Abstract

In Streptomyces, antibiotic biosynthesis is triggered in phosphate limitation that is usually correlated with energetic stress. Polyphosphates constitute an important reservoir of phosphate and energy and a better understanding of their role in the regulation of antibiotic biosynthesis is of crucial importance. We previously characterized a gene, SLI_4384/ppk, encoding a polyphosphate kinase, whose disruption greatly enhanced the weak antibiotic production of Streptomyces lividans. In the condition of energetic stress, Ppk utilizes polyP as phosphate and energy donor, to generate ATP from ADP. In this paper, we established that ppk is co-transcribed with its two downstream genes, SLI_4383, encoding a phosin called PptA possessing a CHAD domain constituting a polyphosphate binding module and SLI_4382 encoding a nudix hydrolase. The expression of the ppk/pptA/SLI_4382 operon was shown to be under the positive control of the two-component system PhoR/PhoP and thus mainly expressed in condition of phosphate limitation. However, pptA and SLI_4382 can also be transcribed alone from their own promoter. The deletion of pptA resulted into earlier and stronger actinorhodin production and lower lipid content than the disruption of ppk, whereas the deletion of SLI_4382 had no obvious phenotypical consequences. The disruption of ppk was shown to have a polar effect on the expression of pptA, suggesting that the phenotype of the ppk mutant might be linked, at least in part, to the weak expression of pptA in this strain. Interestingly, the expression of phoR/phoP and that of the genes of the pho regulon involved in phosphate supply or saving were strongly up-regulated in pptA and ppk mutants, revealing that both mutants suffer from phosphate stress. Considering the presence of a polyphosphate binding module in PptA, but absence of similarities between PptA and known exo-polyphosphatases, we proposed that PptA constitutes an accessory factor for exopolyphosphatases or general phosphatases involved in the degradation of polyphosphates into phosphate.

Keywords: phosphate, polyphosphates, CHAD domain, antibiotic, pho regulon

1. Introduction

Streptomyces are Gram-positive, filamentous soil bacteria, of great medical and economic importance since they are able to produce a great variety of bio-active molecules useful to human health or agriculture [1,2]. The biosynthesis of these molecules usually takes place when growth slows down or stops and is thought to be triggered by some nutritional limitation [3]. One of the most efficient triggers of antibiotic production is a limitation in phosphate that is correlated with a low ATP content (weak energetic state) [4,5]. Conversely, antibiotic production is strongly repressed in condition of high phosphate availability. Inorganic phosphate being often a limiting nutriment in the environment, living systems have developed ways to store it efficiently as polyphosphates, in stressful conditions [6,7]. Polyphosphates (polyP) are linear polymers of phosphate linked by highly energetic phosphoanhydride bonds. Their synthesis relies, at least in part, on the action of polyphosphate kinases, enzymes able to polymerize the γ phosphate of ATP into polyphosphate [8]. However, since some polyP were still present in the ppk mutant of E. coli [9], alternative mechanisms of polyP synthesis are likely to exist. The accumulation of large quantities of polyP was noticed in phoU mutants of E. coli [10] and was correlated with an activation of Pi up-take by the PstSCAB transport system. This suggested that active Pi up-take contributes to polyP synthesis. Polyphosphates are involved in the resistance to various stresses [11,12,13] and constitute an important intracellular reserve of phosphate and energy that can be mobilized in condition of phosphate and energetic stress [14]. In such conditions, polyphosphates can either be used as a phosphate and energy donor to generate ATP from ADP by enzymes possessing adenosine diphosphate kinase-like activities, such as Ppk (SCO4145/SLI_4383) in Streptomyces [15,16] or as a an inorganic phosphate supplier via its degradation by endo and/or exo-polyphosphate phosphatases. In Streptomyces species, antibiotic biosynthesis being triggered in condition of phosphate limitation, getting a better understanding of the role played by this important polymer in the regulation of antibiotic biosynthesis is of crucial importance.

We previously characterized the polyphosphate kinase (Ppk) encoding gene of S. lividans (SLI_4384) and demonstrated that, in vitro, Ppk can act either as a polyphosphate kinase, synthetizing polyphosphate from ATP, or as an adenosine diphosphate kinase, regenerating ATP from ADP and polyP, depending on the ATP/ADP ratio in the reaction mix [15]. In S. lividans, ppk is mainly expressed in Pi limitation and belongs to the Pho regulon [16,17]. In vivo, in Pi limitation, the polyP and ADP content of the ppk mutant was shown to be higher than that of the wt strain, suggesting the absence of a polyP-dependent regeneration process of ADP into ATP [5]. However, unexpectedly the ATP content of the strain was similar to that of the wt strain, suggesting that homeostatic processes, similar to those occurring in S. coelicolor, are being triggered in this strain in order to re-establish its energetic balance [5]. Consistently, in Pi limitation, the deletion of ppk led to a huge increase of the weak antibiotic production of S. lividans that was correlated with a lower total lipid content, as in S. coelicolor [5,15].

Interestingly, the proteins encoded by the two genes located immediately downstream of ppk have similarities with proteins possibly involved in polyP metabolism. SLI_4383/pptA encodes a protein bearing a conserved histidine α-helical domain (CHAD domain, PFAM PF05235). Proteins with CHAD domain are usually found associated with polyP granules in various organisms and are called phosins (Tumlirsch and Jendrossek 2017; Lorenzo-Orts, et al., 2019). The CHAD domain is thought to constitute a positively charged tunnel accommodating negatively charged polyP [18,19,20]. SLI_4382 encodes a protein of the nudix hydrolase family bearing similarities with enzymes involved in the cleavage of diadenosine hexaphosphate (Ap6A) into two molecules of ATP. The transcriptional situation of these three genes was determined in condition of phosphate limitation and proficiency in the wild type strain of S. lividans, in a phoP deletion mutant of this strain as well as in S. coelicolor. The disruption of SLI_4383/pptA and SLI_4382 was achieved in order to determine whether the corresponding proteins play a role in the regulation of antibiotic biosynthesis. This study unexpectedly revealed that pptA was weakly expressed in the ppk mutant and that its disruption had a higher impact on antibiotic production and total lipid content than the disruption of ppk. This suggested that the phenotype of the ppk mutant might be due, at least in part, to the weak expression of pptA in this strain.

2. Results

2.1. SLI_4382 and SLI_4383 Amino Acid Sequence Features

At the Sanger center, SLI_4382 is described as a 142 AA long protein belonging to the nudix hydrolase family and bearing similarities with enzymes involved in the cleavage of diadenosine hexaphosphate (Ap6A) into two molecules of ATP.

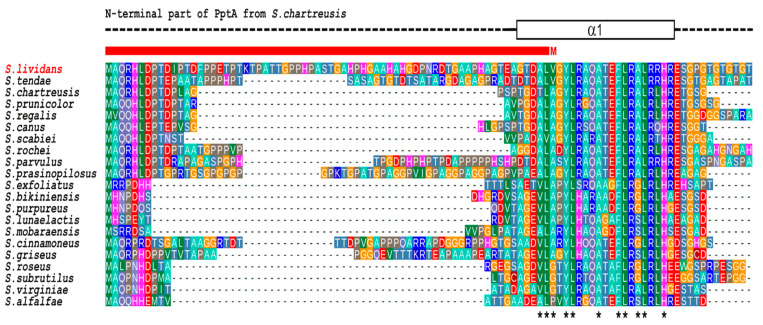

On its side, SLI_4383/PptA is described as a 388 AA long protein bearing a TTA leucine codon, possible target for bldA regulation [21] and possessing a conserved histidine alpha-helical domain (“CHAD” domain), considered as a polyphosphate binding module [19,20]. Interestingly, a comparison of the predicted protein product of SLI_4383/pptA (GenBank entry EFD67904.1) to putative orthologues from other Streptomyces species revealed the presence of N-terminal extensions of various length whose extremity is highly conserved in almost all orthologues but which is missing in the protein of S. lividans as it is annotated at the Sanger center (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Multiple sequence alignment of the N-terminal region of PptA-like proteins from various Streptomyces. The crystal structure of S. chartreusis PptA (PDB entry 6RN5) is schematically shown above the alignment. Dashed line represent structurally disordered areas, whereas the rectangle in solid lines represent the N-terminal α-helix (α1). Asterisks under the alignment indicate strongly conserved hydrophobic residues expected to play key roles in the stability of the protein fold. The red bar above the alignment indicates the region that is missing in the current database entry for PptA (SLI_4383) of S. lividans (GenBank entry EFD67904.1) due to incorrect assignment of the translation start site (M).

