Summary Paragraph:

Frequently referred to as the “magic methyl effect”, installation of methyl groups, especially α to heteroatoms, has been shown to drastically increase the potency of bioactive molecules1–3. Current methylation methods display limited scope and have not been demonstrated in complex settings1. Herein we report a regio- and chemoselective oxidative C(sp3)–H methylation method compatible with late-stage functionalization. A key to affecting this new chemistry was the combination of a highly site- and chemoselective C–H hydroxylation with a mild, functional group tolerant methylation. Using a small molecule manganese catalyst Mn(CF3PDP) at low loading (substrate/catalyst = 200) afforded targeted C–H hydroxylation on heterocyclic cores while preserving electron neutral and rich aryls. Fluorine or Lewis acid assisted formation of reactive iminium or oxonium intermediates enabled the use of a modestly nucleophilic organoaluminum methylating reagent that preserves other electrophilic functionalities on the substrate. The late-stage C(sp3)–H methylation is demonstrated on forty-one substrates housing sixteen different medicinally important cores incorporating electron-rich aryls, heterocycles, carbonyls, and amines. Eighteen pharmacologically relevant molecules with competing sites, including drugs (for example tedizolid) and natural products, are methylated site-selectively at the most electron rich, least sterically hindered position. Syntheses of two magic methyl substrates, an RORc inverse agonist and an S1P1 antagonist, are demonstrated for the first time via late-stage methylation from the drug or its advanced precursor. Additionally, an unprecedented remote methylation of the B-ring carbocycle of an abiraterone analog is shown. The ability to methylate such complex molecules at late stages will reduce synthetic effort and thereby expedite broader exploration of the magic methyl effect in pursuit of novel small molecule therapeutics and chemical probes.

The introduction of methyl groups has the potential to drastically improve the biological activities of a drug candidate by altering its binding affinity, solubility, and metabolism1–8. Such changes have been demonstrated to increase the potency of lead compounds up to more than 2000 folds and to enable interrogation of biological processes (Fig. 1a)6–8. Although methyl groups are ubiquitous in small-molecule drugs1, no general method is available to incorporate them in complex molecules at late stages. Accordingly, de novo synthesis, a rate-limiting step in drug discovery that impairs its overall atom-economy, is required9,10. A practical synthetic method that allows selective installation of methyl groups from C–H bonds at sites adjacent to heteroatoms, where the magic methyl effect is often most significant, would streamline diversification of drug leads and encourage more comprehensive investigations of this effect. Over the past decade, considerable progress has been made in developing C(sp3)–H alkylation methods where the N-or O-heterocycle acts as a nucleophilic coupling partner11–17. Such cross-couplings have shown broad scope with respect to alkyl electrophiles but limited scope of the metalated heterocyclic intermediates generated via substrate-controlled deprotonation or single-electron transfer (SET). Cases demonstrated with methyl electrophiles have focused on simple azacycles 11,13,15–17. Expanding the heterocyclic scope to include dissymmetric substrates, epimerizable stereocenters, electrophilic functionalities (e.g., carbonyl, nitrile), remote basic amines, heteroaromatics, and halogenated aromatics remains a major challenge to be overcome for widespread use in late-stage diversification. Additionally, while direct C–C bond forming reactions may be desirable for installing larger and/or functionalized alkyl groups, direct methylation often results in inseparable mixtures with the starting material due to the methyl group’s small size and electron neutrality.

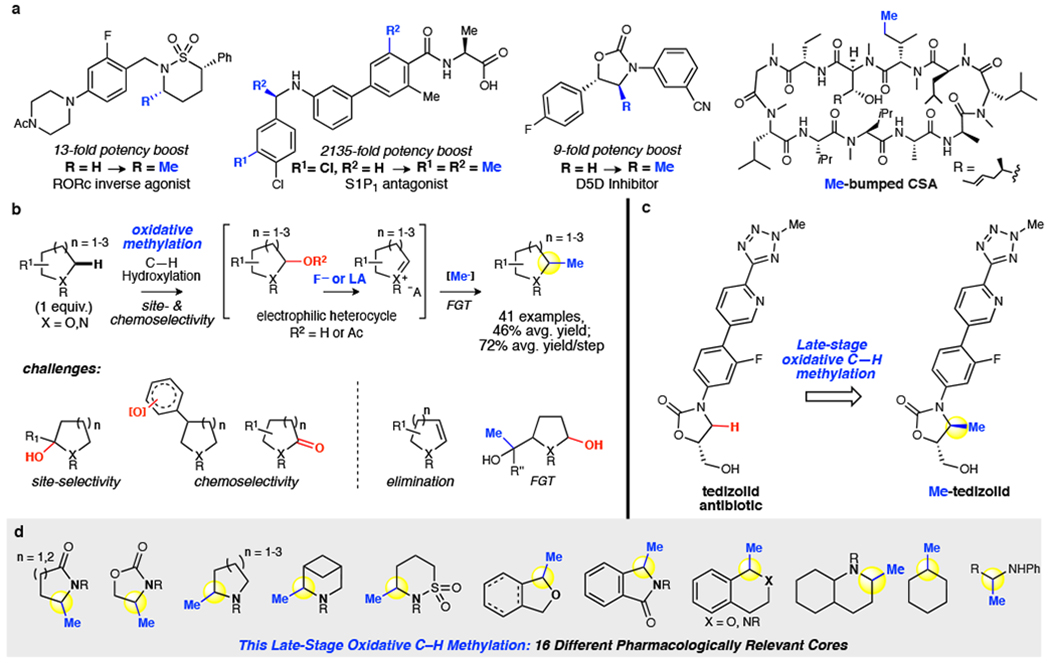

Fig. 1 |. C(sp3)–H methylation.

a, The magic methyl effect boosts potency of drugs and furnishes biological probes. b, This oxidative methylation proceeds through an electrophilic intermediate. Challenges included over-oxidation, unselective oxidation, elimination and unselective methylation pathways. c, Late stage oxidative methylation of antibiotic tedizolid. d, Oxidative C-H methylation is demonstrated on 16 different pharmaceutically relevant cores. Using only 1 equivalent of substrate, methylation proceeds site-selectively and with functional group tolerance to afford preparative yields in 41 examples (including 18 complex bioactive molecules).

