Abstract

Microglial cells regulate neural homeostasis by coordinating both immune responses and clearance of debris, and the P2X7 receptor for extracellular ATP plays a central role in both functions. The P2X7 receptor is primarily known in microglial cells for its immune signaling and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. However, the receptor also affects the clearance of extracellular and intracellular debris through modifications of lysosomal function, phagocytosis, and autophagy. In the absence of an agonist, the P2X7 receptor acts as a scavenger receptor to phagocytose material. Transient receptor stimulation induces autophagy and increases LC3-II levels, likely through calcium-dependent phosphorylation of AMPK, and activates microglia to an M1 or mixed M1/M2 state. We show an increased expression of Nos2 and Tnfa and a decreased expression of Chil3 (YM1) from primary cultures of brain microglia exposed to high levels of ATP. Sustained stimulation can reduce lysosomal function in microglia by increasing lysosomal pH and slowing autophagosome-lysosome fusion. P2X7 receptor stimulation can also cause lysosomal leakage, and the subsequent rise in cytoplasmic cathepsin B activates the NLRP3 inflammasome leading to caspase-1 cleavage and IL-1β maturation and release. Support for P2X7 receptor activation of the inflammasome following lysosomal leakage comes from data on primary microglia showing IL-1β release following receptor stimulation is inhibited by cathepsin B blocker CA-074. This pathway bridges endolysosomal and inflammatory roles and may provide a key mechanism for the increased inflammation found in age-dependent neurodegenerations characterized by excessive lysosomal accumulations. Regardless of whether the inflammasome is activated via this lysosomal leakage or the better-known K+-efflux pathway, the inflammatory impact of P2X7 receptor stimulation is balanced between the autophagic reduction of inflammasome components and their increase following P2X7-mediated priming. In summary, the P2X7 receptor modulates clearance of extracellular debris by microglial cells and mediates lysosomal damage that can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. A better understanding of how the P2X7 receptor alters phagocytosis, lysosomal health, inflammation, and autophagy can lead to therapies that balance the inflammatory and clearance roles of microglial cells.

Keywords: P2X7, microglia, phagocytosis, autophagy, lysosomes, cathepsin B, NLRP3, neuroinflammation

Introduction

Microglia act as the innate immune effector cells of the central nervous system (CNS; Gehrmann et al., 1995; Kofler and Wiley, 2011), and their contribution to inflammatory signaling pathways between neurons, astrocytes, and other components of neural tissue largely sets the magnitude of the immune responses. Although microglia constitute a relatively small number of cells in the CNS (Mittelbronn et al., 2001), their position as the primary defensive cells in neural systems places them at the crossroads of health and disease. The inflammatory responses mediated by microglial cells are regulated by multiple stimuli that help ensure an appropriate response. Extracellular ATP acting at the P2X7 receptor is widely recognized as a pivotal player in microglial signaling for triggering the release of neurotrophic factors, cytokines such as IL-6, and the activation of the NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome (Kierdorf and Prinz, 2017).

In addition to their role in inflammatory signaling, microglial cells make major contributions to the clearance of material from extracellular space. Their ability to phagocytose and degrade apoptotic cells, bacteria, and engulfed synaptic material contributes to neural homeostasis (Nau et al., 2014; Bilimoria and Stevens, 2015). Furthermore, the dysfunctional clearance of proteins and lipids by microglia is increasingly implicated in neurodegenerative disorders. For example, undegraded myelin and lipid droplets have been observed within microglia from aging models (Safaiyan et al., 2016; Marschallinger et al., 2020). The incomplete removal of amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposits contributes to waste accumulation and “microglial exhaustion” in pathologies such as Alzheimer’s disease (Streit et al., 2018, 2020). These observations suggest that defective clearance of waste material by microglia may contribute to the mechanisms underlying some age-related neurodegenerations.

The multiple steps required for the phagocytosis and degradation of extracellular waste material by microglial cells are tightly coordinated. Several lines of evidence suggest the P2X7 receptor is involved in regulating microglial clearance, including effects on phagocytosis, autophagy, and lysosomal function. This review examines the evidence for the role of the P2X7 receptor in regulating these steps and highlights the role of the P2X7 receptor in modulating both the clearance and inflammatory components of microglial function.

Extracellular Atp and P2x7 Receptors

Purinergic signaling pathways evolved early, and the ubiquitous presence of high cytoplasmic adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels, combined with multiple pathways for ATP release, ensured widespread use of ATP as an extracellular transmitter. ATP can be released physiologically through ion channels or from vesicles loaded with ATP (Beckel et al., 2018; Dosch et al., 2018). Increased extracellular ATP is often associated with pathological stress; this rise in extracellular ATP concentration can result from upregulation of channel and vesicular release pathways, in addition to the release of cytoplasmic ATP upon cell rupture. Signaling is largely mediated by stimulation of ionotropic P2X or metabotropic P2Y receptors by ATP, the dephosphorylated nucleotide adenosine diphosphate (ADP), or pyrimidine analogs (Calovi et al., 2019). Adenosine produced by the subsequent dephosphorylation can act at a distinct set of metabotropic receptors, adding to the complexity. This also emphasizes the role of extracellular dephosphorylating enzymes in coordinating purinergic signals.

While most cell types possess some combination of purinergic receptors, purinergic signaling plays a particularly important role in microglial cells. The P2Y12 receptor for ADP is widely recognized as a marker for microglial cells; P2Y12 receptor expression is greatest on the ramified processes, and stimulation makes a major contribution to chemoattractant responses of microglial cells (Moore et al., 2015; Mildner et al., 2017). Stimulation of the adenosine A2A receptor on microglial cells contributes to the characteristic amoeboid morphology during microglial activation accompanying brain inflammation (Orr et al., 2009).

The ionotropic P2X7 receptor is especially relevant to immune responses in microglial cells due to its requirement for high concentrations of ATP, its lack of inactivation, the distribution of particular splice variants amongst immune cells, the multiple interactions of its extended cytoplasmic tail, and its association with the opening of a large transmembrane pore (Di Virgilio et al., 2017). Receptor opening is stimulated by levels of ATP approaching the millimolar range, several orders of magnitude higher than required for other P2X or P2Y receptors (Coddou et al., 2011). While this was originally interpreted to mean the receptor was only activated by large levels of ATP released following cell rupture, the presence of the P2X7 receptor on several post-mitotic cells, combined with the identification of pannexin channels as ATP conduits localized adjacent to P2X7 receptors, provided for a role for the receptor in more widespread signaling scenarios (Miras-Portugal et al., 2017). Like other members of the P2X family, binding of ATP leads to the opening of a cation-selective channel that allows Ca+ and Na+ influx, and K+ efflux. However, in some circumstances stimulation also leads to the opening of a pore permeable to larger macromolecules up to 900 Da; whether this pore represents a more dilated state of the P2X7 channel or the recruitment of additional proteins such as pannexin channels remains unresolved, despite intense investigation (Di Virgilio et al., 2018). The lack of P2X7 channel inactivation in the continued presence of agonist has been attributed to the palmitoylated C-cys anchor retaining the gate in the open position (McCarthy et al., 2019). This lack of inactivation makes regulation of agonist levels critical for both initiating the signal and also shutting it down in a timely manner; there are parallels with the NMDA channel for glutamate in both the central role in signaling and the damage following overstimulation of both channels. The human P2X7 receptor possesses multiple splice variants, and the variant including the large 240 AA carboxy tail is usually associated with immune cells; this carboxy tail contains many of the binding sites associated with complex inflammatory interactions (Collo et al., 1997; Kaczmarek-Hajek et al., 2018; Kopp et al., 2019).

While the P2X7 receptor was originally referred to as “death receptor,” more recent work indicates the contribution of the receptor is much more nuanced, with participation in a variety of signaling events; stimulation can even lead to a proliferation in microglial cells (Bianco et al., 2006). These varied outcomes from the P2X7 receptor may be explained by differences in splice variant expression, agonist availability, and other factors still under investigation (Adinolfi et al., 2010; Di Virgilio, 2020). While excessive stimulation can lead to microglial cell death, the effects of the P2X7 receptor on the endolysosomal axis discussed here usually do not lead to cellular demise but have sustained pathological consequences for microglial clearance instead.