In the recently determined crystal structure of S. chartreusis PptA [20], this N terminal region comprises part of the first α-helix of the protein fold. Since in the S. lividans genome (GenBank entry GG657756.1) a highly similar sequence is present immediately upstream of the designated pptA translational start codon, it seems likely that this codon was erroneously assigned to an internal GTG (Val) codon. Predictions using various programs listed in Materials and Methods further confirmed this hypothesis and indicated that the most probable in frame GTG start codon is located 68 codons upstream of that provided at the Sanger center (GenBank entry EFD67904.1). S. lividans PptA would thus be 456 AA long, with a coding region 204 nucleotides longer than anticipated and overlapping with the C-terminal region of ppk, the GTG start codon of pptA being located 17 nt upstream of the TGA stop codon of ppk.

2.2. Ppk, pptA and SLI_4382 Are Co-Transcribed But pptA and SLI_4382 Can Also Be Transcribed Alone from Their Own Promoter

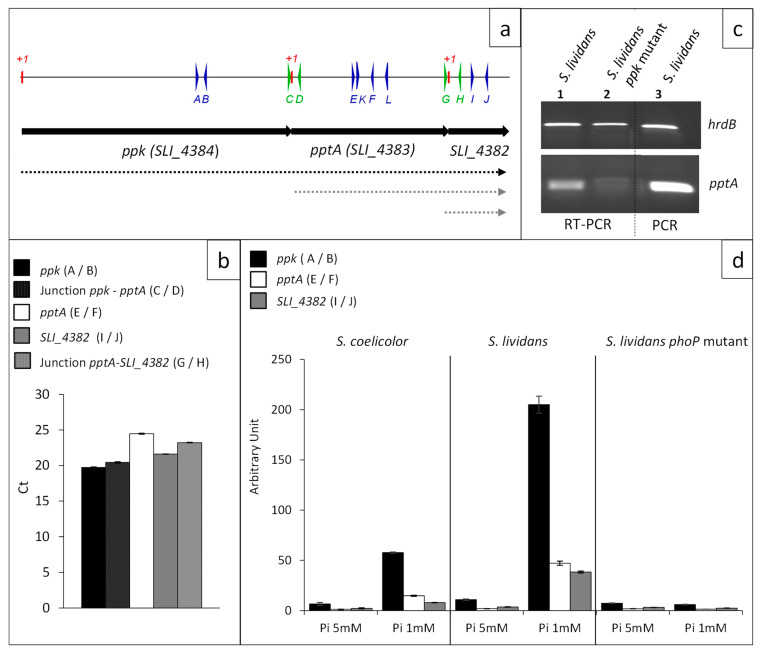

In order to establish the transcriptional situation of the genes ppk, pptA, and SLI_4382 that are located just upstream of the genes encoding the high affinity phosphate transporter (PstSCAB), RNA was prepared from S. lividans grown for 40 h on solid R2YE medium with no phosphate added (1 mM final, Pi limitation) and specific primers, internal to each gene or between two adjacent genes, were designed to assess their transcriptional organization by RT-qPCR (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Transcriptional situation of the contiguous ppk, pptA, and SLI_4382 genes. (a) Schematic representation of the genetic map of the region encompassing genes ppk, pptA, and SLI_4382 represented by black arrows. Primers used to establish the transcriptional situation are represented by thin vertical arrows on a line above the genetic map. Deduced transcriptional situation is represented by dotted lines below the genetic map (b) Level of expression of ppk, pptA, and SLI_4382 and their junctions determined by RT-qPCR with RNA prepared from S. lividans and its phoP mutant grown in conditions of Pi limitation. Position of the primers used is shown in (a) and sequences of the primers are listed in Table S3. The primers are either internal to ppk (A/B, plain black histograms), pptA (E/F, plain white histograms), and SLI_4382 (I/J, plain grey histograms) or encompass the ppk/pptA junction (C/D, dotted black histograms) or the pptA/SLI_4382 junction (I/J, dotted grey histograms). (c) Determination by RT-PCR of the expression of pptA in S. lividans WT (lane 1) and in the ppk mutant of this strain (lane 2) using primers K and L. Control of DNA amplification using the same primers is shown in lane 3 (d) Level of expression of ppk (black histograms), pptA (white histograms), and SLI_4382 (grey histograms) determined by RT-qPCR with RNA prepared from S. coelicolor, S. lividans, and the phoP mutant of S. lividans grown on R2YE in condition of Pi limitation (1 mM) and proficiency (5 mM).

Amplification of fragments, at a similar level, was obtained with primers A and B (internal ppk) and primers C and D (ppk/pptA junction) as well as with primers E and F (internal to pptA) and primers G and H and primers I and J, corresponding to the pptA/SLI_4382 junction and internal to SLI_4382, respectively (Figure 2b). These results demonstrated that these three genes constitute an operon.

The co-transcription of ppk and pptA led to the prediction that the disruption of the ppk gene by a resistance cassette might have a polar effect on pptA expression. In order to test this hypothesis, RNA was prepared from S. lividans and its ppk mutant grown for 40 h on solid R2YE medium with no phosphate added (1 mM final, Pi limitation) and primers K and L were used to detect pptA expression. Results shown in Figure 2c indicated that pptA was still expressed in the ppk mutant but at a much lower level than in the wt strain. In consequence, considering the polar effect of the insertion of the hygromycin cassette in ppk on pptA expression, the antibiotic overproducing phenotype of the ppk mutant might be, at least in part, due to the weak expression of pptA in this strain.

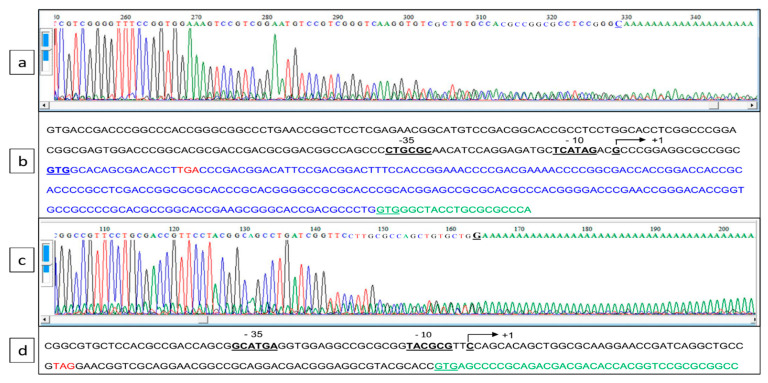

This residual weak transcription of pptA in the ppk mutant suggested that pptA might also be transcribed alone from its own promoter. In order to test this hypothesis, RACE-PCR experiments were conducted to determine whether a transcriptional start point (TSP) could be detected upstream of the coding sequences of SLI_4383/pptA as well as of SLI_4382 (Figure 3a,c). Indeed, a TSP located at a C, 13 nt upstream of the newly proposed GTG start codon of pptA, and thus 30 nt upstream of the Ppk TGA stop codon was identified. This allowed the positioning of putative −10 and −35 sequences of this gene at the end of the ppk coding sequence (Figure 3b). Furthermore, a TSP located at a C, 86 nt upstream of the GTG start codon of SLI_4382, and thus 37 nt upstream of the pptA TAG stop codon was also identified. This allowed the positioning of putative −10 and −35 sequences of this gene at the end of the pptA coding sequence (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

Determination of the transcriptional start point of SLI_4383/pptA and SLI_4382 established by 5′ RACE PCR. (a,c) Chromatograms of 5′ RACE PCR of the pptA and SLI_4382 promoter region, respectively. (b,d) Annotated sequence of the promoter region of pptA and SLI_4382, respectively. The bent arrow represents the transcriptional start site, putative −10 and −35 boxes are underlined, the translational start codons (GTG) are in bold letters and underlined, and the translational stop codon of ppk and SLI_4383 are in red. The erroneously annotated GTG start codon of PptA in the GenBank entry for the S. lividans genome (GG657756.1) is underlined.

