Abstract

Background.

National data indicate that working-aged adults (20–64 years) are more likely to report financial barriers to receiving needed oral health care relative to other age groups. The aim of this study was to examine the burden of untreated caries (UC) and its association with reporting an unmet oral health care need among working-aged adults.

Methods.

The authors used National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data from 2011 through 2016 for 10,286 dentate adults to examine the prevalence of mild to moderate (1–3 affected teeth) and severe (≥ 4 affected teeth) UC. The authors used multivariable logistic regression to identify factors that were associated with reporting an unmet oral health care need.

Results.

Low-income adults had mild to moderate UC (26.2%) 2 times more frequently and severe UC (13.2%) 3 times more frequently than higher-income adults. After controlling for covariates, the variables most strongly associated with reporting an unmet oral health care need were UC, low income, fair or poor general health, smoking, and no private health insurance. The model-adjusted prevalence of reporting an unmet oral health care need among low-income adults with mild to moderate and severe UC were 35.7% and 45.1%, respectively.

Conclusions.

The burden of UC among low-income adults is high; prevalence was approximately 40% with approximately 3 affected teeth per person on average. Reporting an unmet oral health care need appears to be capturing primarily differences in UC, health, and financial access to oral health care.

Practical Implications.

Data on self-reported unmet oral health care need can have utility as a surveillance tool for monitoring UC and targeting resources to decrease UC among low-income adults.

Keywords: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, untreated caries, self-reported oral health care need, unmet dental care need, oral health surveillance tool, oral health care for working-aged adults

Unlike other age groups, the percentage (standard error [SE]) of working-aged adults (20–64 years) with a past-year dental visit has decreased over the past decade from 41.9% (0.6%) in 2004 to 37.9% (0.7%) in 2014.1 Dental service use falls well below the national health goal of 49%.2 Limited financial access is likely a contributing factor, as working-aged adults report inability to obtain needed oral health care owing to affordability (12.8%) almost 2 times more frequently compared with adults 65 years or older (7.2%) and 3 times more frequently than children and adolescents (4.3%).3 Limited financial access among some working-aged adults also may explain why this age group accounts for the largest share of hospital-based nontraumatic dental emergency department visits.4,5

Delaying needed care for caries can result in infection, pain, sleep deprivation, and lost productivity.6 It is estimated that more than 94 million work hours are lost annually because of unplanned dental visits for acute care needs.7 Early detection of caries can reduce the costs of restorations; allowing the disease to progress may require more complex, costly restorative treatment.8,9 Lack of access to comprehensive oral health care among adults is associated with higher receipt of tooth extraction to treat advanced caries.10 Tooth loss, in turn, is associated with difficulty eating, poor nutrition, and adverse psychosocial outcomes such as restricted social interaction and low self-esteem.6

To measure unmet oral health care need, variants of the question “During the past __ months, was there a time when you needed dental care but could not get it at that time?” have been used in national surveys—including the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey,11 the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES),12 and the National Health Interview Survey13—and state-based surveys.14,15 Follow-up questions about potential barriers to oral health care (for example, affordability) are also typically included. The utility of this question as a surveillance measure for untreated caries (UC) has not been established. A 2016 study that used this question to compare unmet needs for oral health care with other types of health care across age groups noted that 1 limitation of this question was that the exact nature of self-reported unmet oral health care need was not clear.3

In this study, we characterize the prevalence and severity of UC among working-aged adults overall and for selected characteristics. We also examine the prevalence of reporting inability to obtain needed oral health care within the past year for the same populations. We next examine the association between UC severity and reporting an unmet oral health care need after controlling for covariates. We hypothesize that reporting an unmet oral health care need is influenced by both presence of UC and financial access. To test this hypothesis, we examine whether self-reported unmet oral health care need was most strongly associated with measures of financial access compared with other access measures, and the association between unmet oral health care need and UC varied by income, our primary measure of financial access.

METHODS

Data set

We used data from the 2011–2016 NHANES.12 This survey includes information on respondents’ clinical health status, sociodemographic and economic status, and perceived health status. Data are collected via household interviews and standardized physical examinations in mobile examination centers. Visual oral health assessments were conducted by calibrated dentists in the mobile examination centers. The NHANES samples are selected through a complex, multistage probability design. NHANES data are publicly released for 2-year survey periods to protect confidentiality and increase statistical reliability. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board approved the protocol.16 Additional information on NHANES is available at the National Center for Health Statistics Web site (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm). We used the NHANES sample weights to obtain representative estimates for the US civilian, noninstitutionalized population.