Microglia, Inflammation, and Clearance

Microglia are morphologically plastic cells, existing in a variety of states in response to environmental stimuli. In the “resting” state, often referred to as M0, microglia engage in a constant sampling of their surroundings, with long ramified extensions surveying the neuronal milieu (Nimmerjahn et al., 2005). Microglia are constantly molded by environmental cues and respond to localized differences so that even in the resting state the population shows great heterogeneity (Lenz and Nelson, 2018). Once microglia are challenged with immunomodulatory substances, they enter an “activated” state in an attempt to maintain homeostasis. Although there is a range of “activated” states, they have traditionally been characterized into pro-inflammatory (“classical activation,” M1) and pro-phagocytic (“alternative activation,” M2) states (Colton, 2009). The M2 state itself can be subdivided into the M2a state associated with repair/regeneration functions, the M2b state associated with immunomodulatory functions, and the M2c state associated with an acquired deactivation phenotype (Mantovani et al., 2004; Chhor et al., 2013; Martinez and Gordon, 2014). Progression into these activation states follows clear triggers; application of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) leads to the M1-like states, application of Interleukin (IL) IL-4 or IL-13 triggers the M2a state, ligation of immunoglobulin Fc-gamma-receptors that results in IL-12 expression, increased IL-10 secretion, and HLA-DR expression leads to the M2b state, while IL-10 is associated with the M2c state (Akhmetzyanova et al., 2019). The states themselves are defined by proteomic or genetic markers, with IL-1β (Il1b) or NOS2/iNOS (Nos2) for M1, Arg1 (Arg1) or Chil3/YM1 (Chil3) for M2a, IL-10 (Il10) or CCL1 (Ccl1) for M2b and CD163 (Cd163), MMP8 (Mmp8), and VCAN (Vcan) for M2c (Stumpo et al., 2003; Mantovani et al., 2004; Boche et al., 2013; Chhor et al., 2013; Cherry et al., 2014; Martinez and Gordon, 2014; Lurier et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019). However, recent investigations indicate this categorization is far too simplistic, and the different microglial states are better represented as a spectrum of combinations (Morganti et al., 2016; Lively and Schlichter, 2018). That said, the basic divisions between microglial states associated with increased inflammatory signals and those linked to increased phagocytosis are important to consider when interpreting the varied effects of the P2X7 receptor, and would benefit from a more thorough examination in the future.

The functional responses associated with the various microglial states usually help maintain the optimal activity of the neural tissue, a connection that can be overlooked when research is focused on pathology. However, the central role of microglia in coordinating the immune responses can lead to aberrant behavior upon excessive stimulation or impaired restraint. Microglia dysfunction has been implicated in several disease states, including schizophrenia (Tay et al., 2017), autism (Liao et al., 2020), ischemic stroke (Kanazawa et al., 2017), traumatic brain injury (Loane and Kumar, 2016), Alzheimer’s disease (Streit et al., 2020), Parkinson’s disease (Ferreira and Romero-Ramos, 2018) and frontotemporal dementia (Hickman et al., 2018). Understanding how to maintain the beneficial activities of microglia while limiting their destructive actions remains a key challenge, and the P2X7 receptor is likely to contribute to the balance with its central role in coordinating both inflammation and clearance.

The effects of the P2X7 receptor on microglial clearance are less well studied than those on inflammation, and throughout this review, results obtained from primary and cultured microglial cells are supplemented by work on macrophages and monocytes. While microglial cells share many features with their peripheral cousins the macrophages, including recognition through the widely used markers Iba1 or Cx3CR1, microglia differ from peripheral macrophages in several ways (Ransohoff and Perry, 2009; Li and Barres, 2018). For example, microglia differ from macrophages in protein expression (Butovsky et al., 2014; Bennett et al., 2016), turnover (Lawson et al., 1990; Askew et al., 2017), inflammatory response (Burm et al., 2016; Zarruk et al., 2018), and physiological regulation (Majumdar et al., 2007, 2008, 2011). Microglia originate from early myeloid progenitor cells that migrate from the yolk sac, with minimal CNS contribution from peripheral macrophages (Ginhoux et al., 2010; Gomez Perdiguero et al., 2015; Bennett et al., 2018). Of particular relevance here is the increased expression of degradative lysosomal enzymes such as dipeptidyl peptidase, tripeptidyl peptidase, and Cathepsin D (CatD) in microglial cells as compared to macrophages (Majumdar et al., 2007). Also important in this regard are differences between microglial cells from inflamed CNS and those recruited from blood-derived monocytes; the substantial differences recently identified between these cell types implies their response to the P2X7 receptor could well differ (Lapenna et al., 2018; Borst and Prinz, 2020; Yu et al., 2020). While the relative paucity of data from microglial cells on how the P2X7 receptor alters clearance means that some of the information presented in this review has been obtained from macrophages, the reader should be aware that application of results from macrophages to microglial cells has limitations.

P2x7 Receptors and Microglial States

The P2X7 receptor is widely recognized for its inflammatory actions. Stimulation of the P2X7 receptor can result in the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-6 in many cell types (Adinolfi et al., 2018; Burnstock and Knight, 2018; Shao et al., 2020). Additionally, stimulation of the P2X7 receptor leads to the nuclear translocation of transcription factor nuclear factor kappa-light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) which has been demonstrated to elevate gene expression of Tnfa, Cox2, and Il1b in microglia (Ferrari et al., 1997). While these markers are widely associated with the pro-inflammatory M1 state of microglia, the pattern of genes activated by stimulation of the P2X7 receptor in microglial cells is likely to be complex. M2 state markers Arg1 and CD163 occurred following 15-min stimulation with Benzoylbenzoyl-ATP (BzATP), a selective agonist of P2X7 (Fabbrizio et al., 2017). Together this may indicate a mixed activation state similar to what has been observed in microglia following traumatic brain injury (Morganti et al., 2016). Furthermore, isolated rat primary microglia challenged with LPS revealed upregulated expression of gene Arg1 and its protein product (Lively and Schlichter, 2018). A direct comparison of LPS and IL-4 challenge to primary mouse microglia indicate that IL-4 induces an exponentially higher expression of Arg1 compared to LPS (Chhor et al., 2013), however, suggesting the response is complex. Microglial activation state and autophagy may be interrelated, with autophagy induction polarizing microglia towards the M1 state, while induction of M2 state can itself increase autophagy (Fabbrizio et al., 2017).

P2x7 Receptors and Phagocytosis by Microglial Cells

Phagocytosis of extracellular material is a central function of microglial cells. Materials bound to phagocytic receptors are taken in through the phagocytic cup and delivered to the endocytic system for pathogen destruction, degradation, or sorting (Solé-Domènech et al., 2016). Induction of the M2a state leads to an increase in cell-specific receptors associated with phagocytosis such as CD163, TREM2, and Dectin-1 (Willment et al., 2003; Neumann and Takahashi, 2007; Kowal et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2012; Cui et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020). However, the expression of phagocytosis receptors does not necessarily correlate with increased phagocytosis, and the relationship between induction into the M2a state and the rate of phagocytosis is a matter of debate (Márquez-Ropero et al., 2020). Induction of both M1 and M2 microglial phenotypes was found to reduce deposits of amyloid-beta in vivo (Tang and Le, 2016), while the addition of IL-4 suppressed macrophage phagocytosis of beads in vitro (Moreno et al., 2007). Stimulation of receptors such as TREM2 and MerTK modulate microglial phagocytosis (Nomura et al., 2017; Janda et al., 2018), but the relationship between the P2X7 receptor and microglial phagocytosis by microglia are more complex. For example, P2X7 receptor expression was not upregulated with the challenge by lipopolysaccharides (Raouf et al., 2007), but was upregulated with exposure to amyloid-beta (1–42; McLarnon et al., 2006), suggesting P2X7 expression is a specific response.

One of the most intriguing connections between the P2X7 receptor and phagocytosis involves its identity like a scavenger receptor, whereby the receptor increases phagocytosis in the absence of external agonist ATP (Gu et al., 2010, 2011; Gu and Wiley, 2018; Figure 1A). This role of the P2X7 receptor differs considerably from other functions in that activity as a scavenger receptor is reduced when extracellular ATP rises. For example, phagocytic uptake of non-opsonized beads by cells of the human monocyte THP-1 cell line was reduced by blocking the receptor with antibodies against the extracellular domain of the P2X7 receptor (Gu et al., 2010). A similar reduction in phagocytosis of E. coli bacteria by human-derived monocytes was also induced by a P2X7 receptor antibody (Ou et al., 2018). Pharmacological support for the P2X7 receptor contribution was shown in human microglial cells when stimulation of the P2X7 receptor with agonist BzATP reduced phagocytosis of fluorescent-tagged E. coli bioparticles, while P2X7 antagonist A438079 reversed the effect of BzATP and enhanced phagocytosis of these bioparticles (Janks et al., 2018). Further support for a role for the unstimulated P2X7 receptor in phagocytosis was shown on a molecular level in experiments where siRNA knockdown of the P2X7 receptor reduced phagocytosis in the absence of agonist in isolated human monocytes, while overexpression of the P2X7 receptor in HEK293 cells increased phagocytosis (Gu et al., 2010, 2011).

