Abstract

Approximately one-third of adults in the United States (U.S.) have limited health literacy. Those with limited health literacy often have difficultly navigating the health care environment, including navigating care across the cancer continuum (e.g., prevention, screening, diagnosis, treatment). Evidence-based interventions to assist adults with limited health literacy improve health outcomes; however, little is known about health literacy interventions in the context of cancer and their impact on cancer-specific health outcomes. The purpose of this review was to identify and characterize the literature on health literacy interventions across the cancer care continuum. Specifically, our aim was to review the strength of evidence, outcomes assessed, and intervention modalities within the existing literature reporting health literacy interventions in cancer. Our search yielded 1,036 records (prevention/screening n=174; diagnosis/treatment n=862). Following deduplication and review for inclusion criteria, we analyzed 87 records of intervention studies reporting health literacy outcomes, including 45 pilot studies (prevention/screening n=24; diagnosis/treatment n=21) and 42 randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental trials (prevention/screening n=31; diagnosis/treatment n=11). This literature included 36 unique interventions (prevention/screening n=28; diagnosis/treatment n=8), mostly in the formative stages of intervention development, with few assessments of evidence-based interventions. These gaps in the literature necessitate further research in the development and implementation of evidence-based health literacy interventions to improve cancer outcomes.

Keywords: Neoplasms, Cancer, Oncology, Health Literacy

Introduction

Cancer incidence and mortality inequities persist [1]. With almost 2 million new cancer cases diagnosed in the United States (U.S.) in 2019, cancer burden disproportionately impacts those with low socioeconomic status and racial/ethnic minorities [1–3]. Those who experience inequity in cancer incidence and outcomes are also those who are most at-risk for limited health literacy [1–4], defined as the collection of skills needed to navigate and function in the health care system [4, 5]. Over one-third of adults in the U.S. have limited health literacy [6]. Those with limited health literacy have difficultly navigating the health care environment, including accessing care across the cancer continuum (e.g., prevention, screening, diagnosis, treatment) [4]. Addressing the barriers experienced by those with limited health literacy across the cancer care continuum may improve outcomes; however, the strength of evidence for health literacy interventions is of mixed-quality [7].

Health literacy research has been dominated by observational studies examining the prevalence of limited health literacy and/or characterizing the relationship between health literacy and outcomes. In a review by Berkman et al., authors found 96 observational studies of good or fair quality reporting on investigations of health literacy (n=98), numeracy (n=22), or both (n=9)[4, 7]. These studies measured and compared health literacy of individuals and/or their caregivers to an outcome (e.g., health care access, use, cost) [4, 7]. This review found that across studies, limited health literacy was associated with lower health services use leading to poorer health outcomes; however, the authors highlighted the need for more rigorous research designs and adequately powered statistical analyses [4, 7]. Interventional studies employ strategies to ameliorate the health literacy demands placed on individuals. Sheridan and colleagues explored 38 studies outlining interventions designed specifically for those with limited health literacy, four of which included the cancer context [7, 8]. These studies were of good or fair quality (individual (n=22) or cluster (n=1) randomized controlled trials n=22, non-randomized controlled trials n=5, and quasi-experimental studies n=10). Although the strength of research was limited, authors reported promising evidence for discrete strategies to improve comprehension including appropriately ordering the presentation of essential information, using a consistent denominator, icon arrays, and video supports to verbal narration [7, 8]. Evidence for interventions using multiple strategies showed variable results and modest promise to improve use of health care services, health outcomes, and costs; however, none reported intervention effect on disparities [7, 8]. These reviews highlighted the mixed-quality evidence and early promise of interventions to address limited health literacy in the health care setting while highlighting the need for more rigorous methods and analyses.

The purpose of this systematic review was to identify and characterize the literature on health literacy interventions in cancer. Specifically, our aims were to review the representation of studies across the cancer care continuum, and report on the strength of evidence (study design), intervention types, outcomes assessed, and health literacy measurement within the existing literature reporting health literacy interventions in cancer.

Materials and Methods

The impetus for this review emanated from the Health Literacy and Communication Strategies in Oncology Workshop hosted by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine [9]. This review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol [10]. To describe the current literature, our review assessed, 1) What study designs are used? (strength of evidence); 2) What intervention types are employed?; 3) What domains along the cancer care continuum are targeted?; and, 4) What primary outcomes are utilized and what is the impact of interventions on these outcomes?

Data Sources and Selection

Given the large scope of topics in cancer, we searched all dates in PubMed for literature related to cancer prevention, screening, diagnostic processes, and treatment. Our PubMed search terms were Neoplasms OR Cancer OR Oncology AND Health Literacy. The search was run on July 7, 2019 with an updated search on August 21, 2019. Review articles were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools hosted at Boston University, CTSI 1UL1TR001430 [11].

We included studies that contained an intervention designed to improve some aspect of health literacy and were reported in English (see Table 1 for inclusion and exclusion criteria). Articles reporting the prevalence of health literacy in a population, or those that reported associations between health literacy and cancer outcomes were excluded.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Articles in the Review.

| Features | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Language | Reported in English | — |

| 2. Cancer Spectrum | Prevention, screening, diagnostic, treatment | — |

| 3. Intervention | Health literacy intervention | Interventions intended to increase clinical trial enrollment |

| 4. Research Methods | Randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental, pilot, intervention, feasibility | Protocol, cost analysis, process evaluation, non-intervention exploratory study, descriptive, review article, editorial/concept paper, measure development, intervention development with no evaluation or primary data |

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers searched and reviewed cancer prevention and screening (AJH) and diagnostic processes and treatment literature (CMG). These two reviewers identified articles reporting health literacy interventions. Research assistants extracted cancer care continuum information, study design, outcomes, and intervention descriptions from the identified articles. These abstractions were reviewed and verified by AJH and CMG.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We synthesized and analyzed the intervention studies using cancer care continuum target, study design, intervention types, and outcomes. Due to the varying health literacy measures and outcomes reported, we were not able to complete a meta-analysis.

