Abstract

Background:

Organoids are excellent three-dimensional in vitro models of gastrointestinal cancers. However, patient derived organoids (PDOs) remain inconsistent and unreliable for rapid actionable drug sensitivity testing due to size variation and limited material.

Methods:

On day10/passage2 after standard creation of organoids, ½ PDOs were dissociated into single-cells with TrypLE™ Express Enzyme/DNase I and mechanical dissociation; and ½ PDOs were expanded by standard technique. H&E and IHC with CK7 and CK20 were performed for characterization. Drug sensitivity testing was completed for single-cells and paired standard PDOs to assess reproducibility.

Results:

After 2-3 days >50% of single cells reformed uniform miniature PDOs (~50 μm). We developed 10 PDO single-cell lines (N=4, gastric cancer, GC; and N=6, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, PDAC), which formed epithelialized cystic structures and by IHC exhibited CK7(high)/CK20(low) expression patterns mirroring parent tissues. Compared to paired standard PDOs, single-cells (N=2, PDAC; N=2, GC) showed similar architecture, albeit smaller and more uniform. Importantly, single-cells demonstrated similar sensitivity to cytotoxic drugs to matched PDOs.

Conclusions:

PDO single-cells are accurate for rapid clinical drug testing in gastrointestinal cancers. Utilizing early passage PDO single-cells facilitates high-volume drug testing, decreasing time from tumor sampling to actionable clinical decisions and provides a personalized medicine platform to optimally select drugs for gastrointestinal cancer patients.

Precis

Organoid-derived single cells are accurate for rapid clinical drug testing in gastrointestinal cancer. Using early passage patient-derived organoid single-cells facilitates high-volume drug testing, decreasing time from tumor sampling to actionable clinical decisions and providing a personalized medicine platform to optimally select drugs for gastrointestinal cancer patients.

INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancers were the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the US in 2019. In particular, pancreatic and gastric cancers are of great concern given that 5-year survival rates remain low[1]. Accordingly, the development of novel therapeutic strategies to improve outcomes for patients with GI cancers is imperative. With the advent of next generation sequencing (NGS) techniques, genomic profiling has been increasingly used to identify individualized and targeted drugs for patients, but this approach has been limited by the low percentage of actionable genetic alterations detected[2, 3]. Additionally, recent pharmacogenomic studies have generated a wealth of data to correlate clinical drug responses with genomic profiling and molecular characterization of cancer cells. However, this approach remains inexact and premature for clinical decision making[4, 5].

Current methods to test and predict clinical activity of cytotoxic drugs have involved two-dimensional (2D) cell culture systems or patient derived xenografts (PDXs). The 2D cell cultures are unable to accurately recapitulate tumor heterogeneity and the tumor microenvironment (TME), whereas PDXs retain such capacities but are costly and time-consuming. These limitations make both methods largely inefficient for clinical decision making applications[6-8]. Here, we aimed to develop a personalized medicine platform to enable drug selection for patients with GI cancers. Our previous publications support the use of patient-derived organoids (PDOs), which are in vitro models that accurately represent the primary tumor and serve as an effective vehicle for determining the best therapy for patients with GI cancers[7-10].

PDOs have been successfully established for various GI cancers including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and gastric cancer (GC) and show promise as powerful tools to study developmental processes and test drug sensitivities[11-17]. However, using PDOs for personalized medicine remains suboptimal given the time frame required to develop sufficient quantities of PDOs from minute tissue biopsies. At present, PDO development and drug sensitivity testing from small biopsy samples requires >3-4 weeks, which precludes timely clinical decision making. Additionally, PDO size and growth rates are variable, introducing inconsistency and limiting reproducibility when performing drug sensitivity testing. Alternative methods have been proposed to manually count PDOs or to apply filters to establish size consistency[18, 19]. These approaches, however, remain suboptimal as they do not solve the need to rapidly generate larger quantities of PDOs for timely drug testing.

PDO lines that have their 3D architecture chemically or mechanically disrupted are known as single-cells, which comprise different cell types including stem cells and other niche cells of the primary tissue[20-24]. After PDO conformational disruption, the process of growing these PDO single-cells results in consistency in the rates of growth and uniformity in the distribution of sizes. Here, we report the development and testing of PDO single-cells that recapitulate the parent PDO lines from PDAC and GC patients. We followed the growth of PDO single-cells into mature PDOs, and identified the optimal time point for using these single-cells for drug testing. Our goal was to develop PDO single-cells from GI cancer biopsy specimens and generate adequate biologic material for drug sensitivity testing within a clinically actionable time frame for personalized medicine applications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient recruitment

Informed consent was obtained from PDAC and GC patients to provide endoscopic and surgical tumor specimens. Institutional Review Board approval at the University of Kentucky was obtained for tissue acquisition and analysis.

