Abstract

Introduction:

Breast cancer diagnosis at a very young age has been independently correlated with worse outcomes. Appropriately intensifying treatment in these patients is warranted, even as we acknowledge the risks of potentially mutagenic adjuvant therapies. We examined local control, distant control, overall survival, and secondary malignancy rates by age cohort and by initial surgical strategy.

Methods:

Female patients less than or equal to 35 years of age diagnosed with invasive breast cancer from January 1, 1990 to December 31, 2010 were identified. Control groups age 36–50 years (n = 6246) and age 51–70 years (n = 7294) were delineated from an institutional registry. Clinicopathological and follow-up information was collected. Chi-squared test was utilized to compare frequencies of categorical variables. Survival endpoints were evaluated using Kaplan Meier methodology.

Results:

529 patients ≤35 years of age met criteria for analysis. The median age of diagnosis was 32 years (range 20–35). Median follow-up was 10.3 years. On multivariable analysis, factors associated with OS were tumor size (HR 1.14, p=0.02), presence of LVI (HR 2.2, p<0.001), ER positivity (HR 0.64, p=0.015), receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy (HR 0.52, p=0.035), and black race (HR 2.87, p<0.001). The ultra-young were more likely to experience local failure compared to the age 36–50 group (HR 2.2, 95% CI 1.8 – 2.6, p<0.001) and age 51–70 group (HR 3.1, 95% CI 2.45 – 3.9, p<0.001). The cumulative incidence of secondary malignancies at 5- and 10-years was 2.2% and 4.4%, respectively. Receipt of radiation was not significantly associated with secondary malignancies or contralateral breast cancer.

Discussion:

Survival and recurrence outcomes in breast cancer patients ≤35 years are worse compared to those ages 36–50 or 51–70 years. Based on our data, BCT is appropriate for these patients, and the concern for second malignancies should not impinge on the known indications for post-operative radiotherapy.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed non-skin cancer in women under the age of 40, comprising 30% of all cancer diagnoses in this group.1 Despite making up only 5.6% of all invasive breast cancer cases in the US, women of this age group are disproportionately more likely to suffer higher rates of recurrences2–4 and worse overall survival compared to older patients1,4,5. Two observations likely underpin these outcomes. One, a higher proportion of women diagnosed under the age of 40 present with more advanced stages of disease, including regional or distant disease1,6. Historically, this age group has not been recommended to undergo routine mammography in the absence of significantly increased breast cancer risk, (e.g. in known BRCA1/2 mutation carriers). Secondly, breast cancer in very young women is hypothesized to represent a distinct tumor biology, independent of known germline drivers7. Several studies have noted that young women tend to have worse histologic features, including high grade, presence of LVI, and absence of hormone receptors8–10. Interestingly, young age has been independently correlated with worse outcomes after adjusting for clinicopathologic features11–13, and recent studies report that these young patients have higher risks of mortality and recurrence even in early stage disease and favorable luminal A/B subtypes compared to older women3,9,12–15. On this basis, more aggressive treatment approaches, including mastectomy (as opposed to breast conservation) and the addition of adjuvant therapies, are sometimes justified. These considerations have to be weighed against the unique sensitivities of very young women who are breast cancer survivors including the potential for long-term treatment related toxicities.

In this study, we examined local control, distant control, and overall survival in a cohort of women age ≤35 years of age, compared to two older cohorts. Prior studies reported varying utilization and outcomes of breast conservation therapy (BCT) and mastectomy; we compared disease control rates within the age ≤35 cohort by surgical strategy. We then investigated the risk of secondary malignancy and contralateral breast cancer with use of adjuvant radiotherapy.

Patients and Methods

With IRB approval, a population-based retrospective study was conducted using a query of an institutional database to identify female patients age less than or equal to 35 years diagnosed with invasive breast cancer from January 1, 1990 to December 31, 2010. This time period was chosen to allow sufficient follow up time to observe disease recurrence rates, contralateral breast cancers, and other secondary malignancies. For comparison, two control cohorts treated during the same interval were delineated using the institution registry, one group age 36–50 years (n = 6244) and another age 51–70 years (n = 7292), approximating the cut-off for menopause. Patients who did not receive surgery, were stage IV at diagnosis, or had incomplete medical records were excluded. Patient demographics, germline status, surgical pathology, disease stage, treatment details, and follow-up information were collected from the electronic medical records. Final pathologic staging was performed using the 7th edition of the American joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM classification system. The year 2000 as a cutoff was included as a categorical variable since previous analysis by Frandsen et al. utilized this variable to approximate the increasing usage of anthracycline-based chemotherapy in patients under 70, combination of hormonal and chemotherapeutic agents in patients under 50 and radiation boosts following whole breast irradiation, and demonstrated that relapse-free survival was improved following this date16. This time threshold also marks the widespread adoption of Her-2 testing and the approval and use of trastuzumab. Second malignancy and contralateral breast cancer rates were abstracted directly from charts in the group ≤35 and using subsequent diagnoses codes in the control groups.

Continuous values are summarized using the median and range and assessed with Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests. Chi-squared and Fisher’s exact test was utilized to compare frequencies of categorical variables across age group and across upfront treatment categories for the <35 cohort. Overall survival, disease free survival, local control, distant control, time to second malignancy, and time to contralateral breast cancer were calculated as the difference from the time of diagnosis to date of death, date of any recurrence, date of locoregional recurrence, date of distant recurrence, date of second malignancy, and date of contralateral breast cancer, respectively. Overall survival and disease-free survival were evaluated using Kaplan Meier methodology. All other endpoints were analyzed using Fine-Gray models with a competing risk of death. Variables significant on univariate analyses were incorporated into multivariate models. All analyses used two-tailed tests with P < 0.05 and were performed using R version 3.6.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing©, Vienna, Austria; www.r-project.org).

