Abstract

Background

One of the drugs which is commonly used in diabetic patients is Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor. Currently, the association between DPP-4 inhibitor and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outcome is not yet established. This study aims to analyze the potential association between DPP-4 inhibitor and the composite poor outcome of COVID-19.

Methods

We systematically searched the PubMed and Europe PMC database using specific keywords related to our aims until November 29th, 2020. All articles published on COVID-19 and DPP-4 inhibitor were retrieved. Statistical analysis was done using Review Manager 5.4 and Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3 software.

Results

Our pooled analysis showed that DPP-4 inhibitor use was not associated with composite poor outcomes of COVID-19 [OR 1.09 (95% CI 0.93–1.28), p = 0.29, I2 = 0%, random-effect modelling], and its subgroup which comprised of severe COVID-19 [OR 1.07 (95% CI 0.87–1.31), p = 0.54, I2 = 0%, random-effect modelling], and mortality [OR 1.14 (95% CI 0.87–1.51), p = 0.35, I2 = 8%, random-effect modelling]. Meta-regression showed that the association was not influenced by age (p = 0.663), hypertension (p = 0.454), and admission blood glucose (p = 0.310). Subgroup analysis showed that the association was weaker in East Asian populations (OR 1.02) compared to European populations (OR 1.11).

Conclusion

DPP-4 inhibitor in diabetic patients did not alter the outcomes from COVID-19. Our study suggest that the use of DPP-4 inhibitor in COVID-19 patients with diabetes may still be continued according to the patients’ need.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40200-021-00777-4.

Keywords: Diabetes, Medications, DPP-4, Coronavirus, COVID-19

Introduction

Eight months have passed since coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was declared as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO), but the number of positive cases and death cases is still increasing. This global pandemic disease has caused a significant impact on the economic and health aspects around the world. The manifestation of this disease can be varied from asymptomatic or consist of mild symptoms such as cough and fever to severe and life-threatening acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sepsis, multi-organ failure, and death [1, 2]. There are several comorbid conditions which are associated with the development of severe outcome and mortality from COVID-19, including diabetes [3–8]. Patients with diabetes have a higher risk of severe COVID-19 because of the increased expression of angiotensin II converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) and Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 (DPP-4) mediating infection [9]. Moreover, patients with diabetes are thought to have elevated pro-inflammatory cytokine levels such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [10]. Several efforts have been made to minimize the risk of progression into severe COVID-19 and mortality in patients with diabetes based on the beforementioned pathophysiology. The previous meta-analysis has shown that metformin administration is associated with a reduction of mortality rate from COVID-19 because of its ability to decrease binding between ACE2 receptor and SARS-CoV-2 Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) through AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-mediated phosphorylation of ACE2 [11]. Not only that, metformin can inhibit the inflammatory response that could potentially contribute to mortality through a mechanism such as a cytokine storm and vascular damage [11]. Besides metformin, one of the drugs which are commonly used by patients with diabetes is the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor. This drug has been proposed to help in reducing the severity and mortality from COVID-19 because of its ability to modulate the DPP4/CD26 activity and block the host CD26 receptor, thus disabling SARS–CoV-2 way to enter T cells [12]. DPP-4 inhibitor is also believed to have an effect on the reduction of cytokines overproduction, downregulation of macrophages activity/function, and enhancement of Glucagon Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) anti-inflammatory activity, therefore can improve the poor outcomes from COVID-19 [9, 12]. However, these arguments are not supported by enough evidence on COVID-19 patients. Several observational studies still showed conflicting results. This study aims to analyze the association between DPP-4 inhibitor use and composite poor outcomes from COVID-19 in patients with diabetes mellitus to give better evidence regarding its efficacy and safety in COVID-19 patients.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and study selection

A systematic search of the literature was conducted on PubMed and Europe PMC using the keywords “DPP-4” OR “dipeptidyl peptidase 4” OR “medications” AND “diabetes” OR “diabetes mellitus” AND “coronavirus disease 2019” OR “COVID-19”, until the present time (November 29th, 2020) with language restricted to English only. We assessed the title, abstract, and full text of all articles identified that matched the search criteria, and those reporting the rate of DPP-4 inhibitor in COVID-19 patients with a clinically validated definition of “severe disease” and “mortality” were included in this meta-analysis. The references of all identified studies were also analyzed (forward and backward citation tracking) to identify other potentially eligible articles. The study was carried out per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [13].

