Abstract

This study provides a quantitative synthesis of the prospective associations between personality traits (neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, conscientiousness) and the risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. We conducted five separate meta-analyses with 8–12 samples (N = 30,036 to 33,054) that were identified through a systematic literature search following the MOOSE guidelines. Higher neuroticism (HR = 1.24, 95% CI [1.17, 1.31]) and lower conscientiousness (HR = 0.77, 95% CI [0.73, 0.81]) were associated with increased dementia risk, even after accounting for covariates such as depressive symptoms. Lower extraversion (HR = 0.92, 95% CI [0.86, 0.97]), openness (HR = 0.91, 95% CI [0.86, 0.96]), and agreeableness (HR = 0.90, 95% CI [0.83, 0.98]) were also associated with increased risk, but these associations were less robust and not significant in fully adjusted models. No evidence of publication bias was found. The strength of associations was unrelated to publication year (i.e., no evidence of winner’s curse). Meta-regressions indicated consistent effects for neuroticism, openness, and conscientiousness across methods to assess dementia, dementia type, follow-up length, sample age, minority, country, and personality measures. The association of extraversion and agreeableness varied by country. Our findings indicate robust associations of neuroticism and conscientiousness with dementia risk.

Keywords: Personality traits, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, meta-analysis, neuroticism, conscientiousness

1. Introduction

Dementia is a leading cause of disability among older adults worldwide (Alzheimer’s Association, 20117; Baumgart et al., 2015; Livingston et al., 2017). The most common type of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, a progressive neurodegenerative disease that often begins with pathological changes in the brain and then progresses to mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Dementia is associated with considerable physical, psychological, social, and economic burden on the individual, their caregivers and families, and society at large (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017; World Health Organization, 2019). As such, the World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes dementia as a public health priority (World Health Organization, 2019). The etiology of dementia is complex and a broad range of risk factors across multiple domains contribute to risk of developing the disease. These factors range from genetic (e.g., ε4 variant of the apolipoprotein E; Deckers et al., 2015) and sociodemographic (e.g., education; Baumgart et al., 2015) to environmental (e.g., exposure to pollution; Peters et al., 2019) factors.

Within this continuum, a growing literature suggests that personality traits are risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (Chapman et al., 2019; Kaup et al., 2019; Terracciano et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2007). Personality refers to relatively enduring differences in behaviors, thoughts, and feelings (Allemand et al., 2008; Costa and McCrae, 1992; Löckenhoff et al., 2008). The Five-Factor Model (FFM) organizes personality into five basic traits (Costa and McCrae, 1992): neuroticism (the tendency to experience negative emotions and difficulties with impulse control), extraversion (the tendency to be sociable, energetic, and assertive), openness (the tendency to be creative and to prefer variety), agreeableness (the tendency to be trusting, cooperative, and altruistic), and conscientiousness (the tendency to be organized, responsible, and disciplined). These individual differences are relatively stable across most of the adult lifespan and predict important life outcomes such as health (Strickhouser et al., 2017). Of the FFM personality traits, neuroticism and conscientiousness emerge as the most important predictors for cognitive health. Specifically, higher neuroticism and lower conscientiousness have been associated with an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (Duchek et al., 2019; Terracciano et al., 2014) and dementia more generally (Kaup et al., 2019; Singh-Manoux et al., 2020). In a previous meta-analytic project, we found that not only higher neuroticism and lower conscientiousness, but also lower openness and agreeableness were associated with increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease (Terracciano et al., 2014). A few recent studies further suggest that lower extraversion, openness, and agreeableness are related to increased risk of incident dementia (Aschwanden et al., 2020; Chapman et al., 2019; Duberstein et al., 2011; Singh-Manoux et al., 2020; Terracciano et al., 2017b), but the findings for these traits are mixed. It is also unclear whether there are factors that moderate these associations.

Since our meta-analytic project in 2014 (Terracciano et al., 2014), the published findings on personality and dementia have expanded considerably. However, there has been no systematic attempt to assess publication bias or to examine potential moderators of the meta-analytic associations. The goal of this study is thus twofold: First, we aim to provide an up-to-date estimation of the association between the FFM personality traits and risk of incident all-cause dementia (hereafter, “dementia” is used when referring to our outcome variable). The present study of five meta-analyses with at least N = 33,036 individuals is six times larger than the total samples examined previously (N = 5,054; Terracciano et al., 2014), which should provide more robust estimates of effect sizes. Furthermore, our previous work focused on published studies using a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. We expand on this by including studies that (a) examined all causes of dementia (i.e., not just Alzheimer’s disease) and (b) applied cognitive cut-off scores to classify dementia. Second, we aim to fill a major gap in the literature by addressing potential publication bias and testing several potential moderators. It is crucial to assess publication bias because it can lead to overestimated effects and may suggest the existence of non-existing effects in meta-analysis (van Aert et al., 2019). It is also important to examine factors that potentially moderate the meta-analytic associations since this provides insights in the robustness and generalizability of the findings. Therefore, the current study tested whether the meta-analytic associations vary by classification of dementia (clinical diagnosis vs. cognitive cut-off score) and other important aspects, such as follow-up time, year of publication, dementia type, country, average age of the sample, proportion of minority, and personality measure.

Based on previous literature, we hypothesized that higher neuroticism and lower conscientiousness would be associated with an increased risk of incident dementia. We further expected lower openness and agreeableness to be associated with increased dementia risk because we found such associations when estimates were pooled across studies in the previous meta-analytic project (Terracciano et al., 2014). We expected, however, stronger associations for neuroticism and conscientiousness than for openness and agreeableness.

2. Methods

2.1. Meta-Analyses

The meta-analyses were prepared in accordance with the MOOSE recommendations for meta-analyses of observational studies (Stroup et al., 2000). The MOOSE checklist can be found in the supplemental material S2. The research question was formed using the PICO framework (Schardt et al., 2007) with P (participants) = cognitively unimpaired older adults at baseline; I (Intervention) = no intervention / exposure, observational (cohort study); C (Comparison) = level of personality traits (individual differences), and O (Outcome) = risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease and all-cause dementia.

2.1.1. Eligibility criteria.

Studies on the relation between personality and risk of dementia were included if the following criteria were met: (1) Study design: Studies were longitudinal. (2) Publication status: Studies were published in an English language, peer-reviewed journal. (3) Measure of dementia: Studies reported how dementia was assessed. Dementia classification was through (a) clinical diagnosis, (b) neuropathological evaluation, or (c) by a cut-off for cognitive performance. (4) Measure of personality: Studies reported how personality was measured and assessed at least one of the following traits: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and/or conscientiousness.

2.1.2. Search strategy.

A systematic literature search of five electronic databases covering all years up to June 2020 was conducted. The databases searched were MEDLINE provided by PubMed, Science Direct, Web of Science as well as psycINFO and psycARTICLES provided by APA PsycNet. The search terms used were personality OR personality traits OR neuroticism OR conscientiousness OR extraversion OR openness OR openness to experience OR agreeableness OR five factor OR big five AND dementia OR Alzheimer’s*. Further, the reference lists of previous work were screened for additional studies. A first researcher (DA) screened the titles and keywords of each article for eligibility. Those meeting initial screening criteria were then screened at the abstract level. If a study appeared to meet eligibility criteria, full-text articles were obtained. The full text-articles of the remaining studies were then independently assessed for inclusion by a second researcher (AT). Discrepancies were discussed and resolved.

2.1.3. Statistical analysis.

To reduce variability across studies, we generally chose the risk estimates from the main model, with age, gender, education, and race/ethnicity as covariates. In addition, we conducted supplementary analyses with studies that accounted for depressive symptoms. Effects reported as linear regression coefficients (Duchek et al., 2019) were exponentiated to get the odds ratio1. Effects reported as odds ratios (Wilson et al., 2005) and risk ratios (Wilson et al., 2006) were directly considered as hazard ratios (HRs). The HRs and confidence intervals were inverted in one study that presented one unit decrease (vs. increase) in personality traits in relation to dementia risk (Wang et al., 2009). The log-transformed HR and standard error were scaled in five studies (Johansson et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2009; Wilson et al., 2007, 2006, 2005) to correspond to the effect associated with a difference of one standard deviation (1 SD) on the trait. Calculation of the pooled mean effect size was conducted using random-effect model meta-analyses. Between-study heterogeneity was quantified using tau2, Hedges Q, and I2 statistics (Higgins et al., 2003). I2 ranges between 0% and 100%, whereof values exceeding 50% were considered to represent large heterogeneity (Bellou et al., 2017).

Given the lack of consensus around measures of publication bias, we incorporated three strategies for its assessment. First, the distribution of obtained effect sizes was examined in a funnel plot and the Egger’s test for funnel plot asymmetry (Egger et al., 1997) was used to evaluate whether the distribution was significantly asymmetrical. Second, we applied a trim and fill procedure to obtain a bias-corrected estimate of the overall effect (Duval and Tweedie, 2000). Third, the precision-effect test and precision-effect estimate with standard errors (PET-PEESE; Stanley and Doucouliagos, 2014) was used to estimate the effect size that would be expected in a hypothetical study with a standard error of zero. PET adjusts for small-study effects (i.e., the tendency of studies with smaller samples to produce larger effect sizes) and assesses if there is a true effect beyond publication bias. If PET is significant (i.e., indication of true effect), the additional PEESE provides a better estimate as it corrects for a non-linear association between the reported effect size and standard errors (Stanley and Doucouliagos, 2014). We also conducted p-curve analyses (Simonsohn et al., 2015, 2014) to explore the consistency and distribution of statistically significant results and to distinguish whether significant findings were likely or unlikely to be the result of selective reporting.

