Abstract

Objective:

Amyloid accumulation, the pathological hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease, may predispose some older adults to depression and cognitive decline. Deposition of amyloid may occur prior to the development of cognitive decline. It is unclear whether amyloid influences antidepressant outcomes in cognitively intact depressed elders.

Design:

A pharmacoimaging trial utilizing florbetapir(18F) PET scanning followed by two sequential 8-week antidepressant medication trials.

Participants:

Twenty-seven depressed elders who were cognitively intact on screening.

Measurements and Interventions:

After screening, diagnostic testing, assessment of depression severity and neuropsychological assessment, participants completed florbetapir(18F) PET scanning. They were then randomized to receive escitalopram or placebo for 8 weeks in a double-blinded two-to-one allocation rate. Individuals who did not respond to initial treatment transitioned to a second open-label trial of bupropion for another 8 weeks.

Results:

Compared with 22 amyloid-negative participants, 5 amyloid-positive participants exhibited significantly less change in depression severity and a lower likelihood of remission. In the initial blinded trial, 4 of 5 amyloid-positive participants were non-remitters (80%), while only 18% (4 of 22) of amyloid-negative participants did not remit (p=0.017; Fisher’s Exact test). In separate models adjusting for key covariates, both positive amyloid status (t=3.07, 21 df, p=0.003) and higher cortical amyloid binding by standard uptake value ratio (t=2.62, 21 df, p=0.010) were associated with less improvement in depression severity. Similar findings were observed when examining change in depression status across both antidepressant trials.

Conclusions:

In this preliminary study, amyloid status predicted poor antidepressant response to sequential antidepressant treatment. Alternative treatment approaches may be needed for amyloid-positive depressed elders.

INTRODUCTION

Amyloid beta (Aβ) accumulation may predispose some older adults to develop depressive episodes.1 In cognitively intact older adults, greater Aβ burden is cross-sectionally and longitudinally associated with greater depressive symptoms.2,3 In turn, cortical amyloid and depressive symptoms may interact to influence cognitive decline.4,5 Late-life depression (LLD) in the absence of dementia is associated with a higher plasma Aβ40:Aβ42 ratio,6 similar to what is seen in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and also an increased risk for cognitive decline and developing AD.7 While several studies demonstrated that depressed elders exhibit a greater cortical Aβ burden than never-depressed older adults,8–10 there are also negative reports.11

Beyond cognitive decline,4,5 it is unclear whether cortical amyloid influences clinical outcomes in nondemented LLD. Some work suggests that increasing levels of treatment resistance in LLD may be associated with increased Aβ deposition, particularly in the temporal lobe.12 This ambiguity is in contrast to our broader understanding of pathological brain and cognitive aging in LLD, as cerebrovascular disease, executive dysfunction and episodic memory impairment are associated with poor antidepressant responses.13 Antidepressant medications have poor efficacy for depression in dementia,14–16 however it is unclear whether Aβ or other neuropathological factors contribute to treatment resistance in depressed patients with dementia.

The purpose of this preliminary study was to examine how Aβ in nondemented LLD is associated with response to antidepressant medications. We hypothesized that greater cortical amyloid burden and amyloid positivity would be associated with less improvement in depression severity and lower frequency of achieving remission with sequential antidepressant treatment.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were recruited at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC; Nashville, TN) from clinical referrals and community advertisements. They enrolled in a pharmacoimaging trial combining baseline MRI with sequential antidepressant treatment (NCT02332291). Participants were then eligible to participate in this optional ancillary study that added a baseline florbetapir (18F) PET scan. Enrollment in this ancillary study ranged from June 2018 through March 2020.

Inclusion criteria specified subjects be age 60 years or older and meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for major depressive disorder with a Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)17 score of ≥ 15. Participation required a Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE)18 score > 24 and no diagnosis of dementia or other neurological disorders. Additional exclusion criteria included: 1) other Axis 1 diagnoses, other than anxiety symptoms occurring during depressive episodes; 2) history of alcohol or drug abuse or dependence in the last 3 years; 3) history of psychosis; 4) presence of acute suicidality; 5) acute grief in last month; 6) MRI contraindications; 7) a failed trial of escitalopram in the current episode; 8) ECT in the last 6 months; and 9) current psychotherapy.