Results

Patient Characteristics

529 patients in the age ≤35 cohort met criteria for analysis. The median age of diagnosis was 32 years (range 20–35). Median follow-up was 10.3 years. Demographically, 12% identified as black, 6% as Hispanic and 8% as Ashkenazi. 32% of the cohort had a history of smoking, and 61% had a history of alcohol use with the majority (49%) drinking socially. A known family history of breast cancer was reported by 51% of patients. Germline mutations in BRCA1/2 or other genes associated with heritable breast cancer were present in 42 (15%) of 289 patients with available genetic testing records. Prior to the 1999 publication of the NCCN guidelines recommending genetic testing for young women, the annual rate of testing was approximately 42% but then steadily rose to 89–100% by the end of the study period. Patient and tumor factors by age cohort are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1:

Clinicopathological features by age cohort: ≤35 vs. 36–50 vs. 51–70

| ≤35 (N=529) | 36–50 (N=6246) | 51–70 (N=7294) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histology N (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Invasive Ductal | 480 (91) | 4619 (74) | 5317 (73) | |

| Invasive Lobular | 8 (2) | 468 (7.5) | 748 (10) | |

| Mixed Invasive | 15 (3) | 371 (5.9) | 509 (7.0) | |

| Other | 26 (5) | 788 (13) | 718 (10) | |

| Unknown | 2 | |||

| Histologic Grade N (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | 43 (8.4) | 321 (6.6) | 425 (7.4) | |

| 2 | 98 (19) | 1348 (28) | 1717 (30) | |

| 3 | 373 (73) | 3193 (66) | 3598 (63) | |

| Unknown | 15 | 1384 | 1553 | |

| Tumor Size (cm) | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Interquartile Range) | 1.8 (1.2–2.5) | 1.5 (0.9–2.2) | 1.3 (0.8–2) | |

| Unknown | 10 | 1085 | 857 | |

| LN positive N (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Positive | 278 (53) | 2549 (41) | 2591 (36) | |

| Negative | 251 (47) | 3697 (59) | 4703 (64) | |

| LVI N (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Positive | 210 (45) | 1992 (39) | 1826 (30) | |

| Negative | 258 (55) | 3080 (61) | 4315 (70) | |

| Unknown | 61 | 1174 | 1153 | |

| Estrogen Receptor N (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Positive | 328 (64) | 4263 (78) | 5229 (79) | |

| Negative | 188 (36) | 1235 (22) | 1412 (21) | |

| Unknown | 13 | 748 | 653 | |

| Progesterone Receptor N (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Positive | 282 (55) | 3726 (68) | 3935 (60) | |

| Negative | 231 (45) | 1729 (32) | 2657 (40) | |

| Unknown | 16 | 791 | 702 | |

| Her2Neu N (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Positive | 95 (23) | 727 (15) | 711 (12) | |

| Negative | 326 (77) | 4146 (85) | 5306 (88) | |

| Unknown | 108 | 1373 | 1277 | |

| Axillary dissection N (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 321 (61) | 3194 (51) | 3165 (43) | |

| Unknown | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sentinel LN bx N (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 278 (53) | 4459 (71) | 5578 (76%) | |

| Unknown | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Chemo adjuvant N (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 465 (90) | 3966 (63) | 3901 (53) | |

| Unknown | 11 | 0 | 0 | |

| Chemo neoadjuvant N (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 37 (7.1) | 491 (7.9) | 360 (4.9) | |

| Unknown | 9 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hormonal therapy N (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 321/328 (98) | 4229/4263 (99) | 5141/5229 (98) | |

| Unknown | 16 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mastectomy reconstruction N (% of Mastectomy Pts) | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 179/196 (91) | 2591/3847 (67) | 1393 (44) | |

| Unknown | 2 | 2374 | 4108 | |

Tumor characteristics in breast cancer patients ≤35

Younger patients were more likely to have invasive ductal histology, lymph node positivity on pathology, LVI, ER/PR negativity, and presence of HER2-neu amplification. Invasive ductal histology comprised the majority of cases (91%). Seventy-three percent were histologic grade 3. Median tumor size was 1.8 cm with a range of 1.2 to 2.5 cm. Lymph nodes were pathologically positive in 53% of patients, and the number of positive lymph nodes ranged from 1 to 31 nodes with a median of 2. Estrogen and progesterone receptor status was positive in 64% and 55% of patients, respectively. HER2-neu was amplified in 23% of patients.

Treatment in breast cancer patients ≤35

Among the young cohort, 280 patients (54%) underwent breast conservation therapy while another 40 patients (8%) received lumpectomy without identifiable records on the use of adjuvant radiotherapy. One-hundred and ninety-six patients (38%) underwent mastectomy, 61% of whom received post-mastectomy radiation therapy. Table 2 compares patient characteristics by upfront treatment. Ninety-one percent of patients underwent reconstructive surgery. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy was administered to 7% and 90% of patients, respectively. Among the 328 patients with hormone receptor positivity, 98% of patients received adjuvant hormonal therapy. Adjuvant trastuzumab therapy was delivered in 58% of patients with HER2-neu amplifications.