We followed up the meta-analyses with a series of meta-regressions to help identify potential sources of heterogeneity when estimating the pooled hazard ratios. First, we tested whether results differed between studies that used a clinical diagnosis to assess dementia compared to studies that relied on cognitive performance, as the latter may include more misdiagnosis. Second, we tested whether the associations were moderated by the length of follow-up since the time interval could be informative on the potential for reverse causation. Third, we tested whether year of publication moderated the strength of the associations because effect sizes tend to become smaller in later studies (Combs, 2010). Next, we tested whether the findings generalize to other dementia types (Alzheimer’s disease vs. all-cause dementia) and samples from other countries (USA vs. other) given our previous meta-analytic work focused on Alzheimer’s disease and consisted of US samples only (Terracciano et al., 2014). To further test the generalizability of our findings, the following moderators were examined: age of the sample, proportion of minority, and personality measure. The latter was grouped by the two most common measures across the samples (i.e., NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) vs. not NEO-FFI and Midlife Development Inventory (MIDI) Personality Scale vs. not MIDI). Except for year of publication, all moderators were dichotomized to facilitate meta-regressions.

The meta-analyses and meta-regressions were conducted using the “metafor” package (Viechtbauer, 2010) in R software. The HR were log-transformed, and their standard errors were computed from the reported confidence intervals to conduct the analyses using “metafor”. Z-scores were calculated by dividing the log-transformed HR by its standard error (Dear et al., 2019) to enable the p-curve analyses. P-curve analyses were conducted using the online app (version 4.06) provided at http://www.p-curve.com/app4/.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

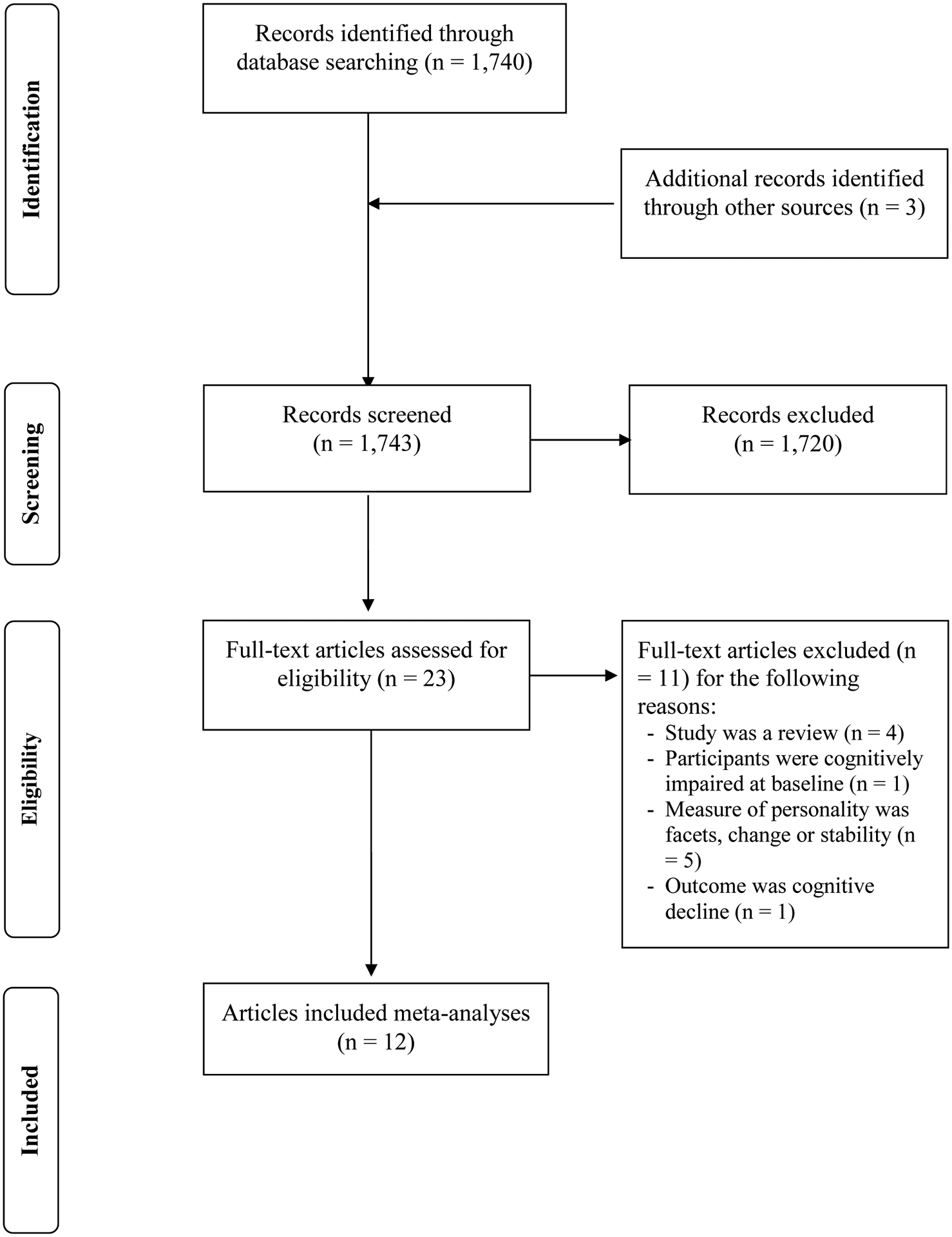

Figure 1 summarizes the screening procedure. A breakdown of the database searches is provided in the supplemental material S1. The literature search revealed 1,740 total hits (abstracts). Two articles (Wilson et al., 2006, 2005) were identified by screening the reference list of our previous meta-analytic work (Terracciano et al., 2014) and a recent article was identified as it comes from our research group (Aschwanden et al., 2020). After title, keyword, and abstract screening, the full texts of 23 articles were obtained. Thereof, the results from 13 cohorts were included in the present study and the number of included samples varied across traits: neuroticism k = 12; extraversion k = 10; openness k = 9; agreeableness k = 8; conscientiousness k = 9. Table 1 provides a summary of the characteristics of included samples.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for identifying eligible studies. In the present meta-analytic investigation, 12 articles (results from 13 samples) were included.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Studies Included in the Meta-Analyses

| Study (Authors & Year) | Country | N tot | N dem | Age M (SD) | Female% | Education M (SD) | Minority (%) | Follow-up (M years) | Personality traits | Personality measure | Type of dementia | Dementia classification | Covariates (main model) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rush Biracial (Wilson et al., 2005) | USA | 1,064 | 170 | 73.8 (9.6) | 61.9 | 12.9 (6.3) | 50.2 | NA (max = 6) | N | NEO FFIc | AD | clinical | age, sex, race, education, possession of an APOE-ε4 allele, follow-up time |

| Rush MAP (Wilson et al., 2006) | USA | 648 | 55 | 80.6 (6.9) | 73.5 | 14.6 (2.9) | 6.3 | 3 | N | NEO FFI | AD | clinical | age, sex, education |

| Rush ROS (Wilson et al., 2007) | USA | 904 | 176 | 73.5–80.0 (6.5)a | 68.0–71.0a | 17.8(3.4)–18.2(3.3)a | NA | NA (max =12) | N, E, O, A, C | NEO FFI | AD | neuropathologic | age, sex, education |

| KPS (Wang et al., 2009) | Sweden | 506 | 144 | 83.0(3.2)–83.9(3.7)a | 69.6–76.4a | categorical | NA | NA (max = 6) | N, E | Eysenck | dementia | clinical | age, sex, education, ApoE-ε4 status, cognitive functioning, vascular diseases, depressive symptoms |

| GEM (Duberstein et al., 2011) | USA | 767 | 116 | 78.6 (3.1) | 41.9 | categorical | 8.2 | 6 | N, E, O, A, C | NEO FFI | AD, vascular dementia | clinical | age, gender, education, race |

| BLSA (Terracciano et al., 2014) | USA | 1,671 | 90 | 56.5 (16.0) | 49.4 | 16.7 (2.5) | 29.3 | 12 | N, E, O, A, C | NEO PI-R | AD | clinical | age, sex, ethnicity, education |

| PPSW (Johansson et al., 2014) | Sweden | 800 | 153 | 38–54 | 100 | categorical | NA | NA (max = 38) | N, E | Eysenck | all-type dementia, AD, vascular dementia | clinical | age |

| HRS (Terracciano et al., 2017b) | USA | 10,457 | 433 | 67.17 (9.23) | 60 | 13.19 (2.66) | 17 | 6.29 | N, E, O, A, C | MIDIc | dementia | cognitive cutoff | age, sex, race, ethnicity, education |

| HABC (Kaup et al., 2019) | USA | 875 | 125 | 75.1–75.3 (2.8)a | 50 | ordinal | 47 | 6.9 | O, C | NEO FFI | dementia | clinical / cognitive cutoff | no covariates |

| WashU (Duchek et al., 2019) | USA | 436 | 47 | 65.9 (9.2) | 57 | 15.8 (2.6) | NA | 6.95 | N, C | NEO-FFI | AD | clinical | age |

| Whitehall II (Singh-Manoux et al., 2020) | United Kingdom | 6,136 | 118 | 69.59(5.78)–75.38(4.97) | 30 | ordinal | 10 | 4.37 | N, E, O, A, C | MIDIc | dementia | electronical health data | age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, education |

| ELSA (Aschwanden et al., 2020) | England | 6,887 | 252 | 65.65 (8.31) | 56.2 | 3.26 (2.21)b | 2.5 | 5.68 | N, E, O, A, C | MIDIc | dementia | cognitive cutoff / self-report | age, gender, ethnicity, education |

| HILDA (Aschwanden et al., 2020) | Australia | 2,778 | 52 | 60.90 (8.08) | 54.7 | 1.55 (1.79)b | 1 | 10.96 | N, E, O, A, C | Mini-Markers Saucier | dementia | cognitive cutoff / self-report | age, gender, ethnicity, education |