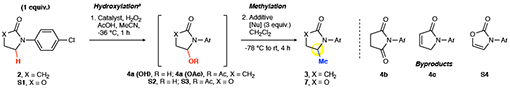

We sought to approach C(sp3)–H methylation in N- and O-containing heterocycles in an oxidative fashion through a hydroxylated intermediate, with subsequent iminium or oxonium ion formation and methylation (Fig. 1b). Catalyst control could be leveraged to influence the site- and chemoselectivity of C–H hydroxylation in a broad range of heterocycles (Fig. 1c,d). Reports of alkylations of N-acyliminium ions are of limited scope18–20. Although C(sp3–H oxidation α to heteroatoms has been well-demonstrated, substrate-controlled selectivities can afford poor site- and chemoselectivity thereby limiting examples in complex settings. Additionally, the strong hyperconjugative activation of hemiaminals and hemiacetals typically promotes overoxidation to the corresponding carbonyl, calling for reduction prior to or after methylation (Fig. 1b)21–26.

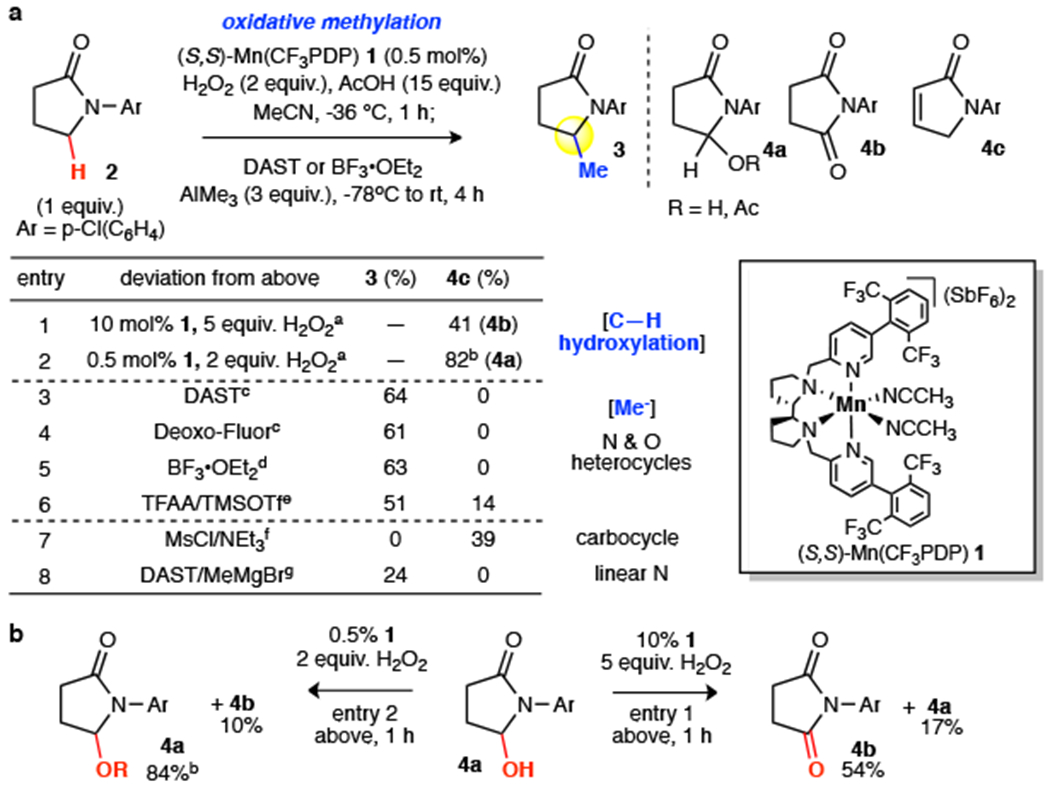

The Mn(CF3PDP)(MeCN)2(SbF6)2 1 catalyst was reported to uniquely control site- and chemoselectivity in hydroxylating strong methylene C(sp3)–H bonds while tolerating halogenated arenes, although the tolerance for electron neutral or rich aromatic and some heteroaromatic rings remained a challenge (Fig. 1b)27. We questioned if sterically hindered catalyst 1 could result in faster C–H hydroxylation than alcohol oxidation for hyperconjugatively activated C–H bonds, and whether under milder oxidation conditions such a rate difference would increase chemoselectivity and yield for the hydroxylated product. Under the previously reported forcing conditions (10 mol% 1, 5 equiv. H2O2)27, oxidation of arylated γ-lactam 2 afforded a significant amount of over-oxidation to the corresponding imide (Fig. 2a, 4b, 41%). Lowering the catalyst and hydrogen peroxide loadings (0.5 mol% 1, 2.0 equiv. H2O2) enabled the C–H bond α to nitrogen (α-N) to be hydroxylated to hemiaminal intermediates (hemiaminal, and hemiaminal acetate from AcOH) in an excellent 82% yield (4a). Consistent with slower alcohol oxidation, exposure of alcohol 4a to identical oxidation conditions afforded 84% hemiaminals with only 10% imide 4b (Fig. 2b). In contrast, exposure of alcohol 4a to the forcing conditions afforded predominantly imide 4b (54%) with only 17% hemiaminals. Under mild oxidation conditions, we additionally observed enhanced chemoselectivities for electron-rich and neutral aromatics and heteroaromatics, likely due to attenuation of similarly higher-energy overoxidation pathways (vide infra). Notably, this constitutes among the highest S/C ratio (substrate/catalyst = 200) reported to date for a preparative C(sp3)–H hydroxylation reaction in a complex setting. The ability to separate the hydroxylated intermediate prior to methylation, while not necessary for alkylation, avoids formation of an inseparable mixture of the methylated product and starting material often observed in direct methylation17. Expectedly, Fe(PDP) and Fe(CF3PDP), previously employed for oxidative α-arylation of aliphatic peptides28–30 gave a complex mixture of aromatic oxidation products (Extended Data). Mn(PDP), shown to hydroxylate simple linear amides31, was not reactive enough to promote preparative hydroxylation of 2, but can be uniquely effective for some sterically hindered substrates (vide infra).

