Abstract

Variation in flower color due to transgenerational plasticity could stem directly from abiotic or biotic environmental conditions. Finding a link between biotic ecological interactions across generations and plasticity in flower color would indicate that transgenerational effects of ecological interactions, such as herbivory, might be involved in flower color evolution. We conducted controlled experiments across four generations of wild radish (Raphanus sativus, Brassicaceae) plants to explore whether flower color is influenced by herbivory, and to determine whether flower color is associated with transgenerational chromatin modifications. We found transgenerational effects of herbivory on flower color, partly related to chromatin modifications. Given the presence of herbivory in plant populations worldwide, our results are of broad significance and contribute to our understanding of flower color evolution.

Keywords: flower color, methylation, transgenerational plasticity, herbivory, anthocyanins, chromatin modifications, Brassicaceae

Introduction

Flower color is a key trait in angiosperm evolution. It is one of the most conspicuous traits under natural selection because of its potential role in attracting pollinators, and the subsequent influence on reproductive fitness (Spaethe et al., 2001; Wester and Lunau, 2017). Flower color is commonly related to quality or quantity of floral rewards, such as nectar or pollen (Fenster et al., 2004; Rausher, 2008). This relationship opens up the possibility of evolutionary diversification driven by pollinators acting on flower color variation within a species (Gegear and Burns, 2007; Losada et al., 2015; Sobral et al., 2015; Narbona et al., 2018).

Color in flowers is mainly due to the presence of pigments (Van Der Kooi et al., 2019). Among plant pigments, flavonoids—specifically anthocyanins—are the most common and diverse type (Tanaka et al., 2008). However, besides pollinator attraction, anthocyanins, and other groups of flavonoids that share a common biosynthetic pathway, may act as deterrents or defensive compounds against floral antagonists (Lev-Yadun and Gould, 2008; Zhang et al., 2013). Thus, herbivores, seed predators, and pathogens could also play an important role as non-pollinator agents of selection in flower color (Strauss and Whittall, 2006; Veiga et al., 2015). In addition, abiotic factors may also shape flower color variation (Dalrymple et al., 2020).

Flower color polymorphism within a species occurs when more than one flower color morph is present among individuals in the same or different populations (Warren and Mackenzie, 2001; Narbona et al., 2018). Causes of flower color polymorphism include different selection pressures imposed by mutualistic pollinators, antagonistic herbivores, or pathogens (Veiga et al., 2015; Narbona et al., 2018). This process is supposed to require the establishment and maintenance of a flower color mutant genotype in the population (Sobel et al., 2010; Del Valle et al., 2019) with the flower color variation based on the downregulation of structural or regulatory genes of the biosynthetic pathway of pigments accumulated in flowers (Sobel and Streisfeld, 2013; Roberts and Roalson, 2017). Thus, flower color polymorphism is expected to involve changes in nucleotide sequence that are transmitted to subsequent generations. Recently, it has been found that a radical change in flower morphology, including petal color, in Moricandia arvensis is due to within-individual plasticity produced by seasonal changes in climatic conditions (Gómez et al., 2020). A transcriptomic analysis found a coordinated response of more than 600 genes that was differentially expressed between two types of flowers suggesting a genetic basis for this plastic response (Gómez et al., 2020; see also Laitinen and Nikoloski, 2019).

As flower color is a trait highly affected by evolutionary constraints due to the influence of pollinator and non-pollinator agents of selection (Schiestl and Johnson, 2013; Sletvold et al., 2016), plasticity in flower color is expected to be low in comparison with other floral and vegetative traits (Del Valle et al., 2018, 2019; but see Gómez et al., 2020). However, flower color may show some degree of plasticity in response to abiotic as well as to biotic stressors, such as herbivores or pathogens (Wang et al., 2017; Rusman et al., 2019b; Koski and Galloway, 2020). Beyond this within-generational plasticity, it is not yet known whether there are possible transgenerational plastic effects of herbivory on flower color. In other words, we do not know if flower color plasticity is influenced by herbivory events across generations. Exploring whether the ecological experiences of previous generations, such as herbivory, influence flower color may contribute to our understanding of flower color evolution.

Transgenerational phenotypic plasticity challenges our current knowledge of evolutionary processes. Environmental factors can modify phenotypes directly via epigenetic modifications (Jablonka and Raz, 2009) that are transmissible across generations and can be adaptive (Jablonka and Raz, 2009; Herman and Sultan, 2016). Such phenotypic modifications can be manifested in a variety of ecologically relevant traits (Bossdorf et al., 2010), including the induction of defenses against herbivores (Herrera and Bazaga, 2013), and with subsequent effects on plant fitness (Herrera et al., 2014), at least partially independent of genetic variation (Verhoeven et al., 2010). Natural selection could act on this variation through its effect on ecological interactions that in turn affect fitness (Bossdorf et al., 2008; Alonso et al., 2019). In this way, transgenerational plasticity can influence the course of evolution (Bonduriansky and Day, 2009). Despite recent discoveries about the ecological and evolutionary implications of transgenerational effects (Verhoeven et al., 2016; Colicchio and Herman, 2020), transgenerational consequences of herbivory on flower color have not yet, to our knowledge, been explored.