Sample

Our study sample was dentate adults aged 20 through 64 years with complete data for self-reported unmet oral health care need, clinically assessed UC, and all other explanatory variables selected for this study. An adult was classified as being dentate if the examining dentist reported the presence of 1 or more permanent teeth, on the basis of a 28-tooth count.

Variables

Our 2 outcomes of interest were severity of UC—none, mild to moderate (1–3 affected teeth), and severe (≥ 4 affected teeth)—and self-reported unmet oral health care need, defined as a respondent answering “yes” to the question “Was there a time in the last 12 months when (you/study participant) needed dental care but could not get it?” Adults who reported an unmet oral health care need were asked follow-up questions related to barriers to receiving needed care. We classified these barriers as affordability (that is, cost of procedure, lack of insurance, or unable to miss work), acceptability or awareness (that is, fear of dentist or expected dental problem to go away), and accommodation or geographic access (that is, dental office not open at convenient hours or too far away), according to the dimensions of access identified by Penchansky and Thomas.17 Because respondents could select multiple reasons for not being able to get needed oral health care, calculated prevalence estimates for the reported barriers are not mutually exclusive.

Other variables used in this analysis included family income (< 200% of federal poverty guidelines [FPG] or ≥ 200% FPG), age (20–34, 35–49, and 50–64 years), sex, race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian, other [including multiracial]), education level (< high school, high school or equivalent, > high school), health insurance coverage status (private, public, none), self-reported general health (excellent, very good, or good; fair or poor), and smoking status (current, former, never). We did not include a variable on dental insurance coverage as this information was not collected in the NHANES.

Analyses

For the study sample as a whole and for each subgroup, we estimated the prevalence of UC severity and self-reported unmet oral health care need; among people with UC, we estimated the mean number of affected teeth.

We used χ2 tests to determine whether crude prevalence of UC and reported unmet oral health care need were associated with explanatory variables and t tests to determine whether the mean number of carious teeth differed by characteristic. We used multivariable logistic regression to examine the association between reported unmet oral health care need and UC after controlling for potential confounders, that is, the previously listed secondary explanatory variables. To test the hypothesis that among adults with the same UC, those with less financial access would report an unmet oral health care need more frequently, we included a term for interaction between UC severity and income (proxy for financial access) in the regression. We used the predicted marginals obtained from logistic regression to estimate the risk ratios (RRs) and absolute risk differences between the reference group and the remaining categories for each characteristic. The RRs were calculated to explore the strength of association between different group categories reporting unmet oral health care need.

We used SAS-callable SUDAAN software (RTI), which accounts for the complex multistage sampling of NHANES and the sample weights, for all statistical analyses. We used Taylor series linearization to compute variance estimates. All reported findings were significant at P values below .05.

RESULTS

Study sample

The study sample, dentate adults aged 20 through 64 years with data for all included variables in NHANES 2011–2016, was 10,286 adults.

UC

Almost 25% of working-aged adults had UC—17.8% with mild to moderate and 7.2% with severe UC (Table 1).12 Factors associated with higher prevalence of mild to moderate or severe UC were being younger, male, non-Hispanic black or Hispanic, less educated, current smoker, and reporting poor general health. Financial barriers also were associated with higher prevalence of mild to moderate UC (approximately 2 times higher among low-income [26.2%], publicly insured [20.5%], or not insured [29.4%] than among higher-income [13.2%] and privately insured [13.3%] adults) and higher prevalence of severe UC (approximately 2–3 times higher among low-income [13.2%], publicly insured [9.2%], and not insured adults [13.9%] than higher-income [3.9%] and privately insured [4.5%] adults). Among adults reporting an unmet oral health care need, prevalence of mild to moderate and severe UC was 32.4% and 18.7%, respectively.

Table 1.