Fig. 2 |. Reaction development.

a, Optimization of the oxidative methylation reaction. For achiral substrates, (R,R)- and (S,S)-1 can be used interchangeably. b, Exposure of hemiaminal to mild C–H hydroxylation developed here (0.5 mol% 1, 2 equiv. H2O2) gives little overoxidation to the imide. The previous forcing condition (10 mol% 1, 5 equiv. H2O2) results in imide as the major product. aNo methylation. bMixture of hemiaminal (64%-71%) and hemiaminal acetate from AcOH (13%-18%). c1 equiv. d2 equiv. eTFAA (1 equiv.), TMSOTf (1 equiv.). fMsCl (1 equiv.), NEt3 (1 equiv.), NaHCO3 wash; AlMe3 (3 equiv.), −78 °C, 2 h; rt 1 h. gMeMgBr (3 equiv.), −78°C, 3 h.

A further challenge with an oxidative methylation approach was to identify a way to activate the hemiaminal/hemiacetal towards attack by a nucleophilic methyl source without resulting in either undesirable elimination to the enamine, or attack at other electrophilic moieties in complex substrates (Fig. 1b). The modestly nucleophilic and Lewis acidic nature of organoaluminum reagents suggested they could achieve such selective reactivity. Their high affinity for fluorine coupled to their tolerance of Lewis acids afforded a means of generating reactive iminium or oxonium species from transient C–F or from C–OH bond ionization32,33. High functional group tolerance was also expected given organoaluminum reagents’ ability to methylate oxoniums at late stages in the presence of other electrophilic functionalities34.

After significant experimentation abbreviated in Fig. 2a, we arrived at a scalable general procedure employing either diethylaminosulfur trifluoride (DAST) or boron trifluoride diethyl etherate (BF3•OEt2) as hydroxyl activators for iminium formation with AlMe3 as an inexpensive, commercial methylating reagent. Thermally stable bis(2-methoxyethyl)aminosulfur trifluoromethanesulfonate (Deoxo-Fluor) may also be used. In general, the fluorine-assisted methylation strategy should be used in substrates containing Lewis basic or electrophilic functional groups, while ones lacking such functionality can be methylated via the BF3 activation strategy (Extended Data). When unreacted hemiaminal acetate is observed, esterification of the hemiaminal by trifluoroacetic anhydride (TFAA) and subsequent activation of both esters with trimethylsilyl triflate (TMSOTf) to furnish the iminium can be employed34. The capacity to vary the ionization method with AlMe3 is critical to the broad scope of this methylation, providing a facile handle to tune reactivity and/or selectivity for a given substrate in cases where unreacted hemiaminal intermediates or enamine byproducts are observed (vide infra).

Alternative activation modes with AlMe3 and methylating reagents with DAST were examined (Extended Data). In hemiaminals, base-mediated formation of an activated C–O bond (i.e., mesylation) gave predominantly elimination (Fig. 2a). Grignard reagents, even at cryogenic temperatures, afford diminished yields relative to AlMe3, likely due to poor functional group tolerance. Although ineffective for methylation of heterocyclic substrates, these reagents can be used to effect methylation in challenging linear secondary amine and carbocyclic substrates (vide infra, 51, 53).