Note. Rush Biracial = Rush Memory and Aging Biracial (White, African-Americans); Rush MAP = Rush Memory and Aging Project; Rush ROS = Rush Religious Order Study; KPS = Kungsholmen Project Stockholm; GEM = Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study; BLSA = Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging; PPSW = Prospective Population Study of Women; HRS = Health Retirement Study; HABC = Health, Aging and Body Composition Study; WashU = Study conducted at Washington University in St. Louis; Whitehall II = Whitehall II Study; ELSA = English Longitudinal Study of Aging; HILDA = Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia; Ntot = total sample size; Ndem = number of incident dementia cases; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; NA = not applicable (information not found); N = neuroticism; E = extraversion; O = openness; A = agreeableness; C = conscientiousness; NEO FFI = NEO Five Factor Inventory; NEO PI-R = Revised NEO Personality Inventory; MIDI = Midlife Development Inventory; AD = Alzheimer’s disease. If type of dementia is not specified here, the original study used dementia more generally as outcome variable. Risk estimates from the main model were used (with age, gender, education, and race/ethnicity as covariates). In two studies, the main model also included APOE-ε4 allele status and follow-up time (Rush Biracial) or vascular diseases, depressive symptoms, and cognitive functioning (KPS). In two other studies, the main model consisted of age, gender, and education only (Rush MAP, ROS). In two further studies, we chose the model with age only (PPSW, WashU) and without covariates (HABC), respectively, because their further models were adjusted for various behavioral and health variables (e.g., smoking, hypertension).

is not provided for the total sample, participants were categorized into groups for use in descriptive statistics;

on a scale from 0–6;

only four items were used to assess neuroticism.

3.2. Personality and Dementia Risk

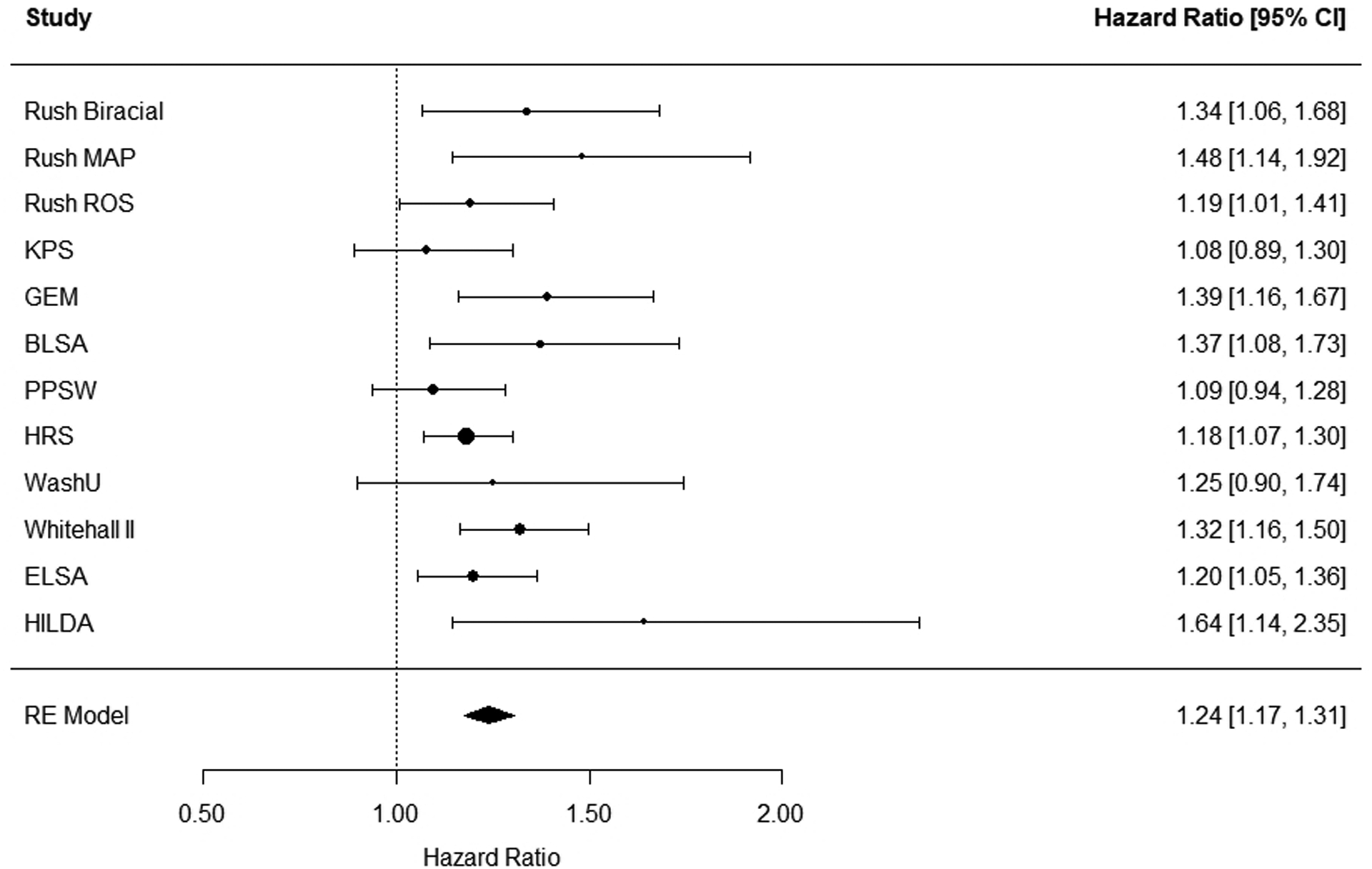

The HR from each study and the pooled association are presented in Table 2. By pooling the results from 12 studies, we found that for every SD increase in neuroticism, the risk of dementia increased by 24% (HR = 1.24, 95% CI [1.17, 1.31], p <.001). Figure 2 contains the forest plot summarizing the individual study estimates for neuroticism. Of the 12 studies, 9 studies reported a significant association. Heterogeneity was non-significant according to the Q-value and less than moderate referring to the I2-value (Q = 13.67, df = 11, p = .252; I2 = 13.29%).

Table 2.

Risk of Incident Dementia Associated with Personality Traits Reported in Each Study, Meta-Analytical Effect Sizes, and Heterogeneity

| Study | Sample size | HR 95% CI [LL, UL] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | E | O | A | C | ||

| Rush Biracial | 1,064 | 1.338 [1.065, 1.682]a | - | - | - | - |

| Rush MAP | 648 | 1.480 [1.143, 1.918] | - | - | - | - |

| Rush ROS | 904 | 1.192 [1.008, 1.409] | 1.093 [0.911, 1.312] | 0.905 [0.759, 1.081] | 0.899 [0.764, 1.059] | 0.812 [0.693, 0.951] |

| KPS | 506 | 1.078 [0.892, 1.303] | 0.834 [0.693, 1.003] | - | - | - |

| GEM | 767 | 1.390 [1.160, 1.670] | 0.900 [0.740, 1.080] | 0.780 [0.640, 0.950] | 0.860 [0.710, 1.040] | 0.760 [0.630, 0.930] |

| BLSA | 1,671 | 1.371 [1.085, 1.733] | 0.860 [0.687, 1.077] | 0.889 [0.708, 1.117] | 0.858 [0.680, 1.083] | 0.692 [0.549, 0.873] |

| PPSW | 800 | 1.095 [0.936, 1.282] | 0.936 [0.790, 1.107] | - | - | - |

| HRS | 10,457 | 1.180 [1.070, 1.300] | 0.980 [0.890, 1.090] | 0.940 [0.860, 1.040] | 0.830 [0.750, 0.910] | 0.800 [0.730, 0.880] |

| HABC | 875 | - | - | 0.890 [0.740, 1.060] | - | 0.750 [0.640, 0.890] |

| WashU | 436 | 1.250 [0.894, 1.740] | 1.112 [0.802, 1.542] | 0.995 [0.712, 1.388] | 0.918 [0.658, 1.278] | 0.634 [0.457, 0.881]b |

