Abstract

In mammalian genomes, cytosine methylation occurs predominantly at CG (or CpG) dinucleotide contexts. As part of dynamic epigenetic regulation, 5-methylcytosine (mC) can be erased by active DNA demethylation, whereby ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes catalyze the stepwise oxidation of mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (hmC), 5-formylcytosine (fC), and 5-carboxycytosine (caC), thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG) excises fC or caC, and base excision repair yields unmodified cytosine. In certain cell types, mC is also enriched at some non-CG (or CH) dinucleotides, however hmC is not. To provide biochemical context for the distribution of modified cytosines observed in biological systems, we systematically analyzed the activity of human TET2 and TDG for substrates in CG and CH contexts. We find that while TET2 oxidizes mC more efficiently in CG versus CH sites, this context preference can be diminished for hmC oxidation. Remarkably, TDG excision of fC and caC is only modestly dependent on CG context, contrasting its strong context dependence for thymine excision. We show that collaborative TET-TDG oxidation-excision activity is only marginally reduced for CA versus CG contexts. Our findings demonstrate that the TET-TDG-mediated demethylation pathway is not limited to CG sites and suggest a rationale for the depletion of hmCH in genomes rich in mCH.

Keywords: 5-methylcytosine, DNA methylation, base excision repair, cytosine-guanine dinucleotides, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine

INTRODUCTION

The propagation and dynamics of cytosine base modifications play critical roles in mammalian transcriptional regulation, with significant influences on cell differentiation and development. 5-methylcytosine (mC), the most common epigenetic mark, primarily occurs at cytosine-guanine (CG or CpG) dinucleotides, with 60–80% of genomic CG sites methylated in most cell types. In most differentiated cells, non-CG dinucleotides, also known as CH (or CpH, H=A,C,T), are rarely methylated. However, in some cell types, including embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and neuronal cells, as much as 2–6% of CH sites can be methylated.1, 2 In these cell types, methylated CH (mCH) sites can therefore account for up to half of all methylated cytosines in the genome, due to the relative underrepresentation of CG dinucleotides across the genome as a whole.3

Importantly, mC is not the only relevant mark that occurs on cytosine bases in mammalian genomes. In all cell types, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (hmC) has also been identified as a stable modification;4–6 it is prevalent in ESCs and can accumulate to levels as much as 10–30% those of mC in neurons.7 The ten-eleven translocation (TET) family of enzymes are iron (II) and α-ketoglutarate(α-KG)-dependent dioxygenases responsible for introducing this mark by oxidizing mC.4 The hmC product can then be further oxidized to yield 5-formylcytosine (fC), or yet again to 5-carboxycytosine (caC).8–10 While independent epigenetic roles for each of the oxidized mC bases (ox-mCs) remain subject to ongoing studies, ox-mCs have been strongly implicated in pathways for DNA demethylation. The presence of an ox-mC on one strand of a CG•CG dinucleotide base pair antagonizes maintenance methylation of the opposite strand cytosine by DNMT1, promoting passive demethylation following DNA replication.11 The higher oxidation states, fC and caC, can also be removed by thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG),8, 12 and subsequent steps of base excision repair (BER) yield unmodified cytosine in place of the modified base, providing a complete biochemical pathway for active demethylation of mC.13 The relative importance of passive dilution of ox-mCs versus their active excision by TDG remains a matter of debate. Evidence points to each pathway employed in distinct biological contexts, such as passive dilution during early embryogenesis, or TDG-dependent excision in somatic cell reprogramming to pluripotent stem cells.14

Although non-CG methylation is robustly detected in ESCs and neuronal cells, the abundance of hmC at non-CG sites (hmCH) is more controversial, with different sequencing methodologies yielding varying results for the presence of hmCH in vivo. While oxidative bisulfite sequencing (oxBS-Seq) suggested detectable hmCH in neurons, 15 two other base-resolution hmC-sequencing methods, TET-assisted bisulfite-sequencing (TAB-seq) and APOBEC-coupled epigenetic sequencing (ACE-seq), indicated little detectable hmCH in both ESCs and neurons.16, 17 Nevertheless, there is general concordance between the methods that, compared to mC, the amount of hmC is far lower at non-CG relative to CG sites. There are two non-mutually exclusive explanations that might account for these observations. First, TET enzymes could be less efficient at oxidizing mC in non-CG contexts relative to CG sites, a preference that has been well documented.18, 19 Second, TET enzymes might have substantial activity for oxidizing hmC in a non-CG context (hmCH), and the resulting fCH or caCH may be susceptible to TDG excision and subsequent BER to yield unmodified CH, a hypothesis that has yet to be evaluated.

To date, the proficiency of TET-TDG-mediated active DNA demethylation at non-CG sites has not been established, as prior studies have largely focused on characterizing the activity of TET or TDG on modified cytosine in a CG context. Structural and biochemical studies of TET family enzymes provide some evidence regarding the impact of sequence context on oxidation. Employing the human TET2 construct (TET2-CS) used for a DNA-bound crystal structure, Hu et al. found that oxidation of mC is more efficient for mCG relative to mCA or mCC substrates.19 Based on their structure of TET2 bound to mCG-containing DNA, they proposed that substitution of guanine by another base at the +1 position (3′ of mC) impairs base-stacking interactions with Y1294 in the active site, resulting in diminished activity. A sequencing-based screen suggested that mouse TET1 preferentially generates hmC from mC in a CG context, with some activity in CH contexts.20 However, biochemical studies on other TET homologs suggest a target base in a non-CG sequence context can be efficiently oxidized: While a TET homolog from N. gruberi, NgTET1, generally prefers a CG context for all three substrates (mC, hmC, fC), it can oxidize DNA containing mCG and mCA with comparable efficiency.21 Thus, although the activity of human TET enzymes on mC has been characterized, a comparison of all three modified cytosine substrates (X=mC, hmC, fC) in each of the four dinucleotide sequence contexts (XN, N=G,A,C,T) has yet to be achieved.

Likewise, the sequence preference of TDG for excision of fC and caC is an important open question. The effect of the +1 base on TDG’s activity has been best characterized within the context of its excision of thymine that is mismatched with guanine. TDG exhibits much higher activity if the +1 base is G, giving an overall preference of TG >> TA > TC > TT.22, 23 These findings are consistent with a role for TDG in countering mutations caused by mC deamination, because it excises thymine most efficiently from DNA contexts in which mC is most abundant (a CG context). Recent 19F NMR studies indicate the sequence-dependence of thymine excision is attained through regulation of dT nucleotide flipping out of duplex DNA, a dramatic conformational change that precedes base excision; TDG-mediated flipping is more favorable for a mismatched T if the +1 base is G rather than another base.23 Crystal structures of TDG (residues 82–308) in complex with DNA containing a G•U mismatch reveal TDG interactions with a guanine at the +1 position relative to the flipped uracil.24 While structures of TDG bound to DNA containing fC or caC indicate that TDG forms similar contacts with a +1 G, the impact of sequence context on excision of fC or caC has not been previously evaluated.25–28

Here, we explore the preferences of TET and TDG activity on modified cytosines in CG versus CH sequence contexts, to inform their role in shaping the epigenome. We show that human TET2 favors a CG context for oxidizing mC to hmC, as previously established, but the extent of the context preference is diminished for the subsequent oxidation of hmC. While sequence context is known to dramatically impact TDG excision of T from G•T mispairs, we show, surprisingly, that TDG excision of fC and caC is relatively independent of the +1 base. We also show that the collaborative oxidation-excision activity of TET and TDG efficiently processes mC and hmC in a non-CG context, offering a potential biochemical rationale for the relative depletion of hmCH in genomes that are otherwise rich in mCH modifications.