We conducted controlled experiments with the wild radish (Raphanus sativus L.) across four generations. This annual species shows a petal color polymorphism (Figure 1, white, pink, yellow, and bronze) due to the independent absence and presence of anthocyanins and carotenoids (Strauss et al., 2004; Strauss and Whittall, 2006). Here, we explore how the presence of petal anthocyanins across generations depends on herbivory by caterpillars of a specialized herbivore and whether such phenotypic changes are associated with chromatin modifications (i.e., genome-wide methylation).

FIGURE 1.

Raphanus sativus plants showing flower color polymorphism. (A) purple-flowered plants with anthocyanins present in petals. (B) White-flowered plants lacking anthocyanin in petals.

Materials and Methods

Study Organisms

In California, wild radish, Raphanus sativus L. (Brassicaceae) is a naturalized, self-incompatible, herbaceous annual weed that grows along coastal sites, roadsides, and agricultural fields (Campbell and Snow, 2009). Wild radish has a flower color polymorphism that is driven by the presence or absence of anthocyanins (A) and carotenoids (C), with individuals showing either bronze (A+, C+), purple (A+, C−), yellow (A−, C+), or white (A−, C−) flowers (Irwin and Strauss, 2005). The inheritance of the pigments is Mendelian with two independently assorting loci coding for presence of anthocyanin and carotenoids (Irwin and Strauss, 2005).

Seeds germinate in October through November, and plants bloom in March for a period of 3–4 months. A wide variety of herbivores (aphids, snails, slugs, flea beetles, caterpillars, rabbits, and deer) feed on R. sativus. Prominent among these herbivores is the larval stage of the white cabbage butterfly, Pieris rapae, which was used for the herbivory treatments in this study. White cabbage butterfly caterpillars are specific herbivores to the Brassicaceae family.

Experimental Design

We raised four generations of offspring from a single maternal family displaying white flowers collected from the wild in California. One maternal family (P) was raised in the greenhouse where they experienced no herbivory. After that, three generations (F1, F2, and F3) were raised. The plants used in this study are all descended from half siblings. To test our hypothesis, it was important to control for genetic variation so that any potential epigenetic or plastic mechanisms found could be interpreted and, at least partially, treated independently from genetic variation.

For all generations, we subjected plants to one of two treatments: herbivory or control (non-herbivory). We used a fully crossed, factorial experimental design, where the first factor was the exposure to herbivory in the F1 generation, the second was exposure in the F2 generation, and a third was exposure to herbivory in the F3 generation. In this way our F3 generation consisted of 130 plants in eight groups (between 12 and 22 plants per group) 68 of them with mothers attacked by herbivores and 62 of them with mothers not exposed to herbivores. This design enabled us to study the effect of herbivory across generations on subsequent flower color.

Plants were grown in germination flats in a greenhouse at the Stanford University Greenhouse Facility. We used a soil mix of 5% fine white sand, 20% potting soil and 75% peat moss (Orchard Supply Hardware, San Jose, CA, United States). Two weeks after germination, seedlings were transferred to 0.8-L pots. Plants were watered once a day and maintained at a 26°C/21°C, under a 12 h/12 h cycle. At the beginning of the experiment, the plants had two leaves. The caterpillars used were all second or third instar. The experiment lasted 2 weeks, until larvae started pupation. The amount of leaf tissue eaten was about 60% of the total leaf area on average but ranged from 40 to 80%. The caterpillars heavily attacked the plants and the plants quickly grew new leaf tissue in response. No plants were killed by the effects of herbivory. The caterpillars were purchased and shipped from Carolina Biological Company (CBC) and were delivered in small plastic containers with five to six larvae per container, and an agar and wheat-based food medium provided ad libitum. Caterpillars arrived during their second or third instar and were used in the experiments immediately upon arrival. Two Pieris rapae caterpillars were placed on the leaves of each plant in the herbivory treatment and allowed to roam around the plant freely for 2 weeks.