2.3. The ppk/pptA/SLI_4382 Operon Belongs to the Pho Regulon

In order to establish the impact of phosphate availability on the transcriptional regulation of the genes of this operon, RNA was prepared from wt S. lividans, its phoP mutant and wt S. coelicolor grown for 40 h on solid R2YE medium with no phosphate added (1 mM final, Pi limitation) or with 4 mM phosphate added (5 mM final, Pi proficiency).

Results of RT-qPCR shown in Figure 2d confirmed that the expression of these genes was induced in condition of phosphate limitation and repressed in condition of phosphate proficiency in the wt strain of S. lividans, whereas the expression of these genes was 20-fold lower in the phoP mutant and at a similar level in both Pi conditions (Figure 2d). This demonstrated that these genes belong to the Pho regulon. The expression of these genes was 4 to 5 fold lower in S. coelicolor than in S. lividans, in condition of Pi limitation (Figure 2d), consistently with the previously reported weak expression of genes of the pho regulon in S. coelicolor [22].

In condition of Pi proficiency, the expression of these genes was low in the three strains and slightly lower in the phoP mutant and in S. coelicolor than in the wt strain of S. lividans (Figure 2d). Interestingly, the expression of the first gene of the operon, ppk, was four-fold higher than that of its downstream genes. This intracistronic polarity is well documented in the literature and some studies suggest that it might be due to the degradation of inefficiently translated RNA [23]. The overlap of the 3′ end of ppk and 5′ end of pptA or of the 3′ end of pptA and 5′ end of SLI_4382, might reduce the translation efficiency of pptA and SLI_4382 making their transcripts more susceptible to degradation.

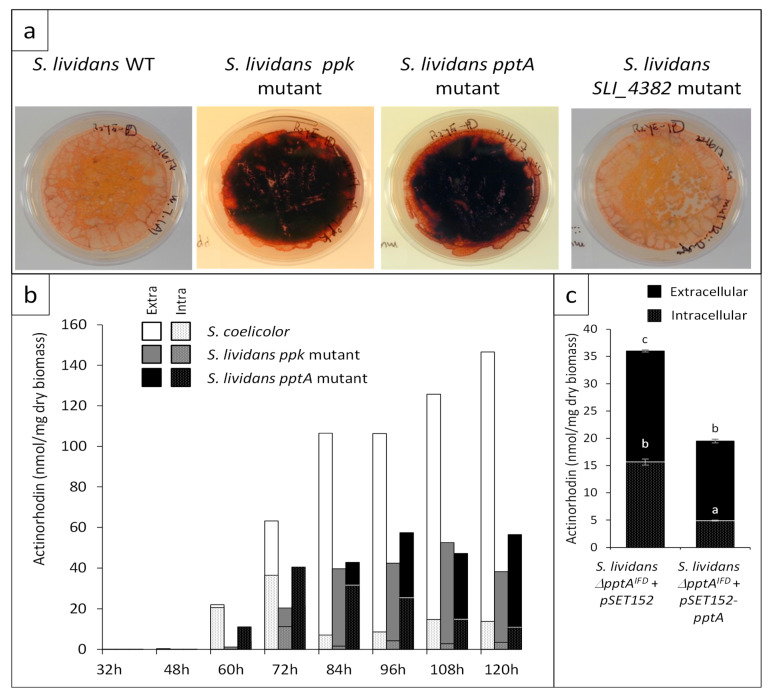

2.4. The Disruption of SLI_4383/pptA Confers an Actinorhodin Over-Producing Phenotype to S. lividans TK24

In order to determine whether the disruption of SLI_4383 had an impact on actinorhodin (ACT) production of S. lividans, pptA was replaced by antibiotic resistance cassette by PCR-targeting. The cassette was then excised as described in Materials and Methods. A similar disruption was carried out for SLI_4382 but the disruption cassette was not excised.

On solid R2YE medium in Pi limitation, the pptA mutant was characterized by an enhanced ACT production, whereas the SLI_4382::att3-aac mutant had a phenotype identical to that of the wt strain (Figure 4a). The assay of ACT production revealed that the pptA mutant strain produced ACT earlier (60 h versus 72 h) and in 1.5- to 2-fold higher amount than the ppk mutant at 72 h. ACT production of the pptA and ppk mutant strains reached their maximum at 96 h and 108 h, respectively, then remained stable or slightly decreased afterwards, whereas ACT production of S. coelicolor kept increasing and was approximately 2.5-fold higher than that of the pptA mutant at late time points (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Antibiotic production of S. lividans TK24 wild type and of the ppk, pptA, and SLI_4382 mutants as well as of the complemented SLI_4383 mutant (a) Pictures of lawns of the strains grown on the surface of a cellophane disk laid onto plates of R2YE solid medium limited in phosphate (1 mM) after 96 h of incubation at 28 °C. (b) Assay of extracellular (plain section) and intracellular (dotted section) actinorhodin production of S. coelicolor (white histograms) and the ppk (grey histograms) and pptA (back histograms) mutants of S. lividans at various time points throughout cultivation. (c) Complementation of the pptA mutant by pSET152-pptA (pMES18). Assay of extracellular (plain black histograms) and intracellular (dotted black histograms) actinorhodin production of the pptA mutant containing pSET152 (control) or pSET152-pptA (pMES18) after 72 h of cultivation.

The in-frame SLI_4383/pptA deletion mutant was complemented by pMES18, an integrative and conjugative plasmid containing the coding sequence of pptA under the control of its own promoter. The integration of the intact pptA gene at the attB site of the chromosome in the apramycin-resistant ex-conjugants was confirmed by PCR. The complementation of this mutant strain led to a reduction of antibiotic production but did not restore a full non-producing phenotype similar to that of the wild type strain (Figure 4c). This might be due to the fact that the expression of pptA from its own promoter is weaker than when it is expressed from the promoter located upstream of ppk.

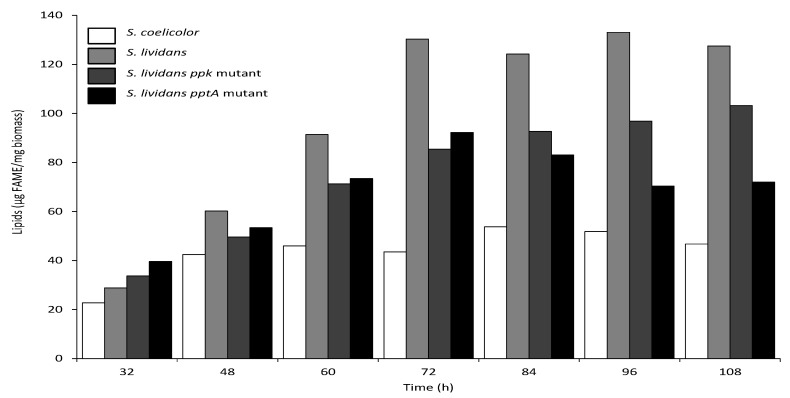

2.5. The Total Lipid Content of the SLI_4383/pptA Deletion Mutant Was Lower Than That of the Wild Type and ppk Mutant Strains of S. lividans

Since we previously demonstrated the existence of a negative correlation between total lipid content and antibiotic production in the ppk mutant of S. lividans and in S. coelicolor [5], we assessed the evolution of the lipid content of the pptA mutant throughout growth. Results shown in Figure 5 confirmed that the total lipid content of the ppk mutant was lower than that of the wt strain throughout the cultivation period but steadily increased with time. In contrast, the total lipid content of the pptA mutant that was at a similar level than that of the ppk mutant up to 72 h and decreased afterwards. As previously reported, the total lipid content of S. coelicolor was low and remained low throughout the cultivation period [5]. The lipid content as well as ACT production levels of the pptA mutant strain, being intermediary those of the ppk mutant and S. coelicolor, we concluded that the phosphate/energetic deficit of the pptA mutant was intermediary between that of the ppk mutant and that of S. coelicolor. These data confirmed the existence of a negative correlation between total lipid content and antibiotic production [5,24].

Figure 5.