Development of gastric cancer PDOs from endoscopic and surgical biopsies

Endoscopic forceps biopsies (i.e., 3-4 tissue samples) [10] were rinsed 3X in D-PBS with 1X penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) in a petri dish. Samples were then minced into pieces (2-5 mm2) and incubated with 20 ml of 1X chelating buffer (distilled water with 5.6 mM Na2HPO4, 8.0 mM KH2PO4, 96.2 mM NaCl, 1.6 mM KCl, 43.4 mM sucrose, 54.9 mM D-sorbitol, 0.5 mM DL-dithiothreitol, 2 mM EDTA) for 30 min at 4°C on a carousel. Isolated glands were collected and resuspended in Cultrex PathClear Reduced Growth Factor basement membrane extract (RGF BME) Type 2 (R&D) and plated in 2 wells of pre-warmed 24-well plates at 50 μl/well. The BME dome was allowed to polymerize for 15-30 min at 37°C and was then overlaid with 500 μL pre-warmed complete organoid medium: advanced DMEM/F12 (AdDF) medium, 2.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% P/S, 1ml primocin (Invitrogen), 50% conditioned Wnt3A-medium, 20% conditioned R-spondin1 medium supplemented with 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 1% Glutamax, 2% B27, 20 ng/mL human epidermal growth factor (Invitrogen); noggin-conditioned medium [1% v/v] (U-Protein Express BV, the Netherlands) or recombinant protein (0.1 μg/ml, Peprotech); 150 ng/mL human fibroblast growth factor-10 (100 ng/ml, Peprotech); 1.25 mM N-acetyl-L-cystein; 10 mM nicotinamide; 10 nM human gastrin; and A83-01 (0.5 μM, Tocris). Y-27632 (10 μM, Tocris) was also added to complete organoid media during first seeding and subsequently for passaging. Organoid cultures were kept at 37°C, 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator.

Creation of PDAC PDOs from surgical biopsies

We have previously described the creation of PDAC PDOs from endoscopic biopsies[9, 25, 26]. Briefly, for surgical specimens in this study, PDAC tissues were minced and digested with collagenase II (5 mg/ml, GIBCO) and dispase (1 mg/ml) in 3 ml AdDF wash medium (advanced DMEM/F12 medium, supplemented with 2.5% FBS, 1% P/S, 1 ml primocin (Invitrogen), 10 mM HEPES, 1% Glutamax), in Eppendorf tubes (5 ml) on a rocker at 37°C for 30-60 min. DNase I was added for prevention of cell clumping during digestion. The digestion was stopped when no visible tissue fragment was left in the tube. After centrifugation (200×g) at 4°C for 5 min, the supernatant was transferred to a new 15 ml falcon tube and 3 ml AdDF wash medium was added for neutralization. The tube was again subjected to centrifugation (300×g) at 4°C for 5 min and the pellet was then washed twice with AdDF wash medium. The cell pellet was resuspended in RGF BME and cultured in complete PDO medium supplemented with Y27632 (10 μM) as described above.

Maintenance and growth of PDOs

Culture medium was exchanged every 2–3 d and PDOs were passaged every 5-7 d. For passaging, culture medium was removed and PDOs along with RGF BME were collected in cold AdDF wash media and transferred to new 15 ml falcon tubes. The tubes were kept on ice for 10 min, and then PDOs were mechanically disrupted by gentle pipetting (10×) with a 10 ml serological pipette attached with a 200 μl tip. PDOs were then centrifuged (200×g) for 5 min at 4°C and the supernatant was carefully removed. The PDO pellet was then resuspended in RGF BME and plated in additional wells for expansion or biobanked in Recovery Cell Culture Freezing Media (Gibco) and stored in liquid nitrogen for later use.

Histologic characterization of PDOs

For immunohistologic assessment PDOs were resuspended in RGF BME, and PDOs (200 μl) were seeded on a transwell membrane insert (0.4 μm pore, ThermoFisher) in 24-well plates. On the 2nd/3rd day after seeding, the culture medium was discarded and the PDO dome was washed with warm D-PBS and fixed overnight with 10% formalin at room temperature. The membrane insert with the attached PDO drop was then carefully removed and embedded in a pre-warmed Histogel™ drop (100 μl, Thermo Scientific) on a petri dish. After solidification, the hydrogel drop was transferred to a 15 ml falcon tube with 70% ethanol. The Histogel™ embedded PDO dome was submitted to the Biospecimen Procurement and Translational Pathology Shared Resource Facility (BPTP SRF) at the University of Kentucky for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis with internal controls. Both GC and PDAC PDOs were immunostained for CK7 and CK20, since 97% of PDACs express CK7 or CK20 or both; and GCs of which 71% are CK7 (+) and 30% are CK20 (+)[27, 28]. Images were taken with the Nikon Ts2 microscope.

Creation of PDO single-cells

Based on our experience with developing PDOs from endoscopic biopsy tissues (3-4 forceps bites) from GC patients, the isolated glands were sufficient for plating into 2 wells (50 μl/well) in a 24-well plate. This amount of tissue ensured appropriate density to initiate PDO growth (designated passage 0, P0). In order to achieve the future goal of using PDOs for drug sensitivity testing within 2 weeks of initial biopsy, PDO development requires quick expansion to obtain abundant biological material at time of passage 2 (P2) (i.e., approximately 10 days following initial plating). We hypothesized that PDO single-cells could be rapidly developed, even from endoscopic biopsy tissues, to provide sufficient biologic material for drug sensitivity testing.