RESULTS

Impact of +1 base on TET oxidation

Our goal was to systematically evaluate the preference of TET and TDG for their modified cytosine substrates in all possible +1 sequence contexts. To this end, we first generated a complete series of sixteen DNA substrates, such that each of the four modified cytosine bases (X = mC, hmC, fC, or caC) is presented in each of four possible sequence contexts with regard to the +1 base (N) positioned 3′ to the modified C (XG, XA, XC, XT) (Figure 1). Within this 28-bp substrate series (S28), the DNA containing mC, hmC, or fC can serve as substrates for TET-mediated oxidation, with hmC, fC and caC serving as product controls. We also generated a corresponding set of four DNA duplexes containing T in place of the modified C base, giving G•T mismatch substrates with four possible bases at +1 relative to the mismatched T (Figure 1B). This series, together with corresponding duplexes containing fC or caC, provide a complete series to evaluate the activity preferences of TDG.

Figure 1. Substrate Design.

(A) Duplex DNA substrates in the S28 series contain a single modified cytosine (X) and one of four potential +1 bases (N), giving an XN dinucleotide; the complementary strand contains G across from X and the appropriate Watson-Crick partner (N′) across from N. (B) The series comprehensively surveys the three natural TET substrates (mC, hmC, fC) and three natural TDG substrates (fC, caC, T). The top row constitutes substrates in a CG context, while the lower three rows encompass CH variants for these substrates.

To investigate the impact of the +1 base on TET reactivity, we chose to use the crystal structure variant of human TET2 (TET2-CS). TET2-CS is a more stable construct than either the catalytic domain or full-length enzyme, allowing a larger range of activity to be profiled. Additionally, substrate preferences observed with this construct have been previously shown to be consistent with that of the TET2 construct with a full catalytic domain.29, 30 Using TET2-CS, reactions were performed in conditions previously optimized for overall activity with enzyme:DNA ratios that permit discrimination of substrate preferences.30, 31 After reaction with TET2-CS, the oligonucleotides were purified, degraded to individual nucleosides, and then analyzed by LC/MS/MS to quantify the residual substrate or newly formed ox-mC products (Figure 2A).32

Figure 2. TET activity for modified cytosines in CG and CH contexts.

(A) Reactions were performed with 1 ¼M DNA substrate containing an XN dinucleotide and 1.5 ¼M human TET2-CS at 37 °C. The products were degraded to individual nucleosides and the modified cytosine base were quantified by LC/MS/MS. (B) The fraction of each modified cytosine base at the end of the reaction are shown (including substrate and products). Error bars denote the standard deviation associated with 2 to 3 independent replicates from each condition. (C) The data from (B) is shown using the alternative total oxidation events (TOE) metric, whereby the detection of caC accounts for three oxidation events, fC two, and hmC one. The data are then normalized to the TOE for the optimal mCG substrate. The right axis (red) represents the calculated ratio of TOE for the hmC versus mC substrates and the value of this ratio is denoted with a star over each substrate series.

Focusing first on mC-containing substrates (mCN), mCG is the most reactive substrate with TET2-CS, as anticipated (Figure 2B). Under conditions where only 9% of mCG remains unreacted, the best of the three mCH substrates is mCA, which has 55% of substrate remaining, with comparable conversion of the mCC substrate, and less oxidation of the mCT substrate. Notably, for all three mCH substrates we could readily detect the generation of caC, which results from three successive oxidations of mC. Thus, despite the large reduction in substrate consumption relative to mCG, the mCH substrates can yield as much as half the amount of caC as that observed for the mCG substrate. Given the challenges posed by assessing the three linked oxidation products, we also examined product formation using a different, established metric:29, 31 the total oxidation events (TOE). The TOE metric dictates that, for an mC substrate, hmC represents one turnover, fC represents two turnovers, and caC represents three turnovers (Figure 2C). By normalizing the data to that of mCG, we see that mCA only experiences 37% of the TOE relative to mCG, with mCC similarly showing 42% relative TOE, and mCT having only 21% relative TOE (Figure 2C). Given that the high degree of substrate conversion for mCG might have led to an underestimate of its favored status, we also repeated our analysis with the favored mCG substrate and the least favored mCT substrate using a lower enzyme:substrate ratio.

We next moved to evaluating the reactivity of hmC-containing substrates as a function of sequence context (Figure 2B). Consistent with prior results focused only on the CG context, TET2-CS shows a preference for oxidation of the mCG substrate over the hmCG substrate as measured by substrate consumption. Surprisingly, for sequence contexts other than CG, the consumption of mCH and hmCH substrates are largely similar to one another (Figure 2B). As a means for comparing the relative preference for mC versus hmC as a function of the +1 base, we plotted the normalized TOE for each substrate, where normalization accounts for the fact that mC substrates can be oxidized three times, while hmC can only be oxidized twice. As seen for mC oxidation, activity is lowest for hmC in an XT context (hmCT). However, the maximal difference in TOE among hmC substrates is 1.8-fold (hmCG, hmCT), compared to a 5-fold maximal TOE difference for mC substrates (mCG, mCT) (Figure 2C). As another means of comparing reactivity, we examined the ratio of normalized TOE for hmC versus mC substrates (Figure 2C). For hmCG versus mCG this ratio is 0.39, which suggests that mC is favored by ~2.5-fold over hmC in the CG context, in terms of normalized overall oxidation events. By contrast, TOE ratios for the other mC and hmC substrate pairs are closer to unity (0.68 to 1.09), suggesting a diminished preference for mC over hmC in non-CG contexts.

Turning to the fC substrates, consistent with prior work analyzing mC, hmC and fC substrate preference in a CpG context, we find that fC is the least preferred substrate for TET2, confirming the overall reactivity pattern of mCG > hmCG > fCG. Unlike the results for hmCN substrate series, fCG is favored over the other three fCH substrates (Figure 2B, 2C). The fCN substrate series thus more closely tracks with the mCN series in terms of +1 position substrate preference. Integrating across the CH substrates series, the overall reactivity pattern appears to be mCH ≥ hmCH > fCH, suggesting a modest but notable difference relative to the CG substrate series.

Impact of +1 base on TDG excision activity

As with TET, previous studies of TDG activity on fC and caC have focused on excision of these bases from a CG context. To inform the proficiency of active demethylation at CH sites, we investigated the impact of the +1 base (N) on TDG excision of fC from fCN substrates and of caC from caCN substrates (Figure 3A). For comparison, we also determined the impact of the +1 base (N) on TDG excision of thymine from four TN substrates, where T is mismatched with G. Single turnover kinetics experiments were performed under saturating enzyme conditions, giving rate constants (kobs) that are not impacted by substrate engagement, product release, or product inhibition and thus approximate the maximal rate of product formation (kmax).

Figure 3. Dependence of TDG activity on the +1 base.

