ABSTRACT

The NHS is currently in the midst of a global health crisis that requires rapid action from its staff and systems. The Royal College of Physicians’ chief registrars, in their role as middle leaders that bridge the gap between junior doctors and senior leadership in NHS trusts nationwide, are uniquely positioned to respond to the COVID-19 crisis. Our strategies fall into three overlapping categories: our roles as middle leaders, developing effective communication techniques and promoting staff wellbeing. We discuss lessons of good leadership in a time of crisis, from embracing new ways of working and new technologies, to utilising professional networks to drive change, to providing tools to support the wellbeing of the colleagues we both lead and care for. The lessons of our initial response are being shared across our national network. We also hope that the novel approaches we have developed will inform the practice of future middle leaders.

KEYWORDS: Leadership, middle leader, communication, wellbeing, COVID-19

Introduction

Global pandemics test our humanity, stretch resources and challenge beliefs in the current systems. They require a rapid response from clinicians and health service leaders. Here we explore how the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) chief registrars have been able to take an early lead in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic within the NHS.

In September 2019, 72 middle-grade doctors embarked on a leadership journey as the 2019–2020 cohort of RCP chief registrars. Like our predecessors, our mission was to be the bridge between junior doctors and senior management, to implement transformational quality improvement and to promote safety and wellbeing within our organisations.1 We started by building relationships, developing communication and negotiating skills, growing our professional networks, and discovering our preferred leadership styles. By February 2020 we had settled in, we were embedded in our trusts’ leadership networks and our improvement projects were underway. Then everything changed.

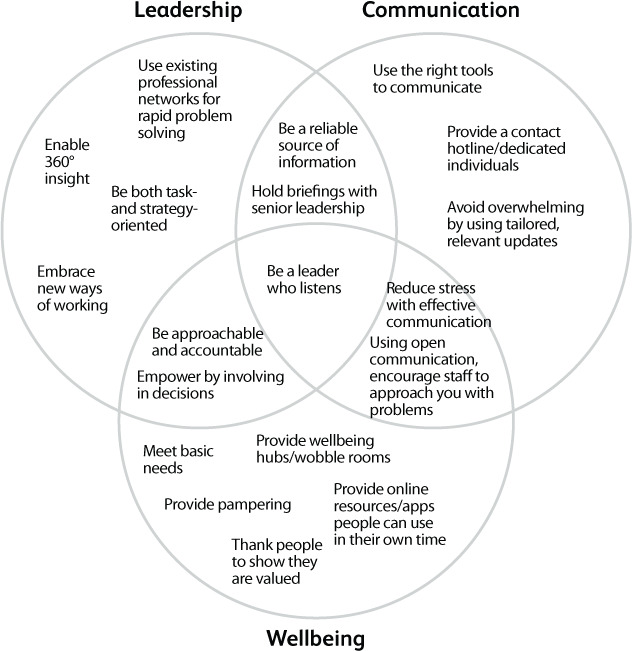

Our roles were rapidly transformed. With our teaching programme suspended, we met remotely, sharing knowledge and reflecting on what changes and challenges the pandemic response had brought us. We recognised our existing networks and experience meant that we were ideally positioned to lead on the junior doctor strategy in the first weeks of the pandemic. Our reflections on this explored below fall into three overlapping categories: firstly, our impact as middle leaders; secondly, the importance of effective communication and finally, how we could promote wellbeing (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Overlapping domains of RCP chief registrar leadership during the COVID-19 response.

Middle leadership

RCP chief registrars are uniquely placed as ‘middle leaders’ to address both the clinical and organisational challenges created by the COVID-19 pandemic. We have developed a broad set of leadership competencies, including communication, appropriate senior links, followership and a sound understanding of current healthcare practice. Middle leadership is about both setting vision and being visible, compassionate, and adaptable.

One key role for middle leadership is to facilitate change by integrating different perspectives. Our experience of delivering clinical care provides insights for senior management, who utilise their relationships with us to gain our perspective on proposed changes.2 Offering personal insight and rapid feedback from our frontline colleagues increases the chance of early buy-in from clinicians on the ground (see Box 1).3

Box 1.

Giving junior doctors more control over working patterns

In some trusts, chief registrars have actively engaged junior doctors in determining their own working patterns. The process included the following stages:

Results from surveys assessing the effect of giving junior doctors control over their rotas show this has a positive impact on wellbeing. |

The presence of an RCP chief registrar as a senior clinical trainee and in senior level meetings gives us insight, approachability and accountability to both the directorate and our clinical team.

Communicating effectively

Effective communication is essential for good clinical practice.4 Most clinicians work with a consistent group of colleagues in a familiar environment and are used to applying evidence-based medicine to their day-to-day practice. COVID-19 has resulted in unprecedented uncertainty. How can middle leaders foster effective communication in midst of a rapidly unfolding pandemic?