To create single-cells from standard PDOs, PDOs were collected with cold AdDF wash medium into 15 ml tubes and centrifuged (200×g) for 5 min at 4°C. Then the supernatant was carefully removed with the remaining RGF BME left at the bottom of the tube. TrypLE™ Express (1 ml) (ThermoFisher) [29] was then added to the PDO pellets and the tube was incubated in a 37°C water bath for 5-15 min depending on the size of PDO pellets. DNase I was also added during digestion to prevent cell clumping. After digestion, AdDF wash medium (2 ml) was added for neutralization and mild pipetting was performed to mechanically disrupt the PDOs into single-cells. These single-cells were centrifuged (200×g) for 5 min at 4°C and washed again in cold AdDF medium. After the last wash, cells were pipetted mildly and counted using the Countless II FL cell counter (Invitrogen). The cells were then centrifuged and resuspended in cold RGF BME and plated in pre-warmed 24-well plates at 50 μl/well for expansion. Single-cell growth was tracked and imaged with the Nikon Ts2 microscope.

Drug sensitivity testing of standard PDOs compared with paired PDO single-cells

To compare the drug responses of standard PDOs and PDO single-cells, we first performed drug sensitivity testing on paired, same late passage (P4-10) PDO standard and single-cell lines developed from patients with PDAC (N=2) and GC (N=2). PDOs were collected in cold AdDF wash medium and split equally into two 15 ml falcon tubes. One tube was utilized to maintain standard PDOs and the other to create single-cells. Based on the cell counting of single-cells, standard PDOs and PDO single-cells were resuspended and plated for drug testing at the same concentration (2×105 cells/ml). As described previously, standard PDOs were resuspended in 50% RGF BME in AdDF wash medium and then plated in 48-well plates at 20 μl drop/well (approximately 4000 cells, 20-50 PDOs). PDOs are plated in larger-sized wells given their larger 3D structure, but single-cells can be plated in 96-well plates at 10 μl drop/well (approximately 2000 cells) because they form smaller 3D structures that do not require larger surface areas. When biological material is not abundant, single-cells can even be plated as low as 500 cells/well given the consistent distribution and miniature size. Standard PDOs were treated at 24 h after passaging, while single-cells were treated 72 h after plating to allow for single-cells to reform into uniform miniature PDOs, which is important to allow single-cells to closely mimic the primary tumor.

Standard PDOs and PDO single-cells were treated with the following chemotherapeutic drugs: 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), irinotecan, epirubicin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel. Of these agents, all are used in first or second-line regimens for PDAC and/or GC. PDOs were treated with eight different concentrations of each drug (0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 50, and 100 μM). For drug treatment, culture medium was replaced with medium containing the respective drug or solvent control (DMSO) and incubated for 48 h. CellTiter-Glo assay (Promega) was performed in both standard PDOs and PDO single-cells. Plates were read on Synergy HTX plate reader (BioTek). All cell viability experiments were conducted in triplicate and standard deviations were reported. IC50 was calculated from a dose-response curve graphed with the GraphPad Prism software.

Comparison of drug responses between P2 PDO single-cells and P4 standard PDOs

After testing drug sensitivities in paired standard PDOs and single-cells at later passages, we sought to test the feasibility of using early passage single-cells (i.e., P2) for drug screening to meet the clinical decision making window of 2 weeks. Two newly created PDAC surgical PDOs were compared with P2 PDO single-cells and paired P4 standard PDOs. P2 PDOs were digested with TrypLE™ Express (1 ml) and then washed twice with cold AdDF wash medium and counted before resuspension in 50% RGF BME at 1×105 cells/ml and plated in a 96-well plate at 10 μl drop/well (approximately 1000 cells). A smaller volume of single-cells was plated compared to our prior experiments given the limited quantity of PDOs at P2. P4 PDOs were plated and grown in standard fashion. Complete PDO medium was added and replaced on day 3 with medium containing different concentrations of chemotherapeutic drugs as mentioned above. Cell viability was measured 48 h after drug treatment and dose-response curves were graphed.

Single-Cell viability analysis

To ensure that single-cells were viable prior to drug treatment, cell viability was assessed. Two representative wells of PDO single-cells were used for cell scoring to determine viability. Briefly, plated PDOs were washed with warm D-PBS and then incubated with D-PBS containing the dead cell-permeable red fluorescent dye Ethidium homodimer-1 (4 μmol/L) and the live cell-impermeable green fluorescent dye Calcein-AM (2 μmol/L; LIVE/DEAD Kit, ThermoFisher) for 1 h at 37°C. H33542 (Sigma-Aldrich) was used for nucleus staining. Calcein-AM is a nonfluorescent membrane-permeable probe that is hydrolyzed by cellular esterases to form a green fluorescent membrane impermeable compound. With this dye combination, necrotic cells appear red and viable cells are green. PDOs were imaged with CellInsight CX7 High-Content Screening Platform (ThermoFisher).