FTIRS analysis of total lipid/fatty methyl ester (FAME) content of S. coelicolor (white histograms), S. lividans (light grey histograms), S. lividans ppk mutant (dark grey histograms), and S. lividans SLI_4383/pptA mutant (black histograms) at different points throughout the cultivation period carried out on solid R2YE medium with glucose (50 mM) as the main carbon source and containing 1 mM phosphate (condition of phosphate limitation) at 28 °C.

Interestingly, most of ACT produced by the three strains remained intracellular, up to 72 h but after this point most ACT produced by the ppk mutant and S. coelicolor was extracellular, whereas a large proportion of ACT remained intracellular in the pptA mutant even if this proportion decreased with time. To explain these differences, one can propose that ACT remains intracellular as long as it is needed within the cell to fulfill its putative anti-respiratory and anti-oxidant function [5,25]. In that respect, one cannot exclude than the surprisingly high level of ACT detected in the extracellular medium of S. coelicolor results from altered membrane permeability linked to its altered membrane composition [26] and/or from extensive cell lysis linked to severe phosphate limitation.

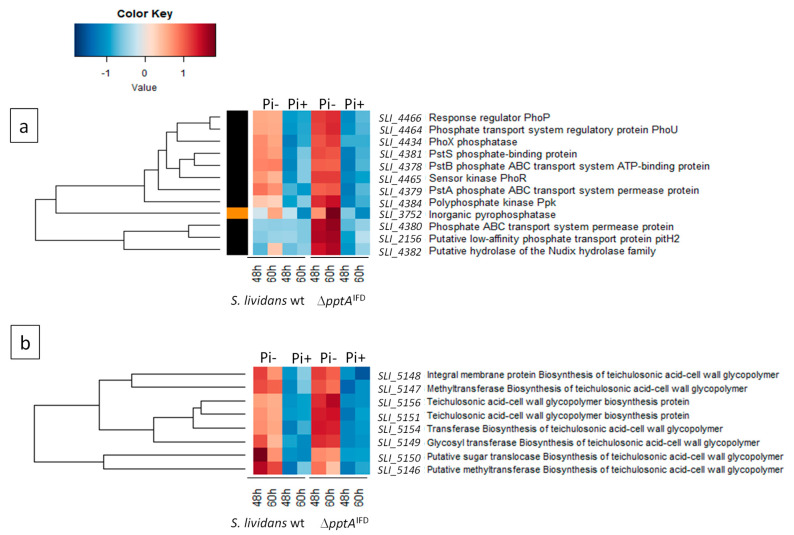

2.6. Proteins of the Pho Regulon Involved in Pi Supply and Saving Are Up-Regulated in the SLI_4383/pptA Mutant

Since antibiotic production usually occurs in condition of low phosphate availability, we carried out a comparative proteomic analysis of the pptA mutant with the wt strain of S. lividans to determine whether the pptA mutant suffers from phosphate stress. The results of this study, shown in Figure 6 a,b, revealed that the expression of the two-component system (TCS) PhoR/PhoP (SLI-4465/SLI-4466) as well as that of the regulatory protein PhoU (SLI_4464) was strongly up-regulated in the SLI_4383 mutant as it was in the ppk mutant [16,17]. This TCS is known to control positively the expression of genes encoding proteins involved in phosphate scavenging, up-take, and saving in condition of Pi limitation [27]. Consistently, proteins belonging to the low affinity ABC phosphate transport system (PstSCAB), SLI_4381 (PstS), SLI_4380 (PstC), SLI_4379 (PtsA), and SLI_4378 (PstB), as well as proteins annotated as phosphatase (SLI_4434) or pyrophosphatase (SLI_3752) were clearly upregulated in the pptA mutant (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

Heatmap representation of proteins of the Pho regulon involved in phosphate scavenging and up-take (a) as well as in the biosynthesis of phosphate free teichulosonic acid biosynthesis in replacement of teichoic acids (b) with significant abundance change (ANOVA, adjusted p value < 0.05) between S. lividans (TK24) and its SLI_4383/pptA deletion mutant. The strains were grown at 28 °C for 48 and 60 h on solid R2YE medium containing glucose (50 mM) as main carbon source and 5 mM (Pi+) or 1 mM (Pi-) phosphate (conditions of phosphate proficiency or limitation, respectively). Protein identifiers are indicated as SLI numbers for both strains and by predicted functions.

Furthermore, proteins encoded by the neighboring genes of pptA, ppk, and SLI_4382 were also upregulated in the mutant. At last, proteins known to be involved in the biosynthesis of phosphate free teichulosonic acid cell-wall glycopolymer (SLI_5146-SLI_5156) in replacement of phosphate containing teichoic acid, in condition of phosphate limitation [28], were also up-regulated in the pptA mutant (Figure 6b). Some of the proteins mentioned above were also up-regulated in the ppk mutant strain [29]. Altogether, these data indicated that the pptA mutant, as the ppk mutant suffers from phosphate limitation that resulted into energetic stress.

2.7. The ppk-pptA-SLI_4382 Region Is Highly Conserved in Streptomyces Species But Not in Other Prokaryotes

Out of 163 fully sequenced Streptomyces genomes from the RefSeq representative genomes database [30] that we analyzed using tblastn [31], we identified only 20 (12.3%) that did not have the ppk-pptA-SLI_4382 gene arrangement found in S. coelicolor. In 7 of these genomes (4.3%), the pptA CHAD-encoding gene was missing and the ppk gene was immediately followed by the SLI_4382 NUDIX hydrolase encoding gene. In the other 13 (8.0%), SLI_4382 was missing but pptA was present downstream of ppk; in 2 of those cases, a likely SLI_4382 orthologue was found elsewhere in the genome, far from ppk. No Streptomyces species were identified that lacked both pptA and SLI_4382, or ppk.

The genetic context of ppk in other prokaryotes was investigated using COGNAT [32], PSAT [33] and MicrobesOnline [34]. These analyses revealed that in the vast majority of genomes, ppk is not followed by a CHAD-encoding gene. Instead, the genes most commonly found downstream of ppk correspond to genes encoding PPX/GppA phosphatases [35], NUDIX hydrolases [36,37], and related enzymes such as MutT [38] and histidine phosphatases [39].

3. Discussion

Antibiotic biosynthesis has long been known to be triggered in condition of phosphate limitation that results in energetic stress and repressed in condition of phosphate proficiency. In consequence, polyphosphates (polyP) as ancient and ubiquitous phosphate polymers, specifically mobilized in condition of phosphate and energetic stress, might be involved in the regulation of antibiotic biosynthesis. We thus investigated the role of proteins encoded by genes of the ppk-pptA-SLI_4382 operon, annotated as possibly involved in polyP metabolism, in the regulation of antibiotic biosynthesis in S. lividans.

This study and previous studies revealed that the expression of the two-component system PhoR/PhoP and of genes under its positive control, involved in Pi supply and saving, was strongly up-regulated in the pptA (Figure 6a,b) and ppk mutants [17]. This indicated that these mutants suffered from phosphate stress/low phosphate availability. The phosin PptA possesses a CHAD domain forming a positively charged tunnel thought to accommodate negatively charged polyP [19,20]. This polyP binding protein is thus most likely involved in the degradation of polyP to supply phosphate intracellularly. The simplest hypothesis would be that PptA acts as an exo-polyphosphatase (PPX-enzyme). However, no similarities nor conserved motifs could be found between PptA and any known exo-polyphosphatases and a purified protein related to SLI_4383/PptA originating from S. chartreusis [20] did not show any exo-polyphosphatase activity in vitro (data not shown). We thus propose that the function of PptA would be to maintain polyphosphates in a suitable conformation for their degradation into phosphate by PPX-like enzymes or by more general phosphatases. PptA would thus constitute an accessory factor for these enzymes. The generation of phosphate from polyphosphate would be totally impaired in the pptA mutant but would remain at a low level in the ppk mutant since pptA is weakly expressed from its own promoter in this strain. The phosphate limitation would thus be more severe in the pptA mutant than in the ppk mutant but far less severe in these two mutant strains than in S. coelicolor. Consistently, the pptA mutant produces ACT earlier and more abundantly than the ppk mutant but less abundantly than S. coelicolor.

