Abstract

Corneal endothelial diseases are leading indications for corneal transplantations. With significant advancement in medical science and surgical techniques, corneal transplant surgeries are now increasingly effective at restoring vision in patients with corneal diseases. In the last 15 years, the introduction of endothelial keratoplasty (EK) procedures, where diseased corneal endothelium (CE) are selectively replaced, has significantly transformed the field of corneal transplantation. Compared to traditional penetrating keratoplasty, EK procedures, namely Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) and Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK), offer faster visual recovery, lower immunological rejection rates, and improved graft survival. Although these modern techniques can achieve high success, there are fundamental impediments to conventional transplantations. A lack of suitable donor corneas worldwide restricts the number of transplants that can be performed. Other barriers include the need for specialized expertise, high cost, and risks of graft rejection or failure. Research is underway to develop alternative treatments for corneal endothelial diseases, which are less dependent on the availability of allogeneic tissues – regenerative medicine and cell-based therapies. In this review, an overview of past and present transplantation procedures used to treat corneal endothelial diseases are described. Potential novel therapies that may be translated into clinical practice will also be presented.

Keywords: cornea, corneal transplantation, keratoplasty, eye (tissue) banking, cell therapy, corneal endothelium, regenerative medicine, bullous keratopathy, Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy, Ocular surface, Inflammation, Stem Cells, Angiogenesis, Infection, Choroid, Imaging, Genetics, Treatment Lasers

INTRODUCTION

A healthy corneal endothelium (CE) is essential in supporting an ideal level of corneal hydration (approximately 78% aqueous). This maintains an ideal spacing of stromal collagen lamellae, which is important in keeping the cornea transparent.1 2 In the early neonatal period, the human corneal endothelial cell density (ECD) is estimated to be around 6000 cells/mm2.3 4 Subsequently, ECD falls to 3000–3500 cells/mm2 by early childhood as a result of normal growth in corneal size and concurrent cellular attrition.4 5 Thereafter, there is a continuing loss in ECD of approximately 0.6% each year, so that the average ECD at 85 years of age is approximately 2300 cells/mm2.4 6 7 This physiological decline in ECD throughout life does not normally affect the normal structure and function of the cornea.

An accelerated corneal endothelial cells (CECs) attrition above the natural decline in ECD can be caused by specific pathological conditions including Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD) or various insults to the CE (eg, intraocular surgeries, anterior segment laser treatments, intraocular inflammation, infections, direct physical trauma).4–9 A loss in ECD below a pathological level (typically <500–600 cells/mm2) can compromise the capacity of the CE to maintain corneal hydration.8–11 When this occurs, the cornea loses its transparency from corneal oedema resulting in visual impairment.

However, human CECs are unable to spontaneously divide and regenerate under physiological in vivo conditions.12–13 In the early gestational period, human CECs are believed to be locked in the quiescent G1 phase of the cell cycle.14–15 This has been ascribed to various influences including cellular contact inhibition,16–17 the presence of inhibitors of mitosis (eg, transforming growth factor-β2),16– 19 or an absence of active stimuli from growth factors.17 18 Thus, the restoration of physiological function of the CE in diseased states can only depend on one of the three ways: (a) a replacement with an external source of healthy CECs, (b) the repair of impaired CECs or (c) the redistribution of remaining functional CECs to replace damaged or lost CECs.9 The current approach for treating corneal endothelial failure predominantly relies on the replenishment by an exogenous source of healthy CECs through various techniques of corneal transplantations.9 However, being dependent on a supply of transplantable grade donor corneas, the limited availability of such suitable donor tissues restricts the number of transplants that can be performed worldwide.20 Corneal transplantations can also be complicated by risks of allogeneic graft rejection and failure.21– 23 Consequently, there is a drive in search for alternative therapies.9 These include cell-based approaches as a scalable source of human CECs or regenerative medicine, where damaged cells are repaired or existing functional CECs are made to redistribute to replace damaged or lost cells.9 24 These form the basis of potential future therapies for corneal endothelial replacement. In this review, we aim to illustrate the evolution of corneal endothelial replacement from past practices of full thickness penetrating keratoplasties, to present advanced endothelial keratoplasty (EK) techniques, to potential future novel therapies for corneal endothelial diseases that may be translated into clinical practice.

CORNEAL ENDOTHELIAL REPLACEMENT: THE EARLY YEARS OF KERATOPLASTY

Since Eduard Zirms’ introduction of penetrating keratoplasty (PK) surgery in 1905, it has been the predominant technique to restore visual loss from various diseases of the cornea.25 In PK, all corneal layers of the recipient are replaced by a donor corneal graft, which is sutured to the recipient.9 It is an effective procedure in reversing corneal blindness.26 Thus, despite the redundant replacement of healthy anterior corneal tissues in PK with its known intra-operative and postoperative complications, this surgical procedure was deemed as the standard of care for treating corneal endothelial diseases throughout the 20th century.26–27

In the mid-1950s, Charles Tillet performed the first posterior lamellar keratoplasty (PLK) for corneal oedema, where he sutured a posterior corneal button to a diseased host.28 This marked the introduction of posterior lamellar or EK techniques, where diseased CE is selectively replaced, avoiding full-thickness PK procedures.9 In the original case report, the PLK procedure successfully reversed the patient’s corneal oedema and the cornea remained clear after 1 year.28 However, the patient’s vision was not restored due to postoperative high intraocular pressures caused by trapped air behind the iris.28 Shortly after, Jose Barraquer described a similar technique using a microkeratome-created laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) flap.29 This was followed by the trephination of the recipient’s posterior lamellae comprising stromal tissue, Descemet’s membrane (DM) and diseased CE. A donor endothelial graft was then fixed with sutures. The LASIK flap was subsequently repositioned and resutured. Nevertheless, although some success was achieved in replacing the diseased CE, these early PLK techniques were not widely adopted. This was partly due to the lack of appropriate surgical instruments needed to create a thin donor endothelial graft, which made these techniques difficult to perform. Complications and poor outcomes were also encountered as a result of a limited knowledge of endothelial cell physiology. Moreover, the need for suturing resulted in corneal astigmatism similar to PK. As a result, there were no significant developments of Tillet’s and Barraquer’s described PLK techniques for most of the second half of the 20th century.30

It was only until the late 1990s, when Gerrit Melles proposed an intrastromal approach for PLK that advancement in EK techniques rapidly followed.9 31 32 In Melles’ PLK technique, a pocket was created via a corneoscleral incision to hold a donor endothelial graft without sutures. The graft was then transplanted through a limbal wound and was attached to the recipient’s posterior corneal surface by means of an injected air bubble. Mark Terry subsequently adopted and modified Melles’ PLK procedure, which was renamed as deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty (DLEK).33 34 Nevertheless, these PLK and DLEK techniques introduced were not universally adopted due to the high surgical demands of dissecting the host diseased cornea.30 The difficulties of obtaining a smooth recipient–donor interface by hand-dissection resulted in a compromise in best-achieved visual acuities and visual quality.35– 37

ENDOTHELIAL KERATOPLASTY: CURRENT APPROACHES

Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK) and Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK)

In 2004, Melles further simplified his posterior lamellar approach by only selectively removing DM and CE from recipient’s corneas, without the need to dissect stroma.38 This is known as ‘descemetorhexis’. A pre-cut endothelial graft is subsequently inserted into the recipient’s eye via a small corneal or scleral surgical wound and attached to the host cornea with an air or gas bubble.9 Using an internal approach and for preserving the host, posterior stroma creates a smooth surface on which the endothelial graft can be attached. This technique is known as Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK). Later, Gorovoy described the use of an automated microkeratome in the dissection of the donor graft to improve the graft–host interface. He called this procedure Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK).39 Both DSEK and DSAEK techniques have since been widely adopted and performed worldwide.40

Since the introduction of these advanced EK techniques, a shift in the surgical management of corneal endothelial failure, away from full thickness PK, has been observed.41 Indeed, these EK techniques where diseased CE is selectively replaced have significantly transformed the field of corneal transplantation in treating corneal endothelial diseases over the past decade. Compared to PK, DSAEK procedures offer several clear advantages.22–42 Being minimally invasive, DSAEK avoids ‘open-sky’ situations following full thickness trephination of PKs and the associated sight-threatening risks of intraoperative suprachoroidal haemorrhage.9–43 In contrast to surgically induced weaknesses at the graft–host junctions seen in PK corneas, the biomechanical strengths of corneas that had undergone DSAEK are often maintained.44 This reduces the risk of devastating open globe injuries in the event of physical trauma.9 In addition to avoiding full-thickness transplantation, corneal sutures are often not required in DSAEK. There are thus lower risks of suture-related complications in DSAEKs including infectious keratitis and postoperative corneal astigmatism, the latter attributed to more rapid visual rehabilitation.9 45– 47 Unlike PK, as the corneal profile is relatively well preserved in DSAEK, when concurrent cataract surgery is required, more accurate intraocular lens (IOL) power calculations can be achieved.9–48 Overall, the risks of allogeneic graft rejection rates are also observed to be lower in DSAEK grafts compared to PK.22 23