Table 2:

Demographics and clinicopathologic features of patients 35 or younger by initial local treatment strategy

| Partial mastectomy + RT (N=280) | Partial mastectomy (N=40) | Mastectomy + RT (N=120) | Mastectomy (N=76) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race N (%) | 0.95 | ||||

| White | 210 (77) | 31 (78) | 92 (79) | 54 (72) | |

| African American | 31 (11) | 5 (12) | 14 (12) | 11 (15) | |

| Asian | 33 (12) | 4 (10) | 11 (9.4) | 10 (13) | |

| Unknown | 6 | 0 | 3 | 1 | |

| Ashkenazi N (%) | 0.23 | ||||

| Yes | 22 (9.2) | 4 (11) | 4 (3.6) | 6 (9) | |

| Unknown | 40 | 3 | 10 | 9 | |

| Family history N (%) | 0.86 | ||||

| Yes | 136 (50) | 19 (49) | 63 (53) | 40 (55) | |

| Unknown | 7 | 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| Germline mutation N (%) | 0.09 | ||||

| Yes | 20 (12) | 2 (8) | 12 (26) | 8 (19) | |

| Unknown | 114 | 15 | 73 | 33 | |

| Histology N (%) | 0.066 | ||||

| Invasive Ductal | 255 (91) | 38 (95) | 115 (96) | 66 (87) | |

| Invasive Lobular | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (5.3) | |

| Mixed Invasive | 11 (3.9) | 2 (5) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Other | 11 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 4 (3.3) | 5 (6.6) | |

| Tumor Size (cm) | 0.002 | ||||

| Median (Interquartile Range) | 1.8 (0–6.5) | 1.75 (0.6–4.2) | 2.5 (0–10) | 1.75 (0–11) | |

| Unknown | 4 | 0 | 4 | 2 | |

| LN positive N (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Positive | 123 (44) | 17 (42) | 93 (78) | 37 (49) | |

| Negative | 157 (56) | 23 (58) | 27 (22) | 39 (51) | |

| LVI N (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Positive | 97 (38) | 14 (39) | 67 (67) | 27 (44) | |

| Negative | 161 (62) | 22 (61) | 33 (33) | 35 (56) | |

| Unknown | 22 | 4 | 20 | 14 | |

| Estrogen Receptor N (%) | 0.07 | ||||

| Positive | 185 (67) | 22 (55) | 79 (69) | 37 (53) | |

| Negative | 93 (33) | 18 (45) | 36 (31) | 33 (47) | |

| Unknown | 2 | 0 | 5 | 6 | |

| Progesterone Receptor N (%) | 0.09 | ||||

| Positive | 167 (61) | 18 (45) | 59 (51) | 34 (49) | |

| Negative | 109 (39) | 22 (55) | 56 (49) | 35 (51) | |

| Unknown | 4 | 0 | 5 | 7 | |

| Her2Neu N (%) | 0.71 | ||||

| Positive | 190 (79) | 29 (78) | 62 (73) | 36 (75) | |

| Negative | 51 (21) | 8 (22) | 23 (27) | 12 (25) | |

| Unknown | 39 | 3 | 35 | 28 | |

| Axillary dissection N (%) | 0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 152 (54) | 28 (70) | 84 (70) | 51 (68) | |

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Sentinel LN bx N (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 191 (68) | 27 (68) | 26 (22) | 26 (35) | |

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Chemo adjuvant N (%) | 0.58 | ||||

| Yes | 250 (90) | 32 (84) | 110 (92) | 67 (89) | |

| Unknown | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Chemo neoadjuvant N (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 11 (3.9) | 2 (5.1) | 19 (16) | 4 (5.3) | |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Hormonal therapy N (%) | 0.02 | ||||

| Yes | 181 (66) | 21 (54) | 80 (67) | 37 (49) | |

| Unknown | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Treatment Before/After 2000 | <0.001 | ||||

| Before 2000 | 83 (30) | 13 (32) | 62 (52) | 37 (49) | |

| After 2000 | 197 (70) | 27 (68) | 58 (48) | 39 (51) | |

Outcomes of treatment in young breast cancer patients compared to older patients

Overall Survival and Disease-Free Survival

Ten-year overall survival was 73% among those ≤35 years of age. Figure 1a,b depicts local and distant recurrence outcomes while Figure 1c displays overall survival by age group (≤35 versus age 36–50 and 51–70), demonstrating worse outcomes in the youngest group. Supplement A illustrates OS and DFS within the ≤35 group, stratified by upfront treatment approach. When controlling for known co-variates of disease outcome, OS was statistically similar among the arms, with the exception of inferior outcomes for the mastectomy + RT group. This is likely due to disproportionately more prevalent adverse features compared to the BCS and mastectomy groups, respectively, including tumor size (median 2.5mm vs. 1.8 vs. 1.75, p<0.002), lymph node positivity (78% vs. 44% vs. 49%, p<0.001), and presence of LVI (67% vs. 38% vs. 44%, p<0.001) (Table 2). Additionally, this group received more axillary lymph node dissections (70% vs. 54% vs. 68%, p<0.01), less upfront sentinel lymph node biopsies (22% vs 68% vs. 35%, p<0.001), and more neoadjuvant chemotherapy (16% vs. 3.9% vs. 5.3%, p<0.001), presumably for indications that also justified PMRT. On multivariable analysis, factors associated with OS were tumor size (HR 1.14, 95% CI 1.02 – 1.27, p=0.024), the presence of LVI (HR 2.2, 95% CI 1.54 – 3.16, p<0.001), ER positivity (HR 0.64, 95% CI 0.45 – 0.91, p=0.015), receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy (HR 0.52, 95% CI 0.30 – 0.91, p=0.035), black race (HR 2.87, 95% CI 1.89 – 4.35, p<0.001), and mastectomy with RT (compared to mastectomy alone) (HR 3.19, 95% CI 1.66 – 6.15, p<0.001) (Supplement B). Disease-free survival rate at 10 years was 48% among those ≤35 years of age. Factors correlated with DFS on multivariate analysis were tumor size (HR 1.12, 95% CI 1.02 – 1.23, p=0.016), the presence of LVI (HR 1.67, 95% CI 1.26 – 2.22, p<0.001), PR positivity (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.56 – 0.97, p=0.028), black race (HR 1.59, 95% CI 1.09 – 2.30, p=0.035), mastectomy with RT (HR 2.37, 95% CI 1.44 – 3.89), and partial mastectomy with RT (HR 1.68, 95% CI 1.05 – 2.70) (Supplement B).