The pptA mutant had a lipid content lower than that of the ppk mutant after 72 h but much higher than that of S. coelicolor. Interestingly, after 72 h, the total lipid content of the ppk mutant increased whereas that of the pptA mutant decreased. The reduced total lipid content of these mutant strains was most likely due to their lower phospholipid content due to low phosphate availability [26] as well as to the consumption of acetylCoA to support the activation of the oxidative metabolism of the strains to re-establish their energetic balance, as proposed previously for S. coelicolor [5,40]. The increase of the total lipid/phospholipid content of the ppk mutant after 72 h likely indicates enhanced phosphate availability, likely due to the expression of pptA from its own promoter taking place in this strain but not in the pptA deletion mutant.

Concerning the enhanced antibiotic production of these strains, we have previously reported that the great antibiotic production of S. coelicolor is, at least in part, linked to the weak expression in this strain, of the two-component system PhoR/PhoP that positively controls phosphate supply and saving [22]. In consequence, S. coelicolor is severely limited in phosphate and suffers from energetic stress. We proposed that the sensing of such stress triggers homeostatic processes that contribute to the re-establishment of the energetic balance of the strain [5,25]. One of these processes is a strong reduction of phospholipids biosynthesis in order to save phosphate [26]. Another process is the activation of the oxidative metabolism of the strain (its TCA cycle) that consumes acetylCoA and thus limits lipids biosynthesis and generates reduced co-factors whose re-oxidation by the respiratory chain governs ATP synthesis [5,40]. However, when Pi becomes too scarce, ATP cannot be generated and that is in this context that the production of the benzochromanequinone, Actinorhodin (ACT) is triggered. ACT was proposed to act as an electron acceptor to reduce respiration efficiency and thus ATP generation as well as oxidative stress when phosphate becomes severely limited [5,25]. The earlier and higher ACT production of the pptA mutant compared to the ppk mutant simply indicates that the internal phosphate availability of the pptA mutant is lower than that of the ppk mutant. This study thus unexpectedly revealed that the antibiotic over-producing phenotype and low lipid content of the ppk mutant might be due, at least in part, to the weak expression of pptA in this strain, resulting in a low intracellular phosphate availability.

Most importantly, this study emphasizes the importance of polyphosphate reserves and their degradation for the internal supply of phosphate to repress antibiotic biosynthesis in Streptomyces. The ppk-pptA-SLI_4382 operon is widely conserved in Streptomyces species and deletion of this operon, or more specifically, of genes encoding PptA-like proteins, constitutes a promising strategy to trigger/enhance antibiotic production in Streptomyces species via the reduction of intracellular phosphate availability. The implementation of such simple strategy in various Streptomyces species may allow the discovery of most needed novel antibiotics previously too weakly produced to be characterized.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Conditions

The strains used in this study are listed in Table S1. S. coelicolor M145 and S. lividans TK24 were obtained from the John Innes Institute, Norwich, UK. The E. coli strain DY330 was used for the disruption of genes carried on cosmids [41]. E. coli strains were grown in LB medium for plasmid isolation with 100 μg/mL ampicillin (Amp), 50 μg/mL apramycin (Apr) as final concentrations. YENB or SOB media were used to prepare electro-competent E. coli cells [42]. HT, TSB and YEME media used to routinely grow Streptomyces strains and SFM medium was used to prepare spores [43]. Apramycin (Apr) and thiostrepton (Tsr) were added at a final concentration of 30 μg/mL in HT medium and 50 μg/mL in R2YE medium. Neomycin (Neo) was added in HT medium at a final concentration of 20 μg/mL.

4.2. DNA Manipulations and Transformation of Streptomyces and E. coli Strains

Total genomic DNA extraction and transformation of E. coli and Streptomyces strains were performed according to standard procedures [24]. All the plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S2. DNA fragments were purified from PCR or agarose gels using the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-Up kit (Macherey Nagel, Düren, Germany). Plasmid extraction was carried out using the NucleoSpin plasmid kit (Macherey Nagel, Düren, Germany). A cosmid library of S. coelicolor was obtained from the John Innes Institute (Norwich, UK).

4.3. Construction of KO Mutant Strains and Complementation of the SLI_4383/pptA Mutant Strain

PCR-based REDIRECT technology was used to disrupt pptA and SLI_4382 [44]. The genes were replaced in the cosmid StD84 [45,46] by the att3-aac cassette (originating from pOSV234), yielding pMES/pptA::aac and pMES/SLI_4382::aac. These cosmids were introduced into S. lividans TK24 by transformation of protoplasts. Double recombinants (AprR, NeoS) were detected. The replacement of the genes by the aac cassette was confirmed by Southern blotting and hybridization in comparison with the original strain (data not shown). In order to obtain the in frame deletion mutant of pptA, the att3-aac cassette of pptA::att3-aac mutant was excised in vivo as described previously [47], yielding the ∆pptA IFD mutant.

In order to complement the ∆pptA IFD mutant strain, a 1.5-kpb fragment containing the entire pptA gene with its putative promoter was amplified by PCR using genomic DNA from S. lividans as template and the primers listed in (Table S3) and cloned into pGEM-T Easy resulting in pMES17. The 1.5-kpb EcoRI fragment from pMES17 was ligated into pSET152 digested with EcoRI generating pMES18. Plasmids pSET152 and pMES18 were then introduced into the pptAIFD mutant by conjugal transfer from E. coli S17.1 (Table S1). The integration of each plasmid into the genome was checked by PCR.

4.4. Southern Blot Analysis

First, 4 μg of digested DNA were loaded on each lane, electrophoresed on a 0.7% agarose gel, and transferred to Hybond-N+ (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Membranes were pre-hybridized for 1 h at 65 °C and hybridized for 17 h. The probe used was a 3880-bp fragment containing SLI_4383 and SLI_4382 obtained by PCR on StD84 (Table S3). This probe was labeled with [α-32P] dCTP by using the Megaprime DNA-Labeling system (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). Membranes were then washed thoroughly in 0.2× SSC (1× SSC consists of 0.015 M sodium citrate and 0.15 M NaCl [pH 7.7]) containing 0.1% SDS at 65 °C. Autoradiography was performed by using Fischer scientific films at −80 °C, with intensifying screens STORM, for 1 to 5 h.

4.5. RNA Preparation

RNA was isolated from mycelia of S. coelicolor M145, S. lividans TK24, and of a phoP mutant derived from this strain [17], grown for 40 h at 28 °C on the solid R2YE medium with no KH2PO4 added but containing 1 mM free K2HPO4 from elements of the media (condition of phosphate limitation) or with 4 mM KH2PO4 added (5 mM final, condition of phosphate proficiency). In order to preserve RNA integrity, the mycelium was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen in a solution containing denaturing guanidinium thiocyanate buffer RA1 (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany), phenol-chloroform and ß-mercaptoethanol (a reducing agent). The cells were then lysed and homogenized in the presence of glass beads (diameter <106 µm) using a Fast-Prep apparatus (Savant Instruments, Telangana, India). Total RNA was purified using the Nucleospin RNA kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To remove residual DNA, a DNAse TURBO™ treatment (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was performed at 37 °C for 1 h and total RNA was purified with the Nucleospin RNA Clean-Up kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). The RNA concentrations were quantified using the Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The integrity of the RNAs was verified using the Agilent 2100 bio-analyzer with the eukaryote total RNA 6000 Nano assay (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

4.6. RT-qPCR Experiments

Oligonucleotides used in this study were obtained from Operon and are listed in Table S3. Control PCR amplifications were performed using Taq DNA Polymerase from QIAGEN (Hilden, Germany) or the GC-rich PCR system from Roche (Basel, Switzerland).

Primers used for RT-qPCR experiments were designed using the Primer-Blast tool from NCBI and the Primer Express 3.0 software (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Specificity and the absence of multi-locus matching at the primer site were verified by BLAST analysis. Primers used for RT-PCR analysis are listed in Table S3 and schematic representation of their location is provided in Figure 2. The efficiency of each pair of primers was first checked by PCR on genomic DNA. The amplification efficiencies of primers pairs were determined using the slopes of standard curves obtained by a ten-fold dilution series. Amplification specificity for each real-time PCR reaction was confirmed by analysis of the dissociation curves. Each sample measurement was made in duplicate and four independent RNA biological samples were prepared for each condition. Determined Ct values were then exploited for further analysis. qPCR analysis in the absence of a reverse transcription step was performed on all RNA samples to check the absence of any DNA contamination.

