SUMMARY

TET proteins are DNA demethylases that can oxidize 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to generate 5- hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and other oxidized mC bases (oxi-mCs). Importantly, TET proteins govern cell fate decisions during development of various cell types by activating a cell-specific gene expression program. In this review, we focus on the role of TET proteins in T-cell lineage specification. We explore the multifaceted roles of TET proteins in regulating gene expression in the contexts of T-cell development, lineage specification, function, and disease. Finally, we discuss the future directions and experimental strategies required to decipher the precise mechanisms employed by TET proteins to fine-tune gene expression and safeguard cell identity.

Keywords: TET proteins, epigenetics, 5hmC, cell development

1. INTRODUCTION

The term “epigenetics” was introduced in 1942 by Waddington to describe phenotypical alterations that were not associated with genetic changes. It is now appreciated that epigenetic mechanisms regulate the inheritance of gene expression programs by mediating alterations in chromatin while simultaneously keeping DNA sequences intact (1). Epigenetic mechanisms should meet at least one of the following criteria: cell division results in signal propagation, daughter cells inherit the signal, or the signal impacts gene expression (2). The major epigenetic mechanisms are post-translational chromatin modifications (3) and DNA modifications (4, 5).

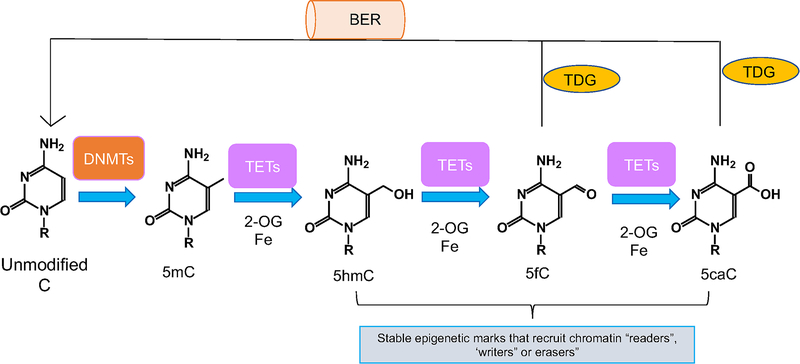

Cytosine DNA methylation is achieved by the catalytic activity of the family of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) (6) DNMT1, DNMT3a, DNMT3b (Fig. 1). In somatic cells, 5-methylcytosine (5mC) is almost exclusively found in the CpG sequence context (7). Genome wide studies employing whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) to assess cytosine methylation have demonstrated that highly transcribed genes have largely unmethylated CpG promoters whereas non-transcribed genes exhibit high levels of cytosine methylation in the CpG context of their promoters (7, 8). However, the role of intragenic methylation remains unclear. Until a decade ago, it was believed that 5mC can be exclusively diluted during cell division in mammalian cells. The discovery that Ten Eleven Translocation (TET) proteins regulate active DNA demethylation (9) revolutionized our understanding of the DNA de-methylation process.

Figure 1: TET-mediated DNA de-methylation.

DNA methyltransferase (DNMTs) proteins methylate cytosine (C) to generate 5-methylcytosine (5mC). TET proteins can oxidize 5mC to generate 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC). Thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG) can excise 5fC and 5caC, which are subsequently replaced with unmodified C through base excision repair (BER), completing the pathway of active DNA-demethylation. 5mC and 5hmC can be passively diluted to C during cell division.

2. FAMILY OF TET PROTEINS

TET proteins are 2-oxoglutarate- and Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenases; via their catalytic activity, they can oxidize 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) in DNA (9) and to other oxidized cytosine products (oxi-mCs): 5-formylcytosine (5fC) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC) (Fig. 1) (10, 11). TET proteins mediate “active” (replication-independent) DNA demethylation, achieved through excision of 5fC and 5caC by thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG) followed by replacement with an unmethylated cytosine through base excision repair (4, 12). 5hmC is passively diluted via replication (13, 14) (Fig. 1). Besides promoting DNA demethylation, the oxi-mCs—5hmC as well as the less abundant 5fC and 5caC—are stable epigenetic marks (Fig. 1). These oxi-mC species can recruit specific readers to impact genomic stability, DNA repair and transcriptional elongation (15, 16),(17–19).

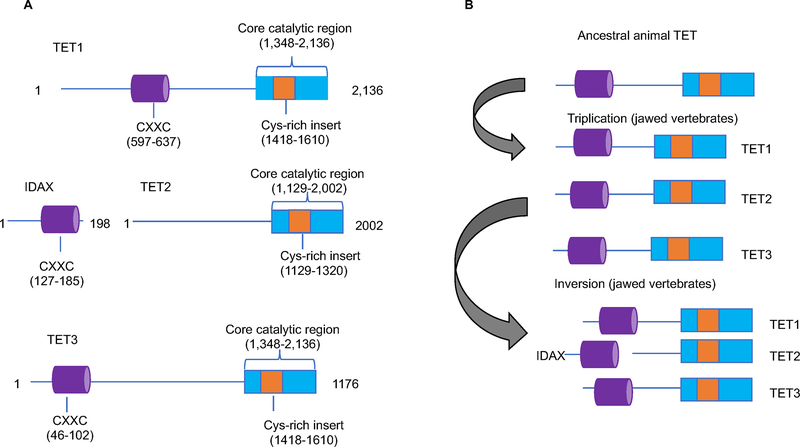

In mammalian cells, three members of the TET family of proteins have been described: TET1, TET2, and TET3. TET proteins share a common catalytic domain at their C-terminus (Fig. 2) that permits the oxidation of 5mC to 5fC and 5caC (10, 11, 20). The C-terminal catalytic domain of TET proteins comprises a cysteine-rich, double stranded β-helix (DSBH) DNA-binding domain with Fe(II)- and oxo-glutarate-dependent activity. The DSBH DNA-binding domain allows for assembly of iron and α-ketoglutarate at a methylated CpG island. The interaction between TET and DNA is stabilized by the cysteine-rich domain enveloping the DNA-binding domain. Notably, TET involvement with DNA is independent of the methyl group, enabling TET-mediated oxidation of the downstream oxi-mCs (21).

Figure 2: Overview of the structural domains of mammalian TET proteins.

A. Schematic representation of TET1, TET2, and TET3. The catalytic domain is shared among all three TET proteins. The C-terminal catalytic domain consists of a cysteine rich and a double stranded β-helix (DSBH) DNA-binding domain and has iron and oxo-glutarate dependent activity. TET1 and TET3 share a CXXC DNA-binding domain. TET2 does not have a CXXC DNA binding domain. The number of amino acids is indicated. The depicted numbers correspond to human TET proteins.

B. In jawed vertebrates, triplication to an ancestral Tet gene gave rise to three paralogues that initially shared a CXXC DNA binding domain. A chromosomal inversion resulted in the detachment of the exon encoding for the CXXC DNA binding domain of TET2 and gave rise to a separate gene, encoding for IDAX.

In addition, TET1 and TET3 share an N-terminal CXXC DNA-binding domain (Fig. 2). The CXXC DNA-binding domain has regulatory functions independent of the TET catalytic activity. For instance, in embryonic stem (ES) cells, the binding of TET1’s CXXC domain to DNA prevents the activity of DNMTs, prohibiting DNA methylation (22). Additionally, CXXC DNA-binding in differentiated cells precludes the aberrant methylation of CpG islands (CGIs) (23). It has been shown that the CXXC domain of TET3 shows high affinity for 5caC and can specifically read this modified cytosine during base excision repair (BER)(24). Initially, TET2 had a CXXC DNA binding domain like its paralogs. However, during evolution, a chromosomal inversion occurred, separating the CXXC domain from the rest of TET2 protein. As a result, a separate gene arose that encodes for the protein Inhibition of the Dvl and Axin complex (IDAX) (25) (26) (Fig. 2). Currently, TET2 lacks a CXXC domain and as a result TET2 cannot bind to the DNA directly (Fig. 2).

TET proteins are differentially expressed across different cell types during development (27). TET1 is highly expressed in ES cells, gradually decreasing in expression as the cells differentiate (9, 10, 28). In ES cells, TET2 is lowly expressed compared to TET1, but TET2 expression levels increase during the process of differentiation (4). TET3 is not expressed in ES cells but achieves increased expression during differentiation (29).

3. DYNAMIC DISTRIBUTION OF 5HMC DURING T-CELL DEVELOPMENT

The abundance of oxi-mC species is highly dynamic and variable in mammalian cells. In ES cells, 5hmC comprises 5–10% of total 5mC enrichment. It is infrequent in immune populations, however, where it is encountered at only 1% of the total level of 5mC (30). 5fC and 5caC are even more scarce (11). 5hmC is highly enriched in Purkinje neurons, representing ~40% of the level of 5mC (31). Notably, 5hmC is a rather stable modification and exhibits resistance against oxidization to 5fC or 5caC (32). The revolutionary discovery that TET proteins can oxidize 5mC to 5hmC initiated efforts to place 5hmC within the epigenomic landscape and gain insight on the role of this novel epigenetic mark in regulating gene expression. Thus, various groups mapped 5hmC in ES as well as in neural cells, showcasing a correlation between 5hmC enrichment and high levels of gene expression.