Prevalence and severity of untreated caries among US adults aged 20 through 64 years, by select characteristics.*

| CHARACTERISTIC | PREVALENCE | CARIOUS TEETH AMONG ADULTS WITH UNTREATED CARIES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size, No. | 1–3 Teeth With Untreated Caries,† % (SE‡) | ≥ 4 Teeth With Untreated Caries,§ % (SE) | P Value¶ | Sample Size, No. | Affected Teeth, Mean No. (SE) | |

| Total | 10,286 | 17.8 (0.8) | 7.2 (0.4) | —# | 3,091 | 3.13 (0.08) |

| Age, y | < .001 | |||||

| 20–34 | 3,593 | 18.7 (1.0) | 9.4 (0.6) | 1,153 | 3.44 (0.13) | |

| 35–49 | 3,432 | 18.4 (1.2) | 7.4 (0.6) | 1,037 | 3.20 (0.14) | |

| 50–64 | 3,261 | 16.2 (1.1) | 4.6 (0.5) | 901 | 2.58 (0.11) | |

| Sex | .003 | |||||

| Male | 4,945 | 18.9 (1.0) | 8.1 (0.5) | 1,579 | 3.38 (0.12) | |

| Female | 5,341 | 16.7 (1.0) | 6.4 (0.4) | 1,512 | 2.86 (0.10) | |

| Race or Ethnicity** | < .001 | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 3,731 | 14.8 (0.9) | 6.4 (0.4) | 1,030 | 3.33 (0.11) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 2,381 | 28.6 (1.5) | 11.5 (1.1) | 960 | 2.95 (0.10) | |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 1,330 | 12.0 (1.1) | 2.8 (0.7) | 197 | 2.49 (0.20) | |

| Hispanic | 2,478 | 23.5 (1.3) | 8.7 (0.7) | 784 | 2.87 (0.15) | |

| Education Level | < .001 | |||||

| < High school | 1,833 | 29.8 (1.1) | 16.4 (1.2) | 823 | 3.48 (0.16) | |

| High school or equivalent | 2,207 | 24.3 (1.3) | 11.2 (0.9) | 853 | 3.35 (0.13) | |

| > High school | 6,246 | 13.6 (0.8) | 4.3 (0.3) | 1,415 | 2.84 (0.09) | |

| Income | < .001 | |||||

| < 200% federal poverty guidelines | 4,868 | 26.2 (1.0) | 13.2 (0.8) | 2,023 | 3.44 (0.12) | |

| ≥ 200% federal poverty guidelines | 5,418 | 13.2 (0.8) | 3.9 (0.4) | 1,068 | 2.75 (0.11) | |

| Health Insurance Coverage | < .001 | |||||

| Private coverage | 5,538 | 13.3 (0.8) | 4.5 (0.4) | 1,178 | 2.90 (0.09) | |

| Public or other coverage | 2,230 | 20.5 (1.6) | 9.2 (0.8) | 797 | 3.23 (0.13) | |

| No coverage of any type | 2,518 | 29.4 (1.4) | 13.9 (1.0) | 1,116 | 3.37 (0.17) | |

| General Health (Self-Report) | < .001 | |||||

| Excellent, very good, good | 8,204 | 16.5 (0.8) | 6.2 (0.4) | 2,260 | 3.07 (0.08) | |

| Fair, poor | 2,082 | 24.7 (1.4) | 12.7 (0.9) | 831 | 3.33 (0.12) | |

| Smoking Status | < .001 | |||||

| Current smoker | 2,231 | 26.8 (1.3) | 16.1 (1.2) | 1,043 | 3.78 (0.16) | |

| Former smoker | 1,905 | 17.8 (1.3) | 5.4 (0.6) | 531 | 268 (0.12) | |

| Never | 6,150 | 14.7 (0.9) | 4.7 (0.4) | 1,517 | 2.83 (0.10) | |

| Report Unmet Need | < .001 | |||||

| Yes | 2,548 | 32.4 (1.3) | 18.7 (1.1) | 1,338 | 3.70 (0.14) | |

| No | 7,738 | 14.1 (0.8) | 4.3 (0.3) | 1,753 | 2.74 (0.07) | |

| Untreated Caries Severity | – | |||||

| 0 teeth with untreated caries | 7,195 | – | – | – | – | |

| 1–3 teeth | 2,175 | – | – | 2,175 | 1.66 (0.02) | |

| ≥ 4 teeth | 916 | – | – | 916 | 6.76 (0.14) | |

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.12

Mild to moderate untreated caries.

SE: Standard error.

Severe untreated caries.

Significant at P < .05 by χ2 test.

–: Not applicable.

366 respondents in the “other (including multiracial)” Race/Ethnicity category were excluded from the study.