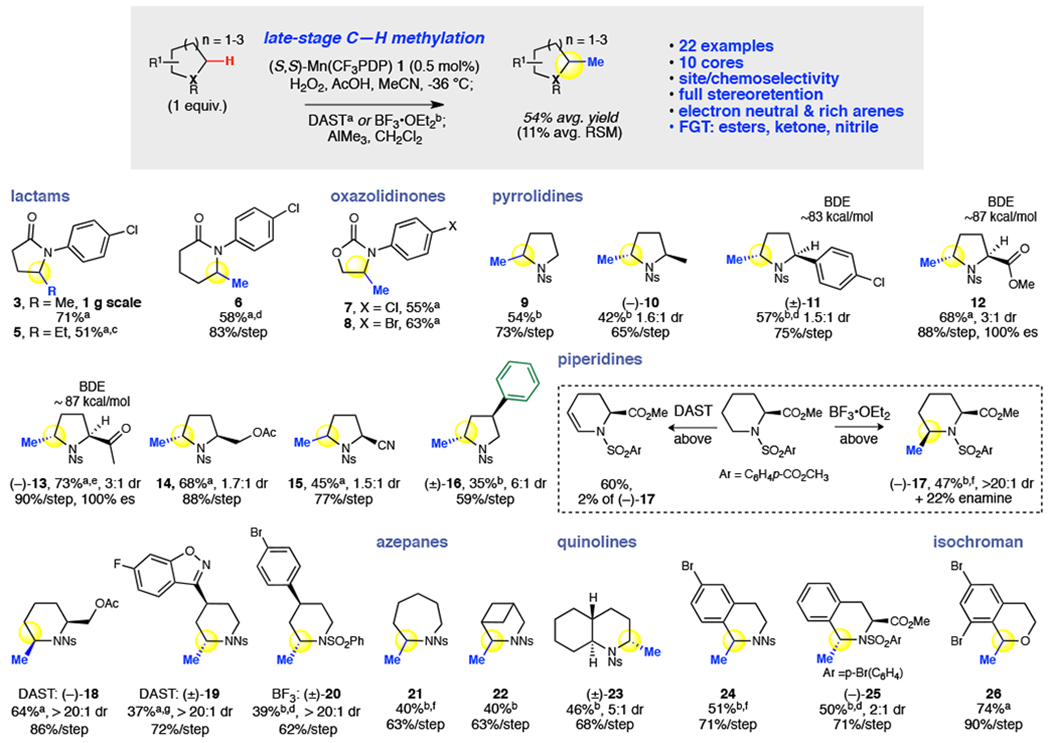

We explored oxidative methylation for its capacity to methylate a collection of twenty-two compounds comprising ten different heterocyclic cores commonly found in pharmaceuticals (Fig. 3). A gram-scale methylation of 2 was successfully done in 71% yield via DAST activation; an ethyl group could also be installed using commercial triethylaluminum (5, 51%). Methylated δ-lactam 6 was isolated in 58% yield; analogous to the γ-lactam, under more forcing oxidation conditions δ-lactam gave predominantly imide (60%). For amide 2, methylated 3 was observed in preparative yields with both DAST and BF3 ionization (Fig. 2a). However, in oxazolidinones, housing more labile carbonyls, fluorination with DAST furnished significantly higher yields (7, 55% versus 10% with BF3, Extended Data; 8, 63%). Pyrrolidine, the fifth most common nitrogen heterocycle in drugs35,36, undergoes hydroxylation with no significant over-oxidation to pyrrolidinone, followed by BF3-promoted methylation to afford mono-methylated product 9 in 54% yield. Critical for late-stage derivatization and orthogonal to most radical processes, high site-selectivity for methylation at the less sterically hindered methylene site was observed in substrates bearing more activated tertiary (3°) aliphatic, 3° benzylic, and 3° α-carbonyl C–H bonds to afford products in preparative yields (10-13). Full stereoretention was measured with chiral substrates leading to 12 and 13, indicating that the high regioselectivity is attributed to catalyst control of Mn(CF3PDP) 1 in the C–H cleavage step. Methyl ester, ketone, acetate, and nitrile, not well tolerated with strongly nucleophilic methylation reagents, were maintained using DAST activation/AlMe3 methylation (12-15). Methylation on a 3-phenylpyrrolidine derivative proceeded regioselectively at the methylene site distal from the phenyl group, furnishing the 5-methylated product 16 in useful yield. Such chemoselectivity for electron neutral aromatics has not been previously demonstrated: at higher catalyst loadings, 1 afforded poor yields and chemoselectivities27.

Fig. 3 |. Ten different heterocyclic cores, commonly found in pharmaceuticals, were explored in the Mn(CF3PDP) 1-catalyzed C–H hydroxylation and methylation.

Twenty-two heterocycles including lactams, oxazolidinones, pyrrolidines, piperidines, azepane, azabicycloheptane, quinolines, and isochroman were oxidatively methylated in preparative overall yields (54% average) using limiting substrate. General oxidation: substrate, catalyst (0.5 mol%), AcOH in MeCN, −36 °C; H2O2 (2 or 5 equiv.) in MeCN syringe pump 1 h. Mixture passed through silica plug, EtOAc flush, concentrated prior to isolation or methylation. For insoluble substrates, CH2Cl2 added to MeCN and/or 0 °C. aDAST Activation: crude in CH2Cl2 (0.2 M), DAST (1 equiv.) added at −78 °C; room temperature (rt) for 1 h; cooled to −78 °C, AlMe3 added, stirred 2 h; rt for 1 h. bBF3 Activation: crude in CH2Cl2 (0.2 M), −78 °C, AlMe3 (3 equiv.) and BF3•OEt2 (2 equiv.) sequentially added, stirred 1 h; rt for 3 h. cTriethylaluminum. d2 mol% (S,S)-1. eAlMe3 −78 °C, 3 h. f1 mol% (S,S)-1. gFor facile purification, hemiaminal isolated before methylation. 10 mol% (S,S)-1, rt, starting material recycled 1x.

In piperidines, the most common nitrogen heterocycle in small molecule drugs35,36, both DAST and BF3 activation should be tried: enamine formation competes strongly with methylation and is highly dependent on both the substrate and the mode of hemiaminal activation (Fig. 3). For example, a pipecolic acid derivative gave 2% of the methylated product with 60% enamine byproduct under DAST activation, whereas the BF3 activation furnished 17 in 47% overall yield. Alternatively, methylation of piperidinyl-2-methyl acetate using BF3 did not fully convert the hemiaminal to methylated product, whereas DAST activation afforded 18 in 64% yield. Gamma-substituted piperidines are prevalent structures in drugs, such as in paliperidone and paroxetine. An N-nosyl intermediate in the synthesis of paliperidone was selectively methylated using the DAST protocol to give 19 in 37% yield with no protection of the benzisoxazole ring γ to nitrogen. However, methylation of γ-(4-bromophenyl)piperidine with DAST resulted predominantly in enamine formation, while the BF3 activation strategy affording 39% yield of methylated 20. Notably, all piperidines furnished a single observed methylated diastereomer, likely as a result of the rigid half-chair conformation of the iminium intermediate37.

Other simple cyclic amines, such as azepane, azabicycloheptane, and decahydroquinoline, were selectively methylated using the BF3 activation protocol α-N to afford 40%-46% overall yields of mono-methylated products 21-23. Tetrahydroisoquinoline, among the top 20 nitrogen heterocycles in FDA-approved drugs36, was oxidatively methylated using BF3 activation in good yields for both a brominated and an unsubstituted aromatic structure (24, 51%; 25, 50%), with lower yields observed using DAST activation. In contrast to the majority of radical based oxidation methods that oxidize isochromans to isochromanones, under Mn(CF3PDP) 1 catalysis little over-oxidation is observed. 6,8-Dibromoisochroman was oxidatively methylated using DAST/AlMe3 in 74% yield (26); BF3 activation for these types of oxygen heterocycles afforded ring-opening products38.