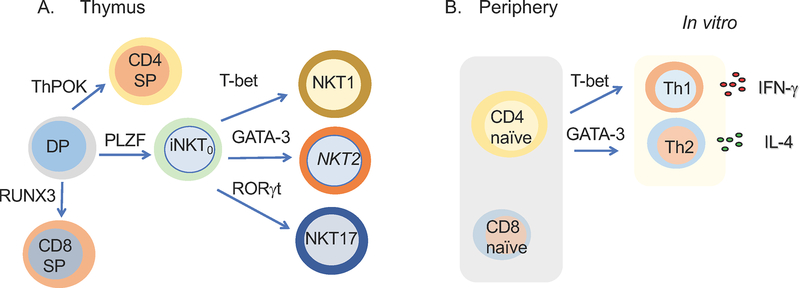

However, these attempts to unravel 5hmC distribution across the genome were static, as they were focused on a given cell type. We embarked on dissecting 5hmC across sequential, well-defined steps during T-cell development (13)(Fig. 3). This system offers numerous advantages: i) there is a well-established precursor-progeny relationship, ii) the transcriptional networks that govern the distinct decisions of lineage choice versus alternate lineage rejection are well described and iii) it is technically feasible to isolate highly pure populations at distinct stages. We isolated subsets during thymic development, starting with double positive (DP) thymocytes, CD4 single positive (SP) cells, and CD8 SP cells (Fig. 3A). Moreover, we isolated naïve CD4 and CD8 T cells from the periphery (Fig. 3B). In addition to the ex vivo populations, we interrogated the distribution of 5hmC in CD4 cells that were polarized and subsequently expanded in vitro towards Th1 and Th2 lineages (Fig. 3B). In all these populations, 5hmC was enriched across the gene body of very highly expressed genes (Fig. 4). CD4 and CD8 SP cells showed the highest levels of 5hmC among the analyzed populations. Strikingly, Th1 and Th2 cells exhibited greatly reduced levels of 5hmC compared to the ex vivo analyzed subsets. To decipher the total levels of 5hmC during T-helper polarization we performed analysis by DNA dot blot of naïve and in vitro polarized CD4 cells towards Th1 and Th2 lineages in distinct time points spanning from 24 hours up to 5 days in culture (13). Our data revealed that 5hmC was abundant in Th1 and Th2 subsets up to 48 hours of culture but it was passively diluted across cell division (13). Similar observations have been reported across mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (14).

Figure 3: Schematic representation of the T-cell differentiation system that we employed to assess the dynamic distribution of 5hmC.

A) Thymic subsets that were used were double positive cells (DP). As DP cells are positively selected in the thymus to give rise to CD4 single positive (SP) cells, the transcription factor ThPOK is expressed. Upregulation of the lineage-specifying factor RUNX3 governs the development of CD8 SP cells. PLZF seals the fate of the iNKT cell lineage. In the thymus, three distinct iNKT subsets have been described: NKT1 cells are regulated by T-bet, NKT17 cells by RORγt, and NKT2 by GATA-3. B) Naïve CD4 T-cells were isolated and differentiated in vitro towards Th1 and Th2 conditions characterized by upregulation of T-bet and GATA-3, respectively. Also, naïve CD8 T-cells were isolated and 5hmC distribution was assessed.

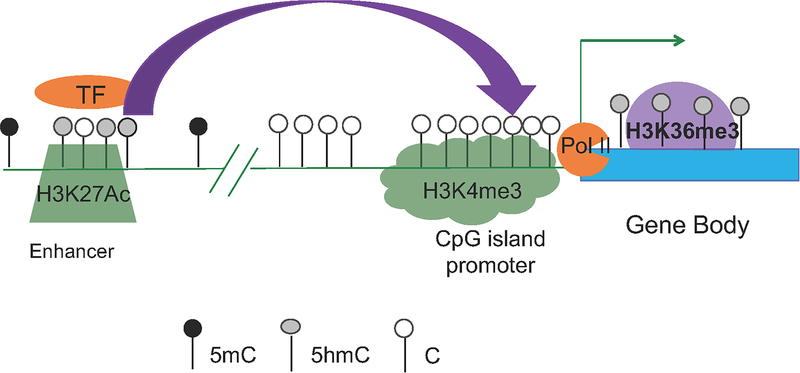

Figure 4: 5hmC enrichment in active enhancers and across the gene body of highly expressed genes.

Active enhancers are characterized by H3K27Ac enrichment. White circles depict unmodified C. Black circles depict methylated cytosine and gray circles correspond to 5hmC. 5hmC enrichment overlaps with H3K27Ac in enhancers. 5hmC is also enriched across the gene body of highly expressed genes and correlates well with H3K36me3 and elongating Polymerase II (Pol II).

In T-cells, 5hmC enrichment correlated positively with elongating polymerase II (Pol II) and H3K36me3 (13) (Fig. 4). In addition, there was a strong enrichment of 5hmC in thymic-specific (33) active enhancers, as defined by the presence of H3K27Ac (34) (Fig. 4). As a result of these investigations, 5hmC gained a spot in the T-cell epigenomic landscape alongside other well-established marks of open chromatin and active transcription.

4. TET PROTEINS IN CONVENTIONAL AND INNATE-LIKE T-CELL LINEAGE SPECIFICATION

An analysis of lineage-specifying transcription factors has indicated 5hmC levels correlate with high levels of expression. For example, Zbtb7b (encodes ThPOK) is important in CD4 lineage fate, while RUNX3 determines CD8 lineage differentiation (Fig. 3A). In both genes, the intragenic 5hmC was extremely high during the cell-stage when each factor was first expressed (13). Strong intragenic gain of 5hmC was also observed in other important genes of T-cell lineage such as Bcl11b, Satb1, and Gata3 (13). Collectively, 5hmC enrichment across the gene body of key genes for T-cell lineage indicates that TET proteins might play role in lineage specification.

To further investigate the role of TET proteins in T-cell development, TET-deficient mice were analyzed. Given the strong intragenic enrichment of 5hmC in Zbtb7b and Runx3, (13) it was hypothesized that concomitant deletion of Tet2 and Tet3 would impact the expression of ThPOK and RUNX3, compromising CD4 and CD8 SP cell development. However, the analysis of Tet2−/−Tet3flx/flx CD4 cre mice and Tet2flx/flx Tet3flx/flx CD4 cre (DKO) mice did not reveal compromised CD4 and CD8 SP differentiation (35). Gene expression analysis of Tet2/3 DKO CD8 SP cells didn’t identify Runx3 among the differentially expressed genes (35). We hypothesize that 5hmC is a stable epigenetic mark (36) and deletion of TET2 and TET3 might not be sufficient to delete 5hmC across the genome of non- dividing cell types (37). Another possibility might be the extended half-life of TET2 and TET3 proteins. Similar findings have been reported for epigenetic regulators such as JARID2 (38), EZH2 (39), JMJD3 and UTX (40, 41) that are involved in regulating histone modifications and their deletion at the DP stage does not impair CD4 or CD8 SP cell differentiation.

Strikingly, perturbation of Tet2 and Tet3 expression resulted in dramatic expansion of invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells; a relatively small T-cell population in the thymus (Table 1). Murine iNKT cells express a TCRVα14 chain and a limited number of TCRVβ chains such as TCRVβ8, TCRVβ7, TCRVβ5, and TCRVβ2 (42). In contrast to conventional T-cells, iNKT cells do not recognize peptide antigens. Instead, they can recognize lipid antigens (self-antigens or microbial-derived lipid antigens) that are presented by the MHC class I-like molecule Cd1d (42). Moreover, iNKT cells are already developed in the thymus with established activity; these cells act at the interface of innate and adaptive immunity by potently secreting cytokines during migration to the periphery (43). Reminiscent of T-helper lineages, iNKT cells can be further divided into subsets based on the lineage-specifying factor that they express (44) (Fig. 3A). In the thymus, three iNKT subsets have been described: NKT1 cells express T-bet, NKT2 cells express GATA-3, and NKT17 cells express RORγt (Fig. 3A) (44, 45). In C57BL/6 mice, NKT17 cells are the least abundant (44). However, loss of Tet2 and Tet3 results in skewing towards the NKT17 lineage (35, 46). This was attributed to an instrumental role of TET2 and TET3 for turning on the expression of ThPOK and T-bet (Fig. 5), which then repress the expression of RORγt (35). Tet3 conditional inactivation in the stage of DP thymocytes using CD4-cre (47) transgenic mice revealed a mild increase in total iNKT cell numbers both in the thymus and in the periphery as well as a skewing towards the NKT17 lineage, as revealed by RORγt upregulation in the iNKT cell compartment (35). However, the TET3 KO mice remained healthy during their lifespan (35). Mice that had a deletion of Tet2 did not show an effect on the iNKT cell differentiation. Tet2 deletion at DP thymocytes does not affect iNKT cell lineage specification, Tet3 deletion results in skewing towards NKT17 lineage whereas concomitant deletion of Tet2 and Tet3 affects iNKT cell lineage specification, maturation and proliferation resulting ultimately in malignant transformation (35). These data suggest functional redundancy between TET2 and TET3.

Table 1.

