Abstract

Objective:

Previous research suggests that everyday discrimination is associated with worse concomitant performance in several cognitive domains, as well as faster subsequent declines in episodic memory. This study aimed to extend knowledge on the specificity, durability, and mechanisms of associations between everyday discrimination and cognition by using a comprehensive neuropsychological battery and a longitudinal mediation design.

Method:

Participants included 3,304 older adults in the Health and Retirement Study Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol. Discrimination was assessed using the Everyday Discrimination Scale. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the 8-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. Vascular diseases were quantified as the self-reported presence of hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to estimate episodic memory, executive functioning, processing speed, language, and visuoconstruction across a battery of 13 neuropsychological tests. Structural equation models controlled for sociodemographics and baseline cognition ascertained two to four years prior.

Results:

Discrimination was associated with more depressive symptoms and vascular diseases. Depressive symptoms mediated negative effects of discrimination on subsequent functioning across all five cognitive domains. Vascular diseases additionally mediated negative effects of discrimination on processing speed. After accounting for mediators, direct negative effects of discrimination remained for executive functioning and visuoconstruction.

Conclusions:

This national longitudinal study in the United States provides evidence for broad and enduring effects of everyday discrimination on cognitive aging, which appear to be partially mediated by mental and physical health. Future research should examine additional mechanisms as well as moderators of these associations to better understand points of intervention.

Keywords: Episodic memory, executive functioning, processing speed, language, visuoconstruction, aging, social stress

Social stressors have been linked to worse cognitive functioning in various domains. As a stressor, discrimination may be particularly detrimental to cognitive processes because identity-relevant stressors appear to be more psychologically damaging than those that threaten less valued role involvements (Thoits, 1991). Indeed, a growing body of research indicates that everyday discrimination is associated with various negative health consequences (Pascoe & Richman, 2009), including lower cognitive performance in samples of African American older adults (Barnes et al., 2012) and samples of middle-aged African American and non-Hispanic White adults (Zahodne, Manly, Smith, Seeman, & Lachman, 2017). While longitudinal data from racially diverse samples of middle aged and older adults are now available to indicate that everyday discrimination is associated with not only concurrent cognitive performance but also subsequent cognitive decline (Zahodne, Kraal, Sharifian, Zaheed, & Sol, 2019a; Zahodne et al., 2017), these studies have been limited to examinations of episodic memory, measured with a single word list learning task. Thus, there is a need to incorporate additional, well-characterized cognitive domains and a longitudinal design in order to determine the scope of discrimination’s effects on cognitive aging.

An early study in a sample of 407 African American older adults suggested some degree of domain specificity, as greater everyday discrimination was associated with worse performance on tests of episodic memory and perceptual speed, but not semantic memory, working memory, or visuospatial abilities (Barnes et al., 2012). Domain specificity may point to underlying mechanisms by which everyday discrimination interferes with cognitive functioning. For example, both episodic memory and processing speed deficits are commonly observed in the context of depressive symptoms (Bäckman & Forsell, 1994; Brewster, Peterson, Roker, Ellis, & Edwards, 2017; Sheline et al., 2006; Tsourtos, Thompson, & Stough, 2002). Both quantitative and qualitative research with African American adults suggests that the experience of discrimination can have a negative impact on mood (Broman, Mavaddat, & Hsu, 2000; Bullock & Houston, 1987), and depressive symptoms have been shown to mediate associations between discrimination and concomitant performance on a word list learning task in a population-representative sample of non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic older adults (Zahodne, Sol, & Kraal, 2019c).

In addition to depressive symptoms, vascular disease may contribute to the negative effects of discrimination on cognition. Indeed, a growing body of cross-sectional and longitudinal work documents links between more frequent experiences of discrimination and worse cardiovascular health in racially diverse adult samples (Beatty Moody et al., 2019; Lewis, Williams, Tamene, & Clark, 2014), particularly dysregulated blood pressure (Beatty Moody et al., 2016; Lewis et al., 2009). In turn, poorer cardiovascular health is a known contributor to poorer cognitive aging (Barnes, Alexopoulos, Lopez, Williamson, & Yaffe, 2006; Raz, Rodrigue, Kennedy, & Acker, 2007). The negative cognitive effects of cardiovascular disease appear to be strongest for cognitive domains of processing speed and executive functioning.

Theoretical (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999) and empirical (Lewis, Aiello, Leurgans, Kelly, & Barnes, 2010; Zahodne, Kraal, Zaheed, Farris, & Sol, 2019b) work in African American and/or racially diverse samples implicates stress-related physiological dysregulation in the negative health effects of everyday discrimination. However, previous work examining associations between discrimination and multiple cognitive domains did not incorporate a mediational framework to investigate potential psychological or physiological mechanisms underlying effects (Barnes et al., 2012).

