Abstract

Attachment theory suggests that insecurely attached individuals will have more difficulty seeking and receiving support from others. Developmentally, such struggles to garner social support early in adolescence may reinforce insecure adolescents’ negative expectations of others, amplifying such struggles over time and contributing to relationship difficulties into adulthood. Using a diverse community sample of 184 adolescents followed from age 13 to 27, along with friends and romantic partners, this study found that more insecure states of mind regarding attachment at age 14 predicted relative decreases in teens’ abilities to seek and receive support from close friends from ages 14–18. In addition, greater attachment insecurity predicted greater observed negative interactions with romantic partners and relative increases in hostile attitudes from age 14 to age 27. The effect of attachment insecurity at age 14 on observed negativity in romantic relationships at age 27 was mediated by difficulty seeking/receiving support in friendships during adolescence. Findings held after accounting for a number of potential confounds. We interpret these findings as suggesting the existence of a type of self-fulfilling prophecy as insecure adolescents confirm their negative expectations of others through ongoing struggles to obtain support.

Keywords: attachment, social support, friendships, hostility, romantic relationships

Why are some adolescents poor at asking for and receiving social support from friends, and what are the long-term implications of such difficulties? Attachment theory suggests that insecurely attached individuals are likely to struggle with both asking for and getting social support, in part due to more negative views of themselves and more negative expectations of others in close relationships (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2009; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2013). Lack of needed social support, in turn, has far-reaching implications for relationship functioning, health, and wellbeing across the life span (see, e.g., Chu, Saucier, & Hafner, 2010; Heaney & Israel, 2002).

Bowlby (1969) originally developed attachment theory to explain close relationships between caregivers and infants, yet central attachment dynamics of seeking and receiving support, affection, and security from trusted others continue into adolescence and adulthood (Ainsworth, 1969). In these later stages of development, individual differences in individuals’ state of mind with regard to attachment can be captured verbally in the Adult Attachment Interview (George, Kaplan, & Main, 1996). Insecure states of mind regarding attachment in adolescence involve dismissing and/or preoccupied strategies for processing affect and memories surrounding attachment experiences (Allen, 2008; Allen, Moore, Kuperminc, & Bell, 1998; Bowlby, 1969; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). Theoretically, these insecure strategies may impair effective social support by (a) undermining individuals’ ability to regulate negative emotion (e.g., becoming angry or overwhelmed by feelings of vulnerability), (b) biasing cognition toward expectations of less support or negative interpretation of supportive overtures (e.g., construing others’ help as ungenuine or likely to be withdrawn), and (c) driving behavior that sabotages supportive relationships (e.g., responding hostilely to others’ emotional needs; Kobak & Sceery, 1988; Main et al., 1985).

Empirically, insecure attachment in young adulthood is associated with less help-seeking behavior in general, with dismissing individuals considering others to be unreliable and preoccupied individuals considering themselves to be unworthy (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991). Insecurely attached individuals are more likely to behave in a defensive manner and to show more negative and less positive affect during interactions (Creasey, 2002; Roisman, Tsai, & Chiang, 2004; Weimer, Kerns, & Oldenburg, 2004). Insecure adolescents are likely to struggle in forming and maintaining close relationships in general, and in particular, are likely to struggle with expecting relationships to be sources of support (Grabill & Kerns, 2000; Zimmermann, 2004). This may be especially true for dismissing adolescents: One study found that nearly a third of adolescents classified as dismissing nominated themselves as their own primary attachment figure (Freeman & Brown, 2001). Within adolescence and early adulthood, insecure attachment has been associated with lower quality friendships, as well as more loneliness and lower self-perceived social support (Kobak & Sceery, 1988; Priel & Shamai, 1995; Zimmermann, 2004). Other research finds that self-reported insecure attachment styles are associated with observed difficulties asking for and receiving support from romantic partners (Collins & Feeney, 2000; Simpson, Rholes, & Nelligan, 1992; Simpson, Rholes, Oriña, & Grich, 2002). In addition, experimental work found that, for college students, self-reported attachment insecurity was associated with less perceived support from romantic partners in an ambiguous situation and that lower attachment security predicted less observed support from partners (Collins & Feeney, 2004). Importantly, one study using the Adult Attachment Interview and observational methods found that secure attachment in adolescence predicted greater supportive behaviors between partners in late adolescent romantic relationships (Tan, Hessel, Loeb, Schad, Allen, & Chango, 2016). The current study seeks to expand these findings to support seeking and receipt in friendships across adolescence.

Over the course of adolescence, friends increasingly begin to take on a variety of attachment functions (Paterson, Field, & Pryor, 1994) and become a primary source of support for many, even supplanting parents for less urgent needs (Allen, 2008; Hazan & Zeifman, 1994; Rosenthal & Kobak, 2010). Importantly, friendships vary in the extent to which they constitute enduring affectional bonds (e.g., some adolescent friendships are less stable and fade with time) and may serve different functions for the adolescent (Ainsworth, 1989). For example, while most adolescent friendships are characterized by proximity seeking (affiliation/ spending time together) and safe haven functions (seeking support, aid, or comfort in daily, non-emergency contexts), fewer involve other core elements of attachment bonds, including separation distress, enduring commitment, and secure base functions (Furman, 2001; Rosenthal & Kobak, 2010). Thus, parents typically continue to serve as primary attachment figures in early adolescence, and romantic partners in early adulthood, while affiliative bonds with friends provide an intermediate context for practicing some aspects of attachment and caregiving behavior, such as support-seeking and provision (Rosenthal & Kobak, 2010). This is one reason why adolescents’ friendship experiences may be viewed as key developmental “bridges” linking earlier attachments to caregivers with later social functioning, including with romantic partners (e.g., Ainsworth, 1989; Allen & Tan, 2016; Furman, 1999).

We suggest that one way that insecure attachment may shape similar patterns of support-seeking with both peers and partners is through negative expectations that elicit negative behavior from social partners. Previous cross-sectional work suggests that insecure attachment may discourage adolescents from seeking support from friends, as insecure adolescents continue to expect (and likely receive) unhelpful responses from others (Bauminger, Finzi-Dottan, Chason, & Har-Even, 2008). Relatedly, cross-sectional research in adults showed that individuals who self-reported more attachment insecurity were found to both expect and elicit more hostility from romantic partners (Overall, Fletcher, Simpson, & Fillo, 2015). This can be considered a type of self-fulfilling prophecy (Loeb, Tan, Hessel, & Allen, 2018) wherein insecurely attached adolescents go into friendships expecting the worst and either fail to call for support or select partners who do not provide such support. If the act of support-seeking does not provide the reinforcement of support-provision, the behavior is likely to decrease over time (though the adolescent may still need or desire support). In this case, we would expect the end result to be frustration, mistrust, and hostility as adolescents continually find relationships unhelpful. To test this developmental process hypothesis empirically, the present study builds on previous cross-sectional work to examine attachment as a predictor of support-seeking and receipt. We examined support-seeking and receipt as it unfolds over a four-year time period from mid-to late adolescence, when support from peers typically becomes more central (Allen & Tan, 2016; Hazan & Zeifman, 1994).