| Whitehall II | 6,136 | 1.320 [1.160, 1.490] | 0.850 [0.750, 0.970] | 0.940 [0.830, 1.070] | 1.080 [0.940, 1.250] | 0.720 [0.640, 0.810] |

| ELSA | 6,887 | 1.199 [1.054, 1.364] | 0.867 [0.770, 0.976] | 0.892 [0.787, 1.010] | 0.964 [0.852, 1.090] | 0.814 [0.723, 0.915] |

| HILDA | 2,778 | 1.641 [1.143, 2.355] | 0.758 [0.505, 1.137] | 0.895 [0.593, 1.351] | 0.685 [0.491, 0.956] | 0.788 [0.538, 1.155] |

| Meta-analytic results | ||||||

| k (Ntot / Ndem) | 12 (33,054 / 1,806) | 10 (31,342 / 1,581) | 9 (30,911 / 1,409) | 8 (30,036 / 2,528) | 9 (30,911 / 1,409) | |

| random model 95% CI [LL, UL] | 1.236 [1.151, 1.327] | 0.949 [0.879, 1.024] | 0.909 [0.863, 0.959] | 0.901 [0.829, 0.979] | 0.771 [0.734, 0.811] | |

| z (p-value) | 5.85 (<.001) | −1.35 (0.176) | −3.54 (<.001) | −2.45 (0.014) | −10.14 (<.001) | |

| tau2 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | |

| I2 (in %) | 46.59 | 48.30 | 0.00 | 46.16 | 0.00 | |

| Q (p-value); df | 20.24 (0.042); 11 | 17.05 (0.048); 9 | 3.53 (0.897); 8 | 13.14 (0.069); 7 | 5.46 (0.708); 8 | |

Note. Rush Biracial = Rush Memory and Aging Biracial (White, African-Americans); Rush MAP = Rush Memory and Aging Project; Rush ROS = Rush Religious Order Study; KPS = Kungsholmen Project Stockholm; GEM = Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study; BLSA = Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging; PPSW = Prospective Population Study of Women; HRS = Health Retirement Study; HABC = Health, Aging and Body Composition Study; WashU = Study conducted at Washington University in St. Louis; Whitehall II = Whitehall II Study; ELSA = English Longitudinal Study of Aging; HILDA = Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia; HR = hazard ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence intervals, LL and UL indicate the lower and upper limits of the confidence intervals; N = neuroticism; E = extraversion; O = openness; A = agreeableness; C = conscientiousness; k = number of studies; Ntot = total sample size; Ndem = number of total incident dementia. Between-study heterogeneity was quantified using tau2, Q and I2 values (Higgins et al., 2003). However, these statistics tend to be underpowered in view of the small numbers of studies and inference about heterogeneity should be made with caution.

To scale the log-transformed HR and standard error in Rush Biracial (Wilson et al., 2005), we assumed that their reported SD = 11.3 resulted from an outlier or data entry error and used SD = 5 as done by Terracciano et al. (2014). The gist of results did not change when using the adapted versus the originally reported SD.

The OR provided for conscientiousness in WashU (Table 4 in Duchek et al., 2019) is in the wrong direction; the absolute value was taken before exponentiating (J. M. Duchek, personal communication, June 30, 2020). We included the corrected OR for conscientiousness, that is, OR = .634, 95% CI [.457, .881].

Figure 2.

Forest plot for neuroticism. The plot summarizes the individual study estimates and the average effect of the random-effects (RE) model. Effect sizes are displayed in hazard ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Rush Biracial = Rush Memory and Aging Biracial (White, African-Americans); Rush MAP = Rush Memory and Aging Project; Rush ROS = Rush Religious Order Study; KPS = Kungsholmen Project Stockholm; GEM = Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory study; BLSA = Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging; PPSW = Prospective Population Study of Women; HRS = Health Retirement Study; WashU = Study conducted at Washington University in St. Louis; Whitehall II = Whitehall II Study; ELSA = English Longitudinal Study of Aging; HILDA = Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia.

For extraversion, the meta-analysis of 10 studies showed that lower extraversion was associated with increased dementia risk (HR = 0.92, 95% CI [0.86, 0.97], p = .004). Of these 10 studies, 2 studies reported a significant effect (Figure S1). Heterogeneity was non-significant according to the Q-value and less than moderate referring to the I2-value (Q = 11.05, df = 9, p = .272; I2 = 19.64%).

We found a significant association for openness, such that open people were at lower risk of dementia (HR = 0.91, 95% CI [0.86, 0.96], p <.001). Of note, the association was significant in only 1 of the 9 studies included in the meta-analysis (GEM study, Duberstein et al., 2011; Figure S2). The Q and I2 values suggested homogeneity across studies (Q = 3.53, df = 8, p = .897; I2 = 0%).

For agreeableness, the meta-analysis of 8 studies showed that agreeable individuals were at lower risk of dementia (HR = 0.90, 95% CI [0.83, 0.98], p = .014). Two of the 8 included studies reported significant results (Figure S3). Heterogeneity was non-significant referring to the Q-value and less than moderate according to the I2-value (Q = 5.82, df = 6, p = .444; I2 = 46.16%).

Higher scores on conscientiousness were associated with reduced risk of incident dementia (HR = 0.77, 95% CI [0.73, 0.81], p <.001). Of the 9 included studies, 8 studies found a significant association (Figure S4), and there was no evidence of heterogeneity (Q = 5.46, df = 8, p = .708; I2 = 0%).

3.2.1. Supplementary Analyses

We conducted supplementary analyses with those studies that accounted for depressive symptoms in addition to demographic factors, and some of these studies also controlled for vascular and genetic risk factors. Table S1 lists the covariates that were included in each study. The number of included studies varied between traits: k = 6 for neuroticism; k = 4 for extraversion; k = 3 for openness; k = 2 for agreeableness; and k = 4 for conscientiousness. In all studies, depressive symptoms were measured using a version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale, except in KPS and PPSW. In KPS, depressive symptoms were assessed by self-reported problems such as persistently feeling lonely or in a low mood. In PPSW, depression was assessed using DSM-III criteria for major depressive disorders. The supplementary analyses showed that higher neuroticism (HR = 1.13, 95% CI [1.04, 1.22]) and lower conscientiousness (HR = 0.80, 95% CI [0.74, 0.86]) were still associated with increased dementia risk, but the effects of the remaining traits were non-significant (see Table S1).