Figure 1:

Cumulative incidence of (a) locoregional recurrences and (b) distant metastasis in the three age groups. (c) Kaplan Meier survival curve for overall survival by age cohort.

Freedom from Local Failure and Distant Failure

The cumulative incidence of locoregional recurrences at 10 years was 20% (Figure 2a). Local failures occurred more frequently in the mastectomy + radiation group compared to the other three groups (p=0.04). Women ≤35 years of age were significantly more likely to experience local failure compared to the age 36–50 group (HR 2.2, 95% CI 1.8 – 2.6, p<0.001) and age 51–70 group (HR 3.1, 95% CI 2.45 – 3.9, p<0.001). On multivariate analysis, factors associated with local recurrence risk were black race (HR 1.95, 95% CI 1.15 – 3.30, p=0.013), Ashkenazi Jewish descent (HR 0.22, 95% CI 0.05 – 0.9, p=0.035), diagnosis before year 2000 (HR 2.06, 1.3 – 3.26, p=0.002), and mastectomy with RT (HR 4.24, 95% CI 1.74 – 10.35, p=0.002) (Supplement C).

Figure 2:

Cumulative incidence of (a) locoregional recurrence and (b) distant metastases in the ≤35 age group stratified by upfront treatment approach.

The cumulative incidence of distant recurrences at 10 years was 37% and was similar following breast conservation therapy or mastectomy without radiation, but was more frequent among those receiving post-mastectomy radiation (p=0.005) (Figure 2b). Women ≤35 years of age were at higher risk compared to the age 35–60 group (HR 2.2, 95% CI 1.8 – 2.6, p<0.001) and the age 51–70 group (HR 2.5, 95% CI 2.1 – 3.0, p<0.001). Factors correlated with distant recurrence risk on multivariate analysis were presence of LVI (HR 1.92, 95% CI 1.37 – 2.70, p<0.001), ER positivity (HR 0.56, 95% CI 0.33 – 0.88, p=0.013), receipt of hormonal therapy (HR 1.92, 1.14 – 3.22, p=0.014), mastectomy with RT (HR 3.24, 95% CI 1.72 – 6.08, p<0.001), and partial mastectomy with RT (HR 2.01, 95% CI 1.1 – 3.65, p=0.022) (Supplement C).