(A) Duplex DNA substrates (0.5 ¼M), each containing a target base (X) paired with G and in one of four XN dinucleotide contexts, were reacted with human TDG (≥1.0 ¼M) under single turnover conditions at 37 °C. Cleavage of the DNA at TDG-produced abasic enables product quantification by HPLC. (B) TDG activity (kmax) for each substrate is shown on log-scale, with values reported in Supplementary Figure 1C. Error bars show the standard deviation associated with three or more independent experiments. Shown on the right are kmax values for an XY substrate relative to that for XG in each series (T, fC, caC).

We find that TDG excision of T from a G•T mispair is highly dependent on the base at the +1 site, where activity for a TG substrate is 10- to 75-fold greater than that for the three other TN substrates (Figure 3B, Supplementary Figure 1C). The activity trend for these substrates (TG >> TA > TC > TT) is identical to that observed in previous studies that employed a different TDG construct or were performed at a lower temperature.22, 23 Notably, the rate constants for thymine excision observed here for full length TDG are in excellent agreement with those for a smaller TDG construct, TDG82–308, using the same substrates and reaction conditions (37 ºC).23 As noted previously,23 we find here that the dependence of thymine excision on the +1 base is sharply reduced at 37 ºC relative to 23 ºC, where activity for a TG substrate is 37- to 580-fold higher than for the three other TN substrates.

In contrast to the strong context dependence for TDG excision of T from a G•T mispair, the impact of the +1 base is moderate for excision of fC and caC. Indeed, when compared to the fCG substrate, kmax is reduced by only 1.4-, 1.8-, and 4.7-fold for fCA, fCC, and fCT, respectively (Figure 3B, Supplementary Figure 1). Similar results are observed for caC excision; compared to caCG, kmax is reduced by merely 1.3-, 1.7-, and 3.4-fold for caCA, caCC, and caCT, respectively. These findings reveal that the context dependence of TDG activity (kmax) is roughly an order of magnitude lower for excision of fC and caC relative to mismatched T. Moreover, the results indicate TDG can efficiently remove fC and caC within non-CG contexts.

Impact of +1 base on TET and TDG activities in a different sequence context

The biochemical experiments with isolated TET and TDG suggest that the two enzymes may act together to efficiently oxidize and remove modified cytosines in CH contexts. While we find that TET2 oxidizes mC more efficiently in mCG versus mCH contexts, this context (+1 base) dependence is diminished for hmC oxidation, where activity for hmCG and hmCH substrates are comparable. Meanwhile, TDG excision of fC and caC proceeds with relatively little dependence on sequence context (+1 base). Together, these results suggest that although hmC is less likely to be generated in a CH versus a CG context, once hmC is produced, it can be efficiently oxidized and removed by the combined activity of TET and TDG.

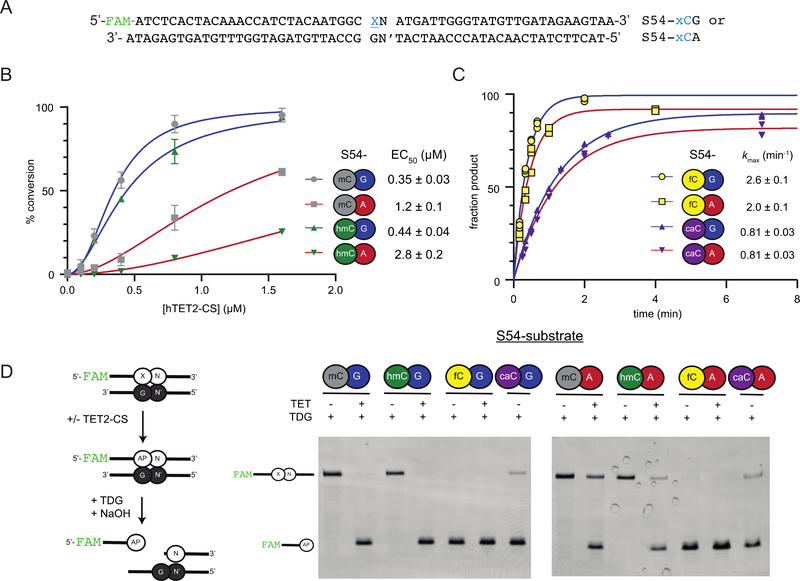

Given that our results were based on a single S28 substrate series, however, we next aimed to explore the generality of our observations using a substrate series of different length and sequence context. As that the most prevalent form of non-CG methylation is mCA, we developed a chemoenzymatic approach to generate a 54-bp substrate series (S54) with mC, hmC, fC or caC in either a XG or XA sequence context (Figure 4A, Supplementary Figure 2A). These substrates contain only one single modified cytosine in a larger sequence context distinct from that of the S28 series.

Figure 4. TET and TDG activity on alternative substrates in CG and CH contexts.

(A) Duplex DNA substrates in the S54 series contain a single modified cytosine (X) and either G or A +1 bases (N), giving an XG or XA dinucleotide; the complementary strand contains G across from X and the appropriate Watson-Crick partner (N′) across from N. (B) Duplex DNA substrates (0.5 ¼M) containing mCG, mCA, hmCG, or hmCA dinucleotides were reacted with serial dilutions of human TET2-CS (0.1–1.6 ¼M) or no TET2-CS, at 37 ºC for 30 min using assay conditions that either report on mC oxidation or hmC oxidation. Assay schematic and representative gels are given in Supplementary Figure 2B and 2C. Reactions were performed in triplicate. Shown is the curve resulting from a sigmoidal fit for product formation as a function of TET2-CS, with calculated enzyme concentration needed for conversion of half of the substrate (EC50) noted. (C) Duplex DNA substrates (0.5 ¼M) were reacted with human TDG (≥1.0 ¼M) under single turnover conditions at 37 °C. Cleavage of the DNA at TDG-produced abasic enables product quantification by HPLC. Reactions were performed in triplicate for each substrate and the data were fitted to a single exponential equation to obtain an observed rate constant (kmax). (D) Duplex DNA substrates (0.5 ¼M) on S54 series were reacted with or without human TET2-CS (3.5 ¼M) for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by TDG (1 ¼M) for 4 hrs at 37 ºC. Alkali-mediated cleavage of the DNA at TDG-produced abasic (AP) sites was then analyzed on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel as shown.

A strength of our S54 substrate design is that we can quantitatively track the efficiency of TET2-CS, using assays orthogonal to the LC-MS/MS approach employed to study the S28 substrate reactivity. To measure the relative efficiency of oxidation, we reacted the substrates with serial dilutions of the TET2-CS and analyzed for product formation with two different coupled assays that can specifically report on either mC or hmC oxidation (Supplementary Figure 2). Using this approach, we fit product formation to a sigmoidal dose-response curve to determine the amount of TET2-CS needed to consume half of the substrate (EC50) under fixed reaction conditions. The results suggest some similarities in trends observed with the S28 series, but also highlight that sequence context and substrate length can impact TET2-CS activity (Figure 4B). Consistent with prior work and our S28-series, reactivity is decreased for S54-hmCG relative to S54-mCG; however, S54-hmC is only 1.25-fold less preferred than S54-mC. Comparing the influence of the +1 position, reactivity of mC is diminished 3.5-fold with S54-mCA relative to S54-mCG, which is comparable to the 2.7-fold reduction in TOE observed with S28-mCA relative to S28-mCG. Reactivity with hmC was also observed, but showed a 6.3-fold reduction in product formation with S54-hmCA relative to S54-hmCG, larger than the 1.7-fold reduced TOE observed for S28-hmCA relative to S28-hmCG. The results suggest that mC and hmC reactivity can differ as a function of sequence context or substrate length, while also confirming that TET2 activity can have significant activity on hmC in a non-CG context.