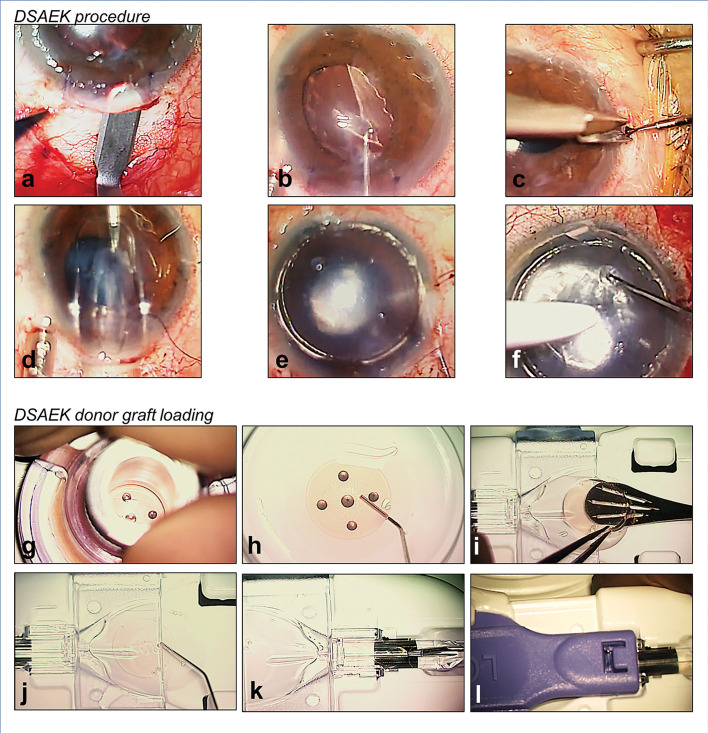

Consequently, with its clear advantages, the DSAEK technique has become increasingly popular among corneal surgeons. In many institutions worldwide, DSAEK has now been adopted as the predominant procedure for reversing corneal blindness caused by endothelial dysfunction.40 49 50 Since the introduction of DSEK/DSAEK surgeries, there have been noticeable developments in their techniques with the aims of improving postoperative outcomes.9 One example of such advancements lies in graft insertion techniques. The first DSEK grafts were inserted into the eye using a 60/40 ‘taco-folding’ technique with the help of surgical forceps.30 Following insertion, grafts were then unfolded in the anterior chamber. However, significant ECD losses of up to 40% have been reported with this forceps folding technique.51 Since then, various innovative techniques to insert endothelial grafts have been proposed.52 These insertion methods have been shown to be less damaging to the CE.52 54 Such techniques include the use of IOL cartridges, sheets glide, or customised graft insertion devices to assist the surgeon in the intraocular transfer of DSAEK grafts.52–57 Some examples of customised graft insertion devices are the Endosaver (Ocular Systems, North Carolina USA),56 the Busin glide (Asico, Illinois, USA),53 the Neusidl Corneal Inserter (Fischer Surgical Missouri, USA),57 and the EndoGlide (Network Medical Products, North Yorkshire, UK).9–54 By maintaining the donor graft in an ‘endothelium-down’ orientation during insertion, these customised insertion devices aim to avoid unnecessary graft manipulation and damage to its CE when the graft is unfolded within the eye.53–56 Unlike the ‘taco-folding’ technique, these devices also protect the DSAEK graft from endothelium-to-endothelium touch, and hence reducing the unnecessary loss of CECs.54 There are many variations in performing DSAEK. Figure 1 shows the authors’ preferred DSAEK technique using the EndoGlide.

Figure 1.

Authors’ preferred surgical technique of Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) with the EndoGlide (Network Medical Products, Yorkshire, UK). (A) 4.5 mm scleral-tunnelled surgical wound; (B) descemetorhexis; (C) inferior peripheral iridectomy; (D) pre-cut DSAEK lenticule inserted into the anterior chamber via a pull-through technique; (E) injection of air for graft attachment; (F) opening of venting incisions to release fluid from the graft–host interface; (G) trephination of pre-cut graft; (H) fluid separation of DSAEK lenticule from anterior stromal cap; (I) DSAEK lenticule transferred to the EndoGlide; (J) ocular viscoelastic device coating to protect donor endothelial cells; (K) DSAEK lenticule is pulled into the EndoGlide using a customised micro-forceps; and (L) clip secured creating a ‘closed system’ during DSAEK graft insertion.

Research has also been focussed on evaluating the effects of reducing the thickness of the transplanted DSAEK grafts. Compared to thicker grafts, studies have reported improved visual outcomes when ultra-thin DSAEK grafts (<100 μm) are transplanted.58 59 Several approaches have been introduced to reliably cut ultra-thin DSAEK grafts.9 One example is the ‘double-pass technique’ using a microkeratome, which involves a first 300 μm debulking cut followed by a second refinement cut.60 61 Other approaches to obtain ultra-thin DSAEK grafts include preconditioning donor tissues with airflow dehydration prior to the microkeratome cut62 or graft dissection with the aid of a femtosecond laser.63

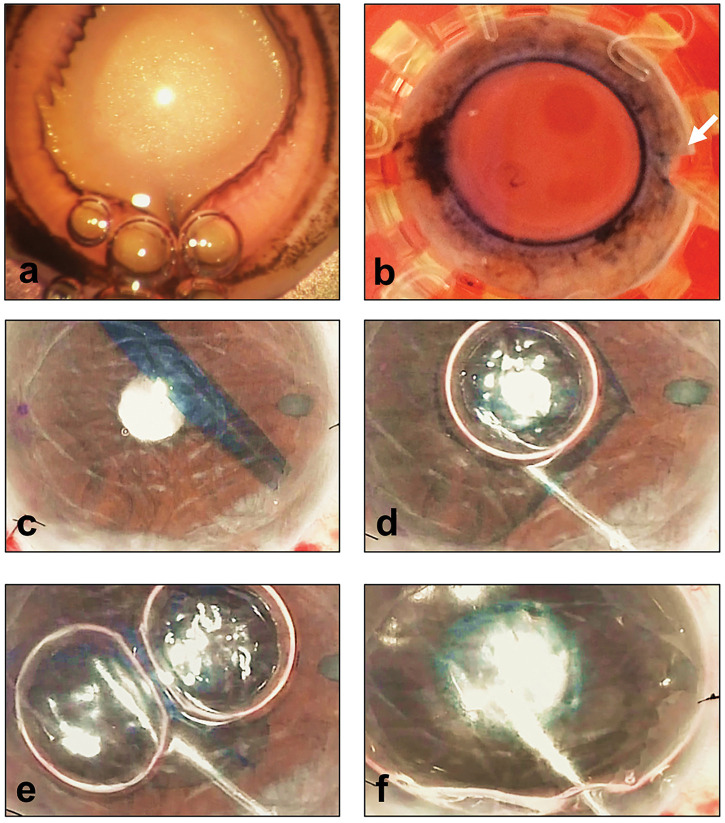

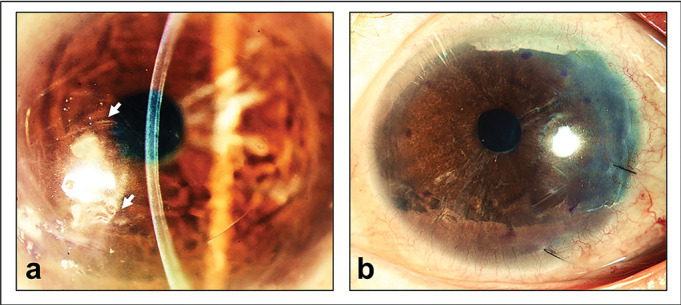

In spite of the considerable advancements in surgical techniques where good predictable results can be achieved, DSAEK does have its limitations.9 Undesirable hypermetropic outcomes can be caused by the presence of a stromal layer in transplanted DSAEK grafts. Visual quality may also be affected at the graft–host interface.64 65 The discrepancies in curvatures between recipient’s posterior corneal surface and DSAEK donor lenticule may lead to folds as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Optical quality degradation following Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK). (A) Patient who received a DSAEK graft showing folds visible in the interface (arrows) between graft and recipient stroma resulting in visual symptoms; (B) the same patient who had a DSAEK graft exchanged with a Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) graft showing the resolution of folds and corresponding improvement in optical quality.

Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK)

More recently, a significant development in EK surgery is the transplantation of donor DM with its endothelium without stroma. In 2006, Michael Tappin reported the use of purpose-made cannulas to transfer 7.5 mm donor endothelial discs with DM which were made to attach to recipient bare corneal stroma using an injected air bubble.66 Corneal oedema was reversed in all three cases reported using this procedure known as true endothelial cell (Tencell) transplantation. Around the same time, Melles introduced DMEK, a procedure which later became widely adopted by corneal surgeons worldwide.21 40 67 68 Like Tencell, a DMEK graft consisting of donor DM and endothelium is transplanted.9 Similar to DSAEK, air or gas tamponade was used to keep the DMEK graft adhered to the posterior corneal surface of the recipient (figure 2). By only replacing unhealthy corneal tissues, DMEK is an anatomically and functionally more accurate replacement of the diseased CE.9 68 Compared to DSAEK, DMEK has been reported to offer faster visual recovery and improved outcomes.69– 74 Reports have also indicated lower rates of graft rejection following DMEK,23 75 and as such, with reduced need for steroids, a lower risk of glaucoma.76 Although endothelial cell loss following DMEK surgery has been reported to be higher than DSAEK in the initial follow-up period,71 77 78 studies comparing DMEK to DSAEK with longer follow-up suggest that ECD loss is similar or better in DMEK.79 Nevertheless, in spite of these advantages of performing DMEK, corneal surgeons have been reluctant to take on DMEK as the primary surgical technique for the management of corneal endothelial failure.40 41 This trend is ascribed to the challenges encountered in DMEK surgery.9 Unlike DSAEK, a different set of skills with steeper learning curve are needed by the surgeon at each step of DMEK procedures. In DMEK, there are risks of tissue damage and wastage in donor graft harvesting, challenges in graft unfolding within the eye following graft insertion, and higher rates of complications such as graft detachments and iatrogenic failure.9 68

Donor graft harvesting

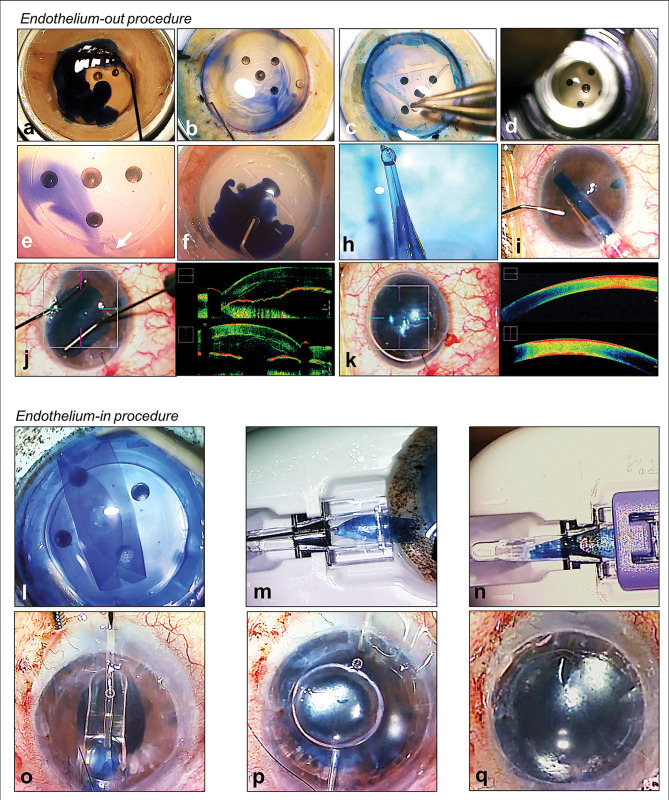

As the DM is approximately 10 μm thin and highly friable,80 the success of DMEK graft donor preparation depends on consistent techniques that allow grafts to be harvested without damage and tissue wastage.9 Figure 3 illustrates DMEK graft harvesting by means of a ‘submerged cornea using backgrounds away’ (SCUBA) technique.81 Through graft harvesting under fluid, it allows easier tissue handling as surface tension on the free DM is negated.9 The initial step involves scoring and detaching the donor DM from the peripheral CE. This is followed by peeling of the DM prior to central trephination. During graft preparation, the visibility of the thin transparent DMEK graft can be enhanced using vital dyes such as Visionblue (D.O.R.C., Zuidland, The Netherlands). Other dyes, which give longer-lasting stains, such as Membrane Blue Dual (D.O.R.C., Zuidland, The Netherlands) can be applied prior to graft insertion to assist the surgeon in graft visualisation and orientation within the eye.82 Nevertheless, the exposure of the DMEK grafts to these vital dyes should be restricted as studies have reported time-dependent toxic effects of these dyes to the CE.83

Figure 3.

Authors’ preferred surgical techniques of Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK). (A–K) Donor preparation using submerged cornea using backgrounds away (SCUBA) technique and ‘endothelium-out’ surgical technique of DMEK. (A) Visionblue (D.O.R.C., Zuidland, The Netherlands) to enhance Descemet’s membrane (DM) visualisation; (B) corneal tissue scored in the periphery; (C) DM is peeled from periphery; (D) DMEK graft is trephined; (E) arrow showing surgically cut orientation mark (asymmetrical triangle); (F) Membrane Blue Dual (D.O.R.C., Zuidland, The Netherlands) applied to DMEK graft; (H) loading of graft into glass-injector; (I) intracameral injection of DMEK graft via a corneal surgical wound; (J) graft is unfolded using controlled taps over host cornea; (K) injection of air/gas for graft attachment; (L–Q) Surgical technique of ‘endothelium-in’ DMEK using a DMEK EndoGlide (Network Medical Products, Yorkshire, UK). (L) creating an ‘endothelium-in’ graft trifold; (M) donor loading into the DMEK EndoGlide using a pull-through technique; (N) clip secured creating a ‘closed system’ during DMEK graft insertion; (O) graft inserted into the anterior chamber by a pull-through technique; (P) air is injected whilst holding the donor to maintain orientation; (Q) intracameral full air/gas fill for graft attachment.

To prevent iatrogenic graft failure caused by an inadvertent ‘up-side-down’ graft, intraoperative orientation of the DMEK graft is essential.84 However, graft orientation can often be difficult following the intracameral transfer of the graft. In addition to the use of vital dyes, surgeons have also used other strategies such as asymmetrical markers created on harvested grafts to aid graft orientation.9 Some examples include the use of S-stamps85 or peripheral scalene triangular incisions.86

Other approaches have also been introduced to minimise the failure of graft preparation often caused by inadvertent tissue damage. For example, some investigators have employed the use of air or fluid to detach and harvest the donor DM from the posterior stroma87 88 (figure 4A). There is also a growing trend in the use of DMEK grafts pre-stripped in the eye bank89– 91 (figure 4B). By eliminating the need of the surgeon to prepare the donor graft, the use of pre-stripped DMEK grafts can reduce the learning curve of DMEK surgery; it allows the surgeon to concentrate on patient preparation and DMEK graft insertion, unscrolling and attachment. Furthermore, using pre-stripped DMEK grafts can potentially reduce surgical time, tissue wastage, cost and logistic requirements of DMEK graft harvesting performed by the surgeon.91– 93 Although some investigators have suggested trends of reduced cell viability with pre-stripped DMEK grafts especially when stored in preservation media for a longer duration,94 most larger series investigating outcomes of pre-stripped DMEK have reported comparable results in conventional surgeon-prepared DMEK.90 95– 97

Figure 4.

Strategies to improve success of Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK). (A) Air used to separate and detach Descemet’s membrane from stroma for donor harvest; (B) eye bank pre-stripped DMEK graft; note the orientation S-stamp and mark on scleral rim indicating the unstripped area of the graft (arrow); (C–F) example of a tight scroll and use of air bubbles to assist the surgeon in opening up the graft (D, E) before full air tamponade (F).

Donor graft insertion and unfolding

Upon separation from the posterior stroma, a free-floating DM has a natural tendency to adopt a scrolled-configuration with its endothelium on its outer surface.98 This consistent ‘endothelium-out’ directional scrolling of DMEK graft tissues has been attributed to the elastin distribution within the DM—anterior dense band of elastin in the DM gives rise to a greater elasticity in its anterior compared to its posterior surface.98 It makes intracameral graft unfolding one of the most technically demanding stages in DMEK surgery. In particular, scrolls formed are often tighter in younger donors, and thus unfolding is thought to be even more challenging in these circumstances.99– 101

Similar to DSAEK, a range of devices have been introduced to assist the surgeon in DMEK graft insertion. These devices shield the graft from endothelial damage when passing through the surgical wound. Examples of such devices include glass injections102 103 and the use of IOL cartridges.104 105 In the vast majority of techniques used in published studies, the DMEK graft is loaded such that its endothelium is on the outside (‘endothelium-out’) (figure 3A–K). In these ‘endothelium-out’ techniques, there is inevitable contact between graft endothelium and the inner wall of the insertion device which may potentially lead to ECD loss. There is also some evidence that plastic graft injectors correlated with higher postoperative graft detachment rates, compared to glass injectors.106 107 This observation has been explained by more variable ECD loss with plastic materials and intraoperative changes in the nature of DMEK grafts during insertion and unfolding, thought to be caused by electrostatic forces generated from plastic materials.106 However, not all studies have found this.108 Furthermore, in all ‘endothelium-out’ techniques, a scroll of DMEK graft is inserted into the eye in its entirety, leaving the surgeon to unscroll the free-floating graft in the anterior chamber. This can often be challenging, unpredictable, and time consuming.109 Compared to DSAEK, different surgical skills with steeper learning curve are required by the surgeon.110 The surgeon must learn various techniques to unfold a DMEK graft within the anterior chamber68 111 112 (figures 3A–K). Such techniques include methodological approaches to unfold double-scrolled grafts through a series of controlled taps on the corneal surface, the use of intracameral water currents to shift and orientate the graft, or air bubbles to assist the surgeon in opening tight scrolls.111 112 As these techniques of orientating and unscrolling a free-floating DMEK graft are reliant on normal anterior segment anatomies, structural abnormalities (eg, iris defects, aphakia, previous vitrectomies) can significantly increase the surgical complexity of the surgery. In cases such as tight graft scrolls or a very deep anterior chamber, the graft unfolding can also be technically challenging113 (figure 4C–F).