Insecure attachment is also associated with negativity and hostility in primarily cross-sectional research. Late adolescents who were more dismissing were rated as more hostile by peers (Kobak & Sceery, 1988), and adolescents who self-reported more attachment insecurity rated themselves as more hostile and angry (Muris, Meesters, Morren, & Moorman, 2004). Insecure states of mind have been related to externalizing and borderline personality symptoms (Dozier, Stovall-McClough, & Albus, 2008; Rosenstein & Horowitz, 1996). Importantly, insecure attachment on the AAI was found to be predictive of higher levels of romantic aggression within adolescence, though this study was unable to control for baseline aggression (Miga, Hare, Allen, & Manning, 2010). Given that romantic partners tend to take on attachment functions for many by adulthood (Hazan & Shaver, 1987), the current study sought to expand these findings to potential links between insecure attachment in early adolescence to observed romantic relationship negativity in adulthood. Such findings would support the idea of a self-fulfilling prophecy across development: Adolescents who expect the worst from others may, in fact, develop patterns of behavior and partner selection that contribute to observably problematic romantic relationships in adulthood. In addition, we wanted to examine general hostile attitudes to understand adolescents’ perceptions. Finding predictions from insecure attachment in adolescence to increasing hostile attitudes in adulthood would suggest that adolescent attachment is not only associated with hostility, but may also be involved in setting in motion a type of feedback loop (negative expectations to negative reactions from others, etc.) that contributes to even worse difficulties over time.

There is evidence from both developmental and clinical research that problems seeking and receiving social support are associated with negativity and hostility towards others over time. Insecurely attached individuals who struggle to ask for and receive support are likely not getting their needs met in relationships. Prior research has found that those who perceive that their needs are not being met are more likely to express hostility and escalate conflicts (Greenberg, Ford, Alden, & Johnson, 1993; Kobak & Sceery, 1988; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2012). These difficult relationship experiences may then contribute to increasing negativity and hostility over time. Yet little to no research has examined long-term links between insecure states of mind, social support in adolescence and long-term negativity and hostility. In addition, most extant research has relied on self-reports of social support and/or hostility. Moving beyond self-report of social support and negativity is particularly important, given that individuals with insecure states of mind are often poor self-reporters (Dozier & Lee, 1995; Kobak & Sceery, 1988) and demonstrate cognitive biases in social information processing (for a review see Dykas & Cassidy, 2011). The current study utilized observational measures to capture a potential maladaptive pathway from insecure attachment to decreasing levels of social support and, ultimately, to greater negativity in romantic relationships and increasingly hostile attitudes.

Using longitudinal, multimethod data obtained from a diverse community sample followed from age 13 to 29, this paper examined the hypotheses that:

Insecure attachment in early adolescence will predict increasing difficulties asking for and receiving support from friends across adolescence.

Insecure attachment in early adolescence will predict more observed negativity during conflict in adult romantic relationships and more hostile attitudes in adulthood.

Observed difficulties calling for and receiving support will mediate relations between insecure attachment and negativity and hostility in adulthood.

Method

The current sample was part of a larger longitudinal study of adolescent social development in familial and peer contexts. The original sample included 184 seventh and eighth graders (86 male and 98 female) and their parents. The sample was racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse: 107 adolescents (58%) identified as Caucasian, 53 (29%) as African American, 15 (8%) as of mixed race ⁄ ethnicity, and 9 (5%) as being from other minority groups. Adolescents’ parents reported a median family income in the $40,000–$59,999 range. Adolescents were originally recruited from the seventh and eighth grades at a public middle school drawing from suburban and urban populations in the Southeastern United States. Students were recruited via an initial mailing to all parents of students in the school, along with follow-up contact efforts at school lunches. Adolescents who indicated they were interested in the study were contacted by telephone. Of all students eligible for participation, 63% agreed to participate either as target participants or as peers providing collateral information. For the current study, participants provided data at seven time points: at age 14 (M age = 14.27, SD = 0.77), at age 15 (M age = 15.21, SD = 0.81), at age 16 (M age = 16.35, SD = 0.87), at age 17 (M age = 17.32, SD = 0.88), at age 18 (M age = 18.38, SD = 104), and at age 27 (M age = 27.39, SD = 1.41). At the age 14–18 assessments, participants (N = 171) and their close friends provided data. Close friends were defined as “people you know well, spend time with, and whom you talk to about things that happen in your life.” Friends were close in age to participants (i.e., their ages differed on average by less than a month from target adolescents’ ages) and were specified to be the same gender. Close friends reported that they had known the participants for an average of 4.27 years (SD = 3.09) at age 14, 5.07 years (SD = 3.41) at age 15, 5.72 years (SD = 3.82) at age 16, 5.92 years (SD = 3.86) at age 17, and 6.79 years (SD = 4.46) at age 18. At the age 27 assessment, participants and romantic partners of at least three months’ duration (N = 90) participated in an observational task. Participants reported dating their romantic partner for an average of 4.19 years (SD = 3.47). Participants also provided data on their own hostile attitudes.

Attrition Analyses

Attrition analyses indicated that females were significantly more likely to provide information on hostile attitudes at age 27 (χ2 = 14.94, p = .001). No other significant differences were found between those who did vs. did not participate at any of the three waves (Wave 1 = age 14, Wave 2 = ages 15–18, and Wave 3 = age 27) in terms of gender, income, or baseline levels of the outcome variables.

To best address any potential biases due to attrition and missing data in longitudinal analyses, full information maximum likelihood (FIML) methods were used, with analyses including all variables that were linked to attrition (i.e., where data were not missing completely at random). Because these procedures have been found to yield less biased estimates than approaches that use listwise deletion of cases with missing data (e.g., simple regression; Mueller & Hancock, 2010), the entire original sample of 184 for the larger study was utilized for these analyses. This analytic technique does not impute or create any new data, nor does it artificially inflate significance levels. Rather, it simply takes into account distributional characteristics of data in the full sample so as to provide the least biased estimates of parameters obtained when some data are missing (Arbuckle, 1996).