All participants provided written informed consent. The VUMC Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Assessments, Study Visits, and Antidepressant Treatment

Diagnosis and evaluation of exclusionary psychiatric disorders was determined using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (version 5.0).19 After determination of eligibility, individuals taking an antidepressant medication had that tapered and discontinued over several weeks. After a two-week period without antidepressant medications, they completed their baseline assessment, including neuropsychological testing, MRI, and PET scans. Participants then started study medication.

Neuropsychological Testing

Neuropsychological testing procedures have been previously described.20 Briefly, the neuropsychological test battery included a range of tests probing cognitive domains impaired in LLD. Similar to our previous approach,21,22 we combined tasks into rationally constructed cognitive domains. We then created z-scores for each measure based on the performance of all participants in the larger parent study and averaged the z-scores for all tests within each domain for each individual. Domains and tests included:

Episodic Memory: Word List Memory Recall (delayed), Paragraph Recall test, Constructional Praxis test, and Benton Visual Retention Test.

Executive Function: Controlled Oral Word Association test, Mattis Dementia Rating Scale Initiation-Perseveration Subscale, Trail-Making Test Part B, the Stroop test color-word interference condition, and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

Language Processing: Shipley vocabulary test, Boston Naming Test, and Stroop test word reading condition.

Processing Speed: Symbol-Digit Modality Test, Stroop test color naming condition, Trail-Making Test Part A.

Working Memory: Digits Forwards, Backwards, and Ascending.

Antidepressant Treatment

Antidepressant treatment included two study phases, each lasting 8 weeks. In both phases, depression severity was assessed every two weeks, with participants completing in-clinic visits at baseline, week 4, and week 8, with telephone visits in weeks 2 and 6.

In the double-blinded study phase 1, participants were randomized to either escitalopram or placebo in a 2 to 1 allocation. Randomization was stratified by white matter hyperintensity (WMH) severity, operationalized as “high” or “low” based on the median WMH volume determined from prior studies. Participants, study physicians, and neuroimaging staff were blinded to treatment allocation. Assignment to treatment arm was done through a sequential predetermined assignment created by the study statistician (HK) and managed by the Vanderbilt Investigational Drug Service. Dosing started at 10mg daily (or placebo) and could increase to 20mg as early as week 2. If a participant did not respond or remit during phase 1, they entered phase 2. Phase 2 included open-label treatment with bupropion (24-hour release formulation), beginning at 150mg daily, increasing to 300mg over 1–2 weeks. The dose could be further increased to the maximum of 450mg daily at week 4.

In both phases, the study physician and the study participant jointly decided on titrating above the minimum therapeutic dose (escitalopram 10mg daily and bupropion 300mg daily). For this ancillary study, the majority of participants in each phase completed the full 8 week duration and tolerated the minimum target dose. Only one participant could not tolerate study medication in either phase and ended both phases early.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Participants were scanned on a research-dedicated 3.0T Philips Achieva whole-body scanner (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) using body coil radiofrequency transmission and a 32-channel head coil for reception. Structural imaging included a whole-brain T1- weighted MPRAGE image with TR = 8.75ms, TE = 4.6ms, flip angle=9 degrees, and spatial resolution = 0.89 × 0.89 × 1.2 mm3 plus a FLAIR T2-weighted imaging conducted with TR = 10000ms, TE = 125ms, TI = 2700ms, flip angle = 90 degrees, and spatial resolution = 0.7 × 0.7 × 2.0mm3.

