Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Internationally, adult asthma medication adherence rates are low. Studies characterizing variations in barriers by country are lacking.

OBJECTIVE:

To conduct a scoping review to characterize international variations in barriers to asthma medication adherence among adults.

METHODS:

MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science (WOS), and CINAHL were searched from inception to February 2017. English-language studies employing qualitative methods (eg, focus groups, interviews) were selected to assess adult patient- and/or caregiver-reported barriers to asthma medication adherence. Two investigators independently identified, extracted data, and collected study characteristics, methodologic approach, and barriers. Barriers were mapped using the Theoretical Domains Framework and findings categorized according to participants’ country of residence, countries’ gross national income, and the presence of universal health care (World Health Organization definitions).

RESULTS:

Among 2942 unique abstracts, we reviewed 809 full texts. Among these, we identified 47 studies, conducted in 12 countries, meeting eligibility. Studies included a total of 2614 subjects, predominately female (67%), with the mean age of 19.1 to 70 years. Most commonly reported barriers were beliefs about consequences (eg, medications not needed for asthma control, N [ 29, 61.7%) and knowledge (eg, not knowing when to take medication, N = 29, 61.7%) and knowledge (eg, not knowing when to take N = 27, 57.4%); least common was goals (eg, asthma not a priority, N = 1, 2.1%). In 27 studies conducted in countries classified as high income (HIC) with universal health care (UHC), the most reported barrier was participants’ beliefs about consequences (N = 17, 63.3%). However, environmental context and resources (N = 12, 66.7%) were more common in HIC without UHC.

CONCLUSION:

International adherence barriers are diverse and may vary with a country’s sociopolitical context. Future adherence interventions should account for trends.

Keywords: Asthma, Medication adherence, Compliance, Black, African American, Qualitative research, Behavioral research, Behavior change, Theoretical Domains Framework, World Health Organization, Gross national income, Universal health care

Globally, asthma affects 339 million people and is associated with significant disability, health care utilization, impaired quality of life, and mortality.1–3 There are many contributors to asthma morbidity and mortality including gross national income, access to health care, air pollution, occupational exposures, and environmental tobacco smoke.1 However, it is estimated that nonadherence to asthma medications affects 30% to 70% of adults with asthma and improving adherence is a key strategy to reducing the global burden of asthma.4–7

Barriers to asthma medication adherence include, but are not limited to, poor asthma knowledge, cost, and access to health insurance.8 In research studies, these barriers are often the target of adherence interventions.9,10 However, evidence suggests that some of these barriers, including medication costs and access to health care insurance, are influenced by the sociopolitical contexts within different countries.8 To reduce the global burden of asthma, adherence interventions may need to be tailored to the sociopolitical contexts of individuals’ countries of residence.

Little is known about how barriers to asthma medication adherence might differ around the globe based on various countries’ gross national income and provision of universal health care coverage. Examining variation in barriers to adherence among countries with different sociopolitical contexts could inform the development of future interventions tailored to address individuals’ contexts.

We sought to describe and characterize trends in patient-reported barriers to asthma medication adherence in countries of varied economic wealth and health care coverage.

METHODS

We conducted a scoping literature review to identify adult asthma patient–reported barriers to asthma medication adherence among countries with varied economic wealth and universal health care policies. We categorized barriers by domains in the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), a framework commonly used to characterize barriers to behavior change.11

Literature search strategy

We designed our search strategy to be inclusive as possible of published and nonpublished investigations. An experienced librarian conducted searches in MEDLINE, Excerpt Medical database (EMBASE), Web of Science (WOS), and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) from inception to February 2017. Investigators performed quality checks to ensure that the search identified known (ie, highly publicized or impactful) studies on asthma medication adherence. Our search strategy used a combination of Medical Subject Headings terms and key words focused on “asthma,” “medication adherence,” and “qualitative methods” (see Table E1 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org for full search strategy).

We identified unpublished studies and conference abstracts through WOS. For conference abstracts, we searched for full text articles and additional reported outcomes in MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and the clinicaltrials.gov database. We excluded conference abstracts if no associated peer-reviewed publications were identified. We searched the references of studies included in our analysis and the references of prior review articles to identify additional studies that may meet our eligibility criteria. We imported all citations into DistillerSR.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We established a priori study eligibility criteria (Table I). We sought to identify studies that used qualitative methods (eg, focus groups, interviews) to elicit the first-hand perspectives of adults with asthma and their caregivers’ perspectives about asthma medications. We limited to studies on adults because the barriers to adherence in children are different due to children’s rapid developmental transitions, limited input in treatment decisions, and larger dependence on caregivers.12–16 If studies included adults and children, they were included if the adult patient perspectives were reported separately from children’s perspectives. We limited to patients and their caregivers because we were interested in primary accounts of barriers to asthma medication adherence. Caregivers were included to give voice to adult patients who may not be able to adequately express their perspectives (eg, disability, limited capacity). We limited to studies using qualitative methods including focus groups and interviews. We limited to qualitative approaches that used open-ended questions to obtain a broader range of barriers to asthma medication adherence. We excluded studies that exclusively assessed barriers exclusively using closed-ended questions (eg, questionnaires) with prespecified answers because we were interested in obtaining a comprehensive list of patient-reported barriers to asthma medication adherence with minimal restriction placed by the investigators. We excluded studies that did not separately report findings for our study population (eg, adult asthma) and/or topic of interest (eg, asthma, asthma medication) (Table I).