Summary of T-cell related phenotypes in TET-deficient mice

| KO mouse | Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Tet2 flx/flx CD2 cre | -Reduced in vitro differentiation of Th1 and Th17 cells | 117 |

| Tet1 flx/flx Tet2 flx/flx CD4cre | Reduced numbers of regulatory T cells (Tregs) due to hypermethylation of the CNS2 intronic enhancer that regulates the stability of FOXP3 expression | 60 |

| Tet2 flx/flx Tet3 flx/flx CD4cre | Reduced numbers of regulatory T cells (Tregs) due to hypermethylation of the CNS2 intronic enhancer that regulates the stability of FOXP3 expression | 66 |

| Tet2flx/flx Tet3flx/flx Foxp3cre | -Reduction of Tregs -Emergence of inflammation -Loss of Foxp3 expression & acquisition of a hyperactivated phenotype |

67 |

| Tet2 flx/flx Tet3 flx/flxCD4cre & Tet2−/− Tet3 flx/flx CD4cre |

-Dramatic expansion of iNKT cells -Increased frequency & numbers of NKT17 and NKT2 cells -NKT1 cells are functionally compromised -Tet2/3 DKO iNKT cells can mediate a transmissible, aggressive lymphoma |

35 |

| Tet2 flx/flx CD4cre | Loss of TET2 promotes formation of memory CD8 T cells upon LCMV infection resulting in enhanced pathogen clearance | 64 |

| Tet1flx/flx Tet3flx/flx RORcre | -Reduced expression of CD4 in cultured CD4 T-cells | 69 |

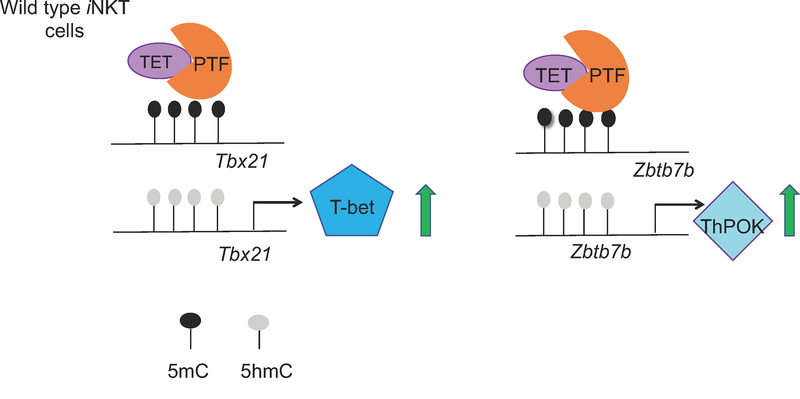

Figure 5. TET proteins in iNKT cell development.

TET proteins, by interacting with pioneer transcription factors (PTF), control the demethylation status and the deposition of 5hmC at the gene bodies of Tbx21 and Zbtb7b that encode for T-bet and ThPOK, respectively. In Tet2/3 DKO iNKT cells, compromised demethylation results in reduced expression of T-bet and ThPOK.

Strikingly, Tet2/3 DKO iNKT subsets were substantially different compared to their wild type counterparts. The precursor stage 0 Tet2/3 DKO iNKT cells exhibited increased proliferation, whereas Tet2/3 DKO iNKT stage 2 cells were characterized by altered expression of lineage-specifying factors and the cytokines they control. For instance, Tbx21—which encodes for T-bet—and Zbtb7—which encodes for ThPOK—were significantly downregulated, resulting in reduced expression of IFNγ (35). RORγt was upregulated, resulting in increased IL17F expression (35). Not only were NKT1 stage Tet2/3 DKO iNKT cells numerically less abundant, but also their identity was severely altered compared to their wild type counterparts. Tet2/3 DKO NKT1 cells secreted less IFNγ compared to the wild type NKT1 cells, suggesting compromised function. In addition, Tet2/3 DKO iNKT cells maintain high expression levels of stemness genes such as Lef1, Lmo1, and Myc (35) that are normally not expressed in mature iNKT cells but earlier in highly proliferative precursor stages (48). Simultaneous loss of TET2 and TET3 impacts every step of the iNKT cell lineage specification and maturation (35). Tet2/3 DKO iNKT precursors hyper-proliferate and as they differentiate fail to downregulate RORγt and various stemness genes. Tet2/3 DKO iNKT cells fail to mature and to establish a potent cytotoxic program, which is the signature of the NKT1 subset (35).

The increased number of iNKT cells and, specifically, increased production of IL-4 resulted in the emergence of unconventional, innate-like CD8 cells in the thymus of Tet2/3 DKO mice (35). The thymic Tet2/3 DKO CD8 cells acquire phenotypical and functional characteristics reminiscent of activated peripheral cells. They upregulate the transcription factor EOMES and surface markers such as CD44, CXCR3, and CD122 (35).

5hmC mapping in iNKT cells confirmed our previous findings in other T-cell subsets (13) and showed that 5hmC is enriched across the gene body of very highly expressed genes (35). In this setting, TET proteins regulate the deposition of 5hmC across the gene body of Tbx21 and Zbtb7b, respectively. TET2 and TET3 act mainly in regulatory elements in iNKT cells (35). Genome-wide analysis of chromatin accessibility using Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) (49) revealed that 5hmC strongly correlates with open, accessible chromatin (35). These differentially accessible regions (DARs) are located far from the transcription start site (TSS) and could represent potential regulatory elements.

Surprisingly, loss of TET proteins in iNKT cells does not result in massive gain of DNA methylation across the genome. Instead, Tet2/3 DKO iNKT cells exhibited focal alterations in DNA methylation, primarily in genomic regions that were differentially methylated during iNKT cell differentiation (35). Remarkably, besides the anticipated gain of DNA methylation in Tet2/3 DKO iNKT cells, there were also some additional regions that were already methylated in wild type cells but gained additional methylation upon concomitant deletion of TET2 and TET3 (35). This hypermethylation observed in the absence of TET2 and TET3 could suggest that, in T-cells, TET proteins might compete with DNMTs in order to maintain an optimal methylation status that can be reversible if environmental cues or the cytokine milieu induce gene expression.

5. TET PROTEINS IN iNKT CELL LYMPHOMA

Given the fact that Tet2/3 DKO iNKT cells showed increased proliferative capacity and high expression of stemness genes, we asked if these cells could expand under the control of an intact, fully functional immune system. To address this question, Tet2/3 DKO iNKT cells were transferred to non-irradiated wild type congenic recipients. Our results revealed that Tet2/3 DKO iNKT cells could mediate an iNKT cell lymphoma upon transfer to non-irradiated recipients (35) (Table 1). There have been reports of iNKT TCR-dependent lymphoma in mice that exhibit mutations in p53 (50) as well as Id2 and Id3 (51). Notably, adoptive transfer of sorted Tet2/3 DKO iNKT cells to Cd1dKO mice—that do not express CD1d and fail to present antigens to iNKT cells—cannot recapitulate the expansion, confirming that the iNKT cell lymphoma is TCR-dependent.

The Tet2/3 DKO iNKTs that have been transformed and dramatically expanded in congenic recipients show a striking accumulation of DNA breaks and R-loops (52). Gene expression analysis by RNA-seq showed that the expanded Tet2/3 DKO iNKT cells upregulated the expression of proto-oncogenes such as Myc and Lmo4 (35). In addition, multiple genes involved in the cell cycle as well as DNA repair were highly expressed (35). Our DNA methylation analysis by WGBS did not reveal differences in the methylation status of these genes (35). It remains unclear if the genes that show increased expression in the Tet2/3 DKO iNKT cells are suppressed by TET proteins under physiological conditions, potentially in a catalytic-independent manner, or if TET proteins regulate the expression of other factors that in turn can suppress the expression of genes that promote tumorigenesis.

6. PERSPECTIVES

6.1. Focal activity of TET proteins and cell-specific gene expression

Studies conducted in murine immune cells established that lack of TET proteins does not result in global DNA hypermethylation (35, 53, 54). Instead, TET proteins exert a focal impact in the DNA methylation status at specific genomic loci during development to establish cell lineage identity (35). These findings agree with a previous report that evaluated 42 whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) datasets across 30 human cells and tissue types (55). The analysis of these datasets revealed that during development, dynamic changes in the methylation status occur at only 21.8% of autosomal CpGs, mainly in loci distant from the transcription start site (TSS) (55). Notably, Tet2/3 DKO iNKT cells exhibited DNA hyper-methylation even in CpGs that were already highly methylated in the wild type counterparts (35). Presumably, TET proteins might compete with DNMTs to prevent aberrant hypermethylation (35, 56). Establishing an optimal threshold of DNA methylation might maintain the enhancers in a poised state. As a result, based on specific environmental cues or cell interactions, poised genes might be rapidly turned on to govern subsequent differentiation steps.

6.2. Recruitment of TET proteins by Transcription Factors

The focal activity of TET proteins suggests that TET proteins are targeted and recruited to specific genomic loci by interacting with cell-specific transcription factors. TET proteins exhibit cell type-specific binding patterns and affect chromatin accessibility. Importantly, enrichment of 5hmC correlates with open chromatin conformation and increased chromatin accessibility in various immune cell types, including T-cells and B cells (35, 57). Thus, it is possible that TET proteins might be recruited by pioneer factors and act in concert to open chromatin and demethylate DNA. Recent studies reveal that different genomic loci exhibit varying sequences of epigenetic reorganization in order to govern gene expression. Specifically, during both trans-differentiation of B cells to macrophages and reprogramming, it was established that some genomic loci first show changes in chromatin and then show altered methylation, some loci exhibit simultaneous alterations of chromatin and DNA methylation, and some undergo methylation changes prior to chromatin rearrangements, although less frequently (58). However, in all these cases, TET proteins interact with pioneer transcription factors and subsequently impact the binding of transcription factors to regulatory elements such as enhancers (59). Similar findings have been reported in regulatory T cells (Tregs), where members of the STAT family recruit TET proteins at enhancers (60). In B cells, PU.1, EBF1, and BATF interact with TET proteins (57, 61). Overall, locus-specific recruitment of TET proteins might be facilitated through direct interaction with transcription factors.