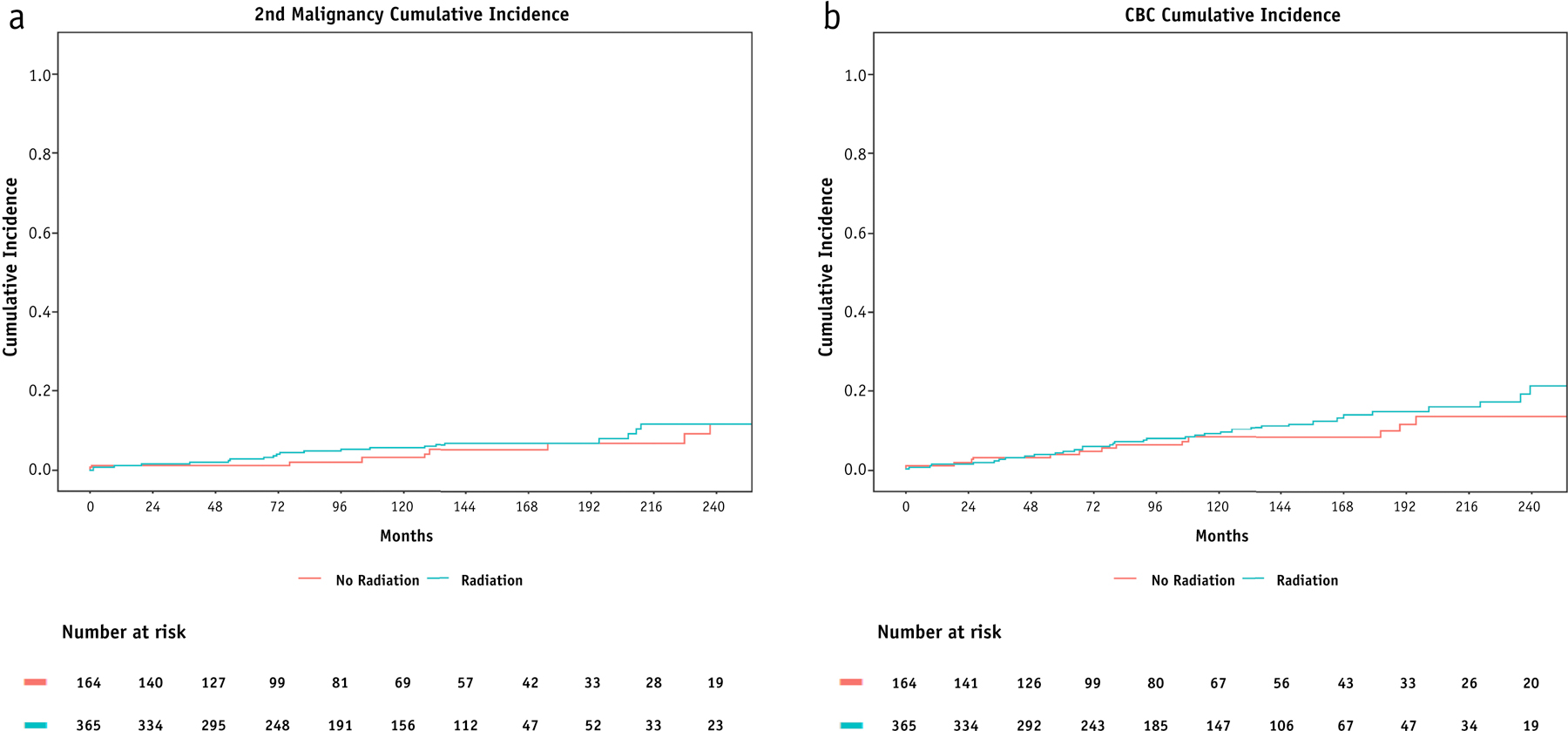

Rates of Second malignancy and Contralateral Breast Cancers

The rate of secondary malignancies at 5 years and 10 years was 2.2% and 4.4%, respectively (Figure 3a). On univariate analysis, alcohol use, family history, and detection of germline mutations were correlated with risk of SMs (Supplement D). Receipt of radiation was not associated with an elevated risk of secondary malignancies (HR 1.22, 95% CI 0.57 – 2.59, p=0.612). Compared to older cohorts, the ultra-young were not more likely to experience secondary malignancies. Of the 33 secondary malignancies, 11 are likely attributable to radiation, and another 10 can possibly be due to radiation. Complete description of second malignancy location and histology is provided in Supplement E.

Figure 3:

Cumulative incidences of secondary malignancies (a) and contralateral breast cancers (b) stratified by receipt of RT.

The rate of contralateral breast cancer for the ultra-young cohort was 4% at 5 years and 8.9% at 10 years (Figure 3b). On univariate analysis, family history and detection of germline mutations were predictive of CBCs (Supplement D). Use of any adjuvant radiation was not associated with risk of CBC, (HR 1.26, 95% CI 0.7 – 2.27, p=0.4).

Discussion

Very young breast cancer patients have been noted to have worse clinical outcomes compared to older cohorts. However, variability exists in the current literature on defining the age range that constitutes “young” and/or “very young” breast cancer patients, and establishing appropriate comparison groups of older age. In our study, we included patients age 35 years and younger and compared this cohort with an immediately older cohort (age 36–50) and a decades-older cohort (age 51–70). With a median follow-up of 10 years, our study sought to compare outcomes of ultra-young patients against the older cohorts and to determine factors the predict for mortality, recurrence, and secondary malignancies in the ultra-young.

Table 3 lists survival and relapse data from contemporary reports. Our reported outcomes in the ultra-young patients of 10-year OS, DFS, locoregional disease-free survival, and distant disease-free survival rates of 74%, 50%, 81%, and 64% respectively, are consistent with the literature. Beadle et al. analyzed patients age 35 years and younger with a median follow-up of 9.5 years and reported a 10-year overall survival rate of 64.6%, locoregional disease-free survival rate of 80.2%, and distant disease-free survival rates of 60.1%17. A recently published report by Szollar et al. described in a more modern cohort selected from women diagnosed in years 2000–2014 OS and DFS rates of 71% and 48%, respectively18. Of note, these lower rates likely are due to their inclusion of patients with stage IV disease. Conversely, Plichta et al. included patients with Stage 0 disease which comprised approximately 23% of their study population and noted starkly more favorable OS, DFS, and LR-free survival rates of 86.5%, 84.5%, and 94.1%19. Frandsen et al. provided an interesting analysis comparing outcomes of women age 40 years and younger diagnosed before year 2000 versus after 2000 with T1–2 tumors stratified by treatment approach16. Freedom from locoregional recurrence improved from 80.8% to 94.9% in BCT patients and 85.8% to 92.1% in mastectomy patients, which the authors attribute to improvements in radiation technique and systemic/hormonal therapy. These results are remarkably consistent given the long intervals that were needed to achieve sufficient sample sizes in these studies.

Table 3:

Summary of Selected Contemporary Series of Ultra-Young Patients with Nonmetastatic Invasive Breast Cancer

| Study | Year | Location | Sample Size (N) | Study Interval | Age (median, range) | Notable Selection Criteria | FU (median, range) | OS | DFS | LRFS | DDFS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Billena et al. | 2020 | US | 529 | 1990 – 2010 | 32 (20–35) | Excluded those who did not receive definitive surgery | 10.3 yrs (NA) | 10 year: 74% | 10 year: 50% | 10 year: 81% | 10 year: 64% |

| Plichta et al. | 2016 | US | 584 | 1996 – 2008 | 37 (21–40) | Included DCIS/Stage 0 disease | 10.3 yrs (0.4–19.7) | 10 year: 86.5% | 10 year: 84.5% | 10 year: 94.1% | |

| Frandsen et al. | 2015 | US | 853 | 1975 – 2013 | After 2000, BCT: 38.8 (NA); After 2000, M: 35.1 (NA) | Excluded T3–4 disease, multifocal or multicentric disease, refusal of RT after BCT | Before 2000, BCT: 15.8 (NA) ; Before 2000, M: 14.6 (NA) ; After 2000, BCT: 5.7 (NA); After 2000, M: 4.7 (NA) | 10 year: After 2000, BCT: 85.1%; After 2000, M: 79.7% | 10 year: After 2000, BCT: 85.1%; After 2000, M: 74.8% | Before 2000, BCT: 80.8%; Before 2000, M: 85.8%; After 2000, BCT: 94.9%; After 2000, M: 92.1% | |

| Beadle et al. | 2009 | US | 652 | 1973 – 2006 | 33 (16–35) | Excluded those who refused breast RT after breast conserving surgery, those who did not receive definitive surgery | 7.58 yrs (0.167–34.2) | 10 year: 64.6% | 10 year: 80.2% | 10 year: 60.1% | |