For all data collection, adolescents and their peers provided informed assent, and their parents provided informed consent before each interview session. Once participants reached age 18, they provided informed consent. Interviews took place in private offices within a university academic building. Adolescents and peers were all paid for their participation. Participants’ data were protected by a Confidentiality Certificate issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which further protects information from subpoena by federal, state, and local courts. If necessary, transportation and child-care were provided to participants.

Measures

Adolescent Attachment States of Mind (Age 14).

To assess adolescent attachment states of mind, the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) and Q-set were utilized. The structured interview (George, Kaplan, & Main, 1996) and Q-set, (Kobak, Cole, Ferenz-Gillies, Fleming, & Gamble, 1993) probes individuals’ descriptions of their childhood relationships with parents by asking for both abstract descriptions of the relationship and specific supporting memories. For example, participants were asked to list five words describing their early childhood relationships with each parent and then to describe specific episodes that reflected those words. Other questions focused on specific instances of feeling upset, separation, loss, trauma, and rejection. Finally, interviewers asked participants to provide more integrative descriptions of changes in relationships with parents and the current state of those relationships. The interview consisted of 18 questions and lasted one hour on average. The original AAI is considered the gold standard for assessing attachment in adulthood (Hesse, 2016); in the present study, slight adaptations to the adult version were made so that the questions were more natural, and easily understood by an adolescent population (Ward & Carlson, 1995). Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim for coding.

The AAI Q-set (Kobak et al., 1993) was designed to closely parallel the Adult Attachment Interview Classification System (Main, Goldwyn, & Hesse, 1998), but also to yield continuous measures of qualities of attachment organization. Nevertheless, the data produced by the system can be reduced via an algorithm to classifications that have been found to largely agree with three-category ratings from the AAI Classification System, both in the field generally and when applied to a subsample of this particular population using coders from this lab (Allen, Hauser, & Borman-Spurrell, 1996; Allen, Moore, Kuperminc, & Bell, 1998; Kobak et al., 1993). Each rater reads a transcript and provides a Q-sort description by assigning 100 items into nine categories ranging from most to least characteristic of the interview, using a forced distribution. This method aligns with current recommendations, based on taxometric research, to examine attachment security on the AAI continuously (e.g., Roisman, Fraley, & Belsky, 2007). All interviews were blindly rated by at least two reliable raters with extensive training in both the Q-sort and the main AAI Classification System.

These Q-sorts were then compared with three dimensional prototype sorts: secure versus anxious interview strategies, reflecting the overall degree of coherence of discourse, the integration of episodic and semantic attachment memories, and a clear objective valuing of attachment; preoccupied strategies, reflecting either rambling, extensive, but ultimately unfocused discourse about attachment experiences or angry preoccupation with attachment figures; dismissing strategies, reflecting inability or unwillingness to recount attachment experiences, idealization of attachment figures that is discordant with reported experiences, and lack of evidence of valuing attachment. The current investigation focused on the overall security dimension. The correlation of the 100 items of an adolescent’s Q-sort with each dimension (range = −1.00 to 1.00) were then taken as the subject’s scale score for that dimension. The Spearman–Brown interrater reliability for the overall security scale score was .82.

Observed Difficulties Seeking and Receiving Support (Ages 14–18).

The quality of adolescents’ interactions with their closest friend was observed during a Supportive Behavior Task at five time points. Adolescents participated in a 6-minute interaction task with their closest same-gender friend, during which they talked to him or her about a “problem they were having that they could use some advice or support about.” Typical topics included dating, problems with peers or siblings, raising money, or deciding about joining sports teams. These interactions were then coded using the Supportive Behavior Coding System (Allen et al., 2001), which was based on several related systems developed by Crowell and colleagues (Crowell et al.; Haynes & Fainsilber Katz, 1998; Julien et al., 1997). The degree of the adolescent’s call for support from their friend, as well as their friend’s provision of support, were coded on scales ranging from 0 to 4 (0 = characteristic not present, 4 = characteristic highly present), based on the strength and persistence of the adolescent’s requests for support and the friend’s attempts to provide suggestions and/or offer sympathy and understanding. These two subscales were highly correlated (rs = .72 at age 14 and .72 at ages 15–18) and thus were combined to yield the overall dyadic scale for support seeking/receiving (McElhaney, Antonishak, & Allen, 2008). Each interaction was reliably coded as an average of the scores obtained by two trained raters blind to other data from the study with excellent reliability (intraclass correlations ranged from r = .70 to .83 across years).

Observed Negativity with Friends (Age 14) and Romantic Partners (Age 27).

At age 14, participants and their close friends participated in a revealed differences task in which they had to come to a consensus on a hypothetical task (which hypothetical patients should be given a cure to a new, fatal disease). At age 27, participants and their romantic partners were asked to talk about their biggest area of disagreement. All interactions lasted 8 minutes and were video recorded for coding purposes. The coding system employed yields a rating for each participant’s overall negative behavior toward his/her partner in the interaction (Allen, Hauser, Bell, & McElhaney, 2000; Allen, Hauser, Eickholt, Bell, & Oconnor, 1994). Behaviors that are considered in rating negative behavior include: 1) Overpersonalizing behaviors: Treating the disagreement as being in some respect a “fault” or feature of the person disagreeing rather than a difference in ideas and reasons; 2) Pressuring behaviors: The extent to which the individual proceeds in the discussion as though his/her main objective is to get his/her own selections accepted; 3) Avoidance behaviors: The degree to which an individual steers away from disagreements or the chance to clarify disagreements; and 4) Rudeness: The use of hostile comments, interruptions, or other tactics that undermine the relationship. These indicators were used to produce the observed negativity score, with higher scores represent higher observed negativity. Participants’ and partners’ scores were averaged together to capture dyadic-level negative behaviors. Interrater reliability was calculated for observed negativity using intraclass correlation coefficients and was in what is considered “fair” to “excellent” range for this statistic (intraclass r = .54-.78).

Hostile Attitudes (Age 14 and 27).