Among people with any UC, the mean number of affected teeth was 3.13; among people with mild to moderate and severe UC, the mean number was 1.66 and 6.76, respectively (Table 1). Among adults with mild to moderate UC, the mean (SE) number of affected teeth was slightly higher for low-income adults (1.7 [0.03]) than higher-income adults (1.6 [0.03]; data were not presented in Table 1).

Crude estimates of unmet oral health care need

Overall, 20.0% of US working-aged adults reported an unmet oral health care need (Table 2).12 Generally, the prevalence of reported unmet oral health care need was associated with the same factors as UC. Low-income adults (< 200% FPG) reported an unmet oral health care need almost 3 times more frequently than higher-income adults (36.2% versus 11.2%). Prevalence of reported unmet oral health care need among adults with mild to moderate and severe UC, 36.6% and 52.2%, respectively, was notably higher than prevalence among adults with no UC, 13.0%. The association between reported unmet oral health care need and UC differed by income—prevalence among low-income adults with no, mild to moderate, and severe UC was 26.8%, 46.9%, and 58.0%, respectively, and among higher-income adults, 7.6%, 25.3%, and 41.4%, respectively.

Table 2.

Prevalence of self-reported unmet oral health care need among US adults aged 20–64 years by selected characteristics.*

| CHARACTERISTIC | SAMPLE SIZE, NO. | SELF-REPORTED UNMET ORAL HEALTH CARE NEED, % (STANDARD ERROR) | P VALUE† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 10,286 | 20.0 (0.7) | |

| Age, y | .008 | ||

| 20–34 | 3,593 | 22.5 (1.0) | |

| 35–49 | 3,432 | 19.7 (1.0) | |

| 50–64 | 3,261 | 17.8 (1.1) | |

| Sex | .009 | ||

| Male | 4,945 | 18.8 (0.8) | |

| Female | 5,341 | 21.2 (0.9) | |

| Race or Ethnicity# | < .001 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 3,731 | 16.6 (0.8) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 2,381 | 28.3 (1.0) | |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 1,330 | 10.8 (0.7) | |

| Hispanic | 2,478 | 30.4 (1.2) | |

| Education Level | < .001 | ||

| < High school | 1,833 | 37.1 (1.6) | |

| High school or equivalent | 2,207 | 24.9 (1.2) | |

| > High school | 6,246 | 15.4 (0.7) | |

| Income | < .001 | ||

| < 200% federal poverty guidelines‡ | 4,868 | 36.2 (1.1) | |

| ≥ 200% federal poverty guidelines | 5,418 | 11.2 (0.6) | |

| Health Insurance Coverage | < .001 | ||

| Private coverage | 5,538 | 10.9 (0.5) | |

| Public or other coverage | 2,230 | 26.7 (1.4) | |

| No coverage of any type | 2,518 | 42.5 (1.4) | |

| Self-reported General Health | < .001 | ||

| Excellent, very good, good | 8,204 | 17.1 (0.6) | |

| Fair, poor | 2,082 | 36.5 (1.3) | |

| Smoking Status | < .001 | ||

| Current smoker | 2,231 | 34.2 (1.3) | |

| Former smoker | 1,905 | 20.4 (1.2) | |

| Never | 6,150 | 15.0 (0.7) | |

| Untreated Caries Severity | < .001 | ||

| 0 teeth with untreated caries | 7,195 | 13.0 (0.5) | |

| 1–3 teeth§ | 2,175 | 36.6 (1.2) | |

| ≥ 4 teeth¶ | 916 | 52.2 (1.9) | |

| Untreated Caries Severity, Low Income | < .001 | ||

| 0 teeth with untreated caries | 2,845 | 26.8 (1.2) | |

| 1–3 teeth§ | 1,351 | 46.9 (1.7) | |

| ≥ 4 teeth¶ | 672 | 58.0 (2.6) | |

| Untreated Caries Severity, High Income | < .001 | ||

| 0 teeth with untreated dental caries | 4,350 | 7.6 (0.5) | |

| 1–3 teeth§ | 824 | 25.3 (2.0) | |

| ≥ 4 teeth¶ | 244 | 41.4 (3.5) |

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.12

Significant at P < .05 by χ2 test.

FPG: Federal poverty guidelines.

Mild to moderate untreated caries.

Severe untreated caries.

366 respondents in the Race or Ethnicity category were excluded from the study.