TABLE I.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Method/approach | Qualitative approach—study includes focus groups or interviews with open-ended questions | All other approaches |

| Population | Age 18 years or older or adult data reported separately Patients with asthma or asthma data reported separately |

All other populations |

| Perspective | Reports the perspectives of adult asthma patients and/or the caregivers of adult asthma patients or reports adults/caregivers’ perspectives separately | Sole perspectives of providers, children, health systems, or any other nonadult patient/caregiver perspectives |

| Topic | Asthma medications | All other topics |

Study selection

Two members of the team independently reviewed each title and abstract for eligibility (SR/DC, ILR/RP, ILR/DC). Reviewers resolved conflicts by discussion, and the third reviewer (ILR or SR) adjudicated disagreements, if needed, during all stages of the review. Two team members (SR/DC) independently reviewed the full text of articles, and discrepancies in inclusion/exclusion were resolved by discussion. We recorded the main reason for exclusion at each stage of study selection. The reasons for full text exclusion were assessed in hierarchical order. We first assessed for the correct approach, and then population, perspective, and topic (Table I).

Data extraction and analysis

Two independent reviewers (SR, DC) extracted data from each study meeting our inclusion criteria with a standardized and structured form. Reviewers resolved conflicts by discussion, and the third reviewer (ILR) adjudicated disagreements.

Our primary outcome of interest was patient-reported barriers to asthma medication adherence. Barriers to asthma medication adherence were categorized using the TDF. The TDF is a behavior change theory with 14 domains covering a wide range of potential barriers.17,18 Definitions for TDF domains are included in Table II.

TABLE II.

Definitions for domains in the Theoretical Domains Framework for asthma studies

| Theoretical domain | Definition |

|---|---|

| Knowledge | Familiarity, awareness, and understanding of asthma (eg, know when to use inhalers) |

| Skills | An ability or proficiency to self-manage asthma acquired through practice (eg, know how to use an asthma action plan, know how to use each inhaler) |

| Social/professional role and identity | A sense of self based on membership in a social or professional group (eg, identifying as caretaker in their family) |

| Beliefs about capabilities | Belief in one’s ability to manage his or her asthma |

| Optimism | Belief or confidence that asthma can be controlled; belief that taking asthma medication can decrease asthma symptoms |

| Beliefs about consequences | Acceptance of truth or belief that asthma behaviors (eg, medication adherence, allergy avoidance) lead to a given outcome |

| Reinforcement | To encourage, strengthen, or provide support for asthma management |

| Intentions | A conscious decision to perform asthma self-management skills such as asthma medication adherence and allergy avoidance |

| Goals | Mental outcomes that a person wants to achieve (eg, ability to play with their children, no asthma exacerbations) |

| Memory, attention, and decision processes | The ability to remember, focus, and choose asthma self-management (eg, remembering to take asthma medication, choosing to take heart medication and not asthma medication) |

| Environmental context and resources | Any circumstance of a person’s environment (eg, physical, social, political, financial) that affects asthma self-management (eg, cost, access to health insurance, social support) |

| Social influences | Changing ideas and actions in response to another person or social group |

| Emotion | A state of mind or mental reaction determined by one’s circumstances (eg, fear, stressed, happy) |

| Behavioral regulation | Resist using unhealthy behaviors to manage emotions and purse a goal (eg, not smoking when stressed so asthma remains well controlled) |

Reviewers also extracted information on studies’ population demographics (eg, age, sex), approach (eg, interview, focus group), study topic (eg, asthma, asthma medications), participants’ country of residence, the country’s World Health Organization (WHO) and World Bank income level (ie, high income, middle income, low income), and countries’ presence of universal health care.22,23 Gross national income level was defined by WHO and World Bank definition.23 We categorized studies by WHO gross national income and presence of universal health care because medication adherence is known to be associated with socioeconomic status and access to health care.8 Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the included studies.