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included in this review if met the following inclusion criteria: representation for clinical questions (P: patients with diabetes who have positive/confirmed cases of COVID-19; I: a group of patients with DPP-4 inhibitor as their medication; C: a group of patients without DPP-4 inhibitor usage; O: severe COVID-19 and mortality, type of study was a randomized control trial, cohort, clinical trial, case-cohort, and cross-over design, and if the full-text article was available. The following types of articles were excluded: articles other than original research (e.g., review articles, letters, or commentaries); case reports; articles not in the English language; articles on research in pediatric populations (17 years of age or younger); and articles on research in pregnant women.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction was performed independently by two authors, we used standardized forms that include author, year, study design, number of participants, age, gender, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, DPP-4 inhibitor, admission blood glucose levels, severe COVID-19, and mortality.

The outcome of interest was the composite poor outcome which comprised of severe COVID-19 and mortality. Severe COVID-19 was defined as patients who had any of the following features at the time of, or after, admission: (1) respiratory distress (≥30 breaths per min); (2) oxygen saturation at rest ≤93%; (3) ratio of the partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) to a fractional concentration of oxygen inspired air (fiO2) ≤300 mmHg; or (4) critical complication (respiratory failure, septic shock, and or multiple organ dysfunction/failure) or admission into ICU. Mortality outcome was defined as the number of patients who died because of COVID-19.

Two investigators independently evaluated the quality of the included cohort and case-control studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) [14]. The selection, comparability, and exposure of each study were broadly assessed and studies were assigned a score from zero to nine. Studies with scores ≥7 were considered of good quality.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager 5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration) and Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3 software were used to perform the meta-analysis. We used the Generic Inverse Variance formula with random-effects models to calculate each outcome’s risk. The heterogeneity was assessed by using the I2 statistic with a value of <25%, 26–50%, and > 50% were considered as low, moderate, and high degrees of heterogeneity, respectively. The effect estimate was reported as odds ratio (OR) along with its 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous variables, respectively. P value was two-tailed, and the statistical significance was set at ≤0.05. Random effects meta-regression was performed using a restricted-maximum likelihood for pre-specified variables including age, gender, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and admission blood glucose levels. Subgroup analysis was done to compare the outcomes in European populations and East Asian populations. We performed Begg’s funnel-plot analysis and Egger’s weighted regression method [15] to assess the risk of publication bias (p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant).