WMH volumes, findings on T2- weighted or FLAIR images related to cerebral ischemia, were measured using the Lesion Segmentation Toolbox.23 These analyses, as previously described,20,24 were implemented through the VBM8 toolbox in SPM8 using the threshold of 0.3. Per protocol and based on prior preliminary analyses across earlier datasets, WMH severity was determined as being “high” or “low” using a cerebral WMH volume of 3.86ml. This was used to stratify randomization into study phase 1.

Florbetapir (18F) PET Scan Acquisition and Analyses

Florbetapir image data were acquired with a Philips Vereos PET/CT scanner. Florbetapir was administered as a single 370 mBq (10mCi) intravenous bolus with acquisition of image data beginning 40–50 minutes later. Data were acquired in four 5-minute frames with a voxel size of 2mm isotropic and field of view (FOV) of 256mm.

To quantify cortical Aβ, the four florbetapir image frames were coregistered using mcflirt from FSL 25 to create a single mean volume. This mean volume was then registered using mri_coreg to the subject’s FreeSurfer space as derived from their MPRAGE image. The transform from this registration was inverted to move the FreeSurfer ROIs to the PET space.

Following ADNI procedures for florbetapir processing, we created a cortical composite gray matter standard uptake value ratio (SUVr) for analyses. We extracted florbetapir binding means from FreeSurfer-defined gray matter within four large regions, including the frontal lobe (excluding the paracentral and precentral gyri), the lateral parietal lobe, the lateral temporal lobe, and the anterior and posterior cingulate gyri.26 Florbetapir binding means from the whole cerebellum were used to calculate the cortical Aβ SUVr. This cortical Aβ SUVr was used as a continuous measure in analyses and also used to dichotomize Aβ-status (amyloid positive or negative), using a cutoff of 1.11.27

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted in R version 4.0.0 (https://rstudio.com). Summary statistics were utilized to describe group characteristics. Group differences between Aβ-status were tested using pooled, two-tailed t-tests or a Welch’s t-test if Levene’s Test of Homogeneity of Variance indicated unequal variances. Separate general linear models (GLMs) examined effects of Aβ-status on z-scored cognitive variables adjusting for age, gender, and education. The primary depression outcome variable was change in MADRS over the first antidepressant trial. Secondary outcomes examined change in MADRS over both trials and dichotomous remission status across both trials, defining remission as a final MADRS < 8. Dichotomous Aβ-status (i.e., amyloid positive/negative) was the primary imaging measure, with cortical Aβ SUVr being secondary. One subject entered and ended both trials early due to tolerability problems. As the only missing data were five data points across both trials for this individual, we used a single regression imputation to impute these missing data. There were no other missing data.

Depression outcomes from the initial treatment phase and across both phases were examined using multiple regression GLMs. Separate GLMs examined change in MADRS (baseline to 8-week) as a function of Aβ-status or cortical SUVr, controlling for baseline MADRS score, age, gender, and treatment arm (placebo or escitalopram). Subsequent logistic regression models examined remission status as a function of the same independent variables and covariates. Results were corrected using 10,000 permutations of the permutation of regressor residuals test implemented in the R package ‘glmperm’ (version 1.0–5, http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/glmperm/index.html). The permutation of regressor residuals test replaced the variable of interest by the residuals of the variable of interest regressed on all other independent variables to yield an exact p-value appropriate for inferring results from small sample sizes.28 Exploratory GLMs examined associations between cognitive domain z-scores and MADRS change after adjusting for age and education. We planned to add cognitive domains that were significantly associated with MADRS change as confounds to models assessing the relationship between amyloid measures and MADRS change.

