The public health response to the coronavirus 19 (COVID-19) pandemic has included unprecedented changes in the delivery of substance use disorder (SUD) treatment and harm reduction services. Many outpatient medical visits rapidly transitioned to telemedicine, and community-based organizations like syringe service programs suspended or modified operations to comply with social distancing mandates. The resulting separation of people who inject drugs (PWID) from medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) and HIV prevention and other harm reduction services threatened to exacerbate existing HIV outbreaks among PWID.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, uptake of evidence-based HIV prevention strategies, including low-barrier HIV testing and treatment, MOUD, sterile injection equipment and condom distribution, and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), were inadequate among PWID (Bazzi et al., 2018). The injection of opioids and psychostimulants, including illicitly manufactured fentanyl and methamphetamine, have contributed to recent HIV outbreaks among PWID across the United States (Alpren et al., 2019; Evans et al., 2018; Golden et al., 2019; Peters et al., 2016). In Boston, where we practice, public health officials began alerting providers to clusters of new HIV infections among largely homeless PWID in early 2019 (Brown & Jaeger, 2019). Past public health emergencies and other large-scale events—as well as the measures to mitigate them—have increased HIV risk among PWID by impacting drug market characteristics, drug-related and sexual risk behaviors, and access to essential HIV prevention and SUD treatment services (Pouget et al., 2015; Strathdee et al., 2006). This evidence, combined with our local experience, substantiates concerns that COVID-19 could drive a further surge of new HIV infections in this population.

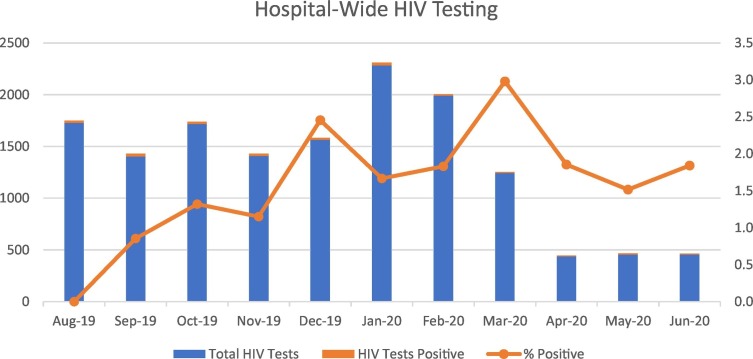

Predictably, though no less alarmingly, modified COVID-19 operations coincided with a substantial drop in the volume of HIV testing at Boston Medical Center (BMC), a large, urban safety-net hospital that diagnoses more new HIV infections per year than any other institution in Massachusetts (Johns, 2020). The total number of HIV tests performed between March 16 and April 30, 2020, was 86% lower than the prior 45-day period, and testing dropped by 92% in ambulatory clinics (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Hospital-wide HIV testing volume.

Faster Paths is the low-barrier, outpatient SUD bridge clinic at BMC that offers rapid access to MOUD, outpatient medically managed withdrawal, overdose and HIV prevention services, and linkage to long-term SUD care after stabilization. Our population reports frequent injection and sexual behaviors that increase the risk of HIV transmission, and we provide HIV screening for all new patients on an opt-out basis. Because many of our patients lack the resources required for telemedicine, Faster Paths continued to offer in-person visits during modified COVID-19 operations (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Operations changes to reduce COVID-19 transmission in low-barrier SUD treatment and harm reduction programs.