RESULTS

Creation of PDOs from PDAC and GC tissues

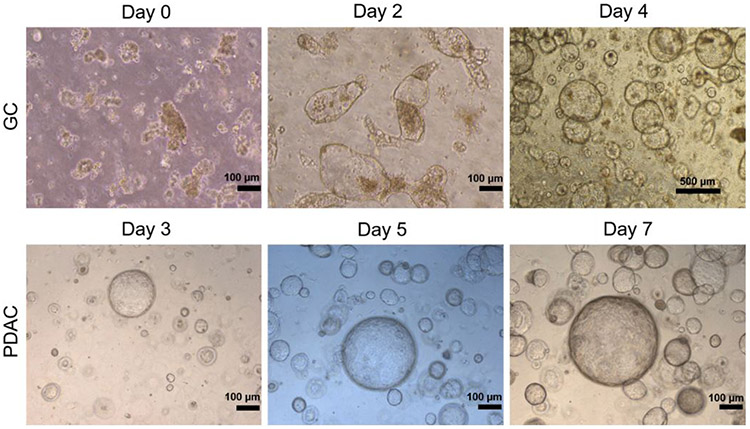

We created GI cancer organoids from PDAC and GC biopsies and surgical specimens as previously described[9, 10, 25, 26]. In brief, patient cancer tissues were transported in organoid media on ice to our laboratory and processed immediately for PDO creation (day 0). Twenty-four hours after embedding, gastric glands or dissociated PDAC materials generated cystic structures. After 2-3 days in culture, the cystic structures started folding and budding and growing into organoids (Figure 1) when cultured with the “generic” WRN complete organoid medium initially developed by Sato et al.[30], and applied in our lab with modifications (see Methods). PDOs were passaged every 5-7 days.

Figure 1.

Representative images of initial (ie P0) patient derived organoids (PDO) development from GC and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) specimens. The top panel shows PDOs created from gastric cancer (GC) endoscopic biopsies, whereas the bottom panel shows PDOs created from PDAC surgical tissues. The isolated cells are embedded in RGF BME and cultured in WRN medium and generate cystic structures that fold and bud into organoids within 3-7 days.