Next, using our single turnover kinetic experimental approach, we turned to assessing the reactivity of TDG and calculated the rate of TDG-mediated excision (kobs) for fC and caC in the S54 substrate sequence context (Figure 4C). Under these conditions, S54-fCA is only 1.3-fold less reactive than S54-fCG, while the reactivities of S54-caCA and S54-caCG are indistinguishable. Thus, the S54 substrate series recapitulate patterns observed with S28 substrates with TDG, demonstrating efficient excision of fC and caC from non-CG substrates.

Impact of +1 base on TET/TDG collaboration in the active DNA demethylation pathway

As the proficiency of active demethylation in a CH context has not been previously demonstrated, we first aimed to demonstrate whether TET2-CS and TDG could work in series when starting with mCH. To this end, we first looked at reactivity of the complete S54 substrate series with these enzymes (Fig. 4D). As expected for substrates in a CG context, we observed that oxidation of either S54-mCG or S54-hmCG by TET2-CS readily convert these oligonucleotides into substrates for TDG-mediated excision. Critically, we also found that the activities of TET and TDG in series were also able to support oxidation and excision on S54-mCA and S54-hmCA, newly recapitulating the active DNA demethylation pathway using substrates in non-CG context.

We next wished to confirm that enzymatic activities could be coupled to support the concerted oxidation and excision of mC and hmC in non-CG context. To this end, we used our S28-substrates and explored co-incubation with both TET2-CS and TDG (Figure 5A). Subsequent treatment with AP endonuclease was included to cleave the DNA backbone at abasic sites generated by the collaborative action of TET and TDG, allowing for electrophoretic quantification of product formation. Using this approach with S28-mCG results in robust conversion of the target mC base to an abasic site (Figure 5B–C, Supplementary Figure 3), consistent with prior efforts to reconstitute the DNA demethylation pathway in vitro.33 Notably, S28-mCA DNA is also efficiently processed by TET2 and TDG, demonstrating that active DNA demethylation is proficient at mCA sites in vitro, as predicted from our characterization of their isolated activities. To compare the efficiency of oxidation-excision when starting from hmC relative to mC, TET2-CS/TDG co-incubations were also performed with hmCG and hmCA substrates. Considering the results with substrates in a CG context first, the combined oxidation-excision activity for S28-hmCG is equivalent to that for S28-mCG. For the CA context, we note that the combined oxidation-excision activity is greater for S28-hmCA relative to S28-mCA. Notably, for the S28 substrate series, the effect of sequence context (+1 base) on the combined oxidation-excision activity is greater for mC relative to hmC; activity is reduced by 2-fold for S28-mCA versus S28-mCG and by only 1.5-fold for S28-hmCA versus S28-hmCG. Taken together, these results indicate that TET2-TDG demethylation can be proficient in a non-CG context.

Figure 5. Combined TET2-TDG activity for substrate bases in CG and CA contexts.

(A) Duplex DNA substrates (0.3 ¼M) containing S28-mCG, mCA, hmCG, or hmCA dinucleotides were reacted with human TET2-CS (0.6 ¼M) and TDG (1 ¼M), or with TDG alone, for 4 h at 37 °C. Cleavage of the DNA at TDG-produced abasic (AP) sites was then analyzed on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel. (B) Shown is a representative gel of each substrate with TET2 and TDG together or TDG alone, with two additional independent replicates provided in Supplementary Figure 3. (C) The fraction of each substrate that was cleaved after incubation with TET and TDG is shown. The standard deviation associated with three independent replicates from each condition are given.

DISCUSSION

While a greater fraction of CG dinucleotides are modified relative to CH dinucleotides, modifications to CH can be prevalent at the genome-wide level. The relative depletion of hmCH observed in genomes with abundant mCH motivated our efforts to investigate the activity of TET and TDG on modified cytosine bases in a non-CG context. Our findings reveal that for both TET and TDG, the impact of the +1 (or 3′) base on catalytic activity can vary dramatically, depending on the substrate base. For example, the dependence of TET activity on the +1 base is relatively high for mC and fC for some substrates, but this selectivity for a CG context diminished for hmC. For TDG, the dependence of activity on the +1 base is an order of magnitude lower for excision of fC and caC relative to excision of a mismatched T. Building on these observations, we show for the first time that the combined activity of TET2 and TDG can efficiently perform active DNA demethylation for modified cytosines in a non-CG context. These results have implications for our understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in substrate discrimination by TET and TDG and provide a biochemical rationale for the relative prevalence of cytosine modifications in CG versus CH contexts in the mammalian genome.

Potential molecular mechanisms governing TET and TDG selectivity

By analyzing our biochemical results in the context of available crystal structures, we can speculate about the underlying mechanisms regulating the sequence preferences of TET and TDG. Available structures of TET2-CS in complex with DNA suggest differences in how the enzyme engages with mCG- versus hmCG-containing substrates.19, 34 In both structures, the 3′-G forms base stacking interactions that could enhance activity. However, the structures also suggest how the effect of the +1 base could be diminished for hmC oxidation. Although TET interactions with the substrate base are generally preserved for its three substrates (mC, hmC, fC) in the various structures, hmC is proposed to have additional hydrogen bonding interactions from the 5-hydroxymethyl group. These interactions between the 5-hydroxymethyl and either the N4 amino group of cytosine or Arg1261 of TET2-CS can alter the geometry between the active site iron (II) and the proton that needs to be abstracted from the C5 substituent. As molecular dynamics studies have suggested that proton abstraction is the rate limiting step,18, 35 it is feasible that hmC orientation has a dominant impact on oxidation that modulates effects of the +1 base. By contrast, mC, being more optimally engaged and without conformational restriction, could be more significantly impacted by the +1 base. Other aspects of TET-mediated oxidation have yet to be fully evaluated either by structure or molecular dynamics and could account for differences in reactivity for substrates in a CG versus CH context. By evaluating two different substrate series, we also demonstrate that factors such as sequence context and substrate length can alter the relative reactivities of mC and hmC. As observed for many DNA modifying enzymes, TET enzymes engage with their target base by flipping the base out of duplex DNA and engaging with the backbone of nucleotides outside of the target base. The structure of TET2-CS suggests potential stabilization of the “orphaned” base in the complementary strand, and the base flipping of substrates may depend on identity of the neighboring base,19 as is the case for TDG.

One notable aspect of our analysis was that we could readily detect the formation of all three oxidation products – hmC, fC and caC – from all three S28-mCH substrates, in some cases without accumulation of large amounts of hmC. There has been debate about whether TET enzymes can generate higher oxidation products in a single enzyme-DNA encounter.31, 36 Our finding that caC can be generated from less favored substrates is consistent with the possibility that the enzyme can act in an iterative manner. Such activity would likely involve maintenance of non-specific DNA contacts, flipping of intermediate ox-mC products out of the active site and into duplex DNA, and exchange of the succinate byproduct for additional α-KG substrate, before initiation of the next catalytic cycle.