Recent publications have introduced ‘endothelium-in’ graft insertion techniques for DMEK surgery.114– 117 After harvesting, the DMEK graft is folded often in a tri-fold, with its endothelium on its inner surface. This prevents the graft from naturally scrolling with its endothelium on the outer surface (figure 3L–Q). Such ‘endothelium-in’ techniques are thought to have the advantage of reducing donor CEC loss from inadvertent contact of graft endothelium on the luminal walls of insertion devices. Furthermore, in ‘endothelium-in’ techniques, the DMEK graft is inserted into the anterior chamber in the correct orientation with the endothelium facing downwards. Following insertion in an ‘endothelium-in’ configuration, the DMEK graft starts to unfold to adopt its natural ‘endothelium-out’ scroll, essentially ‘assisting’ the surgeon in graft unfolding. As such, the reliance on normal anterior segment structures (eg, intact iris diaphragm), important in ‘endothelium-out’ techniques, is circumvented in ‘endothelium-in’ techniques. These features of ‘endothelium-in’ techniques thus minimise the surgical challenges of graft orientation and unfolding of a free-floating scrolled graft within the eye. This makes DMEK surgery more controlled and predictable, especially in complex eyes with abnormal anatomies. ‘Endothelium-in’ techniques can be inserted into the eyes by (a) direct injection into the anterior chamber or (b) pulled into the eye using various ‘pull-through devices’ or IOL cartridges. Various ‘pull-through devices’ have been designed to mimic DSAEK procedures, which are familiar to many corneal surgeons.114 An example of a ‘pull-through endothelium-in’ device is the DMEK EndoGlide (Network Medical Products, North Yorkshire, UK)9 (figure 3L–Q).

Since the introduction of DMEK surgery, variants of this surgical technique have been described. These include hemi-DMEK or quarter-DMEK118 119 and pre-Descemet’s endothelial keratoplasty (PDEK).120 Hemi-DMEK or quarter-DMEK surgeries differ from standard DMEK only by the sizes and shapes of grafts transplanted into recipients.118 119 Compared to standard DMEK where one donor is used for one recipient, these techniques allow one donor to be used for two (hemi-DMEK) or four (quarter-DMEK) recipients, increasing the availability of donor endothelial tissues to more patients. Although the visual outcomes of hemi-DMEK and quarter-DMEK have been reported to be comparable to standard DMEK in published small case series, there appears to be a larger drop in ECDs in the initial postoperative period in these newer techniques.118 119 Larger studies with longer duration of follow-up comparing the survival outcomes of hemi-DMEK or quarter-DMEK to standard DMEK are required.

In 2014, the PDEK technique was introduced as a modification of DMEK.120 By including a pre-Descemet’s layer, a PDEK graft is prevented from forming a natural scroll, unlike DMEK grafts. Thus, authors proposed that PDEK offers better control and reduces the need for intraocular manipulation to unfold a scrolled graft.120 A PDEK graft is harvested by intrastromal air injection to obtain a Type 1 big bubble which cleaves a plane between the pre-Descemet’s layer and the rest of the corneal stroma. However, the ability to perform PDEK surgery is dependent on the reliability of achieving a Type 1 big bubble.9 Moreover, the size of the graft is also limited to approximately 7–8 mm, the maximum diameter of a big bubble. It is worth noting that some consider the pre-Descemet’s layer as an artificial formation of a stromal layer caused by pneumodissection, rather than a distinct anatomical structure.121

FUTURE OF ENDOTHELIAL REPLACEMENT

Conventional EK surgeries, the current standard of care for treating endothelial dysfunction, are increasingly successful in restoring vision.26 27 122– 125 (table 1). Nonetheless, the number of transplant surgeries that can be performed is restricted by the availability of suitable donor tissues. In a 2016 report, it was estimated that only 1.5% of the worldwide demands for corneal transplantations were being fulfilled.20 Furthermore, about a third of donor corneal tissues harvested were reported to be not suitable for transplant surgeries due to low ECD or abnormal donor infectious screen.20 Corneal transplantations are also associated with the requirements of specialised surgical expertise, high costs and the long-term risks of allogeneic graft rejection and failure.

Table 1.

Summary of corneal transplantation techniques for the treatment of endothelial diseases and their reported outcomes (selected studies)

| Corneal endothelial transplantation technique | Year introduced | Visual acuities (≤ 12 months) |

Graft detachment/rebubbling rates | Immune rejection rate (%) | Percentage endothelial cell loss at 1 year/5 years | Graft survival rates (5 year) |

IOP elevation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penetrating keratoplasty | 1905 | 4.6–19% ≥20/2523 47 | NA | 5–17%23 204 205 | 35.8–45%23 36/61–7%22 206 | 44–90%22 23 207 208 | 12–60%23 209– 212 |

| Modified posterior lamellar keratoplasty (PLK)/deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty (DLEK) | 1998 | 0–28.6% ≥20/2532– 34 37 | 8.8%36 | 4.4%36 | 26–43%36 213/62%37 | 72%37 | 13.2%31 |

| Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK)/Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) | 2004 | 15.3–72% ≥20/2523 47 60 | 0.7–15.6%23 36 | 7.3–12%23 216 | 15–36%23 36 54 60 217/47–55%22 218 | 62–96%22 23 123 218–

220

|

1.7–37%23 212 216 221– 223 |

| Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) | 2006 | 32–85% ≥20/2523 224 | 0.2–74%23 77 224–226 | 0.7–5%23 205 218 227 | 19–40%23 227 228/39–48%79 218 | 93–99%23 218 226 229 | 2.8–12%23 230 231 |

IOP, intraocular pressure.

With these limitations of corneal transplantations, research is thus focused on developing alternative approaches to replace CECs in corneal endothelial diseases.24 These approaches include cell-based therapies and regenerative medicine.9 Cell-based therapies use the in vitro cultivation and propagation of CECs as an alternative scalable exogenous source of cells. In regenerative medicine, damaged cells are repaired or existing functional CECs are redistributed to replace damaged or lost cells.9

Cell-based approaches to endothelial replacement

Concepts of cell-based therapies

Cell-based therapies encompass the in vitro cultivation of primary native human CECs population from cadaveric donor corneas.126– 128 With the propagation of functional CECs, the scalability of human CECs through cell cultures from a single donor cornea can yield sufficient CECs for the treatment of multiple patients; this is unlike conventional corneal transplantations where one donor is, in most situations, limited to the treatment of just one or, at best, a small number of recipients.24