| Strategy | Faster Paths | Project Trust |

|---|---|---|

| Personal protective equipment (PPE) |

|

|

| Physical space |

|

|

| Staffing |

|

|

| Technology |

|

|

| Clinical approach |

|

|

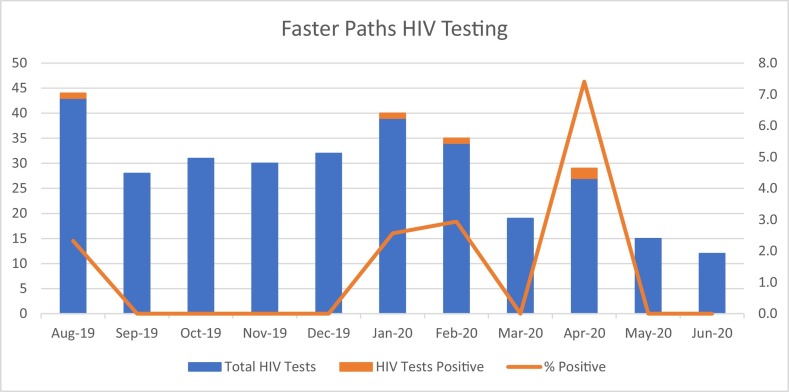

Under normal circumstances, Faster Paths sees approximately 50 unique patients for 210 visits and completes 35 HIV tests per month, typically diagnosing 0–2 new HIV infections per year. During the first 45 days of modified COVID-19 operations, our in-person visit and HIV testing volumes both dropped by half (Fig. 2 ). The patients who we continued to see in person were those at the highest HIV risk based on their reported behaviors. In April 2020, two of 27 HIV antigen/antibody tests (Ag/Ab) run in Faster Paths (7.4%) identified new HIV cases associated with injection behaviors. Across the institution, despite screening significantly fewer patients, Faster Paths diagnosed 15 new injection-associated cases between January and June 2020, vastly exceeding the baseline rate of 7.5 injection-associated cases per year in 2018–2019, and increasing the proportion of new HIV infections associated with injection to 48% from a baseline of 15%. This large shift is reflective of both ongoing high transmission among PWID and the drop off in testing in traditional ambulatory clinics during the pandemic.

Fig. 2.

Faster Paths HIV testing volume.

To respond to the colliding crises of addiction, HIV, and COVID-19, we have implemented a number of innovative strategies. Within Faster Paths, we have notified providers about the ongoing HIV outbreak and updated our clinic templates to more explicitly support providers in assessing HIV risk and offering PrEP and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) to eligible candidates, guided by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria and local experience (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: US Public Health Service, 2018; Dominguez et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2019) (Table 2 ). According to provider visit notes, the rate of in-person visits that addressed PEP or PrEP rose from 16% in the last two weeks of March to 22% in April 2020. Although our data cannot be used to determine, causally, whether increased PEP and PrEP offers observed in April should be attributed to the change in template, anecdotally, providers report that it is helpful to incorporate HIV risk assessments systematically, as they often face multiple competing demands during visits. We offer “PEP-to-PrEP” support to patients at high risk of acute HIV infection (Taylor et al., 2019) and encourage patients who inject drugs or have sexual partners who inject drugs to undergo HIV testing monthly instead of annually as recommended in current guidelines. Additionally, we have redoubled our efforts to confirm primary and alternate means of contact to ensure we are able to reach patients in the event of a positive result; when patients lack phones, we encourage them to reach out to us (e.g., via friends' or street outreach workers' phones) to receive results. When patients cannot be reached about a positive test result, we mobilize street outreach and local Department of Public Health resources; through these methods, we have reached all patients newly diagnosed in Faster Paths in 2020.

Table 2.

Eight bullet points added to Faster Paths note templates to support HIV risk assessment and PEP/PrEP provision.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In collaboration with Project Trust, our community-based, hospital-affiliated drop-in center for PWID, we also expanded street outreach and drop-in hours (via an outdoor tent to reduce COVID-19 transmission) to enable point-of-care rapid HIV testing when other local services were closed. When Boston Medical Center and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts opened a COVID-19 Recuperation Unit (CRU), a respite facility for people experiencing homelessness with COVID-19, Project Trust harm reduction specialists mobilized to staff the CRU, offering rapid HIV testing to reach patients unwilling to undergo lab-based testing. Additionally, our teams have offered increased quantities of sterile injection equipment, condoms, and other harm reduction supplies to mitigate possible COVID-related barriers to access in this socially marginalized population.

As addiction treatment teams move forward in the coming months, we must incorporate lessons learned from the pandemic. In Faster Paths, where in-person visit volume dropped by half, our overall visit volume has remained close to our pre-COVID baseline due to the expansion of telemedicine for MOUD initiation and follow-up. Although many of our patients lack phones and private spaces for telemedicine, we have found that we can successfully start and continue buprenorphine by partnering with harm reduction specialists doing street-based outreach (Harris et al., 2020). Our harm reduction specialists can perform phlebotomy in the field, and the protocols that have been successful for street-based MOUD delivery can and should be adapted for HIV prevention services like PEP and PrEP, enabling us to reach patients who are unwilling or unable to come into the medical center.