For TDG, previous studies suggest a plausible explanation for the observation here that the impact of sequence context (+1 base) on base excision activity is vastly reduced for fC and caC relative to thymine. Using 19F NMR, we recently found that TDG attains its stringent context specificity for thymine excision largely by regulating the flipping of dT nucleotides into its active site.23 Indeed, the population of flipped dT nucleotide is strongly dependent on the +1 base and is greatest for a TG dinucleotide.23 While similar 19F NMR studies of target base flipping have not been reported for fC or caC, results of such studies into the context dependence of uracil flipping are informative. Mismatched uracil (G•U) was found to be predominantly flipped into the TDG active site regardless of the +1 base, which aligns with findings that the +1 base has a much lower effect on the excision of U versus T.22, 23 Notably, TDG also binds with 40-fold higher affinity to DNA containing a G•U relative to a G•T mispair,37 consistent with the 19F NMR findings that flipping is far more stable for U relative to T, which could be due to steric effects involving the methyl substituent of T. By comparison, TDG binds G•fC and G•caC DNA with 4- to 7-fold greater affinity than G•T DNA38 suggesting that, relative to T, fC and caC flip with higher stability into the TDG active site. This idea is supported by strong interactions formed by TDG with the formyl and carboxyl groups of fC and caC, respectively.25–28 While crystal structures indicate that TDG interacts with the +1 G adjacent to flipped fC or caC, our findings here indicate the contacts are likely not critical for base flipping or cleavage. These observations seem reasonable from a biological perspective. The strict dependence of thymine excision on the +1 base could enhance TDG selectivity for the very rare thymine bases that arise via mC deamination and thus could minimize its action on the vast background of thymine in normal A•T base pairs or on thymine bases in polymerase-generated mismatched pairs. In contrast, context specificity is not likely necessary for excision of fC or caC.

Biological implications of intrinsic TET and TDG substrate preferences

The abundance of various modified cytosines in the genome as a function of cell type and development is a critical area of ongoing exploration. While mC is generated predominantly at CG dinucleotides, mC is also commonly found in CH contexts in certain cell types, particularly in neurons and ESCs. Although a lower percentage of CH sites are methylated, up to half of the total mC marks in these cells can reside in these non-CG contexts, given the relative depletion of CG relative to non-CG dinucleotides in mammalian genomes.1–3 The distribution of mC bases raises a conundrum when considering the localization of hmC. By mass spectrometry approaches, hmC is the most abundant of ox-mCs, with levels approaching 10–30% that of mC in some cell types.5, 7 Nonetheless, sequencing-based approaches highlight that the vast majority of hmC is found in a CG context (hmCG). For example, in cortical excitatory neurons, ~38% of mC is in a CH context, while only ~2.5% of hmC is found in a CH context (Figure 6A).17

Figure 6. Model for modified cytosine distribution in CG versus CH contexts.

(A) The cycle of DNA demethylation involves the action of DNA methyltransferases (DNMT), TET-mediated oxidation of mC and removal by TDG, followed by abasic (AP) site repair. Sequencing studies on excitatory neuronal genomes have revealed that although a significant fraction of mC is in an mCH context, there are relatively low levels of hmCH. (B) The intrinsic biochemical activities of TET and TDG can in part account for the relative depletion of hmCH in mCH-rich genomes. The generation of hmCH from mC by TET enzymes and its removal by the coordinated actions of TET and TDG could potentially contribute to the distribution of modified bases in genomic DNA.

We posit that the depletion of hmCH in mCH-rich genomes could be related to both its generation and depletion (Figure 6B). Our results reveal how the intrinsic reactivities of TET and TDG can in part account for the low abundance of hmCH in genomes in a manner consistent with our hypothesis. Although TET enzymes are less likely to convert mCH to hmCH, once hmC is generated, downstream oxidation and TDG-mediated excision can be more proficient than would have been predicted from previously known activities. For TET, oxidation of hmC can occur readily in CH sequences. Similarly, TDG excises fC and caC with minimal dependence on the +1 base, where the effects on activity are <2-fold for the CA and CC contexts and <5-fold for the CT context, relative to the CG context. Thus, the TET oxidation and TDG excision steps needed for active demethylation are proficient in a CH context.

While our in vitro study newly indicates that active demethylation can be proficient at both CG and non-CG context, several aspects of the genomic distribution of modified cytosine bases remain unexplained. For one, the relative contribution of active versus passive DNA demethylation mechanisms remains unclear and is likely different across cell types. Although there has only been limited exploration with TDG deletion,39 there is evidence that neurons look to stably accumulate 5hmC,6 suggesting that turnover is limited in these postmitotic cells. By contrast, in ESCs, TDG loss can lead to accumulation of 5fC/5caC, suggesting a role for active demethylation in ongoing turnover of modified bases, and hmC mapping methods suggest that these dynamic changes extend to CH sites in ESCs.40, 41 Furthermore, although we show oxidation and excision of hmC could contribute to the depletion of hmCH, the factors that govern why hmC accumulates to high levels in cells in all contexts, while fC/caC are orders of magnitude lower, remain unclear and are important areas for future exploration.

Notably, the intrinsic enzyme substrate preferences explored here are likely to only provide part of the explanation for the abundance and distribution of ox-mCs in CG versus non-CG contexts. Additional factors at play beyond intrinsic enzyme preferences likely include genomic organization, protein partners, and other cellular processes. For example, while CG dinucleotides are relatively depleted in mammalian genomes, they are highly clustered. Thus, either localized or strand-processive activity of TET enzymes in CG-rich regions of the genome could lead to biased accumulation of hmCG. It is also possible that lower levels of hmCH in vivo are due to either mCH-specific proteins that block oxidation, similar to mCG binding proteins, or to hmC-binding factors that could protect hmCG sites from further oxidation. The latter idea is particularly intriguing as there have been several proteins found that bind hmC preferentially, but their purpose for doing so is not well established.42 Moreover, protein partners for TET enzymes or regions of TET outside of the core catalytic domain could regulate sequence preferences or catalytic processivity. For example, CG versus non-CG preferences could be impacted by IDAX1, whose CXXC domain is known to bind unmethylated CG-rich DNA and interact with TET2.43 Finally, although the different TET isoenzymes have thus far shown similar reactivity patterns,29, 44 it is possible that TET1, TET2, and TET3 activity differs with regard to the influence of the +1 base, in a manner that impacts genomic localization of modified cytosine bases. Further studies coupling mechanistic biochemical insights with sequencing-based approaches should help to elucidate how intrinsic enzyme factors and cellular factors together help govern the localization and abundance of various epigenetic marks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) preparation

ODNs were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) or, for those containing hmC, fC, or caC, from the Keck Foundation Biotechnology Resource Laboratory of Yale University. For the S28 substrate series, ODNs were purified by reverse phase HPLC23 and quantified by absorbance as described.22 Substrate and complement strands were mixed at a 1:1.2 ratio, for final duplex concentrations of 10 ¼M. Duplexes were annealed by heating to 95 °C for 3 min then cooling to 4 °C, in 1 °C increments for 30 s per step.