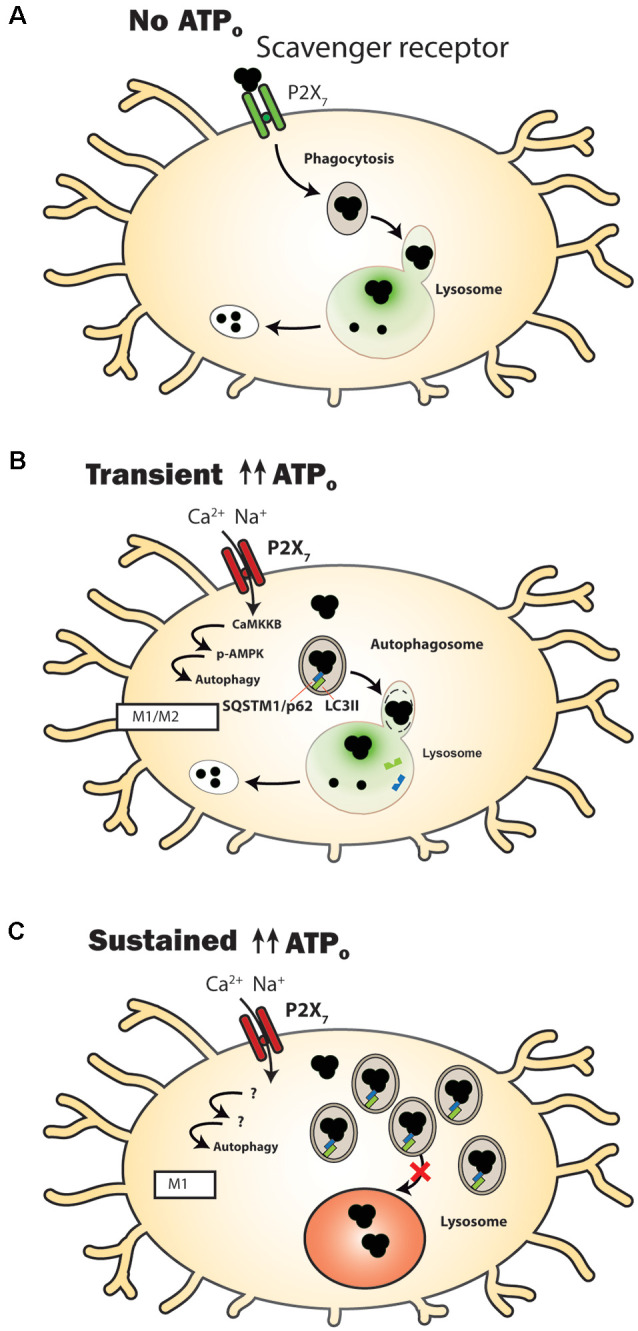

Figure 1.

P2X7 receptor modulation of clearance pathways in microglial cells. (A) Under control conditions when extracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels (ATPo) are too low to activate the P2X7 receptor, it acts as a scavenger receptor to aid in the phagocytosis of extracellular waste. The luminal pH of lysosomes in microglial cells is sufficiently acidic (green) to enable efficient degradative enzyme activity. (B) Following transient stimulation with high concentrations of ATPo, the P2X7 receptor no longer acts as a scavenger receptor. Autophagy is stimulated, shown by a transient rise in levels of autophagosomal lipid marker microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3-II (LC3-II). Material is degraded and microglia express genes and proteins associated with a mixed M1/M2 activation state. (C) A more prolonged stimulation of the P2X7 receptor leads to an elevated lysosome pH (red), with autophagosomal contents being delivered extracellularly instead of to the lysosome. Markers of accumulation, including LC3-II (green) and sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1/p62; blue) are elevated. Microglia express genes and proteins associated with an M1 activation state.

Details about the mechanisms of P2X7 as a scavenger receptor show a complex pattern. Extracellular residues 306–320 of the P2X7 receptor were shown to bind to beads, bacteria, and apoptotic cells (Gu et al., 2011). Intracellular regions of the P2X7 receptor are bound to non-muscle myosin heavy chain IIA (NMMHC IIA) and thus the cytoskeleton (Gu et al., 2009, 2010), consistent with a pathway for phagocytosis of material into the cell. The addition of ATP led to dissociation of NMMHC IIA from the P2X7 receptor and reduced phagocytosis with roughly the same kinetics as channel gating, suggesting a common link. Overexpression of NMMHC IIA reduced the pore-opening activity that occurred with P2X7 receptor agonist presentation, reinforcing the notion that the receptor may switch between its phagocytic and conductive identities (Gu et al., 2009). However, P2X7 receptor-selective antagonists blocked pore formation but not phagocytic activity in human monocytes (Ou et al., 2018), indicating that phagocytosis is driven by the closed state of the receptor, and antagonist binding sites are distinct from the phagocytic targets (Gu and Wiley, 2018). This suggests these P2X7 antagonists can block channel activity without affecting phagocytosis, a useful selection trait if the goal is to reduce the balance between inflammatory activity and phagocytosis (Fletcher et al., 2019). Transient stimulation of the P2X7 receptor in human-derived microglia decoupled the receptor from the cytoskeleton and eliminated its ability to phagocytose bioparticles while also activating caspase-1 (Gu et al., 2009, 2010). Overall, the ability of the P2X7 receptor to enhance phagocytosis in the absence of extracellular ATP presents a critical step in understanding how the receptor manipulates microglial clearance of extracellular debris. Moreover, P2X7 receptor phagocytic activity is likely restricted to microglia, as phagocytosis by human monocyte-derived macrophages was inhibited with a glycoprotein-rich fraction of serum (Gu et al., 2012). Readers are directed to the excellent review by Gu and Wiley for more details about the P2X7 receptor as a scavenger receptor (Gu and Wiley, 2018).

While the ability of the P2X7 receptor to act as a scavenger receptor in the absence of an agonist is strongly supported by the evidence above, it should be noted that not all experimental findings agree with this concept. For example, recent work in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) suggests that stimulation of the P2X7 receptor enhances uptake of pHRodo-tagged bacterial bioparticles, as uptake was reduced following exposure to P2X7 receptor inhibitor A740003 and by reduction of extracellular ATP with the hydrolyzing enzyme apyrase (Zumerle et al., 2019); phagocytosis was not inhibited with antagonists AZ10606120 and A438079, however (Allsopp et al., 2018). Whether these differences indicate a characteristic of BMDMs or just experimental deviation remains to be determined.

P2x7 Receptors and Regulation of Lysosome Ph and Autophagosome Maturation

Lysosomes are membrane-bound organelles with an acidic lumen that are responsible for the degradation of extracellular materials delivered through the endocytic pathway, or of intracellular materials delivered via autophagy. Degradation is accomplished by several intraluminal hydrolases, whose enzymatic activity is optimally at low pH levels (Stoka et al., 2016). In addition to being necessary for optimal degradative activity, a low lysosomal pH is important for maintaining the electrical potential across the lysosomal membrane, the transport of signaling molecules stored in lysosomes such as Ca2+ and ATP, and for the fusion of the lysosomal membrane with incoming autophagosomes and endosomes (Xu and Ren, 2015; Perera and Zoncu, 2016). Elevation of lysosomal pH reduces degradation of phagocytosed material in numerous cell types (Sarkar et al., 2009) and leads to autophagic backup and reduced protein degradation (Klionsky et al., 2021), making the restoration of an acidic lysosomal pH a key target for the amelioration of diseases of accumulation (Guha et al., 2014).

The ability of P2X7 receptor stimulation to elevate lysosomal pH in numerous cell types including microglia has important implications for clearance (Figures 1B,C). The P2X7 receptor deacidified lysosomes in microglial cells; stimulation of the MG6 microglia cell line with ATP (Takenouchi et al., 2009) or the BV2 microglial cell line with P2X7 receptor agonist BzATP (Sekar et al., 2018) elevated lysosomal pH. The ability of P2X7 receptor antagonists to prevent this de-acidification supported a role for the P2X7 receptor in this rise in lysosomal pH. It should be noted, however, that P2X7 receptor stimulation of macrophages infected with bacteria acidified lysophagosomes (Fairbairn et al., 2001).

The relatively high lysosomal pH of microglial cells under baseline conditions differs from peripheral macrophages and other cells, with a reported value of 6.0 as compared to 4.5–5 in most cell types (Majumdar et al., 2007). However, the lysosomal pH in microglia is dynamic, and several pathways are involved in lowering the luminal pH in preparation for degradative activity. For example, stimulation with microglial activating compound Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor (MCSF) or LPS lowered lysosomal pH and enhanced degradation of protofibrillar amyloid-beta (fAβ; Majumdar et al., 2007). MCSF putatively polarizes microglia to the M2 state while LPS polarizes them towards the M1 state (Cherry et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2015). This study also demonstrated that forskolin lowered lysosomal pH and increased fAβ degradation, and the enhanced degradation induced by MCSF was blocked by inhibition of protein kinase A or chloride transport, consistent with cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and chloride contributing to lysosomal acidification. The movement of chloride transporter CLC-7 into the lysosomal membrane to enact Cl− counterion transport was subsequently identified as a key mechanistic step in luminal acidification (Majumdar et al., 2011). Future experiments are needed to determine whether baseline lysosomal pH differs in microglia of the pro-phagocytic M2 state and whether the rise in lysosomal pH associated with P2X7 receptor stimulation is altered in this subset of cells.

A rise in lysosomal pH will usually reduce rates of degradation or autophagy. After extracellular debris is engulfed into the cell via phagocytosis, it moves through a membrane enclosure called an autophagosome, which eventually binds to and fuses with the lysosome for hydrolase-mediated degradation. There are suggestions that stimulation of the P2X7 receptor may reduce autophagosome-lysosome fusion to further reduce bacterial clearance. ATP reduced the fluorescence signal in MG6 microglial cells that had phagocytosed pHrodo-BioParticles (Takenouchi et al., 2009); as pHrodo-BioParticles fluoresce brighter in the lower pH levels of lysosomes, this implied a reduced delivery to the lysosomal lumen, although this is also consistent with a de-acidification of that compartment. Furthermore, exposure to 2.5 mM ATP for 4 h resulted in detection of the transferrin receptor protein, the intermediate form of endolysosomal protease CatD and autophagosomal lipid marker microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3-II (LC3-II) into the supernatant, consistent with incomplete autophagosome-lysosome maturation and elevated secretion into the extracellular space (Takenouchi et al., 2009) via a non-classical secretory pathway (Dubyak, 2012). Lysosome destabilization can also lead to the release of lysosomal cathepsins into the cytoplasm (Nakanishi, 2020). Intracellular cathepsin B (CatB) is known to promote cleavage of cytokine IL-1β via caspase one after stimulation of the P2X7 receptor (Figure 2). Furthermore, CatB activity can polarize microglia closer to M1, with microglia isolated from hippocampi after hypoxia/ischemia expressing significantly higher levels of Nos2, Tnfa, and IL1b not observed in those from CatB−/− mice (Ni et al., 2015).