Results

Study Selection

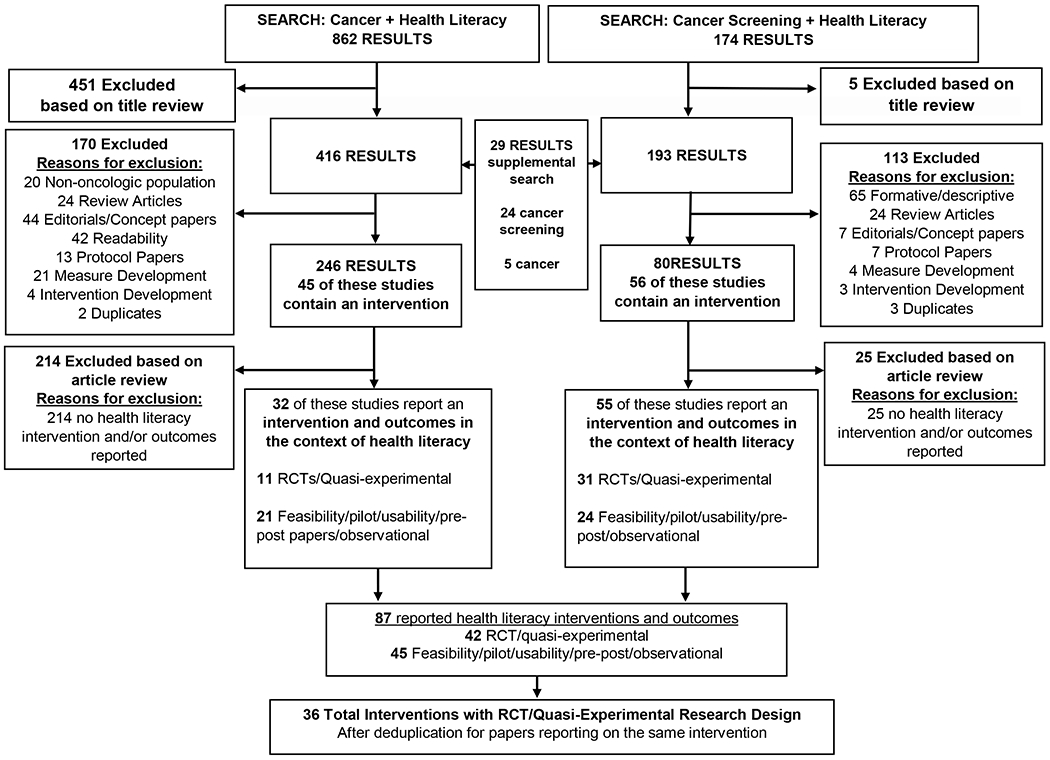

Our search yielded 1,036 records (prevention and screening n=174; diagnosis and treatment n=862; Figure 1). Twenty-nine records were added from an updated search in August 2019 and one record was added in 2020Following review for inclusion criteria and deduplication, 87 records were intervention studies reporting health literacy outcomes. Of these, 45 of the published interventions were pilot in nature (prevention/screening n=24; diagnosis/treatment n=21) and 42 were randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental trials (prevention/screening n=31; diagnosis/treatment n=11). Based on the reported randomized controlled trial or quasi-experimental investigations of health literacy interventions, a total of 36 unique interventions were included in our literature review (prevention/screening n=28; diagnosis/treatment n=8). The 36 interventions using randomized controlled or quasi-experimental study design underwent a detailed review (Table 2) [12–57].

Figure 1.

Literature search for cancer and health literacy

Table 2.

Interventions Evaluated using Randomized Controlled Trial/Quasi-Experimental Methods Included in Review.

| Author | Cancer type | Domain | Sample size | Brief Description | Primary Outcomes | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quasi-Experimental Design | ||||||

| Kushalnagar, 2018[12] | Breast cancer | Prevention | 74 | Computer-assisted text simplification for breast cancer information compared to original (unsimplified) text | Knowledge | (ns) Simplified messages μ=91.4 [SE=1.4] vs. original text condition μ=88.6 [SE=1.8], adjusting for HL |

| Davis, 2014[13] | Breast cancer | Screening | 1,181 | 3 study conditions: (1) Enhanced mammography care; (2) Enhanced care plus health-literacy informed education; (3) Enhanced care plus health-literacy informed education plus nurse support | Completion of Mammography (6 months; nurse-documented) | (ns) Education and enhanced care arm screening ratio=0.87, 95 % CI= 0.62,1.22, p = 0.42; (ns) Nurse and enhanced care screening ratio=1.19; 95 % CI=0.85, 1.65, p=0.31 |

| Love, 2012[14] | Cervical cancer | Screening | 498 | Entertainment-education video compared to print handouts among Southeast Asian women | Stage of Readiness to complete Pap Testing | (ns) Change in Stage of Readiness |

| Arnold, 2016[15]; Arnold, 2016[52]; Davis, 2014[51 ]; Davis, 2013[50] | Colorectal Cancer | Screening | 961 | 3 study conditions: (1) Enhanced care (screening recommendation and fecal occult blood testing kit mailed annually); (2) Enhanced care + education (health literacy-appropriate pamphlet and simplified testing instructions); (3) Enhanced care + education + nurse support | Completion of three FOBTs or positive FOBT with Colonoscopy | (ns) For all three nurse arm screening ratio=1.11; 95 % CI 0.76-1.62; p=0.59 |

| Randomized Between Subject Design | ||||||

| Meppelink, 2015[16] | Colorectal Cancer | Screening | 559 | Computer based evaluation of a two (illustrated vs. text-only) by two (non-difficult vs. difficult text) design | Recall (NPIQR), attitudes, intention to screen | (+) Recall for non-difficult text in low HL group vs. the difficult-high HL group; Illustrations added to difficult text for LHL group improved recall (8.49 to 10.88 for LHL vs. 13.25 to 14.77 for HHL illustration addition); (+) Effect of adding illustrations for attitude toward screening; (ns) Impact on intentions |

| Meppelink, 2015[17] | Colorectal Cancer | Screening | 231 | Computer based evaluation to assess spoken vs. written and animated vs. illustrated in a two by two design | Recall | (+) Spoken better recall: μ=13.6, but driven by LHL group (EM) vs. 11.97; (+) Animation has better recall only among LHL group compared with illustrations; (ns) Interaction between text and visual format modalities on recall |

| Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial Design | ||||||

| Smith, 2017[18] | Colorectal Cancer | Screening | 163,525 | Evaluated a standard information booklet compared to a booklet and gist information leaflet | Completed FOBT screen (18-weeks) | (ns) Overall screening uptake OR=1.02, 95% CI: 0.92, 1.13, p=0.77) |

| Han, 2017[19] | Breast and Cervical Cancer | Screening | 560 | Individually tailored cancerscreening brochure, community health worker health literacy training, and counseling among Korean American women versus usual care | Adherence to cancer screening guidelines (Mammography & Pap; self-report, 6-months) | (+) Mammography OR: 18.5, 95% CI=9.2, 37.4; (+) Pap OR: 13.3, 95% CI= 7.9, 22.3; (+) Both tests OR: 17.4, 95% CI= 7.5, 40.3 |

| Tong, 2017[20] | Colorectal Cancer | Screening | 329 | Evaluated colorectal cancer education over 3 months delivered by a lay health educator compared to education about nutrition and physical activity delivered by a health educator | CRC screening (ever and up to date at 6 months, self-report) | (+) Ever screen OR: 1.95, 95% CI: 1.4, 2.72; (+) Up to date OR: 1.73, 95% CI: 1.34, 2.21 |

| Epstein, 2017[53]; Duberstein, 2019[41] | All Cancer Types, Caregivers and Providers | Treatment | 303 [103] | Evaluated a communication training to improve communication among oncologists, patients, and caregivers at the end-of-life compared to control patients who received no training | Composite communication score | (+) Composite communication score (estimated adjusted intervention effect, 0.34; 95% CI: 0.06,0.62; p=0.02) |

| Price-Haywood, 2014[21]; Price-Haywood, 2010[22] | Colorectal, Breast, Cervical Cancer Screening and Providers | Screening | 168 [18] | Assessed communication training and web-based standardized patient audit and feedback compared to audit and feedback only | Standardized patients’ ratings of provider communication, patient knowledge, patient screening | (+) Standardized patient ratings of physician communication (6-month ratings 4.1 [1.1] vs. 3.1 [1.3]; p<0.05; 12-month ratings 4.1 [1.1] vs. 2.3 [0.8], p<0.05); (+ and ns) Mammography only (other cancer types); (ns) Patient knowledge of cancer screening guidelines |

| Randomized Controlled Trial Design | ||||||

| Ferreira, 2005[23]; Dolan, 2015[24] | Colorectal Cancer and Providers | Screening | 1,978 [503; 270] | Investigated a clinician communication training workshop intervention to improve colorectal cancer screening when compared to usual care | Rates of colorectal cancer screening recommendation by providers; rates of completion of colorectal cancer screening by patients | (+) Provider recommendation 76.0% vs. 69.4%; (+) Patients with limited health literacy completion intervention 55.7% vs. control 30.0% |

| Bodurtha, 2014[25] | Breast and Colorectal Cancer | Prevention | 490 | An interactive intervention to communicate cancer risk with family members compared to an informational handout | Family Communication (self-report) | (+) Gather information OR: 2.73, 95% CI: 2.01, 3.71; Communicate with family odds ratio: 1.85; 95% CI: 1.37, 2.48 |

| Kripalani, 2012[27] | Prostate cancer | Screening | 250 | Employed communication cueing to increase patient-provider prostate cancer screening discussions. This investigation compared: (1) a patient education handout, (2) cueing handout, (3) food pyramid (control) | Discussion of Prostate Cancer Within Visit | (+) Cue vs. Control OR: 2.39, 95% CI:1.26, 4.52; (+) Education vs. Control OR: 1.92, 95% CI: 1.01, 3.65 |

| Reuland, 2017[26] | Colorectal Cancer | Screening | 265 | A patient decision aid plus navigation with a trained health worker used to improve colorectal cancer screening compared to usual care | Completion of CRC Screening (6 months; HER review) | (+) 40% difference, 95% CI: 29%, 51%) |

| Gummersbach, 2015[29] | Breast cancer | Screening | 353 | Comparing a lower information leaflet to a greater information leaflet to assess willingness to complete mammography screening | Intention to screen | (ns) 7.1% difference (−0.9% −14.3%); (new leaflet [greater information] 81.5%, 95% CI: 75.8%, 87.2% vs. old leaflet [less information] 88.6%, 95% CI: 83.9%, 91.3%, p=0.060). |

| Horne, 2016[28] | Colorectal Cancer | Screening | 1220 | Comparing patient education to a patient education plus patient navigation intervention to improve up-to-date colorectal cancer screening | Completion of CRC Screening (self-report) | (+) OR 1.56, 95% CI: 1.08, 2.25 |

| Baker, 2014[31 ] | Colorectal Cancer | Screening | 450 | Usual care included computerized reminders, standing FIT orders, and clinician feedback. The intervention group also received a mailed reminder, a free FIT with low-literacy instructions, and a postage-paid return envelope; an automated telephone and text message reminding them that they were due for screening and that a FIT was being mailed to them; an automated telephone and text reminder 2 weeks later for those who did not return the FIT; and personal telephone outreach by a CRC screening navigator after 3 months. | Completion of FOBT (HER review; 6 months) | (+) 44.9% difference between groups; Intervention 82.2% vs. control 37.3%; p<0 .001 |

| Landrey, 2013[30] | Prostate Cancer | Screening | 303 | Assessed the impact of a mailed low-literacy informational flyer about the prostate cancer screening compared to usual care | Documented PSA Discussion, patient preference, and PSA testing (chart review) | (ns) For all chart review outcomes (flyer 62.5% vs. usual care 58.5%; p=0.48), shared decision making (documented patient-provider discussion, flyer 17.7% vs. usual care 13.6%; p=0.28), or knowledge (flyer 3.5/5 vs. usual care 3.3/5, p=0.60) over 12-months |

| Freed, 2013[33] | Colorectal Cancer | Screening | 60 | Evaluated the use of two texts: one with a low Flesh-Kincaid reading level and a control text | Recognition memory | (+) β=0.42 [0.17, 0.68] |

| Katz, 2012[32] | Colorectal Cancer | Screening | 270 | Assessed whether screening information, activating patients to ask for a screening test, and telephone barriers counseling improved colorectal cancer screening when compared to screening information | Completion of CRC screening (2 months; medical record review) | (+) OR: 2.35, 95% CI: 1.14, 5.56; p=0.020 |