3.3. Publication Bias

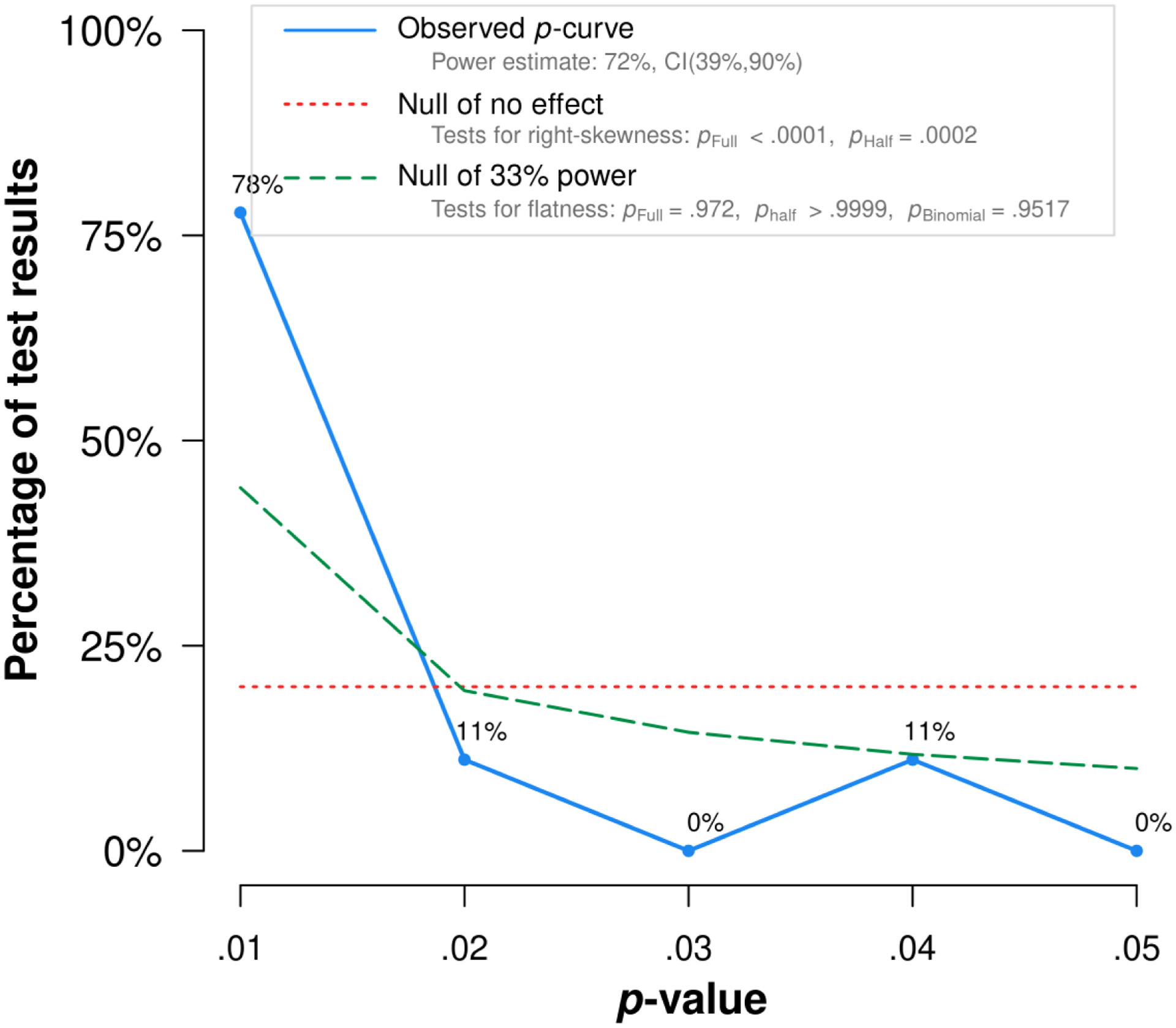

The Egger’s test, the trim and fill method, and the PET-PEESE found no evidence of publication bias for all personality traits (Table 3). Figure 3 shows the p-curve for neuroticism by displaying the 9 studies (out of 12) that were statistically significant. The application excludes non-significant results. The p-curve analysis provides information about the evidential value: If the half p-curve test is right-skewed with p < .05, or both the half and full test are right-skewed with p < .1, then p-curve analysis indicates the presence of evidential value (Simonsohn et al., 2015). For neuroticism, both conditions were met (p < .0001 and p =.0002, respectively; see supplemental material S3), suggesting evidential value and providing reassurance that the significant findings were unlikely to be the result of selective reporting. This was also the case for conscientiousness (supplemental material S3). For the remaining traits, no p-curve was calculated since there were only few significant individual study results (Carter et al., 2019).

Table 3.

Publication Bias

| Test | Estimate (p-value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | E | O | A | C | |

| Trim and Fill / Egger’s | 1.209 (0.099) | 0.919 (0.890) | 0.909 (0.427) | 0.954 (0.749) | 0.779 (0.179) |

| PET-PEESE | 1.095 (0.099) | 0.927 (0.890) | 0.943 (0.427) | 0.933 (0.749) | 0.791 (0.231) |

Note. N = neuroticism; E = extraversion; O = openness; A = agreeableness; C = conscientiousness. Publication bias was examined via Egger’s regression test for funnel plot asymmetry (Egger et al., 1997), the trim and fill method of adjusting for publication bias (Duval & Tweedie, 2000), and the precision-effect test and precision-effect estimate with standard errors (PET-PEESE; Stanley & Doucouliagos, 2014).

Figure 3.

P-curve for neuroticism. The observed p-curve includes 9 statistically significant (p < .05) results, of which 8 are p < .025. There were 3 additional results entered but excluded from p-curve because they were p > .05. The p-curve analysis provides information about the evidential value: If the half p-curve test is right-skewed with p < .05, or both the half and full test are right-skewed with p < .1, then p-curve analysis indicates the presence of evidential value (Simonsohn et al., 2015). Here, both conditions were met (p < .0001 and p =.0002, respectively; see supplemental material S3), suggesting evidential value and providing some reassurance that the significant findings were unlikely to be the result of selective reporting.

3.4. Meta-Regressions

Across the 8 moderators tested, two statistically significant effects were found (Table 4). Country moderated the association of dementia risk with extraversion (HR = 0.88, 95% CI [0.90, 0.98], p = .019) and agreeableness (HR = 1.15, 95% CI [1.03, 1.29], p = .015). The association between higher extraversion and lower dementia risk was statistically non-significant in American samples (HR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.91, 1.05], p = .542), while it was significant in studies from other countries (HR = 0.87, 95% CI [0.81, 0.93], p <.001). The opposite pattern was found for agreeableness: Higher scores on this trait were protective against dementia in US studies (HR = 0.85, 95% CI [0.80, 0.92], p <.001), but not in samples from other countries (HR = 0.93, 95% CI [0.75, 1.16], p = .535).

Table 4.

Findings from Meta-Regressions

| Moderators | HR 95% CI [LL, UL] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | E | O | A | C | |

| Dementia classification | 0.967 [0.864, 1.083] | 1.028 [0.905, 1.167] | 1.035 [0.932, 1.151] | 0.928 [0.784, 1.099] | 1.066 [0.964, 1.179] |

| Follow-up length | 0.977 [0.859, 1.110] | 1.052 [0.919, 1.204] | 0.986 [0.854, 1.139] | 0.909 [0.750, 1.101] | 1.003 [0.876, 1.149] |

| Year of publication | 1.000 [0.989, 1.011] | 0.993 [0.980, 1.006] | 1.005 [0.992, 1.019] | 1.006 [0.988, 1.025 | 0.997 [0.985, 1.009] |

| Dementia type | 1.070 [0.946, 1.210] | 1.127 [0.969, 1.311] | 1.005 [0.873, 1.157] | 0.983 [0.809, 1.195] | 0.969 [0.848, 1.107] |

| Country | 0.948 [0.842, 1.067] | 0.885* [0.799, 0.980] | 1.008 [0.904, 1.125] | 1.153* [1.028, 1.292] | 0.990 [0.892, 1.097] |

| Age | 1.006 [0.866, 1.169] | 1.041 [0.887, 1.221] | 1.023 [0.832, 1.258] | 1.166 [0.918, 1.481] | 1.082 [0.881, 1.328] |

| Minority | 1.105 [0.927, 1.317] | 0.935 [0.728, 1.201] | 0.975 [0.837, 1.135] | 0.948 [0.702, 1.280] | 0.938 [0.812, 1.084] |

| NEO-FFI | 0.918 [0.816, 1.032] | 0.905 [0.774, 1.058] | 1.074 [0.950, 1.213] | 1.029 [0.840, 1.261] | 0.992 [0.885, 1.112] |

| MIDI | 1.023 [0.910, 1.151] | 1.000 [0.880, 1.137] | 0.935 [0.834, 1.047] | 0.902 [0.757, 1.074] | 0.986 [0.886, 1.097] |

Note. HR = hazard ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence intervals, LL and UL indicate the lower and upper limits of the confidence intervals; N = neuroticism; E = extraversion; O = openness; A = agreeableness; C = conscientiousness. Moderator effects were explored for dementia classification (dementia based on clinical diagnosis vs. cognitive performance), follow-up length (mean above or below 10 years), year of publication (continuous variable), dementia type (dementia vs. Alzheimer’s disease), country (USA vs. other), age of sample (mean age above or below 65), minority (mean percentage above or below 20%), and personality measure grouped by the two most common measures across the samples (i.e., NEO-FFI vs. not NEO-FFI and MIDI vs. not MIDI).

p < 0.05.

For all personality traits, the results were similar across dementia classification, follow-up length, dementia type, age of sample, minority, and personality measure. It is particularly worth noting that the associations did not vary by classification of dementia. Follow-up analyses showed that the effect sizes were comparable, although slightly stronger for studies that relied on a clinical diagnosis. For example, for neuroticism, the effects were HR = 1.26 (95% CI [1.16, 1.36], p <.001) in studies using a clinical diagnosis and HR = 1.21 (95% CI [1.12, 1.30], p <.001) in those using a cognitive cut-off to classify dementia. For conscientiousness, the hazard ratios were HR = 0.75 (95% CI [0.69, 0.80], p <.001) in studies using a clinical diagnosis and HR = 0.80 (95% CI [0.74, 0.85], p <.001) in those applying a cognitive cut-off.

4. Discussion

The meta-analytic results showed that higher neuroticism and lower conscientiousness were associated with increased dementia risk. Lower levels of extraversion, openness, and agreeableness were also related to increased dementia risk, although to a weaker extent. The effects of neuroticism and conscientiousness, but not for the other traits, remained significant in models that further accounted for depressive symptoms. There was no evidence for publication bias. The association of neuroticism, openness, and conscientiousness did not vary by the tested moderators. Of note, the results were similar in studies that examined Alzheimer’s disease compared to all-type dementia, and the results were only slightly stronger in studies that used the gold-standard clinical diagnosis compared to ascertainment based on cognitive cut-off scores and medical records. The findings for publication bias and meta-regressions will be discussed in more detail below, followed by a discussion of possible explanations for the personality-dementia associations and potential implications for future research.

4.1. Publication Bias

Publication bias is a major threat to the validity of every meta-analysis as it can lead to overestimated effect sizes and the dissemination of false-positive results (Nuijten et al., 2015). Based on the tests used in the present meta-analyses, we found no evidence for biases in the personality-dementia literature and the significant results were unlikely to be due to selective reporting for neuroticism and conscientiousness. These findings, however, should be interpreted with caution because these methods have reduced statistical power when <10 effect sizes are examined (Sterne et al., 2011; van Aert et al., 2019). Nevertheless, it could be that the personality-dementia literature is less affected by publication bias because many studies examined more than one personality trait and therefore non-significant effects may be more likely to be published. In the present meta-analytic investigation, for example, 10 studies investigated both neuroticism and extraversion and consequently reported not only the significant effects for neuroticism but also the non-significant results for extraversion.