The overall goal of the current study was to extend knowledge on the specificity, persistence, and mechanisms of associations between everyday discrimination and cognitive performance by using a comprehensive neuropsychological battery and a longitudinal mediation design. Data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) and its Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol (HCAP) were used to characterize prospective associations between discrimination and five cognitive domains, controlling for sociodemographic factors and previous cognitive ability. In addition, mediation models were used to quantify the extent to which longitudinal associations between discrimination and cognition were mediated by vascular disease burden and depressive symptoms. We hypothesized that more frequent discrimination would be associated with worse subsequent episodic memory, processing speed, and executive functioning, controlling for previous cognitive functioning. We also hypothesized that these associations would be at least partially mediated by elevated depressive symptoms and vascular disease burden.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Data were drawn from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). HRS is a nationally representative sample of Americans aged 51 and older initiated in 1992 (Sonnega & Weir, 2014). Details of the HRS longitudinal panel design, sampling, and all assessment instruments are available on the HRS website (http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu). Participants in HRS are interviewed every two years, either in person or over the phone. All core interviews include the collection of socioeconomic and health information, as well as brief cognitive measures (e.g., Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status). In-person interviews are conducted with a random half of the sample at every other interview wave and additionally include a leave-behind psychosocial questionnaire that participants complete and mail back to the study team. Therefore, these psychosocial data are available for approximately one half of the total HRS sample at any given study wave.

In 2016, the HRS initiated the Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol (HCAP), in which a subset of the sample was invited to participate in a comprehensive, in-person neuropsychological assessment that included multiple measures of episodic memory, executive functioning, processing speed, language, and visuoconstruction. Specifically, 26% of the HRS panel sample aged 65 and above were randomly selected. Of those, participants who had completed the 2016 core HRS interview and venous blood collection were invited to participate in HCAP. To ensure non-concurrent assessments of the predictor (i.e., everyday discrimination) and outcomes (i.e., cognitive domains) of interest, the current study used psychosocial and health data from the most recent wave prior to the 2016 HCAP (either 2012 or 2014). Thus, the study baseline was defined as either 2012 or 2014, dependent upon the wave at which a participant was eligible to participate in the enhanced face-to-face interview, which is determined via random assignment. Inclusion criteria were participation in HCAP, eligibility for the enhanced face-to-face interview in either 2012 or 2014, and availability of covariate data. Characteristics of the 3,304 individuals included in the current study are provided in Table 1. All participants provided written informed consent, and all study procedures were approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics at baseline (N=3,304)

| Mean (SD) or % | |

|---|---|

| Year (% 2012) | 47.43 |

| Age | 73.27 (7.54) |

| Gender (% women) | 60.44 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 71.43 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 15.68 |

| Hispanic (any race) | 10.71 |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 2.18 |

| Education (0-17) | 12.75 (3.16) |

| Annual household income (USD) | 61,513.14 (116185.67) |

| Household wealth (assets – debts in USD) | 504,160.53 (1079626.07) |

| Everyday discrimination (1-6) | 1.53 (0.72) |

| Vascular disease burden (0-3) | 1.22 (0.90) |

| Depressive symptoms (0-8) | 1.31 (1.88) |

| Global cognition (0-27) | 15.15 (4.34) |

Note. SD = Standard deviation; USD = United States dollars

Measures

Cognitive Outcomes.

Cognition was operationalized using latent variables corresponding to five distinct cognitive domains measured during the 2016 HCAP visit: episodic memory, executive functioning, processing speed, language, and visuoconstruction (Weir, Langa, & Ryan, 2016).

Episodic memory.

Episodic memory functioning was assessed with 10 indicators: Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Word List (Immediate, Delayed, and Recognition trials), CERAD Constructional Praxis (Delayed trial), Wechsler Memory Scale-IV (WMS-IV) Logical Memory (Immediate and Delayed trials), the Brave Man story task (Immediate and Delayed Recall Trials), and the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) delayed word recall.

Executive functioning.

Executive functioning was assessed with three indicators: Number Series, Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices, and Trail-Making Test Part B (time).

Processing speed.

Processing speed was assessed with four indicators: Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT), Trail-Making Test Part A (time), Backwards Counting, and Letter Cancellation.

Language.

Language was assessed with four indicators: animal fluency, the sum of two dichotomous item assessing naming to verbal description from the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS), the sum of two dichotomous items assessing visual confrontation naming from the MMSE, and a single dichotomous item assessing sentence writing from the MMSE.

Visuoconstruction.

Visuoconstruction was assessed with two indicators: CERAD Constructional Praxis (copy) and polygons from the MMSE.