| Fiscella, 2011[47]; Hendren, 2014[54] | Breast Cancer and Colorectal Cancer | Screening | 469 [366] | A multimodal intervention (e.g., tailored letters, personal phone calls, prompts) to improve cancer screening rates vs. standard of care | Completion of screening (mammography or CRC; 12 months, chart review) | (+) For both Mammography OR: 3.44 (95% CI: 1.91, 6.19) & CRC screening OR: 3.69 (95% CI: 1.93, 7.08) |

| Valdez, 2018[35] | Cervical Cancer | Screening | 943 | Assessed an interactive, one-time low-literacy cervical cancer education program through a multimedia kiosk in English or Spanish compared to usual care | Completion or Scheduling of Cervical Cancer Screening (defined as having had a Pap test or made an appointment in the interval between pre- and posttest; screening behavior) | (ns) Screening behavior OR: 1.14, 95% CI: 0.84, 1.55 |

| Miller, 2011[34] | Colorectal Cancer | Screening | 264 | Evaluated a web-based colorectal cancer screening decision aid compared to a control about prescription drug refills and safety | State a screening test preference; readiness to receive screening | (+) Test preference aOR: 5.3, 95% CI: 2.8, 10.1; Readiness aOR 4.7, 95% CI: 1.9, 11.9 |

| Volk, 2008[36] | Prostate Cancer | Screening | 450 | Investigated a prostate cancer entertainment education video designed for individuals with limited health literacy compared to an audiobooklet control | Knowledge | (+) Knowledge (magnitude unreported) |

| Smith, 2010[37]; Smith, 2014[55] | Colorectal Cancer | Screening | 572 [21] | Evaluated a colorectal cancer screening patient decision aid and video compared to standard information | Informed choice and preferences for involvement in the screening decision | (+) Knowledge decision aid arm=6.50, 95% CI: 6.15, 6.84; control group arm mean=4.10, 95% CI: 3.85, 4.36; p<0.001; (+) Informed choice 22% difference, 95% CI: 15%, 29%; p<0.001; (+) Preference for involvement in screening decision OR 2.47, 95% CI: 1.07, 5.69 |

| Davis, 2017[49] | Colorectal Cancer | Screening | 416 | Evaluated a multicomponent intervention incorporating a targeted health literacy enhanced photonovella compared to standard, non-targeted information | Screening with FIT within 180 days of delivery of the intervention | (ns) Screening uptake was 78.1% in the CARES condition and 83.5% in the comparison condition (p=0.17); FIT kit uptake, no difference was observed between the conditions (p=0.32). |

| Meade, 1994[48] | Colorectal Cancer | Screening | 1,100 | Assessed a video intervention compared to a booklet to improve knowledge of colorectal cancer screening | Knowledge, recall | (+) Booklet mean score difference 1.7; video mean score difference 1.9; control mean score difference 0.2; p<0.05. No statistically significant difference was noted between the booklet and videotape groups. |

| Visser, 2019[39] | All Cancer Types | Treatment | 217 | Investigated the effects of oncologists’ training and utilization of: (1) emotion-oriented speech, (2) emotion-oriented silence, and (3) standard communication | Investigate and compare the effects of oncologists’ emotion-oriented speech and emotion-oriented silence on information recall (free recall and recognition) | (ns) Free recall (F(2, 201)=0.64, p=0.529, effect size partial η2=.01); (+) Recognition (F(2, 201)=0.64, p=0.529, effect size partial η2=.05); (+) Emotion oriented recognition; (ns) Emotional stress mediator; (ns) Health literacy moderator (p=0.136, R2= .041); |

| Jibaja-Weiss, 2011[40] | Breast Cancer | Treatment | 76 | Evaluated an entertainment education intervention designed to improve clarity and knowledge of breast cancer treatment surgical options when compared to usual care | Treatment preference, knowledge, satisfaction with decision, satisfaction with decision-making process, decisional conflict | (−) Breast conserving surgery (40.5% vs. 50.0%); (+) radical mastectomy (59.5% vs. 39.5%,p=0.018); (+) Knowledge; (ns) Satisfaction; (mixed) decisional conflict [(+) surgical options and personal values; (ns) uncertainty; (ns) social support] |

| Dyer, 2019[42] | Breast Cancer | Treatment | 64 | Investigated a physician-communicated detailed radiation therapy plan, including a visualization, of the patient radiation therapy plan compared to a nondetailed review | Patient Reported Outcomes; Quality of Life (FACIT-TS-PS) | (ns) Patient Reported Outcomes; Quality of Life (p=0.63, .53, 0.52, and 0.71) |

| Heckel, 2018[43] | All Cancer Types, Caregivers and Providers | Treatment | 216 | Evaluated a cancer patient and caregivers telephone outcall program compared to an attention control group to address caregiver burden | Self-reported caregiver burden | (ns) Caregiver burden (p=0.921) |

| Keohane, 2017[44] | Breast cancer | Prevention | 84 | Evaluated an application to improve risk perception when compared to standard risk counseling among patients attending a high risk breast clinic | Risk perception | (+) Increased risk accuracy (Control group increase from 21% to 48% vs Treatment group increase from 33% to 71%; p=0.003); (ns) Risk perception (<30% difference between groups) |

| Kusnoor, 2016[45]; Giuse, 2016[56] | Melanoma , lung, and Renal Cancer and Caregivers | Treatment | 107 [90] | Assessed an intervention to improve knowledge by translating web-based cancer genomic information into videos compared to professional-level content | Knowledge; knowledge retention | (+) Knowledge [easy to understand (p=0.01), was confusing (p=0.014), and if they were satisfied with the information (p=0.03)] |

| Chambers, 2014[46] | All Cancer Types and Caregivers | Treatment | 690 | Assessed a single session of a nurse-led self-management intervention compared to a five-session psychologist cognitive behavioral intervention delivered by telephone | Psychological and cancer-specific distress and post-traumatic growth | (ns) Distress and post-traumatic growth [distress decreased over time in both arms with small to large effect sizes (Cohen’s ds = 0.05-0.82). Post-traumatic growth increased overtime for all participants (Cohen’s ds = 0.6-0.64)] |

| Hoffman, 2016[57] | Colorectal Cancer | Prevention | 89 | Assessed a patient decision aid video containing culturally tailored information about colorectal cancer screening options in an entertainment education format compared to an attention control video about hypertension | Decision making, knowledge, colorectal cancer screening behavior | (+) Knowledge (intervention mean increase 2.7 vs. control mean increase 0.4, p< .01); lower (improved) decisional conflict (intervention mean 11.0 vs. control mean 39.6; p< .01); (ns) Screening completion (1-3 weeks; 3 months) |

Primary Outcomes

Our aim was to report the primary outcomes for which studies were powered to detect differences; however, many investigations included secondary outcomes that are not described here.