Reasons for reporting unmet oral health care need

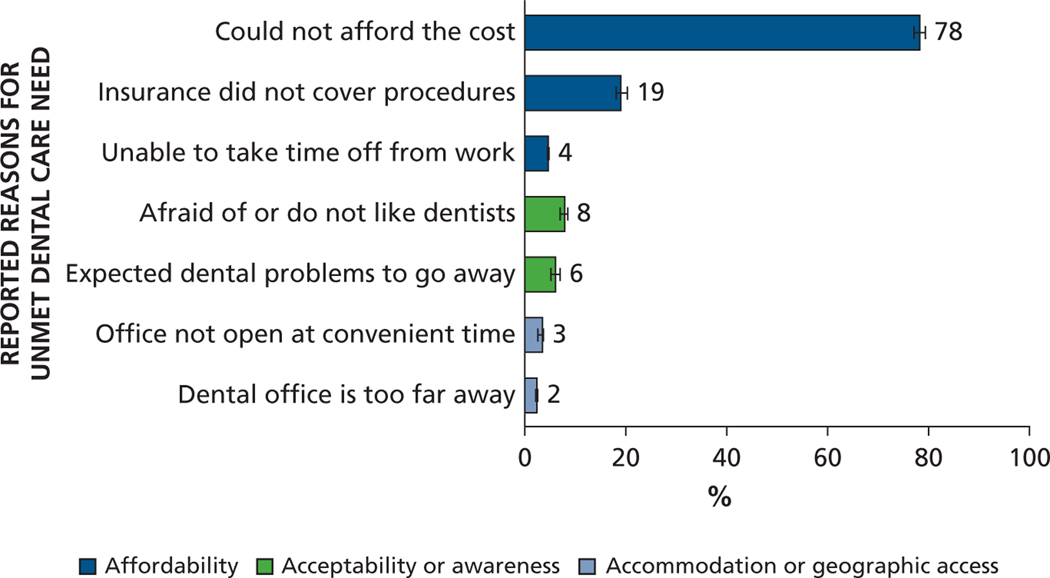

Among adults who reported unmet oral health care need, the most frequently cited reasons for being unable to obtain care were financial (Figure)12—inability to afford cost (78%) and no insurance coverage (19%). Other reasons included fear of dentists (8%), expected dental problems to go away (6%), and inability to take time off from work (4%).

Figure.

Estimated percentage of working-age US adults reporting unmet oral health care needs due to affordability, acceptability or awareness, and accommodation or geographic access. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.12

Model-adjusted unmet oral health care need

In the adjusted model, the variables most strongly associated (highest RR and risk difference and statistically significant at P < .05 in Table 3) with reporting an unmet oral health care need were related to health and financial access.12 For example, the prevalence of reporting an unmet oral health care need increased with UC severity for both income groups. Among higher-income adults, unmet oral health care need prevalence increased from 10.0% among adults with no UC to 25.4% among adults with mild to moderate UC and 38.1% among adults with severe UC. Thus, among higher-income adults with mild to moderate and severe UC, unmet oral health care need prevalence was more than 2 times (RR, 2.54) and 3 times (RR, 3.81) as high, respectively, relative to adults with no UC (RR not shown in Table 3). Alternatively, mild to moderate and severe UC were associated with an increased prevalence of 15.4% (risk difference, 25.4%−10%) and 28.1% (risk difference not shown in Table 3), respectively, among higher-income adults. Compared with adults with private health insurance, the prevalence of unmet oral health care need was 1.48 (RR from Table 3) and 2.13 times higher among adults with public or no health insurance, respectively. Thus, having public or no health insurance was associated with a 6.9% (risk difference from Table 3) and 16.3% increase, respectively, of reporting an unmet oral health care need. The RRs and risk differences were also notably high among adults who smoked (past or current) compared with never smoked and reported fair or poor general health compared with good or better health. We also found that the association between reporting an unmet oral health care need and no or mild to moderate UC varied by income. Compared with higher-income adults with no and mild to moderate UC, unmet oral health care need prevalence among low-income adults with similar UC was 2.20 (RR in Table 3) and 1.41 times higher, respectively. We did not detect a difference in reporting an unmet oral health care need by income among people with severe UC.

Table 3.