Exposure

Everyday discrimination was assessed with the five-item Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997), administered as part of a leave-behind questionnaire in 2012 or 2014. Participants are asked how often a variety of experiences have happened to them in their “day-to-day life” without reference to a specific time period. Items included, “You are treated with less courtesy or respect than other people,” “You receive poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores,” “People act as if they think you are not smart,” “People act as if they are afraid of you,” and “You are threatened or harassed.” Items are rated for frequency on a 6-point Likert-type scale (1=Almost every day to 6=Never). In the current study, mean scores on the scale were reversed prior to analysis so that higher scores correspond to higher frequency of everyday discrimination. Internal consistency for this scale in the HRS is adequate (α = .82 in 2012 and 2014). In the current sample, non-Hispanic Black participants reported the highest levels of discrimination (1.63), followed by non-Hispanic Other (1.60), Hispanic (1.53), and non-Hispanic White (1.51) participants.

Mediators

Mediators included markers of physical and mental health in 2012 or 2014. Physical health was operationalized as vascular disease burden, which was quantified as the sum of the self-reported presence of the following three conditions: hypertension, diabetes, and heart problems. Mental health was operationalized as depressive symptoms at study baseline, which were assessed with eight dichotomous items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale (CESD; Radloff, 1977).

Covariates

Age (in years) corresponded to age at the time of the 2016 HCAP. Sex/gender was quantified as a dichotomous variable, and male was the reference category. Self-reported race and ethnicity was dummy-coded into four categories: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic (of any race), and non-Hispanic other. The largest category, non-Hispanic White, was treated as the reference group. Education was self-reported years of education (0-17). A dichotomous variable represented the study baseline (2012 or 2014), with 2012 as the reference category. Cognitive functioning at study baseline (2012 or 2014) was assessed with a global cognition summary score, which sums across 10-word immediate recall, 10-word delayed recall, Serial 7s, and Backward Counting and ranges from 0 to 27. As the indicator of socioeconomic status that is most strongly associated with cognition (Lee, Kawachi, Berkman, & Grodstein, 2003), only education was included in the primary analytic models, but sensitivity analyses additionally controlled for annual household income and household wealth (i.e., assets minus debts).

Analytic Strategy

Descriptive statistics were computed in SPSS, version 25. All other models were conducted in Mplus, version 8 using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors. Missing data were managed with full information maximum likelihood. Missing data on the cognitive outcomes ranged from 16.9% (Number Series) to 0.1% (Animals) of the sample. Model fit was evaluated with the following commonly-used indices: comparative fit index (CFI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root-mean square residual (SRMR). CFI > 0.95, RMSEA < 0.08, and SRMR < 0.08 were used as criteria for adequate model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Cognitive outcomes were summarized using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) in the larger HCAP sample (n=3,346) based on theoretical grouping. Indicators corresponding to TICS and MMSE items were treated as categorical variables, and all other indicators were treated as continuous. Indicators from the same test (e.g., Trail-Making Test Parts A & B) were allowed to covary.