Results

Study selection and characteristics

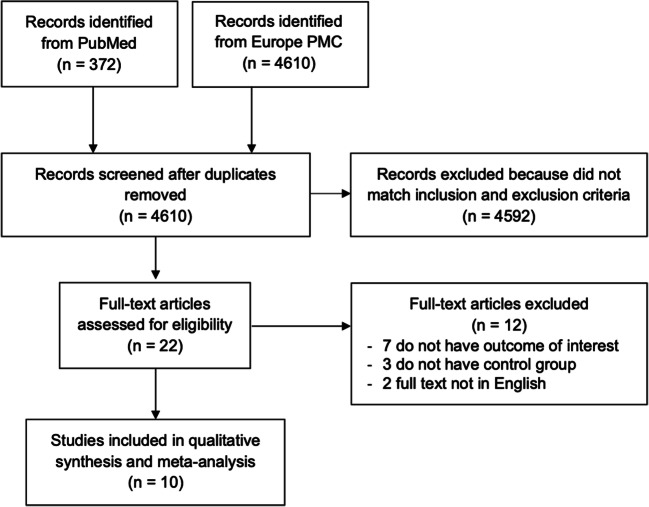

A total of 4982 records were obtained through systematic electronic searches. After the removal of duplicates, 4610 records remained. A total of 4592 records were excluded after screening the titles/abstracts because they did not match our inclusion and exclusion criteria. After evaluating 22 full-texts for eligibility, 7 full-text articles were excluded because they do not have the outcome of interest (severe COVID-19 or mortality), 3 full-text articles were excluded because they do not have the control/comparison group, 2 articles were excluded because the full text not in English, and finally, 10 studies [16–25] with a total of 7012 COVID-19 patients with diabetes were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Of a total of 10 included studies, all were retrospective cohort. The essential characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Sample size | Design | Overall age mean ± SD | Male n (%) | Hypertension n (%) | Cardiovascular diseasen (%) | DPP4 inhibitor n (%) | Admission blood glucose mg/dL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cariou B et al. [16] 2020 (France) | 1317 | Retrospective cohort | 69.8 ± 13 | 855 (64.9%) | 1003 (76.1%) | 336 (25.5%) | 285 (21.6%) | 171.8 ± 77.6 |

| Chen Y et al. [17] 2020 (China) | 120 | Retrospective cohort | 66.6 ± 9.6 | 64 (53.3%) | 84 (70%) | 29 (24.1%) | 20 (16.6%) | 165.7 ± 103.7 |

| Fadini GP et al. [18] 2020 (Italy) | 85 | Retrospective cohort | 70.3 ± 13.3 | 55 (64.7%) | 59 (69.4%) | 23 (27.1%) | 9 (10.5%) | 228.8 ± 109.9 |

| Izzi-Engbeaya C et al. [19] 2020 (England) | 889 | Retrospective cohort | 65.8 ± 17.5 | 534 (60%) | 418 (47%) | 231 (25.9%) | 93 (10.4%) | 180.9 ± 99.8 |

| Kim MK et al. [20] 2020 (South Korea) | 235 | Retrospective cohort | 68.3 ± 11.9 | 106 (45.1%) | 147 (62.6%) | 27 (11.5%) | 85 (36.2%) | 186.7 ± 101.1 |

| Perez-Belmonte LM et al. [21] 2020 (Spain) | 2666 | Retrospective cohort | 74.9 ± 8.4 | 1647 (61.9%) | 2026 (76.2%) | 1499 (56.2%) | 791 (30.2%) | 153 ± 45.7 |

| Rhee SY et al. [22] 2020 (South Korea) | 832 | Retrospective cohort | 63.6 ± 12.1 | 445 (53.4%) | 568 (68.2%) | 227 (27.2%) | 263 (31.6%) | N/A |

| Sourij H et al. [23] 2020 (Austria) | 238 | Retrospective cohort | 71.1 ± 12.9 | 152 (63.9%) | 169 (71%) | 63 (26.5%) | 42 (17.7%) | 127 ± 61.4 |

| Yan H et al. [24] 2020 (China) | 578 | Retrospective cohort | 49.1 ± 14.1 | 293 (50.7%) | 130 (22.4%) | 15 (2.6%) | 6 (1%) | N/A |

| Zhang N et al. [25] 2020 (China) | 52 | Retrospective cohort | 66.4 ± 8.7 | 33 (63.5%) | 34 (65.4%) | 14 (26.9%) | 4 (7.7%) | 166.3 ± 56 |

Quality of study assessment

Studies with various study designs including cohort and case-control were included in this review and assessed accordingly with the appropriate scale or tool. Newcastle Ottawa Scales (NOS) were used to assess the cohort and case-control studies (Table 2). All included studies were rated ‘good’. In conclusion, all studies were seemed fit to be included in the meta-analysis.

Table 2.

Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment of observational studies

| First author, year | Study design | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total score | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cariou B et al. [16] 2020 | Cohort | **** | ** | *** | 9 | Good |

| Chen Y et al. [17] 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Fadini GP et al. [18] 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Izzi-Engbeaya C et al. [19] 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Kim MK et al. [20] 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | **** | 9 | Good |

| Perez-Belmonte LM et al. [21] 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Rhee SY et al. [22] 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Sourij H et al. [23] 2020 | Cohort | **** | ** | *** | 9 | Good |

| Yan H et al. [24] 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | **** | 9 | Good |

| Zhang N et al. [25] 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

DPP-4 inhibitor and outcome

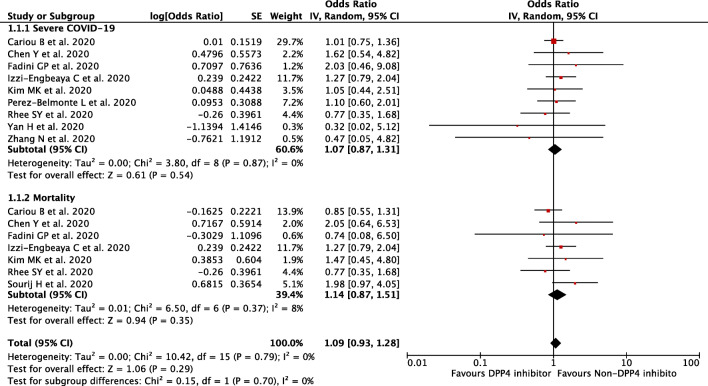

Our pooled analysis showed that DPP-4 inhibitor use was not associated with composite poor outcomes of COVID-19, with no relevant heterogeneity [OR 1.09 (95% CI 0.93–1.28), p = 0.29, I2 = 0%, random-effect modelling] (Fig. 2). Subgroup analysis showed that DPP-4 inhibitor did not alter the severity of COVID-19 [OR 1.07 (95% CI 0.87–1.31), p = 0.54, I2 = 0%, random-effect modelling], nor mortality from COVID-19 [OR 1.14 (95% CI 0.87–1.51), p = 0.35, I2 = 8%, random-effect modelling].

Fig. 2.

Forest plot that demonstrates the association of the DPP-4 inhibitor with composite poor outcome and its subgroup which comprised of severe COVID-19 and mortality