RESULTS

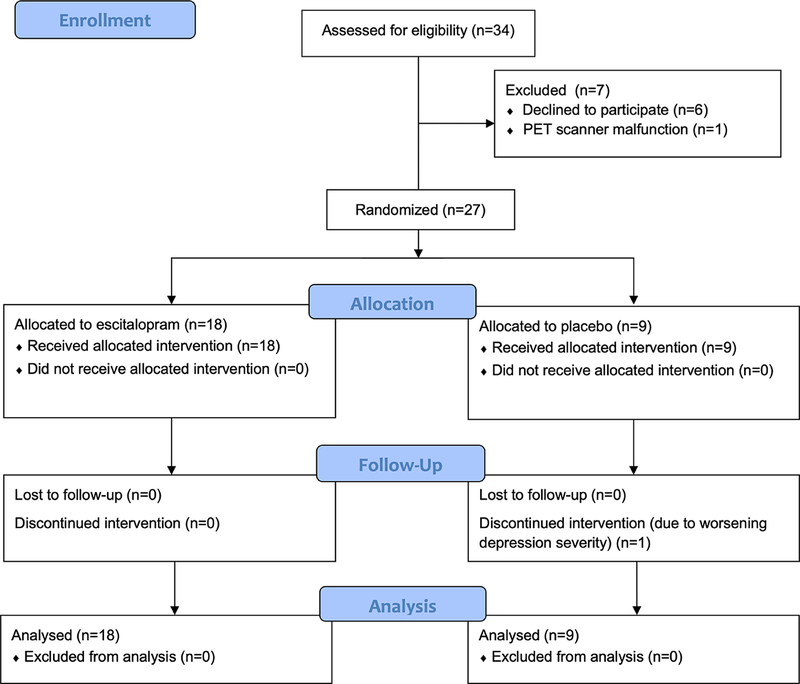

We screened and discussed the study with 34 potential participants identified through the parent study (see Figure 1, CONSORT diagram). Six decided not to participate due to concerns over the infusion and radiation exposure. One agreed to participate and provided informed consent but could not complete PET imaging due to a scanner malfunction. The final sample consisted of 27 older adults (Table 1; age range 60–76y) with a moderate level of depression severity based on mean baseline MADRS score (range 15–34). Participants did not exhibit cognitive impairment on MMSE screening (mean = 29.4, SD=0.8, range 28–30) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study CONSORT Diagram

Table 1:

Demographic characteristics of the sample

| Overall Sample (N=27) | Aβ negative (N=22) | Aβ positive (N=5) | |

| Age (y) | 67.9 (3.9) | 67.3 (4.1) | 70.8 (1.5) |

| Sex (% female) | 55.6% (N=15) | 50.0% (N=11) | 80.0% (N=4) |

| Education (y) | 15.5 (2.3) | 15.4 (2.0) | 16.2 (3.5) |

| WMH volume (ml) | 0.9 (1.2) | 1.0 (1.3) | 0.5 (0.8) |

| MMSE | 29.4 (0.8) | 29.5 (0.7) | 29.2 (1.1) |

| MADRS, Baseline | 24.9 (5.4) | 24.7 (5.9) | 26.0 (2.5) |

| MADRS, Phase 1 End | 10.0 (9.7) | 8.0 (9.3) | 18.6 (7.0) |

| Phase 1 Remitted | 70.4% (N=19) | 81.8% (N=18) | 20% (N=1) |

| Phase 1 Dose (mg) | 17.8 (4.24) | 17.7 (4.3) | 18.0 (4.5) |

| (N=8) | (N=4) | (N=4) | |

| MADRS, Phase 2 End | 19.0 (10.3) | 20.8 (14.5) | 16.8 (5.4) |

| Phase 2 Dose (mg) | 318.7 (96.13) | 262.5 (75.0) | 375.0 (86.6) |

Continuous measures presented as mean (standard deviation) and categorical variables presented as % (number). Phase 1 dose calculated on number of pills as participants received either escitalopram or matching placebo. Phase 2 involved open-label bupropion administration.

CIRS = Cumulative Illness Rating Score; MADRS = Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale; mg = milligrams; ml = milliliters; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Exam; WMH = white matter hyperintensity

Five participants were amyloid positive. Neither baseline MADRS (t=0.775, 15.39 df, p=0.450), MMSE (t=0.588, 4.71 df, p=0.584), WMH volume (t=1.18, 25 df, p=0.247) nor assignment to initial treatment arm (t=0.246, 25 df, p=0.808) significantly differed by Aβ-status (Table 1). After adjusting for age and education, amyloid status was not associated with performance in any cognitive domain (data not shown; p’s=0.201–0.894).