The herbivory treatment lasted for about the first quarter of the plants’ life. Plants germinated after 4 or 5 days of sowing the seeds, they flowered around 45 days later, and ended life with mature seeds at 2 months. Pollination was performed by hand with makeup brushes. In each generation, plants from the same treatment were crossed. We collected pollen with the brush from all plants per group and we pollinated all plants within the same group. For the F3 generation, four groups with 24 to 44 plants per group depending on the F1 and F2 treatment combination, were used. The goal was to pollinate all flowers on each plant. Several seeds per plant were sown and when all plants had germinated seeds, one seedling from each mother was selected using seedlings with similar sizes for all plants. We did not observe any plants with bronze flowers, and yellow forms were rare; thus, we focused on the production of anthocyanins (and we did not study carotenoid plasticity). Petal color of individuals was visually recorded as purple or white (i.e., presence or absence of petal anthocyanins, respectively; Figure 1). Biochemical analysis of white petals of R. sativus performed with HPLC-DAD showed absence of anthocyanins (E. Narbona et al. unpublished results).

Chromatin Analyses

We collected leaf material from F2 generation plants before and after treatment. Plants were harvested at approximately 1 week of age before the treatment, and again at 3 weeks of age after the treatment. Plants had two or three leaves in the first sampling and between 5 and 10 leaves in the second sampling. Only fresh leaves that had recently expanded were sampled. We cut out one 2.7 cm diameter disc with a cork borer from a leaf, and leaf material was kept in dry silica gel until DNA extraction. The epigenetic characterization of the individuals before and after the treatment was made by means of methylation sensitive amplification fragment length polymorphism. In this technique, genomic DNA is digested by methylation-sensitive enzymes providing an epigenetic fingerprint for the plants.

We were interested in detecting DNA methylation events experienced by individual genotypes (and not on methylation differences between genotypes). Thus, a simplified MSAP method was performed using only primer combinations with the methylation-sensitive HpaII. HpaII cleaves CCGG sequences when cytosines are not methylated. Cleaving may be impaired when at least one cytosine is hemi-methylated and this process is inactive if one (or both) of the cytosines are fully methylated (Herrera et al., 2012). Thus, within the same genotype, polymorphism of MSAP markers reflects variation in the methylation status of the CCGG sites. The change from presence to absence implies a methylation event in a locus, and the change from absence to presence implies a de-methylation event (see Herrera et al., 2012 for an application of this simplified MSAP method).

DNA was isolated using the hexadecyl-trimethyl-ammonium-bromide procedure. After that, MSAFLP fingerprinting was performed. We first performed a pilot study with 15 individuals (30 samples) and 6 primer combinations. Based on this approach, we analyzed 106 samples of 53 plants belonging to the F2 generation using 2 primer combinations. The selected combinations X-AC/M-AC and X-AC/M-ATC were used for fragment amplification. MS-AFLP analyses were carried out by Keygene Laboratories (Netherlands).

Statistical Analyses

Transgenerational Effects of Herbivory on Flower Color

A generalized linear model (binomial error distribution, link logit) for the 130 plants from F3 was performed to relate the anthocyanin presence (with or without anthocyanin) to the herbivory treatment in F1, F2, and F3 generations. We additionally tested this model including two- and three-way interactions among generation treatments. An alternative model was tested in which the fixed factors included the number of herbivory events across generations and the order of the herbivory treatments across generations (nested in number of herbivory events). All models were compared by means of AICc criterion and the model which presented the best fit included exclusively the herbivory treatment in each generation.

Transgenerational Effects of Maternal Methylation on Flower Color

Only fragments >300 base pairs in size were considered to reduce the potential impact of size homoplasy (Vekemans et al., 2002). Methylation and de-methylation cannot occur at the same time. Therefore, we considered non-methylation events only when de-methylation did not occur on the marker. MSAP marker scores for samples were transformed by comparing with the corresponding values (i.e., same plant individual before the treatment). MSAP marker scores involving a change from 1 to 0 denoted a methylation event of the marker involved. A new sample (N = 53 plant individuals) by marker (N = 402) score matrix was obtained where each element denoted whether the sample involved had experienced a methylation event (score = 1) or not (score = 0) in the corresponding marker (or missing when a de-methylation event occurred or when loci were already methylated before the treatment and therefore a methylation event was not possible). We assessed the genome-wide methylation per individual as the percentage of methylation events occurring per individual during treatment.

To understand the potential mechanism of transgenerational plasticity in flower color, we analyzed how methylation in F2 plants affected flower color in the F3 generation. A generalized linear model (binomial error distribution, link logit) for the response variable anthocyanin presence or absence (1/0) in the F3 generation was performed to relate this pigment presence to the global methylation of their mothers during treatments (fixed covariate included in the model). We tested alternative models in which herbivory treatments across generations were also included either independently or as the number of inductions in the ancestry line and we selected the model in which only the covariate methylation was included based on the AICc criterion.