The GenEx software (MultiD, Québec, QC, Canada) was used to select seven reference genes given the more constant level of expression in the various strains under study as well as in Pi limitation and proficiency. The geometric mean of the five most constant genes (glk/SLI_2451, aspS/SLI_4040, gyrA/SLI_4129, gyrB/SLI_4131, rpoB/SLI_4926) was used to normalize the data. hrdB/SLI_6088 and recG/SLI_5845 were excluded but hrdB was used for classical PCR and RT-qPCR control experiment shown in Figure 2c).

1 µg of total RNA was used as the template and reverse transcribed with the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in the presence of RNase inhibitor and random primers following the manufacturer’s instructions, in a final volume of 20 µL. Quantitative PCR was performed on a Quant Studio 12K Flex Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with a SYBR green detection protocol. Next, 3 ng of cDNA were mixed with Fast SYBR Green Master Mix and a concentration of 750 nM of each primer in a final volume of 10 µL. The reaction mixture was loaded on 384 well microplates and submitted to 40 cycles of PCR (95 °C/20 s; [95 °C/1 s; 60 °C/20 s] × 40) followed by a fusion cycle to analyze the melting curve of the PCR products. The ΔΔCt method was used to determine the relative gene expression ratio with three biological replicates. The values of ΔΔCt of S. lividans, its phoP mutant and S. coelicolor were normalized and standardized by log transforming, mean centering and auto-scaling [48,49,50]. All data were subjected to the Student test and the results were presented as the mean of delta-delta-Ct ± standard deviation p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

4.7. 5′. Rapid-Amplification-of-cDNA-Ends (5′ RACE) PCR

The transcriptional start sites of SLI_4383/pptA and SLI_4382 were established by 5′ RACE PCR as described previously [51]. Briefly, 5 µg of total RNA isolated from a 48 h-old culture of S. lividans TK24 was individually used for reverse phase transcriptions with 2 picomoles of specific primers of pptA-GSP1 (Table S3), using Superscript III first-strand synthesis supermix (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After purification with a NucleoSpin Extract IIs column (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany), the synthesized first-strand cDNA was added with a homopolymeric dA tail at the 3′ end using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The poly(dA)-tailed cDNA was again purified, and was then used as a template for the subsequent PCR amplification using a poly(dT) primer (70 homopolymeric T) and a second inner-gene-specific primer, pptA-GSP2 (Table S3). An additional round of PCR was carried out using the original PCR product with a 1000-fold dilution as a template, with the poly(dT) primer and a nested pptA-GSP3 primer (Table S3), to obtain a single specific band. The final PCR products were then sent for sequencing the nested pptA-GSP3 primer (Table S3). The nucleotide immediately preceding the stretch of T residues was recognized as the transcriptional start site.

4.8. Assay of Extracellular and Intracellular Actinorhodin (ACT) Production

The strains S. lividans ppk::Ωhyg, S. lividans pptAIFD deletion mutant, and S. coelicolor M145 were grown for 72 h at 28 °C. Each strain was grown on four individual 9 mm diameter plates (Figure 4b) or on four 5 mm diameter plates (Figure 4c) of solid R2YE medium with no KH2PO4 added but containing 1 mM free K2HPO4 from elements of the media (condition of phosphate limitation). To quantify extracellular ACT, at different points throughout growth, the cellophane of the 9 mm diameter plates was lifted and a agar cylinder of the growth medium was taken aseptically from each of the four replicates using an appropriate device (Figure 4b) or the totality of the agar medium present just under the cellophane disk cellophane of each of the 4 replicates was cut into small pieces (Figure 4c). The 4 agar cylinders together (Figure 4b) or the agar pieces (Figure 4c) were allowed to diffuse in 2 mL of water for 2 h at 4 °C. The first eluate was transferred into a new tube. The operation was repeated twice and 3 mL of HCl (3 M) were added to the 6 mL of final eluate. The mixture was incubated on ice for one night to allow ACT precipitation. To quantify intracellular ACT at different time points throughout growth (Figure 4b) or after 72 h of cultivation (Figure 4c), mycelium present in an area of 1 cm2 of each replicate (Figure 4b) or the totally of the mycelium present under the cellophane disk (Figure 4c), was scraped off, lyophilized, and weighted. Collected mycelium samples were incubated in 1 mL of KOH (1 M) for 30 mn at 4 °C under agitation. After centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred into a new tube and this operation was repeated five times. Two mL of HCl (3 M) were added to the 4 mL of final eluate. The mixture was incubated on ice one night to allow ACT precipitation. After centrifugation at 13,000× g for 30 mn at 4 °C and elimination of the supernatant, the reddish pellet of precipitated ACT was re-suspended in 1 mL KOH (1 M). The optical density of the KOH solutions corresponding to extra- and intra-cellular ACT was determined at 640 nm in a Shimadzu UV-1800 spectrophotometer using KOH (1 M) as blank. The Beer–Lambert law (molar attenuation coefficient of ACT = 25,320) was used to calculate the amount of ACT produced expressed in nano moles per mg of dry biomass [43]. For Figure 4c, the results obtained are presented as the mean ± standard error; a p-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. The letters above the histograms indicate the significance of the differences. When two histograms bear two different letters that means that they are statistically significantly different (p > 0.05; Tukey adjusted comparisons). For Figure 4b, the standard error could not be presented since the 4 agar plugs, as the four mycelial samples, were incubated in the same tube.

4.9. Determination of Total Lipid Content Using Attenuated Total Reflectance-Fourier Transform Infra Red Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIRS) Measurements

In order to determine total lipid content of the strains grown in the same conditions as above (Figure 5), lyophilized mycelial samples were subjected to FTIR spectroscopy using a Bruker Vertex 70 FTIR spectrophotometer with a diamond ATR attachment (PIKE MIRacle crystal plate diamond ZnSe) and a MCT detector with a liquid nitrogen cooling system as described previously [52]. The total lipid content of the strains expressed first in arbitrary units, was converted into μg of fatty methyl esters (FAME) per mg of dry mycelium using the converting equation previously established [53,54].

4.10. Comparative Proteomic Analysis of the Wild Type Strain of S. lividans and of the ∆SLI_4383 Mutant

Total protein extracts of thirty two samples resulting from four biological replicates of S. lividans WT and its SLI_4383 deletion mutant grown on R2YE limited (1 mM) and proficient (5 mM) in phosphate for 48 and 60 h, were alkylated before digestion by Lysyl-Endopeptidase (Wako Chemicals USA) and sequencing-grade-modified trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The resulting proteolytic peptides were pre-cleaned, concentrated under vacuum, and stored before mass spectrometry analysis as described previously [22]. Trypsin-generated peptides were analyzed by nanoLC-MSMS using a nanoElute liquid chromatography system (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) coupled to a timsTOF pro mass spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). Then, 1 µg of protein digest in 2 µL of loading buffer (2% acetonitrile and 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid in water) were loaded on an Aurora analytical column (ION OPTIK, 25 cm × 75 µm, C18, 1.6 µm) and eluted with a gradient of 0–35% of solvent B for 100 min. Solvent A was 0.1% formic acid and 2% acetonitrile in water, and solvent B was 99.9% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. MS and MS/MS spectra were recorded from m/z 100 to 1700 with a mobility scan range from 0.6 to 1.5 V·s/cm2. MS/MS spectra were acquired with the PASEF (parallel accumulation—serial fragmentation (PASEF)) ion mobility-based acquisition mode using a number of PASEF MS/MS scans set as 10. MS and MSMS raw data were processed and converted into mgf files with DataAnalysis software (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA).

Proteins Identifications were performed using the MASCOT search engine (Matrix science, London, UK) against the S. coelicolor and S. lividans protein databases from UniprotKB (15012020). Database searches were performed using trypsin cleavage specificity with two possible miscleavages. Carbamidomethylation of cysteines was set as fixed modification and oxidation of methionines as variable modification. Peptide and fragment tolerances were set at 25 ppm and 0.05 Da, respectively. Proteins were validated when identified with at least two unique peptides. Only ions with a score higher than the identity threshold and a false-positive discovery rate of less than 1% (Mascot decoy option) were considered.