RESULTS

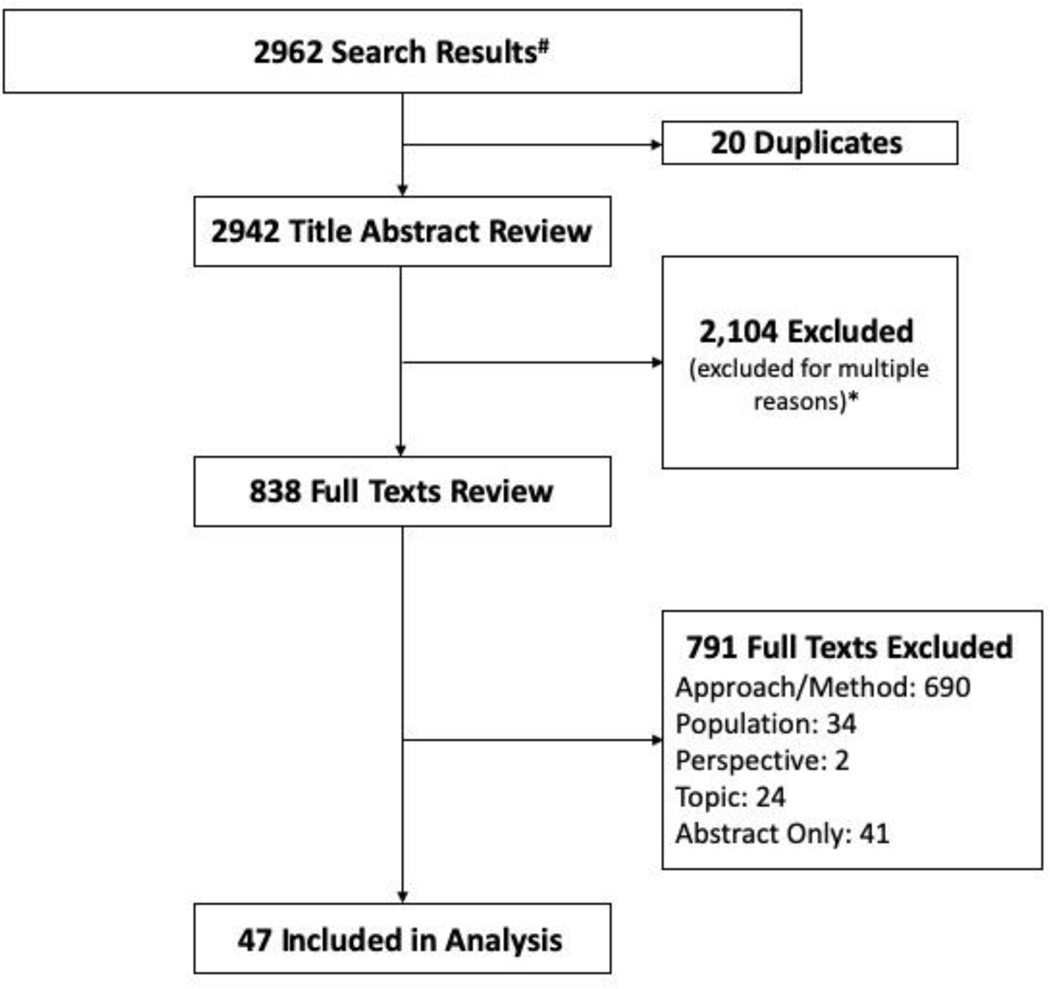

We identified 2942 unique titles and abstracts and assessed 838 full text manuscripts for eligibility (Figure 1). Using our inclusion/exclusion criteria, we excluded 791 full text manuscripts. The full texts were excluded because 690 did not meet our study approach criteria by not including open-ended questions as part of their qualitative approach or by not using qualitative methods. Thirty-four did not meet the population criteria because they had pediatric or mixed pediatric and adult population without subgroup analysis of adults. Two studies did not report the perspectives of adults, or caregivers of adults, with asthma, whereas 24 did not report barriers to asthma medication adherence. Forty-one studies were excluded because they did not have full texts associated with their abstracts (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Scoping literature review flow diagram. #Sources: EMBASE, Excerpta Medica dataBASE; WOS, Web of Science; CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; and MEDLINE. *Excluded for multiple reasons including: nonqualitative study (eg, epidemiologic, intervention, exclusive quantitative methods), exclusively conducted in children, exclusively a nonasthma condition, or exclusively from a nonpatient/caregiver perspective.

For our analysis, we included 47 studies meeting our inclusion criteria that were conducted in 12 countries. The included studies had a total of 2614 subjects with the mean age ranging from 19.1 to 70 years and were predominately female (67%) subjects (Table III). Most studies exclusively used interviews (N = 36) and focused on asthma medications (N = 22) or asthma in general (N = 21). Most studies were conducted in high-income countries (N = 45), few were conducted in middle-income countries (N = 2), and no studies were conducted in low-income countries. Twenty-seven studies were conducted in countries with universal health care and 20 in countries without universal health care. Of the studies (N = 20) conducted in countries without universal health care, most (N = 17) were conducted in the United States (Table III).

TABLE III.