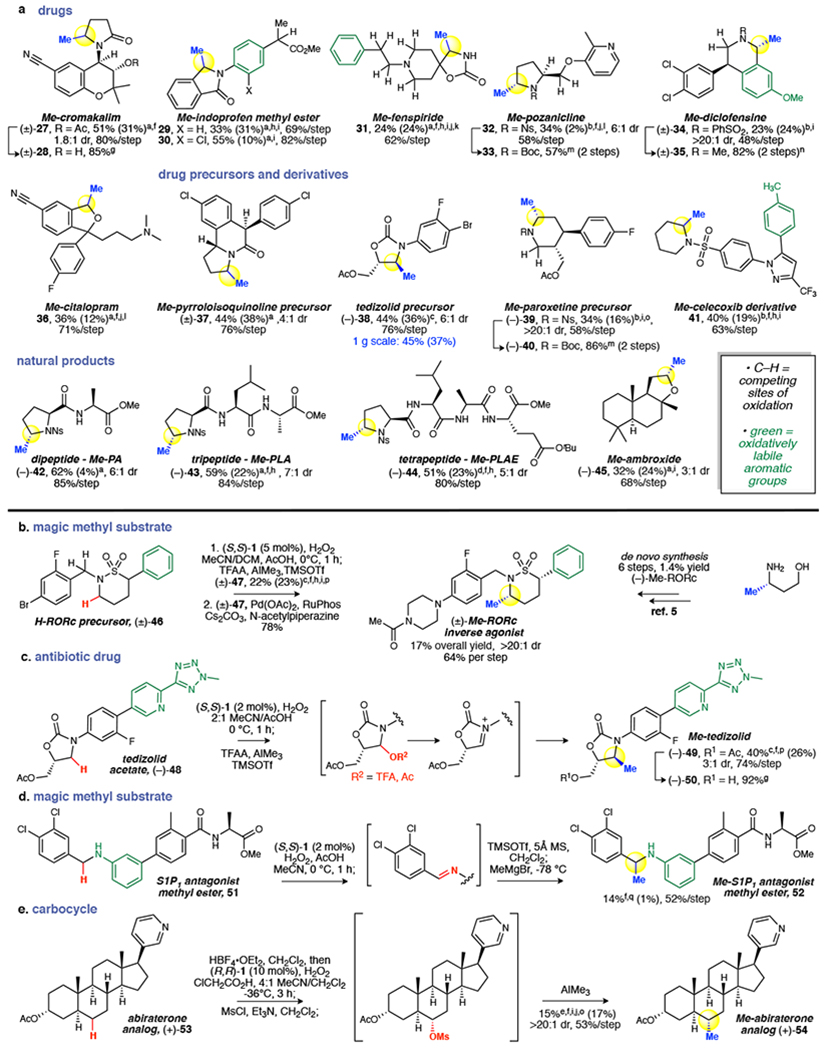

We explored the ability of highly site- and chemoselective Mn(CF3PDP) 1 catalyzed C–H hydroxylation, coupled to a Lewis-acid/fluorine-promoted methylation, to provide a general method for installing methyl groups directly into the hydrocarbon cores of complex, bioactive molecules, thereby avoiding lengthy and costly de novo synthesis (Fig. 4)1,9,10. Cromakalim acetate, a potassium channel activator housing a γ-lactam with tertiary and secondary hyperconjugatively activated α-N C(sp3)–H bonds, underwent oxidative methylation at the less activated but more sterically accessible secondary site in good yield (27, 51%). The acetate could be readily removed to furnish methylated cromakalim 28 in 85% yield. The methyl ester of indoprofen, an anti-inflammatory drug investigated for spinal muscular atrophy39, was oxidatively methylated at its central isoindolinone core in synthetically useful yields (29, 33%). The enhanced chemoselectivity of oxidative methylation with 1 under reduced loadings is evident when comparing with results at higher loadings (10 mol%), where 29 was obtained in diminished yields (7%) due to poor chemoselectivity. Chloroindoprofen methyl ester, a derivative with decreased electron density on the aromatic ring, undergoes oxidative methylation in higher yields (30, 55%). Fenspiride, an antitussive drug, was oxidatively methylated in a useful overall yield (31, 24%) at a methylene site adjacent to the quaternary center of an unprotected spiro-oxazolidinone, using (S,S)-Mn(PDP)(SbF6)2 catalyst that is less sensitive to sterics27. The basic piperidine nitrogen of fenspiride was protected with HBF4 and rendered a strong electron-withdrawing group, deactivating a distal benzylic site and three α-N sites towards C–H oxidation40. Notably, SET reactions proceeding via basic amine catalysis (e.g. quinuclidine) are not amenable to this kind of nitrogen protection strategy and therefore do not undergo remote C–H functionalizations17,24. A derivative of pozanicline, a neuroprotective drug evaluated for ADHD treatment41, undergoes α-N oxidative methylation at the pyrrolidine in useful yield and diastereoselectivity (32, 34%, 6:1 dr). The HBF4 protection deactivates the basic pyridine moiety and its proximal ethereal sites from oxidation with 1. While DAST activation produced similar yields, a higher diastereoselectivity was obtained with BF3 activation (6:1 vs. 3:1), possibly due to different iminium counterions (Fig. 1b). The nosyl group on pyrrolidine, a convenient chromophoric protecting group for secondary amines, was readily removed using thiophenol and subsequently protected with tert-butyloxycarbonyl (Boc) to afford 33 in 57% overall yield. Underscoring the unique chemoselectivity of this method, a derivative of the antidepressant diclofensine was oxidatively methylated at its tetrahydroisoquinoline core to afford 34 in useful yield despite the presence of a very electron rich methoxyphenyl. Mild, reductive desulfonation followed by reductive amination furnished Me-diclofensine 35 in 82% yield. The antidepressant drug citalopram, upon HBF4 protection of the tertiary amine, is oxidatively methylated at its dihydroisobenzofuran core to afford 36. DAST activation was used on the majority of these densely functionalized substrates whereas BF3 activation was more effective on the tetrahydroisoquinoline core.

Fig. 4 |. Application of oxidative methylation for late stage functionalization.

a, Selective methylation of drugs, drug precursors, intermediates and natural products underscores the power of this method for late stage applications. Generally, 0.5 to 5 mol% (S,S)-1 and 2 or 5 equiv. H2O2 were used for oxidation. Higher catalyst and oxidant loadings were applied when conversions were low. b, Methylation of an RORc inverse agonist precursor rapidly furnishes the analogue with 13-fold potency boost. c, Methylation of antibiotic tedizolid acetate furnishes Me-tedizolid. d, Methylation of linear aniline in S1P1 antagonist methyl ester occurs at a position where magic methyl effect was observed to contribute to a 2135-fold potency boost. e, Remote methylation of a carbocycle on an abiraterone analog. aDAST activation. bBF3 activation. cTMSOTf activation: TFAA, rt, 1 h; cooled to −78 °C, AlMe3 and TMSOTf sequentially added, 2 h; then rt, 1 h. dDeoxo-Fluor activation. eMesylation activation: MsCl and Et3N added, rt, 1 h; NaHCO3 wash, dried, condensed; redissolved in CH2Cl2, AlMe3 added at −78 °C, stirred 2 h; then rt, 1 h. fOxidation intermediates isolated before methylation. g1 M NaOH/MeOH. hStarting material recycled 1x. iFor insoluble substrates, CH2Cl2 added to MeCN and/or 0 °C. jHBF4 protection, ref. 40. k10 mol% (S,S)-Mn(PDP)(SbF6)2. l10 mol% (S,S)-1. mPhSH, Cs2CO3; Boc2O. nMg, NH4Cl; formaldehyde, formic acid. o10 mol% (RR)-1. p2 equiv. TMSOTf. qTMSOTf (1.2 equiv.), 0 °C, 1 h, then MeMgBr (3.0 equiv.) −78 °C, 4 h, repeated once.