Chemoenzymatic generation of S54 substrate series

The S54 substrate series containing a single modified cytosine in either CG or CA context was generated by primer extension. A 5’-fluorescein (FAM) labeled top strand was annealed in equimolar ratio to a complementary strand containing either a C or a T at the variable position (S54-Comp-C and S54-Comp-T, respectively) at a total concentration of 150 ¼M. The primer/template was diluted to 1 ¼M and extension was performed with dATP/dGTP/dTTP (500 ¼M) and a 5-modified dCTP (5-mdCTP or 5-hmdCTP or 5-fdCTP or 5-cadCTP) (500 ¼M) (Trilink) using Klenow(exo-) DNA polymerase (15 u) (New England Biolabs, NEB) at 37 °C for 60 min in recommended buffer. S54-xCG and S54-xCA series DNA substrates were purified using DNA Clean and Concentrator Kit (Zymo), quantified, and used in subsequent enzymatic analysis. Notably, while the duplex region of the substrate is 54 bp, primer extension results in the addition of an untemplated 3’-A single base overhang.

TET2 purification

The crystallized human TET2 variant (TET2-CS), which includes residues 1129–1936, and a Gly-Ser linker in place of residues 1481–1843, was subcloned into a pFastBac1 vector for Sf9 insect cell expression, as described previously.32 Affinity purification was performed, utilizing an N-terminal FLAG tag, also as described previously.29 The enzyme concentration was determined by Bradford reagent via comparison to a BSA standard curve.

TDG purification

Full length human TDG was expressed in Escherichia coli (E. coli) and purified as previously described.24, 45 The enzyme concentration was determined by absorbance at 280 nm, using an extinction coefficient of ε280 = 31.5 mM-1cm-1.

TET reactions on S28 substrate series

Substrates were diluted in TET reaction buffer [50 mM HEPES (pH 6.5), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM α-KG, 1 mM DTT, and 2 mM sodium ascorbate], with fresh ammonium iron (II) sulfate (Sigma) added to 75 ¼M immediately prior to adding enzyme. Purified enzyme (11 ¼M) was added to yield final enzyme:substrate ratios of either 1.5 ¼M:1 ¼M or 0.75 ¼M:1 ¼M, in a total reaction volume of 25 ¼L. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min and quenched by addition of a premixed quenching solution [additional 25 ¼L of H2O, 100 ¼L of Oligo Binding Buffer (Zymo), and 400 ¼L of ethanol]. Reaction samples were purified using the Oligo Clean & Concentrator kit (Zymo) and eluted in 10 ¼L of Millipore water.

LC-MS/MS quantification of TET reaction products

The purified TET reaction products were analyzed by liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) after degradation to individual nucleosides as described previously.29 Briefly, samples were degraded to component nucleosides using the Nucleoside Digestion Mix (New England Biolabs, NEB), incubating for 4 h at 37 °C. The mixture was diluted 10-fold into 0.1% (v/v) formic acid, and approximately 2 pmol was loaded onto an Agilent 1200 Series HPLC instrument equipped with a 5 ¼m, 2.1 mm × 250 mm Supelcosil LC18-S analytical column (Sigma) pre-equilibrated to 45 °C in buffer A [0.1% formic acid]. The nucleosides were separated in a gradient of 0 to 10% buffer B [0.1% formic acid and 30% (v/v) acetonitrile] over 8 min at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. MS/MS was performed by positive ion mode ESI on an Agilent 6460 triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer. The signals of each nucleoside in a given sample were normalized to standard curves as described previously.29

TDG excision assay

The excision activity of TDG was monitored in a manner similar to previous studies.24 Briefly, the reactions with either S28 or S54 substrates were performed at 37 °C under saturating enzyme conditions ([E] > [S], [E] >> KD), such that the observed rate constants (kobs) reflect the maximal rate of product formation (kmax). For S28 substrates, reactions were initiated by adding TDG (1 ¼M) to DNA substrate (0.5 ¼M) in HEN.1 buffer [20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA]. For S54 substrates, reaction conditions were identical except that DNA substrate was at 2 nM. At each timepoint, aliquots were removed and immediately quenched by adding 50% (v:v) quench solution (0.3 M NaOH, 0.03 M EDTA). The samples were then heated for 3 min at 85 °C to quantitatively cleave the DNA backbone at abasic sites. For the S28 and S54 substrates, the resulting DNA fragments were resolved by denaturing anion-exchange UHPLC on a DNAPac PA200 RS column (Thermo Fisher), monitored by absorbance (260 nm) for the S28 substrates and by fluorescence for the S54 substrates (FAM-labeled). For both substrates series, peak areas were used to determine fraction product and the resulting progress curves (fraction product versus time) were fitted by non-linear regression to eq. 1.

| (1) |

where A is the amplitude, kobs is the observed rate constant, and t is the reaction time.

TET reactions on S54 substrate series

S54-substrates (0.50 ¼M) with mC, hmC and fC were incubated with TET2-CS (3.5 ¼M) or no TET2-CS, in TET reaction buffer with fresh ammonium iron (II) sulfate (Sigma) added to 75 ¼M immediately prior to adding enzyme and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Parallel reactions with S54-caCG and S54-caCA were performed only without TET. Reaction products were purified using the Oligo Clean and Concentrator kit (Zymo) and then incubated with TDG enzyme (1 ¼M), an excess that permits complete excision of fC and caC as validated by control samples, in TDG reaction buffer (20 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA) at 37 °C for 4 h. Samples were treated with fresh NaOH solution (166 mM final), and heated at 85 °C for 5 min. Reaction samples were then mixed with formamide gel loading dye, heated at 75 °C for 5 min, and then run on prewarmed 12% denaturing PAGE gel. Gels were imaged for FAM fluorescence using a Typhoon imager (excitation at 488 nm, emission at 520 nm).

Quantitative TET reactions on S54 mC substrates

Quantitative analysis of mC reactivity was performed as recently described.46 Briefly, S54-mCG and S54-mCA substrates (0.50 ¼M) were incubated with serial dilutions of TET2-CS (1.6, 0.8, 0.4, 0.2, 0.1 ¼M) or no TET2-CS, in presence of T4 β-glucosyltransferase (T4 β-GT, NEB, 0.2 U/¼L), UDP-glucose (40 ¼M). Reactions were performed in TET reaction buffer with fresh ammonium iron (II) sulfate (Sigma) added to 75 ¼M immediately prior to adding enzyme and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Parallel reactions with S54-hmCG and S54-hmCA was performed without TET to serve as a positive control for product detection. Reaction products were purified using the Oligo Clean and Concentrator kit (Zymo) and the samples were then digested with HaeIII (NEB) following the recommended protocol. The reaction samples were then run on prewarmed 12% denaturing urea (7 M) polyacrylamide gel (PAGE). Gels were imaged for FAM fluorescence using a Typhoon imager (excitation at 488 nm, emission at 520 nm) and the product and remaining substrate were quantified using ImageJ.

Quantitative TET reactions on S54 hmC substrates

S54-hmCG and S54-hmCA substrates (500 nM) were incubated with serial dilutions of TET2-CS (1.6, 0.8, 0.4, 0.2, 0.1 ¼M) or no TET2-CS, in TET reaction buffer with fresh ammonium iron (II) sulfate (Sigma) added to 75 ¼M immediately prior to adding enzyme and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Parallel reactions with S54-fCG and S54-fCA was performed without TET to serve as a positive control for product detection. Reaction products were purified using the Oligo Clean and Concentrator kit (Zymo) and then incubated with TDG enzyme (1 ¼M) and TDG reaction buffer (20 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA) at 37 °C for 4 h. Samples were treated with fresh NaOH solution (166 mM final), and heated at 85 °C for 5 min. Reaction samples were then mixed with formamide gel loading dye, heated at 75 °C for 5 min, and then run on prewarmed 12% denaturing PAGE gel. Gels were imaged for FAM fluorescence using a Typhoon imager (excitation at 488 nm, emission at 520 nm) and the product and remaining substrate were quantified using ImageJ.