To gain full appreciation of the TET-mediated regulatory functions, it is critical to identify TET interacting partners across different immune cell types. These interacting partners mediate the recruitment of TET proteins in the DNA and facilitate the suppression or promotion of gene expression in a context-dependent manner. In addition, identifying TET interacting partners will shed light on pioneer factors that are crucial for opening chromatin and rendering specific genomic loci accessible during T-cell lineage commitment or iNKT cell lineage specification. The identification of the cell-specific TET-interactome has been hindered so far due to technical challenges. TET proteins are expressed at low levels and they have a high molecular weight rendering the identification of endogenous protein interactions very difficult. To circumvent these issues, the approach to express tagged TET proteins in cells has been used and has provided mechanistic insights on how TET proteins can potentially be recruited to the DNA and mediate catalytic-dependent (62) or catalytic-independent functions (63). Generating mice that express tagged TET proteins should allow us to gain further understanding of the TET-interactome in cell types that are challenging to culture and expand in vitro.

6.3. TET proteins in establishment and maintenance of T-cell fate

TET proteins in various immune cell types are instrumental in ensuring proper maturation and cell fate establishment (18). TET proteins, by oxidizing 5mC to 5hmC, turn on the expression of lineage specifying transcription factors that govern cell differentiation (13). Indeed, Zbtb7b and Tbx21, which encode for the key lineage-specifying factors of T-cell differentiation—ThPOK and RUNX3, respectively—show maximum 5hmC deposition in the gene body specifically at the stage where their expression is turned on. Then, 5hmC levels are gradually diminished as the cell identity is established (13). Tet2-deficient CD8 T-cells acquire memory fate in a murine model of viral infection and show hypermethylation of genes promoting effector-cell fate (64). It has been reported that murine TET2-deficient T-cells show impaired differentiation in vitro towards helper lineages, such as Th1 and Th17 [117], and a marked reduction in cytokine secretion, including IFNγ and IL-10 [117] (Table 1). In vitro polarization of human, naïve CD4 T-cells towards helper lineages demonstrates that DNA demethylation and 5hmC remodeling across the genome occur early after activation and before any differentiation [88, 116t]. In T-cell polarization cultures, 5hmC has been reported to be critical for the initial step of the specification to helper lineages but is not required during the expansion phase [88]. Thus, TET proteins and 5hmC might play an instrumental role to initiate gene expression of key genes during the establishment of cell fate, but might not be required during activation and proliferation of cells.

An additional layer of developmental regulation is the maintenance of a stable cell fate (Table 1). TET proteins appear to exert a critical role in maintaining stable gene expression of key lineage-specifying function, as well as preventing the de-differentiation of cells and the acquisition of aberrant identity. A notable example of this is the role of TET proteins in preventing the methylation of regulatory elements to prevent the silencing of Foxp3, which makes TET proteins and 5hmC instrumental in the maintenance of regulatory T-cell (Treg) identity. Consistent with this, Tet2-deficient mice exhibit reduced numbers of Tregs (65). Moreover, concomitant deletion of TET1 and TET2 significantly reduces the abundance of Tregs due to defective demethylation of the CNS2 locus of FOXP3, and notably, TET1 and TET2 directly associate with CNS2 (60). In a similar vein, simultaneous loss of TET2 and TET3 at the DP cell stage using CD4-cre mice exerts a more severe impact on the stability of Foxp3 expression due to aberrant methylation of the CNS2 locus (66). Deleting TET2 and TET3 specifically at Tregs using Foxp3-cre mice not only compromises the stability of the Treg lineage, but it also results in gain of effector fate function and aberrant hyperactivation of the Tet2/3-deficient Tregs (Table 1) (67, 68). The stable expression of FOXP3 requires the cytosine de-methylation of the CNS2 intronic enhancer, which is actively regulated by all three TET proteins. Whether TET proteins can control the stability of other transcription factors in immune cell development remains to be explored.

It has also been shown that TET1 and TET3 can act in concert during thymic development to control the methylation status of enhancers that regulate Cd4 gene expression in the periphery (69). This observation suggests that 5hmC deposition can mark enhancers for maintenance in an open state to control gene expression at subsequent developmental stages. Per analogy, the dynamic distribution of 5hmC in highly expressed genes during T-cell lineage specification (13) could potentially be involved in priming enhancers that will become fully activated and induce gene expression later in development.

6.5. TET proteins as tumor suppressors

Tet2 is the second most frequently mutated gene in hematological malignancies, and Tet2 mutations are strongly associated with myelodysplastic syndromes, myeloproliferative neoplasms, and myeloid leukemias (30, 70). In addition, Tet2 mutations have been reported in cases of Peripheral T- cell Lymphoma not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS)(71) and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL)(72). Tet2 mutations are widely considered an early event in the process of malignant transformation that provides proliferative advantage to the mutated cells; however, a secondary hit is required for the cells to become tumorigenic and ultimately malignant (73).

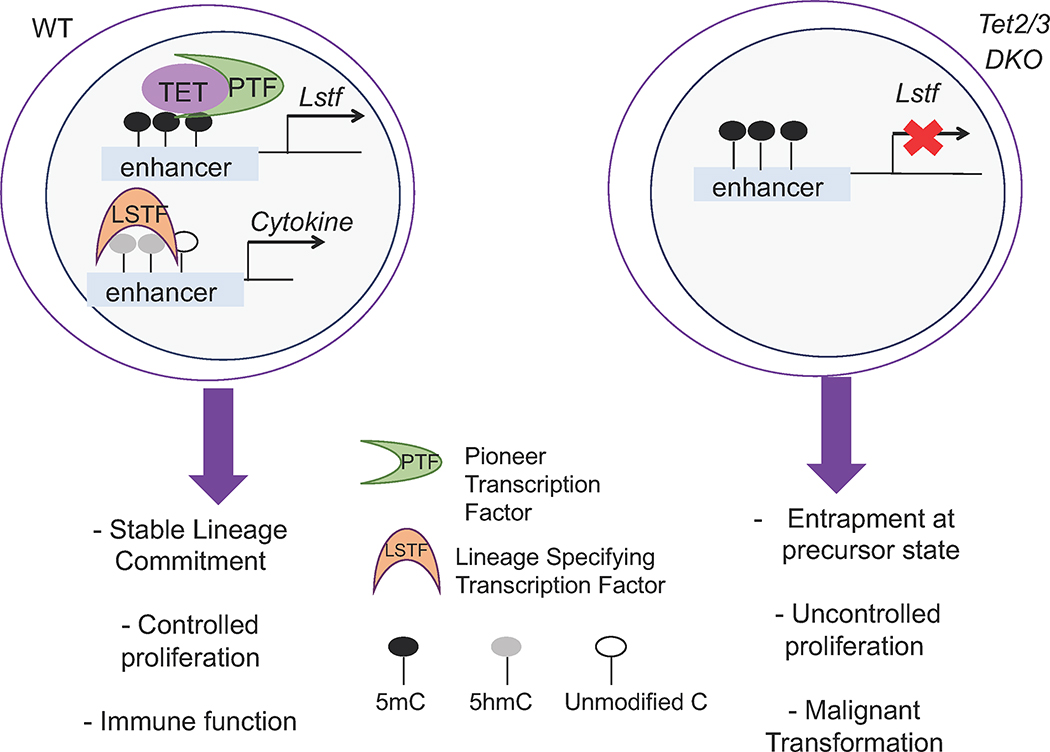

The precise mechanisms that link TET loss to cancer remain obscure. Loss of TET proteins results in aberrant development, entrapment in precursor cell stages, and uncontrolled proliferation (35, 53, 57, 74). Analysis of TET mutant mice revealed that upon TET loss, the cell-specific lineage-specification program fails to be launched. Instead, a stemness gene expression program is prolonged, resulting in malignant transformation (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Model for TET proteins & malignant transformation.

Under physiological conditions, TET proteins control DNA demethylation and ensure proper acquisition of cell fate. The stable commitment and maturation of cells allows proper function and controlled proliferation. In the absence of TET proteins, cells fail to acquire their identity. Instead, they are trapped in a progenitor state characterized by expression of stemness genes, hyperproliferation, and ultimately malignant transformation.

An additional mechanism by which TET proteins could exert their tumor suppressive function is by maintaining genomic integrity. It has been reported that 5hmC is enriched at genomic sites of drug-induced DNA damage as well as in cancer cell lines (75). TET1 loss of function in primordial germ cells (PGCs) reduces the expression of genes that regulate chromosomal meiosis and disrupts synapsis formation (76). As a result, there is increased occurrence of double-strand breaks (DSBs) and appearance of univalent chromosomes (76). An increase in DSBs was also observed in pro-B cells that lack TET1 (53), in HSCs that concomitantly lack TET2 and TET3 (54), and in TET2/3 DKO iNKT cells (35). It has been suggested that TET2 is recruited at sites of DNA damage (75). To what extent TET proteins directly regulate DNA repair in T-cells and other immune cells remains unknown.

Genetically modified mice with ablations in Tet genes develop hematopoietic malignancies; TET1 loss results in B cell malignancy in aging mice (53), whereas loss of TET2 results mainly in myeloid leukemias (77). Interestingly, aging Tet2-deficient mice develop B cell malignancies with striking similarities to human chronic lymphocytic leukemia (78). Concomitant deletion of Tet1 and Tet2 in mice results in the emergence of B cell malignancies (79). Inducible deletion of Tet2 and Tet3 results in aggressive myeloid leukemia (54). Also, in mice that lack only one of the TET proteins, cancer emergence is a slow process that can take years to manifest (53, 80). However, concomitant deletion of both or all the members of the TET family results in aggressive malignant transformation of various immune cell types (35, 54, 57, 79). Thus, enhancing the activity of TET proteins is a possibility with therapeutic potential.