Participants reported about their hostile and aggressive attitudes using the Aggressive Attitudes Questionnaire (Guerra, 1986; Slaby & Guerra, 1988). The 18-item scale captures the extent to which respondents endorse the necessity and acceptability of violence and aggression. Example items include “It’s OK to hit someone if you think he or she deserves it” and “Being raped must be awful” (reverse scored). Participants rated how true each item was for them on a 5-point scale from really disagree to really agree. Hostile attitudes assessed by this and similar measures are associated with reports of actual hostile behavior (Bosworth, Espelage, & Simon, 1999; Eliot & Cornell, 2009; Slaby & Guerra, 1988). Internal consistency for this measure was good (age 14 Cronbach’s α = .88; age 27 Cronbach’s α = .89).

Friend-rated Social Acceptance (Age 13).

Friend reports of the adolescent’s social acceptance were assessed using a modified version of the Adolescent Self-Perception Profile (Harter, 1985). The original items were modified to allow friend ratings of the adolescent, rather than self-ratings. Friends chose between two contrasting statements that could describe the participant. They then rated how true of the participant the selected statement was on a 2-point scale, yielding a score from 1–4 for each item. The scale consisted of four items, e.g., “Some teenagers understand how to get peers to accept them BUT other teenagers don’t understand how to get peers to accept them.” The original measure shows good convergent validity with other established measures of self-concept in adolescence (e.g., Hagborg, 1993). Internal consistency for the 4-item scale in the present study was fair (Cronbach’s α = .77).

Personality (Age 24).

At age 24 (the first year these variables were obtained), participants completed 50 items drawn from the International Personality Inventory Pool to assess key facets of personality (Goldberg et al., 2006). Ten items tapped each of five personality traits of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability/neuroticism, and imagination or intellect. For example, the emotional stability scale includes the item, “I am relaxed most of the time.” Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 = Very inaccurate and 5 = Very accurate, such that higher scores indicate greater endorsement of each personality trait. The measure is widely used in studies of adult personality (see Goldberg et al., 2006) and shows strong psychometric properties and concurrent validity with other validated personality indices (e.g., Lim & Ployhart, 2006). The extraversion, emotional stability/neuroticism, and agreeableness subscales showed fair to good internal consistencies (Cronbach’s α range = .77 to .89).

Results

Preliminary Analyses & Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of substantive variables. Gender and family income were correlated with several variables of interest; hence, these demographic factors were included as covariates in all analyses. We also examined the possible moderating effects of gender and family income on each of the relations described in the primary analyses. All moderating effects analyzed were obtained by creating interaction terms based on the product of mean-centered main effect variables. No moderating effects were found.

Table 1.

Correlations Among and Descriptive Statistics for Key Study Variables

| M (SD) | N | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Attach. Security (14) | .25 (.42) | 174 | -- | 26*** | 37*** | 03 | −28** | −22** | −41*** | 03 | 15 | −09 | 24** | 12 | 28*** |

| 2. Seek/Receive Support (14) | 1.63 (.66) | 164 | -- | 41*** | −08 | −02 | −08 | −15 | 13 | −09 | 08 | −06 | 22** | 07 | |

| 3. Seek/Receive Support(15–18) | 1.69 (.49) | 171 | -- | −04 | −28** | −26*** | −30*** | −01 | 00 | 01 | 21** | 30*** | 20** | ||

| 4. Negativity with Friend (14) | .65 (.26) | 161 | -- | 09 | −06 | −03 | 01 | 04 | 03 | 05 | 02 | −00 | |||

| 5. Negativity with Romantic Partner (27) | .85 (.79) | 87 | -- | 22 | 24* | 11 | −01 | 06 | −36** | 14 | −38*** | ||||

| 6. Hostile Attitudes (14) | 35.56 (9.79) | 162 | -- | −40*** | 05 | −04 | −02 | −36*** | −34*** | −02 | |||||

| 7. Hostile Attitudes (27) | 26.86 (8.34) | 148 | -- | 05 | −06 | 09 | −35*** | −23** | −18* | ||||||

| 8. Social Acceptance (13) | 12.87 (2.79) | 180 | -- | 06 | −11 | 10 | −05 | −00 | |||||||

| 9. Extraversion (24) | 34.09 (7.45) | 156 | -- | −31*** | 31*** | −02 | 12 | ||||||||

| 10. Neuroticism (24) | 34.10 (8.75) | 155 | -- | 14 | −26*** | −04 | |||||||||

| 11. Agreeableness (24) | 39.81 (5.52) | 155 | -- | 20** | 18* | ||||||||||

| 12. Gender (1=Male, 2=Female) | -- | 184 | -- | −12 | |||||||||||

| 13. Family Income (13) | 43,600 (22,4000) | 181 | -- |

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ . 001.

Note: Correlations multiplied by 100.

Primary Analyses

Hypothesis 1: Insecure attachment in early adolescence will predict more observed difficulties asking for and receiving support from friends across adolescence.

Regressions using FIML analyses were conducted in MPlus (Version 7.2; Muthén & Muthén, 2015). As shown in Table 2, controlling for participant gender, family income at age 13, and seeking/receiving support at age 14, insecure attachment predicted relative decreases (i.e., accounting for baseline seeking/receiving support) in seeking/receiving support through age 18 (β = −.25, p = .001). This suggests that insecure attachment in early adolescence was predictive of decreasing support in friendships through age 18, accounting for relevant covariates.

Table 2.

Predicting Support-Seeking and Receipt in Friendships (Ages 15–18) from Attachment Security (Age 14)

| Support-Seeking and Receipt (Ages 15–18) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β entry | β final | ΔR2 | Total R2 | |

| Step I. | ||||

| Gender (1=M; 2=F) | .32*** | .22** | ||

| Total Family Income (13) | .23** | .11 | ||

| Statistics for Step | .138 | .138** | ||

| Step II. | ||||

| Support-Seeking and Receipt (Age 14) | .35*** | .31*** | ||

| .117*** | .255*** | |||

| Step III. | ||||

| Attachment Security (Age 14) | .25** | .25** | ||

| .058*** | .313*** | |||

Note.

p < .001.

p < .01.

Hypothesis 2: Insecure attachment in early adolescence will predict more observed negativity during conflict in adult romantic relationships and more hostile attitudes in adulthood.

As shown in Table 3, controlling for participant gender, family income, and observed negativity in a friendship at age 14, insecure attachment at age 14 predicted higher levels of observed negativity in a romantic relationship by age 27 (β = .23, p = .02). This suggests that, accounting for demographic variables and baseline levels of negativity with a friend, more insecure attachment at age 14 was predictive of more problematic behaviors in romantic relationships during a disagreement task at age 27.

Table 3.