Mass spectrometry based-quantification was performed by label-free quantification using either spectral count (SC) or MS1 ion intensities named XIC (for eXtracted Ion Current). For the first method, total MS/MS spectral count values were extracted from Scaffold software (version Scaffold_4.11.1, Proteome software Inc., Portland, OR, USA), filtered with 95% probability and 1% FDR for protein and peptide thresholds, respectively. For the MS1 ion intensity-based method, MS raw files were analyzed with Maxquant software (v 1.6.10.43) using the maxLFQ algorithm with default settings and enabled 4D feature alignment for a more specific quantitative analysis (match between run function including CCS alignment). Normalization was set as default and identifications with Andromeda were performed using the same search parameters as MASCOT.

Statistical quantitative analyses were based on two different generalized linear models depending on the type of data. The discrete SC (1) and continuous XIC (2) abundances values were modeled respectively as following:

(1) SC = μ + strain + medium + time + replicate + strain x medium + strain x time + medium x time + strain x medium x time + ε ~ Pois(λ);

(2) Log2(XIC) = μ + strain + medium + time + replicate + strain x medium + strain x time + medium x time + strain x medium x time + ε ~ N(0, σ).

Terms represent effect of different conditions and their interactions on protein abundance. Effects were estimated by maximum likelihood and statistical significances were calculated using likelihood ratio test based on the analysis of deviance. p-values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure for multiple testing correction. For each protein, a significant difference in abundance for the 66 combinations of pairwise comparisons was set at 10 for SC and 1 log fold change for XIC. A threshold of 10 significant pairs and an adjusted p-value of 0.05 was used to consider a protein as significantly variable. All the statistical analyses were performed by a homemade R script.

4.11. Computer Analysis of Protein Sequences

Sequence analysis and comparison were performed with various programs including BLAST [55], GeneMark.hmm [56,57], EasyGene [58,59], and AMIGene [60]. The conserved domain database [61] was used to detect known functional domain.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and thank Virginie Redecker, the director of the proteomic platform of I2BC, for her contribution.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6382/10/3/325/s1, Table S1: Bacterial strains used in this study, Table S2: Plasmids used in this study, Table S3: Oligonucleotides used in this study.

Author Contributions

N.S., E.D. and C.M. contributed to all genetic constructs, C.E. and C.L. contributed to ACT assay, A.D.-B. achieved assessment of total lipid content of the strains by FTIRS, D.X. achieved 5′ RACE PCR, E.J. and N.N. achieved RT-qPCR experiments and S.W. carried out comparative genomic analysis. E.D., N.S., A.D.-B., D.X., S.W. and M.-J.V. were involved in management, reporting and interpretation of the data and literature review. M.-J.V. wrote the manuscript and provided financial support for the work. All authors reviewed the manuscript before submission for both grammar and intellectual content. All authors contributed to the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by public Institutions (CNRS and University Paris-Saclay) and by grants originating from the French embassy in Tokyo that covered the salaries of Noriyasu Shikura and from the ANR project Innovantibio (ANR-17-ASTR-0018) that covered the costs of real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) performed by the QPCR/TSA platform of ICSN (https://icsn.cnrs.fr/plateformes/qpcr, accessed on 5 April 2021) CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette as well as the cost of the proteomic analysis carried out on the proteomic platform of I2BC (https://www.i2bc.paris-saclay.fr/spip.php?article201&lang=en, accessed on 5 April 2021).