In the blinded first trial involving randomization to escitalopram or placebo (mean doses: drug: 17.8mg, SD=4.4mg; placebo: 17.8mg, SD=4.3mg), 19 subjects remitted while 8 did not. Four Aβ-positive participants were non-remitters (80%), in contrast to 4 of 22 (18%) of Aβ-negative participants being non-remitters (p=0.017; Fisher’s Exact test). Our primary outcome was change in depression severity across the blinded first trial involving randomization to escitalopram or placebo. After adjusting for treatment arm, baseline MADRS score, age, and gender, Aβ status was significantly associated with change in depression severity (t=3.07, 21 df, p=0.003). We observed a mean 69.9% (range: 7%−100%) reduction in MADRS score for Aβ-negative subjects and a mean 29.1% (range: 4%−65%) reduction for Aβ-positive subjects. In this model, treatment arm assignment approached but did not achieve statistical significance (t=2.07, 22 df, p=0.051). In models with similar covariates, Aβ status was also significantly associated with the secondary outcome of remission status (z=2.40, p=0.002). Similar effects were observed when Aβ status was replaced by cortical Aβ SUVr measures in models examining MADRS change (t=2.62, 21 df, p=0.010) and remission rate (z=3.50, p=0.002).

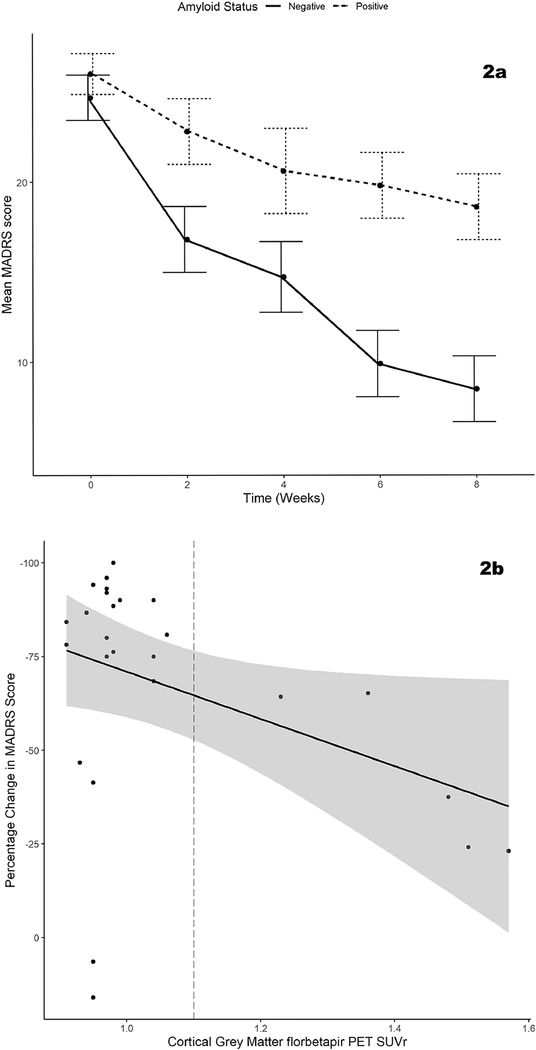

These findings persisted on expanding analyses to examine change across both blinded and open-label study phases (Figure 2). The 8 non-remitting subjects from the first trial entered this open-label study phase (mean dose = 318.8mg, SD=96.1mg), with only one remitting. Across both study phases, 4 of 5 Aβ-positive participants were non-remitters (80%), while 3 of 22 (14%) of Aβ-negative participants were non-remitters. In models adjusting for age, gender, baseline MADRS score, and treatment arm in the first trial, Aβ-status was associated with change in MADRS (t=2.10, 21 df, p=0.044; Figure 2a) and remission status (z=2.40, p=0.001). Similar effects were observed with cortical Aβ SUVr on MADRS change (t=2.10, 21 df, p=0.048; Figure 2b) and remission rate (z=3.90, p=0.001).