Screening Completion

Short-Term Screening Completion (<6 Months)

Screening outcomes were the most prevalent primary outcome, although studies ranged in the time allotted to detect a difference in screening outcomes. Three colorectal cancer screening interventions investigated short term screening completion (within 6 months of the intervention) and found mixed results. Katz et al.’s patient activation intervention improved colorectal cancer screening at 2 months when compared to an information-only arm [32]. Smith et al.’s primary outcome was the return of the guaiac-based Fecal Occult Blood Testing (gFOBT) within 18 weeks of the invitation and found no difference between a standard information booklet compared to a booklet and “gist” information (e.g., the general meaning of the information) [18]. Hoffman et al. did not find improved colorectal cancer screening intentions or completion at 3 months when assessing an entertainment education intervention [57].

Mid-Range Screening Completion (6-18 Months)

Six interventions found improved completion of colorectal cancer screening within 6 to18-months of the intervention [20, 23, 24, 26, 28, 31,47, 54]. Davis et al. used a photonovella and showed no difference in mid-range screening rates between intervention and control groups receiving non-targeted information [49].

Three interventions investigated breast cancer screening completion over this period. Davis and colleagues measured completion of breast cancer screening over 6-months and found no significant difference for mammogram completion [13], while Han et al. demonstrated improvements in mammography over the same period [19]. Fiscella et al.’s multimodal intervention also assessed breast cancer screening and found improved mammography at 12 months [47, 54].

Two interventions examined cervical cancer screening completion. Han et al. also assessed cervical cancer screening and demonstrated significant increases in Pap testing at 6 months [19], while Valdez and colleagues found that multimedia low-literacy cervical cancer education did not improve cervical cancer screening rates over 12-months [35].

Landrey et al., assessed the impact of a mailed low-literacy informational flyer about the prostate cancer screening and found no difference in screening tests ordered over 12-months [30].

Longer-Term Screening Completion (>18 Months)

Two interventions investigated longer-term cancer screening outcomes (2-3 years) and found that their initial promising results were not maintained at the end of the investigation time period. Price-Haywood et al. found that by 24-months, their continuing medical education training intervention did not increase colorectal or cervical cancer screening, but did improve mammography screening [21, 22]. Arnold et al., evaluated completion and return of three fecal occult blood tests (FOBTs) over three years and found that screening was not sustained over all three years [15, 50–52].

Knowledge

Three studies [12, 36, 57] observed improved knowledge, while two others [45, 48, 56] reported modest differences with limited significance. Kushalnagar et al. found that Deaf and hearing college students’ breast cancer knowledge both increased following simplified messages [12]. Volk and colleagues evaluated both prostate and colorectal[57] cancer entertainment education videos. Both significantly improved knowledge. The colorectal cancer intervention reduced decisional conflict for all participants, while the prostate cancer did so among those with limited health literacy[36]. Meade et al. found modest benefits for using a video intervention compared to a booklet to improve knowledge of colorectal cancer screening [48]. Kusnoor et al.’s video intervention showed significantly greater improvement in knowledge scores when compared to the control group; although differences in knowledge scores dissipated by the three week follow-up test [45, 56].

Recall and Recognition Memory

Three interventions investigated recall and recognition memory in relation to colon cancer screening tests. Meppelink et al. found increased recall for non-difficult text in the limited health literacy group vs. the difficult-high adequate health literacy group [16]. Moreover, illustrations added to difficult text improved recall for the limited health literacy group [16]. A second Meppelink et al. study assessed spoken vs. written and animated vs. illustrated information in a two by two design and reported better recall for spoken condition driven by the limited health literacy group [17]. Animation had better recall only among the limited health literacy group compared with illustrations and there was not a significant interaction between text and visual format modalities on recall [17]. Freed et al. evaluated low Flesh-Kincaid reading level versus a control text and reported that the lower reading level text improved recognition memory across health literacy levels [33].

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Two investigations focused on choice and decision making and reported improved outcomes. Smith and colleagues found that a patient decision aid improved informed choice about colorectal cancer screening and video improved knowledge more than usual care [37, 55]. Moreover, those in the decision aid groups were more likely to identify their preferred involvement in screening decisions [37, 55]. Jibaja-Weiss et al. reported a breast cancer entertainment education intervention improved clarity, knowledge of surgical options, and surgical preferences when compared to usual care [40].

Keohane et al., used an application to improve risk perception among patients attending a high risk breast clinic [44]. Increases in 10-year personal risk accuracy were observed in the intervention group relative to the control [44].

Dyer and colleagues found no impact on patient satisfaction when they investigated a physician-communicated detailed radiation therapy plan [42].

Three investigations reported on participants’ readiness or willingness to pursue cancer screening. Love et al examined video and print brochure materials and found no significance differences in readiness, knowledge, and attitudes toward Pap testing between groups [14]. Miller et al. evaluated a web-based colorectal cancer screening decision aid and found that the decision-aid helped to increase readiness and identify a screening preference [34]. Gummersbach et al., found that a leaflet about mammography with improved information relevant to decision-making did not differ from the old leaflet in terms of willingness to complete mammography screening [29].

Communication

Four papers reported the impact of their intervention on communication outcomes. Three of the interventions targeted patient-physician communication, demonstrating improvements in communication related to prostate cancer discussions [27], participant information recognition [39], and patient-physician communication scores [41, 53]. Similarly, Bodurtha et al. found that an interactive intervention was more successful at promoting cancer communication amongst families when compared to a print handout [25].