Predicting Observable Negativity in Romantic Relationships (Age 27) from Attachment Security (Age 14)

| Negativity in Romantic Relationships (Age 27) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β entry | β final | ΔR2 | Total R2 | |

| Step I. | ||||

| Gender (1=M; 2=F) | .097 | .11 | ||

| Total Family Income (13) | −.36*** | −.30** | ||

| Statistics for Step | .145 | .145* | ||

| Step II. | ||||

| Negativity in Friendships (Age 14) | .10 | .11 | ||

| .011 | .156* | |||

| Step III. | ||||

| Attachment Security (Age 14) | −.24** | −.24** | ||

| .056* | .212*** | |||

Note.

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

As shown in Table 4, controlling for gender, income, and hostile attitudes at age 14, insecure attachment at age 14 also predicted relative increases in hostile attitudes by age 27 (β = .33, p = .001). This suggests that insecure attachment was predictive of increasingly hostile attitudes, even accounting for demographic variables and baseline levels of hostile attitudes.

Table 4.

Predicting Hostile Attitudes (Age 27) from Attachment Security (Age 14)

| Hostile Attitudes (Age 27) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β entry |

β final |

ΔR2 | Total R2 | |

| Step I. | ||||

| Gender (1=M; 2=F) | −.26** | −.12 | ||

| Total Family Income (13) | −.21** | −.06 | ||

| Statistics for Step | .097 | .097* | ||

| Step II. | ||||

| Hostile Attitudes (Age 14) | .35*** | .30*** | ||

| .113*** | .210** | |||

| Step III. | ||||

| Attachment Security (Age 14) |

−.33** | −.33** | ||

| .099*** | .309*** | |||

Note.

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

Hypothesis 3: Observed difficulties seeking and receiving support will mediate relations between insecure attachment and negativity and hostility in adulthood.

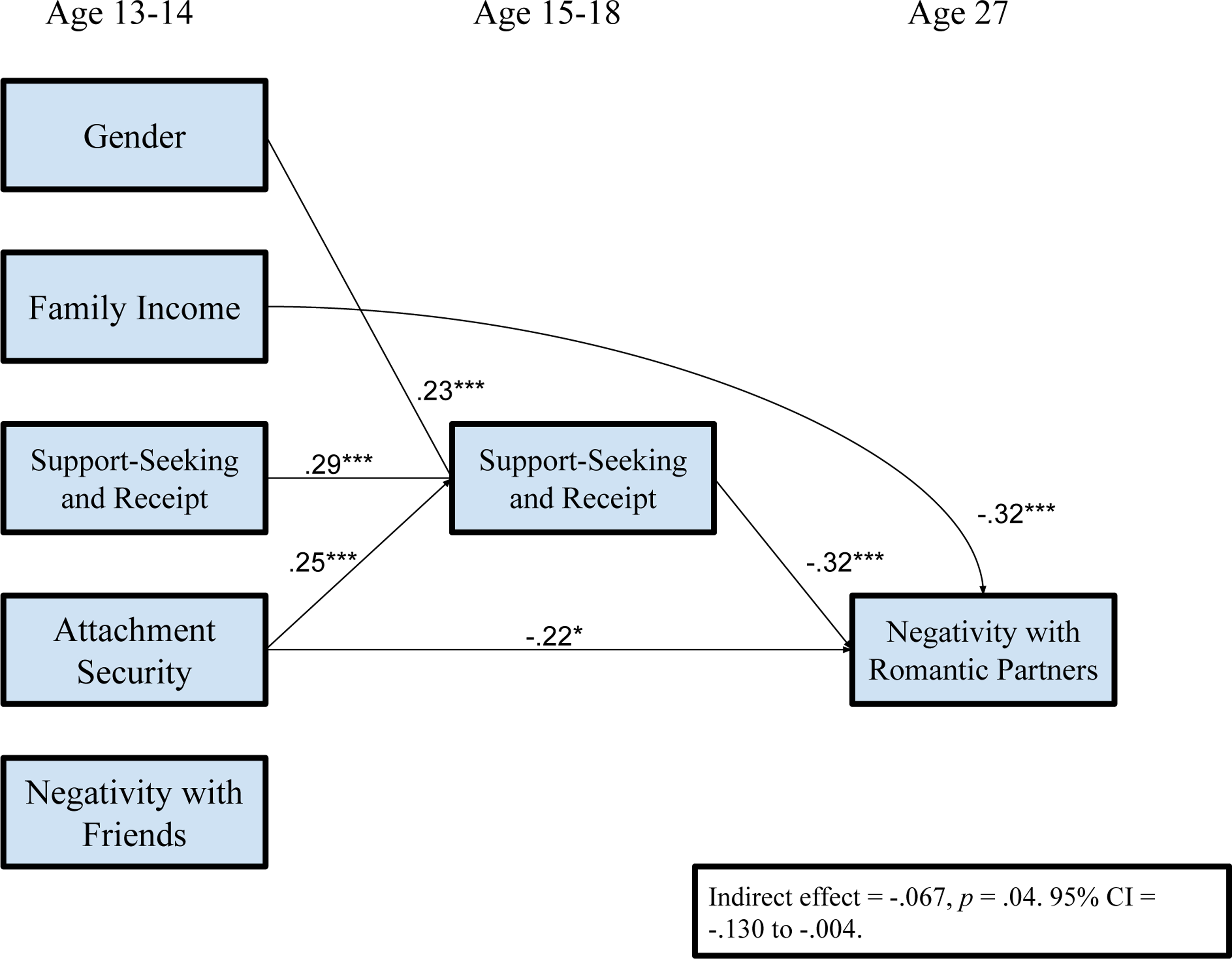

After accounting for gender, income, and observed negativity in a friendship at age 14, seeking/receiving support in friendships negatively predicted observed negativity in romantic relationships at age 27 (β = −.37, p = .001). In addition, after accounting for gender, income, and hostile attitudes at age 14, seeking/receiving support in friendships negatively predicted hostile attitudes at age 27 (β = −.17, p = .04). Using bootstrapped confidence intervals and accounting for gender, family income, and baseline levels of outcomes, potential indirect effects were examined. There was a significant indirect effect of attachment security at age 14 on observed negativity in romantic relationships at age 27 through seeking/receiving support in friendships from ages 15–18 (β = −.07, 95% CI [−.130, −.004]; see Figure 1). The effect of attachment security on observed negativity was no longer significant when seeking/receiving support was included (β = −.14, p = .22). This suggests that the effect of attachment security at age 14 on observed negativity in romantic relationships at age 27 was explained by seeking/receiving support in friendships from ages 15–18. There was no significant indirect effect from attachment security at age 14 to hostile attitudes at age 27 through seeking/receiving support in friendships from ages 15–18.