Study characteristics by country

| Study characteristics | Australia N = 824–31 | Brazil N = 132 | Canada N = 433–36 | Denmark N = 137 | India N = 138 | Ireland (N = 139) | The Netherlands N = 340–42 | Sweden N = 243,44 | United Kingdom N = 845–52 | United States N = 1753–69 | Spain, France, and United Kingdom N = 170 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication years (range) | 2002–2016 | 2008 | 2008–2014 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2010–2015 | 2001–2013 | 1997–2010 | 2003–2016 | 2003 |

| Subjects per study (n) | 17–62 | NA | 13–29 | NA | NA | NA | 13–19 | 63–216 | 10–35 | 5–328 | NA |

| Total subjects (n) | 317 | 160 | 79 | 10 | 160 | 31 | 51 | 279 | 185 | 1296 | 46 |

| Mean age range (y) | 39–79 5 NR | 49 | 40.2–52.5 1 NR | NR | 51.5 | 43.1 | NR | 22–52 | 39.5–44 4 NR | 19.1–67.7 5 NR | 34 |

| Female:male | 148 F:54 M 3 NR | 120 F:40 M | 48 F:31 M | 6 F:4 M | 73 F:87 M | 21 F:10 M | 33 F:18 M | 184 F:95 M | 73 F:56 M 2 NR | 481 F:188 M 5 NR | 26 F:20 M |

| Approach | 6 Int 2 FG/Int | 1 Int1 | 1 Int 3 FG2 | 1 Int | 1 Int | FG | 2 Int 1 FG/Int | 2 Int | 8 Int | 13 Int 5 FG | 1 Int |

| Study focus | |||||||||||

| Asthma medication | 2 | 1 | 2 | - | - | - | 2 | 2 | 7 | 6 | - |

| General asthma | 3 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 11 | 1 |

| Other | 3 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| WHO income | High | Middle | High | High | Middle | High | High | High | High | High | High |

| Universal health care | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

FG, focus group; Int, interview; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; WHO, World Health Organization.

Eight countries were classified as high income with universal health care and included 27 studies with 1127 subjects (Table III). Two countries were classified as high income without universal health care and included 18 studies with 1327 subjects—most of the studies (N = 17) were conducted in the United States. Two studies were classified as middle income without universal health care and included 320 subjects (Table III).

Study outcome

Internationally, patient-reported barriers to asthma medication adherence are diverse. The most commonly reported barriers to asthma medication adherence were categorized as beliefs about consequences (eg, medications not needed for asthma control, N = 29, 61.7%), knowledge (eg, not knowing when to take medication, N = 27, 57.4%), and environmental context and resources (eg, costs, N = 25, 53.2%). The least commonly reported barriers were goals (eg, asthma not a priority, N = 1, 2.1%), reinforcement (eg, asthma not valued, N = 3, 6.4%), and emotion (eg, fear of dependence, stress, N = 3, 6.4%) (Table IV). Table V includes examples of barriers categorized by domains in the TDF.

TABLE IV.

Patient-reported barriers to asthma medication adherence categorized by the Theoretical Domains Framework

| Domains | Total N = 47 | Australia N = 824–31 | Brazil N = 132 | Canada N = 433–36 | Denmark N = 137 | India N = 138 | Ireland N = 139 | The Netherlands N = 340–42 | Sweden N = 243,44 | United Kingdom N = 845–52 | United States N = 1753–69 | Spain, France, and United Kingdom N = 170 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | 27 (57.4%) | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | - | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 9 | - |

| Skills | 14 (29.8%) | 3 | - | 3 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 2 | 4 | - |

| Identity | 9 (19.1%) | 1 | - | 2 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | - | - |

| Beliefs about capability | 15 (31.9%) | 4 | - | 2 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | - |

| Optimism | 3 (6.4%) | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Beliefs about consequences | 29 (61.7%) | 4 | - | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 1 |

| Reinforcement | 3 (6.4%) | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - |

| Intentions | 10 (21.3%) | 1 | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Goals | 1 (2.1%) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Memory, attention, and decision processes | 17 (36.2%) | 3 | 1 | 2 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 8 | 1 |

| Environmental context and resources | 25 (53.2%) | 3 | 1 | 3 | - | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 11 | - |

| Social influences | 19 (40.4%) | 3 | - | 4 | - | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | - |

| Emotion | 17 (36.2%) | 2 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | - |

| Behavioral regulation | 16 (34.0%) | 4 | - | 3 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | 5 | - |

TABLE V.

Patient-reported barriers to asthma medication adherence categorized by domains in the Theoretical Domains Framework

| Theoretical domain | Paraphrased statements |

|---|---|

| Knowledge | The most important thing is to ensure our understanding46 I do not like to take medicine without asking questions49 I like to know what providers do. They never tell you things. You have to find it out for yourself49 |

| Skills | It’s important to learn how to use medication properly30 |

| Social/professional role and identity | When you are responsible for other people you forget about yourself. It’s men’s nature to think about themselves first, but women think about others first. I take care of my family with medical problems so asthma is not always my “priority.”68 |

| Beliefs about capabilities | It is very difficult to accept that you have asthma. You have to accept you are taking your asthma medication and everything is fine33 |

| Beliefs about consequences | I frequently do not take my inhalers because when I do not have symptoms; I tell myself that I do not need it35 I just take medications when I need them because I’m anti-drug and pill51 |

| Memory, attention, and decision processes | Taking medication is something you add to an already busy schedule35 I work and I have a small child. I’m so busy that it’s hard to remember to take my asthma medication68 |

| Environmental context and resources | I cannot afford my steroid inhaler. I try to compensate by using my rescue inhaler more24 I knew I was going to have a gap in insurance coverage, so I stockpiled my medication for me and my kids. I made sure I filled prescriptions even if I didn’t use them67 |

| Emotion | I’m afraid of becoming addicted to my asthma medication36 I hate taking my asthma medication. The doctor said there are no long-term concerns, but I was scared that I would get immune to them24 |

Quotes may be categorized in more than one domain in the Theoretical Domains Framework.

