To the Editor,

We read with great interest the well-written letter to the editor of Poerio et al. [1], who reported a case of COVID-19 pneumonia that presented on CT examination with the halo sign, reversed halo sign (RHS), and an atypical feature that they named the “double halo sign” (DHS). The authors characterized the DHS as an RHS surrounded by an additional peripheral ground-glass halo (identical to the “halo sign”), which gives these lesions a peculiar target-like appearance [1].

The halo sign and RHS are nonspecific tomographic signs that have been described in patients with several infectious and noninfectious diseases [2], and were recently reported in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia [3,4]. A recent study [3] showed that the RHS may present two different morphological appearances in patients with COVID-19 infection: the traditional RHS, defined as a focal rounded area of ground-glass opacity surrounded by a more or less complete ring of consolidation [4,5], and the reticular RHS, characterized by low attenuation areas inside the halo, with or without reticulation, suggestive of pulmonary infarction [6].

Other authors have reported the observation of a tomographic sign similar to the DHS described by Poerio et al. [1] in patients with COVID-19, characterized by peripheral ring-like opacities and a central nodular ground-glass opacity [7,8]. The authors named this sign the chest CT “target sign” and noted that the ring-like opacities are suggestive of an organizing pneumonia reaction pattern [6]. They also suggested that the central nodular opacity may reflect the presence of perivascular inflammation or may represent focal enlargement of the pulmonary artery. Despite its morphological distinctiveness, the target sign is often misinterpreted as the RHS [9].

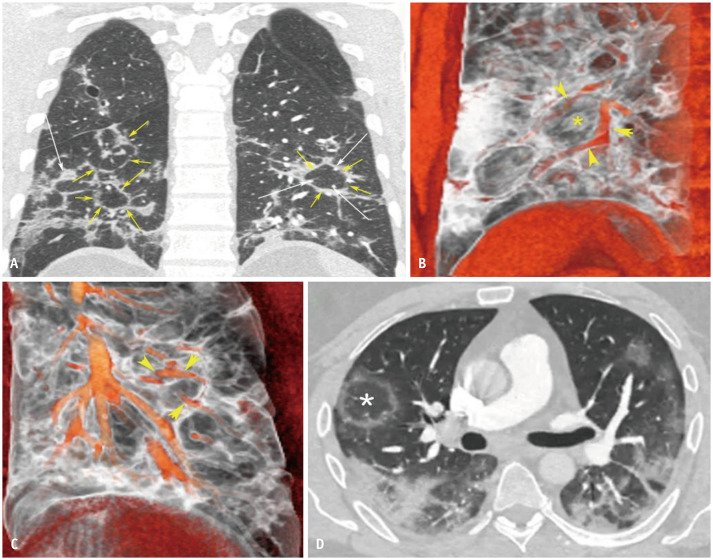

We retrospectively reviewed the chest CT studies of 34 adult patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, confirmed by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, who were examined in two tertiary hospitals in Brazil. Images were obtained in the late phase of the disease (> 12 days after symptom onset) [10]. RHS was observed in three (8.8%) patients, and the target sign was identified in four (11.8%) patients. Multiple target signs were observed in three of the latter patients, and a solitary sign was observed in one patient. In all the target sign cases, areas of consolidation and ground-glass opacity were also observed. In three of the four patients, the periphery of the target sign was complete and the sign had a polygonal instead of a more rounded or oval appearance (Fig. 1A), as commonly seen in the RHS. Regarding the central nodularity of the target sign, contrast-enhanced CT studies showed that the central region was composed of vessels in some cases, but had no relationship with vascular structures in others (Fig. 1B, C). In addition, the density was compatible with ground-glass opacity (ranging from −200 to −500 Hounsfield units).

Fig. 1. Target sign and reversed halo sign on chest CT in a COVID-19 patient.

A. Coronally reconstructed chest CT image showing bilateral areas of ground-glass opacity, most with a polygonal perilobular distribution (yellow arrows). The target sign is seen on the right lung, with central density (white arrows). Another polygonal perilobular opacity is seen on the left lung (yellow arrows), with vessels inside it (white arrows). B. 3D reconstruction of the target sign on the right lung showing the absence of vessels in the center (asterisk); the vessels have a peripheral course (arrowheads). C. 3D reconstruction of the polygonal opacity on the left lung, demonstrating the presence of vessels inside it (arrowheads). D. A reversed halo sign is seen in the right lung (asterisk). Note the rounded aspect of the lesion. 3D = three-dimensional