Figure 2. Amyloid effects on depression severity change with treatment.

Figure 2a displays change in MADRS score across by Aβ-status in Trial 1 (escitalopram vs placebo, weeks 0–8). Error bars display the standard error at each timepoint. Figure 2b displays the relationship between cortical Aβ SUVr and percent change in depressive symptoms from baseline across both trials to study completion, showing the regression line and 95% confidence interval.

Exploratory analyses examined whether the relationship between Aβ-status and MADRS change persisted after adjusting for cognitive performance. As an initial step, we examined whether cognitive domain performance predicting change in MADRS score. After adjusting for age, baseline MADRS score, and education, MADRS change was not significantly associated with any baseline cognitive domain measure (data not shown). As cognitive performance was not associated with MADRS change, we did not conduct further analyses.

DISCUSSION

Although a preliminary study, our primary finding in this small sample of cognitively intact, depressed older adults, is that greater Aβ burden is associated with poorer acute antidepressant response. As Aβ status was not associated with baseline cognitive performance in this sample, the effect of Aβ on the antidepressant response may potentially be independent of the effects of cognitive impairment on the antidepressant response.

This finding is concordant with work in AD demonstrating that antidepressants have poor efficacy for treating depression in dementia14–16 but extends those findings to cognitively unimpaired individuals with elevated cortical Aβ. Our current work suggests that the antidepressant treatment resistance observed in dementia may be related to AD neuropathology. Moreover, this adverse effect on treatment outcome may extend to individuals with greater Aβ burden who are earlier in the disease process and cognitively intact on clinical screening. Although the current study does not provide guidance about what antidepressant treatment approaches may benefit this group, there may be roles for neuromodulation, neurobiologically based psychotherapy, or cognitive remediation.29 There may additionally be future roles for anti-amyloid therapy in Aβ positive individuals with LLD,1 either to include them in AD prevention trials or to examine whether anti-amyloid therapy in these individuals may benefit depression.

It is important to consider the mechanism by which Aβ may contribute to poor antidepressant responses. The earliest accumulation of Aβ plaques occurs within default-mode network (DMN) regions,30 including the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), precuneus, and prefrontal cortex (PFC).31 Aβ deposition in turn is associated with alterations in resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) of the DMN, reported as both network disruptions (characterized by decreased rsFC) and network reorganizations (characterized by increased rsFC).32–34 Altered rsFC of the DMN is also reported in LLD 35–37 and successful antidepressant treatment is associated with changes in DMN rsFC.38 Assuming these dynamic changes in rsFC of the DMN contribute to the clinical antidepressant response, the presence of greater Aβ burden may decrease the ability of antidepressants to facilitate these critical functional network changes, resulting in treatment resistance. Alternatively, there may be underlying causes that independently contribute to Aβ accumulation, vulnerability to depression and antidepressant treatment resistance. For example, inflammation and cerebrovascular pathology are both associated with depression, poorer antidepressant response, and dementia.13,39

Although our findings are preliminary, they have potential clinical implications in understanding variability in antidepressant response in clinical populations. However, for several reasons this study alone should not be used as the sole rationale to use PET imaging or other techniques to assess Aβ burden in older adults with treatment resistant depression. First, we do not have a good treatment alternative, so a positive amyloid scan would not inform treatment choice. Second, the study’s relatively small sample size makes the results preliminary and raises issues about the generalizability of our findings.

Although our findings are robust and consistent across analyses, the study has limitations. Primarily, this study examined a small sample with a limited proportion of Aβ-positive participants. While performance deficits across a range of cognitive domains predict depression outcomes,13 the small sample size limited our ability to discern whether the effects of Aβ status on treatment response persist when adjusting for cognitive impairment, or to probe for potential interactive effects between Aβ, vascular disease and cognitive performance on depression outcomes. Future work could examine a sample better balanced between Aβ-positive and -negative subjects. Additionally, other markers of pathological brain aging such as tau deposition should be considered.