Analysis by WHO gross national income level and universal health care

In high-income countries with universal health care, the 3 most commonly reported barriers were categorized as belief about consequences (N = 17, 63.3%), knowledge (N = 16, 59.3%), and social influence (N = 12, 44.4%). In high-income countries without universal health care, the most commonly reported barriers were categorized as environmental context and resources (N = 12, 66.7%), beliefs about consequences (N = 11, 61.1%), and knowledge (N = 10, 55.6%). In middle-income countries without universal health care, the most commonly reported barriers were categorized as memory, attention, and decision (N = 2, 100%); environmental context and resources (N = 2, 100%); and emotion (N = 2, 100%) (Table VI).

TABLE VI.

Patient-reported barriers to asthma medication adherence by WHO gross national income level and universal health care

| High income with universal health care24–31,33–37,40–52,70 | High income without universal health care53–70 | Middle income without universal health care32,38 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Domains Framework Domains | N = 27 studies (%) 1127 subjects | N = 18 studies (%) 1327 subjects | N = 2 studies (%) 320 subjects |

| Knowledge | 16 (59.3) | 10 (55.6) | 1 (50.0) |

| Skills | 9 (33.3) | 4 (22.2) | 1 (50.0) |

| Identity | 8 (29.6) | 1 (5.6) | 0 |

| Beliefs about capability | 11 (40.7) | 4 (22.2) | 0 |

| Optimism | 3 (11.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Beliefs about consequences | 17 (63.0) | 11 (61.1) | 1 (50.0) |

| Reinforcement | 2 (7.4) | 0 | 1 (50.0) |

| Intentions | 7 (25.9) | 3 (16.7) | 0 |

| Goals | 1 (3.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Memory, attention, and decision processes | 7 (25.9) | 8 (44.4) | 2 (100) |

| Environmental context and resources | 11 (40.7) | 12 (66.7) | 2 (100) |

| Social influences | 12 (44.4) | 6 (33.3) | 1 (50.0) |

| Emotion | 7 (25.9) | 8 (44.4) | 2 (100) |

| Behavioral regulation | 11 (40.7) | 5 (27.8) | 0 |

High-income countries with universal health care: Australia, Canada, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, United Kingdom, France, and Spain.

High-income countries without universal health care: United States and Republic of Ireland.

Middle-income countries without universal health care: Brazil and India.

WHO, World Health Organization.

DISCUSSION

In this scoping review of 47 studies conducted among 12 nations, we found that study participants reported a wide range of barriers to asthma medications adherence, and that the prevalence of barriers reported appeared to differ according to the presence of universal health care and gross national income. Lack of knowledge about asthma and belief about consequences were the most frequently reported barriers across all countries. Environmental context and resources, such as cost and access to health care, were more frequently reported among studies conducted in countries without universal health care, whereas barriers related to social influences were more commonly reported in countries with universal health care. Our study can inform future adherence interventions through its description of the unique distributions of global asthma medication adherence barriers.

Our findings are consistent with the literature. Lack of knowledge and environmental context and resources are commonly cited as barriers to general medication adherence71 and specifically asthma medication adherence.72,73 Indeed, there are interventions targeting these barriers such as asthma self-management programs, motivational interviewing, and services that provide free or low cost access to asthma medications.9,10,74 However, there has been less emphasis on barriers categorized in the other domains of the TDF (eg, social identity, beliefs about consequences) despite their common occurrence in our study.

To our knowledge, this is the first international characterization of barriers to asthma medication adherence among qualitative studies in pulmonary disease. Our study is unique in that we categorized global barriers to adherence, and we used a comprehensive behavior change theory—the TDF—that can facilitate the development of future adherence interventions. There is increasing evidence that public health and health promotion interventions based on social and behavioral theory are more effective than those lacking a theoretical base.11 Theory-based conceptual models (1) identify the behavioral antecedents (ie, barriers/enablers) and their relationship to the target behavior, (2) select intervention methods to match targeted barrier/enablers, (3) inform intervention evaluation, and (4) identify “active ingredients” in interventions.75 The TDF synthesizes elements of existing behavioral theories (eg, health belief model, social cognitive theory, theory of planned behavior) most relevant to changing behavior and was developed using an expert consensus process and validation. Compared with any single behavioral theory, the TDF covers a wider range of potential barriers and enablers and is therefore likely to identify more potential intervention strategies to improve asthma medication adherence. Our study provides the necessary foundation to describe and characterize barriers that can be used as future intervention targets.