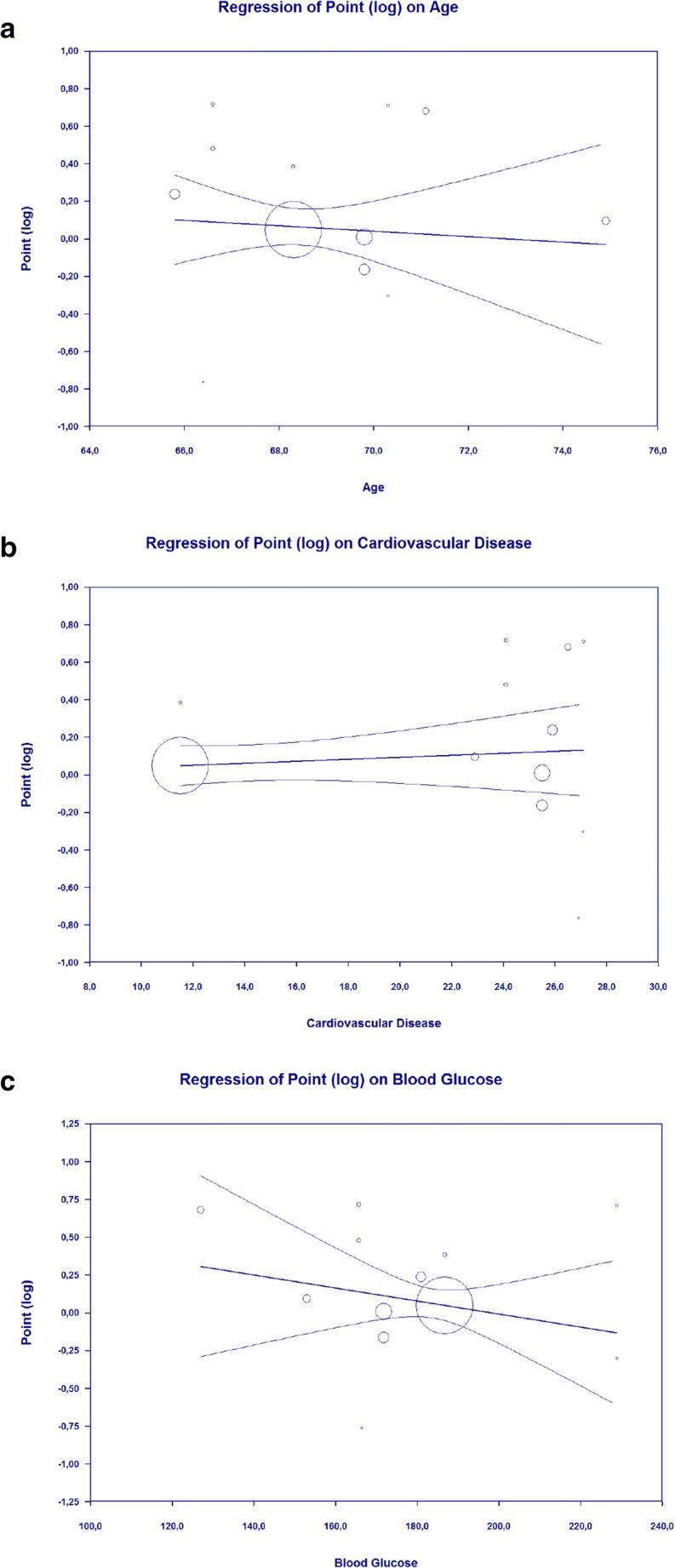

Meta-regression

Meta-regression showed that the association between DPP-4 inhibitor and composite poor outcome of COVID-19 was not affected by age (p = 0.663) (Fig. 3a), gender (p = 0.679), hypertension (p = 0.538), cardiovascular disease (p = 0.454) (Fig. 3b), and admission blood glucose levels (p = 0.310) (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Bubble-plot for Meta-regression. Meta-regression analysis showed that the association between DPP-4 inhibitor and composite poor outcome was not affected by age (a), cardiovascular disease (b), and admission blood glucose levels (c)

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis for studies from European populations [OR 1.11 (95% CI 0.93–1.33), p = 0.26, I2 = 0%, random-effect modelling] showed a higher OR for composite poor outcomes of COVID-19 compared to East Asian populations [OR 1.02 (95% CI 0.70–1.47), p = 0.93, I2 = 0%, random-effect modelling].

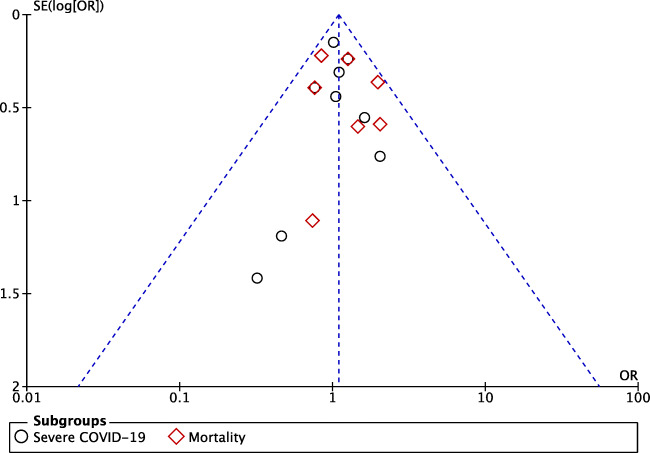

Publication Bias

The funnel-plot analysis showed a qualitatively symmetrical inverted funnel-plot (Fig. 4) and regression-based Egger’s test were not statistically significant (p = 0.759) for the association between DPP-4 inhibitor and composite poor outcome of COVID-19, showing no indication of publication bias.

