Children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable to perceive the COVID-19 related restrictions of social contacts as a burden, because social contacts are crucial in their development to adulthood. (1, 2). Given this background, the nationwide COPSY study of the mental health and quality of life of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic was initiated, in which children and adolescents themselves as well as their parents were interviewed. The objective was to examine the effects of the crisis on the mental health and quality of life of children and adolescents.

Methods

From 26 May 2020 to 10 June 2020, a total of n=1040 children and adolescents aged between 11 and 17 years, and their parents participated in the online study providing self- and parent proxy-reports; for additionally n=546 children aged 7 to 10 years parent proxy-reports were gathered (overall participation rate 46%). In terms of their main characteristics, the study sample and participants were largely consistent with the structure of the corresponding population according to the most recent micro census (2018). Following the recommendations of the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM), we used internationally validated questionnaires to collect data on psychosomatic symptoms, health-related quality of life (KIDSCREEN-10 index), mental health problems (Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire [SDQ]), generalized anxiety (Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders [SCARED]), and depressive symptoms (Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression [CES-D]). The data were analyzed providing descriptive statistics, bivariate and multivariate regression analyses. The results were compared with the results of representative longitudinal nationwide studies before the pandemic (3, 4).

Results

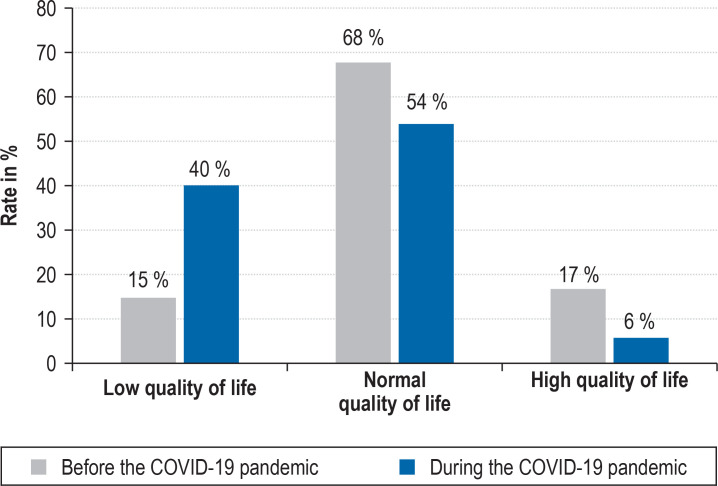

The mean age of the sample of children and adolescents (n=1040) was 14.3 years (51.1% girls, 15.5% with a migration background), that of the parents was 43.9 years (mean age of their children 12.2 years, 50% mothers, 55.7% with a medium level of education). 71% (95% confidence interval [68; 74]) of children and adolescents felt burdened by the contact restrictions during the pandemic. 65% [62; 68] experienced school and learning as more exhausting than before. 27% [24; 30] reported having more arguments. 37% [35; 39] of parents reported that arguments with their children escalated more often. In 39% [36; 42] of children and adolescents, relationships with friends deteriorated as a result of restricted personal contacts, which was burdensome for almost all survey participants. The rate of children and adolescents experiencing low health-related quality of life was notably higher during the pandemic (40% [37; 43] versus 15% [13; 17]) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Self-reported quality of life in children and adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (low quality of life: score at least 1 standard deviation (SD) below the mean of the standard population, high quality of life: score at least 1 SD above the mean of the standard population). The difference in the quality of life values between both studies had a mean effect size (Cohen‘s f2 = 0.14).