6.6. Enhancing TET activity by using vitamin C

Vitamin C has been reported to enhance TET catalytic activity, resulting in increased DNA demethylation in various cell types such as ESCs (81) and Tregs (82),(83),(84). Under physiological conditions, ascorbate (vitamin C) was one of the most enriched metabolites in HSCs and Multipotent Progenitors (MPPs)(85). One of the functions of ascorbate in HSCs was to promote TET2 activity in vivo, controlling thus the proliferation of HSCs and inhibiting leukemogenesis (85). In addition, Tet2-deficient HSCs cultured in vitro in the presence of vitamin C exhibit increased levels of 5hmC (86). This unexpected increase of 5hmC was attributed to enhanced enzymatic activity of TET3 and was sufficient to limit aberrant cell expansion (86). Moreover, in vivo treatment of mice with vitamin C in xenograft experiments could limit the hyperproliferation of Tet2 KO HSCs (86). Vitamin C promotes TET catalytic activity and enhances DNA hypomethylation (84, 87). In hematological malignancies, TET2 is most frequently mutated. Thus, vitamin C could be exploited as pharmacological agent to treat blood cancers with Tet2 mutations to promote the catalytic activity of the remaining TET proteins and restore normal levels of 5hmC.

6.7. TET proteins: functional redundancy and potential unique functions

Studies using genetically modified mouse models provide evidence that TET proteins play redundant roles (18). Deletion of only one of the members of the TET family has minor—if any—effects on immune cell development (35, 57, 88–90). TET proteins appear to play a complementary role in DNA demethylation of enhancers and expression of lineage-specifying transcription factors that then execute their cell-specific gene expression program (60, 61). Even though TET functional redundancy is well established, we cannot exclude unique functions. In immune cells, TET2 and TET3 are the most highly expressed among the three TET proteins (27, 30). Technical challenges due to lack of ChIP-grade antibodies have precluded efforts to decipher the specific DNA recruitment patterns for TET2 and TET3.

In addition, it remains elusive if both TET2 and TET3 are recruited simultaneously and act in concert or, if by interacting with different transcription factors with distinct affinity, they each can exert a unique impact on regulating gene expression. In the second scenario, loss of expression of one TET protein could allow the remaining expressed TET protein to form complexes with transcription factors that would not have interacted under normal conditions. In this setting, the remaining TET protein would assume novel roles and exert compensatory functions. To shed light on this possibility, it will be informative to generate TET dominant negative mice where the TET protein of interest would still be expressed and maintain its interactome, while its catalytic activity would be compromised.

Another intriguing possibility, not mutually exclusive to the above, is that TET proteins could be recruited to the same genomic loci but with different affinity for distinct oxi-mCs. For instance, in ESCs, TET1 is initially recruited to DNA where it oxidizes 5mC to 5hmC (62). Subsequently, SALL4 specifically recognizes 5hmC and recruits TET2 to further oxidize 5hmC to 5fC and 5caC (62). In immune cells, it would be attractive to postulate that TET3 (which exhibits higher structural similarity with TET1) could mediate the first oxidization step to convert 5mC to 5hmC. Then, specific transcription factors with high affinity for 5hmC could recruit TET2 to complete the process of 5hmC oxidization in order to generate other oxi-mCs. The newly generated oxi-mCs could attract specific readers. Despite the extensive research in the field within the last 10 years, the precise steps of the TET choreography that finely tune gene expression remain elusive. Elegant biochemical experiments are required to elucidate the shared and unique functions of TET proteins.

6.8. TET proteins and catalytic-independent functions

Recent evidence using TET-deficient mice has revealed phenotypes that cannot be explained merely by the observed alterations in DNA methylation, suggesting a pleiotropic mode of function for the TET family of proteins (17–19, 35, 90). It is crucial to uncover the causal links that connect TET loss with the observed phenotypes and distinguish them from the secondary events that are the outcome of altered gene expression of key transcription factors. Notably, differential gene expression in TET-deficient immune cells has revealed similar numbers of both upregulated and downregulated genes. Presumably, TET proteins can fine-tune gene expression in an enzymatically-independent manner by forming protein complexes that could impact gene expression. Thus, deciphering the TET interactome in immune cells will reveal novel, unexpected roles of TET proteins.

Indeed, a recent report compared TET2 null mice with TET2 mutant mice expressing full length TET2 with point mutations in the catalytic domain that compromise iron binding and impair TET enzymatic activity (91). TET2 catalytically inactive mice develop mainly myeloid malignancies whereas TET2 null mice exhibit both myeloid and lymphoid leukemias (91). These data suggest TET2 might exert additional, catalytic-independent functions to prevent malignant transformation of lymphoid cells. This scenario is in accordance with the fact that mutations of TET2 and isocitrate dehydrogenase 1/2 (IDH1/2) are mutually exclusive in myeloid malignancies (92), whereas TET2 and IDH2 mutations co-occur in certain cases of peripheral T-cell lymphomas (72), suggesting distinct mechanisms of tumorigenesis across different immune cell types.

Along these lines, we hypothesize that TET1 and TET3 can also play additional enzymatic-independent functions in immune cell differentiation, function, and malignant transformation. This hypothesis is based upon observations in other cell types, primarily in ES cells where multiple studies have taken place. In this context, TET1 interacts with SIN3A to suppress gene expression in a catalytic-independent manner (93). Similarly, TET1 can interact with Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) in mouse ESCs (94). TET2, through interaction with HDAC2, suppresses IL-6 secretion in macrophages treated with LPS in a catalytic-independent manner (63). Overall, these findings suggest that TET proteins form complexes with transcriptional regulators to promote or inhibit transcription in a catalytic-independent manner. Further experiments using mice that express full length TET proteins with impaired enzymatic activity in T-cells will dissect which of the observed phenotypes are due to the DNA demethylation activity of TET proteins and which can be attributed to catalytic independent functions.

6.9. Identifying potential enhancers and validating their regulatory function

Our research has revealed that the vast majority of the differentially methylated regions (DMRS) and the DARs that were identified in Tet2/3 DKO iNKT cells were far from the TSS and presumably were distal regulatory elements (35). Similar findings were reported in other cell types such as B cells and Tregs (61, 67). The combined analysis of the generated ATAC-seq datasets and ChIP-seq datasets for histone modifications allow us to distinguish which of these accessible regions can be potential active enhancers (enrichment for H3K27Ac) (34).

Importantly, loss of DNA methylation and gain of 5hmC in regulatory regions further suggests that these regions can be potentially active enhancers (13, 95). As enhancers can regulate genes from a great genomic distance, it is challenging to assess the genes that are directly impacted by loss of TET proteins (35). Various methods, such as Hi-C (96, 97), Chromatin Interaction Analysis by Paired-End Tag Sequencing (ChiA-PET) (98), and HiChIP (99), have been developed in recent years in order to assess genome-wide topological associations. The precise identification of genes that are regulated by TET proteins will determine the causal relationships between TET protein loss and the observed phenotypes across various immune systems. However, extensive deep sequencing is required to obtain meaningful datasets, rendering this approach quite expensive. In addition, the small numbers of primary cells that can be retrieved renders the broad use of these methodologies challenging. Recently, development and optimization of protocols enabled the adaptation of these methodologies using small numbers of primary immune cells, such as T-cells, hematopoietic stem cells, erythroid progenitor cells, and B cells during development and disease (100–104). These novel technologies permit us to interrogate how loss of TET proteins and 5hmC impacts higher-order chromatin structures in the context of lineage specification, lineage fidelity and malignant transformation of immune cells. In addition, we will identify the genes that are regulated by TET-activated, cell specific enhancers.

After linking potential enhancers to genes that they might regulate, the next step is to validate if these enhancers are critical for gene expression. To this end, genome editing technologies such as clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 can be used (105). CRISPR/Cas9 introduces double-strand breaks in target DNA sequences defined by sequence complementary guide RNAs (106) to specifically induce deletion of conserved cis-regulatory elements, allowing evaluation of their impact in vivo.

In addition, epigenome editing approaches will allow for the specific activation or inactivation of regulatory elements to dissect the contributions for the epigenetic modifications in fine-tuning gene expression. This approach can establish a causal link between specific epigenetic alterations and differential gene expression. The epigenome editing can be achieved by using catalytically inactive, dead dCas9, which cannot cleave the DNA but can still be effectively guided to the target sequence fused with catalytic domains of epigenetic modifiers (107, 108). This will allow specific targeting at loci of different epigenetic modifiers: TET proteins (to induce DNA demethylation), the transcriptional co-activator p300, lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1), and DNMT3a (109–112). This method has been successfully used to investigate how epigenetic reprogramming of the CNS locus can affect the expression of Foxp3 and thus the biology of Tregs (113). This approach can provide novel insights on epigenetic regulation and dissect, for a given enhancer, if deposition of active histone marks (such as H3K27AC, the product of p300 activity) or TET-mediated 5hmC enrichment and DNA demethylation can drive gene expression. Efficient delivery of epigenome editing tools in primary cells can be challenging but tremendous progress has been made in recent years with these approaches in primary T cells that can be cultured in vitro (114). However, a point to consider is the stability of the induced epigenetic modifications using genome editing tools.

6.10. Identifying oxi-mCs at single nucleotide resolution

The discovery that TET proteins oxidize 5mC to generate 5hmC (9) and other oxidized mCs (10) (11) led to an explosion of information, development of novel techniques, and genetic tools to decipher the function of the oxi-mCs and TET proteins (115) (Table 2). Numerous studies have emerged that shed light upon the distribution of 5hmC across the genome, both in human and murine T-cells (35, 116, 117) as well as other immune cell types (18). Tremendous progress in high throughput sequencing technologies made feasible the study of rare immune populations. Establishment and implementation of efficient protocols has minimized the amount of the required starting material and this has revolutionized our understanding of molecular processes in minute subpopulations ex vivo.