Risk ratio and risk difference in reporting unmet oral health care need obtained from multivariable logistic regression, US adults aged 20–64 years.*

| CHARACTERISTIC | RISK, % (STANDARD ERROR) | RISK RATIO, % (95% CONFIDENCE INTERVAL) | RISK DIFFERENCE, % (95% CONFIDENCE INTERVAL) | P VALUE† FOR RISK DIFFERENCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined Effect of Income and Untreated Caries Severity | ||||

| 0 teeth with untreated caries | ||||

| < 200% FPG‡ | 22.0 (1.1) | 2.20 (1.88 to 2.58) | 12.0 (9.6 to14.4) | < .001 |

| ≥ 200% FPG [Reference] | 10.0 (0.6) | |||

| 1–3 teeth with untreated caries§ | ||||

| < 200% FPG | 35.7 (1.5) | 1.41 (1.16 to 1.71) | 10.3 (5.0 to 15.6) | < .001 |

| ≥ 200% FPG [Reference] | 25.4 (2.1) | |||

| ≥ 4 teeth with untreated caries¶ | ||||

| <200% FPG | 45.1 (2.5) | 1.18 (0.97 to 1.45) | 7.0 (−1.0 to 15.0) | .092 |

| ≥ 200% FPG [Reference] | 38.1 (3.2) | |||

| Age, y | ||||

| 20–34 | 20.3 (0.7) | 1.01 (0.89 to 1.14) | 0.1 (−0.3 to 0.8) | .929 |

| 35–49 | 19.5 (1.0) | 0.97 (0.84 to 1.11) | −0.7 (−1.1 to −0.3) | .625 |

| 50–64 [Reference] | 20.2 (1.1) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male [Reference] | 18.2 (0.8) | |||

| Female | 21.9 (1.0) | 1.21 (1.09 to 1.33) | 3.7 (3.4 to 3.9) | < .001 |

| Race or Ethnicity# | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic [Reference] | 19.3 (0.8) | |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 21.4 (0.7) | 1.10 (0.99 to 1.23) | 2.0 (0.0 to 4.0) | .058 |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 15.4 (1.0) | 0.80 (0.69 to 0.91) | −3.9 (−6.3 to −1.5) | .001 |

| Hispanic | 22.0 (1.2) | 1.14 (0.99 to 1.29) | 2.7 (−1.1 to 5.3) | .061 |

| Education level | ||||

| < High school | 20.2 (1.2) | 1.00 (0.89 to 1.12) | 0 (−2.4 to 2.4) | .998 |

| High school or equivalent | 19.5 (1.0) | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.07) | −0.7 (−2.9 to 1.5) | .498 |

| ≥ High school [Reference] | 20.2 (0.8) | |||

| Health Insurance Coverage | ||||

| Private coverage [Reference] | 14.4 (0.6) | |||

| Public or other coverage | 21.3 (1.2) | 1.48 (1.31 to 1.67) | 6.9 (4.5 to 9.3) | < .001 |

| No coverage of any type | 30.7 (1.1) | 2.13 (1.91 to 2.38) | 16.3 (13.9 to 18.7) | < .001 |

| Self-Reported General Health | ||||

| Excellent, very good, good [Reference] | 18.8 (0.7) | |||

| Fair, poor | 24.9 (1.1) | 1.33 (1.20 to 1.46) | 6.1 (3.9 to 8.3) | < .001 |

| Smoking Status | ||||

| Never [Reference] | 17.0 (0.7) | |||

| Current smoker | 24.4 (1.3) | 1.44 (1.29 to 1.62) | 7.4 (4.9 to 9.9) | < .001 |

| Former smoker | 22.7 (1.2) | 1.34 (1.20 to 1.49) | 5.7 (3.5 to 7.9) | < .001 |

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.12

Significant at P < .05.

FPG: Federal poverty guidelines.

Mild to moderate untreated caries.

Severe untreated caries.

366 respondents in the Race or Ethnicity category were excluded from the study.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of mild to moderate and severe UC was 17.8% and 7.2%, respectively, among adults aged 20 through 64 years. Adults likely to have financial barriers in accessing oral health care (that is, low income or uninsured) had mild to moderate UC 2 times more frequently and severe UC 3 times more frequently than adults likely to not have financial barriers (that is, higher income or privately insured). Among adults with UC, the mean number of affected teeth was also higher for adults likely to have financial barriers.

After controlling for covariates, we found that UC severity, other health factors, and factors related to financial access were the variables most strongly associated with reporting an unmet oral health care need. The only sociodemographic variables associated with reporting an unmet oral health care need were being Asian (protective) or female.