Despite these issues, this preliminary report provides a valuable insight that in some individuals with LLD, AD pathology may contribute to antidepressant treatment resistance. Further work is needed to confirm this finding, determine how AD pathology contributes to longer-term outcomes such as depression recurrence,40 and to establish alternative, effective treatments for Aβ-positive LLD.

Highlights.

1). What is the primary question addressed by this study?

Does cortical amyloid burden affect the response to antidepressant medications in patients with late-life depression who are cognitively intact on screening?

2). What is the main finding of this study?

In this preliminary study, high amyloid burden is associated with poor response and failure to achieve remission with sequential antidepressant treatment.

3). What is the meaning of the finding?

Cortical amyloid may contribute to antidepressant treatment resistance in late-life depression. Further work is needed to confirm these findings and determine the optimal treatment approach for amyloid positive individuals.

Acknowledgments

DISCLOSURES AND CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

This research was supported by National Institute of Health grants R01 MH102246, K24 MH110598, S10 OD012297, T32 AG058524, and CTSA award UL1 TR002243 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. This work was conducted in part using the resources of the Vanderbilt University Institute for Imaging Sciences and the Advanced Computing Center for Research and Education at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

Footnotes

The authors deny any conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mahgoub N,Alexopoulos GS: Amyloid Hypothesis: Is There a Role for Antiamyloid Treatment in Late-Life Depression? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016; 24:239–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yasuno F, Kazui H, Morita N, et al. : High amyloid-beta deposition related to depressive symptoms in older individuals with normal cognition: a pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016; 31:920–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donovan NJ, Locascio JJ, Marshall GA, et al. : Longitudinal Association of Amyloid Beta and Anxious-Depressive Symptoms in Cognitively Normal Older Adults . Am J Psychiatry 2018; 175:530–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson RS, Capuano AW, Boyle PA, et al. : Clinical-pathologic study of depressive symptoms and cognitive decline in old age. Neurology 2014; 83:702–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gatchel JR, Rabin JS, Buckley RF, et al. : Longitudinal Association of Depression Symptoms With Cognition and Cortical Amyloid Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults . JAMA Netw Open 2019; 2:e198964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nascimento KK, Silva KP, Malloy-Diniz LF, et al. : Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-beta levels in late-life depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res 2015; 69:35–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diniz BS, Butters MA, Albert SM, et al. : Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. Br J Psychiatry 2013; 202:329–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butters MA, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, et al. : Imaging Alzheimer pathology in late-life depression with PET and Pittsburgh Compound-B. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2008; 22:261–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tateno A, Sakayori T, Higuchi M, et al. : Amyloid imaging with [(18)F]florbetapir in geriatric depression: early-onset versus late-onset. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015; 30:720–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu KY, Hsiao IT, Chen CS, et al. : Increased brain amyloid deposition in patients with a lifetime history of major depression: evidenced on 18F-florbetapir (AV-45/Amyvid) positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2014; 41:714–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madsen K, Hasselbalch BJ, Frederiksen KS, et al. : Lack of association between prior depressive episodes and cerebral [11C]PiB binding. Neurobiol Aging 2012; 33:2334–2342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li P, Hsiao IT, Liu CY, et al. : Beta-amyloid deposition in patients with major depressive disorder with differing levels of treatment resistance: a pilot study. EJNMMI Res 2017; 7:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor WD, Aizenstein HJ,Alexopoulos GS: The vascular depression hypothesis: Mechanisms linking vascular disease with depression. Molecular Psychiatry 2013; 18:963–974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dudas R, Malouf R, McCleery J, et al. : Antidepressants for treating depression in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 8:CD003944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenberg PB, Drye LT, Martin BK, et al. : Sertraline for the treatment of depression in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010; 18:136–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banerjee S, Hellier J, Dewey M, et al. : Sertraline or mirtazapine for depression in dementia (HTA-SADD): a randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2011; 378:403–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montgomery SA,Asberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal of Psychiatry 1979; 134:382–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folstein MF, Folstein SE,McHugh PR: “Mini-mental state” a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research 1975; 12:189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. : The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Inventory (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1998; Suppl 20:22–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gandelman JA, Albert K, Boyd BD, et al. : Intrinsic Functional Network Connectivity Is Associated With Clinical Symptoms and Cognition in Late-Life Depression. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 2019; 4:160–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor WD, Boyd B, Turner R, et al. : APOE epsilon4 associated with preserved executive function performance and maintenance of temporal and cingulate brain volumes in younger adults. Brain Imaging Behav 2017; 11:194–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albert KM, Potter GG, McQuoid DR, et al. : Cognitive performance in antidepressant-free recurrent major depressive disorder. Depress Anxiety 2018; 35:694–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt P, Gaser C, Arsic M, et al. : An automated tool for detection of FLAIR-hyperintense white-matter lesions in Multiple Sclerosis . NeuroImage 2012; 59:3774–3783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abi Zeid Daou M, Boyd BD, Donahue MJ, et al. : Frontocingulate cerebral blood flow and cerebrovascular reactivity associated with antidepressant response in late-life depression. J Affect Disord 2017; 215:103–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, et al. : Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. NeuroImage 2002; 17:825–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landau SM, Breault C, Joshi AD, et al. : Amyloid-beta imaging with Pittsburgh compound B and florbetapir: comparing radiotracers and quantification methods. J Nucl Med 2013; 54:70–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landau SM, Mintun MA, Joshi AD, et al. : Amyloid deposition, hypometabolism, and longitudinal cognitive decline. Ann Neurol 2012; 72:578–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Potter DM: A permutation test for inference in logistic regression with small- and moderate-sized data sets. Stat Med 2005; 24:693–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexopoulos GS: Mechanisms and treatment of late-life depression. Transl Psychiatry 2019; 9:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmqvist S, Schöll M, Strandberg O, et al. : Earliest accumulation of β-amyloid occurs within the default-mode network and concurrently affects brain connectivity. Nature Communications 2017; 8:1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mintun MA, LaRossa GN, Sheline YI, et al. : [<sup>11</sup>C]PIB in a nondemented population. Neurology 2006; 67:446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheline YI,Raichle ME: Resting State Functional Connectivity in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. Biological Psychiatry 2013; 74:340–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mormino EC, Smiljic A, Hayenga AO, et al. : Relationships between Beta-Amyloid and Functional Connectivity in Different Components of the Default Mode Network in Aging. Cerebral Cortex 2011; 21:2399–2407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elman JA, Madison CM, Baker SL, et al. : Effects of Beta-Amyloid on Resting State Functional Connectivity Within and Between Networks Reflect Known Patterns of Regional Vulnerability. Cereb Cortex 2016; 26:695–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gandelman JA, Albert K, Boyd BD, et al. : Intrinsic Functional Network Connectivity Is Associated With Clinical Symptoms and Cognition in Late-Life Depression. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging 2019; 4:160–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andreescu C, Wu M, Butters MA, et al. : The default mode network in late-life anxious depression. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2011; 19:980–983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alexopoulos GS, Hoptman MJ, Kanellopoulos D, et al. : Functional connectivity in the cognitive control network and the default mode network in late-life depression. J Affect Disord 2012; 139:56–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karim HT, Andreescu C, Tudorascu D, et al. : Intrinsic functional connectivity in late-life depression: trajectories over the course of pharmacotherapy in remitters and non-remitters. Mol Psychiatry 2017; 22:450–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Byers AL,Yaffe K: Depression and risk of developing dementia. Nat Rev Neurol 2011; 7:323–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andreescu C, Ajilore O, Aizenstein HJ, et al. : Disruption of Neural Homeostasis as a Model of Relapse and Recurrence in Late-Life Depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2019; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]