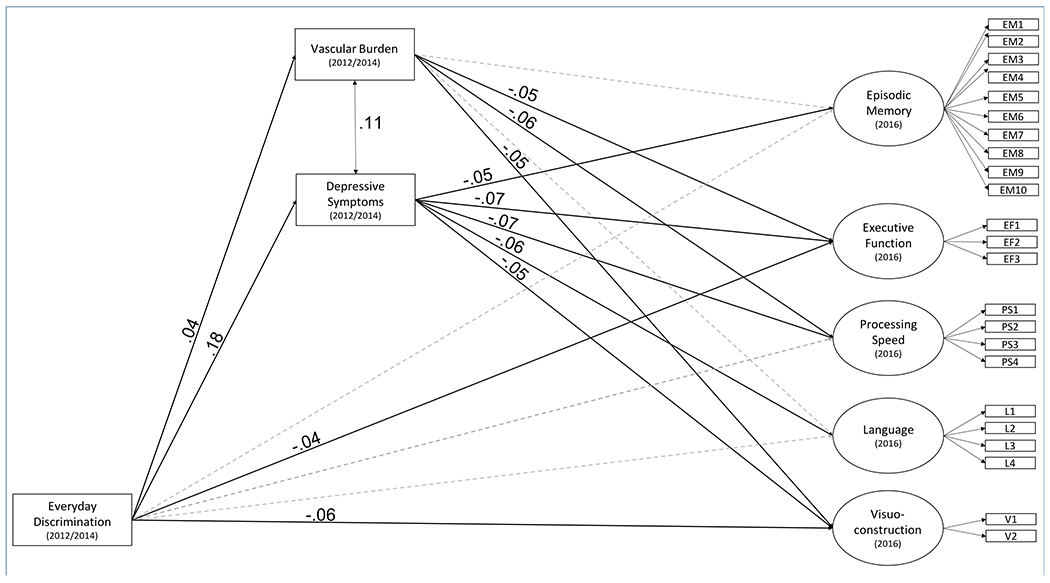

Regression paths were then added to the measurement model to examine associations between everyday discrimination and latent variables corresponding to episodic memory, executive functioning, processing speed, language, and visuoconstruction through the physical and mental health mediators. Figure 1 depicts the mediation model. Specifically, all cognitive domains were regressed onto the mediators (vascular burden and depressive symptoms), exposure (everyday discrimination), and covariates (age, sex/gender, race/ethnicity, education, baseline cognition, and baseline year). In addition, both mediators (vascular burden and depressive symptoms) were regressed onto the exposure (everyday discrimination) and all covariates. The mediators were allowed to covary. Finally, the exposure (everyday discrimination) was regressed onto all covariates. In the mediation model, indirect effects refer to product of the association between everyday discrimination and a mediator (vascular burden or depressive symptoms) and the association between that mediator and a cognitive outcome, independent of all covariates. Direct effects refer to the association between everyday discrimination and a cognitive outcome, independent of both mediators and all covariates. Total effects refer to the sum of direct and indirect effects, corresponding to the association between everyday discrimination and a cognitive outcome, independent of all covariates.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal Mediation Model of Everyday Discrimination on Cognitive Functioning through Physical and Mental Health Pathways. Solid black lines depict significant paths, and gray, dotted lines depict nonsignificant paths. Standardized Estimates are shown. For simplicity, covariates and covariances between the cognitive domains are not depicted.

Results

Measurement Model

The CFA model fit well (CFI = .962, RMSEA = .040, SRMR = 0.035), confirming that the HCAP neuropsychological battery adequately assesses cognitive domains of episodic memory, executive functioning, language, speed, and visuoconstruction. As shown in Table 2, all indicators loaded onto their respective factors with no standardized loadings below .56.

Table 2.

Standardized factor loadings from the measurement model

| Estimate | SE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Episodic Memory | |||

|

| |||

| Word List Immediate | .79 | .01 | <.001 |

| Logical Memory Immediate | .73 | .01 | <.001 |

| Brave Man Immediate | .61 | .01 | <.001 |

| Word List Delayed | .76 | .01 | <.001 |

| Logical Memory Delayed | .71 | .01 | <.001 |

| Brave Man Delayed | .60 | .01 | <.001 |

| MMSE Word List Delayed | .61 | .01 | <.001 |

| Word List Recognition | .63 | .01 | <.001 |

| Logical Memory Recognition | .62 | .01 | <.001 |

| Constructional Praxis - Delay | .73 | .01 | <.001 |

|

| |||

| Executive Functioning | |||

|

| |||

| Raven’s | .86 | .01 | <.001 |

| Number Series | .67 | .01 | <.001 |

| Trails B | −.67 | .01 | <.001 |

|

| |||

| Processing Speed | |||

|

| |||

| Symbol Digit Modalities Test | .90 | .01 | <.001 |

| Trails A | −.74 | .01 | <.001 |

| Backward Counting | .69 | .01 | <.001 |

| Letter Cancellation | .70 | .01 | <.001 |

|

| |||

| Language | |||

|

| |||

| Animal Fluency | .77 | .01 | <.001 |

| TICS Naming | .75 | .02 | <.001 |

| MMSE Naming | .62 | .05 | <.001 |

| MMSE Writing | .56 | .03 | <.001 |

|

| |||

| Visuoconstruction | |||

|

| |||

| Constructional Praxis - Copy | .75 | .02 | <.001 |

| MMSE Polygons | .64 | .02 | <.001 |

Note. MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination. TICS = Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status.

Mediation Model

Next, the predictor of interest (everyday discrimination), mediators (vascular burden and depressive symptoms), and covariates were added to the measurement model. The model fit well (CFI = .952, RMSEA = .039, SRMR = 0.065). As shown in Table 3, there were total effects of everyday discrimination at baseline on subsequent executive functioning, processing speed, and visuosconstruction, but not episodic memory or language. There were indirect effects of more frequent everyday discrimination on worse subsequent cognitive performance across all five domains through more depressive symptoms. In addition, there was an independent indirect effect of higher everyday discrimination on worse subsequent processing speed through vascular burden. Accounting for the indirect effects, direct effects of more frequent everyday discrimination on worse executive functioning and visuosconstruction remained significant.

Table 3.