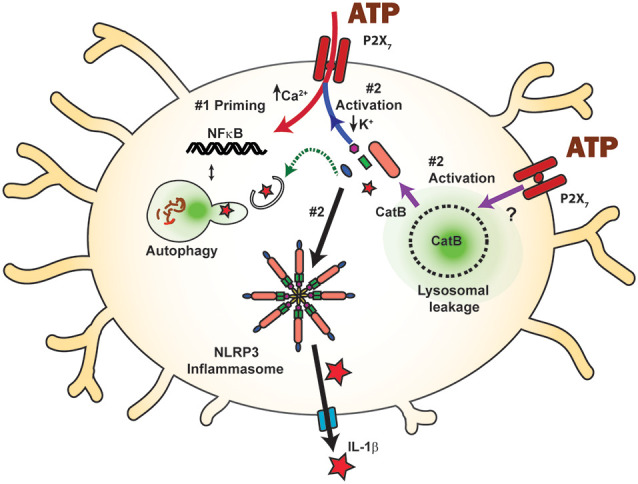

Figure 2.

Inflammasome activation by the P2X7 receptor and the balance between priming and autophagic degradation of inflammasome components. Stimulation of the P2X7 receptor triggers the assembly and activation (step #2) of the NLRP3 inflammasome following efflux of K+ through the open channel (blue arrow), eventually leading to cleavage of pro-IL-1β (red star) into the mature form and release through the gasdermin D pore (blue). The P2X7 receptor can also activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and subsequent IL-1β release by raising cytoplasmic cathepsin B (CatB), following its initiation of lysosomal leakage through an unknown mechanism (purple arrows). P2X7 receptor stimulation can prime inflammasome components via NF-κB (step #1, red arrow) and increase available inflammasome components. Component levels can also be decreased following autophagic degradation (green arrow), limiting the inflammatory potential of P2X7 receptor stimulation. The balance between priming and autophagic degradation will influence the inflammatory impact of P2X7 receptor stimulation.

The above contrasts with in vitro studies of human and mouse macrophages which suggest that the P2X7 receptor can enhance phagosome-lysosome fusion and increases degradation of bacteria in a calcium and phospholipase D (PLD)-dependent manner (Kusner and Barton, 2001; Stober et al., 2001; Coutinho-Silva et al., 2009; Corrêa et al., 2010). Mouse macrophages that internalized Mycobacterium bovis Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) followed by exposure to 3 mM ATP for 4 h showed increased colocalization between BCG and lysosome marking-dye Lysotracker Red (Fairbairn et al., 2001). P2X7 receptor stimulation reduced the viability of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in primary human macrophages and THP-1 derived macrophages, dependent upon Ca2+ influx and activation of PLD (Kusner and Adams, 2000; Kusner and Barton, 2001). Inhibition of PLD was independent of Ca2+ influx and correlated with the reduction of phagosome-lysosome fusion. However, internal calcium stores were involved with the loss of internalized M. Bovis that were associated with high levels of extracellular ATP (Stober et al., 2001). These differences between effects of the P2X7 receptor on phagocytosis by macrophages vs. microglia again stress the need for further examination of microglia alone.

Manipulation of Autophagy by The P2x7 Receptor

Autophagy is the process by which intracellular material is identified, packaged, and trafficked for lysosomal degradation, and several lines of evidence suggest the P2X7 receptor can modulate the autophagy process (Figure 1). Autophagy is normally prevented by the mammalian target of rapamycin 1 (mTOR1); inhibition of mTOR by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) can thus initiate autophagy (Nazio et al., 2013; Hindupur et al., 2015). Recruitment of LC3 to membranes leads to the formation of nascent autophagosomes, and increased clustering of the membrane-bound phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated LC3-II is a common marker for autophagy initiation (Klionsky et al., 2021). Autophagy, by definition, focuses on processing material produced within microglial cells, but autophagic and phagocytic pathways run in parallel. While autophagy (Plaza-Zabala et al., 2017), phagocytosis (Sierra et al., 2013; Solé-Domènech et al., 2016), and their intersection with inflammation (Su et al., 2016) within microglia have been individually reviewed, the specific effects of P2X7 receptor stimulation on the autophagic pathway in microglia merit special attention.

Transient stimulation of the P2X7 receptor with ATP or BzATP elevates LC3-II levels in isolated primary mouse microglia, with LC3-II returning to basal levels 4 h after receptor stimulation (Takenouchi et al., 2009). A similar rise in LC3 was found in the MG6 (Takenouchi et al., 2009) and BV2 (Sekar et al., 2018) microglial cell lines. Receptor involvement is supported by a reduced LC3-II response to stimulation in microglial cells from P2X7−/− mice and in the presence of P2X7 antagonists. The rise in LC3-II was greater in microglial cells from the SOD1-G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) than the wild type, and peaked 15 min after agonist presentation (Fabbrizio et al., 2017).

Elevation of LC3-II can represent autophagic induction or autophagic backup (Klionsky et al., 2021); the ability of the P2X7 receptor to elevate lysosomal pH, combined with the autophagic reduction that accompanies lysosomal de-acidification (Kawai et al., 2007), demands particular care when investigating how the P2X7 receptor increases LC3-II levels. Levels of LC3-II were increased further when proton pump inhibitor Bafilomycin A1 was given concurrently with BzATP (Fabbrizio et al., 2017); while this is a classical test to distinguish between autophagy induction and inhibition, the relatively small increase, combined with the absence of absolute pH measurements, does not rule out an effect of lysosomal de-acidification on rising LC3-II levels. The BzATP-mediated rise in LC3-II was dependent upon extracellular calcium in microglia and THP monocytes (Biswas et al., 2008; Takenouchi et al., 2009), but extracellular calcium was also necessary for lysosomal deacidification (Guha et al., 2013). However, additional observations support the ability of the P2X7 receptor to raise LC3-II by inducing autophagy, independent of its effects on lysosomal pH. In microglia derived from the superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1)-G93A mouse model, sequestosome-1 SQSTM1/p62 levels were reduced by 15 min BzATP but increased by a sustained stimulation with BzATP for 6 h (Fabbrizio et al., 2017). As SQSTM1/p62 normally binds to cargo targeted for autophagic degradation by the lysosome and is itself degraded, p62 accumulation is a standard indicator of autophagic backup due to a reduced lysosomal function (Klionsky et al., 2021). However, SQSTM1/p62 is a multifunctional protein implicated in several cellular interactions such as adipogenesis, nutrient sensing, oxidative stress reactions though nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2), and regulation of NF-κB. Additionally, both Nrf2 and NF-κB have transcriptionally upregulated expression of SQSTM1/p62 (Puissant et al., 2012; Sánchez-Martín et al., 2019). As such, the complex time course linking the P2X7 receptor to p62 elevation may reflect involvement of pathways in addition to degradation.

The activation of the AMPK pathway following stimulation of P2X7 receptors also provides support for autophagic induction by the P2X7 receptor, given the role of AMPK in regulating autophagy induction (Kim et al., 2011). For example, BV2 cells stimulated with BzATP showed an elevation of p-AMPK, consistent with autophagy induction (Sekar et al., 2018). LC3-II protein levels were reduced with siRNA against AMPK, AMPK inhibition with Compound C, or the addition of mitochondrial antioxidant MitoTEMPO. The activation of AMPK by calcium-sensitive calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase beta (CaMKKβ; Bootman et al., 2018) may link calcium influx through the P2X7 channel and AMPK activation. The demonstration of rapid phosphorylation of mTOR after BzATP application also supports autophagy induction downstream from AMPK-activation (Fabbrizio et al., 2017). Whether P2X7 receptor signaling leads to canonical inhibition of mTOR, activation of AMPK or additional pathways requires further clarification. Future investigations must control for the effect of P2X7 receptors on lysosomal pH, and the considerable feedback systems mediated by Transcription factor EB (TFEB) that are activated by this rise in pH (Zhitomirsky et al., 2018). However, the identification of intersections between the P2X7 receptor and autophagy pathways is an active field of investigation in microglial research and multiple targets should soon emerge.

Effect of Priming and Autophagy on P2x7 Receptor-Mediated Inflammatory Responses

While this review is focused on how the P2X7 receptor modifies microglial clearance, autophagic clearance can also modulate the impact of the P2X7 receptor on inflammation. The P2X7 receptor is well known for its association with increased inflammatory signals and cytokine release (Figure 2); its interaction with the NLRP3 inflammasome is perhaps the most widely recognized (Di Virgilio et al., 2017), and the P2X7 receptor was the most potent activator of the NLRP3 inflammasome in N13 microglial cells (Franceschini et al., 2015). The NLRP3 inflammasome is a multimeric compound consisting of NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3, the apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing caspase recruitment domain (ASC), and procaspase-1 (Swanson et al., 2019). The resulting release of master cytokine IL-1β can influence many immune signals, and the inflammasome is tightly regulated to reflect its central role. In the first “priming” step, the availability of inflammasome components is controlled. In the second step, these components assemble to form the inflammasome itself, resulting in sequential cleavage of caspase-1 and then cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 into their mature forms. These mature cytokines exit the cell through the cleaved gasdermin D pore, enabling cytokine release into extracellular space where they initiate a variety of inflammatory responses. The efflux of K+ from the cell is a key signal to assemble component proteins into the inflammasome, and this efflux is frequently associated with the opening of the P2X7 receptor (Muñoz-Planillo et al., 2013; Katsnelson et al., 2015; Swanson et al., 2019).