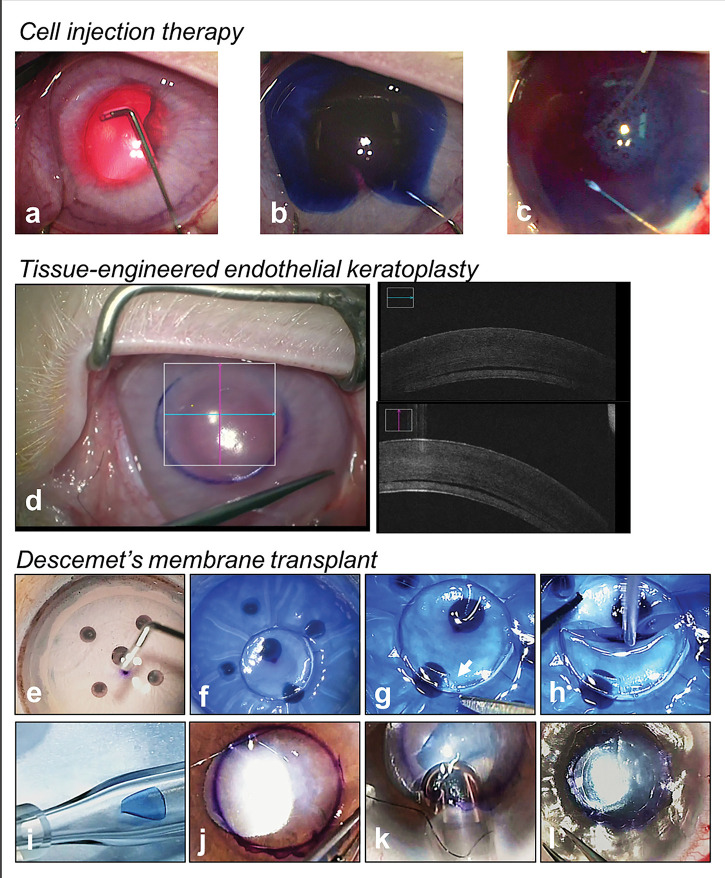

In cell-based therapies, cultured CECs can subsequently be transferred to recipients’ diseased corneas via either (1) cell-injection or (2) as a tissue-engineered construct.9 24 In cell-injection approach, cultured CECs are delivered by direct intracameral injection of the cells into the recipient. The recipient is then required to posture in a face-down position for 2–3 hours. This enables the CECs to settle and attach to the cornea of the recipient.24 129–136 (figure 5A–C) Some investigators have also described the role of ferromagnetic adherence using iron-endocytosed CECs,130 superparamagnetic microspheres,137 or magnetic nanoparticles,138 to aid in the distribution and attachment of CECs. Alternatively, cultured CECs may also be used to produce tissue-engineered endothelial constructs.134 139 (figure 5d) Engineered corneal endothelial grafts are fashioned by high-density seeding of expanded CECs onto thin biological or synthetic scaffolds, and stabilised before transplantation into the eye. Reported examples of scaffolds studied included DM,140– 150 amniotic membranes,151 collagen matrix,152 human corneal stromal discs,134 139 153 154 gelatin hydrogel discs155 156 and chitosan-based membranes.157 These tissue-engineered approaches allow the cells to be transplanted into the eye, similar to current EK techniques.24 134 139

Figure 5.

Novel therapies for the treatment of corneal endothelial diseases. (A–C) Cell injection therapy performed in a rabbit model of bullous keratopathy; silicone-tipped cannula is used to remove native corneal endothelial cells guided by trypan blue (A, B) followed by injection of cultured human corneal endothelial cells (C); (D) tissue-engineered endothelial keratoplasty performed in a rabbit model; (E–L) technique of the Descemet’s membrane transplant (DMT); (E) removal of donor corneal endothelial cells by Descemet’s membrane (DM) scrapping with a silicone tip cannula (SP-125053, ASICO, USA); (F) trephination of DMT graft; note posterior surface of graft is stained blue with Visionblue (D.O.R.C, Zuidland, The Netherlands), showing its aceullarity; (G) orientation mark created (asymmetrical scalene triangle); (H) acellular DM disc is the loaded into a glass injector; (J) surgical marking on host cornea (4–5 mm) to indicate the central diseased area of DM stripping; (K) intracameral injection of DMT graft via a corneal surgical wound; (L) intracameral full air/gas fill for graft attachment.

Translation of cell-based therapies into clinical practice

The translation of cell therapies using human-cultivated CECs into clinical trials requires specialised laboratory facilities and trained personnel with the appropriate expertise, specifically the ability to propagate CECs within an accredited Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) environment.126– 128 139 158 Regulatory safety standards must also be met to use such cultured CECs in human clinical trials.139 In our recent work, we showed the ability to consistently propagate human CECs within a GMP environment.139 When we delivered these CECs into a rabbit model of bullous keratopathy through both intracameral cell-injection or tissue-engineered approaches, in vivo functionality was demonstrated by a reversal of corneal oedema.134 139 In 2018, a pioneering clinical trial reporting the results of cell-injection therapy for corneal endothelial failure was published.135 Investigators demonstrated that the injection of cultivated CECs in growth medium augmented with rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor, effectively treated corneal oedema and restored vision; outcomes were stable up to 24 months postoperatively.135 Further institutional review board-approved clinical trials investigating the clinical outcomes of tissue-engineered corneal endothelial transplantations are also underway (clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04319848).9 139

The availability of different modalities to deliver CECs is important. Each mode of delivery of CECs may be applicable to varying scenarios, depending on the pathophysiologies of the disease. We have previously demonstrated that an intact DM is essential for cell-injection therapies to work.134 Thus, cell-injection may not be suitable in all situations of corneal endothelial diseases. For instance, in the initial mild stages of diseases such as PBK or graft failure, where DMs are relatively spared, removal of CECs through DM scraping and replacing CECs via cell-injection may be the modality of choice.134 On the contrary, in advanced diseases with scarring of the DM, DM-stripping to remove abnormal DM is required. These patients may require other modalities of cell deliveries such as tissue-engineered grafts because cell-injection is known to be less effective without a DM.134 Likewise, in FECD, guttae and extracellular matrix excrescences on the DM can significantly affect vision.159 Our group has also shown that the height and density of guttae may affect the formation of a CEC monolayer160 and that large guttae can be toxic to injected endothelial cells.161 Thus, DM may need to be stripped in FECD with significant guttae and cell-injection may not be suitable. Future imaging techniques in development may allow us to evaluate the characteristics of these guttae to predict the success of cell-injection therapies.162

Alternative sources of corneal endothelial cells for cell-based therapies

Along with the expansion of primary CECs in culture, other studies have investigated alternative sources of CECs. Such alternative sources include the differentiation of adult cells into CECs phenotype. An example of such sources includes adult skin-derived precursor cells, which are thought to be embryonic neural-crest-related precursors, exhibiting similar characteristics to neural-crest stem cells.163 As CECs are embryologically derived from the neural-crest,164 165 investigators have successfully produced CEC-like cells differentiated from adult skin-derived precursor cells.166 The therapeutic effects of these cells were further demonstrated in different animal models of bullous keratopathy.166 Another example is the differentiation of neural-crest cells and subsequently, CECs from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from adult dermal fibroblasts.167 More recently, scientists have also used synthesised DM-like substrates to stimulate the differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells into CEC-like cells through mechanotransductive effects.168 However, such alternative sources of CECs are at present largely experimental and culture protocols still require optimisation.

One key advantage of producing CECs from extraocular precursor cells to treat a patient with corneal endothelial failure is the ability to use non-ocular cells from the same patient with ocular disease. Such autologous sources of CECs would be valuable in minimising the risks of allogeneic rejection encountered in conventional keratoplasty surgeries. In the advent of genetic editing, such as the use of CRISPR endonucleases, treatment of corneal endothelial diseases using CECs derived from allogeneic sources may be feasible even in patients who have genetic predispositions to corneal disorders.169 An example is individuals with FECD who have the CTG trinucleotide repeat expansion mutation within the TCF4 gene.169– 171

Regenerative medicine approach to endothelial replacement

Role of Rho-associated kinases (ROCK) inhibitors in corneal diseases

Rho-associated kinases (ROCK) belong to the AGC (cAMP-dependent protein kinase/protein kinase G/protein kinase C) family of serine-threonine protein kinases.172– 174 Due to the therapeutic potential of modifying cellular functions, ROCK-signalling pathway has become a popular field of research in recent years.

Activated ROCK leads to the phosphorylation of downstream targets. Principally, these targets regulate smooth muscle contraction through calcium ion sensitisation. They are important in controlling signal transduction pathways central to essential cellular function including stress fibres contraction, cell adhesion, cellular motility, cell proliferation, and apoptosis.175 ROCK also play a crucial role in modulating inflammatory cellular infiltration and migration.176 Furthermore, ROCK signalling has been reported to be involved in gene expression that leads to cell cycle regulation and differentiation.175 However, the role of ROCK in physiological pathways is cell specific and can vary depending on the cell line. The effects of inhibition of ROCK may also vary from one tissue to another. There is still little understanding of such differences.

In ophthalmology, ROCK inhibitors have been shown to have an effect in intraocular pressures lowering, important in the management of glaucoma.177 178 ROCK inhibitors have been shown to regulate conventional aqueous humour outflow facility through cell modifications, including cytoskeletal rearrangement, reduced cellular contraction and cell–cell contact in the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm canal.179– 185 More recently, ROCK inhibitors have been investigated for their applications in regenerative therapies for corneal endothelial diseases.186– 191 Unlike their effects on aqueous humour outflow, the inhibition of ROCK signalling in CECs has been shown to promote cell adhesion, inhibit apoptosis and enhance cellular proliferation in cultivated primate and human CECs.188 190 Clinical reports have also described the recovery of corneal endothelial function following transcorneal freezing of patients with corneal endothelial dysfunction and the administration of ROCK inhibitor eye drops.187 191 As mentioned above, in addition to the use of ROCK inhibitors in regenerative therapies, they also serve as important components of effective cultivation methods to propagate CECs for use in cell-based therapies.192

Surgical techniques in regenerative medicine

Two surgical techniques introduced recently that use regenerative medicine in the treatment of corneal endothelial diseases are Descemetorrhexis without endothelial keratoplasty (DWEK)/Descemet’s stripping only (DSO) and Descemet’s membrane transplantation (DMT).9 Studies have indicated that corneal transplants performed for diseases in which healthy CECs are preserved in the peripheral cornea (eg, FECD) can achieve better graft survival compared to transplants performed for diseases causing widespread CEC loss (eg, pseudophakic bullous keratopathy).26 These observations have led to the concept of host CECs centripetal migration, which forms the underlying basis of DWEK/DSO and DMT.9

In ‘DWEK’ (or more recently accepted terminology of ‘DSO’),193 diseased CE and DM in the central cornea of patients are removed to allow the central migration and redistribution of healthy peripheral CECs to restore endothelial function.194 This avoids the need for endothelial replacement through transplantation. However, clinical case series evaluating DSO for FECDs have reported variable results.195– 199 DSO appears to be more reliable if only the central 4.00 mm of diseased DM is stripped197 198 or when patients received topical rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitors.198 199 Larger randomised comparative studies with longer-term follow-up are required to establish the effectiveness of DSO as an intervention.