A precursor to pyrroloisoquinoline, a prevalent structure in compounds with neurotransmitter uptake inhibitor properties42, undergoes selective oxidative methylation at the less sterically hindered methylene site, versus the more activated tertiary, benzylic site, to furnish 37 (44% yield, Fig. 4a). Oxidation of a carbamate precursor to antibiotic tedizolid furnished substantial amounts of hemiaminal acetate that could be methylated in a useful overall yield under the TFAA/TMSOTf-assisted methylation (38, 44%). This method is operationally facile and can be performed on gram scale with no loss in efficiency (45% yield). Fluorination afforded lower yields of methylated product 38 due to unconverted hemiaminal acetate. The core piperidine of a paroxetine precursor and metabolite43 was oxidatively methylated in useful overall yields (39, 34%) preferentially at the less sterically hindered methylene site remote from the 3-acetoxymethyl group. Nosyl deprotection and subsequent Boc protection afforded 40 in 86% yield. A piperidine derivative of the anti-inflammatory drug celecoxib was mono-methylated to afford 41 in good overall yield in the presence of an oxidatively labile tolyl group and pyrazole, both tolerated during C–H oxidation with 1 and requiring no protection. In these piperidine substrates, BF3 activation was effective in furnishing methylated products.

Methylation of proline-based di-, tri-, and tetrapeptides proceeded with good overall yields and mass balances (42, 43, 44) with 1 under fluorine-assisted oxidative methylation conditions (Fig. 4a). Deoxo-Fluor may be used in substrates like tetrapeptide 44, where isolation from the polar byproducts of DAST is challenging. Although effective in promoting arylation of peptides with electron rich aromatic nucleophiles, BF3 activation in the AlMe3 methylation of peptides afforded complex mixtures, likely arising from activation of the amide carbonyls30. Ambroxide, a naturally occurring terpenoid, also undergoes selective oxidative methylation using DAST at a methylene site α to oxygen on its tetrahydrofuran ring to afford 45 in 32% yield (with 19% of sclareolide lactone). The use of BF3 in this case promoted ring-opening. Significantly, Fe(PDP), ruthenium-mediated oxidation, and 1 under forcing conditions all afforded sclareolide lactone as the major product isolated (see SI)10,21,28.

The sultam ring in an advanced intermediate of an RORc inverse agonist 46 (Fig. 4b) was oxidatively methylated with 1 using TFAA/TMSOTf activation/AlMe3 to afford 47 as the syn-diastereomer. Other activation modes, such as BF3, resulted in deleterious elimination pathways. Notably, an oxidatively labile phenyl moiety and a doubly activated benzylic methylene site were tolerated. Previous installation of the syn-methyl group afforded a 13-fold increase in RORc SRC1 selectivity relative to the unmethylated version; however, it required a six-step de novo synthesis proceeding in 1.4% overall yield5. This analog and others are now accessible via cross-coupling with methylated intermediate 47.

Tedizolid, a commercial oxazolidinone antibiotic for acute bacterial skin infections, bears numerous oxidatively sensitive functional groups such as a pyridine, tetrazole, and an N-methyl (Fig. 4c). Mn(CF3PDP) 1 oxidation (2 mol%) of tedizolid acetate 48 proceeded in ca. 53% yield of oxidized products (3:1 hemiaminal/acetate) with no protection of the dense nitrogen functionalities. The significant challenge was to identify a procedure to install the methyl group from the hemiaminal intermediates. Activation via fluorination furnished primarily eliminated products not observed on the simpler core structure (38, Fig. 4a), while BF3 activation resulted in side reactions. However, under TFAA/TMSOTf activation, elimination was suppressed and the methylated product 49 was obtained in a remarkable 40% overall yield, 74% per step, comparable to that of the simpler precursor 38. Deprotection of the acetate in 92% yield afforded Me-tedizolid 50, an interesting candidate for future biological evaluation given that a 9-fold boost in potency has been reported for similar oxazolidinone cores with methylation at the same position (Fig. 1a)44.

We questioned if the scope of this reaction could be extended beyond heterocycles, and found that oxidative C–H methylation is not restricted to substrates that can form iminium or oxonium intermediates: promising reactivity has been observed for both imines and remote alcohols generated via C–H hydroxylation with 1. An S1P1 antagonist, whose benzylic and aromatic methylations afforded a 2135-fold potency increase6, was methylated in its methyl ester form (51, Fig. 4d). While oxidation of the antagonist was successful without need for protection of the aniline motif, the resulting imine was much less reactive than an iminium and required a stronger nucleophile than AlMe3. In this case, we found that methylmagnesium bromide at cryogenic temperatures, with TMSOTf activation of the imine, produced the methylated product without eroding the amide and ester functional groups (52, 14%, 52% per step).

At higher catalyst loadings, Mn(CF3PDP) 1 is an effective catalyst for methylene C–H bond hydroxylations27. Abiraterone analog 53 was hydroxylated in ca. 32% yield (with 16% ketone) in one step, without recycling the starting material as required in Fe(CF3PDP) catalysis (Fig. 4e)40. In carbocyclic substrates, displacement of a C–F bond or ionization with a Lewis acid is difficult; however, mesylates of such aliphatic alcohols are stable and can be activated by AlMe3 to undergo substitution45. By replacing fluorination with mesylation, 53 was successfully methylated as a single observed diastereomer (54, 15% overall yield, 53% per step), likely through a carbocation intermediate. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first method that enables such remote methylation at unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds. The discovery of this reactivity underscores the importance of developing methylene oxidations that afford predominately alcohol products.

Extended Data

Extended Data Table 1 |.