Similar to 2 other studies,14,18 sensitivity (the proportion of adults with UC reporting unmet oral health care need) in our study was low—36.6% and 52.2% for adults with mild to moderate and severe UC, respectively. Data on self-reported unmet oral health care need, however, may still have utility for targeting resources. For example, an oral health care program with no targeting criteria would see 17.8 mild to moderate and 7.2 severe UC cases per 100 patients, on average. Targeting services to adults reporting unmet oral health care needs would increase the number of mild to moderate cases by 82% ([32.4 – 17.8]/17.8 × 100, from Table 1) to 32.4 per 100 patients and the number of severe cases by 159.7% to 18.7 per 100 patients.

We also found that the association between UC severity and reporting an unmet oral health care need varied by income. As the question analyzed in our study measured both dental health status and access, our finding that among adults with mild to moderate UC, those with low income (proxy for financial access) more frequently reported not being able to obtain needed oral health care was not surprising. Our findings that differences in reporting an unmet oral health care need between low- and higher-income adults were not significant for adults with severe UC and significant for adults with no UC, however, were unexpected. It is possible that higher-income adults with severe UC were more likely to confront access barriers not included in our model (for example, living in rural area or not having dental insurance). Similarly, not including dental conditions other than caries that are more prevalent among low-income adults (for example, periodontitis) in our model could explain why low-income adults with no UC were more likely to report an unmet oral health care need. This finding, however, could also be due to reporting heterogeneity by income. Some studies examining the association between self-reported health and health status have found that lower-income adults tend to be more pessimistic in reporting their health status and higher-income adults more optimistic.19,20

The primary reason for reporting an unmet oral health care need was affordability. At present, there is a limited oral health care safety net.10 Although the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act expanded eligibility for Medicaid health care coverage to adults with income up to 138% of the FPG, adult dental coverage is optional, and states can elect not to provide it.21 Of the 37 states that had expanded Medicaid as of January 2018, 24 states offer dental services beyond emergency care for the Medicaid expansion population.22 When faced with budget constraints, some states have reduced or altogether eliminated Medicaid dental benefits.23–25 Efforts such as the federal funding of $156 million in 2016 to health centers have been made to increase integrated oral health services and the capacity of dental safety nets.23 States could consider providing Medicaid coverage for dental benefits beyond emergency services (for example, preventive and restorative treatment), which previous studies have shown increases the likelihood of having a dental visit.23,25 Such visits could help prevent the initiation and progression of caries or other dental diseases and reduce the burden of prolonged unmet oral health care needs, which have been shown to lead to more expensive and often nondefinitive treatment in hospital emergency department settings.23,25,26 Medical-dental integration and other innovative models such as partnership between private dentists and federally qualified health centers can improve access to oral health services.27 Continued pursuit of these strategies may be an option for jurisdictions to consider.

Limitations

NHANES did not have information on dental insurance coverage. Among higher-income adults, those with health insurance may not have had dental insurance. This would also hold for low-income adults, as comprehensive dental services are covered by Medicaid in only 16 states and the District of Columbia.22 In addition, we did not include measures of periodontal disease and other conditions such as partial tooth loss or orthodontic needs, which could result in dental esthetic or functional concerns. Although NHANES does include information on periodontitis for adults 30 years or older, we did not include this information because it would have excluded a large number of younger working-aged adults—the segment of our study sample with the highest prevalence of UC and self-reported unmet oral health care need (adults aged 20–34 years). Including smoking status may have mitigated the omission of the periodontitis variables, as approximately 62% of periodontitis cases are among current smokers and 46% among former smokers.28 Also, many of the explanatory variables in our analysis were self-reported and thus may have been subject to social desirability bias. Finally, although we included age in our multivariable analysis, we did not include interaction terms between age and other explanatory variables that may have varied by age. For example, the effect of household income could have varied owing to factors such as older workers’ being more likely to have dental benefits or younger adults’ spending income instead on their children’s oral health care needs.

CONCLUSIONS

Working-aged adults with financial barriers to oral health care experience a disproportionate burden of UC. A multivariable analysis indicates that self-reported unmet oral health care need appears to largely be capturing the effects of dental disease and financial access barriers. This question could be useful in targeting resources to decrease UC prevalence among adults lacking access to oral health care. ■

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mei Lin and Dr. Scott M. Presson for their support in development of the study protocol plan of analysis and project development.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

ABBREVIATION KEY

- FPG

Federal poverty guidelines

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- UC

Untreated caries

Footnotes

Disclosure. None of the authors reported any disclosures.

Contributor Information

Shanele Williams, Division of Oral Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.