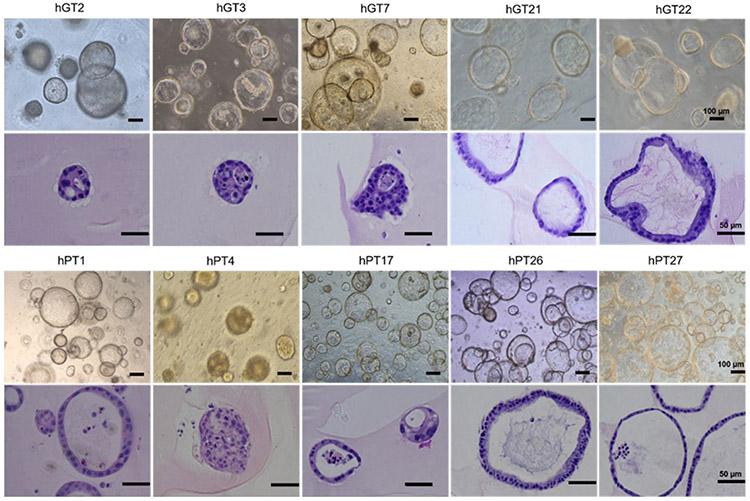

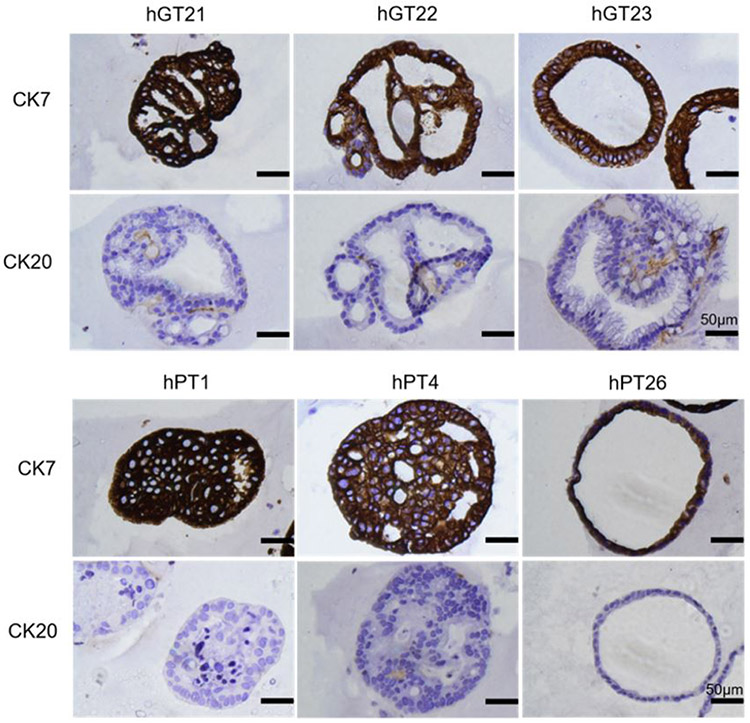

Characterization of GC and PDAC PDOs

To confirm that PDOs were representative of the primary tumors from which they were derived, we assessed the histologic characteristics of PDOs. H&E and IHC stains for GC and PDAC markers were performed by an institutional core facility. Figure 2 shows representative bright field images of GC and PDAC PDOs and corresponding H&E stains demonstrating cellular features that mirror those from parent solid tumor specimens. Figure 3 shows representative IHC staining of CK7/CK20 on GC and PDAC PDO lines. CK7 and CK20 are typically expressed in epithelial cancers, however the majority of upper GI cancers, such as GC and PDAC, have high expression of CK7 and low expression of CK20[27]. In Figure 3, all PDAC and GC PDOs are CK7(+) with weak or null CK20 expression.

Figure 2.

Representative bright field microscopy images of 5 gastric cancer (GC) patient-derived organoids (PDOs) (hGT2, hGT3, hGT7, hGT21, hGT22) and 5 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) PDOs (hPT1, hPT4, hPT17, hPT26, hPT27) and their corresponding H&E stain. PDOs were imaged between passage 2-5. H&E stains of each PDO line demonstrate the cellular and morphological characteristics that are unique to each line, which is similar to how individual patient tumor specimens display unique and individual characteristics.

Figure 3.

Representative IHC stains of gastric cancer (GC) patient-derived organoids (PDOs) (hGT21, hGT22, and hGT23) and PDAC PDOs (hPT1, hPT4, and hPT26) for CK7/CK20. All GC and PDAC PDO lines exhibited intense immunostaining for CK7 and weak to null immunostaining for CK20 as seen in PDAC and GC tumor specimens.

Creation of PDO single-cells

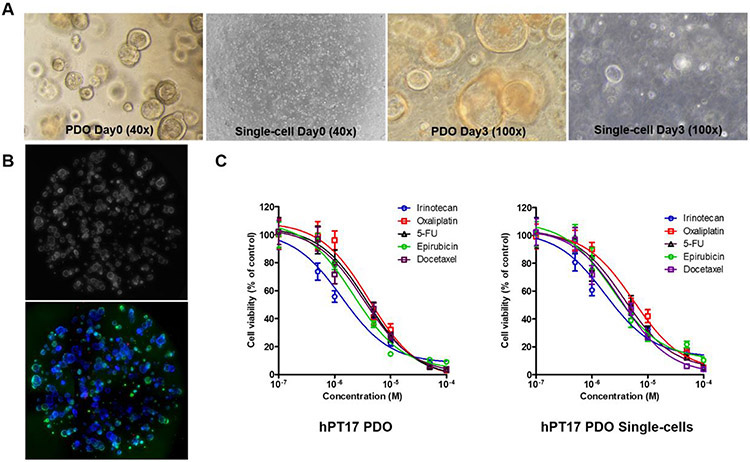

Since our ultimate goal was to utilize biopsy-derived PDOs for personal medicine applications within a 2-week period, we sought to rapidly increase PDO yield to perform individualized drug sensitivity testing. We first performed drug sensitivity testing in later passage PDOs to ensure abundant growth of PDOs for drug testing. We used TrypLE™ Express (ThermoFisher) for single-cell dissociation and tested the incubation time for dissociation of PDOs into single-cells and observed that a 7-10 min dissociation time was optimal as longer incubation can damage PDOs. DNase I (0.1 mg/mL or 200 U/mL) was added to prevent cell clumping and to increase single-cell yield. Within 2-3 days, more than 50% of PDO single-cells regrew into uniform, small-sized PDOs (~50 μm). We elected to wait to treat single-cells until these miniature PDOs had fully formed their 3D structures, which occurred by day 3. Figure 4A shows representative images of the growth of standard PDOs with paired single-cells of hPT17 PDOs on day 3 after passage.

Figure 4.

Comparison of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) hPT17 standard patient derived organoids (PDOs) and PDO single-cells. (A) Bright field images of standard PDOs compared to single-cells demonstrating morphological differences. On day 0 after plating, PDOs appear as clumps of cells while single-cells are individual cells. The morphology of standard PDOs and single cells was similar by day 3 after plating, albeit single-cells are uniformly sized compared to standard PDOs, which have a large size and variation. (B) Representative images of single-cell scoring with Hoechst/Calcein AM/EthD-III stain analyzed with CellInsight CX7 Platform (phase contrast and fluorescence images, overlay of 4 quadrants, 40x magnification), revealing >95% cell viability before drug treatment. (C) Dose-response curves revealed identical drug discrimination for each of the 5 drugs tested in hPT17 PDOs and PDO single-cells.