Statistical analyses were performed in RStudio for R version 4.0.2 (R Core Team, 2013). Models were fitted using the function glm from the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015). Statistical significance of fixed effects was determined by analysis of deviance, Type II Wald chi-square tests using the ANOVA function from the car package and the function AICc from the AICcmodavg package.

Results

Transgenerational Effects of Herbivory on Flower Color

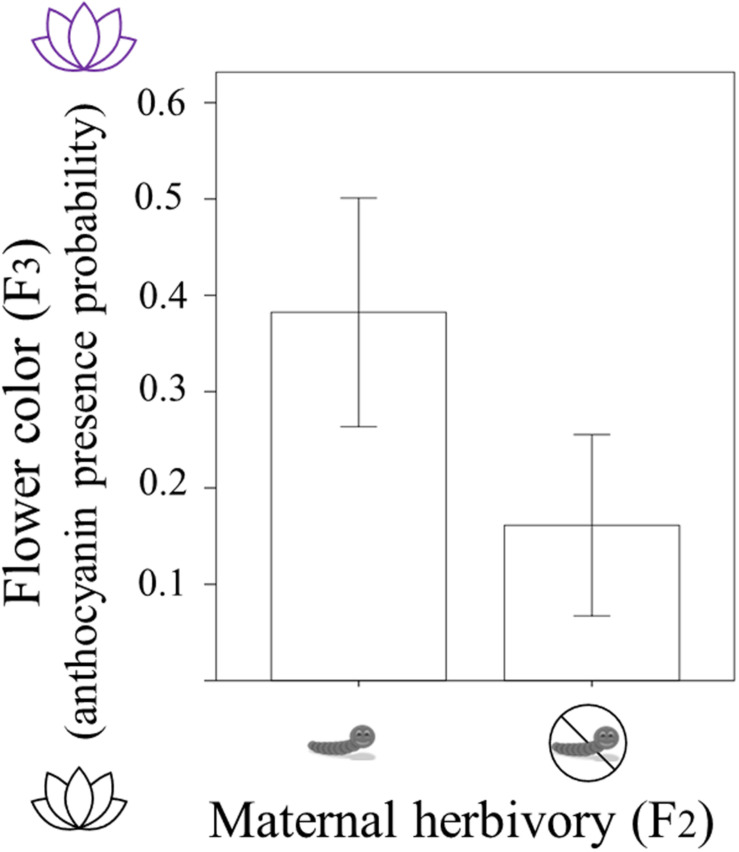

In F3 plants, 94 individuals had white flowers (without anthocyanins) and 36 individuals had pink/purple flowers (with anthocyanins). The presence/absence of anthocyanins in these 130 (F3) individuals was related to the maternal herbivory treatment (Table 1). Plants were more likely to present purple flowers (with anthocyanins) when their mothers had suffered herbivory. The probability of producing petal anthocyanins was around 16% in plants coming from mothers who experienced no herbivory whereas it was around 38% in plants whose mothers were attacked by herbivores (Table 1 and Figure 2). Current and grandmaternal herbivory were not related to flower color and the interactions between generation treatments were not retained in the model (and non-significant).

TABLE 1.

Results of the generalized linear model analyzing flower color (probability of F3 individuals containing anthocyanin in their petals) as a function of the herbivory in F1, F2, and F3 generations.

| Response variable | Estimate | s.e. | z-value | P-value | |

| Current herbivory | –0.329 | 0.407 | –0.809 | 0.418 | |

| Flower color in F3 | Maternal herbivory | –1.139 | 0.4316 | –2.641 | 0.008 |

| (anthocyanin presence) | Grandmaternal herbivory | 0.235 | 0.421 | 0.558 | 0.577 |

Significant P-values are highlighted in bold.

FIGURE 2.

Flower color of Raphanus sativus F3 plants (with white flowers having no anthocyanins and purple flowers presenting anthocyanin; y-axis) depending on whether their mothers experienced herbivory by caterpillars (maternal herbivory in F2; x-axis). Difference is statistically significant (P < 0.01) and bars correspond to two standard errors.