The importance of an intact DM to facilitate the central migration of CECs has since been described.200 Unlike DSO where the central corneal is left without a DM, following central stripping of diseased CE and DM, a decellularised DM is transplanted into the stripped area to enable CEC migration in DMT.9 Using this technique, the functionality of the CE to restore corneal clarity has been reported.200 201 This can allow for a larger descemetorhexis to be performed, that is, removal of a larger area of guttae.

To prepare a DMT graft, a donor cornea with ECD unsuitable for conventional transplantation (eg, <2000 cells/mm2) undergoes a double freeze-thaw cycle.9 Subsequently, a manual removal of CECs from the donor cornea is performed using a silicone-tipped cannula (catalogue number: SP-125053, ASICO, USA). An acellular DMT graft is then obtained via a donor harvesting technique used in DMEK (eg, SCUBA technique). As a larger population of peripheral host CECs following central descemtorhexis promote a more stable postmigration CEC population and faster recovery of cellular function,202 the size of the harvested DMT graft is kept small (4.0–5.0 mm).9 As the size of the DMT graft is small, one can also harvest multiple grafts from a single donor cornea or even harvest DMT grafts from donor corneal rims whose central cornea has been harvested for conventional transplant surgeries. Such used donor corneal rims are currently discarded. Thus, one donor cornea can be used to treat more than one patient with endothelial disease. The procedure of DMT graft insertion is similar to standard DMEK surgery. Figure 5E–L shows the procedure of DMT performed in FECD patient.

As the DMT graft is acellular, risks of immunological rejection and need for long-term immunosuppressive agents encountered in conventional transplantation are avoided. Additionally, donor tissues that are not suitable for conventional keratoplasties due to insufficient ECDs can be repurposed and used.9 Nevertheless, the success of regenerative medicine for corneal endothelial dysfunction does rely on appropriate patient selection. The first successful DMT was performed on a 56-year-old patient with FECD.201 As the migratory potential of CECs declines with advancing age,203 DMT performed on older patients may require additional measures to support CEC migration. These measures include the use of topical ROCK inhibitors (eg, Y-27 632, netarsudil, ripasudil) in DMT.9 The evidence in DMT, however, are based on animal data and case reports200 201 and studies with larger sample size and longer duration of follow-up are required.

It is worth noting that in regenerative medicine techniques, cells migrating from the periphery may be patients’ diseased cells, such as FECD. Thus, disease phenotypes like guttae may still develop in the future. However, such regenerative approaches would have potentially delayed the age at which a corneal transplantation is required.

CONCLUSION

Over the past two decades, a paradigm shift from full-thickness penetrating keratoplasties to partial-thickness advanced endothelial keratoplasties has significantly improved the outcomes of corneal transplantations performed on patients with corneal endothelial diseases. Despite being effective in reversing corneal blindness, being donor dependent may mean that conventional corneal transplantation techniques will likely be replaced by novel alternatives, including scalable cell-based therapies and regenerative medicine. Further translational research and clinical trials are required to improve the specific therapeutic techniques and determine the long-term safety and efficacies of each novel therapy. Understanding the applicability of each of these treatment modalities according to the various underlying pathophysiologies may mean a more personalised approach to the future management of endothelial disease.

Footnotes

Twitter: Hon Shing Ong @onghonshing.

Contributors: Conceptualisation and supervision: HSO, JM. Data curation/literature review: HSO. Formal nalysis and figures: HSO, JM. Writing draft, review and editing: HSO, MA, JM. All authors approved the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclaimer: This review contains some concepts that have been previously presented in a book format (Ong HS, Mehta JS. Corneal Endothelial Reconstruction: Current and Future Approaches in Agarwal A, Narang P. Video Atlas of Anterior Segment Repair and Reconstruction—Managing Challenges in Cornea, Glaucoma, and Lens Surgery. Stuttgart, New York, Rio: Thieme Publishing Group, 2019:41–52).

Competing interests: JSM holds a patent on the EndoGlide and receive royalties. The other authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bonanno JA. Molecular mechanisms underlying the corneal endothelial pump. Exp Eye Res 2012;95:2–7. 10.1016/j.exer.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Edelhauser HF. The balance between corneal transparency and edema: the proctor lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47:1754–67. 10.1167/iovs.05-1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bahn CF, Glassman RM, MacCallum DK, et al. Postnatal development of corneal endothelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1986;27:44–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bourne WM. Biology of the corneal endothelium in health and disease. Eye (Lond) 2003;17:912–8. 10.1038/sj.eye.6700559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nucci P, Brancato R, Mets MB, et al. Normal endothelial cell density range in childhood. Arch Ophthalmol 1990;108:247–8. 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070040099039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bourne WM, Nelson LR, Hodge DO. Central corneal endothelial cell changes over a ten-year period. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1997;38:779–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yee RW, Matsuda M, Schultz RO, et al. Changes in the normal corneal endothelial cellular pattern as a function of age. Curr Eye Res 1985;4:671–8. 10.3109/02713688509017661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mahdy MA, Eid MZ, Mohammed MA, et al. Relationship between endothelial cell loss and microcoaxial phacoemulsification parameters in noncomplicated cataract surgery. Clin Ophthalmol 2012;6:503–10. 10.2147/OPTH.S29865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ong HS, Mehta JS. Corneal endothelial reconstruction: current and future approaches in Agarwal A, Narang P. Video atlas of anterior segment repair and reconstruction—managing challenges in cornea, glaucoma, and lens surgery. Stuttgart, New York, Rio de Janeiro: Thieme Publishing Group, 2019:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tuft SJ, Coster DJ. The corneal endothelium. Eye 1990;4:389–424. 10.1038/eye.1990.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McCartney MD, Wood TO, McLaughlin BJ. Freeze-fracture label of functional and dysfunctional human corneal endothelium. Curr Eye Res 1987;6:589–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murphy C, Alvarado J, Juster R, et al. Prenatal and postnatal cellularity of the human corneal endothelium. A quantitative histologic study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1984;25:312–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Edelhauser HF. The resiliency of the corneal endothelium to refractive and intraocular surgery. Cornea 2000;19:263–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Joyce NC, Meklir B, Joyce SJ, et al. Cell cycle protein expression and proliferative status in human corneal cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1996;37:645–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Joyce NC, Navon SE, Roy S, et al. Expression of cell cycle-associated proteins in human and rabbit corneal endothelium in situ. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1996;37:1566–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Joyce NC, Harris DL, Mello DM. Mechanisms of mitotic inhibition in corneal endothelium: contact inhibition and TGF-beta2. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002;43:2152–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Joyce NC. Proliferative capacity of corneal endothelial cells. Exp Eye Res 2012;95:16–23. 10.1016/j.exer.2011.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lu J, Lu Z, Reinach P, et al. TGF-beta2 inhibits AKT activation and FGF-2-induced corneal endothelial cell proliferation. Exp Cell Res 2006;312:3631–40. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Joyce NC, Harris DL, Zieske JD. Mitotic inhibition of corneal endothelium in neonatal rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1998;39:2572–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gain P, Jullienne R, He Z, et al. Global survey of corneal transplantation and eye banking. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016;134:167–73. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.4776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Australian Corneal Graft Registry C . The Australian graft registry 2018 report. Secondary the Australian graft registry 2018 report 2018. Available https://dspace.flinders.edu.au/xmlui/bitstream/handle/2328/37917/ACGR%202018%20Report.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