Table 2.

Next generation sequencing technologies for mC & oxi-mC detection

| Technique | Information | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | -Single nucleotide resolution method that was introduced to identify 5mC versus unmodified C. -It cannot distinguish 5mC from other modified cytosines (5hmC, 5fC, 5caC). |

7 |

| 5hmC-Immunoprecipitation (IP) | -Enrichment method -DNA immunoprecipitation of genomic fragments that contain 5hmC using an antibody |

93, 119, 120, |

| anti-cytosine-5-methylenesulfonate(CMS)-IP | -Enrichment method allows the identification of genomic regions that are enriched for 5hmC - bisulfite treatment of DNA converts 5hmC to CMS followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-CMS |

121 |

| Glucosylation, Periodate Oxidation and Biotinylation (GLIB) | Enrichment method relying on a combination of enzymatic and chemical modification steps result in biotinylation of 5hmC followed by streptavidin pulldown. | 123 |

| 5-hmC-seal | Glucosylation and biotinylation of 5hmC followed by streptavidin pulldown and sequencing | 124 |

| Nano-5hmC-seal | Adaptation of 5-hmC-Seal method to limited starting material | 125 |

| 5fC-IP and 5caC-IP | Enrichment method allowing the immunoprecipitation of DNA fragments containing 5fC or 5caC using antibodies | 131 |

| 5fC-Seal | Selective chemical labeling and capture of 5fC | 133 |

| Oxidative bisulfite sequencing (OxBS-seq) | Single base nucleotide resolution method | 126,127 |

| Tet-assisted bisulfite sequencing (TAB-Seq) | Single base resolution mapping of 5hmC | 128, 129 |

| APOBEC-Coupled Epigenetic Sequencing (ACE-seq) | Single base resolution mapping of 5hmC, without use of bisulfite treatment | 130 |

| Chemically assisted bisulfite sequencing for the detection of 5fC (fCAB-seq) | Single nucleotide resolution 5fC detection | 133 |

| Methyl- Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) | Simultaneous assessment of changes in chromatin accessibility & DNA methylation | 136 |

| EpiMethylTag | Simultaneous detection of ATAC-seq or ChIP-seq signals and DNA methylation | 135 |

| ATAC-me | Simultaneous evalution of chromatin accessibility and DNA methylation | 137 |

The “gold standard” approach for identifying 5mC at single nucleotide resolution is WGBS (7), which relies on sodium bisulfite (NaHSO3) treatment of genomic DNA. Notably, this approach cannot distinguish 5mC from 5hmC (118). Both 5mC and 5hmC are resistant to deamination when treated with NaHSO3, and after PCR amplification they are read as C. But 5fC, 5caC and unmodified C upon NaHSO3 treatment are deaminated and converted to uracil (U), which after PCR amplification is converted to thymidine (T). Various methods were developed to allow 5hmC identification. First, non-base resolution methods that are based on enrichment of modified oxi-mCs were used (Table 2). 5hmC (93, 119, 120) can be specifically identified by antibodies in DNA-immunoprecipitation experiments, followed by next generation sequencing of the enriched regions. Other enrichment methods, such as bisulfite conversion of 5hmC to cytosine 5-methylenesulfonate (CMS), followed by immunoprecipitation and sequencing (121, 122), glucosylation, periodate oxidation and biotinylation sequencing (GLIB) (122, 123) and selective chemical labeling (hMe-Seal (124) and nano-5hmC-seal(125)) have been developed. Overall, these enrichment approaches capture genomic fragments that contain 5hmC but cannot provide information regarding the precise location of 5hmC across the genome.

The need to decipher the distribution of 5hmC at single base resolution gave rise to techniques such as oxidative bisulfite sequencing (ox-BS) (126, 127) that relies on chemical treatment of the DNA with potassium perruthenate (KRuO4). Subsequent bisulfite treatment allows the precise quantification and distinction of 5mC and 5hmC across the genome. KRuO4 oxidizes 5hmC to 5fC, which after PCR is read as T. So, in ox-BS, only 5mC will be read as C. In this approach, determining the precise location of 5hmC across the genome is achieved by subtracting signals of ox-BS-seq from those of conventional BS-seq (126).

An additional method, TET-assisted bisulfite sequencing (TAB-seq), (128, 129) uses a combination of enzymatic and bisulfite treatments of the DNA to distinguish 5mC from 5hmC at single nucleotide resolution. Both methods were revolutionary and provided the first insights on the distribution of 5mC and 5hmC across the genome with unprecedented accuracy. However, there were also some inherent caveats: potassium perruthenate and sodium bisulfite treatment are harsh processes that damage the DNA and result in significant loss of starting material, rendering the application of these methods challenging when using small numbers of cells.

Moving forward, the field requires the development of methodologies that will be applicable with limited starting material, which is frequently the case when working with primary cells. This need has been met with the nano-5hmC-seal (125). However, it is also important to distinguish 5hmC at single nucleotide resolution. A method that efficiently combines single nucleotide resolution and non-destructive treatment of the DNA is APOBEC-Coupled Epigenetic Sequencing (ACE-seq) (130). The ultimate challenge is to measure 5hmC at the single-cell level. In immune cells, there is still a gap in our knowledge regarding the distribution and the potential roles of the other oxi-mCs, 5fC and 5caC. Their rare frequency in combination with the small numbers of primary cells able to be purified during experiments renders this mission quite challenging. The development of antibodies that can specifically recognize 5fC or 5caC have shed light on their enrichment in mouse ESCs (131, 132). Selective chemical labeling has allowed the enrichment of fragments containing fC (fC-Seal)(133). Single-nucleotide resolution approaches have also been developed (132, 134). These novel, bisulfite-free methods do not damage the DNA yielding robust data even for limited starting material. Moreover, distinguishing the localization of distinct oxi-mCs across the genome in immune cells will shed light to their precise regulatory roles in gene expression and DNA repair.

Importantly, we cannot disregard that the oxi-mCs act in concert with additional epigenetic modifications to regulate gene expression. Thus, it is imperative to develop methodologies to dissect the concurrent, dynamic changes of the epigenome (Table 2). Towards this direction, in the last two years we have witnessed the development of techniques that allow the simultaneous detection of alterations in chromatin accessibility and DNA methylation: EpiMethylTag (135), Methyl-ATAC-seq (136) and ATAC-me (137). However, changes in chromatin accessibility are frequently associated with changes in 5hmC (18, 35, 57). Thus, incorporating the identification of 5hmC into the above methods would allow a more accurate depiction of cytosine modification status as the chromatin accessibility changes during development or as a response to environmental stimuli.

7. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

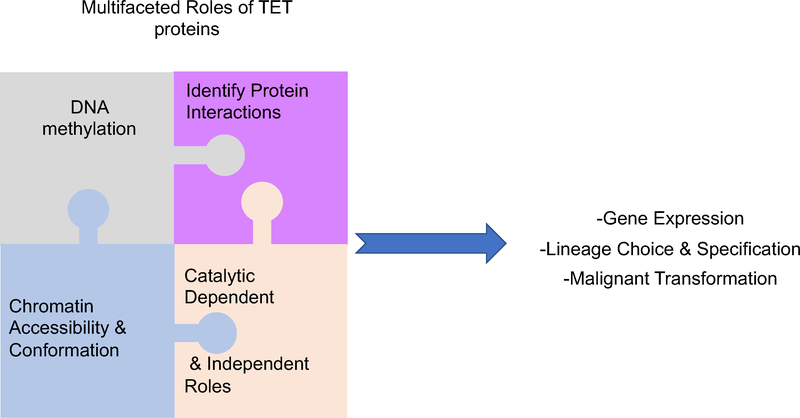

Despite the plethora of scientific discoveries related to the biology of TET proteins in the past decade, the precise mechanisms of TET functions remain elusive. This is attributed in part to the complexity of emerging phenotypes upon TET loss and the technical challenges that hinder the detailed investigation of the individual role played by each TET protein. As we move forward, it is critical to take advantage of novel techniques to decipher the TET interactome, understand TET-mediated functions that extend beyond DNA demethylation, and appreciate TET’s impact on chromatin accessibility (Fig. 7). This knowledge will allow to identify the mechanisms that establish and maintain T-cell identity in an irreversible manner, preventing lineage infidelity and acquisition of aberrant, hyperproliferative phenotypes that result in hematological malignancies and oncogenic transformation.

Figure 7: Multifaceted roles of TET proteins.

It is established that TET proteins through their enzymatic activity regulate DNA demethylation. To fully understand their impact on gene expression and ultimately on the establishment of cell identity, we need to put together different pieces of the puzzle: A) Which are the factors that interact with TET proteins and recruit them to the DNA? B) What are the catalytic-independent functions of TET proteins? C) How and where across the genome do TET proteins impact chromatin accessibility?