| Bharat et al. | 2009 | US | 344 | 1998 – 2006 | 36 (32–40) | Included DCIS/Stage 0 disease, Included Stage IV disease | NA | 6 year: 82% | |||

| Oh et al. | 2006 | US | 196 | 1987–2000 | 36 (21–40) | 5.33 yrs | 5 year, <35: 96.3%; 5 year, 35–40: 97.3% | 5 year, <35: 87.9%; 5 year, 35–40: 91.7% | |||

| Cao et al. | 2014 | Canada | 965 | 1989–2003 | NA (20–39) | Included early stage breast cancer (pT1/T2, pN0/N1 [<3 positive axillary lymph nodes], M0/X) only. Excluded patients treated with BCS without adjuvant radiation | 14.4 (8.4 – 23.3) | 15-year, BCT: 74.2%; 15-year, M: 73.0% | 15-year, BCT: 82.2%; 15-year, M: 81.6% | 15-year, BCT: 74.4%; 15-year, M: 71.6% | |

| Coulombe et al. | 2006 | Canada | 540 | 1989 – 1998 | NA (20–39) | Included early-stage breast cancer (pT1/T2, pN0/N1/NX, <3 positive axillary lymph nodes, M0) only, excluded those receiving BCS without RT and those receiving nodal irradiation | 9 (NA) | 10-year BCSS: 78.1% | 10-year: 82.7% | 10-year: 72.9% | |

| Vasquez et al. | 2016 | Brazil | 376 | 1985–2002 | NA (≤40) | NA (0 – 22.6 yrs) | 5-year: 62% | ||||

| Szollar et al. | 2019 | Hungary | 297 | 2000–2014 | 33 (20–35) | Included DCIS and Stage IV disease | 5.75 yrs (0.08 – 16.5) | 10-year: 71% | 10-year: 48% | ||

| Bantema-Joppe et al. | 2011 | Netherlands | 1453 | 1989–2005 | 36.5 (IQR 33.8–38.4) | Included patients with pT1a-c, pN0–1, M0 only. Excluded those treated with neoadjuvant therapy and those who did not receive RT after BCS. | 9.6 yrs (IQR 5.9–14.3) | 10-year, BCT: 83%; 10-year, M: 78% | |||

| van der Sanger et al. | 2010 | Netherlands | 1451 | 1988–2005 | M: 37.3, BCT: 37.4 | Included patients with Stage I or II breast cancer (pT1–2, N0–2, M0) only | 7.4 years (M), 9.5 years (BCT) | 10-year, BCT: 74.9%; 10-year, M: 71.2% | 10-year, BCT: 82%; 10-year, M: 94% | 10-year, BCT: 71%; 10-year, M: 67% | |

| Wei et al. | 2014 | China | 283 | 1995–2011 | NA (≤35) | Excluded patients with renal or cardiovascular systemic disease | NA | 10-year: 52% | |||

| Han et al. | 2004 | South Korea | 256 | 1990–1999 | NA (<35) | Excluded those with positive surgical margins | 6.17 yrs | ||||

| Elkum et al. | 2007 | Saudi Arabia | 288 | 1986–2002 | NA (≤40) | Excluded those with positive surgical margins | NA | 10-year: 60% |

In our study, ultra-young patients were 2.2 to 3.1 times more likely to experience local and distant recurrence compared to older cohorts. Oh et al. compared ≤35 versus 35–40 who received BCT and found local relapse risk was 2.3 times higher for the ≤35 group with local control rates of 87.9% and 91.7% at 5 years, respectively20. Similarly, in women age 35 years and younger in relation to 36–45, Szollar et al. described significantly worse 75-month OS (78% vs. 89%) and DFS (62% vs. 78%)18. Using a cut off of age 40, Coulombe et al. additionally reported on relapse data finding that women age ≤40 as compared to patients age 40–49 years had statistically significantly lower 10-year relapse-free survival locally (85.3% vs 92.3%), locoregionally (82.0% vs 88.7%), and distantly (72.9% vs 84.1%).21 Bharat et al. compared outcomes of 344 women ≤40 years to all women > 40 years and found that women ≤40 years old were 1.52 times more likely to die22. Despite controlling for staging and tumor histologic characteristics, Bharat et al. and Oh et al. demonstrated that young age remained an independent negative prognosticator20,22.

Given worse clinical outcomes in very young patients, there is a concern that breast conservation therapy might lead to inferior survival or recurrence rates compared to mastectomy. Some investigators have noted higher local recurrence rates with BCT. Voogd et al. in a pooled analysis of EORTC 10801 and DBCG 82TM, which recruited patients during 1980–1989 reported that in patients who received BCT, those age ≤35 years had 9.34 times increased risk of local recurrence compared to those older than 60 years3. There was no increased risk amongst those ≤35 years who received mastectomy. Local recurrence rates for BCT and mastectomy among patients ≤35 were 35% and 7%, respectively. Similarly, van der Sanger et al. reported in a subset ≤ age 40 of a large Netherland registry cohort described that while the rates of local recurrence in mastectomy patients plateaued at 6% after 10 years, the risk of LR in BCT patients starkly climbed from 8.3% at 5 years, 18.3% at 10 years, and 27.9% at 15 years, although this did not translate to differences in overall survival rates between the surgical arms23. Of note, Voogd et al. and van der Sanger studies only included Stage I and II cases who would presumably be ideal candidates for BCT.