Data Availability Statement

RT-qPCR data are presented in the paper in Figure 2 and row data (Excell file) can be obtained from the corresponding author on request. Proteomic data are presented in the paper in Figure 6 and row data (Excell file) can be obtained from the corresponding author on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pham J.V., Yilma M.A., Feliz A., Majid M.T., Maffetone N., Walker J.R., Kim E., Cho H.J., Reynolds J.M., Song M.C., et al. A Review of the Microbial Production of Bioactive Natural Products and Biologics. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1404. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barka E.A., Vatsa P., Sanchez L., Gaveau-Vaillant N., Jacquard C., Meier-Kolthoff J.P., Klenk H.P., Clement C., Ouhdouch Y., van Wezel G.P. Taxonomy, Physiology, and Natural Products of Actinobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2015;80:1–43. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00019-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu G., Chater K.F., Chandra G., Niu G., Tan H. Molecular regulation of antibiotic biosynthesis in Streptomyces. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2013;77:112–143. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00054-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin J.F. Phosphate control of the biosynthesis of antibiotics and other secondary metabolites is mediated by the PhoR-PhoP system: An unfinished story. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:5197–5201. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.16.5197-5201.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esnault C., Dulermo T., Smirnov A., Askora A., David M., Deniset-Besseau A., Holland I.B., Virolle M.J. Strong antibiotic production is correlated with highly active oxidative metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor M145. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:200. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00259-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albi T., Serrano A. Inorganic polyphosphate in the microbial world. Emerging roles for a multifaceted biopolymer. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016;32:27. doi: 10.1007/s11274-015-1983-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray M.J. Interactions between DksA and Stress-Responsive Alternative Sigma Factors Control Inorganic Polyphosphate Accumulation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2020;202:e00133-20. doi: 10.1128/JB.00133-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudat A.K., Pokhrel A., Green T.J., Gray M.J. Mutations in Escherichia coli Polyphosphate Kinase That Lead to Dramatically Increased In Vivo Polyphosphate Levels. J. Bacteriol. 2018;200:e00697-17. doi: 10.1128/JB.00697-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crooke E., Akiyama M., Rao N.N., Kornberg A. Genetically altered levels of inorganic polyphosphate in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:6290–6295. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)37370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morohoshi T., Maruo T., Shirai Y., Kato J., Ikeda T., Takiguchi N., Ohtake H., Kuroda A. Accumulation of inorganic polyphosphate in phoU mutants of Escherichia coli and Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:4107–4110. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.8.4107-4110.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray M.J., Jakob U. Oxidative stress protection by polyphosphate—New roles for an old player. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2015;24:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuroda A., Tanaka S., Ikeda T., Kato J., Takiguchi N., Ohtake H. Inorganic polyphosphate kinase is required to stimulate protein degradation and for adaptation to amino acid starvation in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:14264–14269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kulakovskaya T. Inorganic polyphosphates and heavy metal resistance in microorganisms. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018;34:139. doi: 10.1007/s11274-018-2523-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao N.N., Kornberg A. Inorganic polyphosphate regulates responses of Escherichia coli to nutritional stringencies, environmental stresses and survival in the stationary phase. Prog. Mol. Subcell. Biol. 1999;23:183–195. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-58444-2_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chouayekh H., Virolle M.J. The polyphosphate kinase plays a negative role in the control of antibiotic production in Streptomyces lividans. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;43:919–930. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghorbel S., Smirnov A., Chouayekh H., Sperandio B., Esnault C., Kormanec J., Virolle M.J. Regulation of ppk expression and in vivo function of Ppk in Streptomyces lividans TK24. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:6269–6276. doi: 10.1128/JB.00202-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghorbel S., Kormanec J., Artus A., Virolle M.J. Transcriptional studies and regulatory interactions between the phoR-phoP operon and the phoU, mtpA, and ppk genes of Streptomyces lividans TK24. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:677–686. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.677-686.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tumlirsch T., Jendrossek D. Proteins with CHADs (Conserved Histidine alpha-Helical Domains) Are Attached to Polyphosphate Granules In Vivo and Constitute a Novel Family of Polyphosphate-Associated Proteins (Phosins) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017;83:e03399-16. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03399-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorenzo-Orts L., Hohmann U., Zhu J., Hothorn M. Molecular characterization of CHAD domains as inorganic polyphosphate-binding modules. Life Sci. Alliance. 2019;2:e201900385. doi: 10.26508/lsa.201900385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Werten S., Rustmeier N.H., Gemmer M., Virolle M.J., Hinrichs W. Structural and biochemical analysis of a phosin from Streptomyces chartreusis reveals a combined polyphosphate- and metal-binding fold. FEBS Lett. 2019;593:2019–2029. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chater K.F., Chandra G. The use of the rare UUA codon to define “expression space” for genes involved in secondary metabolism, development and environmental adaptation in Streptomyces. J. Microbiol. 2008;46:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s12275-007-0233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millan-Oropeza A., Henry C., Lejeune C., David M., Virolle M.J. Expression of genes of the Pho regulon is altered in Streptomyces coelicolor. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:8492. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-65087-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Smit M.H., Verlaan P.W., van Duin J., Pleij C.W. Intracistronic transcriptional polarity enhances translational repression: A new role for Rho. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;69:1278–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.David M., Lejeune C., Abreu S., Thibessard A., Leblond P., Chaminade P., Virolle M.J. Negative Correlation between Lipid Content and Antibiotic Activity in Streptomyces: General Rule and Exceptions. Antibiotics. 2020;9:280. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9060280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Virolle M.J. A Challenging View: Antibiotics Play a Role in the Regulation of the Energetic Metabolism of the Producing Bacteria. Antibiotics. 2020;9:83. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9020083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lejeune C., Abreu S., Dulermo T., Chaminade P., Werten S., David M., Virolle M.J. Impact of phosphate availability on membrane lipid content of the model strains, Streptomyces lividans and Streptomyces coelicolor. Frontiers. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.623919. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santos-Beneit F., Rodriguez-Garcia A., Franco-Dominguez E., Martin J.F. Phosphate-dependent regulation of the low- and high-affinity transport systems in the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor. Microbiology. 2008;154:2356–2370. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/019539-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ostash B., Shashkov A., Streshinskaya G., Tul’skaya E., Baryshnikova L., Dmitrenok A., Dacyuk Y., Fedorenko V. Identification of Streptomyces coelicolor M145 genomic region involved in biosynthesis of teichulosonic acid-cell wall glycopolymer. Folia Microbiol. 2014;59:355–360. doi: 10.1007/s12223-014-0306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le Marechal P., Decottignies P., Marchand C.H., Degrouard J., Jaillard D., Dulermo T., Froissard M., Smirnov A., Chapuis V., Virolle M.J. Comparative proteomic analysis of Streptomyces lividans Wild-Type and ppk mutant strains reveals the importance of storage lipids for antibiotic biosynthesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79:5907–5917. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02280-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tatusova T., Ciufo S., Fedorov B., O’Neill K., Tolstoy I. RefSeq microbial genomes database: New representation and annotation strategy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D553–D559. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson M., Zaretskaya I., Raytselis Y., Merezhuk Y., McGinnis S., Madden T.L. NCBI BLAST: A better web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W5–W9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klimchuk O.I., Konovalov K.A., Perekhvatov V.V., Skulachev K.V., Dibrova D.V., Mulkidjanian A.Y. COGNAT: A web server for comparative analysis of genomic neighborhoods. Biol. Direct. 2017;12:26. doi: 10.1186/s13062-017-0196-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fong C., Rohmer L., Radey M., Wasnick M., Brittnacher M.J. PSAT: A web tool to compare genomic neighborhoods of multiple prokaryotic genomes. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:170. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dehal P.S., Joachimiak M.P., Price M.N., Bates J.T., Baumohl J.K., Chivian D., Friedland G.D., Huang K.H., Keller K., Novichkov P.S., et al. MicrobesOnline: An integrated portal for comparative and functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D396–D400. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song H., Dharmasena M.N., Wang C., Shaw G.X., Cherry S., Tropea J.E., Jin D.J., Ji X. Structure and activity of PPX/GppA homologs from Escherichia coli and Helicobacter pylori. FEBS J. 2020;287:1865–1885. doi: 10.1111/febs.15120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLennan A.G. The Nudix hydrolase superfamily. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006;63:123–143. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5386-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mildvan A.S., Xia Z., Azurmendi H.F., Saraswat V., Legler P.M., Massiah M.A., Gabelli S.B., Bianchet M.A., Kang L.W., Amzel L.M. Structures and mechanisms of Nudix hydrolases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005;433:129–143. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McLennan A.G. The MutT motif family of nucleotide phosphohydrolases in man and human pathogens (review) Int. J. Mol. Med. 1999;4:79–89. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.4.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rigden D.J. The histidine phosphatase superfamily: Structure and function. Biochem. J. 2008;409:333–348. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Millan-Oropeza A., Henry C., Blein-Nicolas M., Aubert-Frambourg A., Moussa F., Bleton J., Virolle M.J. Quantitative Proteomics Analysis Confirmed Oxidative Metabolism Predominates in Streptomyces coelicolor versus Glycolytic Metabolism in Streptomyces lividans. J. Proteome Res. 2017;16:2597–2613. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu D., Ellis H.M., Lee E.C., Jenkins N.A., Copeland N.G., Court D.L. An efficient recombination system for chromosome engineering in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:5978–5983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100127597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma R.C., Schimke R.T. Preparation of electro competent E. coli using salt-free growth medium. Biotechniques. 1996;20:42–44. doi: 10.2144/96201bm08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kieser T., Bibb M.J., Buttner M.J., Chater K.F., Hopwood D.A. Practical Streptomyces Genetics. John Innes Foundation; Norwich, UK: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gust B., Challis G.L., Fowler K., Kieser T., Chater K.F. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:1541–1546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337542100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bentley S.D., Chater K.F., Cerdeno-Tarraga A.M., Challis G.L., Thomson N.R., James K.D., Harris D.E., Quail M.A., Kieser H., Harper D., et al. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3 (2) Nature. 2002;417:141–147. doi: 10.1038/417141a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Redenbach M., Kieser H.M., Denapaite D., Eichner A., Cullum J., Kinashi H., Hopwood D.A. A set of ordered cosmids and a detailed genetic and physical map for the 8 Mb Streptomyces coelicolor A3 (2) chromosome. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;21:77–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6191336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raynal A., Karray F., Tuphile K., Darbon-Rongere E., Pernodet J.L. Excisable cassettes: New tools for functional analysis of Streptomyces genomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:4839–4844. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00167-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pfaffl M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willems E., Leyns L., Vandesompele J. Standardization of real-time PCR gene expression data from independent biological replicates. Anal. Biochem. 2008;379:127–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu D., Seghezzi N., Esnault C., Virolle M.J. Repression of antibiotic production and sporulation in Streptomyces coelicolor by overexpression of a TetR family transcriptional regulator. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:7741–7753. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00819-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deniset-Besseau A., Prater C.B., Virolle M.J., Dazzi A. Monitoring TriAcylGlycerols Accumulation by Atomic Force Microscopy Based Infrared Spectroscopy in Streptomyces Species for Biodiesel Applications. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014;5:654–658. doi: 10.1021/jz402393a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Millan-Oropeza A., Rebois R., David M., Moussa F., Dazzi A., Bleton J., Virolle M.J., Deniset-Besseau A. Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR FT-IR) for Rapid Determination of Microbial Cell Lipid Content: Correlation with Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Appl. Spectrosc. 2017;71:2344–2352. doi: 10.1177/0003702817709459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vitry P., Bourillot E., Tetard L., Plassard C., Lacroute Y., Lesniewska E. Mode-synthesizing atomic force microscopy for volume characterization of mixed metal nanoparticles. J. Microsc. 2016;263:307–311. doi: 10.1111/jmi.12398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schaffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lukashin A.V., Borodovsky M. GeneMark.hmm: New solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1107–1115. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.4.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Besemer J., Lomsadze A., Borodovsky M. GeneMarkS: A self-training method for prediction of gene starts in microbial genomes. Implications for finding sequence motifs in regulatory regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2607–2618. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.12.2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nielsen P., Krogh A. Large-scale prokaryotic gene prediction and comparison to genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:4322–4329. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Larsen T.S., Krogh A. EasyGene—A prokaryotic gene finder that ranks ORFs by statistical significance. BMC Bioinform. 2003;4:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bocs S., Cruveiller S., Vallenet D., Nuel G., Medigue C. AMIGene: Annotation of MIcrobial Genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3723–3726. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marchler-Bauer A., Anderson J.B., Cherukuri P.F., DeWeese-Scott C., Geer L.Y., Gwadz M., He S., Hurwitz D.I., Jackson J.D., Ke Z., et al. CDD: A Conserved Domain Database for protein classification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D192–D196. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

RT-qPCR data are presented in the paper in Figure 2 and row data (Excell file) can be obtained from the corresponding author on request. Proteomic data are presented in the paper in Figure 6 and row data (Excell file) can be obtained from the corresponding author on request.