Comparing drug sensitivity testing of late passage standard PDOs and PDO single-cells

To compare discrimination of drug sensitivity testing between standard PDOs and PDO single-cells, we first performed drug sensitivity testing on late passage PDO lines (i.e., P4-10) developed from PDAC (hPT17, hPT26) and GC (hGT2, hGT21) patient cancer tissues. Standard PDOs were plated in 48-well plates and treated at 24 h after plating with 5 chemotherapeutic drugs at 8 concentrations (0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 50, and 100 μM) in triplicate for 48 h. Single-cells were plated on a 96-well plate, but treated at 72 h after plating to allow for formation of uniformly sized miniature PDOs. The equal size and even distribution of PDO single-cells facilitated plating cells in a 96-well plate at a lower volume, thereby decreasing the volume of biological material required to perform drug testing. This in turn allowed a greater number of drugs to be tested simultaneously in one assay. Based on the CellTiter-Glo assay results, IC50 curves of each drug for standard PDOs and single-cells were graphed and IC50 values were calculated. In Figure 4, dose-response curves revealed similar drug sensitivity test results in hPT17 PDO single-cells and paired standard PDOs. IC50 values were calculated, which identified the best response to irinotecan in both PDO single-cells and standard PDOs.

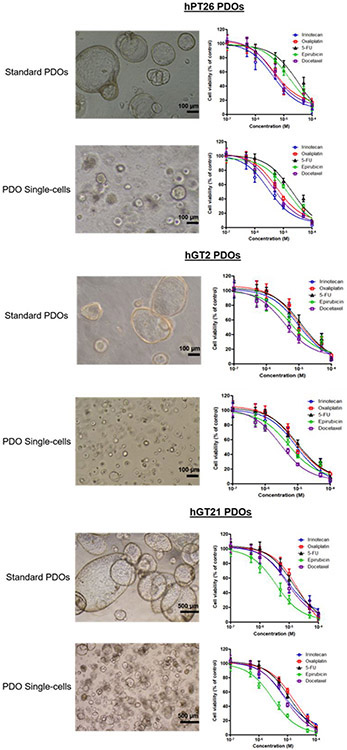

To validate our results and confirm the feasibility of using PDO single-cells for drug sensitivity testing, we tested the same 5 chemotherapy regimens in 1 additional PDAC (hPT26) and 2 GC (hGT2, hGT21) paired standard PDOs and PDO single-cell lines. Importantly, we observed a consistent discriminatory pattern of drug test results in all additional paired standard PDO and PDO single-cell lines. Specifically, in the hPT26 PDAC lines, we observed the highest sensitivity to irinotecan. The paired GC hGT2 lines were most sensitive to docetaxel and GC hGT21 lines were most sensitive to epirubicin (Figure 5). These results indicate that PDO single-cells yield drug sensitivity testing results similar to standard PDO lines.

Figure 5.

Comparison of cellular morphology/distribution and drug sensitivity testing in paired standard patient derived organoids (PDOs) and PDO single-cells (PDAC hPT26, GC hGT2, and GC hGT21). Single-cells again demonstrated uniform size and even distribution compared with standard PDOs. However, as noted earlier between multiple PDO lines, each single-cell line morphology and distribution was unique. All three paired lines showed identical discriminatory drug responses to the 5 different chemotherapies tested.

Comparison of drug sensitivities with PDAC P2 single-cells and P4 standard PDOs

To further evaluate the feasibility of using early passage (i.e., P2) PDO single-cells for chemotherapeutic drug sensitivity testing, we utilized mechanical dissociation for passaging and single-cell dissociation at P2 on 2 newly created PDAC PDOs (hPT27 and hPT28) from surgical specimens. We first tested 4 drugs (5-FU, docetaxel, epirubicin and irinotecan) at 7 different concentrations (0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, and 50 μM) for 48 h on P2 single-cells. Each drug concentration was tested in triplicate. Cell morphology was imaged before cell viability assay and dose-response curves of each drug were generated based on the results of CellTiter Glo Assay (data not shown). Following standard passaging of PDOs, we then tested the same set of drugs on P4 PDOs plated in 48-well plates, and the dose-response curves were graphed. In paired standard PDOs and single-cells of both hPT27 and hPT28 lines, drug testing results revealed lowest IC50 value to epirubicin (data not shown).

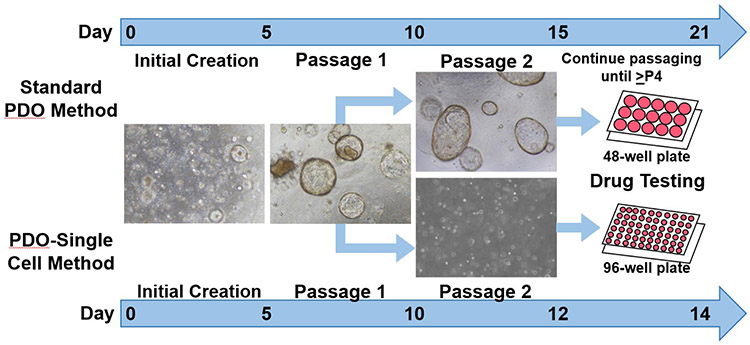

Our optimized technique for the creation of PDO single-cells may be utilized to select the most likely effective therapy for patients with PDAC and GC. Based on our results, we observed that the creation of PDO single-cells was rapid and yielded abundant biological material. Additionally, we noted that early passage single-cells demonstrated similar dose response curves and IC50 values to the most effective drug as later passage PDOs. We propose that our technique may provide the ability to perform drug sensitivity testing within two weeks (Figure 6), and may produce enough material to screen even more drugs as they become clinically available.