Standardized effects of baseline discrimination on follow-up performance within each cognitive domain

| Total Effect |

Indirect Effect Through CESD |

Indirect Effect Through VASC |

Direct Effect |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Episodic memory | −.004 | .015 | −.009* | .003 | .000 | .001 | .005 | .015 |

| Executive functioning | −.054* | .014 | −.014* | .003 | −.002 | .001 | −.039* | .014 |

| Processing speed | −.041* | .015 | −.014* | .003 | −.002* | .001 | −.025 | .015 |

| Language | −.023 | .019 | −.011* | .004 | −.001 | .001 | −.012 | .019 |

| Visuoconstruction | −.072* | .021 | −.008* | .004 | −.002 | .001 | −.062* | .022 |

= p < .05

Note. CESD = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, VASC = Vascular Burden

In a sensitivity analysis that covaried for annual household income and household wealth as additional indicators of socioeconomic status, the pattern of results was unchanged with one exception. Specifically, the indirect effect of discrimination on processing speed through vascular health was no longer statistically significant (p=0.055), though the effect size was identical to that in the primary analytic model (standardized estimate = −.002).

Discussion

The current study provides evidence for broad and enduring effects of everyday discrimination on cognitive functioning across multiple domains. Specifically, greater everyday discrimination was prospectively associated with worse cognitive functioning in multiple domains two to four years later, even after adjusting for baseline cognitive ability. These associations were only partially explained by greater depressive symptoms and vascular disease burden.

The finding that greater everyday discrimination at baseline was associated with worse cognitive functioning across multiple domains two to four years later extends a previous cross-sectional study that included a comprehensive neuropsychological battery (Barnes et al., 2012). While both the current study and that of Barnes and colleagues (2012) documented a negative association between everyday discrimination and processing speed, a novel finding of this study was that greater everyday discrimination was also associated with worse executive functioning and visuoconstruction. These domains were not included in the cross-sectional study by Barnes et al. (2012), though it is noted that one test included in the executive functioning factor in the current study (i.e., Raven’s) was also included in the visuospatial ability factor in the study by Barnes et al. (2012). Further, the current study found additional indirect effects of everyday discrimination on episodic memory, language, and visuoconstruction through depressive symptoms and/or vascular diseases. Thus, this study provides evidence that everyday discrimination may have lasting effects on a broad set of cognitive domains.

Interestingly, associations involving all five cognitive domains appeared to be, in part, driven by depressive symptoms. Both qualitative and quantitative research has identified depressive symptoms as a consequence of discriminatory experiences (Broman, Mavaddat, & Hsu, 2000; Bullock & Houston, 1987). Further, depressive symptoms are commonly associated with slowed processing speed (Tsourtos et al., 2002), worse episodic memory (Bäckman & Forsell, 1994; Zakzanis, Leach, & Kaplan, 1998), and worse executive functioning (Hasselbalch, Knorr, Hasselbalch, Gade, & Kessing, 2012). Research on the association between depressive symptoms and language has been mixed (Henry & Crawford, 2005), but it is notable that the strongest indicator of language in the current study was a speeded test (i.e., animal fluency). Psychomotor slowing is a core symptom of depression (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), and slowed processing speed has been reported to mediate the negative impact of depressive symptoms on other cognitive domains (Blair et al., 2016).

Above and beyond depressive symptoms, there were also significant indirect effects of everyday discrimination on cognition through vascular disease burden. Everyday discrimination was significantly associated with greater vascular burden, and greater vascular burden was, in turn, associated with worse subsequent processing speed, executive functioning, and visuoconstruction. However, the overall indirect effect was only significant for processing speed, which also exhibited the largest association with vascular disease burden, consistent with previous studies (D. E. Barnes et al., 2006; Raz et al., 2007). Of note, associations between everyday discrimination and vascular health in the current study were smaller than associations between everyday discrimination and depressive symptoms, which may explain the fewer number of significant indirect effects involving vascular burden (i.e., product of the path from everyday discrimination to vascular diseases and paths from vascular diseases to an individual cognitive domain). One reason for this discrepancy may relate to differences in the measurement of depressive symptoms (i.e., validated 8-item questionnaire) versus vascular disease burden (i.e., presence/absence of three vascular health conditions). It is possible that using more comprehensive and/or fine-grained measures of vascular health would have allowed us to observe indirect effects involving other cognitive outcomes. Nonetheless, the finding that more frequent everyday discrimination was associated with worse vascular health is in line with substantial previous research, including studies of cardiovascular diseases (Beatty Moody et al., 2019; Everson-Rose et al., 2015; Lewis et al., 2014), blood pressure (Beatty Moody et al., 2016; Lewis et al., 2009), and inflammation (Beatty Moody, Brown, Matthews, & Bromberger, 2014; Lewis et al., 2010; Zahodne et al., 2019a, 2019b), which is both a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and an indicator of cardiovascular disease severity.

In contrast to processing speed, associations between everyday discrimination and cognitive domains of executive functioning and visuoconstruction were significant even after adjusting for depressive symptoms and vascular health, implicating additional potential mechanisms, such as anxiety, vigilance to threats, and/or motor functioning. Additional research is needed to understand the specific mechanisms underlying links between everyday discrimination and lower executive and visoconstructional abilities.

