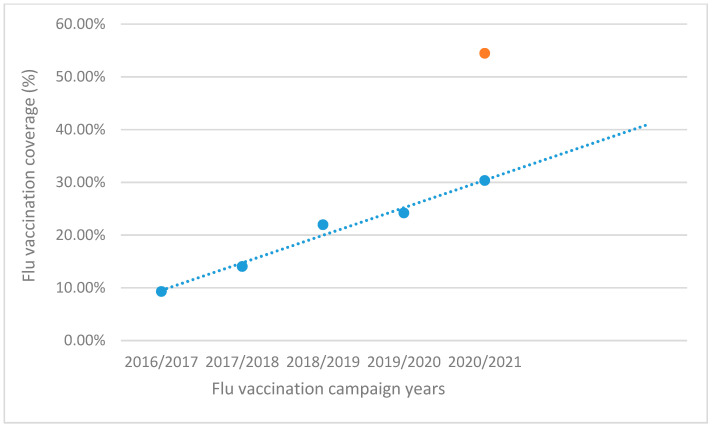

Many efforts have been made in the past to increase adherence to this public health practice among our healthcare workers, with steady but slow results up to 2019/2020, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flu vaccination coverage across 5 campaigns with a 4-campaign (2016/2017–2019/2020) linear regression line, 2020/2021 coverage observed (orange) vs. predicted (blue).

Given the same conditions that had been present up to the start of the pandemic, a linear regression model, based on the data from the first 4 campaigns, predicted a total flu vaccination coverage of 30.35% (blue in Figure 1). A significant departure from the observed 54.46% coverage (orange in Figure 1) was found (p < 0.0001).

Although the analysis was performed without taking into account other possible confounders, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a major difference factor between 2020/2021 campaign and all other ones. It can, therefore, be regarded as an incentive that significantly and dramatically increased adherence to a good public health practice such as flu vaccination among our healthcare workers.

In conclusion, we hope that these results are indicative of a disposition towards future COVID-19 vaccination as well, as shown by other studies [11], even considering all the possible limitations connected to the analogy between this vaccine and the flu vaccine.

Let the numbers speak for themselves.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and Project administration, P.L., G.D.; Investigation, M.D.P., D.P., E.C., V.B., M.C.N., F.D.; Methodology, M.D.P.; Writing—original draft, M.D.P.; Writing—review and editing, M.D.P., M.C.N.; Visualization, M.D.P.; Software, M.D.P.; Data curation, E.C., D.P., V.B., M.C.N., F.D., M.D.P.; Formal analysis, M.D.P.; Resources: G.V., P.L., A.C., M.P., M.Z., A.S.; Validation, G.D., P.L.; Supervision, A.S., G.V., A.C., M.Z., M.P., G.D., P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee (Prot. n. 2275/21.; ID 3706) of the Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS and by the Internal Board of Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Barbara A., La Milia D.I., Di Pumpo M., Tognetto A., Tamburrano A., Vallone D., Viora C., Cavalieri S., Cambieri A., Moscato U., et al. Strategies to Increase Flu Vaccination Coverage among Healthcare Workers: A 4 Years Study in a Large Italian Teaching Hospital. Vaccines. 2020;8:85. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8010085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rittle C. Can Increasing Adult Vaccination Rates Reduce Lost Time and Increase Productivity? Work. Heal. Saf. 2014;62:508–515. doi: 10.3928/21650799-20140909-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osterholm M.T., Kelley N.S., Sommer A., Belongia E.A. Efficacy and Effectiveness of Influenza Vaccines: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012;12:36–44. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gianino M.M., Politano G., Scarmozzino A., Charrier L., Testa M., Giacomelli S., Benso A., Zotti C.M. Estimation of Sickness Absenteeism among Italian Healthcare Workers during Seasonal Influenza Epidemics. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0182510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corson S., Robertson C., Reynolds A., McMenamin J. Modelling the Population Effectiveness of the National Seasonal Influenza Vaccination Programme in Scotland: The Impact of Targeting All Individuals Aged 65 Years and Over. Influenza Other Respi. Viruses. 2019;13:354–363. doi: 10.1111/irv.12583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaklevic M.C. Flu Vaccination Urged during COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;324 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.15444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang K., Wong E.L.Y., Ho K.F., Cheung A.W.L., Chan E.Y.Y., Yeoh E.K., Wong S.Y.S. Intention of Nurses to Accept Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination and Change of Intention to Accept Seasonal Influenza Vaccination during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccine. 2020;38:7049–7056. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pastorino R., Villani L., Mariani M., Ricciardi W., Graffigna G., Boccia S. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Flu and COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions among University Students. Vaccines. 2021;9:70. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domnich A., Cambiaggi M., Vasco A., Maraniello L., Ansaldi F., Baldo V., Bonanni P., Calabrò G.E., Costantino C., de Waure C., et al. Attitudes and Beliefs on Influenza Vaccination during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Results from a Representative Italian Survey. Vaccines. 2020;8:711. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8040711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sokol R.L., Grummon A.H. COVID-19 and Parent Intention to Vaccinate Their Children against Influenza. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-022871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwok K.O., Li K.K., Wei W.I., Tang A., Wong S.Y.S., Lee S.S. Influenza Vaccine Uptake, COVID-19 Vaccination Intention and Vaccine Hesitancy among Nurses: A Survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021;114:103854. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehmann B.A., Ruiter R.A.C., Wicker S., Chapman G., Kok G. Medical Students’ Attitude towards Influenza Vaccination. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015;15:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0929-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.