The staggering HIV incidence seen among PWID at our institution during the COVID-19 pandemic should serve as a call to action for SUD providers to integrate low-barrier HIV prevention services—including condom and safer injection equipment distribution, on-demand HIV testing with rapid testing available for those who decline phlebotomy, low-barrier MOUD, rapid HIV treatment initiation, and PEP and PrEP—into their programs. The COVID-19 pandemic will have many lasting impacts on SUD treatment, and SUD treatment programs should prioritize comprehensive HIV prevention services alongside MOUD and traditional harm reduction services. As addiction specialists, it is time for us to take this on.

Author statement

Jessica Taylor: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. Glorimar Ruiz-Mercado: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing. Heather Sperring: Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing. Angela Bazzi: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Bureau of Substance Addiction Services [1NTF230M03163724179] (Taylor), by a grant from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Sciences, Office of HIV/AIDS [INTF4944MM3181926007] (Ruiz-Mercado, Sperring), by an award from the Boston Public Health Commission for Community Based Prevention [FY20020704] (Ruiz-Mercado), and by a National Institutes of Health Boston Public Health Commission [K01DA043412] (Bazzi). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the funders.

Declaration of competing interest

Glorimar Ruiz-Mercado and Heather Sperring are partially funded by a Frontlines of Communities in the United States (FOCUS) grant from Gilead Sciences that supports HIV, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus screening and linkage to care. Gilead Sciences had no role in the development of this commentary.

References

- Alpren C., Dawson E.L., John B., Cranston K., Panneer N., Fukuda H.D.…Buchacz K. Opioid use fueling HIV transmission in an urban setting: An outbreak of HIV infection among people who inject drugs—Massachusetts, 2015–2018. American Journal of Public Health. 2019:e1–e8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzi A.R., Biancarelli D.L., Childs E., Drainoni M.-L., Edeza A., Salhaney P.…Biello K.B. Limited knowledge and mixed interest in pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among people who inject drugs. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2018;32(12):529–537. doi: 10.1089/apc.2018.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C., Jaeger J.L. Increase in newly diagnosed HIV infections among persons who inject drugs in Boston. 2019, January 25. https://www.bphc.org/whatwedo/infectious-diseases/Documents/Joint_HIV_in_PWID_advisory_012519%20(1).pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: US Public Health Service Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2017 Update: a clinical practice guideline. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf

- Dominguez K.L., Smith D.K., Thomas V., Crepaz N., Lang K., Heneine W., McNicholl J.M., Reid L., Freelon B., Nesheim S.R., Huang Y.(.A.)., Weidle P.J. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV—United States, 2016 (cdc:38856) 2016. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/38856

- Evans M.E., Labuda S.M., Hogan V., Agnew-Brune C., Armstrong J., Periasamy Karuppiah A.B.…Mark-Carew M. Notes from the field: HIV infection investigation in a rural area - West Virginia, 2017. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2018;67(8):257–258. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6708a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden M.R., Lechtenberg R., Glick S.N., Dombrowski J., Duchin J., Reuer J.R.…Buskin S.E. Outbreak of human immunodeficiency virus infection among heterosexual persons who are living homeless and inject drugs - Seattle, Washington, 2018. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2019;68(15):344–349. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6815a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M., Johnson S., Mackin S., Saitz R., Walley A.Y., Taylor J.L. Low barrier tele-buprenorphine in the time of COVID-19: A case report. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000682. (Publish Ahead of Print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns B. 2020, October 2. HIV infections reported by BMC [personal communication] [Google Scholar]

- Peters P.J., Pontones P., Hoover K.W., Patel M.R., Galang R.R., Shields J.…Indiana HIV Outbreak Investigation Team HIV infection linked to injection use of oxymorphone in Indiana, 2014-2015. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(3):229–239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1515195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouget E.R., Sandoval M., Nikolopoulos G.K., Friedman S.R. Immediate impact of Hurricane Sandy on people who inject drugs in New York City. Substance Use & Misuse. 2015;50(7):878–884. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.978675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee S.A., Stachowiak J.A., Todd C.S., Al-Delaimy W.K., Wiebel W., Hankins C., Patterson T.L. Complex emergencies, HIV, and substance use: No “big easy” solution. Substance Use & Misuse. 2006;41(10−12):1637–1651. doi: 10.1080/10826080600848116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J.L., Walley A.Y., Bazzi A.R. Stuck in the window with you: HIV exposure prophylaxis in the highest risk people who inject drugs. Substance Abuse. 2019:1–3. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2019.1675118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]