4.2. Moderators

The meta-analyses indicated a high degree of consistency across studies for all personality traits. In view of the small numbers of studies, however, heterogeneity should be interpreted with caution. Given the limited heterogeneity across studies, it was not surprising that the meta-regressions only identified one factor (country) that significantly moderated the meta-analytic results. While there was no statistically significant association between higher extraversion and lower dementia risk in American samples, a significant association was found in samples from other countries. Specifically, the two studies that reported a significant result came from the United Kingdom (Whitehall II) and England (ELSA). The association of agreeableness with dementia risk was statistically significant in some US studies (i.e., HRS) but not in samples from other countries (except Australia; HILDA). More research is needed to clarify whether the association of extraversion and agreeableness varies across different countries.

No further significant meta-regressions were found. These null findings address substantive questions on the robustness of the associations. First, we found no significant differences between studies that used a clinical diagnosis versus a cognitive cut-off to classify dementia, although the effect sizes were slightly smaller for the population-based panel studies that relied on cognitive performance. A clinical dementia diagnosis is the gold standard that is normally done by health professionals after an in-depth neuropsychological examination that includes a structured medical history, neurological examination, informant reporting, and cognitive testing. This level of detail is often beyond the capability of large population-based panel studies. In such studies, it is more likely that dementia is classified based on cognitive performance only. Although the applied cognitive cut-offs are often validated against a diagnosis based on DSM-III-R criteria, as in the Health and Retirement Study (Crimmins et al., 2011), they might be more prone to misdiagnosis or be less reliable considering that variability in cognitive performance increases with cognitive decline (Weir et al., 2011). In light of the aging population, however, it is important to have ways to ascertain cognitive impairment and dementia that are less costly than neuropsychological examinations and more precise than population surveys (Crimmins et al., 2011; Weir et al., 2011). The potential loss of power due to misclassification seems to be compensated by the large and more diverse samples recruited by population-based panel studies.

The length of follow-up did not affect the meta-analytic associations (see also Terracciano et al., 2017). This finding is contrary to expectations from the reverse causality hypothesis that assumes personality is changed by the underlying neuropathology in the prodromal phase of the disease. If that were the case, the association between personality and risk of dementia would be stronger among studies with a shorter follow-up (with a shorter follow-up, the assessment of personality is closer to the onset of dementia).

Year of publication did not moderate the meta-analytic findings. This is particularly reassuring and contrary to the winner’s curse pattern of later published studies tending to find increasingly smaller effects (Combs, 2010).

We found no differences between studies that focused on Alzheimer’s disease and those that used dementia more generally as an outcome. Future studies, however, are still needed to investigate whether personality traits can help in differential diagnosis, especially for frontotemporal dementia or Lewy body dementia.

Finally, neither the average age nor the proportion of minority of the samples influenced the results. Thus, across the adult life span and across races/ethnicities, personality shared the same relations with dementia risk. Likewise, personality-dementia associations were not moderated by the personality measure used, which indicates that the same pattern of associations holds across the two most common FFM questionnaires, again supporting the robustness of the findings.

4.3. Potential Mechanisms between Personality Traits and Dementia Risk

A recent review (Segerstrom, 2018) discussed four models that could explain the observed associations between personality and risk of dementia: common cause (e.g., through a common gene), spectrum (e.g., reflecting an early symptom), pathoplastic (e.g., conferring resilience to neuropathology), and predisposition (e.g., through health behaviors).

The common cause model proposes that genes that affect personality phenotype also affect dementia risk. Current evidence, however, suggests that the relatively small genetic effects are unlikely to play a major role in the association between personality and dementia (Luciano et al., 2018; Stephan et al., 2018), thereby weakening evidence for this model.

The spectrum model suggests that personality is a prodrome or other subclinical symptom of dementia. After the onset of dementia, it is common to observe personality change (Siegler et al., 1994). For example, a meta-analysis found large (>1 SD) declines in conscientiousness and extraversion as well as increases in neuroticism from the premorbid to current state in patients with cognitive impairment (Islam et al., 2019). Whilst these findings support personality change during the disease, personality does not appear to reflect a symptom before the onset of cognitive impairment: Changes in personality were not significantly different between individuals who later did or did not develop dementia in a longitudinal study that focused on the preclinical phase (Terracciano et al., 2017a). Moreover, personality in adolescence, a life stage presumably free from dementia related neuropathology, predicted dementia risk almost five decades later (Chapman et al., 2019). Although these findings indicate that the spectrum model is less likely, the temporal evolution of personality change across the different phases of dementia needs to be further clarified.

It seems more likely that personality has a predisposing or pathoplastic relationship to dementia risk. The pathoplastic model suggests that personality influences the presentation or course of dementia, such that personality may contribute to resilience against neuropathology and allows one to bear more neuropathology before experiencing symptoms (Graham et al., 2019; Terracciano et al., 2013).

The predisposition model proposes that personality shapes dementia risk through a cascade of effects on proximal behaviors and health conditions. For instance, higher neuroticism and lower conscientiousness are associated with a worse health profile, physical inactivity, obesity, smoking, depression, and lower education, which are risk factors for incident dementia (Bogg and Roberts, 2004; Chapman et al., 2011; Hampson et al., 2007; Sutin et al., 2018, 2011, 2010; Terracciano et al., 2008). Moreover, cognitive engagement could be an underlying mechanism between openness and dementia risk. Open individuals can be described as intellectually engaged, curious, and imaginative, and they tend to perform well on cognitive tasks (Curtis et al., 2015; Luchetti et al., 2016). They also tend to engage in a variety of activity types such as cognitive, social and physical activities (Stephan et al., 2014). The engagement in cognitive and other activities may positively contribute to cognitive reserve and protect against dementia (Chapman et al., 2012; Gow et al., 2005; Sharp et al., 2010). Likewise, being agreeable and extraverted could ease the formation and stability of social networks that in turn might reduce risk of dementia (Bennett et al., 2006; Crooks et al., 2008).

Finally, personality has not only been linked to behaviors and health conditions, but also to dementia-related biomarkers. Although the literature on personality and biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias is limited, recent studies have found some converging evidence that neuroticism is associated with measures of tau neurofibrillary tangles: A neuropathology study reported that individuals with higher neuroticism were more likely to have advanced stages of tau neurofibrillary tangles at autopsy (Terracciano et al., 2013). Similarly, in samples of cognitively healthy older adults or adults in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, higher neuroticism was associated with higher tau measured using in vivo positron emission tomography or cerebral spinal fluid (Duchek et al., 2019; Schultz et al., 2019). There is also evidence that higher neuroticism and lower conscientiousness are associated with reduction in regional brain volumes (Bjørnebekk et al., 2013; Jackson et al., 2011). Furthermore, lower conscientiousness has been linked to brain-tissue loss and other measures of brain integrity (Booth et al., 2014).

More knowledge about the amount of neuropathological burden is needed to differentiate between the pathoplastic and the predisposition model. If personality is linked to better cognitive function despite burden, the pathoplastic model would be favored (because personality affects the appearance or severity of dementia). If personality is related to reduced burden, the predisposition model would be favored (because personality reduces dementia risk directly or through other variables). Some evidence suggests a pathoplastic effect of neuroticism and a predisposing effect of conscientiousness (Segerstrom, 2018), but further research is needed to explain the personality-dementia associations.

4.4. Potential Implications, Strengths, and Limitations

Based on the present findings, two main implications for future research arise. First, the meta-analytic effect sizes for personality traits were comparable with those of other health and behavioral factors related to cognitive impairment and dementia, such as diabetes (RR = 1.18, 95% CI [1.02, 1.36]; Xue et al., 2019), hypertension (HR = 1.59, 95% CI [1.20, 2.11]; Sharp et al., 2011), physical activity (RR = 0.76, 95% CI [0.66, 0.86]; Blondell et al., 2014), cigarette smoking (RR = 1.30, 95% CI [1.18,1.45]; Zhong et al., 2015), low-to-moderate alcohol drinking (RR = 0.74, 95% CI [0.61, 0.91]; Anstey et al., 2009), or late-life BMI (RR = 0.83, 95% CI [0.74, 0.94]; Pedditizi et al., 2016). Of note, the HABC study (Kaup et al., 2019) accounted for many of these factors (i.e., depressive symptoms, hypertension, myocardial infarction, diabetes, stroke; see Table S1) and still found a significant effect of conscientiousness. In another study (Johansson et al., 2014), the hazard ratio of neuroticism did not change in the fully adjusted model that included hypertension, coronary heart disease, smoking, BMI, depression, age, and education (HR = 1.10, 95% CI [0.94, 1.28]) compared to the main model that controlled for age only (HR = 1.10, 95% CI [0.91, 1.31]). Although the hazard ratio was non-significant in both models, it went in the expected direction and the strength of association did not change when accounting for clinical factors. This underlines the importance of personality and indicates that personality should be considered when identifying at-risk individuals. Using web-based questionnaires, it is possible to inexpensively screen people in the community and identify those with scores high on neuroticism and low on conscientiousness (Chapman et al., 2014; Lahey, 2009). These individuals might benefit most from inclusion in preventive interventions. The development of innovative personality-tailored interventions is now necessary to move the field forward and test whether individuals high on neuroticism and low on conscientiousness respond well to such interventions. Likewise, recent research indicates that it might be possible to change personality traits, such as reducing maladaptive aspects of neuroticism through interventions (Chapman et al., 2014; Roberts et al., 2017; Rüegger et al., 2017; Stieger et al., 2020). If such changes are enduring, interventions that target personality could be incorporated into dementia prevention and eventually into the clinical context.