- 22. Ang M, Soh Y, Htoon HM, et al. Five-year graft survival comparing Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmology 2016;123:1646–52. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.04.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Woo JH, Ang M, Htoon HM, et al. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty versus Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol 2019;207:288–303. 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fuest M, Yam GH, Peh GS, et al. Advances in corneal cell therapy. Regen Med 2016;11:601–15. 10.2217/rme-2016-0054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zirm EK. Eine erfolgreiche totale Keratoplastik (A successful total keratoplasty). 1906. Refract Corneal Surg 1989;5:258–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Coster DJ, Lowe MT, Keane MC, et al. Australian Corneal Graft Registry C. A comparison of lamellar and penetrating keratoplasty outcomes: a registry study. Ophthalmology 2014;121:979–87. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tan DT, Dart JK, Holland EJ, et al. Corneal transplantation. Lancet 2012;379:1749–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60437-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tillett CW. Posterior lamellar keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol 1956;41:530–3. 10.1016/0002-9394(56)91269-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barraquer JI. Lamellar keratoplasty. (Special techniques). Ann Ophthalmol 1972;4:437–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guell JL, El Husseiny MA, Manero F, et al. Historical review and update of surgical treatment for corneal endothelial diseases. Ophthalmol Ther 2014;3(1-2):1–15. 10.1007/s40123-014-0022-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Melles GR, Eggink FA, Lander F, et al. A surgical technique for posterior lamellar keratoplasty. Cornea 1998;17:618–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Melles GR, Lander F, van Dooren BT, et al. , Preliminary clinical results of posterior lamellar keratoplasty through a sclerocorneal pocket incision. Ophthalmology 2000;107:1850–6. discussion 57. 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00253-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Terry MA, Ousley PJ. Deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty in the first United States patients: early clinical results. Cornea 2001;20:239–43. 10.1097/00003226-200104000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Terry MA, Ousley PJ. Rapid visual rehabilitation after endothelial transplants with deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty (DLEK). Cornea 2004;23:143–53. 10.1097/00003226-200403000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bahar I, Sansanayudh W, Levinger E, et al. Posterior lamellar keratoplasty: comparison of deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty and Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty in the same patients: a patient’s perspective. Br J Ophthalmol 2009;93:186–90. 10.1136/bjo.2007.136630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bahar I, Kaiserman I, McAllum P, et al. Comparison of posterior lamellar keratoplasty techniques to penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmol 2008;115:1525–33. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mashor RS, Kaiserman I, Kumar NL, et al. Deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty: up to 5-year follow-up. Ophthalmol 2010;117:680–6. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.12.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Melles GR, Wijdh RH, Nieuwendaal CP. A technique to excise the Descemet membrane from a recipient cornea (descemetorhexis). Cornea 2004;23:286–8. 10.1097/00003226-200404000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gorovoy MS. Descemet-stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea 2006;25:886–9. 10.1097/01.ico.0000214224.90743.01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. EBAA . Eye banking statistical report. Secondary eye banking statistical report 2018. Available https://restoresight.org/what-we-do/publications/statistical-report/