Using the right tools

Communications apps have seen a surge in use during the pandemic; for example, WhatsApp use went up 40% in the early weeks.5 These technological tools have become an essential way to disseminate information among healthcare workers. Traditionally trusts have shared updates using email and intranet pages. However, a generation of junior doctors are used to receiving information on smartphones and have limited access to desktops. Bulletins can be sent via messaging groups and local clinical guidelines via media like the ‘Induction’ app (https://induction-app.com) (Box 2).

Box 2.

Creating an open communication strategy

| At several trusts we have created a social messaging group and invited all the junior doctors to join. The group is used to send out urgent updates and invitations to virtual meetings and briefings. Posting rights are limited to admin team to ensure accurate information and avoid overload. Questions are sent directly to chief registrars or through representatives. |

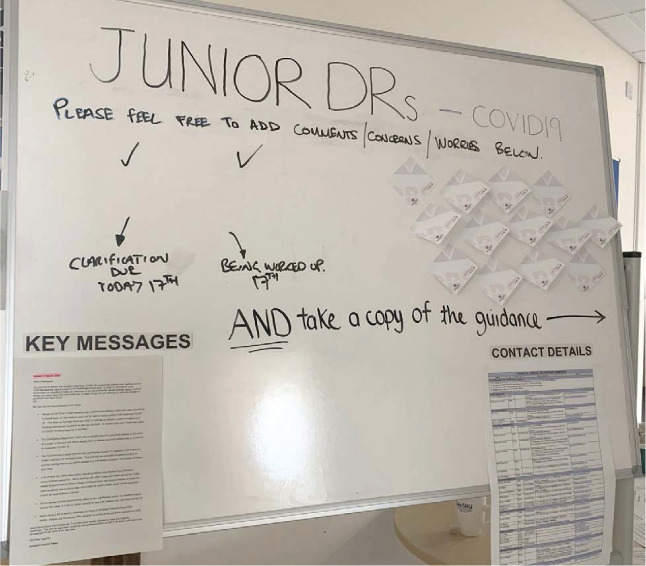

| Some trusts have also installed a physical notice board next to the doctors’ mess to display hard copies of latest guidance and for doctors to post questions, anonymously if preferred (Fig 2). |

| Informal feedback and survey results demonstrate a very positive response among junior doctors. |

Fig 2.

Example of junior doctors COVID-19 noticeboard – Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Trust

The pandemic has required many staff to address the additional challenge of remote working, discovering different approaches are needed when face-to-face interactions are limited. Social distancing and physical separation have made change initiatives more difficult, given the challenges they pose to coalition formation, the communication of vision and empowerment of action – the key principles of change theory.6 We have been able to use technological strategies (eg email, direct messaging, video conferencing, Microsoft Teams) to maintain and broker relationships. Formality and response time varies, so goals and priorities must be set clearly, and regular progress reviews scheduled in.

Psychological benefit of good communication

The volume of communications traffic can be overwhelming. Providing good quality, honest information is important to reduce anxiety in any traumatic situation.7 Briefing meetings with senior leaders gives juniors a seat at the (physical or virtual) table, reinforcing that they are part of the pandemic response effort and fostering a sense of connection.

No such thing as a silly question

Junior doctors need to be able to share their concerns without fear of embarrassment; if one person is asking something, it is likely that others are thinking the same. We recommend the use of dedicated ‘hotlines’, via telephone, email or nominated individuals, giving staff the opportunity to raise unanticipated and person-specific questions. We can simultaneously respond sensitively to individuals, while using networks to escalate questions and disseminate answers to the cohort as a whole.

Promoting wellbeing

A fundamental concept of flight safety is to ‘put on your own mask before helping others’. The response to COVID-19 has put all healthcare workers under significant and unrelenting strain for several months. The GMC report Caring for doctors, caring for patients examined factors impacting on the mental health and wellbeing of doctors.8 Drawing on its concepts, we explore ways to promote junior doctor wellbeing.

A feeling of autonomy

Engaging junior doctors in creating solutions allows them to influence a situation that is largely beyond their control. As described in Box 1, developing rotas or patient pathways is empowering and reduces the feeling that situation is happening ‘to’ them.

Promoting autonomy includes recognising individual preferences in accessing support. Some prefer mindfulness or meditation strategies and can be signposted to apps such as Headspace9 or Sleepio10 or other online content (eg the RCP mental health and wellbeing resource11). Others prefer one to one interactions through virtual assessments such as the Practitioner Health Programme (www.practitionerhealth.nhs.uk) or via peer support.

A sense of belonging

The pandemic has created a strong sense of community both within the NHS and in wider society. The RCP chief registrars are taking active steps to fully integrate junior doctors into their trusts’ responses to the current pandemic. Staff can be made to feel cared for by their employing organisation if it meets their basic needs such as food and accommodation, with extra support such as the creation of ‘wobble rooms’ (wellbeing hubs – see Box 3, Fig 3). Junior doctor fora have been reconvened remotely and Q&A sessions attended by executive teams are well attended. Thanking those around us and acknowledging their efforts is a simple but important way to show people they are valued.