Caregiver Burden and Psychological Distress

Two papers reported the impact of caregiver interventions. Heckel et al., recruited cancer patient and caregivers to a telephone program and found that it had no impact on caregiver burden, but did reduce caregiver unmet needs at one month post-intervention [43]. Chambers and colleagues explored a self-management intervention for patient and caregiver dyads [46]. For those with limited health literacy, only the psychologist intervention reduced distress while amongst those with higher education, distress decreased in both intervention arms (nurse and psychologist-led interventions) [46].

Health Literacy Measurement

The following section describes the measurement and use of health literacy related outcomes reported by the manuscripts included in our review.

Heath Literacy as an Outcome

Two interventions reported improvements to health literacy. Han et al. reported a secondary outcome of health literacy as measured by the Assessment of Health Literacy in Cancer Screening (AHL-C; scores range from 0-52). Women in the intervention group had a mean increase of 7.0 points in their health literacy score (95% CI=4.9, 9.0) [19]. Heckel et al. used improvement in the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) as a secondary outcome to measure intervention effectiveness. They reported improvement in one specific skill that contributes to health literacy: among caregivers at increased risk for depression, the intervention significantly improved having health information scores (p=0.040) [43]. Their post hoc analyses revealed an improvement in caregiver confidence of having sufficient health information (HLQ Scale 2; baseline and 6-months, p=0.002 and 1-month and 6-months p=0.009) in the intervention group but not in the control group (p> 0.30) [43].

Health Literacy Effect Modification

Three interventions observed improved outcomes for those with limited health literacy. In a clinician communication training intervention to improve colorectal cancer screening, Ferreria and colleagues used the REALM to identify those with limited health literacy and reported that among patients with limited health literacy, those in the intervention arm had higher rates of screening when compared with those in the control arm (intervention 55.7% vs. control 30.0%, p<0.01) [23, 24]. Meppelink and colleagues examined use of various information presentations to assess knowledge, attitudes, literacy and intentions for those with limited health literacy using the SAHL-D [16, 17]. In both investigations, they reported a health literacy effect modification. In the first investigation, Meppelink et al. found increased recall for non-difficult text in the limited health literacy group vs. the difficult-high adequate health literacy group [16]. Moreover, illustrations added to difficult text for limited health literacy group improved recall (limited health literacy 8.49 to 10.88 vs. adequate health literacy 13.25 to 14.77) [16]. The second Meppelink et al. assessed spoken vs. written and animated vs. illustrated in a two by two design [17]. Meppelink et al. reported better recall for spoken condition driven by limited health literacy (μ=13.6; limited health literacy group 11.97). Animation led to better recall only among the limited health literacy group compared with illustrations and there was not a significant interaction between text and visual format modalities on recall [17].

Three interventions reported improvements for those with adequate health literacy. Horne et al., assessed health literacy with the REALM-R and found an effect on colorectal cancer screening for those with adequate health literacy (OR 2.17, 95 % CI 1.03–4.56), but not for those with limited health literacy [28]. Bodurtha et al. used the Rapid Estimate of Health Literacy in Genetics (REAL-G) and reported that genetic literacy modified the intervention effect (coefficient term:−0.77; 95% CI:−1.62, 0.08). Thus, those with adequate genetic health literacy in the intervention group reported greater family information gathering (REAL-G score >3 odds ratio 3.02 95% CI: 2.16, 4.21) [25]. Visser et al. used a validated Dutch measure of functional and communicative health literacy. They found that the impact of communication on information recall was moderated by functional health literacy (variance 7.3%., p=0.010, R2=0.073) [39]. The standardized estimates indicate that poorer functional health literacy predicted poorer recognition of information in the standard communication condition [39]. Communicative health literacy did not moderate the effects on free recall or recognition of information [39].

Discussion

We reviewed interventions designed to address health literacy in the context of cancer prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. The majority of published interventions were in the formative stages of development and few were testing evidence-based interventions. All interventions were focused on adults and less than half included a clinician component in the intervention. Behavior-oriented outcomes were the primary focus of outcome measures, which included screening intention and completion. Knowledge, comprehension, and recall were the second most common outcomes and a variety of standardized and exploratory measures were used to capture these data.

While all the studies included in this review were in the context of health literacy and cancer, none of the investigations improved health literacy as a primary outcome. Han et al. provided health literacy skills training and reported an increase in their participants’ health literacy scores [19] and Heckel et al. reported a secondary outcome of significantly improved health literacy measurement scores related to having health information, a specific health literacy skill [43]. These findings build upon a prior review outlining the limited scope of health literacy outcomes in cancer research [58]. Moreover, investigations evaluating the role of health literacy, demonstrated mixed results. Improvements among those with adequate health literacy were often in contrast to the stated purpose of addressing the needs of those with limited health literacy. Interventions that improve outcomes only for those with adequate health literacy run the risk of exacerbating disparities in outcomes.

Multilevel interventions appeared to have the greatest impact on outcomes. These multilevel interventions included clinician communication training, navigation supports, patient education and activation, and caregiver/family support. These findings support the existing literature describing use of multiple strategies in health literacy interventions since health literacy is a constellation of skills and demands [7, 8]. The skills associated with health literacy (e.g., numeracy, listening, speaking, reading) interact with system-level demands (e.g., health insurance complexity, navigation skills, perceived barriers) and may benefit from a multilevel intervention approach. Multilevel interventions can address several factors, such as access and utilization of health care (e.g., navigation, complexity), provider-patient interaction (e.g., communication, knowledge), and self-care (e.g., motivation, self-efficacy) [59]. Study designs that incorporate both interventions and evaluation at multiple levels of influence, and how these interact to produce health outcomes for populations with limited health literacy, would help advance this line of research [60].

The use of health literacy in multivariate analyses is an underdeveloped area of the literature. Only six interventions observed an effect modification by health literacy level. Three interventions observed improved outcomes for those with limited health literacy [16, 17, 23, 24] and three reported improvements for those with adequate health literacy [25, 28, 39]. Other studies incorporated health literacy level in their study inception and design but results and analyses appeared to be incomplete or insufficiently powered to fully evaluate effects across health literacy levels. Opportunities to use more rigorous analyses to assess the effect of health literacy level are critically needed to develop the health literacy field.