TET/TDG reactions

The S28 substrate strand containing mCG, mCA, hmCG and hmCA was labelled with a 3’-fluorescein-12-ddUTP (FAM) (Enzo Life Sciences) using Terminal Transferase (NEB) according to manufacturer’s protocol and purified using a nucleotide removal purification kit (Qiagen). The substrate strand was then mixed with complement strand in a 1:1.2 ratio for a final duplex concentration of 10 ¼M and annealed as above. Substrates were then diluted to 300 nM in reaction buffer [50 mM HEPES (pH 6.5), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM α-KG, 1 mM DTT, and 2 mM sodium ascorbate]. Purified TET2-CS (600 nM) and TDG (1 ¼M, final) were added, followed by fresh ammonium iron (II) sulfate (75 ¼M), in a total reaction volume of 25 ¼L. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 4 hr. To cleave the DNA backbone at abasic sites, 2.2 ¼L of NEBuffer 4 (NEB) was added to the reaction mixture followed by 1 ¼L of APE 1 (NEB), and the samples were incubated at 37 °C for 2 hr. Following this, the samples were mixed with 2x formamide loading buffer, heat-denatured at 95 °C for 5 min and run on a prewarmed 20% denaturing PAGE gel. The gels were imaged for FAM fluorescence using a Typhoon imager (excitation at 488 nm, emission at 520 nm) and the product and remaining substrate were quantified using ImageJ.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Systematic study of all possible TET/TDG substrates in CG or non-CG contexts

Uncovers relative tolerance to CH contexts for hmC oxidation by TET

Uncovers unexpected tolerance to CH contexts for fC/caC excision by TDG

Establishes the proficiency of non-CG DNA demethylation

Provides a biochemical rationale for hmCH depletion in mCH rich genomes

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01-GM118501 to R.M.K., R01-GM072711 and R35-GM136225 to A.C.D.]; National Institutes of Health training grants supported J.C.S. [T32-GM071339; F31-CA254260] and J.E.D [T32-GM007229]; J.E.D. was also supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship [DGE-1321851]. Funding for open access charge: National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- mC

5-methylcytosine

- hmC

5-hydroxymethylcytosine

- fC

5-formylcytosine

- caC

5-carboxycytosine

- ox-mCs

oxidized mC bases

- CG

cytosine-guanine dinucleotides

- CH

non-CG dinucleotides

- mCG

methylated CG dinucleotides

- mCH

methylated CH dinucleotides

- ESCs

embryonic stem cells

- TET

ten-eleven translocation family enzymes

- α-KG

α-ketoglutarate

- TET2-CS

human TET2 crystal structure truncated variants

- NgTET1

TET homolog from N. gruberi

- (TDG)