On the other hand, other analyses contend that BCT is equivalent to mastectomy on the basis of overall survival. Mahmood et al. conducted an analysis using SEER of 14,764 women T1–2N0–1M0 patients ≤40 years old diagnosed between 1990 and 2007 and demonstrated BCT did not confer excess risk of death over mastectomy in multivariable analysis (HR 0.94, 95% CI 0.83 – 17.9)24. Additionally, in a matched pair analysis, Mahmood et al. reported that OS for BCT and mastectomy was 92.5% vs. 91.9% at 5 years, 85.5% vs. 85.5% at 10 years, and 79.1% vs. 81.9% at 15 years. Corroborating Mahmoud et al.’s findings, Ye et al. performed a separate SEER-based analyses of 7665 women age <40 years with Stage I-II disease and found no differences in OS or BCSS between the BCT and mastectomy groups25. A meta-analysis by Vila et al. of 22,598 patients ≤40 years old with T1–2N0-N+M0 breast cancer reported 10% decreased risk of death with BCT over mastectomy (HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.81–1.00)26. Other cohort studies also corroborate the appropriateness of BCT16,17,19,21,27–29. In our report, we found no difference in OS by BCT vs mastectomy, but did find a difference in DFS and distant recurrence rates with BCT. These results are to be interpreted with caution, as we cannot fully account for hidden confounders. Nonetheless, we can be quite sure that these very young patients require aggressive management, and perhaps more careful attention to staging and pathology features prior to selection of BCT in these patients.

Adjuvant radiation is an integral component of BCT and often used after mastectomy; however RT carries the risk of second malignancies and contralateral breast cancers, a primary concern for young patients. In the present study, we found that there was no increase in secondary malignancies or CBCs at 10 years after receipt of radiation. Burt et al. analyzed a SEER dataset of 374.993 patients and found 1.3-times increased risk of secondary malignancies after RT, with 3.4% of SM and 0.8% of CBC attributable to RT30. Notably, the risk of SM involving the esophagus, soft tissue, lung and respiratory tract rose as a function of latency time, generally starting at 10 years post-treatment. Using the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group database of 46,176 patients, Grantzau et al. reported an increase of in-field secondary malignancies with radiation (HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.11–1.61)31. In concordance with the findings of Burt et al., SM risk increased as a function of latency time, corresponding to a 55% and 79% higher relative risk at time periods 10–14 and >= 15 years post-treatment, respectively. In contrast, Hamilton et al. using the British Columbia Outcomes Unit database of 12,836 found no differences in in-field SM (SIR 1.06) and lung cancer (SIR 1.08)32. While SM of all sites were increased (SIR 1.30), this was primarily driven by exceeding SMs of the contralateral breast (SIR 1.79), uterus (SIR 1.70), and ovaries (SIR 1.88) rather than in-field SMs, which the authors hypothesized was related to endocrine therapy. Radiation-associated SM fortunately appear to be uncommon, but since risk rises as a function of latency time, young women should be counseled and surveilled appropriately.

There are several limitations to our study. Given the retrospective nature, our data is susceptible to human error and measurement bias during medical record keeping as well as during chart review process required for this study. Some data, particularly patient behavior data such as family history, smoking history, alcohol use, and use of contraceptives or fertility treatments, is affected by recall bias wherein during patient intake, the patient may incorrectly recollect information. Confounding factors may influence our results, despite controlling for several patient, treatment, and tumor characteristics using multivariate analysis. Unknown factors may underpin the decision to undergo more aggressive therapy, including mastectomy over BCT and PMRT over no RT. For example, post-mastectomy radiation therapy would not be expected to increase the risk of distant recurrences, so this finding may be the result of confounding by indication, but should be partly accounted for by our multivariable model including clinicopathologic features. Reassuringly, our multivariable analysis mostly revealed variables of interest that are concordant with prior reports, suggesting the soundness of our approach. Still, some factors including radiation dose, use of boost, and inclusion of regional nodal volumes in the radiation field were not recorded. Regarding SM and CBC, additional follow-up may be needed, given that risk continues to rise beyond 10 years. Our small sample size and event rates of SM and CBC may render our power insufficient for capturing a true difference. We were bound by the competing interests of studying a relevant cohort treated with modern treatments, and the need for sufficient follow up for the outcomes of interest.

Summary

Survival and recurrence outcomes in breast cancer patients ≤35 years of age are worse compared to both the age 36–50 and 51–70 years cohort. BCT as initial treatment does not compromise survival compared to mastectomy in these patients. Based on our data, the concern for second malignancies should not impinge on the known indications for post-operative radiotherapy. Additional follow-up is needed to fully characterize the risk of radiation-associated secondary malignancies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

No sources of funding were received for the creation of this manuscript

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Research data are stored in an institutional repository and will be shared upon request to the corresponding author.