Many of the articles reviewed for this investigation reported on the phases of development of a single intervention. The formative work and feasibility testing that is needed to develop an evidence-based intervention is formidable. Furthermore, interventions developed for specific populations require intensive foundational work to ensure implementation of the intervention in the future. Yet, few interventions included implementation measures (e.g., fidelity, cost, sustainability) [61]. These critical implementation measures can facilitate translation of interventions into a variety of real-world settings. Thus, the inclusion of implementation science measures may advance the field and enhance intervention scalability.

Limitations

This review is not without limitations. Only interventions reported in English were included. Increasing the scope to include investigations in multiple languages would enhance these findings. Standardized measures were not used across studies and therefore we were unable to complete a meta-analysis of the outcomes. The proliferation of context specific health literacy measures has contributed to the use of a wide variety of measures [62]. Including standardized outcome measures may help to synthesize results in future investigations.

Conclusion

Most published studies were in the formative stages of intervention development and few were testing an evidence-based intervention. Designing research investigations that are powered to evaluate multilevel interventions and include explicit evaluations of health literacy impacts would advance the field. Attention to improving health literacy specific skills among those with limited health literacy should be a central focus of intervention development in order to avoid contributing to disparities.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank the speakers and participants for their contributions to The National Cancer Policy Forum’s workshop Health Literacy and Communication Strategies in Oncology.

Funding: The National Cancer Policy Forum’s workshop Health Literacy and Communication Strategies in Oncology was supported by its sponsoring members, which currently include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the NIH/National Cancer Institute, the American Association for Cancer Research, the American Cancer Society, the American College of Radiology, American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the Association of American Cancer Institutes, Association of Community Cancer Centers, Bristol-Myers Squibb, the Cancer Support Community, the CEO Roundtable on Cancer, Flatiron Health, Merck, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Novartis Oncology, the Oncology Nursing Society, Pfizer and the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