thymine DNA glycosylase

- BER

base excision repair

- TAB-seq

TET-assisted bisulfite-sequencing

- ACE-seq

APOBEC-coupled epigenetic sequencing

- ODN

Oligodeoxynucleotide

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry

- T4 β-GT

T4 β-glucosyltransferase

- UDP-glc

Uridine diphosphate glucose

- FAM

fluorescein

- TOE

total oxidation events

- EC50

enzyme needed to consume half of the substrate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available online.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pinney S. E. (2014). Mammalian Non-CpG Methylation: Stem Cells and Beyond. Biology (Basel), 3, 739–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jang HS, Shin WJ, Lee JE & Do JT (2017). CpG and non-CpG methylation in epigenetic gene regulation and brain function. Genes, 8, 2–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinde B., Gabel HW, Gilbert CS, Griffith EC & Greenberg ME (2015). Reading the unique DNA methylation landscape of the brain: Non-CpG methylation, hydroxymethylation, and MeCP2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 112, 6800–6806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tahiliani M, Koh K, Shen Y, Pastor W, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, Iyer LM, Liu DR, Aravind L & Rao A (2009). Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science, 324, 930–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Globisch D., Munzel M, Muller M, Michalakis S, Wagner M, Koch S, Bruckl T, Biel & Carell (2010). Tissue distribution of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and search for active demethylation intermediates. PLoS One, 5, e15367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bachman M., Uribe-Lewis S, Yang X, Williams M, Murrell A & Balasubramanian (2014). 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine is a predominantly stable DNA modification. Nat. Chem, 6, 1049–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kriaucionis S., Heintz N (2009). The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain. Science, 324, 929–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He YF, Li BZ, Li Z, Liu P, Wang Y, Tang Q, Ding J, Jia Y, Chen Z, Li L, Sun Y, Li X, Dai Q, Song CX, Zhang K, He C & Xu GL (2011). Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science, 333, 1303–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito S., Shen L, Dai Q, Wu SC, Collins LB, Swenberg JA, He C & Zhang Y (2011). Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science, 333, 1300–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfaffeneder T., Hackner B, Truss M, Munzel M, Muller M, Deiml CA, Hagemeier C & Carell T (2011). The Discovery of 5-Formylcytosine in Embryonic Stem Cell DNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl, 50, 7008–7012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seiler CL, Fernandez J, Koerperich Z, Andersen MP, Kotandeniya D, Nguyen ME, Sham YY & Tretyakova NY (2018). Maintenance DNA Methyltransferase Activity in the Presence of Oxidized Forms of 5-Methylcytosine: Structural Basis for Ten Eleven Translocation-Mediated DNA Demethylation. Biochemistry, 57, 6061–6069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maiti A., Drohat AC (2011). Thymine DNA Glycosylase Can Rapidly Excise 5-Formylcytosine and 5-Carboxylcytosine: Potential Implications for Active Demethylation of CpG Sites. J. Biol. Chem, 286, 35334–35338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohli RM, Zhang Y (2013). TET enzymes, TDG and the dynamics of DNA demethylation. Nature, 502, 472–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li R, Liang J, Ni S, Zhou T, Qing X, Li H, He W, Chen J, Li F, Zhuang Q, Qin B, Xu J, Li W, Yang J, Gan Y, Qin D, Feng S, Song H, Yang D, Zhang B, Zeng L, Lai L, Esteban MA & Pei D (2010). A mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition initiates and is required for the nuclear reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts. Cell. Stem Cell, 7, 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mellen M., Ayata P & Heintz N (2017). 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine Accumulation in Postmitotic Neurons Results in Functional Demethylation of Expressed Genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 114, E7812–E7821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu M., Hon GC, Szulwach KE, Song CX, Jin P, Ren B & He C (2012). Tet-assisted bisulfite sequencing of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nat. Protoc, 7, 2159–2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schutsky EK, DeNizio JE, Hu P, Liu MY, Nabel CS, Fabyanic EB, Hwang Y, Bushman FD, Wu H & Kohli RM (2018). Nondestructive, base-resolution sequencing of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine using a DNA deaminase. Nat. Biotech, 36, 1083–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu J., Hu L, Cheng J, Fang D, Wang C, Yu K, Jiang H, Cui Q, Xu Y & Luo C (2016). A computational investigation on the substrate preference of ten-eleven-translocation 2 (TET2). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 18, 4728–4738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu L., Li Z, Cheng J, Rao Q, Gong W, Liu M, Shi YG, Zhu J, Wang P & Xu Y (2013). Crystal structure of TET2-DNA complex: insight into TET-mediated 5mC oxidation. Cell, 155, 1545–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kizaki S., Chandran A & Sugiyama H (2016). Identification of Sequence Specificity of 5-Methylcytosine Oxidation by Tet1 Protein with High-Throughput Sequencing. ChemBioChem, 17, 403–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pais JE, Dai N, Tamanaha E, Vaisvila R, Fomenkov AI, Bitinaite J, Sun Z, Guan S, Correa IR Jr Noren CJ, Cheng X, Roberts RJ, Zheng Y & Saleh L (2015). Biochemical characterization of a Naegleria TET-like oxygenase and its application in single molecule sequencing of 5-methylcytosine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 112, 4316–4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan MT Bennett MT & Drohat AC (2007). Excision of 5-halogenated uracils by human thymine DNA glycosylase. Robust activity for DNA contexts other than CpG. J. Biol. Chem, 282, 27578–27586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dow BJ, Malik SS & Drohat AC (2019). Defining the Role of Nucleotide Flipping in Enzyme Specificity using 19F NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc,jas.9b00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coey CT, Malik SS, Pidugu LS, Varney KM, Pozharski E & Drohat AC (2016). Structural basis of damage recognition by thymine DNA glycosylase: Key roles for N-terminal residues. Nucleic Acids Res, 44, 10248–10258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pidugu LS, Dai Q, Malik SS, Pozharski E & Drohat AC (2019). Excision of 5-Carboxylcytosine by Thymine DNA Glycosylase. J. Am. Chem. Soc, 141, 18851–18861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pidugu LS., Flowers JW., Coey CT., Pozharski E., Greenberg MM & Drohat AC (2016). Structural Basis for Excision of 5-Formylcytosine by Thymine DNA Glycosylase. Biochemistry, 55, 6205–6208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashimoto H., Hong S., Bhagwat AS., Zhang X. & Cheng X. (2012). Excision of 5-hydroxymethyluracil and 5-carboxylcytosine by the thymine DNA glycosylase domain: its structural basis and implications for active DNA demethylation. Nucleic Acids Res, 40, 10203–10214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L., Lu X., Lu J., Liang H., Dai Q., Xu GL., C Luo., Jiang H. & He C. (2012). Thymine DNA glycosylase specifically recognizes 5-carboxylcytosine-modified DNA. Nat. Chem. Biol, 8, 328–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeNizio J., Liu MY., Leddin EM., Cisneros GA. & Kohli RM. (2019). Selectivity and Promiscuity in TET-Mediated Oxidation of 5-Methylcytosine in DNA and RNA. Biochemistry, 58, 411–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu MY., Torabifard H., Crawford DJ., DeNizio JE., Cao XJ., Garcia BA., Cisneros GA. & Kohli RM. (2017). Mutations along a TET2 active site scaffold stall oxidation at 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nat. Chem. Biol, 13, 181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crawford DJ., Liu MY., Nabel CS., Cao XJ., Garcia BA. & Kohli RM. (2016). Tet2 Catalyzes Stepwise 5-Methylcytosine Oxidation by an Iterative and de novo Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc, 138, 730–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu MY., DeNizio JE. & Kohli RM. (2016). Quantification of Oxidized 5-Methylcytosine Bases and TET Enzyme Activity. Methods Enzymol, 573, 365–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weber AR., Krawczyk C., Robertson AB., Kusnierczyk A., Vagbo CB., Schuermann D., Klungland A. & Schar P. (2016). Biochemical reconstitution of TET1-TDG-BER-dependent active DNA demethylation reveals a highly coordinated mechanism. Nat. Commun, 7, 10806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu L., Lu J., Cheng J., Rao Q., Li Z., Hou H., Lou Z., Zhang L., Li W., Gong W., Liu M., Sun C., Yin X., Li J., Tan X., Wang P., Wang Y., Fang D., Cui Q., Yang P., He C., Jiang H., Luo C. & Xu Y. (2015). Structural insight into substrate preference for TET-mediated oxidation. Nature, 527, 118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torabifard H., Cisneros GA. (2018). Insight into wild-type and T1372E TET2-mediated 5hmC oxidation using ab initio QM/MM calculations. Chem. Sci ., 9, 8433–8445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamanaha E., Guan S., Marks K. & Saleh L. (2016). Distributive Processing by the Iron(II)/α-Ketoglutarate-Dependent Catalytic Domains of the TET Enzymes Is Consistent with Epigenetic Roles for Oxidized 5-Methylcytosine Bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc, 138, 9345–9348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgan MT, Maiti A, Fitzgerald ME & Drohat AC (2011). Stoichiometry and affinity for thymine DNA glycosylase binding to specific and nonspecific DNA. Nucleic Acids Res, 39, 2319–2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coey CT., Drohat AC. (2018). Defining the impact of sumoylation on substrate binding and catalysis by thymine DNA glycosylase. Nucleic Acids Res, 46, 5159–5170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weng YL., An R., Cassin J., Joseph J., Mi R., Wang C., Zhong C., Jin SG., Pfeifer GP., Bellacosa A., Dong X., Hoke A., He Z., Song H. & Ming GL. (2017). An Intrinsic Epigenetic Barrier for Functional Axon Regeneration. Neuron, 94, 337–346.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun Z., Dai N., Borgaro JG., Quimby A., Sun D., Correa IR Jr, Zheng Y., Zhu Z. & Guan S. (2015). A sensitive approach to map genome-wide 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and 5-formylcytosine at single-base resolution. Mol. Cell, 57, 750–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu H., Wu X., Shen L. & Zhang Y. (2014). Single-base resolution analysis of active DNA demethylation using methylase-assisted bisulfite sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol, 32, 1231–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spruijt CG., Gnerlich F., Smits AH., Pfaffeneder T., Jansen PW., Bauer C., Munzel M., Wagner M., Muller M., Khan F., Eberl HC., Mensinga A., Brinkman AB., Lephikov K., Muller U., Walter J., Boelens R., van Ingen H., Leonhardt H., Carell T. & Vermeulen M. (2013). Dynamic Readers for 5-(Hydroxy)Methylcytosine and Its Oxidized Derivatives. Cell, 152, 1146–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ko M., An J., Bandukwala HS., Chavez L., Aijo T., Pastor WA., Segal MF., Li H., Koh KP., Lahdesmaki H., Hogan PG., Aravind L. & Rao A. (2013). Modulation of TET2 expression and 5-methylcytosine oxidation by the CXXC domain protein IDAX. Nature, 497, 122–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ghanty U., DeNizio JE., Liu MY. & Kohli RM. (2018). Exploiting Substrate Promiscuity to Develop Activity-Based Probes for TET Family Enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc, 140, 17329–17332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maiti A., Morgan MT. & Drohat AC. (2009). Role of two strictly conserved residues in nucleotide flipping and N-glycosylic bond cleavage by human thymine DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem, 284, 36680–36688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghanty U., Wang T. & Kohli RM. (2020). Nucleobase Modifiers Identify TET Enzymes as Bifunctional DNA Dioxygenases Capable of Direct N-Demethylation. Angewandte Chemie (International Ed.), 59, 11312–11315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.