Liang Wei, DB Consulting Group, Atlanta, GA..

Susan O. Griffin, Division of Oral Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA..

Gina Thornton-Evans, Division of Oral Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 4770 Buford Hwy, MS S107-8, Atlanta, GA 30341-3717.

References

- 1.Medical expenditure panel survey: MEPSnet/HC trend query. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/MEPSnetHC/startup. Accessed May 30, 2017.

- 2.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020: Oral Health—OH-7 increase the proportion of children, adolescents, and adults who used the oral health care system in the past year. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data-search/Search-the-Data#objid=5028. Accessed February 11, 2017.

- 3.Vujicic M, Buchmueller T, Klein R. Dental care presents the highest level of financial barriers, compared to other types of health care services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(12):2176–2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis C, Lynch H, Johnston B. Dental complaints in emergency departments: a national perspective. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(1):93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wall T. Recent trends in dental emergency department visits in the United States: 1997/1998 to 2007/2008. J Public Health Dent. 2012;72(3):216–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelekar U, Naavaal S. Hours lost to planned and unplanned dental visits among US adults. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:E04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine. Advancing Oral Health in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moeller JF, Chen H, Manski RJ. Investing in preventive dental care for the Medicare population: a preliminary analysis. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11): 2262–2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. Improving Access to Oral Health Care for Vulnerable and Underserved Populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Questionnaire Sections: Search Results—Access to Care. Available at: https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/survey_comp/survey_results_ques_sections.jsp?Section=AC&Year1=AllYear&Submit22=Submit. Accessed September 6, 2017.

- 12.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, NHANES Questionnaires, Datasets, and Related Documentation. Available at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx. Accessed November 2, 2020.

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey: Tables of Summary Health Statistics Keyword = dental care. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/shs/tables.htm. Accessed September 6, 2017.

- 14.Heft MW, Gilbert GH, Shelton BJ, Duncan RP. Relationship of dental status, sociodemographic status, and oral symptoms to perceived need for dental care. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(5):351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malecki K, Wisk LE, Walsh M, McWilliams C, Eggers S, Olson M. Oral health equity and unmet dental care needs in a population-based sample: findings from the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 3):S466–S474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES): Oral Health Examiners Manual. Available at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2011-2012/manuals/Oral_Health_Examiners_Manual.pdf. Accessed November 2, 2020.

- 17.Saurman E. Improving access: modifying Penchansky and Thomas’s Theory of Access. Health Serv Res Policy. 2016;21(1):36–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farmer J, Ramraj C, Azarpazhooh A, Dempster L, Ravaghi V, Quiñonez C. Comparing self-reported and clinically diagnosed unmet dental treatment needs using a nationally representative survey. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77(4):295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Etile F, Milcent C. Income-related reporting heterogeneity in self-assessed health: evidence from France. Health Econ. 2006;15(9):965–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Humphries KH, van Doorslaer E. Income-related health inequality in Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(5):663–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaiser Family Foundation. State Health Facts: Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. 2019. Available at: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Accessed April 8, 2019.

- 22.Center for Health Care Strategies, Medicaid adult dental benefits: an overview. Available at: https://www.chcs.org/media/Adult-Oral-Health-Fact-Sheet_011618.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2018.

- 23.Singhal A, Damiano P, Sabik L. Medicaid adult dental benefits increase use of dental care, but impact of expansion on dental services use was mixed. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(4):723–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wall T, Nasseh K, Vujicic M. Most important barriers to dental care are financial, not supply related, 2014b, Health Policy Institute Research Brief, Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singhal A, Caplan DJ, Jones MP, et al. Eliminating Medicaid adult dental coverage in California led to increased dental emergency visits and associated costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(5):749-http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0002-8177(20)30672-3/sref25756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okunseri C, Pajewski NM, Brousseau DC, Tomany-Korman S, Snyder A, Flores G. Racial and ethnic disparities in nontraumatic dental-condition visits to emergency departments and physician offices: a study of the Wisconsin Medicaid program. JADA. 2008;139(12): 1657–1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hummel J, Phillips K, Holt B, Hayes C. Oral health: an essential component of primary care. Available at: http://www.safetynetmedicalhome.org/resources-tools/white-papers. Accessed October 7, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eke PI, Thornton-Evans GO, Wei L, Borgnakke WS, Dye BA, Genco RJ. Periodontitis in US Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–2014. JADA. 2018;149(7):576–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]