Figure 1.

Mediation model of attachment security at 14 to negativity with romantic partners at age 27, via difficulties seeking and receiving support with close friends from ages 15–18.

Post-hoc analyses

To examine the possibility that other dispositional qualities of the adolescent might explain these findings, we tested several competing explanations for the link between attachment and later outcomes, including close-friend-rated social acceptance, self-reported extraversion, neuroticism, and agreeableness. Each competing explanatory factor was considered individually in separate regression analyses (where each regression also included adolescent gender and family income). We found that, after including each of close-friend-rated social acceptance, as well as self-reported extraversion, neuroticism, and agreeableness, attachment security continued to predict seeking/receiving support from ages 15–18, observed negativity at age 27, and hostile attitudes at age 27. This pattern suggests that findings were not better explained by personality factors or friend-reported general social acceptance.

Next, although the focus of this paper was overall attachment (in)security, we also examined whether specific dimensions of insecurity—dismissing and preoccupied strategies at age 14—significantly predicted seeking/receiving support from ages 15–18, and negativity and hostility at age 27. We found that, accounting for gender, family income, and seeking/receiving support at age 14, dismissing strategies predicted relative declines in seeking/receiving support from ages 15–18, though more weakly than overall attachment insecurity (β = −.18, p = .02). Preoccupied strategies did not significantly predict declines in seeking/receiving support from ages 15–18 (β = −.10, p = .20). In terms of observed negativity, dismissing strategies predicted more observed negativity in romantic relationships at age 27 after accounting for gender, income, and observed negativity in friendships at age 14 (β = .26, p = .01). Preoccupied strategies did not significantly predict observed negativity at age 27 (β = .18, p = .10). In terms of hostile attitudes, after accounting for gender, income, and hostile attitudes at age 14, both dismissing (β = .32, p = .001) and preoccupied (β = .24, p = .001) strategies significantly predicted relative increases in hostile attitudes by age 27. In general, dismissing strategies were more strongly associated with seeking/receiving support and later negativity and hostility than preoccupied strategies, though preoccupied strategies also predicted increases in hostile attitudes.

Discussion

These multimethod, longitudinal findings point to the importance of attachment in early adolescence as a potential framework for understanding why some teens struggle to ask for and receive support. These findings build on previous work that found that attachment security in adolescence predicted supportive behaviors in late adolescent romantic relationships (Tan et al., 2016). Further, they provide some of the first long-term longitudinal evidence that individuals who continually fail to elicit adequate support may become more negative and hostile over time, perhaps as they face ongoing frustration and confirmation of their negative expectations of others. Overall, we posit that this is a type of self-fulfilling prophecy: Insecurely attached individuals tend to have negative schemas (or “attachment scripts”; Waters & Waters, 2006) about the unhelpfulness of others (Grabill & Kerns, 2000; Zimmermann, 2004). These negative scripts may then lead them to behave in counterproductive (e.g., hostile) ways that result in less support-provision, which confirms their expectations, and so on (for similar ideas see Loeb et al., 2018; Steinberg, Davila, & Fincham, 2006).

Specifically, we found that insecurely attached adolescents (assessed via state of mind on the gold standard AAI) became less likely to ask for and receive support in close friendships from ages 14 to 18; when examining specific dimensions of insecure attachment, dismissing but not preoccupied states of mind predicted decreasing support-seeking/receipt. This could be a significant problem during this developmental period, when adolescents should be learning to increasingly rely on peers for much of their social support (Hazan & Ziefman, 1994; Rosenthal & Kobak, 2010). These results suggest that insecurely attached adolescents may become closed off or overly self-reliant during this critical time. They may also be selecting friends who are unwilling or unable to provide support, which would further reinforce their schema that friends are not good sources of support. Overall, insecurely attached adolescents are likely missing out on developing a key skill for healthy relationships: the ability to appropriately draw on others for support and guidance (Allen & Tan, 2016).

The consequences of struggling to garner needed social support are not confined to adolescence; crucially, effects ripple into adult relationships. Ultimately, we found that insecurely attached adolescents were more likely to develop negative relationships and attitudes by adulthood. There is increasing evidence of a developmental cascade effect from problems in adolescence into adulthood (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010), and the current study supports this idea. We suggest that years of expecting and receiving little support from important relationships could in turn lead to frustration and anger towards others. In fact, this is consistent with previous research that finds a robust link between attachment insecurity and hostility (e.g., Kobak, Zajac, & Smith, 2009; Muris et al., 2004; see also Mikulincer & Shaver, 2011; van IJzendoorn, 1997). Negativity and hostility may thus become natural, if secondary, consequences of attachment insecurity: Adolescents’ negative expectations of others are likely to be reaffirmed across years, as individuals continue to face and recreate unhelpful relationship dynamics (through evocation, partner selection, or both) and to experience concomitant feelings of anger as their emotional needs are repeatedly frustrated (Greenberg et al., 1993; Kobak & Sceery, 1988).

More broadly, results speak to Bowlby’s (1969) foundational claim that attachment experiences with parents have long-term implications for social relationships across the lifespan, in part via internal working models of self and other that perpetuate predictable patterns of behavior with close others. That insecure attachment at age 14 predicted observed negativity with romantic partners at age 27 suggests moderate continuity in individuals’ broader pattern of poor relationship quality from early adolescence to adulthood. Moreover, the findings point to peer support as a central mechanism maintaining such continuity; in particular, peer relationships appear to be a context in which security-seeking dynamics may be practiced, reinforced, and amplified over time, with downstream consequences for romantic relationships. One potential implication of the findings is that peer relationships may be a fruitful (and developmentally salient) target for interventions programs to shift negative cycles of social disconnection toward more mutually supportive, secure interactions that have the potential to inform future adult relationships.

There are several limitations of the present work that are important to note. Our data, although prospective across many years, is not experimental and is not sufficient to support causal inferences. We also did not have access to data prior to age 13, so we can only speculate as to why some of our participants developed more insecure attachment states of mind and subsequent difficulty in relationships. While we accounted for personality characteristics as potential confounds, we only began measuring these at age 24, well after our initial data collection. However, research finds that personality is moderately stable from adolescence to adulthood (e.g., Stein, Newcomb, & Bentler, 1986). There is also the possibility that other third variables, such as parental mental health, may explain both attachment insecurity and later relationship characteristics. Different tasks were used in examining negativity with friends in adolescence (which used a hypothetical task) and negativity with romantic partners in adulthood (which used the biggest area of disagreement). Though we consider the different tasks to be necessary given the ages assessed, measures of negativity in adolescence may not be analogous to negativity in adulthood. In addition, we relied on self-reports of hostile attitudes at ages 14 and 27, which introduces potential self-report biases.