- 41. Park CY, Lee JK, Gore PK, et al. Keratoplasty in the United States: a 10-year review from 2005 through 2014. Ophthalmol 2015;122:2432–42. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ang M, Htoon HM, Cajucom-Uy HY, et al. Donor and surgical risk factors for primary graft failure following Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty in Asian eyes. Clin Ophthalmol 2011;5:1503–8. 10.2147/OPTH.S25973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ang M, Mehta JS, Lim F, et al. Endothelial cell loss and graft survival after Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmol 2012;119:2239–44. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ang M, Mehta JS, Anshu A, et al. Endothelial cell counts after Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty versus penetrating keratoplasty in Asian eyes. Clin Ophthalmol 2012;6:537–44. 10.2147/OPTH.S26343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ang M, Lim F, Htoon HM, et al. Visual acuity and contrast sensitivity following Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Br J Ophthalmol 2016;100:307–11. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Koenig SB, Covert DJ, Dupps WJ Jr., et al. Visual acuity, refractive error, and endothelial cell density six months after Descemet stripping and automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK). Cornea 2007;26:670–4. 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3180544902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fuest M, Ang M, Htoon HM, et al. Long-term visual outcomes comparing Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol 2017;182:62–71. 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Terry MA, Shamie N, Chen ES, et al. Endothelial keratoplasty for Fuchs’ dystrophy with cataract: complications and clinical results with the new triple procedure. Ophthalmol 2009;116:631–9. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bose S, Ang M, Mehta JS, et al. Cost-effectiveness of Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty versus penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmol 2013;120:464–70. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tan D, Ang M, Arundhati A, et al. Development of selective lamellar keratoplasty within an Asian corneal transplant program: the Singapore corneal transplant study (an American Ophthalmological Society Thesis). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2015;113:T10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mehta JS, Por YM, Poh R, et al. Comparison of donor insertion techniques for Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:1383–8. 10.1001/archopht.126.10.1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ang M, Saroj L, Htoon HM, et al. Comparison of a donor insertion device to sheets glide in Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty: 3-year outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol 2014;157:1163–69 e3. 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.02.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Busin M, Bhatt PR, Scorcia V. A modified technique for Descemet membrane stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty to minimize endothelial cell loss. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:1133–7. 10.1001/archopht.126.8.1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Khor WB, Mehta JS, Tan DT. Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty with a graft insertion device: surgical technique and early clinical results. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;151:223–32 e2. 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wendel LJ, Goins KM, Sutphin JE, et al. Comparison of bifold forceps and cartridge injector suture pull-through insertion techniques for Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea 2011;30:273–6. 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181eadb84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tsatsos M, Athanasiadis I, Kopsachilis N, et al. Comparison of the endosaver with noninjector techniques in Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty. Indian J Ophthalmol 2017;65:1133–7. 10.4103/ijo.IJO_360_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kobayashi A, Yokogawa H, Sugiyama K. Clinical results of the Neusidl Corneal Inserter((R)), a new donor inserter for Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty, for small Asian eyes. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging 2012;43:311–8. 10.3928/15428877-20120426-04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. KD N, JM B, EJ H. Comparison of central corneal graft thickness to visual acuity outcomes in endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea 2011;30:388–91. 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181f236c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Shinton AJ, Tsatsos M, Konstantopoulos A, et al. Impact of graft thickness on visual acuity after Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:246–9. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Busin M, Madi S, Santorum P, et al. Ultrathin Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty with the microkeratome double-pass technique: two-year outcomes. Ophthalmol 2013;120:1186–94. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Busin M, Patel AK, Scorcia V, et al. Microkeratome-assisted preparation of ultrathin grafts for Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53:521–4. 10.1167/iovs.11-7753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Thomas PB, Mukherjee AN, O’Donovan D, et al. Preconditioned donor corneal thickness for microthin endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea 2013;32:e173–8. 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182912fd2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rosa AM, Silva MF, Quadrado MJ, et al. Femtosecond laser and microkeratome-assisted Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty: first clinical results. Br J Ophthalmol 2013;97:1104–7. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Patel SV, Baratz KH, Hodge DO, et al. The effect of corneal light scatter on vision after Descemet stripping with endothelial keratoplasty. Arch Ophthalmol 2009;127:153–60. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Droutsas K, Lazaridis A, Giallouros E, et al. Scheimpflug densitometry after DMEK versus DSAEK-two-year outcomes. Cornea 2018;37:455–61. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tappin M. A method for true endothelial cell (Tencell) transplantation using a custom-made cannula for the treatment of endothelial cell failure. Eye (Lond) 2007;21:775–9. 10.1038/sj.eye.6702326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Melles GR, Ong TS, Ververs B, et al. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK). Cornea 2006;25:987–90. 10.1097/01.ico.0000248385.16896.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ang M, Wilkins MR, Mehta JS, et al. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Br J Ophthalmol 2016;100:15–21. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Singh A, Zarei-Ghanavati M, Avadhanam V, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical outcomes of Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty versus descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty/Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea 2017;36:1437–43. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Droutsas K, Lazaridis A, Papaconstantinou D, et al. Visual outcomes after Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty versus Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty-comparison of specific matched pairs. Cornea 2016;35:765–71. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Tourtas T, Laaser K, Bachmann BO, et al. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty versus Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol 2012;153:1082–90 e2. 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Maier AK, Gundlach E, Gonnermann J, et al. Retrospective contralateral study comparing Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty with Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Eye (Lond) 2015;29:327–32. 10.1038/eye.2014.280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Goldich Y, Showail M, Avni-Zauberman N, et al. Contralateral eye comparison of Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty and Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol 2015;159:155–9 e1. 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Guerra FP, Anshu A, Price MO, et al. Endothelial keratoplasty: fellow eyes comparison of Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty and Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea 2011;30:1382–6. 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31821ddd25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Marques RE, Guerra PS, Sousa DC, et al. DMEK versus DSAEK for Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy: a meta-analysis. Eur J Ophthalmol 2018;1120672118757431. 10.1177/1120672118757431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ang M, Sng CCA. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty and glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2018;29:178–84. 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Price MO, Giebel AW, Fairchild KM, et al. Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty: prospective multicenter study of visual and refractive outcomes and endothelial survival. Ophthalmology 2009;116:2361–8. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Dirisamer M, Ham L, Dapena I, et al. Efficacy of Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty: clinical outcome of 200 consecutive cases after a learning curve of 25 cases. Arch Ophthalmol 2011;129:1435–43. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Feng MT, Price MO, Miller JM, et al. Air reinjection and endothelial cell density in Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty: five-year follow-up. J Cataract Refract Surg 2014;40:1116–21. 10.1016/j.jcrs.2014.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Johnson DH, Bourne WM, Campbell RJ. The ultrastructure of Descemet’s membrane. I. Changes with age in normal corneas. Arch Ophthalmol 1982;100:1942–7. 10.1001/archopht.1982.01030040922011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Brissette A, Conlon R, Teichman JC, et al. Evaluation of a new technique for preparation of endothelial grafts for Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea 2015;34:557–9. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Tan TE, Devarajan K, Seah XY, et al. Lamellar dissection technique for Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty graft preparation. Cornea 2020;39:23–9. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Weber IP, Rana M, Thomas PBM, et al. Effect of vital dyes on human corneal endothelium and elasticity of Descemet’s membrane. PLoS One 2017;12:e0184375. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Ang M, Dubis AM, Wilkins MR. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty: intraoperative and postoperative imaging spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med 2015;2015:506251. 10.1155/2015/506251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Veldman PB, Dye PK, Holiman JD, et al. The S-stamp in Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty safely eliminates upside-down graft implantation. Ophthalmology 2016;123:161–4. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Bhogal M, Maurino V, Allan BD. Use of a single peripheral triangular mark to ensure correct graft orientation in Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. J Cataract Refract Surg 2015;41:2022–4. 10.1016/j.jcrs.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Muraine M, Gueudry J, He Z, et al. Novel technique for the preparation of corneal grafts for Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol 2013;156:851–9. 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Zarei-Ghanavati S, Zarei-Ghanavati M, Ramirez-Miranda A, Air-assisted donor preparation for DMEK. J Cataract Refract Surg 2011;37:1372. author reply 72. 10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Chamani T, Javadi MA, Kanavi MR. Trephine- and dye-free technique for eye bank preparation of pre-stripped Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty tissue. Cell Tissue Bank 2019;20:321–6. 10.1007/s10561-019-09771-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Deng SX, Sanchez PJ, Chen L. Clinical outcomes of Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty using eye bank-prepared tissues. Am J Ophthalmol 2015;159:590–6. 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Parekh M, Baruzzo M, Favaro E, et al. Standardizing Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty graft preparation method in the eye bank-experience of 527 Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty tissues. Cornea 2017;36:1458–66. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Terry MA. Endothelial keratoplasty: a comparison of complication rates and endothelial survival between precut tissue and surgeon-cut tissue by a single DSAEK surgeon. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2009;107:184–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Yong KL, Nguyen HV, Cajucom-Uy HY, et al. Cost minimization analysis of precut cornea grafts in Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2887. 10.1097/MD.0000000000002887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Menzel-Severing J, Walter P, Plum WJ, et al. Assessment of corneal endothelium during continued organ culture of pre-stripped human donor tissue for DMEK surgery. Curr Eye Res 2018;43:1439–44. 10.1080/02713683.2018.1501805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Newman LR, DeMill DL, Zeidenweber DA, et al. Preloaded Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty donor tissue: surgical technique and early clinical results. Cornea 2018;37:981–6. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Regnier M, Auxenfans C, Maucort-Boulch D, et al. Eye bank prepared versus surgeon cut endothelial graft tissue for Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty: an observational study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e6885. 10.1097/MD.0000000000006885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Rickmann A, Wahl S, Hofmann N, et al. Precut DMEK using dextran-containing storage medium is equivalent to conventional DMEK: a prospective pilot study. Cornea 2019;38:24–9. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Mohammed I, Ross AR, Britton JO, et al. Elastin content and distribution in endothelial keratoplasty tissue determines direction of scrolling. Am J Ophthalmol 2018;194:16–25. 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Kruse FE, Schrehardt US, Tourtas T. Optimizing outcomes with Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2014;25:325–34. 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Bennett A, Mahmoud S, Drury D, et al. Impact of donor age on corneal endothelium-Descemet membrane layer scroll formation. Eye Contact Lens 2015;41:236–9. 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Schaub F, Enders P, Zachewicz J, et al. Impact of donor age on Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty outcome: evaluation of donors aged 17-55 years. Am J Ophthalmol 2016;170:119–27. 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Dapena I, Moutsouris K, Droutsas K, et al. Standardized “no-touch” technique for Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Arch Ophthalmol 2011;129:88–94. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Arnalich-Montiel F, Munoz-Negrete FJ, De Miguel MP. Double port injector device to reduce endothelial damage in DMEK. Eye (Lond) 2014;28:748–51. 10.1038/eye.2014.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Kruse FE, Laaser K, Cursiefen C, et al. A stepwise approach to donor preparation and insertion increases safety and outcome of Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea 2011;30:580–7. 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182000e2e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Kim EC, Bonfadini G, Todd L, et al. Simple, inexpensive, and effective injector for Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea 2014;33:649–52. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Monnereau C, Quilendrino R, Dapena I, et al. Multicenter study of Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty: first case series of 18 surgeons. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014;132:1192–8. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Dirisamer M, van Dijk K, Dapena I, et al. Prevention and management of graft detachment in Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Arch Ophthalmol 2012;130:280–91. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Oellerich S, Baydoun L, Peraza-Nieves J, et al. Multicenter study of 6-month clinical outcomes after Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea 2017;36:1467–76. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Maier AK, Gundlach E, Schroeter J, et al. Influence of the difficulty of graft unfolding and attachment on the outcome in Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2015;253:895–900. 10.1007/s00417-015-2939-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Phillips PM, Phillips LJ, Muthappan V, et al. Experienced DSAEK surgeon’s transition to DMEK: outcomes comparing the last 100 DSAEK surgeries with the first 100 DMEK surgeries exclusively using previously published techniques. Cornea 2017;36:275–9. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Liarakos VS, Dapena I, Ham L, et al. Intraocular graft unfolding techniques in Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. JAMA Ophthalmol 2013;131:29–35. 10.1001/2013.jamaophthalmol.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Yoeruek E, Bayyoud T, Hofmann J, et al. Novel maneuver facilitating Descemet membrane unfolding in the anterior chamber. Cornea 2013;32:370–3. 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318254fa06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Heinzelmann S, Bohringer D, Haverkamp C, et al. Influence of postoperative intraocular pressure on graft detachment after Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea 2018;37:1347–50. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Ang M, Mehta JS, Newman SD, et al. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty: preliminary results of a donor insertion pull-through technique using a donor mat device. Am J Ophthalmol 2016;171:27–34. 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Busin M, Leon P, D’Angelo S, et al. Clinical outcomes of preloaded Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty grafts with endothelium tri-folded inwards. Am J Ophthalmol 2018;193:106–13. 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Leon P, Parekh M, Nahum Y, et al. Factors associated with early graft detachment in primary Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol 2018;187:117–24. 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Price MO, Lisek M, Kelley M, et al. Endothelium-in versus endothelium-out insertion with Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea 2018;37:1098–101. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Birbal RS, Hsien S, Zygoura V, et al. Outcomes of hemi-Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty for Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Cornea 2018;37:854–8. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Zygoura V, Baydoun L, Ham L, et al. Quarter-Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (Quarter-DMEK) for Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy: 6 months clinical outcome. Br J Ophthalmol 2018;102:1425–30. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-311398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Agarwal A, Dua HS, Narang P, et al. Pre-Descemet’s endothelial keratoplasty (PDEK). Br J Ophthalmol 2014;98:1181–5. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Bachmann BO, Tourtas T, et al. Ultrastructure of the posterior corneal stroma. Ophthalmology 2015;122:693–9. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Pascolini D, Mariotti SP. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:614–8. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Greenrod EB, Jones MN, Kaye S, et al. Center and surgeon effect on outcomes of endothelial keratoplasty versus penetrating keratoplasty in the United Kingdom. Am J Ophthalmol 2014;158:957–66. 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.07.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Price FW Jr., Feng MT, Price MO. Evolution of endothelial keratoplasty: where are we headed? Cornea 2015;34:S41–7. 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Shtein RM, Raoof-Daneshvar D, Lin HC, et al. Keratoplasty for corneal endothelial disease, 2001–2009. Ophthalmology 2012;119:1303–10. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Peh GS, Chng Z, Ang HP, et al. Propagation of human corneal endothelial cells: a novel dual media approach. Cell Transplant 2015;24:287–304. 10.3727/096368913x675719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Peh GS, Toh KP, Ang HP, et al. Optimization of human corneal endothelial cell culture: density dependency of successful cultures in vitro. BMC Res Notes 2013;6:176. 10.1186/1756-0500-6-176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Peh GS, Toh KP, Wu FY, et al. Cultivation of human corneal endothelial cells isolated from paired donor corneas. PLoS One 2011;6:e28310. 10.1371/journal.pone.0028310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Bostan C, Theriault M, Forget KJ, et al. In vivo functionality of a corneal endothelium transplanted by cell-injection therapy in a feline model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016;57:1620–34. 10.1167/iovs.15-17625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]