While not the focus of the current study, the impact of everyday discrimination on cognitive health may reflect neurobiological mechanisms. The biopsychosocial model described by Clark and colleagues (1999) proposes that, as a stressor, discrimination can initiate physiological stress responses, including activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. In turn, elevated levels of circulating glucocorticoids can damage the brain, particularly regions with high densities of glucocorticoid receptors such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Jamieson & Dinan, 2001; Juster, McEwen & Lupien, 2010; Dedovic, Duchesne, Andrews, Engert & Pruessner, 2009; Lupien et al., 1998). These brain regions are key components of the neurocircuitry that directly supports higher cognitive functioning. Stress pathways linking everyday discrimination to cognition likely overlap with mechanistic pathways involving depressive symptoms and cardiovascular risk. Limitations of this study include the availability of only one time point of a comprehensive neuropsychological battery, though all models controlled for a gross measure of cognitive ability at baseline. It should also be noted that some cognitive domains were assessed more comprehensively than others. For example, the latent episodic memory factor was indicated by a relatively large number of validated measures including a variety of visual and verbal memoranda, while the latent language and visuoconstruction factors included dichotomous indicators from mental status screeners. Future studies should include more comprehensive sets of tests measuring these latter constructs.

Future research should also examine additional mediators (e.g., health behaviors), as well as moderators (e.g., contextual factors), of associations among discrimination, mental and physical health, and cognitive aging to better understand potential points of intervention. Indeed, contextual factors such as social connectedness and rurality may not only influence the level of everyday discrimination experienced by individuals, but also moderate its impact (de Souza Braga et al., 2019; Johnson et al., in press; Herrera, 2009). For example, a recent cross-sectional study in the HRS reported that living in an urban context was associated with a stronger negative association between everyday discrimination and verbal episodic memory among non-Hispanic Blacks (Johnson et al., in press). Additional studies with comprehensive neuropsychological batteries should consider mediators and moderators in the context of race, as the current HCAP subsample comprised relatively low proportions of racial/ethnic minorities.

The current study operationalized everyday discrimination independent of the reason(s) underlying discriminatory experiences in order to maximize comparability with relevant extant literature using this measure (Everson-Rose et al., 2015; Friedman, Williams, Singer, & Ryff, 2009; Richman, Pek, Pascoe, & Bauer, 2010; Shankar & Hinds, 2017; Zahodne, Sol, & Kraal, 2019). Future studies could incorporate data on attributions, as well as intersectional identities. Importantly, associations between discrimination and health have been documented across sociodemographic groups and regardless of attributions. Given that reports of discrimination in this study were racially/ethnically patterned such that non-Hispanic Blacks reported the highest levels, in line with previous studies (Barnes et al., 2004), our findings may have important implications for racial/ethnic inequalities in cognitive aging. Specifically, previous work indicating that everyday discrimination represents a key mediator of inequalities in memory aging (Zahodne, Sol, & Kraal, 2019) may be extended to inequalities in other cognitive domains.

Strengths of this study include the large, national sample followed longitudinally, as well as the availability of multiple neuropsychological measures that allowed us to extend previous research on the specificity, durability, and mechanisms of the negative cognitive effects of discrimination. It is important to note that the HRS was designed as a U.S. population-representative sample of adults aged 51 and older rather than a clinical cohort. As such, prevalence of depressive symptoms, vascular diseases, and discrimination are relatively low and in line with other similar community-based cohorts. Future research is needed to determine whether patterns of association documented in the current study exist in various clinical populations.

In conclusion, this national longitudinal study in the United States provides evidence for broad and enduring associations between everyday discrimination and cognitive aging, which appear to be at least partially mediated by depressive symptoms and poorer vascular health. More comprehensive biopsychosocial models are needed to more fully understand the longitudinal effects of discrimination on cognitive aging. This knowledge may guide future prevention and intervention efforts aimed at facilitating healthy cognitive aging at both individual and group levels.

Key Points.

Question: What is the key question this paper addresses?

How do everyday experiences of discrimination relate to later cognitive aging?

Findings: What are the primary findings?

Experiencing more frequent everyday discrimination is associated with worse cognitive functioning in multiple domains two to four years later, in part due to the negative effects of discrimination on depressive symptoms and vascular health.

Importance: What are the key scientific and practical implications of the findings?

Social stress has the potential to influence cognitive aging, which can help us to understand and combat health disparities.

Next Steps: What directions should be explored in future research?