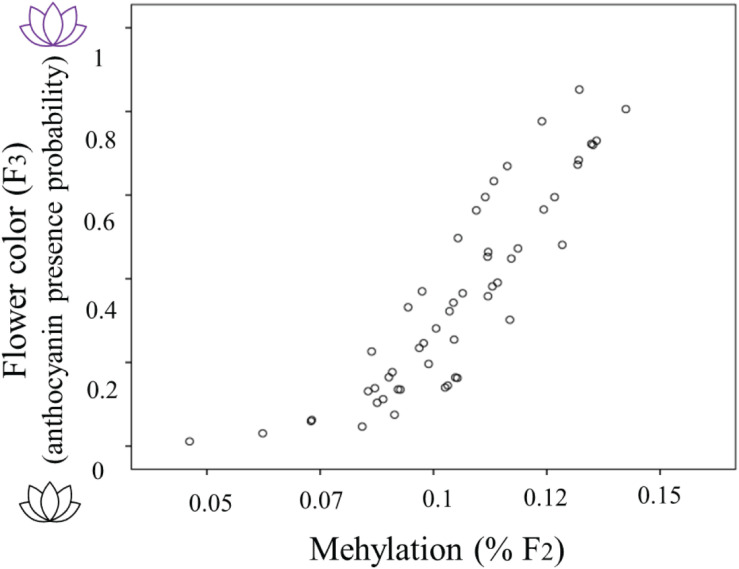

Transgenerational Effects of Maternal Methylation on Flower Color

The occurrence of methylation during the 2-week herbivory/non-herbivory treatment ranged from 5 to 14% of genome wide loci. The presence of anthocyanin in plants from the F3 generation was related to the percent genome-wide methylation of their mothers (Estimate 61.069, s.e. 21.127, Z = 2.891, P = 0.004). Global genome-wide cytosine methylation of F2 plants was positively related to the probability anthocyanins presence in their offspring (Figure 3). The model which included herbivory across generations and methylation in F2 performed worst in terms of AICc score, thus it is not presented. When including simultaneously both F2 methylation and maternal herbivory, the latter was not significant.

FIGURE 3.

The relationship between flower color of Raphanus sativus F3 plants (purple flowers producing anthocyanins and white flowers lacking anthocyanins) with the genome wide percent methylation in their F2 mothers. Flower color is estimated as the predicted probability of anthocyanin presence from the saturated model including herbivory treatments and methylation (see “Statistical Analyses” section for details).

Discussion

Within-generational plasticity in flower color as well as the role of epigenetic inheritance in flower color variation have been recently reported (Gómez et al., 2020; Han et al., 2020). However, little work has focused on the possible transgenerational nature of plasticity in flower color and its potential eco-evolutionary causes. Here, we show that flower color may be linked to the herbivory, and methylation, in the previous generation. Flower color is not only a trait affected by the biotic and abiotic environment through natural selection and plasticity (Rusman et al., 2019a; Dalrymple et al., 2020), but our results indicate that flower color variation, at least in some cases, may be related to herbivory induced transgenerational plasticity.

Our results also indicate that this transgenerational effect of herbivory on flower color in R. sativus may be related to chromatin modifications. Although there are some reports of epigenetic inheritance involved in flower color modification in ornamental plants (Deng et al., 2015; Morita and Hoshino, 2018), this phenomenon has remained virtually unknown in wild plants, with some exceptional, related instances. For example, it has been recently proposed that epigenetic regulation of anthocyanin production may take place under stress-induced conditions in leaves of Arabidopsis and poplar (Fan et al., 2018; Cai et al., 2019). The regulation of the expression of a set of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes is mediated thorough the SWR1 ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complex (Cai et al., 2019). The anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway in floral and foliar tissues shares the same structural genes, and differs only in the identity of transcriptional regulators (Hichri et al., 2011; Albert et al., 2014), opening up the possibility that a similar epigenetic process to that found in Arabidopsis and poplar could be acting in R. sativus. In fact, changes in methylation levels in an anthocyanin biosynthesis transcription factor have been recently found in petals of Malus halliana during flower color fading (Han et al., 2020).

Herbivory had previously been shown to relate to flower coloration, but this result was interpreted as defense traits pleiotropically linked to flower color morph because of the relationship between glucosinolates and the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway (Strauss et al., 2004; Strauss and Whittall, 2006). Here we find that this relationship may be due to anthocyanins and flower color being plastic themselves, and responding to the same stimulus as plant defenses, expanding our previous understanding of this process. A possible interpretation of our results is that glucosinolates are upregulated in a transgenerational way, and anthocyanins are therefore indirectly induced by herbivory. In addition, anthocyanins share biosynthetic pathway with other flavonoids with well-known functions in plant defense, such as isoflavonoids, flavones, flavonols, and proanthocyanidins (Gould and Lister, 2006). This opens up the possibility that an upregulation of plant defense flavonoids in flowers may pleiotropically increase anthocyanin production due to their common biosynthetic origin (Johnson et al., 2015).