Fig. 4.

Begg’s funnel-plot analysis showed a qualitatively symmetrical inverted funnel-plot for the association of DPP-4 inhibitor with composite poor outcome of COVID-19

Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis which not only analyzes the association between DPP-4 inhibitor and composite poor outcome of COVID-19, but also elaborate the effect of the confounding factors such as age, gender, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and admission blood glucose which may influence the association between DPP-4 inhibitor and composite poor outcome of COVID-19. This comprehensive meta-analysis of 10 studies showed that DPP-4 inhibitor was not associated with composite poor outcome of COVID-19, therefore it cannot alter the severity of COVID-19 and mortality from COVID-19. This association was not influenced by age, gender, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and admission blood glucose. From the subgroup analysis, it is also revealed that the magnitude of risk linked to DPP-4 inhibitor as single factor was greater in studies with European populations compared with Asian populations. This was probably caused by the Neanderthal core haplotype which presents higher in the European populations (France, Italy, England, Austria) at an allele frequency of 8%, while in East Asia populations (China, South Korea) the Neanderthal risk haplotype are almost absent [26]. The Neanderthal core haplotype is found to be the major genetic risk factor for severe COVID-19 [26].

Several reasons can be proposed to explain why DPP-4 inhibitor use cannot alter the severity nor mortality outcome of COVID-19. First, although a recent publication demonstrated that the S1 domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein might interact with membrane-bound human DPP-4 [27], but functional assays study has suggested that ACE2 to be the major binding partner for COVID-19 and DPP-4 did not play a significant role for SARS-CoV-2 internalization into host cells [28]. Therefore, administration of DPP-4 inhibitor cannot make a significant change into the course of COVID-19. Second, a recently published experimental study showed that the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-5, IL-6, CXCL1, IL-1β, and IL-4 were not different in a calorie deficit (CD) vs. high fat, fructose, and cholesterol (HFFC) diet after 14-days administration of DPP-4 inhibitor, despite the simultaneous reduction of DPP-4 activity and induction of DPP-4 protein levels [29]. These findings suggest that the levels of DPP-4 activity and soluble DPP-4 (sDPP-4) were not associated with cytokine levels in plasma, liver, or adipose tissue of high-fat diet-fed mice treated with DPP-4 inhibitor and further questions the anti-inflammatory effect of DPP-4 inhibitors. Moreover, the same study also analyzed the DPP4 activity, sDPP4 protein, and levels of inflammatory markers in plasma samples from 600 subjects with type 2 diabetes (T2D) treated with or without sitagliptin for 12 months from The Trial Evaluating Cardiovascular Outcomes with Sitagliptin (TECOS) trial [29, 30]. This study showed no differences, relative to baseline values, in the sDPP4 protein levels and in circulating levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and CRP, which were the marker of severe COVID-19, at 12 months in the subjects receiving sitagliptin [29, 31]. Administration of DPP-4 inhibitor in patients with diabetes who have COVID-19 cannot reduce the inflammation and prevent the cytokine storm, thus cannot alter the severity and mortality outcome from COVID-19.

Despite DPP-4 inhibitor has no significant advantage for improving the composite poor outcomes of COVID-19, due to its important role in the control of diabetes, it should be prescribed according to patients’ need. Physicians may still be using these drugs for type 2 diabetes patients who already received a benefit from using this drug or may also opt to change into metformin which has beneficial effects in reducing the mortality rate from COVID-19. Finally, anti-diabetes medications, including DPP-4 inhibitor shall be regarded as an important factor in future risk stratification models for COVID-19 in patients with diabetes.