In sum, this study is the first to our knowledge to examine associations between attachment states of mind in adolescence and observable qualities of relationships nearly a decade and a half later. Importantly, we also accounted for potential confounds, such as participant gender, family income, baseline levels of outcomes, personality factors, and general social acceptance. We believe that these results add to our understanding of how adolescents with insecure attachments develop across time and relationships. We also suggest that programs that target social and emotional learning may be particularly important for adolescents who do not feel secure in their parental relationships and that particular emphasis might be placed on learning when and how to ask for support from others. Additionally, programs and policies to encourage adolescent help-seeking for physical health (Barker, 2007) could be broadened to include psychological health.

References

- Ainsworth MDS (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44, 709–716. 10.1037/0003-066X.44.4.709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, & Wall S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Allen J, Hall F, Insabella G, Land D, Marsh P, & Porter M. (2001). The supportive behavior task coding system. Unpublished manuscript University of Virginia. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP (2008). The attachment system in adolescence. In Cassidy J & Shaver PR (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (p. 419–435). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST, & Borman-Spurrell E. (1996). Attachment theory as a framework for understanding sequelae of severe adolescent psychopathology: An 11-year follow-up study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(2), 254–263. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.64.2.254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST, Bell KL, & McElhaney KB (2000). The autonomy and relatedness coding system. University of Virginia, Charlottesville. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST, Eickholt C, Bell KL, & Oconnor TG (1994). Autonomy and Relatedness in Family Interactions as Predictors of Expressions of Negative Adolescent Affect. Journal of Research on adolescence, 4(4), 535–552. doi: 10.1207/s15327795jra0404_6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Moore C, Kuperminc G and Bell K. (1998), Attachment and Adolescent Psychosocial Functioning. Child Development, 69: 1406–1419. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06220.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, & Tan JS (2016). The multiple facets of attachment in adolescence. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications, 399–415. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL (1996). Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. Advanced Structural Equation Modeling: Issues and Techniques, 243, 277. [Google Scholar]