The ecological significance of the increase in probability to produce purple flowers lies in the complex pattern of mutualistic and antagonistic interactions this species shows. For example, pollinators, primarily honeybees, prefer to visit flowers of R. sativus with an absence of anthocyanin (white and yellow) (Stanton, 1987; Irwin and Strauss, 2005). Additionally, it has been found that herbivore damage in R. sativus can induce resistance to florivores in petals. Florivores prefer petals from plants which have not been previously attacked, but this difference is only noticeable in anthocyanin free plants (McCall et al., 2018). We have previously reported (Neylan et al., 2018) that the number of herbivory events across generations affected plant palatability to generalist slugs, but not to specialized caterpillars. Flower color variation seems therefore to be related to transgenerational effects of herbivory and plant and flower palatability (McCall et al., 2018; Neylan et al., 2018). The ecological implications of these multi-generational, multi-faceted effects may affect not only the response-inducing antagonists (herbivores) but mutualists as well, with complex and far-reaching consequences at both the population and community level (Jacobsen and Raguso, 2018; Rusman et al., 2019b; Kessler and Chautá, 2020).

The consequences of transgenerational plasticity through shared pathways and potential pleiotropies with traits that affect reproductive capabilities in offspring, remain understudied but potentially significant (Lehto and Tinghitella, 2020). Our work suggests transgenerational effects of herbivory, related to epigenetic modifications, on flower color variation within a species, improving our understanding of flower color evolutionary processes.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Author Contributions

MS and RD designed the study. MS and IN analyzed the data and performed the experimental work. MS and EN wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the revisions.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. Funding for this research was provided by Stanford University, United States (RD unrestricted funds). MS was a beneficiary from the I2C program, Xunta de Galicia, Spain while writing this manuscript.

References

- Albert N. W., Davies K. M., Lewis D. H., Zhang H., Montefiori M., Brendolise C., et al. (2014). A conserved network of transcriptional activators and repressors regulates anthocyanin pigmentation in Eudicots. Plant Cell 26 962–980. 10.1105/tpc.113.122069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso C., Ramos-Cruz D., Becker C. (2019). The role of plant epigenetics in biotic interactions. New Phytol. 221 731–737. 10.1111/nph.15408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67 1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonduriansky R., Day T. (2009). Nongenetic inheritance and its evolutionary implications. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 40 103–125. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173441 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bossdorf O., Arcuri D., Richards C. L., Pigliucci M. (2010). Experimental alteration of DNA methylation affects the phenotypic plasticity of ecologically relevant traits in Arabidopsis thaliana. Evol. Ecol. 24 541–553. 10.1007/s10682-010-9372-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bossdorf O., Richards C. L., Pigliucci M. (2008). Epigenetics for ecologists. Ecol. Lett. 11 106–115. 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01130.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H., Zhang M., Chai M., He Q., Huang X., Zhao L., et al. (2019). Epigenetic regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis by an antagonistic interaction between H2A.Z and H3K4me3. New Phytol. 221 295–308. 10.1111/nph.15306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L. G., Snow A. A. (2009). Can feral weeds evolve from cultivated radish (Raphanus sativus, Brassicaceae)?. Am. J. Bot. 96 498–506. 10.3732/ajb.0800054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colicchio J. M., Herman J. (2020). Empirical patterns of environmental variation favor adaptive transgenerational plasticity. Ecol. Evol. 10 1648–1665. 10.1002/ece3.6022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalrymple R. L., Kemp D. J., Flores-Moreno H., Laffan S. W., White T. E., Hemmings F. A., et al. (2020). Macroecological patterns in flower colour are shaped by both biotic and abiotic factors. New Phytol. 228 1972–1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Valle J. C., Alcalde-Eon C., Escribano-Bailón M. T., Buide M. L., Whittall J. B., Narbona E. (2019). Stability of petal color polymorphism: the significance of anthocyanin accumulation in photosynthetic tissues. BMC Plant Biol. 19:496. 10.1186/s12870-019-2082-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Valle J. C., Buide M. L., Whittall J. B., Narbona E. (2018). Phenotypic plasticity in light-induced flavonoids varies among tissues in Silene littorea (Caryophyllaceae). Environ. Exp. Bot. 153 100–107. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.05.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J., Fu Z., Chen S., Damaris R. N., Wang K., Li T., et al. (2015). Proteomic and epigenetic analyses of lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) petals between red and white cultivars. Plant Cell Physiol. 56 1546–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan D., Wang X., Tang X., Ye X., Ren S., Wang D., et al. (2018). Histone H3K9 demethylase JMJ25 epigenetically modulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in poplar. Plant J. 96 1121–1136. 10.1111/tpj.14092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenster C. B., Armbruster W. S., Wilson P., Dudash M. R., Thomson J. D. (2004). Pollination syndromes and floral specialization. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35 375–403. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gegear R. J., Burns J. G. (2007). The birds, the bees, and the virtual flowers: Can pollinator behavior drive ecological speciation in flowering plants? Am. Nat. 170 551–566. 10.1086/521230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez J. M., Perfectti F., Armas C., Narbona E., González-Megías A., Navarro L., et al. (2020). Within-individual phenotypic plasticity in flowers fosters pollination niche shift. Nat. Commun. 11:4019. 10.1038/s41467-020-17875-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould K. S., Lister C. (2006). “Flavonoid functions in plants,” in Flavonoids. Chemistry, Biochemistry, and Applications, eds Andersen Ø. M., Markham K. R. (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; ), 397–441. [Google Scholar]