This publication was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, through BU-CTSI Grant Number 1UL1TR001430; the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (PI: AJH, R00MD011485) and the National Cancer Institute (PI: CMG,1K07CA221899). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests: Authors have no conflicts of interest to report at this time.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2019;69(1):7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polite BN, Adams-Campbell LL, Brawley OW, et al. Charting the Future of Cancer Health Disparities Research: A Position Statement from the American Association for Cancer Research, the American Cancer Society, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the National Cancer Institute. Cancer Research. 2017;77(17):4548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer Disparities by Race/Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2004;54(2):78–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low Health Literacy and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;155(2):97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kutner M , Jin E , Paulsen C . The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006-483). National Center for Education. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Education; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkman ND, Sheridan MSL, Donahue KE, et al. Health Literacy Interventions and Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review of the Literature. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment no 199 (Prepared by RTI International–University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center under contract 290-2007-10056-I) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheridan SL, Halpern DJ, Viera AJ, Berkman ND, Donahue KE, Crotty K. Interventions for Individuals with Low Health Literacy: A Systematic Review. Journal of Health Communication. 2011;16(sup3):30–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Health Literacy and Communication Strategies in Oncology: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLOS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) - A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009;42(2):377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kushalnagar P, Smith S, Hopper M, Ryan C, Rinkevich M, Kushalnagar R. Making Cancer Health Text on the Internet Easier to Read for Deaf People Who Use American Sign Language. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33(1):134–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis TC, Rademaker A, Bennett CL, et al. Improving mammography screening among the medically underserved. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(4):628–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Love GD, Tanjasiri SP. Using entertainment-education to promote cervical cancer screening in Thai women. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27(3):585–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnold CL, Rademaker A, Wolf MS, et al. Final Results of a 3-Year Literacy-Informed Intervention to Promote Annual Fecal Occult Blood Test Screening. J Community Health. 2016;41(4):724–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meppelink CS, Smit EG, Buurman BM, van Weert JCM. Should We Be Afraid of Simple Messages? The Effects of Text Difficulty and Illustrations in People With Low or High Health Literacy. Health communication. 2015;30(12):1181–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meppelink CS, van Weert JCM, Haven CJ, Smit EG. The effectiveness of health animations in audiences with different health literacy levels: an experimental study. Journal of medical internet research. 2015;17(1):e11–e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith SG, Wardle J, Atkin W, et al. Reducing the Socioeconomic Gradient in uptake of the NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme Using a Simplified Supplementary Information Leaflet: A Cluster-Randomised Trial. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han HR, Song Y, Kim M, et al. Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Literacy Among Korean American Women: A Community Health Worker-Led Intervention. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(1):159–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong EK, Nguyen TT, Lo P, et al. Lay Health Educators Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening among Hmong Americans: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer. 2017;123(1):98–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price-Haywood EG, Harden-Barrios J, Cooper LA. Comparative effectiveness of audit-feedback versus additional physician communication training to improve cancer screening for patients with limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(8):1113–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Price-Haywood EG, Roth KG, Shelby K, Cooper LA. Cancer risk communication with low health literacy patients: a continuing medical education program. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25 Suppl 2:S126–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferreira MR, Dolan NC, Fitzgibbon ML, et al. Health care provider-directed intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening among veterans: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(7):1548–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dolan NC, Ramirez-Zohfeld V, Rademaker AW, et al. The Effectiveness of a Physician-Only and Physician-Patient Intervention on Colorectal Cancer Screening Discussions Between Providers and African American and Latino Patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1780–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bodurtha JN, McClish D, Gyure M, et al. The KinFact intervention - a randomized controlled trial to increase family communication about cancer history. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(10):806–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reuland DS, Brenner AT, Hoffman R, et al. Effect of Combined Patient Decision Aid and Patient Navigation vs Usual Care for Colorectal Cancer Screening in a Vulnerable Patient Population: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):967–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kripalani S, Sharma J, Justice E, et al. Low-Literacy Interventions to Promote Discussion of Prostate Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33(2):83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horne HN, Phelan-Emrick DF, Pollack CE, et al. Effect of patient navigation on colorectal cancer screening in a community-based randomized controlled trial of urban African American adults. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26(2):239–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gummersbach E, in der Schmitten J, Mortsiefer A, Abholz HH, Wegscheider K, Pentzek M. Willingness to participate in mammography screening: a randomized controlled questionnaire study of responses to two patient information leaflets with different factual content. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112(5):61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landrey AR, Matlock DD, Andrews L, Bronsert M, Denberg T. Shared decision making in prostate-specific antigen testing: the effect of a mailed patient flyer prior to an annual exam. J Prim Care Community Health. 2013;4(1):67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker DW, Brown T, Buchanan DR, et al. Comparative effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention to improve adherence to annual colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1235–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katz ML, Fisher JL, Fleming K, Paskett ED. Patient activation increases colorectal cancer screening rates: a randomized trial among low-income minority patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(1):45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freed E, Long D, Rodriguez T, Franks P, Kravitz RL, Jerant A. The effects of two health information texts on patient recognition memory: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(2):260–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller DP, Spangler JG, Case LD, Goff DC, Singh S, Pignone MP. Effectiveness of a Web-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening Patient Decision Aid: A Randomized Controlled Trial in a Mixed-Literacy Population. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;40(6):608–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valdez A, Napoles AM, Stewart SL, Garza A. A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Cervical Cancer Education Intervention for Latinas Delivered Through Interactive, Multimedia Kiosks. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33(1):222–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Volk RJ, Jibaja-Weiss ML, Hawley ST, et al. Entertainment Education for Prostate Cancer Screening: A Randomized Trial among Primary Care Patients with Low Health Literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(3):482–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith Sk , Trevena L, Simpson JM, Barratt A, Nutbeam D, McCaffery KJ. A Decision Aid to Support Informed Choices about Bowel Cancer Screening among Adults with Low Education: Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c5370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyatt A, Lipson-Smith R, Gough K, et al. Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Oncology Patients’ Perspectives of Consultation Audio-Recordings and Question Prompt Lists. Psychooncology. 2018;27(9):2180–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Visser LNC, Tollenaar MS, van Doornen LJP, de Haes H, Smets EMA. Does Silence speak louder than words? The impact of oncologists’ emotion-oriented communication on analogue patients’ information recall and emotional stress. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(1):43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jibaja-Weiss ML, Volk RJ, Granchi TS, et al. Entertainment Education for Breast Cancer Surgery Decisions: A Randomized Trial among Patients with Low Health Literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(1):41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duberstein PR, Maciejewski PK, Epstein RM, et al. Effects of the Values and Options in Cancer Care Communication Intervention on Personal Caregiver Experiences of Cancer Care and Bereavement Outcomes. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(11):1394–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dyer BA, Li CS, Daly ME, Monjazeb AM, Mayadev JS. Prospective, Randomized Control Trial Investigating the Impact of a Physician-Communicated Radiation Therapy Plan Review on Breast Cancer Patient-Reported Satisfaction. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2019;9(6):e487–e496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heckel L, Fennell KM, Reynolds J, et al. Efficacy of a telephone outcall program to reduce caregiver burden among caregivers of cancer patients [PROTECT]: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keohane D, Lehane E, Rutherford E, et al. Can an educational application increase risk perception accuracy amongst patients attending a high-risk breast cancer clinic? Breast. 2017;32:192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kusnoor SV, Koonce TY, Levy MA, et al. My Cancer Genome: Evaluating an Educational Model to Introduce Patients and Caregivers to Precision Medicine Information. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc. 2016;2016:112–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chambers SK, Girgis A, Occhipinti S, et al. A Randomized Trial Comparing Two Low-Intensity Psychological Interventions for Distressed Patients With Cancer and Their Caregivers. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2014;41(4):E256–E266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fiscella K, Humiston S, Hendren S, et al. A multimodal intervention to promote mammography and colorectal cancer screening in a safety-net practice. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2011;103(8):762–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meade CD, McKinney WP, Barnas GP. Educating patients with limited literacy skills: the effectiveness of printed and videotaped materials about colon cancer. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(1):119–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davis SN, Christy SM, Chavarria EA, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a multicomponent, targeted, low-literacy educational intervention compared with a nontargeted intervention to boost colorectal cancer screening with fecal immunochemical testing in community clinics. Cancer. 2017;123(8):1390–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis T, Arnold C, Rademaker A, et al. Improving colon cancer screening in community clinics. Cancer. 2013;119(21):3879–3886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davis TC, Arnold CL, Bennett CL, et al. Strategies to improve repeat fecal occult blood testing cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(1):134–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arnold CL, Rademaker A, Wolf MS, Liu D, Hancock J, Davis TC. Third Annual Fecal Occult Blood Testing in Community Health Clinics. Am J Health Behav. 2016;40(3):302–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Fenton JJ, et al. Effect of a Patient-Centered Communication Intervention on Oncologist-Patient Communication, Quality of Life, and Health Care Utilization in Advanced Cancer: The VOICE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncology. 2017;3(1):92–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hendren S, Winters P, Humiston S, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of a multimodal intervention to improve cancer screening rates in a safety-net primary care practice. Journal of general internal medicine. 2014;29(1):41–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith SK, Kearney P, Trevena L, Barratt A, Nutbeam D, McCaffery KJ. Informed choice in bowel cancer screening: a qualitative study to explore how adults with lower education use decision aids. Health expectations: an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy. 2014;17(4):511–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Giuse NB, Kusnoor SV, Koonce TY, et al. Guiding Oncology Patients Through the Maze of Precision Medicine. J Health Commun. 2016;21 Suppl 1:5–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoffman AS, Lowenstein LM, Kamath GR, et al. An Entertainment-Education Colorectal Cancer Screening Decision Aid for African American Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer. 2017;123(8):1401–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fernández-González L, Bravo-Valenzuela P. Effective Interventions to Improve the Health Literacy of Cancer Patients. Ecancermedicalscience. 2019;13:966–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taplin SH, Anhang Price R, Edwards HM, et al. Introduction: Understanding and Influencing Multilevel Factors Across the Cancer Care Continuum. JNCI Monographs. 2012;2012(44):2–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011. ;38(2):65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haun JN, Valerio MA, McCormack LA, Sørensen K, Paasche-Orlow MK. Health Literacy Measurement: An Inventory and Descriptive Summary of 51 Instruments. Journal of Health Communication. 2014;19(sup2):302–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]