- Barker Gary. (2007). Adolescents, social support and help-seeking behaviour : an international literature review and programme consultation with recommendations for action / Gary Barker. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43778 [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, & Horowitz LM (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 226. 10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauminger N, Finzi-Dottan R, Chason S, & Har-Even D. (2008). Intimacy in adolescent friendship: The roles of attachment, coherence, and self-disclosure. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25(3), 409–428. doi: 10.1177/0265407508090866 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth K, Espelage DL, Simon TR (1999). Factors associated with bullying behavior in middle school students. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 19, 341–362. 10.1177/0272431699019003003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1969). Attachment and loss, Volume I: Attachment. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Chu PS, Saucier DA, & Hafner E. (2010). Meta-analysis of the relationships between social support and well-being in children and adolescents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29(6), 624–645. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.6.624 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, & Feeney BC (2000). A safe haven: an attachment theory perspective on support seeking and caregiving in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(6), 1053–1073. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.6.1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, & Feeney BC (2004). Working Models of Attachment Shape Perceptions of Social Support: Evidence From Experimental and Observational Studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 363–383. 10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creasey G. (2002). Associations between working models of attachment and conflict management behavior in romantic couples. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49(3), 365–375. doi: 10.1037//0022-0167.49.3.365 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell J, Pan H, Goa Y, Treboux D, O’Connor E, & Waters E The secure base scoring system for adults. Version 2.0. State University of New York; Stonybrook: 1998. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, & Lee SW (1995). Discrepancies between self-and other-report of psychiatric symptomatology: Effects of dismissing attachment strategies. Development and Psychopathology, 7(1), 217–226. 10.1017/S095457940000643X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Stovall-McClough KC, & Albus KE (2008). Attachment and psychopathology in adulthood. In Cassidy J & Shaver PR (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (p. 718–744). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dykas MJ, & Cassidy J. (2011). Attachment and the processing of social information across the life span: theory and evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 137(1), 19. 10.1037/a0021367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliot M, Cornell DG (2009). Bullying in middle school as a function of insecure attachment and aggressive attitudes. School Psychology International, 30, 201–214. 10.1177/0143034309104148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman H, & Brown BB (2001). Primary attachment to parents and peers during adolescence: differences by attachment style. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30(6), 653–674. doi: 10.1023/A:1012200511045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W. (1999). Friends and lovers: The role of peer relationships in adolescent romantic relationships. In Collins CW & Laursen B (Eds), Relationships as developmental contexts. The Minnesota symposia on child psychology, Vol 30 (pp. 133–154). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W. (2001). Working Models of Friendships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 18(5), 583–602. 10.1177/0265407501185002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George C, Kaplan N, & Main M. (1996). Adult Attachment Interview (third edition). Unpublished manuscript, Department of Psychology, University of California, Berkeley. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR, Johnson JA, Eber HW, Hogan R, Ashton MC, Cloninger CR, & Gough HG (2006). The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(1), 84–96. 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grabill CM, & Kerns KA (2000). Attachment style and intimacy in friendship. Personal Relationships, 7(4), 363–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2000.tb00022.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg LS, Ford CL, Alden LS, & Johnson SM (1993). In-session change in emotionally focused therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(1), 78. 10.1037/0022-006X.61.1.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra N. (1986). The assessment and training of interpersonal problem-solving skills in aggressive and delinquent youth (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Harvard University, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Hagborg WJ (1993). The Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale and Harter’s Self-Perception profile for adolescents: A concurrent validity study. Psychology in the Schools, 30(2), 132–136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S 1985. The Self-Perception Profile for Children: revision of the Perceived Competence Scale for Children Manual. Denver, CO: University of Denver. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes C, & Fainsilber Katz K. (1998). Adolescent social skills technique coding manual. Unpublished manuscript, University of Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, & Shaver P. (1987). Romantic Love Conceptualized as an Attachment Process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 511–524. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, & Zeifman (1994). Sex and the psychological tether. In Bartholomew K & Perlman D (Eds.), Attachment processes in adulthood: Advances in personal relationships (Vol. 5, pp. 151–177). London: Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Heaney C & Israel B. (2001). Social networks and social support. In Glanz K, Rimer B, & Lewis F, (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 185–209). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse E. (2016). The adult attachment interview: Protocol, method of analysis, and empirical studies: 1985–2015. In Cassidy J & Shaver PR (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (3rd ed., pp. 553–597). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Julien D, Markman H, Lindahl K, Johnson H, Van Widenfelt B, & Herskovitz J. (1997). The interactional dimensions coding system. Unpublished manuscript, University of Denver. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Cole HE, Ferenz-Gillies R, Fleming WS, & Gamble W. (1993). Attachment and emotion regulation during mother-teen problem solving: A control theory analysis. Child Development, 64(1), 231–245. 10.2307/1131448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, & Sceery A. (1988). Attachment in late adolescence: Working models, affect regulation, and representations of self and others. Child Development, 59(1), 135–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03201.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak R, Zajac K, & Smith C. (2009). Adolescent attachment and trajectories of hostile–impulsive behavior: Implications for the development of personality disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 21(3), 839–851. 10.1017/S0954579409000455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim BC, & Ployhart RE (2006). Assessing the convergent and discriminant validity of Goldberg’s International Personality Item Pool: A multitrait-multimethod examination. Organizational Research Methods, 9, 29–54. 10.1177/1094428105283193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb EL, Tan JS, Hessel ET, & Allen JP. (2018). Getting what you expect: Negative social expectations in early adolescence predict hostile romantic partnerships and friendships into adulthood. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 38(4), 475–496. doi: 10.1177/0272431616675971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Goldwyn R, & Hesse E. (1998). Adult attachment scoring and classification system. Unpublished manuscript, University of California at Berkeley, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, & Cassidy J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1–2), 66–104. Doi: 10.2307/3333827 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, & Cicchetti D. (2010). Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology, 22(3), 491–495. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElhaney KB, Antonishak J, & Allen JP (2008). “They like me, they like me not”: Popularity and adolescents’ perceptions of acceptance predicting social functioning over time. Child Development, 79(3), 720–731. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01153.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miga EM, Hare A, Allen JP, & Manning N. (2010). The relation of insecure attachment states of mind and romantic attachment styles to adolescent aggression in romantic relationships. Attachment & Human Development, 12(5), 463–481. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2010.501971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, & Shaver PR (2009). An attachment and behavioral systems perspective on social support. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26(1), 7–19. 10.1177/0265407509105518 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, & Shaver PR (2011). Attachment, anger, and aggression. In Shaver PR & Mikulincer M (Eds.), Human aggression and violence: Causes, manifestations, and consequences (pp. 241–257). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, & Shaver PR (2012). Adult attachment orientations and relationship processes. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 4(4), 259–274. 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2012.00142.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, & Shaver PR (2013). The role of attachment security in adolescent and adult close relationships. In Simpson JA & Campbell L (Eds.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of close relationships (p. 66–89). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller RO, & Hancock GR (2010). Structural equation modeling. In Hancock GR & Mueller RO (Eds.), The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences (pp. 371–383). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Meesters C, Morren M, & Moorman L. (2004). Anger and hostility in adolescents: Relationships with self-reported attachment style and perceived parental rearing styles. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(3), 257–264. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00616-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén L. (2015). Mplus Version 7.2 [Computer software] . Los Angeles, CA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Overall NC, Fletcher GJ, Simpson JA, & Fillo J. (2015). Attachment insecurity, biased perceptions of romantic partners’ negative emotions, and hostile relationship behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(5), 730. doi: 10.1037/a0038987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson JE, Field J, & Pryor J. (1994). Adolescents’ perceptions of their attachment relationships with their mothers, fathers, and friends. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 23(5), 579–600. doi: 10.1007/Bf01537737 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Priel B, & Shamai D. (1995). Attachment style and perceived social support: Effects on affect regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 19(2), 235–241. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(95)91936-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Fraley RC, & Belsky J. (2007). A taxometric study of the Adult Attachment Interview. Developmental Psychology, 43(3), 675–686. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Tsai JL, & Chiang K-HS (2004). The emotional integration of childhood experience: physiological, facial expressive, and self-reported emotional response during the adult attachment interview. Developmental Psychology, 40(5), 776. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstein DS, & Horowitz HA (1996). Adolescent attachment and psychopathology. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(2), 244. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal NL, & Kobak R. (2010). Assessing adolescents’ attachment hierarchies: Differences across developmental periods and associations with individual adaptation. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(3), 678–706. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00655.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Rholes WS, & Nelligan JS (1992). Support seeking and support giving within couples in an anxiety-provoking situation: The role of attachment styles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(3), 434. 10.1037/0022-3514.62.3.434 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Oriña MM, & Grich J. (2002). Working models of attachment, support giving, and support seeking in a stressful situation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(5), 598–608. 10.1177/0146167202288004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slaby R, Guerra N. (1988). Cognitive mediators of aggression in adolescent offenders: 1. Assessment. Developmental Psychology, 24, 580–588. 10.1037/0012-1649.24.4.580 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JA, Newcomb MD, & Bentler PM (1986). Stability and change in personality: A longitudinal study from early adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Research in Personality, 20(3), 276–291. 10.1016/0092-6566(86)90135-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg SJ, Davila J, & Fincham F. (2006). Adolescent marital expectations and romantic experiences: Associations with perceptions about parental conflict and adolescent attachment security. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 314–329. 10.1007/s10964-006-9042-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan JS, Hessel ET, Loeb EL, Schad MM, Allen JP, & Chango JM (2016). Long-Term Predictions from Early Adolescent Attachment State of Mind to Romantic Relationship Behaviors. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(4), 1022–1035. 10.1111/jora.12256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH (1997). Attachment, emergent morality, and aggression: Toward a developmental socioemotional model of antisocial behaviour. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 21, 703–728. 10.1080/016502597384631 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward MJ, & Carlson EA (1995). Associations among adult attachment representations, maternal sensitivity, and infant-mother attachment in a sample of adolescent mothers. Child Development, 66(1), 69–79. 10.2307/1131191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters HS, & Waters E. (2006). The attachment working models concept: Among other things, we build script-like representations of secure base experiences. Attachment & Human Development, 8, 185–197. 10.1080/14616730600856016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimer BL, Kerns KA, & Oldenburg CM (2004). Adolescents’ interactions with a best friend: Associations with attachment style. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 88(1), 102–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2004.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P. (2004). Attachment representations and characteristics of friendship relations during adolescence. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 88(1), 83–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2004.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]