- Han M. L., Yin J., Zhao Y. H., Sun X. W., Meng J. X., Zhou J., et al. (2020). How the color fades from Malus halliana flowers: Transcriptome sequencing and DNA methylation analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 11:576054. 10.3389/fpls.2020.576054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman J. J., Sultan S. E. (2016). DNA methylation mediates genetic variation for adaptive transgenerational plasticity. Proc. Biol. Sci. 283:20160988. 10.1098/rspb.2016.0988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera C. M., Bazaga P. (2013). Epigenetic correlates of plant phenotypic plasticity: DNA methylation differs between prickly and nonprickly leaves in heterophyllous Ilex aquifolium (Aquifoliaceae) trees. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 171 441–452. 10.1111/boj.12007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera C. M., Medrano M., Bazaga P. (2014). Variation in DNA methylation transmissibility, genetic heterogeneity and fecundity-related traits in natural populations of the perennial herb Helleborus foetidus. Mol. Ecol. 23 1085–1095. 10.1111/mec.12679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera C. M., Pozo M. I., Bazaga P. (2012). Jack of all nectars, master of most: DNA methylation and the epigenetic basis of niche width in a flower-living yeast. Mol. Ecol. 21 2602–2616. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05402.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hichri I., Barrieu F., Bogs J., Kappel C., Delrot S., Lauvergeat V. (2011). Recent advances in the transcriptional regulation of the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. J. Exp. Bot. 62 2465–2483. 10.1093/jxb/erq442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin R. E., Strauss S. Y. (2005). Flower color microevolution in wild radish: evolutionary response to pollinator-mediated selection. Am. Nat. 165 225–237. 10.1086/426714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonka E., Raz G. (2009). Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: prevalence, mechanisms, and implications for the study of heredity and evolution. Q. Rev. Biol. 84 131–176. 10.1086/598822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen D. J., Raguso R. A. (2018). Lingering effects of herbivory and plant defenses on pollinators. Curr. Biol. 28 R1164–R1169. 10.1016/j.cub.2018.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. T., Campbell S. A., Barrett S. C. (2015). Evolutionary interactions between plant reproduction and defense against herbivores. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 46 191–213. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler A., Chautá A. (2020). The ecological consequences of herbivore-induced plant responses on plant–pollinator interactions. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 4 33–43. 10.1042/ETLS20190121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koski M. H., Galloway L. F. (2020). Geographic variation in floral color and reflectance correlates with temperature and colonization history. Front. Plant Sci. 11:991. 10.3389/fpls.2020.00991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laitinen R. A. E., Nikoloski Z. (2019). Genetic basis of plasticity in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 70 795–804. 10.1093/jxb/ery404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehto W. R., Tinghitella R. M. (2020). Predator-induced maternal and paternal effects independently alter sexual selection. Evolution 74 404–418. 10.1111/evo.13906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev-Yadun S., Gould K. S. (2008). “Role of anthocyanins in plant defence,” in Anthocyanins, eds Winefield C., Davies K., Gould K. (New York, NY: Springer; ), 22–28. 10.1007/978-0-387-77335-3_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Losada M., Veiga T., Guitián J., Guitián J., Guitián P., Sobral M. (2015). Is there a hybridization barrier between Gentiana lutea color morphs? PeerJ 3:e1308. 10.7717/peerj.1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall A. C., Case S., Espy K., Adams G., Murphy S. J. (2018). Leaf herbivory induces resistance against florivores in Raphanus sativus. Botany 96 337–343. 10.1139/cjb-2017-0153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morita Y., Hoshino A. (2018). Recent advances in flower color variation and patterning of Japanese morning glory and petunia. Breed. Sci. 68 128–138. 10.1270/jsbbs.17107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narbona E., Wang H., Ortiz P. L., Arista M., Imbert E. (2018). Flower colour polymorphism in the Mediterranean Basin: occurrence, maintenance and implications for speciation. Plant Biol. 20 8–20. 10.1111/plb.12575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neylan I. P., Dirzo R., Sobral M. (2018). Cumulative effects of transgenerational induction on plant palatability to generalist and specialist herbivores. Web Ecol. 18 41–46. 10.5194/we-18-41-2018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2013). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Core Team. [Google Scholar]