Figure 6.

Diagram of patient derived organoids (PDO) single-cell platform for future precision medicine applications. Standard PDO and PDO single-cell creation is the same until P2. Single cells were created by digesting P1 PDOs with TripLE Express and DNase I. Single-cells developed into smaller and uniformly sized PDOs that evenly distributed in smaller volumes (10 μl/well) in 96-well plates. To obtain sufficient volumes of biologic material, standard PDOs require passaging until ≥passage 4, which may require 19-21 days or longer. In contrast, single-cells were rapidly developed and utilized for drug testing on days 12-14.

DISCUSSION

There is a real race against time from when cancer diagnoses are made and treatment regimens must begin. Often the selection of drugs is straightforward since therapeutic options are limited. With advancements in drug discovery however, GI cancers now have options for first-line treatment regimens. Yet patients respond differently to various therapies and given the aggressive nature of GI cancers, improved survival is dependent on clinical activity from the first treatment regimen. Personalized medicine approaches have revealed the importance of detecting actionable genetic data. Often NGS platforms seeking tumor genomic alterations, such as FoundationOne, have turnover times of approximately 2 weeks, after which clinical treatment plans based on these results can be implemented. However, when patients have no actionable genetic alterations, as is often the case, and several therapeutic options are available, the clinician is left to select the best treatment option by discretion.

In common clinical scenarios, patients with GI cancers present with non-specific signs or symptoms, thereby prompting radiographic imaging studies. Following identification of concerning radiological features, biopsies are often performed to establish a pathological diagnosis. At this point in the clinical diagnosis, providers are typically not aware which patients may have actionable genetic alterations to guide treatment options. Generating PDO-derived drug sensitivity data within the 2-week timeframe required to receive NGS data was our objective to enable patients who have no actionable genetic mutations to nevertheless receive personalized treatment options. Utilization of PDOs in this approach is grounded in their accuracy in predicting clinical efficacy of various drugs.

While cancer PDOs have become a promising tool for cancer drug discovery and personalized medicine[31-33], there is no standard operating procedure for performing chemosensitivity assays in PDOs nor establishing sufficient biological material to perform such testing. Due to limited tissue volumes obtained from biopsy specimens and variations in organoid growth rates between different tumor types, there has been no standardized platform for PDO drug screening. Therefore, we sought to develop a standardized procedure to generate a sufficient volume of PDOs to perform rapid drug sensitivity testing for personalized medicine applications.

Our current work resolves two important limitations when utilizing PDOs. First, there is a considerable lack of PDO volume during early passages. Second, PDOs vary greatly in size and shape, which generates inaccurate and non-reproducible drug testing results. Although there are reports utilizing different methods to manually scale the size of PDOs before drug testing[18, 34], this method can only be applied to an abundant volume of PDOs, which occurs at later passages. Other investigators have used a similar enzymatic method to ours to dissociate PDOs into single-cells, however these methods provide no procedural details nor comparison reports of drug response between single-cells and PDOs to demonstrate their accuracy and efficacy[15, 35]. Importantly, we identify that single-cells reform into miniature PDOs, which enables us to recapitulate the phenotype of the primary tumor. Drug sensitivity testing of single-cells was comparable to PDOs, and in early passage single-cells we were able to identify the most effective chemotherapy for each line. Our results demonstrated that single-cells can be quickly created, represent the original parent PDOs, and can be utilized for precision medicine applications in a reasonable time frame.

CONCLUSIONS

PDOs have the potential to help improve outcomes for patients with GI cancers. They are rapid-developing, representatives of primary tumors that show discriminatory responses in drug sensitivity testing of chemotherapies. While many studies report the success of establishing GI cancer PDOs, there is no universal method for creating, propagating, or drug testing PDOs in a clinically useful manner. This is especially important when only minute amounts of tumor tissues are available. Our study details an optimized methodology for assessing drug responses in PDO single-cells. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that PDO single-cells are effective tools for clinically relevant high-throughput drug testing when only small samples of the primary tumor are obtainable. Using this technique, we have created a rapid and effective personalized medicine platform to select drugs most likely to demonstrate a clinical response for individual patients with GI cancers.

Acknowledgments

Support: This research was supported by the Biospecimen Procurement and Translational Pathology Shared Resource Facility of the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center (P30 CA177558), the Shared Resource Facilities of the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center (P30CA177558), and NIH Training Grant (T32 CA160003).

Selected for the 2020 Southern Surgical Association Program.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.SEER Cancer Stat Facts: Pancreatic Cancer 2019 2019.