While the P2X7 receptor is closely associated with the secondary activation stage of the NLRP3 inflammasome, reports also link it to the first priming phase. Priming is often initiated experimentally with the Toll-Like Receptor 4 agonist LPS, which leads to translocation of transcription factor NF-κB to the nucleus, resulting in the transcription of inflammasome components (Kahlenberg et al., 2005). However, several studies suggest that the P2X7 receptor can also fulfill the priming step, initiating translocation and IL-1β transcription itself. N9 mouse microglia cells exposed to ATP or BzATP demonstrated NF-κB activation, though the response was delayed when compared to LPS-mediated activation (Ferrari et al., 1997). This study also demonstrated that the NF-κB/DNA complex induced by P2X7 receptor signaling differed from that induced by LPS, in that ATP induced a p65 homodimer, rather than the p65/p50 heterodimers found with LPS. Work in HEK293T cells and the RAW264.7 macrophage cell line indicate that the P2X7 receptor also interacts with myeloid differentiation primary-response protein 88 (MyD88), a common adaptor protein for TLRs (Liu et al., 2011). P2X7 receptor-induced NF-κB translocation has been demonstrated in osteoclasts (Korcok et al., 2004) and osteoblasts (Genetos et al., 2011), suggesting that P2X7 receptor activation of NF-κB may be a common mechanism for priming inflammasome components. In astrocytes, data showing inflammasome priming of isolated cells by the P2X7 receptor was supplemented by a role in vivo, in which increased expression of IL-1β followed injection of BzATP and the pressure-dependent rise in IL-1β was absent in P2X7−/− mice (Albalawi et al., 2017). This ability of P2X7 receptor activation to both prime and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome places it in a very powerful position to regulate innate immune responses.

Numerous studies highlight interactions between autophagy and the NLRP3 inflammasome (Biasizzo and Kopitar-Jerala, 2020); while the specific role of the P2X7 receptor is usually not involved, autophagic degradation of inflammasome components is predicted to regulate the ability of the P2X7 receptor to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Increased autophagy is associated with decreased NLRP3 inflammasome function in vivo in rodent microglial cells (Chen et al., 2019), and in primary microglia cells (Cho et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2019; Han et al., 2019). Autophagic degradation of inflammasome components was also suggested by studies in the BV2 cell line (Shao et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2015; You et al., 2017; Han et al., 2019), in THP-1 human macrophages (Liu et al., 2018), and in BMDCs or immortalized bone marrow-derived macrophages (Harris et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2017). Induction of autophagy by a small molecule reduced NLRP3 expression in microglial cells and inflammasome activation (Han et al., 2019). Suppressed caspase-1 activation may lead to enhanced autophagy in microglial cells following inflammasome silencing (Lai et al., 2018). Primary microglia derived from mice deficient in autophagy gene Beclin-1 (BECN−/−) had less colocalization between NLRP3 and LC3 than their wild-type counterparts, and increased IL-1β levels, suggesting that autophagic degradation can reduce the NLRP3 inflammasome response (Houtman et al., 2019). Colocalization between ASC or NLRP3 and LAMP-1 after induction of autophagy was demonstrated in THP-1 cells (Shi et al., 2012). Similarly, IL-1β colocalized with LC3-GFP puncta in immortalized BMDMs (Harris et al., 2011). Deficits in autophagy and clearance are predicted to promote P2X7-mediated inflammation, as the accumulation of lipid droplets within microglia resulted in reduced phagocytosis and increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and Tnfα after the LPS challenge (Marschallinger et al., 2020). In BMDMs, autophagy induction increased IL-1β secretion dependent upon ATG5 (Dupont et al., 2011). However, degradation of inflammasome components through the autophagy pathway is generally expected to reduce the ability of the P2X7 receptor to initiate assembly and activation of the inflammasome in microglial cells. Overall, the balance between the degradation of inflammasome proteins and their upregulation via priming initiated by P2X7 receptor stimulation will influence the consequences of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by the P2X7 receptor on microglial cells (Figure 2).

The P2x7 Receptor Activates The Nlrp3 Inflammasome Via Lysosomal Leakage and Cathepsin B

A particularly important connection linking the P2X7 receptor, lysosomes, and inflammation involves the ability of the P2X7 receptor to cause lysosomal destabilization and subsequent activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome through actions of cathepsin B. In BMDMs, destabilized lysosomes led cathepsin B to activate caspase-1 and cleave IL-1β for release (Chevriaux et al., 2020). In the THP-1 monocytic cell line, S. pneumoniae triggered IL-1β release in an ATP- and cathepsin B-dependent manner (Hoegen et al., 2011). In BV-2 cells, increased leakage of cathepsin B into the cytoplasm following BzATP application was shown using the Magic Red assay, while inhibition of cathepsin B with CA-074 prevented the BzATP-induced cell death (Sekar et al., 2018). In our studies on primary mouse brain microglial cells, the ATP-dependent secretion of IL-1β was reduced by cathepsin B inhibitor CA-074 (Figure 3). While these findings suggest a critical mechanism by which the P2X7 receptor can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome by disrupting lysosomal integrity, additional work is needed to understand how receptor activation leads to lysosomal leakage and whether this is related to its ability to increase lysosomal pH. Experiments to determine whether compromised lysosomes filled with partially degraded waste material are more susceptible to this lysosomal leakage are warranted.

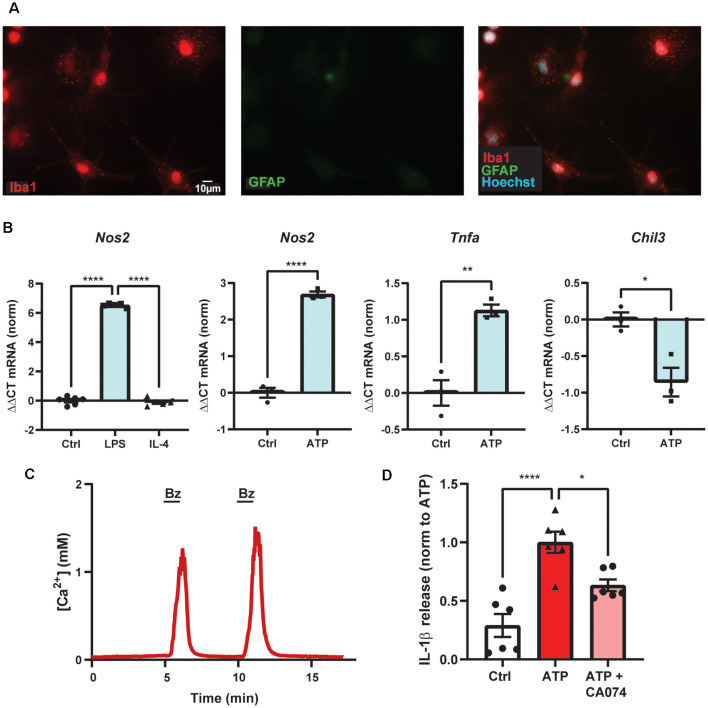

Figure 3.

ATP-dependent IL-1β release from primary microglial cells involves cathepsin B. (A) Purity of primary mouse brain microglia cultures shown with high staining for marker Iba1 (red) and low staining for astrocytic marker GFAP (green). (B) Primary microglial cultures increased expression of Nos2 with 4 h exposure of LPS but not IL-4, as expected for microglial cells polarized into the M1-state (****p < 0.001). Exposure to 1 mM ATP for 4 h increased expression of Nos2 (****p < 0.001) and Tnfa (**p = 0.0042) and decreased expression of Chil3 (*p = 0.014) as compared to control (Ctrl) using quantitative PCR. (C) Evidence of functional P2X7 receptors in primary murine microglial cells indicated by the robust, reversible and repeatable elevation of cytoplasmic calcium when briefly exposed to 100 μM BzATP (line); cells were loaded with Ca2+ indicator fura-2. (D) Release of cytokine IL-1β triggered by exposure to 1 mM ATP for 1 h was reduced by cathepsin B inhibitor CA-074 (10 μM). Microglial cells were primed with 500 ng/ml LPS for 4 h and IL-1β was measured with an ELISA. Approaches as described previously (Lim et al., 2016; Lu et al., 2017; Shao et al., 2020). All work was approved by the University of Pennsylvania IACUC.