There were a few limitations to this scoping review. The 47 included studies represent 12 countries, but there were only 2 middle-income countries, no low-income countries, and no studies conducted in Eastern Europe, Middle-East, Africa, Central America, or Asia. In addition, approximately 50% of study participants were from the United States. We aimed for primary accounts of barriers to adherence so we may have missed some barriers by limiting to the perspectives of adult patients and their caregivers and excluding input from providers and health system staff. Our analysis was underpowered to statistically compare the relative prevalence of barriers. Lastly, our search was through 2017. Though the search yielded a comprehensive identification of barriers in all domains of our behavior theory, the included patient perspectives were collected before widespread use, and research of single maintenance and reliever therapy (SMART) in mild and moderate asthma and may not represent barriers to SMART.

Internationally, patients with asthma have a diverse set of barriers to asthma medication adherence. Lack of knowledge about asthma and belief about consequences were the most frequently reported barriers across all countries.The relative prevalence of barriers due to social influences was more commonly reported in high-income countries with universal health care, whereas environmental consequences and resources were more commonly reported in high-income countries without universal health care. These findings highlight the diversity in barriers to adherence in various countries, the need for interventions targeting multiple barriers to adherence, and the tailoring of intervention to the unique distribution of barriers based on the person’s sociopolitical context.

Supplementary Material

What is already known about this topic?

Internationally, adult patients with asthma have poor asthma medication adherence.

What does this article add to our knowledge?

This article describes the diverse reasons for asthma medication adherence reported by patients around the world and how they may change based on the sociopolitical context in which patients live.

How does this study impact current management guidelines?

On the basis of the findings of this study, providers should inquire about a broad set of reasons for asthma medication nonadherence with focus on the most common barriers reported in a particular country.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Duke University School of Medicine Institutional Support.