Second, we identified country as moderator for the associations of extraversion and agreeableness with dementia risk. These results may inspire future studies to conduct preregistered replication efforts to establish these associations and further investigate potential cross-cultural differences. Related to this issue, there is a great need for more studies, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries where approximately two thirds of people with dementia worldwide live in and the potential of dementia prevention is large (Anstey et al., 2019; Mukadam et al., 2019).

Strengths of this work include the systematic approach to study identification, the consideration of publication bias, and the exploration of potential moderator variables. Nevertheless, all meta-analytic techniques have limitations and should be used only to understand broad trends in a particular field (Carter et al., 2019). Specifically, the following issues should be considered when interpreting the present findings. First, we did not attempt to identify unpublished studies and we only included studies that were published in English. We were further unable to include relevant studies that used other research designs, but evidence from these studies tends to show similar conclusions (Crowe et al., 2006). Most of the included studies did not specify the type of dementia beyond Alzheimer’s disease and we thus could only test whether findings differ between Alzheimer’s disease and all-cause dementia. It would be interesting to validate our findings regarding different etiologies of dementia (e.g., vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia). Although the number of included individuals was relatively high for all five traits (ranging from N = 30,036 for agreeableness to N = 33,054 for neuroticism), the number of studies was relatively small (ranging from k = 8 for agreeableness to k = 12 for neuroticism), which reduced statistical power to examine publication bias and sources of heterogeneity.

4.5. Conclusion

Overall, the present work confirms consistent associations of neuroticism and conscientiousness with risk of dementia. The associations of the remaining traits were also significant but less robust. We found no evidence of publication bias, suggesting no systematic over- or under-estimation of the estimated effects. Moreover, there was limited evidence of heterogeneity and the associations were consistent across studies that used different methods to assess dementia, follow-up length, publication year, dementia type, age of the sample, proportion of minority, and personality measure. Studies are now needed to determine whether and how neuroticism and conscientiousness could be incorporated into interventions for dementia prevention.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (Grant Numbers R21AG057917 and R01AG053297).

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, the authorship, and publication of this article.

Note that, for neuroticism and conscientiousness, Duckek and colleagues (2019) report both regression coefficients and odds ratios in their article, but for the remaining traits, only regression coefficients are provided (in supplemental material). To be consistent in the calculation across all traits, we exponentiated the regression coefficients for all of them rather than taking the odds ratios for neuroticism and conscientiousness and exponentiating the coefficients for the remaining traits.