Future research should examine factors that modify and interrupt risk pathways involving social stress.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes on Aging [grant numbers AG059300 and AG054520]. The HRS (Health and Retirement Study) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan. The sponsor had no role in the current analyses or the preparation of this paper. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckman L, & Forsell Y (1994). Episodic memory functioning in a community-based sample of old adults with major depression: Utilization of cognitive support. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103(2), 361–370. 10.1037/0021-843X.103.2.361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes DE, Alexopoulos GS, Lopez OL, Williamson JD, & Yaffe K (2006). Depressive symptoms, vascular disease, and mild cognitive impairment: Findings from the cardiovascular health study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes LL, Lewis TT, Begeny CT, Yu L, Bennett DA, & Wilson RS (2012). Perceived discrimination and cognition in older African Americans. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 10.1017/S1355617712000628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes LL, Mendes De Leon CF, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, & Evans EA (2004). Racial differences in perceived discrimination in a community population of older Blacks and Whites. Journal of Aging and Health, 16, 315–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty Moody DL, Brown C, Matthews KA, & Bromberger JT (2014). Everyday discrimination prospectively predicts inflammation across 7-years in racially diverse midlife women: Study of women’s health across the nation. Journal of Social Issues. 10.1111/josi.12061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty Moody DL, Taylor AD, Leibel DK, Al-Najjar E, Katzel LI, Davatzikos C, … Waldstein SR (2019). Lifetime discrimination burden, racial discrimination, and subclinical cerebrovascular disease among African Americans. Health Psychology. 10.1037/hea0000638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty Moody DL, Waldstein SR, Tobin JN, Cassells A, Schwartz JC, & Brondolo E (2016). Lifetime racial/ethnic discrimination and ambulatory blood pressure: The moderating effect of age. Health Psychology, 35(4), 333–342. 10.1037/hea0000270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair M, Gill S, Gutmanis I, Smolewska K, Warriner E, & Morrow SA (2016). The mediating role of processing speed in the relationship between depressive symptoms and cognitive function in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology 10.1080/13803395.2016.1164124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster GS, Peterson L, Roker R, Ellis ML, & Edwards JD (2017). Depressive symptoms, cognition, and everyday function among community-residing older adults. Journal of Aging and Health. 10.1177/0898264316635587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman CL, Mavaddat R, & Hsu SY (2000). The experience and consequences of perceived racial ciscrimination: A study of African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology 10.1177/0095798400026002003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock SC, & Houston E (1987). Perceptions of racism by black medical students attending white medical schools. Journal of the National Medical Association. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, & Williams DR (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comijs HC, Kriegsman DMW, Dik MG, Deeg DJH, Jonker C, & Stalman WAB (2009). Somatic chronic diseases and 6-year change in cognitive functioning among older persons. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 48(2), 191–196. 10.1016/j.archger.2008.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedovic K, Duchesne A, Andrews J, Engert V & Pruessner JC (2009).The brain and the stress axis: the neural correlates of cortisol regulation in response to stress. Neuroimage, 47, 864–871. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza Braga L, Teixeira Caiaffa W, Romanelli Ceolin AP, de Andrade FB, & Lima-Costa MF (2019). Perceived discrimination among older adults living in urban and rural areas in Brazil: a national study (ELSI-Brazil). BMC Geriatrics, 19, 10.1186/s12877-019-1076-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson-Rose SA, Lutsey PL, Roetker NS, Lewis TT, Kershaw KN, Alonso A, & Diez Roux AV (2015). Perceived discrimination and incident cardiovascular events: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. American Journal of Epidemiology. 10.1093/aje/kwv035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman EM, Williams DR, Singer BH, & Ryff CD (2009). Chronic discrimination predicts higher circulating levels of E-selectin in a national sample: The MIDUS study. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon SA, & Wagner AD (2016). Acute stress and episodic memory retrieval: Neurobiological mechanisms and behavioral consequences. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 10.1111/nyas.12996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselbalch BJ, Knorr U, Hasselbalch SG, Gade A, & Kessing LV (2012). Cognitive deficits in the remitted state of unipolar depressive disorder. Neuropsychology. 10.1037/a0029301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, & Crawford JR (2005, February 23). A meta-analytic review of verbal fluency deficits in depression. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 10.1080/138033990513654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera DE (2009). Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, hope, and social connectedness: Examining the predictors of future orientation among emerging adults. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson K & Dinan TG (2001). Glucocorticoids and cognitive function: from physiology to pathophysiology. Hum Psychopharmacol, 16, 293–302. 10.1002/hup.304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jassal SV, Roscoe J, LeBlanc D, Devins GM, & Rourke S (2008). Differential impairment of psychomotor efficiency and processing speed in patients with chronic kidney disease. International Urology and Nephrology. 10.1007/s11255-008-9375-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KE, Sol K, Sprague BN, Cadet T, Munoz E, & Webster NJ (in press). The impact of region and urbanicity on the discrimination-cognitive health link among older Blacks. Research in Human Development. DOI: 10.1080/15427609.2020.1746614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juster RP, McEwen BS, Lupien SJ (2010). Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35, 2–16. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Kawachi I, Berkman LF, & Grodstein F (2003). Education, other socioeconomic indicators, and cognitive function. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157, 712–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TT, Aiello AE, Leurgans S, Kelly J, & Barnes LL (2010). Self-reported experiences of everyday discrimination are associated with elevated C-reactive protein levels in older African-American adults. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TT, Barnes LL, Bienias JL, Lackland DT, Evans DA, & Mendes De Leon CF (2009). Perceived discrimination and blood pressure in older African American and white adults. Journals of Gerontology - Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 10.1093/gerona/glp062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TT, Williams DR, Tamene M, & Clark CR (2014). Self-reported experiences of discrimination and cardiovascular disease. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports. 10.1007/s12170-013-0365-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, de Leon M, de Santi S, Convit A, Tarshish C, Nair NP, Thakur M, McEwen BS, Hauger RL, Meaney MJ (1998). Cortisol levels during human aging predict hippocampal atrophy and memory deficits. Nature Neuroscience, 1, 69–73. 10.1038/271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman L, Nordin S, Bergdahl J, Birgander LS, & Neely AS (2007). Cognitive function in outpatients with perceived chronic stress. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health, 33(3), 223–232. 10.5271/sjweh.1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, & Richman LS (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 10.1037/a0016059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, & Acker JD (2007). Vascular health and longitudinal changes in brain and cognition in middle-aged and older adults. Neuropsychology. 10.1037/0894-4105.21.2.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman LS, Pek J, Pascoe E, & Bauer DJ (2010). The effects of perceived discrimination on ambulatory blood pressure and affective responses to interpersonal stress modeled over 24 hours. Health Psychology. 10.1037/a0019045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B (2000). Glucocorticoids and the regulation of memory consolidation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 10.1016/S0306-4530(99)00058-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B (2002). Stress and memory: Opposing effects of glucocorticoids on memory consolidation and memory retrieval. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 10.1006/nlme.2002.4080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, Griffith QK, Buranday J, De Quervain DJF, & McGaugh JL (2003). The hippocampus mediates glucocorticoid-induced impairment of spatial memory retrieval: Dependence on the basolateral amygdala. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 10.1073/pnas.0337480100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar A, & Hinds P (2017). Perceived discrimination: Associations with physical and cognitive function in older adults. Health Psychology. 10.1037/hea0000522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheline YI, Barch DM, Garcia K, Gersing K, Pieper C, Welsh-Bohmer K, … Doraiswamy PM (2006). Cognitive function in late life depression: Relationships to depression severity, cerebrovascular risk factors and processing speed. Biological Psychiatry, 60(1), 58–65. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnega A, & Weir DR (2014). The Health and Retirement Study: A public data resource for research on aging. Open Health Data, 2(1). 10.5334/ohd.am [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA (1991). On merging identity theory and stress research. Social Psychology Quarterly, 54(2), 101. 10.2307/2786929 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsourtos G, Thompson JC, & Stough C (2002). Evidence of an early information processing speed deficit in unipolar major depression. Psychological Medicine. 10.1017/S0033291701005001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir DR, Langa KM, & Ryan LH (2016). 2016 Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol (HCAP): Study Protocol Summary. Retrieved October 22, 2019, from http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/index.php?p=shoavail&iyear=ZU%5D [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, & Anderson NB (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health. Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 10.1177/135910539700200305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahodne LB, Kraal AZ, Sharifian N, Zaheed AB, & Sol K (2019a). Inflammatory mechanisms underlying the effects of everyday discrimination on age-related memory decline. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 75, 149–154. 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahodne LB, Kraal AZ, Zaheed A, Farris P, & Sol K (2019b). Longitudinal effects of race, ethnicity, and psychosocial disadvantage on systemic inflammation. SSM - Population Health, 7. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahodne LB, Manly JJ, Smith J, Seeman T, & Lachman ME (2017). Socioeconomic, health, and psychosocial mediators of racial disparities in cognition in early, middle, and late adulthood. Psychology and Aging, 32(2), 118–130. 10.1037/pag0000154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahodne LB, Sol K, & Kraal Z (2019c). Psychosocial pathways to racial/ethnic inequalities in late-life memory trajectories. Journals of Gerontology - Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74(3), 409–418. 10.1093/geronb/gbx113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakzanis KK, Leach L, & Kaplan E (1998). On the nature and pattern of neurocognitive function in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology and Behavioral Neurology. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zunszain PA, Anacker C, Cattaneo A, Carvalho LA, & Pariante CM (2011). Glucocorticoids, cytokines and brain abnormalities in depression. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 35(3), 722–729. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]