Discussion

This review article has presented emerging evidence for the role of the P2X7 receptor in regulating clearance by microglial cells. While the contributions of the P2X7 receptor to immune signaling are well known (Orioli et al., 2017; Adinolfi et al., 2018), its ability to modulate microglial clearance has been less well studied. The ability of the P2X7 receptor to mediate clearance of extracellular and intracellular material occurs at several key steps including the unstimulated receptor acting as a scavenger receptor to phagocytose extracellular material into the microglial cells, the transient receptor stimulation enhancing autophagy through a p-AMPK pathway, and the sustained receptor stimulation elevating lysosomal pH and reducing degradation. Given its role at the crossroads between inflammation and clearance, the ability of the P2X7 receptor to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome following lysosomal leakage is particularly relevant. Also, regulating the availability of inflammasome components by balancing their decrease through autophagy with their increase through priming has special relevance as the P2X7 receptor can itself increase priming. We propose the effects of the P2X7 receptor on clearance pathways in microglia are as significant as its effects on inflammatory signaling. Given that impaired clearance by microglial cells is increasingly implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases (Bachiller et al., 2018), regulation of this clearance by the P2X7 receptor warrants further investigation, and identifies potential points of intervention.

Given the receptor involvement in both clearance and inflammation, several points of relevance emerge. First, the ability of the P2X7 receptor to act as a scavenger receptor offers several new directions for therapeutics (Gu and Wiley, 2018; Fletcher et al., 2019). Because this role requires the absence of an agonist, reducing extracellular ATP levels may provide the double benefit of increasing phagocytosis while reducing inflammation. Overexpression of intracellular binding protein NMMHC IIA reduced P2X7 receptor pore opening, suggesting that shifting the receptor towards this phagocytic role may also reduce its cytotoxic actions.

Second, the relatively high baseline level of pH in the lumen of microglial lysosomes implies that regulation of this pH is a powerful mechanism through which external and internal signals can increase clearance. Given that stimulation of the P2X7 receptor raises lysosomal pH, pH may be lowered by receptor antagonists, or by reducing levels of agonist ATP by increasing enzymatic degradation of extracellular ATP and blocking ATP release through sites like pannexins. Elevation of cAMP and chloride channel function lowered lysosomal pH in microglial cells (Majumdar et al., 2007, 2011), identifying a potential pathway to enhance clearance. Our work indicates the elevation of cAMP and PKA can acidify compromised lysosomes in epithelial cells (Liu et al., 2008), and that stimulation of plasma membrane receptors linked to stimulatory G proteins, such as the dopamine D5 receptor, can lower lysosomal pH and increase the clearance of phagocytosed waste by impaired lysosomes (Guha et al., 2012). Increased clearance can also be induced by stimulating the cystic-fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) chloride channel localized to the lysosomal membrane (Liu et al., 2012), or by acid nanoparticles transported to the lysosomal lumen (Baltazar et al., 2012; Lööv et al., 2015). Antagonists targeted to the P2Y12 receptor were recently shown to lower lysosomal pH and improve clearance; of note, oral delivery of the FDA-approved antagonist ticagrelor (Brilinta) lowered lysosomal pH and was protective in a mouse model of neurodegeneration (Lu et al., 2018, 2019). Whether this drug can cross the blood-brain barrier to reach microglial cells, and whether it will interfere with other microglial functions regulated by the P2Y12 receptor remains to be determined. However, these studies provide a proof of concept for pharmacologic restoration of an acidic lysosomal lumen to enhance clearance.

Third, the ability of the P2X7 receptor to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome following lysosomal leakage of cathepsin B identifies another pathway through which limiting P2X7 receptor stimulation may be of benefit. Given that lysosomal accumulations and inflammatory signaling are both emerging as key steps in aging-dependent neurodegenerations, it would be interesting to see whether leakage of cathepsin B occurs more frequently from compromised lysosomes and whether this becomes a dominant pathway to NLRP3 inflammasome activation in aging microglial cells.

Finally, manipulating the balance between increasing levels of inflammasome components through priming and decreasing levels following their autophagic removal will have a considerable impact on the immune signals emerging from the microglial cell. In this regard, the ability of the P2X7 receptor to trigger both the stage one “priming” of the inflammasome as well as the stage two “activation” phase suggests the P2X7 receptor, and its agonist extracellular ATP, have important consequences for the neuroinflammatory environment. The autophagic degradation of inflammasome components represents an “anti-priming” and emphasizes how the ratio of increasing and decreasing relevant inflammasome proteins can control the gain on the inflammasome responses triggered by the P2X7 receptor, including those activated by lysosomal leakage.

While some therapeutic options of P2X7 receptor inhibition have been explored (Burnstock and Knight, 2018) a deeper understanding of the intersection between the P2X7 receptor, clearance, and inflammation will assist treatments for neurodegenerative diseases in which both problems present. In age-related macular degeneration, where increased accumulations and loss of microglia clearance occur, shifting the P2X7 receptor away from its inflammatory contributions and towards its scavenging role may prove advantageous (Vessey et al., 2017; Fletcher et al., 2019). In Alzheimer’s disease, aged microglia incompletely digest amyloid-beta plaques, increasing local inflammation and pathogenesis (Heneka et al., 2015; Streit et al., 2020). The detrimental effects of Rapamycin to neurons in preclinical models of Alzheimer’s disease after plaque deposition (when clinical diagnosis would likely occur) illustrate the complexity of manipulating a system as tightly regulated as autophagy (Carosi and Sargeant, 2019; Kaeberlein and Galvan, 2019), and stress the need for better understanding and a more nuanced approach. Finding therapeutic modalities that ameliorate autophagic reduction, or ones that can be targeted away from neurons, is crucial. In conditions of trauma such as spinal cord injury that are accompanied by elevated ATP and autophagic dysregulation (Galluzzi et al., 2016; Li et al., 2019), the modulation of microglial activation state has been proposed to enhance repair (Hu et al., 2015; Akhmetzyanova et al., 2019; Kobashi et al., 2020). However, treatment timing is critical, as transient P2X7 receptor stimulation may enhance autophagy and promote M2a microglia, while sustained stimulation can inhibit autophagy and promote proinflammatory M1 microglia (Fabbrizio et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2021). The P2X7 receptor plays a complex role in microglial cells in balancing clearance with inflammatory signals; deeper mechanistic investigations may reveal more specific therapeutic approaches.

The above observations come with multiple caveats, and there remain some inconsistencies. For example, microglial responses differ from those in macrophages on several levels, such as the effect on phagosome-lysosome fusion. As many of the findings come from in vitro experiments, even results obtained from “microglial” cells can vary with the use of cell lines or primary culture. In vitro microglia have been demonstrated to lose transcriptional identity in as little as 8 days after isolation (Bennett et al., 2018). With a cell type so sensitive to extracellular environments, even small changes in the protocol can alter responsiveness. Also, microglial cells in vitro are removed from the challenges of the neurodegenerative environment, and their need to phagocytose waste material, along with the presence of accumulating waste material, will be altered significantly. Closer attention to the effect of the microglial state on responses to the P2X7 receptor is also needed.

In summary, the P2X7 receptor can modulate both inflammatory and clearance pathways in microglial cells. Reducing extracellular ATP levels to shift the receptor from an inflammatory trigger to a scavenger receptor will likely be of benefit in neuroinflammatory diseases associated with increased waste material. Limiting conditions in which receptor stimulation leads to lysosomal leakage will also help reduce NLRP3 inflammasome activation. The P2X7 receptor makes a complex contribution to microglial function, and greater attention in future experiments to attributes such as microglial polarization and lysosomal waste accumulation will help clarify these interactions.

Author Contributions

CM and KC contributed to the design, writing and editing of this manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Wennan Lu, Assraa Hassan Jassim, and Nestor Mas Gomez for constructive conversations and Stuart A. McCaughey for help with the calcium imaging experiments.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by National Eye Institute and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grants R01 EY013434, R01 EY015537 (CM), TL1-TR001880 (KC), and T32-EY007035 (KC).