This study has several limitations. First, data on the duration of DPP-4 inhibitor usage and the compliance to medications were lacking in the included studies, hence, cannot be analyzed. Second, we include some pre-print studies to minimize the risk of publication bias, however, the authors have made exhaustive efforts to ensure that only sound studies were included and we expect that most of those studies currently available in pre-print form will eventually be published and that we will identify them through ongoing electronic literature surveillances. We hope that this study can still give early insight into further risk stratification for COVID-19.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 26 kb)

Acknowledgments

Availability of data and materials

All the data generated and analysed during this review have been provided in article and in supplementary files.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

Timotius Ivan Hariyanto: Conceptualization; Data curation; Methodology; Investigation; Validation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing. Andree Kurniawan: Conceptualization; Validation; Resources; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing; Supervision. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Declarations

Declaration of competing interest

None

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hariyanto TI, Rizki NA, Kurniawan A. Anosmia/Hyposmia is a good predictor of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection: a meta-analysis. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;25(1):e170–e174. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1719120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hariyanto TI, Kristine E, Jillian Hardi C, Kurniawan A. Efficacy of Lopinavir/ritonavir compared with standard Care for Treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2020;20. 10.2174/1871526520666201029125725. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Hariyanto TI, Putri C, Frinka P, Louisa J, Lugito NPH, Kurniawan A. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and outcomes from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2021. 10.1089/AID.2020.0307. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hariyanto TI, Kurniawan A. Anemia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Transfus Apher Sci. 2020;102926:102926. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2020.102926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hariyanto TI, Kurniawan A. Dyslipidemia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(5):1463–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.07.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hariyanto TI, Prasetya IB, Kurniawan A. Proton pump inhibitor use is associated with increased risk of severity and mortality from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52(12):1410–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hariyanto TI, Putri C, Situmeang RFV, Kurniawan A. Dementia is a predictor for mortality outcome from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;26:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s00406-020-01205-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hariyanto TI, Putri C, Arisa J, Situmeang RFV, Kurniawan A. Dementia and outcomes from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;93:104299. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valencia I, Peiró C, Lorenzo Ó, Sánchez-Ferrer CF, Eckel J, Romacho T. DPP4 and ACE2 in diabetes and COVID-19: therapeutic targets for cardiovascular complications? Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1161. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang I, Lim MA, Pranata R. Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia - a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(4):395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hariyanto TI, Kurniawan A. Metformin use is associated with reduced mortality rate from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Obes Med. 2020;19:100290. doi: 10.1016/j.obmed.2020.100290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solerte SB, Di Sabatino A, Galli M, Fiorina P. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) inhibition in COVID-19. Acta Diabetol. 2020;57(7):779–783. doi: 10.1007/s00592-020-01539-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Margulis AV, Pladevall M, Riera-Guardia N, Varas-Lorenzo C, Hazell L, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Perez-Gutthann S. Quality assessment of observational studies in a drug-safety systematic review, comparison of two tools: the Newcastle-Ottawa scale and the RTI item bank. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:359–368. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S66677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cariou B, Hadjadj S, Wargny M, Pichelin M, Al-Salameh A, Allix I, et al. Phenotypic characteristics and prognosis of inpatients with COVID-19 and diabetes: the CORONADO study. Diabetologia. 2020;63(8):1500–1515. doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05180-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y, Yang D, Cheng B, Chen J, Peng A, Yang C, Liu C, Xiong M, Deng A, Zhang Y, Zheng L, Huang K. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with diabetes and COVID-19 in association with glucose-lowering medication. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(7):1399–1407. doi: 10.2337/dc20-0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fadini GP, Morieri ML, Longato E, Bonora BM, Pinelli S, Selmin E, et al. Exposure to dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 inhibitors and COVID-19 among people with type 2 diabetes: A case-control study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020. 10.1111/dom.14097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Izzi-Engbeaya C, Distaso W, Amin A, Yang W, Idowu O, Kenkre JS, et al. Severe COVID-19 and Diabetes: A Retrospective Cohort Study from Three London Teaching Hospitals. medRxiv. 2020. 10.1101/2020.08.07.20160275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Kim MK, Jeon JH, Kim SW, Moon JS, Cho NH, Han E, You JH, Lee JY, Hyun M, Park JS, Kwon YS, Choi YK, Kwon KT, Lee SY, Jeon EJ, Kim JW, Hong HL, Kwon HH, Jung CY, Lee YY, Ha E, Chung SM, Hur J, Ahn JH, Kim NY, Kim SW, Chang HH, Lee YH, Lee J, Park KG, Kim HA, Lee JH. The clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with moderate-to-severe coronavirus disease 2019 infection and diabetes in Daegu, South Korea. Diabetes Metab J. 2020;44(4):602–613. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2020.0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pérez-Belmonte LM, Torres-Peña JD, López-Carmona MD, Ayala-Gutiérrez MM, Fuentes-Jiménez F, Huerta LJ, et al. Mortality and other adverse outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus admitted for COVID-19 in association with glucose-lowering drugs: a nationwide cohort study. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):359. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01832-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhee SY, Lee J, Nam H, Kyoung DS, Kim DJ. Effects of a DPP-4 inhibitor and RAS blockade on clinical outcomes of patients with diabetes and COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020. 10.1101/2020.05.20.20108555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Sourij H, Aziz F, Bräuer A, Ciardi C, Clodi M, Fasching P, Karolyi M, Kautzky-Willer A, Klammer C, Malle O, Oulhaj A, Pawelka E, Peric S, Ress C, Sourij C, Stechemesser L, Stingl H, Stulnig T, Tripolt N, Wagner M, Wolf P, Zitterl A, Kaser S, for the COVID‐19 in diabetes in Austria study group Covid-19 fatality prediction in people with diabetes and prediabetes using a simple score at hospital admission. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;23:589–598. doi: 10.1111/dom.14256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan H, Valdes AM, Vijay A, Wang S, Liang L, Yang S, Wang H, Tan X, du J, Jin S, Huang K, Jiang F, Zhang S, Zheng N, Hu Y, Cai T, Aithal GP. Role of drugs used for chronic disease management on susceptibility and severity of COVID-19: a large case-control study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;108(6):1185–1194. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang N, Wang C, Zhu F, Mao H, Bai P, Chen LL, et al. Risk Factors for Poor Outcomes of Diabetes Patients With COVID-19: A Single-Center, Retrospective Study in Early Outbreak in China. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020;11:571037. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.571037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeberg H, Pääbo S. The major genetic risk factor for severe COVID-19 is inherited from Neanderthals. Nature. 2020;587(7835):610–612. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2818-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vankadari N, Wilce JA. Emerging WuHan (COVID-19) coronavirus: glycan shield and structure prediction of spike glycoprotein and its interaction with human CD26. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):601–604. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1739565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baggio LL, Varin EM, Koehler JA, Cao X, Lokhnygina Y, Stevens SR, Holman RR, Drucker DJ. Plasma levels of DPP4 activity and sDPP4 are dissociated from inflammation in mice and humans. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3766. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17556-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green JB, Bethel MA, Armstrong PW, Buse JB, Engel SS, Garg J, Josse R, Kaufman KD, Koglin J, Korn S, Lachin JM, McGuire DK, Pencina MJ, Standl E, Stein PP, Suryawanshi S, van de Werf F, Peterson ED, Holman RR. Effect of Sitagliptin on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(3):232–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hariyanto TI, Japar KV, Kwenandar F, Damay V, Siregar JI, Lugito NPH, Tjiang MM, Kurniawan A. Inflammatory and hematologic markers as predictors of severe outcomes in COVID-19 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;41:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.12.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 26 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated and analysed during this review have been provided in article and in supplementary files.