Box 3.

A space for some space

In a number of trusts chief registrars have organised a designated space away from the clinical area for junior doctors to focus on their wellbeing. These can offer:

Through surveys, staff have reported that such schemes are highly valued. |

Fig 3.

Wellbeing hub at Medway NHS Foundation Trust.

Needing to feel competent

Many of us have worked outside our comfort zones in recent months, challenging our boundaries of competence and confidence at work. RCP chief registrars have worked with their trusts to facilitate additional training for doctors preparing for the challenges ahead (eg see Box 4). For the widest reach during social distancing, multiple modalities are being used, including e-learning, face-to-face clinical skills sessions and live-streamed Q&A sessions.

Box 4.

CLIVE – using shared learning to build competence in treating COVID-19

| Prior to COVID-19, Royal Derby Hospital set up a clinical learning portal called CLIVE (‘Clinical Learning Is Very Exciting!’) on the Trust intranet, with the aim of sharing interesting cases and learning from clinical events. |

| In current times CLIVE is being used as a way of maintaining some ‘teaching at a distance’ for medical and nursing staff, as well as keeping in touch with clinical updates. This allows rapid development of competence of managing patients with COVID-19. |

| This scheme has received praise from the senior leadership team at the trust. |

Anxiety can result from the fear of making unfamiliar and potentially unsupported decisions. Reminding junior doctors that they will be working with seniors and educating them on agreed guidance goes some way to addressing this. Supportive supervision of all staff working in an unfamiliar environment will allow wellbeing needs and any adverse effects of work on mental health to be flagged up and addressed.

Conclusion

The RCP chief registrar programme has given us the opportunity to experience organisational leadership from a clinical standpoint. Our mentors have been supportive in allowing our ideas to take shape and be implemented at pace during the COVID-19 pandemic response, actively encouraging us to use our unique position to influence widely across our trusts.

We consider this time as an epoch in the evolving role of the RCP chief registrar. We are working as rota designers, quality improvers, communications managers, sources of pastoral support and wellbeing champions. We have discovered how quickly an integrated leadership approach can drive change and many of our ideas have been fast-tracked through organisational systems that were previously challenging to negotiate. In recent months we have embraced new ways of working and new technologies, and are learning to provide concise, accurate, accessible communication in a time of information overload. We have promoted wellbeing by developing competence and a sense of belonging. Both quantitative and qualitative feedback from junior doctors has shown that our interventions have been well received, and a number of chief registrars have received messages of thanks and acknowledgment of our value from the most senior leaders within our trusts. Our challenge now is to build on our initial accomplishments, spreading good practice across our network.

We have demonstrated the ongoing value of the chief registrar role to the NHS by providing innovative solutions in changing situations. We feel confident that when we reflect on our year as RCP chief registrars, we will be proud of our accomplishments in the face of uncertainty and adversity.

References

- 1.Royal College of Physicians . Chief registrar programme. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/chief-registrar-programme [Accessed 20 April 2020].

- 2.Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust public inquiry. London: The Stationery Office, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.King's Fund . Leadership and engagement for improvement in the NHS: Together we can. King's Fund, 2012. Available from www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/leadership-engagement-for-improvement-nhs. [Google Scholar]

- 4.General Medical Council . Good medical practice. GMC, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez S. WhatsApp has seen a 40% increase in usage due to COVID-19 pandemic. https://techcrunch.com/2020/03/26/report-whatsapp-has-seen-a-40-increase-in-usage-due-to-covid-19-pandemic/ [Accessed 3 April 2020].

- 6.Kotter JP. Leading change. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Billings J, Kember T, Greene T, et al. Guidance for planners of the psychological response to stress experienced by hospital staff associated with COVID: early interventions. COVID Trauma Response Working Group, 2020. www.aomrc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Guidance-for-planners-of-the-psychological-response-to-stress-experienced-by-HCWs-COVID-trauma-response-working-group.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.West M, Coia D. Caring for doctors, caring for patients: How to transform UK healthcare environments to support doctors and medical students to care for patients. General Medical Council, 2019. www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/caring-for-doctors-caring-for-patients_pdf-80706341.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Headspace . Headspace for the NHS. https://help.headspace.com/hc/en-us/articles/360044971154-Headspace-for-the-NHS.

- 10.Sleepio . Sleepio: a science-based approach. https://onboarding.sleepio.com/sleepio/nhs-staff [Accessed 20 April 2020].

- 11.Royal College of Physicians . Mental health and wellbeing resource. RCP, 2020. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/mental-health-and-wellbeing-resource [Accessed 3 April 2020]. [Google Scholar]