References

- Adinolfi E., Cirillo M., Woltersdorf R., Falzoni S., Chiozzi P., Pellegatti P., et al. (2010). Trophic activity of a naturally occurring truncated isoform of the P2X7 receptor. FASEB J. 24, 3393–3404. 10.1096/fj.09-153601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adinolfi E., Giuliani A. L., De Marchi E., Pegoraro A., Orioli E., Di Virgilio F. (2018). The P2X7 receptor: a main player in inflammation. Biochem. Pharm. 151, 234–244. 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhmetzyanova E., Kletenkov K., Mukhamedshina Y., Rizvanov A. (2019). Different approaches to modulation of microglia phenotypes after spinal cord injury. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 13:37. 10.3389/fnsys.2019.00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albalawi F., Lu W., Beckel J. M., Lim J. C., McCaughey S. A., Mitchell C. H. (2017). The P2X7 receptor primes IL-1β and the NLRP3 inflammasome in astrocytes exposed to mechanical strain. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 11:227. 10.3389/fncel.2017.00227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allsopp R. C., Dayl S., Bin Dayel A., Schmid R., Evans R. J. (2018). Mapping the allosteric action of antagonists A740003 and A438079 reveals a role for the left flipper in ligand sensitivity at P2X7 receptors. Mol. Pharm. 93, 553–562. 10.1124/mol.117.111021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askew K., Li K., Olmos-Alonso A., Garcia-Moreno F., Liang Y., Richardson P., et al. (2017). Coupled proliferation and apoptosis maintain the rapid turnover of microglia in the adult brain. Cell Rep. 18, 391–405. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachiller S., Jiménez-Ferrer I., Paulus A., Yang Y., Swanberg M., Deierborg T., et al. (2018). Microglia in neurological diseases: a road map to brain-disease dependent-inflammatory response. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 12, 488–488. 10.3389/fncel.2018.00488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltazar G. C., Guha S., Boesze-Battaglia K., Laties A. M., Tyagi P., Kompella U. B., et al. (2012). Acidic nanoparticles restore lysosomal pH and degradative function in compromised ARPE 19 cells. PLoS One 7:e49635. 10.1371/journal.pone.0049635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckel J. M., Gomez N. M., Lu W., Campagno K. E., Nabet B., Albalawi F., et al. (2018). Stimulation of TLR3 triggers release of lysosomal ATP in astrocytes and epithelial cells that requires TRPML1 channels. Sci. Rep. 8:5726. 10.1038/s41598-018-23877-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett F. C., Bennett M. L., Yaqoob F., Mulinyawe S. B., Grant G. A., Hayden Gephart M., et al. (2018). A combination of ontogeny and CNS environment establishes microglial identity. Neuron 98, 1170–1183. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M. L., Bennett F. C., Liddelow S. A., Ajami B., Zamanian J. L., Fernhoff N. B., et al. (2016). New tools for studying microglia in the mouse and human CNS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 113, E1738–E1746. 10.1073/pnas.1525528113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco F., Ceruti S., Colombo A., Fumagalli M., Ferrari D., Pizzirani C., et al. (2006). A role for P2X7 in microglial proliferation. J. Neurochem. 99, 745–758. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biasizzo M., Kopitar-Jerala N. (2020). Interplay between NLRP3 inflammasome and autophagy. Front. Immunol. 11:591803. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.591803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilimoria P. M., Stevens B. (2015). Microglia function during brain development: new insights from animal models. Brain Res. 1617, 7–17. 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas D., Qureshi O. S., Lee W.-Y., Croudace J. E., Mura M., Lammas D. A. (2008). ATP-induced autophagy is associated with rapid killing of intracellular mycobacteria within human monocytes/macrophages. BMC Immunol. 9:35. 10.1186/1471-2172-9-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boche D., Perry V. H., Nicoll J. A. R. (2013). Activation patterns of microglia and their identification in the human brain. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 39, 3–18. 10.1111/nan.12011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootman M. D., Chehab T., Bultynck G., Parys J. B., Rietdorf K. (2018). The regulation of autophagy by calcium signals: do we have a consensus? Cell Calcium 70, 32–46. 10.1016/j.ceca.2017.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst K., Prinz M. (2020). Deciphering the heterogeneity of myeloid cells during neuroinflammation in the single-cell era. Brain Pathol. 30, 1192–1207. 10.1111/bpa.12910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burm S. M., Zuiderwijk-Sick E. A., Weert P. M., Bajramovic J. J. (2016). ATP-induced IL-1β secretion is selectively impaired in microglia as compared to hematopoietic macrophages. Glia 64, 2231–2246. 10.1002/glia.23059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G., Knight G. E. (2018). The potential of P2X7 receptors as a therapeutic target, including inflammation and tumour progression. Purinergic Signal. 14, 1–18. 10.1007/s11302-017-9593-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butovsky O., Jedrychowski M. P., Moore C. S., Cialic R., Lanser A. J., Gabriely G., et al. (2014). Identification of a unique TGF-β-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 131–143. 10.1038/nn.3599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calovi S., Mut-Arbona P., Sperlágh B. (2019). Microglia and the purinergic signaling system. Neuroscience 405, 137–147. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carosi J. M., Sargeant T. J. (2019). Rapamycin and Alzheimer disease: a double-edged sword? Autophagy 15, 1460–1462. 10.1080/15548627.2019.1615823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Zhou C., Xie K., Meng X., Wang Y., Yu Y. (2019). Hydrogen-rich saline alleviated the hyperpathia and microglia activation via autophagy mediated inflammasome inactivation in neuropathic pain rats. Neuroscience 421, 17–30. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.10.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry J. D., Olschowka J. A., O’Banion M. (2014). Neuroinflammation and M2 microglia: the good, the bad and the inflamed. J. Neuroinflammation 11:98. 10.1186/1742-2094-11-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevriaux A., Pilot T., Derangère V., Simonin H., Martine P., Chalmin F., et al. (2020). Cathepsin B is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages, through NLRP3 interaction. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 8:167. 10.3389/fcell.2020.00167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhor V., Le Charpentier T., Lebon S., Oré M.-V., Celador I. L., Josserand J., et al. (2013). Characterization of phenotype markers and neuronotoxic potential of polarised primary microglia in vitro. Brain Behav. Immun. 32, 70–85. 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho M.-H., Cho K., Kang H.-J., Jeon E.-Y., Kim H.-S., Kwon H.-J., et al. (2014). Autophagy in microglia degrades extracellular β-amyloid fibrils and regulates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Autophagy 10, 1761–1775. 10.4161/auto.29647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coddou C., Yan Z., Obsil T., Huidobro-Toro J. P., Stojilkovic S. S. (2011). Activation and regulation of purinergic P2X receptor channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 63, 641–683. 10.1124/pr.110.003129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collo G., Neidhart S., Kawashima E., Kosco-Vilbois M., North R. A., Buell G. (1997). Tissue distribution of the P2X7 receptor. Neuropharmacology 36, 1277–1283. 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00140-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colton C. A. (2009). Heterogeneity of microglial activation in the innate immune response in the brain. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 4, 399–418. 10.1007/s11481-009-9164-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa G., Marques da Silva C., de Abreu Moreira-Souza A. C., Vommaro R. C., Coutinho-Silva R. (2010). Activation of the P2X7 receptor triggers the elimination of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites from infected macrophages. Microbes Infect. 12, 497–504. 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho-Silva R., Correa G., Sater A. A., Ojcius D. M. (2009). The P2X7 receptor and intracellular pathogens: a continuing struggle. Purinergic Signal. 5, 197–204. 10.1007/s11302-009-9130-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui W., Sun C., Ma Y., Wang S., Wang X., Zhang Y. (2020). Inhibition of TLR4 induces M2 microglial polarization and provides neuroprotection via the NLRP3 inflammasome in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 14:444. 10.3389/fnins.2020.00444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Virgilio F. (2020). P2X7 is a cytotoxic receptor….maybe not: implications for cancer. Purinergic Signal. 1–7. [Online ahead of print]. 10.1007/s11302-020-09735-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Virgilio F., Dal Ben D., Sarti A. C., Giuliani A. L., Falzoni S. (2017). The P2X7 receptor in infection and inflammation. Immunity 47, 15–31. 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Virgilio F., Schmalzing G., Markwardt F. (2018). The elusive P2X7 macropore. Trends Cell Biol. 28, 392–404. 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosch M., Gerber J., Jebbawi F., Beldi G. (2018). Mechanisms of ATP release by inflammatory cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:1222. 10.3390/ijms19041222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubyak G. R. (2012). P2X7 receptor regulation of non-classical secretion from immune effector cells. Cell Microbiol. 14, 1697–1706. 10.1111/cmi.12001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont N., Jiang S., Pilli M., Ornatowski W., Bhattacharya D., Deretic V. (2011). Autophagy-based unconventional secretory pathway for extracellular delivery of IL-1β. EMBO J. 30, 4701–4711. 10.1038/emboj.2011.398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbrizio P., Amadio S., Apolloni S., Volonté C. (2017). P2X7 receptor activation modulates autophagy in SOD1–G93A mouse microglia. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 11:249. 10.3389/fncel.2017.00249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn I. P., Stober C. B., Kumararatne D. S., Lammas D. A. (2001). ATP-mediated killing of intracellular mycobacteria by macrophages is a P2X7-dependent process inducing bacterial death by phagosome-lysosome fusion. J. Immunol. 167, 3300–3307. 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari D., Wesselborg S., Bauer M. K. A., Schulze-Osthoff K. (1997). Extracellular ATP activates transcription factor NF-κB through the P2Z purinoreceptor by selectively targeting NF-κB p65 (RelA). J. Cell Biol. 139, 1635–1643. 10.1083/jcb.139.7.1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira S. A., Romero-Ramos M. (2018). Microglia response during Parkinson’s disease: alpha-synuclein intervention. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 12:247. 10.3389/fncel.2018.00247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher E. L., Wang A. Y., Jobling A. I., Rutar M. V., Greferath U., Gu B., et al. (2019). Targeting P2X7 receptors as a means for treating retinal disease. Drug Discov. Today 24, 1598–1605. 