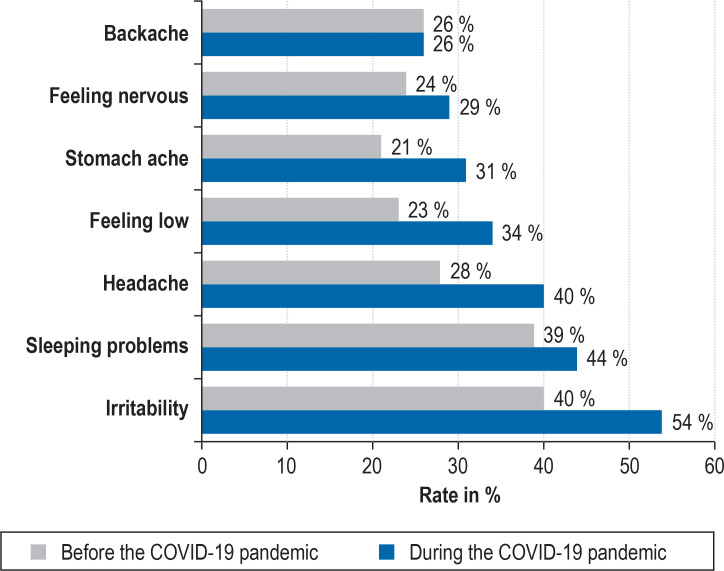

Psychosomatic symptoms were more common during than before the COVID-19 crisis: irritability (54% [51; 57] versus 40% [38; 41]), sleeping problems (44% [41; 47] versus 39% [38; 41]), headache (40% [37; 43] versus 28% [27; 30]), feeling low [34% [31; 37] versus 23% [22; 24]), and stomach ache (31% [28; 34] versus 21% [20; 23]) (figure 2). The risk for mental health problems rose from about 18% [16; 20] to 30% [28; 32] during the pandemic (SDQ, proxy-report; Cohen’s f² = 0.04). However, no clear difference (p>0.05) was observed in the self-reported depressive symptoms (CES-D) compared with the time period before the pandemic. For generalized anxiety (SCARED), symptoms were more pronounced during the pandemic (24% [21; 27] versus 15% [13; 17] before the crisis), but with a negligible effect size (Cohen’s f² = 0.01).

Figure 2.

Psychosomatic symptoms in children and adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The figure shows the rates of children and adolescents with relevant symptoms at least once every week during the COVID-19 crisis (COPSY study) and during the time preceding the crisis (4).

Risks and resources regarding mental health and quality of life

We assumed that children and adolescents living in families with poor atmosphere and concomitantly either with parents who had a low level of education, or migration background, or if they were living in close quarters (<20 sq m living space/person) might have experienced the changes imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic as particularly burdensome. In this group (n=126) we found higher levels of pandemic related burden (43% [53; 32] versus 27% [29; 24], p=0.005), higher levels of psychosomatic symptoms (d effect size [d-ES]=0.67; p<0.001), a notably lower quality of life (d-ES=0.67; p<0.001) and more pronounced symptoms of anxiety (d-ES=0.37; p<0.001) and depression (d-ES=0.64; p<0.001). Furthermore, the results of a multivariate linear regression model (n=1016; F(8,1.007)=122.36; p<0.001; corrected R² = 0.49), showed that resources can strengthen health-related quality of life. Children and adolescents who looked into the future optimistically and confidently (personal resource; regression weight [B]=7.58 [6.82; 8.33]; p<0.001; Cohen’s f² = 0.39) had a higher health-related quality of life, as did those who spent a lot of time together with their parents (familial resource; B=1.46 [0.91; 2.02]; p<0.001; Cohen’s f² = 0.14).

Discussion

The COPSY study showed that the challenges posed by the pandemic reduce the quality of life and mental wellbeing in children and adolescents and increase the risk of mental health problems. The findings are consistent with those of studies from China (2), India, Italy, the USA, and Germany (5), which also found a greater extent of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress reactions during the pandemic, although current data are limited. Furthermore it should be kept in mind that self-reported symptoms do not constitute an illness in themselves but should be considered as positive screening results that require further investigation. Particularly socially disadvantaged children are most affected. In order to protect and preserve the mental health of children and adolescents during crisis situations, target group specific and easy-access services for prevention and health promotion are needed.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Birte Twisselmann, PhD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Fegert JM, Vitiello B, Plener PL, Clemens V. Challenges and burden of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Ment Health. 2020;14 doi: 10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xie X, Xue Q, Zhou Y, et al. Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1619. e201619. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1619. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ravens-Sieberer U, Otto C, Kriston L, et al. The longitudinal BELLA study: design, methods and first results on the course of mental health problems. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2015;24:651–663. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0638-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inchley J, Currie D, Budisavljevic S, et al. Spotlight on adolescent health and well-being Findings from the 2017/2018 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey in Europe and Canada. International report. Volume 1. Key findings. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. www.hbsc.org/publications/international/ (last accessed on 18 August 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langmeyer A, Guglhör-Rudan A, Naab T, et al. Kindsein in Zeiten von Corona. Erste Ergebnisse zum veränderten Alltag und zum Wohlbefinden von Kindern. In. München: Deutsches Jugendinstitut; 2020 [Google Scholar]