References

- Allemand M, Zimprich D, Martin M, 2008. Long-term correlated change in personality traits in old age. Psychol. Aging 23, 545–557. 10.1037/a0013239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association, 2017. 2017. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 13, 325–373. 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anstey KJ, Mack HA, Cherbuin N, 2009. Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for dementia and cognitive decline: meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 17, 542–555. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181a2fd07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschwanden D, Sutin AR, Luchetti M, Stephan Y, Terracciano A, 2020. Personality and dementia risk in England and Australia. GeroPsych 1–12. 10.1024/1662-9647/a000241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgart M, Snyder HM, Carrillo MC, Fazio S, Kim H, Johns H, 2015. Summary of the evidence on modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia: a population-based perspective. Alzheimers Dement. 11, 718–726. 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellou V, Belbasis L, Tzoulaki I, Middleton LT, Ioannidis JPA, Evangelou E, 2017. Systematic evaluation of the associations between environmental risk factors and dementia: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Alzheimers Dement. 13, 406–418. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.07.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Tang Y, Arnold SE, Wilson RS, 2006. The effect of social networks on the relation between Alzheimer’s disease pathology and level of cognitive function in old people: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 5, 406–412. 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70417-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørnebekk A, Fjell AM, Walhovd KB, Grydeland H, Torgersen S, Westlye LT, 2013. Neuronal correlates of the five factor model (FFM) of human personality: Multimodal imaging in a large healthy sample. NeuroImage 65, 194–208. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondell SJ, Hammersley-Mather R, Veerman JL, 2014. Does physical activity prevent cognitive decline and dementia?: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health 14. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogg T, Roberts BW, 2004. Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychol. Bull 130, 887–919. 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth T, Mõttus R, Corley J, Gow AJ, Henderson RD, Maniega SM, Murray C, Royle NA, Sprooten E, Hernández MCV, Bastin ME, Penke L, Starr JM, Wardlaw JM, Deary IJ, 2014. Personality, health, and brain integrity: The Lothian Birth Cohort Study 1936. Health Psychol. 33, 1477–1486. 10.1037/hea0000012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter EC, Schönbrodt FD, Gervais WM, Hilgard J, 2019. Correcting for bias in psychology: A comparison of meta-analytic methods. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci 2, 115–144. 10.1177/2515245919847196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman B, Duberstein P, Tindle HA, Sink KM, Robbins J, Tancredi DJ, Franks P, 2012. Personality predicts cognitive function over 7 years in older persons. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 20, 612–621. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31822cc9cb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman BP, Hampson S, Clarkin J, 2014. Personality-informed interventions for healthy aging: Conclusions from a National Institute on Aging work group. Dev. Psychol 50, 1426–1441. 10.1037/a0034135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman BP, Huang A, Peters K, Horner E, Manly J, Bennett DA, Lapham S, 2019. Association between high school personality phenotype and dementia 54 years later in results from a national us sample. JAMA Psychiatry 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman BP, Roberts B, Duberstein P, 2011. Personality and Longevity: Knowns, Unknowns, and Implications for Public Health and Personalized Medicine. J. Aging Res 2011, 1–24. 10.4061/2011/759170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs JG, 2010. Big samples and small effects: Let’s not trade relevance and rigor for power. Acad. Manage. J 53, 9–13. 10.5465/amj.2010.48036305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR, 1992. Four ways five factors are basic. Personal. Individ. Differ 13, 653–665. 10.1016/0191-8869(92)90236-I [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Langa KM, Weir DR, 2011. Assessment of cognition using surveys and neuropsychological assessment: the Health and Retirement Study and the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci 66B, i162–i171. 10.1093/geronb/gbr048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks VC, Lubben J, Petitti DB, Little D, Chiu V, 2008. Social network, cognitive function, and dementia incidence among elderly women. Am. J. Public Health 98, 1221–1227. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe M, Andel R, Pedersen NL, Fratiglioni L, Gatz M, 2006. Personality and risk of cognitive impairment 25 years later. Psychol. Aging 21, 573–580. 10.1037/0882-7974.21.3.573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis RG, Windsor TD, Soubelet A, 2015. The relationship between Big-5 personality traits and cognitive ability in older adults - a review. Neuropsychol. Dev. Cogn. B Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn 22, 42–71. 10.1080/13825585.2014.888392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dear K, Dutton K, Fox E, 2019. Do ‘watching eyes’ influence antisocial behavior? A systematic review & meta-analysis. Evol. Hum. Behav 40, 269–280. 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2019.01.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deckers K, van Boxtel MPJ, Schiepers OJG, de Vugt M, Muñoz Sánchez JL, Anstey KJ, Brayne C, Dartigues J-F, Engedal K, Kivipelto M, Ritchie K, Starr JM, Yaffe K, Irving K, Verhey FRJ, Köhler S, 2015. Target risk factors for dementia prevention: a systematic review and Delphi consensus study on the evidence from observational studies. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 30, 234–246. 10.1002/gps.4245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duberstein PR, Chapman BP, Tindle HA, Sink KM, Bamonti P, Robbins J, Jerant AF, Franks P, 2011. Personality and risk for Alzheimer’s disease in adults 72 years of age and older: A 6-year follow-up. Psychol. Aging 26, 351–362. 10.1037/a0021377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchek JM, Aschenbrenner AJ, Fagan AM, Benzinger TLS, Morris JC, Balota DA, 2019. The relation between personality and biomarkers in sensitivity and conversion to alzheimer-type dementia. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc 1–11. 10.1017/S1355617719001358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval S, Tweedie R, 2000. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56, 455–463. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C, 1997. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow AJ, Whiteman MC, Pattie A, Deary IJ, 2005. The personality–intelligence interface: insights from an ageing cohort. Personal. Individ. Differ 39, 751–761. 10.1016/j.paid.2005.01.028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE, Goldberg LR, Vogt TM, Dubanoski JP, 2007. Mechanisms by which childhood personality traits influence adult health status: Educational attainment and healthy behaviors. Health Psychol. 26, 121–125. 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG, 2003. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327, 557–560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M, Mazumder M, Schwabe-Warf D, Stephan Y, Sutin AR, Terracciano A, 2019. Personality changes with dementia from the informant perspective: New data and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc 20, 131–137. 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J, Balota DA, Head D, 2011. Exploring the relationship between personality and regional brain volume in healthy aging. Neurobiol. Aging 32, 2162–2171. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson L, Guo X, Duberstein PR, Hallstrom T, Waern M, Ostling S, Skoog I, 2014. Midlife personality and risk of Alzheimer disease and distress: A 38-year follow-up. Neurology 83, 1538–1544. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaup AR, Harmell AL, Yaffe K, 2019. Conscientiousness is associated with lower risk of dementia among black and white older adults. Neuroepidemiology 52, 86–92. 10.1159/000492821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, 2009. Public health significance of neuroticism. Am. Psychol 64, 241–256. 10.1037/a0015309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cooper C, Fox N, Gitlin LN, Howard R, Kales HC, Larson EB, Ritchie K, Rockwood K, Sampson EL, Samus Q, Schneider LS, Selbæk G, Teri L, Mukadam N, 2017. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet 390, 2673–2734. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löckenhoff CE, Terracciano A, Bienvenu OJ, Patriciu NS, Nestadt G, McCrae RR, Eaton WW, Costa PT, 2008. Ethnicity, education, and the temporal stability of personality traits in the East Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. J. Res. Personal 42, 577–598. 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchetti M, Terracciano A, Stephan Y, Sutin AR, 2016. Personality and cognitive decline in older adults: data from a longitudinal sample and meta-analysis. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci 71, 591–601. 10.1093/geronb/gbu184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciano M, Hagenaars SP, Davies G, Hill WD, Clarke T-K, Shirali M, Harris SE, Marioni RE, Liewald DC, Fawns-Ritchie C, Adams MJ, Howard DM, Lewis CM, Gale CR, McIntosh AM, Deary IJ, 2018. Association analysis in over 329,000 individuals identifies 116 independent variants influencing neuroticism. Nat. Genet 50, 6–11. 10.1038/s41588-017-0013-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuijten MB, van Assen MALM, Veldkamp CLS, Wicherts JM, 2015. The replication paradox: Combining studies can decrease accuracy of effect size estimates. Rev. Gen. Psychol 19, 172–182. 10.1037/gpr0000034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pedditizi E, Peters R, Beckett N, 2016. The risk of overweight/obesity in mid-life and late life for the development of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Age Ageing 45, 14–21. 10.1093/ageing/afv151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters R, Ee N, Peters J, Booth A, Mudway I, Anstey KJ, 2019. Air pollution and dementia: a systematic review. J. Alzheimers Dis 70, S145–S163. 10.3233/JAD-180631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Luo J, Briley DA, Chow PI, Su R, Hill PL, 2017. A systematic review of personality trait change through intervention. Psychol. Bull 143, 117–141. 10.1037/bul0000088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüegger D, Stieger M, Flückiger C, Allemand M, Kowatsch T, 2017. Leveraging the potential of personality traits for digital health interventions: a literature review on digital markers for conscientiousness and neuroticism. ETH Zurich. 10.3929/ethz-b-000218434 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P, 2007. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak 7. 10.1186/1472-6947-7-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz SA, Gordon BA, Mishra S, Su Y, Morris JC, Ances BM, Duchek JM, Balota DA, Benzinger TLS, 2019. Association between personality and tau-PET binding in cognitively normal older adults. Brain Imaging Behav 10.1007/s11682-019-00163-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC, 2018. Personality and incident Alzheimer’s Disease: Theory, evidence, and future directions. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 10.1093/geronb/gby063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp ES, Reynolds CA, Pedersen NL, Gatz M, 2010. Cognitive engagement and cognitive aging: is openness protective? Psychol. Aging 25, 60–73. 10.1037/a0018748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp SI, Aarsland D, Day S, Sønnesyn H, Alzheimer’s Society Vascular Dementia Systematic Review Group, Ballard, C., 2011. Hypertension is a potential risk factor for vascular dementia: systematic review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 26, 661–669. 10.1002/gps.2572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegler IC, Dawson DV, Welsh KA, 1994. Caregiver ratings of personality change in Alzheimer’s disease patients: A replication. Psychol. Aging 9, 464–466. 10.1037/0882-7974.9.3.464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsohn U, Nelson LD, Simmons JP, 2014. P-curve: A key to the file-drawer. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen 143, 534–547. 10.1037/a0033242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsohn U, Simmons JP, Nelson LD, 2015. Better P-curves: Making P-curve analysis more robust to errors, fraud, and ambitious P-hacking, a Reply to Ulrich and Miller (2015). J. Exp. Psychol. Gen 144, 1146–1152. 10.1037/xge0000104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux A, Yerramalla MS, Sabia S, Kivimäki M, Fayosse A, Dugravot A, Dumurgier J, 2020. Association of big-5 personality traits with cognitive impairment and dementia: a longitudinal study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health jech-2019–213014 10.1136/jech-2019-213014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley TD, Doucouliagos H, 2014. Meta-regression approximations to reduce publication selection bias. Res. Synth. Methods 5, 60–78. 10.1002/jrsm.1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan Y, Boiché J, Canada B, Terracciano A, 2014. Association of personality with physical, social, and mental activities across the lifespan: Findings from US and French samples. Br. J. Psychol 105, 564–580. 10.1111/bjop.12056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan Y, Sutin AR, Luchetti M, Caille P, Terracciano A, 2018. Polygenic Score for Alzheimer Disease and cognition: The mediating role of personality. J. Psychiatr. Res 107, 110–113. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J, Carpenter J, Rucker G, Harbord RM, Schmid CH, Tetzlaff J, Deeks JJ, Peters J, Macaskill P, Schwarzer G, Duval S, Altman DG, Moher D, Higgins JPT, 2011. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 343, d4002–d4002. 10.1136/bmj.d4002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stieger M, Wepfer S, Rüegger D, Kowatsch T, Roberts BW, Allemand M, 2020. Becoming more conscientious or more open to experience? Effects of a two‐week smartphone‐based intervention for personality change. Eur. J. Personal 34, 345–366. 10.1002/per.2267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strickhouser JE, Zell E, Krizan Z, 2017. Does personality predict health and well-being? A metasynthesis. Health Psychol. 36, 797–810. 10.1037/hea0000475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB, 2000. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 283, 2008–2012. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Ferrucci L, Zonderman AB, Terracciano A, 2011. Personality and obesity across the adult life span. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 101, 579–592. 10.1037/a0024286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Terracciano A, Deiana B, Naitza S, Ferrucci L, Uda M, Schlessinger D, Costa PT, 2010. High Neuroticism and low Conscientiousness are associated with interleukin-6. Psychol. Med 40, 1485–1493. 10.1017/S0033291709992029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Terracciano A, 2018. Facets of conscientiousness and objective markers of health status. Psychol. Health 33, 1100–1115. 10.1080/08870446.2018.1464165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano A, An Y, Sutin AR, Thambisetty M, Resnick SM, 2017a. Personality Change in the Preclinical Phase of Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 1259–1265. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano A, Löckenhoff CE, Crum RM, Bienvenu OJ, Costa PT, 2008. Five-Factor Model personality profiles of drug users. BMC Psychiatry 8, 1–10. 10.1186/1471-244X-8-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano A, Stephan Y, Luchetti M, Albanese E, Sutin AR, 2017b. Personality traits and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. J. Psychiatr. Res 89, 22–27. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano A, Sutin AR, An Y, O’Brien RJ, Ferrucci L, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM, 2014. Personality and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: New data and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 10, 179–186. 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Aert RCM, Wicherts JM, van Assen MALM, 2019. Publication bias examined in meta-analyses from psychology and medicine: A meta-meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 14, e0215052. 10.1371/journal.pone.0215052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viechtbauer W, 2010. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. J. Stat. Softw 36. 10.18637/jss.v036.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H-X, Karp A, Herlitz A, Crowe M, Kareholt I, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L, 2009. Personality and lifestyle in relation to dementia incidence. Neurology 72, 253–259. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000339485.39246.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir DR, Wallace RB, Langa KM, Plassman BL, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Duara R, Loewenstein D, Ganguli M, Sano M, 2011. Reducing case ascertainment costs in U.S. population studies of Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and cognitive impairment-Part 1. Alzheimers Dement. 7, 94–109. 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Arnold SE, Schneider JA, Kelly J, Tang Y, Bennett DA, 2006. Chronic psychological distress and risk of Alzheimer’s Disease in old age. Neuroepidemiology 27, 143–153. 10.1159/000095761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, Li Y, Bienias JL, de Leon CFM, Evans DA, 2005. Proneness to psychological distress and risk of Alzheimer disease in a biracial community. Neurology 64, 380–382. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149525.53525.E7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Arnold SE, Bienias JA, Bennett DA, 2007. Conscientiousness and the incidence of Alzheimer Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 64, 1204–1212. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2019. Risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia: WHO guidelines. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M, Xu W, Ou Y-N, Cao X-P, Tan M-S, Tan L, Yu J-T, 2019. Diabetes mellitus and risks of cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 144 prospective studies. Ageing Res. Rev 55, 100944. 10.1016/j.arr.2019.100944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong G, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Guo JJ, Zhao Y, 2015. Smoking is associated with an increased risk of dementia: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies with investigation of potential effect modifiers. PLOS ONE 10, e0118333. 10.1371/journal.pone.0118333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.