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschini A., Capece M., Chiozzi P., Falzoni S., Sanz J. M., Sarti A. C., et al. (2015). The P2X7 receptor directly interacts with the NLRP3 inflammasome scaffold protein. FASEB J. 29, 2450–2461. 10.1096/fj.14-268714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi L., Bravo-San Pedro J. M., Blomgren K., Kroemer G. (2016). Autophagy in acute brain injury. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17, 467–484. 10.1038/nrn.2016.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrmann J., Matsumoto Y., Kreutzberg G. W. (1995). Microglia: intrinsic immuneffector cell of the brain. Brain Res. Rev. 20, 269–287. 10.1016/0165-0173(94)00015-h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genetos D. C., Karin N. J., Geist D. J., Donahue H. J., Duncan R. L. (2011). Purinergic signaling is required for fluid shear stress-induced NF-κB translocation in osteoblasts. Exp. Cell Res. 317, 737–744. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginhoux F., Greter M., Leboeuf M., Nandi S., See P., Gokhan S., et al. (2010). Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science 330, 841–845. 10.1126/science.1194637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez Perdiguero E., Klapproth K., Schulz C., Busch K., Azzoni E., Crozet L., et al. (2015). Tissue-resident macrophages originate from yolk-sac-derived erythro-myeloid progenitors. Nature 518, 547–551. 10.1038/nature13989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu B. J., Duce J. A., Valova V. A., Wong B., Bush A. I., Petrou S., et al. (2012). P2X7 receptor-mediated scavenger activity of mononuclear phagocytes toward non-opsonized particles and apoptotic cells is inhibited by serum glycoproteins but remains active in cerebrospinal fluid. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 17318–17330. 10.1074/jbc.M112.340885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu B. J., Wiley J. S. (2018). P2X7 as a scavenger receptor for innate phagocytosis in the brain: phagocytic role of P2X7 receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 175, 4195–4208. 10.1111/bph.14470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu B. J., Rathsam C., Stokes L., McGeachie A. B., Wiley J. S. (2009). Extracellular ATP dissociates nonmuscle myosin from P2X7 complex: this dissociation regulates P2X7 pore formation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 297, C430–C439. 10.1152/ajpcell.00079.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu B. J., Saunders B. M., Jursik C., Wiley J. S. (2010). The P2X7-nonmuscle myosin membrane complex regulates phagocytosis of nonopsonized particles and bacteria by a pathway attenuated by extracellular ATP. Blood 115, 1621–1631. 10.1182/blood-2009-11-251744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu B. J., Saunders B. M., Petrou S., Wiley J. S. (2011). P2X7 is a scavenger receptor for apoptotic cells in the absence of its ligand, extracellular ATP. J. Immunol. 187, 2365–2375. 10.4049/jimmunol.1101178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guha S., Baltazar G. C., Coffey E. E., Tu L. A., Lim J. C., Beckel J. M., et al. (2013). Lysosomal alkalinization, lipid oxidation and reduced phagosome clearance triggered by activation of the P2X7 receptor. FASEB J. 27, 4500–4509. 10.1096/fj.13-236166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guha S., Baltazar G. C., Tu L. A., Liu J., Lim J. C., Lu W., et al. (2012). Stimulation of the D5 dopamine receptor acidifies the lysosomal pH of retinal pigmented epithelial cells and decreases accumulation of autofluorescent photoreceptor debris. J. Neurochem. 122, 823–833. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07804.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guha S., Liu J., Baltazar G., Laties A. M., Mitchell C. H. (2014). Rescue of compromised lysosomes enhances degradation of photoreceptor outer segments and reduces lipofuscin-like autofluorescence in retinal pigmented epithelial cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 801, 105–111. 10.1007/978-1-4614-3209-8_14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Sun S., Sun Y., Song Q., Zhu J., Song N., et al. (2019). Small molecule-driven NLRP3 inflammation inhibition via interplay between ubiquitination and autophagy: implications for Parkinson disease. Autophagy 15, 1860–1881. 10.1080/15548627.2019.1596481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J., Hartman M., Roche C., Zeng S. G., O%Shea A., Sharp F. A., et al. (2011). Autophagy controls IL-1β secretion by targeting pro-IL-1β for degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 9587–9597. 10.1074/jbc.M110.202911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka M. T., Golenbock D. T., Latz E. (2015). Innate immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Immunol. 16, 229–236. 10.1038/ni.3102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman S., Izzy S., Sen P., Morsett L., El Khoury J. (2018). Microglia in neurodegeneration. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 1359–1369. 10.1038/s41593-018-0242-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindupur S. K., Gonzalez A., Hall M. N. (2015). The opposing actions of target of rapamycin and AMP-activated protein kinase in cell growth control. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7:a019141. 10.1101/cshperspect.a019141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoegen T., Tremel N., Klein M., Angele B., Wagner H., Kirschning C., et al. (2011). The NLRP3 inflammasome contributes to brain injury in pneumococcal meningitis and is activated through ATP-dependent lysosomal cathepsin B release. J. Immunol. 187, 5440–5451. 10.4049/jimmunol.1100790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtman J., Freitag K., Gimber N., Schmoranzer J., Heppner F. L., Jendrach M. (2019). Beclin1-driven autophagy modulates the inflammatory response of microglia via NLRP3. EMBO J. 38:e99430. 10.15252/embj.201899430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Leak R. K., Shi Y., Suenaga J., Gao Y., Zheng P., et al. (2015). Microglial and macrophage polarization-new prospects for brain repair. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 11, 56–64. 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janda E., Boi L., Carta A. R. (2018). Microglial phagocytosis and its regulation: a therapeutic target in Parkinson’s disease? Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11:144. 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janks L., Sharma C. V. R., Egan T. M. (2018). A central role for P2X7 receptors in human microglia. J. Neuroinflammation 15:325. 10.1186/s12974-018-1353-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Zhang Y., Jing F., Long T., Qin G., Zhang D., et al. (2021). P2X7R-mediated autophagic impairment contributes to central sensitization in a chronic migraine model with recurrent nitroglycerin stimulation in mice. J. Neuroinflammation 18:5. 10.1186/s12974-020-02056-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek-Hajek K., Zhang J., Kopp R., Grosche A., Rissiek B., Saul A., et al. (2018). Re-evaluation of neuronal P2X7 expression using novel mouse models and a P2X7-specific nanobody. eLife 7:e36217. 10.7554/eLife.36217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein M., Galvan V. (2019). Rapamycin and Alzheimer’s disease: time for a clinical trial? Sci. Transl. Med. 11:476. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aar4289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlenberg J. M., Lundberg K. C., Kertesy S. B., Qu Y., Dubyak G. R. (2005). Potentiation of caspase-1 activation by the P2X7 receptor is dependent on TLR signals and requires NF-κB-driven protein synthesis. J. Immunol. 175, 7611–7622. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa M., Ninomiya I., Hatakeyama M., Takahashi T., Shimohata T. (2017). Microglia and monocytes/macrophages polarization reveal novel therapeutic mechanism against stroke. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18:2135. 10.3390/ijms18102135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsnelson M. A., Rucker L. G., Russo H. M., Dubyak G. R. (2015). K+ efflux agonists induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation independently of Ca2+ signaling. J. Immunol. 194, 3937–3952. 10.4049/jimmunol.1402658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai A., Uchiyama H., Takano S., Nakamura N., Ohkuma S. (2007). Autophagosome-lysosome fusion depends on the pH in acidic compartments in CHO cells. Autophagy 3, 154–157. 10.4161/auto.3634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierdorf K., Prinz M. (2017). Microglia in steady state. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 3201–3209. 10.1172/JCI90602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Kundu M., Viollet B., Guan K. L. (2011). AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 132–141. 10.1038/ncb2152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.-Y., Paton J. C., Briles D. E., Rhee D.-K., Pyo S. (2015). Streptococcus pneumoniae induces pyroptosis through the regulation of autophagy in murine microglia. Oncotarget 6, 44161–44178. 10.18632/oncotarget.6592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Chung H., Ngoc Mai H., Nam Y., Shin S. J., Park Y. H., et al. (2020). Low-dose Ionizing radiation modulates microglia phenotypes in the models of Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:4532. 10.3390/ijms21124532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky D. J., Abdel-Aziz A. K., Abdelfatah S., Abdellatif M., Abdoli A., Abel S., et al. (2021). Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (4th edition). Autophagy 1–382. [Online ahead of print]. 10.1080/15548627.2020.1797280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobashi S., Terashima T., Katagi M., Nakae Y., Okano J., Suzuki Y., et al. (2020). Transplantation of M2-deviated microglia promotes recovery of motor function after spinal cord injury in mice. Mol. Ther. 28, 254–265. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofler J., Wiley C. A. (2011). Microglia: key innate immune cells of the brain. Toxicol. Pathol. 39, 103–114. 10.1177/0192623310387619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp R., Krautloher A., Ramírez-Fernández A., Nicke A. (2019). P2X7 interactions and signaling - making head or tail of it. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 12:183. 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korcok J., Raimundo L. N., Ke H. Z., Sims S. M., Dixon S. J. (2004). Extracellular nucleotides act through P2X7 receptors to activate NF-κB in osteoclasts. J. Bone Miner. Res. 19, 642–651. 10.1359/JBMR.040108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowal K., Silver R., Sławińska E., Bielecki M., Chyczewski L., Kowal-Bielecka O. (2011). CD163 and its role in inflammation. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 49, 365–374. 10.5603/fhc.2011.0052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusner D. J., Adams J. (2000). ATP-induced killing of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis within human macrophages requires phospholipase D. J. Immunol. 164, 379–388. 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusner D. J., Barton J. A. (2001). ATP stimulates human macrophages to kill intracellular virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis via calcium-dependent phagosome-lysosome fusion. J. Immunol. 167, 3308–3315. 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M., Yao H., Shah S. Z. A., Wu W., Wang D., Zhao Y., et al. (2018). The NLRP3-caspase 1 inflammasome negatively regulates autophagy via TLR4-TRIF in prion peptide-infected microglia. Front. Aging Neurosci. 10:116. 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]