- Rausher M. D. (2008). Evolutionary transitions in floral color. Int. J. Plant Sci. 169 7–21. 10.1086/523358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts W. R., Roalson E. H. (2017). Comparative transcriptome analyses of flower development in four species of Achimenes (Gesneriaceae). BMC Genomics 18:240. 10.1186/s12864-017-3623-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusman Q., Lucas-Barbosa D., Poelman E. H., Dicke M. (2019a). Ecology of plastic flowers. Trends Plant Sci. 24 725–740. 10.1016/j.tplants.2019.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusman Q., Poelman E. H., Nowrin F., Polder G., Lucas-Barbosa D. (2019b). Floral plasticity: herbivore-species-specific-induced changes in flower traits with contrasting effects on pollinator visitation. Plant Cell Environ. 42 1882–1896. 10.1111/pce.13520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiestl F. P., Johnson S. D. (2013). Pollinator-mediated evolution of floral signals. Trends Ecol. Evol. 28 307–315. 10.1016/j.tree.2013.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sletvold N., Trunschke J., Smit M., Verbeek J., Ågren J. (2016). Strong pollinator-mediated selection for increased flower brightness and contrast in a deceptive orchid. Evolution 70 716–724. 10.1111/evo.12881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel J. M., Chen G. F., Watt L. R., Schemske D. W. (2010). The biology of speciation. Evolution 64 295–315. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00877.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel J. M., Streisfeld M. A. (2013). Flower color as a model system for studies of plant evo-devo. Front. Plant Sci. 4:321. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobral M., Veiga T., Domínguez P., Guitián J. A., Guitián P., Guitián J. M. (2015). Selective pressures explain differences in flower color among Gentiana lutea populations. PLoS One 10:e0132522. 10.1371/journal.pone.0132522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaethe J., Tautz J., Chittka L. (2001). Visual constraints in foraging bumblebees: flower size and color affect search time and flight behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 3898–3903. 10.1073/pnas.071053098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton M. L. (1987). Reproductive biology of petal color variants in wild populations of Raphanus savitus: I. Pollinator response to color morphs. Am. J. Bot. 74 178–187. 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1987.tb08595.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss S. Y., Irwin R. E., Lambrix V. M. (2004). Optimal defence theory and flower petal colour predict variation in the secondary chemistry of wild radish. J. Ecol. 92 132–141. 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2004.00843.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss S. Y., Whittall J. B. (2006). Non-pollinator agents of selection on floral traits. Ecol. Evol. Flowers 208 120–138. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y., Sasaki N., Ohmiya A. (2008). Biosynthesis of plant pigments: anthocyanins, betalains and carotenoids. Plant J. 54 733–749. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03447.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Kooi C. J., Dyer A. G., Kevan P. G., Lunau K. (2019). Functional significance of the optical properties of flowers for visual signalling. Ann. Bot. 123 263–276. 10.1093/aob/mcy119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga T., Guitián J., Guitián P., Guitián J., Sobral M. (2015). Are pollinators and seed predators selective agents on flower color in Gentiana lutea? Evol. Ecol. 29 451–464. 10.1007/s10682-014-9751-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vekemans X., Beauwens T., Lemaire M., Roldán-Ruiz I. (2002). Data from amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers show indication of size homoplasy and of a relationship between degree of homoplasy and fragment size. Mol. Ecol. 11 139–151. 10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01415.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven K. J. F., Jansen J. J., van Dijk P. J., Biere A. (2010). Stress-induced DNA methylation changes and their heritability in asexual dandelions. New Phytol. 185 1108–1118. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03121.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven K. J. F., vonHoldt B. M., Sork V. L. (2016). Epigenetics in ecology and evolution: what we know and what we need to know. Mol. Ecol. 25 1631–1638. 10.1111/mec.13617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Ran L., Hou Y., Tian Q., Li C., Liu R., et al. (2017). The transcription factor MYB115 contributes to the regulation of proanthocyanidin biosynthesis and enhances fungal resistance in poplar. New Phytol. 215 351–367. 10.1111/nph.14569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren J., Mackenzie S. (2001). Why are all colour combinations not equally represented as flower-colour polymorphisms? New Phytol. 151 237–241. 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2001.00159.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wester P., Lunau K. (2017). Plant–pollinator communication. Adv. Bot. Res. 82 225–257. 10.1016/bs.abr.2016.10.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Zhao X., Qiu H. (2013). “Flavones and flavonols: Phytochemistry and biochemistry,” in Natural Products: Phytochemistry, Botany and Metabolism of Alkaloids, Phenolics and Terpenes, eds Ramawat K., Mérillon J. M. (Berlin: Springer; ), 1821–1847. 10.1007/978-3-642-22144-6_60 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.