Detailed analysis of the peripheral wall of the target sign is more significant than the analysis of central nodular opacity. In patients with multiple adjacent target signs, the signs share external walls, creating a polygonal appearance. This pattern is not seen in patients with multiple RHSs, which generally have rounded or oval boundaries (Fig. 1D). The polygonal target sign structures are considered to represent the perilobular pattern, a characteristic finding of organizing pneumonia [11]. This pattern is characterized by thick, irregular polygonal or arcade-like opacities distributed mainly around the inner surface of the secondary pulmonary lobule. It was present in 57% of 21 patients with pathologically confirmed organizing pneumonia [11] and in 22.2% of 36 adult patients with organizing pneumonia studied by Faria et al. [12]. A recent pathological study demonstrated that patients in the late phase of COVID-19 pneumonia, especially critically ill patients who require mechanical ventilation, may develop secondary organizing pneumonia [13], as with other viral respiratory diseases, including influenza [14].

In conclusion, more important than the differentiation between the RHS, the target sign, and the DHS is the recognition of the signs' common etiopathogenesis; all the signs likely have the same significance and represent organizing pneumonia. This information is important because steroid use, although not routinely recommended in the early phase of COVID-19 pneumonia, might play a role in the late phase of the disease, when organizing pneumonia is suspected. Subsequent pathological studies may help confirm this suspicion, which could have important therapeutic implications.

References

- 1.Poerio A, Sartoni M, Lazzari G, Valli M, Morsiani M, Zompatori M. Halo, reversed halo, or both? Atypical computed tomography manifestations of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia: the “double halo sign”. Korean J Radiol. 2020;21:1161–1164. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2020.0687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godoy MC, Viswanathan C, Marchiori E, Truong MT, Benveniste MF, Rossi S, et al. The reversed halo sign: update and differential diagnosis. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:1226–1235. doi: 10.1259/bjr/54532316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchiori E, Nobre LF, Hochhegger B, Zanetti G. The reversed halo sign: considerations in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thromb Res. 2020;195:228–230. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sales AR, Casagrande EM, Hochhegger B, Zanetti G, Marchiori E. Reversed halo sign and COVID-19: possible histopathological mechanisms related to the appearance of this imaging finding. Arch Bronconeumol. 2020 Jul; doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2020.06.029. [Epub] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246:697–722. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2462070712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mançano AD, Rodrigues RS, Barreto MM, Zanetti G, Moraes TC, Marchiori E. Incidence and morphological characteristics of the reversed halo sign in patients with acute pulmonary embolism and pulmonary infarction undergoing computed tomography angiography of the pulmonary arteries. J Bras Pneumol. 2019;45:e20170438. doi: 10.1590/1806-3713/e20170438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Müller CIS, Müller NL. Chest CT target sign in a couple with COVID-19 pneumonia. Radiol Bras. 2020;53:252–254. doi: 10.1590/0100-3984.2020.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaghaghi S, Daskareh M, Irannejad M, Shaghaghi M, Kamel IR. Target-shaped combined halo and reversed-halo sign, an atypical chest CT finding in COVID-19. Clin Imaging. 2020;69:72–74. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Görkem SB, Çetin BS¸. COVID-19 pneumonia in a Turkish child presenting with abdominal complaints and reversed halo sign on thorax CT. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2020 Jun; doi: 10.5152/dir.2020.20361. [Epub] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson S, Kay FU, Abbara S, Bhalla S, Chung JH, Chung M, et al. Radiological Society of North America expert consensus statement on reporting chest CT findings related to COVID-19 endorsed by the Society of Thoracic Radiology, the American College of Radiology, and RSNA. J Thorac Imaging. 2020;35:219–227. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ujita M, Renzoni EA, Veeraraghavan S, Wells AU, Hansell DM. Organizing pneumonia: perilobular pattern at thin-section CT. Radiology. 2004;232:757–761. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2323031059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faria IM, Zanetti G, Barreto MM, Rodrigues RS, Araujo-Neto CA, Silva JL, et al. Organizing pneumonia: chest HRCT findings. J Bras Pneumol. 2015;41:231–237. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132015000004544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flikweert AW, Grootenboers MJJH, Yick DCY, du Mée AWF, van der Meer NJM, Rettig TCD, et al. Late histopathologic characteristics of critically ill COVID-19 patients: different phenotypes without evidence of invasive aspergillosis, a case series. J Crit Care. 2020;59:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchiori E, Zanetti G, Fontes CA, Santos ML, Valiante PM, Mano CM, et al. Influenza A (H1N1) virus-associated pneumonia: high-resolution computed tomography-pathologic correlation. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80:e500–e504. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]