Acknowledgments

Funding

AT is supported by University of North Carolina (UNC) Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (LCCC) startup fund, National Institute of Health grant R35 GM138289 (National Institute of General Medical Sciences) and IBM Junior Faculty Development Award.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Allis CD, Jenuwein T. The molecular hallmarks of epigenetic control. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17(8):487–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonasio R, Tu S, Reinberg D. Molecular signals of epigenetic states. Science. 2010;330(6004):612–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou VW, Goren A, Bernstein BE. Charting histone modifications and the functional organization of mammalian genomes. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(1):7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pastor WA, Aravind L, Rao A. TETonic shift: biological roles of TET proteins in DNA demethylation and transcription. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14(6):341–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith ZD, Meissner A. DNA methylation: roles in mammalian development. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14(3):204–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goll MG, Bestor TH. Eukaryotic cytosine methyltransferases. Annual review of biochemistry. 2005;74:481–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lister R, Pelizzola M, Dowen RH, Hawkins RD, Hon G, Tonti-Filippini J, et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;462(7271):315–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurent L, Wong E, Li G, Huynh T, Tsirigos A, Ong CT, et al. Dynamic changes in the human methylome during differentiation. Genome research. 2010;20(3):320–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324(5929):930–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito S, Shen L, Dai Q, Wu SC, Collins LB, Swenberg JA, et al. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science. 2011;333(6047):1300–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He YF, Li BZ, Li Z, Liu P, Wang Y, Tang Q, et al. Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science. 2011;333(6047):1303–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cortellino S, Xu J, Sannai M, Moore R, Caretti E, Cigliano A, et al. Thymine DNA glycosylase is essential for active DNA demethylation by linked deamination-base excision repair. Cell. 2011;146(1):67–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsagaratou A, Aijo T, Lio CW, Yue X, Huang Y, Jacobsen SE, et al. Dissecting the dynamic changes of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in T-cell development and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(32):E3306–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nestor CE, Ottaviano R, Reinhardt D, Cruickshanks HA, Mjoseng HK, McPherson RC, et al. Rapid reprogramming of epigenetic and transcriptional profiles in mammalian culture systems. Genome Biol. 2015;16:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mellen M, Ayata P, Dewell S, Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. MeCP2 binds to 5hmC enriched within active genes and accessible chromatin in the nervous system. Cell. 2012;151(7):1417–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spruijt CG, Gnerlich F, Smits AH, Pfaffeneder T, Jansen PW, Bauer C, et al. Dynamic readers for 5-(hydroxy)methylcytosine and its oxidized derivatives. Cell. 2013;152(5):1146–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cimmino L, Aifantis I. Alternative roles for oxidized mCs and TETs. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2017;42:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsagaratou A, Lio CJ, Yue X, Rao A. TET Methylcytosine Oxidases in T Cell and B Cell Development and Function. Front Immunol. 2017;8:220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu X, Zhang Y. TET-mediated active DNA demethylation: mechanism, function and beyond. Nature reviews Genetics. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito S, D’Alessio AC, Taranova OV, Hong K, Sowers LC, Zhang Y. Role of Tet proteins in 5mC to 5hmC conversion, ES-cell self-renewal and inner cell mass specification. Nature. 2010;466(7310):1129–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu L, Li Z, Cheng J, Rao Q, Gong W, Liu M, et al. Crystal Structure of TET2-DNA Complex: Insight into TET-Mediated 5mC Oxidation. Cell. 2013;155(7):1545–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu Y, Wu F, Tan L, Kong L, Xiong L, Deng J, et al. Genome-wide regulation of 5hmC, 5mC, and gene expression by Tet1 hydroxylase in mouse embryonic stem cells. Molecular cell. 2011;42(4):451–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin C, Lu Y, Jelinek J, Liang S, Estecio MR, Barton MC, et al. TET1 is a maintenance DNA demethylase that prevents methylation spreading in differentiated cells. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42(11):6956–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin SG, Zhang ZM, Dunwell TL, Harter MR, Wu X, Johnson J, et al. Tet3 Reads 5-Carboxylcytosine through Its CXXC Domain and Is a Potential Guardian against Neurodegeneration. Cell reports. 2016;14(3):493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iyer LM, Tahiliani M, Rao A, Aravind L. Prediction of novel families of enzymes involved in oxidative and other complex modifications of bases in nucleic acids. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(11):1698–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ko M, An J, Bandukwala HS, Chavez L, Aijo T, Pastor WA, et al. Modulation of TET2 expression and 5-methylcytosine oxidation by the CXXC domain protein IDAX. Nature. 2013;497(7447):122–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsagaratou A, Rao A. TET Proteins and 5-Methylcytosine Oxidation in the Immune System. Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koh KP, Yabuuchi A, Rao S, Huang Y, Cunniff K, Nardone J, et al. Tet1 and Tet2 regulate 5-hydroxymethylcytosine production and cell lineage specification in mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell stem cell. 2011;8(2):200–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu TP, Guo F, Yang H, Wu HP, Xu GF, Liu W, et al. The role of Tet3 DNA dioxygenase in epigenetic reprogramming by oocytes. Nature. 2011;477(7366):606–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ko M, Huang Y, Jankowska AM, Pape UJ, Tahiliani M, Bandukwala HS, et al. Impaired hydroxylation of 5-methylcytosine in myeloid cancers with mutant TET2. Nature. 2010;468(7325):839–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain. Science. 2009;324(5929):929–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu L, Lu J, Cheng J, Rao Q, Li Z, Hou H, et al. Structural insight into substrate preference for TET-mediated oxidation. Nature. 2015;527(7576):118–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen Y, Yue F, McCleary DF, Ye Z, Edsall L, Kuan S, et al. A map of the cis-regulatory sequences in the mouse genome. Nature. 2012;488(7409):116–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Creyghton MP, Cheng AW, Welstead GG, Kooistra T, Carey BW, Steine EJ, et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(50):21931–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsagaratou A, Gonzalez-Avalos E, Rautio S, Scott-Browne JP, Togher S, Pastor WA, et al. TET proteins regulate the lineage specification and TCR-mediated expansion of iNKT cells. Nature immunology. 2017;18(1):45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bachman M, Uribe-Lewis S, Yang X, Williams M, Murrell A, Balasubramanian S. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine is a predominantly stable DNA modification. Nat Chem. 2014;6(12):1049–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsagaratou A TET mediated epigenetic regulation of iNKT cell lineage fate choice and function. Mol Immunol. 2018;101:564–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pereira RM, Martinez GJ, Engel I, Cruz-Guilloty F, Barboza BA, Tsagaratou A, et al. Jarid2 is induced by TCR signalling and controls iNKT cell maturation. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dobenecker MW, Kim JK, Marcello J, Fang TC, Prinjha R, Bosselut R, et al. Coupling of T cell receptor specificity to natural killer T cell development by bivalent histone H3 methylation. J Exp Med. 2015;212(3):297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beyaz S, Kim JH, Pinello L, Xifaras ME, Hu Y, Huang J, et al. The histone demethylase UTX regulates the lineage-specific epigenetic program of invariant natural killer T cells. Nat Immunol. 2017;18(2):184–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Northrup D, Yagi R, Cui K, Proctor WR, Wang C, Placek K, et al. Histone demethylases UTX and JMJD3 are required for NKT cell development in mice. Cell Biosci. 2017;7:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:297–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Engel I, Kronenberg M. Making memory at birth: understanding the differentiation of natural killer T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(2):184–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee YJ, Holzapfel KL, Zhu J, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Steady-state production of IL-4 modulates immunity in mouse strains and is determined by lineage diversity of iNKT cells. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(11):1146–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Constantinides MG, Bendelac A. Transcriptional regulation of the NKT cell lineage. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25(2):161–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsagaratou A Unveiling the regulation of NKT17 cell differentiation and function. Mol Immunol. 2019;105:55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee PP, Fitzpatrick DR, Beard C, Jessup HK, Lehar S, Makar KW, et al. A critical role for Dnmt1 and DNA methylation in T cell development, function, and survival. Immunity. 2001;15(5):763–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carr T, Krishnamoorthy V, Yu S, Xue HH, Kee BL, Verykokakis M. The transcription factor lymphoid enhancer factor 1 controls invariant natural killer T cell expansion and Th2-type effector differentiation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2015;212(5):793–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, Chang HY, Greenleaf WJ. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods. 2013;10(12):1213–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bachy E, Urb M, Chandra S, Robinot R, Bricard G, de Bernard S, et al. CD1d-restricted peripheral T cell lymphoma in mice and humans. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2016;213(5):841–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li J, Roy S, Kim YM, Li S, Zhang B, Love C, et al. Id2 Collaborates with Id3 To Suppress Invariant NKT and Innate-like Tumors. Journal of immunology. 2017;198(8):3136–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lopez-Moyado IF, Tsagaratou A, Yuita H, Seo H, Delatte B, Heinz S, et al. Paradoxical association of TET loss of function with genome-wide DNA hypomethylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(34):16933–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cimmino L, Dawlaty MM, Ndiaye-Lobry D, Yap YS, Bakogianni S, Yu Y, et al. TET1 is a tumor suppressor of hematopoietic malignancy. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(6):653–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.An J, Gonzalez-Avalos E, Chawla A, Jeong M, Lopez-Moyado IF, Li W, et al. Acute loss of TET function results in aggressive myeloid cancer in mice. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ziller MJ, Gu H, Muller F, Donaghey J, Tsai LT, Kohlbacher O, et al. Charting a dynamic DNA methylation landscape of the human genome. Nature. 2013;500(7463):477–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parry A, Rulands S, Reik W. Active turnover of DNA methylation during cell fate decisions. Nat Rev Genet. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lio CW, Zhang J, Gonzalez-Avalos E, Hogan PG, Chang X, Rao A. Tet2 and Tet3 cooperate with B-lineage transcription factors to regulate DNA modification and chromatin accessibility. Elife. 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Sardina JL, Collombet S, Tian TV, Gomez A, Di Stefano B, Berenguer C, et al. Transcription Factors Drive Tet2-Mediated Enhancer Demethylation to Reprogram Cell Fate. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23(6):905–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rasmussen KD, Berest I, Kessler S, Nishimura K, Simon-Carrasco L, Vassiliou GS, et al. TET2 binding to enhancers facilitates transcription factor recruitment in hematopoietic cells. Genome Res. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang R, Qu C, Zhou Y, Konkel JE, Shi S, Liu Y, et al. Hydrogen Sulfide Promotes Tet1- and Tet2-Mediated Foxp3 Demethylation to Drive Regulatory T Cell Differentiation and Maintain Immune Homeostasis. Immunity. 2015;43(2):251–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lio CJ, Shukla V, Samaniego-Castruita D, Gonzalez-Avalos E, Chakraborty A, Yue X, et al. TET enzymes augment activation-induced deaminase (AID) expression via 5-hydroxymethylcytosine modifications at the Aicda superenhancer. Sci Immunol. 2019;4(34). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xiong J, Zhang Z, Chen J, Huang H, Xu Y, Ding X, et al. Cooperative Action between SALL4A and TET Proteins in Stepwise Oxidation of 5-Methylcytosine. Molecular cell. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang Q, Zhao K, Shen Q, Han Y, Gu Y, Li X, et al. Tet2 is required to resolve inflammation by recruiting Hdac2 to specifically repress IL-6. Nature. 2015;525(7569):389–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carty SA, Gohil M, Banks LB, Cotton RM, Johnson ME, Stelekati E, et al. The Loss of TET2 Promotes CD8(+) T Cell Memory Differentiation. J Immunol. 2018;200(1):82–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nair VS, Song MH, Ko M, Oh KI. DNA Demethylation of the Foxp3 Enhancer Is Maintained through Modulation of Ten-Eleven-Translocation and DNA Methyltransferases. Mol Cells. 2016;39(12):888–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yue X, Trifari S, Aijo T, Tsagaratou A, Pastor WA, Zepeda-Martinez JA, et al. Control of Foxp3 stability through modulation of TET activity. J Exp Med. 2016;213(3):377–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yue X, Lio CJ, Samaniego-Castruita D, Li X, Rao A. Loss of TET2 and TET3 in regulatory T cells unleashes effector function. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakatsukasa H, Oda M, Yin J, Chikuma S, Ito M, Koga-Iizuka M, et al. Loss of TET proteins in regulatory T cells promotes abnormal proliferation, Foxp3 destabilization and IL-17 expression. Int Immunol. 2019;31(5):335–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Issuree PD, Day K, Au C, Raviram R, Zappile P, Skok JA, et al. Stage-specific epigenetic regulation of CD4 expression by coordinated enhancer elements during T cell development. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang Y, Rao A. Connections between TET proteins and aberrant DNA modification in cancer. Trends in genetics : TIG. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Palomero T, Couronne L, Khiabanian H, Kim MY, Ambesi-Impiombato A, Perez-Garcia A, et al. Recurrent mutations in epigenetic regulators, RHOA and FYN kinase in peripheral T cell lymphomas. Nature genetics. 2014;46(2):166–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sakata-Yanagimoto M, Enami T, Yoshida K, Shiraishi Y, Ishii R, Miyake Y, et al. Somatic RHOA mutation in angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46(2):171–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rasmussen KD, Helin K. Role of TET enzymes in DNA methylation, development, and cancer. Genes Dev. 2016;30(7):733–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Orlanski S, Labi V, Reizel Y, Spiro A, Lichtenstein M, Levin-Klein R, et al. Tissue-specific DNA demethylation is required for proper B-cell differentiation and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(18):5018–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kafer GR, Li X, Horii T, Suetake I, Tajima S, Hatada I, et al. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine Marks Sites of DNA Damage and Promotes Genome Stability. Cell reports. 2016;14(6):1283–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yamaguchi S, Hong K, Liu R, Shen L, Inoue A, Diep D, et al. Tet1 controls meiosis by regulating meiotic gene expression. Nature. 2012;492(7429):443–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moran-Crusio K, Reavie L, Shih A, Abdel-Wahab O, Ndiaye-Lobry D, Lobry C, et al. Tet2 loss leads to increased hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and myeloid transformation. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(1):11–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mouly E, Ghamlouch H, Della-Valle V, Scourzic L, Quivoron C, Roos-Weil D, et al. B-cell tumor development in Tet2-deficient mice. Blood advances. 2018;2(6):703–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhao Z, Chen L, Dawlaty MM, Pan F, Weeks O, Zhou Y, et al. Combined Loss of Tet1 and Tet2 Promotes B Cell, but Not Myeloid Malignancies, in Mice. Cell Rep. 2015;13(8):1692–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lio CJ, Yuita H, Rao A. Dysregulation of the TET family of epigenetic regulators in lymphoid and myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2019;134(18):1487–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Blaschke K, Ebata KT, Karimi MM, Zepeda-Martinez JA, Goyal P, Mahapatra S, et al. Vitamin C induces Tet-dependent DNA demethylation and a blastocyst-like state in ES cells. Nature. 2013;500(7461):222–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yue X, Trifari S, Aijo T, Tsagaratou A, Pastor WA, Zepeda-Martinez JA, et al. Control of Foxp3 stability through modulation of TET activity. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sasidharan Nair V, Song MH, Oh KI. Vitamin C Facilitates Demethylation of the Foxp3 Enhancer in a Tet-Dependent Manner. Journal of immunology. 2016;196(5):2119–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yue X, Rao A. TET family dioxygenases and the TET activator vitamin C in immune responses and cancer. Blood. 2020;136(12):1394–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Agathocleous M, Meacham CE, Burgess RJ, Piskounova E, Zhao Z, Crane GM, et al. Ascorbate regulates haematopoietic stem cell function and leukaemogenesis. Nature. 2017;549(7673):476–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cimmino L, Dolgalev I, Wang Y, Yoshimi A, Martin GH, Wang J, et al. Restoration of TET2 Function Blocks Aberrant Self-Renewal and Leukemia Progression. Cell. 2017;170(6):1079–95 e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cimmino L, Neel BG, Aifantis I. Vitamin C in Stem Cell Reprogramming and Cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28(9):698–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vincenzetti L, Leoni C, Chirichella M, Kwee I, Monticelli S. The contribution of active and passive mechanisms of 5mC and 5hmC removal in human T lymphocytes is differentiation- and activation-dependent. Eur J Immunol. 2019;49(4):611–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ko M, An J, Pastor WA, Koralov SB, Rajewsky K, Rao A. TET proteins and 5-methylcytosine oxidation in hematological cancers. Immunol Rev. 2015;263(1):6–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lio CJ, Rao A. TET Enzymes and 5hmC in Adaptive and Innate Immune Systems. Front Immunol. 2019;10:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ito K, Lee J, Chrysanthou S, Zhao Y, Josephs K, Sato H, et al. Non-catalytic Roles of Tet2 Are Essential to Regulate Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell Homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2019;28(10):2480–90 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Figueroa ME, Abdel-Wahab O, Lu C, Ward PS, Patel J, Shih A, et al. Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(6):553–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Williams K, Christensen J, Pedersen MT, Johansen JV, Cloos PA, Rappsilber J, et al. TET1 and hydroxymethylcytosine in transcription and DNA methylation fidelity. Nature. 2011;473(7347):343–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Neri F, Incarnato D, Krepelova A, Rapelli S, Pagnani A, Zecchina R, et al. Genome-wide analysis identifies a functional association of Tet1 and Polycomb repressive complex 2 in mouse embryonic stem cells. Genome biology. 2013;14(8):R91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kieffer-Kwon KR, Tang Z, Mathe E, Qian J, Sung MH, Li G, et al. Interactome maps of mouse gene regulatory domains reveal basic principles of transcriptional regulation. Cell. 2013;155(7):1507–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lieberman-Aiden E, van Berkum NL, Williams L, Imakaev M, Ragoczy T, Telling A, et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science. 2009;326(5950):289–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rao SS, Huntley MH, Durand NC, Stamenova EK, Bochkov ID, Robinson JT, et al. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell. 2014;159(7):1665–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fullwood MJ, Liu MH, Pan YF, Liu J, Xu H, Mohamed YB, et al. An oestrogen-receptor-alpha-bound human chromatin interactome. Nature. 2009;462(7269):58–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mumbach MR, Rubin AJ, Flynn RA, Dai C, Khavari PA, Greenleaf WJ, et al. HiChIP: efficient and sensitive analysis of protein-directed genome architecture. Nat Methods. 2016;13(11):919–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hu G, Cui K, Fang D, Hirose S, Wang X, Wangsa D, et al. Transformation of Accessible Chromatin and 3D Nucleome Underlies Lineage Commitment of Early T Cells. Immunity. 2018;48(2):227–42 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kloetgen A, Thandapani P, Tsirigos A, Aifantis I. 3D Chromosomal Landscapes in Hematopoiesis and Immunity. Trends Immunol. 2019;40(9):809–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen C, Yu W, Tober J, Gao P, He B, Lee K, et al. Spatial Genome Re-organization between Fetal and Adult Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Cell Rep. 2019;29(12):4200–11 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Oudelaar AM, Beagrie RA, Gosden M, de Ornellas S, Georgiades E, Kerry J, et al. Dynamics of the 4D genome during in vivo lineage specification and differentiation. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang X, Jeong M, Huang X, Wang XQ, Wang X, Zhou W, et al. Large DNA Methylation Nadirs Anchor Chromatin Loops Maintaining Hematopoietic Stem Cell Identity. Mol Cell. 2020;78(3):506–21 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Catarino RR, Stark A. Assessing sufficiency and necessity of enhancer activities for gene expression and the mechanisms of transcription activation. Genes Dev. 2018;32(3–4):202–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]