Reaction Optimization.

| |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Substr. | Catalyst | Loading (mol%) | Additive | [Nu] | 4a (OH)/S2 (%) | 4a (OAc)/S3 (%) | 3/7 (%) | 4b (%) | 4c/S4 (%) | rsm (%) |

| Oxidation | |||||||||||

| 1b | 2 | Fe(PDP) | 3 x 5 | - | - | <5k | 0 | - | <5k | - | 0 |

| 2c | 2 | Fe(CF3PDP) | 3 x 5 | - | - | 8k | 0 | - | 6k | - | 0 |

| 3d | 2 | Mn(PDP)(OTf)2 | 1 | - | - | 12 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 75 |

| 4 | 2 | Mn(PDP)(SbF6)2 | 1 | - | - | 28 | 7 | - | <5k | - | 35 |

| 5e | 2 | Mn(CF3PDP) 1 | 10 | - | - | 13k | 10 | - | 41 | - | 0 |

| 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 51 | 21 | - | 9 | - | 0 |

| 7 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | - | - | 64 | 18 | - | <5k | - | 4 |

| Methylation | |||||||||||

| 8f | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | BF3•OEt2 | AlMe3 | <5k | 0 | 63 | <5k | 0 | 11 |

| 9f | S1 | 1 | 0.5 | BF3•OEt2 | AlMe3 | 11 | 5 | 10 | - | 4 | 27 |

| 10g | S1 | 1 | 0.5 | DAST | AlMe3 | 0 | 14k | 55 | - | 0 | 16 |

| 11g | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | DAST | AlMe3 | 0 | 0 | 64 | <5k | 0 | 12 |

| 12g | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | Deoxo-Fluor | AlMe3 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 6 | 0 | 5 |

| 13h | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | TFAA/TMSOTf | AlMe3 | 0 | 0 | 51 | <5k | 14 | 9 |

| 14h | S1 | 1 | 0.5 | TFAA/TMSOTf | AlMe3 | 0 | 0 | 46 | - | 20 | 13 |

| 15i | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | MsCl/Et3N | AlMe3 | 15 | 0 | 0 | <5k | 39 | 6 |

| 16g | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | DAST | ZnMe2 | 17 | 9 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 14 |

| 17g,j | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | DAST | MeMgBr | 24 | <5k | 24 | <5k | 0 | 9 |

General oxidation (unless otherwise noted): 2 (0.3 mmol), catalyst (x mol%, (R,R) and (S,S) used interchangeably), AcOH (15 equiv.), MeCN (0.5 M), −36 °C; H2O2 (2 equiv.) in MeCN (3.75 mL) syringe pump 1 h. Mixture passed through silica plug, EtOAc flush, concentrated prior to isolation or methylation. Isolated product yields.

Procedure ref. 28.

Procedure ref. 29.

Procedure ref. 31.

5 equiv. H2O2.

General BF3 alkylation: crude in CH2Cl2 (0.2 M), −78 °C, AlMe3 (3 equiv.) and BF3•OEt2 (2 equiv.) sequentially added, stirred 1 h; room temperature (rt) for 3 h.

General fluorine alkylation: crude in CH2Cl2 (0.2 M), fluorine additive (1 equiv.) added at −78 °C; rt for 1 h; cooled to −78 °C, nucleophile (3 equiv.) added, stirred 2 h; rt for 1 h.

General TMSOTf alkylation: crude in CH2Cl2 (0.2 M), TFAA (1 equiv.) added, stirred 1 h; cooled to −78 °C, AlMe3(3 equiv.) and TMSOTf (1 equiv.) sequentially added, stirred 2 h; rt for 1 h.

Crude in CH2Cl2 (0.2 M), MsCl (1 equiv.) and Et3N (1 equiv.) added, stirred 1 h; washed NaHCO3, dried, reduced; redissolved in CH2Cl2, AlMe3 (3 equiv.) added at −78 °C, stirred 2 h; rt for 1 h.

MeMgBr (3 equiv.) added at −78°C, stirred 3 h.

Yield by crude 1H NMR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by the NIGMS Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award MIRA (R35 GM122525) and support from Pfizer to study the modifications of natural products and medicinal compounds. We thank Dr. L. Zhu and the SCS NMR Lab for assistance with nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and B. Budaitis for checking the procedure in Figure 3, 8. The Bruker 500-Mz NMR spectrometer was obtained with the financial support of the Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust, Muscatine, Iowa, USA. The data reported in this paper are tabulated in the Supplementary Information.

Footnotes

Data availability The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Information and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests The University of Illinois has filed a patent application on the Mn(CF3-PDP) catalyst.

Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Schönherr H & Cernak T Profound methyl effects in drug discovery and a call for new C–H methylation reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 52, 12256–12267 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cernak T, Dykstra KD, Tyagarajan S, Vachal P & Krska SW The medicinal chemist’s toolbox for late stage functionalization of drug-like molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev 45, 546–576 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barreiro EJ, Kümmerle AE & Fraga CAM The methylation effect in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Rev, 111, 5215–5246 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung CS, Leung SSF, Tirado-Rives J & Jorgensen WL Methyl effects on protein-ligand binding. J. Med. Chem 55, 4489–4500 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fauber BP et al. Discovery of 1-{4-[3-Fluoro-4-((3S,6R)-3-methyl-1,1-dioxo-6-phenyl-[1,2]thiazinan-2-ylmethyl)-phenyl]-piperazin-1-yl}-ethanone (GNE-3500): a potent, selective, and orally bioavailable retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor c (RORc or RORγ) inverse agonist. J. Med. Chem 58, 5308–5322 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quancard J et al. A potent and selective S1P1 antagonist with efficacy in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Chem. Biol 19, 1142–1151 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belshaw PJ, Schoepfer JG, Liu K-Q, Morrison KL & Schreiber SL Rational design of orthogonal receptor-ligand combinations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 34, 2129–2132 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shogren-Knaak MA, Alaimo PJ & Shokat KM Recent advances in chemical approaches to the study of biological systems. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 17, 405–433 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blakemore DC et al. Organic synthesis provides opportunities to transform drug discovery. Nat. Chem 10, 383–394 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White MC & Zhao J Aliphatic C–H oxidations for late-stage functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 13988–14009 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campos KR Direct sp3 C–H bond activation adjacent to nitrogen in heterocycles. Chem. Soc. Rev 36, 1069–1084 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cordier CJ, Lundgren RJ & Fu GC Enantioconvergent cross-couplings of racemic alkylmetal reagents with unactivated secondary alkyl electrophiles: catalytic asymmetric Negishi α-alkylations of N-Boc-pyrrolidine. J. Am. Chem. Soc 135, 10946–10949 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beak P, Basu A, Gallagher DJ, Park YS & Thayumanavan S Regioselective, diastereoselective, and enantioselective lithiation-substitution sequences: reaction pathways and synthetic applications. Acc. Chem. Res 29, 552–560. (1996) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milligan JA, Phelan JP, Badir SO & Molander GA Alkyl carbon-carbon bond formation by nickel/photoredox cross-coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 58, 6152–6163 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paul A & Seidel D α-Functionalization of cyclic secondary amines: Lewis acid promoted addition of organometallics to transient imines. J. Am. Chem. Soc 141, 8778–8782 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain P, Verma P, Xia G & Yu J-Q Enantioselective amine α-functionalization via palladium-catalysed C–H arylation of thioamides. Nat. Chem 9, 140–144 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le C, Liang Y, Evans RW, Li X & MacMillan DWC Selective sp3 C–H alkylation via polarity-match-based cross-coupling. Nature 547, 79–83 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiemstra H & Speckamp WN “Additions to N-acyliminium ions” in Comprehensive Organic Synthesis: Selectivity, Strategy & Efficiency in Modern Organic Chemistry, Trost BM. & Fleming I. (Pergamon Press, 2007), vol. 2, “Additions to C–X π bonds part 2”, chap. 4.5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrus MB & Lashley JC Copper catalyzed allylic oxidation with peresters. Tetrahedron, 58, 845–866 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Z, Bohle DS & Li C-J Cu-catalyzed cross-dehydrogenative coupling : a versatile strategy for C–C bond formations via the oxidative activation of sp3 C–H bonds. PNAS, 103, 8928–8933 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato N, Hamaguchi Y, Umezawa N & Higuchi T Efficient oxidation of ethers with pyridine N-oxide catalyzed by ruthenium porphyrins. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 19, 411–416 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito R, Umezawa N & Higuchi T Unique oxidation reaction of amides with pyridine-N-oxide catalyzed by ruthenium porphyrin: direct oxidative conversion of N-acyl-L-proline to N-acyl-L-glutamate. J. Am. Chem. Soc 127, 834–835 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshifuji S, Tanaka K-I, Kawai T & Nitta Y Chemical conversion of cyclic α-amino acids to α-aminodicarboxylic acids by improved ruthenium tetroxide oxidation. Chem. Pharm. Bull 33, 5515–5521 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawamata Y et al. Scalable, electrochemical oxidation of unactivated C–H bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139, 7448–7451 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Annese C, D’Accolti L, Fusco C, Licini G & Zonta C Heterolytic (2e) vs homolytic (1e) oxidation reactivity: N–H versus C–H switch in the oxidation of lactams by dioxirans. Chem. Eur. J 23, 259–262 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cui L; Peng Y & Zhang L A two-step, formal [4+2] approach toward piperidin-4-ones via au catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 8394–8395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao J, Nanjo T, de Lucca EC & White MC Chemoselective methylene oxidation in aromatic molecules. Nat. Chem 11, 213–221 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen MS & White MC Combined effects on selectivity in Fe-catalyzed methylene oxidation. Science, 327, 566–571 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gormisky PE & White MC Catalyst-controlled aliphatic C–H oxidations with a predictive model for site-selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 135, 14052–14055 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osberger TJ, Rogness DC, Kohrt JT, Stepan AF & White MC Oxidative diversification of amino acids and peptides by small-molecule iron catalysis. Nature 537, 214–219 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milan M, Carboni G, Salamone M, Costas M & Bietti M Tuning selectivity in aliphatic C–H bond oxidation of N-alkylamides and phthalimides catalyzed by manganese complexes. ACS Catal. 7, 5903–5911 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nicolaou KC, Dolle RE, Chucholowski A & Randall JL Reactions of glycosyl fluorides. Synthesis of C-glycosides. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun 1153–1154 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Posner GH & Haines SR Conversion of glycosyl fluorides into c-glycosides using organoaluminum reagents. Stereospecific alkylation at C-6 of a pyranose sugar. Tetrahedron Lett. 26, 1823–1826 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mason JD & Weinreb SM Total syntheses of the monoterpenoid indole alkaloids (±)-alstoscholarisine B and C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 56, 16674–16676 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor RD, MacCoss M & Lawson ADG Rings in drugs. J. Med. Chem 57, 5845–5859 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vitaku E, Smith DT & Njardarson JT Analysis of the structural diversity, substitution patterns, and frequency of nitrogen heterocycles among U.S. FDA approved pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem 57, 10257–10274 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevens RV Nucleophilic additions to tetrahydropyridinium salts. Applications to alkaloid syntheses. Acc. Chem. Res 17, 289–296 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomooka K, Matsuzawa K, Suzuki K & Tsuchihashi G.-i. Lactols in stereoselection 2. Stereoselective synthesis of disubstituted cyclic ethers. Tetrahedron Lett. 28, 6339–6342 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lunn MR et al. Indoprofen upregulates the survival motor neuron protein through a cyclooxygenase-independent mechanism. Chem. Biol 11, 1489–1493 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howell JM, Feng K, Clark JR, Trzepkowski LJ & White MC Remote oxidation of aliphatic C–H bonds in nitrogen-containing molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 14590–14593 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prendergast MA et al. Central nicotinic receptor agonists ABT-418, ABT-089, and (−)-nicotine reduce distractibility in adult monkeys. Psychopharmacology 136, 50–58 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maryanoff BE et al. Pyrroloisoquinoline antidepressants. Potent, enantioselective inhibition of tetrabenazine-induced ptosis and neuronal uptake of norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin. J. Med. Chem 27, 943–946 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sugi K et al. Improved synthesis of paroxetine hydrochloride propan-2-ol solvate through one of metabolites in humans, and characterization of the solvate crystals. Chem. Pharm. Bull, 48, 529–536 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fujimoto J et al. Discovery of 3,5-diphenyl-4-methyl-1,3-oxazolidin-2-ones as novel, potent, and orally available Δ-5 desaturase (D5D) inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 60, 8963–8981 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kitamura M, Ohmori K & Suzuki K Divergent behavior of cobalt-complexed enyne having a leaving group. Tetrahedron Lett. 40, 4563–4566 (1999). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.