Abbreviations used

- CINAHL

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- EMBASE

Excerpt Medical Database

- SMART

Single maintenance and reliever therapy

- TDF

Theoretical Domains Framework

- WHO

World Health Organization

- WOS

Web of Science

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Global Initiative for Asthma. The Global Asthma Report 2018. Auckland, New Zealand: Global Asthma Network; 2018. Available from: http://www.globalasthmareport.org/Global%20Asthma%20Report%202018.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bender BG, Rand C. Medication non-adherence and asthma treatment cost. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;4:191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engelkes M, Janssens HM, de Jongste JC, Sturkenboom MC, Verhamme KM. Medication adherence and the risk of severe asthma exacerbations: a systematic review. Eur Respir J 2015;45:396–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bateman E, Hurd S, Barnes P, Bousquet J, Drazen J, FitzGerald M, et al. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J 2008;31:143–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bender BG, Bender SE. Patient-identified barriers to asthma treatment adherence: responses to interviews, focus groups, and questionnaires. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2005;25:107–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rand CS, Wise RA. Measuring adherence to asthma medication regimens. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;149:69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams LK, Joseph CL, Peterson EL, Wells K, Wang M, Chowdhry VK, et al. Patients with asthma who do not fill their inhaled corticosteroids: a study of primary nonadherence. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120:1153–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McQuaid EL. Barriers to medication adherence in asthma: the importance of culture and context. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018;121:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viswanathan M, Golin CE, Jones CD, Ashok M, Blalock SJ, Wines RC, et al. Interventions to improve adherence to self-administered medications for chronic diseases in the United States: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2012;157: 785–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moullec G, Gour-Provencal G, Bacon SL, Campbell TS, Lavoie KL. Efficacy of interventions to improve adherence to inhaled corticosteroids in adult asthmatics: impact of using components of the chronic care model. Respir Med 2012;106:1211–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health 2010; 31:399–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnett JJ. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late TeensThrough the Twenties. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashman JJ, Conviser R, Pounds MB. Associations between HIV-positive individuals’ receipt of ancillary services and medical care receipt and retention. AIDS Care 2004;14(Suppl 1):s109–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsui D. Current issues in pediatric medication adherence. Paediatr Drugs 2007;9:283–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winnick S, Lucas DO, Hartman AL, Toll D. How do you improve compliance? Pediatrics 2005;115:e718–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charach A. ADHD treatment: strategies for optimizing adherence. Consultant 2011;51:824–33. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the Theoretical Domains Framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci 2012;7:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011;6:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Debono D, Taylor N, Lipworth W, Greenfield D, Travaglia J, Black D, et al. Applying the Theoretical Domains Framework to identify barriers and targeted interventions to enhance nurses’ use of electronic medication management systems in two Australian hospitals. Implement Sci 2017;12:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips CJ, Marshall AP, Chaves NJ, Jankelowitz SK, Lin IB, Loy CT, et al. Experiences of using the Theoretical Domains Framework across diverse clinical environments: a qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc 2015;8:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.VandenBos GR. APA Dictionary of Psychology. New York: American Psychological Association; 2007. Available from: https://www.health.ny.gov/regulations/hcra/univ_hlth_care.htm. Accessed October 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.New York State Department of Health. Foreign countries with universal healthcare. Updated April 2011. Available from: https://www.health.ny.gov/regulations/hcra/univ_hlth_care.htm. Accessed May 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.The World Bank Group. World Bank country and lending groups 2020. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed May 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goeman DP, Thien FC, Douglass JA, Aroni RA, Abramson MJ, Sawyer SM, et al. Back for more: a qualitative study of emergency department reattendance for asthma. Med J Aust 2004;180:113–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goeman DP, Thien FC, Abramson MJ, Douglass JA, Aroni RA, Sawyer SM, et al. Patients’ views of the burden of asthma: a qualitative study. Med J Aust 2002;177:295–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goeman DP, O’Hehir RE, Jenkins C, Scharf SL, Douglass JA. ‘You have to learn to live with it’: a qualitative and quantitative study of older people with asthma. Clin Respir J 2007;1:99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis SR, Durvasula S, Merhi D, Young PM, Traini D, Anticevich SZB. Knowledge that people with intellectual disabilities have of their inhaled asthma medications: messages for pharmacists. Int J Clin Pharm 2016;38:135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim AS, Stewart K, Abramson MJ, Ryan K, George J. Asthma during pregnancy: the experiences, concerns and views of pregnant women with asthma. J Asthma 2012;49:474–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naik-Panvelkar P, Saini B, LeMay KS, Emmerton LM, Stewart K, Burton DL, et al. A pharmacy asthma service achieves a change in patient responses from increased awareness to taking responsibility for their asthma. Int J Pharm Pract 2015;23:182–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saini B, LeMay K, Emmerton L, Krass I, Smith L, Bosnic-Anticevich S, et al. Asthma disease management—Australian pharmacists’ interventions improve patients’ asthma knowledge and this is sustained. Patient Educ Couns 2011;83: 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jillings C. Community living older adults described using medical, collaborative, and self agency models for asthma self management. Evid Based Nurs 2005;8:127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santos Pde M, D’Oliveira A Jr, Noblat Lde A, Machado AS, Noblat AC, Cruz AA. Predictors of adherence to treatment in patients with severe asthma treated at a referral center in Bahia, Brazil. J Bras Pneumol 2008; 34:995–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loignon C, Bedos C, Sévigny R, Leduc N. Understanding the self-care strategies of patients with asthma. Patient Educ Couns 2009;75:256–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peláez S, Bacon SL, Lacoste G, Lavoie KL. How can adherence to asthma medication be enhanced? Triangulation of key asthma stakeholders’ perspectives. J Asthma 2016;53:1076–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peláez S, Bacon SL, Aulls MW, Lacoste G, Lavoie KL. Similarities and differences between asthma health care professional and patient views regarding medication adherence. Can Respir J 2014;21:221–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poureslami I, Rootman I, Doyle-Waters MM, Nimmon L, FitzGerald JM. Health literacy, language, and ethnicity-related factors in newcomer asthma patients to Canada: a qualitative study. J Immigr Minor Health 2011;13: 315–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-kalemji A, Johannesen H, Dam Petersen K, Sherson D, Baelum J. Asthma from the patient’s perspective. J Asthma 2014;51:209–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gajanan G, Fernandes N, Avuthu S, Hattiholi J. Assessment of knowledge and attitude of bronchial asthma patients towards their disease. J Evol Med Dent Sci 2015;4:15508–15. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes M, Dunne M. The living with asthma study: issues affecting the perceived health and well-being of Irish adults with asthma. Ir J Med Sci 2016; 185:115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kopnina H, Haafkens J. Necessary alternatives: patients’ views of asthma treatment. Patient Prefer Adherence 2010;4:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kopnina DH. Contesting asthma medication: patients’ view of alternatives. J Asthma 2010;47:687–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Kruijssen V, vanStaa A, Dwarswaard J, Mennema B, Adams SA. Use of online self-management diaries in asthma and COPD: a qualitative study of subjects’ and professionals’ perceptions and behaviors. Respir Care 2015;60:1146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Axelsson M. Personality and reasons for not using asthma medication in young adults. Heart Lung 2013;42:241–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindberg M, Ekstrom T, Moller M, Ahlner J. Asthma care and factors affecting medication compliance: the patient’s point of view. Int J Qual Health Care 2001; 13:375–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams S, Pill R, Jones A. Medication, chronic illness and identity: the perspective of people with asthma. Soc Sci Med 1997;45:189–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doyle S, Lloyd A, Williams A, Chrystyn H, Moffat M, Thomas M, et al. What happens to patients who have their asthma device switched without their consent? Prim Care Respir J 2010;19:131–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schafheutle EI. The impact of prescription charges on asthma patients is uneven and unpredictable: evidence from qualitative interviews. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18:266–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shaw A, Thompson EA, Sharp D. Complementary therapy use by patients and parents of children with asthma and the implications for NHS care: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2006;6:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gamble J, Fitzsimons D, Lynes D, Heaney LG. Difficult asthma: people’s perspectives on taking corticosteroid therapy. J Clin Nurs 2007;16:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steven K, Morrison J, Drummond N. Lay versus professional motivation for asthma treatment: a cross-sectional, qualitative study in a single Glasgow general practice. Fam Pract 2002;19:172–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stevenson FA, Wallace G, Rivers P, Gerrett D. ‘It’s the best of two evils’: a study of patients’ perceived information needs about oral steroids for asthma. Health Expect 1999;2:185–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walsh S, Hagan T, Gamsu D. Rescuer and rescued: applying a cognitive analytic perspective to explore the ‘mis-management’ of asthma. Br J Med Psychol 2000;73:151–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brooks TL, Leventhal H, Wolf MS, O’Conor R, Morillo J, Martynenko M, et al. Strategies used by older adults with asthma for adherence to inhaled corticosteroids. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:1506–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Choi TN, Westermann H, Sayles W, Mancuso CA, Charlson ME. Beliefs about asthma medications: patients perceive both benefits and drawbacks. J Asthma 2008;45:409–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cortes T, Lee A, Boal J, Mion L, Butler A. Using focus groups to identify asthma care and education issues for elderly urban-dwelling minority individuals. Appl Nurs Res 2004;17:207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.George M, Freedman TG, Norfleet AL, Feldman HI, Apter AJ. Qualitative research-enhanced understanding of patients’ beliefs: results of focus groups with low-income, urban, African American adults with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;111:967–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.George M, Birck K, Hufford DJ, Jemmott LS, Weaver TE. Beliefs about asthma and complementary and alternative medicine in low-income inner-city African-American adults. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:1317–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.George M, Keddem S, Barg FK, Green S, Glanz K. Urban adults’ perceptions of factors influencing asthma control. J Asthma 2015;52:98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.George M, Abboud S, Pantalon MV, Sommers MLS, Mao J, Rand C. Changes in clinical conversations when providers are informed of asthma patients’ beliefs about medication use and integrative medical therapies. Heart Lung 2016;45: 70–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Janevic MR, Ellis KR, Sanders GM, Nelson BW, Clark NM. Self-management of multiple chronic conditions among African American women with asthma: a qualitative study. J Asthma 2014;51:243–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lawson CC, Carroll K, Gonzalez R, Priolo C, Apter AJ, Rhodes KV. “No other choice”: reasons for emergency department utilization among urban adults with acute asthma. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lindner P, Lindner A. Gender differences in asthma inhaler compliance. Conn Med 2014;78:207–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mancuso CA, Rincon M, Robbins L, Charlson ME. Patients’ expectations of asthma treatment. J Asthma 2003;40:873–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Newcomb PA, McGrath KW, Covington JK, Lazarus SC, Janson SL. Barriers to patient-clinician collaboration in asthma management: the patient experience. J Asthma 2010;47:192–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.O’Conor R, Martynenko M, Gagnon M, Hauser D, Young E, Lurio J, et al. A qualitative investigation of the impact of asthma and self-management strategies among older adults. J Asthma 2017;54:39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pai S, Boutin-Foster C, Mancuso CA, Loganathan R, Basir R, Kanna B. “Looking out for each other”: a qualitative study on the role of social network interactions in asthma management among adult Latino patients presenting to an emergency department. J Asthma 2014;51:714–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patel MR, Caldwell CH, Id-Deen E, Clark NM. Experiences addressing health-related financial challenges with disease management among African American women with asthma. J Asthma 2014;51:467–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Speck AL, Nelson B, Jefferson SO, Baptist AP . Young, African American adults with asthma: what matters to them? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2014; 112:35–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.MacDonell KK, Carcone AI, Naar-King S, Gibson-Scipio W, Lam P. African American emerging adults’ perspectives on taking asthma controller medication: adherence in the “Age of Feeling In-Between”. J Adolesc Res 2015;30: 607–24. [Google Scholar]

- 70.van Ganse E, Mork AC, Osman LM, Vermeire P, Laforest L, Marrel A, et al. Factors affecting adherence to asthma treatment: patient and physician perspectives. Prim Care Respir J 2003;12:46–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gellad WF, Grenard JL, Marcum ZA. A systematic review of barriers to medication adherence in the elderly: looking beyond cost and regimen complexity. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2011;9:11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Le TT, Bilderback A, Bender B, Wamboldt FS, Turner CF, Rand CS, et al. Do asthma medication beliefs mediate the relationship between minority status and adherence to therapy? J Asthma 2008;45:33–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Apter AJ, Boston RC, George M, Norfleet AL, Tenhave T, Coyne JC, et al. Modifiable barriers to adherence to inhaled steroids among adults with asthma: it’s not just black and white. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;111:1219–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lavoie KL, Moullec G, Lemiere C, Blais L, Labrecque M, Beauchesne MF, et al. Efficacy of brief motivational interviewing to improve adherence to inhaled corticosteroids among adult asthmatics: results from a randomized controlled pilot feasibility trial. Patient Prefer Adherence 2014;8:1555–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Langlois MA, Hallam JS. Integrating multiple health behavior theories into program planning: the PER worksheet. Health Promot Pract 2010;11:282–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.