- 2.Pauli C, Hopkins BD, Prandi D, et al. Personalized In Vitro and In Vivo Cancer Models to Guide Precision Medicine. Cancer Discov. 2017;7: 462–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holch JW, Metzeler KH, Jung A, et al. Universal Genomic Testing: The next step in oncological decision-making or a dead end street? Eur J Cancer. 2017;82: 72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parca L, Pepe G, Pietrosanto M, et al. Modeling cancer drug response through drug-specific informative genes. Sci Rep. 2019;9: 15222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483: 603–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witkiewicz AK, Balaji U, Eslinger C, et al. Integrated Patient-Derived Models Delineate Individualized Therapeutic Vulnerabilities of Pancreatic Cancer. Cell Rep. 2016;16: 2017–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin M, Gao M, Cavnar MJ, Kim J. Utilizing gastric cancer organoids to assess tumor biology and personalize medicine. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;11: 509–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin M, Gao M, Pandalai PK, Cavnar MJ, Kim J. An Organotypic Microcosm for the Pancreatic Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao M, Lin M, Moffitt RA, et al. Direct therapeutic targeting of immune checkpoint PD-1 in pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2019;120: 88–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao M, Lin M, Rao M, et al. Development of Patient-Derived Gastric Cancer Organoids from Endoscopic Biopsies and Surgical Tissues. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25: 2767–2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merker SR, Weitz J, Stange DE. Gastrointestinal organoids: How they gut it out. Dev Biol. 2016;420: 239–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Werner K, Weitz J, Stange DE. Organoids as Model Systems for Gastrointestinal Diseases: Tissue Engineering Meets Genetic Engineering. Current Pathobiology Reports. 2016;4: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boj SF, Hwang CI, Baker LA, et al. Organoid models of human and mouse ductal pancreatic cancer. Cell. 2015;160: 324–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Driehuis E, van Hoeck A, Moore K, et al. Pancreatic cancer organoids recapitulate disease and allow personalized drug screening. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan HHN, Siu HC, Law S, et al. A Comprehensive Human Gastric Cancer Organoid Biobank Captures Tumor Subtype Heterogeneity and Enables Therapeutic Screening. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23: 882–897 e811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seidlitz T, Merker SR, Rothe A, et al. Human gastric cancer modelling using organoids. Gut. 2019;68: 207–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dedhia PH, Bertaux-Skeirik N, Zavros Y, Spence JR. Organoid Models of Human Gastrointestinal Development and Disease. Gastroenterology. 2016;150: 1098–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francies HE, Barthorpe A, McLaren-Douglas A, Barendt WJ, Garnett MJ. Drug Sensitivity Assays of Human Cancer Organoid Cultures. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1576: 339–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kondo J, Ekawa T, Endo H, et al. High-throughput screening in colorectal cancer tissue-originated spheroids. Cancer Sci. 2019;110: 345–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haber AL, Biton M, Rogel N, et al. A single-cell survey of the small intestinal epithelium. Nature. 2017;551: 333–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang P, Yang M, Zhang Y, et al. Dissecting the Single-Cell Transcriptome Network Underlying Gastric Premalignant Lesions and Early Gastric Cancer. Cell Rep. 2019;27: 1934–1947 e1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Velletri T, Villa EC, Lupia M, et al. Single cell derived organoids capture the self-renewing subpopulations of metastatic ovarian cancer. bioRxiv. 2018: 484121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velasco S, Kedaigle AJ, Simmons SK, et al. Individual brain organoids reproducibly form cell diversity of the human cerebral cortex. Nature. 2019;570: 523–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mead BE, Ordovas-Montanes J, Braun AP, et al. Harnessing single-cell genomics to improve the physiological fidelity of organoid-derived cell types. BMC Biol. 2018;16: 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tiriac H, Belleau P, Engle DD, et al. Organoid Profiling Identifies Common Responders to Chemotherapy in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018;8: 1112–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tiriac H, Bucobo JC, Tzimas D, et al. Successful creation of pancreatic cancer organoids by means of EUS-guided fine-needle biopsy sampling for personalized cancer treatment. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87: 1474–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takami H, Sentani K, Matsuda M, Oue N, Sakamoto N, Yasui W. Cytokeratin expression profiling in gastric carcinoma: clinicopathologic significance and comparison with tumor-associated molecules. Pathobiology. 2012;79: 154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu PG, Weiss LM. Keratin expression in human tissues and neoplasms. Histopathology. 2002;40: 403–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellerstrom C, Strehl R, Noaksson K, Hyllner J, Semb H. Facilitated expansion of human embryonic stem cells by single-cell enzymatic dissociation. Stem Cells. 2007;25: 1690–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459: 262–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weeber F, Ooft SN, Dijkstra KK, Voest EE. Tumor Organoids as a Pre-clinical Cancer Model for Drug Discovery. Cell Chem Biol. 2017;24: 1092–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tuveson D, Clevers H. Cancer modeling meets human organoid technology. Science. 2019;364: 952–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagle PW, Plukker JTM, Muijs CT, van Luijk P, Coppes RP. Patient-derived tumor organoids for prediction of cancer treatment response. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018;53: 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Broutier L, Mastrogiovanni G, Verstegen MM, et al. Human primary liver cancer-derived organoid cultures for disease modeling and drug screening. Nat Med. 2017;23: 1424–1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim M, Mun H, Sung CO, et al. Patient-derived lung cancer organoids as in vitro cancer models for therapeutic screening. Nat Commun. 2019;10: 3991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]