Disclosures: Dr Morrow has received honoraria from Genomic Health, unrelated to the data in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Johnson RH, Anders CK, Litton JK, Ruddy KJ, Bleyer A. Breast cancer in adolescents and young adults. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(12):e27397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Bock GH, van der Hage JA, Putter H, Bonnema J, Bartelink H, van de Velde CJ. Isolated locoregional recurrence of breast cancer is more common in young patients and following breast conserving therapy: Long-term results of European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer studies. European Journal of Cancer. 2006;42(3):351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voogd AC, Nielsen M, Peterse JL, et al. Differences in risk factors for local and distant recurrence after breast-conserving therapy or mastectomy for stage I and II breast cancer: pooled results of two large European randomized trials. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19(6):1688–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wapnir IL, Anderson SJ, Mamounas EP, et al. Prognosis After Ipsilateral Breast Tumor Recurrence and Locoregional Recurrences in Five National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Node-Positive Adjuvant Breast Cancer Trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(13):2028–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maggard MA, O’Connell JB, Lane KE, Liu JH, Etzioni DA, Ko CY. Do young breast cancer patients have worse outcomes? Journal of Surgical Research. 2003;113(1):109–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bharat A, Aft RL, Gao F, Margenthaler JA. Patient and tumor characteristics associated with increased mortality in young women (≤40 years) with breast cancer. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2009;100(3):248–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anders CK, Hsu DS, Broadwater G, et al. Young age at diagnosis correlates with worse prognosis and defines a subset of breast cancers with shared patterns of gene expression. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(20):3324–3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han W, Kang SY. Relationship between age at diagnosis and outcome of premenopausal breast cancer: age less than 35 years is a reasonable cut-off for defining young age-onset breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2010;119(1):193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Partridge AH, Hughes ME, Warner ET, et al. Subtype-Dependent Relationship Between Young Age at Diagnosis and Breast Cancer Survival. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(27):3308–3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Hage JA, Mieog JSD, van de Velde CJH, Putter H, Bartelink H, van de Vijver MJ. Impact of established prognostic factors and molecular subtype in very young breast cancer patients: pooled analysis of four EORTC randomized controlled trials. Breast cancer research : BCR. 2011;13(3):R68–R68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredholm H, Eaker S, Frisell J, Holmberg L, Fredriksson I, Lindman H. Breast cancer in young women: poor survival despite intensive treatment. PloS one. 2009;4(11):e7695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fredholm H, Magnusson K, Lindstrom LS, et al. Long-term outcome in young women with breast cancer: a population-based study. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2016;160(1):131–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nixon AJ, Neuberg D, Hayes DF, et al. Relationship of patient age to pathologic features of the tumor and prognosis for patients with stage I or II breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1994;12(5):888–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kataoka A, Iwamoto T, Tokunaga E, et al. Young adult breast cancer patients have a poor prognosis independent of prognostic clinicopathological factors: a study from the Japanese Breast Cancer Registry. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2016;160(1):163–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gnerlich JL, Deshpande AD, Jeffe DB, Sweet A, White N, Margenthaler JA. Elevated breast cancer mortality in women younger than age 40 years compared with older women is attributed to poorer survival in early-stage disease. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2009;208(3):341–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frandsen J, Ly D, Cannon G, et al. In the Modern Treatment Era, Is Breast Conservation Equivalent to Mastectomy in Women Younger Than 40 Years of Age? A Multi-Institution Study. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2015;93(5):1096–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beadle BM, Woodward WA, Tucker SL, et al. Ten-year recurrence rates in young women with breast cancer by locoregional treatment approach. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2009;73(3):734–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szollár A, Újhelyi M, Polgár C, et al. A long-term retrospective comparative study of the oncological outcomes of 598 very young (≤35 years) and young (36–45 years) breast cancer patients. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2019;45(11):2009–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plichta JK, Rai U, Tang R, et al. Factors Associated with Recurrence Rates and Long-Term Survival in Women Diagnosed with Breast Cancer Ages 40 and Younger. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(10):3212–3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oh JL, Bonnen M, Outlaw ED, et al. The impact of young age on locoregional recurrence after doxorubicin-based breast conservation therapy in patients 40 years old or younger: How young is “young”? International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2006;65(5):1345–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coulombe G, Tyldesley S, Speers C, et al. Is mastectomy superior to breast-conserving treatment for young women? International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2007;67(5):1282–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bharat A, Aft RL, Gao F, Margenthaler JA. Patient and tumor characteristics associated with increased mortality in young women (< or =40 years) with breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100(3):248–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Sangen MJ, van de Wiel FM, Poortmans PM, et al. Are breast conservation and mastectomy equally effective in the treatment of young women with early breast cancer? Long-term results of a population-based cohort of 1,451 patients aged </= 40 years. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2011;127(1):207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahmood U, Morris C, Neuner G, et al. Similar Survival With Breast Conservation Therapy or Mastectomy in the Management of Young Women With Early-Stage Breast Cancer. International Journal of Radiation Oncology • Biology • Physics. 2012;83(5):1387–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye JC, Yan W, Christos PJ, Nori D, Ravi A. Equivalent Survival With Mastectomy or Breast-conserving Surgery Plus Radiation in Young Women Aged < 40 Years With Early-Stage Breast Cancer: A National Registry-based Stage-by-Stage Comparison. Clinical breast cancer. 2015;15(5):390–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vila J, Gandini S, Gentilini O. Overall survival according to type of surgery in young (≤40 years) early breast cancer patients: A systematic meta-analysis comparing breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy. The Breast. 2015;24(3):175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao JQ, Truong PT, Olivotto IA, et al. Should women younger than 40 years of age with invasive breast cancer have a mastectomy? 15-year outcomes in a population-based cohort. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2014;90(3):509–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bantema-Joppe EJ, de Munck L, Visser O, et al. Early-stage young breast cancer patients: impact of local treatment on survival. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2011;81(4):e553–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroman N, Holtveg H, Wohlfahrt J, et al. Effect of breast-conserving therapy versus radical mastectomy on prognosis for young women with breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100(4):688–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burt LM, Ying J, Poppe MM, Suneja G, Gaffney DK. Risk of secondary malignancies after radiation therapy for breast cancer: Comprehensive results. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2017;35:122–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grantzau T, Mellemkjaer L, Overgaard J. Second primary cancers after adjuvant radiotherapy in early breast cancer patients: a national population based study under the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG). Radiother Oncol. 2013;106(1):42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamilton SN, Tyldesley S, Li D, Olson R, McBride M. Second malignancies after adjuvant radiation therapy for early stage breast cancer: is there increased risk with addition of regional radiation to local radiation? International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2015;91(5):977–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.